Module 13: Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence

Case studies: disorders of childhood and adolescence, learning objectives.

- Identify disorders of childhood and adolescence in case studies

Case Study: Jake

Jake was born at full term and was described as a quiet baby. In the first three months of his life, his mother became worried as he was unresponsive to cuddles and hugs. He also never cried. He has no friends and, on occasions, he has been victimized by bullying at school and in the community. His father is 44 years old and describes having had a difficult childhood; he is characterized by the family as indifferent to the children’s problems and verbally violent towards his wife and son, but less so to his daughters. The mother is 41 years old, and describes herself as having a close relationship with her children and mentioned that she usually covers up for Jake’s difficulties and makes excuses for his violent outbursts. [1]

During his stay (for two and a half months) in the inpatient unit, Jake underwent psychiatric and pediatric assessments plus occupational therapy. He took part in the unit’s psycho-educational activities and was started on risperidone, two mg daily. Risperidone was preferred over an anti-ADHD agent because his behavioral problems prevailed and thus were the main target of treatment. In addition, his behavioral problems had undoubtedly influenced his functionality and mainly his relations with parents, siblings, peers, teachers, and others. Risperidone was also preferred over other atypical antipsychotics for its safe profile and fewer side effects. Family meetings were held regularly, and parental and family support along with psycho-education were the main goals. Jake was aided in recognizing his own emotions and conveying them to others as well as in learning how to recognize the emotions of others and to become aware of the consequences of his actions. Improvement was made in rule setting and boundary adherence. Since his discharge, he received regular psychiatric follow-up and continues with the medication and the occupational therapy. Supportive and advisory work is done with the parents. Marked improvement has been noticed regarding his social behavior and behavior during activity as described by all concerned. Occasional anger outbursts of smaller intensity and frequency have been reported, but seem more manageable by the child with the support of his mother and teachers.

In the case presented here, the history of abuse by the parents, the disrupted family relations, the bullying by his peers, the educational difficulties, and the poor SES could be identified as additional risk factors relating to a bad prognosis. Good prognostic factors would include the ending of the abuse after intervention, the child’s encouragement and support from parents and teachers, and the improvement of parental relations as a result of parent training and family support by mental health professionals. Taken together, it appears that also in the case of psychiatric patients presenting with complex genetic aberrations and additional psychosocial problems, traditional psychiatric and psychological approaches can lead to a decrease of symptoms and improved functioning.

Case Study: Kelli

Kelli may benefit from a course of comprehensive behavioral intervention for her tics in addition to psychotherapy to treat any comorbid depression she experiences from isolation and bullying at school. Psychoeducation and approaches to reduce stigma will also likely be very helpful for both her and her family, as well as bringing awareness to her school and those involved in her education.

- Kolaitis, G., Bouwkamp, C.G., Papakonstantinou, A. et al. A boy with conduct disorder (CD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), borderline intellectual disability, and 47,XXY syndrome in combination with a 7q11.23 duplication, 11p15.5 deletion, and 20q13.33 deletion. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 10, 33 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-016-0121-8 ↵

- Case Study: Childhood and Adolescence. Authored by : Chrissy Hicks for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- A boy with conduct disorder (CD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), borderline intellectual disability.... Authored by : Gerasimos Kolaitis, Christian G. Bouwkamp, Alexia Papakonstantinou, Ioanna Otheiti, Maria Belivanaki, Styliani Haritaki, Terpsihori Korpa, Zinovia Albani, Elena Terzioglou, Polyxeni Apostola, Aggeliki Skamnaki, Athena Xaidara, Konstantina Kosma, Sophia Kitsiou-Tzeli, Maria Tzetis . Provided by : Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. Located at : https://capmh.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13034-016-0121-8 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Angry boy. Located at : https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-jojfk . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Frustrated girl. Located at : https://www.pickpik.com/book-bored-college-education-female-girl-1717 . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Pre-School and a Child With Behavioural Issues: A Case Study

As an affiliate, we earn from qualifying purchases including Amazon. We get commissions for purchases made through links in this post.

For many children, starting their local pre-school group is the first step towards attending primary school. Pre-schools offer a fun and safe environment for children, where they can start to get used to looking after themselves, gaining independence and learn to socialise.

Table of Contents

Learning Through Play

The emphasis on pre-school education has always been learning through play, and children are encouraged to display positive social behaviour and find ways to interact with one another. The ratio of staff to children is quite high and groups tend to hold small sessions in the morning or afternoon and occasionally all day. There are breaks for drinks, snacks and lunch and many pre-schools will also have a quiet time where children can relax on floor cushions and have a rest.

Once Rachel had the chance to sit down with the pre-school staff and come up with a plan of action, she felt confident that William would eventually be fine. She said: “The staff were great and very supportive. I hated leaving William when he was so upset and sad, but the staff reassured me that this was very normal and that in time he would adjust. They also suggested that William was assessed for special needs, and after some time and lots of meetings we did actually discover that he is on the spectrum of Autism as well. This is obviously a big issue, but again we received massive support from everyone and now he is thriving at primary school. If it hadn’t been for pre-school getting involved, William may well have slipped through the net.”

Coping Strategies

Rachel recognised that William had problems with being left, and this was also evident at friend’s houses, parties and other events and activities. With the support of pre-school, she found a way for William to take part in some activities where she could also be involved. To help William deal with his insecurity, Rachel also volunteered to help out at pre-school a couple of times a week. This way she could keep an eye on him.

Rachel added: “It’s not always the best idea – spending all that time with a child when they are being encouraged to become independent can be a bit negative – but for William it worked really well. In fact, when I was at pre-school he pretty much ignored me, but knowing I was there made a big difference and he was much happier, I think we were keeping an eye on each other!”

Support From Teachers

Leave a reply cancel reply, children and self-discipline, managing expectations and behaviour at christmas, related posts, why are puppets creepy a comprehensive look at the issue, living with an obsessive compulsive child: case study.

Kids Behaviour spoke to a mother whose child suffers from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Wishing to protect her identity, here is what she told us: Living with an obsessive compulsive child…

Major Depressive Disorder in Children: A Case Study

National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations

- PBS Process

- Teaching Tools

Meet Brendan!

Brendan is a very happy, energetic, young boy. Prior to implementing Positive Behavior Support (PBS), Brendan had severe challenging behavior. Brendan and his family were physically, mentally, and emotionally exhausted and in desperate need of help. Brendan’s parents had tried absolutely everything in their “bag of tricks” but nothing seemed to work with their youngest son. They felt like they were failing!

PBS provided Brendan’s family with new hope. PBS was a match with their family routines and values and allowed Brendan’s parents to view their dreams and visions for their son as achievable.

Brendan is an example of a young boy who benefited from the process of Positive Behavior Support. This case study provides specific details of the success that Brendan and his family experienced with PBS. Below you will find products, videos, and materials produced and utilized that illustrate the steps the support team went through to determine the purpose of Brendan’s behavior and how they moved from conducting a Functional Assessment through the steps of the process to finally developing and implementing Brendan’s Behavior Support Plan.

“Positive Behavior Support is a set of tools that has allowed our children to more fully participate and succeed in everyday life .” -John Hornbeck, Brendan’s father

Components of Brendan’s Case Study

Brendan before pbs.

Brendan After PBS

Related Resources

General resources.

