Amidst misinformation, critical thinking needs a 21st century upgrade

New book argues that scientific reasoning is a necessity for living in a world shaped by science and tech

By Robert Sanders

UC Berkeley

March 26, 2024

In 2013, the University of California, Berkeley, debuted a course to teach undergraduates the tricks used by scientists to make sense of the world, in the hope that these tricks would prove useful in assessing the claims and counterclaims that bombard us every day.

It was launched by three UC Berkeley professors — a physicist, a philosopher and a psychologist — in response to a world afloat in misinformation and disinformation, where politicians were making policy decisions based on ideas that, if not demonstrably wrong, were at least untested and uncertain.

The class, Sense and Sensibility and Science , was a hit and convinced the professors to write a book based on the class that provides tips not only on how to systematically wade through the noise around us to seek the truth, but also how to work with those holding different values to come to a consensus on how to act.

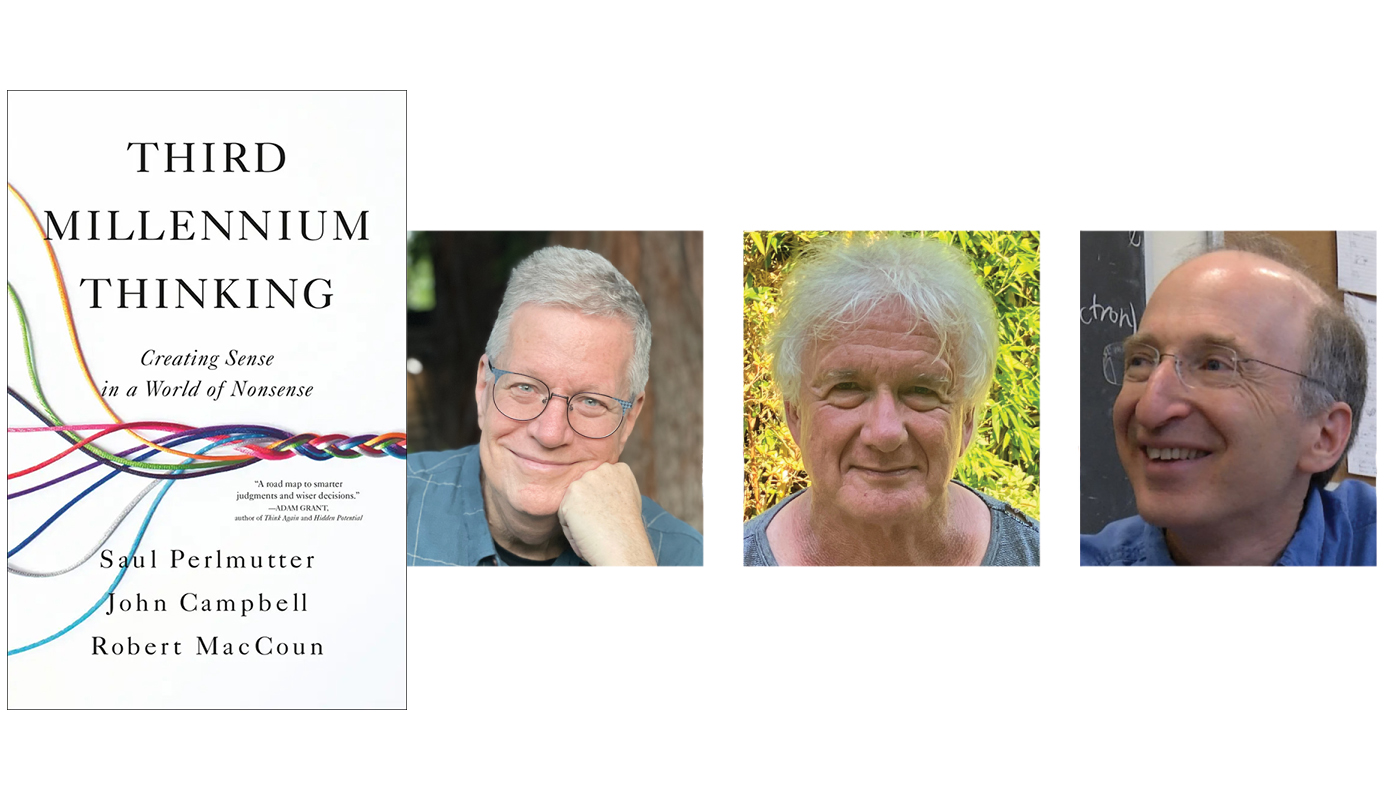

The book, Third Millennium Thinking: Creating sense in a world of nonsense (Little, Brown, Spark), will be published today, March 26 — just in time for the 2024 election season, which promises to be more bluff and bluster than rational argument.

Courtesy of Little, Brown, Spark

Saul Perlmutter , a Nobel Prize-winning professor of physics and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory scientist, had been discussing the need for an undergraduate course on critical thinking with philosophy professor John Campbell for nearly a year when they both agreed that they needed a third perspective — that of a social psychologist. They approached Robert MacCoun , then a UC Berkeley professor of public policy and law who is now at Stanford Law School, and he was all in.

The three authors will get together to discuss the book at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco on Thursday, March 28.

The course, now co-taught with Amy Lerman , UC Berkeley professor of public policy and political science, currently enrolls 300 students for Zoom lectures and additional smaller, in-person discussion sections. Courses based on the UC Berkeley curriculum have been adopted at Harvard University and UC Irvine, and, this spring, by the University of Chicago. A high school course is currently being developed and classroom-tested as well. Berkeley News sat down with Perlmutter, Campbell and MacCoun to discuss the book and why the world needs a science-based approach to critical thinking and decision making.

Berkeley News : Why the need for such a course and your new book?

Saul Perlmutter : There was a period, back in 2012 or thereabouts, when we were watching our government at the time try to make rational decisions, and it just looked so unlike a lunch table conversation among a bunch of scientists. They weren’t using the same vocabulary, the same terms, the same approaches to a problem. At the time, I was thinking, “When did scientists learn this stuff?” I realized it wasn’t in any science course that I had ever taken. It just somehow seemed to be taught by osmosis, by going through research training. So I asked, “Is there any way that we could articulate what those concepts are that scientists were using and taking for granted at the lunch table, and try to teach it to everybody?” That was one of the starting points.

But you know, if you go to a physics faculty meeting, it doesn’t necessarily run much more rationally than any other faculty meeting. We had to bring in other expertise, and the obvious ones were social science and philosophy. Social psychology brought in the idea that when groups get together, they’re not thinking what they think they’re thinking — there are many known failings in individual and group thinking, and ways to do better. And then philosophy brought in all the questions of: How do we weigh different elements of decision-making against each other, topics like how to weave in the values, fears and goals that drive a decision? What is the role of experts in a democracy?”

John Campbell : Saul just rung me out of the blue and said, “Do you want to talk about this?” What came into focus for me in our conversations was how much uncertainty people have about what the place is of science in our society. It often seems, to me anyway, to be regarded as a kind of magic — of course, they can do anything these days. They can put robots into your bloodstream and make you do what they like. The only question is what their motivations are, and what are they up to.

It seems to me that we all need to have more of a sense of what science can do, what its possibilities and limitations are. That scientists can’t just magic up anything, they have techniques we can use ourselves in everyday life.

Rob MacCoun : I was delighted when Saul described this course to me and said, “Would you be interested?” I said, “Absolutely.” I had been doing empirical work on a lot of really hot-button issues — gays in the military and drug legalization, being two of them — and had despaired over the amount of bias in the interpretation and use of research evidence.

Saul Perlmutter : After we had been talking a little bit, we put up a sign saying: Are you embarrassed watching our society make decisions? Come help invent a course, come help save the world. And about 30 students, mostly grad students and postdocs, came forward. We met every week for about nine months. We came up with 23 topics and exercises designed to teach these topics experientially in a way that people could remember them and use them whenever they came across the need, not just in their own field. Over the years, we’ve tried to get as many of those into the course as we could.

