Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Economics articles from across Nature Portfolio

Bronze Age Europeans exhibited modern economic behaviour

The foundations of modern economic systems are rooted in the economic behaviour of contemporary humans, and ‘primitive’ societies have been assumed not to fit standard economic theory. But an analysis of metal fragments — effectively, money — shows that modern-style economic behaviour can be identified at least as far back as 3,500 years ago.

Carbon pricing reduces emissions

A meta-analysis of 21 carbon-pricing schemes suggests that the strategy reduces greenhouse-gas emissions. Deciding how high to set prices is the next step — and one that might benefit from the insights of less-aggregated studies in various sectors.

- Thomas Sterner

A mix of reforestation methods offers more cost-effective climate mitigation

The greenhouse gas abatement costs for two forest restoration methods — natural regeneration and plantations — are estimated by integrating observations on the costs of reforestation projects with other biophysical and economic data. This analysis reveals that a mix of reforestation methods offers greater potential to mitigate climate change at low cost than previously estimated.

Latest Research and Reviews

Assessing the Belt and Road Initiative’s environmental footprint: an impact evaluation analysis of African member countries

- Mostafa E. AboElsoud

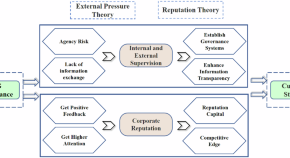

ESG and customer stability: a perspective based on external and internal supervision and reputation mechanisms

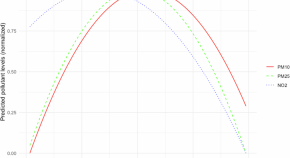

Income, environmental quality and willingness to pay for organic food: a regional analysis in South Korea

- Kwansoo Kim

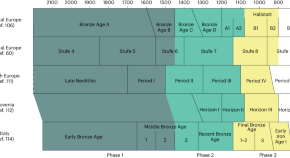

Consumption patterns in prehistoric Europe are consistent with modern economic behaviour

Prehistoric economic behaviour in Europe fits well with modern economic theory, based on a large database of metal objects from across Europe.

- Nicola Ialongo

- Giancarlo Lago

The impact of unconditional cash transfers on enhancing household wellbeing in Pakistan: evidence from a quasi-experimental design

- Abdul Hameed

- Tariq Mahmood Ali

- Muhammad Omar Najam

The great recession, neurotic personality, and subjective sleep quality among patients with mood disorders

- I-Ming Chen

- Hsi-Chung Chen

- Po-Hsiu Kuo

News and Comment

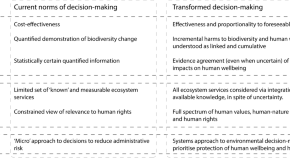

Connecting ecosystem services research and human rights to revamp the application of the precautionary principle

With ecosystem services (ES) vital for human wellbeing 1 , the protection of nature is a human rights matter. We outline how recent advances in international human rights law should inform a revamp of how precaution is applied within environmental decision-making. Critically, precautionary decision-making must evolve to make use of best-available evidence, including novel ES research approaches, to assess ‘foreseeable’ harms to all aspects of human wellbeing that are protected as human rights.

- Holly J. Niner

- Elisa Morgera

- Siân E. Rees

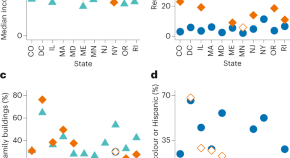

Community solar reaches adopters underserved by rooftop solar

Community solar, a business model where multiple customers buy output from shared solar systems, has expanded solar access among multifamily housing occupants, renters, and low-income households. Policies to enable community solar could be expanded and benefits of access augmented through targeted measures to support community solar adoption in underserved communities.