Link to this accordion

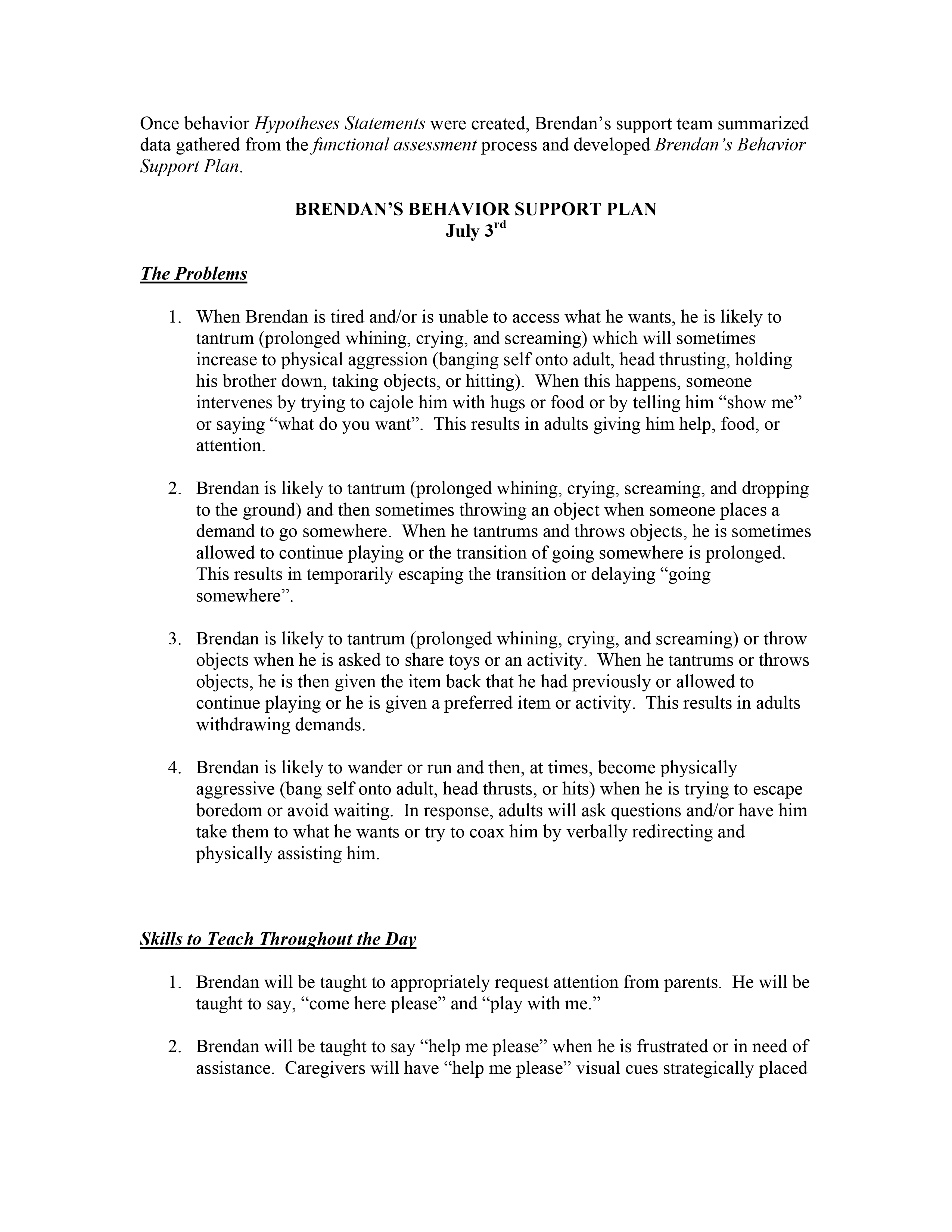

Sample behavior support plan

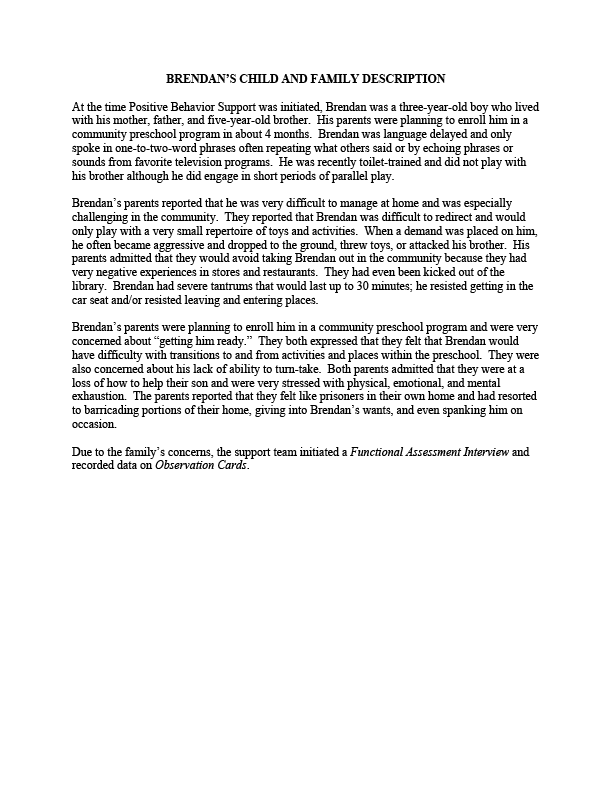

Case study child and family description

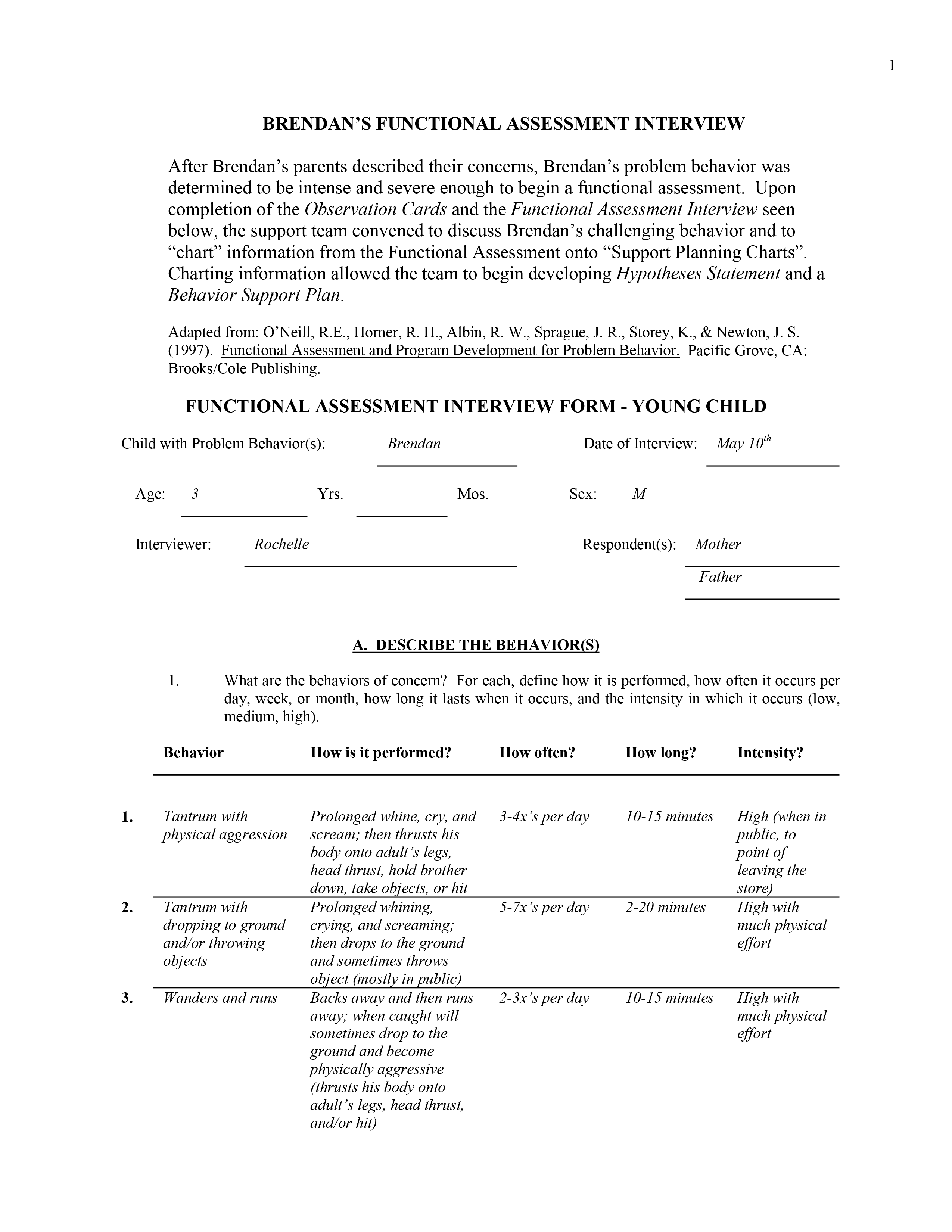

Sample functional assessment from case study

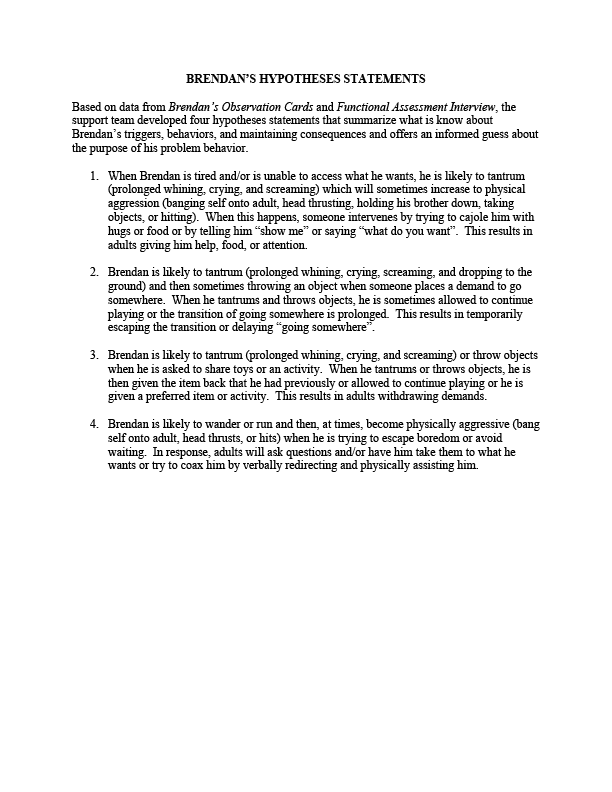

Hypotheses for Brendan’s case study

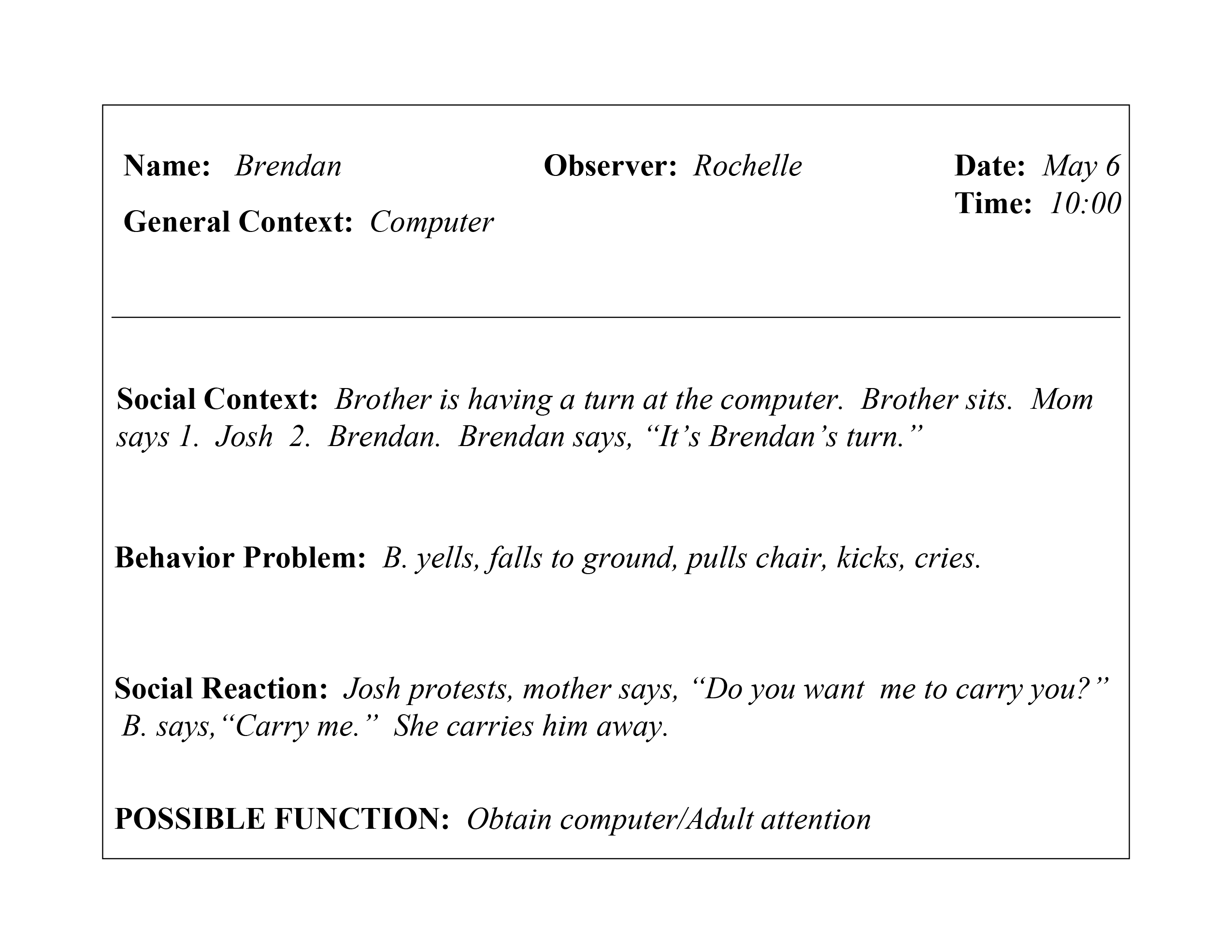

Observation data used in Brendan’s functional assessment

This booklet provides a report on the program-wide implementation of the “Teaching Pyramid” within a Head Start Program. The Southeast Kansas Community Action Program (SEK-CAP) provides information on the implementation of the model and the outcomes for the children, families, teachers, and program.

This website was made possible by Cooperative Agreement #H326B220002 which is funded by the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs. However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. This website is maintained by the University of South Florida . Contact webmaster . © University of South Florida

- Children's mental health case studies

- Parenting and caregiving

- Mental health

Explore the experiences of children and families with these interdisciplinary case studies. Designed to help professionals and students explore the strengths and needs of children and their families, each case presents a detailed situation, related research, problem-solving questions and feedback for the user. Use these cases on your own or in classes and training events

Each case study:

- Explores the experiences of a child and family over time.

- Introduces theories, research and practice ideas about children's mental health.

- Shows the needs of a child at specific stages of development.

- Invites users to “try on the hat” of different specific professionals.

By completing a case study participants will:

- Examine the needs of children from an interdisciplinary perspective.

- Recognize the importance of prevention/early intervention in children’s mental health.

- Apply ecological and developmental perspectives to children’s mental health.

- Predict probable outcomes for children based on services they receive.

Case studies prompt users to practice making decisions that are:

- Research-based.

- Practice-based.

- Best to meet a child and family's needs in that moment.

Children’s mental health service delivery systems often face significant challenges.

- Services can be disconnected and hard to access.

- Stigma can prevent people from seeking help.

- Parents, teachers and other direct providers can become overwhelmed with piecing together a system of care that meets the needs of an individual child.

- Professionals can be unaware of the theories and perspectives under which others serving the same family work

- Professionals may face challenges doing interdisciplinary work.

- Limited funding promotes competition between organizations trying to serve families.

These case studies help explore life-like mental health situations and decision-making. Case studies introduce characters with history, relationships and real-life problems. They offer users the opportunity to:

- Examine all these details, as well as pertinent research.

- Make informed decisions about intervention based on the available information.

The case study also allows users to see how preventive decisions can change outcomes later on. At every step, the case content and learning format encourages users to review the research to inform their decisions.

Each case study emphasizes the need to consider a growing child within ecological, developmental, and interdisciplinary frameworks.

