WeHeartCBT is a collection of resources aimed at helping children and young people who are struggling with symptoms of anxiety and/or low mood. Resources are based on a Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) approach and are for mental health professionals, schools and parents/families.

Related resources

Organisations that can help, chat health.

It’s safe and easy for you to speak to a qualified health professional. Just send a message, you don’t have to give your name.

Kooth is free, safe and anonymous online mental wellbeing community.

It's free to text Shout on 85258 from all major mobile networks in the UK anytime, day or night. Your messages are confidential and anonymous.

Whether you want to understand more about how you're feeling and find ways to feel better, or you want to support someone who's struggling, Youngminds can help.

Are you, or is a young person you know, not coping with life? For confidential suicide prevention advice contact HOPELINE247.

The Mix can help you take on any challenge you’re facing - from mental health to money, from homelessness to finding a job, from break-ups to drugs.

Whatever you're going through, you can contact the Samaritans for support. This is a listening service and does not offer advice or intervention.

Get help and advice about a wide range of issues. Call 0800 1111, talk to a counsellor online, send Childline an email or post on the message boards.

The Psychology Square

Affordable Mental Wellness is Possible!

Explore The Psychology Square for Support.

- December 19, 2023

20 Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Techniques with Examples

Muhammad Sohail

Table of contents.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) stands as a powerful, evidence-based therapeutic approach for various mental health challenges. At its core lies a repertoire of techniques designed to reframe thoughts, alter behaviors, and alleviate emotional distress. This article explores 20 most commonly used cbt techniques. These therapy techniques are scientifcally valid, diverse in their application and effectiveness, serve as pivotal tools in helping individuals navigate and conquer their mental health obstacles.

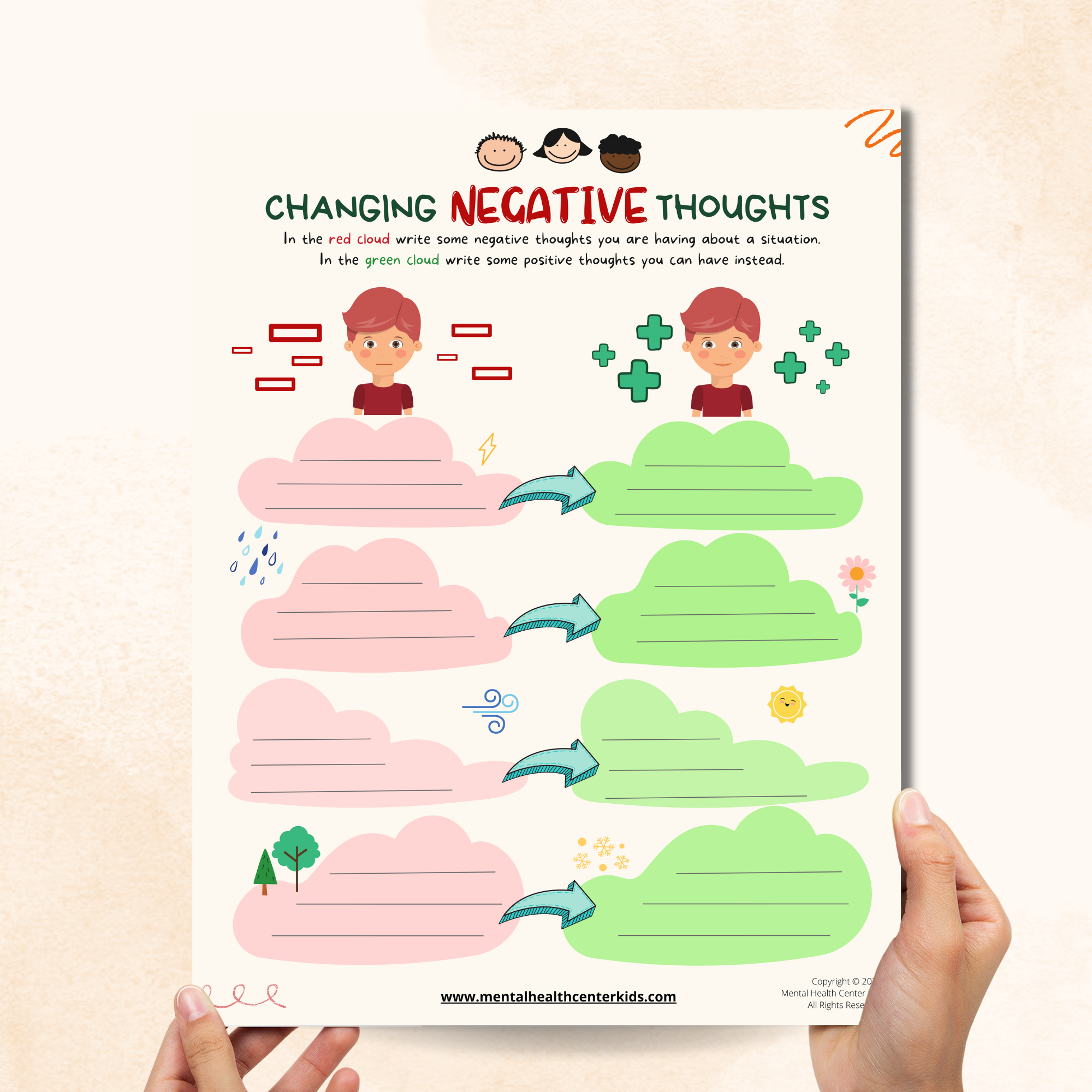

Cognitive Restructuring or Reframing:

This is the most talked about of all cbt techniques. CBT employs cognitive restructuring to challenge and alter negative thought patterns. By examining beliefs and questioning their validity, individuals learn to perceive situations from different angles, fostering more adaptive thinking patterns.

John, feeling worthless after a rejected job application, questions his belief that he’s incompetent. He reflects on past achievements and reframes the situation, realizing the rejection doesn’t define his abilities.

Guided Discovery:

In guided discovery, therapists engage individuals in an exploration of their viewpoints. Through strategic questioning, individuals are prompted to examine evidence supporting their beliefs and consider alternate perspectives, fostering a more nuanced understanding and empowering them to choose healthier cognitive pathways.

During therapy, Sarah explores her fear of failure. Her therapist asks, “What evidence supports your belief that you’ll fail? Can we consider alternate outcomes?” Guided by these questions, Sarah acknowledges her exaggerated fears and explores more balanced perspectives.

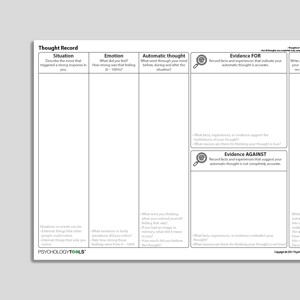

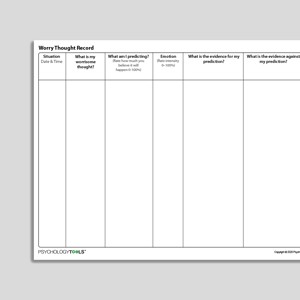

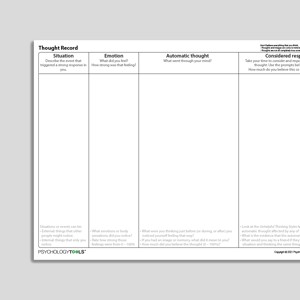

Journaling and Thought Records:

Writing exercises like journaling and thought records aid in identifying and challenging negative thoughts. Tracking thoughts between sessions and noting positive alternatives enables individuals to monitor progress and recognize cognitive shifts.

James maintains a thought journal. Between sessions, he records negative thoughts about social situations. He then challenges these thoughts, jotting down positive alternatives and notices a shift in his mindset.

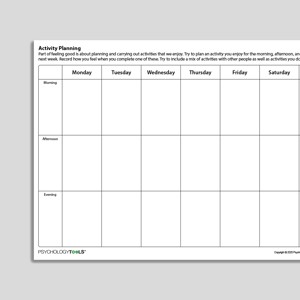

Activity Scheduling and Behavior Activation:

By scheduling avoided activities and implementing learned strategies, individuals establish healthier habits and confront avoidance tendencies, fostering behavioral change.

Emily, struggling with social anxiety, schedules coffee outings with friends. By implementing gradual exposure, she confronts her fear and eventually feels more comfortable in social settings.

Relaxation and Stress Reduction Techniques:

CBT incorporates relaxation techniques like deep breathing, muscle relaxation, and imagery to mitigate stress. These methods equip individuals with practical skills to manage phobias, social anxieties, and stressors effectively.

