- About PDK International

- About Kappan

- Issue Archive

- Permissions

- About The Grade

- Writers Guidelines

- Upcoming Themes

- Artist Guidelines

- Subscribe to Kappan

- Get the Kappan weekly email

Select Page

To engage students, give them meaningful choices in the classroom

By Frieda Parker, Jodie Novak, Tonya Bartell | Sep 25, 2017 | Feature Article

It’s important to give students influence over how and what they learn in the classroom. But not all choices are equal. Teachers should structure learning scenarios that equip students with opportunities to strengthen their autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Giving student real choices in the classroom — having to do with the material they study, the assignments they complete, the peers with whom they work, and so on — can boost their engagement and motivation, allow them to capitalize on their strengths, and enable them to meet their individual learning needs. But, like most teaching strategies, the structuring of choices for students can go very well, and it can go very badly — the nuances make all the difference.

Teachers need to understand how individuals and groups of students are likely to respond to any given opportunity to make consequential choices about the goals, activities, and experiences they wish to pursue in the classroom. To illustrate, we describe three cases in which high school mathematics teachers presented their students with choices. (Although these three vignettes feature secondary math classrooms, we argue that their lessons can generalize to other settings and subject areas.) We begin with the case of Ms. R, who found that when she gave her students a specific choice to make, she saw noticeably improved engagement in learning. Next, we describe the case of Ms. C, who provided a similar choice to her students but was disappointed with their response. We then discuss the ways in which students’ feelings determined how they responded to the given choices, and we describe a third case, which illustrates how teachers can structure choices that are likely to support student engagement.

The Case of Ms. R – Choice improving student engagement

Once a week, Ms. R gave students in her Algebra I class a choice of activities to work on. On these “work days,” as students called them, Ms. R offered a set of three to four activities. Each student could select the activity that featured the skill that they thought they needed to work on the most. Before implementing these work days, Ms. R was concerned that students might not use their time wisely, so she made sure to give them plenty of work to do, including supplemental practice problems.

Initially, when she introduced the work days, students found it difficult to choose an activity. Ms. R believed this was because students had little experience making choices in school, and they were in the habit of letting their teachers make all the decisions. Thus, she made it a priority to teach them, explicitly, how to choose an appropriate activity.

By the third week, students were comfortable selecting activities and were productive in their work. Ms. R was pleasantly surprised to observe that her students spent more time helping each other and even policing each other’s behavior, calling out peers whose behavior was distracting or who weren’t being productive. Overall, she found that students knew what they needed to work on and when they needed help, and they used their time accordingly. This meant students spent more time on-task and asked for her help less often. As a result, Ms. R. was able to spend more time checking on students’ progress and helping those who genuinely needed her assistance. Ms. R was happy to learn she could trust students to make positive choices.

The Case of Ms. C – Choice not improving student engagement

In her Algebra I class, Ms. C offered a choice activity that appeared to similar to the one that Ms. R offered, only the result was quite different. During a unit on inequalities, she presented students with four problem sets (each consisting of eight problems), each one pegged to a certain level of difficulty. They should each choose one or two problems from two of the four levels, she explained, advising students to choose problems based on their self-assessment of their readiness for each level.

By the end of class, Ms. C was disappointed with her students. Most were treating the problems like busywork, rushing through them without giving them much thought. Further, most students picked problems from the easiest two levels, even though Ms. C knew that some of them were ready to work at levels three and four.

What makes choices engaging? Autonomy, competence, and relatedness Judging by the research literature on choice in the classroom, itǯs not unusual to see the very different outcomes experienced by Ms. R and Ms. C — some studies show that choice positively influences student motivation and learning (e.g., Assor, Kaplan, & Roth, 2002), while others indicate that choice has either no or even a negative effect (e.g.,D’Ailly, 2004). To explain these conflicting outcomes, psychologists Idit Katz and Avi Assor (2006) have argued that what matters most isn’t the kind of choice given to students but, rather, how students perceive the choice provided to them: When students associate feelings of autonomy, competence, and relatedness with choice, then choice is most likely to result in beneficial outcomes, such as student engagement.

Students feel autonomous when they understand the value or relevance of a task, particularly if they believe that the task aligns with their values, interests, and goals. It comes not just from participating in the process of choosing but, rather, from having a sense that the choice is personally meaningful. Students must see real differences in the importance or relevance of the choices at hand, and they must find at least one option to be worth choosing. In short, while Ms. R and Ms. C each gave students a choice of tasks, there was something about the set of choices that Ms. R created that made her students feel that those choices were meaningfully different. Evidently, Ms. C’s students did not feel this way.

Students feel competent when they believe they know what to do to be successful and feel capable of mastering challenges. To engender competence, students must perceive choosing the task and doing the selected work as appropriately difficult. When people are confronted with too many choices or believe the selection process is too complex, they opt for an easier choice method such as choosing a default, choosing randomly, choosing not to choose, or letting someone else choose for them. Teachers, then, must make the selection process appropriate for students in terms of the number of choices and the ways in which students are expected to choose.

Students feel competent when they believe they know what to do to be successful and feel capable of mastering challenges.

Ms. R provided only three to four choices, she was explicit with her students that they choose activities they felt would best address their learning needs, and she made a point of providing explicit instruction in how to make good choices. In contrast, Ms. C told students to choose two out of four problem levels and then one to two problems out of eight problems in each level. This required two stages of choice, and it wasn’t clear that students knew how to make a good choice at either of those stages. It seem likely that they were overwhelmed by the range of choices at hand, so they opted for the easiest choices they could make.

The other part of engendering competence is that students must be able to choose tasks that are appropriately challenging. That is, possible tasks should not all be too easy or too hard. In Ms. R’s case, students appeared able to find tasks that engaged them and that they could successfully complete on their own or with help from peers or Ms. R. The problems in Ms. C’s packet may have been similarly appropriate but perhaps due to the high cognitive demand of choosing from among 32 problems, most students did not find problems best suited for them.