BN: In your book you have chapters on many of these topics: how not to confuse correlation with causation; thinking in terms of probability, not certainty; admitting and controlling for your biases; not being afraid to admit you’re wrong. You argue that these aren’t only useful in the sciences.

MacCoun : This is not a book that says, “Here are the most important findings in science.” It’s also not even about the scientific method, although we do teach some of that. It really is about things that are part of science culture that nobody talks about explicitly, habits that people just pick up. It’s not unique to the natural sciences. I think social scientists, partly through imitation, have also learned a lot of those things. That’s because science is a profession where you have to work with people who disagree with you about something, and you can’t just say, “OK, we agree to disagree.” You believe that there actually is an answer out there. And while both sides think they’re more likely to have the right one, they agree there is a right answer to be found. And both sides want to know how: Can we at least get closer to the right answer?

Aditya Ranganathan, UC Berkeley

That original group was mostly from the sciences. We had this workshop for the first summer, just trying to imagine what such a class would look like, trying to come up with exercises. I have to say, that’s the most preparation I’ve ever put into any course I’ve ever taught. But it paid off because the first time we taught it, it was very well received by the students, and we felt like, “Oh, this is something distinctive.”

Saul Perlmutter : I remember at the time I was thinking that these were things that scientists seemed to know, but that most of society did not seem to know. And so maybe we should be teaching non-scientists the material. But then I realized, actually, scientists also need to learn it much younger. I should have learned it as an undergraduate or even as a high school student, not waiting until I learned it by osmosis in graduate school.

Campbell : There’s something about recognizing, as Rob says, that there’s an objective fact that we’re trying to get to. But the flip side of that is recognizing that, OK, we’re finite humans, maybe we can only get to the facts probabilistically. We can put weights on the objective facts, we can say this is far more likely than that, but you always have to accept the possibility of you being in error about those facts. If we could all recognize that however strong a hunch we have that this thing is right, there is always room for error, it would greatly facilitate debate across divides. At the same time, there is something out there, and it’s worth fighting about how we get it right.

MacCoun : If you’re trying to actually solve problems in the world, in the empirical world, science is the best game in town, and it’s got a proven track record. We want this book to be for the general public. We feel evangelical about it — why doesn’t everybody know about this stuff? We hope it will get readers.

BN: Is there something about the current time — the new century and the beginning of the third millennium — that makes this more important now?

Perlmutter : There’s a mix of things that are making this a particularly fertile time for this book. One is, there’s so much information out there that you can’t actually teach science anymore that’s intended to be comprehensive. Once upon a time, most educated people knew most of science, or at least what science was known at the time. But now I think it’s almost impossible. But what you can do is you can teach the elements that go into scientific thinking so that when you go to a YouTube video or read an article, you have some way of judging what’s being done and whether it’s being done in a way that meets these standards of thought.

Steven Zeng and Brian Delahunty, UC Berkeley

Toward the end of the book, Rob and John, I think, captured well the sense in which the world has moved from being very authoritative, where a single person is the genius who makes some discovery, to a world now where there’s a much deeper understanding of how authority is a community process. In some sense, we’re ripe for this. So at the same time that some aspects of societal thinking have broken down lately, other aspects have advanced dramatically, and I think we’ve come to a much better place in understanding how people can figure things out together.

Campbell : Something else that wasn’t here 100 years ago is just the sheer volume of the ways that science is impacting everyday life. I mean, you can’t really do a book on decision-making that’s going to apply at all, really, to most decisions you make without having some sense of where science should be factoring into your decisions. There is practically nothing that is free of some scientific aspect or where science can’t be of some help in decision-making. But you really need a good sense of what the science is about, what its scope and limits are, where you might plug it in, and how it integrates with values.

Perlmutter : We’re not saying, “Give up on experts.” Look carefully at how the experts are presenting and choose your experts well. Choose them based on a self-critical willingness to change their mind and willingness to state things tentatively when necessary or strongly when needed.

Campbell : As humans, we crave certainty. It’s so appealing when politicians express themselves with full conviction about everything. One thing we should be looking for in politicians is that openness to the possibility of error. This is a perplexing and confusing world, and it is so agreeable and comforting when someone says, “I can lead you through all this.” We have to learn not to do that and to live with the bewilderment.

MacCoun : We try to convey a pair of attitudes that people usually don’t think of together. One is skepticism, as opposed to gullibility, and the importance of cultivating a sense of skepticism. But the other is optimism, as opposed to pessimism. I think Saul was the first person I ever heard say that, you know, most scientists assume that every problem does have a solution, that we will find a solution. We talk about skepticism as the brake pedal and optimism as the gas pedal. If you want to get somewhere, you need both pedals.

BN: I like that, in your book, you talk not only about how to make rational, fact-based decisions individually, but also how to work with other people to come to a consensus when not everyone shares the same values.

Perlmutter : The course could have just stopped with teaching you how to think rationally together. But we decided to incorporate rational thinking with all the other parts that go into a decision, like the values and the goals and the fears and the ambitions. If you don’t come up with some organized, principled way to incorporate all those things together with rationality, we know which parts are going to get lost. It’s not going to be the fears and the goals and the ambitions. It’s going to be the rationality. So if you care about the rationality, then we felt you had to care about what it looks like when you try to weave that together with the values and goals and fears.

Campbell : I think there’s something really awful about the way that we all in Anglo-American society think about values. We think, well, science tells you the objective facts, but science doesn’t tell you anything about values. Therefore, the values are all very subjective. Once we’ve agreed that it’s all very subjective, there’s really no debate possible. All I can do if I think abortion is very wrong, for example, is get a majority on my side and force you to recognize my values. Discussion is impossible. It seems to me that it’s just such an unhelpful way to think about values, given that we do have these opposed values in our society. We actually need the same kind of approach to value that we take to scientific facts.

Perlmutter : You see in history that people have actually moved each other’s understanding about what their values are. Slavery, at one point, would not have been seen the way it is today. And yet, now people have a shared a view of it.

MacCoun : It gets very muddled if you don’t distinguish facts and values. But there are ways of bringing them together in an analysis without just throwing your hands up. A lot of scientists, when they weigh in on public policy, haven’t really thought through some of this stuff, and they’ll just kind of weigh in with what’s basically just a value, but use the mantle of science. In the book, we talk about how it’s not enough to have all these habits of mind that scientists have unless you are in a community that will call you on your B.S.

Perlmutter : One thing that we highlight in the book is the idea that the particularly extreme inability to actually have a conversation that you often see in Congress — at least as presented to the public — is not necessarily the case for the whole society. I think if you take a random group of people in the public, they may disagree on a topic, but if brought into a conversation, they could actually have a conversation about it and try to figure out where the issue is coming from and maybe change their minds about certain topics, which seems to happen when you do these deliberative polls.

MacCoun : Part of the excitement of the book is that there are a lot of new ideas and innovations happening in that space of group decision-making. You have deliberative polling, the idea of don’t just poll people individually, but bring them together and have them talk together. And we talk about scenario planning. We talk about citizen forecasting methods that can outperform professional forecasters. And we talk about new open science models, where you pre-register your hypotheses, and open data. These ideas aren’t static, they’re developing all the time. And that’s part of what where the third millennium idea comes in. We’re getting collectively better at this stuff all the time.

BN: In reading about the process of collective decision-making — techniques such as deliberative polling, scenario planning and collective forecasting — it seems like an exhausting way to reach agreement.

MacCoun : It’s hard work, and I don’t think we’re glib in the book about this being necessarily easy. Conflict isn’t necessarily bad. Conflict can be ferocious and still be very productive, if you do it the right way. If you actually want to do things in the world, you’re going to have to, ultimately, sit down and talk to people that disagree with you.

