The Research Whisperer

Just like the thesis whisperer – but with more money, what’s on a good research project site.

It seems to be the done thing these days to have a webpage about your research project.

In fact, I think it’s fair to say that it’s considered an increasingly essential part of research engagement and dissemination, and – really – it is so easy to set something up these days.

Well…yes and no. (Stay with me, I’m a humanities scholar and that’s how we answer everything)

I had a great chat recently with a researcher who was wanting to set up an online presence for his project. Part of the task of this presence was to recruit subjects for his PhD study.

It was a valuable conversation for him (or so he tells me…!) and also for me, because it clarified our perceptions of what was necessary, good, and ideal.

What I’m talking about in this post isn’t focused on what specific funding bodies may want, or elements that fulfil project final report obligations.

I’m looking at the website as something that showcases the research project and aims to engage the right groups. I’m taking the perspective of an interested member of the public, or a non-specialist academic colleague, more than peers who are in your exact area.

There are heaps of pieces out there about how to create an effective website , but I get derailed when they keep referring to customers and brands. Put your filters in place, though, and you can still glean a lot of good info from these articles. Pat Thomson has written about her experiences with blogging her research projects , and discusses the uneven results.

This post is my take on what the basics are for a good research project website. It presumes a small to non-existent budget, and no expert team of web-design or site-construction people at your disposal.

For me, a good research project website should:

1. Make a good first impression

- how the project came about and what a great job you and your team have done in this field to make fabulous things happen.

- how people can contribute , give feedback, or participate.

- who the supporting organisations (funding or in-kind) are . Doing acknowledgements the right way encourages smooth sailing should you want to tap them for assistance in the future!

- what the ongoing outcomes and activities are for the project . Some projects use project websites for further recruitment or data-collection, as a stepping-stone to the next project, or open it up for others to contribute to. Some teams link to open access repositories, or upload PDFs of their working and conference papers.

- Plan out what streams of information you want on the site : What’s the set text? Are you going to have a Twitter feed down one side? Will you be updating news in a blog section? Don’t have too many side-bars and feature boxes fighting for attention. It will look cluttered.

- Use striking, meaningful photographs. Ensure you have quality, relevant pics on the site. Nothing worse than pages that look as if they’re populated with stock photos. Make the pictures count, and don’t have them there just to break up text (they do break up text, but they should be doing more than that). Where possible, feature ‘doing’ shots, pics that capture some process or aspect of the research.

2. Have text that is succinct, jargon-free, and well proofed.

Distil the information down to what you want to convey most, and make sure it’s stripped to core text that tells the story of your research project. Nick Feamster wrote about good storytelling for academics . While he’s talking specifically about academic papers, the advice is also relevant for nutting out website content, particularly where he talks about building the scaffold of the story. For medical science types, this listing of 10 tips for writing a lay summary is very useful.

Always run the text past another pair of eyes (or two), and get non-specialists to check its tone and whether it’s jargon-free.

3. Contain consistent team information

Present the research team’s information in a consistent manner. Don’t have reams of stuff on the lead Chief Investigator, then small paras for the rest. This is not a good look. Have the same kinds of info for each person, and definitely the same space allocated to each.

The website should feature similar profile pictures of the team (if you decide to have team photos – I like them). Have consistency in the images’ size, framing, and resolution. I’m a fan of semi-formal group shots, where the researchers look human, but aren’t hanging out in board-shorts and sculling drinks.

4. Have everything in its place

Navigation for your website should be logical and clear. I think there are some standard pages for research project websites: ‘About the Project’, ‘Contact’, ‘Supporters’ (or ‘Sponsors’), and ‘The Research Team’ (or similar). Other than these, you might have: ‘Publications’, ‘Events’, ‘Get Involved’, or ‘Updates’.

As with the website text, run the site past various people, to test whether the navigation logic you came up with actually works for a broad audience, and that there are no gaps or repetition in the information.

That should get you well started on the basics of what should be part of a good research project site. Which platform should you use? Well, Lifehacker’s ‘ Best platforms for building websites ‘ can probably give you that answer.

Want to point out something I’ve missed? Vehement objections to what I’ve said? Go on, do it in the comments!

Below are some of the research project website suggested to me when I crowdsourced for some ideas for this post on Twitter . They vary immensely in terms of how much resourcing was behind them, and how ‘academic’ they perceived their audience to be. Have a look through and see what works for you, and the kind of work you want to get out there.

Recommended research project websites:

- Framingham Heart Study (suggested by @tassie_gal)

- CelebYouth.org (suggested by @drkatyvigurs)

- Early Childhood Connect (suggested by @elfriesen)

- Culturizing Sustainable Cities (suggested by @WFGP)

- Quality in Alternative Education (suggested by @thomsonpat)

- School Accountability and Stakeholder Education (suggested by @drkatyvigurs)

Share this:

10 comments.

Very helpful. I started a blog at the beginning of the year to write about my research project for Master’s, and while looking for tips and ideas I also got sidelined by talk about brands and customers and things like that. My blog is definitely not very formal and it only involves me, but this post has made me think about a few improvements I could make.

Glad you found it useful, K.! There are some very complex (expensive) sites out there, but most of the researchers I know have no resourcing for this kind of thing. It’s good to have them up, and the more sustainable they are as sources of info/comms, the better.

Drop your project URL here – would like to check it out. 🙂

Hi Tseen, thanks for the interest. My blog is rather informal, and there are some random things around, but I describe my Master’s project here: http://kvanderwielen.wordpress.com/current-project/ . It’s really more about coming to grips with the project and how the process unfolds in South Africa. I’ve noticed that most sites and blogs available are generally aimed at PhD projects. I think this might be because most countries have moved toward a taught Masters. In South Africa most humanities subjects generally do Masters by thesis. However, a lot of what’s written for PhD candidates is helpful for us, so I’m grateful for resources like this one.

Hi Tseen, just a minor comment, but I think you will find the SASE project website is actually run by Andrew Wilkins (@andewilkins) rather than Katy Vigurs.

Hi Scott! Yes, it’s Wilkins’ project/site – Katy Vigurs suggested it (all the handles featured in the list are the suggesters from Twitter, not the investigators/project leaders). 🙂

Thanks for this helpful brief!

Happy you found it useful! Let us know if you think anything needs to be added.

Great post and step by step explanation. Keep sharing your thoughts more often

Reblogged this on Research Staff Blog .

Reblogged this on Literacy Teaching and Teacher Education and commented: I (Clare) thought this post about a research blog would be relevant for our research blog. Terrific suggestions lots of which I will follow.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Request new password

- Create a new account

The Essential Guide to Doing Your Research Project

Student resources.

Examples of Student Research Projects

- Library Catalogue

The latest news and answers to your questions about scholarly publishing and open access.

Building a website for your program of research, project, or lab? My top 10 tips

A website is a commonly used tool for knowledge mobilization for research projects and labs. I often get asked (or provide unsolicited advice!) on how to do this well. For those that don’t ask, or I haven’t connected with yet, I have put together my top ten tips.

Note: I’m a knowledge mobilization expert, not a web designer. This list is based on a non-comprehensive review of expert opinions, blog posts, and my past experience. I’ve highlighted some of my favourite resources for this work below.

1. Identify your target audience and objective for the website

With all knowledge mobilization and dissemination efforts, you should always first know what you hope to achieve and who you need to reach. This informs all your other decisions. Don’t skip this step! Need help figuring this out? Get in touch with the SFU Knowledge Mobilization Officer .

2. Assess your resources

Consider how much time, technical ability, and financial resources you have and are willing to dedicate to developing and upkeep of the website. If all are limited, then keep it basic.

3. Determine and develop the content and tone of the site

This will be informed by your audience and objective. For example, if the audience is other researchers, and the objective is to build new collaborations, you may want the content to be more technical and the tone professional. If you are looking for students, the tone might be more fun and emphasize the activities of the lab. If it is for the public, perhaps it is more plain language, informational, and engaging.

4. Avoid overcrowding

A layered structure, with brief overviews that can be clicked through to more information, is often preferable. However, avoid very complicated sites with multiple clicks to arrive at desired information. SFU’s Scholarly Communications Lab website is a nice example of how to do this well: https://www.scholcommlab.ca/

