What’s the difference between climate change and global warming?

The terms “global warming” and “climate change” are sometimes used interchangeably, but "global warming" is only one aspect of climate change.

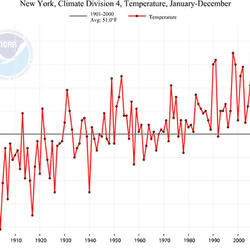

“Global warming” refers to the long-term warming of the planet. Global temperature shows a well-documented rise since the early 20th century and most notably since the late 1970s. Worldwide since 1880, the average surface temperature has risen about 1 ° C (about 2 ° F), relative to the mid-20th century baseline (of 1951-1980). This is on top of about an additional 0.15 ° C of warming from between 1750 and 1880.

“Climate change” encompasses global warming, but refers to the broader range of changes that are happening to our planet. These include rising sea levels; shrinking mountain glaciers; accelerating ice melt in Greenland, Antarctica and the Arctic; and shifts in flower/plant blooming times. These are all consequences of warming, which is caused mainly by people burning fossil fuels and putting out heat-trapping gases into the air.

- Overview: Weather, Global Warming and Climate Change

Discover More Topics From NASA

Explore Earth Science

Earth Science in Action

Earth Science Data

Facts About Earth

What's the difference between global warming and climate change?

Global warming refers only to the Earth’s rising surface temperature, while climate change includes warming and the “side effects” of warming—like melting glaciers, heavier rainstorms, or more frequent drought. Said another way, global warming is one symptom of the much larger problem of human-caused climate change.

Global warming is just one symptom of the much larger problem of climate change. NOAA Climate.gov cartoon by Emily Greenhalgh.

Another distinction between global warming and climate change is that when scientists or public leaders talk about global warming these days, they almost always mean human -caused warming—warming due to the rapid increase in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases from people burning coal, oil, and gas.

Climate change, on the other hand, can mean human-caused changes or natural ones, such as ice ages. Besides burning fossil fuels, humans can cause climate changes by emitting aerosol pollution—the tiny particles that reflect sunlight and cool the climate— into the atmosphere, or by transforming the Earth's landscape, for instance, from carbon-storing forests to farmland.

A climate change unlike any other

The planet has experienced climate change before: the Earth’s average temperature has fluctuated throughout the planet’s 4.54 billion-year history. The planet has experienced long cold periods ("ice ages") and warm periods ("interglacials") on 100,000-year cycles for at least the last million years.

Previous warming episodes were triggered by small increases in how much sunlight reached Earth’s surface and then amplified by large releases of carbon dioxide from the oceans as they warmed (like the fizz escaping from a warm soda).

Increases and decreases in global temperature during the naturally occurring ice ages of the past 800,000 years, ending with the early twentieth century. NOAA Climate.gov graph by Fiona Martin, based on EPICA Dome C ice core data provided by the Paleoclimatology Program at NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information.

Today’s global warming is overwhelmingly due to the increase in heat-trapping gases that humans are adding to the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels. In fact, over the last five decades, natural factors (solar forcing and volcanoes) would actually have led to a slight cooling of Earth’s surface temperature.

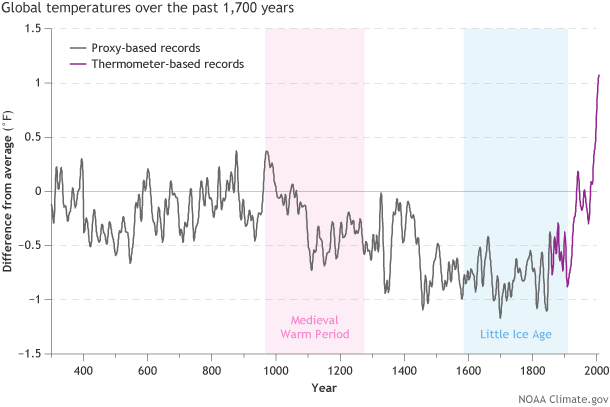

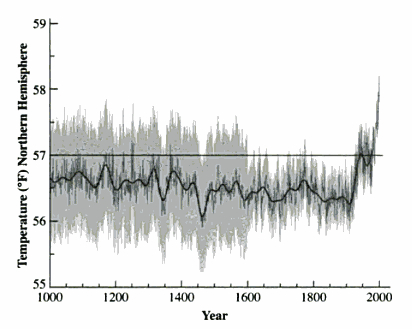

Global warming is also different from past warming in its rate. The current increase in global average temperature appears to be occurring much faster than at any point since modern civilization and agriculture developed in the past 11,000 years or so—and probably faster than any interglacial warm periods over the last million years.

Temperatures over most of the past 2000 years compared to the 1961-1990 average, based on proxy data (tree rings, ice cores, corals) and modern thermometer-based data. Over the past two millenia, climate warmed and cooled, but no previous warming episodes appear to have been as large and abrupt as recent global warming. NOAA Climate.gov graph by Fiona Martin, adapted from Figure 34.5 in the National Climate Assessment, based on data from Mann et al., 2008.

New understanding required new terms

Regardless of whether you say that climate change is all the side effects of global warming, or that global warming is one symptom of human-caused climate change, you’re essentially talking about the same basic phenomenon: the build up of excess heat energy in the Earth system. So why do we have two ways of describing what is basically the same thing?

According to historian Spencer Weart , the use of more than one term to describe different aspects of the same phenomenon tracks the progress of scientists’ understanding of the problem.

As far back as the late 1800s, scientists were hypothesizing that industrialization, driven by the burning of fossil fuels for energy, had the potential to modify the climate. For many decades, though, they weren’t sure whether cooling (due to reflection of sunlight from pollution) or warming (due to greenhouse gases) would dominate.

By the mid-1970s, however, more and more evidence suggested warming would dominate and that it would be unlike any previous, naturally triggered warming episode. The phrase “global warming” emerged to describe that scientific consensus.

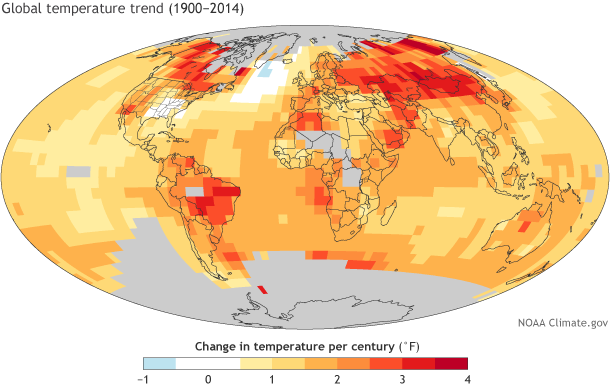

Change in temperature (degrees per century) from 1900-2014. Gray areas indicate where there is insufficient data to detect a long-term trend. NOAA Climate.gov map, based on NOAAGlobalTemp data from NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information.

But over subsequent decades, scientists became more aware that global warming was not the only impact of excess heat absorbed by greenhouse gases. Other changes—sea level rise, intensification of the water cycle, stress on plants and animals—were likely to be far more important to our daily lives and economies. By the 1990s, scientists increasingly used “human-caused climate change” to describe the challenge facing the planet.

The bottom line

Today’s global warming is an unprecedented type of climate change, and it is driving a cascade of side effects in our climate system. It’s these side effects, such as changes in sea level along heavily populated coastlines and the worldwide retreat of mountain glaciers that millions of people depend on for drinking water and agriculture, that are likely to have a much greater impact on society than temperature change alone.

Broecker, W. S. (1975). Climatic Change: Are We on the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming? Science , 189(4201), 460–463. http://doi.org/10.1126/science.189.4201.460

Climate Data Primer . Climate.gov.