Campbell : One of the revelations of social psychology is that we’re not bad at spotting biases in each other, but we are terrible at spotting our own biases. It’s just so important to try to create a world where it’s common knowledge that we’re all blind to our own biases, and that it really helps to have someone else around who could pick you up, who could check you on your biases. We have so much in our own heads orienting us in the wrong directions that we really need to clear that up a bit.

BN: But no one likes to be told that they’re wrong.

Perlmutter: That’s actually one of the reasons that we thought that there’s an extra advantage of the probabilistic style of thinking as a way of make sure you capture the information that’s really there without rounding everything off to be true or false. Many things we don’t know, but we do have a pretty good guess that it’s 85% likely to be true. And there’s an extra psychological advantage, which is that if you are committed to presenting all your findings as a probabilistic finding, then you don’t have your ego wrapped up in being right every time.

MacCoun : The problem is that the market rewards experts for overconfidence. I’ve been an expert witness in some of the trials involving gays in the military, and I was really pressed not to hem and haw and just tell me yes or no. I can’t do that.

We’re approaching an election, and we talk in the book about maybe we should start rewarding politicians for being straight with us. Little children find it very reassuring when their parents are all-knowing, but people of voting age are adults, and maybe we should recognize that politicians are not all-knowing. The ones who tell us, “I’m not sure, but this is my best bet,” or go a step further and say, “And if it turns out I’m wrong, I’ll change my mind and here’s my backup plan” — maybe those are the people we should be rewarding.

Campbell : You want to encourage conflict. Conflict is good. That’s the point of free speech. We have different ideas, we try to figure which one is right. Which ones are closer to the truth. But it’s hard to do that without getting inappropriately engaged. Freud had a word for it, cathexis, where your sexual identity becomes involved in maintaining the views that you’ve picked up, and it’s very difficult to let go of the thing. What we need is to have the debate, but have it judged in impersonal terms.

BN: Courses on the scientific method, critical thinking and decision-making are not new. How does your class and book differ from these?

MacCoun : Our book certainly overlaps with two very older traditions: courses or popular books on decision-making, and courses or popular books on critical thinking. Both elements are in our book, but a couple of things are distinctive about our book. It’s inherently interdisciplinary, given the nature of the authors, but we also feel like when people focus on decision-making or critical thinking, they just focus on the individual thinker, and they don’t really capture that that’s not enough. Even people who know about all these biases are still subject to these biases. It’s not enough to just do well as an individual. You really have to cultivate a community to make it stick.

BN: Your book ends on an optimistic note: that we can, in the third millennium, become more collaborative in our problem-solving.

MacCoun : The third millennium is very long. We gave ourselves lots of room to accomplish this.

Campbell : But that is the ideal of society. Everybody knows how to go about deliberating, how to go about discussion, as opposed to thinking they’ve got to win a majority and then bully the other side into submission. That’s really not a good way to go. That leaves you thinking about, “I’ve gotta use guns, because if debate is not possible, then agreement is not possible.”

Perlmutter : One of the things in science that seems to have been very effective is that it really sharpens your thinking when somebody is disagreeing with you. It’s very hard to see your own blind spots if all you have are people who share all your views. You actually should want to find the other party and have a discussion with them. But in this particular configuration that we’re looking at right now, it’s scary — it doesn’t feel like people are comfortable hearing somebody disagree with them and actually thinking, okay, is there something there that I’m missing that I could benefit from.

Take climate change. Climates change all the time, so whether or not we are the ones who started it — though we apparently have started this round — we have to deal with it one way or the other, and now we have to deal with it faster. I think we are perfectly capable of dealing with if we have some conversation and get people to sharpen up their ideas and work together. But it’s very hard to do it when everything is seen as a fight to the death or of not doing something that the other side wants.

BN: What do you hope to achieve with this book?

Perlmutter : In my mind, if people read the book and start to work together in the style that we’re advocating, I would feel much, much safer in the world we live in. I think it would be a noisy, argumentative world, as it should be — people will be trying to figure things out and arguing with each other, but they would be arguing with each other with the goal of actually solving problems together. And they would be, in the end, gaining a much sharper understanding of the reality in which we live. Groups of people, when well-structured, are amazingly capable. All the big concerns you might have about threats of climate change or pandemics or whatever, those are at just the scale that humans are today likely to be good at solving, if given the chance to actually talk together and try to make decisions together.

Campbell : Humans are fundamentally cooperative, though fundamentally tribal. What we need is to have a space where cooperation can happen between people with radically dissimilar views. That’s really the dream.

MacCoun : The U.S. military has learned this. There was tremendous anxiety about allowing gays and lesbians in the circle of military units. The concern was units are just going to fall apart because of differences in lifestyle choices, that the unit will disintegrate. And of course, that’s not at all what happened when they lifted the ban, because people had a shared sense of commitment to the overriding mission. To make a better society, you’ve got to have that shared sense of mission. If you have a shared desire to get somewhere for your community, but radically different ideas on how to get there, you can work it out. There’s lots of examples where people managed to work it out.

The News Literacy Project

Using the news to develop students’ critical thinking

Published on March 10, 2022 Updates

Pamela Brunskill

By Pamela Brunskill

Students today are immersed in a news and information landscape that pervades every aspect of their lives. From TikTok to Instagram to Twitter, they are inundated with posts, and many of them are not credible or legitimately grounded. It is difficult to know what is true. Because this environment is complex and riddled with misinformation, it provides a prime opportunity to authentically develop students’ critical thinking abilities.

Critical thinking defined

One of the most highly sought goals of educators is to get students to think critically. In a rough sense, this involves the skills and dispositions necessary to make an informed judgment. According to a meta-analysis on the subject, critical thinking is purposeful, methodical, and habitually inquisitive. Critical thinkers have the skills to interpret, analyze, and evaluate content; they are diligent and persistent in considering a question, and they approach life honestly and with an open mind.

While there is some debate whether the best approach to teaching critical thinking is through generic traits or through discipline-specific skills, a compromised approach allows students to develop both . If we follow the belief that students need context to accurately reason about a subject, then they must have some background knowledge in that subject. How else can they think critically about something? Further, how would that naive thinking compare to that of experts in the field? Regarding the news and information landscape, if students are going to think critically and be discerning with the content they share, then they must learn news literacy.

How to use news literacy to teach critical thinking

Step 1: develop disciplinary literacy in the news.

In an era of misinformation, students can evaluate information by learning how news is made. This includes explicit instruction in concepts and content such as identifying different types of information, recognizing the purpose or intent of pieces, understanding the watchdog role of the press, and recognizing quality arguments and evidence. It also includes explicit instruction of skills such as evaluating sources, identifying branded content, recognizing bias and motivated reasoning, and verifying evidence. Of course, students also need to demonstrate understanding of these concepts and practice these skills. In so doing, they gain disciplinary literacy, the notion of specialized reading practices for a field of study. Often, disciplinary literacy is framed as thinking like a mathematician, a historian , or a computer programmer . Regardless of the content area, students gain greater depth in their understanding of the underpinnings of that discipline. In this case, students learn to “think like a journalist.”

Example of developing disciplinary literacy: Jennifer Liang Twitter thread

Step 2: Teach topical content

Once students comprehend how news is made, they can deconstruct it and analyze its creation. But they also need the context surrounding the piece of news they’re reading and/or studying. To this end, teachers should provide explicit instruction in the topic at hand, whether it involves immigration, global warming, sports, health, statistics, or any other content area. This is where each discipline offers its own guidance, and as with all good teaching, this requires an effective approach to tackling reading comprehension . This might include studying vocabulary, writing about text through think sheets and short responses, and discussions, among other strategies. Then, students can explain a disciplinary concept such as immigration and explain why not all images of border walls are accurately portrayed in memes.