David practices deep breathing exercises when faced with work stress. By incorporating this technique into his routine, he manages work-related anxiety more effectively.

Successive Approximation:

Breaking overwhelming tasks into manageable steps cultivates confidence through incremental progress, enabling individuals to tackle challenges more effectively.

Maria, overwhelmed by academic tasks, breaks down her study sessions into smaller, manageable sections. As she masters each segment, her confidence grows, making the workload seem more manageable.

Interoceptive Exposure:

This technique targets panic and anxiety by exposing individuals to feared bodily sensations, allowing for a recalibration of beliefs around these sensations and reducing avoidance behaviors.

Tom, experiencing panic attacks, deliberately induces shortness of breath in a controlled setting. As he tolerates this discomfort without avoidance, he realizes that the sensation, though distressing, is not harmful.

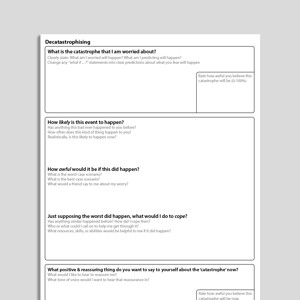

Play the Script Until the End:

Encouraging individuals to envision worst-case scenarios helps alleviate fear by demonstrating the manageability of potential outcomes, reducing anxiety.

Facing fear of public speaking, Rachel imagines herself stumbling during a presentation. By playing out this scenario mentally, she realizes that even if it happens, it wouldn’t be catastrophic.

Shaping (Successive Approximation):

Shaping involves mastering simpler tasks akin to the challenging ones, aiding individuals in overcoming difficulties through gradual skill development.

Chris, struggling with public speaking, begins by speaking to small groups before gradually addressing larger audiences. Each step builds his confidence for the next challenge.

Contingency Management:

This method utilizes reinforcement and punishment to promote desirable behaviors, leveraging the consequences of actions to shape behavior positively.

To encourage healthier eating habits, Sarah rewards herself with a favorite activity after a week of sticking to a balanced diet.

Acting Out (Role-Playing):

Role-playing scenarios allow individuals to practice new behaviors in a safe environment, facilitating skill development and desensitization to challenging situations.

Alex, preparing for a job interview, engages in role-playing with a friend. They simulate the interview scenario, allowing Alex to practice responses and manage anxiety.

Sleep Hygiene Training:

Addressing the link between depression and sleep problems, this technique provides strategies for improving sleep quality, a critical aspect of mental well-being.

Lisa, struggling with sleep, follows sleep hygiene recommendations. She creates a calming bedtime routine and eliminates screen time before sleep, noticing improvements in her sleep quality.

Mastery and Pleasure Technique:

Encouraging engagement in enjoyable or accomplishment-driven activities serves as a mood enhancer and distraction from depressive thoughts.

After feeling low, Mark engages in gardening (a mastery activity) and then spends time painting (a pleasure activity). He finds joy in these activities, which uplifts his mood.

Behavioral Experiments:

This technique involves creating real-life experiments to test the validity of certain beliefs or assumptions. By actively exploring alternative thoughts or behaviors, individuals gather concrete evidence to challenge and modify their existing perspectives.

Laura believes people judge her negatively. She experiments by initiating conversations at social gatherings and observes that most interactions are positive, challenging her belief.

Externalizing:

Externalizing helps individuals separate themselves from their problems by giving those issues an identity or persona. This technique encourages individuals to view their problems as separate entities, facilitating a more objective approach to problem-solving.

Adam, dealing with anger issues, visualizes his anger as a separate entity named “Fury.” This helps him view his emotions objectively and manage them more effectively.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT):

ACT combines mindfulness strategies with commitment and behavior-change techniques. It focuses on accepting difficult thoughts and emotions while committing to actions aligned with personal values, promoting psychological flexibility.

Sarah practices mindfulness exercises to accept her anxiety while committing to attend social events aligned with her values of connection and growth.

Imagery-Based Exposure:

This technique involves mentally visualizing feared or distressing situations, allowing individuals to confront and manage their anxieties in a controlled, imaginative setting.

Jack, afraid of flying, visualizes being on a plane, progressively picturing the experience in detail until he feels more comfortable with the idea of flying.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR):

MBSR incorporates mindfulness meditation and awareness techniques to help individuals manage stress, improve focus, and enhance overall well-being by staying present in the moment.

Rachel practices mindfulness meditation daily. By focusing on the present moment, she reduces work-related stress and enhances her overall well-being.

Systematic Desensitization:

Similar to exposure therapy, systematic desensitization involves pairing relaxation techniques with gradual exposure to anxiety-inducing stimuli. This process helps individuals associate relaxation with the feared stimuli, reducing anxiety responses over time.

Michael, with a fear of heights, gradually exposes himself to elevators first, then low floors in tall buildings, gradually working up to higher levels, reducing his fear response.

Narrative Therapy:

Narrative therapy focuses on separating individuals from their problems by helping them reconstruct and retell their life stories in a more empowering and positive light, emphasizing strengths and resilience.

Emily reevaluates her life story by focusing on instances where she overcame challenges, emphasizing her resilience and strength rather than her setbacks.

Each of these CBT techniques plays a unique role in helping individuals transform their thoughts, behaviors, and emotions. While some focus on cognitive restructuring, others emphasize behavioral modification or stress reduction. Together, they form a comprehensive toolkit empowering individuals to navigate their mental health challenges and foster positive change in their lives.

more insights

Addiction Recovery and the Role of Society’s Perception of Mental Health

Discover how society’s perception of mental health impacts addiction recovery. Learn ways to support positive change in mental health.

Addiction Treatment: Trauma-Informed Care

Explore the concept of trauma-informed care and find out how this method is reshaping the world of addiction treatment.

The Availability Heuristic: Cognitive Bias in Decision Making

The availability heuristic is a cognitive bias that affects decision-making based on how easily information can be recalled or accessed.

How CBT Empowers Individuals to Overcome Mental Health Challenges

In this article

Today, the prevalence of mental health challenges is undeniable, and it affects individuals from all walks of life. Anxiety disorders, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder ( OCD ) and post-traumatic stress disorder ( PTSD ) are just a few among the range of conditions that millions deal with daily.

According to the mental health charity Mind , 8 in 100 are diagnosed with mixed anxiety and depression in any given week in England. However, reports suggest that only 1 in 3 receive treatment (talking therapies, medication or both) for their condition.

Fortunately for many, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) helps. Renowned for its effectiveness, CBT offers individuals a pathway to healing, equipping them with invaluable tools to navigate and overcome the labyrinth of mental health challenges.

In this article, we’ll explore the transformative power of CBT and how it enables individuals to confront and conquer their innermost demons, fostering resilience and reclaiming agency over their lives.

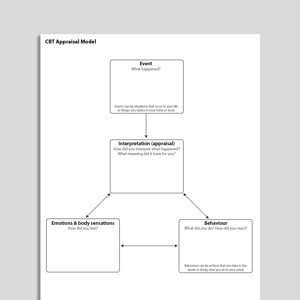

The Foundations of CBT

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) was pioneered by Beck (1970) and Ellis (1962). So, although it seems relatively new as a concept, its origins are decades old.

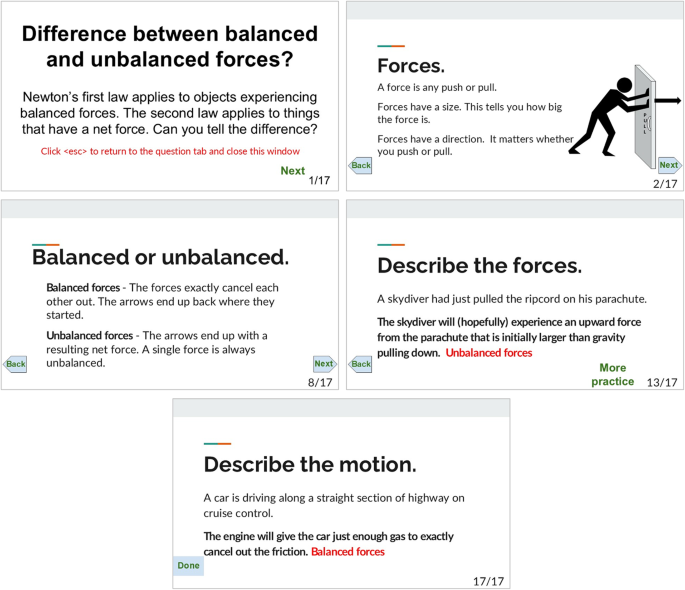

At the centre of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) are fundamental principles that form the foundation of its transformative approach. Central to CBT is the cognitive model, a framework that elucidates the intricate interplay between thoughts, emotions and behaviours. This model underscores the notion that our interpretations of events profoundly influence our emotional responses and subsequent actions. In essence, it posits that how we perceive and interpret situations shapes our emotional state and dictates our behavioural responses.