Gillett, N. P., V. K. Arora, G. M. Flato, J. F. Scinocca, and K. von Salzen, 2012: Improved constraints on 21st-century warming derived using 160 years of temperature observations. Geophysical Research Letters, 39, 5, doi:10.1029/2011GL050226. [Available online at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2011GL050226/pdf ]

Global Warming FAQ . Climate.gov.

How do we know the world has warmed? by J. J. Kennedy, P. W. Thorne, T. C. Peterson, R. A. Ruedy, P. A. Stott, D. E. Parker, S. A. Good, H. A. Titchner, and K. M. Willett, 2010: [in " State of the Climate in 2009 "]. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 91 (7), S79-106.

Huber, M., and R. Knutti, 2012: Anthropogenic and natural warming inferred from changes in Earth’s energy balance. Nature Geoscience, 5, 31-36, doi:10.1038/ngeo1327. [Available online at http://www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/v5/n1/pdf/ngeo1327.pdf ]

Jouzel, J., et al. 2007. EPICA Dome C Ice Core 800KYr Deuterium Data and Temperature Estimates. IGBP PAGES/World Data Center for Paleoclimatology Data Contribution Series # 2007-091. NOAA/NCDC Paleoclimatology Program, Boulder CO, USA.

Mann, M. E., Zhang, Z., Hughes, M. K., Bradley, R. S., Miller, S. K., Rutherford, S., & Ni, F., 2008: Proxy-based reconstructions of hemispheric and global surface temperature variations over the past two millennia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(36), 13252-13257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805721105.

Melillo, Jerry M., Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and Gary W. Yohe, Eds., 2014: Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment . U.S. Global Change Research Program, 841 pp. doi:10.7930/J0Z31WJ2. Online at: nca2014.globalchange.gov

National Academy of Sciences, Climate Research Board, Carbon Dioxide and Climate: A Scientific Assessment (Jules Charney, Chair) . (1979). Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences. [Online (pdf)] http://web.atmos.ucla.edu/~brianpm/download/charney_report.pdf

Walsh, J., D. Wuebbles, K. Hayhoe, J. Kossin, K. Kunkel, G. Stephens, P. Thorne, R. Vose, M. Wehner, J. Willis, D. Anderson, V. Kharin, T. Knutson, F. Landerer, T. Lenton, J. Kennedy, and R. Somerville, 2014: Appendix 4: Frequently Asked Questions. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program, 790-820. doi:10.7930/J0G15XS3

Weart, S. (2008). Timeline (Milestones). In The Discovery of Global Warming . [Online] American Institute of Physics website.

What's in a Name? Global Warming vs. Climate Change . NASA.

We value your feedback

Help us improve our content

Related Content

News & features, carbon dioxide: earth's hottest topic is just warming up, climate change: atmospheric carbon dioxide, what's the hottest earth's ever been, ocean acidification: the other carbon problem, maps & data, climate forcing, global temperature anomalies - map viewer, ocean heat content - seasonal difference from average, teaching climate, toolbox for teaching climate & energy, white house climate education and literacy initiative, the smap/globe partnership: citizen scientists measure soil moisture, climate resilience toolkit, food production, food- and water-related threats.

Home — Essay Samples — Environment — Environment Problems — Global Warming

Argumentative Essays on Global Warming

Global warming: a critical analysis through essays.

The purpose of global warming essay topics is to ignite your creativity and personal interest in one of the most pressing issues of our time. Choosing the right topic is crucial, as it can greatly influence both the depth of your research and the impact of your arguments.

Global Warming Essay Topics

Different types of essays allow you to explore global warming from various angles, whether it be through an argumentative lens, a compare and contrast approach, descriptive insights, persuasive arguments, or narrative storytelling. Below, you will find a curated list of topics suitable for each essay type, accompanied by introduction and conclusion paragraph examples to help structure your essay effectively.

Global Warming Argumentative Essay Topics

- Topic: The Effectiveness of Current Policies on Reducing Carbon Emissions

- Thesis Statement: Current policies need significant strengthening to effectively reduce carbon emissions and combat global warming.

Introduction Example: As global warming poses a significant threat to our planet, the effectiveness of current policies to reduce carbon emissions has come under scrutiny. This essay will argue that while some policies have made progress, they are largely insufficient to meet the global targets set by the Paris Agreement.

Conclusion Example: In conclusion, the analysis demonstrates that current policies, though a step in the right direction, fall short of the aggressive action required to mitigate global warming. It calls for a global reevaluation and reinforcement of policies to ensure a sustainable future.

Global Warming Compare and Contrast Essays

- Topic: Renewable Energy vs. Fossil Fuels: Impacts on Global Warming

- Thesis Statement: Renewable energy sources offer a cleaner, more sustainable alternative to fossil fuels, making them essential in the fight against global warming.

Introduction Example: The debate between renewable energy and fossil fuels is at the forefront of the global warming discussion. This essay will compare and contrast the environmental impacts of both energy sources, highlighting the superiority of renewables in combating global warming.

Conclusion Example: The comparison clearly shows that renewable energy not only reduces the carbon footprint but also is a viable alternative to fossil fuels, underscoring the need for a global shift towards renewables to mitigate the effects of global warming.

Descriptive Essays on Global Warming

- Topic: The Visible Effects of Global Warming on Arctic Wildlife

- Thesis Statement: The devastating effects of global warming on Arctic wildlife underscore the urgent need for global environmental policies.

Introduction Example: Global warming has had a profound impact on Arctic wildlife, with visible effects that signal a broader ecological crisis. This essay aims to describe these impacts in detail, drawing attention to the urgent need for action.

Conclusion Example: In summarizing the dire situation in the Arctic, it becomes clear that global warming is not a distant threat but a current reality, necessitating immediate and decisive action to protect our planet's biodiversity.

Persuasive Essays

- Topic: The Role of Individuals in Combating Global Warming

- Thesis Statement: Individual efforts are crucial and effective in the fight against global warming, complementing larger-scale initiatives.

Introduction Example: While the fight against global warming often focuses on governmental and corporate actions, the role of individuals cannot be underestimated. This essay will persuade readers that individual actions, though seemingly small, can collectively make a significant impact on combating global warming.

Conclusion Example: As demonstrated, individual actions play a pivotal role in combating global warming. It is through collective effort at every level of society that we can hope to address this global challenge effectively.

Narrative Essays

- Topic: A Personal Journey to Reduce My Carbon Footprint

- Thesis Statement: Individual actions to reduce carbon footprints can inspire change and contribute significantly to combating global warming.

Introduction Example: Embarking on a personal journey to reduce my carbon footprint was both enlightening and challenging. Through this narrative, I aim to share my experiences, the obstacles I faced, and the impact of my actions on a personal level.

Conclusion Example: My journey reveals that while individual actions may seem small in the grand scheme of global warming, they are powerful catalysts for change, underscoring the importance of personal responsibility in the global effort to combat climate change.

Engagement and Creativity

As you delve into your essay on global warming, we encourage you to select a topic that not only aligns with your academic goals but also sparks your interest. Let your creativity guide your research and argumentation, making your essay not just an academic exercise, but a personal exploration of one of the most urgent issues facing our world today.

Educational Value

Writing about global warming is not only an opportunity to contribute to an important global conversation but also a chance to develop valuable academic skills. Whether you're crafting an argumentative, compare and contrast, descriptive, persuasive, or narrative essay, you're engaging in critical thinking, research, and persuasive communication—skills that are invaluable in both academic and professional settings.

