Job satisfaction factors for housekeepers in the hotel industry: a global comparative analysis

International Hospitality Review

ISSN : 2516-8142

Article publication date: 18 December 2020

Issue publication date: 21 June 2021

This study offers a global comparative analysis of variables associated with job satisfaction, specifically work-life balance, intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, and work relations on job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers.

Design/methodology/approach

The study analyzes these variants across 29 countries using International Social Survey Program data.

Findings indicate significant differences in job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers across countries, lower job satisfaction for hospitality occupations compared to all other occupational categories, lower job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers than employees in other hospitality occupations, and a statistically significant positive impact of some elements of work-life balance, intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, and coworker relations on job satisfaction.

Originality/value

The hospitality industry is characterized by poor work-life balance, high turnover rates and limited rewards. Hotel housekeepers report lower levels of satisfaction than other hospitality workers in terms of work-life balance, pay, relationships with managers, useful work and interesting work. Housekeepers play an important role in hotel quality and guest satisfaction. As such, understanding and addressing factors contributing to job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers is critical for managers

- Job satisfaction

- Hospitality industry

Work-life balance

Andrade, M.S. , Miller, D. and Westover, J.H. (2021), "Job satisfaction factors for housekeepers in the hotel industry: a global comparative analysis", International Hospitality Review , Vol. 35 No. 1, pp. 90-108. https://doi.org/10.1108/IHR-06-2020-0018

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Maureen Snow Andrade, Doug Miller and Jonathan H. Westover

Published in International Hospitality Review . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Job satisfaction, or the “pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one's job or job experiences” ( Locke, 1976 , p. 1304) results in outcomes such as stronger job performance ( Harter et al. , 2002 ; Judge et al. , 2001 ; Ostroff, 1992 ; Ryan et al. , 1996 ), increased organizational citizenship behavior ( Hoffman et al. , 2007 ; Koys, 2001 ), improved customer satisfaction ( Schulte et al. , 2009 ; Vandenberghe et al. , 2009 ), moderately reduced absenteeism ( Scott and Taylor, 1985 ; Steel and Rentsch, 1995 ) and decreased turnover ( Hom and Griffeth, 1995 ; Griffeth et al. , 2000 ).

The hospitality industry is known for high employee turnover rates ( Davidson et al. , 2010 ), poor work-life balance ( Deery, 2008 ; Deery and Jago, 2009 , 2015 ; Davidson and Wang, 2011 ; Wolfe and Kim, 2013 ; Yang et al. , 2012 ; Zopiatis and Constanti, 2007 ), and limited extrinsic and intrinsic rewards due to low pay, extended working hours, lack of professional growth opportunities, inadequate personal time and exhaustion ( Deery and Jago, 2015 ; Groblena et al. , 2016 ). Job satisfaction is a critical issue for employers and managers in the hospitality industry in order to understand how to mitigate dissatisfiers and increase job satisfaction and motivation.

Globally, hotel housekeepers demonstrate significantly lower levels of satisfaction than other hospitality workers in terms of work-life balance, relationships with management, pay, perceptions of work being useful to society and interesting work ( Andrade and Westover, 2020 ). High housekeeper turnover puts guest satisfaction and a hotel's quality and competitiveness at risk ( Grobelna and Tokarz-Kocik, 2017 ). Studies on job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers primarily focus on working conditions in specific geographical locations ( Eriksson and Li, 2009 ; Hsieh et al. , 2016 ; Maumbe and Van Wyk, 2008 ; Powell and Watson, 2006 ). The current study examines country differences in job satisfaction among hotel housekeeping staff by examining work-life balance, intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, and work relations variables in 37 countries using International Social Survey Program data ( ISSP, 2015 ). The purpose of the study is to identify similarities and differences in the variables that impact job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers across countries with the goal of informing management practice. To our knowledge, this is the first global comparative study of job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers.

Literature review

Research on job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers indicates a range of conditions and experiences. Individual characteristics (e.g. education level, ethnicity, immigrant status), work-life balance (e.g. flexible scheduling, work interfering with families), work relations (e.g. relationships with coworkers, management, and guests), extrinsic rewards (e.g. pay, benefits, professional growth) and intrinsic rewards (e.g. task variety and significance) all play a role. We next examine these and other relevant themes identified in the research.

Demographic and contextual factors

Hotel housekeepers are primarily women with low levels of education ( Eriksson and Li, 2009 ; Hsieh et al. , 2016 ; Powell and Watson, 2006 ) and are often immigrants ( Krause et al. , 2010 ). In Denmark, housekeepers who are immigrants tend to have higher levels of education than their Danish counterparts but are underemployed due limited Danish language skills. In Wales, housekeepers may have some vocational training ( Powell and Watson, 2006 ). In Las Vegas, Latina hotel housekeepers typically lack educational credentials as well as English language skills ( Hsieh et al. , 2016 ). Unrecognized foreign credentials may also be an issue leading to under employment ( Hsieh et al. , 2016 ; Knox, 2011 ). In the hotel industry in South Africa, higher levels of education were correlated with job tenure for white employees and with shorter tenure for black employees who moved to other opportunities ( Maumbe and VanWyk, 2008 ). Length of service correlated with income increases for white but not for non-white employees.

The contexts in which housekeepers are employed varies greatly, including rural and urban hotel locations, the availability of government benefits and services which can offset other job disadvantages ( Eriksson and Li, 2009 ), and historical, economic and political factors that contribute to dissatisfaction such as racial inequities ( Maumbe and VanWyk, 2008 ). Urban hotel workers are more likely to be immigrants or ethnic minorities than those in rural locations ( Eriksson and Li, 2009 ; Knox, 2011 ; Watson and Power, 2006 ).

Job characteristics

Common safety and health risks associated with hotel housekeeping, which potentially affect job satisfaction, include exposure to hazardous chemicals, physical demands such as heavy lifting and repeated bending ( Eriksson and Li, 2009 ; Knox, 2011 ; Hsieh et al. , 2016 ; Krause et al. , 2002 ; Lee and Krause, 2002 ; Powell and Watson, 2006 ); work-related physical pain that goes largely unreported ( Lee and Krause, 2002 ); time pressure, job stress, and low job control ( Lee and Krause, 2002 ; Krause et al. , 2002 ; Powell and Watson, 2006 ); lack of social status, invisibility due to work being perceived as unskilled, and limited promotion opportunities ( Powell and Watson, 2006 ; OnsØyen et al. , 2009 ). Hotel housekeepers in Cardiff, Wales described their work as tiring, low paid, hard, dirty, repetitive, and uninteresting ( Powell and Watson, 2006 ). In some situations, housekeepers supply their own cleaning resources rather than waiting for management to provide needed items ( Knox, 2011 ).

Extrinsic rewards

Extrinsic factors cause both job satisfaction and dissatisfaction for hotel housekeepers. Job satisfaction for housekeepers in Denmark is high due to comparatively good pay, scheduling flexibility, a congenial working climate, guaranteed work hours and task variety ( Eriksson and Li, 2009 ). In Australia, room attendants are often paid by the number of rooms they clean and are not paid for a full workday if they do not complete their assigned number of rooms ( Knox, 2011 ). If they complete rooms before they work time is up, they are required clean elsewhere in the hotel. In South Africa, job satisfaction among hotel employees as a whole is considered high although low pay, pay inequities, and long working hours contribute to dissatisfaction ( Maumbe and Van Wyk, 2008 ). These studies illustrate that pay in one context can be a satisfier and in another, a dissatisfier.

Latina hotel housekeepers in Las Vegas reported positive aspects of work as coworker relations, flexible scheduling and hours, and simply having a job while dissatisfiers included lack of benefits, low pay, weekend work, unfair assignments, coworker discrimination, inadequate equipment, and heavy physical and repetitive work ( Hsieh et al. , 2016 ). Economic rewards are highly valued ( Powell and Watson, 2006 ). Low pay for housekeepers in Australia presents economic challenges and satisfaction with pay varies from feelings that it is inadequate to accepting that it is sufficient ( Knox, 2011 ). Some extrinsic factors identified in these studies were satisfiers (e.g. scheduling, having a job), but most were dissatisfiers (e.g. lack of benefits, low pay, long hours, the nature of job tasks).

Intrinsic rewards

Housekeeping staff work independently and autonomously, factors associated with intrinsic motivation ( Deci et al. , 1999 ; Deci and Ryan, 2002 ; Pink, 2009 ). Housekeeper autonomy is also associated with organizational commitment, which leads to increased productivity and decreased turnover ( Groblena and Tokarz-Kocik, 2017 ). Cardiff hotel housekeepers reported having their work monitored by a supervisor but also having “scope to determine the sequence and pace of tasks” ( Powell and Watson, 2006 , p. 301). Empowerment strategies involving room self-checks and decreased supervision, higher hourly compensation, and recognition points for positive guest reviews increased pressure but also pride in work, valuing guest interactions, visibility of work and guest tipping ( Powell and Watson, 2006 ), reflecting both intrinsic and extrinsic rewards.