Relatedness

A sense of relatedness stems from feeling close to people or a sense of belonging in a group. Choice can influence student’s feelings of relatedness differently depending on their beliefs. Students with more collectivist beliefs value relationships and making contributions to group efforts and can see individual choice as a threat to group harmony. Students with more hierarchical beliefs value the role of authority figures and can see choice as a threat to acceptance from people in authority, such as teachers. People with individualistic beliefs value personal goals over group goals and tend to value choice as a means of demonstrating independence and expressing individuality. However, choice can undermine a sense of relatedness for students with individualistic beliefs if they perceive their choices could lead to rejection, humiliation, or teasing. Ms. R gave students choices that did not seem to interfere with, and possibly supported, students’ sense of relatedness as they worked more closely on “work days” than on other days. But students’ sense of relatedness in Ms. C’s classroom is not clear because she provided the choice for only one day, and students didn’t appear to perceive the choice as supporting autonomy or competence.

Learning from choice outcomes

So, how might Ms. C learn from her disappointing experience in providing choices to her students? First, she could have conjectured why students might not have associated feelings of autonomy, competence, or relatedness with the choice she provided them. Reasoning as described above, she might hypothesize that the process of choice was too complex, and students might not have had good strategies for choosing appropriate problems. To check her thinking and get more ideas, Ms. C could then ask students why they responded to the worksheet as they did. For instance, she might ask:

- Why did you pick only levels one and two?

- Why did you do only one problem at each level instead of two?

- Did you find the problems helpful to do? Why or why not?

- What might have made this activity better for you to practice solving problems involving inequalities?

Students are often quite insightful about their learning needs. In talking with students, teachers might find that the fundamental structure of the choice they provided the students was not conducive for students’ feelings of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. However, like Ms. R, teachers might find that changing the choice structure is not necessary; instead what is needed is helping students understand the rationale for the choice and how to productively make choices. And, of course, improving choice may involve some combination of changing the choice structure along with educating students about how to use choice to learn.

Students who associate a choice with feeling autonomous, competence, and in relationship with others are more likely to be engaged with the learning.

Next, we provide one more case to show a different choice structure, how this choice related to students’ feelings of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, and the type of student engagement choice can foster. Student engagement can sometimes be garnered by providing relatively small and simple choices to students. The case of Ms. H illustrates this.

The Case of Ms. H — Small choice, big engagement

Every day, Ms. H prepared two warm-up problems, each with the same mathematical content but situated in different contexts — for example, one problem might have to do with hiking and the other with flying. The two contexts were always on the board, and during the first minute of class, students were allowed to vote for the one that interested them. In order to make sure that they could vote, some students began to arrive to class early, and overall, the number of students who were late went down. The motivation to select a context carried over into actually doing the warm-up problem. According to Ms. H, all students began to actively engage in doing the warm-up, which had not occurred before she began offering students the choice of contexts.

After the first week of voting for the warm-up problem context, students asked Ms. H if they could suggest contexts. Ms. H agreed and students put suggestions in a hat, from which she drew contexts for the next day’s warm-up. After two weeks of doing the warm-up voting, Ms. H tried to stop, but students loudly objected, so Ms. H continued providing the choice. Tardies continued to remain low, and student engagement in the warm-up problems remained high.

The success of Ms. H’s warm-up context choice can be explained by its influence on students’ feelings of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Students’ feelings of autonomy were likely fostered because most students found at least one context meaningful to them, which was probably strengthened when students began suggesting contexts. Students likely felt competent making this choice because choosing was relatively simple, and the actual warm-up problem appeared appropriately challenging for most students, as indicated by their level of engagement. The fact that students worked productively on whichever warm-up problem was selected suggests the choice did not interfere with students’ sense of relatedness. Thus, Ms. H’s experience demonstrates that relatively simple choices can foster the key feelings of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, and consequently even simple choices can improve student engagement.

Teachers have described to us any number of ways in which they provide choice to students, including giving them opportunities to choose work partners, seating arrangements, homework problems, assessment problems, and ways of being assessed.

Like Ms. R, many teachers are initially concerned that students will not respond well to having choices. Ms. R addressed her concern by making sure to have plenty of work available for students to do; other teachers make it a point to be explicit with students about why they are providing choices, and they request student feedback on whether they value the choice. Whatever strategy they choose, though, teachers can increase the likelihood their students will value choice by analyzing how students associate feelings of autonomy, competence, and relatedness with the choice provided them. While this might take some trial and error, finding the right choice structures for students can be a powerful tool for fostering student engagement.

Assor, A., Kaplan, H., & Roth, G. (2002). Choice is good but relevance is excellent: Autonomy affecting teacher behaviors that predict students’ engagement in learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72, 261–278.

D’Ailly, H. (2004). The role of choice in children’s learning: A distinctive cultural and gender difference in efficacy, interest, and effort. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 36, 17–29.

Katz, I. & Assor, A. (2007). When choice motivates and when it does not. Educational Psychology Review, 19 (4), 429-444.

Citation: Parker, F., Novak, J, & Bartell, T. (2017). To engage students, give them meaningful choices in the classroom. Phi Delta Kappan 99 (2), 37-41.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Frieda Parker

FRIEDA PARKER is an assistant professor of mathematics at University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, Colo.

Jodie Novak

JODIE NOVAK is an assistant professor of mathematics at University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, Colo.

Tonya Bartell

TONYA BARTELL is an associate professor of mathematics education, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Mich.

Related Posts

Going all in on college counseling: Successes and trade-offs

September 23, 2019

Academic learning + social-emotional learning = national priority

October 1, 2013

A caring climate that promotes belonging and engagement

January 24, 2022

Students speak up

March 25, 2019

Recent Posts

- Online Courses

Letting Students Lead the Learning

According to a Gallup Student Poll (2015) of public school children, 47% report being “disengaged” at school. Unfortunately, this statistic doesn’t shock me. Too many classrooms are not set up with the intention of engaging students.

Student engagement is “ the degree of attention, curiosity, interest, optimism, and passion that students show when they are learning or being taught .” As a teacher, it’s my job to engage student curiosity, interest and passion in relation to the curriculum. I cannot do that effectively if I place myself at the center of learning and ask students to focus on me. A class designed to engage learners must place the students at the center of the learning happening.

I realize this goes far beyond simply shifting away from a lecture model. It means really rethinking our entire approach to teaching. I experienced a moment of clarity as I prepared to introduce a large scale project last month…

My students were about to start an RSA animation project focused on a genocide of their choice. I was preparing a Google Document with an explanation of what RSA animation is, detailed directions for creating an RSA film, and suggested roles for students. As I looked at my detailed explanation of the project, I asked myself, “Why do I need to tell students how to do this? Why not let students figure it out? Wouldn’t figuring it out be more interesting and engaging?”

