0800 118 2892

- +44 (0)203 151 1280

Teen Cocaine Addiction Case Study: Chloe's Story

This case study of drug addiction can affect anyone – it doesn’t discriminate on the basis of age, gender or background. At Serenity Addiction Centres, our drug detox clinic is open to everyone, and our friendly and welcoming approach is changing the way rehab clinics are helping clients recover from addiction.

We’ve asked former Serenity client, Chloe, to share her experience of drug rehab with Serenity Addiction Centre’s assistance.

Chloe’s Addiction

If you met Chloe today, you would never know about her past. This born and bred London girl is 20 years old, and a flourishing law student with a bright future in the City.

A few years ago though, it seemed as if this straight A student was about to throw away her life, thanks to a class A drug addiction .

Chloe had a great childhood. By her own admission, school was a breeze for her, with strong academic achievement and social skills making her as successful on the playground as she was in the classroom.

Age 7, Chloe started at a boarding school, and loved having friends around her all the time. With no parents about, Chloe and her friends found themselves invited to house parties. As soon as I could convince people they we 18, they moved on to London’s nightclubs.

It was here where Chloe first came across drugs, and it was a slippery slope to cocaine addiction. She explains: “At 15, I was taking poppers, graduated to MDMA at 16, and then I tried cocaine at our year 13 parties. I got separated from my friends, and found them taking cocaine in a back room. I didn’t want to be left out, so I tried it.”

Chloe scored straight As in her A levels, and accepted a place at Kings College London to study law. She was introduced to new people, and it seemed that cocaine was available at every place they went. Parties, clubs, and even her new friends were all good sources of a line of cocaine. As a self confessed wild child by this point, Chloe didn’t want to miss out.

The demands of a law degree were high, but so was Chloe’s desire for more cocaine.

Going out almost every night to snort coke, she started to wonder if she was becoming an addict. She spent every penny of the generous allowance from her parents. Chloe spent every penny available on credit cards, and even took on a £2000 bank loan to support her habit.

Chloe estimated that at one point, her addiction had saddled her with more than £13,000 of debt.

Coming out of Addiction Denial

Chloe’s light bulb moment finally came when her best friend, who she shared a flat with, sat her down and asked why they were drifting apart.

Chloe realised that cocaine had become more important to her than her friends, family, and studies. It had to stop. Chloe found the details for Serenity Addiction Centres, and called the same day to ask for help with her addiction.

One thing Chloe particularly appreciated about Serenity Addiction Centres was the flexible approach of the counsellors . They got to know Chloe, listening to her worries, and working out a non-residential rehab plan for her. This allowed her to continue with her studies.

Chloe’s treatment was organised at a clinic not far from her university, allowing her to keep her studies on track, and keeping her life as normal as possible.

Chloe says: “Talking about how I was using cocaine, along with contributing problems from earlier in my life, were a massive help. I didn’t want to be known just as a party girl”.

“If I’d not found Serenity Addiction Centres, there would probably have been a long wait for NHS treatment. Serenity Addiction Centres got the right treatment. Everything was organised with privacy and discretion. I only shared what was happening with my flatmate.”

This level of discretion was really helpful, and the rapid results of her treatment meant that after just three months Chloe felt able to tell her parents what had been happening.

Life after rehab

It’s amazing that Chloe has now had nearly a year where not taken cocaine, and faced her debts by working part time to repay what she owes. Even better, thanks to Serenity’s fast intervention. Chloe is on course for a 2:1 in her law degree.

If you’re ready to detox? Serenity Addiction Centre’s addiction support team are here to help you find the rehab programme which works for you. Serenity can help you beat your addiction. Gaining control over drugs, allowing you to move on and take back control of your life.

This Drug Addiction Case Study is here so others may identify. Contact us today , and begin your detox journey with Serenity Addiction Centres.

FREE CONSULTATION

Get a no-obligation confidential advice from our medical experts today

Request a call back

We provide a healthy environment uniquely suited to support your growth and healing.

- Rehab Clinic - Serenity Rehabilitation LTD. Arquen House,4-6 Spicer Street, St Albans, Hertfordshire AL3 4PQ

- 0800 118 2892 +44(0)203 151 1280

- Testimonials

- Case Studies

Popular Pages

- Alcohol Addiction

- How To Home Detox From Alcohol

- Alcohol Rehab Centres

- Methadone addiction

Top Locations

- Leicestershire

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland, Starting Immediately

Due to the downward trend in respiratory viruses in Maryland, masking is no longer required but remains strongly recommended in Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. Read more .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

News & Publications

New research and insights into substance use disorder.

Addictions to alcohol, illicit drugs and other substances remain a serious threat: According to the National Center for Health Statistics, part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, from April 2020 to April 2021, nearly 92,000 people in the U.S. fatally overdosed on drugs — the single highest reported death toll during a 12-month period. The National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics has deemed the situation “a public health emergency.” All groups ages 15 and older experienced a rise in these grim statistics, intensified by the use of fentanyl.

Currently, substance use disorder affects more than 20 million Americans ages 12 and over. These numbers are troubling, says Johns Hopkins neuroscientist and addiction researcher Andrew Huhn , “but with a multifaceted approach, people with substance use disorders can recover.”

Drawing from his background in neuroscience and behavioral pharmacology, Huhn identifies risk factors for relapse and medication strategies — bolstered by supervised withdrawal and counseling — to improve treatment outcomes. “My research focuses on understanding the human experience of substance use disorder,” he says, noting that medications for opioid overdose, withdrawal and addiction “are safe, effective and continue to save lives.”

Now, thanks to a recent collaboration with Ashley Addiction Treatment, a residential treatment center in Havre de Grace, Maryland, Huhn, Kelly Dunn and colleagues are combining efforts to identify patients likely to benefit from supervised withdrawal or opioid maintenance therapy. The goal is to expand treatment options to improve health care for people with the condition. “Relapse remains common, but a subset of patients have done well,” says Dunn.

Concurrently, Huhn, Dunn and colleagues are building a research database based on the Trac9 program, which charts patients’ progress in real-time through technology, such as a tablet or phone — as well as alerting clinicians to a relapse and the need for intervention. They are also using wearable devices to monitor sleep and cardiovascular outcomes, and a smart phone application to track each time a patient notes having successfully ignored a craving for alcohol or a drug. Much of this research takes place at Behavioral Pharmacology Research Unit , located on the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center campus.

Their published work includes studies showing a greater need for treatment of older adults with alcohol and opioid use disorders. Two additional studies have garnered national attention, both on how fentanyl use affects the treatment of opioid use disorder . Much of the illicit opioid supply in the U.S. is mixed with fentanyl, leading to a recent surge in fentanyl-related overdose deaths.

Yet another study showed promise in the use of a sleep medication to improve opioid withdrawal outcomes. Researchers in Huhn’s lab continue to glean insights from neuroimaging, ambulatory monitoring in real time, and repeated measures of behaviors.

Greg Hobelmann , the CEO of Ashley, who trained at Johns Hopkins and is a part-time faculty member, chairs an elective at the Ashley facility in addictions psychiatry. He, along with Eric Strain and Huhn are building infrastructure that includes intake data on every patient, as well as outcomes data when people complete the Ashley program — and for the year that follows. Biospecimens will also be included in the project, for studies in areas such as genetics.

“The biggest and most exciting thing is being able to create predictive models of relapse risk and then create strategies to improve those outcomes,” says Huhn. Jimmy Potash , director of the Johns Hopkins Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences couldn’t agree more. “This will be a powerful platform for discovery of better approaches to treating addiction,” he says. “I’m eager to see it — and our relationship with Ashley Addiction — move forward.”

Despite enduring challenges in addictions psychiatry, Huhn is hopeful. “We have the ability to continue collecting data and to test hypotheses,” he says. “It’s the kind of stuff we hope will turn into a game-changer, similar to what has happened in cancer and heart disease treatments. We build research into the treatment and let that guide our approach to care.”

Learn about a web-based education intervention to reduce opioid overdose, Low-Cost Intervention Reduces Risk of Opioid Overdose.

Related Reading

Johns hopkins bayview’s center for addiction and pregnancy supports new mothers and their babies in the fight against substance use disorders.

