- Read TIME’s Original Review of <i>Nineteen Eighty-Four</i>

Read TIME’s Original Review of Nineteen Eighty-Four

G eorge Orwell was already an established literary star when his masterwork Nineteen Eighty-Four was published on this day in 1949, but that didn’t stop TIME’s reviewer from being pleasantly surprised by the book. After all, even the expectation that a book would be good doesn’t mean one can’t be impressed when it turns out to be, as TIME put it, “absolutely super.”

One of the reasons, the review suggested, was Orwell’s bet that his fictional dystopia would not actually seem so foreign to contemporary readers. They would easily recognize many elements of the fictional world that TIME summed up as such:

In Britain 1984 A.D., no one would have suspected that Winston and Julia were capable of crimethink (dangerous thoughts) or a secret desire for ownlife (individualism). After all, Party-Member Winston Smith was one of the Ministry of Truth’s most trusted forgers; he had always flung himself heart & soul into the falsification of government statistics. And Party-Member Julia was outwardly so goodthinkful (naturally orthodox) that, after a brilliant girlhood in the Spies, she became active in the Junior Anti-Sex League and was snapped up by Pornosec, a subsection of the government Fiction Department that ground out happy-making pornography for the masses. In short, the grim, grey London Times could not have been referring to Winston and Julia when it snorted contemptuously: “Old-thinkers unbellyfeel Ingsoc,” i.e., “Those whose ideas were formed before the Revolution cannot have a full emotional understanding of the principles of English Socialism.” How Winston and Julia rebelled, fell in love and paid the penalty in the terroristic world of tomorrow is the thread on which Britain’s George Orwell has spun his latest and finest work of fiction. In Animal Farm (TIME, Feb. 4, 1946,) Orwell parodied the Communist system in terms of barnyard satire; but in 1984 … there is not a smile or a jest that does not add bitterness to Orwell’s utterly depressing vision of what the world may be in 35 years’ time.

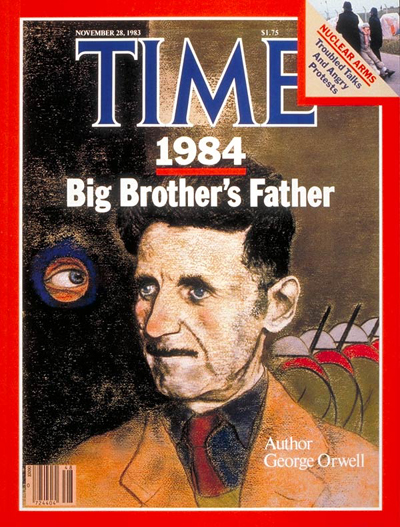

Decades later, as the real-life 1984 approached, TIME dedicated a cover story to Orwell’s earlier vision of what that year could have been like. “That Year Is Almost Here,” the headline proclaimed . But obsessing over how it matched up to its fictional depiction was missing the point, the article posited. “The proper way to remember George Orwell, finally, is not as a man of numbers—1984 will pass, not Nineteen Eighty–Four—but as a man of letters,” wrote Paul Gray, “who wanted to change the world by changing the word.”

Read the full 1949 review, here in the TIME Vault: Where the Rainbow Ends

LIST: The 100 Best Young Adult Books of All Time

More Must-Reads from TIME

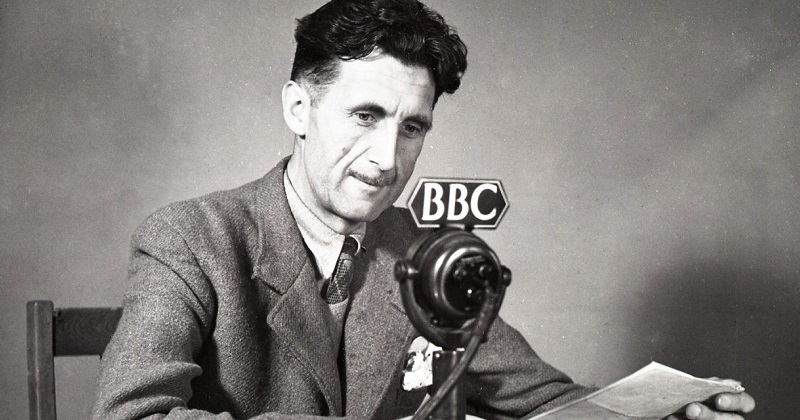

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- The Reintroduction of Kamala Harris

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Write to Lily Rothman at [email protected]

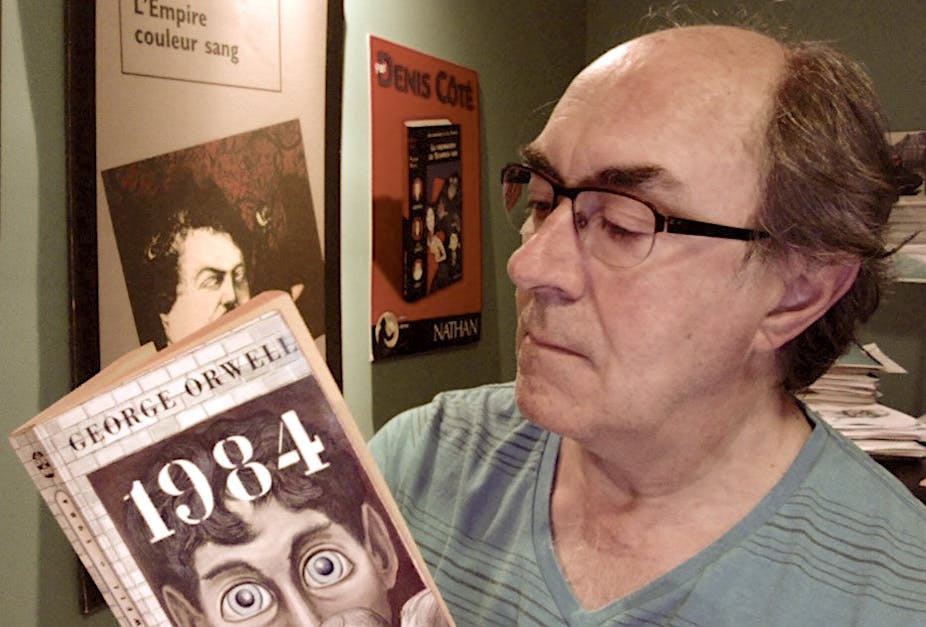

What Orwell’s ‘1984’ tells us about today’s world, 70 years after it was published

Assistant Professor of Cinema and Media Studies, University of Washington

Disclosure statement

Stephen Groening does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Washington provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Seventy years ago, Eric Blair, writing under a pseudonym George Orwell, published “1984,” now generally considered a classic of dystopian fiction .

The novel tells the story of Winston Smith, a hapless middle-aged bureaucrat who lives in Oceania, where he is governed by constant surveillance. Even though there are no laws, there is a police force, the “Thought Police,” and the constant reminders, on posters, that “Big Brother Is Watching You.”

Smith works at the Ministry of Truth, and his job is to rewrite the reports in newspapers of the past to conform with the present reality. Smith lives in a constant state of uncertainty; he is not sure the year is in fact 1984.

Although the official account is that Oceania has always been at war with Eurasia, Smith is quite sure he remembers that just a few years ago they had been at war with Eastasia, who has now been proclaimed their constant and loyal ally . The society portrayed in “1984” is one in which social control is exercised through disinformation and surveillance.

As a scholar of television and screen culture , I argue that the techniques and technologies described in the novel are very much present in today’s world.

‘1984’ as history

One of the key technologies of surveillance in the novel is the “telescreen,” a device very much like our own television.

The telescreen displays a single channel of news, propaganda and wellness programming. It differs from our own television in two crucial respects: It is impossible to turn off and the screen also watches its viewers.

The telescreen is television and surveillance camera in one. In the novel, the character Smith is never sure if he is being actively monitored through the telescreen.

Orwell’s telescreen was based in the technologies of television pioneered prior to World War II and could hardly be seen as science fiction. In the 1930s Germany had a working videophone system in place , and television programs were already being broadcast in parts of the United States, Great Britain and France .

Past, present and future

The dominant reading of “1984” has been that it was a dire prediction of what could be. In the words of Italian essayist Umberto Eco, “at least three-quarters of what Orwell narrates is not negative utopia, but history .”