The truth is I didn’t need to teach my 9th and 10th-grade students what an RSA animated film is or how to create one. When students leave high school, they will be expected to successfully navigate myriad challenges and novel situations. If I tell them how to complete a project, then 1) they haven’t had to struggle, problem solve, or learn how to learn and 2) I’ve only shown them my way (not necessarily the best way) of completing this project.

Instead of giving them access to that Google Document full of information and instructions, I asked students to investigate RSA animation to find out what it is and how they are created. Then groups worked together to write a project proposal explaining how they were going to execute this project. It required them to think through the purpose, strategy, and process before beginning their work. It asked them to do the work that most teachers do for them.

The finished products are a testament to how successful students can be when they are given a chance to lead the learning happening in the classroom.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LC-rYkS3i0M

I’ve come to realize that if I tell my students how to do their work, I remove the incentive for them to really engage, think critically, and problem solve. It’s so important that students learn how to learn and navigate unfamiliar tasks and challenges.

20 Responses

Great stuff! As a history teacher and a United States Holocaust Memorial Mueum Teaching Fellow, I am always excited to see teachers in other subject areas having students learn more about genocides. Additionally, your seamless integration of student creation of RSA to present their learning is fantastic! Engaging minds in creative learning activities is how to engage students in the 21st century. I only hope to continue to learn from your example moving forward.

Thanks again for sharing.

Thank you, Scott! My students read Elie Wiesel’s memoir Night about his experience during the Holocaust, but I wanted them to realize that genocides have happened since the Holocaust. Most of my students didn’t realize that there have been so many genocides. They really enjoyed the project!

Thanks for the comment!

When I taught “A Raisin in the Sun” I asked students to decide whether or not one of the main characters would have a better, worse or about the same chance of achieving his/her dream today than the character did during the time of the play. I like this idea to update it! Crazy, I devised the same assignment for “Night” last year; I asked if we’ve learned anything from the Holocaust, based on the genocide they chose to study. I had them do a power point or Prezi last year; this year I’ll definitely try RSA!! Thanks so much.

I love that question, Jane, about whether or not it would be easier or more challenging to achieve dreams (or the American Dream) today. That question could be used with so many different texts and help students think about how our country has changed.

I totally agree. Genocides are things everybody should learn so that we dont make the same mistake again.

Thanks for the reply!

Yes, unfortunately, there have been many genocides and it is often eye-opening to students to realize that the Holocaust was not the first, nor the last. A great companion piece to Weisel’s work is “Leap Into Darkness” by Leo Bretholz. He was a teenager on the run from the Nazis throughout the course of the war. He was arrested, and escaped, the Nazis several times, including his last escape – a daring jump off a train of victims destined for Auschwitz. It is a remarkable story that offers a very different experience, but one no less traumatic than Weisel’s. I’ve used it many times and the students really enjoy reading it.

Keep up the great work!

Thank you for the recommendation, Scott. I’ll check out “Leap Into Darkness”. It sounds intense!

What started out as an experiment to garner more participation has turned into one of my favorite classroom activities. I highly recommend letting students take the lead. I believe you will find that your silence will break down theirs.

I think this is an important point you are making about giving students control, and I am sure your students learned a lot from this exercise. However, I do worry that students might learn more deeply from writing a traditional paper than from making an RSA-style video. I watched the Rwandan Genocide video, and it’s good — but it seems a bit superficial. It doesn’t get at some crucial questions: how were 800,000 people able to be slaughtered in 100 days? That’s 8,000 per day. How could that happen? How could the world watch that happen? The video makes it seem like there were just the Hutu and Tutsi, isolated from the rest of the world. I fear that the time spent learning to make RSA-style video may have taken away from some of the depth and complexity of the Rwandan Genocide. Did the students watch Hotel Rwanda, for example? That film generates some powerful discussions.

Also, I’m curious what class worked on this (what age student and what class) and how long students had to work on the project. I teach US History to high school sophomores and juniors, and there’s a good bit of material the state says we have to cover, which makes it challenging (though not impossible) to do extended projects of the sort you describe here. I’m working now on having students write a short paper explaining the Iraq War. I’m not sure we’ll also have time to make videos, but now I’m thinking about it, thanks to your blog and video. Thanks for sharing and for making me think more deeply about my own teaching.

As a 9th and 10th grade English teacher, my students complete a variety of pieces of writing to analyze different texts, topics, and issues. I agree that writing is one way to demonstrate understanding, but it isn’t the only way or even the best way for many students. My goal with RSA, as well as a wide range of other types of alternative types of assignments (i.e. infographics, thematic memes, Instagram sensory walks), is to provide students with different avenues to demonstrate their understanding. Some students excel at writing while others are more creative and artistic.

What I like about RSA is that students are developing a whole host of skills by working collaboratively to create the films. They conduct research, collaborate on a shared script to take their research and turn it into a story, design a storyboard, and edit/publish their films. There are so many important skills cultivated with this one assignment that go beyond simply understanding the causes, realities and impacts of the actual genocide they are researching.

We did not watch Hotel Rwanda . Each of the groups in my class selected a separate genocide to focus on for this assignment. The goal was to get them to understand that there have been genocides beyond the Holocaust, which we were reading about. Often students hear that they must learn about the Holocaust to ensure that nothing like that happens again. I want them to understand that genocide has happened and is happening around the world.

My husband is a World History teacher, so I know the history standards are intense. That said, I worry that marching through the events in history without opportunities to dive deeper will result in kids who don’t remember much. If there is time to take some deeper dives into aspects of history that are particularly important, I think projects like RSA film making can be incredibly valuable and worthwhile. That’s not to say every film will be incredible, but it’s important to consider what else the kids are learning as they work together to execute a multifaceted project like this.

I appreciate your comment as I’m sure other teachers are curious about similar issues!