Center offers judgment-free care, helping moms and newborns

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Challenges to Studying Illicit Drug Users

Affiliations.

- 1 Alpha Nu , Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Center for the Study of Drugs, Alcohol, Smoking and Health, University of Michigan, T32 (NR016914) Complexity: Innovations for Promoting Health and Safety, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

- 2 Alpha Nu , Director of Office of Nursing Research and Evaluation an The Richard and Marianne Kreider Endowed Professor in Nursing for Vulnerable Populations, M. Louise Fitzpatrick College of Nursing, Villanova University, Villanova, PA, USA.

- 3 Alpha Nu , Professor, M. Louise Fitzpatrick College of Nursing, Villanova University, Villanova, PA, USA.

- PMID: 31106524

- PMCID: PMC6671678

- DOI: 10.1111/jnu.12486

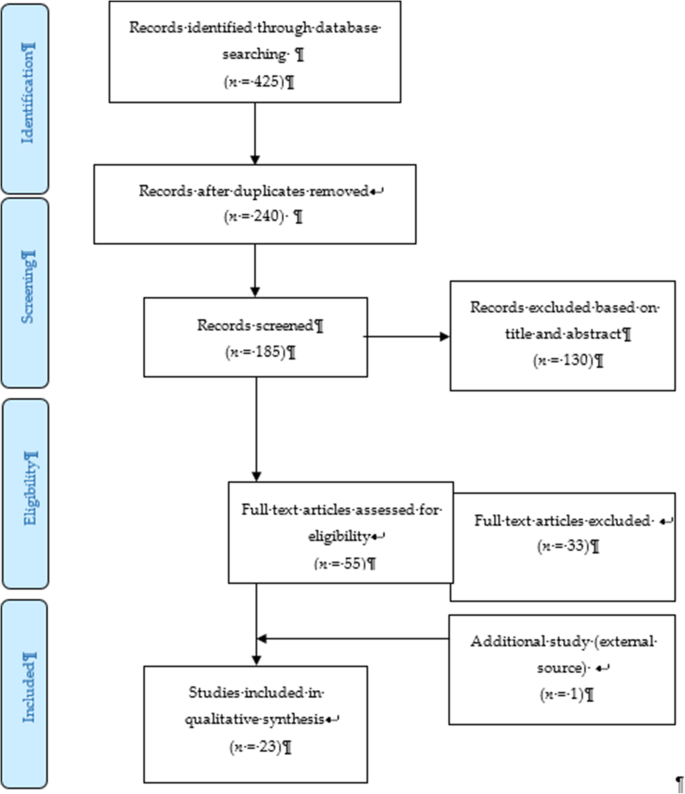

Purpose: Throughout the world, illicit drug use continues to pose a significant risk to public health. The opioid crisis in North America, the diversion of the prescription drug tramadol throughout Africa, and the increasing supply of methamphetamines in East and South Asia all contribute to increasing risks to individual and societal health. Furthermore, the violation of human rights in efforts to enforce prohibitionist values poses significant threats to many individuals worldwide. With these evolving situations, it is imperative that researchers direct their attention to the various populations of illicit drug users. However, the inclusion of illicit drug users, often considered a vulnerable population, as participants in research studies presents several increased risks that must be addressed in study protocols. Researchers are required to provide "additional safeguards" to all study protocols involving illicit drug users, but there is often substantial variability and inconsistency in how these safeguards are applied. Additional safeguards can be timely, costly, and unduly burdensome for researchers, ethical review boards, and research participants.

Approach: Through synthesis of the current literature, this article addresses the barriers to studying illicit drug users and the methods researchers can utilize to minimize risk. A case study is provided to illustrate the high level of scrutiny of study protocols involving the participation of illicit drug users and the effect of such scrutiny on recruitment of participants. The article concludes with a discussion of the effects of the current political climate on the recruitment of illicit drug users in research.

Conclusions: Individuals who participate in criminal or illegal behaviors such as illicit drug use, prostitution, illegal entry into a country, and human trafficking are susceptible to multiple physical, mental, and social health risks, as well as criminal prosecution. The importance of research on the health of marginalized populations cannot be overstated. This work must continue, and at the same time, we must continue to protect these individuals to the best of our ability through diligent attention to sound research methods.

Clinical relevance: The use of illicit drugs continues to pose a substantial threat to global health. Individuals who use illicit drugs are susceptible to multiple physical, mental, and social health risks, as well as criminal prosecution. It is imperative that researchers study these vulnerable populations in order to develop interventions to minimize individual and societal harm. There are several barriers to the study of illicit drug users that must be addressed through rigorous methodology and the addition of safeguards.

Keywords: Illicit drug use; research ethics; research methodology; vulnerable populations.

© 2019 Sigma Theta Tau International.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Tuberculosis. Bloom BR, Atun R, Cohen T, Dye C, Fraser H, Gomez GB, Knight G, Murray M, Nardell E, Rubin E, Salomon J, Vassall A, Volchenkov G, White R, Wilson D, Yadav P. Bloom BR, et al. In: Holmes KK, Bertozzi S, Bloom BR, Jha P, editors. Major Infectious Diseases. 3rd edition. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2017 Nov 3. Chapter 11. In: Holmes KK, Bertozzi S, Bloom BR, Jha P, editors. Major Infectious Diseases. 3rd edition. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2017 Nov 3. Chapter 11. PMID: 30212088 Free Books & Documents. Review.

- Estimation of the Social Costs of Illegal Drug Use in Poland Using Standardized Methodology. Mielecka-Kubie ZJ. Mielecka-Kubie ZJ. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2020 Sep 1;23(3):139-149. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2020. PMID: 33411676

- American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: oversight of clinical research. American Society of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jun 15;21(12):2377-86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.026. Epub 2003 Apr 29. J Clin Oncol. 2003. PMID: 12721281

- Illicit drug use while admitted to hospital: Patient and health care provider perspectives. Strike C, Robinson S, Guta A, Tan DH, O'Leary B, Cooper C, Upshur R, Chan Carusone S. Strike C, et al. PLoS One. 2020 Mar 5;15(3):e0229713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229713. eCollection 2020. PLoS One. 2020. PMID: 32134973 Free PMC article.

- Realising the technological promise of smartphones in addiction research and treatment: An ethical review. Capon H, Hall W, Fry C, Carter A. Capon H, et al. Int J Drug Policy. 2016 Oct;36:47-57. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.05.013. Epub 2016 Jun 1. Int J Drug Policy. 2016. PMID: 27455467 Review.

- Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among untreated illicit substance users: a population-based study. Shiraly R, Jazayeri SA, Seifaei A, Jeihooni AK, Griffiths MD. Shiraly R, et al. Harm Reduct J. 2024 May 16;21(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s12954-024-01015-9. Harm Reduct J. 2024. PMID: 38755587 Free PMC article.

- Promoting research engagement among women with addiction: Impact of recovery peer support in a pilot randomized mixed-methods study. Zgierska AE, Hilliard F, Deegan S, Turnquist A, Goldstein E. Zgierska AE, et al. Contemp Clin Trials. 2023 Jul;130:107235. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2023.107235. Epub 2023 May 19. Contemp Clin Trials. 2023. PMID: 37211273 Free PMC article. Clinical Trial.

- A mixed-methods analysis of risk-reduction strategies adopted by syringe services program participants and non-syringe services program participants in New York City. Beharie N, Urmanche A, Harocopos A. Beharie N, et al. Harm Reduct J. 2023 Mar 25;20(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12954-023-00772-3. Harm Reduct J. 2023. PMID: 36966342 Free PMC article.

- Risk of Central Serous Chorioretinopathy in Male Androgen Abusers. Subhi Y, Windfeld-Mathiasen J, Horwitz A, Horwitz H. Subhi Y, et al. Ophthalmol Ther. 2023 Apr;12(2):1073-1080. doi: 10.1007/s40123-023-00658-4. Epub 2023 Jan 24. Ophthalmol Ther. 2023. PMID: 36692812 Free PMC article.