Additionally, scholars have also remarked how clearly “1984” describes the present.

In 1949, when the novel was written, Americans watched on average four and a half hours of television a day; in 2009, almost twice that . In 2017, television watching was slightly down, to eight hours, more time than we spent asleep .

In the U.S. the information transmitted over television screens came to constitute a dominant portion of people’s social and psychological lives.

‘1984’ as present day

In the year 1984, however, there was much self-congratulatory coverage in the U.S. that the dystopia of the novel had not been realized. But media studies scholar Mark Miller argued how the famous slogan from the book, “Big Brother Is Watching You” had been turned to “Big Brother is you, watching” television .

Miller argued that television in the United States teaches a different kind of conformity than that portrayed in the novel. In the novel, the telescreen is used to produce conformity to the Party. In Miller’s argument, television produces conformity to a system of rapacious consumption – through advertising as well as a focus on the rich and famous. It also promotes endless productivity, through messages regarding the meaning of success and the virtues of hard work .

Many viewers conform by measuring themselves against what they see on television, such as dress, relationships and conduct. In Miller’s words, television has “set the standard of habitual self-scrutiny.”

The kind of paranoid worry possessed by Smith in the novel – that any false move or false thought will bring the thought police – instead manifests in television viewers that Miller describes as an “inert watchfulness.” In other words, viewers watch themselves to make sure they conform to those others they see on the screen.

This inert watchfulness can exist because television allows viewers to watch strangers without being seen. Scholar Joshua Meyrowitz has shown that the kinds of programming which dominate U.S television – news, sitcoms, dramas – have normalized looking into the private lives of others .

Controlling behavior

Alongside the steady rise of “reality TV,” beginning in the ‘60s with “Candid Camera,” “An American Family,” “Real People,” “Cops” and “The Real World,” television has also contributed to the acceptance of a kind of video surveillance.

For example, it might seem just clever marketing that one of the longest-running and most popular reality television shows in the world is entitled “ Big Brother .” The show’s nod to the novel invokes the kind of benevolent surveillance that “Big Brother” was meant to signify: “We are watching you and we will take care of you.”

But Big Brother, as a reality show, is also an experiment in controlling and modifying behavior. By asking participants to put their private lives on display, shows such as “Big Brother” encourage self-scrutiny and behaving according to perceived social norms or roles that challenge those perceived norms .

The stress of performing 24/7 on “Big Brother” has led the show to employ a team of psychologists .

Television scholar Anna McCarthy and others have shown that the origins of reality television can be traced back to social psychology and behavioral experiments in the aftermath of World War II, which were designed to better control people.

Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram , for example, was influenced by “Candid Camera.”

In the “Candid Camera” show, cameras were concealed in places where they could film people in unusual situations. Milgram was fascinated with “Candid Camera,” and he used a similar model for his experiments – his participants were not aware that they were being watched or that it was part of an experiment .

Like many others in the aftermath of World War II, Milgram was interested in what could compel large numbers of people to “follow orders” and participate in genocidal acts. His “obedience experiments” found that a high proportion of participants obeyed instructions from an established authority figure to harm another person, even if reluctantly .

While contemporary reality TV shows do not order participants to directly harm each other, they are often set up as a small-scale social experiment that often involves intense competition or even cruelty.

Surveillance in daily life

And, just like in the novel, ubiquitous video surveillance is already here.

Closed-circuit television exist in virtually every area of American life, from transportation hubs and networks , to schools , supermarkets , hospitals and public sidewalks , not to mention law enforcement officers and their vehicles .

Surveillance footage from these cameras is repurposed as the raw material of television, mostly in the news but also in shows like “America’s Most Wanted,” “Right This Minute” and others. Many viewers unquestioningly accept this practice as legitimate .

The friendly face of surveillance

Reality television is the friendly face of surveillance. It helps viewers think that surveillance happens only to those who choose it or to those who are criminals. In fact, it is part of a culture of widespread television use, which has brought about what Norwegian criminologist Thomas Mathiesen called the “viewer society” – in which the many watch the few.

For Mathiesen, the viewer society is merely the other side of the surveillance society – described so aptly in Orwell’s novel – where a few watch the many.

[ Expertise in your inbox. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter and get a digest of academic takes on today’s news, every day. ]

- Surveillance

- George Orwell

- 1984 (novel)

- Big Brother

- Scientific experiments

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 188,900 academics and researchers from 5,031 institutions.

Register now

By George Orwell

George Orwell opens his stunning novel '1984' novel by telling the reader that the “clocks were striking thirteen”. If this isn’t an opening line for the ages, I don’t know what is.

- Insightful critique of totalitarianism.

- Engaging and thought-provoking storyline.

- Relevant exploration of power and control.

- Depressingly bleak and pessimistic tone.

- Somewhat dated language and concepts.

- Slow pacing in certain sections.

Bottom Line

" 1984 " remains a profoundly impactful and thought-provoking novel, offering a chilling critique of totalitarianism and the dangers of unchecked power. Despite its bleak tone and sometimes dated language, the compelling narrative and enduring relevance of its themes make it a must-read for anyone interested in political and social commentary. Orwell's masterful portrayal of a dystopian future serves as a powerful warning about the potential consequences of sacrificing freedom for security.

Rating [book_review_rating]

Continue down for the complete review to 1984

Article written by Emma Baldwin

B.A. in English, B.F.A. in Fine Art, and B.A. in Art Histories from East Carolina University.

As new entrants into the world of 1984, we are immediately introduced to the character of Winston Smith , a small, rough-skinned, sickly member of the Outer Party. He’s just arrived at his dreary apartment from work where he’s greeted by the blaring noise of his telescreen , a permanent installation in his home that works twofold. He watches it, and it watches him.

I found it disconcertingly easy to imagine, in our modern world, technology is utilized in such an all-encompassing, and eventually normalized fashion. The residents of London, Airstrip One , Oceania, are used to constant surveillance. It is how most of them have lived their whole lives and the majority would advocate for its continuous.

The totalitarian regime that reigns over Winston’s vile, cold and dirty futurist London, controls everything, right down to the thoughts in its citizen’s heads. At least, that’s what it would like. Luckily for we the readers, Winston Smith is not like the other party members, those he deems as mindless, brainwashed fools, devoted mind and body to the Party, Big Brother (the dictatorial figure/mascot of the regime who may or may not actually exist) and the principles of INGSOC (English Socialism). Through Winston’s perspective, we are allowed to experience his irritation, fury, and exasperation with the other Party members and the proles who live in the slums outside the city center.

Daily Terrors in Winston Smith’s World

While explaining the terror he exists in, day in and day out, Winston takes comfort in the fact that the small space within his head is his own . That is until the Thought Police catch up with him. Everything else, what he does, says, and how he appears, is bent to the will of the Party.

The first part of 1984 (which is divided into three sections) is an incredible achievement of world-building. Orwell sucks the reader right into the horrors of Winston’s world by moving through the minutia of his life. Winston is responsible for the re-writing of history, it is by his hand, (and he admits, likely hundreds of others) that newspaper articles are rephrased, remade, and created in order to cast the government in the best light possible.

Perhaps the most chilling and shocking aspect of 1984 is the way that somethings, although noted by Winston as wrong and disturbing, have become commonplace. The rewriting of history is only one example. Winston lives in constant fear that someday, maybe that afternoon, or five years from now, he and Julia (a young woman with whom he begins an affair) are going to be “vaporized”. Death weighs heavily on Winston’s world and as a reader, I found myself experiencing some of that fear as well. Winston’s life, as he takes more risks, becomes at once rife with paranoia and incredibly, more commonly filled with moments of peace.

The Drama of Very Human Characters

As a human being, Orwell writes Winston Smith believably. So much so I found myself having arguments with his character as he tried to come to terms with changes (such as when Oceania changed the superpower it was at war with) or when he was relishing in the knowledge the O’Brien was, in fact, a member of the resistance. It is easy enough, I found, to search for the same grains of hope Winston did within the second part of 1984.

If I had to choose one moment from the novel that I know will stick with me, it is the scene in the room above Mr. Charrington ’s shop in which Julia and Winston are musing over their shared, doomed fate. They say to one another “We are the dead” and in mimicry of their conversion, Mr. Charrington (who is revealed to be a spy for the Thought Police) calls out from behind a photo, “You are the dead”. Utterly chilling, even now, recalling that moment I find myself experiencing something of what these two characters felt.