Why news literacy?

Of course, integrated studies between all subjects are possible, but there is a special partnership between English and social studies in relation to news literacy. The stakes are high: think about the consequences of misinformation as well as the potential for civic action. A lack of news literacy threatens democracy and our public health — just look at the conspiratorial thinking that led to the Capitol riots and erroneous claims about COVID-19 . Conversely, when individuals have the competency to judge reliable and credible news, they can take civic action such as correcting a piece of misinformation, contacting elected officials, and participating responsibly in political discussions. Being accurately informed is crucial to participating in a democracy.

Example of disciplinary-specific content : Conspiratorial Thinking poster

Critical thinking is critical in today’s world

Using the news in classrooms can authentically develop higher-level thinking skills and dispositions. Combining understanding of how journalism works along with topical content allows students to determine the credibility of information they encounter. This integration enables students to interpret, analyze, evaluate, explain, and make judgments — to think critically. By teaching news literacy, we can teach students the skills and habits of mind to not only navigate today’s information landscape, but also to navigate our society.

More Updates

NLP’s News Literacy District Fellowship program expands across U.S.

The News Literacy Project has selected nine school districts to join its growing News Literacy District Fellowship program.

Published on Sep 9, 2024 Updates

Track the trends: Stay ahead of these election falsehoods

The News Literacy Project’s Misinformation Dashboard: Election 2024 so far contains more than 600 hundred examples of online falsehoods.

Published on Sep 5, 2024 Updates

Track the trends: Get to know the election dashboard

This blog post, part of a new limited series from the News Literacy Project, provides updates and analysis from the Misinformation Dashboard: Election 2024.

Published on Aug 29, 2024 Updates

Search Close

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Planet Money

- Planet Money Podcast

- The Indicator Podcast

- Planet Money Newsletter Archive

- Planet Money Summer School

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

How do you counter misinformation? Critical thinking is step one

Greg Rosalsky

Late last year, in the days before the Slovakian parliamentary elections, two viral audio clips threatened to derail the campaign of a pro-Western, liberal party leader named Michal Šimečka. The first was a clip of Šimečka announcing he wanted to double the price of beer, which, in a nation known for its love of lagers and pilsners, is not exactly a popular policy position.

In a second clip, Šimečka can be heard telling a journalist about his intentions to commit fraud and rig the election. Talk about career suicide, especially for someone known as a champion of liberal democracy.

There was, however, just one issue with these audio clips: They were completely fake.

The International Press Institute has called this episode in Slovakia the first time that AI deepfakes — fake audio clips, images, or videos generated by artificial intelligence — have played a prominent role in a national election. While it's unclear whether these bogus audio clips were decisive in Slovakia's electoral contest, the fact is Šimečka's party lost the election, and a pro-Kremlin populist now leads Slovakia.

In January, a report from the World Economic Forum found that over 1,400 security experts consider misinformation and disinformation (misinformation created with the intention to mislead) the biggest global risk in the next two years — more dangerous than war, extreme weather events, inflation, and everything else that's scary. There are a bevy of new books and a constant stream of articles that wrestle with this issue. Now even economists are working to figure out how to fight misinformation.

In a new study , "Toward an Understanding of the Economics of Misinformation: Evidence from a Demand Side Field Experiment on Critical Thinking," economists John A. List, Lina M. Ramírez, Julia Seither, Jaime Unda and Beatriz Vallejo conduct a real-world experiment to see whether simple, low-cost nudges can be effective in helping consumers to reject misinformation. (Side note: List is a groundbreaking empirical economist at the University of Chicago, and he's a longtime friend of the show and this newsletter ).

While most studies have focused on the supply side of misinformation — social media platforms, nefarious suppliers of lies and hoaxes, and so on — these authors say much less attention has been paid to the demand side: increasing our capacity, as individuals, to identify and think critically about the bogus information that we may encounter in our daily lives.

A Real-Life Experiment To Fight Misinformation

The economists conducted their field experiment in the run-up to the 2022 presidential election in Colombia. Like the United States, Colombia is grappling with political polarization. Within a context of extreme tribalism, the authors suggest, truth becomes more disposable and the demand for misinformation rises. People become willing to believe and share anything in their quest for their political tribe to win.

To figure out effective ways to lower the demand for misinformation, the economists recruited over 2,000 Colombians to participate in an online experiment. These participants were randomly distributed into four different groups.

One group was shown a video demonstrating "how automatic thinking and misperceptions can affect our everyday lives." The video shows an interaction between two people from politically antagonistic social groups who, before interacting, express negative stereotypes about the other's group. The video shows a convincing journey of these two people overcoming their differences. Ultimately, they express regret over unthinkingly using stereotypes to dehumanize one another. The video ends by encouraging viewers to question their own biases by "slowing down" their thinking and thinking more critically.

Another group completed a "a personality test that shows them their cognitive traits and how this makes them prone to behavioral biases." The basic idea is they see their biases in action and become more self-aware and critical of them, thereby decreasing their demand for misinformation.

A third group both watched the video and took the personality test.

Finally, there was a control group, which neither watched the video nor took the personality test.

To gauge whether these nudges get participants to be more critical of misinformation, each group was shown a series of headlines, some completely fake and some real. Some of these headlines leaned left, others leaned right, and some were politically neutral. The participants were then asked to determine whether these headlines were fake. In addition, the participants were shown two untrue tweets, one political and one not. They were asked whether they were truthful and whether they would report either to social media moderators as misinformation.

What They Found

The economists find that the simple intervention of showing a short video of people from politically antagonistic backgrounds getting along inspires viewers to be more skeptical of and less susceptible to misinformation. They find that participants who watch the video are over 30 percent less likely to "consider fake news reliable." At the same time, the video did little to encourage viewers to report fake tweets as misinformation.

Meanwhile, the researchers find that the personality test, which forces participants to confront their own biases, has little or no effect on their propensity to believe or reject fake news. It turns out being called out on our lizard brain tribalism and other biases doesn't necessarily improve our thinking.

In a concerning twist, the economists found that participants who both took the test and watched the video became so skeptical that they were about 31 percent less likely to view true headlines as reliable. In other words, they became so distrustful that even the truth became suspect. As has become increasingly clear, this is a danger in the new world of deepfakes: not only do they make people believe untrue things, they also may make people so disoriented that they don't believe true things.

As for why the videos are successful in helping to fight misinformation, the researchers suggest that it's because they encourage people to stop dehumanizing their political opponents, think more critically, and be less willing to accept bogus narratives even when it bolsters their political beliefs or goals. Often — in a sort of kumbaya way — centrist political leaders encourage us to recognize our commonalities as fellow countrymen and work together across partisan lines. It turns out that may also help us sharpen our thinking skills and improve our ability to recognize and reject misinformation.

Critical Thinking In The Age Of AI

Of course, this study was conducted back in 2022. Back then, misinformation, for the most part, was pretty low-tech. Misinformation may now be getting turbocharged with the rapid proliferation and advancement of artificial intelligence.

List and his colleagues are far from the first scholars to suggest that helping us become more critical thinkers is an effective way to combat misinformation. University of Cambridge psychologist Sander van der Linden has done a lot of work in the realm of what's known as "psychological inoculation," basically getting people to recognize how and why we're susceptible to misinformation as a way to make us less likely to believe it when we encounter it. He's the author of a new book called Foolproof: Why Misinformation Infects Our Minds and How to Build Immunity . Drawing an analogy to how vaccinations work, Van der Linden advocates exposing people to misinformation and showing how it's false as a way to help them spot and to reject misinformation in the wild. He calls it "prebunking" (as in debunking something before it happens).