- Abbott L, & Grady C (2011). A systematic review of the empirical literature evaluating IRBs: What we know and what we still need to learn. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 6(1), 3 10.1525/jer.2011.6.1.3 - DOI - PMC - PubMed

- Aldridge J, & Charles V (2008). Researching the intoxicated: Informed consent implications for alcohol and drug research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 93(3), 191–196. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.001 - DOI - PubMed

- Anderson EE, & DuBois JM (2007). The need for evidence-based research ethics: A review of the substance abuse literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86(2–3), 95–105. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.011 - DOI - PubMed

- Australian Injecting and Illicit Drug Users League. (2012). The involvement of drug users organizations in Australian drugs policy; a research report from AIVL’s “Trackmarks” project. Retrieved from https://nuaa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/T4.7.2-aivl-drug-user.pdf .

- Bell K, & Salmon A (2011). What women who use drugs have to say about ethical research: Findings of an exploratory qualitative study. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 6(4), 84–98. - PubMed

- Search in MeSH

Grants and funding

- T32 NR016914/NR/NINR NIH HHS/United States

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- MLibrary (Deep Blue)

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- PubMed Central

- MedlinePlus Consumer Health Information

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Open Access

- By Publication (A-Z)

- Case Reports

- Publication Ethics

- Publishing Policies

- Editorial Policies

- Submit Manuscript

- About Graphy

New to Graphy Publications? Create an account to get started today.

Registered Users

Have an account? Sign in now.

- Full-Text HTML

- Full-Text PDF

- About This Journal

- Aims & Scope

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Process

- Author Guidelines

- Special Issues

- Articles in Press

Jo-Hanna Ivers 1* and Kevin Ducray 2

In October 2012, 83 front-line Irish service providers working in the addiction treatment field received accreditation as trained practitioners in the delivery of a number of evidence-based positive reinforcement approaches that address substance use: 52 received accreditation in the Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA), 19 in the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (ACRA) and 12 in Community Reinforcement and Family Training (CRAFT). This case study presents the treatment of a 17-year-old white male engaging in high-risk substance use. He presented for treatment as part of a court order. Treatment of the substance use involved 20 treatment sessions and was conducted per Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA). This was a pilot of A-CRA a promising treatment approach adapted from the United States that had never been tried in an Irish context. A post-treatment assessment at 12-week follow-up revealed significant improvements. At both assessment and following treatment, clinician severity ratings on the Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP) and the Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) found decreased score for substance use was the most clinically relevant and suggests that he had made significant changes. Also his MAP scores for parental conflict and drug dealing suggest that he had made significant changes in the relevant domains of personal and social functioning as well as in diminished engagement in criminal behaviour. Results from this case study were quite promising and suggested that A-CRA was culturally sensitive and applicable in an Irish context.

1. Theoretical and Research Basis for Treatment

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are distinct conditions characterized by recurrent maladaptive use of psychoactive substances associated with significant distress. These disorders are highly common with lifetime rates of substance use or dependence estimated at over 30% for alcohol and over 10% for other substances [1 , 2] . Changing substance use patterns and evolving psychosocial and pharmacologic treatments modalities have necessitated the need to substantiate both the efficacy and cost effectiveness of these interventions.

Evidence for the clinical application of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for substance use disorders has grown significantly [3 - 8] . Moreover, CBT for substance use disorders has demonstrated efficacy both as a monotherapy and as part of combination treatment [7] . CBT is a time-limited, problem-focused, intervention that seeks to reduce emotional distress through the modification of maladaptive beliefs, assumptions, attitudes, and behaviours [9] . The underlying assumption of CBT is that learning processes play an imperative function in the development and maintenance of substance misuse. These same learning processes can be used to help patients modify and reduce their drug use [3] .

Drug misuse is viewed by CBT practitioners as learned behaviours acquired through experience [10] . If an individual uses alcohol or a substance to elicit (positively or negatively reinforced) desired states (e.g. euphorigenic, soothing, calming, tension reducing) on a recurrent basis, it may become the preferred way of achieving those effects, particularly in the absence of alternative ways of attaining those desired results. A primary task of treatment for problem substance users is to (1) identify the specific needs that alcohol and substances are being used to meet and (2) develop and reinforce skills that provide alternative ways of meeting those needs [10 , 11] .

CRA is a broad-spectrum cognitive behavioural programme for treating substance use and related problems by identifying the specific needs that alcohol and or other substances are satisfying or meeting. The goal is then to develop and reinforce skills that provide alternative ways of meeting those needs. Consistent with traditional CBT, CRA through exploration, allows the patient to identify negative thoughts, behaviours and beliefs that maintain addiction. By getting the patient to identify, positive non-drug using behaviours, interests, and activities, CRA attempts to provide alternatives to drug use. As therapy progresses the objective is to prevent relapse, increase wellness, and develop skills to promote and sustain well-being. The ultimate aim of CRA, as with CBT is to assist the patient to master a specific set of skills necessary to achieve their goals. Treatment is not complete until those skills are mastered and a reasonable degree of progress has been made toward attaining identified therapy goals. CRA sessions are highly collaborative, requiring the patient to engage in ‘between session tasks’ or homework designed reinforce learning, improve coping skills and enhance self efficacy in relevant domains.

The use of the Community Reinforcement Approach is empirically supported with inpatients [12 , 13] , outpatients [14 - 16] and homeless populations (Smith et al., 1998). In addition, three recent metaanalytic reviews cited CRA as one of the most cost-effective treatment programmes currently available [17 , 18] .

A-CRA is a evidenced based behavioural intervention that is an adapted version of the adult CRA programme [19] . Garner et al [19] modified several of the CRA procedures and accompanying treatment resources to make them more developmentally appropriate for adolescents. The main distinguishing aspect of A-CRA is that it involves caregivers—namely parents or guardians who are ultimately responsible for the adolescent and with whom the adolescent is living.

A-CRA has been tested and found effective in the context of outpatient continuing care following residential treatment [20 - 22] and without the caregiver components as an intervention for drug using, homeless adolescents [23] . More recently, Garner et al [19] collected data from 399 adolescents who participated in one of four randomly controlled trials of the A-CRA intervention, the purpose of which was to examine the extent to which exposure to A-CRA procedures mediated the relationship between treatment retention and outcomes. The authors found adolescents who were exposed to 12 or more A-CRA procedures were significantly more likely to be in recovery at follow-up.

Combining A-CRA with relapse prevention strategies receives strong support as an evidence based, best practice model and is widely employed in addiction treatment programmes. Providing a CBT-ACRA therapeutic approach is imperative as it develops alternative ways of meeting needs and thus altering dependence.

2. Case Introduction

Alan is a 17 year-old male currently living in County Dublin. Alan presented to the agency involuntarily and as a requisite of his Juvenile Liaison Officer who was seeing him on foot of prior drugs arrest for ‘possession with intent to supply’; a more serious charge than a simple ‘drugs possession’ charge. As Alan had no previous charges he was placed on probation for one year. This was Alan’s first contact with the treatment services. A diagnostic assessment was completed upon entry to treatment and included completion of a battery of instruments comprising the Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP), The World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) and the Beck Youth Inventory (BYI) (see appendices for full description of outcome measures) (Table 1).

3. Diagnostic Criteria

The apparent symptoms of substance dependency were: (1) Loss of Control - Alan had made several attempts at controlling the amounts of cannabis he consumed, but those times when he was able to abstain from cannabis use were when he substituted alcohol and/or other drugs. (2) Family History of Alcohol/Drug Usage - Alan’s eldest sister who is now 23 years old is in recovery from opiate abuse. She was a chronic heroin user during her early adult years [17 - 21] . During this period, which corresponds to Alan’s early adolescent years [12 - 15] she lived in the family home (3) Changes in Tolerance - Alan began per day. At presentation he was smoking six to eight cannabis joints daily through the week, and eight to twelve joints daily on weekends.

4. Psychosocial, Medical and Family History

At time of intake Alan was living with both of his parents and a sister, two years his senior, in the family home. Alan was the youngest and the only boy in his family. He had two other older sisters, 5 and 7 years his senior. He was enrolled in his 5th year of secondary school but at the time of assessment was expelled from all classes. Alan had superior sporting abilities. He played for the junior team of a first division football team and had the prospect of a professional career in football. He reported a family history positive for substance use disorders. An older sister was in recovery for opiate dependence. Apart from his substance use Alan reported no significant psychological difficulties or medical problems. His motives for substance use were cited as boredom, curiosity, peer pressure, and pleasure seeking. His triggers for use were relationship difficulties at home, boredom and peer pressure. Pre-morbid personality traits included thrill seeking and impulsivity (Table 2).