5. The layout of each page should flow, be uncluttered, and organized

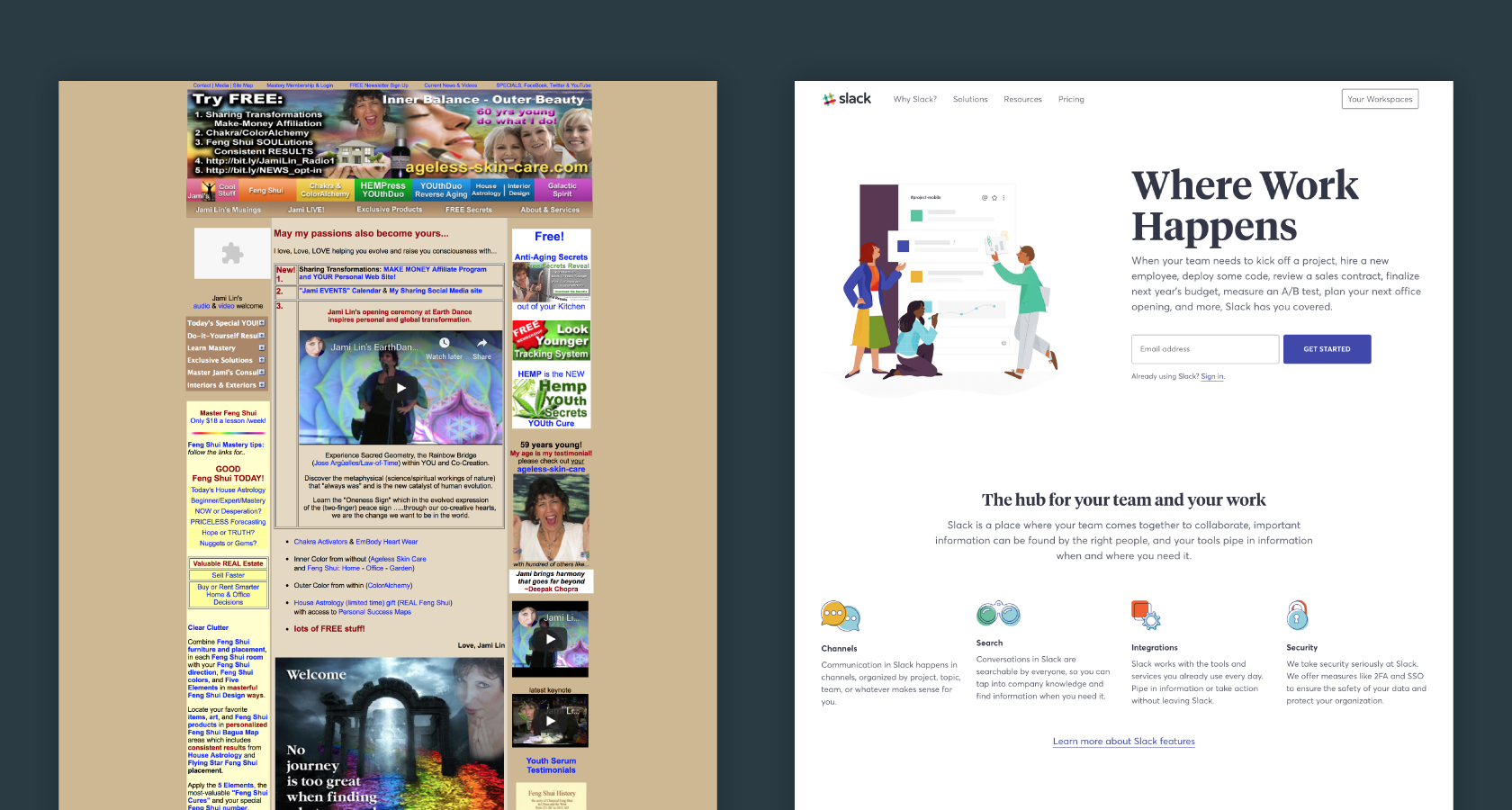

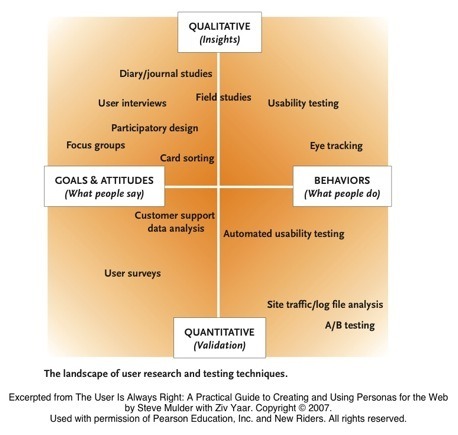

This can be achieved by organizing in a grid, column, or horizontal layout. Use negative (blank) space to facilitate readability and navigation ( scan-ability ). The image below places two websites side-by-side and illustrates why this is important to consider. Which page do you find easier to read – right or left?

6. Choose images that are specific to your research, in focus, with sufficient resolution

Include an up to date image of your team or project lead(s), and consider how your website images compliment and align with your social media accounts. For example, the website top image and your headshot could be the same as your photo and cover image on Twitter and LinkedIn. For accessibility, be sure to include alternative text that explains the image – sometimes called “alt-text.” If you are including images or graphics of humans, use diverse representation and avoid stereotypes.

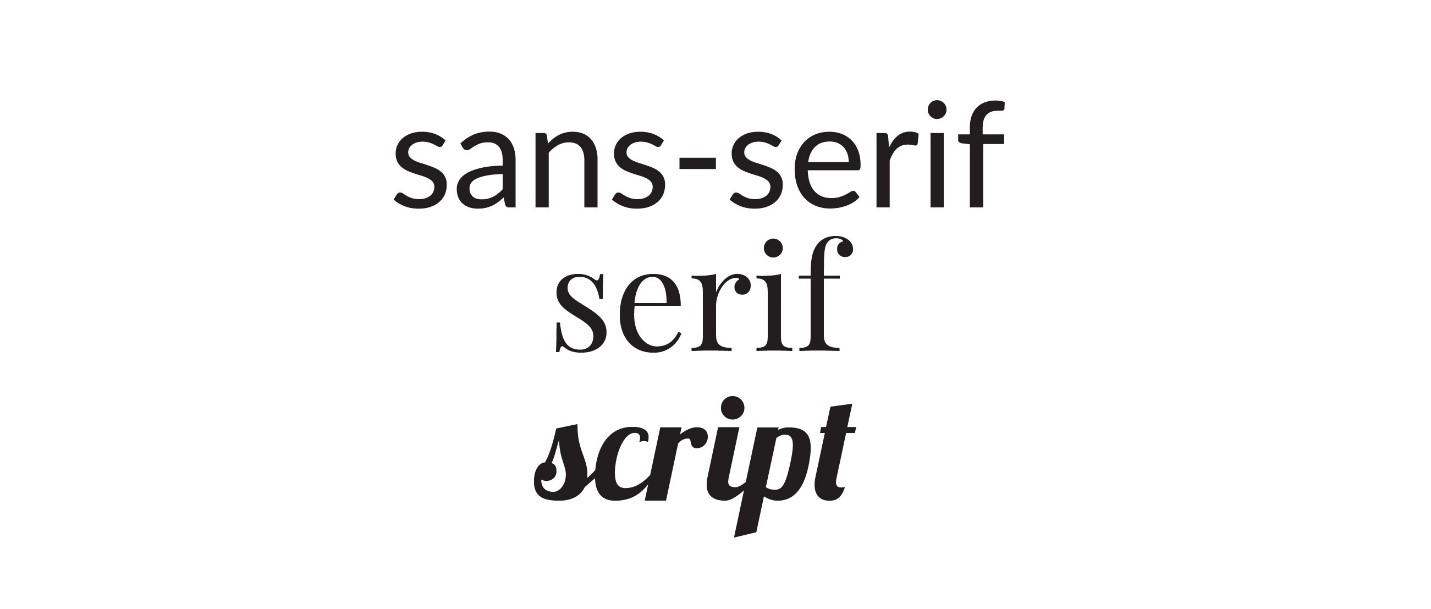

7. Use simple fonts

Choose a maximum of three complementary fonts (one for title, heading, and body). Often a sans serif font (without extra embellishments such as Helvetica) is preferable for large text (titles and headings) and serif (e.g. Times New Roman) for small text (body). Dark text on light backgrounds are easier to read and provide a more accessible experience for viewers.

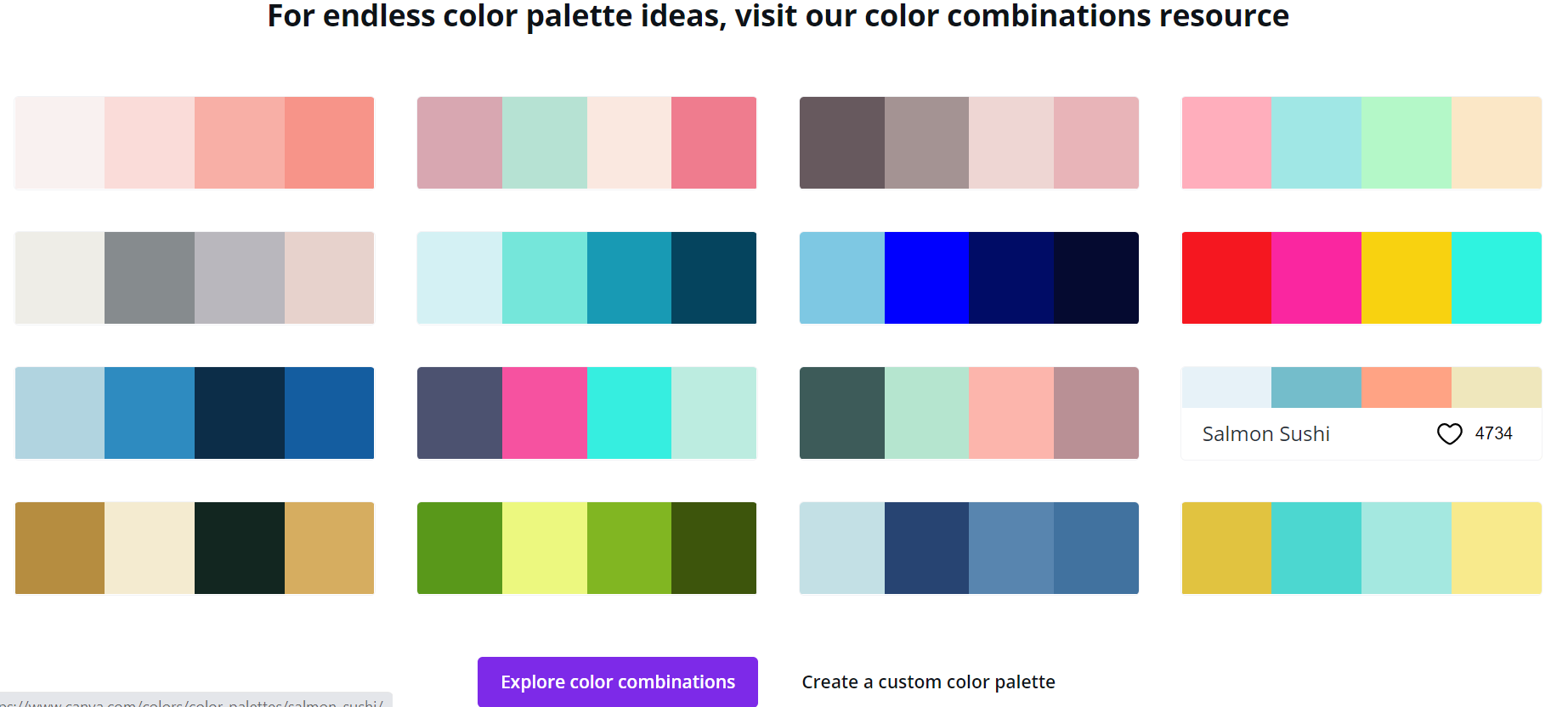

8. Pick a colour scheme of three complementary colours (and maybe an accent or two)

Choose colours that align with your audience, objective, research and tone. Check out Canva ’s colour generator for help and inspiration.

9. Consider diversity, equity, and inclusion

How we design and write can influence our audience’s sense of inclusion and more. This needs to be considered in selection and use of colours (e.g. colour blindness ), font (readability), images (think about representation and messaging), language (e.g. use inclusive and plain language ), and assumptions.

10. Get feedback and support

Reach out to available SFU resources (e.g. communicators, Knowledge Mobilization Hub, Digital Humanities Innovation Lab) for guidance and feedback. Consider hiring a professional web designer if you can afford it, and/or graphic artist. Before you launch, ask friends and colleagues to review your site.