- Ecological approaches consider all the levels of influence on a child.

- Developmental approaches recognize that children are constantly growing and developing. They may learn some things before other things.

- Interdisciplinary perspectives recognize that the needs of children will not be met within the perspectives and theories of a single discipline.

There are currently two different case students available. Each case study reflects a set of themes that the child and family experience.

The About Steven case study addresses:

- Adolescent depression.

- School mental health.

- Rural mental health services.

- Social/emotional development.

The Brianna and Tanya case study reflects themes of:

- Infant and early childhood mental health.

- Educational disparities.

- Trauma and toxic stress.

- Financial insecurity.

- Intergenerational issues.

The case studies are designed with many audiences in mind:

Practitioners from a variety of fields. This includes social work, education, nursing, public health, mental health, and others.

Professionals in training, including those attending graduate or undergraduate classes.

The broader community.

Each case is based on the research, theories, practices and perspectives of people in all these areas. The case studies emphasize the importance of considering an interdisciplinary framework. Children’s needs cannot be met within the perspective of a single discipline.

The complex problems children face need solutions that integrate many and diverse ways of knowing. The case studies also help everyone better understand the mental health needs of children. We all have a role to play.

These case has been piloted within:

Graduate and undergraduate courses.

Discipline-specific and interdisciplinary settings.

Professional organizations.

Currently, the case studies are being offered to instructors and their staff and students in graduate and undergraduate level courses. They are designed to supplement existing course curricula.

Instructors have used the case study effectively by:

- Assigning the entire case at one time as homework. This is followed by in-class discussion or a reflective writing assignment relevant to a course.

- Assigning sections of the case throughout the course. Instructors then require students to prepare for in-class discussion pertinent to that section.

- Creating writing, research or presentation assignments based on specific sections of course content.

- Focusing on a specific theme present in the case that is pertinent to the course. Instructors use this as a launching point for deeper study.

- Constructing other in-class creative experiences with the case.

- Collaborating with other instructors to hold interdisciplinary discussions about the case.

To get started with a particular case, visit the related web page and follow the instructions to register. Once you register as an instructor, you will receive information for your co-instructors, teaching assistants and students. Get more information on the following web pages.

- Brianna and Tanya: A case study about infant and early childhood mental health

- About Steven: A children’s mental health case study about depression

Cari Michaels, Extension educator

Reviewed in 2023

© 2024 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. The University of Minnesota is an equal opportunity educator and employer.

- Report Web Disability-Related Issue |

- Privacy Statement |

- Staff intranet

DBP Community Systems-Based Cases

Introduction.

Following are case studies of children with typical developmental behavioral issues that may require a host of referrals and recommendations.

Case Studies

Case 1: case 2: case 3: sophie mark alejandro.

