An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Digg

Latest Earthquakes | Chat Share Social Media

Water Dowsing

Groundwater photo gallery, learn about groundwater through pictures, groundwater data for the nation, the usgs national water information system (nwis) contains extensive groundwater data for thousands of sites nationwide., groundwater information by topic, water science school home.

- Publications

"Water dowsing" refers in general to the practice of using a forked stick, rod, pendulum, or similar device to locate underground water, minerals, or other hidden or lost substances, and has been a subject of discussion and controversy for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

• Water Science School HOME • Groundwater topics •

What is water dowsing?

"Water dowsing" refers in general to the practice of using a forked stick, rod, pendulum, or similar device to locate underground water , minerals, or other hidden or lost substances, and has been a subject of discussion and controversy for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

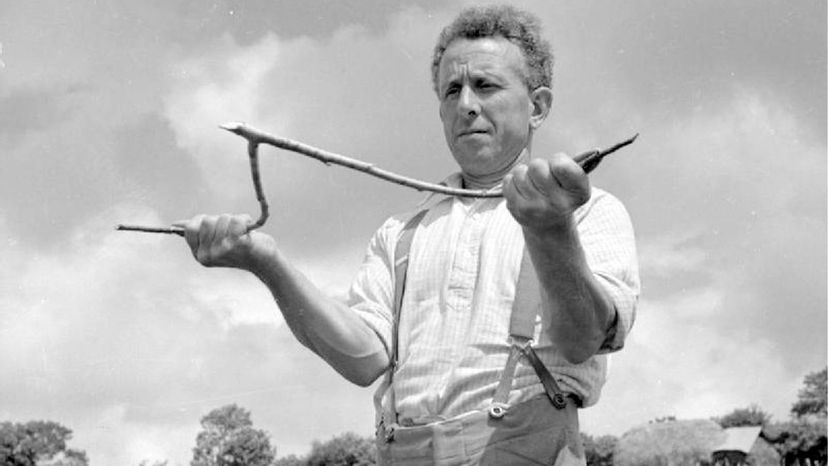

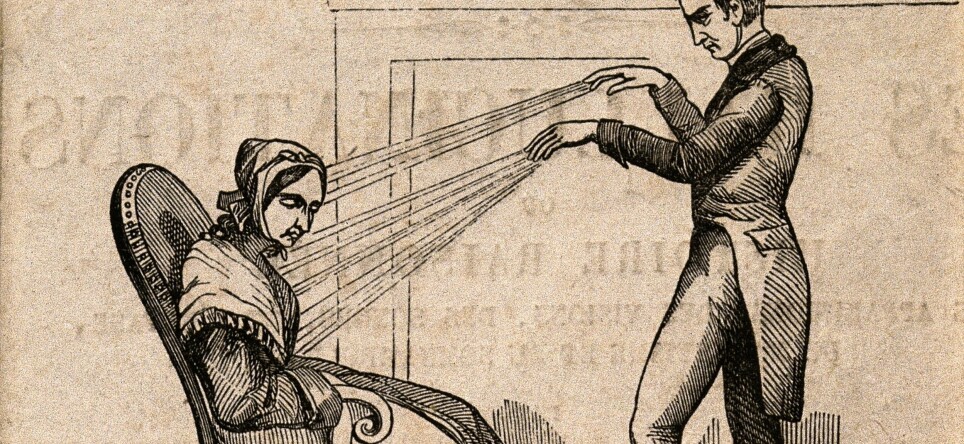

Although tools and methods vary widely, most dowsers (also called diviners or water witches) probably still use the traditional forked stick, which may come from a variety of trees, including the willow, peach, and witchhazel. Other dowsers may use keys, wire coat hangers, pliers, wire rods, pendulums, or various kinds of elaborate boxes and electrical instruments.

In the classic method of using a forked stick, one fork is held in each hand with the palms upward. The bottom or butt end of the "Y" is pointed skyward at an angle of about 45 degrees. The dowser then walks back and forth over the area to be tested. When she/he passes over a source of water, the butt end of the stick is supposed to rotate or be attracted downward.

Water dowsers practice mainly in rural or suburban communities where residents are uncertain as to how to locate the best and cheapest supply of groundwater. Because the drilling and development of a well often costs more than a thousand dollars, homeowners are understandably reluctant to gamble on a dry hole and turn to the water dowser for advice.

►► Find out how hydrologists locate groundwater .

What does science say about dowsing?

Case histories and demonstrations of dowsers may seem convincing, but when dowsing is exposed to scientific examination, it presents a very different picture. The natural explanation of "successful" water dowsing is that in many areas underground water is so prevalent close to the land surface that it would be hard to drill a well and not find water. In a region of adequate rainfall and favorable geology, it is difficult not to drill and find water!

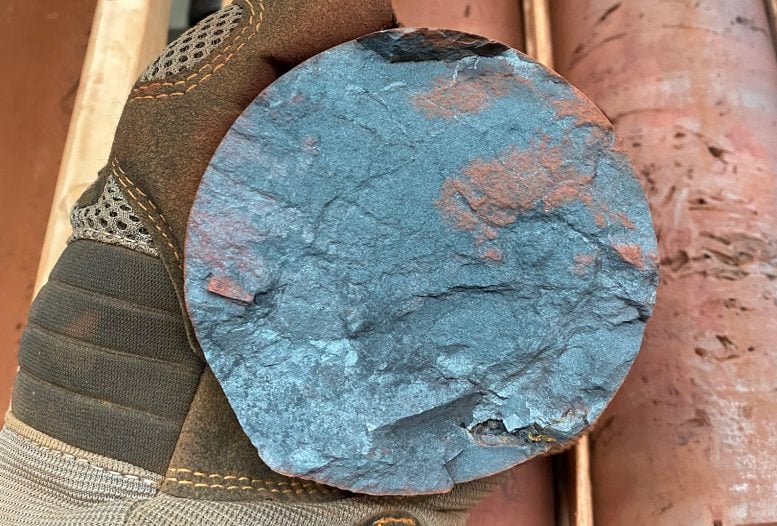

Some water exists under the Earth's surface almost everywhere. This explains why many dowsers appear to be successful. To locate groundwater accurately, however, as to depth, quantity, and quality , several techniques must be used. Hydrologic, geologic, and geophysical knowledge is needed to determine the depths and extent of the different water-bearing strata and the quantity and quality of water found in each. The area must be thoroughly tested and studied to determine these facts.