Want to learn more?

More blog posts.

Here are some useful blog posts that dive deeper into strategies, process, and considerations:

- SFU Library’s advice on visibility and your online presence

- The Social Academic's blog post on developing your personal academic website

- The Leveraged PhD's blog post on creating a personal website

- These two blog posts offer tips from researchers on creating a good lab website by Nature and Edge for Scholars .

Resources and supports

Here are some platforms, templates, and services to get you started (paid and free):

- Designs that Cell -- A Canadian research-focused scientific illustration company.

- Science Project -- A subscription-based website platform for scientists.

- Squarespace -- Includes marketing and e-commerce features.

- Wordpress -- Very customisable but does not include hosting.

- Wix -- Allows you to build webpages using drag-and-drop features.

What does a good website look like?

It’s always good to have a few examples of websites that you like. Some of this is personal preference of course, but here are a few project or lab websites that I like:

- Chatr Lab

- Science Up First

- Amplify Podcast Network

- Multimedia Lab

Siteinspire is a whole site dedicated to the collection of creative websites. I choose a few from their list in the education and science space that might offer some inspiration:

- Whitehead Institute

- Vital Strategies

- Simons Foundation

Originally published May 14, 2021 by Lupin Battersby

Contact us : For assistance with scholarly publishing, please contact [email protected] .

Education During Coronavirus

A Smithsonian magazine special report

Science | June 15, 2020

Seventy-Five Scientific Research Projects You Can Contribute to Online

From astrophysicists to entomologists, many researchers need the help of citizen scientists to sift through immense data collections

:focal(300x157:301x158)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/ca/e2ca665f-77b7-4ba2-8cd2-46f38cbf2b60/citizen_science_mobile.png)

Rachael Lallensack

Former Assistant Editor, Science and Innovation

If you find yourself tired of streaming services, reading the news or video-chatting with friends, maybe you should consider becoming a citizen scientist. Though it’s true that many field research projects are paused , hundreds of scientists need your help sifting through wildlife camera footage and images of galaxies far, far away, or reading through diaries and field notes from the past.

Plenty of these tools are free and easy enough for children to use. You can look around for projects yourself on Smithsonian Institution’s citizen science volunteer page , National Geographic ’s list of projects and CitizenScience.gov ’s catalog of options. Zooniverse is a platform for online-exclusive projects , and Scistarter allows you to restrict your search with parameters, including projects you can do “on a walk,” “at night” or “on a lunch break.”

To save you some time, Smithsonian magazine has compiled a collection of dozens of projects you can take part in from home.

American Wildlife

If being home has given you more time to look at wildlife in your own backyard, whether you live in the city or the country, consider expanding your view, by helping scientists identify creatures photographed by camera traps. Improved battery life, motion sensors, high-resolution and small lenses have made camera traps indispensable tools for conservation.These cameras capture thousands of images that provide researchers with more data about ecosystems than ever before.

Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute’s eMammal platform , for example, asks users to identify animals for conservation projects around the country. Currently, eMammal is being used by the Woodland Park Zoo ’s Seattle Urban Carnivore Project, which studies how coyotes, foxes, raccoons, bobcats and other animals coexist with people, and the Washington Wolverine Project, an effort to monitor wolverines in the face of climate change. Identify urban wildlife for the Chicago Wildlife Watch , or contribute to wilderness projects documenting North American biodiversity with The Wilds' Wildlife Watch in Ohio , Cedar Creek: Eyes on the Wild in Minnesota , Michigan ZoomIN , Western Montana Wildlife and Snapshot Wisconsin .

"Spend your time at home virtually exploring the Minnesota backwoods,” writes the lead researcher of the Cedar Creek: Eyes on the Wild project. “Help us understand deer dynamics, possum populations, bear behavior, and keep your eyes peeled for elusive wolves!"

If being cooped up at home has you daydreaming about traveling, Snapshot Safari has six active animal identification projects. Try eyeing lions, leopards, cheetahs, wild dogs, elephants, giraffes, baobab trees and over 400 bird species from camera trap photos taken in South African nature reserves, including De Hoop Nature Reserve and Madikwe Game Reserve .

With South Sudan DiversityCam , researchers are using camera traps to study biodiversity in the dense tropical forests of southwestern South Sudan. Part of the Serenegeti Lion Project, Snapshot Serengeti needs the help of citizen scientists to classify millions of camera trap images of species traveling with the wildebeest migration.

Classify all kinds of monkeys with Chimp&See . Count, identify and track giraffes in northern Kenya . Watering holes host all kinds of wildlife, but that makes the locales hotspots for parasite transmission; Parasite Safari needs volunteers to help figure out which animals come in contact with each other and during what time of year.

Mount Taranaki in New Zealand is a volcanic peak rich in native vegetation, but native wildlife, like the North Island brown kiwi, whio/blue duck and seabirds, are now rare—driven out by introduced predators like wild goats, weasels, stoats, possums and rats. Estimate predator species compared to native wildlife with Taranaki Mounga by spotting species on camera trap images.

The Zoological Society of London’s (ZSL) Instant Wild app has a dozen projects showcasing live images and videos of wildlife around the world. Look for bears, wolves and lynx in Croatia ; wildcats in Costa Rica’s Osa Peninsula ; otters in Hampshire, England ; and both black and white rhinos in the Lewa-Borana landscape in Kenya.

Under the Sea

Researchers use a variety of technologies to learn about marine life and inform conservation efforts. Take, for example, Beluga Bits , a research project focused on determining the sex, age and pod size of beluga whales visiting the Churchill River in northern Manitoba, Canada. With a bit of training, volunteers can learn how to differentiate between a calf, a subadult (grey) or an adult (white)—and even identify individuals using scars or unique pigmentation—in underwater videos and images. Beluga Bits uses a “ beluga boat ,” which travels around the Churchill River estuary with a camera underneath it, to capture the footage and collect GPS data about the whales’ locations.

Many of these online projects are visual, but Manatee Chat needs citizen scientists who can train their ear to decipher manatee vocalizations. Researchers are hoping to learn what calls the marine mammals make and when—with enough practice you might even be able to recognize the distinct calls of individual animals.

Several groups are using drone footage to monitor seal populations. Seals spend most of their time in the water, but come ashore to breed. One group, Seal Watch , is analyzing time-lapse photography and drone images of seals in the British territory of South Georgia in the South Atlantic. A team in Antarctica captured images of Weddell seals every ten minutes while the seals were on land in spring to have their pups. The Weddell Seal Count project aims to find out what threats—like fishing and climate change—the seals face by monitoring changes in their population size. Likewise, the Año Nuevo Island - Animal Count asks volunteers to count elephant seals, sea lions, cormorants and more species on a remote research island off the coast of California.

With Floating Forests , you’ll sift through 40 years of satellite images of the ocean surface identifying kelp forests, which are foundational for marine ecosystems, providing shelter for shrimp, fish and sea urchins. A project based in southwest England, Seagrass Explorer , is investigating the decline of seagrass beds. Researchers are using baited cameras to spot commercial fish in these habitats as well as looking out for algae to study the health of these threatened ecosystems. Search for large sponges, starfish and cold-water corals on the deep seafloor in Sweden’s first marine park with the Koster seafloor observatory project.

The Smithsonian Environmental Research Center needs your help spotting invasive species with Invader ID . Train your eye to spot groups of organisms, known as fouling communities, that live under docks and ship hulls, in an effort to clean up marine ecosystems.

If art history is more your speed, two Dutch art museums need volunteers to start “ fishing in the past ” by analyzing a collection of paintings dating from 1500 to 1700. Each painting features at least one fish, and an interdisciplinary research team of biologists and art historians wants you to identify the species of fish to make a clearer picture of the “role of ichthyology in the past.”

Interesting Insects

Notes from Nature is a digitization effort to make the vast resources in museums’ archives of plants and insects more accessible. Similarly, page through the University of California Berkeley’s butterfly collection on CalBug to help researchers classify these beautiful critters. The University of Michigan Museum of Zoology has already digitized about 300,000 records, but their collection exceeds 4 million bugs. You can hop in now and transcribe their grasshopper archives from the last century . Parasitic arthropods, like mosquitos and ticks, are known disease vectors; to better locate these critters, the Terrestrial Parasite Tracker project is working with 22 collections and institutions to digitize over 1.2 million specimens—and they’re 95 percent done . If you can tolerate mosquito buzzing for a prolonged period of time, the HumBug project needs volunteers to train its algorithm and develop real-time mosquito detection using acoustic monitoring devices. It’s for the greater good!

For the Birders

Birdwatching is one of the most common forms of citizen science . Seeing birds in the wilderness is certainly awe-inspiring, but you can birdwatch from your backyard or while walking down the sidewalk in big cities, too. With Cornell University’s eBird app , you can contribute to bird science at any time, anywhere. (Just be sure to remain a safe distance from wildlife—and other humans, while we social distance ). If you have safe access to outdoor space—a backyard, perhaps—Cornell also has a NestWatch program for people to report observations of bird nests. Smithsonian’s Migratory Bird Center has a similar Neighborhood Nest Watch program as well.

Birdwatching is easy enough to do from any window, if you’re sheltering at home, but in case you lack a clear view, consider these online-only projects. Nest Quest currently has a robin database that needs volunteer transcribers to digitize their nest record cards.

You can also pitch in on a variety of efforts to categorize wildlife camera images of burrowing owls , pelicans , penguins (new data coming soon!), and sea birds . Watch nest cam footage of the northern bald ibis or greylag geese on NestCams to help researchers learn about breeding behavior.

Or record the coloration of gorgeous feathers across bird species for researchers at London’s Natural History Museum with Project Plumage .

Pretty Plants

If you’re out on a walk wondering what kind of plants are around you, consider downloading Leafsnap , an electronic field guide app developed by Columbia University, the University of Maryland and the Smithsonian Institution. The app has several functions. First, it can be used to identify plants with its visual recognition software. Secondly, scientists can learn about the “ the ebb and flow of flora ” from geotagged images taken by app users.

What is older than the dinosaurs, survived three mass extinctions and still has a living relative today? Ginko trees! Researchers at Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History are studying ginko trees and fossils to understand millions of years of plant evolution and climate change with the Fossil Atmospheres project . Using Zooniverse, volunteers will be trained to identify and count stomata, which are holes on a leaf’s surface where carbon dioxide passes through. By counting these holes, or quantifying the stomatal index, scientists can learn how the plants adapted to changing levels of carbon dioxide. These results will inform a field experiment conducted on living trees in which a scientist is adjusting the level of carbon dioxide for different groups.