It is the culmination of the previous two parts of 1984 in which Winston waits to be caught, captured, and tortured. Now, he and Julie both know and the reader knows, that this is the end. He is surely going to be dragged off to the Ministry of Love and tortured to death. Perhaps he’ll be released on a temporary basis, as other “criminals” have been. But, there is no getting away from the Party. It sees, hears, and knows all. At this moment, it caught up to Winston Smith. All his vague hopes for the future vanish.

The Concluding Pages of 1984

The last section of 1984 felt like looking behind the curtain. There was a great deal of satisfaction finally knowing what goes on within the Ministry of Love and it was just as horrifying as I imagined. They engage in all forms of torture, mental and physical.

When I first read the section in which Winston is forced to confront his greatest fear in Room 101 I found myself surprised by how complex, knowledgeable, and conniving the Party was in its research into Winston’s life and weak points. Thinking back on it now, it couldn’t have been any other way. Of course, O’Brien was working as a double agent, of course, the Party knew all along what Winston and Julie were doing and planning, and of course, in the end, they got what they wanted—for Winston to love Big Brother.

1984 Book Review: George Orwell's Stunning Novel

Book Title: 1984

Book Description: 1984, is a dystopian novel that tells the story of Winston Smith and warns of the dangers of a totalitarian government that rules through fear, surveillance, propaganda and brainwashing.

Book Author: George Orwell

Book Edition: Signet Classics Edition

Book Format: Paperback

Publisher - Organization: Secker & Warburg

Date published: June 8, 1949

Illustrator: Paul Rivoche

ISBN: 0451524934

Number Of Pages: 328

- Writing Style

- Lasting Effect on Reader

1984 Review

1984 is a book that you’re going to remember. From its opening lines to the various revelations about the Party and it’s means of governing its citizens a reader is met with constant twists and turns. Each one is more disturbing than the one before it. You would not be wrong if while reading 1984 you found yourself drawing comparisons between contemporary/historical society and the world that Winston Smith lives in. This book is just as relevant today as it was when Orwell finished it in 1948. One reading does not do this novel justice. On the second, third, or even fourth time that one learns about Emmanuel Goldstein, Big Brother, the Ministries, and every other memorable element of the book, more is revealed.

- A plot that keeps the reader guessing–incredibly engaging

- Original, yet relatable characters

- Disturbingly relevant

- Big Brother verges on a caricature

- Readers are left hanging without a definite conclusion to the novel

- Misogynistic undertones that go unaddressed

Step into the dystopian world of George Orwell's 1984! Are you ready to test your knowledge of Big Brother, Newspeak, and Oceania? Take the challenge now and prove your mastery of Orwell's 1984!

What is the main purpose of the Ministry of Love?

What does the paperweight symbolize for Winston?

How does Winston feel when he first meets Julia?

What is the role of the Thought Police in 1984?

What does Winston discover about Mr. Charrington?

What happens to Winston at the end of the novel?

What does the character of O'Brien represent in the novel?

Who does Winston believe has the power to overthrow the Party?

What is the significance of the song “Under the spreading chestnut tree”?

Which of the following best describes the concept of doublethink?

What is the name of the Party's leader in 1984?

What is the official language of Oceania?

What is the nature of Winston’s job at the Ministry of Truth?

What does the telescreen symbolize in 1984?

What is the significance of the phrase "2 + 2 = 5" in the novel?

What is the primary function of the Ministry of Plenty?

What does Winston read to learn about the Party’s true nature?

Where does Winston work?

Who is the supposed leader of the Brotherhood?

Who betrays Winston and Julia?

Your score is

The average score is 65%

Join Book Analysis for Free!

Exclusive to Members

Save Your Favorites

Free newsletter, comment with literary experts.

About Emma Baldwin

Emma Baldwin, a graduate of East Carolina University, has a deep-rooted passion for literature. She serves as a key contributor to the Book Analysis team with years of experience.

I just finished reading 1984 by George Orwell. It is my first reading (I’m 76), and all I could think about was today’s sociological and political events. It was scary being so foreboding in 2022 having been published in 1949! At times I had to stop reading. My heart hurt; my mind grew fearful; my sense of reality began to melt! Read it! I plan to read it again!

Thanks for the comment Linda!

It’s remarkable how Orwell’s work, conceived in 1949, echoes so loudly in today’s world, stirring fear, concern, and reflection.

It’s definitely worth reading it again.

About the Book

George Orwell

George Orwell is remembered today for his social criticism, controversial beliefs, and his novels ' Animal Farm ' and '1984'.

Orwell Facts

Explore ten of the most interesting facts about Orwell’s life, habits, and passions.

Orwell's Best Books

Explore the nine books George Orwell wrote.

Democratic Socialism

Was George Orwell a Socialist?

Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past. George Orwell

Discover literature, enjoy exclusive perks, and connect with others just like yourself!

Start the Conversation. Join the Chat.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Orwell on the Future

George Orwell’s new novel “Nineteen Eighty-Four” (Harcourt, Brace), confirms its author in the special, honorable place he holds in our intellectual life. Orwell’s native gifts are perhaps not of a transcendent kind; they have their roots in a quality of mind that ought to be as frequent as it is modest. This quality may be described as a sort of moral centrality, a directness of relation to moral—and political—fact, and it is so far from being frequent in our time that Orwell’s possession of it seems nearly unique. Orwell is an intellectual to his fingertips, but he is far removed from both the Continental and the American type of intellectual. The turn of his mind is what used to be thought of as peculiarly “English.” He is indifferent to the allurements of elaborate theory and of extreme sensibility. The medium of his thought is common sense, and his commitment to intellect is fortified by an old-fashioned faith that the truth can be got at, that we can, if we actually want to, see the object as it really is. This faith in the power of mind rests in part on Orwell’s willingness, rare among contemporary intellectuals, to admit his connection with his own cultural past. He no longer identifies himself with the British upper middle class in which he was reared, yet it is interesting to see how often his sense of fact derives from some ideal of that class, how he finds his way through a problem by means of an unabashed certainty of the worth of some old, simple, belittled virtue. Fairness, decency, and responsibility do not make up a shining or comprehensive morality, but in a disordered world they serve Orwell as an invaluable base of intellectual operations.

Radical in his politics and in his artistic tastes, Orwell is wholly free of the cant of radicalism. His criticism of the old order is cogent, but he is chiefly notable for his flexible and modulated examination of the political and aesthetic ideas that oppose those of the old order. Two years of service in the Spanish Loyalist Army convinced him that he must reject the line of the Communist Party and, presumably, gave him a large portion of his knowledge of the nature of human freedom. He did not become—as Leftist opponents of Communism are so often and so comfortably said to become—“embittered” or “cynical;” his passion for freedom simply took account of yet another of freedom’s enemies, and his intellectual verve was the more stimulated by what he had learned of the ambiguous nature of the newly identified foe, which so perplexingly uses the language and theory of light for ends that are not enlightened. His distinctive work as a radical intellectual became the criticism of liberal and radical thought wherever it deteriorated to shibboleth and dogma. No one knows better than he how willing is the intellectual Left to enter the prison of its own mass mind, nor does anyone believe more directly than he in the practical consequences of thought, or understand more clearly the enormous power, for good or bad, that ideology exerts in an unstable world.

“Nineteen Eighty-Four” is a profound, terrifying, and wholly fascinating book. It is a fantasy of the political future, and, like any such fantasy, serves its author as a magnifying device for an examination of the present. Despite the impression it may give at first, it is not an attack on the Labour Government. The shabby London of the Super-State of the future, the bad food, the dull clothing, the fusty housing, the infinite ennui—all these certainly reflect the English life of today, but they are not meant to represent the outcome of the utopian pretensions of Labourism or of any socialism. Indeed, it is exactly one of the cruel essential points of the book that utopianism is no longer a living issue. For Orwell, the day has gone by when we could afford the luxury of making our flesh creep with the spiritual horrors of a successful hedonistic society; grim years have intervened since Aldous Huxley, in “Brave New World,” rigged out the welfare state of Ivan Karamazov’s Grand Inquisitor in the knickknacks of modern science and amusement, and said what Dostoevski and all the other critics of the utopian ideal had said before—that men might actually gain a life of security, adjustment, and fun, but only at the cost of their spiritual freedom, which is to say, of their humanity. Orwell agrees that the State of the future will establish its power by destroying souls. But he believes that men will be coerced, not cosseted, into soullessness. They will be dehumanized not by sex, massage, and private helicopters but by a marginal life of deprivation, dullness, and fear of pain.