[…] Letting Students Lead the Learning | An effective way to have students learn about a topic. “Instead of giving them access to that Google Document full of information and instructions, I asked students to investigate RSA animation to find out what it is and how they are created. Then groups worked together to write a project proposal explaining how they were going to execute this project. It required them to think through the purpose, strategy, and process before beginning their work. It asked them to do the work that most teachers do for them.” […]

[…] 5. Finally, I am no longer the only “expert” in the room. In fact, I try not to talk at my students. I’d much rather have them investigate a topic, research, talk about what they found, and teach each other. I cannot go home with my students at the end of the day, so it’s essential that they learn how to learn. (For more, see my blog titled “Letting Students Lead the Learning.”) […]

[…] plan lessons and units, teach their peers about complex topics in station rotation lessons, design their own projects rooted in their passions, provide each other with tech support as needed, assess their own work on a weekly basis and […]

I think this is a great idea!! I do a lot of technology with my students and I was wondering if you ever had students create their own essential question to coincide with the proposal. How many days did did it take from start to finished product?

I have had students craft essential questions to guide their work on RSA (and other research based work). It’s a great way to have them narrow their focus and stay on point. The RSA project took about a week and a half from start to finish and we dedicated about half of our 90 minute class to it each day. That includes research, drafting and editings scripts, drawing and recording.

This is a great way for students to collaborate and create together using a different medium for expression. I am a library media specialist working with students who are in grade 5. In their classroom the students are working on social issues in book clubs and I was going to have the create PSA’s about the issue depicted in their book club book. I am interested in RSS but I am concerned it may be a bit much for this age group. Have you had any experience with students as young as 5th grade using this tool?

I saw a 3rd grade class create RSAs showing scientific processes. It definitely took them a little longer, but the finished products were excellent!

[…] Tucker also had a great post on this idea of letting students take charge of their learning. She discusses the ups and the […]

I like this because everybody sould learn about this kind of thing. They will be better off for the future if they learn about this stuff.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Keynote Speaking

© 2023 Dr. Catlin Tucker

A survey conducted by the Associated Press has revealed that around 58% of parents feel that their child has been given the right amount of assignments. Educators are thrilled that the majority has supported the thought of allocating assignments, and they think that it is just right.

However, the question arises when students question the importance of giving assignments for better growth. Studies have shown that students often get unsuccessful in understanding the importance of assignments.

What key purpose does an assignment have? They often question how an assignment could be beneficial. Let us explain why a teacher thinks it is best to allot assignments. The essential functions of assigning tasks or giving assignments come from many intentions.

What is the Importance of Assignment- For Students

The importance of the assignment is not a new concept. The principle of allocating assignments stems from students’ learning process. It helps teachers to evaluate the student’s understanding of the subject. Assignments develop different practical skills and increase their knowledge base significantly. As per educational experts, mastering a topic is not an impossible task to achieve if they learn and develop these skills.

Cognitive enhancement

While doing assignments, students learn how to conduct research on subjects and comprise the data for using the information in the given tasks. Working on your assignment helps you learn diverse subjects, compare facts, and understand related concepts. It assists your brain in processing information and memorizing the required one. This exercise enhances your brain activity and directly impacts cognitive growth.

Ensured knowledge gain

When your teacher gives you an assignment, they intend to let you know the importance of the assignment. Working on it helps students to develop their thoughts on particular subjects. The idea supports students to get deep insights and also enriches their learning. Continuous learning opens up the window for knowledge on diverse topics. The learning horizon expanded, and students gained expertise in subjects over time.

Improve students’ writing pattern

Experts have revealed in a study that most students find it challenging to complete assignments as they are not good at writing. With proper assistance or teacher guidance, students can practice writing repetitively.

It encourages them to try their hands at different writing styles, and gradually they will improve their own writing pattern and increase their writing speed. It contributes to their writing improvement and makes it certain that students get a confidence boost.

Increased focus on studies

When your teachers allocate a task to complete assignments, it is somehow linked to your academic growth, especially for the university and grad school students. Therefore, it demands ultimate concentration to establish your insights regarding the topics of your assignments.

This process assists you in achieving good growth in your academic career and aids students in learning concepts quickly with better focus. It ensures that you stay focused while doing work and deliver better results.

Build planning & organization tactics

Planning and task organization are as necessary as writing the assignment. As per educational experts, when you work on assignments, you start planning to structurize the content and what type of information you will use and then organize your workflow accordingly. This process supports you in building your skill to plan things beforehand and organize them to get them done without hassles.

Adopt advanced research technique

Assignments expand the horizon of research skills among students. Learners explore different topics, gather diverse knowledge on different aspects of a particular topic, and use useful information on their tasks. Students adopt advanced research techniques to search for relevant information from diversified sources and identify correct facts and stats through these steps.

Augmenting reasoning & analytical skills

Crafting an assignment has one more sign that we overlook. Experts have enough proof that doing an assignment augments students’ reasoning abilities. They started thinking logically and used their analytical skills while writing their assignments. It offers clarity of the assignment subject, and they gradually develop their own perspective about the subject and offer that through assignments.

Boost your time management skills

Time management is one of the key skills that develop through assignments. It makes them disciplined and conscious of the value of time during their study years. However, students often delay as they get enough time. Set deadlines help students manage their time. Therefore, students understand that they need to invest their time wisely and also it’s necessary to complete assignments on time or before the deadline.

What is the Importance of Assignment- Other Functions From Teacher’s Perspective:

Develop an understanding between teacher and students .

Teachers ensure that students get clear instructions from their end through the assignment as it is necessary. They also get a glimpse of how much students have understood the subject. The clarity regarding the topic ensures that whether students have mastered the topic or need further clarification to eliminate doubts and confusion. It creates an understanding between the teaching faculty and learners.

Clarity- what is the reason for choosing the assignment

The Reason for the assignment allocated to students should be clear. The transparency of why teachers have assigned the task enables learners to understand why it is essential for their knowledge growth. With understanding, the students try to fulfill the objective. Overall, it fuels their thoughts that successfully evoke their insights.

Building a strong relationship- Showing how to complete tasks

When a teacher shows students how to complete tasks, it builds a strong student-teacher relationship. Firstly, students understand the teacher’s perspective and why they are entrusted with assignments. Secondly, it also encourages them to handle problems intelligently. This single activity also offers them the right direction in completing their tasks within the shortest period without sacrificing quality.