Sources and more information

- Water Dowsing , USGS General Information publication

- Appraising the Nation's Ground-Water Resources , USGS General Information publication

Below are other science topics associated with groundwater.

Aquifers and Groundwater

Groundwater Quality

Groundwater True/False Quiz

Groundwater: What is Groundwater?

Contamination of Groundwater

Groundwater Wells

Contamination in U.S. Private Wells

Artesian Water and Artesian Wells

Drought and Groundwater Levels

Groundwater Decline and Depletion

Below are publications associated with water dowsing.

Water dowsing

A primer on ground water.

- Subscribe to BBC Science Focus Magazine

- Previous Issues

- Future tech

- Everyday science

- Planet Earth

- Newsletters

© Getty Images

Is there any scientific evidence for dowsing?

There is evidence that dowsing can work but this is neither spooky nor supernatural. It comes down to the dowser, not their tools.

Keiron Allen

Asked by: Keith Barber, Isle of Wight

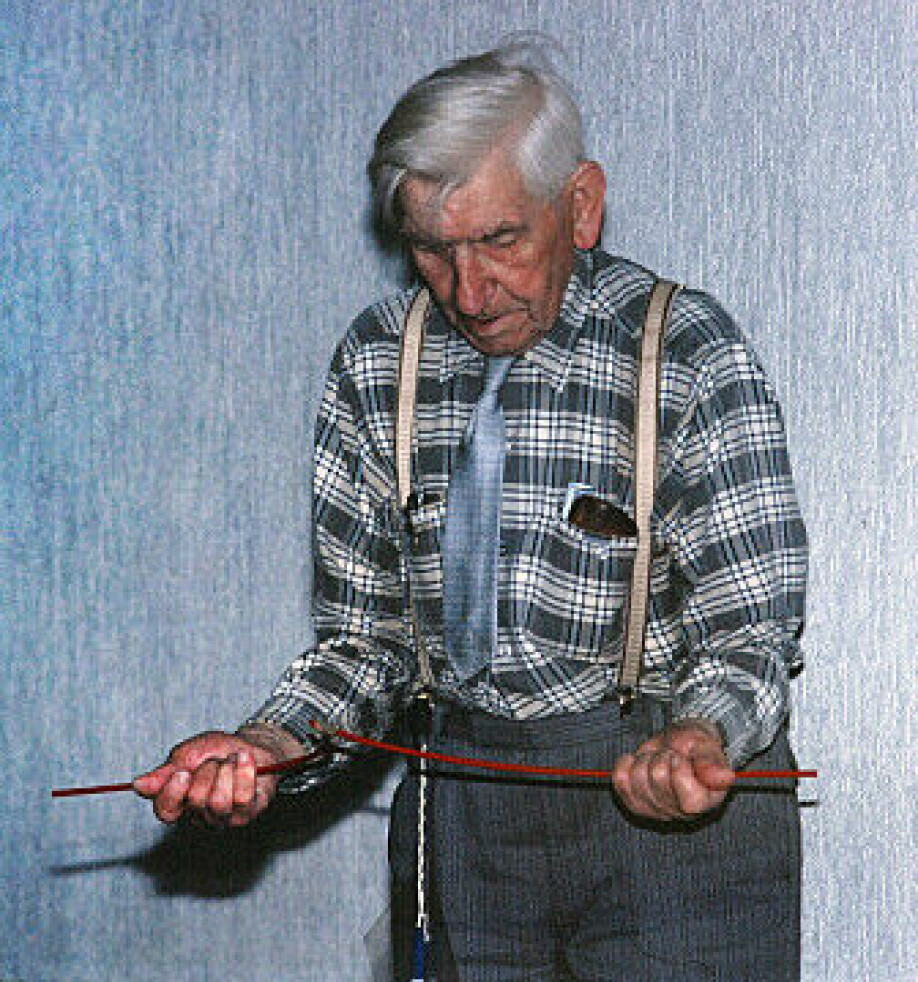

There is but it doesn’t reveal supernatural powers. Dowsing uses tools that amplify small movements. For example, the traditional ‘divining rod’ is a forked twig held in tension so that small hand movements make it tip up or down. Another method uses two lengths of wire bent into an L shape. The dowser holds the short ends, leaving the longs ends finely balanced enough to cross or part with the slightest tilt of the hands.

There is some evidence that dowsers can find water or oil when more traditional methods have failed, which seems miraculous. But experiments show that this works only when the dowser has some unconscious knowledge of where the target is. For example, they might be using clues from vegetation, geography or temperature. They might not realise what they’re doing, and so believe in the supernatural power of the rods. Experiments have been done that eliminate these possibilities, by running water through one of 10 pipes laid underground, or moving the position of water pipes. Under such controlled conditions dowsers do not succeed.

- How is a sponge able to hold so much water?

- What does water taste of?

Subscribe to BBC Focus magazine for fascinating new Q&As every month and follow @sciencefocusQA on Twitter for your daily dose of fun science facts.

Share this article

Food writer

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Code of conduct

- Magazine subscriptions

- Manage preferences

Home » General Geology » Water Dowsing

Dowsing as a Method of Finding Underground Water

Many people believe that dowsing is a valid method for finding groundwater., article by: hobart m. king , phd, rpg.

Figure 1: A person using a forked-stick dowsing rod in a field. The dowser walks through the field with the dowsing rod. When he walks over a location that has the potential of yielding water, the dowsing rod will rotate in his hands and point toward the ground. Many dowsers prefer forked sticks made from willow, peach, or witch hazel wood. Image copyright iStockphoto / Monika Wisniewska.

What Is Dowsing?

"Dowsing," "water witching," "divining," and "doodlebugging" are all names for the practice of locating groundwater by walking the surface of a property while holding a forked stick, a pair of L-shaped rods, a pendulum, or another tool that responds when the person moves above a location that will yield an adequate flow of water to a drilled well (see Figure 1).