5. Case Conceptualisation

A CBT case formulation is based on the cognitive model, which hypothesizes that "a person’s feelings and emotions are influenced by their perception of events" . It is not the actual event that determines how the person feels, but rather how they construe the event (Beck, 1995 p14). Moreover, cognitive theory posits that the “child learns to construe reality through his or her early experiences with the environment, especially with significant others” and that “sometimes these early experiences lead children to accept attitudes and beliefs that will later prove maladaptive” [24] . A CBT formulation (or case conceptualisation) is one of the key underpinnings of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). It is the ‘blueprint’ which aids the therapist to understand and explain the patient’s’ problems.

Formulation driven CBT enables the therapist to develop an individualised understanding of the patient and can help to predict the difficulties that a patient may encounter during therapy. In Alan’s case, exploring his existing negative automatic thoughts about regarding school and his academic competences highlighted the difficulties he could experience with CBT homework completion. Whilst Alan was good at between session therapy assignments, an exploration of what is meant by ‘homework’ in a CBT context was crucial.

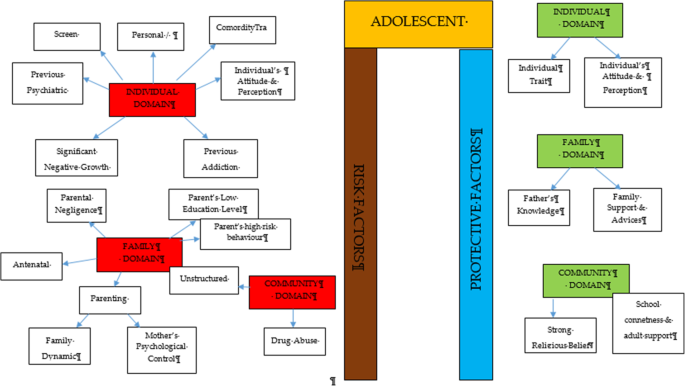

A collaborative CBT formulation was done diagrammatically together with Alan (Figure 1). This formulation aimed to describe his presenting problems and using CBT theory, to explore explanatory inferences about the initiating and maintaining factors of his drug use which could practically inform meaningful interventions.

Simmons and Griffiths et al. make the insightful observation that particular group differences need to be specifically considered and suggest that the therapist should be cognizant of the role of both society and culture when developing a formulation. They firstly suggest that the impact played by gender, sexuality and socio-cultural roles in the genesis of a psychological disorder, namely the contribution that being a member of a group may have on predisposing and precipitating factors, be carefully considered. An example they offer is the role of poverty on the development of psychological problems, such as the link evidenced between socio economic group and onset of schizophrenia. This was clearly evident in the case of Alan, who being a member of a deprived socioeconomic group, growing up and living in an area with a high level of economic deprivation, perceived that his choices for success were limited. His thinking, as an adolescent boy, was dichotomous in that he saw himself as having only two fixed and limited choices (a) being good at sport he either pursue a career as a professional sportsman or alternatively (b) he engage in crime and work his way up through the ranks as a ‘career criminal’. Simmons & Griffiths secondly suggest that being a member of a particular group can heavily influence a person’s understanding of the causality of their psychological disorder. A third consideration when developing a formulation is the degree to which being a member of a particular group may influence the acceptance or rejection of a member experiencing a psychological illness. Again this is pertinent in Alan’s case as he was part of a sub-group, a gang engaged in crime. For this cohort, crime and drug use were synonymous. Using drugs was viewed as a rite of passage for Alan.

Drug use, according to CBT models, are socially learned behaviours initiated, maintained and altered through the dynamic interaction of triggers, cues, reinforcers, cognitions and environmental factors. The application of a such a formulation, sensitive to Simmons and Griffiths (2009) aforementioned observations, proved useful in affording insights into the contextual and maintaining factors of Alan’s drug use which was heavily influenced by the availability of drugs ,his peer group (with whom he spent long periods of time) and their petty drug dealing and criminality. Similarly, engaging with his football team mates during the lead up to an important match significantly reduced his drug use and at certain times of the year even lead to abstinence. Sharing this formulation allowed him to note how his drug use patterns were driven, as per the CBT paradigm, by modifiable external, transient, and specific factors (e.g. cues, reinforcements, social networks and related expectations and social pressures).

Employing the A-CRA model allowed for this tailored fit as A-CRA specifically encourages the patient to identify their own need and desire for change. Alan identified the specific needs that were met by using substances and he developed and reinforced skills that provided him with alternative ways of meeting those needs. This model worked extremely well for Alan as he had identified and had ready access to a pro- social ‘alternative group’ or community. As he had had access to an alternative positive peer group and another activity (sport) which he was ‘really good at’, he simply needed to see the evidence of how his context could radically affect his substance use; more specifically how his beliefs, thinking and actions in certain circumstances produced very different drug use consequences and outcomes.

6. Course of Treatment and Assessment of Progress

One focus of CBT treatment is on teaching and practising specific helpful behaviours, whilst trying to limit cognitive demands on clients. Repetition is central to the learning process in order to develop proficiency and to ensure that newly acquired behaviours will be available when needed. Therefore, behavioural using rehearsal will emphasize varied, realistic case examples to enhance generalization to real life settings. During practice periods and exercises, patients are asked to identify signals that indicate high-risk situations, demonstrating their understanding of when to use newly acquired coping skills. CBT is designed to remedy possible deficits in coping skills by better managing those identified antecedents to substance use. Individuals who rely primarily on substances to cope have little choice but to resort to substance use when the need to cope arises. Understanding, anticipating and avoiding high risk drug use scenarios or the “early warning signals” of imminent drug use is a key CBT clinical activity.

A major goal of a CBT/A-CRA therapeutic approach is to provide a range of basic alternative skills to cope with situations that might otherwise lead to substance use. As ‘skill deficits’ are viewed as fundamental to the drug use trajectory or relapse process, an emphasis is placed on the development and practice of coping skills. A-CRA was manualised in 2001 as part of the Cannabis Youth Treatment Series (CYT) and was tested in that study [21] and more recently with homeless youth [23] . It was also adapted for use in a manual for Assertive Continuing Care following residential treatment [20] .

There are twelve standard and three optional procedures proposed in the A-CRA model. The delivery of the intervention is flexible and based on individual adolescent needs, though the manual provides some general guidelines regarding the general order of procedures. Optional procedures are ‘Dealing with Failure to Attend’, ‘Job-Seeking Skills’, and ‘Anger Management’. Standard procedures are included in table 3 below. For a more detailed description of sessions and procedures please see appendices.

Smith and Myers describe the theoretical underpinnings of CRA as a comprehensive behavioural program for treating substance-abuse problems. It is based on the belief that environmental contingencies can play a powerful role in encouraging or discouraging drinking or drug use. Consequently, it utilizes social, recreational, familial, and vocational reinforcers to assist consumers in the recovery process. Its goal is to essentially make a sober lifestyle more rewarding than the use of substances. Interestingly the authors note: ‘Oddly enough, however, while virtually every review of alcohol and drug treatment outcome research lists CRA among approaches with the strongest scientific evidence of efficacy, very few clinicians who treat consumers with addictions are familiar with it’. ‘The overall philosophy is to promote community based rewarding of non drug-using behaviour so that the patient makes healthy lifestyle changes’ p.3 [25] .

A-CRA procedures use ‘operant techniques and skills training activities’ to educate patients and present alternative ways of dealing with challenges without substances. Traditionally, CRA is provided in an individual, context-specific approach that focuses on the interaction between individuals and those in their environments. A-CRA therapists teach adolescents when and where to use the techniques, given the reality of each individual’s social environment. This tailored approach is facilitated by conducting a ‘functional analysis’ of the adolescent’s behaviour at the beginning of therapy so they can better understand and interrupt the links in the behavioural chain typically leading to episodes of drug use. A-CRA therapists then teach individuals how to improve communication and other skills, build on their reinforcers for abstinence and use existing community resources that will support positive change and constructive support systems.