Get a view of what students have understood and their perspective

Assigning a task brings forth the students’ understanding of a particular subject. Moreover, when they attempt an assignment, it reflects their perspective on the specific subject. The process is related to the integration of appreciative learning principles. In this principle, teachers see how students interpret the subject. Students master the subject effectively, whereas teachers find the evaluation process relatively easy when done correctly.

Chance to clear doubts or confusion regarding the assignment

Mastering a subject needs practice and deep understanding from a teacher’s perspective. It could be possible only if students dedicate their time to assignments. While doing assignments, students could face conceptual difficulties, or some parts could confuse them. Through the task, teachers can clear their doubts and confusion and ensure that they fully understand what they are learning.

Offering individualistic provisions to complete an assignment

Students are divergent, and their thoughts are diverse in intelligence, temperaments, and aptitudes. Their differences reflect in their assignments and the insight they present. This process gives them a fair understanding of students’ future and their scope to grow. It also helps teachers to understand their differences and recognize their individualistic approaches.

Conclusion:

You have already become acquainted with the factors that translate what is the importance of assignments in academics. It plays a vital role in increasing the students’ growth multifold.

TutorBin is one of the best assignment help for students. Our experts connect students to improve their learning opportunities. Therefore, it creates scopes of effective education for all, irrespective of location, race, and education system. We have a strong team of tutors, and our team offers diverse services, including lab work, project reports, writing services, and presentations.

We often got queries like what is the importance of assignments to students. Likewise, if you have something similar in mind regarding your assignment & homework, comment below. We will answer you. In conclusion, we would like to remind you that if you want to know how our services help achieve academic success, search www.tutorbin.com . Our executive will get back to you shortly with their expert recommendations.

- E- Learning

- Online Learning

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked*

Comment * NEXT

Save my name and email in this browser for the next time I comment.

You May Also Like

50 Science Research Topics to Write an A+ Paper

What is Java?- Learn From Subject Experts

How to Write an Essay Proposal – Ultimate Guide with Examples

How to Write a Survey Paper: Guidance From Experts

Best 25 Macroeconomics Research Paper Topics in 2024

Online homework help, get homework help.

Get Answer within 15-30 minutes

Check out our free tool Math Problem Solver

About tutorbin, what do we do.

We offer an array of online homework help and other services for our students and tutors to choose from based on their needs and expertise. As an integrated platform for both tutors and students, we provide real time sessions, online assignment and homework help and project work assistance.

Who are we?

TutorBin is an integrated online homework help and tutoring platform serving as a one stop solution for students and online tutors. Students benefit from the experience and domain knowledge of global subject matter experts.

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Win a $1,000 gift certificate of your choice! ✨

Try This Awesome End-of-Year Activity: Students as Teachers

Let your students do the teaching for a change!

The end of school is the time of year most teachers dread. Kids are tired. Teachers are tired. There are 180,000 things on everyone’s mind. The last thing ANYONE wants to do is continue with the same routines. We all need a little break from the monotony! I love the end of the year because it is a golden opportunity to review the year’s work with some serious projects and group work. My favorite activity? Students as teachers.

Students as Teachers

My fourth-grade students had a BLAST the other day teaching our third graders a preview of what they’d learn in fourth grade. They exploded bags, dropped eggs, created an inviting restaurant for the perfect party, decorated a beautiful pet shop, and used motivating texts to inspire serious goal-setting.

They produced anchor charts, graphic organizers, student work pages, rubrics, and I-Can statements galore. It was a rewarding experience and an excellent review. Not to mention that it freed up the third-grade teacher for about an hour and gave me a chance to enjoy my students’ leadership skills.

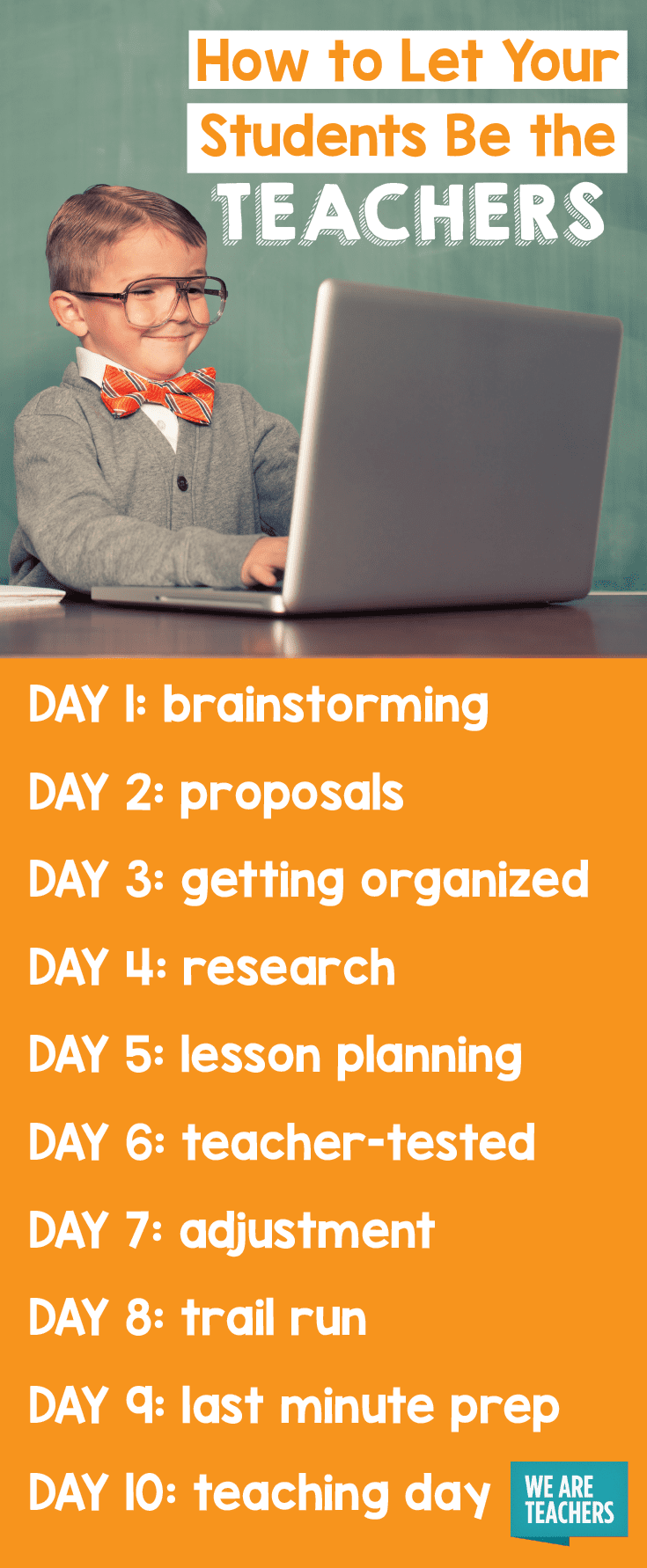

The whole process of preparing students as teachers took about two weeks. Everything was student planned and designed, and covered topics from throughout the year. Here is the basic timeline of how we prepared.