People who practice dowsing believe that groundwater moves in subsurface seams, veins, or streams that must be intersected by the drill to produce an adequate flow of water. They believe that locations where this water is present are surrounded by forces that will produce a response in their tools. Forked sticks held in front of a dowser will be deflected toward the ground, a pair of L-shaped rods held lightly in the dowser's hands will cross one another, and a pendulum suspended on a string will deflect from vertical as the dowser moves over a good location.

Why Do Landowners Hire Dowsers?

Drilling a water well can cost thousands of dollars. It is a major investment that many landowners are hesitant to make without professional consultation. They want to be sure that the well is drilled in a location where it will produce water of adequate quantity and quality. This is why many people hire a dowser. They want to drill a successful well, close to their house, where the cost of installing water lines and an electrical conduit will be minimal and where a drilling rig can be easily driven.

Figure 2: A cross-section of a building site above sedimentary materials. The blue line marks the subsurface location of the water table. Wells drilled throughout the area will penetrate the same materials and have a high probability of yielding water.

What Do Hydrogeologists Think of Dowsing?

Although some dowsers have a record of regularly producing good results, the United States Geological Survey reports that most geologists and hydrogeologists do not endorse the practice of dowsing [1]. The National Ground Water Association, in a position statement, "strongly opposes the use of water witches to locate groundwater on the grounds that controlled experimental evidence clearly indicates that the technique is totally without scientific merit" [2].

Figure 3: A drawing from De Re Metallica , by Georgius Agricola, published in 1556. It shows two workers using dowsing rods to locate subsurface ore minerals. Although Agricola used this illustration in his book and reported that the dowsing rod was being used to locate minerals, he rejected the practice and instead recommended trenching [5].

The Nature of Underground Water

Most fresh groundwater occurs in the pore spaces of sedimentary rocks and sediments. It has the ability to flow laterally through these pore spaces and establish a "water table" that is generally horizontal or slightly sloping (see Figure 2). If a landowner wants a well drilled within a hundred or so feet of a building site, almost any location selected will have similar potential for yielding water to a well. Why? Because the same types of rocks are usually present beneath that small area.

Locating and drilling into a good water supply can be difficult in areas underlain by igneous rocks such as granite and basalt . These rocks do not contain pore spaces through which water can flow. Instead, the water must move through very narrow fractures in the rock. A well must intersect enough of these tiny fractures to produce useful amounts of water. It can be very difficult to drill successful wells in some areas underlain by thick cavernous limestone . In these areas, wells that do not intersect a fracture or a cavern might not yield abundant water.

Regarding these igneous and limestone areas, geologists and hydrogeologists believe that there is no scientific basis for a dowser or a dowsing tool to have the ability to select a location where a drilled well will intersect subsurface fractures or small caverns.

| Dowsing is not limited to finding water. Many dowsers believe the same methods can be used to locate oil, mineral deposits, buried utility lines, septic tanks, graves, lost jewelry, and other objects. Some believe that they can hold their tools over a map to locate objects below the ground at locations that are thousands of miles away. Image copyright iStockphoto / Noppadol_Anaporn. |

| Marty Cain, a member of the , has published a YouTube video titled " ." In this video she demonstrates the use of L-rods and a pendulum for finding water. She also explains several methods of dowsing "on-site" and dowsing "at-a-distance" to find sources of pure potable water. |

How Do Hydrogeologists Locate Water?

Most successful water wells are drilled without the advice of a hydrogeologist. Local drilling companies often have the experience of drilling hundreds or thousands of wells in the areas where they operate. They have learned through this experience the parts of their service area where wells with adequate amounts of quality water are usually encountered. They also know areas where locating an adequate water supply can be challenging.

If a hydrogeologist is called to determine a suitable drilling site, he or she will start by examining a geologic map. These maps show the types of rocks that exist below the landowner’s property and their direction of dip. They also provide information about the different types of rock units that exist in the area. Some types of rocks are known to be good producers of water, whereas others will not hold or yield useful water.

The dip of the rock units and the topography of the area can be studied to identify the direction of groundwater flow, potential water recharge areas, springs, and discharge points. The depth of impermeable rock units can sometimes be determined, and these can serve as a lower limit for drilling. All this information allows the hydrogeologist to develop a three-dimensional model of the property that might define locations that are promising or those that should be avoided.

The hydrogeologist will also seek information about previous wells drilled in the local area. Most drillers maintain a file of the types of rocks penetrated and the amount of water produced for each well that they have drilled. This information is very useful in determining the probability of drilling success on a nearby property.

Hydrogeologists often examine aerial photos when siting a well in a challenging area. Aerial photos often reveal linear features that might indicate the presence of fracture zones in the bedrock. These areas often yield abundant water to wells.

Using the information described in the studies above, hydrogeologists base their recommendations on 1) the characteristics of the land; 2) characteristics of rocks beneath the site; 3) results from previous drilling; and, 4) known principles of groundwater movement. They believe that this type of information is more useful for siting a well than how a stick, a wire, or a pendulum responds to an unknown force [3] [4].

| [1] : A general interest publication by the United States Geological Survey; 1988. [2] : A position paper by the National Ground Water Association; originally adopted in 1989; updated in 1992; reformatted in 2009; updated in 2016. [3] : Article on the United States Geological Survey website; last updated June 2018. [4] : A "Water Facts" publication of the California Department of Water Resources; April 1991. [5] : Georgius Agricola, published posthumously in Germany in 1556. |

Conclusions

Many successful wells are drilled without the cost of a dowser or a hydrogeologist. The driller often has a lot of experience in the area being drilled and knows if the rocks in that area typically yield useful quantities of water.