Some Australian hotel housekeepers, particularly older workers, view independence and the physical nature of the work as advantages leading to satisfaction and pride ( Knox, 2011 ). Housekeepers also report that they enjoy serving others, take pride in their roles, and establish personal goals to improve their work ( Robinson et al. , 2015 ). They see visible results of their work and value their part in creating a positive image for the hotel. In the Cardiff study, 94% of housekeepers saw their work as useful and 62% were proud of their jobs ( Powell and Watson, 2006 ). Initiatives such as room self-checking increase autonomy and trust ( Kensbock et al. , 2013 ).

Increased visibility of work and recognition of its impact on guests is reflected in Hackman and Oldham's (1967 , 1980) job characteristics model. Core job characteristics such as task significance lead to an increased sense of meaningfulness in one's work and intrinsic motivation. Task variety contributes to job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers in Denmark ( Eriksson and Li, 2009 ), but in other contexts, work repetitiveness is a problem ( Knox, 2011 ; Hsieh et al. , 2016 ; Watson and Powell, 2016 ).

Autocratic management and control as opposed to encouraging initiative and reduced autonomy are issues for housekeepers in parts of Australia ( Kensbrock et al. , 2013 ). A Polish study showed that as workload increases, organizational commitment decreases ( Groblena and Tokarz-Kocik, 2017 ). The same was true of role conflict resulting in unclear expectations. A New Zealand study found that in the hotel industry generally, respect, autonomy, task variety and task meaningfulness lead to career longevity ( Mooney et al. , 2015 ).

Some aspects of work-life balance for hotel housekeepers are problematic such as working weekends ( Hsieh et al. , 2016 ) or long hours for hospitality employees generally ( Maumbe and VanWyk, 2008 ); however, scheduling flexibility is a satisfier as it allows housekeepers, who are primarily female, to work around their children's school schedules ( Eriksson and Li, 2009 ; Hsieh et al. , 2016 ; Hunter-Powell and Watson, 2006 ). A comparison of housekeepers, front office, and food and beverage staff found that managers are considered central to work-life balance through their scheduling, teamwork, and cross-training functions ( Robinson et al. , 2015 ). Australian room attendants perceived a positive work-life balance with a sufficient number of days off and convenient working schedules, allowing time for family and personal interest ( Robinson et al. , 2015 ).

Worker relations

Worker relations for hotel housekeepers contributes to job satisfaction when positive coworker connections are present ( Eriksson and Li, 2009 ). Relatedness is a component of self-determination theory, which argues that feelings of connection and belonging strengthen motivation ( Deci et al. , 1999 ; Deci and Ryan, 2002 ). In the Cardiff study, half of the participants indicated that if they lost their jobs, they would miss their friendships the most ( Powell and Watson, 2006 ). The majority indicated being respected by supervisors and guests, but a third did not feel respected by other workers. This feeling was also evident in an Australian study in which housekeepers felt looked down on by other hotel workers due to the nature of their work ( Robinson et al. , 2015 ) and in a study of Las Vegas hotel housekeepers ( Hsieh et al. , 2016 ).

In other cases, workers feel discriminated against by management ( Hsieh et al. , 2016 ; Maumbe and Van Wyk, 2008 ). Housekeepers also feel they are undervalued, not listened to, not involved in decision making, and that managers are unavailable ( Kensbock et al. , 2013 ; OnsØyen et al. , 2009 ). Social interactions with customers may also prove problematic due to unwanted attention and harassment ( Powell and Watson, 2006 ; Kensbock et al. , 2016 ).

Satisfaction with management and satisfaction and coworkers has been correlated with positive organizational behavior for hotel housekeepers in Croatia, potentially resulting in greater guest satisfaction ( Ažić, 2017 ). A New Zealand study found that strong social connections among managers, coworkers, and guests led to the establishment of a positive professional identity and increased job tenure ( Mooney et al. , 2015 ). Similarly, an Australian study identified that working relationships and being in a team environment were linked to satisfaction ( Robinson et al. , 2015 ).

As is evident in this review, previous research has focused primarily on demographic profiles, the nature of housekeeping work, and location-specific studies. Housekeepers typically have low levels of education and may be immigrants or from ethnic minority groups. Work-life balance, specifically work interfering with families, is generally not a dissatisfier. In fact, most of the studies reviewed indicated that housekeepers had sufficient flexibility in scheduling to accommodate their children's school schedules as well as time to spend with family. However, in other cases, long hours and working weekends were problematic, both of which could interfere with families.

Findings on work relations with coworkers were mixed. Friendships and positive working environments contributed to job satisfaction but workers also experienced discrimination and harassment from coworkers and guests, and relationships with management were sometimes characterized by perceived and actual inequities and reluctance to request benefits such as sick days or report physical injuries, demonstrating a lack of trust. Extrinsic rewards in the form of pay is a dissatisfier in most contexts while intrinsic rewards in the form of task significance contribute to job satisfaction.

What researchers term as high or low levels of job satisfaction vary. Hsieh et al. (2016) considered that 54% of housekeepers being satisfaction with their jobs and 23% being dissatisfied to be low relative to findings of other studies. For example, 74% of hotel housekeepers in the Cardiff study reported high job satisfaction ( Powell and Watson, 2006 ) and 79% of housekeepers in a San Francisco study similarly reported high levels of satisfaction ( Lee and Krause, 2002 ). The Danish study identified high levels of job satisfaction overall ( Eriksson and Li, 2009 ). In another study, 63.1% of South African hotel housekeepers reported being very satisfied or satisfied, which the researchers considered to be a high outcome ( Hsieh et al. , 2016 ).

It should be noted that the studies cited in this review are based on both qualitative and quantitative data to provide in depth understanding of job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers. For example, in the Krause et al. (2002) study of Las Vegas hotel housekeepers, participants were involved in formulating the research questions and developing the survey instrument as well as interpreting the results, thus the study was informed by the first-hand experiences of the participants. Hsieh et al. 's (2016) study of Latina hotel housekeepers in Las Vegas was based on interviews. The study of housekeepers in Wales consisted of a survey followed by interviews and observations ( Powell and Watson, 2006 ). The Denmark study was comprised of case studies, including interviews with general managers and room attendants ( Eriksson and Li, 2009 ). Methods for the Norwegian study were interviews and focus groups in order to obtain rich data about the participants' experiences ( OnsØyen et al. , 2009 ). Knox's (2011) study of four- and five-star hotels in Sydney, Australia was based on case studies with data collected through interviews and combined with quantitative data on hotel performance and employment records. In-depth interviews were the primary source of data for the study of Gold Coast hotels in Australia conducted by Kensbock et al. (2013) , and memory work and semi-structured interviews in Kensbock et al.' s (2016) study. The New Zealand study by Mooney et al. (2015) consisted of interviews while the Robinson et al. (2015) study of housekeepers in Eastern Australian hotels was based on data from semi-structured interviews.

Thus, the findings discussed in this literature review tell the stories of the lived experiences and daily realities of housekeepers representing a variety of demographics and job profiles and working in a range of hotel types. While these studies provide insights into job satisfaction factors for hotel housekeepers in specific cities or countries (e.g. Krause et al. , 2002 ; Lee and Krause, 2002 ; Powell and Watson, 2006 ), however, this review has established that global comparative studies have not been conducted.

Theoretical framework and model

Over the previous half century, thousands of research studies have examined job satisfaction as an outcome variable, as well as its determinants. As seen in Figure 1 below, we utilize a job satisfaction theoretical and empirical model developed by Andrade and Westover's (2018a , b) ; e.g. see also Andrade et al. (2019a , b) , which synthesizes much of the literature to date on job satisfaction and its determinants. As has been done in many previous research studies, we include work-life balance, work relations, and other important intrinsic and extrinsic rewards variables, as well as organizational and job characteristics control variables. Additionally, we have included an occupation variable to explore differences in the model based on the type of hospitality management job the respondent currently holds.

Research design and methodology

There will be statistically significant differences in the levels of job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers across countries.

Job satisfaction for employees in hospitality occupational categories will be lower than for employees in all other occupational categories, controlling for other work characteristic and individual factors.

Job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers will be lower than for employees in other hospitality occupational categories, controlling for other work characteristic and individual factors.

There will be statistically significant cross-national differences in the mean scores of the determinants of job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers.

Work-life balance factors will have a statistically significant positive impact on the job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers across nations.

Extrinsic rewards will have a statistically significant positive impact on the job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers across nations.

Intrinsic rewards will have a statistically significant positive impact on the job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers across nations.

Coworker relations factors will have a statistically significant positive impact on the job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers across nations.