This, in fact, is the very center of Orwell’s vision of the future. In 1984, nationalism as we know it has at last been overcome, and the world is organized into three great political entities. All profess the same philosophy, yet despite their agreement, or because of it, the three Super-States are always at war with each other, two always allied against one, but all seeing to it that the balance of power is kept, by means of sudden, treacherous shifts of alliance. This arrangement is established as if by the understanding of all, for although it is the ultimate aim of each to dominate the world, the immediate aim is the perpetuation of war without victory and without defeat. It has at last been truly understood that war is the health of the State; as an official slogan has it, “War Is Peace.” Perpetual war is the best assurance of perpetual absolute rule. It is also the most efficient method of consuming the production of the factories on which the economy of the State is based. The only alternative method is to distribute the goods among the population. But this has its clear danger. The life of pleasure is inimical to the health of the State. It stimulates the senses and thus encourages the illusion of individuality; it creates personal desires, thus potential personal thought and action.

But the life of pleasure has another, and even more significant, disadvantage in the political future that Orwell projects from his observation of certain developments of political practice in the last two decades. The rulers he envisages are men who, in seizing rule, have grasped the innermost principles of power. All other oligarchs have included some general good in their impulse to rule and have played at being philosopher-kings or priest-kings or scientist-kings, with an announced program of beneficence. The rulers of Orwell’s State know that power in its pure form has for its true end nothing but itself, and they know that the nature of power is defined by the pain it can inflict on others. They know, too, that just as wealth exists only in relation to the poverty of others, so power in its pure aspect exists only in relation to the weakness of others, and that any power of the ruled, even the power to experience happiness, is by that much a diminution of the power of the rulers.

The exposition of the mystique of power is the heart and essence of Orwell’s book. It is implicit throughout the narrative, explicit in excerpts from the remarkable “Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism,” a subversive work by one Emmanuel Goldstein, formerly the most gifted leader of the Party, now the legendary foe of the State. It is brought to a climax in the last section of the novel, in the terrible scenes in which Winston Smith, the sad hero of the story, having lost his hold on the reality decreed by the State, having come to believe that sexuality is a pleasure, that personal loyalty is a good, and that two plus two always and not merely under certain circumstances equals four, is brought back to health by torture and discourse in a hideous parody on psychotherapy and the Platonic dialogues.

Orwell’s theory of power is developed brilliantly, at considerable length. And the social system that it postulates is described with magnificent circumstantiality: the three orders of the population—Inner Party, Outer Party, and proletarians; the complete surveillance of the citizenry by the Thought Police, the only really efficient arm of the government; the total negation of the personal life; the directed emotions of hatred and patriotism; the deified Leader, omnipresent but invisible, wonderfully named Big Brother; the children who spy on their parents; and the total destruction of culture. Orwell is particularly successful in his exposition of the official mode of thought, Doublethink, which gives one “the power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them.” This intellectual safeguard of the State is reinforced by a language, Newspeak, the goal of which is to purge itself of all words in which a free thought might be formulated. The systematic obliteration of the past further protects the citizen from Crimethink, and nothing could be more touching, or more suggestive of what history means to the mind, than the efforts of poor Winston Smith to think about the condition of man without knowledge of what others have thought before him.

By now, it must be clear that “Nineteen Eighty-four” is, in large part, an attack on Soviet Communism. Yet to read it as this and as nothing else would be to misunderstand the book’s aim. The settled and reasoned opposition to Communism that Orwell expresses is not to be minimized, but he is not undertaking to give us the delusive comfort of moral superiority to an antagonist. He does not separate Russia from the general tendency of the world today. He is saying, indeed, something no less comprehensive than this: that Russia, with its idealistic social revolution now developed into a police state, is but the image of the impending future and that the ultimate threat to human freedom may well come from a similar and even more massive development of the social idealism of our democratic culture. To many liberals, this idea will be incomprehensible, or, if it is understood at all, it will be condemned by them as both foolish and dangerous. We have dutifully learned to think that tyranny manifests itself chiefly, even solely, in the defense of private property and that the profit motive is the source of all evil. And certainly Orwell does not deny that property is powerful or that it may be ruthless in self-defense. But he sees that, as the tendency of recent history goes, property is no longer in anything like the strong position it once was, and that will and intellect are playing a greater and greater part in human history. To many, this can look only like a clear gain. We naturally identify ourselves with will and intellect; they are the very stuff of humanity, and we prefer not to think of their exercise in any except an ideal way. But Orwell tells us that the final oligarchical revolution of the future, which, once established, could never be escaped or countered, will be made not by men who have property to defend but by men of will and intellect, by “the new aristocracy . . . of bureaucrats, scientists, trade-union organizers, publicity experts, sociologists, teachers, journalists, and professional politicians.”

These people [says the authoritative Goldstein, in his account of the revolution], whose origins lay in the salaried middle class and the upper grades of the working class, had been shaped and brought together by the barren world of monopoly industry and centralized government. As compared with their opposite numbers in past ages, they were less avaricious, less tempted by luxury, hungrier for pure power, and, above all, more conscious of what they were doing and more intent on crushing opposition. This last difference was cardinal.

The whole effort of the culture of the last hundred years has been directed toward teaching us to understand the economic motive as the irrational road to death, and to seek salvation in the rational and the planned. Orwell marks a turn in thought; he asks us to consider whether the triumph of certain forces of the mind, in their naked pride and excess, may not produce a state of things far worse than any we have ever known. He is not the first to raise the question, but he is the first to raise it on truly liberal or radical grounds, with no intention of abating the demand for a just society, and with an overwhelming intensity and passion. This priority makes his book a momentous one. ♦

New Yorker Favorites

An Oscar-winning filmmaker takes on the Church of Scientology .

Wendy Wasserstein on the baby who arrived too soon .

The young stowaways thrown overboard at sea .

As he rose in politics, Robert Moses discovered that decisions about New York City’s future would not be based on democracy .

The Muslim tamale king of the Old West .

Fiction by Jamaica Kincaid: “ Girl .”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

Books I Read

Curious reads and finds, original new york times review of george orwell’s 1984.

From the 1949 New York Times review of George Orwell’s 1984 (which was written in 1948 and published in 1949):

James Joyce, in the person of Stephen Dedalus, made a now famous distinction between static and kinetic art. Great art is static in its effects; it exists in itself, it demands nothing beyond itself. Kinetic art exists in order to demand; not self-contained, it requires either loathing or desire to achieve its function. The quarrel about the fourth book of ”Gulliver’s Travels” that continues to bubble among scholars — was Swift’s loathing of men so great, so hot, so far beyond the bounds of all propriety and objectivity that in this book he may make us loathe them and indubitably makes us loathe his imagination? — is really a quarrel founded on this distinction. It has always seemed to the present writer that the fourth book of ”Gulliver’s Travels” is a great work of static art; no less, it would seem to him that George Orwell’s new novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four, is a great work of kinetic art. This may mean that its greatness is only immediate, its power for us alone, now, in this generation, this decade, this year, that it is doomed to be the pawn of time. Nevertheless it is probable that no other work of this generation has made us desire freedom more earnestly or loathe tyranny with such fullness. ”Nineteen Eighty-four” appears at first glance to fall into that long-established tradition of satirical fiction, set either in future times or in imagined places or both, that contains works so diverse as ”Gulliver’s Travels” itself, Butler’s ”Erewhon,” and Huxley’s ”Brave New World.” Yet before one has finished reading the nearly bemused first page, it is evident that this is fiction of another order, and presently one makes the distinctly unpleasant discovery that it is not to be satire at all. In the excesses of satire one may take a certain comfort. They provide a distance from the human condition as we meet it in our daily life that preserves our habitual refuge in sloth or blindness or self-righteousness. Mr. Orwell’s earlier book, Animal Farm, is such a work. Its characters are animals, and its content is therefore fabulous, and its horror, shading into comedy, remains in the generalized realm of intellect, from which our feelings need fear no onslaught. But ”Nineteen Eighty-four” is a work of pure horror, and its horror is crushingly immediate. The motives that seem to have caused the difference between these two novels provide an instructive lesson in the operations of the literary imagination. ”Animal Farm” was, for all its ingenuity, a rather mechanical allegory; it was an expression of Mr. Orwell’s moral and intellectual indignation before the concept of totalitarianism as localized in Russia. It was also bare and somewhat cold and, without being really very funny, undid its potential gravity and the very real gravity of its subject, through its comic devices. ”Nineteen Eighty-four” is likewise an expression of Mr. Orwell’s moral and intellectual indignation before the concept of totalitarianism, but it is not only that. It is also — and this is no doubt the hurdle over which many loyal liberals will stumble — it is also an expression of Mr. Orwell’s irritation at many facets of British socialism, and most particularly, trivial as this may seem, at the drab gray pall that life in Britain today has drawn across the civilized amenities of life before the war.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

1984 Book Summary – George Orwell

06 Mar 1984 Book Summary – George Orwell

This review aims to dissect and analyze “1984” in its entirety, offering insights into its thematic richness, narrative style, and Orwell’s vision of a world subsumed by tyranny and propaganda.