When professional consultations are required or preferred, the landowner must make a decision. Should the project costing thousands of dollars be based upon scientific information about the rocks beneath a site, their water-yielding properties, and known principles of groundwater flow; or, should it be based upon a forked stick and an unexplainable force?

| More General Geology |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

Advertisement Why dowsing makes perfect senseBy Michael Brooks 29 July 2009  No water here, but is there any science? (Image: Colin Gray/Getty) Last week, I went dowsing. Also known as divining, this is the ancient practice of holding twigs or metal rods that are supposed to move in response to hidden objects. It is often used to look for water, and farmers in California have been known to ask dowsers to find ways to irrigate their land . Yet despite many anecdotal reports of success, dowsing has never been shown to work in controlled scientific tests. That’s not to say the dowsing rods don’t move. They do. The scientific explanation for what happens when people dowse is that “ ideomotor movements ” – muscle movements caused by subconscious mental activity – make anything held in the hands move. It looks and feels as if the movements are involuntary. The same phenomenon has been shown to lie behind movements of objects on a Ouija board. Meet the dowserI knew all this when I went to meet John Baker , who is supervising a dowsing workshop at Sissinghurst castle in Kent, UK, tomorrow. What I didn’t realise is just how hard it is to believe the science. Baker specialises in dowsing for hidden archaeological structures. By the time I had finished my couple of hours with him, my scepticism about dowsing was getting shaky. When I arrived, Baker was standing in front of an array of blue flags he had planted in a grassy area in the castle grounds. The flags marked out something his rods had revealed: the outline of a long-forgotten building. Baker held his L-shaped dowsing rods like a pair of six-shooters and walked back and forth across the lines. As he “entered” the building, the rods swung across his body. When he exited, they uncrossed. At this point, I was neither impressed nor surprised. He could see the line of flags, and he knew what he expected to happen. It would only take a small unconscious movement of his hands to make the rods cross, I thought. What would be impressive and surprising is if the rods crossed when I tried it. So I had a few goes. Nothing happened. Baker looked untroubled, but I had begun to feel that I was wasting my time. Baker suggested I try to relax, shake out my shoulders, and maybe visualise something to do with buildings, since that was what I was dowsing for. I did – and it worked. First the rods started to feel “jumpy” in my hands. Though they didn’t cross as I walked forward, they felt as if they might want to. So I tried it again. Eventually, they crossed every time I “entered” the building. They even uncrossed at the other side. I have to confess, however much I might be able to rationalise what was happening, my newfound ability freaked me out a little. So what happened? Baker’s explanation is that by relaxing, and suppressing all my rationalisations, I allowed my brain to tune into a kind of “energy” associated with the buried structure. I think there’s a simpler explanation. Subtle illusionI was frustrated when nothing happened, and stimulated (and amused) when something did. It seems that a part of me wanted it to work. In other words, the atmosphere was the perfect set-up for the ideomotor effect to kick in and move the rods. Scientifically minded sceptics often express deep dismay at the credulousness of people who believe in dowsing , extrasensory perception and other “inexplicable” phenomena. They should not be so harsh. The illusions that make them seem plausible are astonishingly subtle and powerful. It is only human to attribute such observations to something beyond the normal senses . Even if science is your thing, a brief immersion in the world of the “unexplained” can be enough to inject a little doubt. A final confession: I am still slightly disappointed that the scientific explanation stands up so well. I had a great time with Baker at Sissinghurst, and I’m sure tomorrow’s apprentice dowsers will too. We take a perverse pleasure in things that confound our senses, which is why conjuring tricks are delightful and science can seem a killjoy. The physicist Richard Feynman once said that science is a way of trying not to fool yourself. What he didn’t say was just how much fun fooling yourself can be. Michael Brooks is the author of 13 Things That Don’t Make Sense (Profile/Doubleday) Sign up to our weekly newsletterReceive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox! We'll also keep you up to date with New Scientist events and special offers. More from New ScientistExplore the latest news, articles and features  Why is the US military getting ready to launch new spy balloons?Subscriber-only  Generative AI creates playable version of Doom game with no code Does mpox cause lingering symptoms like long covid? Astronomers puzzled by little red galaxies that seem impossibly densePopular articles. Trending New Scientist articles Main navigation

Subscribe to the OSS Weekly Newsletter!Register for the trottier 2024 symposium, dowsing: dowse it work.