Description of the data

Following the approach of Andrade and Westover's (2018a , b) ; e.g. see also Andrade et al. (2019a , b) , this research utilizes cross national comparative data from the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) 2015 Work Orientations Module IV [1] , which uses multistage stratified probability samples in 37 individual countries around the globe [2] and asks questions about employees' work experiences, conditions, and perceptions. In this analysis, we focus on hotel housekeepers, with N = 408, all hospitality workers, with an N = 982, and all workers, with an N = 18,716 . As Westover noted, “The International Social Survey Program Work Orientations modules utilized a multistage stratified probability sample to collect the data for each of the various countries with a variety of eligible participants in each country's target population” ( 2012a , p. 3). All ISSP Work Orientation variables are single-item indicators and the unit of analysis is individuals across each participating country. The sample of hotel housekeepers, by the 29 countries, is as follows in Table 1 .

Operationalization of variables

We use Andrade and Westover's (2018a , b) ; e.g. see also Andrade et al. (2019a , b) job satisfaction model (building on Handel's (2005) and Kalleberg's (1977) job satisfaction model, for comparing global differences in job satisfaction and its determinants across job types (e.g. see also Spector, 1997 ; Souza-Poza and Souza-Poza, 2000 ). Following the approach of Andrade and Westover's (2018a ; b ; see also Andrade et al. , 2019a , b ), we focused on a range of intrinsic, extrinsic, workplace relationships and work-life balance variables (in addition to a range of organization and individual control variables; Table 2 below [3] ).

Control variables

As indicated by Westover (2012b , p. 17) “the literature has identified many important individual control variables, due to limitations in data availability, control variables used for the quantitative piece of this study will be limited to the following individual characteristics: (1) Sex, (2) Age, (3) Years of Education, (4) Marital Status, and (5) Size of Family…” ( 2012b , p. 17). Additionally, control variables used in this analysis include: (1) Work Hours, (2) Supervisory Status, (3) Employment Relationship, and (4) Public/Private Organization (see Hamermesh, 2001 ; Souza-Poza and Souza-Poza, 2000 ).

Statistical methodology

We analyzed ISSP Work Orientations data from individual respondents across 37 counties, first running appropriate bivariate and multivariate analyses [4] on all key study variables in order to make comparisons. Next, we ran an Ordinary Least Squares Regression (OLS) model for all main study variables and respondents in all countries, followed by an OLS regression model specific for all hospitality jobs lumped together. Finally, we ran OLS regression models for all hotel housekeepers in all countries.

Descriptive results

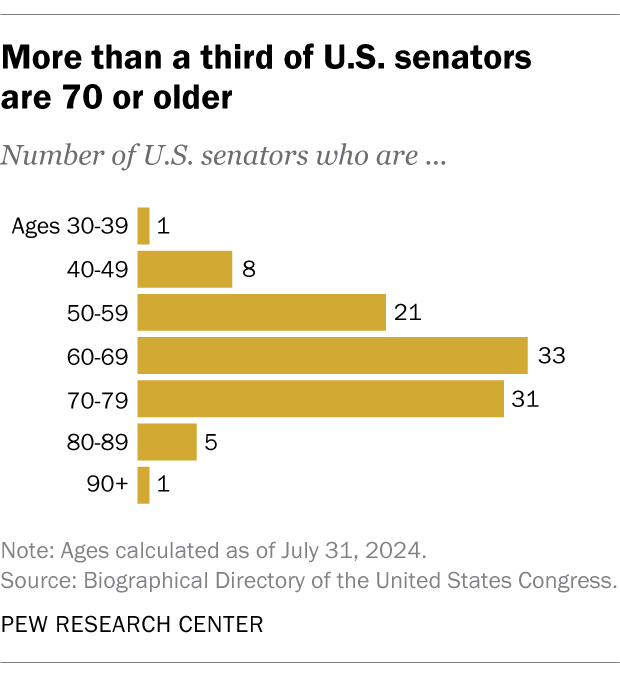

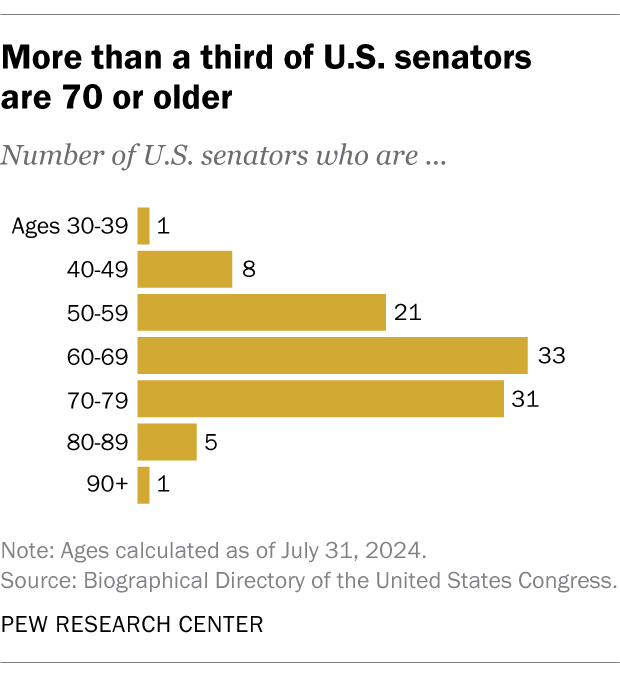

Figure 2 shows mean job satisfaction scores for housekeepers, by country. The highest job satisfaction levels for housekeeping jobs is in the Philippines (6.50), Chile (5.96), with the lowest job satisfaction scores in Israel (4.00), China (4.33), and Sweden (4.43). Housekeepers in most nations have a mean job satisfaction scores in the 4.7 to 5.3 range (overall world-wide mean for all occupations is 5.32).

Tables 2 and 3 below shows the means of job satisfaction and other main study variables, broken down for housekeepers, all other hospitality occupations (11 total), and all jobs, regardless of occupation type for respondents in all 37 countries included in the 2015 wave of ISSP Work Orientations data. We also ran descriptive statistics for hotel housekeepers by country to be able to compare mean scores of main study variables (those results are available upon request). Of note is the general variation across countries for the different study variables and the difference between housekeepers with other hospitality jobs and when compared with all occupations. Housekeepers have lower overall job satisfaction than other hospitality workers, and much lower than workers across all occupations. Additionally, housekeepers have lower mean scores than other hospitality workers in 12 of the 19 work characteristics examined, with the biggest gap landing on “interesting work.”

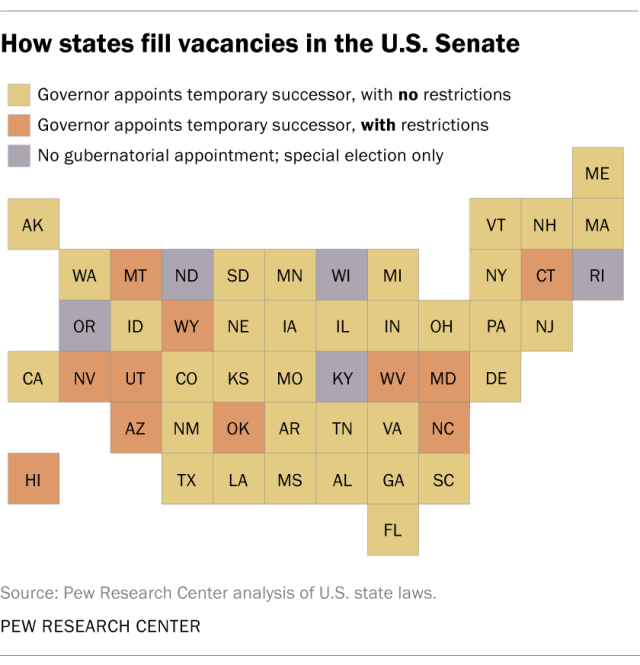

As we examined the study variables with the greatest variations in means scores between housekeepers and other hospitality occupations, as well as across countries, our attention was drawn toward the following variables, as depicted in Figures 3–5 below: Interesting Work, Useful Job, Pay, Relations with Management, and Work Interferes with Family. In each case, we see a clear linear relationship between the work characteristic of housekeepers and the corresponding job satisfaction. As interesting work, useful work, pay and relations with management improved, job satisfaction improves. Additionally, the more work interferes with family, job satisfaction declines.

Regression results

Model 1 – All control variables

Model 2 – All intrinsic rewards variables

Model 3 – All extrinsic rewards variables

Model 4 – All work relations variables

Model 5 – All work-life balance variables

Model 6 – Combined model of all key independent variables (intrinsic, extrinsic, work relations, and work-life balance) and the control variables on job satisfaction.