Suggested Reading Age “1984” is best suited for readers aged 15 and above due to its complex themes and some mature content.

Thesis Statement Orwell’s “1984” is not just a novel but a warning, an intricate exploration of the dangers of political extremism and the loss of personal freedom.

Short Synopsis of 1984

“1984” by George Orwell is a dystopian novel that delves into the horrors of a totalitarian society under constant surveillance. Set in the superstate of Oceania, it follows Winston Smith, a member of the Outer Party, working at the Ministry of Truth. The Party, led by the elusive Big Brother, exercises absolute control over all aspects of life, including history, language, and even thought. Winston, feeling suppressed and rebellious, begins a forbidden love affair with Julia, a co-worker, as an act of defiance against the Party’s oppressive regime. However, their rebellion is short-lived as they are caught and subjected to brutal psychological manipulation and reconditioning by the Party. The novel explores themes of totalitarianism, propaganda, and the crushing of individuality, culminating in Winston’s tragic acceptance of the Party’s dominance. “1984” remains a powerful warning about the dangers of unchecked government power and the erosion of fundamental human rights.

1984 Detailed Book Summary

“1984” is set in a dystopian future where the world is divided into three superstates constantly at war: Oceania, Eurasia, and Eastasia. The story unfolds in Airstrip One (formerly Great Britain), a province of the totalitarian superstate of Oceania, which is under the control of the Party led by the figurehead Big Brother.

Winston Smith : The novel’s protagonist, Winston Smith, is a 39-year-old man who works at the Ministry of Truth, where his job is to alter historical records, thus aligning the past with the ever-changing party line of the present. Winston lives in a world of perpetual war, omnipresent government surveillance, and public manipulation.

Early Acts of Rebellion : Despite outwardly conforming, Winston harbors deep-seated hatred for the Party. He begins to express his subversive thoughts by starting a diary, an act punishable by death if discovered by the Thought Police. Through his writing, Winston explores his fragmented memories of the past, pondering the Party’s control over reality and truth.

Julia and the Love Affair : Winston becomes involved with Julia, a younger Party member who secretly shares his loathing of the regime. Their love affair is initially an act of rebellion. They meet in secret and dream of a life free from the Party’s control. Their relationship represents a profound act of personal freedom and rebellion against the regime.

O’Brien and the Brotherhood : Winston and Julia are drawn to O’Brien, an Inner Party member whom Winston believes to be secretly a member of a clandestine opposition group known as the Brotherhood, led by the legendary Emmanuel Goldstein. O’Brien inducts them into the Brotherhood, providing a copy of Goldstein’s subversive book which outlines the ideology of freedom and rebellion against the Party.

Capture and Betrayal : The illusion of rebellion is shattered when Winston and Julia are arrested in their sanctuary. It is revealed that their rebellion was a trap orchestrated by the Thought Police, with O’Brien as one of its agents.

Winston’s Imprisonment and Torture : In the Ministry of Love, Winston is separated from Julia and subjected to psychological and physical torture. The aim is to force him to confess his crimes against the Party and to break his spirit completely. Winston resists as much as he can, holding onto his inner sense of truth and loyalty to Julia.

Room 101 : The climax of Winston’s torture occurs in Room 101, where he is confronted with his worst fear – rats. In a moment of utter despair and terror, Winston betrays Julia, begging that she be tortured in his place. This ultimate betrayal represents the complete destruction of Winston’s resistance.

Re-education and Acceptance : Following his experience in Room 101, Winston undergoes a process of “re-education” where he learns to accept the Party’s version of reality and to love Big Brother. He is released back into society, a hollow, obedient citizen.

Final Encounter with Julia : After his release, Winston encounters Julia one more time. Both admit to betraying each other and realize that their feelings for each other have been eradicated. The Party’s victory is complete, with any trace of personal loyalty or love eradicated.

Winston’s Final Submission : The novel ends with Winston completely accepting the Party’s doctrine and viewing his execution as a victory – he has conformed entirely to the Party’s ideals. His final thoughts are of unquestioning love and loyalty to Big Brother, signifying the total and absolute triumph of the Party’s control over the individual mind and spirit.

Orwell’s “1984” is a powerful and chilling portrayal of a totalitarian world where freedom of thought is suppressed under the guise of state security, and the truth is what the Party deems it to be. It remains a poignant and cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked political power and the erosion of individual liberties.

The novel delves into Winston’s life as he begins a forbidden love affair with Julia and gets involved with what appears to be an underground resistance movement. However, this rebellion is short-lived as they are betrayed and subjected to the Party’s ruthless tactics of psychological manipulation and physical torture, leading to Winston’s ultimate surrender to the Party’s orthodoxy.

Character Descriptions:

- Winston Smith: Age: Approximately 39 years old. Occupation: Works at the Ministry of Truth, where he alters historical records to align with the Party’s current propaganda. Personality Traits: Initially, Winston exhibits intellectual curiosity, internal rebellion, and skepticism towards the Party’s doctrine. He is contemplative, introspective, and carries a sense of melancholy. Character Arc: Winston evolves from a quiet dissident to an active rebel, seeking truth and love in a society devoid of both. His relationship with Julia deepens his rebellious spirit. However, after his capture and torture, he becomes a defeated, loyal follower of Big Brother, losing his individuality and spirit of dissent.

- Julia: Age: In her mid-20s. Occupation: Works on the novel-writing machines in the Fiction Department at the Ministry of Truth. Personality Traits: Julia is practical, sensual, and outwardly conforms to Party norms while secretly despising its control. She is bold and pragmatic in her approach to rebellion, focusing more on personal freedom than on broader political change. Character Arc: Julia engages in an affair with Winston as a form of personal rebellion. She is less interested in the theoretical aspects of their rebellion and more in the personal joy it brings. After their capture, like Winston, she is broken by the Party, ultimately betraying Winston and accepting Party doctrine.

- O’Brien: Occupation: A member of the Inner Party. Personality Traits: O’Brien is intelligent, articulate, and initially seems sympathetic to Winston’s skepticism of the Party. He exudes a certain charm and civility. Character Arc: O’Brien reveals himself as a loyalist to the Party and plays a key role in Winston’s torture and re-education. He embodies the Party’s manipulative and brutal nature. His interactions with Winston highlight the Party’s deep understanding of human psychology and its use in breaking down resistance.

- Big Brother: Role: The symbolic leader and face of the Party. Description: Big Brother is more a symbol than a character, representing the omnipresent, all-seeing Party. He is depicted as a mustachioed man appearing on posters and telescreens with the slogan “Big Brother is watching you.” His actual existence is ambiguous, but his presence is a powerful tool in the Party’s arsenal for instilling loyalty and fear.

- Mr. Charrington: Occupation: Owner of an antique shop in the Proles district. Personality Traits: Initially appears as a kindly, old shopkeeper interested in history and artifacts from the past. Character Arc: Revealed to be a member of the Thought Police, his character highlights the Party’s extensive surveillance network and the deception employed to trap dissidents like Winston and Julia.