Of course, especially with the advent of AI deepfakes, misinformation cannot only be combated on the demand side. Social media platforms, AI companies, and the government will all likely have to play an important role. There's clearly a long way to go to overcoming this problem, but we have recently seen some progress. For example, OpenAI recently began "watermarking" AI-generated images that their software produces to help people spot pictures that aren't real. And the federal government recently encouraged four companies to create new technologies to help people distinguish between authentic human speech and AI deepfakes.

This new world where the truth is harder to believe may be pretty scary. But, as this new study suggests, nudges and incentives to get us to slow our thinking, think more critically, and be less tribal could be an important part of the solution.

- misinformation

When critical thinking isn’t enough: to beat information overload, we need to learn ‘critical ignoring’

Director, Center for Adaptive Rationality, Max Planck Institute for Human Development

Cognitive scientist, Max Planck Institute for Human Development

Professor of Education and (by courtesy) History, Stanford University

Chair of Cognitive Psychology, University of Bristol

Disclosure statement

Ralph Hertwig receives funding from the Volkswagen Foundation and the European Commission (HORIZON 2022 grant GA 101094752). He has collaborated with researchers in the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission.

Stephan Lewandowsky receives funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 964728 (JITSUVAX). He also receives funding from Jigsaw (a technology incubator created by Google), from UK Research and Innovation (through the Centre of Excellence, REPHRAIN), and from the Volkswagen Foundation in Germany. He also holds a European Research Council Advanced Grant (no. 101020961, PRODEMINFO) and receives funding from the John Templeton Foundation (via Wake Forest University’s Honesty Project). He has worked with the European Commission on issues relating to social media governance and regulation.

Anastasia Kozyreva and Sam Wineburg do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Bristol provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

The web is an informational paradise and a hellscape at the same time. A boundless wealth of high-quality information is available at our fingertips right next to a ceaseless torrent of low-quality, distracting, false and manipulative information.

The platforms that control search were conceived in sin. Their business model auctions off our most precious and limited cognitive resource: attention. These platforms work overtime to hijack our attention by purveying information that arouses curiosity, outrage, or anger. The more our eyeballs remain glued to the screen, the more ads they can show us, and the greater profits accrue to their shareholders.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, all this should take a toll on our collective attention. A 2019 analysis of Twitter hashtags, Google queries, or Reddit comments found that across the past decade, the rate at which the popularity of items rises and drops has accelerated. In 2013, for example, a hashtag on Twitter was popular on average for 17.5 hours, while in 2016, its popularity faded away after 11.9 hours. More competition leads to shorter collective attention intervals, which lead to ever fiercer competition for our attention – a vicious circle.

To regain control, we need cognitive strategies that help us reclaim at least some autonomy and shield us from the excesses, traps and information disorders of today’s attention economy.

Critical thinking is not enough

The textbook cognitive strategy is critical thinking , an intellectually disciplined, self-guided and effortful process to help identify valid information. In school, students are taught to closely and carefully read and evaluate information. Thus equipped, they can evaluate the claims and arguments they see, hear, or read. No objection. The ability to think critically is immensely important.

But is it enough in a world of information overabundance and gushing sources of disinformation? The answer is “No” for at least two reasons.

First, the digital world contains more information than the world’s libraries combined. Much of it comes from unvetted sources and lacks reliable indicators of trustworthiness. Critically thinking through all information and sources we come across would utterly paralyse us because we would never have time to actually read the valuable information we painstakingly identify.

Second, investing critical thinking in sources that should have been ignored in the first place means that attention merchants and malicious actors have been gifted what they wanted, our attention.

Critical ignoring to make information management feasible

So, what tools do we have at our disposal beyond critical thinking? In our recent article , we – a philosopher, two cognitive scientists and an education scientist – argue that as much as we need critical thinking we also need critical ignoring .

Critical ignoring is the ability to choose what to ignore and where to invest one’s limited attentional capacities. Critical ignoring is more than just not paying attention – it’s about practising mindful and healthy habits in the face of information overabundance.

We understand it as a core competence for all citizens in the digital word.

Without it, we will drown in a sea of information that is, at best, distracting and, at worst, misleading and harmful.

Tools for critical ignoring

Three main strategies exist for critical ignoring. Each one responds to a different type of noxious information.

In the digital world, self-nudging aims to empower people to be citizen “choice architects” by designing their informational environments in ways that work best for them and that constrain their activities in beneficial ways. We can, for instance, remove distracting and irresistible notifications. We may set specific times in which messages can be received, thereby creating pockets of time for concentrated work or socialising. Self-nudging can also help us take control of our digital default settings, for instance, by restricting the use of our personal data for purposes of targeted advertisement.

Lateral reading is a strategy that enables people to emulate how professional fact checkers establish the credibility of online information . It involves opening up new browser tabs to search for information about the organisation or individual behind a site before diving into its contents. Only after consulting the open web do skilled searchers gauge whether expending attention is worth it. Before critical thinking can begin, the first step is to ignore the lure of the site and check out what others say about its alleged factual reports. Lateral reading thus uses the power of the web to check the web.

Most students fail at that task. Past studies show that, when deciding whether a source should be trusted, students (as well as university professors ) do what years of school has taught them to do – they read closely and carefully. Attention merchants as well as merchants of doubt are jubilant.

Online, looks can be deceiving. Unless one has extensive background knowledge it is often very difficult to figure out that a site, filled with the trappings of serious research, peddles falsehoods about climate change or vaccinations or any variety of historical topics, such as the Holocaust. Instead of getting entangled in the site’s reports and professional design, fact checkers exercise critical ignoring. They evaluate the site by leaving it and engage in lateral reading instead.

500,000+ people get our newsletters. Join them, subscribe now .

The do-not-feed-the-trolls heuristic targets online trolls and other malicious users who harass, cyberbully or use other antisocial tactics. Trolls thrive on attention, and deliberate spreaders of dangerous disinformation often resort to trolling tactics. One of the main strategies that science denialists use is to hijack people’s attention by creating the appearance of a debate where none exists . The heuristic advises against directly responding to trolling. Resist debating or retaliating. Of course, this strategy of critical ignoring is only a first line of defence. It should be complemented by blocking and reporting trolls and by transparent platform content moderation policies including debunking.

These three strategies are not a set of elite skills. Everybody can make use of them, but educational efforts are crucial for bringing these tools to the public.

Critical ignoring as a new paradigm for education

The philosopher Michael Lynch has noted that the Internet “is both the world’s best fact-checker and the world’s best bias confirmer – often at the same time.”

Navigating it successfully requires new competencies that should be taught in school. Without the competence to choose what to ignore and where to invest one’s limited attention, we allow others to seize control of our eyes and minds. Appreciation for the importance of critically ignoring is not new but has become even more crucial in the digital world.

As the philosopher and psychologist William James astutely observed at the beginning of the 20th century: “The art of being wise is the art of knowing what to ignore.”

- Neuroscience

- Social networks

- Misinformation

- Disinformation

- Concentration

- information overload

- Attention economy

- Information age

- Online misinformation

- The Conversation Europe

- Mental workload

University Relations Manager

2024 Vice-Chancellor's Research Fellowships

Head of Research Computing & Data Solutions

Community member RANZCO Education Committee (Volunteer)

Director of STEM

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Over 170 Prompts to Inspire Writing and Discussion

Here are all of our Student Opinion questions from the 2020-21 school year. Each question is based on a different New York Times article, interactive feature or video.

By The Learning Network

Each school day we publish a new Student Opinion question, and students use these writing prompts to reflect on their experiences and identities and respond to current events unfolding around them. To introduce each question, we provide an excerpt from a related New York Times article or Opinion piece as well as a free link to the original article.

During the 2020-21 school year, we asked 176 questions, and you can find them all below or here as a PDF . The questions are divided into two categories — those that provide opportunities for debate and persuasive writing, and those that lend themselves to creative, personal or reflective writing.