Nearly all variables were statistically significant ( p < 0.001) when the individual control model and models 2–5 were run, with the exception of size of family and working weekends. However, in the combined model, working weekends was significant, while physical effort, contact with others, working from home, and several individual control variables were not significant. Additionally, there were variations in adjusted r-squared values for the individual controls model and models 2–5 (with the separate intrinsic and extrinsic rewards models holding the strongest predictability), with the combined model (including all intrinsic, extrinsic, work relations, work-life balance, and control variables) accounting for nearly 43% of the variation in job satisfaction (adjusted r -squared = 0.428).

The above specified combined model was then run for workers across all job types, for all hospitality workers combined, and then for hotel housekeepers specifically. As can be seen in Table 3 , there is a great deal of variation between occupational categories in standardized beta coefficient statistical significance for each of the intrinsic, extrinsic, work relations, and work-life balance job characteristics and control variables in predicting job satisfaction. Of particular note is that many of the statistically significant independent variables in the model for all workers were not significant in the model for all hospitality jobs and the model for housekeepers. Part of this is likely due to the relatively small N for the hospitality occupations generally, but housekeepers, specifically (where achieving statistical significance of a variable is more difficult). We also see some clear patterns of difference in the driving indicators of job satisfaction in housekeeping jobs and hospitality jobs when compared with those of all jobs in general.

For housekeepers specifically, only two intrinsic variables (interesting work and job useful to society), one extrinsic variable (pay), one work relations variable (relations with management) and one work-life-balance variable (work interferes with family) was statistically significant, as compared to the model for all occupations, in which intrinsic and extrinsic variables are the most significant and have the strongest standardized beta coefficients (the most impact on predictability of job satisfaction).

Revisiting hypotheses

This study looked at the housekeeping function across the globe for clues on differences in job satisfaction. We anticipated that universally accepted factors determining job satisfaction would exhibit low results for hotel housekeepers across the studied countries. This is largely borne out in the study results (see Table 5 ). Difference of means analysis demonstrates a statistically significant difference in mean scores across the 29 countries in the study ( H1 ; see Figure 2 ). Additionally, results show that generally all countries face the same challenges. Outside of a few outliers among the 29 countries studied, all countries gave housekeeper job satisfaction scores lower than all other hospitality job categories and again lower still from all non-hospitality occupations ( H2 and H3 ; see Tables 2 and 3 ).

Furthermore, results affirm statistically significant differences in the mean scores of the determinants of hotel housekeeper job satisfaction across countries ( H4 ; see Tables 2 and 3 ). In terms of the statistical significance of job satisfaction determinants within the OLS regression analysis, all categories of independent variables employed in this study provided mixed results in relation to study hypotheses ( H5 , H6 , H7 and H8 ; see Table 4 ). Overall, there are demonstrated cross-national differences in statistical significance and variable beta coefficient strength across each of the work-life balance ( H5 ), extrinsic rewards ( H6 ), intrinsic rewards ( H7 ), work relations ( H8 ) variables for hotel housekeepers, versus all hospitality workers and all workers. Within each variable category, some variables are statistically significant, while others are not. With the exceptions of education level (a control variable), all statistically significant variables across variable categories have a positive relationship with job satisfaction. Education has a negative relationship, meaning that as the education level of hotel housekeepers increase, job satisfaction decreases. Additionally, statistically significant cross-national differences in mean scores of main study variables further supports these hypotheses.

Housekeeping is the most critical function of a lodging operation. A clean room is often taken for granted by guests, but hospitality managers know that a room not cleaned properly will cause the greatest level of guest dissatisfaction. Housekeeping in a hotel is also the largest department in a hotel, and often the lowest paid department. This combination – most critical to operation and guest satisfaction while also the hardest to staff – is why it is considered the most difficult department to manage in a hotel.

Comparative OLS model comparisons and comparisons of mean score differences reveal lower satisfaction levels and work quality characteristics when compared to both “other hospitality occupations” and “all occupations” groups were. While this may be discouraging to lodging managers, considering the importance of the housekeeping function and the difficulty hiring and maintaining a strong housekeeping crew, it can be considered an opportunity for improvement. Incremental positive movement in any or all of these characteristics will improve job satisfaction and close the gap between housekeepers and other occupations.

For example, intrinsic rewards internalized by housekeepers (particularly helping other people and job useful to society) can be improved by the culture of the hotel and the narrative communicated to the staff. Extensive previous research has indicated the importance of intrinsic factors such as autonomy, empowerment ( Groblena and Tokarz-Kocik, 2017 ; Kensbock et al , 2013 ; Mooney et al. , 2015 ), work pride ( Powell and Watson, 2006 ; Robinson et al. , 2015 ), and task variety ( Eriksson and Li, 2009 ) as contributing to job satisfaction. There is a disconnect between the reality of the housekeepers self-reported scores on intrinsic factors and the fact that these positions are tremendously valuable to society. With little or no costs, management can create opportunities and initiatives for housekeeping staff to learn and internalize this value. Creating more opportunities for housekeepers to engage with guests (work relations/contact with others) can also be designed and managed to increase their interest in their work and understand the importance of their role.

Another area where improvement appears to be needed and obtainable is relations with coworkers and with management. Previous research indicates that good relations with coworkers positively impacts job satisfaction ( Ericksson and Li, 2009 ; Powell and Watson, 2006 ; Robinson et al. , 2015 ) and is negatively impacted when housekeepers are not involved in decision-making, feel undervalued, or are not listened to by management ( Kensbock et al. , 2013 ; OnsØyen et al. , 2009 ). While the overall scores in these factors were not necessarily terribly low (relations with management was significantly lower than others), they present potential places for improvement where financial resources are not required. Instead good and creative management practices alone can create improvement.

Finally, one area often cited as an obvious target to increase job satisfaction is to increase wages. Previous studies have identified the importance of economic rewards to job satisfaction ( Powell and Watson, 2006 ) and low pay as a dissatisfier ( Hsieh et al. , 2016 ; Knox, 2011 ; Maumbe and Van Wyk, 2008 ) with some exceptions ( Eriksson and Li, 2009 ). However, hoteliers are constrained by economic factors often outside their control when it comes to pay. Housekeepers are a fairly ubiquitous employee group where pay rates do not vary much among hotels in geographic areas. While housekeepers identify pay as a significant satisfaction factor in this study, this decision is outside the discretion of the hotels' management. This research identifies 19 factors that affect morale and job satisfaction. Therefore, managers can pursue factors other than pay to improve the job satisfaction of the critical housekeeping team.

Limitations and future research

In this study, we did not have enough participants in each individual countries to run the OLS regression model by country and test the statistical significance of the determinants of job satisfaction across countries. Future research can seek for larger in-country samples of hotel housekeepers. Additionally, there is potential for an interesting study further examining the differing mean scores by country. In terms of country comparisons, a question worth pursuing is whether hotel housekeepers in developed counties have higher or lower job satisfaction in than those in developing countries. As well, future research could examine the role of cultural differences in understanding country differences and looking for ways to improve job satisfaction.

Additionally, as mentioned above, housekeeper pay is a challenging problem for hotel managers and owners. Due to the size of the housekeeping department, raising the wages of housekeepers is difficult to budget. And, raising the wages of this department then puts pressure on managers to raise wages for all the other line-level employees (e.g. front desk staff). Future research should address in more detail the impact pay has on job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers across countries. This research may also look at whether those paid more are also more productive in their overall job performance.

Factors influencing work characteristics and job satisfaction

Mean job satisfaction of housekeepers, by country

Mean job satisfaction by response to interesting work, useful job and pay

Mean job satisfaction score by response to relations with management

Mean job satisfaction score by response to work interferes with family

Hotel housekeeper sample, by country

| Country | Sample size | Country | Sample size |

|---|

| Austria | 7 | Latvia | 17 |

| Belgium | 24 | Lithuania | 10 |

| Chile | 23 | Mexico | 9 |

| China | 12 | Philippines | 4 |

| Taiwan | 19 | Poland | 23 |

| Czech Republic | 21 | Russia | 12 |

| Estonia | 24 | Slovak Republic | 17 |

| Finland | 14 | Slovenia | 7 |

| France | 3 | South Africa | 29 |

| Georgia | 11 | Spain | 34 |

| Hungary | 12 | Suriname | 16 |

| Iceland | 4 | Sweden | 7 |

| India | 6 | United States | 14 |

| Israel | 7 | Venezuela | 7 |

| Japan | 15 | | |

Key work characteristics related to job satisfaction

| |

| Job satisfaction | “How satisfied are you in your main job?” |

| |

| Interesting job | “My job is interesting.” |

| Job autonomy | “I can work independently.” |

| Help others | “In my job I can help other people.” |

| Job useful to society | “My job is useful to society.” |

| |

| Pay | “My income is high.” |

| Job security | “My job is secure.” |

| Promotional opportunities | “My opportunities for advancement are high.” |

| Physical effort | “How often do you have to do hard physical work?” |

| Work stress | “How often do you find your work stressful?” |

| |

| Management–employee relations | “In general, how would you describe relations at your workplace between management and employees?” |

| Coworker relations | “In general, how would you describe relations at your workplace between workmates/colleagues?” |

| Contact with others | “In my job, I have personal contact with others.” |

| Discriminated against at work | “Over the past 5 years, have you been discriminated against with regard to work, for instance, when applying for a job, or when being considered for a pay increase or promotion?” |

| Harassed at work | “Over the past 5 years, have you been harassed by your supervisors or coworkers at your job, for example, have you experienced any bullying, physical, or psychological abuse?” |

| |

| Work from home | “How often do you work at home during your normal work hours?” |

| Work Weekends | “How often does your job involve working weekends?” |

| Schedule flexibility | “Which of the following best describes how your working hours are decided (times you start and finish your work)?” |

| Flexibility to deal with family matters | “How difficult would it be for you to take an hour or two off during work hours, to take care of personal or family matters?” |

| Work interferes with family | “How often do you feel that the demands of your job interfere with your family?” |