Desperate times call for desperate measures, I suppose. Although we live in a world driven by technology, we are always one cataclysm away from retreating to magical notions. Climate change is making droughts worse , which will increase the value of water moving forward. An ancient pseudoscience is poised to make a resurgence in these desperate times. It's been called water witching, radiesthesia, divination or, simply, dowsing. It consists in finding objects, traditionally water, that cannot be detected by our five senses. In a typical write-up, the Boston Globe last fall reported on the increased use of water witching in Massachusetts amid historic droughts . The article sandwiches scientific facts in between anecdotal reports of the “I don’t know how it works but it did” variety. The reader will be left with the impression that if they are ever thirsty for a new source of water on their land, calling upon a dowser would make perfect sense. But divination is not limited to finding water. Its services are offered to find oil, buried objects, lost vessels at sea, missing persons, archaeological artefacts, buried pipes, and food impurities. Basically, move over Saint Anthony: we have ourselves a new patron saint for lost objects. The French priest who, in 1927, gave dowsing the scientific sounding name “radiesthesia” (which means to sense with a rod) claimed he could identify specific microbes in a test tube as accurately as a microbiologist using a microscope . He could also find intact shells buried in the ground during the Great War and somehow tell if they were German, French, or Austrian. Dowsing is traditionally done with the help of a device the movements of which are said to be influenced not by its holder but rather by… something else. This mysterious mover is claimed by different practitioners to be water energy, earth energy, even spirit guides. One of the best-known dowsers in the world, Leroy Bull, says he is guided by a translucent deer, a diaphanous woman, and a Russian agent of the angel of death . The Canadian Society of Dowsers is more circumspect : “I wish I could give you a rational explanation for dowsing. But to date, there is no explanation, scientific or otherwise, as to how dowsing works. There are just theories.” Dowsers use a pendulum, or a Y-shaped rod, or two L-shaped rods that rotate above the handles, and it is the movement of these devices that gets interpreted as “yes” or “no” by the water witcher. Is there water underneath my feet, they might ask? The L-shaped rods, one held in each hand, will cross into an “X” shape if the answer is yes. Is it deeper than a hundred feet? The Y-shaped rod will start pointing to the ground to say yes. Is it deeper than two hundred feet? The pendulum will swing left to right to indicate no. By now, it should be obvious that dowsing is not scientific. Nothing in our current understanding of the laws of physics could allow for such a phenomenon by which the mere presence of something hidden is communicated to a held object, irrespective of the material composition of the artefact and the detector. The closest scientific leap one can make is to the metal detector. Such an apparatus works not because it communicates with alleged spirit guides but because of the electromagnetic properties of metals. Similarly, de-mining efforts can capitalize on the metallic composition of some mines as well as to the smells of the explosives themselves, which is why trained animals such as dogs can also be used in these situations. But can underground water affect the movement of metallic rods? The claims, already dubious, are stretched even further when one learns of map and information dowsing as alternatives to divination in the field. This involves gathering information about a piece of land potentially miles away using a map proxy. And information dowsing? Think Ouija board. You ask any question to your pendulum and it answers back. Don’t believe me? An article once published by the American Society of Dowsers, since deleted , claims you can divine your workout schedule this way. The author writes that they ask their pendulum the following questions: should I exercise for fewer than 90 minutes today? should I work out for fewer than 60 minutes? should I not work out today? The author also reminds us about “dowsing your supplements and dowsing your protein intake for maximum muscle gains.” Why hire a professional when you can rely on the movements of a pendulum? Just a bit of harmless naïveté, one might say, but what if dowsing was promoted in healthcare? It appears that some dowsers, not content with divining for water, can now treat ADHD ! Meanwhile, the Canadian Society of Dowsers seemingly endorses dowsing for healing , drawing connections between divination and pre-scientific notions of qi and prana and the esoteric art of healing known as Reiki. If you’re ready to believe that swinging a pendulum over a map can find a missing person, it’s a tiny sidestep into thinking it might just cure disease. But pulling back from these ridiculous claims for a bit and putting aside the question of just how it would work, does the basic practice of dowsing for water work? This is where we need to visit a barn. “A misuse of public funds”They are often known as the Scheunen experiments . Done over the course of two years in the mid-1980s and to the tune of a quarter of a million American dollars (invested by the German government), the experiment tested 500 dowsers in a barn outside of Munich. Many dowsers believe that what their rods or pendulums are picking up on is a form of radiation, and this radiation could be harmful to our health. Thus, the German government wanted to prove that dowsing was real so that these dowsers might be useful in better understanding this type of radiation. How they went about testing these dowsers is fascinating. It involves a two-story barn. On the ground floor of the barn (or Scheune in German), imagine a 10-metre line on which a wagon can ride back and forth. On the wagon rests a short pipe hooked up on both sides to a hose. From above, this would look like a cross made up of the 10-metre line and the hose. The idea is to move the wagon to a random point along this line and to turn on the water, which will start flowing through the pipe. Of course, if the dowser is on this floor, they will know where the flowing water is, which is why the dowsers were instead taken to the second floor of the barn. On this top floor, the 10-metre line is duplicated. The wagon below is moved to an unknown location along its line. Water starts flowing. On the floor above, the dowser must use their skill to figure out exactly where the wagon is along the line. This set-up was further cheatproofed by being inspected by a professional magician beforehand and by having the position of the wagon in each test be randomly picked by a computer on the spot. These trials were also double-blinded: neither the dowser nor the researcher standing next to them knew where the wagon was during the trial. Even so, there were issues that could have helped dowsers along, such as the possibility that the sound of water turbulence coming from the floor below could have been picked up by the dowser. But this would only have helped the dowsers look more proficient than they were, and since dowsers have often explained their duds by the nearby presence of skeptics, the fact that both the German government investing in the Scheunen trials and the experimenters in charge of them professed a belief in water witching meant that dowsing was primed to prove itself once and for all. But it didn’t. In the much looser early trials, which were not even double blinded, 457 of the 500 dowsers were eliminated since they did no better than chance at finding where the wagon with the running water was. That’s a little over 91% of the test subjects. The remaining 43 dowsers were submitted to a total of 843 single tests inside the barn. They would come back on separate days and try it again, and their predictions as to the location of the water running through the pipe was recorded, as was the actual location of the wagon. When you plot this data , you see that the totality of the guesses made by the lucky 43 over the course of their 843 tests is a random mess. Six dowsers did really well in one series of tests, but when they were brought back for another series, they did no better than chance. Given the number of trials performed and of individuals tested, some of these dowsers were bound to do well in one test by chance alone. They could not, however, reproduce their results. The Americans were smarter than the Germans: their Geological Survey had already concluded in 1917 that further testing of dowsing “… would be a misuse of public funds.” I can already hear the protests from people who have first-hand experience of dowsing successfully finding underground water. The answer is that, in a manner of speaking, dowsing does work. Lessons from the pastThat same U.S. Geological Survey which had declared dowsing a relic of the past a century ago has, on its website , a very prosaic explanation for the success many people have bringing dowsers onto their land to help them find the perfect spot for a well. “In a region of adequate rainfall and favorable geology,” the website states, “it is difficult not to drill and find water!” Therefore, dowsing will help you find water, but so will avoiding the services of a dowser. As to how a dowser’s rods or pendulums behave as if responding to external forces, the answer here is also simple: the ideomotor effect. In short, suggestions and expectations can trigger muscle movements which bypass our will. Thus, while we are responsible for these twitches, it feels as if we are not. It’s the same effect at work