A-CRA emphasises lapse and relapse prevention. Relapseprevention cognitive behavioural therapy (RP-CBT) is derived from a cognitive model of drug misuse. The emphasis is on identifying and modifying irrational thoughts, managing negative mood and intervening after a lapse to prevent a full-blown relapse [26] . The emphasis is on development of skills to (a) recognize High Risk Situations (HRS) or states where clients are most vulnerable to drug use, (b) avoidance of HRS, and (C) to use a variety of cognitive and behavioural strategies to cope effectively with these situations. RPCBT differs from typical CBT in that the accent is on training people who misuse drugs to develop skills to identify and anticipate situations or states where they are most vulnerable to drug use and to use a range of cognitive and behavioural strategies to cope effectively with these situations [26] .

7. Access and Barriers to Care

Alan engaged with the service for eight months. During this time he received twenty sessions, three of which were assessment focused, the remaining seventeen sessions were A-CRA focused; two of the seventeen involved his mother, the remaining fifteen were individual. As Alan was referred by the probation services, he was initially somewhat ambivalent about drug use focussed interventions. His early motivation for engagement was primarily to avoid the possibility of a custodial sentence.

8. Treatment

My sessions with Alan were guided by the principles of A-CRA [27] which focuses on coping skills training and relapse prevention approaches to the treatment of addictive disorders. Prior to engaging with Alan, I had completed the training course and commenced the A-CRA accreditation process, both under the stewardship of Dr Bob Meyers, whose training and publication offers detailed guidelines on skills training and relapse prevention with young people in a similar context [27] .

During the early part of each session I focused on getting a clear understanding of Alan’s current concerns, his general level of functioning, his substance abuse and pattern of craving during the past week. His experiences with therapy homework, the primary focus being on what insight he gained by completing such exercises was also explored. I spent considerable time engaged in a detailed review of Alan’s experience with the implementation of homework tasks during which the following themes were reviewed:

-Gauging whether drug use cessation was easier or harder than he anticipated? -Which, if any, of the coping strategies worked best? -Which strategies did not work as well as expected. Did he develop any new strategies? -Conveying the importance of skills practice, emphasising how we both gained greater insights into how cognitions influenced his behaviour. After developing a clear sense of Alan’s general functioning, current concerns and progress with homework implementation, I initiated the session topic for that week. I linked the relevance of the session topic to Alan’s current cannabis-related concerns and introduced the topic by using concrete examples from Alan’s recent experience. While reviewing the material, I repeatedly ensured that Alan understood the topic by asking for concrete examples, while also eliciting Alan’s views on how he might use these particular skills in the future.

Godley & Meyers [21] propose a homework exercise to accompany each session. An advantage of using these homework sheets is that they also summarise key points about each topic and therefore serve as a useful reminder to the patient of the material discussed each week. Meyers, et al. (2011) suggests that rather than being bound by the suggested exercises in the manualised approach, they may be used as a starting point for discussing the best way to implement the required skill and to develop individualised variations for new assignments [27] . The final part of each session focused on Alan’s plan for the week ahead and any anticipated high-risk situations. I endeavoured to model the idea that patients can literally ‘plan themselves out of using’ cannabis or other drugs. For each anticipated high-risk situation, we identified appropriate and viable coping skills. Better understanding, anticipating and planning for high-risk situations was difficult in the beginning of treatment as Alan was not particularly used to planning or thinking through his activities. For a patient like Alan, whose home life is often chaotic, this helped promote a growing sense of self efficacy. Similarly, as Alan had been heavily involved with drug use for a long time, he discovered through this process that he had few meaningful activities to fill his time or serve as alternatives to drug use. This provided me with an opportunity to discuss strategies to rebuild an activity schedule and a social network.

During our sessions, several skill topics were covered. I carefully selected skills to match Alan’s needs. I selected coping skills that he has used in the past and introduced one or two more that were consistent with his cognitive style. Alan’s cognitive score indicated a cognitive approach reflecting poor problem solving or planning. Sessions focused on generic skills including interpersonal skills, goal setting, coping with criticism or anger, problem solving and planning. The goal was to teach Alan how to build on his pro- social reinforcers, how to use existing community resources supportive of positive change and how to develop a positive support system.

The sequence in which these topics were presented was based on (a) patient needs and (b) clinician judgment (a full description of individual sessions may be found in appendices).

A-CRA procedures use ‘operant techniques and skills training activities’ to educate patients and present alternative ways of dealing with challenges without substances. Traditionally, CRA is provided in an individual, context-specific approach that focuses on the interaction between individuals and those in their environments. A-CRA therapists teach adolescents when and where to use the techniques, given the reality of each individual’s social environment.

9. Assessment of Treatment Outcome

A baseline diagnostic assessment of outcomes was completed upon treatment entry. This assessment consisted of a battery of psychological instruments including (see appendices for full a description of assessment measures):

-The Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP). -The Beck Youth Inventories. -The World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST).

In addition to the above, objective feedback on Alan’s clinical and drug use status through urine toxicology screens was an important part of his drug treatment. Urine specimens were collected before each session and available for the following session. The use of toxicology reports throughout treatment are considered a valuable clinical tool. This part of the session presents a good opportunity to review the results of the most recent urine toxicology screen and promote meaningful therapeutic activities in the context of the patient’s treatment goals [28] .

In reporting on substance use since the last session, patients are likely to reveal a great deal about their general level of functioning and the types of issues and problems of most current concern. This allows the clinician to gauge if the patient has made progress in reducing drug use, his current level of motivation, whether there is a reasonable level of support available in efforts to remain abstinent and what is currently bothering him. Functional analyses are opportunistically used throughout treatment as needed. For example, if cannabis use occurs, patients are encouraged to analyse antecedent events so as to determine how to avoid using in similar situations in the future. The purpose is to help the patient understand the trajectory and modifiable contextual factors associated with drug use, challenge unhelpful positive drug use expectancies, identify possible skills deficiencies as well as seeking functionally equivalent non- drug using behaviours so as to reduce the probability of future drug use. The approach I used is based on the work of [28] .

The Functional Analysis was used to identify a number of factors occurring within a relatively brief time frame that influenced the occurrence of problem behaviours. It was used as an initial screening tool as part of a comprehensive functional assessment or analysis of problem behaviour. The results of the functional analysis then served as a basis for conducting direct observations in a number of different contexts to attest to likely behavioural functions, clarify ambiguous functions, and identify other relevant factors that are maintaining the behaviour.

The Happiness Scale rates the adolescent’s feelings about several critical areas of life. It helps therapists and adolescents identify areas of life that adolescents feel happy about and alternatively areas in which they have problems or challenges. Most importantly it identifies potential treatment goals subjectively meaningful to the patient, facilitates positive behaviour change in a range of life domains as well as help clients track their progress during treatment.

Alan’s BYI score (Table 4) indicates that at the time of assessment he was within the average scoring range on ‘self-concept’, and moderately elevated in the areas of ‘depression’, ‘anxiety’, and ‘disruptive behaviour’. His score for ‘anger’ suggested that his anger fell within the extremely elevated range. When this was discussed with Alan he agreed that this was quite accurate. Anger, and in particular controlling his anger, was subjectively identified as a treatment goal.

10. Follow-up

Given that follow-up occurred by telephone it was not feasible to administer the full battery of tests. With Alan’s treatment goals in mind it was decided to administer the MAP and ASSIST. Table 5 below illustrates Alan’s score at baseline and follow-up for the MAP and ASSIST. For summary purposes I have taken areas for concern at baseline for both instruments.

Alan’s score for cannabis was the most clinically relevant as it placed him in the 'high risk’ domain while his alcohol score indicated that he had engaged in binge drinking (6+ drinks) at T1. However, at T2 Alan’s score suggests that he had made considerable reductions in the use of both substances. Also his MAP scores for parental conflict and drug dealing suggest that he had also made major positive changes in the relevant domains of personal and social functioning as well as ceasing criminal behaviour.