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 11 September 2017

A case of a four-year-old child adopted at eight months with unusual mood patterns and significant polypharmacy

- Magdalena Romanowicz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4916-0625 1 ,

- Alastair J. McKean 1 &

- Jennifer Vande Voort 1

BMC Psychiatry volume 17 , Article number: 330 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

44k Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Long-term effects of neglect in early life are still widely unknown. Diversity of outcomes can be explained by differences in genetic risk, epigenetics, prenatal factors, exposure to stress and/or substances, and parent-child interactions. Very common sub-threshold presentations of children with history of early trauma are challenging not only to diagnose but also in treatment.

Case presentation

A Caucasian 4-year-old, adopted at 8 months, male patient with early history of neglect presented to pediatrician with symptoms of behavioral dyscontrol, emotional dysregulation, anxiety, hyperactivity and inattention, obsessions with food, and attachment issues. He was subsequently seen by two different child psychiatrists. Pharmacotherapy treatment attempted included guanfacine, fluoxetine and amphetamine salts as well as quetiapine, aripiprazole and thioridazine without much improvement. Risperidone initiated by primary care seemed to help with his symptoms of dyscontrol initially but later the dose had to be escalated to 6 mg total for the same result. After an episode of significant aggression, the patient was admitted to inpatient child psychiatric unit for stabilization and taper of the medicine.

Conclusions

The case illustrates difficulties in management of children with early history of neglect. A particular danger in this patient population is polypharmacy, which is often used to manage transdiagnostic symptoms that significantly impacts functioning with long term consequences.

Peer Review reports

There is a paucity of studies that address long-term effects of deprivation, trauma and neglect in early life, with what little data is available coming from institutionalized children [ 1 ]. Rutter [ 2 ], who studied formerly-institutionalized Romanian children adopted into UK families, found that this group exhibited prominent attachment disturbances, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), quasi-autistic features and cognitive delays. Interestingly, no other increases in psychopathology were noted [ 2 ].

Even more challenging to properly diagnose and treat are so called sub-threshold presentations of children with histories of early trauma [ 3 ]. Pincus, McQueen, & Elinson [ 4 ] described a group of children who presented with a combination of co-morbid symptoms of various diagnoses such as conduct disorder, ADHD, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety. As per Shankman et al. [ 5 ], these patients may escalate to fulfill the criteria for these disorders. The lack of proper diagnosis imposes significant challenges in terms of management [ 3 ].

J is a 4-year-old adopted Caucasian male who at the age of 2 years and 4 months was brought by his adoptive mother to primary care with symptoms of behavioral dyscontrol, emotional dysregulation, anxiety, hyperactivity and inattention, obsessions with food, and attachment issues. J was given diagnoses of reactive attachment disorder (RAD) and ADHD. No medications were recommended at that time and a referral was made for behavioral therapy.

She subsequently took him to two different child psychiatrists who diagnosed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD), PTSD, anxiety and a mood disorder. To help with mood and inattention symptoms, guanfacine, fluoxetine, methylphenidate and amphetamine salts were all prescribed without significant improvement. Later quetiapine, aripiprazole and thioridazine were tried consecutively without behavioral improvement (please see Table 1 for details).

No significant drug/substance interactions were noted (Table 1 ). There were no concerns regarding adherence and serum drug concentrations were not ordered. On review of patient’s history of medication trials guanfacine and methylphenidate seemed to have no effect on J’s hyperactive and impulsive behavior as well as his lack of focus. Amphetamine salts that were initiated during hospitalization were stopped by the patient’s mother due to significant increase in aggressive behaviors and irritability. Aripiprazole was tried for a brief period of time and seemed to have no effect. Quetiapine was initially helpful at 150 mg (50 mg three times a day), unfortunately its effects wore off quickly and increase in dose to 300 mg (100 mg three times a day) did not seem to make a difference. Fluoxetine that was tried for anxiety did not seem to improve the behaviors and was stopped after less than a month on mother’s request.

J’s condition continued to deteriorate and his primary care provider started risperidone. While initially helpful, escalating doses were required until he was on 6 mg daily. In spite of this treatment, J attempted to stab a girl at preschool with scissors necessitating emergent evaluation, whereupon he was admitted to inpatient care for safety and observation. Risperidone was discontinued and J was referred to outpatient psychiatry for continuing medical monitoring and therapy.

Little is known about J’s early history. There is suspicion that his mother was neglectful with feeding and frequently left him crying, unattended or with strangers. He was taken away from his mother’s care at 7 months due to neglect and placed with his aunt. After 1 month, his aunt declined to collect him from daycare, deciding she was unable to manage him. The owner of the daycare called Child Services and offered to care for J, eventually becoming his present adoptive parent.

J was a very needy baby who would wake screaming and was hard to console. More recently he wakes in the mornings anxious and agitated. He is often indiscriminate and inappropriate interpersonally, unable to play with other children. When in significant distress he regresses, and behaves as a cat, meowing and scratching the floor. Though J bonded with his adoptive mother well and was able to express affection towards her, his affection is frequently indiscriminate and he rarely shows any signs of separation anxiety.

At the age of 2 years and 8 months there was a suspicion for speech delay and J was evaluated by a speech pathologist who concluded that J was exhibiting speech and language skills that were solidly in the average range for age, with developmental speech errors that should be monitored over time. They did not think that issues with communication contributed significantly to his behavioral difficulties. Assessment of intellectual functioning was performed at the age of 2 years and 5 months by a special education teacher. Based on Bailey Infant and Toddler Development Scale, fine and gross motor, cognitive and social communication were all within normal range.

J’s adoptive mother and in-home therapist expressed significant concerns in regards to his appetite. She reports that J’s biological father would come and visit him infrequently, but always with food and sweets. J often eats to the point of throwing up and there have been occasions where he has eaten his own vomit and dog feces. Mother noticed there is an association between his mood and eating behaviors. J’s episodes of insatiable and indiscriminate hunger frequently co-occur with increased energy, diminished need for sleep, and increased speech. This typically lasts a few days to a week and is followed by a period of reduced appetite, low energy, hypersomnia, tearfulness, sadness, rocking behavior and slurred speech. Those episodes last for one to 3 days. Additionally, there are times when his symptomatology seems to be more manageable with fewer outbursts and less difficulty regarding food behaviors.

J’s family history is poorly understood, with his biological mother having a personality disorder and ADHD, and a biological father with substance abuse. Both maternally and paternally there is concern for bipolar disorder.

J has a clear history of disrupted attachment. He is somewhat indiscriminate in his relationship to strangers and struggles with impulsivity, aggression, sleep and feeding issues. In addition to early life neglect and possible trauma, J has a strong family history of psychiatric illness. His mood, anxiety and sleep issues might suggest underlying PTSD. His prominent hyperactivity could be due to trauma or related to ADHD. With his history of neglect, indiscrimination towards strangers, mood liability, attention difficulties, and heightened emotional state, the possibility of Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder (DSED) is likely. J’s prominent mood lability, irritability and family history of bipolar disorder, are concerning for what future mood diagnosis this portends.

As evidenced above, J presents as a diagnostic conundrum suffering from a combination of transdiagnostic symptoms that broadly impact his functioning. Unfortunately, although various diagnoses such as ADHD, PTSD, Depression, DMDD or DSED may be entertained, the patient does not fall neatly into any of the categories.

This is a case report that describes a diagnostic conundrum in a young boy with prominent early life deprivation who presented with multidimensional symptoms managed with polypharmacy.

A sub-threshold presentation in this patient partially explains difficulties with diagnosis. There is no doubt that negative effects of early childhood deprivation had significant impact on developmental outcomes in this patient, but the mechanisms that could explain the associations are still widely unknown. Significant family history of mental illness also predisposes him to early challenges. The clinical picture is further complicated by the potential dynamic factors that could explain some of the patient’s behaviors. Careful examination of J’s early life history would suggest such a pattern of being able to engage with his biological caregivers, being given food, being tended to; followed by periods of neglect where he would withdraw, regress and engage in rocking as a self-soothing behavior. His adoptive mother observed that visitations with his biological father were accompanied by being given a lot of food. It is also possible that when he was under the care of his biological mother, he was either attended to with access to food or neglected, left hungry and screaming for hours.

The current healthcare model, being centered on obtaining accurate diagnosis, poses difficulties for treatment in these patients. Given the complicated transdiagnostic symptomatology, clear guidelines surrounding treatment are unavailable. To date, there have been no psychopharmacological intervention trials for attachment issues. In patients with disordered attachment, pharmacologic treatment is typically focused on co-morbid disorders, even with sub-threshold presentations, with the goal of symptom reduction [ 6 ]. A study by dosReis [ 7 ] found that psychotropic usage in community foster care patients ranged from 14% to 30%, going to 67% in therapeutic foster care and as high as 77% in group homes. Another study by Breland-Noble [ 8 ] showed that many children receive more than one psychotropic medication, with 22% using two medications from the same class.