Teachers can use these prompts to help students practice narrative and persuasive writing, start classroom debates and even spark conversation between students around the world via our comments section. For more ideas on how to use our Student Opinion questions, we offer a short tutorial along with a nine-minute video on how one high school English teacher and her students use this feature .

Questions for Debate and Persuasive Writing

1. Should Athletes Speak Out On Social and Political Issues? 2. Should All Young People Learn How to Invest in the Stock Market? 3. What Are the Greatest Songs of All Time? 4. Should There Be More Gender Options on Identification Documents? 5. Should We End the Practice of Tipping? 6. Should There Be Separate Social Media Apps for Children? 7. Do Marriage Proposals Still Have a Place in Today’s Society? 8. How Do You Feel About Cancel Culture? 9. Should the United States Decriminalize the Possession of Drugs? 10. Does Reality TV Deserve Its Bad Rap? 11. Should the Death Penalty Be Abolished? 12. How Should Parents Support a Student Who Has Fallen Behind in School? 13. When Is It OK to Be a Snitch? 14. Should People Be Required to Show Proof of Vaccination? 15. How Much Have You and Your Community Changed Since George Floyd’s Death? 16. Can Empathy Be Taught? Should Schools Try to Help Us Feel One Another’s Pain? 17. Should Schools or Employers Be Allowed to Tell People How They Should Wear Their Hair? 18. Is Your Generation Doing Its Part to Strengthen Our Democracy? 19. Should Corporations Take Political Stands? 20. Should We Rename Schools Named for Historical Figures With Ties to Racism, Sexism or Slavery? 21. How Should Schools Hold Students Accountable for Hurting Others? 22. What Ideas Do You Have to Improve Your Favorite Sport? 23. Are Presidential Debates Helpful to Voters? Or Should They Be Scrapped? 24. Is the Electoral College a Problem? Does It Need to Be Fixed? 25. Do You Care Who Sits on the Supreme Court? Should We Care? 26. Should Museums Return Looted Artifacts to Their Countries of Origin? 27. Should Schools Provide Free Pads and Tampons? 28. Should Teachers Be Allowed to Wear Political Symbols? 29. Do You Think People Have Gotten Too Relaxed About Covid? 30. Who Do You Think Should Be Person of the Year for 2020? 31. How Should Racial Slurs in Literature Be Handled in the Classroom? 32. Should There Still Be Snow Days? 33. What Are Your Reactions to the Storming of the Capitol by a Pro-Trump Mob? 34. What Do You Think of the Decision by Tech Companies to Block President Trump? 35. If You Were a Member of Congress, Would You Vote to Impeach President Trump? 36. What Would You Do First if You Were the New President? 37. Who Do You Hope Will Win the 2020 Presidential Election? 38. Should Media Literacy Be a Required Course in School? 39. What Are Your Reactions to the Results of Election 2020? Where Do We Go From Here? 40. How Should We Remember the Problematic Actions of the Nation’s Founders? 41. As Coronavirus Cases Surge, How Should Leaders Decide What Stays Open and What Closes? 42. What Is Your Reaction to the Inauguration of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris? 43. How Worried Should We Be About Screen Time During the Pandemic? 44. Should Schools Be Able to Discipline Students for What They Say on Social Media? 45. What Works of Art, Culture and Technology Flopped in 2020? 46. How Do You Feel About Censored Music? 47. Why Do You Think ‘Drivers License’ Became Such a Smash Hit? 48. Justice Ginsburg Fought for Gender Equality. How Close Are We to Achieving That Goal? 49. How Well Do You Think Our Leaders Have Responded to the Coronavirus Crisis? 50. To What Extent Is the Legacy of Slavery and Racism Still Present in America in 2020? 51. How Should We Reimagine Our Schools So That All Students Receive a Quality Education? 52. How Concerned Do You Think We Should Be About the Integrity of the 2020 Election? 53. What Issues in This Election Season Matter Most to You? 54. Is Summer School a Smart Way to Make Up for Learning Lost This School Year? 55. What Is Your Reaction to the Senate’s Acquittal of Former President Trump? 56. What Is the Worst Toy Ever? 57. How Should We Balance Safety and Urgency in Developing a Covid-19 Vaccine? 58. What Are Your Reactions to Oprah’s Interview With Harry and Meghan? 59. Should the Government Provide a Guaranteed Income for Families With Children? 60. Should There Be More Public Restrooms? 61. Should High School-Age Basketball Players Be Able to Get Paid? 62. Should Team Sports Happen This Year? 63. Who Are the Best Musical Artists of the Past Year? What Are the Best Songs? 64. Should We Cancel Student Debt? 65. How Closely Should Actors’ Identities Reflect the Roles They Play? 66. Should White Writers Translate a Black Author’s Work? 67. Would You Buy an NFT? 68. Should Kids Still Learn to Tell Time? 69. Should All Schools Teach Financial Literacy? 70. What Is Your Reaction to the Verdict in the Derek Chauvin Trial? 71. What Is the Best Way to Stop Abusive Language Online? 72. What Are the Underlying Systems That Hold a Society Together? 73. What Grade Would You Give President Biden on His First 100 Days? 74. Should High Schools Post Their Annual College Lists? 75. Are C.E.O.s Paid Too Much? 76. Should We Rethink Thanksgiving? 77. What Is the Best Way to Get Teenagers Vaccinated? 78. Do You Want Your Parents and Grandparents to Get the New Coronavirus Vaccine? 79. What Is Your Reaction to New Guidelines That Loosen Mask Requirements? 80. Who Should We Honor on Our Money? 81. Is Your School’s Dress Code Outdated? 82. Does Everyone Have a Responsibility to Vote? 83. How Is Your Generation Changing Politics?

Questions for Creative and Personal Writing

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

More From Forbes

Critical thinking skills not emphasized by most middle school teachers.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Students raise their hands to answer a teacher's question at the KIPP Academy in the South Bronx, ... [+] part of a network of public middle schools that is becoming a model for educating poor children. KIPP — which stands for Knowledge is Power Program — institutions are rigorous college preparatory schools where both students and their parents must sign a contract pledging long hours, extra homework, summer school, and excellent attendance records. Using strict discipline with highly motivated — and paid — teachers, the KIPP program has proven that public education can work. In the Bronx, the school has a famous music program, where children practice the songs of Lauryn Hill and Alicia Keys. (Photo by Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images)

Recent events show that there has never been a more crucial time for critical thinking. A global onslaught of misinformation, social media saturation, partisan politics, and science skepticism continuously challenge how information is shared, understood, and how it influences the decisions people make.

Research from the Reboot Foundation and others show that an overwhelming majority of the population recognizes the importance of critical thinking skills in today’s modern society. From parents to employers, there is near unanimous support for the teaching of critical skills in American classrooms, yet new national survey data shows schools may not be teaching those skills often enough.

A new Reboot paper, Teaching Critical Thinking in K-12: When There’s A Will But Not Always A Way , examines the U.S. Department of Education’s National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) and found that the teaching of critical thinking skills is inconsistent across states and tends to drop as students get older.

Among some of the key findings from NAEP:

- While 86 percent of 4th grade teachers said they put “quite a bit” or “a lot of emphasis” on deductive reasoning, that figure fell to only 39 percent of teachers in 8th grade. Deductive reasoning is one of the key skills in critical thinking, as it requires students to take a logical approach to turning general ideas into specific conclusions.

- At the state level, the analysis found that only seven states had at least 50 percent of their 8th grade teachers report that they place “quite a bit or a lot of emphasis” on teaching their students to engage in deductive reasoning.

While the numbers themselves are cause for concern, the age range at which these statistics are being reported is equally concerning. Research shows that while critical thinking skills can be learned at any stage of life, the teen years are an opportune time to engage young people as their brains are developing strong cognitive abilities.