: Response categories for this variable include: (1) Completely Dissatisfied, (2) Very Dissatisfied, (3) Fairly Dissatisfied, (4) Neither Satisfied nor Dissatisfied, (5) Fairly Satisfied, (6) Very Satisfied, (7) Completely Satisfied Response categories for these variables include: (1) Strongly Disagree, (2) Disagree, (3) Neither Agree nor Disagree, (4) Agree, and (5) Strongly Agree

Response categories for this variable include: (1) Always, (2) Often, (3) Sometimes, (4) Hardly Ever, (5) Never

Response categories for this variable include: (1) Always, (2) Often, (3) Sometimes, (4) Hardly Ever, (5) Never

| Variable | Hotel housekeepers | All hospitality occupations | All occupations |

|---|

| Job satisfaction | 4.99 | 5.12 | 5.32 |

| Interesting work | 3.00 | 3.39 | 3.83 |

| Job autonomy | 3.64 | 3.55 | 3.82 |

| Help others | 3.62 | 3.69 | 3.88 |

| Job useful to society | 3.88 | 3.76 | 3.94 |

| Job security | 3.56 | 3.66 | 3.77 |

| Pay | 2.20 | 2.43 | 2.82 |

| Promotional opportunities | 2.21 | 2.47 | 2.78 |

| Physical Effort | 3.44 | 3.30 | 2.71 |

| Work stress | 2.80 | 3.08 | 3.17 |

| Relations with coworkers | 4.05 | 4.14 | 4.19 |

| Relations with management | 3.88 | 3.95 | 3.91 |

| Contact with Others | 3.97 | 4.20 | 4.23 |

| Discriminated against at work | 1.80 | 1.79 | 1.82 |

| Harassed at Work | 1.85 | 1.84 | 1.86 |

| Work from home | 4.49 | 4.38 | 4.00 |

| Work weekends | 3.44 | 2.69 | 3.14 |

| Schedule Flexibility | 1.37 | 1.45 | 1.63 |

| Flexibility to deal with family matters | 2.30 | 2.47 | 2.25 |

| Work interferes with family | 3.99 | 3.78 | 3.66 |

| Age | 48.11 | 42.38 | 43.37 |

| Education | 11.11 | 11.90 | 13.34 |

| Size of family | 3.27 | 3.18 | 3.23 |

| Sample size | 408 | 982 | 18,716 |

OLS regression results of job satisfaction and main study variables, 2015

| Variable | Hotel housekeepers | All hospitality occupations | All occupations |

|---|

| Interesting work | 0.238*** | 0.255*** | 0.287*** |

| Job autonomy | −0.008 | 0.041 | 0.019** |

| Help others | −0.030 | 0.010 | 0.022** |

| Job useful to society | 0.171** | 0.121*** | 0.037*** |

| Job security | 0.078 | 0.103*** | 0.063*** |

| Pay | 0.144** | 0.123*** | 0.098*** |

| Promotional opportunities | −0.016 | −0.029 | 0.057*** |

| Physical effort | −0.057 | −0.015 | 0.005 |

| Work stress | −0.069 | −0.049 | −0.086*** |

| Relations with Coworkers | −0.007 | 0.08** | 0.085*** |

| Relations with management | 0.262*** | 0.238*** | 0.225*** |

| Contact with others | 0.012 | −0.014 | 0.010 |

| Discriminated against at work | 0.062 | 0.049* | 0.037*** |

| Harassed at Work | −0.030 | −0.053* | 0.019*** |

| Work from home | 0.043 | −0.019 | 0.005 |

| Work weekends | −0.072 | −0.081** | −0.023*** |

| Schedule flexibility | −0.025 | −0.015 | 0.014* |

| Flexibility to deal with family matters | −0.011 | 0.002 | −0.036*** |

| Work interferes with family | 0.158** | 0.186*** | 0.097*** |

| Gender | −0.044 | 0.012 | 0.005 |

| Age | 0.000 | 0.037 | 0.033*** |

| Education | −0.121** | −0.063** | −0.045*** |

| Marital status | −0.061 | −0.064* | −0.028*** |

| Size of family | −0.036 | −0.037 | −0.007 |

| Work hours | −0.032 | −0.006 | 0.006 |

| Supervisory status | −0.014 | −0.012 | −0.004 |

| Employment relationship | 0.059 | −0.059* | 0.008 |

| Public/Private organization | 0.068 | −0.064* | −0.028*** |

| | 408 | 982 | 18,716 |

| Adj. -squared | | | |

| | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 483.58*** |

: Beta Values; Level of significance: * = < 0.05; ** = < 0.01; *** = < 0.001 | Hypotheses | Variables | Support |

|---|

| : There will be statistically significant differences in the levels of job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers across countries | | Supported. ≤ 0.001 |

| : Job satisfaction for employees in hospitality occupational categories will be lower than for employees in all other occupational categories, controlling for other work characteristic and individual factors | | Supported ≤ 0.001 |

| : Job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers will be lower than for employees in other hospitality occupational categories, controlling for other work characteristic and individual factors | | Supported ≤ 0.001 |

| : There will be statistically significant cross-national differences in the mean scores of the determinants of job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers | | Supported ≤ 0.001 |

| : Work-life balance factors will have a statistically significant positive impact on the job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers across nations | Work from home | Supported ≤ 0.001 (“mixed” among variables – namely work interferes with family) |

| Work weekends |

| Schedule Flexibility |

| Flexibility with family matters |

| Work interferes with family |

| : Extrinsic rewards will have a statistically significant positive impact on the job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers across nations | Pay | Supported ≤ 0.001 (“mixed” among variables – namely pay) |

| Job security |

| Promotional opportunities |

| Physical effort |

| Work stress |

| : Intrinsic rewards will have a statistically significant positive impact on the job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers across nations | Interesting job | Supported ≤ 0.001 (“mixed” among variables – namely interesting work and useful to society) |

| Job autonomy |

| Help others |

| Job useful to society |

| : Coworker relations factors will have a statistically significant positive impact on the job satisfaction for hotel housekeepers across nations | Management-employee relations | Supported ≤ 0.001 (“mixed” among variables – namely relations with management) |

| Coworker relations |

| Contact with others |

| Discriminated against at work |

| Harassed at work |

ISSP Researchers collected the data using multistage stratified random sampling, using self-administered questionnaires, personal interviews, and mail-back questionnaires, depending on the country. For a full overview of the questions in the Work Orientations IV module and for a full summary and description of this research, see https://www.gesis.org/issp/modules/issp-modules-by-topic/work-orientations/2015/ .

Countries include, in alphabetical order: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Chile, China, Taiwan, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, India, Israel, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Philippines, Poland, Russia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Suriname, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States, Venezuela.

Each variable is a single-item indicator.

All correlations, cross-tabulations, ANOVA, ANCOVA, post-hoc tests, and full descriptive statistics have not been included here due to space limitations, but are available upon request. Additionally, appropriate tests for multicollinearity were conducted. There are no issues with multicollinearity of variables in the OLS model. Additionally, all outliers were Winsorized in the initial data cleaning stages, prior to final models and analysis.

Andrade , M.S. and Westover , J.H. ( 2018a ), “ Generational differences in work quality characteristics and job satisfaction ”, Evidence-based HRM , Vol. 6 No. 3 , pp. 287 - 304 .

Andrade , M.S. and Westover , J.H. ( 2018b ), “ Revisiting the impact of age on job satisfaction: a global comparative examination ”, The Global Studies Journal , Vol. 1 No. 4 , pp. 1 - 24 .

Andrade , M.S. , Westover , J.H. and Kupka , B.A. ( 2019a ), “ The role of work-life balance and worker scheduling flexibility in predicting global comparative job satisfaction ”, International Journal of Human Resource Studies , Vol. 9 No. 2 , pp. 80 - 115 .