It is important to note that our patient received four different neuroleptic medications (quetiapine, aripiprazole, risperidone and thioridazine) for disruptive behaviors and impulsivity at a very young age. Olfson et al. [ 9 ] noted that between 1999 and 2007 there has been a significant increase in the use of neuroleptics for very young children who present with difficult behaviors. A preliminary study by Ercan et al. [ 10 ] showed promising results with the use of risperidone in preschool children with behavioral dyscontrol. Review by Memarzia et al. [ 11 ] suggested that risperidone decreased behavioral problems and improved cognitive-motor functions in preschoolers. The study also raised concerns in regards to side effects from neuroleptic medications in such a vulnerable patient population. Younger children seemed to be much more susceptible to side effects in comparison to older children and adults with weight gain being the most common. Weight gain associated with risperidone was most pronounced in pre-adolescents (Safer) [ 12 ]. Quetiapine and aripiprazole were also associated with higher rates of weight gain (Correll et al.) [ 13 ].

Pharmacokinetics of medications is difficult to assess in very young children with ongoing development of the liver and the kidneys. It has been observed that psychotropic medications in children have shorter half-lives (Kearns et al.) [ 14 ], which would require use of higher doses for body weight in comparison to adults for same plasma level. Unfortunately, that in turn significantly increases the likelihood and severity of potential side effects.

There is also a question on effects of early exposure to antipsychotics on neurodevelopment. In particular in the first 3 years of life there are many changes in developing brains, such as increase in synaptic density, pruning and increase in neuronal myelination to list just a few [ 11 ]. Unfortunately at this point in time there is a significant paucity of data that would allow drawing any conclusions.

Our case report presents a preschool patient with history of adoption, early life abuse and neglect who exhibited significant behavioral challenges and was treated with various psychotropic medications with limited results. It is important to emphasize that subthreshold presentation and poor diagnostic clarity leads to dangerous and excessive medication regimens that, as evidenced above is fairly common in this patient population.

Neglect and/or abuse experienced early in life is a risk factor for mental health problems even after adoption. Differences in genetic risk, epigenetics, prenatal factors (e.g., malnutrition or poor nutrition), exposure to stress and/or substances, and parent-child interactions may explain the diversity of outcomes among these individuals, both in terms of mood and behavioral patterns [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Considering that these children often present with significant functional impairment and a wide variety of symptoms, further studies are needed regarding diagnosis and treatment.

Abbreviations

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder

Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Reactive Attachment disorder

Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):e1001349. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349 . Epub 2012 Nov 27

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kreppner JM, O'Connor TG, Rutter M, English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team. Can inattention/overactivity be an institutional deprivation syndrome? J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2001;29(6):513–28. PMID: 11761285

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dejong M. Some reflections on the use of psychiatric diagnosis in the looked after or “in care” child population. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;15(4):589–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104510377705 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pincus HA, McQueen LE, Elinson L. Subthreshold mental disorders: Nosological and research recommendations. In: Phillips KA, First MB, Pincus HA, editors. Advancing DSM: dilemmas in psychiatric diagnosis. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2003. p. 129–44.

Google Scholar

Shankman SA, Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Small JW, Seeley JR, Altman SE. Subthreshold conditions as precursors for full syndrome disorders: a 15-year longitudinal study of multiple diagnostic classes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:1485–94.

AACAP. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with reactive attachment disorder of infancy and early childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:1206–18.

Article Google Scholar

dosReis S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, Soeken KL. Mental health services for youths in foster care and disabled youths. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(7):1094–9.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Breland-Noble AM, Elbogen EB, Farmer EMZ, Wagner HR, Burns BJ. Use of psychotropic medications by youths in therapeutic foster care and group homes. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(6):706–8.

Olfson M, Crystal S, Huang C. Trends in antipsychotic drug use by very young, privately insured children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:13–23.

PubMed Google Scholar

Ercan ES, Basay BK, Basay O. Risperidone in the treatment of conduct disorder in preschool children without intellectual disability. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2011;5:10.

Memarzia J, Tracy D, Giaroli G. The use of antipsychotics in preschoolers: a veto or a sensible last option? J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(4):303–19.

Safer DJ. A comparison of risperidone-induced weight gain across the age span. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:429–36.

Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2009;302:1765–73.

Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM, Alander SW. Developmental pharmacology – drug disposition, action, and therapy in infants and children. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1157–67.

Monk C, Spicer J, Champagne FA. Linking prenatal maternal adversity to developmental outcomes in infants: the role of epigenetic pathways. Dev Psychopathol. 2012;24(4):1361–76. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000764 . Review. PMID: 23062303

Cecil CA, Viding E, Fearon P, Glaser D, McCrory EJ. Disentangling the mental health impact of childhood abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;63:106–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.024 . [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 27914236

Nemeroff CB. Paradise lost: the neurobiological and clinical consequences of child abuse and neglect. Neuron. 2016;89(5):892–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.019 . Review. PMID: 26938439

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are also grateful to patient’s legal guardian for their support in writing this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Mayo Clinic, Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, 200 1st SW, Rochester, MN, 55901, USA

Magdalena Romanowicz, Alastair J. McKean & Jennifer Vande Voort

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MR, AJM, JVV conceptualized and followed up the patient. MR, AJM, JVV did literature survey and wrote the report and took part in the scientific discussion and in finalizing the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final document.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Magdalena Romanowicz .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication.

Written consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardian for publication of the patient’s details.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Romanowicz, M., McKean, A.J. & Vande Voort, J. A case of a four-year-old child adopted at eight months with unusual mood patterns and significant polypharmacy. BMC Psychiatry 17 , 330 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1492-y

Download citation

Received : 20 December 2016

Accepted : 01 September 2017

Published : 11 September 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1492-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Polypharmacy

- Disinhibited social engagement disorder

BMC Psychiatry

ISSN: 1471-244X

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Raising Kids

- Behavior & Development

10 Common Child Behavioral Problems and How To Solve Them

Learn about discipline strategies that work to address the most common child behavior problems, such as lying and defiance.

Too Much Screen Time

Food-related problems, disrespectful behavior, impulsive behavior, bedtime behavior problems, temper tantrums.

Whether you're raising an energetic child or you're dealing with a strong-willed one, certain child behavior problems are common at one point or another. The way you respond to these behavioral problems plays a major role in how likely your child is to repeat them in the future.

Child behavior problems are best addressed with consistent, age-appropriate discipline strategies . Below are some common children's behavior problems and what you can do to stop them.

KidStock / Blend Images / Getty Images

There are three main reasons kids lie:

- To get attention

- To avoid getting in trouble or to avoid responsibility

- To cover up a problem

Distinguishing the reason for the lie can help you determine the best course of action.

When you catch your child in a lie, ask: "Is that what really happened or what you wish would have happened?" Emphasize the importance of honesty by making honesty a family value and "tell the truth" a household rule.

When appropriate, give your child a consequence for lying after being given the chance to tell the truth. And make sure to offer positive reinforcement when they do tell the truth—especially when the truth could get them in trouble.

Whether your child ignores you when you tell them to pick up their toys or shouts "no!" when you tell them to stop banging a toy on the floor, defiance is a difficult behavior to address—and it can be very triggering for parents who grew up in authoritarian households . It’s also very normal and developmentally appropriate for kids to test limits at one time or another.

When your child is defiant, offer a single "when…then" warning. For example, "When you pick up your toys, then you will be able to watch TV." If your child doesn't comply after the warning, follow through with a related consequence. With consistency, your child will learn to listen the first time you speak .

Another common child behavior problem is resisting screen time limits . Whether your child screams when you tell them to shut off the TV or plays a game on your phone whenever you're not looking, too much screen time isn't healthy.

Establish clear rules for screen time. If your child becomes too dependent on electronics for entertainment, avoidance, or emotional regulation, dial back the screen time even more.

Be a healthy role model. Consider establishing a periodic, family-wide digital detox to ensure that everyone is able to function without their devices.

You may be dealing with a picky eater , or perhaps your child claims to be hungry every 10 minutes, or sneaks food during times when it's not allowed. Food-related behaviors can lead to power struggles and body image issues, so it's important to handle them carefully.

Proactively work to help your children develop a healthy attitude about food. Make it clear that food is meant to fuel your child's body, not to comfort them when they're sad or entertain them when they're bored. And instead of trying to please everyone at every meal, serve one balanced meal that is healthy for everyone, and set limits on snacking.

Name-calling, throwing things, and mocking you are just a few of the common behavior problems that show disrespect. If disrespectful behavior is not addressed appropriately, it will likely get worse with time.

If your child's intent is to get your attention, ignoring can be the best course of action. Show your child that sticking their tongue out at you doesn't result in the reaction they're looking for. If your child calls you a name, firmly and calmly speak to them about using kind words. Make clear that you will not allow them to use that language at home.