- Eric O’Shaughnessy

- Galen Barbose

- Jenny Sumner

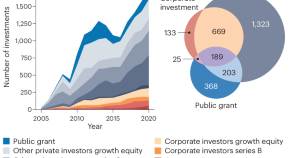

Rapid rise in corporate climate-tech investments complements support from public grants

Investment in climate and energy (climate-tech) startups is growing in the US and worldwide, with public grants backing high-risk sectors and publicly funded startups exiting at higher rates with corporate investment. Public policies to incentivize corporate investment in these startups can therefore be an important, yet sometimes underestimated, part of meeting net-zero goals.

- Kathleen M. Kennedy

- Morgan R. Edwards

- Kavita Surana

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Take a look at the latest research from MIT Economics faculty, including published work and newly-released working papers.

Working Papers

Can deficits finance themselves, intergenerational impacts of secondary education: experimental evidence from ghana.

Risky Business: Why Insurance Markets Fail and What To Do About It

Cooking to Save Your Life

Published papers, a task-based approach to inequality, automation and the workforce: a firm-level view from the 2019 annual business survey.

Labs and Centers

Research news.

Through econometrics, Isaiah Andrews is making research more robust

Michael D Whinston receives the 2024 Jean-Jacques Laffont Prize

An official website of the United States government

U.S. Economy at a Glance

Perspective from the bea accounts.

BEA produces some of the most closely watched economic statistics that influence decisions of government officials, business people, and individuals. These statistics provide a comprehensive, up-to-date picture of the U.S. economy. The data on this page are drawn from featured BEA economic accounts.

National Economic Accounts

Gross domestic product, second quarter 2024 (advance estimate).

Real gross domestic product (GDP) increased at an annual rate of 2.8 percent in the second quarter of 2024, according to the "advance" estimate. In the first quarter, real GDP increased 1.4 percent. The increase in the second quarter primarily reflected increases in consumer spending, inventory investment, and business investment. Imports, which are a subtraction in the calculation of GDP, increased.

- Current release: July 25, 2024

- Next release: August 29, 2024

Gross Domestic Product, Second Quarter 2024 (Advance Estimate) - HP CHART

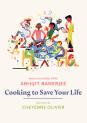

Personal Income and Outlays, June 2024

Personal income increased $50.4 billion (0.2 percent at a monthly rate) in June. Disposable personal income (DPI)—personal income less personal current taxes—increased $37.7 billion (0.2 percent). Personal outlays—the sum of personal consumption expenditures (PCE), personal interest payments, and personal current transfer payments—increased $59.3 billion (0.3 percent) and consumer spending increased $57.6 billion (0.3 percent). Personal saving was $703.0 billion and the personal saving rate—personal saving as a percentage of disposable personal income—was 3.4 percent in June.

- Current release: July 26, 2024

- Next release: August 30, 2024

Disposable Personal Income, Outlays, and Savings, June '24

International Economic Accounts

U.s. international transactions, 1st quarter 2024 and annual update.

The U.S. current-account deficit widened by $15.9 billion, or 7.2 percent, to $237.6 billion in the first quarter of 2024, according to statistics released today by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. The revised fourth-quarter deficit was $221.8 billion. The first-quarter deficit was 3.4 percent of current-dollar gross domestic product, up from 3.2 percent in the fourth quarter.