Andrade , M.S. , Westover , J.H. and Peterson , J. ( 2019b ), “ Job satisfaction and gender ”, Journal of Business Diversity , Vol. 19 No. 3 , pp. 22 - 40 .

Andrade , M.S. and Westover , J.H. ( 2020 ), “ Comparative job satisfaction and its determinants in for-profit and nonprofit employees across the globe ”, American Journal of Management , Vol. 20 No. 1 .

Ažić , M.L. ( 2017 ), “ The impact of hotel employee satisfaction on hospitality performance ”, Tourism and Hospitality Management , Vol. 23 No. 1 , pp. 105 - 117 .

Davidson , M. and Wang , Y. ( 2011 ), “ Sustainable labor practices? Hotel human resource managers views on turnover and skill shortages ”, Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism , Vol. 10 No. 3 , pp. 235 - 253 .

Davidson , M.C. , Timo , N. and Wang , Y. ( 2010 ), “ How much does labour turnover cost? A case study of Australian four-and five-star hotels ”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 22 No. 4 , pp. 451 - 466 .

Deci , E. and Ryan , R. (Eds) ( 2002 ), Handbook of Self-Determination Research , University of Rochester Press , Rochester, NY .

Deci , E.L. , Koestner , R. and Ryan , R.M. ( 1999 ), “ A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation ”, Psychological Bulletin , Vol. 125 No. 6 , pp. 627 - 668 .

Deery , M. ( 2008 ), “ Talent management, work-life balance and retention strategies ”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 20 No. 7 , pp. 792 - 806 .

Deery , M. and Jago , L. ( 2009 ), “ A framework for work-life balance practices: addressing the needs of the tourism Industry ”, Tourism and Hospitality Research , Vol. 9 No. 2 , pp. 97 - 109 .

Deery , M. and Jago , L. ( 2015 ), “ Revisiting talent management, work-life balance and retention strategies ”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 27 No. 3 , pp. 453 - 472 .

Eriksson , T. and Li , J. ( 2009 ), “ Working at the boundary between market and flexicurity: housekeeping in Danish hotels ”, International Labour Review , Vol. 148 No. 5 , pp. 357 - 373 .

Griffeth , R.W. , Hom , P.W. and Gaertner , S. ( 2000 ), “ A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium ”, Journal of Management , Vol. 26 No. 3 , pp. 463 - 488 .

Groblena , A. and Tokarz-Kocik , A. ( 2017 ), “ Relationships between job characteristics and organizational commitment: the example of hotel housekeeping employees ”, Proceedings of the 25th International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development , pp. 491 - 500 .

Groblena , A. , Sidorkiewicz , M. and Tokarz-Kocik , A. ( 2016 ), “ Job satisfaction among hotel employees: analyzing selected antecedents and job outcomes. A case study from Poland ”, Argumenta Oeconomica , Vol. 2 No. 37 , pp. 281 - 310 , doi: 10.15611/aoe.2016.2.11 .

Hackman , J.R. and Oldham , G.R. ( 1967 ), “ Motivation through the design of work: test of a theory ”, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance , Vol. 16 No. 2 , pp. 250 - 279 .

Hackman , J.R. and Oldham , G.R. ( 1980 ), Work Redesign , Addison-Wesley , Reading, MA .

Hamermesh , D.S. ( 2001 ), “ The changing distribution of job satisfaction ”, Journal of Human Resources , Vol. 36 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 30 .

Handel , M.J. ( 2005 ), “ Trends in perceived job quality, 1989 to 1998 ”, Work and Occupations , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 66 - 94 .

Harter , J.K. , Schmidt , F.L. and Hayes , T.L. ( 2002 ), “ Business-unit level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: a meta-analysis ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 87 No. 2 , pp. 268 - 279 .

Hoffman , B.J. , Blair , C.A. , Maeriac , J.P. and Woehr , D.J. ( 2007 ), “ Expanding the criterion domain? A quantitative review of the OCB literature ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 92 No. 2 , pp. 555 - 566 .

Hom , W. and Griffeth , R.W. ( 1995 ), Employee Turnover , South-Western Publishing , Cincinnati, OH .

Hsieh , Y. Ch. , Apostolopoulos , Y. and Sönmez , S. ( 2016 ), “ Work conditions and health and well-being of Latina hotel housekeepers ”, Journal of Minority Health , Vol. 18 No. 3 , pp. 568 - 581 , doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0224-y .

Hunter-Powell , P. and Watson , D. ( 2006 ), “ Service unseen: the hotel room attendant at work ”, International Journal of Hospitality Management , Vol. 25 No. 2 , pp. 297 - 312 .

International Social Survey Program ( 2015 ), “ Work orientations IV ”, available at: https://www.gesis.org/issp/modules/issp-modules-by-topic/work-orientations/2015/ ( accessed 16 June 2020 ).

Judge , T.A. , Thoresen , C.J. , Bono , J.E. and Patton , G.K. ( 2001 ), “ The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: a qualitative and quantitative review ”, Psychological Bulletin , Vol. 127 No. 3 , pp. 376 - 407 .

Kalleberg , A. ( 1977 ), “ Work values & job rewards: a theory of job satisfaction ”, American Sociological Review , Vol. 42 , pp. 124 - 143 .

Kensbock , S. , Jennings , G. , Bailey , J. and Patiar , A. ( 2013 ), “ ‘The lowest rung’: women room attendants' perceptions of five star hotels' operational hierarchies ”, International Journal of Hospitality Management , Vol. 35 No. 2013 , pp. 360 - 368 , doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.07.010 .

Kensbock , S. , Jennings , G. , Bailey , J. and Patiar , A. ( 2016 ), “ Performing: hotel room attendants' employment experiences ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 56 No. 2016 , pp. 112 - 127 .

Knox , A. ( 2011 ), “ ‘Upstairs, downstairs’: an analysis of low paid work in Australian hotels ”, Labour and Industry , Vol. 21 No. 3 , pp. 573 - 594 .

Koys , D.J. ( 2001 ), “ The effects of employee satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior, and turnover on organizational effectiveness: a unit-level, longitudinal study ”, Personnel Psychology , Vol. 54 No. 1 , pp. 101 - 114 .

Krause , N. , Lee , P.T. , Scherzer , T. , Rugulies , R. , Sinnott , P.L. and Baker , R.L. ( 2002 ), Health and Working Conditions of Hotel Guest Room Attendants in Las Vegas , Report to the Culinary Workers Union, Local 226, Las Vegas, available at: http://www.lohp.org/docs/pubs/vegasrpt.pdf ( accessed 16 June 2020 ).

Krause , N. , Rugulies , R. and Maslach , C. ( 2010 ), “ Effort-reward imbalance at work and self-rated health of Las Vegas hotel room cleaners ”, American Journal of Industrial Medicine , Vol. 53 , pp. 372 - 386 .

Lee , P.T. and Krause , N. ( 2002 ), “ The impact of a worker health study on working conditions ”, Journal of Public Health Policy , Vol. 23 No. 3 , pp. 268 - 285 .

Locke , E.A. ( 1976 ), “ The nature and causes of job satisfaction ”, in Dunnette , M.D. (Ed.), Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology , Rand McNally , Chicago, IL , pp. 1297 - 1349 .

Maumbe , K.C. and Van Wyk , L.J. ( 2008 ), “ Employment in cape town's lodging sector: opportunities, skills requirements, employee aspirations and transformation ”, Geojournal , Vol. 73 No. 2008 , pp. 117 - 132 .

Mooney , S.K. , Harris , C. and Ryan , I. ( 2015 ), “ Long hospitality careers—a contraction in terms? ”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 28 No. 11 , pp. 2589 - 2608 , doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-04-2015-0206 .

OnsØyen , L.E. , Mykletun , R.J. and Steiro , T. ( 2009 ), “ Silenced and invisible: the work experience of room attendants in Norwegian hotels ”, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism , Vol. 9 No. 1 , pp. 81 - 102 .

Ostroff , C. ( 1992 ), “ The relationship between satisfaction, attitudes, and performance: an organizational level analysis ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 77 No. 6 , pp. 963 - 974 .

Pink , D. ( 2009 ), Drive , Riverhead Books , New York, NY .

Powell , P.H. and Watson , D. ( 2006 ), “ Service unseen: the hotel room attendant at work ”, International Journal of Hospitality Management , Vol. 25 No. 2 , pp. 297 - 312 .

Robinson , R.H.S. , Kralj , A. , Solnet , D.J. , Goh , E. and Callan , V.J. ( 2015 ), “ Attitudinal similarities and differences of hotel frontline occupations ”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 28 No. 5 , pp. 1051 - 1072 .

Ryan , A.M. , Schmit , M.J. and Johnson , R. ( 1996 ), “ Attitudes and effectiveness: examining relations at an organizational level ”, Personnel Psychology , Vol. 49 No. 4 , pp. 853 - 882 .