CBT places particular emphasis on identifying and challenging negative thought patterns. It recognises them as potent catalysts for distress and dysfunction. By concentrating on these cognitive distortions—like catastrophic thinking, black-and-white thinking and over-generalisation—CBT forces individuals to scrutinise the accuracy and validity of their thoughts. Through this process of cognitive restructuring, they learn to replace maladaptive beliefs with more rational, balanced perspectives. This then alleviates emotional distress and forms adaptive behaviours.

In essence, the cognitive model guides CBT. It illuminates the delicate web of connections between our thoughts, emotions and behaviours. By harnessing the power of cognitive restructuring , CBT equips individuals with the tools to rewrite the narratives of their inner dialogue, developing resilience and empowering them to live life’s challenges with clarity and confidence.

Empowering Self-Help

One of the distinguishing features of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is its emphasis on individuals taking an active role in their own recovery. Rather than passively accepting their circumstances, CBT empowers them to become agents of change. It provides them with a versatile toolkit so they can explore the complexities of their mind.

The practical application of CBT techniques allows individuals to challenge and reframe unhelpful thoughts, manage emotions effectively and make meaningful changes in their behavioural patterns. Through collaborative exploration and experimentation, individuals learn to identify cognitive distortions and erroneous beliefs that fuel their distress. With this awareness, they then engage in cognitive restructuring, systematically dismantling negative thought patterns and replacing them with more adaptive and realistic alternatives.

Moreover, CBT develops emotion regulation skills. It provides individuals with strategies to cope with intense feelings such as anxiety, sadness or anger. By learning to recognise, tolerate and modulate their emotional responses, people gain a sense of mastery over their inner workings and can reduce the grip that overwhelming emotions have on their lives.

As well as addressing cognitive and emotional dimensions, CBT places significant emphasis on behavioural change. Through structured goal setting and gradual exposure exercises, individuals confront avoidance behaviours and maladaptive coping mechanisms. They expand their comfort zones and gradually reclaim control over their lives.

In essence, CBT is a catalyst for self-empowerment. It offers individuals the tools and knowledge they need for their own mental well-being. CBT instils hope and resilience and paves the way for enduring transformation and growth.

Coping Strategies

Within the framework of CBT there is a diverse array of coping strategies introduced. These aim to empower individuals to confront and overcome their mental health challenges. These strategies aren’t just theoretical concepts, they’re practical tools that help individuals understand the complexities of their minds.

Central to CBT’s arsenal of coping strategies is cognitive restructuring. This is a process that involves identifying and challenging distorted or irrational thoughts. By examining the evidence for and against their beliefs, individuals can gradually dismantle their negative thought patterns and replace them with more balanced and adaptive perspectives. This cognitive reframing empowers individuals to reinterpret their experiences and circumstances in a way that creates resilience and promotes psychological well-being.

Besides cognitive restructuring, CBT often incorporates behavioural experiments. These involve systematically testing the validity of one’s beliefs through real-life experiences. By engaging in structured activities or interactions designed to challenge their assumptions, individuals gather concrete evidence that contradicts their negative predictions. This then undermines the power of their anxiety or distress.

Exposure therapy is another aspect of CBT. This is used for anxiety disorders, particularly phobias and PTSD. Through gradual and systematic exposure to feared stimuli or situations, individuals learn to confront and tolerate their fears. This helps them to lower their anxiety response over time. Known as desensitisation, this process allows individuals to reclaim control over their lives so that they are no longer controlled by their anxieties.

Collectively, these coping strategies exemplify the empowering nature of CBT. They provide individuals with the tools and techniques needed to confront their fears and anxieties head-on.

Goal Setting

Goal setting is an important part of CBT. It provides individuals with a plan for their recovery. These goals are specific, measurable objectives that individuals work towards with the guidance and support of their therapist.

Goal setting in CBT is about creating a sense of purpose and direction. By articulating specific and achievable objectives, individuals gain clarity about what they hope to accomplish, and the steps required to get there. This process gives their journey meaning and intentionality and it helps them to feel a level of control over their circumstances.

Setting achievable goals in CBT also promotes a sense of accountability and motivation. As individuals progress towards their objectives, they experience a tangible sense of accomplishment. This reinforces their belief in their capacity to effect change. This positive feedback loop fuels their momentum and resilience and spurs them on.

Importantly, the process of goal setting in CBT is collaborative. Individuals and therapists work together to define realistic and meaningful objectives. By aligning goals with the individual’s values, preferences and strengths, therapy becomes a personalised experience and is tailored to the unique needs and aspirations of the individual.

Setting goals for CBT isn’t just about symptom reduction; it is about reclaiming agency and authorship over your life. When patients can see a future filled with possibility and chart a course towards it, they can learn new ways of seeing themselves and their situation.

Effectiveness of CBT

According to research by the University of Bristol, 43% of people who received CBT reported a 50% reduction (or more) in their symptoms of depression. For those who didn’t receive CBT, only 27% reported reduced symptoms in the same 46-month period.

Let’s take a look at some of the specific results of CBT for different problems:

- Addiction and substance misuse: There is some evidence to suggest that CBT for cannabis use is effective compared to other interventions. It was also found that those quitting smoking were less likely to relapse with CBT.

- Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders: There was found to be a beneficial effect of CBT on positive symptoms like delusions and hallucinations.

- Depression and dysthymia: CBT for depression was found to be more effective than control conditions. CBT and medication treatments were found to have similar effects on chronic depressive symptoms.

- Bipolar disorder: There were small effects on bipolar disorder but only if CBT is used as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy.

- Anxiety disorders: CBT for social anxiety disorder has been shown to improve this condition, and for generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), it was superior to pill placebo conditions. For post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), it was shown to be just as good as eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing.

- Eating disorders: For bulimia nervosa, CBT did have positive effects, but it was found to be less effective than behaviour therapy. However, it fared much better in remission response rates.

- Insomnia: CBT is well-known to be effective in reducing insomnia.

- Anger and aggression: CBT is moderately effective at reducing problems with anger. It is said to be most effective when there are issues with people expressing their anger.

Why is it effective?

At the heart of CBT’s efficacy is its emphasis on empowering individuals to adapt to challenges and setbacks. This creates a more resilient mindset among those who practise it.

One of the key tenets of this therapy is recognising that resilience is a skill that can be developed. Through structured interventions and guided practice, individuals learn to navigate adversities with greater flexibility and resourcefulness. This means they’re less likely to succumb to feelings of despair or hopelessness.

CBT is successful because it gives individuals a range of coping strategies and problem-solving skills. These skills allow them to confront and overcome obstacles. By learning how to challenge negative thought patterns and reframe their interpretations of events, individuals learn to perceive setbacks as temporary and surmountable, rather than insurmountable barriers.

CBT encourages a more positive outlook on life. It encourages individuals to focus on their strengths and resources instead of dwelling on their perceived deficiencies or limitations. Through a process of cognitive restructuring, individuals learn to develop a mindset of gratitude, optimism and self-compassion. This enhances their resilience in the face of adversity.

CBT also focuses on the importance of behavioural activation. This means that it encourages people to engage in activities that bring them joy and fulfilment—even when they’re in the midst of difficult circumstances. By reconnecting with their interests, individuals regain a sense of purpose and meaning in their lives. This further improves their resilience and strength.

In essence, CBT offers individuals the skills and mindset needed to deal with challenges with grace and resilience. Thanks to CBT, by having a more adaptive outlook on life, individuals can overcome their struggles and imagine a future filled with hope and possibility.

Collaborative Approach

Although CBT requires a lot of effort from the individual, it is centred on a collaborative partnership between the person and their therapist. This is based on mutual respect, empathy and shared decision-making.

Unlike traditional therapeutic approaches where the therapist assumes a more directive role, CBT embraces a collaborative ethos. It recognises the expertise and agency the individual has in their own healing journey. Individuals are active participants in the therapeutic process. They work hand-in-hand with trained therapists or counsellors to co-create their treatment plans and ensure they’re tailored to their unique needs and goals.

This collaborative approach is grounded in the belief that individuals are the experts of their own experiences. After all, they possess invaluable insights and perspectives that can inform the direction of therapy.