Best Travel Insurance Companies

Best covid-19 travel insurance plans.

These years are exactly when students should be building a strong foundation of critical thinking competencies that can last a lifetime. Developmental psychologists have noted that beginning at around age 13, adolescents can begin to acquire and apply formal logical rules and processes, if they are shown how. Yet the data shows that schools are largely failing to capitalize on this period, despite a desire by many educators to do so.

Per NAEP, nearly 90% of 4th grade teachers nationally said they put “quite a bit” or “a lot of emphasis” on deductive reasoning, only for that figure to fall to less than 40% of teachers in 8th grade – what issues are contributing to the drastic drop?

In 2020, Reboot surveyed teachers and found that many teachers harbored misconceptions about how to best teach critical thinking. The survey found that, among teachers, 42 percent reported that students should learn basic facts first, then engage in critical thinking practice, while an additional 16 percent said that they believed basic facts and critical thinking should be taught separately. This line of thinking is wrong, as research strongly suggests that critical thinking skills are best acquired in combination with the teaching of basic facts in a subject area.

This commonly-held misconception about when and how to teach critical thinking skills might be a clue as to why deductive reasoning instruction seems to tail off as students get older and take more specialized, content-driven classes. This might be made worse by the fact that eighth grade is a crucial year for many schools to show success under their state accountability measures.

In many states, students cannot move on to high school if they fail state exams in eighth grade. And things such as teacher pay, school funding and other “high-stakes” accountability measures often hinge on student performance in that grade. This pressure forces schools and teachers to focus on preparing their eighth graders for state exams in lieu of a more well-rounded educational experience. Indeed, our 2020 survey of teachers revealed that 55 percent believed that the emphasis on standardized testing made it more difficult to incorporate critical thinking instruction in their classrooms.

Reboot and others are working to identify ways teachers can implement critical thinking skills education into their curriculums more simply and efficiently. Among the stepping stones toward broader adoption are:

- A shared standard or consensus around critical thinking education that could contribute to more uniform and equitable teaching of these key skills nationwide.

- An easier way to broach critical thinking for a wide-ranging group of students. New research by Reboot and researchers from Indiana University explores innovative, inexpensive and scalable ways to teach critical thinking skills. The research found that educators and others can teach and hone essential critical thinking skills using a simple method that is easy to implement across diverse groups of students.

So even as the recent data from NAEP is disappointing on skills like deductive reasoning, it also shows where improvement needs to occur. What remains to be seen is the nation’s commitment to advancing critical thinking skills and its support for the educators, administrators and stakeholders working to knock down the challenges being faced. As NAEP and other surveys show, there is indeed a will to move forward with critical thinking skills education among teachers. Dedicated resources and consistent collaboration will be crucial to finding “the way.”

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Join The Conversation

One Community. Many Voices. Create a free account to share your thoughts.

Forbes Community Guidelines

Our community is about connecting people through open and thoughtful conversations. We want our readers to share their views and exchange ideas and facts in a safe space.

In order to do so, please follow the posting rules in our site's Terms of Service. We've summarized some of those key rules below. Simply put, keep it civil.

Your post will be rejected if we notice that it seems to contain:

- False or intentionally out-of-context or misleading information

- Insults, profanity, incoherent, obscene or inflammatory language or threats of any kind

- Attacks on the identity of other commenters or the article's author

- Content that otherwise violates our site's terms.

User accounts will be blocked if we notice or believe that users are engaged in:

- Continuous attempts to re-post comments that have been previously moderated/rejected

- Racist, sexist, homophobic or other discriminatory comments

- Attempts or tactics that put the site security at risk

- Actions that otherwise violate our site's terms.

So, how can you be a power user?

- Stay on topic and share your insights

- Feel free to be clear and thoughtful to get your point across

- ‘Like’ or ‘Dislike’ to show your point of view.

- Protect your community.

- Use the report tool to alert us when someone breaks the rules.

Thanks for reading our community guidelines. Please read the full list of posting rules found in our site's Terms of Service.

3 Simple Habits to Improve Your Critical Thinking

by Helen Lee Bouygues

Summary .

Too many business leaders are simply not reasoning through pressing issues, and it’s hurting their organizations. The good news is that critical thinking is a learned behavior. There are three simple things you can do to train yourself to become a more effective critical thinker: question assumptions, reason through logic, and diversify your thought and perspectives. They may sound obvious, but deliberately cultivating these three key habits of mind go a long way in helping you become better at clear and robust reasoning.

A few years ago, a CEO assured me that his company was the market leader. “Clients will not leave for competitors,” he added. “It costs too much for them to switch.” Within weeks, the manufacturing giant Procter & Gamble elected not to renew its contract with the firm. The CEO was shocked — but he shouldn’t have been.

Partner Center

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- PubMed/Medline

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Predicting everyday critical thinking: a review of critical thinking assessments.

1. Introduction

2. how critical thinking impacts everyday life, 3. critical thinking: skills and dispositions.

“the use of those cognitive skills and abilities that increase the probability of a desirable outcome. It is used to describe thinking that is purposeful, reasoned, and goal directed—the kind of thinking involved in solving problems, formulating inferences, calculating likelihoods, and making decisions” ( Halpern 2014, p. 8 ).

4. Measuring Critical Thinking

4.1. practical challenges, 4.2. critical thinking assessments, 4.2.1. california critical thinking dispositions inventory (cctdi; insight assessment, inc. n.d. ), 4.2.2. california critical thinking skills test (cctst; insight assessment, inc. n.d. ), 4.2.3. cornell critical thinking test (cctt; the critical thinking company n.d. ), 4.2.4. california measure of mental motivation (cm3; insight assessment, inc. n.d. ), 4.2.5. ennis–weir critical thinking essay test ( ennis and weir 2005 ), 4.2.6. halpern critical thinking assessment (hcta; halpern 2012 ), 4.2.7. test of everyday reasoning (ter; insight assessment, inc. n.d. ), 4.2.8. watson–glaser tm ii critical thinking appraisal (w-gii; ncs pearson, inc. 2009 ).

“Virtual employees, or employees who work from home via a computer, are an increasing trend. In the US, the number of virtual employees has increased by 39% in the last two years and 74% in the last five years. Employing virtual workers reduces costs and makes it possible to use talented workers no matter where they are located globally. Yet, running a workplace with virtual employees might entail miscommunication and less camaraderie and can be more time-consuming than face-to-face interaction”.