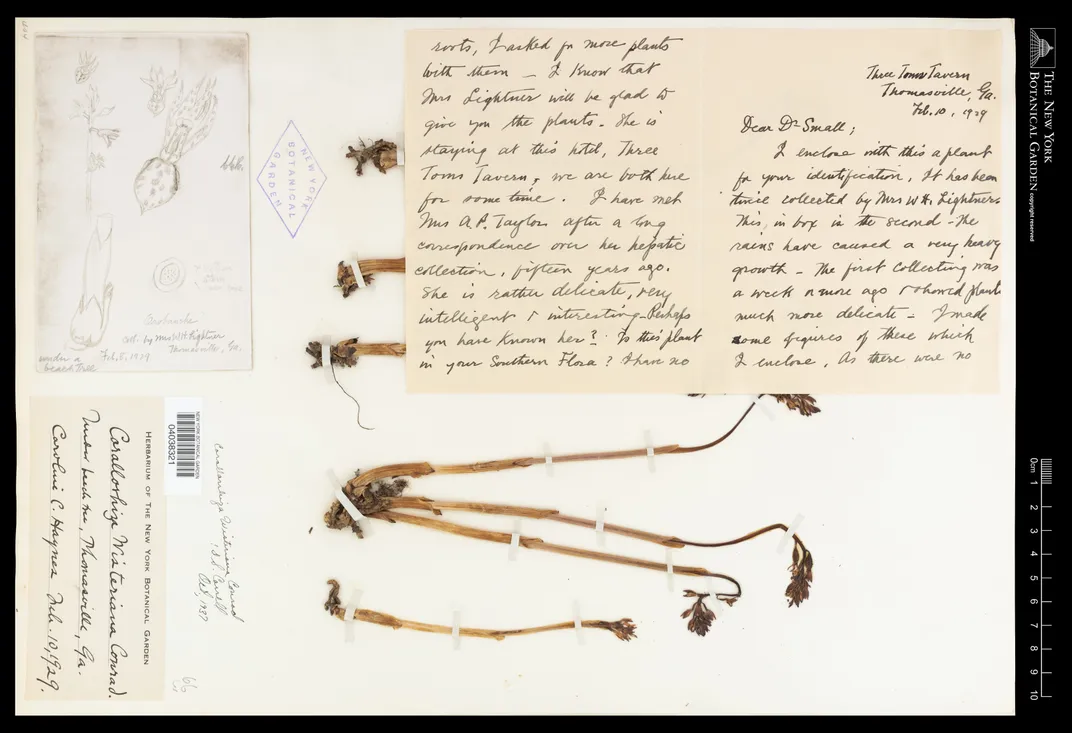

Help digitize and categorize millions of botanical specimens from natural history museums, research institutions and herbaria across the country with the Notes from Nature Project . Did you know North America is home to a variety of beautiful orchid species? Lend botanists a handby typing handwritten labels on pressed specimens or recording their geographic and historic origins for the New York Botanical Garden’s archives. Likewise, the Southeastern U.S. Biodiversity project needs assistance labeling pressed poppies, sedums, valerians, violets and more. Groups in California , Arkansas , Florida , Texas and Oklahoma all invite citizen scientists to partake in similar tasks.

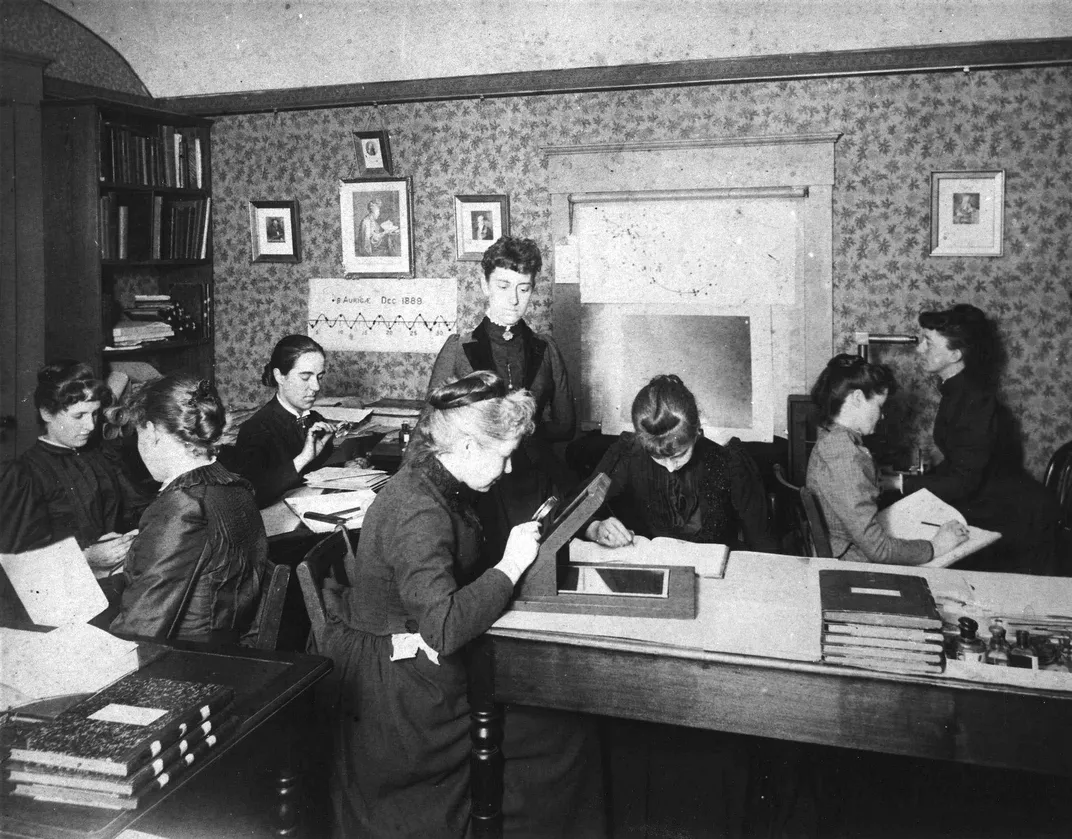

Historic Women in Astronomy

Become a transcriber for Project PHaEDRA and help researchers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics preserve the work of Harvard’s women “computers” who revolutionized astronomy in the 20th century. These women contributed more than 130 years of work documenting the night sky, cataloging stars, interpreting stellar spectra, counting galaxies, and measuring distances in space, according to the project description .

More than 2,500 notebooks need transcription on Project PhaEDRA - Star Notes . You could start with Annie Jump Cannon , for example. In 1901, Cannon designed a stellar classification system that astronomers still use today. Cecilia Payne discovered that stars are made primarily of hydrogen and helium and can be categorized by temperature. Two notebooks from Henrietta Swan Leavitt are currently in need of transcription. Leavitt, who was deaf, discovered the link between period and luminosity in Cepheid variables, or pulsating stars, which “led directly to the discovery that the Universe is expanding,” according to her bio on Star Notes .

Volunteers are also needed to transcribe some of these women computers’ notebooks that contain references to photographic glass plates . These plates were used to study space from the 1880s to the 1990s. For example, in 1890, Williamina Flemming discovered the Horsehead Nebula on one of these plates . With Star Notes, you can help bridge the gap between “modern scientific literature and 100 years of astronomical observations,” according to the project description . Star Notes also features the work of Cannon, Leavitt and Dorrit Hoffleit , who authored the fifth edition of the Bright Star Catalog, which features 9,110 of the brightest stars in the sky.

Microscopic Musings

Electron microscopes have super-high resolution and magnification powers—and now, many can process images automatically, allowing teams to collect an immense amount of data. Francis Crick Institute’s Etch A Cell - Powerhouse Hunt project trains volunteers to spot and trace each cell’s mitochondria, a process called manual segmentation. Manual segmentation is a major bottleneck to completing biological research because using computer systems to complete the work is still fraught with errors and, without enough volunteers, doing this work takes a really long time.

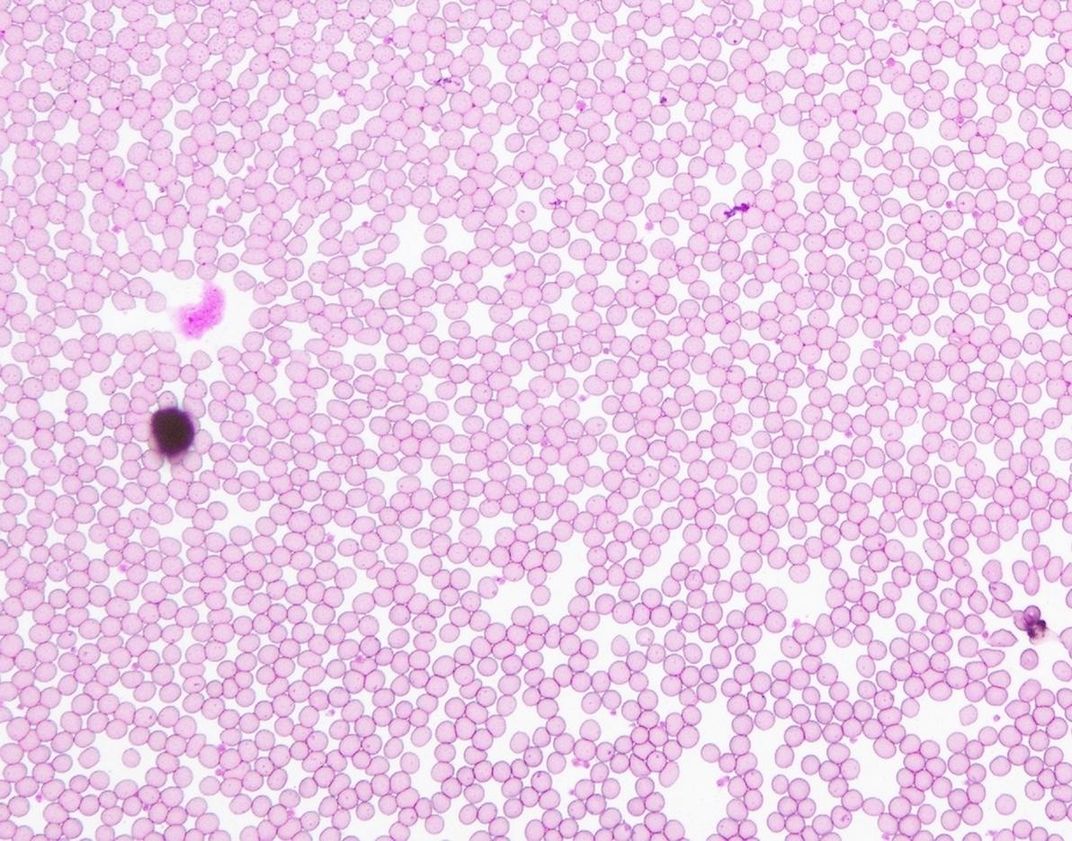

For the Monkey Health Explorer project, researchers studying the social behavior of rhesus monkeys on the tiny island Cayo Santiago off the southeastern coast of Puerto Rico need volunteers to analyze the monkeys’ blood samples. Doing so will help the team understand which monkeys are sick and which are healthy, and how the animals’ health influences behavioral changes.