Day 1: Brainstorming

I split my 24 students into four groups—math, science, reading and writing. I chose students who are really strong in each subject to be group leaders. The rest I placed according to their personality and strengths. I introduced the basic concepts of teaching, over which the kids went CRAZY! They were so excited about being in control!

We talked about the importance of choosing a topic we had learned in fourth grade. The kids used their journals to figure out what they’d like to teach. They spent time brainstorming and coming up with a proposal. I showed them the rubric and timeline to make sure they understood the expectations.

Day 2: Proposals

I checked in with each group’s progress. Writing knew exactly what they wanted—they love animals, so they wanted to make a pet shop. I asked them to come up with a proposal for what students might do. Reading was full of very ambitious kids—they wanted to focus on goal setting. Math decided they wanted to plan a party but weren’t quite sure how to tie it to the curriculum.

We worked together to come up with the idea of analyzing the cost. They’d make decisions on what to order, figure out total cost, and divide it by three people hosting and paying for the party. Science wanted to do something on changes but didn’t quite know what. I remembered a super fun lab I’d done in the past with physical and chemical changes, and showed them some ideas online. They were thrilled!

Day 3: Getting Organized

The goal of the day was to write lesson objectives, design a graphic organizer, and come up with the basic flow for each group’s lesson. I gave them about half an hour to work then told them I would be checking in on their progress. Some of the teams were having NO problems getting going, while others struggled a bit. I spent time with each group, asking guiding questions and helping them focus on what they would be doing. Reading decided to do text structure with an article on goal setting, then move into creating goals. Writing decided to do a persuasive letter, with an emphasis on finding solid reasons for their parents to let them get pets from the pet store. Science decided to run labs to explore the difference between physical and chemical changes.

Day 4: Research

I told students they couldn’t teach something they didn’t understand. Each group was responsible for finding a minimum of four facts or ideas related to their topic. ADVERTISEMENT

Day 5: Lesson Planning

I gave students their planning template. They had to turn in a lesson plan including a graphic organizer and some work required.

Day 6: Teacher-Tested

I took the worksheets students turned in and printed them out. Then I taught each lesson (exactly as it was prepared) to the whole class. Some of it was awkward, some of it took FOREVER, and some was super fun. (Have you ever told a room full of kids to chuck an egg on the floor? It’s a trip!) After each lesson, we had a class debriefing where we talked about what went well and what could be better.

Day 7: Adjustment

Students regrouped and adjusted their plans. They also came up with rubrics to use to grade their students.

Day 8: Trail Run

One of my lovely team members brought her students in so we could try our lessons. Writing and math went well and needed no adjustments. Science discovered they needed anchor charts to teach from before expecting students to analyze the results of the labs. Reading was a complete flop. They had planned way too much and it was pretty boring! Luckily, my teammate had a couple of books about goal setting, so the reading team did a last second change-up. They worked together to come up with a new plan—analyzing the theme of the story and then setting goals. It turned out to be great!

Day 9: Last Minute Prep

I-Can statements went on chart paper, anchor charts were finalized, work pages and rubrics were polished, and group roles were ironed out. They did a couple trial runs to see how it would go.

Day 10: Teaching Day

One awesome third grade teacher volunteered as tribute and brought her kids, divided into four groups, to our room. My fourth graders were set up in separate parts of the room, ready to go.

Before we began, I laid out the expectations for the third and fourth graders. Then I set the timer for 16 minutes, and off they went. It was so fun to see how incredibly engaged the third graders were! The fourth graders really excelled as leaders. I enjoyed seeing how some of the students I would not have expected to be outgoing really put themselves out there and took ownership over their project.

The third grade teacher and I walked around the room and observed (with only occasional help given). The younger kids rotated through all four stations in the room, working hard in each one. After they left, the fourth graders used the rubrics they’d created to grade their students. They were so pleased with themselves!

Students as teachers was a super fun, low-prep activity. It took up quite a bit of that extra end-of-year time in a meaningful way. It allowed me to see some of the third graders that may be in my class next year, and let them have a small preview of what life will be like in fourth grade.

There were a couple of things I would do differently next time we do students as teachers. I only allotted 16 minutes per station, worrying about lessons dragging on and kids becoming disengaged. However, it was too short of a time, especially for everything my fourth graders had planned. Next time, I would also have my “teachers” plan some extension activities for early finishers.

My one big takeaway? Sometimes it’s good to sit back and let the kids shine. They’ll surprise you.

You Might Also Like

57 Fun End-of-Year Activities and Assignments

Wrap up the year on a happy note. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

Teaching, Learning, & Professional Development Center

- Teaching Resources

- TLPDC Teaching Resources

How Do I Create Meaningful and Effective Assignments?

Prepared by allison boye, ph.d. teaching, learning, and professional development center.

Assessment is a necessary part of the teaching and learning process, helping us measure whether our students have really learned what we want them to learn. While exams and quizzes are certainly favorite and useful methods of assessment, out of class assignments (written or otherwise) can offer similar insights into our students' learning. And just as creating a reliable test takes thoughtfulness and skill, so does creating meaningful and effective assignments. Undoubtedly, many instructors have been on the receiving end of disappointing student work, left wondering what went wrong… and often, those problems can be remedied in the future by some simple fine-tuning of the original assignment. This paper will take a look at some important elements to consider when developing assignments, and offer some easy approaches to creating a valuable assessment experience for all involved.