The Plight of Polar Bears in a Warming World

Hypothesis of global warming, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

150-word on Global Warming

Global warming: how we can stop it, facts, causes and effects of global warming, the effect of global warming on the environment, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Global Warming, Its Causes, Effects, and Ways to Stop

Global warming: the biggest challenge facing our planet, global warming: why we should not ignore the problem, how humanity should stop global warming, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

A Modest Proposal: How to End Global Warming

Global warming and climate change are on the rise, global warming and what people can do to save earth, global warming and solutions to it, green house effect and how it is contributed to by co2 emissions, global warming is a thing everyone should care about, impact pollution on global warming, overview of the effects of global warming, how global warming became real: a retrospective approach, environmental problems: global warming, how coal impacts on global warming, the impact of global warming on climate change, global warming: natures pressure cooker or manmade fiery hell, influence of interest groups on the problem of global warming, the crucial importance of addressing climate change, air pollution its causes and damaging effects, life-cycle global warming emissions, earth hour can't hold a candle to global warming, causes and threats of sea level rise, the changes in the ocean: cause and effect.

Global warming refers to the long-term increase in Earth's average surface temperature primarily caused by the buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Greta Thunberg: a prominent Swedish environmental activist who gained international recognition for her efforts to combat climate change. Al Gore: an American politician and environmentalist who has been instrumental in raising awareness about global warming. He wrote the book "An Inconvenient Truth" and co-founded the Climate Reality Project, advocating for climate change solutions and promoting sustainable practices. Sir David Attenborough: a renowned British naturalist and broadcaster who has dedicated his career to documenting the wonders of the natural world. In recent years, he has become an influential voice in raising awareness about the impacts of global warming through his documentaries and speeches. Dr. James Hansen: an American climatologist and former NASA scientist. He is known for his research on climate change and his efforts to communicate the urgency of addressing global warming. Elon Musk: the CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, has played a significant role in promoting renewable energy and sustainable transportation. Through Tesla, Musk has popularized electric vehicles and accelerated the transition away from fossil fuels, contributing to the fight against global warming.

The historical context of global warming can be traced back to the late 19th century when scientists first began to recognize the potential impact of human activities on the Earth's climate. In the early 20th century, researchers such as Svante Arrhenius hypothesized that the burning of fossil fuels could lead to an increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and subsequently cause a rise in global temperatures. During the mid-20th century, advancements in technology and industrialization led to a significant increase in greenhouse gas emissions. The post-World War II era marked a period of rapid economic growth and widespread use of fossil fuels, further contributing to the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. In the 1980s and 1990s, scientific consensus on the reality of global warming began to solidify. The establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988 provided a platform for scientists and policymakers to collaborate and assess the scientific evidence surrounding climate change. The historical context of global warming also includes international efforts to address this issue. Key milestones include the adoption of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992 and the subsequent negotiations that led to the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. These agreements aimed to promote international cooperation and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

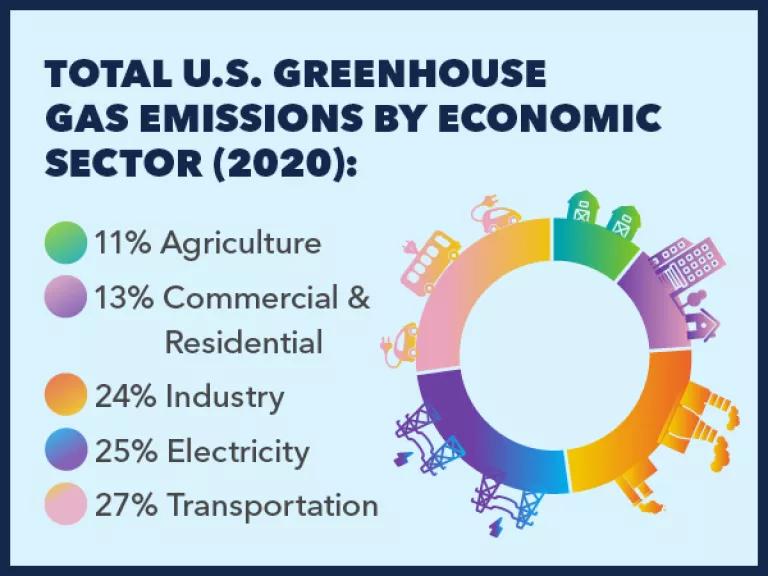

1. Increase in greenhouse gases and combustion of fossil fuels. 2. Exponential increase in population. 3. Destruction of ecosystems and deforestation. 4. Destruction of marine ecosystems.

1. Melting of polar ice caps and rising sea levels. 2. Changes to ecosystems. 3. Mass migrations. 4. Acidity of our oceans. 5. Species extinction. 6. Extreme meteorological phenomena.

Calculating carbon footprint. Reducing greenhouse gases. Offsetting carbon emissions.

Public opinion on the topic of global warming varies, but there is a growing recognition and concern about its impacts. Over the years, surveys and polls have indicated that a majority of the global population acknowledges the reality of global warming and considers it a significant issue. Many individuals are increasingly aware of the scientific consensus that human activities, particularly the burning of fossil fuels, contribute to the increase in greenhouse gases and subsequent global temperature rise. The severity of extreme weather events, melting ice caps, and rising sea levels further emphasize the urgency of addressing global warming. However, public opinion on specific aspects of global warming, such as its causes and potential solutions, can be diverse and influenced by various factors including political beliefs, cultural values, and economic considerations. Debates continue regarding the extent of human influence on climate change and the appropriate measures to mitigate its effects. Efforts to raise awareness and educate the public about global warming have led to increased activism, calls for policy changes, and the promotion of sustainable practices. Public opinion plays a crucial role in shaping political will and policy decisions, influencing the development and implementation of climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies.

The topic of global warming has garnered significant representation in both media and literature, reflecting the urgency and importance of addressing climate change. In media, documentaries like "An Inconvenient Truth" by Al Gore and "Before the Flood" by Leonardo DiCaprio have gained widespread attention for their compelling exploration of the environmental crisis. These films present scientific evidence, personal narratives, and expert interviews to raise awareness and provoke action. In literature, works such as "The Sixth Extinction" by Elizabeth Kolbert and "This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate" by Naomi Klein offer in-depth analyses of global warming's causes and consequences. These books provide rigorous research, critical perspectives, and propose alternative approaches to mitigate climate change. Moreover, literary works of fiction, such as "Flight Behavior" by Barbara Kingsolver and "Oryx and Crake" by Margaret Atwood, employ global warming as a central theme. These novels explore the social, political, and ecological implications of a changing climate, using storytelling to engage readers on a personal and emotional level. News outlets regularly cover stories related to global warming, reporting on scientific studies, climate events, and policy debates. Newspapers, magazines, and online platforms offer articles that delve into the impacts of climate change on various sectors, including agriculture, health, and the environment.

1. The global average temperature has risen by approximately 1 degree Celsius since the pre-industrial era. 2. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), if global warming exceeds 1.5 degrees Celsius, it could lead to irreversible and catastrophic effects, such as widespread species extinction, severe weather events, and rising sea levels. 3. The concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the Earth's atmosphere is the highest it has been in at least 800,000 years, primarily due to human activities. CO2 is a greenhouse gas that traps heat and contributes to the warming of the planet. 4. Glacier retreat is a significant consequence of global warming. Over the past century, glaciers around the world have lost a substantial amount of ice, affecting water supplies, ecosystems, and contributing to sea-level rise. 5. The economic costs of climate change are substantial. According to estimates by the World Bank, the impacts of global warming, including extreme weather events, reduced agricultural productivity, and health-related expenses, could lead to an annual loss of 5-10% of global GDP by the end of the century.