At 3 months post-discharge I contacted Alan by phone. He had maintained and continued to further his progress. His drug use was at a minimal level (1 or 2 shared joints per month). He was no longer engaged in crime and his probationary period with the judicial system had passed. He had received a caution for his earlier drugs charge. At the time of follow-up he was enjoying participating in a Sports Coaching course and was excelling with his study assignments. Relationships had improved considerably with his mother and sister and he had re-engaged with a previous, positive, peer group linked to his involvement with the GAA . Overall he felt he was doing extremely well.

11. Complicating Factors with A-CRA Model

There are many challenges that may arise in the treatment of substance use disorders that can serve as barriers to successful treatment. These include acute or chronic cognitive deficits, health problems, social stressors and a lack of social resources [7] . Among individuals presenting with substance use there are often other significant life challenges including early school leaving, family conflicts, legal issues, poor or deviant social networks, etc. A particular challenge with Alan’s case was the social and environmental milieu which he shared with his drug using peers. For Alan, who initially had few skills and resources, engaging in treatment meant not only being asked to change his overall way of life but also to renounce some of those components in which he enjoyed a sense of belonging, particularly as he had invested significantly in these friendships. A sense of ‘belonging to the substance use culture’ can increase ambivalence for change [7] . Alan’s mother strongly disapproved of his drug using peer group and failed to acknowledge Alan’s perceived loss. This resulted in mother- son conflict. The use of the caregiver session allowed an exploration of perceived ‘losses’ relative to the ‘gains’ associated with Alan’s abstinence. It was moreover seen to be critical to establish alternatives for achieving a sense of belonging, including both his social connection and his social effectiveness. Alan’s sports ability allowed for this to be fostered. He is a talented sportsman which often meant his acceptance within a team or group is a given.

Despite the positive effects of A-CRA it is not without its shortcomings. The approach is at times quite American- oriented, particularly around identifying local resources and its focus on culturally specific outlets in promoting social engagement as alternatives to substance use. While this is supported in the literature, it may not necessarily be transferable to certain Irish adolescent contexts or subcultures.

12. Treatment Implications of the Case

A-CRA captures a broad range of behavioural treatments including those targeting operant learning processes, motivational barriers to improvement and other more traditional elements of cognitivebehavioural interventions. Overall, this intervention has demonstrated efficacy. Despite this heterogeneity, core elements emerge based in a conceptual model of SUDs as disorders characterized by learning processes and driven by the strongly reinforcing effects of the substances of abuse. There is rich evidence in the substance use disorders literature that improvement achieved by CBT (7) and indeed A-CRA (Godley et al. and Garner et al. [22 , 20] ) generalizes to all areas of functioning, including social, work, family and marital adjustment domains. The present study’s finding that a reduction in substance-related symptoms was accompanied by improved levels of functioning, social adjustment and enhanced quality of life, provides further support for this point.

In conclusion, there is some preliminary evidence that A-CRA is a promising treatment in the rehabilitation of adolescent substance users in Ireland and culturally similar societies. Clearly, results from a case study have limited generalisability and there is need for larger controlled studies providing robust outcomes to confirm the efficacy of A-CRA in an Irish context. A more systematic study of this issue is in the interest of adolescent substance users and the health services providers faced with the challenge of providing affordable, evidencebased mental health and addiction care to young people.

13. Recommendations to Clinicians and Students

The ACRA model is a structured assemblage of a range of cognitive and behavioural activities (e.g. a rationale and overview of the paradigm, sobriety sampling, functional analyses, communication skills, problem solving skills, refusal skills, jobs counselling, anger management and relapse prevention) which are shared in varying degrees with other CBT approaches. The ACRA model has the advantage of established effectiveness. A foundation in empirical research together with its manual- supported approach results in it being an appropriate “off the shelf ” intervention, highly applicable to many adolescent substance misusers. Such a focussed approach also has the advantage of limiting therapist “drift”. Notwithstanding the accessible manual and other resources available on- line, clinicians and students are strongly encouraged to undergo accredited ACRA training and supervision.

Unfortunately such a structured model, despite its many advantages, does have limitations. This model may not meet the sum of all drug misusing adolescent service user treatment needs, nor is it applicable to all adolescent drug users, particularly highly chaotic individuals with high levels of co- morbidities or multi-morbidities as often found in this population [29 , 30] . Whilst focussing on specifically on drug use, ACRA does not directly address co-existing problem behaviours or challenges such as depression, anxiety, personality disorder, or post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) synergistically linked to drug use. It is possible that given the high levels of dual diagnoses encountered in this population as well as the compounding effect that drug use exerts on multiple systems, clinicians and practitioners may find a strict application of the ACRA model limiting, necessitating the application of an additional range or layer of psychotherapeutic competencies? Additionally the ACRA model does not focus explicitly on other psychological activities useful in the treatment of drug misuse such as the control and management of unhelpful cognitive styles or habits; breathing or progressive relaxation skills; anger management; imagery, visualisation and mindfulness. That is, as a manual based approach comprising a number of fixed components, a major potential challenge facing clinicians and students is the tension they may experience between maintaining strict fidelity to a pure ACRA approach, versus the flexibility l approved by more formulation driven CBT approaches?

The advantages of a skilled application of a formulation driven approach which are cited and summarised in are multiple and include the collaborative nature of goal setting, the facilitation of problem prioritisation in a meaningful and useful manner; a more immediate direction and structuring of the course of treatment; the provision of a rationale for the most fitting intervention point or spotlight for the treatment; an integration of seemingly unrelated or dissimilar difficulties in a meaningful yet parsimonious fashion; an influence on the choice of procedures and “homework” exercises; theory based mechanisms to understand the dynamics of the therapeutic relationship and a sense of targeted and ‘extra-therapeutic’ issues and how they could be best explained and managed, especially in terms of precipitators or triggers, core beliefs, assumptions and automatic thoughts.

Thus given the above observations and together with the importance placed on engagement and retention, the high variability in the cognitive, emotional, social and developmental domains [4] differences in roles (e.g. teenagers who are also parents) and levels of autonomy as well as high degrees of dual diagnosis or co- morbidities found in this group [29 , 30] practitioners are encouraged to also develop competencies in allied psychological treatment models such as Motivational Interviewing [31] ; familiarity with the core principles of CBT, disorder specific and problem-specific CBT competences, the generic and meta- competences of CBT as well as an advanced knowledge and understanding of mental health problems that will provide practitioners with the confidence and capacity to implement treatment models in a more flexible yet coherent manner,. In addition to seeking supervision and mentorship students and practitioners are directed, as a starting point, to University College London’s excellent resources outlining the competencies required to provide a more comprehensive interventions [11] .

Both authors reported no conflict of interest in the content of this paper.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: JI. Recruitment & assessment and on going treatment t of patient JI. On going supervision of case KD. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: JI, & KD. Wrote the paper: JI. Contributed to final draft paper KD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Adolescent Addiction Services, Health Service Executive.

- Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF (2007) Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64: 566-576. View

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF (2007) Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64: 830-842. View

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Ball SA, McCance E, Frankforter TL, et al. (2000) Oneyear follow-up of disulfiram and psychotherapy for cocaine-alcohol users: sustained effects of treatment. Addiction 95: 1335-1349. View

- Stetler CB, Ritchie J, Rycroft-Malone J, Schultz A, Charns M (2007) Improving quality of care through routine, successful implementation of evidence-based practice at the bedside: an organizational case study protocol using the Pettigrew and Whipp model of strategic change. Imp Sci 2: 1-13. View

- Carroll KM, Fenton LR, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, et al. (2004) Efficacy of disulfiram and cognitive behavior therapy in cocaine-dependent outpatients: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61: 264-272. View

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Babuscio TA, et al. (2008) Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy for addiction: a randomized trial of CBT4CBT. Am J Psychiatry 165: 881-888. View

- McHugh RK, Hearon BA, Otto MW (2010) Cognitive behavioral therapy for substance use disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 33: 511-525. View

- Waldron HB, Kaminer Y (2004) On the learning curve: the emerging evidence supporting cognitive-behavioral therapies for adolescent substance abuse. Addiction 99 Suppl 2: 93-105. View

- Freeman A, Reinecke MA (1995) Cognitive therapy. New York: Guilford Press.