when playing Ouija and resting our fingers on its planchette: our desire for answers triggers minuscule muscle contractions in our fingers which are not willed by the executive centre of our brain. Thus moveth the planchette. Thus moveth the rod. We have known about this for two hundred years. Small, driving movements of the body and arm are enough to produce fairly large pendulum motion . You don’t need to be a grifter for your pendulum to find water; self-deception is enough. Belief in dowsing may seem innocuous but it has actually claimed lives. In 2010, BBC Newsnight reported on a number of deaths related to the use of a bomb detector exported out of Great Britain and into countries such as Iraq, Thailand, and Kenya. When one of these so-called bomb-detecting wands was disassembled, it was shown to be an empty plastic casing. No functioning electronics were present; rather, it was a plastic handle with a metallic rod that could swing left to right. It was essentially a dowsing rod, primitive and utterly useless. People died because such an instrument failed to detect roadside bombs. Now, with global warming, dowsing is bound to attract the attention of people trying to survive droughts. The modern skeptical movement cut its teeth on this sort of paranormal thinking, from dowsing to alien visitations to the Satanic panic of the 1980s. These topics may seem quaint by today’s standards, when pseudoscience has become more refined and harder to debunk, but we should not forget the lessons we have learned from these skeptics. The Satanic panic has been transubstantiated into the Save the Children campaign of QAnon. UFO conspiracy theories have infected the brains of extremely popular, so-called public intellectuals . And dowsing? A village in France is training people in water witching, calling it “a growth sector with a bright future,” and both the Canadian city of Ottawa and at least ten UK water companies have been reported as making use of these divination services. Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it… and waste their money in the process. Take-home message: - Dowsing is a debunked technique for searching for underground water or other things using the motion of a held object, like a stick or pendulum - The movements of the held object are actually created by tiny, subconscious movements - Despite the fact that dowsing has been shown time and time again not to work, dowsers continue to be employed, most recently to help find water following climate-change-related droughts @CrackedScience What to read nextIf it sounds too good to be true, it is 28 aug 2024.  Whipping Up Some Science 14 Aug 2024 The Mystery of Milky Seas 9 Aug 2024 Doc of Detox Tries to Rewrite All of Medicine 9 Aug 2024 Will Graphology Become Extinct? 19 Jul 2024 Rasputin, Phrenology, and Dark Allegations: The Madness of Access Consciousness 12 Jul 2024 Department and University InformationOffice for science and society.  The Magic of Dowsing Keeps Holding OnIn West Texas, a century of scientific debunking hasn’t convinced well-drillers to give up old beliefs.  FAR WEST TEXAS —Before Jeff Boyd became the city of Marfa’s public-works director, he had a long career underwater. As a commercial saturation diver, one of the most specialized kinds of divers around, he would spend his days some 400 feet below the surface, breathing a mixture of helium and oxygen, for month-long stretches. Normal air would kill at that depth. It was around that time, when he worked at offshore drill rigs along the Gulf of Mexico and the Bay of Campeche, a job for which he was regularly tasked with locating underwater pipelines, that he discovered he was a water witch. He calls it a gift. Boyd, who has a Hulk Hogan handlebar mustache and liquid-blue eyes, might have grown up in the West Texas desert, but he always felt comfortable in and around water. His office is located beneath the town water tower, an Instagrammable silver beacon with Marfa painted on its side that rises above the hip, touristy town. As public-works director, he is in charge of maintaining and improving the city’s water supply and distribution, and often has to find existing underground pipelines. That’s where his sorcery comes in handy. He even has a wand, of sorts. The handle looks like the notched grip of a ski pole, from which extends a retractable antenna—the kind you might find on an old portable radio—that swivels around and around on a ball hinge. The tool has a fancy name, “the magnetomatic pipe locator,” and is available for purchase for $38.50 online. In reality, it’s just a tricked out version of a divining rod—typically a Y-shaped twig or bent metal wire used to witch for water. Dowsing, or water witching, is a centuries-old practice in which a person walks with a divining rod in hand until it moves due to unseen forces, indicating a source of water underground. For some, the rod bends downward. For others, it makes more of a bobbing motion. Boyd’s magnetomatic pipe locator likes to swing sideways. Read: How evolution’s innovations can help scientists yank water out of the air If this all sounds a little hokey, you’re not the first to think so. The practice of water witching has been debunked time and time again. More surprising is the number of people who credit it—you’d be hard-pressed to find a single well-drilling operation in the Southwest that doesn’t believe in and use water witching. This has been going on long enough that in 1917 the U.S. Department of the Interior, in cooperation with the U.S. Geological Survey, issued an official, book-length report to expose its baseless science. In the report, written by the geologist Arthur J. Ellis, you can hear the raw frustration in Ellis’s prose as he tries, once and for all, to put the matter to bed. “It is difficult to see how for practical purposes the entire matter could be more thoroughly discredited, and it should be obvious to everyone that further tests by the U.S. Geological Survey of this so-called ‘witching’ for water, oil, or other minerals would be a misuse of public funds,” Ellis wrote in his introductory note. Ellis’s report traces the origins of water witching to German miners in the Harz mountains who used divining rods to find veins underground that might contain ore, though others claim the practice is as old as the Scythian and ancient-Persian empires. From the Germans, Ellis wrote, the delusion spread across Europe. Eventually, people would use the rods to locate water and minerals, among other things: grave sites, treasure, even murderers. In the 17th century, a French peasant used a divining rod to accuse a man of murder (he confessed), and later to hunt down other alleged murderers belonging to a persecuted ethno-religious minority, who were executed when found. Ellis’s report, available for 10 cents at the time, was meant to be distributed, and its message disseminated. Yet, more than a century later, the custom of water witching has endured. And almost everyone has a story to tell. One West Texan told me that his brother, a water witch, can’t wear watches, because they always break, thanks to his body’s internal magnetism. Another person told me that she’d been looking for years for a viable well on her land, and at her wits’ end she paid $75 to a water witch, who found one against the odds. Walter Skinner, the owner of Skinner’s Drilling and Well Service in the neighboring town of Alpine, keeps several spare copper wires in his car just in case. He told me that when he was a young man, a water witch laid a hand on his shoulder and passed on his power. From that day forth, Skinner possessed the ability to witch, too. The geologist Jeff Bennett may be the only man in Texas who doesn’t believe in water witching, and he’s well aware of his minority status. He worked as a physical scientist in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas on a variety of government-backed well-drilling projects and never met a driller who didn’t want to “witch it.” Read: California’s underground water war Bennett makes a compelling argument. You can drill a hole just about anywhere, and if you mine deep enough, you will most likely find water; the chances are ever in the dowser’s favor. “The question is: Is it the easiest water? Is it the most water? Is it the best place to drill?” he says. Bennett prefers to rely on regular old science instead, looking at the geological features of the landscape—such as clefts and fault lines—that paint a picture of what might lie beneath. Of water witching, he says, “It’s just guessing. And sometimes they’re good guesses. Sometimes they’re not.” “So, why do you think so many people believe it?” I asked him. “Everyone loves to believe in magic,” he said. In the desert Southwest, there is something magical about water, a resource in short supply that has become scarcer with the rapid depletion of critical sources such as the Rio Grande. The late-summer monsoon season brings a boon of storms that build all day and crash through by late afternoon, saturating the once-arid landscape. The flora and fauna are thankful for it; the cacti bloom impetuously and insects emerge from their underground lairs. For the rest of us, there’s nothing much to do but stand by the screen door and stare in stunned silence. Outside his office, Boyd hands me the magnetomatic pipe locator. He points to two metal caps protruding from the ground—valves off a 10-inch water line that runs beneath the dirt. I walk toward the invisible line, and deliberately slow my pace as I near the valves. The metal antenna slowly keels around when I reach the line, and I can’t tell if I willed it that way. “I couldn’t tell you how it works,” Boyd says, “I just know that it does.” About the AuthorAdvertisement Is Dowsing Real, or Just a Bunch of Hocus-Pocus?