Using the Zooniverse’s app on a phone or tablet, you can become a “ Science Scribbler ” and assist researchers studying how Huntington disease may change a cell’s organelles. The team at the United Kingdom's national synchrotron , which is essentially a giant microscope that harnesses the power of electrons, has taken highly detailed X-ray images of the cells of Huntington’s patients and needs help identifying organelles, in an effort to see how the disease changes their structure.

Oxford University’s Comprehensive Resistance Prediction for Tuberculosis: an International Consortium—or CRyPTIC Project , for short, is seeking the aid of citizen scientists to study over 20,000 TB infection samples from around the world. CRyPTIC’s citizen science platform is called Bash the Bug . On the platform, volunteers will be trained to evaluate the effectiveness of antibiotics on a given sample. Each evaluation will be checked by a scientist for accuracy and then used to train a computer program, which may one day make this process much faster and less labor intensive.

Out of This World

If you’re interested in contributing to astronomy research from the comfort and safety of your sidewalk or backyard, check out Globe at Night . The project monitors light pollution by asking users to try spotting constellations in the night sky at designated times of the year . (For example, Northern Hemisphere dwellers should look for the Bootes and Hercules constellations from June 13 through June 22 and record the visibility in Globe at Night’s app or desktop report page .)

For the amateur astrophysicists out there, the opportunities to contribute to science are vast. NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) mission is asking for volunteers to search for new objects at the edges of our solar system with the Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 project .

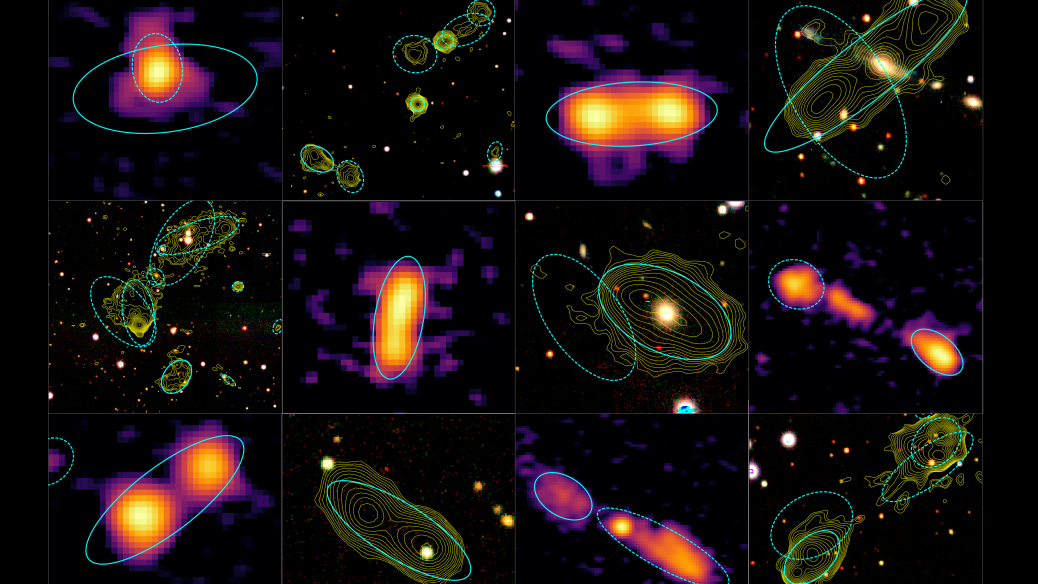

Galaxy Zoo on Zooniverse and its mobile app has operated online citizen science projects for the past decade. According to the project description, there are roughly one hundred billion galaxies in the observable universe. Surprisingly, identifying different types of galaxies by their shape is rather easy. “If you're quick, you may even be the first person to see the galaxies you're asked to classify,” the team writes.

With Radio Galaxy Zoo: LOFAR , volunteers can help identify supermassive blackholes and star-forming galaxies. Galaxy Zoo: Clump Scout asks users to look for young, “clumpy” looking galaxies, which help astronomers understand galaxy evolution.

If current events on Earth have you looking to Mars, perhaps you’d be interested in checking out Planet Four and Planet Four: Terrains —both of which task users with searching and categorizing landscape formations on Mars’ southern hemisphere. You’ll scroll through images of the Martian surface looking for terrain types informally called “spiders,” “baby spiders,” “channel networks” and “swiss cheese.”

Gravitational waves are telltale ripples in spacetime, but they are notoriously difficult to measure. With Gravity Spy , citizen scientists sift through data from Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO , detectors. When lasers beamed down 2.5-mile-long “arms” at these facilities in Livingston, Louisiana and Hanford, Washington are interrupted, a gravitational wave is detected. But the detectors are sensitive to “glitches” that, in models, look similar to the astrophysical signals scientists are looking for. Gravity Spy teaches citizen scientists how to identify fakes so researchers can get a better view of the real deal. This work will, in turn, train computer algorithms to do the same.

Similarly, the project Supernova Hunters needs volunteers to clear out the “bogus detections of supernovae,” allowing researchers to track the progression of actual supernovae. In Hubble Space Telescope images, you can search for asteroid tails with Hubble Asteroid Hunter . And with Planet Hunters TESS , which teaches users to identify planetary formations, you just “might be the first person to discover a planet around a nearby star in the Milky Way,” according to the project description.

Help astronomers refine prediction models for solar storms, which kick up dust that impacts spacecraft orbiting the sun, with Solar Stormwatch II. Thanks to the first iteration of the project, astronomers were able to publish seven papers with their findings.

With Mapping Historic Skies , identify constellations on gorgeous celestial maps of the sky covering a span of 600 years from the Adler Planetarium collection in Chicago. Similarly, help fill in the gaps of historic astronomy with Astronomy Rewind , a project that aims to “make a holistic map of images of the sky.”

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rachael.png)

Rachael Lallensack | READ MORE

Rachael Lallensack is the former assistant web editor for science and innovation at Smithsonian .

Research to Action

The Global Guide to Research Impact

Social Media

Making your research accessible

Lessons from building a research programme website: Part 1

By Nilam McGrath and Dru Riches-Magnier 22/10/2019

In this two-part blog as part of Open Access Week, Nilam McGrath and Dru Riches-Magnier outline the approach they took to develop the COMDIS-HSD website from 2012 to 2018.

Firstly, an apology. The COMDIS-HSD website that we are writing about no longer exists in the glorious form in which we left it in December 2018, but the learning we describe below, we hope, remains valuable nonetheless.

Setting up a website can be a minefield, and unless you have dedicated institutional support, or a very tech-savvy friend, it’s difficult to know where to begin. It took us four years to get the COMDIS-HSD website to where we wanted it: accessible, user-friendly, optimised for multiple devices, populated with relevant content, and looking clean and fresh. Our starting point, however, was anything but these things. Over 6 years ago, when we first started working together, the website looked very different. We changed substantial elements incrementally each year until, eventually, from 2012 to the end of the programme in December 2018, the website had been transformed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The website in 2012 (left) and after the transformation in 2018 (right).

Very different from our starting point, isn’t it? But it took us a while to get to there.

In the beginning…by Nilam

Before we outline our process and rationale, it’s worth noting that (1) I dedicated around 2–4 days per month to developing the website, and (2) Dru was hired for a minimum of 3 hours per month before I was recruited, but he hadn’t been briefed about any changes to the website for around six months by the time I was in post; a simple case of ‘The RU Manager we’re recruiting will sort it’. We continued with the 3 hours per month minimum, increasing the hours to complete certain activities as and when needed.

Top Tip 1: Carve out dedicated time each week/ month to progress website development. If either you or your supplier (or both) have very few hours to devote to specific creative projects, it’s really important that you carve out dedicated time when you will (a) complete any work needed to progress the project, and (b) communicate with each other on the progress and next steps.

Top Tip 2: Treat your website like the essential communications tool that it is. Websites aren’t a luxury anymore. They are an essential communication tool, so make its development and maintenance part of your workplan and routine; upgrades and updates are important.

Communicating with each other I used a monthly ‘rolling list’ with Dru. This was a simple list of work that needed to be completed that month, prioritised in order of importance. Typically, it was only really the first two or three activities on that list that were necessary to make huge leaps in progress each month, for example, specific actions to change the content and navigation of the journal articles page (some larger tasks would roll over into the next month). I emailed this list to Dru in the body of the email (no attachments). As Dru began completing the bigger structural changes in those early years, the list became populated with a greater number of smaller refinements that could be completed within the hours Dru had allocated for that month.

Top Tip 3: Make sure you include your website name in the subject line when you email your supplier. ‘ You’d be surprised how many clients just write “website changes” in the subject line’, Dru once said to me. ‘I deal with websites all day, every day, and some clients hire me to do more than one website, so which one are they referring to when they email me?’ I learned my lesson very quickly after that.

Our starting point The website theme had been set up in WordPress in early 2012, but it essentially lay dormant for most of the year as there was no-one in post to brief Dru. The COMDIS-HSD ‘brand’ at that stage had a dedicated YouTube channel, Twitter account, Facebook account, and various free email accounts with numerous app providers, none of which were being fully used.

Dru and I met (in a windowless basement room in London) at the beginning of 2013 to review everything. That first meeting was hugely successful simply because we met and discussed ideas, expectations, and roles in person and not over the phone; it lasted 3 hours and we flip-charted the hell out of it.