- Stephens RS, Babor TF, Kadden R, Miller M; Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group (2002) The Marijuana Treatment Project: rationale, design and participant characteristics. Addiction 97 Suppl 1: 109-124. View

- Pilling S, Hesketh K, Mitcheson L (2009) Psychosocial interventions in drug misuse: a framework and toolkit for implementing NICE-recommended treatment interventions. London: British Psychological Society, Centre for Outcomes, Research and Effectiveness (CORE) Research Department of Clinical, Educational and Health Psychology, University College. View

- Azrin NH (1976) Improvements in the community-reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behav Res Ther 14: 339-348. View

- Hunt GM, Azrin NH (1973) A community-reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behav Res Ther 11: 91-104. View

- Azrin NH, Sisson RW, Meyers R, Godley M (1982) Alcoholism treatment by disulfiram and community reinforcement therapy. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 13: 105-112. View

- Meyers RJ, Miller WR (2001) A community reinforcement approach to addiction treatment: (International Research Monographs in the Addictions) Cambridge Univ Press.

- Mallams JH, Godley MD, Hall GM, Meyers RJ (1982) A social-systems approach to resocializing alcoholics in the community. J Stud Alcohol 43: 1115-1123.

- Finney JW, Monahan SC (1996) The cost-effectiveness of treatment for alcoholism: a second approximation. J Stud Alcohol 57: 229-243. View

- Rollnick S, Miller WR (1999) What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychotherapy. 23: 325-334. View

- Garner BR, Barnes B, Godley SH (2009) Monitoring fidelity in the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA): the training process for A-CRA raters. J Behav Anal Health Fit Med 2: 43-54. View

- Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, Tims FM, Babor T, et al. (2004) The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: main findings from two randomized trials. J Subst Abuse Treat 27: 197-213. View

- Garner BR, Godley MD, Funk RR, Dennis ML, Godley SH (2007) The impact of continuing care adherence on environmental risks, substance use, and substance-related problems following adolescent residential treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 21: 488-497. View

- Slesnick N, Prestopnik JL, Meyers RJ, Glassman M (2007) Treatment outcome for street-living, homeless youth. Addict Behav 32: 1237-1251. View

- Beck AT, Hollon SD, Young JE, Bedrosian RC, Budenz D (1985) Treatment of depression with cognitive therapy and amitriptyline. Arch Gen Psychiatry 42: 142-148. View

- Smith C (1998) Assessing health needs in women's prisons. PSJ 224.

- Maude-Griffin PM1, Hohenstein JM, Humfleet GL, Reilly PM, Tusel DJ, et al. (1998) Superior efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for urban crack cocaine abusers: main and matching effects. J Consult Clin Psychol 66: 832-837. View

- Godley SH, Meyers RJ, Smith JE, Karvinen T, Titus JC, et al. (2001) The adolescent community reinforcement approach for adolescent cannabis users: US Department of Health and Human Services. View

- Carroll KM (1998) A cognitive-behavioral approach: Treating cocaine addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse. View

- Bukstein OG, Glancy LJ, Kaminer Y (1992) Pattern of affective comorbidity in a clinical population of dually diagonised adolescent substance abusers. J Ame Aca Child Adol Psychiat 31: 1041-1045. View

- Kaminer Y, Burleson JA, Goldberger R (2002) Psychotherapies for adolescent substance abusers: Short- and long-term outcomes. J Nerv Ment Dis 190: 737-745.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S (2002) Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press. View

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Routes of Drug Use Among Drug Overdose Deaths — United States, 2020–2022

Weekly / February 15, 2024 / 73(6);124–130

Lauren J. Tanz, ScD 1 ; R. Matt Gladden, PhD 1 ; Amanda T. Dinwiddie, MPH 1 ; Kimberly D. Miller, MPH 1 ; Dita Broz, PhD 2 ; Eliot Spector, MS 1 ,3 ; Julie O’Donnell, PhD 1 ( View author affiliations )

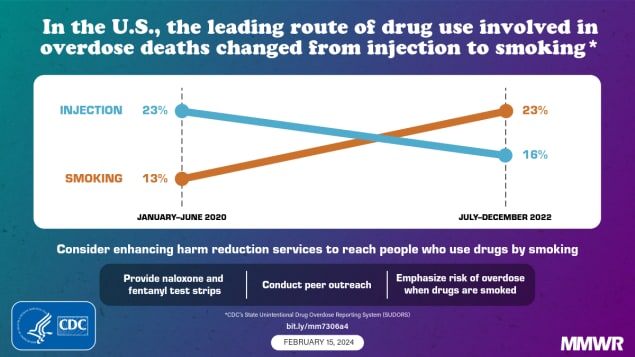

What is already known about this topic?

More than 109,000 drug overdose deaths occurred in the United States in 2022; nearly 70% involved illegally manufactured fentanyls (IMFs). Data from the western United States suggested a transition from injecting heroin to smoking IMFs.

What is added by this report?

From January–June 2020 to July–December 2022, the percentage of overdose deaths with evidence of smoking increased 73.7%, and the percentage with evidence of injection decreased 29.1%; similar changes were observed in all U.S. regions. Changes were most pronounced in deaths with IMFs detected, with or without stimulant detection.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Strengthening and expanding public health and harm reduction services to address overdose risk with smoking and other noninjection routes might reduce deaths.

- Article PDF

- Full Issue PDF

Preliminary reports indicate that more than 109,000 drug overdose deaths occurred in the United States in 2022; nearly 70% of these involved synthetic opioids other than methadone, primarily illegally manufactured fentanyl and fentanyl analogs (IMFs). Data from the western United States suggested a transition from injecting heroin to smoking IMFs. CDC analyzed data from the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System to describe trends in routes of drug use in 27 states and the District of Columbia among overdose deaths that occurred during January 2020–December 2022, overall and by region and drugs detected. From January–June 2020 to July–December 2022, the percentage of overdose deaths with evidence of injection decreased 29.1%, from 22.7% to 16.1%, whereas the percentage with evidence of smoking increased 73.7%, from 13.3% to 23.1%. The number of deaths with evidence of smoking increased 109.1%, from 2,794 to 5,843, and by 2022, smoking was the most commonly documented route of use in overdose deaths. Trends were similar in all U.S. regions. Among deaths with only IMFs detected, the percentage with evidence of injection decreased 41.6%, from 20.9% during January–June 2020 to 12.2% during July–December 2022, whereas the percentage with evidence of smoking increased 78.9%, from 10.9% to 19.5%. Similar trends were observed among deaths with both IMFs and stimulants detected. Strengthening public health and harm reduction services to address overdose risk related to diverse routes of drug use, including smoking and other noninjection routes, might reduce drug overdose deaths.

Introduction

Preliminary data indicate that U.S. drug overdose deaths surpassed 109,000 in 2022; nearly 70% of these deaths involved synthetic opioids other than methadone, primarily illegally manufactured fentanyl and fentanyl analogs (IMFs).* In recent years, deaths co-involving IMFs and stimulants have increased steadily ( 1 ). The estimated number of U.S. adults who inject drugs increased from approximately 774,000 in 2011 to nearly 3.7 million in 2018, corresponding to shifts from prescription opioid misuse to the use of heroin and IMFs ( 2 ). More recent data suggest transitions from injecting heroin to smoking IMFs; however, limited data exist on recent changes in routes of drug use for all drugs, and for IMFs beyond the western United States † ( 3 , 4 ). Routes of drug use have implications for overdose risk, infectious disease transmission, other comorbidities, and harm reduction services ( 5 ).