Water witches have been around — and by around, we mean around the world, from Australia and India to Europe and the Americas to many, many other places — for at least five centuries. So just in terms of simple longevity, you have to give it up to the witches . But does that endurance mean dowsing is real? When it comes to water witches — also known as dowsers, diviners, doodlebuggers and various other names — we're faced with two distinct possibilities. One, they're either really good, and have been for a long time, at pulling a fast one on desperate landowners looking for groundwater . Or, two, they actually know what they're doing and they're not pulling a fast one at all. "There's been at least some research testing the dowsers' skill," over the years, says Todd Jarvis , the director of the Institute for Water & Watersheds at Oregon State University, a one-time dowser and member of the American Society of Dowsers , and a practicing hydrogeologist . "And for every study that says there's nothing to it, there's a study that says there's something to it." What's a Water Witch?Science vs. water witching, the purported value of dowsing.  You may have seen the water witch in popular culture. Divining rod in front , wandering arid land until, somewhat magically and often with the hint of help from some otherworldly power, the witch and the wand divine a spot in the dirt where life-giving water, at some depth underground, waits to be liberated. It may sound like some rather hokey hocus-pocus, or something from, say, 500 years ago. But by one estimate, some 60,000 water dowsers are practicing in America today. That's almost 10 times the number of hydrologists, who provide many of the same services as witches, substituting science for dowsing rods. Not all water witches use the forked branch of a tree these days, of course. Many dowsers locate the underground water based on movement of divining rods. Copper rods and pendulums are popular tools of the trade. Smartly contorted wire coat hangers might do the trick. Shovels. Pitchforks. Glass beads. A crowbar. These are simply channels for the power. And not all dowsers go about their groundwater search the same way. Some actually incorporate science into their divining; they look at the topography of the land, the geology . They use maps. They may even have an understanding of local aquifers. They make drawings. Do tests. All rely on some kind of unseen, perhaps divine, intervention to suss out the water . It's an innate ability, a "sense" or "intuition." Sometimes it's simple and quiet. Sometimes it's more theatrical. "You can see some of these folks performing on YouTube," Jarvis says. "Their bodies go into all sorts of contortions." The thing is, water witches are often right. Or close enough to right. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) has long had to field questions about the viability of dowsers and their claims. Yet even the USGS admits that dowsers — water witches, whatever — can find water. How? From the USGS : All this pointing and "feeling" has led to real tension between scientists and dowsers. Some of it, undoubtedly, flows from the fact that the witches indeed have a measure of success in locating underground water, which has led many landowners in search of water to call on dowsers in place of, or in addition to, scientists. The scientists push back.  "To locate ground water accurately ... as to depth, quantity and quality, a number of techniques must be used. Hydrologic, geologic, and geophysical knowledge is needed to determine the depths and extent of the different water-bearing strata and the quantity and quality of water found in each. The area must be thoroughly tested and studied to determine these facts," the USGS says . "Compared to dowsing," Timothy Parker, a California groundwater management consultant and hydrogeologist, told The New York Times , "which is a person with a stick." The USGS and others suggest that the added expense of calling in water witches, though reportedly less than a certified scientist , is simply not worth it. If dowsing is a waste of money, why does it remain so popular? For his part, Jarvis maintains that geologists and other scientists (including hydrologists) are more adept at finding the water. But witches, he says, are more trusted by farmers and other landowners. Jarvis regularly lectures on water witching (a recent webinar conducted for the American Water Resources Association was entitled, " Finding Water the Ol' Timey Way ") and has some firsthand knowledge of it. Early on in his more-than-30-year career, he regularly encountered dowsers — he still does — and, after joining the American Society of Dowsers (ASD), someone found his name on a list of dowsers and, much to his surprise, asked him to come witch a well . So he did. After getting the lay of the land, he picked a spot. It turned out OK. Still, "it didn't make any sense to me as a geologist," he says. Despite the head-butting between Old World and new science, Jarvis now is rather neutral about the idea of dowsing and water witching. He's never surprised when someone finds underground water through nonscientific methods — again, there's a lot of groundwater out there — but he says that the act of striking water, of bringing it to the surface, remains "magical." "I look at it this way," Jarvis says. "They have a 400-year jump on us [dowsers versus hydrologists and hydrogeologists]. To me, it's part of the folklore. It's easy to dismiss it. But if you do, you dismiss that folklore. You dismiss a part of your history." Often drought-stricken California has the largest assemblage of dowsers, according to the ASD, making up at least a half-dozen chapters in the state . Overall, the organization boasts 2,000 active members. Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:  Click here\ to return to USGS publications Water divining (1)