From the outset, therapists engage in a collaborative dialogue with individuals. They seek to understand their concerns, aspirations and preferences. Together, they identify the specific challenges and goals to guide the course of therapy and they ensure that interventions are relevant and meaningful to the individual’s lived experience.

Throughout the therapeutic journey, individuals are encouraged to actively engage in self-reflection and experimentation. They’re expected to try to apply the skills and techniques learned in therapy to their daily lives. The therapists are guides and facilitators; they offer guidance, feedback and support throughout the process.

The collaborative nature of CBT means that it also extends beyond the confines of the therapy room. The individual’s broader support network of family, friends and other healthcare professionals should also be involved in some way. This helps create a unified approach and reinforces the progress made.

In summary, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a powerful therapy for many individuals who undertake it. First and foremost, CBT is a potent tool for reclaiming agency and control over one’s mental health journey. By equipping individuals with practical coping strategies and problem-solving skills, CBT allows them to challenge negative thought patterns, manage emotions effectively and make meaningful behavioural changes.

CBT also helps with the development of resilience. It enables individuals to adapt to challenges and setbacks with grace and strength. Through collaborative exploration and experimentation, individuals learn to confront their fears, overcome obstacles and cultivate a more positive outlook on life.

CBT Awareness

Study online and gain a full CPD certificate posted out to you the very next working day.

Take a look at this course

About the author

Louise Woffindin

Louise is a writer and translator from Sheffield. Before turning to writing, she worked as a secondary school language teacher. Outside of work, she is a keen runner and also enjoys reading and walking her dog Chaos.

Similar posts

Best Practices for Storing and Managing Student Records Securely

Recognising the Early Signs of Dyslexia in Children

Techniques for Supporting Loved Ones Battling Depression

Strategies for Parents Coping with the Loss of a Child

Celebrating our clients and partners.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a form of psychotherapy that focuses on modifying dysfunctional emotions, behaviors, and thoughts by interrogating and uprooting negative or irrational beliefs. Considered a "solutions-oriented" form of talk therapy, CBT rests on the idea that thoughts and perceptions influence behavior.

Feeling distressed, in some cases, may distort one’s perception of reality. CBT aims to identify harmful thoughts, assess whether they are an accurate depiction of reality, and, if they are not, employ strategies to challenge and overcome them.

CBT is appropriate for people of all ages, including children, adolescents, and adults. Evidence has mounted that CBT can address numerous conditions, such as major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, post- traumatic stress disorder, eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and many others.

CBT is a preferred modality of therapy among practitioners and insurance companies alike as it can be effective in a brief period of time, generally 5 to 20 sessions, though there is no set time frame. Research indicates that CBT can be delivered effectively online, in addition to face-to-face therapy sessions.

- CBT in Practice

- What Conditions Can CBT Treat?

- The Origins of CBT

CBT focuses on present circumstances and emotions in real time, as opposed to childhood events. A clinician who practices CBT will likely ask about family history to get a better sense of the entire person, but will not spend inordinate time on past events. The emphasis is on what a person is telling themselves that might result in anxiety or disturbance. A person is then encouraged to address rational concerns practically, and to challenge irrational beliefs, rumination or catastrophizing .

For example, a person who is upset about being single will be encouraged to take concrete measures but also question any undue negativity or unwarranted premise ("I will be alone forever") that they attach to this present-day fact.

For more on psychotherapy in practice, visit the Therapy Center.

A typical course of CBT is around 5 to 20 weekly sessions of about 45 minutes each. Treatment may continue for additional sessions that are spaced further apart, while the person keeps practicing skills on their own. The full course of treatment may last from 3 to 6 months, and longer in some cases if needed.

In therapy, patients will learn to identify and challenge harmful thoughts, and replace them with a more realistic, healthy perspective. Patients may receive assignments between sessions, such as exercises to observe and recognize their thought patterns, and apply the skills they learn to real situations in their life.

CBT programs tend to be structured and systematic, which makes it more likely that a person gets an adequate “dose” of healthy thinking and behaviors. For example, a patient with depression may be asked to write down the thoughts he has when something upsetting happens, and then to work with the therapist to test how helpful and accurate the thoughts are. Repeated and focused practice is an integral part of CBT. CBT centers around building new habits—which we may know but need to remember and implement successfully.

Additionally, CBT programs can be standardized and tested so that the mental health field can identify which programs are effective, how long they take, and the benefits that patients can expect.

Research has found the CBT delivered virtually is often equally as effective, and sometimes more effective, than CBT delivered in person. For example, one review study found that online CBT reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression to the same extent or more than in person CBT. Online CBT was also effective in treating post- traumatic stress disorder, panic disorder, and specific phobia . Given that online therapy removes certain barriers, such as travel time or childcare, it’s a strong option to consider.

For more, see Online Therapy.

Almost everyone deals with distracting or destructive thoughts at times, but cognitive and behavioral principles can help you overcome them. The first goal is to restructure exaggerations. You can cultivate cognitive flexibility by asking questions like, “What’s the evidence for and against this idea?” “Is it possible that another perspective is more accurate?”

The second approach is to problem solve. If your beliefs are rooted in reality, fix the problem or make it more manageable, such as outlining the steps to complete a project that feels overwhelming. The third is to accept what you can’t change. You can then move forward and engage in activities that matter, without allowing your thoughts to control you.

Many people pursue therapy because their relationships are suffering. A course of CBT can lead to marked benefits not only for the person in therapy but for those close to him or her. One is less anxiety in the relationship; chronic worry in generalized anxiety disorder frequently leads to tension and irritability, causing conflict between partners. Another is greater presence, because a CBT framework can help translate one's intention to be present into a plan of action to make it happen. Positive mood, better sleep, happier children, and healthier thought patterns, are also ways in which CBT can improve a relationship .

CBT originally evolved to treat depression, but research now shows that it can address a wide array of conditions, such as anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance use disorder, and phobias. Versions have also been created to treat insomnia and eating disorders. But beyond treating clinical challenges, CBT can also provide the skills people need to improve their relationships, happiness , and overall fulfillment in life.

Yes, many studies have documented the benefits of CBT for treating depression. Research shows that CBT is often equally as effective as antidepressants ; patients who receive CBT may also be less likely to relapse after treatment than those who receive medication . CBT can provide patients with the inner resources they need to heal—and to prevent a depressive episode from recurring in the future.

CBT is an effective and lasting treatment for anxiety disorders, research shows. CBT provides the tools to alter the thoughts and behaviors that exacerbate anxiety. For example, someone with social anxiety might think, “I feel so awkward at parties. Everyone must think I’m a loser.” This thought may lead to feelings of sadness, shame , and fear, when then lead to behaviors like isolation and avoidance. CBT can help people learn to identify and challenge distorted thoughts, and then replace them with realistic thoughts, changing the cycle of anxiety.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia, or CBT-I, is a short-term treatment for chronic insomnia. The therapy aims to reframe people’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors around sleep. People with insomnia often enter a cycle of trying to make up the sleep they lost, sleeping poorly the subsequent night, and then becoming anxious about sleeping. These behaviors can include going to bed too early, taking naps, or relying on alcohol to fall asleep. The role of CBT-i is to change those patterns, through techniques such as challenging anxious thoughts and adhering to a set sleep schedule.

Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, or CBT-E, is a form of CBT designed to treat eating disorders including anorexia, bulimia, and binge- eating disorder . CBT-E focuses on exploring the reasons the patient fears gaining weight with the goal of allowing the patient to decide for themselves to make a change. CBT-E stands in contrast to Family-Based Therapy, a leading treatment in which the patient’s family takes on an important role in addressing the disorder and the person’s eating patterns at home.

CBT was founded by psychiatrist Aaron Beck in the 1960s, following his disillusionment with Freudian psychoanalysis and a desire to explore more empirical forms of therapy. CBT also has roots in Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy (REBT), the brainchild of psychologist Albert Ellis. The two were pioneers in changing the therapeutic landscape to offer patients a new treatment option—one that is short-term, goal-oriented, and scientifically validated.

The creator of cognitive behavioral therapy is Aaron Beck, a psychiatrist at the University of Pennsylvania. In the 1960s, Beck was practicing psychoanalysis. But he came to realize that the approach was failing to treat his depressed patients—entrenched negative thoughts prevented them from overcoming the disorder. So he developed cognitive behavior therapy, rooted in the philosophy of Albert Ellis’s rational emotive behavior therapy, to change these harmful patterns of “emotional reasoning” and spark genuine change.