The topic of global warming is of utmost importance to write an essay about due to its far-reaching implications for our planet and future generations. Global warming, driven by human activities, has led to unprecedented changes in our climate system, affecting ecosystems, economies, and human well-being. By exploring this topic in an essay, we can increase awareness and understanding of the causes, impacts, and potential solutions to address global warming. An essay on global warming provides an opportunity to delve into the scientific evidence supporting climate change, highlighting the role of greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and other factors. It allows for an examination of the consequences, such as rising temperatures, sea-level rise, and extreme weather events, on various aspects of life, including agriculture, biodiversity, and human health. Furthermore, discussing global warming in an essay encourages critical thinking and engagement with the complex social, political, and economic dimensions of the issue. It prompts us to consider the ethical responsibilities we have towards future generations, as well as the importance of international cooperation and policy actions to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

1. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2018). Global Warming of 1.5°C. Cambridge University Press. 2. Solomon, S., Qin, D., Manning, M., Alley, R., Berntsen, T., Bindoff, N., ... & Zhang, P. (Eds.). (2007). Climate change 2007: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. 3. NASA. (2021). Global Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. Retrieved from https://climate.nasa.gov/ 4. Union of Concerned Scientists. (2020). The Science of Climate Change. Retrieved from https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/science-climate-change 5. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2019). Climate.gov. Retrieved from https://www.climate.gov/ 6. World Meteorological Organization. (2021). State of the Global Climate 2020. Retrieved from https://public.wmo.int/en/resources/state-of-the-global-climate 7. National Geographic. (2021). Climate Change. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/global-warming/ 8. IPCC. (2014). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. 9. United Nations. (2015). Paris Agreement. Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement 10. Environmental Protection Agency. (2021). Climate Change. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/climate-change

Relevant topics

- Climate Change

- Deforestation

- Water Pollution

- Ocean Pollution

- Air Pollution

- Fast Fashion

- Natural Disasters

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Digg

Latest Earthquakes | Chat Share Social Media

What is the difference between global warming and climate change?

Although people tend to use these terms interchangeably, global warming is just one aspect of climate change. “Global warming” refers to the rise in global temperatures due mainly to the increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. “Climate change” refers to the increasing changes in the measures of climate over a long period of time – including precipitation, temperature, and wind patterns.

Related Content

- Publications

Does the USGS monitor global warming?

Not specifically. Our charge is to understand characteristics of the Earth, especially the Earth's surface, that affect our Nation's land, water, and biological resources. That includes quite a bit of environmental monitoring. Other agencies, especially NOAA and NASA, are specifically funded to monitor global temperature and atmospheric phenomena such as ozone concentrations. The work through...

Will global warming produce more frequent and more intense wildfires?

There isn’t a direct relationship between climate change and fire, but researchers have found strong correlations between warm summer temperatures and large fire years, so there is general consensus that fire occurrence will increase with climate change. Hot, dry conditions, however, do not automatically mean fire—something needs to create the spark and actually start the fire. In some parts of...

What are the long-term effects of climate change?

Scientists have predicted that long-term effects of climate change will include a decrease in sea ice and an increase in permafrost thawing, an increase in heat waves and heavy precipitation, and decreased water resources in semi-arid regions. Below are some of the regional impacts of global change forecast by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: North America: Decreasing snowpack in the...

How can climate change affect natural disasters?

With increasing global surface temperatures the possibility of more droughts and increased intensity of storms will likely occur. As more water vapor is evaporated into the atmosphere it becomes fuel for more powerful storms to develop. More heat in the atmosphere and warmer ocean surface temperatures can lead to increased wind speeds in tropical storms. Rising sea levels expose higher locations...

How do changes in climate and land use relate to one another?

The link between land use and the climate is complex. First, land cover--as shaped by land use practices--affects the global concentration of greenhouse gases. Second, while land use change is an important driver of climate change, a changing climate can lead to changes in land use and land cover. For example, farmers might shift from their customary crops to crops that will have higher economic...

Why is climate change happening and what are the causes?

There are many “natural” and “anthropogenic” (human-induced) factors that contribute to climate change. Climate change has always happened on Earth, which is clearly seen in the geological record; it is the rapid rate and the magnitude of climate change occurring now that is of great concern worldwide. Greenhouse gases in the atmosphere absorb heat radiation. Human activity has increased...

What are some of the signs of climate change?

• Temperatures are rising world-wide due to greenhouse gases trapping more heat in the atmosphere. • Droughts are becoming longer and more extreme around the world. • Tropical storms becoming more severe due to warmer ocean water temperatures. • As temperatures rise there is less snowpack in mountain ranges and polar areas and the snow melts faster. • Overall, glaciers are melting at a faster rate...

How do we know the climate is changing?

The scientific community is certain that the Earth's climate is changing because of the trends that we see in the instrumented climate record and the changes that have been observed in physical and biological systems. The instrumental record of climate change is derived from thousands of temperature and precipitation recording stations around the world. We have very high confidence in these...

What is carbon sequestration?

Carbon dioxide is the most commonly produced greenhouse gas. Carbon sequestration is the process of capturing and storing atmospheric carbon dioxide. It is one method of reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere with the goal of reducing global climate change. The USGS is conducting assessments on two major types of carbon sequestration: geologic and biologic .

How does carbon get into the atmosphere?

Atmospheric carbon dioxide comes from two primary sources—natural and human activities. Natural sources of carbon dioxide include most animals, which exhale carbon dioxide as a waste product. Human activities that lead to carbon dioxide emissions come primarily from energy production, including burning coal, oil, or natural gas. Learn more: Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions (EPA)

How much carbon dioxide does the United States and the World emit each year from energy sources?

The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimates that in 2019, the United States emitted 5,130 million metric tons of energy-related carbon dioxide, while the global emissions of energy-related carbon dioxide totaled 33,621.5 million metric tons.

Two Swimming Polar Bears

Data collected from long distance swims by Polar bears suggest that they do not stop to rest during their journey.

Polar Bear Research, B-Roll 1

Spring 2014. USGS scientists conduct a health evaluation of a young male polar bear in the Arctic as part of the annual southern Beaufort Sea population survey. The bear is sedated for approximately an hour while the team records a variety of measurements and collects key biological samples.

PubTalk 11/2012 — Understanding Climate-Wildlife Relationships

-- are American pikas harbingers of changing conditions?

by USGS Research Ecologist Erik Beever

Tracking Pacific Walrus: Expedition to the Shrinking Chukchi Sea Ice

Summer ice retreat in the Chukchi Sea between Alaska and Russia is a significant climate change impact affecting Pacific Walruses, which are being considered for listing as a threatened species. This twelve minute video follows walruses in their summer sea ice habitat and shows how USGS biologists use satellite radio tags to track their movements and behavior.

PubTalk 3/2010 — Changing Times-- A Changing Planet!

Using phenology to take the pulse of our planet

By Jake F. Weltzin, Executive Director, USA National Phenology Network

USGS Public Lecture Series: Climate Change 101

Climate change is an issue of increasing public concern because of its potential effects on land, water, and biological resources.

The Cold Facts About Melting Glaciers

Most glaciers in Washington and Alaska are dramatically shrinking in response to a warming climate.

Permafrost Erosion Measurement

USGS researcher Benjamin Jones examines a collapsed block of ice-rich permafrost on Barter Island along Alaska's Arctic coast.