In-depth Analysis

- Strengths : “1984” excels in its haunting portrayal of a society stripped of freedom and individuality. Orwell masterfully uses a bleak and concise prose style to convey the oppressive atmosphere of Oceania. The intricate depiction of the Party’s manipulation of truth and history remains particularly chilling and relevant.

- Weaknesses : For some, the despairing tone and the inevitability of Winston’s defeat may come across as overly pessimistic, offering little in the way of hope or resistance against such a powerful system.

- Uniqueness : The novel’s concept of “Newspeak,” the language designed to limit free thought, and “doublethink,” the ability to accept two contradictory beliefs, are unique contributions to the lexicon of political and philosophical thought.

- Literary Devices : Orwell’s use of symbolism, foreshadowing, and irony are noteworthy. For instance, the figure of Big Brother symbolizes the impersonal and omnipresent power of the Party.

- Relation to Broader Issues : The book’s exploration of surveillance, truth manipulation, and state control has clear parallels with modern concerns about privacy, fake news, and authoritarianism, making it perennially relevant.

- Potential Audiences : “1984” is a must-read for enthusiasts of political and dystopian fiction. It is also highly valuable for those interested in political theory, sociology, and history.

- Comparisons : “1984” often draws comparisons with Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World,” another dystopian masterpiece, though Huxley’s work envisages a different form of control through hedonism and consumerism.

- Final Recommendations : This novel is an essential read for understanding the extremes of political control and the fragility of human rights. It’s a cautionary tale that remains profoundly relevant in today’s world.

Thematic Analysis and Stylistic Elements

The themes of “1984” are deeply interwoven and reflect Orwell’s concerns about totalitarianism. Themes include the corruption of language as a tool for oppressive power (“Newspeak”), the erosion of truth and reality in politics, and the loss of individuality. Stylistically, Orwell’s direct and terse prose serves as a mirror to the stark world he describes, emphasizing the theme of decay and dehumanization.

Comparisons to Other Works

Orwell’s “Animal Farm,” a satirical allegory of Soviet totalitarianism, shares similar themes with “1984,” but differs in its approach and style, using a fable-like structure. “1984” is more direct and visceral in its depiction of a dystopian society.

Chapter by Chapter Summary of 1984

- Chapter 1 : Winston Smith, a low-ranking member of the ruling Party in Oceania, returns to his flat in Victory Mansions. He begins to write a diary, an act prohibited by the Party.

- Chapter 2 : Winston recalls recent Two Minutes Hate sessions and reflects on the Party’s control over Oceania’s history and residents. He hides his diary.

- Chapter 3 : Winston dreams of his mother and sister, and then of O’Brien, an Inner Party member he believes may secretly oppose the Party. The chapter ends with Winston’s alarm waking him for the Physical Jerks, a mandatory morning exercise.

- Chapter 4 : Winston goes to his job at the Ministry of Truth, where he alters historical records to fit the Party’s current version of events.

- Chapter 5 : During lunch, Winston discusses the principles of Newspeak with a co-worker, Syme. He observes the Parsons family and considers the effectiveness of Party propaganda on children.

- Chapter 6 : Winston thinks about his wife, Katharine, and their cold, lifeless marriage, reflecting on the Party’s repressive attitude towards sex and love.

- Chapter 7 : Winston writes in his diary about the hopelessness of rebellion and the likelihood that he will be caught by the Thought Police. He ponders whether life was better before the Party took over.

- Chapter 8 : Winston visits a prole neighborhood. He enters an antique shop and buys a coral paperweight. He talks with the shop owner, Mr. Charrington, and learns about life before the Party’s rule.

- Chapter 9 : Oceania switches enemies from Eurasia to Eastasia. Winston receives Goldstein’s book and begins reading it.

- Chapter 10 : Winston wakes up from a dream shouting, “Shakespeare!” He and Julia plan to rent the room above Mr. Charrington’s shop for their clandestine meetings.

- Chapter 11 : In the rented room, Winston and Julia continue their secret meetings, but Winston feels the futility of their rebellion.

- Chapter 12 : Winston reads to Julia from Goldstein’s book, explaining the social structure of Oceania and the perpetual war.

- Chapter 13 : Winston continues reading the book, discussing the principles of war and the Party’s manipulation of the populace.

- Chapter 14 : Winston and Julia are discovered by the Thought Police in their rented room. Mr. Charrington reveals himself as a member of the Thought Police.

- Chapter 15 : Winston is detained in the Ministry of Love. He encounters other prisoners and realizes the Party’s extensive power.

- Chapter 16 : O’Brien tortures Winston, gradually breaking his spirit. He admits to various crimes against the Party, both real and imagined.

- Chapter 17 : O’Brien continues Winston’s re-education, revealing more about the Party’s ideology and the concept of doublethink.

- Chapter 18 : Winston is taken to Room 101, where he is confronted with his worst fear—rats. He betrays Julia, proving his complete submission to the Party.

- Chapter 19 : Winston is released and spends his time at the Chestnut Tree Café. He is a changed man, devoid of rebellious thoughts.

- Chapter 20 : Winston meets Julia again, but their feelings for each other have vanished. They both admit to betraying each other.

- Chapter 21 : The novel concludes with Winston, completely broken, confessing his love for Big Brother, accepting Party orthodoxy fully.

Potential Test Questions and Answers

- Answer: It signifies the omnipresent surveillance of the Party and the constant monitoring of individuals’ actions and thoughts, instilling fear and obedience.

- Answer: “Newspeak” is designed to diminish the range of thought by reducing the complexity and nuance of language, making rebellion against the Party’s ideology linguistically impossible.

- Answer: The Thought Police serve to detect and punish “thoughtcrime,” any personal and political thoughts unapproved by the Party, thereby enforcing ideological purity and suppressing dissent.

- “George Orwell: The Prophet of the Dystopian Future,” The Literary Encyclopedia.

- “Totalitarianism and Language: Orwell’s 1984,” Journal of Modern Literature.

Awards and Recognition

“1984” has received critical acclaim since its publication and has been listed in various “best novels” lists, including the “100 Best Novels of the 20th Century” by the Modern Library.

Bibliographic Information

- Publisher: Signet Book

- Publish Date: July 01, 1950

- Type: Mass Market Paperbound

- ISBN/EAN/UPC: 9780451524935

Summaries of Other Reviews

- The Guardian: Highlights the novel’s prophetic nature and its enduring relevance in the digital age.

- The New Yorker: Discusses the novel’s profound impact on language and political thought.

Notable Quotes from 1984

- This paradoxical slogan of the Party encapsulates the use of doublethink, a process of indoctrination that requires citizens to accept contradictory beliefs, fostering a disconnection from reality and thus ensuring loyalty to the Party.

- This omnipresent warning is emblematic of the government’s pervasive surveillance in Oceania. It instills fear and obedience in the populace, reminding them of the Party’s constant monitoring of their actions and thoughts.

- This reflects the Party’s manipulation of truth and its control over what is considered knowledge. It reveals the theme of reality control and the dangers of a society where objective truth is subjugated to political agenda.

- This quote grimly summarizes the Party’s vision for the future: a world where the individual is utterly powerless, and the state exerts total control, both physically and psychologically.

- This highlights the Party’s manipulation of history to maintain its grip on power. It underscores a central theme in “1984” — the control of information and history as a means of controlling the populace.

- This defines the concept of doublethink, a crucial method by which the Party breaks down individual understanding of truth and reality, ensuring unconditional loyalty.

- This statement underscores the significance of objective truth and the resistance against the Party’s distortion of reality. It signifies the importance of individual thought and rationality as a form of rebellion.

- This conundrum highlights the challenge faced by those living under totalitarian rule, where the lack of consciousness about their oppression prevents rebellion, yet without rebelling, they cannot become fully aware of their subjugation.

Spoilers/How Does It End?

Warning: This section contains major spoilers about the ending of “1984” by George Orwell.

“1984” culminates in a harrowing and profoundly impactful conclusion that starkly illuminates the depths of the Party’s control over the individual.

- Winston’s Transformation and Betrayal : After Winston Smith and Julia are captured by the Thought Police, they are separated and taken to the Ministry of Love for interrogation and re-education. The person responsible for Winston’s capture and subsequent torture is O’Brien, whom Winston had previously believed to be a fellow dissident. This betrayal is a crucial turning point in the novel, as it shatters Winston’s last hope for an organized rebellion against the Party.