In the 1950s, the psychologist Albert Ellis became discouraged by psychoanalysis. When treating his patients, he discovered that becoming aware of one’s beliefs and challenges didn’t necessarily change them. Ellis developed what is now called "rational emotive behavior therapy" (REBT). The groundbreaking therapy is based on his core philosophy: that most of our behavioral and emotional problems—from getting over a breakup to handling child abuse—stem from our own irrational beliefs about our situations and how we should be treated. By changing those beliefs, we can change our emotions and behaviors for the better.

Rational emotive behavior therapy later sparked the creation of cognitive behavior therapy. Both encompass the notion that emotions and behavior are predominantly generated by ideas, beliefs, attitudes, and thinking, so changing one’s thinking can lead to emotion and behavior change. Yet there are also a few differences between REBT and CBT. Unlike CBT, REBT explores the philosophic roots of emotional disturbances, encourages unconditional self-acceptance, and distinguishes between self-destructive negative emotions and appropriate negative emotions.

Psychoanalytic and psychodynamic therapy, as well as many other approaches, center around exploring the past to gather understanding and insight. CBT is distinct because it focuses on the present. What are you thinking right now? What were you thinking when you began to feel anxious? Are there any harmful patterns that emerge? The goal is to understand what happens in your mind and body in the present to change how you respond.

Marriage and family therapists can empower young females to navigate body image concerns, despite the unique challenges posed by social media.

Like your morning coffee or yoga practice, making an effort to be more mindful and aware of your thoughts throughout the day can be a powerful way to treat your mind better.

What sounds like super-hearing, but definitely isn’t?

Research suggests that while introversion is a personality trait, social anxiety is a phobia. Not all people who are socially anxious are introverted.

Habits of thought and behavior can cement pessimism into our personality, but anyone can learn new habits of thought to help them access joy.

Depression requires more than just medication. A comprehensive approach, including therapy and supportive relationships, can help manage this complex condition effectively.

It can be tempting to avoid tough conversations, but is there a cost?

Perfectionism, fueled by societal pressures, can harm mental health. Understanding its causes and effects enables individuals to embrace imperfection and lead a more balanced life.

It's normal to learn coping skills and then totally forget about them during stressful times. Making a "distress tolerance kit" can help, especially for impulsive behaviors.

Learn to switch off of the worry channel and experience more moments of peace.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

“One thing is sure. We have to do something. We have to do the best we know how at the moment… If it doesn’t turn out right, we can modify it as we go along.” – Franklin D.Roosevelt

P roblems in life can take on a variety of forms, but many of them share common characteristics that serve as cues, alerting us to the presence of a bonafide problem. The attitude that we choose to take toward the problem can serve as a powerful determinant of our ability to reduce distress and use emotional information in helpful ways. Many of the problems or chaos that we invite , create, or have thrust upon us become less intimidating and paralyzing when we take a proactive stance toward solving them. A mindfully open and alert stance can serve as a stable foundation as you begin the process of confronting the problem and moving toward a solution.

Part of the wisdom inherent in effective problem solving is discerning between solvable and unsolvable problems … and being willing to radically accept and let go of those problems which are truly out of your control. For all of the problems that you have the power to solve, remember that quite often a puzzling or painful problem is actually just a very difficult decision that is waiting to be made. It is possible that the looming “problem” in your life has taken on its imposing or frightening form due to a conscious or unconscious un willingness on your part to make a tough decision.

Brief Mindfulness Exercise:

Before you begin the following five steps of problem solving from your base of mindfulness, allow yourself a few moments to slow down and take a some slow deep breaths. Bring your full awareness to this moment. Allow your thoughts, emotions, and sensations to naturally emerge; notice them just as they are, accept their presence, and release them with each breath that leaves your lungs. If confusing or unsettling thoughts enter into awareness, observe them with an open heart and nonjudgmental mind. Allow yourself to become disentangled from those thoughts as you notice that they are just thoughts … not “facts” or absolute truth.

Notice your emotions as they arise naturally from within. Perhaps you sense a deep-seated fear as you approach this problem. Observe this experience and direct compassion toward your fear, anxiety , or doubt. Embrace your suffering , rather than push it away. Notice what useful information is embedded within those painful disavowed experiences. Observe any physical sensations that emerge at this time, reconnecting with your body . Direct your full awareness in a nonjudgmental, accepting, and curious way toward those sensations. Perhaps there is a tightness in your throat or chest, shaking in your hands, a racing heart, or queasiness at your core.

Be kind toward yourself and notice the delicate way that your thoughts, emotions, and sensations are all coming together in a nuanced dance as you approach solving this problem. Allow wise mind to guide you, bringing together reason with emotion, as you begin to become open, reflective, and alert to the problem. When you are ready, direct your mindful awareness and focus completely to the problem you are facing. Remember that part of being mindful involves directing your full presence toward one thing at a time , so give yourself the gift of slowing down as you go through this five step process of problem solving.

Mindful Problem Solving

R ead through the following five steps of problem solving and write down your authentic responses at each step along the way. Let go of the notion of “right” or “wrong” responses and trust yourself . As you go through these steps, make a commitment to yourself to follow through with your plan. When you take the time to move through solving a difficult problem with an open heart and awakened mind, you may begin to see that the right path out of the woods was there all along… just waiting for you to notice it and summon the courage to make the journey.

(1) State your problem

Problems cannot be solved and decisions cannot be made effectively before you have clearly and accurately identified the problem. If this step is easy for you, simply write down in simple and concise terms exactly what problem you are facing. If it seems challenging to identify the problem, try writing down some characteristics of the problem or common themes. For example, “health issues: illness, sleep, diet, mental health” or “relationship issues: conflict, loneliness, dissatisfaction.”

Once you have clearly identified and stated your current problem, take the time to engage in a bit of “ problem analysis ” to help you understand the various dimensions of the problem with greater clarity:

- What is the problem?

- Who is involved?

- What happens? What bothers you?

- Where does the problem occur?

- When does it occur?

- How does it happen? (Is there a pattern ?)

- Why do you think it happens?

- What else is important in this situation?

- How do you respond to the situation? (List your behaviors .)

- How does it make you feel?

- What outcome do you want to see?

(2) Outline your solutions

Once you have sufficiently identified the problem from various perspectives, you are ready to start identifying the best solutions available. Maintain a mindfully open attitude as you approach potential solutions from a place of creativity. Even if your “ideal” solution may not be realistic at this present moment, stay open to making the most out of the tools you do have to work with at this point in time. Notice if any potential solutions come to you as you reflect on your responses to the last three questions from step one, regarding what you do , what you feel , and what you truly want .

Try coming up with and writing down three possible solutions based on those responses. For example, possible solutions may be worded in some of the following ways: “Figure out better ways to respond when I feel confused or frozen by the problem,” or “Learn how to manage intense emotions more effectively when the problem occurs,” or “Deliver painful news or express authentic feelings , no matter how scary it may feel.”

As you begin to set goals that will move you closer to your desired solution , remember to describe what you do want to happen, as opposed to what you don’t want to happen. For example, instead of “I don’t want to feel sad and confused,” rephrase that as, “I do want to feel happiness and a sense of clarity.” It is easier to move toward desired goals when they are stated in positive terms. If your goals feel general or vague (e.g., “I want to feel happier”), simply notice this for now – you will develop specific strategies intended to help you realize your goals in the next step.

Remember to state your intended goal from your own point of view, taking responsibility and ownership… this is what you want to do. For example, instead of “I don’t want my friend to get angry with me so easily,” rephrase it as, “I want to learn how to develop a better relationship with my friend.” When goals are stated in these terms, you can become empowered by realizing the amount of control you have in reaching your goal, instead of depending on or wondering about the thoughts or behaviors of others.

(3) List your strategies

Maintain the creative mindful attitude that you took while generating possible solutions, as you allow your heart and mind to fully open to the process of recognizing strategies that will move you closer toward your goals. As you begin the process of coming up with ideas that may or may not help you reach your goal(s), remember: (1) don’t criticize/judge your ideas, (2) allow yourself to generate lots of ideas/possibilities, (3) think creatively – allow yourself to be free of censorship, and (4) integrate and improve on ideas if needed – perhaps a few of your strategies have the potential to integrate into one amazing idea.

As you begin to create a brainstorm list of potential strategies, reflect back on your three possible solutions from the previous step. This exercise in brainstorming possible strategies involves the following steps:

- Write down the clearly stated/defined problem

- List your three possible solutions

- Underneath each solution, write at least 10 possible strategies

Part of engaging in this process of brainstorming from a centered place of mindfulness involves giving yourself permission to take your time, slow down your mind , and allow creative and productive strategies to emerge naturally into conscious awareness. Creative, effective, and mindful problem solving allows for strategies/ideas to be borne out of your authentic self … from your innermost sense of values , intuition, and alert wisdom.