Crumbling blocks of permafrost along the Beaufort Coast

USGS integrated drought science

Ecosystem vulnerability to climate change in the southeastern united states, usgs arctic science strategy, landsat surface reflectance data, changing arctic ecosystems: sea ice decline, permafrost thaw, and benefits for geese, remote sensing of land surface phenology, delivering climate science about the nation's fish, wildlife, and ecosystems: the u.s. geological survey national climate change and wildlife science center, the u.s. geological survey climate geo data portal: an integrated broker for climate and geospatial data, changing arctic ecosystems - measuring and forecasting the response of alaska's terrestrial ecosystem to a warming climate, polar bear and walrus response to the rapid decline in arctic sea ice, the concept of geologic carbon sequestration.

No abstract available.

Assessing carbon stocks, carbon sequestration, and greenhouse-gas fluxes in ecosystems of the United States under present conditions and future scenarios

Future temperature and soil moisture may alter location of agricultural regions.

Future high temperature extremes and soil moisture conditions may cause some regions to become more suitable for rainfed, or non-irrigated...

Changes in Rainfall, Temperature Expected to Transform Coastal Wetlands This Century

Changes in rainfall and temperature are predicted to transform wetlands in the Gulf of Mexico and around the world within the century, a new study...

Walrus Sea-Ice Habitats Melting Away

Habitat for the Pacific walrus in the Chukchi Sea is disappearing from beneath them as the warming climate melts away Arctic sea ice in the spring...

Old Growth May Help Protect Northwest Birds from Warming Temperatures

Researchers are working to understand how to lessen the impacts of climate change on birds and other forest inhabitants.

Ancient Permafrost Quickly Transforms to Carbon Dioxide upon Thaw

Researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey and key academic partners have quantified how rapidly ancient permafrost decomposes upon thawing and how...

Scientists Predict Gradual, Prolonged Permafrost Greenhouse Gas Emissions

A new scientific synthesis suggests a gradual, prolonged release of greenhouse gases from permafrost soils in Arctic and sub-Arctic regions, which may...

Rare Insect Found Only in Glacier National Park Imperiled by Melting Glaciers

The persistence of an already rare aquatic insect, the western glacier stonefly, is being imperiled by the loss of glaciers and increased stream...

New Heights of Global Topographic Data Will Aid Climate Change Research

The U.S. Geological Survey announced today that improved global topographic (elevation) data are now publicly available for North and South America...

Water Cycle

- Weather & Climate

Societal Applications

Whats in a name global warming vs. climate change.

The Internet is full of references to global warming . The Union of Concerned Scientists website on climate change is titled "Global Warming," just one of many examples. But we don't use global warming much on this website. We use the less appealing "climate change." Why?

To a scientist, global warming describes the average global surface temperature increase from human emissions of greenhouse gases. Its first use was in a 1975 Science article by geochemist Wallace Broecker of Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory: "Climatic Change: Are We on the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming?"1

Broecker's term was a break with tradition. Earlier studies of human impact on climate had called it "inadvertent climate modification."2 This was because while many scientists accepted that human activities could cause climate change, they did not know what the direction of change might be. Industrial emissions of tiny airborne particles called aerosols might cause cooling, while greenhouse gas emissions would cause warming. Which effect would dominate?

For most of the 1970s, nobody knew. So "inadvertent climate modification," while clunky and dull, was an accurate reflection of the state of knowledge.

The first decisive National Academy of Science study of carbon dioxide's impact on climate, published in 1979, abandoned "inadvertent climate modification." Often called the Charney Report for its chairman, Jule Charney of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, declared: "if carbon dioxide continues to increase, [we find] no reason to doubt that climate changes will result and no reason to believe that these changes will be negligible."3

In place of inadvertent climate modification, Charney adopted Broecker's usage. When referring to surface temperature change, Charney used "global warming." When discussing the many other changes that would be induced by increasing carbon dioxide, Charney used "climate change." Definitions

Global warming: the increase in Earth’s average surface temperature due to rising levels of greenhouse gases.

Climate change: a long-term change in the Earth’s climate, or of a region on Earth.

Within scientific journals, this is still how the two terms are used. Global warming refers to surface temperature increases, while climate change includes global warming and everything else that increasing greenhouse gas amounts will affect.

During the late 1980s one more term entered the lexicon, “global change.” This term encompassed many other kinds of change in addition to climate change. When it was approved in 1989, the U.S. climate research program was embedded as a theme area within the U.S. Global Change Research Program.

But global warming became the dominant popular term in June 1988, when NASA scientist James E. Hansen had testified to Congress about climate, specifically referring to global warming. He said: "global warming has reached a level such that we can ascribe with a high degree of confidence a cause and effect relationship between the greenhouse effect and the observed warming."4 Hansen's testimony was very widely reported in popular and business media, and after that popular use of the term global warming exploded. Global change never gained traction in either the scientific literature or the popular media.

But temperature change itself isn't the most severe effect of changing climate. Changes to precipitation patterns and sea level are likely to have much greater human impact than the higher temperatures alone. For this reason, scientific research on climate change encompasses far more than surface temperature change. So "global climate change" is the more scientifically accurate term. Like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, we've chosen to emphasize global climate change on this website, and not global warming.

1 Wallace Broecker, "Climatic Change: Are We on the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming?" Science, vol. 189 (8 August 1975), 460-463.

2 For example, see: MIT, Inadvertent Climate Modification: Report of the Study of Man's Impact on Climate (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1971).

3National Academy of Science, Carbon Dioxide and Climate, Washington, D.C., 1979, p. vii.

4U.S. Senate, Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, "Greenhouse Effect and Global Climate Change, part 2" 100th Cong., 1st sess., 23 June 1988, p. 44.

http://www.nasa.gov/topics/earth/features/climate_by_any_other_name.html

Try AI-powered search

The past, present and future of climate change

Climate issue: replacing the fossil-fuel technology which is reshaping the climate remains a massive task.

Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

I N THE EARLY 19th century Joseph Fourier, a French pioneer in the study of heat, showed that the atmosphere kept the Earth warmer than it would be if exposed directly to outer space. By 1860 John Tyndall, an Irish physicist, had found that a key to this warming lay in an interesting property of some atmospheric gases, including carbon dioxide. They were transparent to visible light but absorbed infrared radiation, which meant they let sunlight in but impeded heat from getting out. By the turn of the 20th century Svante Arrhenius, a Swedish chemist, was speculating that low carbon-dioxide levels might have caused the ice ages, and that the industrial use of coal might warm the planet.

What none foresaw was how fast, and how far, the use of fossil fuels would grow (see chart above). In 1900 the deliberate burning of fossil fuels—almost entirely, at the time, coal—produced about 2bn tonnes of carbon dioxide. By 1950 industrial emissions were three times that much. Today they are close to 20 times that much.

That explosion of fossil-fuel use is inseparable from everything else which made the 20th century unique in human history. As well as providing unprecedented access to energy for manufacturing, heating and transport, fossil fuels also made almost all the Earth’s other resources vastly more accessible. The nitrogen-based explosives and fertilisers which fossil fuels made cheap and plentiful transformed mining, warfare and farming. Oil refineries poured forth the raw materials for plastics. The forests met the chainsaw.

In no previous century had the human population doubled. In the 20th century it came within a whisker of doubling twice. In no previous century had world GDP doubled. In the 20th century it doubled four times and then some.

An appendix to a report prepared by America’s Presidential Science Advisory Committee in 1965 marks the first time that politicians were made directly aware of the likely climate impact of all this. In the first half of the century scientists believed that almost all the carbon dioxide given off by industry would be soaked up by the oceans. But Roger Revelle, an oceanographer, had shown in the 1950s that this was not the case. He had also instituted efforts to measure year-on-year changes in the atmosphere’s carbon-dioxide level. By 1965 it was clear that it was steadily rising.