Schulte , M. , Ostroff , C. , Shmulyian , S. and Kinicki , S. ( 2009 ), “ Organizational climate configurations: relationships to collective attitudes, customer satisfaction, and financial performance ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 94 No. 3 , pp. 618 - 634 .

Scott , K.D. and Taylor , G.S. ( 1985 ), “ An examination of conflicting findings on the relationship between job satisfaction and absenteeism: a meta-analysis ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 28 No. 3 , pp. 599 - 612 .

Sousa-Pouza , A. and Sousa-Pouza , A.A. ( 2000 ), “ Well-being at work: a cross-national analysis of the levels and determinants of job satisfaction: ”, Journal of Socio-Economics , Vol. 29 No. 6 , pp. 517 - 538 .

Spector , P. ( 1997 ), Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences , Sage , London .

Steel , R. and Rentsch , J.R. ( 1995 ), “ Influence of cumulation strategies on the long-range prediction of absenteeism ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 38 No. 6 , pp. 1616 - 1634 .

Vandenberghe , C. , Bentein , K. , Michon , R. , Chebat , J. , Tremblay , M. and Fils , J. ( 2007 ), “ An examination of the role of perceived support and employee commitment in employee-customer encounters ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 92 No. 4 , pp. 1177 - 1187 .

Westover , J.H. ( 2012a ), “ Comparative international differences in intrinsic and extrinsic job quality characteristics and worker satisfaction, 1989–2005 ”, International Journal of Business and Social Science , Vol. 3 No. 7 , pp. 1 - 15 .

Westover , J.H. ( 2012b ), “ Comparative welfare state impacts on work quality and job satisfaction: a cross-national analysis ”, International Journal of Social Economics , Vol. 39 No. 7 , pp. 502 - 525 , doi: 10.1108/03068291211231687 .

Wolfe , K. and Kim , H.J. ( 2013 ), “ Emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, and job tenure among hotel managers ”, Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism , Vol. 12 No. 2 , pp. 175 - 191 .

Yang , J. , Wan , C. and Fu , Y. ( 2012 ), “ Qualitative examination of employee turnover and retention strategies in international tourist hotels in Taiwan ”, International Journal of Hospitality Management , Vol. 31 No. 3 , pp. 837 - 848 .

Zopiati , A. and Constanti , P. ( 2007 ), “ Human resource challenges confronting the Cyprus hospitality industry ”, EuroMed Journal of Business , Vol. 2 No. 2 , pp. 135 - 153 .

Further reading

Hausknecht , J.P. , Rodda , J. and Howard , M.J. ( 2009 ), “ Targeted employee retention: performance-based and job-related differences in reported reasons for staying ”, Human Resource Management , Vol. 48 No. 2 , pp. 269 - 288 .

Kensbock , S. , Bailey , J. , Jennings , G. and Patiar , A. ( 2015 ), “ Sexual harassment of women working as room attendants within 5-star hotels ”, Gender, Work and Organization , Vol. 22 No. 1 , pp. 36 - 50 .

Yang , I.A. , Lee , B.W. and Wu , S.T. ( 2017 ), “ The relationships among work-family conflict, turnover intention and organizational citizenship behavior in the hospitality industry of Taiwan ”, International Journal of Manpower , Vol. 38 No. 8 , pp. 1130 - 1142 .

Corresponding author

Related articles, all feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

2020: A Year of Change for Housekeeping

Housekeeping has never been more scrutinized than it has been these past six months with the onset of COVID-19. Housekeeping also has never been more difficult to execute with the continual evolution of cleaning protocols.

" Hotels are now required to follow brand mandated as well as city/state mandated cleanliness requirements," says Parminder Batra, CEO, TraknProtect . "In addition to their day-to-day duties, staff must also document and verify they have followed these requirements."

Add to this the high turnover rates found among housekeeping, and hoteliers can be facing quite a problem during a pandemic. In fact, the hospitality industry as a whole has the highest turnover rate in any industry at 74.9% − based on numbers from October 2019, says Einar Rosenberg, CIO, Creating Revolutions . This means that every year, three-quarters of a hotel’s staff has been on the job for a year or less.

So how can hoteliers help their housekeepers stay safe, informed and on top of the latest requirements? Technology seems to be the obvious answer, but not all tech solutions are great solutions.

Many back office software systems are inflexible and difficult to configure. For example, many hotels have found out the hard way that some technologies work well when the hotel is running at full capacity, but they become a hindrance to productivity and actually make life more difficult for users when the hotel is quiet or running at limited occupancy, says Katherine Grass, CEO, Optii Solutions .

Additionally, many hotels have selected “various department solutions from different tech providers, creating a disjointed system that left little room for cohesion, data collection, and developing best practices,” says Juan Carlos Abello, CEO of Nuvola .

And just because a hotel has technology in place doesn’t mean staff is well trained on using it.

“Hotels struggle with giving team members time to really learn how to make the most of their tools. The budget and team constraints brought on by COVID haven’t made this any easier,” says Adria Levtchenko, Co-Founder & CEO, PurpleCloud .

ALICE agrees, noting that hotel technology shouldn’t be “rocket science. If it’s hard to train on and use, employees won’t use it, and owners and managers aren’t going to get the results they’re looking for.”

The pandemic has brought all of these problems to the forefront, and now managers, owners and corporate staff are all looking for ways to improve the housekeeping experience: both for staff and for guests. For all the reasons listed above and more, plug-and-play solutions are particularly in high demand and housekeeping solution providers are doing their best to fill that need with product upgrades and new product rollouts. Here, Hospitality Technology takes a look at a few companies and their plug-and-play solutions.

With ALICE Housekeeping hoteliers can adjust permissions to accommodate employees filling multiple roles. With flexible user permissions, ALICE allows different employees to complete room inspections, reassign rooms and to view the room cleaning pipeline. It also offers digital checklists, dispatches requests on the go to departments with the ability to track progress, has an autopilot feature allowing the software to prioritize rooms when the supervisor is away, shows related tickets in the same view for each room, and in November 2020 will offer an opt-in stayover service which allows hotels to adapt their cleaning schedules to stop a cleaning service unless a guest specifically requests it. ALICE’s open API enables hotels to integrate with their preferred apps, tools, PMS, and more, which allows team members access to additional tools.

Creating Revolutions

This year, Creating Revolutions launched CLEANtracker, a technology that monitors employees in real-time, to make certain that all management defined protocols and processes are followed precisely every single time. CLEANtracker accomplishes this with the AI system ELROY, which uses advanced mathematics, NFC and human kinematics to identify if a job is being done correctly. It also uses that data to continually learn and optimize employee efficiency as well. It also allows hotels to provide guests with proof that their rooms have been cleaned and sanitized.

Nuvola developed and launched the StayClean Initiative , providing two free products until the end of 2020 titled Checklists and Checkpoints. Checklists facilitates any SOP that requires a list of things to do from simple tasks like security walkthroughs and daily lineups, to more complex processes like deep cleanings, room inspections, and common area inspections (i.e. gym, spa, lobby, bathrooms, etc.).

Checkpoints, which leverage QR-code technology, allows staff to automate the scheduling of which high touch-point surface areas need to be cleaned and how often they should be sanitized. Supervisors simply place the QR-codes near those surfaces like elevator buttons, handrails, doorknobs, countertops, etc., and set up the schedule inside of Nuvola. From there, staff are automatically assigned tasks via the built-in notification & escalation system. Once the staff member completes the surface cleaning, they scan the QR-code with their Nuvola app and move onto their next task.

Optii Solutions

This year, Optii Solutions released new features within its Housekeeping module to assist users in managing their “new normal” in operations. These features include a task scheduler to allow hotels to manage their stayover clean intervals and delay departure cleans to reduce staff/guest contact in guest rooms; an enhanced “extra jobs” feature to allow for hotels to schedule deep cleans and disinfectant practices while also tracking these jobs in a report to provide an audit trail to Hotel Management teams; and an enhanced “View all Jobs” feature with the housekeeping app to allow users to view a step by step guide to cleaning processes including photos and links to training videos.

PurpleCloud

Recently, PurpleCloud launched PurpleCloud CR (Covid Response), a streamlined, free version of its hotel task optimization platform, says Levtchenko. PurpleCloud CR provides hotels access to all AHLA Safe Stay guidelines as well relevant training materials, sanitation checklists that stick to guidelines set by Ecolab and the CDC, mobile messaging, and the ability to conduct contact tracing in the event a guest or staff member falls ill.

“Our COVID Response platform is entirely web-based, so it can be used on any smart device, including laptops, tablets, and smartphones,” she adds. “We also included a complete digital tour to help educate new users, so it isn’t necessary for hotels to undergo major training sessions in order to use the technology.The last thing we want to do is add complexity to operators’ daily lives, and we took that into consideration with the selection of offerings we made available.”