First Things First…

Before assigning any major tasks to students, it is imperative that you first define a few things for yourself as the instructor:

- Your goals for the assignment . Why are you assigning this project, and what do you hope your students will gain from completing it? What knowledge, skills, and abilities do you aim to measure with this assignment? Creating assignments is a major part of overall course design, and every project you assign should clearly align with your goals for the course in general. For instance, if you want your students to demonstrate critical thinking, perhaps asking them to simply summarize an article is not the best match for that goal; a more appropriate option might be to ask for an analysis of a controversial issue in the discipline. Ultimately, the connection between the assignment and its purpose should be clear to both you and your students to ensure that it is fulfilling the desired goals and doesn't seem like “busy work.” For some ideas about what kinds of assignments match certain learning goals, take a look at this page from DePaul University's Teaching Commons.

- Have they experienced “socialization” in the culture of your discipline (Flaxman, 2005)? Are they familiar with any conventions you might want them to know? In other words, do they know the “language” of your discipline, generally accepted style guidelines, or research protocols?

- Do they know how to conduct research? Do they know the proper style format, documentation style, acceptable resources, etc.? Do they know how to use the library (Fitzpatrick, 1989) or evaluate resources?

- What kinds of writing or work have they previously engaged in? For instance, have they completed long, formal writing assignments or research projects before? Have they ever engaged in analysis, reflection, or argumentation? Have they completed group assignments before? Do they know how to write a literature review or scientific report?

In his book Engaging Ideas (1996), John Bean provides a great list of questions to help instructors focus on their main teaching goals when creating an assignment (p.78):

1. What are the main units/modules in my course?

2. What are my main learning objectives for each module and for the course?

3. What thinking skills am I trying to develop within each unit and throughout the course?

4. What are the most difficult aspects of my course for students?

5. If I could change my students' study habits, what would I most like to change?

6. What difference do I want my course to make in my students' lives?

What your students need to know

Once you have determined your own goals for the assignment and the levels of your students, you can begin creating your assignment. However, when introducing your assignment to your students, there are several things you will need to clearly outline for them in order to ensure the most successful assignments possible.

- First, you will need to articulate the purpose of the assignment . Even though you know why the assignment is important and what it is meant to accomplish, you cannot assume that your students will intuit that purpose. Your students will appreciate an understanding of how the assignment fits into the larger goals of the course and what they will learn from the process (Hass & Osborn, 2007). Being transparent with your students and explaining why you are asking them to complete a given assignment can ultimately help motivate them to complete the assignment more thoughtfully.

- If you are asking your students to complete a writing assignment, you should define for them the “rhetorical or cognitive mode/s” you want them to employ in their writing (Flaxman, 2005). In other words, use precise verbs that communicate whether you are asking them to analyze, argue, describe, inform, etc. (Verbs like “explore” or “comment on” can be too vague and cause confusion.) Provide them with a specific task to complete, such as a problem to solve, a question to answer, or an argument to support. For those who want assignments to lead to top-down, thesis-driven writing, John Bean (1996) suggests presenting a proposition that students must defend or refute, or a problem that demands a thesis answer.

- It is also a good idea to define the audience you want your students to address with their assignment, if possible – especially with writing assignments. Otherwise, students will address only the instructor, often assuming little requires explanation or development (Hedengren, 2004; MIT, 1999). Further, asking students to address the instructor, who typically knows more about the topic than the student, places the student in an unnatural rhetorical position. Instead, you might consider asking your students to prepare their assignments for alternative audiences such as other students who missed last week's classes, a group that opposes their position, or people reading a popular magazine or newspaper. In fact, a study by Bean (1996) indicated the students often appreciate and enjoy assignments that vary elements such as audience or rhetorical context, so don't be afraid to get creative!

- Obviously, you will also need to articulate clearly the logistics or “business aspects” of the assignment . In other words, be explicit with your students about required elements such as the format, length, documentation style, writing style (formal or informal?), and deadlines. One caveat, however: do not allow the logistics of the paper take precedence over the content in your assignment description; if you spend all of your time describing these things, students might suspect that is all you care about in their execution of the assignment.

- Finally, you should clarify your evaluation criteria for the assignment. What elements of content are most important? Will you grade holistically or weight features separately? How much weight will be given to individual elements, etc? Another precaution to take when defining requirements for your students is to take care that your instructions and rubric also do not overshadow the content; prescribing too rigidly each element of an assignment can limit students' freedom to explore and discover. According to Beth Finch Hedengren, “A good assignment provides the purpose and guidelines… without dictating exactly what to say” (2004, p. 27). If you decide to utilize a grading rubric, be sure to provide that to the students along with the assignment description, prior to their completion of the assignment.

A great way to get students engaged with an assignment and build buy-in is to encourage their collaboration on its design and/or on the grading criteria (Hudd, 2003). In his article “Conducting Writing Assignments,” Richard Leahy (2002) offers a few ideas for building in said collaboration:

• Ask the students to develop the grading scale themselves from scratch, starting with choosing the categories.

• Set the grading categories yourself, but ask the students to help write the descriptions.

• Draft the complete grading scale yourself, then give it to your students for review and suggestions.

A Few Do's and Don'ts…

Determining your goals for the assignment and its essential logistics is a good start to creating an effective assignment. However, there are a few more simple factors to consider in your final design. First, here are a few things you should do :

- Do provide detail in your assignment description . Research has shown that students frequently prefer some guiding constraints when completing assignments (Bean, 1996), and that more detail (within reason) can lead to more successful student responses. One idea is to provide students with physical assignment handouts , in addition to or instead of a simple description in a syllabus. This can meet the needs of concrete learners and give them something tangible to refer to. Likewise, it is often beneficial to make explicit for students the process or steps necessary to complete an assignment, given that students – especially younger ones – might need guidance in planning and time management (MIT, 1999).

- Do use open-ended questions. The most effective and challenging assignments focus on questions that lead students to thinking and explaining, rather than simple yes or no answers, whether explicitly part of the assignment description or in the brainstorming heuristics (Gardner, 2005).

- Do direct students to appropriate available resources . Giving students pointers about other venues for assistance can help them get started on the right track independently. These kinds of suggestions might include information about campus resources such as the University Writing Center or discipline-specific librarians, suggesting specific journals or books, or even sections of their textbook, or providing them with lists of research ideas or links to acceptable websites.