- The Room 101 Experience : Winston endures severe physical and psychological torture under O’Brien’s supervision. The climax of his torture occurs in Room 101, where prisoners are confronted with their worst fears. For Winston, this is a face cage filled with ravenous rats. Faced with this terror, Winston betrays Julia by begging for her to be tortured in his place. This moment is pivotal as it represents the complete breakdown of Winston’s resistance and the success of the Party in breaking his spirit.

- Winston’s Reintegration into Society : After his release, Winston is a shell of his former self. He has been thoroughly brainwashed and now genuinely loves Big Brother. He spends his time at the Chestnut Tree Café, where other broken rebels gather. One day, he meets Julia again. They acknowledge that they betrayed each other and that their feelings for each other have been eradicated. This meeting underscores the Party’s complete victory in destroying individual loyalty and emotion, replacing them with loyalty to the Party alone.

- The Final Act of Submission : The novel ends with Winston’s final submission to the Party’s ideology. He has a vision of being executed but realizes that he has won the victory over himself – he loves Big Brother. This chilling conclusion signifies the total and irrevocable triumph of the Party over the individual. Winston’s love for Big Brother is a symbol of the Party’s successful eradication of independent thought and the total reprogramming of the human psyche.

Orwell’s ending is stark and dystopian, offering no hope of rebellion or change. It serves as a powerful warning about the dangers of totalitarianism and the fragility of human rights and freedom under such regimes. The ending is deliberately unsettling, leaving the reader to contemplate the consequences of unchecked political power and the importance of safeguarding democratic values and individual liberties.

Share this:

39 true-not-alternative facts about George Orwell's 1984

Social Sharing

George Orwell's 1984 was a critical and commercial hit when it was first published 70 years ago. Its depiction of a corrupt society — where a person's every move is monitored and the news is rewritten to suit those in power — remains terrifyingly relevant to the world today.

British author and journalist Dorian Lynskey explores this influential text, and the man who wrote it, in his new book The Ministry of Truth . He will be interviewed by Eleanor Wachtel on CBC Radio's Writers & Company on Sunday (Sept. 8) as the new season premieres.

- Why George Orwell's 1984 still matters, 70 years since publication

Below, we've gathered some interesting facts about 1984 from Lynskey's book and few other online sources.

1. George Orwell was born Eric Arthur Blair on June 25, 1903 in India.

2. At Eton College — a boys' private school Orwell attended on a full scholarship from 1917-1921 — Orwell was taught briefly by Aldous Huxley. About a decade later, Huxley published the classic sci-fi novel Brave New World .

3. Orwell's first published work was a short story in Eton College's magazine called A Peep into the Future , inspired by the fiction of H. G. Wells.

4. Orwell didn't begin writing seriously until he was nearly 30.

5. The pseudonym George Orwell appeared when he published his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London , in 1934.

6. The name Orwell was taken from the River Orwell in Suffolk.

7. Kenneth Miles, P.S. Burton and H. Lewis Allways were other pen names Orwell considered adopting.

8. Orwell never officially changed his name. His gravestone in Oxfordshire, England has the words, "Here Lies Eric Arthur Blair."

9. From 1941-1943, with Britain at war, Orwell worked for BBC Radio as an "Empire Talks Assistant," part of the Indian Section of the BBC's Eastern Service. Apparently, Orwell's voice was so unpleasant to listen to, no recordings exist today.

10. Orwell's supervisor at the BBC was Guy Burgess, who was part of the Soviet spy ring known as the Cambridge Five.

11. During the Second World War, Orwell and his wife Eileen were almost killed in the final hours of The Blitz.

12. Orwell was the first person to use the term "Cold War" — initially in the early months of the Second World War, and again in 1945, in his essay, You and the Atomic Bomb .

- 5 things George Orwell understood

13. Animal Farm, published in 1945, was a break out book for Orwell, who was not well-known internationally at the time. Animal Farm was a sensation in the United States and spent eight weeks on the New York Times bestseller list.

14. Animal Farm was initially rejected by many publishers. Orwell considered self-publishing it, until Secker & Warburg stepped in.

15. Orwell's life was transformed by the unexpected success of Animal Farm . The financial freedom allowed him to write 1984 .

16. Orwell wrote the manuscript for 1984 over a span of about 18 months — June 1947 to December 1948 — on the island of Jura, in the Scottish Hebrides, between periods of hospitalization for tuberculosis.

17. When a typist could not be found to execute the final draft, Orwell typed it himself at a rate of about 4,000 words per day, seven days a week. Friends and relatives have suggested that he jeopardized his health for the sake of completing the novel.

18. The title is often thought to be an inversion of 1948 (the year Orwell finished writing the manuscript), but there is no evidence to support this. The outline for the novel features other dates, including 1980 and 1982. In the outline, the title of the novel was The Last Man in Europe .

Doublethink and Big Brother: George Orwell's son talks about 68 years of 1984

19. When George Orwell's novel 1984 was published in June 1949, the book was an immediate success. It sold more than a quarter of a million copies in the U.K. and the U.S. in the first six months. In the U.S., the novel remained on the the New York Times bestseller list for 20 weeks and, in its first five years, went on to sell 170,000 in hardback, 190,000 through Book-of-the-Month Club, 596,000 in a Reader's Digest Condensed Books edition and 1.2 million as a New American Library paperback.

20. The first film version of 1984 was released in 1956, made with funding from the U.S. government (United States Information Agency). It was intended to be "the most devastating anti-Communist film of all time." It was directed by Michael Anderson with an adapted screenplay by William Templeton. They shot two different endings — one for the American audience that was more loyal to the novel and an alternative ending for the British audience.

21. But the very first adaptation of 1984 was the 1949 radio drama produced by NBC University Theater , starring David Niven. It aired on August 27, 1949, just months after the publication of the novel (June 8, 1949) and before the death of George Orwell (Jan. 21, 1950).

22. In 1954, the BBC produced a teleplay adaptation of 1984 , starring Peter Cushing, which was watched by more than 7 million people. Hundreds complained to the BBC about violence and sexuality.

23. One of the hallmarks of 1984 is its wordplay — Orwell's inventive neologisms that have passed into everyday use. They started appearing in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1950, beginning with "Newspeak," and followed by "Big Brother" and "doublethink" in 1953 and "Thoughtcrime and "unperson" in 1954.

Orwell's 1984 eerily parallels reality in the age of Trump, says author

24. In the early 1970s, Bowie planned to produce a rock musical adaptation of 1984 . However Sonia Orwell (Bromnell), Orwell's widow and co-executor of his estate, refused permission for the rock musical.

25. Bowie ended up turning his eighth studio album, initially titled We Are the Dead , into a concept album to make use of the songs he'd already written for the musical. Diamond Dogs was released in 1974 and includes the songs 1984 , We Are the Dead , Big Brother and Rebel Rebel .

26. But Bowie is far from the only musician to take inspiration from 1984 . An entire musical subgenre known as "Orwave" has formed around the novel and includes artists like John Lennon, Stevie Wonder, The Clash, Radiohead and Rage Against the Machine.

27. The term "Orwellian" was coined by the American novelist and critic Mary McCarthy in a 1950 essay about Flair magazine: "[ Flair ] is a leap into the Orwellian future, a magazine without contest of point of view beyond its proclamation of itself."

28. In the year 1984, Orwell's son, Richard Blair, was 39 years old — the same age as Winston Smith, the protagonist of 1984 .

29. There was a surge in sales for 1984 between 1983 and 1984 . It sold 4 million copies in 62 languages.

30. Apple's big-budget TV ad for the very first MacIntosh computer was directed by Ridley Scott and aired during the 1984 Super Bowl to 96 million Americans. The concept was based on 1984 , starring discus thrower Anya Major and David Graham as Big Brother. It immediately became a news story, and was the first Super Bowl ad to get people talking about a commercial instead of the game.

31. American Democrats and Republicans both cited 1984 in their fundraising letter during the 1984 presidential election campaign. The leaders of Britain's three main political parties all mentioned the book in their New Year's Eve messages.

32. A film adaptation of 1984 was released in 1984. Directed by Michael Radford, the film stars John Hurt as Winston Smith, Suzanna Hamilton as Julia and Richard Burton as the character O'Brien. Richard Burton came out of retirement to play the role; it was his final performance before his death of a stroke in August 1984. Apparently, Burton found the lines of O'Brien — the authoritative Party member who tortures Winston — to be "unnervingly seductive…"

33. Orwell's 1984 was influenced by the Russian dissident and author Yevgeny Zamyatin. Critics have drawn parallels between 1984 and Zamyatin's novel We written in the early 1920s.