Jurisdictions entered data from death certificates, postmortem toxicology testing, and medical examiner or coroner reports on unintentional and undetermined intent drug overdose deaths into CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS). § Routes of drug use were identified using information from scene investigations, witness reports, or autopsy data and were categorized into nonmutually exclusive categories of ingestion, ¶ injection,** smoking, †† and snorting §§ ; other routes (e.g., transdermal) are not presented because sample sizes were small. Among 28 jurisdictions ¶¶ with complete data,*** numbers and percentages of overdose deaths were calculated by route of drug use and by 6-month period during January 2020–December 2022, overall, and for each U.S. Census Bureau region. ††† To understand how routes of drug use are related to drugs commonly involved in overdose deaths, percentages of overdose deaths with evidence of each route were calculated by 6-month period for mutually exclusive categories of drugs detected (IMFs §§§ only, stimulants only, both IMFs and stimulants, and neither IMFs nor stimulants) ¶¶¶ ( 6 ). Analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute). This activity was reviewed by CDC, deemed not research, and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.****

Overall Trends

During January 2020–December 2022, a total of 139,740 overdose deaths occurred in 28 jurisdictions; deaths increased 20.2%, from 21,046 during January–June 2020 to 25,301 during July–December 2022. The percentage of deaths with IMFs detected increased 8.4% from 71.4% during January–June 2020 to 77.4% during July–December 2022. Evidence of at least one route of drug use was documented in 71,480 (51.2%) overdose deaths. From January–June 2020 to July–December 2022, the number and percentage of overdose deaths with evidence of smoking increased 109.1% (from 2,794 to 5,843) and 73.7% (from 13.3% to 23.1%), respectively ( Figure 1 ). The number and percentage of deaths with evidence of snorting increased 43.1% (from 2,858 to 4,090) and 19.1% (from 13.6% to 16.2%), respectively. In contrast, the number and percentage of overdose deaths with evidence of injection decreased 14.6% (from 4,780 to 4,080) and 29.1% (from 22.7% to 16.1%), respectively, from January–June 2020 to July–December 2022. Although the number of deaths with evidence of ingestion increased 14.6%, from 3,189 to 3,656, the percentage of such deaths declined 4.6%, from 15.2% to 14.5%.

The leading route of use in drug overdose deaths changed from injection during January–June 2020 (22.7% of deaths) compared with ingestion (15.2%), snorting (13.6%), and smoking (13.3%) to smoking during July–December 2022 (23.1% of deaths) compared with snorting (16.2%), injection (16.1%), and ingestion (14.5%). During July–December 2022, most deaths with evidence of smoking (79.7%), snorting (84.5%), or ingestion (86.5%) had no evidence of injection; among deaths with information on route of use, 81.9% had evidence of a noninjection route.

Regional Trends

Regional trends were largely consistent with overall trends. The percentage of overdose deaths with evidence of smoking increased in all U.S. Census Bureau regions (Northeast: 91.0% increase, from 8.9% to 17.0%; Midwest: 75.0%, from 12.4% to 21.7%; South: 48.0%, from 12.5% to 18.5%; and West: 68.9%, from 25.1% to 42.4%) ( Figure 2 ). The percentage of deaths with evidence of snorting increased in three regions (Northeast: 28.2%, from 11.7% to 15.0%; Midwest: 23.0%, from 13.9% to 17.1%; and South: 12.4%, from 14.5% to 16.3%). The percentage with evidence of injection decreased in all regions (Northeast: −21.2%, from 21.2% to 16.7%; Midwest: −36.2%, from 21.8% to 13.9%; South: −27.8%, from 25.9% to 18.7%; and West: −34.3%, from 19.8% to 13.0%). By July–December 2022, smoking was the most commonly identified route of use in overdose deaths in the Midwest (21.7%) and West (42.4%); injection and smoking were most common in the Northeast (16.7% and 17.0%, respectively) and South (18.7% and 18.5%, respectively).

Trends by Drugs Detected

Among overdose deaths with only IMFs detected (13,107; 9.6%), deaths with both IMFs and stimulants detected (58,754; 43.1%), and deaths with only stimulants detected (8,525; 6.2%), the percentage with evidence of smoking increased, and the percentage with evidence of injection decreased from January–June 2020 to July–December 2022 ( Figure 3 ). For IMFs only, the percentage of overdose deaths with evidence of smoking increased 78.9%, from 10.9% to 19.5%, whereas the percentage with evidence of injection decreased 41.6%, from 20.9% to 12.2%. Among deaths with both IMFs and stimulants detected, the percentage with evidence of smoking increased 65.4%, from 17.9% to 29.6%, whereas the percentage with evidence of injection decreased 25.5%, from 28.6% to 21.3%. A similar pattern was observed among deaths with only stimulants detected (smoking: 29.7% increase, from 15.5% to 20.1%; injection: 22.5% decrease, from 10.2% to 7.9%). Among deaths with neither IMFs nor stimulants detected (10,628; 7.8%), the percentage with evidence of smoking did not change, and the percentage with evidence of injection decreased 42.2% (11.6% to 6.7%); ingestion was the most common route during July–December 2022 (39.4% of deaths) and throughout the study period.

The percentage of drug overdose deaths with evidence of smoking increased sharply in all U.S. regions from 2020 to 2022, indicating the importance of an updated response. By late 2022, among decedents with information on route of drug use, more than three fourths had evidence of a noninjection route, highlighting the diversification of methods through which they used drugs.

From January–June 2020 to July–December 2022, the number of overdose deaths with evidence of smoking doubled, and the percentage of deaths with evidence of smoking increased across all geographic regions. By late 2022, smoking was the predominant route of use among drug overdose deaths overall and in the Midwest and West regions. Increases were most pronounced when IMFs were detected, with or without stimulants. Increases in the number and percentage of deaths with evidence of smoking, and the corresponding decrease in those with evidence of injection, might be partially driven by 1) the transition from injecting heroin to smoking IMFs ( 3 , 4 ), 2) increases in deaths co-involving IMFs and stimulants that might be smoked †††† ( 1 ), and 3) increases in the use of counterfeit pills, which frequently contain IMFs and are often smoked ( 7 ). Motivations for transitioning from injection to smoking include fewer adverse health effects (e.g., fewer abscesses), reduced cost and stigma, sense of more control over drug quantity consumed per use (e.g., smoking small amounts during a period versus a single injection bolus), and a perception of reduced overdose risk among persons who use drugs ( 3 , 5 , 8 ). These motivations might also signify lower barriers for initiating drug use by smoking, or for transitioning from ingestion to smoking; compared with ingestion, smoking can intensify drug effects and increase overdose risk ( 9 ). Despite some risk reduction associated with smoking compared with injection (e.g., fewer bloodborne infections), smoking carries substantial overdose risk because of rapid drug absorption ( 5 , 9 ).

Nearly 80% of overdose deaths with evidence of smoking had no evidence of injection; persons who use drugs by smoking but do not inject drugs might not use traditional syringe services programs where harm reduction messaging and supplies are often provided. In response, some jurisdictions have adapted harm reduction services to provide safer smoking supplies or established health hubs to expand reach to persons using drugs through noninjection routes. §§§§ In addition, harm reduction services (e.g., peer outreach and provision of fentanyl test strips for testing drug products and naloxone to reverse opioid overdoses), messaging specific to smoking drugs, and linkage to treatment for substance use disorders can be integrated into other health care delivery (e.g., emergency departments) and public safety (e.g., drug diversion) settings.

The percentage and number of deaths with evidence of injection decreased across regions and drug categories. Observed decreases might reflect transitions to noninjection routes and response to public health efforts to reduce injection drug use because of its risk for overdose and infectious disease transmission ( 3 , 4 , 10 ). Despite these declines, more than 4,000 drug overdose deaths had evidence of injection during July–December 2022. Syringe services programs help to engage persons who use drugs in services ( 10 ); sustained efforts to provide sterile injection supplies, additional harm reduction tools, and linkage to treatment for substance use disorders, including medications for opioid use disorder, are important for further reduction in the number of overdose deaths from injection drug use. Lessons learned from implementing syringe services programs could be applied to other harm reduction and outreach models to reach more persons who use drugs by any route.

Limitations

The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, analyses included 28 jurisdictions; results might not be generalizable to the rest of the United States. Second, for nearly one half of deaths, no information about route of drug use was available; thus, percentages of deaths with evidence of each route are underestimated. However, no notable differences by time or demographic characteristics among deaths with and without route of drug use information were identified. Third, percentages of noninjection routes are likely underestimated more than those with injection because evidence of injection is easier to identify (e.g., syringes) than evidence of other routes (e.g., stems and straws can be evidence of snorting or smoking). Finally, routes could not be linked to the use of a specific drug unless only one drug class was detected. Analyses of single drug classes detected (IMFs only and stimulants only) were presented to better link routes to drugs.

Implications for Public Health Practice