(4) View the consequences of your strategies

At this step in the problem solving process, you have clearly stated the problem, come up with three possible solutions (think of them as solutions A, B, & C), and at least 10 possible strategies for each. Now that you are equipped with at least 30 problem-solving strategies, you are prepared to narrow down that list as you evaluate the potential (realistic) consequences of putting them into action.

- Look at the three lists of strategies you created for solutions A, B, and C. Notice which solution has generated the most strategies that appear to have the greatest chances of actually succeeding.

- After you mindfully evaluate which of the three lists contains strategies that seem most effective (likely to bring about the desired outcome), choose the solution that you believe has the greatest chance of bringing success.

- Using the solution you chose (A, B, or C), begin to narrow down the strategies to three. These three strategies should be the best strategies for that particular solution; bear in mind you can always combine a few strategies into an even more powerful one. During the process of narrowing down your list, cross out any ideas that strike you as exceedingly unrealistic or not aligned with your true values or authentic self.

- In order to evaluate the consequences of each strategy, reflect on how each may positively and negative impact yourself, others, and your short-term/long-term goals.

- Write down each of your three narrowed down strategies in specific terms and list the positive and negative consequences in two columns underneath each strategy.

- If the best strategy does not become readily apparent to you at this point, try rating the positive and negative consequences for each of the three strategies on a scale of 1 to 4 (1 = not too important or significant, 4 = very important or significant).

- You can now go through all three strategies and add up those scores. The idea is that the most effective strategy is the one with the highest positive/lowest negative consequence score.

- If you feel at peace and content with the strategy that yielded the greatest positive consequences for yourself/others and your short-term/long-term goals, carry this knowledge and confidence with you to the final step of this problem-solving process.

(5) Evaluate your results

Now that you have selected the best strategy as a result of your deliberate, focused, and mindful process of problem solving, the time has come to put that strategy into action . It is time to take your carefully selected strategy and break it down into simple, specific, realistic steps that you will commit to enacting. Remember to insert different/specific words into the following example that allow you to connect this final step to the personal problem you are currently facing. A specific example of breaking down your chosen strategy into concrete steps can be found at step five of the following example.

General example of final outcome – “Five steps of effective and mindful problem solving” :

(1) Problem : “I’m at a major crossroads in my life and don’t know what to do.”

(2) Best solution – based on which of the three primary solutions generated the most effective list of strategies: “Figure out better ways to respond when I feel confused or frozen by the problem.”

(3) Best strategy – based on greatest/realistic chances of success and mindful weighing of potential consequences: “Practice mindfulness meditation , emotion regulation exercises , & interpersonal assertiveness .”

(4) Awareness of consequences – accurate recognition of short-term/long-term consequences to yourself/others based on enacting the best strategy: “ Positive : feel more centered/relaxed/in touch with my authentic experience, increased ability to effectively identify/respond to emotions in myself and others, & increased confidence in ability to take a stand and speak my true feelings with healthy assertiveness ; Negative : fears of becoming lost within the process of meditation, temporary discomfort with allowing and responding to uncomfortable emotions authentically, & potential that expressing authentic thoughts/feelings may cause short-term/long-term hurt to others.”

(5) Evaluate & break down strategy into manageable steps – consider desired actions based on chosen strategy and commit to specific steps you will take toward putting that strategy into action: “Read about simple mindfulness exercise s and set aside 20 minutes each morning/evening to practice, write out specific emotion regulation coping skills onto flashcards and practice using them when feeling calm/centered as well as during times of emotional distress, & learn about interpersonal effectiveness and assertiveness skills – actively practice clearly stating thoughts, feelings, and needs on a daily basis.”

P roblem solving becomes significantly easier and less intimidating when you take a proactive approach toward solving the problem and become mindfully attuned with your authentic inner experience (focusing less on what others may think, want, or do as you determine what you are feeling). Give yourself the opportunity go through this type of deliberate, thoughtful, and wise process of reaching healthy resolutions to your problems.

Remember that even when taking a mindful approach, problems aren’t always solved in the first, second, or even third attempts. This is because there are so many unknowns inherent within life’s mysteries and the only person’s behaviors you can ultimately control are your own. If your initial attempts at problem solving go awry, choose to reframe that perceived failure as a learning opportunity and a valuable chance to do things differently next time. The sooner you start taking active steps toward solving problems and recognize what works and what doesn’t work… the sooner you can shed the heavy robes of indecision and emotional paralysis and begin to live your most authentic life.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Wood, J.C. (2010). The cognitive behavioral therapy workbook for personality disorders. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Featured image: For What It’s Worth by Adam Swank / CC BY-SA 2.0

About Laura K. Schenck, Ph.D., LPC

I am a Licensed Professional Counselor (LPC) with a Ph.D. in Counseling Psychology from the University of Northern Colorado. Some of my academic interests include: Dialectical Behavior Therapy, mindfulness, stress reduction, work/life balance, mood disorders, identity development, supervision & training, and self-care.

Extremely helpful, Laura. Thank you so much.

I would so enjoy seeing more about problem-solving and decision-making.

What's On Your Mind? Cancel reply

Website Links

The links below have been carefully selected and include a vast array of free resources that you can use to support your clinical practice. Click the title for more information about each site.

A Hopeful Space

A Hopeful Space is an excellent free resource for psychological practitioners. It contains information, worksheets, and videos about a range of topics, for example, grounding techniques, suicide awareness, anxiety to name a few. You can explore the comprehensive collection of free information and courses offered in the library.

https://ahopefulspace.com/

CBT for Children

Brought to you by SDS Seminars

This innovative and comprehensive modular Certificate provides participants with skills to use the core principles of CBT with Children and Adolescents. It was designed exclusively for SDS Seminars Ltd by Dr Andrew Beck, Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Honorary Senior Lecturer at the University of Manchester, Senior Lecturer on the Children and Young People’s Talking Therapies programme, a member of the BABCP Scientific Committee, a Past President of BABCP in cooperation with Paul Grantham, Consultant Clinical Psychologist, SDS Founder.

BPS Approved Certificate in CBT for Children and Adolescents

BPS Approved Certificate in CBT For Working With Adolescents

CEDAR Resources

The University of Exeter’s Clinical Education Development and Research (CEDAR) applied psychological practice centre of excellence is a world leading centre for evidence based psychological practice. They have a wide range of free resources available including translated resources, and resources specifically for children and young people.

https://cedar.exeter.ac.uk/resources/iaptinterventions/

Get Self Help Resources

Get Self Help provides CBT self-help resources including worksheets, information, videos and mp3s. You can search for materials by probelms or solutions which makes easy to navigate the site. Most materials are free and the site is easy to navigate.

https://www.getselfhelp.co.uk/

Man Confidence

Junaid Hussain is on a mission to provide an alternative way to access mental health care specifically tailored to men. Currently he is already offering a free course for suicide awareness and several other paid courses on a range of mental health topics that will be expanding soon.

https://manconfidence.co.uk/

MindEd Resources

MindEd is suitable for all adults working with, or caring for, infants, children or teenagers, adults and older people, including people with a learning disability and autistic people; all the information provided is quality assured by experts, useful, and easy to understand. We aim to give adults who care for, or work with people:

the knowledge to support their wellbeing

- the understanding to identify a child, young person or adult at risk of a mental health condition

- the confidence to act on their concern and, if needed, signpost to services that can help

MindEd is multi-professional, and can be used by teachers, health and mental health professionals, police and judiciary staff, social workers, youth service volunteers, school counsellors among others to support their professional development.

https://www.minded.org.uk/

Moya CBT Resources

Helen Moya has a long a distinguished career in mentla health and CBT. SHe has a wide range of helpful and downloadable resources and she also hosts regualr CPD sessions to compliment her resources.

https://www.moyacbt.co.uk/resources/

SDS Video Library

The PWP Training Library is a growing video on-demand training catalogue opening with 30 topics and more added to each month. Its initial content has been specifically chosen with reference to two geographically diverse PWP Regional surveys and we welcome further suggestions. Let us know what you need [email protected].

These on-demand trainings are typically between 15-45 minutes each in length and provided by experienced PWPs, PWP academics and PWP specialists. This is for a number of reasons.