The summary of what that rise meant, novel when sent to the president, is now familiar. Carbon stored up in the crust over hundreds of millions of years was being released in a few generations; if nothing were done, temperatures and sea levels would rise to an extent with no historic parallel. Its suggested response seems more bizarre: trillions of ping-pong balls on the ocean surface might reflect back more of the sun’s rays, providing a cooling effect.

The big difference between 1965 and now, though, is what was then a peculiar prediction is now an acute predicament. In 1965 the carbon-dioxide level was 320 parts per million (ppm); unprecedented, but only 40ppm above what it had been two centuries earlier. The next 40ppm took just three decades. The 40ppm after that took just two. The carbon-dioxide level is now 408ppm, and still rising by 2ppm a year.

Records of ancient atmospheres provide an unnerving context for this precipitous rise. Arrhenius was right in his hypothesis that a large part of the difference in temperature between the ice ages and the warm “interglacials” that separated them was down to carbon dioxide. Evidence from Antarctic ice cores shows the two going up and down together over hundreds of thousands of years. In interglacials the carbon-dioxide level is 1.45 times higher than it is in the depths of an ice age. Today’s level is 1.45 times higher than that of a typical interglacial. In terms of carbon dioxide’s greenhouse effect, today’s world is already as far from that of the 18th century as the 18th century was from the ice age (see “like an ice age” chart).

Not all the difference in temperature between interglacials and ice ages was because of carbon dioxide. The reflection of sunlight by the expanded ice caps added to the cooling, as did the dryness of the atmosphere. But the ice cores make it clear that what the world is seeing is a sudden and dramatic shift in fundamental parameter of the planet’s climate. The last time the Earth had a carbon-dioxide level similar to today’s, it was on average about 3°C warmer. Greenland’s hills were green. Parts of Antarctica were fringed with forest. The water now frozen over those landscapes was in the oceans, providing sea levels 20 metres higher than today’s.

Ping-pong ding-dong

There is no evidence that President Lyndon Johnson read the 1965 report. He certainly didn’t act on it. The idea of deliberately changing the Earth’s reflectivity, whether with ping-pong balls or by other means, was outlandish. The idea that the fuels on which the American and world economies were based should be phased out would have seemed even more so. And there was, back then, no conclusive proof that humans were warming the Earth.

Proof took time. Carbon dioxide is not the only greenhouse gas. Methane and nitrous oxide trap heat, too. So does water vapour, which thereby amplifies the effects of the others. Because warmth drives evaporation, a world warmed by carbon dioxide will have a moister atmosphere, which will make it warmer still. But water vapour also condenses into clouds—some of which cool the world and some of which warm it further. Then and now, the complexities of such processes make precision about the amount of warming expected for a given carbon-dioxide level unachievable.

Further complexities abound. Burning fossil fuels releases particles small enough to float in the air as well as carbon dioxide. These “aerosols” warm the atmosphere, but also shade and thereby cool the surface below; in the 1960s and 1970s some thought their cooling power might overpower the warming effects of carbon dioxide. Volcanic eruptions also produce surface-cooling aerosols, the effects of which can be global; the brightness of the sun varies over time, too, in subtle ways. And even without such external “forcings”, the internal dynamics of the climate will shift heat between the oceans and atmosphere over various timescales. The best known such shifts, the El Niño events seen a few times a decade, show up in the mean surface temperature of the world as a whole.

These complexities meant that, for a time, there was doubt about greenhouse warming, which the fossil-fuel lobby deliberately fostered. There is no legitimate doubt today. Every decade since the 1970s has been warmer than the one before, which rules out natural variations. It is possible to compare climate models that account for just the natural forcings of the 20th century with those that take into account human activities, too. The effects of industry are not statistically significant until the 1980s. Now they are indisputable.

At the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, around the time that the human effect on the climate was becoming clearly discernible, the nations of the world signed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change ( UNFCCC ). By doing so they promised to “prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system”.

Since then humans have emitted 765bn more tonnes of carbon dioxide; the 2010s have been, on average, some 0.5°C hotter than the 1980s. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ( IPCC ) estimates that mean surface temperature is now 1°C above what it was in the pre-industrial world, and rising by about 0.2°C a decade. In mid- to high-northern latitudes, and in some other places, there has already been a warming of 1.5°C or more; much of the Arctic has seen more than 3°C (see map).

The figure of 1.5°C matters because of the Paris agreement, signed by the parties to the UNFCCC in 2015. That agreement added targets to the original goal of preventing “dangerous interference” in the climate: the signatories promised to hold global warming “well below” 2°C above pre-industrial temperatures and to make “efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C”.

Neither 1.5°C nor 2°C has any particular significance outside these commitments. Neither marks a threshold beyond which the world becomes uninhabitable, or a tipping point of no return. Conversely, they are not limits below which climate change has no harmful effects. There must be thresholds and tipping points in a warming world. But they are not well enough understood for them to be associated with specific rises in mean temperature.

For the most part the harm warming will do—making extreme weather events more frequent and/or more intense, changing patterns of rainfall and drought, disrupting ecosystems, driving up sea levels—simply gets greater the more warming there is. And its global toll could well be so great that individual calamities add little.

At present further warming is certain, whatever the world does about its emissions. This is in part because, just as a pan of water on a hob takes time to boil when the gas below is lit, so the world’s mean temperature is taking time to respond to the heating imposed by the sky above. It is also because what matters is the total amount of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, not the rate at which it increases. Lowering annual emissions merely slows the rate at which the sky’s heating effect gets stronger; surface warming does not come to an end until the greenhouse-gas level is no longer increasing at all. If warming is to be held to 1.5°C that needs to happen by around 2050; if it is to be kept well below 2°C there are at best a couple more decades to play with.

Revolution in reverse

Thus, in its simplest form, the 21st century’s supertanker-U-turn challenge: reversing the 20-fold increase in emissions the 20th century set in train, and doing so at twice the speed. Replacing everything that burns gas or coal or oil to heat a home or drive a generator or turn a wheel. Rebuilding all the steelworks; refashioning the cement works; recycling or replacing the plastics; transforming farms on all continents. And doing it all while expanding the economy enough to meet the needs and desires of a population which may well be half again as large by 2100 as it is today.

“Integrated assessment models”, which combine economic dynamics with assumptions about the climate, suggest that getting to zero emissions by 2050 means halving current emissions by 2030. No nation is on course to do that. The national pledges made at the time of the Paris agreement would, if met, see global emissions in 2030 roughly equivalent to today’s. Even if emissions decline thereafter, that suggests a good chance of reaching 3°C.

Some countries already emit less than half as much carbon dioxide as the global average. But they are countries where many people desperately want more of the energy, transport and resources that fossil fuels have provided richer nations over the past century. Some of those richer nations have now pledged to rejoin the low emitters. Britain has legislated for massive cuts in emissions by 2050. But the fact that legislation calls for something does not mean it will happen. And even if it did, at a global level it would remain a small contribution.

This is one of the problems of trying to stop warming through emission policies. If you reduce emissions and no one else does, you face roughly the same climate risk as before. If everyone else reduces and you do not, you get almost as much benefit as you would if you had joined in. It is a collective-action problem that only gets worse as mitigation gets more ambitious.

What is more, the costs and benefits are radically uncertain and unevenly distributed. Most of the benefit from curtailing climate change will almost certainly be felt by people in developing countries; most of the cost of emission cuts will be felt elsewhere. And most of the benefits will be accrued not today, but in 50 or 100 years.

It is thus fitting that the most striking recent development in climate politics is the rise of activism among the young. For people born, like most of the world’s current leaders, well before 1980, the second half of the 21st century seems largely hypothetical. For people born after 2000, like Greta Thunberg, a Swedish activist, and some 2.6bn others, it seems like half their lives. This gives moral weight to their demands that the Paris targets be met, with emissions halved by 2030. But the belief that this can be accomplished through a massive influx of “political will” severely underestimates the challenge.