- Current Release: June 20, 2024

- Next Release: September 19, 2024

U.S. International Transactions, 1st Quarter 2024 and Annual Update CHART 1

U.S. International Investment Position, 1st Quarter 2024 and Annual Update

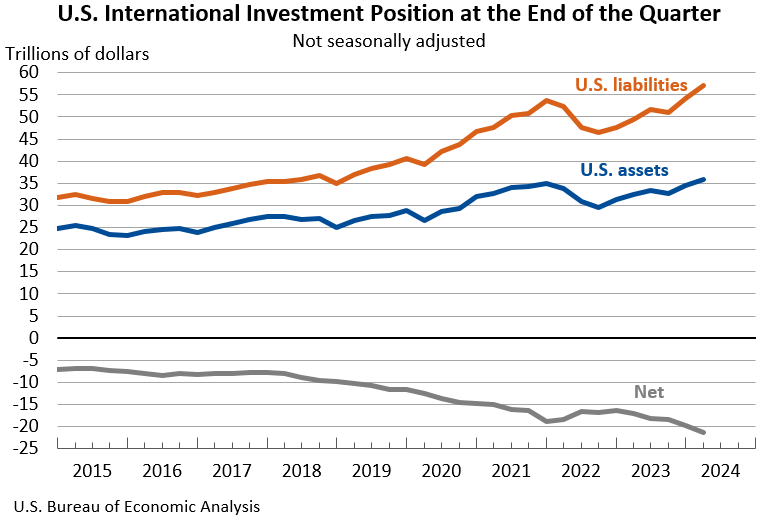

The U.S. net international investment position, the difference between U.S. residents’ foreign financial assets and liabilities, was -$21.28 trillion at the end of the first quarter of 2024, according to statistics released today by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Assets totaled $35.78 trillion, and liabilities were $57.06 trillion. At the end of the fourth quarter of 2023, the net investment position was -$19.85 trillion (revised).

- Current Release: June 26, 2024

- Next Release: September 25, 2024

U.S. International Investment Position, 1st Quarter '24 and Annual Update CHART

U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services, May 2024

The U.S. goods and services trade deficit increased in May 2024 according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis and the U.S. Census Bureau. The deficit increased from $74.5 billion in April (revised) to $75.1 billion in May, as exports decreased more than imports. The goods deficit increased $0.9 billion in May to $100.2 billion. The services surplus increased $0.3 billion in May to $25.1 billion.

- Current Release: July 3, 2024

- Next release: August 6, 2024

Goods and Services Trade Deficit, May '24

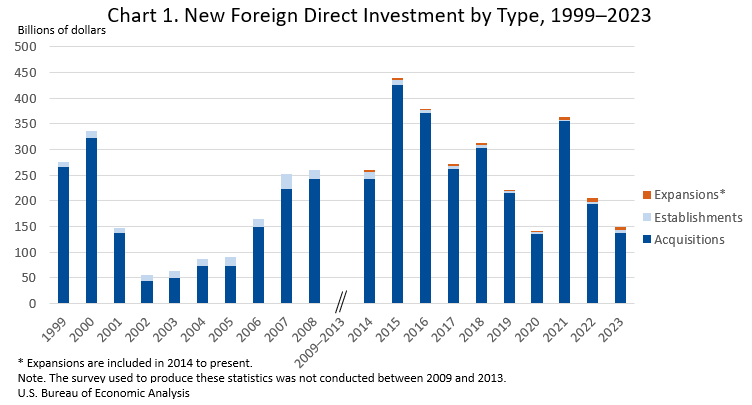

New Foreign Direct Investment in the United States, 2023

Expenditures by foreign direct investors to acquire, establish, or expand U.S. businesses totaled $148.8 billion in 2023 (chart 1), according to preliminary statistics released today by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Expenditures decreased $57.4 billion, or 28 percent, from $206.2 billion (revised) in 2022 and were below the annual average of $265.6 billion for 2014–2022. As in previous years, acquisitions of existing U.S. businesses accounted for most of the expenditures.

- Current release: July 12, 2024

- Next release: July 2025

New Foreign Direct Investment in the United States, '23 Chart

Regional Economic Accounts

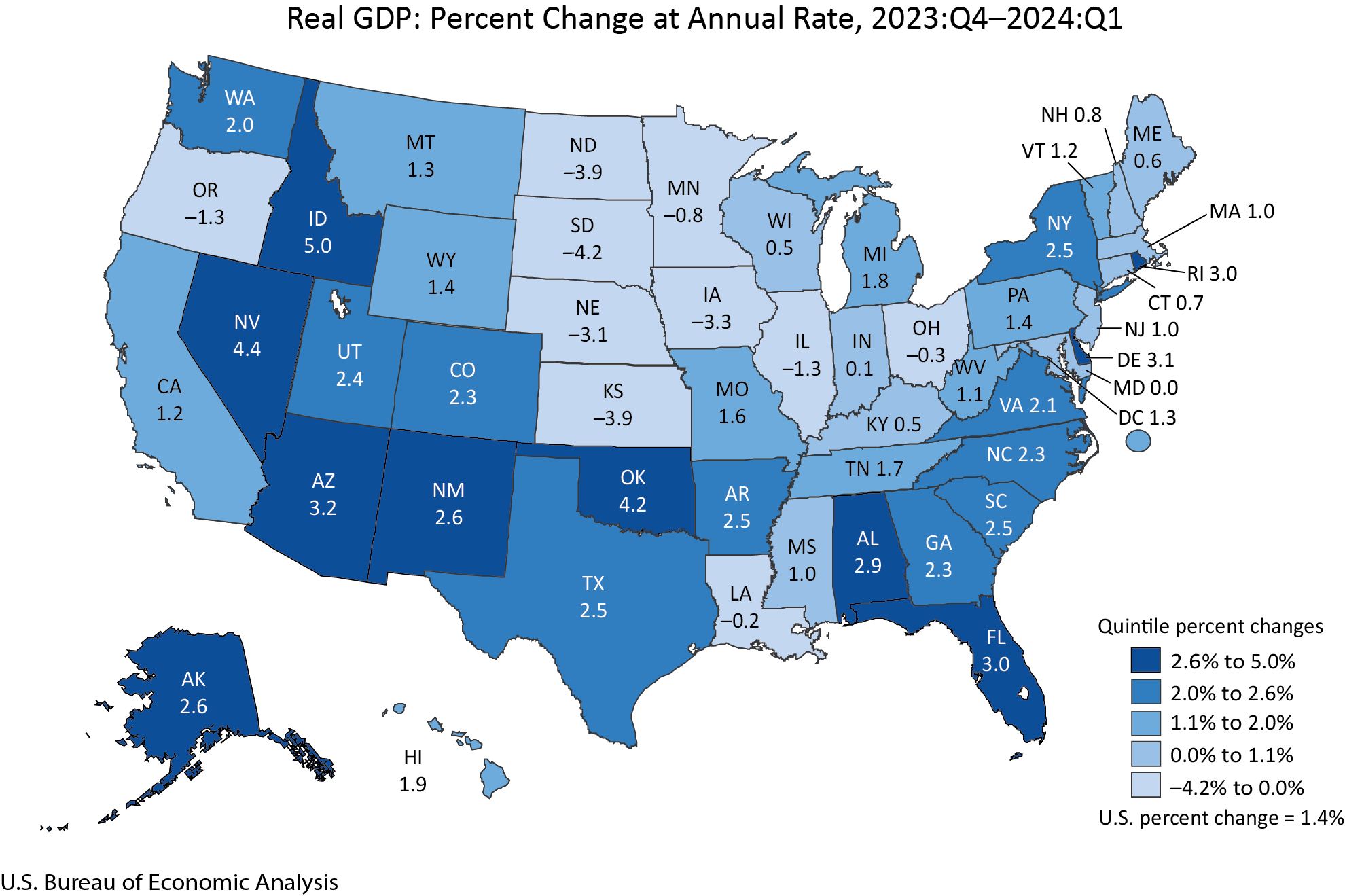

Gross domestic product by state and personal income by state, 1st quarter 2024.

Real gross domestic product (GDP) increased in 39 states and the District of Columbia in the first quarter of 2024, with the percent change ranging from 5.0 percent at an annual rate in Idaho to –4.2 percent in South Dakota.