Top Tip 4: For larger or long-term projects, meet your web developer beforehand. Meeting (or at the very least, a dedicated video chat if location is an issue) before any website development begins will help you understand the web development process and share ideas. Plus, it’s just a nice thing to do; you’ll establish a good rapport and that’ll make things altogether easier in the long-term.

Our brainstorming covered everything from the website’s aim, to its content and accessibility, and we were pretty brutal in our assessment, as we were both coming at it with fresh eyes. We both knew that technology and design protocols had moved on rapidly since the first iteration of the website a year earlier. We also knew that with WordPress we had a solid, malleable platform to work with, and that Dru could make it sing and dance with some fancy coding if needed. There was one thing we couldn’t change (for now): the logo. Everything else was fair game, and there was a lot to sift through.

We knew we had to be flexible about prioritising some of the changes, and thought of it more like a house renovation (where changes in one location would possibly throw up more problems elsewhere) and so rather than become committed to a detailed implementation plan with fixed deadlines, we worked out what we could broadly do NOW, SOON and LATER – a fabulously simple prioritisation technique used by community development workers that works equally well for small-scale project planning.

Below, I outline what we focused on for the first 4 years:

In all, our initial reorganisation of the website took 8 months, and we prioritised two things:

- clarifying the structure and content; and

- making the existing documents more accessible.

Clarifying the structure and content This was really about culling; getting rid of anything I thought our audiences would find distracting or irrelevant and, crucially, structuring the layout and content by asking the following question:

How many times does a reader have to click on a link before they get to the information they want? HINT: If it’s more than two clicks, you’ll need to rethink your structure.

I asked Dru to change the font and layout throughout, whilst I worked on making the content more relevant, adding new sections on research uptake, member profiles, the embedded approach, news items, resources, and a rolling news section that Dru coded so that it displayed and updated on the homepage automatically.

Web developers are not copywriters! I wrote everything and uploaded it onto the WordPress content management system (CMS), which I used to refer to as ‘the backend’ of the website. The ‘backend’ is not a technical term, it’s just my idiotic name for the CMS ( editor’s note: that’s what we call it at R2A too! ), but it made Dru laugh. Whenever I uploaded new content and it went ‘live’, if it looked a bit weird, or a link didn’t work, or the alignment was off somewhere, that’s when I would email Dru a link to that page with clear instructions on any specific changes I needed.

The major change that year was the structure of the ‘journal articles’ page to include a more sophisticated search function and user-friendly layout. The existing page read like a poorly formatted bibliography, with incorrect, broken, and non-existent links (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The website’s journal articles page in 2012 (left) and 2018 (right).

The ‘before and after’ are poles apart. Honestly, when I saw what Dru had developed, I wanted to give him a medal. His inspired design was clean and led with the titles of each article rather than the authors. The new layout meant that if readers were interested in the article, then they could expand their selection to read more, and click through to the article hosted on the site. This meant that it was much easier to collate metrics about our articles from journal websites – for both our researchers and funders.

Other smaller changes – all ideas from Dru based on his extensive experience – included adding a cookie policy, ‘This is really important!’ he said (a legal requirement in the EU); experimenting with Google analytics (he was really patient explaining analytics to me); and experimenting with other platforms to share information.

These initial changes to structure and content meant that we moved from a static website to an interactive one with links to existing resources within a year. This included linking our YouTube channel to the website and using a new Flickr account to share previously unseen photos of fieldwork and research.

Making the existing documents more accessible I knew from my conversations with partners, and from both reviewing logframe targets and writing the RU strategy and operational plan for the consortium, that the publications portfolio was going to become large over the next 4 years while the project was active. The go-to format for outputs is the PDF, but creating a PDF for each output didn’t sit well with me: a wall of PDFs can look somewhat impenetrable if structured poorly on a website and it creates ‘PDF fatigue’ or ‘blindness’. But I also knew that, for lots of reasons, this was the preferred format for many partners for NOW. The idea of experimenting with alternative formats to a PDF was something for LATER. To make existing information more accessible NOW, I edited existing content using plain English principles and continued writing new content along the same lines.

My instinct about PDF fatigue/blindness turned out to be correct. A 2014 study by the World Bank showed that 31% of policy documents are never downloaded, and this could be attributed to the dreaded PDF format, a theory elaborated on in this Priceonomics article.

For these reasons I tried to counter convention by providing other ways to view research findings, particularly for people with poor internet connections and low bandwidth.

During my research I came across excellent guidance from Aptivate about designing websites and uploading content for users where low bandwidth is an issue (both poor internet connections or little or very expensive access to data on mobile devices). This led to my decision to also upload HTML versions of our documents, the slight deviation being with health guidelines which were uploaded as Word documents so health workers could adapt them easily. PDFs are data heavy and HTML was a smart way to ensure quick and easy access. Over time, our stats showed that the HTML versions of our briefs were approximately three times more popular than the PDFs.

This small but powerful change was one of many that I made over the years to ensure that the broader portfolio of outputs was accessible to institutions and individuals with fewer resources; a strategy that was commended by DFID in their programme completion report.

Another way of making our work accessible was duplicating our portfolio on an external site. With one eye on the future, I knew that the website would eventually be shelved in an institutional repository and perhaps not exist at all after the end of the programme, so it was important that the research evidence remained available on an easy-to-use platform.

I did some research and settled on Scribd as a parallel platform; it could act as a useful backup for all our outputs should our website go into meltdown. Scribd allowed readers to download our briefs, guides, and grey literature for free. (It has recently started promoting a premium membership scheme that charges readers a monthly fee, but it is still possible to read and download documents for free if you open an account to upload documents.)

It was while exploring Scribd that I thought about replicating their thumbnail and description view on our website, particularly for our briefs and guides. Dru had created what I thought was a flexible and user-friendly format for the publications page, so I asked him to experiment. True to form, he delivered something that was exactly right (see Figures 3 and 4):

Figure 3: A resource page before the change (left), and after (right) with the thumbnails and descriptions.

Figure 4: Guides before (left) and after (right), including icons to indicate the type of resource.

Many of the more fundamental changes were complete by the third year, so I continued to update the content, including revising every project brief and making these available as low-bandwith HTML versions. During this year, the website had over 10k page views, with almost 7.5k unique views. Our most popular pages were the journal articles and the project pages that contained all the rewritten project briefs.

I knew that the programme funding was coming to an end this year, so my aim was to make sure that everything was as accessible as possible beyond the end of the programme. This meant converting as many documents as possible to HTML, making the creative commons licensing more prominent, and populating the site with research findings and evidence of uptake, news, resources, and other grey literature. I viewed this year as a chance to consolidate the legacy of the consortium. This meant addressing two specific internal concerns:

- The COMDIS-HSD acronym was not readily understood.

- The original logo didn’t actually state that COMDIS-HSD was a health consortium, but the masthead did.

Dru had already changed the background of the website to add more white space, and he suggested extending the white background to the masthead; a simple and effective solution to make the website less ‘top heavy’ that we could implement quickly and easily (see Figure 5). I suggested making some changes to the logo and strapline, which senior management approved, so we hired designers to produce new artwork that met our brief.

Figure 5: The original logo and masthead didn’t explain the COMDIS-HSD acronym (top), but the new ones made it clear (bottom).

At the end of year, at the eleventh hour, our programme secured funding for another 2 years. At that stage, I felt good about where the site was at in terms of its look, feel, and content.

The extension brought with it a new set of challenges. Funders like to change things up now and again, and the programme extension came with a new set of indicators to monitor website metrics. This therefore became the year of investing in analytics. We had done basic monitoring before to report against our logframe indicators, but now the funder wanted a lot more detail.

To help capture information about and describe our users a little better, Dru adapted a quick and simple pop-up download form (see Figure 6) that he had designed for our partners Malaria Consortium and integrated this into our website.

Figure 6: Pop-up form to capture audience information.

He also made our site design responsive to the many sizes and types of devices that people now use to access information.

Year 6 and our end point

The final year, and another stocktake. Social media and related analytics were a big part of our reporting, yet our Twitter presence had remained modest and was not very targeted. With a clear skills gap in our team, I recruited a dedicated digital communications officer. The positive impact was pretty much immediate: there was a dissemination schedule in place, our existing evidence was reaching more targeted groups, our evidence was being shared and commented upon online, our download capture form was helping us to identify our audiences and our most popular resources, and there was much more work on defining the analytics that our funder needed.

The most important development this year came for our partners ARK Foundation . They were ready to redevelop their website completely, and they liked our website. So, after some detailed conversations, we all thought: Why re-invent the wheel? Why not replicate our website for them? And so, that’s what happened, and here it is: https://arkfoundationbd.org/

For the second time in 2 years, I worked on consolidating the legacy of the consortium and on making the content accessible for policymakers, medical staff, implementing organisations, and researchers. As I’d predicted many years before, the site was to be archived by the university, which involved around 6 months of negotiation beforehand (another learning curve).

And then, it all came to an end. As I stated at the start of this article, our overall approach to making research evidence accessible via our website was commended by DFID, which I’m extremely proud of. I learned so much working with Dru and I couldn’t have achieved my vision for the website without his knowledge and expert skills. So, in addition to the top tips above, I would add that a good web developer is worth their weight in gold. I will also add one final top tip:

Top Tip 5: G ood communication and understanding between you and your web developer is key.

In Part 2 of this blog (appearing on R2A on Thursday, October 24th), Dru offers some golden advice on what you need to think about when developing your organisation’s website.

Contribute Write a blog post, post a job or event, recommend a resource

Partner with Us Are you an institution looking to increase your impact?

Most Recent Posts

- Africa’s use of evidence: challenges and opportunities

- Five ways to improve policy engagement

- Youth-focused initiatives: SheDecides.