It is true that, after a spectacular boom in renewable-energy installations, electricity from the wind and the sun now accounts for 7% of the world’s total generation. The price of such installations has tumbled; they are now often cheaper than fossil-fuel generating capacity, though storage capacity and grid modifications may make that advantage less at the level of the whole electricity system.

One step towards halving emissions by 2030 would be to ramp such renewable-electricity generation up to half the total. This would mean a fivefold-to-tenfold increase in capacity. Expanding hydroelectricity and nuclear power would lessen the challenge of all those square kilometres of solar panels and millions of windmills. But increased demand would heighten it. Last year world electricity demand rose by 3.7%. Eleven years of such growth would see demand in 2030 half as large again as demand in 2018. All that new capacity would have to be fossil-fuel-free.

And electricity is the easy part. Emissions from generating plants are less than 40% of all industrial emissions. Progress on reducing emissions from industrial processes and transport is far less advanced. Only 0.5% of the world’s vehicles are electric, according to Bloomberg NEF , a research firm. If that were to increase to 50% without increasing emissions the production of fossil-fuel-free electricity would have to shoot up yet further.

The investment needed to bring all this about would be unprecedented. So would the harm to sections of the fossil economy. According to Carbon Tracker, a think-tank, more than half the money the big oil companies plan to spend on new fields would be worthless in a world that halved emissions by 2030. The implications extend to geopolitics. A world in which the oil price is no longer of interest is one very different from that of the past century.

Putting off to tomorrow

Dislocation on such a scale might be undertaken if a large asteroid on a fixed trajectory were set to devastate North America on January 1st 2031. It is far harder to imagine when the victims are less readily identifiable and the harms less cosmically certain—even if they eventually turn out to be comparable in scale. Realising this, the climate negotiators of the world have, over the past decade, increasingly come to depend on the idea of “negative emissions”. Instead of not putting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere at all, put it in and take it out later. By evoking ever larger negative emissions later in the century it is possible to accept a later peak and a slower reduction while still being able to say that you will end up within the 1.5°C or 2°C limit (see “four futures” chart).

Unfortunately, technologies capable of delivering negative emissions of billions of tonnes a year for reasonable prices over decades do not exist. There are, though, ideas about how they could be brought into being. One favoured by modellers involves first growing plants, which suck up atmospheric carbon dioxide through photosynthesis, and then burning them in power stations which store the carbon dioxide they produce underground. A surmountable problem is that no such systems yet exist at scale. A much tougher one is that the amount of land required for growing all those energy crops would be enormous.

This opens up a dilemma. Given that reducing emissions seems certain not to deliver quickly enough, it would seem stupid not to put serious effort into developing better ways of achieving negative emissions. But the better such R & D makes the outlook for negative emissions appear, the more the impetus for prompt emissions reduction diminishes. Something similar applies for a more radical potential response, solar geoengineering, which like the ping-pong balls of 1965 would reflect sunlight back to space before it could warm the Earth. Researchers thinking about this all stress that it should be used to reduce the harm of carbon dioxide already emitted, not used as an excuse to emit more. But the temptation would be there.

Even if the world were doing enough to limit warming to 2°C, there would still be a need for adaptation. Many communities are not even well adapted to today’s climate. Adaptation is in some ways a much easier policy to pursue than emissions reduction. But it has disadvantages. It gets harder as things get worse. It has a strong tendency to be reactive. And it is most easily achieved by those with resources; people who are marginalised and excluded, who the IPCC finds tend to be most affected by climate change, have the least capacity to adapt to it. It can also fall prey to the “moral hazard” problem encountered by negative emissions and solar geoengineering.

None of this means adaptation is not worthwhile. It is vital, and the developed nations—developed thanks to fossil fuels—have a duty to help their poorer counterparts achieve it, a duty acknowledged in Paris, if as yet barely acted on. But it will not stabilise the climate that humans have, in their global growth spurt, destabilised. And it will not stop all the suffering that instability will bring. ■

Sign up to our new fortnightly climate-change newsletter here

This article appeared in the Briefing section of the print edition under the headline “What goes up”

From the September 21st 2019 edition

Discover stories from this section and more in the list of contents

More from Briefing

Talent is scarce. Yet many countries spurn it

There is growing competition for the best and the brightest migrants

America’s “left-behind” are doing better than ever

But manufacturing jobs are still in decline

Swing-state economies are doing just fine

They would be doing even better if the Biden-Harris administration had been more cynical

Can Kamala Harris win on the economy?

A visit to a crucial swing state reveals the problems she will face

Chinese firms are growing rapidly in the global south

Western firms beware

A shift in the media business is changing what it is to be a sports fan

Team loyalty is being replaced by “fluid fandom”

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

- Climatic variation since the last glaciation

- The greenhouse effect

- Radiative forcing

- Water vapour

- Carbon dioxide

- Surface-level ozone and other compounds

- Nitrous oxides and fluorinated gases

- Land-use change

- Stratospheric ozone depletion

- Volcanic aerosols

- Variations in solar output

- Variations in Earth’s orbit

- Water vapour feedback

- Cloud feedbacks

- Ice albedo feedback

- Carbon cycle feedbacks

- Modern observations

- Prehistorical climate records

- Theoretical climate models

- Patterns of warming

- Precipitation patterns

- Regional predictions

- Ice melt and sea level rise

- Ocean circulation changes

- Tropical cyclones

- Environmental consequences of global warming

- Socioeconomic consequences of global warming

How does global warming work?

Where does global warming occur in the atmosphere, why is global warming a social problem, where does global warming affect polar bears.

global warming

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- U.S. Department of Transportation - Global Warming: A Science Overview

- NOAA Climate.gov - Climate Change: Global Temperature

- Natural Resources Defense Council - Global Warming 101

- American Institute of Physics - The discovery of global warming

- LiveScience - Causes of Global Warming

- global warming - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- global warming - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Human activity affects global surface temperatures by changing Earth ’s radiative balance—the “give and take” between what comes in during the day and what Earth emits at night. Increases in greenhouse gases —i.e., trace gases such as carbon dioxide and methane that absorb heat energy emitted from Earth’s surface and reradiate it back—generated by industry and transportation cause the atmosphere to retain more heat, which increases temperatures and alters precipitation patterns.

Global warming, the phenomenon of increasing average air temperatures near Earth’s surface over the past one to two centuries, happens mostly in the troposphere , the lowest level of the atmosphere, which extends from Earth’s surface up to a height of 6–11 miles. This layer contains most of Earth’s clouds and is where living things and their habitats and weather primarily occur.

Continued global warming is expected to impact everything from energy use to water availability to crop productivity throughout the world. Poor countries and communities with limited abilities to adapt to these changes are expected to suffer disproportionately. Global warming is already being associated with increases in the incidence of severe and extreme weather, heavy flooding , and wildfires —phenomena that threaten homes, dams, transportation networks, and other facets of human infrastructure. Learn more about how the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report, released in 2021, describes the social impacts of global warming.

Polar bears live in the Arctic , where they use the region’s ice floes as they hunt seals and other marine mammals . Temperature increases related to global warming have been the most pronounced at the poles, where they often make the difference between frozen and melted ice. Polar bears rely on small gaps in the ice to hunt their prey. As these gaps widen because of continued melting, prey capture has become more challenging for these animals.