As health and safety documentation requirements became more essential, Quore responded with new log sheets . The Temperature Log tracks staff and/or guest temperature readings in real time according to the property’s protocols. The Restricted Area Log supports social distancing compliance by monitoring areas with capacity restrictions. Additionally, Quore’s inspection app was a vital feature to document operational compliance as new COVID cleaning requirements and brand standards evolved. It worked directly with IHG to create and distribute COVID-specific cleaning checklists and inspection templates to their properties using Quore. The templates were automatically available to IHG properties to utilize immediately. Meanwhile, Quore customers have the flexibility to create their own customized COVID templates as well. They also have access to Inspections Reports to consolidate and share their overall performance of the inspection processes. TraknProtect

This year TraknProtect launched TraknKleen a new IoT technology solution designed to help hotels enhance housekeeping operations, while providing guests with security and peace of mind while traveling. TraknKleen trilaterates data from multiple sources, such as housekeeping carts, I.D. cards, cleaning supplies, and other assets, to automatically track the date, time, and duration of the cleaning process for guestrooms and public areas in a hotel. The tool creates an audit trail for housekeeping activities, and tracks the use of designated cleaning assets, such as electrostatic sprayers in all guest areas. This allows properties using TraknKleen to share real-time access to relevant and reliable information regarding the organized and systemic delivery of property-based cleaning activities with corporate buyers, travelers and hotel brands.

“Research shows that as much as guests want enhanced cleanliness protocols they want communication around these protocols and that they are being followed,” says Parminder Batra, CEO, TraknProtect. “As a result, TraknKleen was designed to allow hotels to demonstrate that protocols are being followed and also create reminders for public areas for when an area requires to be cleaned again.”

Related Topics

- House Keeping

- Mobile Devices & Apps

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Ann Occup Environ Med

Hotel housekeepers and occupational health: experiences and perceived risks

Xènia chela-alvarez.

1 Primary Care Research Unit of Mallorca, Balearic Islands Health Service, Palma, Spain.

2 GrAPP-caIB – Health Research Institute of the Balearic Islands (IdISBa), Palma, Spain.

3 RICAPPS- Red de Investigación Cooperativa de Atención Primaria y Promoción de la Salud – Carlos III Health Institute (ISCIII), Madrid, Spain.

Oana Bulilete

Encarna garcia-illan, mclara vidal-thomàs, joan llobera.

Hotel housekeepers are one of the most important occupational group within tourism hotel sector; various health problems related to their job have been described, above all musculoskeletal disorders. The objective of this study is to understand the experiences and perceptions of hotel housekeepers and key informants from the Balearic Islands (Spain) regarding occupational health conditions and the strategies employed to mitigate them.

A qualitative study was carried out. Six focus groups with hotel housekeepers and 10 semi-structured interviews with key informants were conducted. Next, we carried out a content analysis.

Hotel housekeepers reported musculoskeletal disorders, anxiety and stress as main occupational health problems; health professionals underscored the physical problems. Hotel housekeepers perceived that their work (physically demanding and with repetitive movements) caused their health conditions. To solve health issues, they used medication (anti-inflammatory agents, painkillers, sedatives and anxiolytics), which allowed them to continue working; health public services, generally rated as satisfactory; individual protective equipment; ergonomics (with difficulties due to high work pace and hotel facilities) and physical activity. Two contrasting attitudes were identified regarding sick leave: HHs who refused to accept a doctor-prescribed sick leave (due to fear of being fired, sense of responsibility, ...), and those who accepted it (because they could not continue working, they prioritised health before work).

Conclusions

Our results might contribute to plan improvement strategies and programs to address health problems among hotel housekeepers. These programs should include interventions, such as coping strategies for the work-related risk factors (i.e., stress) and strategies to reduce medicine consumption. Additionally, hotel facilities should adopt policies focused on making workplaces more ergonomic (i.e., furniture) and to diminish the work pace.

Tourism-related jobs occupied 13.4% of the active population in Spain and 25.6% in the Balearic Islands in 2019. Within the tourism hotel sector, hotel housekeepers are one of the most important occupational group. 1 An estimated 13,000 hotel housekeepers work in the Balearic hotel industry, an exclusively female sector in Spain. 2

Most hotel housekeepers in the Balearic Islands have recurring fixed-term contracts, being employed between 6 and 9 months every year, more intensively during the summer months. Hotel housekeeping is considered physically demanding, consisting of cleaning and tidying rooms, bathrooms and common areas of hotels. Occupational health risks associated with hotel housekeeping are dominated by musculoskeletal disorders (MSD) such as low back 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 and cervical, shoulder, hands, wrists and knee pain. 1 , 5 , 8 , 9

Physical risk factors associated with MSD include: 1) Use of excessive force for lifting and moving weights—such as furniture and mattresses; 2) Forced and awkward postures 4 , 5 , 7 , 8 , 10 , 11 —adopted while making beds, when there is not enough room to follow ergonomic recommendations, cleaning the toilet, etc.; 3) Manual loading of objects 12 —including cleaning products, linen, towels and amenities to be replaced; 4) Tasks that involve elevation of the limbs or repetitive movements—i.e. when cleaning windows and shower screens; and 5) Insufficient breaks. 8 , 13

Hotel housekeepers are at high risk for MSD. The higher incidence of MSD reported in women is caused by social rather than biological differences. The horizontal and vertical segregation of the labour market concentrates women in jobs with high time pressure, heavy workload 9 , 13 , 14 and involving repetitive tasks. 15 Additionally, the workplace and equipment are usually inadequate: the design is based on male anthropometric characteristics and is often heavy and difficult to move. 9 , 15 , 16 Psychosocial hazards are related to the imbalance between demands, resources and control; mistreatment; unfair assignment of tasks. 13 , 17 Also hotel workers perceive that the organization of their work (i.e., time pressure, work overload, inadequate work equipment) has a negative impact on their physical and mental health. 9 , 17 , 18 , 19 Effort-reward imbalance has been associated with MSD 20 and with a worse perception of health among hotel housekeepers, 21 , 22 whose job is demanding, with a low decision margin and few rewards. 17 , 23 , 24

Other occupational exposure of hotel housekeepers include chemical (contact with cleaning products can cause respiratory symptoms such as nasal irritations and cough; and skin rashes outbreaks) 9 , 20 , 25 and biological hazards (contact with broken windows, needles or human waste increases the risk of workers’ infection). 26

All these exposures translate into frequent visits to the family doctor mainly due to musculoskeletal conditions, 1 , 8 , 27 , 28 anxiety and stress.

Some strategies undertaken by hotel housekeepers when they feel unwell are the use of individual protection equipment (IPE) (i.e., gloves, masks and goggles), self-medicating and consulting public health services or mutual labour health organisations—in charge of healthcare derived from professional contingencies and health leaves of working population— from which hotel housekeepers do not always obtain satisfactory responses. 2 , 9 , 14

The objective of this study is to explore the experiences and perceptions of hotel housekeepers regarding health conditions and their causes, the strategies used to solve them, and the social context in which they occur. Interestingly, compared with other occupations, few studies focus on the health problems of hotel housekeepers. Similarly, little evidence is found on the hotel housekeepers’ perception and experiences related to health problems. Our study will provide a foundation for improving the occupational health care for these workers.

We conducted a qualitative study. We carried out 10 semi-structured interviews with key informants ( Table 1 ), which provided different perspectives about hotel housekeepers’ job and their health problems. Additionally, 6 focus groups (FG) with hotel housekeepers were carried out to generate direct information about their job, the association of their health experiences with their occupation, and identified shared views. FG and interviews were moderated by the first author and were carried out between February and June 2018. The study setting was primary care (PC) centres of the Balearic Islands.

| Code | Profile | Gender | Tasks |

|---|

| HHi1 | Hotel housekeepers union members | Women | |

| HHi2 |

| HHi3 | Hotel housekeepers members of hotel housekeepers associations | Women | |

| HHi4 |

| EHK | Executive housekeeper | Women | In charge of the daily organization and distribution among hotel housekeepers of hotel housekeeping tasks. |

| GP | General practitioner in a health centre of a touristic area | Women | General practitioner working in a public health centre in an area with lots of hotels. |

| OHS | Occupational health specialist in public health service. | Women | Medical practitioner working in the public service in charge to evaluate people’s long sick leave episodes. |

| HHRR Dir. | Human resources director of a hotel chain | Women | In charge of planning and coordinating human resources of the hotel. |

| Prev. Dir | Director of prevention of occupational risk services in a hotel chain | Men | Medical practitioner in charge of the medical part of the prevention service in a hotel chain. |

| OHM | Occupational health manager of a hotel chain | Men | In charge of the service that analyse the different jobs performed in the hotel and its risks in order to take care of the workers’ health. |

Intentional sampling was used to select key informants from different unions, associations and hotels, and to obtain rich information. The interviews lasted between 25 and 80 minutes.