- Do consider providing models – both successful and unsuccessful models (Miller, 2007). These models could be provided by past students, or models you have created yourself. You could even ask students to evaluate the models themselves using the determined evaluation criteria, helping them to visualize the final product, think critically about how to complete the assignment, and ideally, recognize success in their own work.

- Do consider including a way for students to make the assignment their own. In their study, Hass and Osborn (2007) confirmed the importance of personal engagement for students when completing an assignment. Indeed, students will be more engaged in an assignment if it is personally meaningful, practical, or purposeful beyond the classroom. You might think of ways to encourage students to tap into their own experiences or curiosities, to solve or explore a real problem, or connect to the larger community. Offering variety in assignment selection can also help students feel more individualized, creative, and in control.

- If your assignment is substantial or long, do consider sequencing it. Far too often, assignments are given as one-shot final products that receive grades at the end of the semester, eternally abandoned by the student. By sequencing a large assignment, or essentially breaking it down into a systematic approach consisting of interconnected smaller elements (such as a project proposal, an annotated bibliography, or a rough draft, or a series of mini-assignments related to the longer assignment), you can encourage thoughtfulness, complexity, and thoroughness in your students, as well as emphasize process over final product.

Next are a few elements to avoid in your assignments:

- Do not ask too many questions in your assignment. In an effort to challenge students, instructors often err in the other direction, asking more questions than students can reasonably address in a single assignment without losing focus. Offering an overly specific “checklist” prompt often leads to externally organized papers, in which inexperienced students “slavishly follow the checklist instead of integrating their ideas into more organically-discovered structure” (Flaxman, 2005).

- Do not expect or suggest that there is an “ideal” response to the assignment. A common error for instructors is to dictate content of an assignment too rigidly, or to imply that there is a single correct response or a specific conclusion to reach, either explicitly or implicitly (Flaxman, 2005). Undoubtedly, students do not appreciate feeling as if they must read an instructor's mind to complete an assignment successfully, or that their own ideas have nowhere to go, and can lose motivation as a result. Similarly, avoid assignments that simply ask for regurgitation (Miller, 2007). Again, the best assignments invite students to engage in critical thinking, not just reproduce lectures or readings.

- Do not provide vague or confusing commands . Do students know what you mean when they are asked to “examine” or “discuss” a topic? Return to what you determined about your students' experiences and levels to help you decide what directions will make the most sense to them and what will require more explanation or guidance, and avoid verbiage that might confound them.

- Do not impose impossible time restraints or require the use of insufficient resources for completion of the assignment. For instance, if you are asking all of your students to use the same resource, ensure that there are enough copies available for all students to access – or at least put one copy on reserve in the library. Likewise, make sure that you are providing your students with ample time to locate resources and effectively complete the assignment (Fitzpatrick, 1989).

The assignments we give to students don't simply have to be research papers or reports. There are many options for effective yet creative ways to assess your students' learning! Here are just a few:

Journals, Posters, Portfolios, Letters, Brochures, Management plans, Editorials, Instruction Manuals, Imitations of a text, Case studies, Debates, News release, Dialogues, Videos, Collages, Plays, Power Point presentations

Ultimately, the success of student responses to an assignment often rests on the instructor's deliberate design of the assignment. By being purposeful and thoughtful from the beginning, you can ensure that your assignments will not only serve as effective assessment methods, but also engage and delight your students. If you would like further help in constructing or revising an assignment, the Teaching, Learning, and Professional Development Center is glad to offer individual consultations. In addition, look into some of the resources provided below.

Online Resources

“Creating Effective Assignments” http://www.unh.edu/teaching-excellence/resources/Assignments.htm This site, from the University of New Hampshire's Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, provides a brief overview of effective assignment design, with a focus on determining and communicating goals and expectations.

Gardner, T. (2005, June 12). Ten Tips for Designing Writing Assignments. Traci's Lists of Ten. http://www.tengrrl.com/tens/034.shtml This is a brief yet useful list of tips for assignment design, prepared by a writing teacher and curriculum developer for the National Council of Teachers of English . The website will also link you to several other lists of “ten tips” related to literacy pedagogy.

“How to Create Effective Assignments for College Students.” http:// tilt.colostate.edu/retreat/2011/zimmerman.pdf This PDF is a simplified bulleted list, prepared by Dr. Toni Zimmerman from Colorado State University, offering some helpful ideas for coming up with creative assignments.

“Learner-Centered Assessment” http://cte.uwaterloo.ca/teaching_resources/tips/learner_centered_assessment.html From the Centre for Teaching Excellence at the University of Waterloo, this is a short list of suggestions for the process of designing an assessment with your students' interests in mind. “Matching Learning Goals to Assignment Types.” http://teachingcommons.depaul.edu/How_to/design_assignments/assignments_learning_goals.html This is a great page from DePaul University's Teaching Commons, providing a chart that helps instructors match assignments with learning goals.

Additional References Bean, J.C. (1996). Engaging ideas: The professor's guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fitzpatrick, R. (1989). Research and writing assignments that reduce fear lead to better papers and more confident students. Writing Across the Curriculum , 3.2, pp. 15 – 24.

Flaxman, R. (2005). Creating meaningful writing assignments. The Teaching Exchange . Retrieved Jan. 9, 2008 from http://www.brown.edu/Administration/Sheridan_Center/pubs/teachingExchange/jan2005/01_flaxman.pdf

Hass, M. & Osborn, J. (2007, August 13). An emic view of student writing and the writing process. Across the Disciplines, 4.

Hedengren, B.F. (2004). A TA's guide to teaching writing in all disciplines . Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's.

Hudd, S. S. (2003, April). Syllabus under construction: Involving students in the creation of class assignments. Teaching Sociology , 31, pp. 195 – 202.

Leahy, R. (2002). Conducting writing assignments. College Teaching , 50.2, pp. 50 – 54.

Miller, H. (2007). Designing effective writing assignments. Teaching with writing . University of Minnesota Center for Writing. Retrieved Jan. 9, 2008, from http://writing.umn.edu/tww/assignments/designing.html

MIT Online Writing and Communication Center (1999). Creating Writing Assignments. Retrieved January 9, 2008 from http://web.mit.edu/writing/Faculty/createeffective.html .

Contact TTU

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply —use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.