- Monitoring and Evaluation tools for Advocacy and Influencing

- Harnessing AI in the Evaluation Life Cycle

As part of our new Youth Inclusion and Engagement Space we are profiling some of the initiatives having real impact in this area. First up it's @GAGEprogramme... Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence (GAGE) is a groundbreaking ten-year research initiative led by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI). From 2015 to 2025, GAGE is following the lives of 20,000 adolescents across six low- and middle-income countries in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, generating the world’s largest dataset on adolescence. GAGE’s mission is clear: to identify effective strategies that help adolescent boys and girls break free from poverty, with a strong focus on the most vulnerable, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). By understanding how gender norms influence young people’s lives, GAGE provides invaluable insights to inform policies and programs at every level. The program has already made significant impacts. GAGE evidence was instrumental in shaping Ethiopia's first National Plan on Adolescent and Sexual Reproductive Health and enhancing UNICEF’s Jordan Hajati Cash for Education program. Beyond policy change, GAGE elevates youth voices through their podcast series, exploring topics like civic engagement, activism, and leadership. In crisis contexts like Gaza, GAGE advocates for the inclusion of adolescents in peace processes, addressing the severe mental health challenges and social isolation faced by young people, particularly girls. GAGE also fosters skill development and research opportunities for youth, encouraging young researchers to publish their work. Impressively, around half of GAGE’s outputs have co-authors from the Global South. 👉 Learn more about GAGE’s impactful work by following the Youth Inclusion link on our Linktree. 🔗🔗

The latest #R2AImpactPractitioners post features an article by Karen Bell and Mark Reed on the Tree of Participation (ToP) model, a groundbreaking framework designed to enhance inclusive decision-making. By identifying 12 key factors and 7 contextual elements, ToP empowers marginalized groups and ensures processes that are inclusive, accountable, and balanced in power dynamics. The model uses a tree metaphor to illustrate its phases: roots (pre-process), branches (process), and leaves (post-process), all interconnected within their context. Discover more by following the #R2Aimpactpractitioners link in our linktree 👉🔗

Do you use AI in your work? AI is increasingly present in all our lives, but how can we use it effectively to enhance research practice? Earlier this year Inés Arangüena explored this question in a two part series. Follow the link in our bio to read more. https://ow.ly/IV0R50SH5tI #AI

Research To Action (R2A) is a learning platform for anyone interested in maximising the impact of research and capturing evidence of impact.

The site publishes practical resources on a range of topics including research uptake, communications, policy influence and monitoring and evaluation. It captures the experiences of practitioners and researchers working on these topics and facilitates conversations between this global community through a range of social media platforms.

R2A is produced by a small editorial team, led by CommsConsult . We welcome suggestions for and contributions to the site.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Our contributors

Browse all authors

Friends and partners

- Global Development Network (GDN)

- Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

- International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie)

- On Think Tanks

- Politics & Ideas

- Research for Development (R4D)

- Research Impact

- Professional Services

- Real Estate

- Financial Advisor

- Construction

- Recruitment

- Physiotherapy

- Makeup & Cosmetics

- Beauty Salon

- Travel Agency

- Vacation Rental

- Coming Soon

- Promotional Page

- Café & Bakery

- Bar & Club

- Food & Drinks

- Landscaping

- Self Storage

- Woodworking

- Accessories

- Electronics

- Grocery Store

- Listings & Classifieds

- WooCommerce

- Architecture

- Illustration

- Fashion Design

- Arts & Crafts

- Graphic Design

- Interior Design

- Singer & Musician

- DJ & Producer

- Videographer

- Colleges & Universities

- Online Education

- Online Courses

- Online Forum

- Association

- Conferences

- Event Production

- Fundraising

- Personal Blog

- Fashion Blog

- Travel Blog

- News & Magazine

- Blank Templates

- All Templates

Research Website Templates

Research Lab

Laboratory Research

Health Website

Copywriting & Researching App

Agency Website

Digital Agency

Book Writer

These Research Website Templates Are Perfect For

- Academic Institutions : Universities and colleges can use these templates to showcase their research projects, scientific breakthroughs, and scholarly articles, improving their visibility and credibility.

- Nonprofit Research Organizations : These organizations can use research website templates to publish their findings, solicit donations, and engage the public in their cause.

- Market Research Firms : Such firms can leverage these templates to display their case studies, methodologies, and services offered, helping to attract potential clients.

- Medical Research : Research website templates can help medical institutions and pharmaceutical companies share their latest findings, clinical trial results, and health studies with the public or professionals in the field.

- Environmental Research : Organizations dedicated to studying climate change, conservation, and other environmental issues can use these templates to disseminate information, educate the public, and advocate for change.

- Tech Research : Tech companies and startups can use these templates to showcase their innovation and research, attracting investors, clients, and talented professionals.

- Independent Researchers : Individuals conducting independent research can use these templates to share their work, findings, and theories, inviting feedback and collaboration from others in their field.

- Think Tanks : These policy institutes can use research website templates to publish their research papers, discuss policy proposals, and host online debates or discussions.

- Research Journals : Academic and industry journals can use these templates to present articles, call for papers, and provide subscription options.

- Government Research : Government agencies can use these templates to publish their research on various subjects, enhancing transparency and fostering public trust.

In essence, research website templates are an essential tool for anyone looking to present research work professionally, disseminate knowledge, and engage with a broader audience.

Dr Martin Lea

Examples of Academic and Author Websites

These are some examples of Academic and Author websites I have designed for my clients. Click the Read More button for screenshots of internal pages and details of the client's requirements and my solutions.

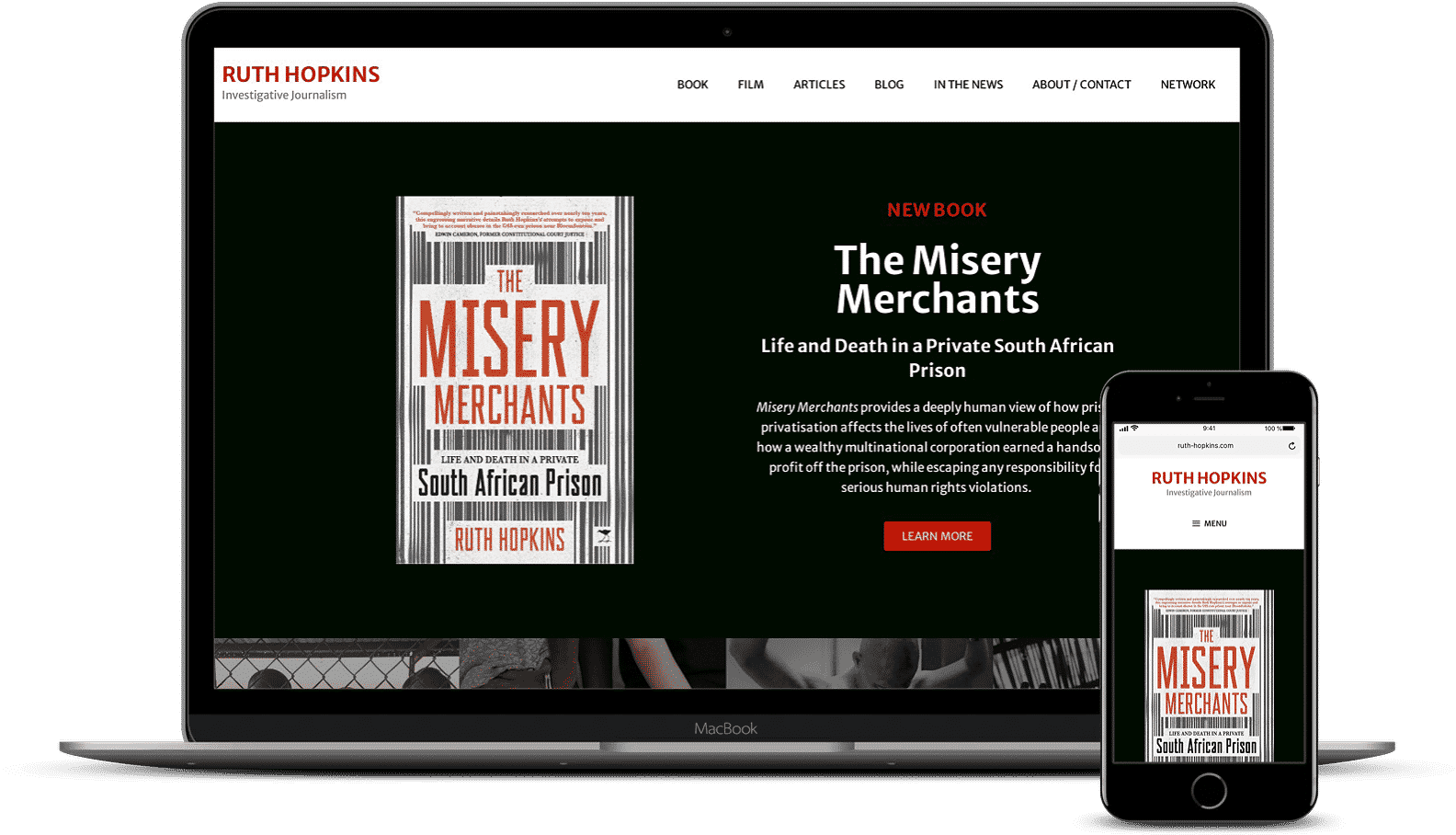

Ruth's Author Website

Ruth's an investigative journalist. She wanted a website to promote her latest book and film projects, and also present an archive of her published articles. We chose a strong, clean style, and a structure for all her work that was easy to browse.

Sandra's Personal Academic Website

Sandra's a psychology professor. She wanted a personal academic website to present her outreach activities alongside her research and publications. We chose a bold, magazine style design that headlined her latest activities, and presented a news blog of her work.

Len's Therapist Website

Len wanted a website to provide information about his personal counselling service, and a way for potential clients to contact him easily. It was important to keep the design clean, light, and easy to use, and the project within his limited budget.

Carola's Book Website

Carola wanted a website to publicise her first published book, and sell it directly through her website. We designed her site around the artwork she had commissioned for her book cover. We included several elements to inform about the book, including a video trailer, sample downloadable chapter, and reviews.

Project Outreach Website

This is an example of a website emanating from a research project that was built to provide information for end users. In this text-heavy site we use plenty of white space to lighten the experience. The home page displays the different categories of information available, together with a prominent newsletter opt-in form, and a disclaimer.

Website Managed Hosting and Site Care

Ruth Yeoman already had a personal academic website, but she wanted someone who understood her professional needs to look after all the technical aspects of hosting and maintaining her site, and at an affordable price. Read what I did, as well as full details of my Site Care plans.

Book Launch Event Website

This was an urgent project for a book launch and author website. Working with the client over email and phone, we completed the project in a day. Includes links to order the book, details of the Launch event on Zoom – including a useful countdown timer, descriptions of the book and the author, book reviews, and a registration form for the event.

Interested in Working together? Contact me to discuss your website

If you'd like to learn more about how I could help you realise your website, please click the button below and fill in my contact form.