Most importantly, be a role model. Let your child see you being respectful to the people around you, from the cashier at the grocery store to your co-parent—and be sure to show your child respect as well.

Whining is a bad habit—and it's reinforced when it helps your child get what they want. It's important to curb whining before it becomes an even bigger problem. A good first course of action is to show your child that whining won't get them what they're after and offer positive attention when they stop whining.

Additionally, teach your child more appropriate ways to deal with uncomfortable emotions like disappointment . Show them that saying, "I'm sad we can't go to the playground today" will get them much better results than repeatedly whining about how unfair it is that you won't take them to play in a thunderstorm.

Young children tend to be physically impulsive, so it's not unusual for a toddler or preschooler to hit you or another child. Older children are more likely to be verbally impulsive, meaning they may blurt out unkind statements that hurt people's feelings.

There are many things you can do to teach your child impulse control skills. One simple way to reduce impulsive behavior is by praising your child each time they think before they act or speak. Say, "Great job using your words when you felt angry today," or, "That was a good choice to walk away when you were mad."

Teach anger management skills and self-discipline skills as well. Gaining control over emotions will help your child control behavior too.

Whether your child refuses to stay in bed or they insist on sleeping with you, bedtime challenges are common. Without appropriate intervention, your child may become sleep-deprived. Lack of sleep has been linked to increased behavior problems in young children. And sleep deprivation can lead to physical health issues, as well.

Establish clear bedtime rules and create a healthy bedtime routine. Consistency is key to helping kids establish healthy sleep habits. So even if you have to return your child to their room a dozen times in an hour, keep doing it. Eventually, their bedtime behavior will improve.

Your child's aggressive behavior might mean throwing a math book when they're frustrated with homework, or it could lead to outright punching a sibling when they're mad. Some kids become aggressive because they don't know how to handle their feelings in an appropriate way. Others are perfectionists who melt down any time things don't go the way they planned.

Aggressive behavior is normal for toddlers and preschoolers, but aggression should decrease over time as your child grows and gains new skills. Give your child an immediate consequence for any act of aggression. Remove your child from the situation, enforce a logical, related consequence , and use restitution to help your child make amends if they have hurt someone. If aggression doesn't get better over time, seek professional help.

Temper tantrums are most common in toddlers and preschoolers, but they can extend into grade school if they aren't addressed swiftly.

Calmly waiting out the tantrum and not giving in is often one of the best ways to handle them. Teach your children that stomping, screaming, or throwing themselves to the floor won't get them what they want, but that you are there to help them find their calm again. It's also important to show them better and more effective ways to express their needs and get those needs met.

If behavior problems aren't responding to your discipline strategies, or your child's behavior has started disrupting their education and peer relationships, don't hesitate to talk to a health care provider. In addition to getting professional guidance, you can rule out any underlying developmental issues, learning disabilities , or medical conditions that might be contributing to your child's behavior.

Lying and Children . The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . 2017.

Effects of Excessive Screen Time on Child Development: An Updated Review and Strategies for Management . Cureus . 2023.

Association between sleep habits and behavioral problems in early adolescence: a descriptive study . BMC Psychology . 2022.

Behavioral interventions for anger, irritability, and aggression in children and adolescents . Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2016.

Related Articles

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Ind Psychiatry J

- v.26(1); Jan-Jun 2017

A descriptive study of behavioral problems in schoolgoing children

Anindya kumar gupta.

Department of Psychiatry, Command Hospital (Air Force), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Monica Mongia

1 National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre, AIIMS, Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh, India

Ajoy Kumar Garg

2 Department of Pediatrics, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, India

Background:

Behavioral problems among schoolgoing children are of significant concern to teachers and parents. These are known to have both immediate and long-term unfavorable consequences. Despite the high prevalence, studies on psychiatric morbidity among school children are lacking in our country.

Materials and Methods:

Five hundred children aged 6–18 years were randomly selected from a government school in Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, and assessed for cognitive, emotional, or behavioral problems using standardized tools.

About 22.7% of children showed behavioral, cognitive, or emotional problems. Additional screening and evaluation tools pointed toward a higher prevalence of externalizing symptoms among boys than girls.

Conclusion:

The study highlights the importance of regular screening of school children for preventive as well as timely remedial measures.

About 20% of children and adolescents, globally, suffer from impairments due to various mental disorders. Suicide is reportedly the third major reason for death among adolescent population.[ 1 , 2 ] The alarming rise in the number of children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries leaves this population with inadequate attention from mental health professionals, minimal infrastructure, and limited resources for managing their mental health problems.[ 3 ]

The prevalence rates of behavioral problems across various studies conducted in different states in India vary, thus making it difficult to get a collective understanding of the extent of the problem. A study by Srinath et al ., in 2005, conducted on a community-based sample in Bengaluru, revealed the prevalence rates of behavioral problems to be around 12.5% in children up to 16 years of age.[ 4 ] Another study done on school children in Chandigarh found the rate of behavioral problems among 4–11 years’ old to be 6.3%.[ 5 ] As evident from the available literature, the overall rates of psychiatric illnesses among children and adolescent population across the various states in India and other middle- and low-income countries vary between 5% and 6%. A cursory look at the Western data on the subject indicates that these figures are still on the lower side as prevalence rates of behavioral problems among children and adolescents in Canada, Germany, and the USA have been reported to be 18.1%, 20.7%, and 21%, respectively.[ 6 ]

Further, many problems among this population do not meet the diagnostic criteria and are thus considered “subthreshold.” Nonetheless, the significant distress that children/adolescents and their families go through because of these mental health issues cannot be undermined.[ 7 ] Since research studies on psychiatric problems among children and adolescents in India are relatively few and variable in methodology, the present study was conducted with more robust screening and assessment measures to generate relevant data. This study thus improves our current understanding of the extent and type of behavioral problems among children and adolescents, in our cultural context.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval for the current study was obtained from the hospital ethics committee of the first author. In this descriptive study, 500 boys and girls from a government school in Kanpur in the age group of 6–18 years, without any diagnosed medical/surgical/psychiatric/other illnesses, were included after appropriate randomization. All parents/caregivers provided informed consent for participation in the current study. Brief screening was done using the parent-completed version (pediatric symptom checklist [PSC]; 4–10 years) and the youth self-report (Y-PSC; 11+ years) to assess cognitive, emotional, and behavioral problems.[ 8 ] After initial screening, wherever the score was found to be significant, children were selected for detailed evaluation. Further assessment was carried out using the following:

- Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL): The CBCL developed by Achenbach is a family of self-rated instruments that surveys a broad range of difficulties encountered in children from preschool age through adolescence. It is a multiaxial scale normed by age and gender[ 9 ]

- Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC): The WISC is an individually administered intelligence test for children between the ages of 6 and 16 years[ 10 ]

- Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS): CARS is a behavior rating scale intended to help diagnose autism[ 11 ]

- Conner's Rating Scale (CRS)-Revised: CRS-revised is an instrument that uses observer ratings and self-report ratings to help assess attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and evaluate problem behaviors in children and adolescents from the age of 3 years through 18 years.[ 12 ]

Of 500 children selected, 480 children underwent detailed assessments. Two-hundred and forty children in each age group, i.e., 6–10 years and 11–18 years, were administered PSC/Y-PSC, as applicable. Mean ages of boys, girls, and their scoring pattern in PSC are shown in Table 1 .

Distribution of mean age of children and comparison of scores

About 41 (17.08%) children demonstrated positive scores in PSC and 68 (28. 33%) for Y-PSC. The CBCL was then administered to evaluate behavioral problems. Table 1 shows the distribution of mean age of children along with their mean PSC/Y-PSC scores above cutoff. The difference was not found to be statistically significant across the groups and gender.

Table 2 shows the distribution of mean CBCL scores by gender and age groups where boys had significantly higher scores than girls. However, the relation of CBCL scores (above cutoff) to gender and different age groups was not found to be significant.

Distribution of mean child behavior checklist scores by gender and age groups

The common behavioral problems in school children who scored above cutoff ( n = 52) in CBCL were found to be argumentativeness (55%), followed by lack of concentration, restless, and hyperactive behavior. Gender-wise distribution of common behavioral problems noted lack of remorse, argumentativeness, and restlessness more in boys, compared to preoccupation with cleanliness and neatness, perfectionistic ideas, and argumentativeness among girls, though the difference was not statistically significant either.

All 52 children were administered CARS and none were found to have significant scores above cutoff. An assessment of intelligence noted 7 children of 52 to be below average in intelligence, though none had intellectual disability.

On administering CRS for ADHD on 27 children in the age group of 6–10 years, 14 were found to be above cutoff, and 15 children were above cutoff scores in children in the age group of 11 years and above ( n = 25). There were no statistically significant differences between boys and girls in CRS scores. Overall, the results showed that a brief screening instrument can be useful for using in schools to obtain a cross-sectional view of common behavioral problems in children, which can then be further assessed and intervention can be provided.