SDS are now offering an annual individual subscritions to all of their videos for £100 (+VAT) or a Team PWP subscription for £950 (+VAT)

Sign up to our mailing list to recieve a 10% discount code on the price of individual videos using the code Hub10%

https://sds-seminars.online/product-category/pwp/?orderby=price

TalkPlus Resources

TalkPlus has a wide range of fantastic free to use resources, information packs, videos and worksheets.

https://www.talkplus.org.uk/resources

We Heart CBT Resources

WeHeartCBT is a collection of resources aimed at helping children and young people who are struggling with symptoms of anxiety and/or low mood. Resources are based on a Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) approach and are for mental health professionals, schools and parents/families.

https://weheartcbt.com/practitioner-resources

Due to copyright laws, we are not able to host or share specific materials. We simply provide freely available links that are located in one handy space in an attempt to make our psychological professionals lives a little easier!

Low Intensity CBT Information

Low Intensity Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (LICBT) is a form of self-guided help for those experiencing mild to moderate symptoms of depression and or anxiety, and is usually supported by a Psychological Practitioner. LICBT is often offered as the first step in the NHS Talking Therapies approach and is usually 6-8, 30 minute sessions, which are delivered weekly or fortnightly. Sessions usually focus on one or two key techniques due to the limited time of the treatment. LICBT uses a 'here and now' approach to support individuals to identify and address throughts and behaviours that are maintaing their problems.

What are some of the benefits of low intensity CBT across different settings?

The difference between High intensity and low intensity CBT

NHS Talking Therapies Manual

The NHS Talking Therapies (formerly known as Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT)) manual and its resources have been produced to help the NHS Talking Therapies programme improve the delivery of, and access to, evidence-based psychological therapies within the NHS.

Anyone interested in a career as a psychological practitioner should make themselves aware of the manual:

NHS Talking Therapies Manual Link

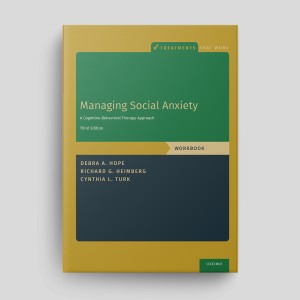

Helpful Books, Resources & Links

Here you will find links to some helpful resources. Lots of people are selling some of the books on the Facebook Groups at a discounted rate.

Low-Intensity Cognitive Behaviour Therapy; A Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner (PWP) Handbook

A Pragmatic Guide to Low Intensity Psychological Therapy: Care in High Volume

Oxford Guide to Low Intensity CBT Interventions

A Clinician’s Guide to

Low Intensity Psychological

Interventions (LIPIs) for

Anxiety and Depression

Low Intensity Cognitive Behaviour Therapy: A Practitioner's Guide

Low-intensity CBT Skills and Interventions

a practitioner's manual

Reach Out Guide

Test Your Mental Health Assessment Skills

Triage a Virtual Patient

You are an NHS Talking Therapies practitioner. You are about to meet Matthew Walker for a triage assessment following a referral from his GP. The referral states that Mr Walker has declined medication and that he would rather seek therapeutic support.

The purpose of this exercise is to ensure that you are able to assess the patient and to be able to gather enough information in order to provide a probable diagnosis. The patient has brought their PHQ9 and GAD7 questionnaires with them; you must structure the session to enable meaningful integration of these. Key skills here are around 1) the assessment of his suitability for IAPT, 2) exploration of symptoms and the impact for a patient, 3) moving towards a shared plan of care.

Assess a Virtual Patient

You are an NHS Talking Therapies practitioner. You are about to meet Matthew Walker for an appointment following a brief triage assessment you completed with him last week. From his triage assessment, he presented with low mood following a fall, intermittent mild weakness and numbness, pain and tingling on his right side. A neurologist has confirmed he has a functional neurological disorder, as expected all the tests were normal and he doesn’t need any more investigations. His GP is confident that his symptoms are functional.

The purpose of this exercise is to ensure that you are capable of providing information to the patient that moves them towards therapeutic action. The patient has brought their PHQ9 and GAD7 questionnaires with them; you must structure the session to enable meaningful integration of these. You should start to be able to develop a shared management plan with the patient including the creation of a collaborative five areas formulation. Key skills here are around 1) the interplay between physiological and psychological health 2) symptom explanation for a functional illness, 3) exploration of symptom impact for patient 4) moving towards a shared plan of care.

Interventions & Resources

Acceptance & Commitment

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a psychotherapeutic approach that helps individuals better cope with emotional and psychological issues. ACT is based on several core principles, including accepting one's thoughts and feelings without judgment, practicing mindfulness, clarifying personal values, and taking committed action based on those values. ACT has been used to address a wide range of psychological and emotional issues, including anxiety, depression, stress, addiction, chronic pain, and more. It aims to promote psychological flexibility, allowing individuals to adapt and respond to life's challenges with greater resilience and a deeper sense of purpose.

Act Mindfully Website Free Resources

Acceptance & Commitment Therapy for Anxiety & Depression Video

Activity & Exercise

Increasing activity and exercise with Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is a therapeutic approach that combines principles of CBT with strategies to promote physical activity and exercise. This approach is particularly useful for individuals dealing with mental health conditions like depression or anxiety, where physical inactivity can exacerbate symptoms. The combination of CBT and exercise helps individuals break the cycle of inactivity and negative thought patterns that can contribute to mental health issues like depression and anxiety. By setting achievable goals and addressing cognitive barriers, clients are more likely to maintain regular exercise routines, which, in turn, can have a positive impact on their mental well-being. This approach not only improves physical health but also fosters a more positive and adaptive mindset.

PDF & Links:

TalkPlus: Physical Activity and our Mental Health

CEDAR: Get Active, Feel Good! Helping yourself to get on top of low mood

Webinar: Improving Your Mental Wellbeing by Increasing Physical Activity

Benefits of Physical Activity on Mental Health 2019

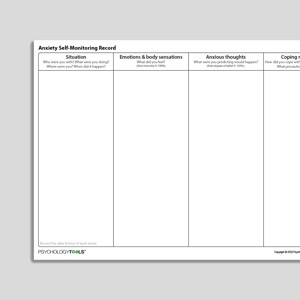

Anxiety: Fight or Flight

The "fight or flight" response, also known as the "acute stress response," is a physiological reaction that occurs in response to a perceived threat or danger. It's an innate and automatic reaction that prepares the body to either confront the threat (fight) or escape from it (flight). The fight or flight response is an evolutionary adaptation that helped our ancestors respond quickly to physical threats. In modern times, it can still be triggered by various stressors, both physical and psychological. While this response is crucial for survival in dangerous situations, chronic or excessive activation can lead to health issues, including anxiety and related physical symptoms. Teaching client's how to manage the fight or flight symptoms can be a powerful tool to support recovery.

PDF & Links

The Physical Effects of Anxiety and How to Manage Them

Mood Juice: Anxiety

Videos:

Justin Caffrey: How to Manage Fight Flight Response. Step-by-Step Neuroscience

The Fight Flight Freeze Response

Self Help Toons: Guided Breathing & Walking Relaxation Meditation: Panic Anxiety Stress

TalkPlus: Muscle Relaxation

Anger Management

Anger is often considered a secondary emotion because it typically arises as a response to underlying primary emotions or triggers. In this context, primary emotions are the more basic and immediate feelings that can give rise to anger when they are not effectively processed or expressed. Anger, in this context, acts as a secondary response to these primary emotions, often serving as a protective mechanism. It can provide individuals with a sense of control, power, or an outlet for the distress caused by the primary emotions. Recognising and understanding the primary emotions that lead to anger can be important for managing anger in a healthier and more constructive way. By addressing the underlying emotions, individuals can develop more effective strategies for dealing with anger and its triggers.

NHS Scotland: Problems with Anger Self Help Guide

Moodjuice Anger Self Help Guide

CNTW: Controlling Anger

Get Self Help: Anger

Get Self Help: CBT Self Help for Anger

YoungMinds: Talking about Anger

The ASMR Psychologist: How to control your anger

Behavioural Activation

Behavioural activation (BA) is a time-limited, evidence-based psychotherapy for depression. Based on a behavioural model of depression, BA aims to increase behaviours that are positively reinforced by the environment and decrease behaviours that function to maintain depression. As a practitioner, BA is one of the most commonly used low intensity CBT interventions.