5. Conclusions

Institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Ali, Marium, and AJLabs. 2023. How Many Years Does a Typical User Spend on Social Media? Doha: Al Jazeera. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/6/30/how-many-years-does-a-typical-user-spend-on-social-media (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Arendasy, Martin, Lutz Hornke, Markus Sommer, Michaela Wagner-Menghin, Georg Gittler, Joachim Häusler, Bettina Bognar, and M. Wenzl. 2012. Intelligenz-Struktur-Batterie (Intelligence Structure Battery; INSBAT) . Mödling: Schuhfried GmbH. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arum, Richard, and Josipa Roksa. 2010. Academically Adrift . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bakshy, Eytan, Solomon Messing, and Lada Adamic. 2015. Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science 348: 1130–32. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Bart, William. 2010. The Measurement and Teaching of Critical Thinking Skills . Tokyo: Invited colloquium given at the Center for Research on Education Testing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bruine de Bruin, Wandi, Andrew Parker, and Baruch Fischhoff. 2007. Individual differences in adult decision-making competence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92: 938–56. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Butler, Heather. 2012. Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment predicts real-world outcomes of critical thinking. Applied Cognitive Psychology 26: 721–29. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Butler, Heather, and Diane Halpern. 2020. Critical Thinking Impacts Our Everyday Lives. In Critical Thinking in Psychology , 2nd ed. Edited by Robert Sternberg and Diane Halpern. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Butler, Heather, Chris Dwyer, Michael Hogan, Amanda Franco, Silvia Rivas, Carlos Saiz, and Leandro Almeida. 2012. Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment and real-world outcomes: Cross-national applications. Thinking Skills and Creativity 7: 112–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Butler, Heather, Chris Pentoney, and Mabelle Bong. 2017. Critical thinking ability is a better predictor of life decisions than intelligence. Thinking Skills and Creativity 24: 38–46. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ennis, Robert. 2005. The Ennis-Weir Critical Thinking Essay Test . Urbana: The Illinois Critical Thinking Project. Available online: http://faculty.ed.uiuc.edu/rhennis/supplewmanual1105.htm (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Ennis, Robert, and Eric Weir. 2005. Ennis-Weir Critical Thinking Essay Test . Seaside: The Critical Thinking Company. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/1847582/The_Ennis_Weir_Critical_Thinking_Essay_Test_An_Instrument_for_Teaching_and_Testing (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Facione, Peter. 1990. California Critical Thinking Dispositions Inventory . Millbrae: The California Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Facione, Peter, Noreen Facione, and Kathryn Winterhalter. 2012. The Test of Everyday Reasoning—(TER): Test Manual . Millbrae: California Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Forsyth, Carol, Philip Pavlik, Arthur C. Graesser, Zhiqiang Cai, Mae-lynn Germany, Keith Millis, Robert P. Dolan, Heather Butler, and Diane Halpern. 2012. Learning gains for core concepts in a serious game on scientific reasoning. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Educational Data Mining . Edited by Kalina Yacef, Osmar Zaïane, Arnon Hershkovitz, Michael Yudelson and John Stamper. Chania: International Educational Data Mining Society, pp. 172–75. [ Google Scholar ]

- French, Brian, Brian Hand, William Therrien, and Juan Valdivia Vazquez. 2012. Detection of sex differential item functioning in the Cornell Critical Thinking Test. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 28: 201–7. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Frenkel, Sheera, and Mike Isaac. 2018. Facebook ‘Better Prepared’ to Fight Election Interference, Mark Zuckerberg Says . Manhattan: New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/13/technology/facebook-elections-mark-zuckerberg.html (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Gheorghia, Olimpiu. 2018. Romania’s Measles Outbreak Kills Dozens of Children: Some Doctors Complain They Don’t Have Sufficient Stock of Vaccines . New York: Associated Press. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/romania-s-measles-outbreak-kills-dozens-children-n882771 (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Giancarlo, Carol, Stephen Bloom, and Tim Urdan. 2004. Assessing secondary students’ disposition toward critical thinking: Development of the California Measure of Mental Motivation. Educational and Psychological Measurement 64: 347–64. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Halpern, Diane. 1998. Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains: Dispositions, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring. American Psychologist 53: 449–55. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Halpern, Diane. 2012. Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment . Mödling: Schuhfried (Vienna Test System). Available online: http://www.schuhfried.com/vienna-test-system-vts/all-tests-from-a-z/test/hcta-halpern-critical-thinking-assessment-1/ (accessed on 13 January 2013).

- Halpern, Diane. 2014. Thought and Knowledge: An Introduction to Critical Thinking , 5th ed. New York: Routledge Publishers. [ Google Scholar ]

- Halpern, Diane, Keith Millis, Arthur Graesser, Heather Butler, Carol Forsyth, and Zhiqiang Cai. 2012. Operation ARIES!: A computerized learning game that teaches critical thinking and scientific reasoning. Thinking Skills and Creativity 7: 93–100. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Huber, Christopher, and Nathan Kuncel. 2015. Does college teach critical thinking? A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research 86: 431–68. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Insight Assessment, Inc. n.d. Critical Thinking Attribute Tests: Manuals and Assessment Information . Hermosa Beach: Insight Assessment. Available online: http://www.insightassessment.com (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Jain, Anjali, Jaclyn Marshall, Ami Buikema, Tim Bancroft, Jonathan Kelly, and Craig Newschaffer. 2015. Autism occurrence by MMR vaccine status among US children with older siblings with and without autism. Journal of the American Medical Association 313: 1534–40. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Klee, Miles, and Nikki McCann Ramirez. 2023. AI Has Made the Israel-Hamas Misinformation Epidemic Much, Much Worse . New York: Rollingstone. Available online: https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-features/israel-hamas-misinformation-fueled-ai-images-1234863586/amp/?fbclid=PAAabKD4u1FRqCp-y9z3VRA4PZZdX52DTQEn8ruvHeGsBrNguD_F2EiMrs3A4_aem_AaxFU9ovwsrXAo39I00d-8NmcpRTVBCsUd_erAUwlAjw16x1shqeC6s22OCpSSx2H-w (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Klepper, David. 2022. Poll: Most in US Say Misinformation Spurs Extremism, Hate . New York: Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. Available online: https://apnorc.org/poll-most-in-us-say-misinformation-spurs-extremism-hate/ (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Landis, Richard, and William Michael. 1981. The factorial validity of three measures of critical thinking within the context of Guilford’s Structure-of-Intellect Model for a sample of ninth grade students. Educational and Psychological Measurement 41: 1147–66. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Liedke, Jacob, and Luxuan Wang. 2023. Social Media and News Fact Sheet . Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/ (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Lilienfeld, Scott, Rachel Ammirati, and Kristin Landfield. 2009. Giving debiasing away: Can psychological research on correcting cognitive errors promote human welfare? Perspective on Psychological Science 4: 390–98. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Michael, Joan, Roberta Devaney, and William Michael. 1980. The factorial validity of the Cornell Critical Thinking Test for a junior high school sample. Educational and Psychological Measurement 40: 437–50. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2015. Health, United States, 2015, with Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities ; Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- NCS Pearson, Inc. 2009. Watson-Glaser II Critical Thinking Appraisal: Technical Manual and User’s Guide . London: Pearson. Available online: http://www.talentlens.com/en/downloads/supportmaterials/WGII_Technical_Manual.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Stanovich, Keith, and Richard West. 2008. On the failure of cognitive ability to predict myside and one-sided thinking biases. Thinking & Reasoning 14: 129–67. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- The Critical Thinking Company. n.d. Critical Thinking Company. Available online: www.criticalthinking.com (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Tsipursky, Gleb. 2018. (Dis)trust in Science: Can We Cure the Scourge of Misinformation? New York: Scientific American. Available online: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/dis-trust-in-science/ (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Walsh, Catherina, Lisa Seldomridge, and Karen Badros. 2007. California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory: Further factor analytic examination. Perceptual and Motor Skills 104: 141–51. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- World Health Organization. 2018. Europe Observes a 4-Fold Increase in Measles Cases in 2017 Compared to Previous Year . Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/media-centre/sections/press-releases/2018/europe-observes-a-4-fold-increase-in-measles-cases-in-2017-compared-to-previous-year (accessed on 22 October 2023).

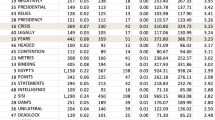

| CCTDI | CCTST | CCTT | CM3 | E-W | HCTA | TER | W-GII | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Disposition | Skills | Skills | Disposition | Skills | Skills | Skills | Skills |

| Respondent Age | 18+ | 18+ | 10+ | 5+ | 12+ | 18+ | Late childhood to adulthood | 18+ |

| Format(s) | Digital and paper | Digital | Paper | Digital and paper | paper | Digital | Digital and paper | Digital |

| Length | 75 items | 40 | 52–76 items | 25 items | 1 problem | 20–40 items | 35 items | 40 items |

| Administration Time | 30 min | 55 min | 50 min | 20 min | 40 min | 20–45 min | 45 min | 30 min |