A total of 109 children (22.7%) were found to have behavioral problems with initial screening by PSC/Y-PSC. This is slightly higher than another Indian study,[ 4 ] but similar to study by Muzammil et al .[ 13 ] and Malhotra andPatra.[ 14 ] Few western studies have shown higher prevalence rates.[ 15 , 16 , 17 ] The disparate estimate of prevalence and need for national data on epidemiology has been highlighted by Sharan and Sagar.[ 18 ] It emphasizes that although available Indian studies have started to address the unmet need for systematic information tracking of the prevalence and distribution of mental disorders, national data are still not available. The absence of empirical data on the magnitude, course, and treatment patterns of various mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of children and adolescents has largely restricted the efforts essential for establishing mental health policy for this population.

The mean CBCL scores of this study population were higher than most similar studies in India.[ 5 , 19 ] This can be attributed to the type of study population (school based vs. community based) and informant chosen (teachers/parents) among other factors. CBCL was being used in the present study in a population which was already screened for behavioral problems by PSC/Y-PSC, this put together with greater sensitivity of CBCL, growing concern among teachers and parents of behavioral problems or even growing magnitude of behavioral disturbances may have contributed to a higher mean score. The epidemiological issues of different vantage points have been discussed by Wolpert.[ 20 ]

The analysis of CBCL scores showed significant differences between the mean scores of boys and girls who scored above cutoff, as per age groups. This was similar to the findings by Malhotra et al .,[ 21 ] which is a clinic-based study with advantage of long-term data. The age-wise distribution of positive CBCL scores did not show any significant difference between the two groups.

The analysis for a pattern of distribution of behavioral problems in children revealed them to be more of externalizing ones. This goes along with the findings by Chaudhury et al .,[ 22 ] Shetty and Shihabuddeen,[ 23 ] and Shastri et al .[ 24 ] Girls had more internalizing behavioral problems whereas boys had more externalizing problems.

Overall difference was not significant which could be due to the small size of CBCL screened sample ( n = 52) only analyzed for these dimensions. This is similar to the findings by Deb et al .[ 25 ] No cases of autism spectrum disorder were found in this study when CARS was applied to this group of children. This is possibly due to the fact that the average age for diagnosis of children with the above disabilities is 3–4 years and these are not common in general population. This finding is similar to the study by Malhi and Singhi[ 26 ] and Vijay Sagar.[ 27 ]

Majority of children among the screened study population showed intelligence level in average range, and no cases of intellectual disability were noted though few ( n = 7) children were noted to have below average intelligence. This is similar to other school-based studies in India by Eshwar et al .[ 28 ] and Basu.[ 29 ]

Analysis of CRS when applied to these children for ADHD and related disturbances did not show a significant difference between the groups. This is similar to the study by Meyer et al .[ 30 ]

Relation of CRS scores in both genders was analyzed in respect of total number of children who scored positive in CBCL. The difference in boys and girls were not found to be significant. This is similar to the findings by Efron et al .[ 31 ] and Malhotra and Patra.[ 14 ]

All the children who showed positive scores in tests were taken up for remedial treatment or referred for further follow-up as per target symptoms.

About 22.7% of children among the total study population were found to have behavioral problems such as anxiety, hyperactivity, argumentativeness, and perfectionist ideas during initial screening which needed attention. Boys showed more externalizing behavioral problems and girls more internalizing ones. There were no children with intellectual disability or pervasive developmental disorders although ADHD was noted and addressed. This finding is close to the findings of various western studies where up to a quarter of children have various mental health issues, but higher than the available Indian studies quoted – where a different vantage point and methodology may have been responsible.

This study emphasizes the need for periodic screening of children among schools for behavioral problems which may serve as early indicators of future psychopathology. Once a detailed assessment of behavioral problems is over, life skills training modules developed by the World Health Organization for schools may help schools in reducing the number of behavioral problems and development of psychopathology among children.

This study, however, has the following limitations:

- The study is a descriptive study, trying to find out the extent of various behavioral problems in schoolgoing children. Participants may not be truthful or may not behave naturally when they know they are being observed

- Descriptive studies cannot be used to correlate variables or determine cause and effect

- Researcher bias may play a role in selection of the questionnaire and interpretation

- Findings may not be replicable in a different population

- Findings may be open to interpretation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Case Examples

Examples of recommended interventions in the treatment of depression across the lifespan.

Children/Adolescents

A 15-year-old Puerto Rican female

The adolescent was previously diagnosed with major depressive disorder and treated intermittently with supportive psychotherapy and antidepressants. Her more recent episodes related to her parents’ marital problems and her academic/social difficulties at school. She was treated using cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Chafey, M.I.J., Bernal, G., & Rossello, J. (2009). Clinical Case Study: CBT for Depression in A Puerto Rican Adolescent. Challenges and Variability in Treatment Response. Depression and Anxiety , 26, 98-103. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20457

Sam, a 15-year-old adolescent

Sam was team captain of his soccer team, but an unexpected fight with another teammate prompted his parents to meet with a clinical psychologist. Sam was diagnosed with major depressive disorder after showing an increase in symptoms over the previous three months. Several recent challenges in his family and romantic life led the therapist to recommend interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents (IPT-A).

Hall, E.B., & Mufson, L. (2009). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents (IPT-A): A Case Illustration. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38 (4), 582-593. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410902976338

© Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (Div. 53) APA, https://sccap53.org/, reprinted by permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com on behalf of the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (Div. 53) APA.

General Adults

Mark, a 43-year-old male

Mark had a history of depression and sought treatment after his second marriage ended. His depression was characterized as being “controlled by a pattern of interpersonal avoidance.” The behavior/activation therapist asked Mark to complete an activity record to help steer the treatment sessions.

Dimidjian, S., Martell, C.R., Addis, M.E., & Herman-Dunn, R. (2008). Chapter 8: Behavioral activation for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 343-362). New York: Guilford Press.

Reprinted with permission from Guilford Press.

Denise, a 59-year-old widow

Denise is described as having “nonchronic depression” which appeared most recently at the onset of her husband’s diagnosis with brain cancer. Her symptoms were loneliness, difficulty coping with daily life, and sadness. Treatment included filling out a weekly activity log and identifying/reconstructing automatic thoughts.

Young, J.E., Rygh, J.L., Weinberger, A.D., & Beck, A.T. (2008). Chapter 6: Cognitive therapy for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 278-287). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Nancy, a 25-year-old single, white female

Nancy described herself as being “trapped by her relationships.” Her intake interview confirmed symptoms of major depressive disorder and the clinician recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Persons, J.B., Davidson, J. & Tompkins, M.A. (2001). A Case Example: Nancy. In Essential Components of Cognitive-Behavior Therapy For Depression (pp. 205-242). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10389-007

While APA owns the rights to this text, some exhibits are property of the San Francisco Bay Area Center for Cognitive Therapy, which has granted the APA permission for use.

Luke, a 34-year-old male graduate student

Luke is described as having treatment-resistant depression and while not suicidal, hoped that a fatal illness would take his life or that he would just disappear. His treatment involved mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, which helps participants become aware of and recharacterize their overwhelming negative thoughts. It involves regular practice of mindfulness techniques and exercises as one component of therapy.

Sipe, W.E.B., & Eisendrath, S.J. (2014). Chapter 3 — Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy For Treatment-Resistant Depression. In R.A. Baer (Ed.), Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches (2nd ed., pp. 66-70). San Diego: Academic Press.

Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

Sara, a 35-year-old married female

Sara was referred to treatment after having a stillbirth. Sara showed symptoms of grief, or complicated bereavement, and was diagnosed with major depression, recurrent. The clinician recommended interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for a duration of 12 weeks.

Bleiberg, K.L., & Markowitz, J.C. (2008). Chapter 7: Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: a treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 315-323). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Peggy, a 52-year-old white, Italian-American widow

Peggy had a history of chronic depression, which flared during her husband’s illness and ultimate death. Guilt was a driving factor of her depressive symptoms, which lasted six months after his death. The clinician treated Peggy with psychodynamic therapy over a period of two years.

Bishop, J., & Lane , R.C. (2003). Psychodynamic Treatment of a Case of Grief Superimposed On Melancholia. Clinical Case Studies , 2(1), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650102239085

Several case examples of supportive therapy

Winston, A., Rosenthal, R.N., & Pinsker, H. (2004). Introduction to Supportive Psychotherapy . Arlington, VA : American Psychiatric Publishing.

Older Adults

Several case examples of interpersonal psychotherapy & pharmacotherapy

Miller, M. D., Wolfson, L., Frank, E., Cornes, C., Silberman, R., Ehrenpreis, L.…Reynolds, C. F., III. (1998). Using Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) in a Combined Psychotherapy/Medication Research Protocol with Depressed Elders: A Descriptive Report With Case Vignettes. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research , 7(1), 47-55.