Part of the book series: Encyclopedia of Earth Science ((EESS)) 12 Accesses Water divining (or dowsing), known in the USA as water witching, is a mystical, non scientific technique which exponents claim enables them to locate auspicious places to construct new wells. Dowsing is also used as a wider term referring to the application of these methods to locate any mineral including oil, gold and metal ores, or buried objects such as pipes, and even missing persons or the bodies of murder victims. Water divining is found in some form in all countries. The most commonly used technique in water divining ( Ellis, 1917 ; Todd, 1980 ; Randi, 1991 ) involves holding a forked stick (hazel and willow being the most favored) which is gripped by the two forks with the elbows held to the sides, and with the bottom end of the stick pointing away from the body. The dowser then walks over the local area until the end of the stick is twisted downwards, which the dowser interprets as indicating the presence of groundwater. Another popular method uses two metal rods of copper or... This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access. Access this chapterSubscribe and save.

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout Purchases are for personal use only Institutional subscriptions BibliographyBrassington, R., 1995. Finding Water, 2nd edn. John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, 271 pp. Google Scholar Ellis, A.J., 1917. The divining rod–a history of water witching. US Geological Survey Water Supply Paper 416, 59 pp. Lehr, J.H., 1985. Tolerence of water witching rhetoric is reprehensible. Well Water Journal, June, 8–11. Price, M., 1985. Introducing Groundwater. George Allen & Unwin, London, 195 pp. Randi, J., 1991. James Randi: Psychic Investigator, Boxtree Ltd, London, 159 pp. Todd, D.K., 1980. Groundwater Hydrology, 2nd edn. John Wiley and Sons. New York, 535 pp. Vogt, E.Z. and R. Hyman, 1959. Water Witching USA.University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 248 pp. Cross referencesGroundwater ; Water Divining (2) Download references You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar Editor informationRights and permissions. Reprints and permissions Copyright information© 1998 Kluwer Academic Publishers About this entryCite this entry. Fairbridge, R.W. et al. (1998). Water divining (1). In: Herschy, R.W., Fairbridge, R.W. (eds) Encyclopedia of Hydrology and Water Resources. Encyclopedia of Earth Science. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-4497-7_238 Download citationDOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-4497-7_238 Published : 21 August 2016 Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht Print ISBN : 978-0-412-74060-2 Online ISBN : 978-1-4020-4497-7 eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive Share this entryAnyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Policies and ethics

Dowsing: The Pseudoscience of Water Witching Dowsing is an unexplained process in which people use a forked twig or wire to find missing and hidden objects. Dowsing, also known as divining and doodlebugging, is often used to search for water or missing jewelry, but it is also often employed in other applications including ghost hunting, crop circles and fortunetelling. The dowsing that most people are familiar with is water dowsing, or water witching or rhabdomancy, in which a person holds a Y-shaped branch (or two L-shaped wire rods) and walks around until they feel a pull on the branch, or the wire rods cross, at which point water is allegedly below. Sometimes a pendulum is used held over a map until it swings (or stops swinging) over a spot where the desired object may be found. Dowsing is said to find anything and everything, including missing persons, buried pipes, oil deposits and even archaeological ruins. They got it wrongPart of the reason for dowsing's longevity is its versatility in the New Age and paranormal worlds. According to many books and dowsing experts, the practice has a robust history and its success has been known for centuries. For example in the book "Divining the Future: Prognostication From Astrology to Zoomancy," Eva Shaw writes, "In 1556, 'De Re Metallica,' a book on metallurgy and mining written by George [sic] Agricola, discussed dowsing as an acceptable method of locating rich mineral sources." This reference to 'De Re Metallica' is widely cited among dowsers as proof of its validity, though there are two problems. The first is that the argument is a transparent example of a logical fallacy called the "appeal to tradition" ("it must work because people have done it for centuries"); just because a practice has endured for hundreds of years does not mean it is valid. For nearly 2,000 years, for example, physicians practiced bloodletting, believing that balancing non-existent bodily humors would restore health to sick patients.  Furthermore, it seems that the dowsing advocates didn't actually read the book because it says exactly the opposite of what they claim: Instead of endorsing dowsing, Agricola states that those seeking minerals "should not make use of an enchanted twig, because if he is prudent and skilled in the natural signs, he understands that a forked stick is of no use to him." If dowsing could be proven to work, what could the mechanism be? How could a twig or two metal wires know what the dowser is looking for (water, money, minerals, a lost item, etc.), much less where it could be found? The proposed mechanisms are as varied as the dowsers themselves. Some sources claim that strong psychic energy is radiated by the object and detected by the dowser; others believe that ghosts , spirits or mysterious Earth energies direct the dowser to their targets. Dowsing: No better than chanceSkeptic James Randi in his "Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural," notes that dowsers often cannot agree on even the basics of their profession: "Some instructions tell learners never to try dowsing with rubber footwear, while others insist that it helps immeasurably. Some practitioners say that when divining rods cross, that specifically indicates water; others say that water makes the rods diverge to 180 degrees." Though some people swear by dowsing's effectiveness, dowsers have been subjected to many tests over the years and have performed no better than chance under controlled conditions. It's not surprising that water can often be found with dowsing rods, since if you dig deep enough you'll find water just about anywhere. If missing objects (and even missing people) could be reliably and accurately located using dowsing techniques, it would be a great benefit: If you lose your keys or cell phone, you should be able to just pull out your pendulum and find it; if a person goes missing or is abducted, police should be able to locate them with dowsing rods. Science differs from the New Age and paranormal belief in that it progresses, correcting and building on itself. Technology and medicine are continually advancing and refining. Designs and techniques are improved or abandoned depending on how well they work. By contrast, dowsers have not gotten any more accurate over centuries and millennia of practice. Benjamin Radford is deputy editor of Skeptical Inquirer science magazine and author of six books including Scientific Paranormal Investigation: How to Solve Unexplained Mysteries. His Web site is www.BenjaminRadford.com .

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowGet the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox. 'Yeti hair' found in Himalayas is actually from a horse, BBC series reveals Haunting 'mermaid' mummy from Japan is a gruesome monkey-fish hybrid with 'dragon claws,' new scans reveal 2,200-year old battering ram from epic battle between Rome and Carthage found in Mediterranean Most Popular