34. In the spring of 1984, Margaret Atwood started writing The Handmaid's Tale in West Berlin. As a teenager, she was interested in dystopias and WWII, and identified with Winston Smith, the central character in 1984 . The appendix in The Handmaid's Tale is a reference to 1984 , as is Offred's diary.

- We're all reading 1984 wrong, according to Margaret Atwood

35. During the 2016 U.S. election campaign, a meme was shared on social media that attributed a quotation to Orwell: "The people will believe what the media tells them they believe — George Orwell." Orwell never wrote or said these words. The quotation was fabricated by the Internet Research Agency, a Russian media company.

36. When U.S. President Donald Trump's adviser Kellyanne Conway first used the phrase "alternative facts" on January 22, 2017, U.S. sales of 1984 increased by 9,500 per cent.

37. When 1984 was first published, it was compared to an earthquake, a bundle of dynamite and the label on a bottle of poison.

38. A few prominent reviews include E. M. Forster, who said it was "too terrible a novel to be read straight through," Arthur Koestler, who called it "a glorious book," Aldous Huxley who described it as "profoundly important," Margaret Storm Jameson, who referred to it as "the novel which should stand for our age," and, finally, Lawrence Durrell, who observed that "reading it in a Communist country is really an experience because one can see it all around one."

39. Despite the positive reviews, Orwell felt 1984 was largely misinterpreted by readers and critics. He released two statements about the novel's message from his hospital bed, making clear that it was not an attack on socialism or on the British Labour Party (which he supported), but a warning that "totalitarianism, if not fought against, could triumph anywhere."

Related Stories

- q We're all reading 1984 wrong, according to Margaret Atwood

- As It Happens Doublethink and Big Brother: George Orwell's son talks about 68 years of 1984

- ideas The Orwell Tapes: recordings from his earliest days to his final moments

- In 1984, Stephen Wadhams made a radio documentary about George Orwell. Now it's a book

- DOG-EARED READS Tom Rachman on the lasting relevance of A Collection of Essays by George Orwell

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

News, Notes, Talk

Read the first reviews of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four .

Perhaps one did not want to be loved so much as to be understood.

George Orwell’s dystopian masterwork, Nineteen Eighty-Four , was first published seventy-four years ago today.

Set in a totalitarian London in an imagined future where all citizens are subject to constant government surveillance and historical reeducation, Nineteen Eighty-Four tells the story of Winston Smith, a mid-level everyman at the Ministry of Truth who dreams of rebellion and who falls in love with a fellow aspiring revolutionary named Julia.

Things… do not turn out well for the pair.

Here’s a look back at some of the novel’s very first reviews.

“Nineteen Eighty-Four goes through the reader like an east wind, cracking the skin, opening the sores; hope has died in Mr Orwell’s wintry mind, and only pain is known. I do not think I have ever read a novel more frightening and depressing; and yet, such are the originality, the suspense, the speed of writing and withering indignation that it is impossible to put down. The faults of Orwell as a writer—monotony, nagging, the lonely schoolboy shambling down the one dispiriting track—are transformed now he rises to a large subject.

“These wars are mainly fought far from the great cities and their objects are to use up the excessive productiveness of the machine, and yet to get control of rare raw materials or cheap native labour. It also enables the new governing class, who are modelled on the Stalinists, to keep down the standard of living and nullify the intelligence of the masses whom they no longer pretend to have liberated. The collective oligarchy can operate securely only on a war footing. It is with this moral corruption of absolute power that Mr Orwell’s novel is concerned.

“In the homes of Party members a tele-screen is fitted, from which canned propaganda continually pours, and on which the pictures of Big Brother, the leader…Also by this device the Thought Police, on endless watch for Thought Crime, can observe the people night and day. What precisely Thought Crime is no one knows; but in general it is the tendency to conceive a private life secret from the State. A frown, a smile, a sigh may betray the citizen, who has forgotten, for the moment, the art of ‘reality control’ or, in Newspeak, the official language, ‘doublethink.’

“The duty of the satirist is to go one worse than reality; and it might be objected that Mr Orwell is too literal, that he is too oppressed by what he sees, to exceed it. In one or two incidents where he does exceed, notably in the torture scenes, he is merely melodramatic: he introduces those rather grotesque machines which used to appear in terror stories for boys. But mental terrorism is his real subject.

“For Mr Orwell, the most honest writer alive, hypocrisy is too dreadful for laughter: it feeds his despair.

Though the indignation of Nineteen Eighty-Four is singeing, the book does suffer from a division of purpose. Is it an account of present hysteria, is it a satire on propaganda, or a world that sees itself entirely in inhuman terms? Is Mr Orwell saying, not that there is no hope, but that there is no hope for man in the political conception of man?”

– V.S. Pritchett, The New Statesman , June 18, 1949

“Though all ‘thinking people,’ as they are still sometimes called, must by now have more than a vague idea of the dangers which mankind runs from modern techniques, George Orwell , like Aldous Huxley, feels that the more precise we are in our apprehensions the better. Huxley’s Ape and Essence was in the main a warning of the biological evils the split atom may have in store for us; Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four speaks of the psychological breaking-in process to which an up-to-date dictatorship can subject non-cooperators.

The story is brilliantly constructed and told. Winston Smith, of the Party (but not the Inner Party) kicks against the pricks, with what results we shall leave readers to find out for themselves. It has become a dreadful occasion of anguish to-day conjecturing how much torture even a saint can put up with if the end is certainly not to be a spectacular martyrdom—but ‘vaporisation.’ The less you are familiar with the idea of the agent provocateur as an instrument of oppression and rule the more you will shudder at the wiles used by the Ministry of Love in Mr. Orwell’s London of 1984, ‘chief city of Airstrip One, Oceana.’ An example of the way things are managed: Emmanuel Goldstein, the proscribed Opposition leader, is a fiction artfully sustained by the authorities to lure deviationists into giving themselves away.

It is an instructive book; there is a good deal of What Every Young Person Ought to Know—not in 1984, but 1949. Mr Orwell’s analysis of the lust for power is one of the less satisfactory contributions to our enlightenment, and he also leaves us in doubt as to how much he means by poor Smith’s ‘faith’ in the people (or ‘proles’). Smith is rather let down by the 1984 Common Man, and yet there is some insinuation that common humanity remains to be extinguished.

– The Guardian , June 10, 1949

“In Britain 1984 A.D., no one would have suspected that Winston and Julia were capable of crimethink (dangerous thoughts) or a secret desire for ownlife (individualism). After all, Party-Member Winston Smith was one of the Ministry of Truth’s most trusted forgers; he had always flung himself heart & soul into the falsification of government statistics. And Party-Member Julia was outwardly so goodthinkful (naturally orthodox) that, after a brilliant girlhood in the Spies, she became active in the Junior Anti-Sex League and was snapped up by Pornosec, a subsection of the government Fiction Department that ground out happy-making pornography for the masses. In short, the grim, grey London Times could not have been referring to Winston and Julia when it snorted contemptuously: ‘Old-thinkers unbellyfeel Ingsoc,’ i.e., ‘Those whose ideas were formed before the Revolution cannot have a full emotional understanding of the principles of English Socialism.’

How Winston and Julia rebelled, fell in love and paid the penalty in the terroristic world of tomorrow is the thread on which Britain’s George Orwell has spun his latest and finest work of fiction. In Animal Farm, Orwell parodied the Communist system in terms of barnyard satire; but in 1984 … there is not a smile or a jest that does not add bitterness to Orwell’s utterly depressing vision of what the world may be in 35 years’ time.”

“Most novels about an imaginary world have as their central character, or interpreter, a man who somehow strays out of the author’s own time and finds himself in a world he never made. But Orwell, like Aldous Huxley in Brave New World , builds his nightmare of tomorrow on foundations that are firmly laid today. He needs to contemporary spokesman to explain and interpret—for the simple reason that any reader in 1949 can uneasily see his own shattered features in Winston Smith, can scent in the world of 1984 a stench that is already familiar.”

– TIME, June 20, 1949

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)