Internet Explorer is no longer supported

Please upgrade to Microsoft Edge , Google Chrome , or Firefox .

Lo sentimos, la página que usted busca no se ha podido encontrar. Puede intentar su búsqueda de nuevo o visitar la lista de temas populares.

Get this as a PDF

Enter email to download and get news and resources in your inbox.

Share this on social

Managing problem behavior at home.

A guide to more confident, consistent and effective parenting

What You'll Learn

- How can parents help kids behave better?

- What are common mistakes parents make when managing behavior?

- How can using positive reinforcement help?

Kids’ difficult behavior can be a huge challenge for parents . But by using techniques from behavioral therapy, parents can change the way kids react to the things that set them off .

The first step is picking specific behaviors to target. Then, think about what causes the target behaviors. These causes are called triggers or “antecedents.” Often, antecedents are things that parents themselves do. For example, you might notice that your child tends to have a tantrum when you ask them to switch activities. Or you might see that your child doesn’t follow instructions if it’s something they don’t want to do .

The goal is to help children improve their behavior by using more helpful antecedents. For instance, a positive antecedent that helps kids with transitions is counting down to them so they have time to adjust. To help kids follow instructions, you might try giving them choices (“Do you want a shower after dinner or before?”), and not asking too much when your child is hungry, tired, or distracted.

When kids act out in a minor way, ignoring it usually works best. And if you do use punishment, it should happen right away and happen the same way every time. Punishments like yelling and spanking can actually reinforce misbehavior because they give the child attention. It usually works better to use a short time-out, which takes your attention away from the child.

Most importantly, give your child clear, specific rules about what is okay and what isn’t. And give them lots of praise when they behave well . In most cases of minor misbehavior, waiting for your child do something positive (like stop yelling) and then immediately giving them positive attention will help them learn to behave better over time.

One of the biggest challenges parents face is managing difficult or defiant behavior on the part of children. Whether they’re refusing to put on their shoes, or throwing full-blown tantrums , you can find yourself at a loss for an effective way to respond.

For parents at their wits end, behavioral therapy techniques can provide a roadmap to calmer, more consistent ways to manage problem behaviors problems and offers a chance to help children develop gain the developmental skills they need to regulate their own behaviors.

ABC’s of behavior management at home

To understand and respond effectively to problematic behavior , you have to think about what came before it, as well as what comes after it. There are three important aspects to any given behavior:

- Antecedents: Preceding factors that make a behavior more or less likely to occur. Another, more familiar term for this is triggers. Learning and anticipating antecedents is an extremely helpful tool in preventing misbehavior.

- Behaviors: The specific actions you are trying to encourage or discourage.

- Consequences: The results that naturally or logically follow a behavior. Consequences — positive or negative — affect the likelihood of a behavior recurring. And the more immediate the consequence, the more powerful it is.

Define behaviors

The first step in a good behavior management plan is to identify target behaviors. These behaviors should be specific (so everyone is clear on what is expected), observable , and measurable (so everyone can agree whether or not the behavior happened).

An example of poorly defined behavior is “acting up,” or “being good.” A well-defined behavior would be running around the room (bad) or starting homework on time (good).

Antecedents, the good and the bad

Antecedents come in many forms. Some prop up bad behavior, others are helpful tools that help parents manage potentially problematic behaviors before they begin and bolster good behavior.

Antecedents to AVOID:

- Assuming expectations are understood: Don’t assume kids know what is expected of them — spell it out! Demands change from situation to situation and when children are unsure of what they are supposed to be doing, they’re more likely to misbehave.

- Calling things out from a distance: Be sure to tell children important instructions face-to-face. Things yelled from a distance are less likely to be remembered and understood.

- Transitioning without warning: Transitions can be hard for kids, especially in the middle of something they are enjoying. Having warning gives children the chance to find a good stopping place for an activity and makes the transition less fraught.

- Asking rapid-fire questions, or giving a series of instructions: Delivering a series of questions or instructions at children limits the likelihood that they will hear, answer questions, remember the tasks, and do what they’ve been instructed to do.

Antecedents to EMBRACE:

Here are some antecedents that can bolster good behavior:

- Be aware of the situation: Consider and manage environmental and emotional factors — hunger, fatigue, anxiety or distractions can all make it much more difficult for children to rein in their behavior.

- Adjust the environment: When it’s homework time , for instance, remove distractions like video screens and toys, provide a snacks, establish an organized place for kids to work and make sure to schedule some breaks — attention isn’t infinite.

- Make expectations clear: You’ll get better cooperation if both you and your child are clear on what’s expected. Sit down with him and present the information verbally. Even if he “should” know what is expected, clarifying expectations at the outset of a task helps head off misunderstandings down the line.

- Provide countdowns for transitions : Whenever possible, prepare children for an upcoming transition . Let them know when there are, say, 10 minutes remaining before they must come to dinner or start their homework. Then, remind them, when there are say, 2 minutes, left. Just as important as issuing the countdown is actually making the transition at the stated time.

- Let kids have a choice: As kids grow up, it’s important they have a say in their own scheduling. Giving a structured choice — “Do you want to take a shower after dinner or before?” — can help them feel empowered and encourage them to become more self-regulating.

Creating effective consequences

Not all consequences are created equal. Some are an excellent way to create structure and help kids understand the difference between acceptable behaviors and unacceptable behaviors while others have the potential to do more harm than good. As a parent having a strong understanding of how to intelligently and consistently use consequences can make all the difference.

Consequences to AVOID

- Giving negative attention: Children value attention from the important adults in their life so much that any attention — positive or negative — is better than none. Negative attention, such as raising your voice or spanking — actually increases bad behavior over time. Also, responding to behaviors with criticism or yelling adversely affects children’s self-esteem.

- Delayed consequences: The most effective consequences are immediate. Every moment that passes after a behavior, your child is less likely to link her behavior to the consequence. It becomes punishing for the sake of punishing, and it’s much less likely to actually change the behavior.

- Disproportionate consequences: Parents understandably get very frustrated. At times, they may be so frustrated that they overreact. A huge consequence can be demoralizing for children and they may give up even trying to behave.

- Positive consequences: When a child dawdles instead of putting on his shoes or picking up his blocks and, in frustration, you do it for him, you’re increasing the likelihood that he will dawdle again next time.

EFFECTIVE consequences:

Consequences that are more effective begin with generous attention to the behaviors you want to encourage.

- Positive attention for positive behaviors: Giving your child positive reinforcement for being good helps maintain the ongoing good behavior. Positive attention enhances the quality of the relationship, improves self-esteem, and feels good for everyone involved. Positive attention to brave behavior can also help attenuate anxiety, and help kids become more receptive to instructions and limit-setting.

- Ignoring actively: This should used ONLY with minor misbehaviors — NOT aggression and NOT very destructive behavior. Active ignoring involves the deliberate withdrawal of attention when a child starts to misbehave — as you ignore, you wait for positive behavior to resume. You want to give positive attention as soon as the desired behavior starts. By withholding your attention until you get positive behavior you are teaching your child what behavior gets you to engage.

- Reward menus: Rewards are a tangible way to give children positive feedback for desired behaviors. A reward is something a child earns, an acknowledgement that she’s doing something that’s difficult for her. Rewards are most effective as motivators when the child can choose from a variety of things: extra time on the iPad, a special treat, etc. This offers the child agency and reduces the possibility of a reward losing its appeal over time. Rewards should be linked to specific behaviors and always delivered consistently.

- Time outs : Time outs are one of the most effective consequences parents can use but also one of the hardest to do correctly. Here’s a quick guide to effective time out strategies .

- Be clear: Establish which behaviors will result in time outs. When a child exhibits that behavior, make sure the corresponding time out is relatively brief and immediately follows a negative behavior.

- Be consistent: Randomly administering time outs when you’re feeling frustrated undermines the system and makes it harder for the child to connect behaviors with consequences.

- Set rules and follow them: During a time out, there should be no talking to the child until you are ending the time out. Time out should end only once the child has been calm and quiet briefly so they learn to associate the end of time out with this desired behavior.

- Return to the task: If time out was issued for not complying with a task, once it ends the child should be instructed to complete the original task. This way, kids won’t begin to see time outs as an escape strategy.

By bringing practicing behavioral tools management at home, parents can make it a much more peaceful place to be.

Frequently Asked Questions

Parents can improve problem behavior at home using techniques from behavioral therapy, which can change the way kids act. Maybe your child tends to have a tantrum when you ask them to switch activities. To help, you might try counting down, so they have time to adjust.

When it comes to improving bad behavior at home, parents should know that positive reinforcement of good behaviors works better than punishment. Also, try not to ask too much when your child is hungry, tired, or distracted.

Active ignoring can help improve bad behavior — but only when kids act out in a minor way. Active ignoring means deliberately withdrawing your attention when a child misbehaves and then giving positive attention as soon as the desired behavior starts.

Was this article helpful?