Download My Disaster Resources

Enter Your email to access and download

- Full-text articles and Full length reports (PDF)

- Reference lists and Endnote Bibliographies

- Survey items and Questionnaires

- Checklists and Recommendations

Get notified about new resources when I add them

- About University of Sheffield

- Campus life

- Accommodation

- Student support

- Virtual events

- International Foundation Year

- Pre-Masters

- Pre-courses

- Entry requirements

- Fees, accommodation and living costs

- Scholarships

- Semester dates

- Student visa

- Before you arrive

- Enquire now

How to do a research project for your academic study

- Link copied!

Writing a research report is part of most university degrees, so it is essential you know what one is and how to write one. This guide on how to do a research project for your university degree shows you what to do at each stage, taking you from planning to finishing the project.

What is a research project?

The big question is: what is a research project? A research project for students is an extended essay that presents a question or statement for analysis and evaluation. During a research project, you will present your own ideas and research on a subject alongside analysing existing knowledge.

How to write a research report

The next section covers the research project steps necessary to producing a research paper.

Developing a research question or statement

Research project topics will vary depending on the course you study. The best research project ideas develop from areas you already have an interest in and where you have existing knowledge.

The area of study needs to be specific as it will be much easier to cover fully. If your topic is too broad, you are at risk of not having an in-depth project. You can, however, also make your topic too narrow and there will not be enough research to be done. To make sure you don’t run into either of these problems, it’s a great idea to create sub-topics and questions to ensure you are able to complete suitable research.

A research project example question would be: How will modern technologies change the way of teaching in the future?

Finding and evaluating sources

Secondary research is a large part of your research project as it makes up the literature review section. It is essential to use credible sources as failing to do so may decrease the validity of your research project.

Examples of secondary research include:

- Peer-reviewed journals

- Scholarly articles

- Newspapers

Great places to find your sources are the University library and Google Scholar. Both will give you many opportunities to find the credible sources you need. However, you need to make sure you are evaluating whether they are fit for purpose before including them in your research project as you do not want to include out of date information.

When evaluating sources, you need to ask yourself:

- Is the information provided by an expert?

- How well does the source answer the research question?

- What does the source contribute to its field?

- Is the source valid? e.g. does it contain bias and is the information up-to-date?

It is important to ensure that you have a variety of sources in order to avoid bias. A successful research paper will present more than one point of view and the best way to do this is to not rely too heavily on just one author or publication.

Conducting research

For a research project, you will need to conduct primary research. This is the original research you will gather to further develop your research project. The most common types of primary research are interviews and surveys as these allow for many and varied results.

Examples of primary research include:

- Interviews and surveys

- Focus groups

- Experiments

- Research diaries

If you are looking to study in the UK and have an interest in bettering your research skills, The University of Sheffield is a world top 100 research university which will provide great research opportunities and resources for your project.

Research report format

Now that you understand the basics of how to write a research project, you now need to look at what goes into each section. The research project format is just as important as the research itself. Without a clear structure you will not be able to present your findings concisely.

A research paper is made up of seven sections: introduction, literature review, methodology, findings and results, discussion, conclusion, and references. You need to make sure you are including a list of correctly cited references to avoid accusations of plagiarism.

Introduction

The introduction is where you will present your hypothesis and provide context for why you are doing the project. Here you will include relevant background information, present your research aims and explain why the research is important.

Literature review

The literature review is where you will analyse and evaluate existing research within your subject area. This section is where your secondary research will be presented. A literature review is an integral part of your research project as it brings validity to your research aims.

What to include when writing your literature review:

- A description of the publications

- A summary of the main points

- An evaluation on the contribution to the area of study

- Potential flaws and gaps in the research

Methodology

The research paper methodology outlines the process of your data collection. This is where you will present your primary research. The aim of the methodology section is to answer two questions:

- Why did you select the research methods you used?

- How do these methods contribute towards your research hypothesis?

In this section you will not be writing about your findings, but the ways in which you are going to try and achieve them. You need to state whether your methodology will be qualitative, quantitative, or mixed.

- Qualitative – first hand observations such as interviews, focus groups, case studies and questionnaires. The data collected will generally be non-numerical.

- Quantitative – research that deals in numbers and logic. The data collected will focus on statistics and numerical patterns.

- Mixed – includes both quantitative and qualitative research.

The methodology section should always be written in the past tense, even if you have already started your data collection.

Findings and results

In this section you will present the findings and results of your primary research. Here you will give a concise and factual summary of your findings using tables and graphs where appropriate.

Discussion

The discussion section is where you will talk about your findings in detail. Here you need to relate your results to your hypothesis, explaining what you found out and the significance of the research.

It is a good idea to talk about any areas with disappointing or surprising results and address the limitations within the research project. This will balance your project and steer you away from bias.

Some questions to consider when writing your discussion:

- To what extent was the hypothesis supported?

- Was your research method appropriate?

- Was there unexpected data that affected your results?

- To what extent was your research validated by other sources?

Conclusion

The conclusion is where you will bring your research project to a close. In this section you will not only be restating your research aims and how you achieved them, but also discussing the wider significance of your research project. You will talk about the successes and failures of the project, and how you would approach further study.

It is essential you do not bring any new ideas into your conclusion; this section is used only to summarise what you have already stated in the project.

References

As a research project is your own ideas blended with information and research from existing knowledge, you must include a list of correctly cited references. Creating a list of references will allow the reader to easily evaluate the quality of your secondary research whilst also saving you from potential plagiarism accusations.

The way in which you cite your sources will vary depending on the university standard.

If you are an international student looking to study a degree in the UK , The University of Sheffield International College has a range of pathway programmes to prepare you for university study. Undertaking a Research Project is one of the core modules for the Pre-Masters programme at The University of Sheffield International College.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the best topic for research .

It’s a good idea to choose a topic you have existing knowledge on, or one that you are interested in. This will make the research process easier; as you have an idea of where and what to look for in your sources, as well as more enjoyable as it’s a topic you want to know more about.

What should a research project include?

There are seven main sections to a research project, these are:

- Introduction – the aims of the project and what you hope to achieve

- Literature review – evaluating and reviewing existing knowledge on the topic

- Methodology – the methods you will use for your primary research

- Findings and results – presenting the data from your primary research

- Discussion – summarising and analysing your research and what you have found out

- Conclusion – how the project went (successes and failures), areas for future study

- List of references – correctly cited sources that have been used throughout the project.

How long is a research project?

The length of a research project will depend on the level study and the nature of the subject. There is no one length for research papers, however the average dissertation style essay can be anywhere from 4,000 to 15,000+ words.

- Thesis Action Plan New

- Academic Project Planner

Literature Navigator

Thesis dialogue blueprint, writing wizard's template, research proposal compass.

- Why students love us

- Rebels Blog

- Why we are different

- All Products

- Coming Soon

How to Start a Research Project: A Step-by-Step Guide

Starting a research project can feel overwhelming, but breaking it down into manageable steps can make it easier. This guide will walk you through each stage, from choosing a topic to preparing for your final presentation. By following these steps, you'll be well on your way to completing a successful research project.

Key Takeaways

- Choose a topic that interests you and is feasible to research.

- Develop clear research questions and objectives to guide your study.

- Conduct a thorough literature review to understand the existing research.

- Create a detailed research plan with a timeline and methodology.

- Engage with stakeholders and incorporate their feedback throughout the project.

Choosing a Research Topic

Identifying research interests.

Start by thinking about what excites you. Pick a topic that you find fun and fulfilling . This will keep you motivated throughout your research. Make a list of subjects you enjoy and see how they can relate to your field of study.

Evaluating Topic Feasibility

Once you have a few ideas, check if they are too broad or too narrow. A good topic should be manageable within the time you have. Ask yourself if you can cover all aspects of the topic in your thesis.

Consulting with Advisors

If you have difficulty finding a topic, consult with your advisors. Present your ideas to them and seek their guidance. They can provide valuable insights and help you refine your topic to ensure it is both engaging and manageable.

Defining the Research Problem

Formulating research questions.

Once you have a topic, the next step is to formulate research questions . These questions should target what you want to find out. They can focus on describing, comparing, evaluating, or explaining the research problem. A strong research question should be specific enough to be answered thoroughly using appropriate methods. Avoid questions that can be answered with a simple "yes" or "no".

Justifying the Research Problem

After formulating your research questions, you need to justify why your research problem is important . Explain the significance of your research in the context of existing literature. Highlight the gaps your research aims to fill and how it will contribute to the field. This step is crucial for crafting a compelling research proposal.

Setting Research Objectives

Finally, set clear research objectives. These are the specific goals you aim to achieve through your research. They should align with your research questions and provide a roadmap for your study. Establishing well-defined objectives will make it easier to create a research plan and stay on track throughout the research process.

Conducting a Comprehensive Literature Review

Finding credible sources.

Start by gathering reliable sources for your research. Use academic databases, libraries, and journals to find books, articles, and papers related to your topic. Make sure to evaluate the credibility of each source. Primary sources like published articles or autobiographies are firsthand accounts, while secondary sources like critical reviews are more removed.

Analyzing Existing Research

Once you have your sources, read through them and take notes on key points. Look for different viewpoints and how they relate to your research question. This will help you understand the current state of research in your field. Skimming sources initially can save time; set aside useful ones for a full read later.

Identifying Research Gaps

Identify areas that haven't been explored or questions that haven't been answered. These gaps can provide a direction for your own research. For example, if you're studying the impact of WhatsApp on communication, look for what hasn't been covered in existing studies. This will make your research more valuable and original.

Developing a Detailed Research Plan

Creating a solid research plan is crucial for the success of your thesis . It helps you stay organized and ensures that you cover all necessary aspects of your research.

Engaging with Stakeholders

Identifying key stakeholders.

To start, you need to identify all the key stakeholders involved in your research project. Stakeholders can include funders, academic supervisors, and anyone who will be affected by your study. Identifying potential resistance early on can help you address concerns before they become major issues.

Conducting Stakeholder Meetings

Once you have identified your stakeholders, the next step is to conduct meetings with them. These meetings are crucial for understanding their needs and expectations. Here are some steps to ensure productive meetings:

- Identify all stakeholders : Make a list of everyone affected by your project, including customers and end users.

- Keep communication open: Regular updates and open discussions help in aligning everyone's expectations.

- Present your project plan: Explain how your plan addresses stakeholders' expectations and be open to feedback.

- Determine roles: Decide who needs to see which reports and how often, and identify which decisions need approval and by whom.

Incorporating Stakeholder Feedback