PDF &Links:

CEDAR: Lift your Mood

TalkPlus: Behavioural Activation

Greater Manchester NHSFT: Behavioural Activation

University of Michigan: Values Based Behavioural Activation

Behavioural Activation for PWPs by Josh Cable

Values Based Behavioural Activation for PWPs Video by Josh Cable

Talk Plus Behavioural Activation MP3

Oxford University Podcast: Introducing CBT for Low Mood and Depression: doing more of what matters to you

Adapted Resources:

Translated Materials at CEDAR

SignHealth resources for deaf people including a library of BSL supported recordings

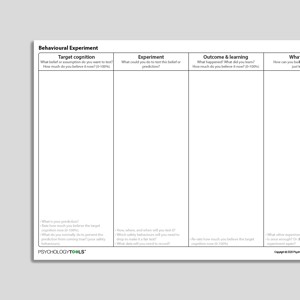

Behavioural Experiments

Behavioural experiments in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) are structured activities or tests designed to help individuals challenge and modify unhelpful beliefs or assumptions, particularly those related to anxiety, depression, and other emotional or psychological difficulties. Behavioural experiments are a practical and hands-on component of CBT that encourages individuals to challenge and reframe their negative beliefs. They provide concrete evidence to support cognitive restructuring and help individuals develop a more adaptive and balanced way of thinking. These experiments are tailored to each individual's specific challenges and are an essential tool in the process of change and personal growth.

CEDAR: Unhelpful Thoughts: challenging and testing them out

CEDAR: Behavioural Experiments

Carepatron Behavioural Experiment Worksheet

Changing Negative Beliefs with Behavioural Experiments in CBT: Self Help Toons

How To Use CBT Behavioural Experiments: Lewis Psychology

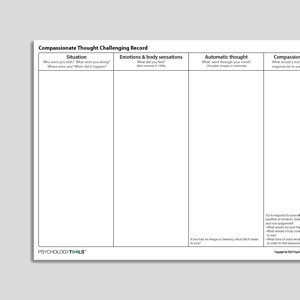

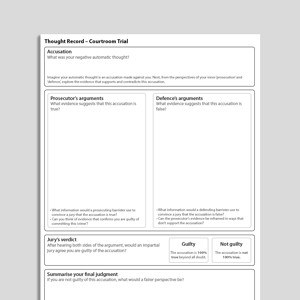

Cognitive Restructuring

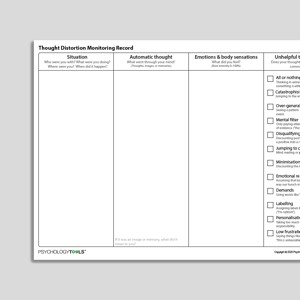

A major component of any emotional state is the thinking that accompanies the physical and behavioural symptoms. Most thoughts are automatic and many of these are ‘unhelpful’. Key features are that these thoughts are automatic, seem believable and real at the time they appear, and are the kind of thoughts that would upset anybody. These thoughts act powerfully to maintain mood states. Cognitive restructuring is a way of changing unhelpful thoughts by identifying, examining and challenging them.

PDF & Links:

CEDAR: Unhelpful Thoughts: Challenging them and Testing Them Out

TalkPlus: Cognitive Restructuring

Get Self Help: Thought Challenging

Cognitive Restructuring for PWPs by Josh Cable

CBT and Reframing Thoughts with Cognitive Restructuring

CBT for Anxiety & Cognitive Restructuring

Talk Plus Cognitive Restructuring MP3

Distress Tolerance

Distress intolerance is a perceived inability to fully experience unpleasant, aversive or uncomfortable emotions, and is accompanied by a desperate need to escape the uncomfortable emotions. Difficulties tolerating distress are often linked to a fear of experiencing negative emotion. Often distress intolerance centres on high intensity emotional experiences, that is, when the emotion is ‘hot’, strong and powerful (e.g., intense despair after an argument with a loved one, or intense fear whilst giving a speech). Overall, distress tolerance skills in CBT are valuable for individuals who struggle with intense emotional reactions or impulsive behaviours when faced with distressing circumstances. They empower individuals to navigate crises and difficult emotions more effectively, ultimately leading to better emotional regulation and a higher quality of life.

Centre for Clinical Interventions: Tolerating Distress

Get Self Help: Distress Tolerance

Self Help Toons: Distress Tolerance & Crisis Survival

Dr Tracey Marks: How to Deal with Negative Emotions - Distress Tolerance

NICABM: Three Steps to Help Clients Better Tolerate Distress

Exp Resp. Prev. for OCD

Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) is a cognitive-behavioral therapy technique commonly used to treat individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and related anxiety disorders. It is based on the idea that people with these disorders experience distressing obsessions (persistent, intrusive, and distressing thoughts) and engage in compulsions (repetitive behaviors or mental acts) to reduce the anxiety and distress associated with these obsessions. The goals of ERP include helping individuals learn to tolerate the anxiety and discomfort triggered by their obsessions without resorting to compulsions. Over time, as they repeatedly face these fears without performing rituals, the anxiety typically diminishes, and they begin to recognize that their obsessions are less threatening than they initially believed.

OCD UK: Exposure and Response Prevention

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A Self Help Book

Crufad Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Patient Treatment Manual

Exposure and Response prevention (ERP) for OCD: George Maxwell

ERP Therapy for OCD | A Complete Guide: Paige Pradko

BSL - Treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)

Goal Setting in LICBT

Goal setting is an important component of low intensity CBT. Setting clear and achievable goals helps individuals identify what they want to change and provides a framework for working towards those changes. Goal setting in LICBT helps individuals focus on specific, meaningful changes they want to make in their lives, and it provides a structured approach to achieving those changes. It's a collaborative process between the practitioner and the client, and it plays a key role in the overall success of CBT treatment.

Get Self Help: Goal Setting

CEDAR: Goal Setting in Low Intensity CBT

CBT Demo Goal Setting

How to set SMART CBT goals in 2021

Beck Institute: Clinical Tip: Setting Goals

Translated Materials:

Get Self Help

Graded Exposure

Exposure therapy is a psychological treatment technique used to help individuals confront and overcome various anxiety disorders, phobias, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The central premise of exposure therapy is to systematically expose the individual to the source of their fear or anxiety in a controlled and gradual manner. Exposure therapy is evidence-based and has been shown to be highly effective in treating various anxiety disorders, phobias, and trauma-related conditions. It helps individuals confront and gradually overcome their fears, leading to a reduction in anxiety and an improved quality of life. This therapy is often conducted under the guidance of a trained therapist who ensures the safety and effectiveness of the exposure process.

CEDAR: Facing your Fears

TalkPlus: Graded Exposure

Get Self: Graded Exposure

Flinders University: Graded Exposure

Graded Exposure: Dr Paul Stone

Graded Exposure for PWPs

Face your Fear & Reduce Anxiety: Self Help Toons

TalkPlus Graded Exposure MP3

https://cedar.exeter.ac.uk/resources/nhstalkingtherapiestranslated/

Pacing (Boom & Bust)

Pacing in CBT refers to the practice of setting and maintaining a consistent and sustainable level of activity and effort. It involves breaking down tasks and activities into manageable portions, avoiding overexertion or rushing, and finding a comfortable, steady rhythm. Pacing is especially relevant for individuals dealing with mental health conditions like anxiety, depression, or chronic pain, as it helps prevent burnout and exhaustion by distributing energy and focus more evenly over time.

The boom-and-bust cycle is a pattern where individuals alternate between periods of high activity (the "boom") and periods of low activity or inactivity (the "bust"). This cycle can be counterproductive and often leads to stress, anxiety, and decreased overall productivity. In CBT, therapists work with individuals to recognize and modify this pattern by encouraging more consistent and balanced engagement in activities. The goal is to avoid extremes and find a more sustainable approach to daily life, which can improve overall well-being and mental health.

Get Self Help: Chronic Pain & Fatigue

Oxford University Hospitals: Pacing - How to Manage Your Pain and Stay Active

M.E. Association: Pacing - Activity and Energy Management

Action for M.E: Pacing for People with ME

Long Covid Physio: Pacing

Manchester NHSFT: Pacing Pain Management

Panic Management

Panic management in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a structured approach designed to help individuals who experience panic attacks or panic disorder. It involves several key components: Psychoeducation, Identification of Triggers and Symptoms, Cognitive Restructuring, Exposure, Breathing and Relaxation Techniques. Overall, panic management CBT equips individuals with the skills and strategies needed to understand, cope with, and ultimately reduce the frequency and intensity of panic attacks. It empowers individuals to regain a sense of control and improve their quality of life.

CEDAR: Panic Not: Managing Panic Disorder

Crufad: Anxiety and Panic Disorder Patient Treatment Manual

Centre for Clinical Interventions (CCI): Panic

Sheffield Hallam University: Managing Panic

Self Help Toons: Calm Your Panic Attacks with CBT

CCI: Developing a Panic Formulation

Adapted Materials:

Cedar Translated Materials

Problem Solving