Recent News

global warming , the phenomenon of increasing average air temperatures near the surface of Earth over the past one to two centuries. Climate scientists have since the mid-20th century gathered detailed observations of various weather phenomena (such as temperatures, precipitation , and storms) and of related influences on climate (such as ocean currents and the atmosphere’s chemical composition). These data indicate that Earth’s climate has changed over almost every conceivable timescale since the beginning of geologic time and that human activities since at least the beginning of the Industrial Revolution have a growing influence over the pace and extent of present-day climate change .

Giving voice to a growing conviction of most of the scientific community , the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was formed in 1988 by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), published in 2021, noted that the best estimate of the increase in global average surface temperature between 1850 and 2019 was 1.07 °C (1.9 °F). An IPCC special report produced in 2018 noted that human beings and their activities have been responsible for a worldwide average temperature increase between 0.8 and 1.2 °C (1.4 and 2.2 °F) since preindustrial times, and most of the warming over the second half of the 20th century could be attributed to human activities.

AR6 produced a series of global climate predictions based on modeling five greenhouse gas emission scenarios that accounted for future emissions, mitigation (severity reduction) measures, and uncertainties in the model projections. Some of the main uncertainties include the precise role of feedback processes and the impacts of industrial pollutants known as aerosols , which may offset some warming. The lowest-emissions scenario, which assumed steep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions beginning in 2015, predicted that the global mean surface temperature would increase between 1.0 and 1.8 °C (1.8 and 3.2 °F) by 2100 relative to the 1850–1900 average. This range stood in stark contrast to the highest-emissions scenario, which predicted that the mean surface temperature would rise between 3.3 and 5.7 °C (5.9 and 10.2 °F) by 2100 based on the assumption that greenhouse gas emissions would continue to increase throughout the 21st century. The intermediate-emissions scenario, which assumed that emissions would stabilize by 2050 before declining gradually, projected an increase of between 2.1 and 3.5 °C (3.8 and 6.3 °F) by 2100.

Many climate scientists agree that significant societal, economic, and ecological damage would result if the global average temperature rose by more than 2 °C (3.6 °F) in such a short time. Such damage would include increased extinction of many plant and animal species, shifts in patterns of agriculture , and rising sea levels. By 2015 all but a few national governments had begun the process of instituting carbon reduction plans as part of the Paris Agreement , a treaty designed to help countries keep global warming to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) above preindustrial levels in order to avoid the worst of the predicted effects. Whereas authors of the 2018 special report noted that should carbon emissions continue at their present rate, the increase in average near-surface air temperature would reach 1.5 °C sometime between 2030 and 2052, authors of the AR6 report suggested that this threshold would be reached by 2041 at the latest.

The AR6 report also noted that the global average sea level had risen by some 20 cm (7.9 inches) between 1901 and 2018 and that sea level rose faster in the second half of the 20th century than in the first half. It also predicted, again depending on a wide range of scenarios, that the global average sea level would rise by different amounts by 2100 relative to the 1995–2014 average. Under the report’s lowest-emission scenario, sea level would rise by 28–55 cm (11–21.7 inches), whereas, under the intermediate emissions scenario, sea level would rise by 44–76 cm (17.3–29.9 inches). The highest-emissions scenario suggested that sea level would rise by 63–101 cm (24.8–39.8 inches) by 2100.

The scenarios referred to above depend mainly on future concentrations of certain trace gases, called greenhouse gases , that have been injected into the lower atmosphere in increasing amounts through the burning of fossil fuels for industry, transportation , and residential uses. Modern global warming is the result of an increase in magnitude of the so-called greenhouse effect , a warming of Earth’s surface and lower atmosphere caused by the presence of water vapour , carbon dioxide , methane , nitrous oxides , and other greenhouse gases. In 2014 the IPCC first reported that concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxides in the atmosphere surpassed those found in ice cores dating back 800,000 years.

Of all these gases, carbon dioxide is the most important, both for its role in the greenhouse effect and for its role in the human economy. It has been estimated that, at the beginning of the industrial age in the mid-18th century, carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere were roughly 280 parts per million (ppm). By the end of 2022 they had risen to 419 ppm, and, if fossil fuels continue to be burned at current rates, they are projected to reach 550 ppm by the mid-21st century—essentially, a doubling of carbon dioxide concentrations in 300 years.

A vigorous debate is in progress over the extent and seriousness of rising surface temperatures, the effects of past and future warming on human life, and the need for action to reduce future warming and deal with its consequences. This article provides an overview of the scientific background related to the subject of global warming. It considers the causes of rising near-surface air temperatures, the influencing factors, the process of climate research and forecasting, and the possible ecological and social impacts of rising temperatures. For an overview of the public policy developments related to global warming occurring since the mid-20th century, see global warming policy . For a detailed description of Earth’s climate, its processes, and the responses of living things to its changing nature, see climate . For additional background on how Earth’s climate has changed throughout geologic time , see climatic variation and change . For a full description of Earth’s gaseous envelope, within which climate change and global warming occur, see atmosphere .

Compare-and-contrast reading on climate change

This morning George Will offered another in his series of reassuring columns about the "overstated" threat of climate change. Today's version:

"When New York Times columnist Tom Friedman called upon 'young Americans' to 'get a million people on the Washington Mall calling for a price on carbon,' another columnist, Mark Steyn, responded : 'If you're 29, there has been no global warming for your entire adult life. If you're graduating high school, there has been no global warming since you entered first grade.' "Which could explain why the Mall does not reverberate with youthful clamors about carbon. And why, regarding climate change, the U.S. government, rushing to impose unilateral cap-and-trade burdens on the sagging U.S. economy, looks increasingly like someone who bought a closetful of platform shoes and bell-bottom slacks just as disco was dying."

Will presented the lack of youthful clamor as a sign of wholesome common sense. If you would like another way to think about the evidence, this one provided not by a columnist but by a physicist at UC Berkeley who has won a MacArthur grant, I recommend Richard A. Muller 's book Physics for Future Presidents . I happened to read most of it on a long plane flight yesterday, so I was all set for Will's column today. So you can be ready before his next one appears, I recommend ordering the book now.

Muller says that the evidence behind the hockey-stick chart is wrong. (Read it yourself to see why.) "In fact, much of what the public 'knows' about global warming is based on distortion, exaggeration, or cherry picking," he says, adding:

"An example of distortion is the melting of the Antarctic ice -- something that actually contradicts the global warming model but is presented as if it verifies them. Exaggeration includes the attribution of Hurricane Katrina to global warming, even though there is no scientific evidence that they are related. Cherry picking is the process of selecting data that verify the global-warming hypothesis but ignoring data that contradict it."

The real purpose of his book is to set out as clearly as possible the way scientists approach the inevitably-conflicting evidence on big public policy issues like climate change (or the real risks of terrorism, or dealing with nuclear waste). Before the Iraq war, it would have been useful for intelligence officials to set out the way they balance their version of inevitably-conflicting and always-incomplete facts. Muller sets out the way climate scientists weigh the evidence pro and con concerning climate change and the probabilities for each explanation.

By the end of the process he has forcefully re-established the principle that real scientists view propositions as most convincing when all the doubts, caveats, and contrary bits of evidence are admitted -- whereas politicians and the public want to hear an all-or-nothing verdict with no hems or haws. Consistent with this approach, it is all the more powerful when Muller concludes that there really are reasons to worry about man-made climate change. He also provides guidelines about sensible and fanciful ways to deal with the problem. I am not equipped to judge this argument on purely scientific grounds; but the book is addressed to lay readers and is convincing in what it says about the process of scientific reasoning. If this latest George Will opus serves to drive readers to Muller's book, it will have done some good.

About the Author

More Stories

An Unlucky President, and a Lucky Man

Biden’s State of the Union Did Something New

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions