We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies

These cookies help us analyze how many people are using Venngage, where they come from and how they're using it. If you opt out of these cookies, we can’t get feedback to make Venngage better for you and all our users.

- Google Analytics

Targeting Cookies

These cookies are set by our advertising partners to track your activity and show you relevant Venngage ads on other sites as you browse the internet.

- Google Tag Manager

- Infographics

- Daily Infographics

- Popular Templates

- Accessibility

- Graphic Design

- Graphs and Charts

- Data Visualization

- Human Resources

- Beginner Guides

Blog Business How to Present a Case Study like a Pro (With Examples)

How to Present a Case Study like a Pro (With Examples)

Written by: Danesh Ramuthi Sep 07, 2023

Okay, let’s get real: case studies can be kinda snooze-worthy. But guess what? They don’t have to be!

In this article, I will cover every element that transforms a mere report into a compelling case study, from selecting the right metrics to using persuasive narrative techniques.

And if you’re feeling a little lost, don’t worry! There are cool tools like Venngage’s Case Study Creator to help you whip up something awesome, even if you’re short on time. Plus, the pre-designed case study templates are like instant polish because let’s be honest, everyone loves a shortcut.

Click to jump ahead:

What is a case study presentation?

What is the purpose of presenting a case study, how to structure a case study presentation, how long should a case study presentation be, 5 case study presentation examples with templates, 6 tips for delivering an effective case study presentation, 5 common mistakes to avoid in a case study presentation, how to present a case study faqs.

A case study presentation involves a comprehensive examination of a specific subject, which could range from an individual, group, location, event, organization or phenomenon.

They’re like puzzles you get to solve with the audience, all while making you think outside the box.

Unlike a basic report or whitepaper, the purpose of a case study presentation is to stimulate critical thinking among the viewers.

The primary objective of a case study is to provide an extensive and profound comprehension of the chosen topic. You don’t just throw numbers at your audience. You use examples and real-life cases to make you think and see things from different angles.

The primary purpose of presenting a case study is to offer a comprehensive, evidence-based argument that informs, persuades and engages your audience.

Here’s the juicy part: presenting that case study can be your secret weapon. Whether you’re pitching a groundbreaking idea to a room full of suits or trying to impress your professor with your A-game, a well-crafted case study can be the magic dust that sprinkles brilliance over your words.

Think of it like digging into a puzzle you can’t quite crack . A case study lets you explore every piece, turn it over and see how it fits together. This close-up look helps you understand the whole picture, not just a blurry snapshot.

It’s also your chance to showcase how you analyze things, step by step, until you reach a conclusion. It’s all about being open and honest about how you got there.

Besides, presenting a case study gives you an opportunity to connect data and real-world scenarios in a compelling narrative. It helps to make your argument more relatable and accessible, increasing its impact on your audience.

One of the contexts where case studies can be very helpful is during the job interview. In some job interviews, you as candidates may be asked to present a case study as part of the selection process.

Having a case study presentation prepared allows the candidate to demonstrate their ability to understand complex issues, formulate strategies and communicate their ideas effectively.

The way you present a case study can make all the difference in how it’s received. A well-structured presentation not only holds the attention of your audience but also ensures that your key points are communicated clearly and effectively.

In this section, let’s go through the key steps that’ll help you structure your case study presentation for maximum impact.

Let’s get into it.

Open with an introductory overview

Start by introducing the subject of your case study and its relevance. Explain why this case study is important and who would benefit from the insights gained. This is your opportunity to grab your audience’s attention.

Explain the problem in question

Dive into the problem or challenge that the case study focuses on. Provide enough background information for the audience to understand the issue. If possible, quantify the problem using data or metrics to show the magnitude or severity.

Detail the solutions to solve the problem

After outlining the problem, describe the steps taken to find a solution. This could include the methodology, any experiments or tests performed and the options that were considered. Make sure to elaborate on why the final solution was chosen over the others.

Key stakeholders Involved

Talk about the individuals, groups or organizations that were directly impacted by or involved in the problem and its solution.

Stakeholders may experience a range of outcomes—some may benefit, while others could face setbacks.

For example, in a business transformation case study, employees could face job relocations or changes in work culture, while shareholders might be looking at potential gains or losses.

Discuss the key results & outcomes

Discuss the results of implementing the solution. Use data and metrics to back up your statements. Did the solution meet its objectives? What impact did it have on the stakeholders? Be honest about any setbacks or areas for improvement as well.

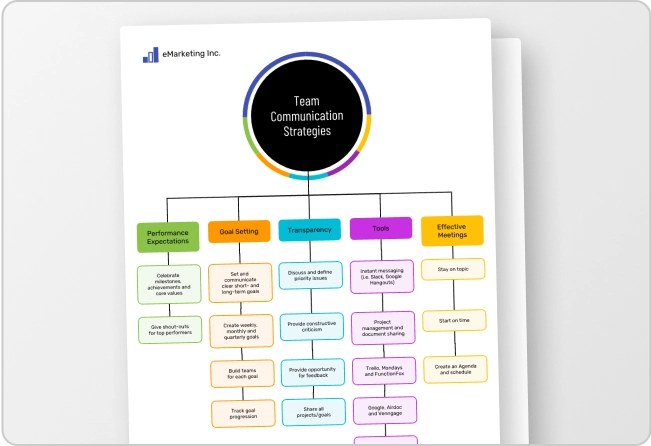

Include visuals to support your analysis

Visual aids can be incredibly effective in helping your audience grasp complex issues. Utilize charts, graphs, images or video clips to supplement your points. Make sure to explain each visual and how it contributes to your overall argument.

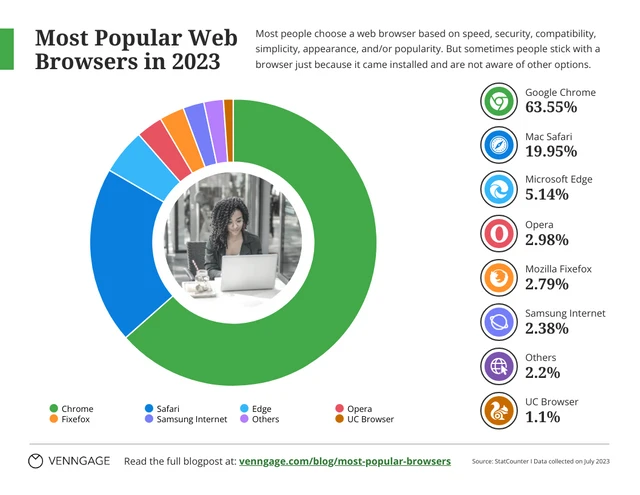

Pie charts illustrate the proportion of different components within a whole, useful for visualizing market share, budget allocation or user demographics.

This is particularly useful especially if you’re displaying survey results in your case study presentation.

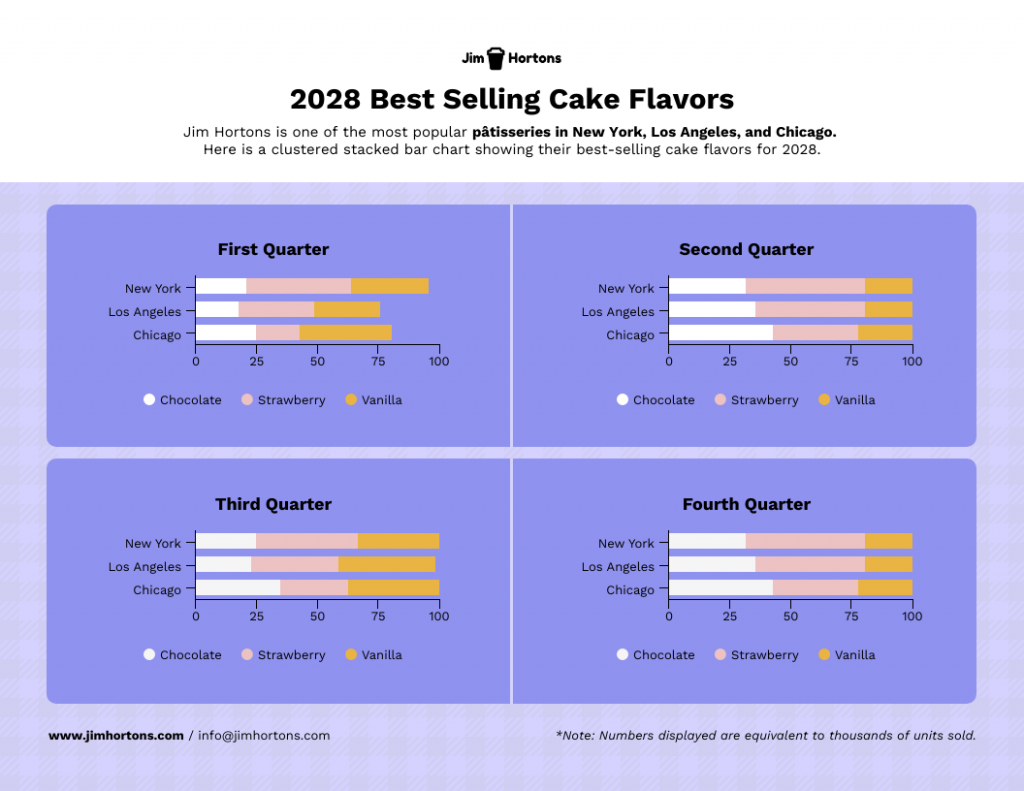

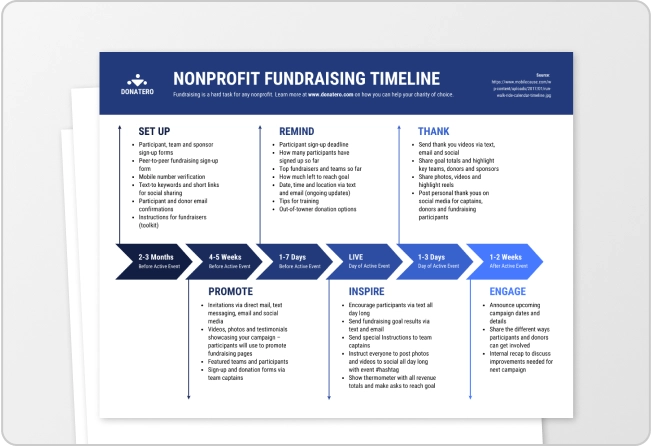

Stacked charts on the other hand are perfect for visualizing composition and trends. This is great for analyzing things like customer demographics, product breakdowns or budget allocation in your case study.

Consider this example of a stacked bar chart template. It provides a straightforward summary of the top-selling cake flavors across various locations, offering a quick and comprehensive view of the data.

Not the chart you’re looking for? Browse Venngage’s gallery of chart templates to find the perfect one that’ll captivate your audience and level up your data storytelling.

Recommendations and next steps

Wrap up by providing recommendations based on the case study findings. Outline the next steps that stakeholders should take to either expand on the success of the project or address any remaining challenges.

Acknowledgments and references

Thank the people who contributed to the case study and helped in the problem-solving process. Cite any external resources, reports or data sets that contributed to your analysis.

Feedback & Q&A session

Open the floor for questions and feedback from your audience. This allows for further discussion and can provide additional insights that may not have been considered previously.

Closing remarks

Conclude the presentation by summarizing the key points and emphasizing the takeaways. Thank your audience for their time and participation and express your willingness to engage in further discussions or collaborations on the subject.

Well, the length of a case study presentation can vary depending on the complexity of the topic and the needs of your audience. However, a typical business or academic presentation often lasts between 15 to 30 minutes.

This time frame usually allows for a thorough explanation of the case while maintaining audience engagement. However, always consider leaving a few minutes at the end for a Q&A session to address any questions or clarify points made during the presentation.

When it comes to presenting a compelling case study, having a well-structured template can be a game-changer.

It helps you organize your thoughts, data and findings in a coherent and visually pleasing manner.

Not all case studies are created equal and different scenarios require distinct approaches for maximum impact.

To save you time and effort, I have curated a list of 5 versatile case study presentation templates, each designed for specific needs and audiences.

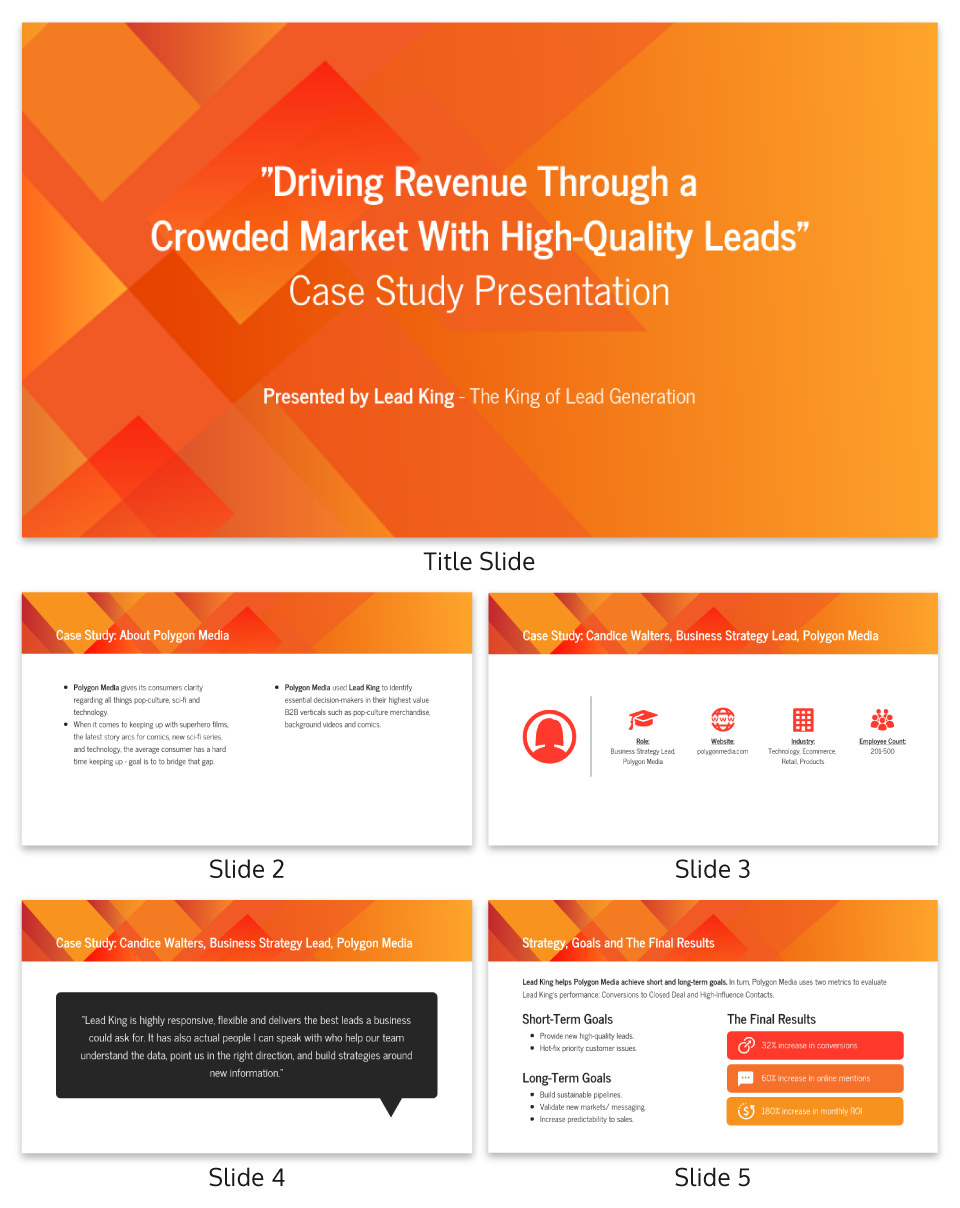

Here are some best case study presentation examples that showcase effective strategies for engaging your audience and conveying complex information clearly.

1 . Lab report case study template

Ever feel like your research gets lost in a world of endless numbers and jargon? Lab case studies are your way out!

Think of it as building a bridge between your cool experiment and everyone else. It’s more than just reporting results – it’s explaining the “why” and “how” in a way that grabs attention and makes sense.

This lap report template acts as a blueprint for your report, guiding you through each essential section (introduction, methods, results, etc.) in a logical order.

Want to present your research like a pro? Browse our research presentation template gallery for creative inspiration!

2. Product case study template

It’s time you ditch those boring slideshows and bullet points because I’ve got a better way to win over clients: product case study templates.

Instead of just listing features and benefits, you get to create a clear and concise story that shows potential clients exactly what your product can do for them. It’s like painting a picture they can easily visualize, helping them understand the value your product brings to the table.

Grab the template below, fill in the details, and watch as your product’s impact comes to life!

3. Content marketing case study template

In digital marketing, showcasing your accomplishments is as vital as achieving them.

A well-crafted case study not only acts as a testament to your successes but can also serve as an instructional tool for others.

With this coral content marketing case study template—a perfect blend of vibrant design and structured documentation, you can narrate your marketing triumphs effectively.

4. Case study psychology template

Understanding how people tick is one of psychology’s biggest quests and case studies are like magnifying glasses for the mind. They offer in-depth looks at real-life behaviors, emotions and thought processes, revealing fascinating insights into what makes us human.

Writing a top-notch case study, though, can be a challenge. It requires careful organization, clear presentation and meticulous attention to detail. That’s where a good case study psychology template comes in handy.

Think of it as a helpful guide, taking care of formatting and structure while you focus on the juicy content. No more wrestling with layouts or margins – just pour your research magic into crafting a compelling narrative.

5. Lead generation case study template

Lead generation can be a real head-scratcher. But here’s a little help: a lead generation case study.

Think of it like a friendly handshake and a confident resume all rolled into one. It’s your chance to showcase your expertise, share real-world successes and offer valuable insights. Potential clients get to see your track record, understand your approach and decide if you’re the right fit.

No need to start from scratch, though. This lead generation case study template guides you step-by-step through crafting a clear, compelling narrative that highlights your wins and offers actionable tips for others. Fill in the gaps with your specific data and strategies, and voilà! You’ve got a powerful tool to attract new customers.

Related: 15+ Professional Case Study Examples [Design Tips + Templates]

So, you’ve spent hours crafting the perfect case study and are now tasked with presenting it. Crafting the case study is only half the battle; delivering it effectively is equally important.

Whether you’re facing a room of executives, academics or potential clients, how you present your findings can make a significant difference in how your work is received.

Forget boring reports and snooze-inducing presentations! Let’s make your case study sing. Here are some key pointers to turn information into an engaging and persuasive performance:

- Know your audience : Tailor your presentation to the knowledge level and interests of your audience. Remember to use language and examples that resonate with them.

- Rehearse : Rehearsing your case study presentation is the key to a smooth delivery and for ensuring that you stay within the allotted time. Practice helps you fine-tune your pacing, hone your speaking skills with good word pronunciations and become comfortable with the material, leading to a more confident, conversational and effective presentation.

- Start strong : Open with a compelling introduction that grabs your audience’s attention. You might want to use an interesting statistic, a provocative question or a brief story that sets the stage for your case study.

- Be clear and concise : Avoid jargon and overly complex sentences. Get to the point quickly and stay focused on your objectives.

- Use visual aids : Incorporate slides with graphics, charts or videos to supplement your verbal presentation. Make sure they are easy to read and understand.

- Tell a story : Use storytelling techniques to make the case study more engaging. A well-told narrative can help you make complex data more relatable and easier to digest.

Ditching the dry reports and slide decks? Venngage’s case study templates let you wow customers with your solutions and gain insights to improve your business plan. Pre-built templates, visual magic and customer captivation – all just a click away. Go tell your story and watch them say “wow!”

Nailed your case study, but want to make your presentation even stronger? Avoid these common mistakes to ensure your audience gets the most out of it:

Overloading with information

A case study is not an encyclopedia. Overloading your presentation with excessive data, text or jargon can make it cumbersome and difficult for the audience to digest the key points. Stick to what’s essential and impactful. Need help making your data clear and impactful? Our data presentation templates can help! Find clear and engaging visuals to showcase your findings.

Lack of structure

Jumping haphazardly between points or topics can confuse your audience. A well-structured presentation, with a logical flow from introduction to conclusion, is crucial for effective communication.

Ignoring the audience

Different audiences have different needs and levels of understanding. Failing to adapt your presentation to your audience can result in a disconnect and a less impactful presentation.

Poor visual elements

While content is king, poor design or lack of visual elements can make your case study dull or hard to follow. Make sure you use high-quality images, graphs and other visual aids to support your narrative.

Not focusing on results

A case study aims to showcase a problem and its solution, but what most people care about are the results. Failing to highlight or adequately explain the outcomes can make your presentation fall flat.

How to start a case study presentation?

Starting a case study presentation effectively involves a few key steps:

- Grab attention : Open with a hook—an intriguing statistic, a provocative question or a compelling visual—to engage your audience from the get-go.

- Set the stage : Briefly introduce the subject, context and relevance of the case study to give your audience an idea of what to expect.

- Outline objectives : Clearly state what the case study aims to achieve. Are you solving a problem, proving a point or showcasing a success?

- Agenda : Give a quick outline of the key sections or topics you’ll cover to help the audience follow along.

- Set expectations : Let your audience know what you want them to take away from the presentation, whether it’s knowledge, inspiration or a call to action.

How to present a case study on PowerPoint and on Google Slides?

Presenting a case study on PowerPoint and Google Slides involves a structured approach for clarity and impact using presentation slides :

- Title slide : Start with a title slide that includes the name of the case study, your name and any relevant institutional affiliations.

- Introduction : Follow with a slide that outlines the problem or situation your case study addresses. Include a hook to engage the audience.

- Objectives : Clearly state the goals of the case study in a dedicated slide.

- Findings : Use charts, graphs and bullet points to present your findings succinctly.

- Analysis : Discuss what the findings mean, drawing on supporting data or secondary research as necessary.

- Conclusion : Summarize key takeaways and results.

- Q&A : End with a slide inviting questions from the audience.

What’s the role of analysis in a case study presentation?

The role of analysis in a case study presentation is to interpret the data and findings, providing context and meaning to them.

It helps your audience understand the implications of the case study, connects the dots between the problem and the solution and may offer recommendations for future action.

Is it important to include real data and results in the presentation?

Yes, including real data and results in a case study presentation is crucial to show experience, credibility and impact. Authentic data lends weight to your findings and conclusions, enabling the audience to trust your analysis and take your recommendations more seriously

How do I conclude a case study presentation effectively?

To conclude a case study presentation effectively, summarize the key findings, insights and recommendations in a clear and concise manner.

End with a strong call-to-action or a thought-provoking question to leave a lasting impression on your audience.

What’s the best way to showcase data in a case study presentation ?

The best way to showcase data in a case study presentation is through visual aids like charts, graphs and infographics which make complex information easily digestible, engaging and creative.

Don’t just report results, visualize them! This template for example lets you transform your social media case study into a captivating infographic that sparks conversation.

Choose the type of visual that best represents the data you’re showing; for example, use bar charts for comparisons or pie charts for parts of a whole.

Ensure that the visuals are high-quality and clearly labeled, so the audience can quickly grasp the key points.

Keep the design consistent and simple, avoiding clutter or overly complex visuals that could distract from the message.

Choose a template that perfectly suits your case study where you can utilize different visual aids for maximum impact.

Need more inspiration on how to turn numbers into impact with the help of infographics? Our ready-to-use infographic templates take the guesswork out of creating visual impact for your case studies with just a few clicks.

Related: 10+ Case Study Infographic Templates That Convert

Congrats on mastering the art of compelling case study presentations! This guide has equipped you with all the essentials, from structure and nuances to avoiding common pitfalls. You’re ready to impress any audience, whether in the boardroom, the classroom or beyond.

And remember, you’re not alone in this journey. Venngage’s Case Study Creator is your trusty companion, ready to elevate your presentations from ordinary to extraordinary. So, let your confidence shine, leverage your newly acquired skills and prepare to deliver presentations that truly resonate.

Go forth and make a lasting impact!

Discover popular designs

Infographic maker

Brochure maker

White paper online

Newsletter creator

Flyer maker

Timeline maker

Letterhead maker

Mind map maker

Ebook maker

9 Creative Case Study Presentation Examples & Templates

Learn from proven case study presentation examples and best practices how to get creative, stand out, engage your audience, excite action, and drive results.

9 minute read

helped business professionals at:

Short answer

What makes a good case study presentation?

A good case study presentation has an engaging story, a clear structure, real data, visual aids, client testimonials, and a strong call to action. It informs and inspires, making the audience believe they can achieve similar results.

Dull case studies can cost you clients.

A boring case study presentation doesn't just risk putting your audience to sleep—it can actuallyl ead to lost sales and missed opportunities.

When your case study fails to inspire, it's your bottom line that suffers.

Interactive elements are the secret sauce for successful case study presentations.

They not only increase reader engagement by 22% but also lead to a whopping 41% more decks being read fully , proving that the winning deck is not a monologue but a conversation that involves the reader.

Let me show you shape your case studies into compelling narratives that hook your audience and drive revenue.

Let’s go!

How to create a case study presentation that drives results?

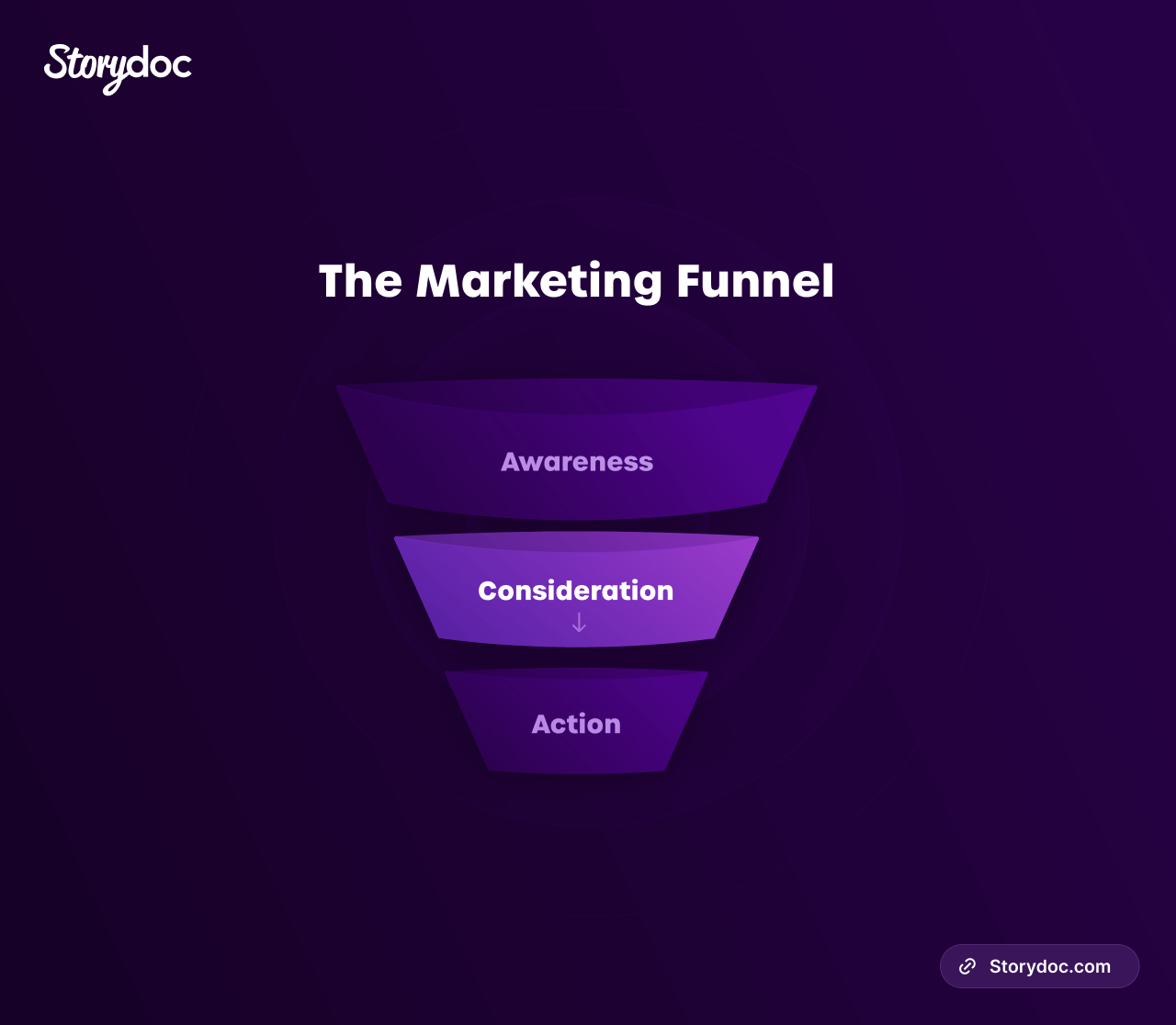

Crafting a case study presentation that truly drives results is about more than just data—it's about storytelling, engagement, and leading your audience down the sales funnel.

Here's how you can do it:

Tell a story: Each case study should follow a narrative arc. Start with the problem, introduce your solution, and showcase the results. Make it compelling and relatable.

Leverage data: Hard numbers build credibility. Use them to highlight your successes and reinforce your points.

Use visuals: Images, infographics, and videos can enhance engagement, making complex information more digestible and memorable.

Add interactive elements: Make your presentation a two-way journey. Tools like tabs and live data calculators can increase time spent on your deck by 22% and the number of full reads by 41% .

Finish with a strong call-to-action: Every good story needs a conclusion. Encourage your audience to take the next step in their buyer journey with a clear, persuasive call-to-action.

Visual representation of what a case study presentation should do:

How to write an engaging case study presentation?

Creating an engaging case study presentation involves strategic storytelling, understanding your audience, and sparking action.

In this guide, I'll cover the essentials to help you write a compelling narrative that drives results.

What is the best format for a business case study presentation?

4 best format types for a business case study presentation:

- Problem-solution case study

- Before-and-after case study

- Success story case study

- Interview style case study

Each style has unique strengths, so pick one that aligns best with your story and audience. For a deeper dive into these formats, check out our detailed blog post on case study format types .

What to include in a case study presentation?

An effective case study presentation contains 7 key elements:

- Introduction

- Company overview

- The problem/challenge

- Your solution

- Customer quotes/testimonials

To learn more about what should go in each of these sections, check out our post on what is a case study .

How to motivate readers to take action?

Based on BJ Fogg's behavior model , successful motivation involves 3 components:

This is all about highlighting the benefits. Paint a vivid picture of the transformative results achieved using your solution.

Use compelling data and emotive testimonials to amplify the desire for similar outcomes, therefore boosting your audience's motivation.

This refers to making the desired action easy to perform. Show how straightforward it is to implement your solution.

Use clear language, break down complex ideas, and reinforce the message that success is not just possible, but also readily achievable with your offering.

This is your powerful call-to-action (CTA), the spark that nudges your audience to take the next step. Ensure your CTA is clear, direct, and tied into the compelling narrative you've built.

It should leave your audience with no doubt about what to do next and why they should do it.

Here’s how you can do it with Storydoc:

How to adapt your presentation for your specific audience?

Every audience is different, and a successful case study presentation speaks directly to its audience's needs, concerns, and desires.

Understanding your audience is crucial. This involves researching their pain points, their industry jargon, their ambitions, and their fears.

Then, tailor your presentation accordingly. Highlight how your solution addresses their specific problems. Use language and examples they're familiar with. Show them how your product or service can help them reach their goals.

A case study presentation that's tailor-made for its audience is not just a presentation—it's a conversation that resonates, engages, and convinces.

How to design a great case study presentation?

A powerful case study presentation is not only about the story you weave—it's about the visual journey you create.

Let's navigate through the design strategies that can transform your case study presentation into a gripping narrative.

Add interactive elements

Static design has long been the traditional route for case study presentations—linear, unchanging, a one-size-fits-all solution.

However, this has been a losing approach for a while now. Static content is killing engagement, but interactive design will bring it back to life.

It invites your audience into an evolving, immersive experience, transforming them from passive onlookers into active participants.

Which of these presentations would you prefer to read?

Use narrated content design (scrollytelling)

Scrollytelling combines the best of scrolling and storytelling. This innovative approach offers an interactive narrated journey controlled with a simple scroll.

It lets you break down complex content into manageable chunks and empowers your audience to control their reading pace.

To make this content experience available to everyone, our founder, Itai Amoza, collaborated with visualization scientist Prof. Steven Franconeri to incorporate scrollytelling into Storydoc.

This collaboration led to specialized storytelling slides that simplify content and enhance engagement (which you can find and use in Storydoc).

Here’s an example of Storydoc scrollytelling:

Bring your case study to life with multimedia

Multimedia brings a dynamic dimension to your presentation. Video testimonials lend authenticity and human connection. Podcast interviews add depth and diversity, while live graphs offer a visually captivating way to represent data.

Each media type contributes to a richer, more immersive narrative that keeps your audience engaged from beginning to end. You can upload your own interactive elements or check stock image sites like Shutterstock, Adobe Stock, iStock, and many more. For example, Icons8, one of the largest hubs for icons, illustrations, and photos, offers both static and animated options for almost all its graphics, whether you need profile icons to represent different user personas or data report illustrations to show your findings.

Prioritize mobile-friendly design

In an increasingly mobile world, design must adapt. Avoid traditional, non-responsive formats like PPT, PDF, and Word.

Opt for a mobile-optimized design that guarantees your presentation is always at its best, regardless of the device.

As a significant chunk of case studies are opened on mobile, this ensures wider accessibility and improved user experience , demonstrating respect for your audience's viewing preferences.

Here’s what a traditional static presentation looks like as opposed to a responsive deck:

Streamline the design process

Creating a case study presentation usually involves wrestling with an AI website builder .

It's a dance that often needs several partners - designers to make it look good, developers to make it work smoothly, and plenty of time to bring it all together.

Building, changing, and personalizing your case study can feel like you're climbing a mountain when all you need is to cross a hill.

By switching to Storydoc’s interactive case study creator , you won’t need a tech guru or a design whizz, just your own creativity.

You’ll be able to create a customized, interactive presentation for tailored use in sales prospecting or wherever you need it without the headache of mobilizing your entire team.

Storydoc will automatically adjust any change to your presentation layout, so you can’t break the design even if you tried.

Case study presentation examples that engage readers

Let’s take a deep dive into some standout case studies.

These examples go beyond just sharing information – they're all about captivating and inspiring readers. So, let’s jump in and uncover the secret behind what makes them so effective.

What makes this deck great:

- A video on the cover slide will cause 32% more people to interact with your case study .

- The running numbers slide allows you to present the key results your solution delivered in an easily digestible way.

- The ability to include 2 smart CTAs gives readers the choice between learning more about your solution and booking a meeting with you directly.

Light mode case study

- The ‘read more’ button is perfect if you want to present a longer case without overloading readers with walls of text.

- The timeline slide lets you present your solution in the form of a compelling narrative.

- A combination of text-based and visual slides allows you to add context to the main insights.

Marketing case study

- Tiered slides are perfect for presenting multiple features of your solution, particularly if they’re relevant to several use cases.

- Easily customizable slides allow you to personalize your case study to specific prospects’ needs and pain points.

- The ability to embed videos makes it possible to show your solution in action instead of trying to describe it purely with words.

UX case study

- Various data visualization components let you present hard data in a way that’s easier to understand and follow.

- The option to hide text under a 'Read more' button is great if you want to include research findings or present a longer case study.

- Content segmented using tabs , which is perfect if you want to describe different user research methodologies without overwhelming your audience.

Business case study

- Library of data visualization elements to choose from comes in handy for more data-heavy case studies.

- Ready-to-use graphics and images which can easily be replaced using our AI assistant or your own files.

- Information on the average reading time in the cover reduces bounce rate by 24% .

Modern case study

- Dynamic variables let you personalize your deck at scale in just a few clicks.

- Logo placeholder that can easily be replaced with your prospect's logo for an added personal touch.

- Several text placeholders that can be tweaked to perfection with the help of our AI assistant to truly drive your message home.

Real estate case study

- Plenty of image placeholders that can be easily edited in a couple of clicks to let you show photos of your most important listings.

- Data visualization components can be used to present real estate comps or the value of your listings for a specific time period.

- Interactive slides guide your readers through a captivating storyline, which is key in a highly-visual industry like real estate .

Medical case study

- Image and video placeholders are perfect for presenting your solution without relying on complex medical terminology.

- The ability to hide text under an accordion allows you to include research or clinical trial findings without overwhelming prospects with too much information.

- Clean interactive design stands out in a sea of old-school medical case studies, making your deck more memorable for prospective clients.

Dark mode case study

- The timeline slide is ideal for guiding readers through an attention-grabbing storyline or explaining complex processes.

- Dynamic layout with multiple image and video placeholders that can be replaced in a few clicks to best reflect the nature of your business.

- Testimonial slides that can easily be customized with quotes by your past customers to legitimize your solution in the eyes of prospects.

Grab a case study presentation template

Creating an effective case study presentation is not just about gathering data and organizing it in a document. You need to weave a narrative, create an impact, and most importantly, engage your reader.

So, why start from zero when interactive case study templates can take you halfway up?

Instead of wrestling with words and designs, pick a template that best suits your needs, and watch your data transform into an engaging and inspiring story.

Hi, I'm Dominika, Content Specialist at Storydoc. As a creative professional with experience in fashion, I'm here to show you how to amplify your brand message through the power of storytelling and eye-catching visuals.

Found this post useful?

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Get notified as more awesome content goes live.

(No spam, no ads, opt-out whenever)

You've just joined an elite group of people that make the top performing 1% of sales and marketing collateral.

Create your best pitch deck to date.

Stop losing opportunities to ineffective presentations. Your new amazing deck is one click away!

10-Step Guide To Crafting A Successful Case Study Presentation

- By Judhajit Sen

- May 2, 2024

Key Takeaways

- An effective case study is a blueprint for convincing an audience and explaining a solution’s rationale and potential impact.

- The ideal time for a business case study is when you have to make your presentation to persuade clients, solve internal problems, back up arguments with real examples, or discuss an idea’s viability for a firm.

- Case study template presentations aren’t just about presenting solutions; they’re powerful storytelling tools that engage audiences with real-world examples and provoke critical thinking.

- Key elements of an effective case study presentation template include an executive summary, problem statement, solution, execution details, key results, inclusion of quotes and testimonials, acknowledgment of contributors, call to action, conclusion, and Q&A session.

A case study is like your argument’s blueprint, explaining the why, how, where, and who to persuade your audience. It’s your solution to a clear question, like expanding in a market or launching a product. Case studies help convince clients, analyze internal issues, and provide real-life use cases.

So, when should you make your case study like a pro? When you need to:

– Persuade clients about your services.

– Solve internal problems for a company.

– Back up arguments with real examples.

– Discuss an idea’s viability for a firm.

It’s not just about finding a solution—it’s about influencing your audience with your findings. Case study formats organize a lot of information in a clear, engaging way for clients and stakeholders, often using templates.

In simpler terms, a professional case study is an in-depth look at a specific topic, often tackling real-world problems. It showcases your expertise and how your solutions can solve actual issues.

In social sciences, it’s both a method and a research design to examine problems and generalize findings. Essentially, it’s investigative research aimed at presenting solutions to analyzed issues.

In business, case study examples delve into market conditions, main problems, methods used, and outcomes gained. It’s a powerful tool for understanding and addressing complex business challenges.

Case Study Presentation

Good case study PowerPoint templates explore a specific subject, whether it’s an individual, group, event, or organization. It’s like solving a puzzle with your audience, pushing you to think creatively.

Unlike a standard report, the goal here is to stimulate critical thinking. You’re not just throwing numbers around; you’re using real-life examples to provoke thought and offer different perspectives.

In marketing, case studies showcase your solutions’ effectiveness and success in solving client problems. These research presentations use written content, visuals, and other tools to tell compelling stories. They’re perfect for sales pitches, trade shows, conferences, and more—whether in-person or virtual.

But the best case study presentation slides aren’t just reports; they’re powerful and persuasive storytelling tools. Whether you’re a marketer or salesperson, knowing how to present a case study can be a game-changer for your business. It’s all about engaging your audience and sharing insights in a clear and compelling way.

Looking to make a compelling presentation? Check out our blog on persuasive presentations.

Importance of a Case Study Presentation

To write a compelling case study presentation is more than just sharing information—it’s about convincing your audience that your product or service is the solution they need. Case study presentations help in –

Generating leads and driving sales: Case studies showcase your product’s success, turning potential customers into paying clients.

Building credibility and social proof: They establish your authority and value through real-life examples, earning trust from clients and prospects.

Educating and informing your target audience: Case studies teach potential clients about your product’s benefits, positioning you as an industry leader.

Increasing brand awareness: Case studies promote your brand, boost your visibility, and attract new customers.

Stats back up the power of case studies:

– 13% of marketers rely on them in their content strategy.

– They help boost conversions by 23% and nurture leads by 9%.

– 80% of tech content marketers include case studies in their strategy.

But case studies aren’t just marketing fluff; they’re about solving problems and showcasing accurate results. They’re valuable in various scenarios, from business cases to analyzing internal issues.

To create a compelling case study presentation effectively is your chance to offer a comprehensive, evidence-based argument that informs and persuades your audience. It’s like solving a puzzle, exploring every piece until you reach a clear conclusion. It’s about connecting data with real-world scenarios in a compelling narrative.

Whether in sales pitches, job interviews, or content marketing, case study presentation examples are your secret weapon for success. They provide tangible proof of your product’s value, helping you stand out in a cluttered marketplace.

Following are ten essential steps to crafting a successful case study presentation.

Begin With The Executive Summary

Leaders often seek a quick snapshot of important information, and that’s where the executive summary plays a vital role. Begin with a short introduction, laying out the purpose and goals of the case study in a straightforward manner. Capture your audience’s attention and provide a clear path for what follows.

Follow the introduction with a brief of the entire case study, allowing the audience to grasp the main points swiftly. Delve into the subject’s relevance and significance, explaining why the case study is essential and who benefits from its insights. This establishes the tone for the rest of the study, encouraging the audience to explore further.

Check out our expert tips and techniques to master creating an executive summary for presentations.

Define the Problem Statement

Focus on the problem or challenge central to the case study. Provide background for the audience to grasp the issue, backing it up with data, graph or metrics to highlight its seriousness.

Need help visualizing your data? Check out our guide on mastering data visualizations.

Outline the goals and purpose of the case study and the questions it seeks to answer. This entails outlining the main issues from the customer’s viewpoint, making it understandable to the audience.

Start with a brief recap of the problem, clarifying the purpose of the study and the expected audience learnings. Explain the situation, shedding light on the hurdles faced. Present the key issues and findings without delving into specific details.

Highlight the importance of the problem using data and evidence to emphasize its real-world impact. Encapsulate the analysis’s purpose, aligning the issues identified with the study’s objectives.

Propose The Solution

At the heart of a presentation lies its solution. Reveal the steps taken to address the identified problem, including the methodology, experiments, or tests carried out and the considerations of various options. Clarify why the final solution was chosen over others.

Illustrates the shift from the problem-filled “before” to the successful “after.”

Detail the proposed solution, recommendations, or action plan based on analyses. This includes explaining its reasoning and outlining implementation steps, timelines, and potential challenges.

Describe the analytical methods and approach used, demonstrating the thoroughness of the analysis, including research processes, data collection tools, and frameworks employed.

Present the essential findings and insights, utilizing data, charts, and visuals to enhance comprehension and engagement. Thoroughly discuss the analyses and the implications of the findings.

Show How the Solution was Executed

The execution slide of a case study presentation describes careful planning, consideration of risks, and measurement of metrics crucial for implementing the solution.

Delve into the steps taken to attain desired client results, including identifying project key performance indicators (KPIs), addressing issues, and implementing risk mitigation strategies.

Detail the journey towards helping the client achieve results. Outline the planning, processes, risks, metrics, and KPIs essential for maximizing outcomes. This includes discussing any challenges encountered during execution and the strategies to overcome them, ensuring a seamless implementation process.

Highlight the practical steps taken to turn the proposed solution into tangible results for the client.

Present the Key Results

Cover the outcomes achieved through the implementation of the solution. Leverage data and metrics to evaluate whether the solution successfully met its objectives and the extent of its impact on stakeholders. Acknowledge any setbacks or areas for improvement.

Outline the solution’s positive impact on the client’s project or business, highlighting aspects such as financial results, growth, and productivity enhancements. Reinforce these assertions with supporting evidence, including images, videos, and statistical data.

Emphasize the remarkable outcomes resulting from the solution, substantiating tangible success with relevant data and metrics. Illustrate the effectiveness of your recommendations through before-and-after comparisons and success metrics, highlighting their real-world impact.

This solidifies the rationale behind your proposal, showcasing its substantial impact on the business or project, particularly in terms of financial benefits for clients.

Include Quotes and Testimonials

Incorporate quotes and testimonials directly from customers who have experienced the transformation firsthand, adding authenticity and credibility to your case study. These voices of customers (VoC) provide firsthand accounts of the benefits and effectiveness of your solution, offering extra social proof to support your claims.

To gather compelling testimonials, plan and schedule interviews with your subjects. Design case study interview questions that allow you to obtain quantifiable results to capture valuable insights into the customer experience and the impact of your solution.

Include testimonials from satisfied customers to bolster the credibility of your case study and provide potential clients with real-life examples of success. These quotes serve as powerful endorsements of your offerings, helping to build trust and confidence among your target audience.

Acknowledge your Contributors with References and Citations

Express gratitude to those who played a vital role in shaping your case study’s outcomes. Extend heartfelt thanks to individuals whose insights and collaboration were essential in problem-solving.

Acknowledges the valuable contributions of external resources, reports, and data sets. Citing these sources maintains transparency and credibility, ensuring due credit is given and providing a solid foundation for further investigation.

Incorporate a comprehensive list of references, citations, and supplementary materials in the appendices supporting the case study’s findings and conclusions. These additional resources demonstrate the thoroughness of the research and offer interested parties the opportunity to delve deeper into the topic.

Thank those who contributed, and encourage the audience to explore the provided references to better understand the insights presented in the case study.

Give a Call to Action (CTA)

As the well-crafted case study presentation slides near their end, it’s crucial to outline actionable steps for stakeholders going forward. Recommend the following strategies to the audience to build upon the success achieved.

Ask stakeholders to integrate the proven solutions highlighted in the case study into existing processes or projects. These strategies have shown effectiveness and can be valuable tools in driving further success.

Encourage audience members to participate in a detailed consultation or product demonstration. Leveraging expertise and solutions can expedite goal achievement and overcome any remaining challenges.

Recommend further research and analysis to explore additional opportunities for improvement or innovation. Continuous learning and adaptation are essential in today’s dynamic business environment, with support available every step of the way.

Proactive steps based on insights from the case study will position organizations for continued growth and success. Urge the stakeholders to take action and seize the opportunities ahead.

Check out our blog on framing an effective call to action to learn more about crafting presentation CTAs.

Conclude your Case Study Presentation

Conclude the presentation by recapping the main points and highlighting their importance. Show that the solution presented effectively tackled the identified problem, delivering concrete results and benefits for the clients.

Summarize the key takeaways, underscoring how the findings can be applied in similar situations and showcasing the solution’s relevance across various contexts. This demonstrates not only its effectiveness but also its potential to yield positive outcomes in diverse scenarios.

Reiterate the power of strategic problem-solving and innovative solutions in driving success, and end by thanking the audience for their attention and participation.

To know more about concluding a presentation, check out our blog on helpful tips to end a presentation successfully.

Open the Floor for Q&A, Feedback and Discussion

After your presentation ends, conduct a Q&A session. Encourage the audience to share their thoughts, ask questions for clarification, and engage in a constructive dialogue about the case study presented.

Feedback is valuable, so ask everyone to share their perspectives and insights. Also, encourage questions or comments, as they can provide further depth to the understanding of the subject matter.

This is an opportunity for mutual learning and exploring different viewpoints. Urge everyone to speak up and contribute to the conversation. The aim is to listen and exchange ideas to enrich the understanding of the topic.

Unlocking Success: Mastering the Art of Case Study Presentations

Case study presentations are not just reports; they’re dynamic storytelling tools that help sway clients, dissect internal issues, and provide real-world illustrations.

These presentations aren’t just about offering solutions; they’re about influencing audiences with findings. Organizing vast amounts of data in an engaging way, often using templates and case studies, provides a clear path for clients and stakeholders.

Case study presentations delve deep into subjects, pushing presenters to think creatively. Unlike standard reports, they aim to provoke thought and offer varied perspectives. They’re powerful tools for showcasing success in solving client problems and using written content, visuals, and other elements to tell compelling stories.

Mastering case study presentations can be a game-changer, whether you’re a marketer, salesperson, or educator. It’s about engaging your audience and clearly and persuasively sharing insights into success stories.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. When should I consider doing a case study?

Case studies are beneficial when you need to persuade clients about your services, solve internal problems for a company, back up arguments with real examples, or discuss the viability of an idea for a firm.

2. What is the primary purpose of a case study presentation?

The primary goal of a case study presentation is to offer a comprehensive and evidence-based argument that informs and persuades the audience. It’s about presenting solutions to analyzed issues in a compelling narrative format.

3. What makes a case study presentation different from a standard report?

Unlike a standard report, a case study presentation aims to stimulate critical thinking by using real-life examples to provoke thought and offer different perspectives. It’s not just about presenting data; it’s about engaging the audience with compelling stories.

4. Where can case study presentations be effectively used?

Case study presentations are perfect for sales pitches, trade shows, conferences, and more—whether in-person or virtual. They are valuable storytelling tools that showcase the effectiveness of solutions and success in solving client problems.

Transform Your Business with Prezentium’s Case Study Presentations

Are you looking to captivate your prospective clients with compelling case study presentations? Look no further than Prezentium ! Prezentium, an AI-powered business presentation service provider, offers various services tailored to your needs.

Overnight Presentations : Need a professional presentation in a pinch? Our overnight presentation service has you covered. Email your requirements to Prezentium by 5:30 pm Pacific Standard Time (PST), and we’ll deliver a top-notch presentation to your inbox by 9:30 am PST the following business day.

Prezentation Specialist : Our team is here to help you transform ideas and meeting notes into exquisite presentations. Whether you need assistance with case study design, templates, or content creation, we’ve got you covered.

Zenith Learning : Elevate your communication skills with our interactive workshops and training programs. Combining structured problem-solving with visual storytelling, Zenith Learning equips you with the tools you need to succeed.

Unlock the power of case study presentations with Prezentium. Contact us today to learn more and take your business to new heights!

Why wait? Avail a complimentary 1-on-1 session with our presentation expert. See how other enterprise leaders are creating impactful presentations with us.

Passive Aggressive Communication: Passive-aggressive Behavior Insights

10 tips to make a good maid of honor speech, presentation to the board of directors: 14 board presentation tips.

Free PowerPoint Case Study Presentation Templates

By Joe Weller | January 23, 2024

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Link copied

We’ve collected the top free PowerPoint case study presentation templates with or without sample text. Marketing and product managers, sales execs, and strategists can use them to arrange and present their success stories, strategies, and results.

On this page, you'll find six PowerPoint case study presentation templates, including a marketing case study template , a problem-solution-impact case study , and a customer journey case study template , among others. Plus, discover the key components of successful case study presentations , find out the different types of case study presentations , and get expert tips .

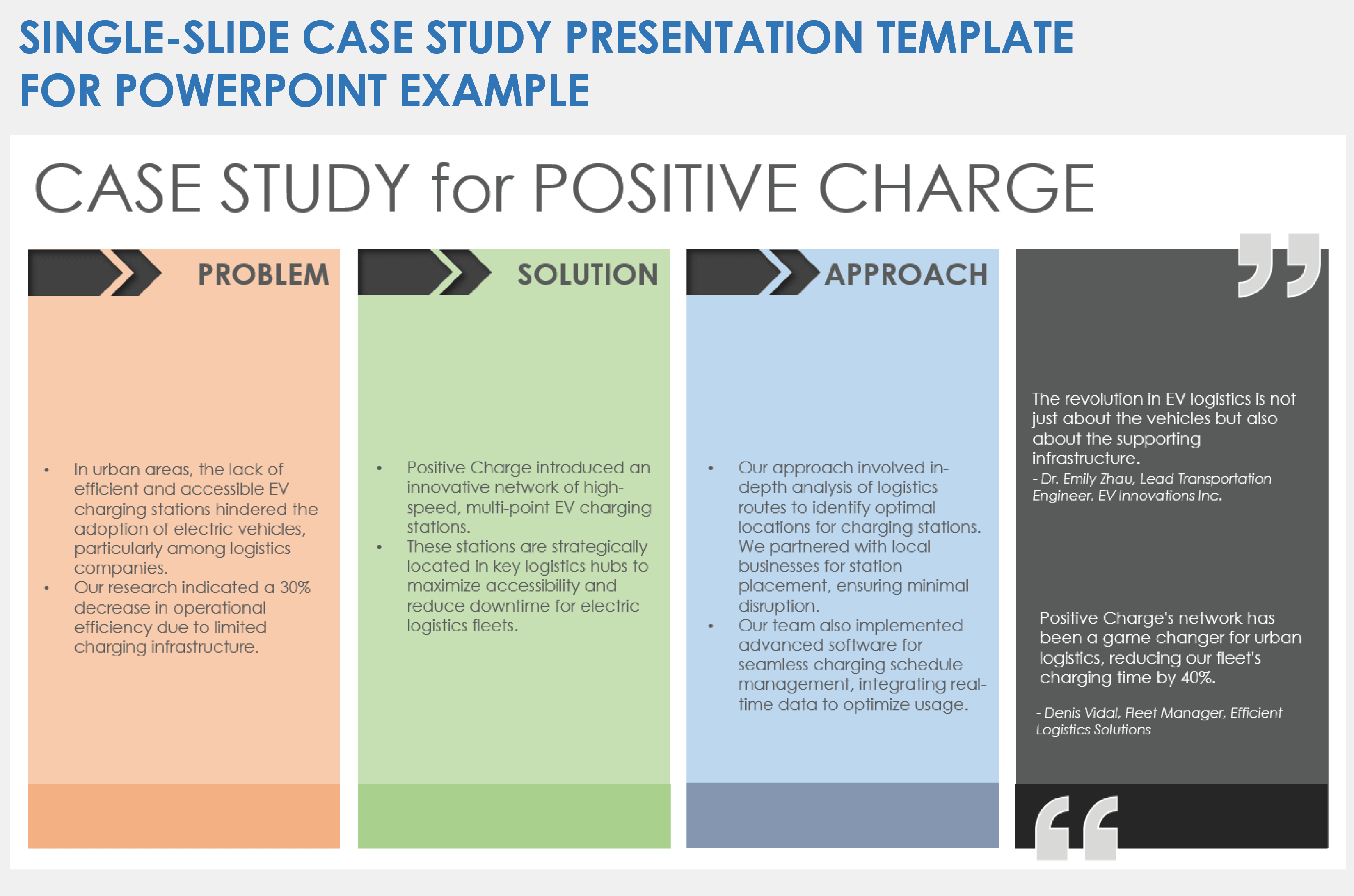

PowerPoint Single-Slide Case Study Presentation Template

Download the Sample Single-Slide Case Study Presentation Template for PowerPoint Download the Blank Single-Slide Case Study Presentation Template for PowerPoint

When to Use This Template: Use this single-slide case study presentation template when you need to give a quick but effective overview of a case study. This template is perfect for presenting a case study when time is limited and you need to convey key points swiftly.

Notable Template Features: You can fit everything you need on one slide. Download the version with sample text to see how easy it is to complete the template. Unlike more detailed templates, it focuses on the main points, such as the problem, solution, approach, and results, all in a compact format. It's great for keeping your audience focused on the key aspects of your case study without overwhelming them with information.

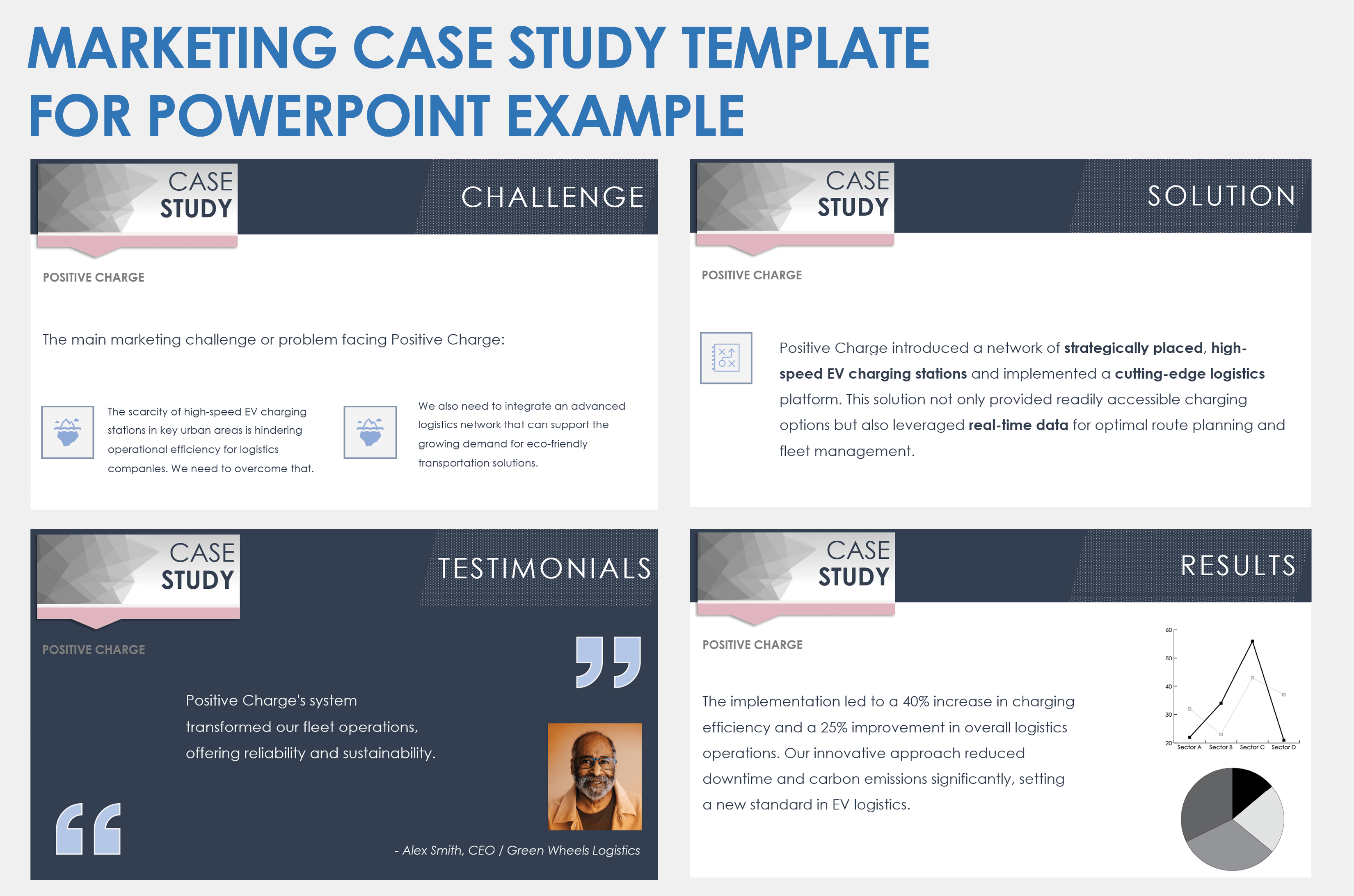

PowerPoint Marketing Case Study Template

Download the Sample Marketing Case Study Template for PowerPoint

Download the Blank Marketing Case Study Template for PowerPoint

When to Use This Template: Choose this marketing case study template when you need to dive deep into your marketing strategies and results. It's perfect for marketing managers and content marketers who want to showcase the detailed process and successes of their campaigns.

Notable Template Features: This template focuses on the detailed aspects of marketing strategies and outcomes. It includes specific sections to outline business needs, results, and strategic approaches.

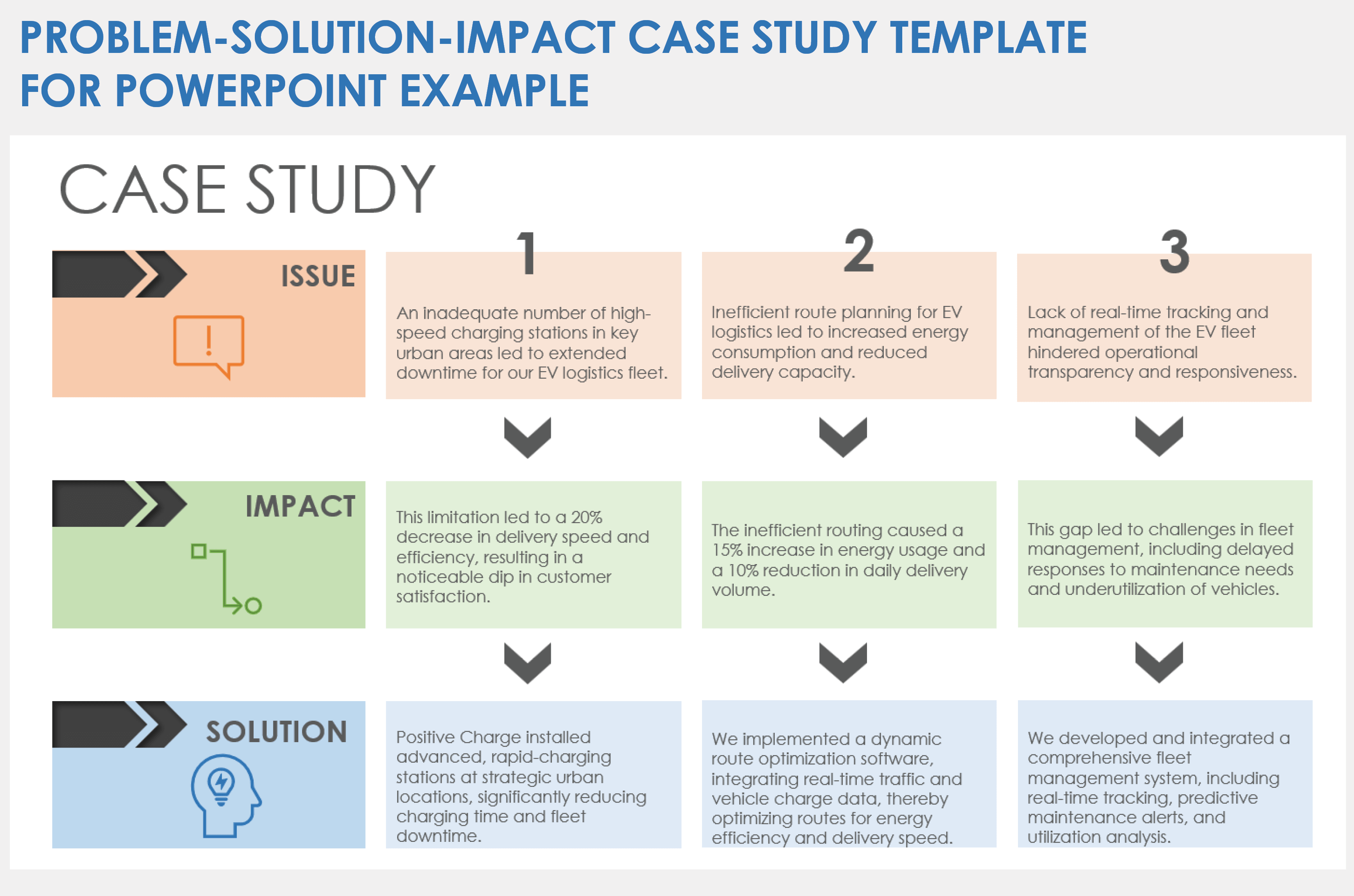

PowerPoint Problem-Solution-Impact Case Study Template

Download the Sample Problem-Solution-Impact Case Study Template for PowerPoint

Download the Blank Problem-Solution-Impact Case Study Template for PowerPoint

When to Use This Template: This problem-solution-impact case study template is useful for focusing on how a challenge was solved and the results. Project managers and strategy teams that want to clearly portray the effectiveness of their solutions can take advantage of this template.

Notable Template Features: This template stands out with its clear structure that breaks down the case into problem, solution, and impact. Use the template — available with or without sample data — to help you tell a complete story, from the issue faced to the solution and its results, making it perfect for presentations that need to show a clear cause-and-effect relationship.

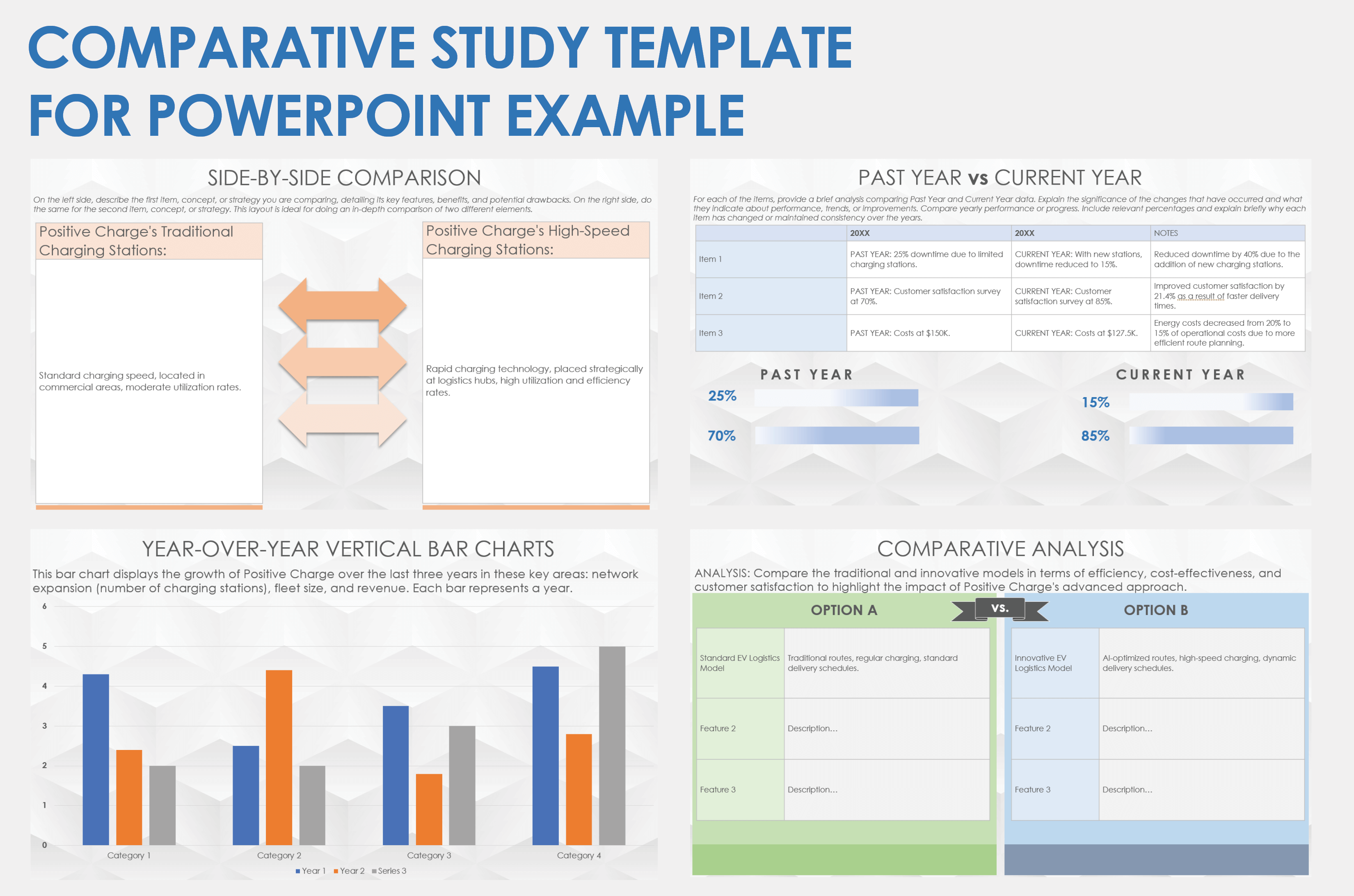

PowerPoint Comparative Study Template

Download the Sample Comparative Study Template for PowerPoint

Download the Blank Comparative Study Template for PowerPoint

When to Use This Template: Choose this comparative study template — available with or without sample data — to illuminate how different products, strategies, or periods stack up against each other. It's great for product managers and research teams who want to do side-by-side comparisons.

Notable Template Features: This template lets you put things next to each other to see their differences and similarities, with a focus on direct comparisons. Use the columns and split slides to make the content easy to understand and visually appealing, perfect for highlighting changes or different approaches.

PowerPoint Customer Journey Case Study Template

Download the Sample Customer Journey Case Study Template for PowerPoint

Download the Blank Customer Journey Case Study Template for PowerPoint

When to Use This Template: This template is useful for customer experience managers and UX designers who need to understand and improve how customers interact with what they offer. Use the customer journey case study template with sample data to see how to show every step of a customer's experience with your product or service.

Notable Template Features: This template focuses on the whole path a customer takes with a product or service. It follows them, from first learning about the offering to after they buy it.

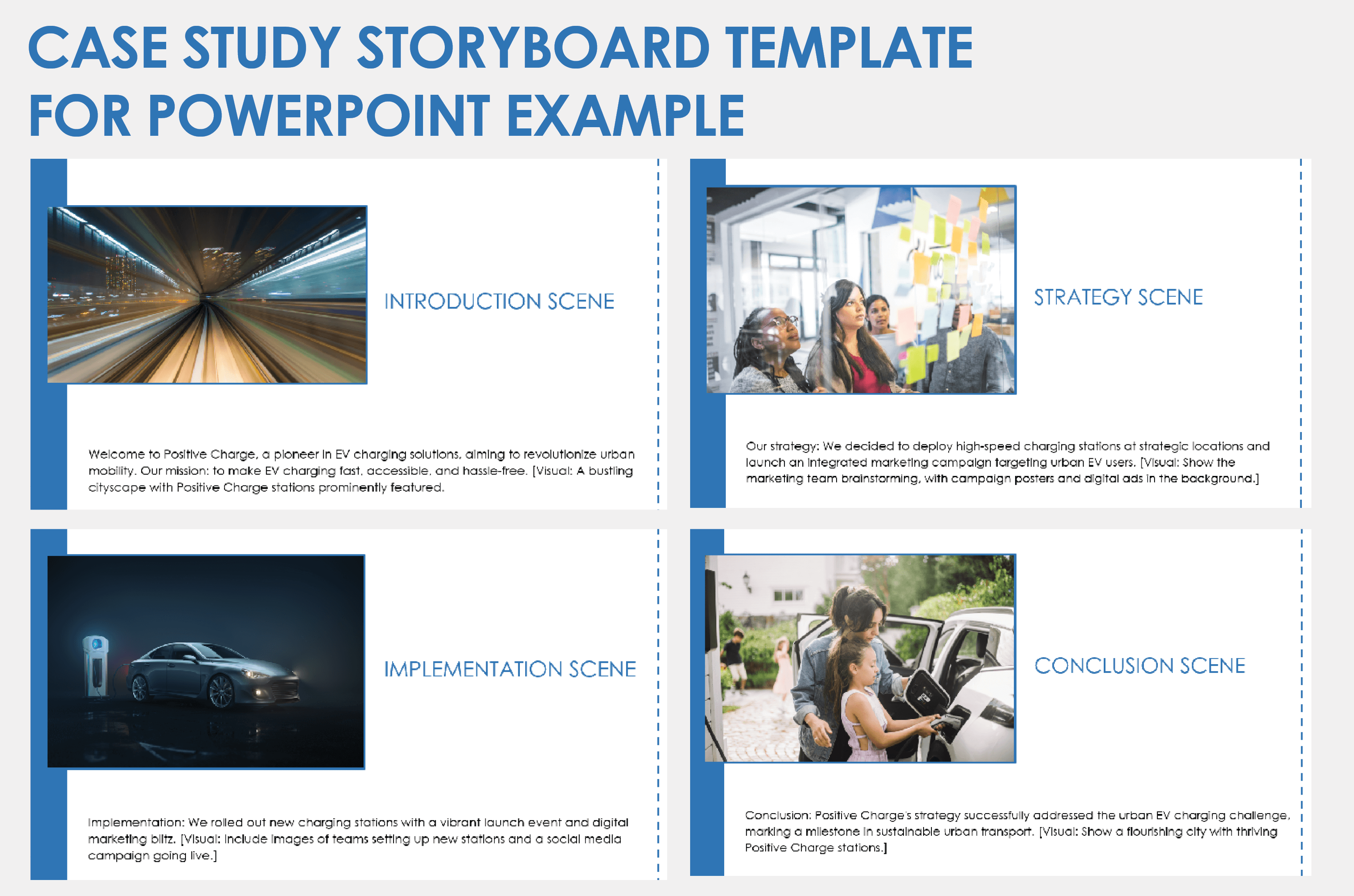

PowerPoint Case Study Storyboard Template

Download the Sample Case Study Storyboard Template for PowerPoint Download the Blank Case Study Storyboard Template for PowerPoint

When to Use This Template: Creative teams and ad agencies should use this case study storyboard template — with or without sample data — to tell a story using more images than text.

Notable Template Features: This template transforms a case study into a visual story. Effectively communicate the journey of a business case, from the challenges faced to the solutions implemented and the results achieved.

Key Components of Successful Case Study Presentations

The key components of successful case study presentations include clear goals, engaging introductions, detailed customer profiles, and well-explained solutions and results. Together they help you present how your strategies succeed in real-world scenarios.

The following components are fundamental to crafting a compelling and effective marketing case study presentation:

- Clear Objective: Define the goal of your case study, ensuring it addresses specific questions or goals.

- Engaging Introduction: Start with an overview of the company, product, or service, as well as the context to provide necessary background information.

- Customer Profile: Detail your target customer demographics and their needs to help the audience understand who the marketing efforts are aimed at and their relevance.

- The Challenge: Clearly articulate the primary problem or issue to overcome to establish the context for the solution and strategy, highlighting the need for action.

- Solution and Strategy: Describe the specific strategies and creative approaches used to address the challenge. These details should demonstrate your approach to problem-solving and the thought process behind your decisions.

- Implementation: Explain how the solution was put into action to show the practical application. This description should bring your strategy to life, allowing the audience to see how you executed plans.

- Results and Impact: Present measurable outcomes and impacts of the strategy to validate and show its effectiveness in real-world scenarios.

- Visual Elements: Use charts, images, and infographics to make complex information more accessible and engaging, aiding audience understanding.

- Testimonials and Quotes: Include customer feedback or expert opinions to add credibility and a real-world perspective, reinforcing your strategy’s success.

- Lessons Learned and Conclusions: Summarize key takeaways and insights gained to show what the audience can learn from the case study.

- Call to Action (CTA): End with an action you want the audience to take to encourage engagement and further interaction.

Different Types of Case Study Presentations

The types of case study presentations include those that compare products, showcase customer journeys, or tell a story visually, among others. Each is tailored to different storytelling methods and presentation goals.

The following list outlines various types of case study presentations:

- Problem-Solution-Impact Case Study: This type focuses on a clear narrative structure, outlining the problem, solution implemented, and final impact. It's straightforward and effective for linear stories.

- Comparative Case Study: Ideal for showcasing before-and-after scenarios or comparisons between different strategies or time periods. This option often uses parallel columns or split slides for comparison.

- Customer Journey Case Study: Centered on the customer's experience, this option maps out their journey from recognizing a need to using the product or service, and the benefits they gained. It's a narrative-driven and customer-focused case study format.

- Data-Driven Case Study: Emphasizing quantitative results and data, this format is full of charts, graphs, and statistics. This option is perfect for cases where numerical evidence is the main selling point.

- Storyboard Case Study: Use this type to lay out the case study in a storytelling format. This option often relies on more visuals and less text. Think of it as a visual story, engaging and easy to follow.

- Interactive Case Study: Designed with clickable elements for an interactive presentation, this type allows the presenter to dive into different sections based on audience interest, making it flexible and engaging.

- Testimonial-Focused Case Study: This format is best for highlighting customer testimonials and reviews. It leverages the power of word of mouth and is highly effective in building trust.

Expert Tips for Case Study Presentations

Expert tips for case study presentations include knowing your audience, telling a clear story, and focusing on the problem and solution. They can also benefit from using visuals and highlighting results.

“Case studies are one of the most powerful tools in an organization’s marketing arsenal,” says Gayle Kalvert, Founder and CEO of Creo Collective, Inc. , a full-service marketing agency. “Done correctly, case studies provide prospective buyers with proof that your product or service solves their business problem and shortens the sales cycle.”

“Presentations are probably the most powerful marketing asset, whether for a webinar, a first meeting deck, an investor pitch, or an internal alignment/planning tool,” says marketing expert Cari Jaquet . “Remember, the goal of a case study presentation is not just to inform, but also to persuade and engage your audience.”

Use these tips to make your presentation engaging and effective so that it resonates with your audience:

- Know Your Audience: Tailor the presentation to the interests and knowledge level of your audience. Understanding what resonates with them helps make your case study more relevant and engaging. “Presentations can also be a forcing function to define your audience, tighten up your mission and message, and create a crisp call to action,” explains Jaquet.

- Tell a Story: Structure your case study like a story, with a clear beginning (the problem), middle (the solution), and end (the results). A narrative approach keeps the audience engaged.

- Focus on the Problem and Solution: Clearly articulate the problem you addressed and how your solution was unique or effective. This section is the core of a case study and should be given ample attention.

- Use Data Wisely: Incorporate relevant data to support your points, but avoid overwhelming the audience with numbers. Use charts and graphs for visual representation of data to make it more digestible.

- Highlight Key Results: Emphasize the impact of your solution with clear and quantifiable results. This could include increased revenue, cost savings, improved customer satisfaction, and similar benefits.

- Incorporate Visuals: Use high-quality visuals to break up text and explain complex concepts. Consider using photos, infographics, diagrams, or short videos. “I put together the graphics that tell the story visually. Speakers often just need a big image or charts and graphs to help guide their talk track. Of course, if the audience expects details (for example, a board deck), the graphic helps reinforce the narrative,” shares Jaquet.

- Include Testimonials: Adding quotes or testimonials from clients or stakeholders adds credibility and a real-world perspective to your presentation.

- Practice Storytelling: A well-delivered presentation is as important as its content. Practice your delivery to ensure you are clear, concise, and engaging. At this point, it also makes sense to solicit feedback from stakeholders. Jaquet concurs: “Once my outline and graphics are in place, I typically circulate the presentation draft for review. The feedback step usually surfaces nuances in the story or key points that need to show up on the slides. There is no point in building out tons of slides without alignment from the speaker or subject matter experts.”

- End with a Strong Conclusion: Summarize the key takeaways and leave your audience with a final thought or call to action.

- Seek Feedback: After your presentation, request feedback to understand what worked well and what could be improved for future presentations.

“Don't underestimate the power of a great presentation. And don't wait until the last minute or try to invent the wheel on your own,” advises Jaquet. “Many times, getting the next meeting, winning the deal, or getting the project kicked off well, requires your audience to understand and believe your story.”

Streamline and Collect All the Elements Needed for a Case Study with Smartsheet

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.

Discover why over 90% of Fortune 100 companies trust Smartsheet to get work done.

Business Case Study PowerPoint Template

Business Case Study PowerPoint Template is a professional presentation created to describe Business Case Studies.

A Case Study is a research method consisting of a close and detailed examination of a subject of study (a.k.a “the case”) as well as its related contextual conditions. “The Case” studied can be an individual, an organization, an action or even an event taking place in a specific place and time frame.

The Case Method is a teaching approach that uses real scenario cases to situate students in the role of the people (generally top management) who faced the decision making process in the specific timeframe, place and environmental condition. This method has become widespread across Business Schools as the standard learning path for the new generation of managers.

Ideal for MBA Students and Candidates that require simple and quick business PowerPoint Templates to complete their analysis for the Case Study, and present it to the class. It is created with high definition background pictures that represent the business metaphor of each section. Also it uses high quality PowerPoint Icons, to represent business ideas and be able to describe conclusions and findings with high visual impact. Business Consultants and Analysts can take advantage of this case study template to present their overall analysis and findings to the executive board or top management.

The structure of our Business Case Study PowerPoint Template consists of the following sections, each of them created through the Harvard Business School Business Case Study Guidelines.

- Problem and Solution

- Executive Summary

- Brief History

- Business Key Points

- Key Challenges

- Industry Analysis

- Environmental Analysis

- Financial Performance

- Company Analysis

- Key Success Factors

- Alternative Options

- Pros & Cons

- Solution Analysis and Comparison

- Recommendations

This sections will guide each presenter in to the full description of the Case Study Analysis , engaging the audience with powerful visual components.

Every Shape, Icon and Clipart is 100% editable, allowing the user to customize the complete appearance of the presentation, changing size, color, effects, position, etc. Also, every shape can be reused in existing presentations in the case the presentar desires to decorate existing Business Case Analysis with new high quality PowerPoint Shapes.

Impress your audience with our outstanding Business Case Studies PowerPoint Template . Create professional PowerPoint presentations that appeal to Global audiences.

You must be logged in to download this file.

Favorite Add to Collection

Subscribe today and get immediate access to download our PowerPoint templates.

Related PowerPoint Templates

Executive Project Overview PowerPoint Template

7-Item Creative Horizontal Process PowerPoint Template

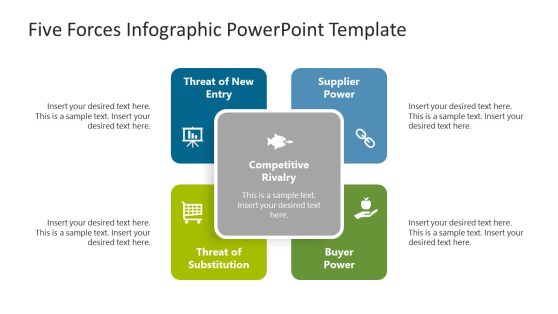

Porter’s Five Forces Model Template for PowerPoint

Business Case Study Presentation Template

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

Case Study Research Method

Published by MargaretMargaret Chambers Modified over 6 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "Case Study Research Method"— Presentation transcript:

Reviewing and Critiquing Research

Research Methodologies

Problem Identification

Introduction to Communication Research

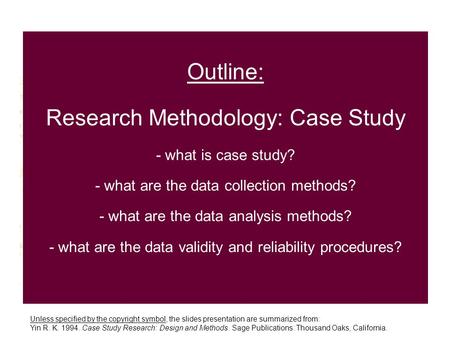

Outline: Research Methodology: Case Study - what is case study

Designing Case Studies. Objectives After this session you will be able to: Describe the purpose of case studies. Plan a systematic approach to case study.

Case Study Research By Kenneth Medley.

Formulating the research design

Case Studies Segments 32,33,34. Case Study Process - Overview.

The Case Study as a Research Method

Chapter 14 Overview of Qualitative Research Gay, Mills, and Airasian

Edwin D. Bell Winston-Salem State University

An Introduction to Research Methodology

Qualitative Research.

What research is Noun: The systematic investigation into and study of materials and sources in order to establish facts and reach new conclusions. Verb:

Chapter 10 Qualitative Methods in Health and Human Performance.

Evaluating a Research Report

Evaluating Research Articles Approach With Skepticism Rebecca L. Fiedler January 16, 2002.

URBDP 591 I Lecture 3: Research Process Objectives What are the major steps in the research process? What is an operational definition of variables? What.

Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.