- Current Release: June 28, 2024

- Next Release: September 27, 2024

Gross Domestic Product by State and Personal Income by State, 1st Quarter '24 CHART

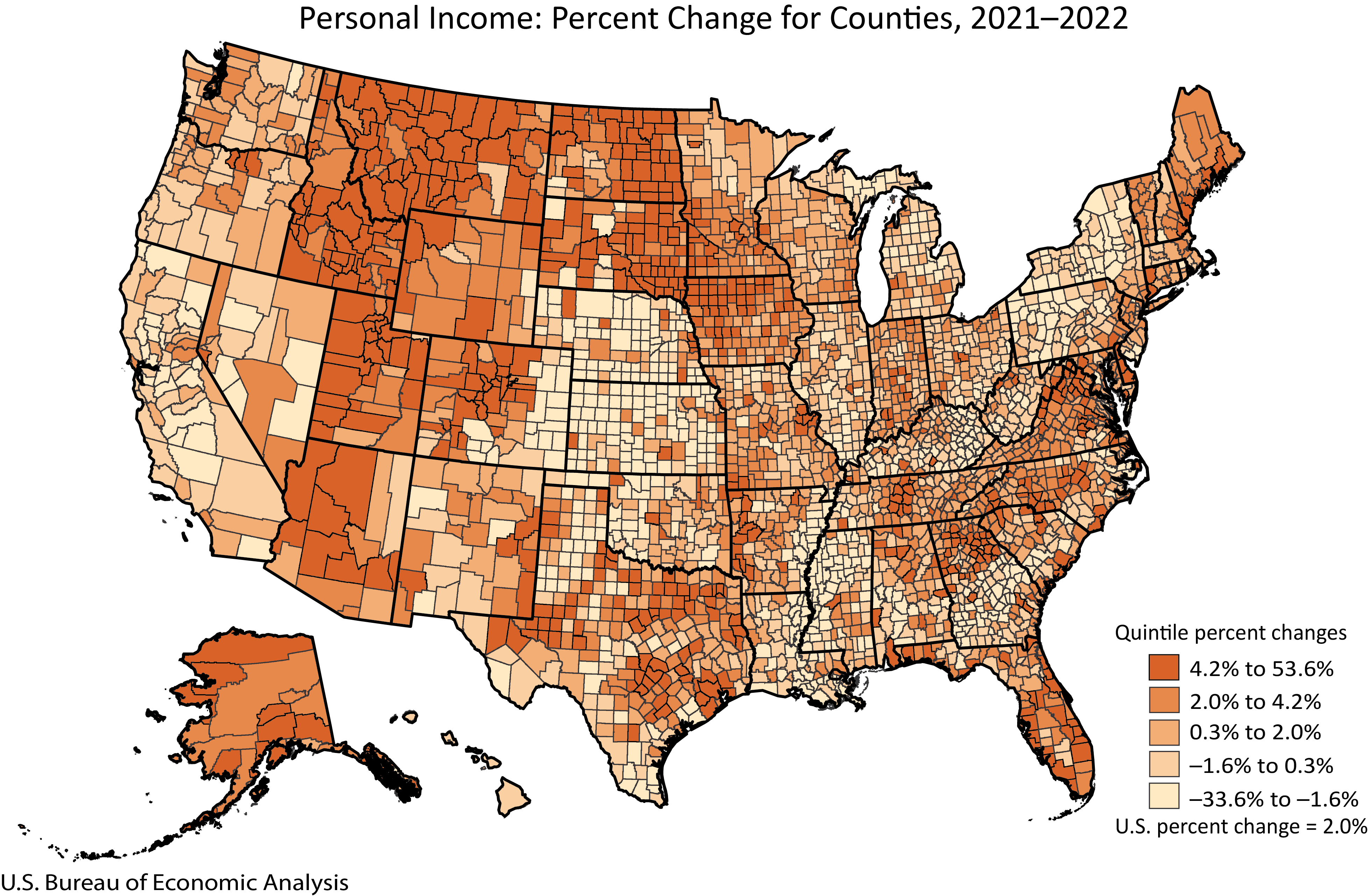

Personal Income by County and Metropolitan Area, 2022

In 2022, personal income, in current dollars, increased in 1,964 counties, decreased in 1,107, and was unchanged in 43. Personal income increased 2.1 percent in the metropolitan portion of the United States and 1.3 percent in the nonmetropolitan portion.

- Current Release: November 16, 2023

- Next Release: November 14, 2024

Personal Income by County and Metropolitan Area, 2022 CHART

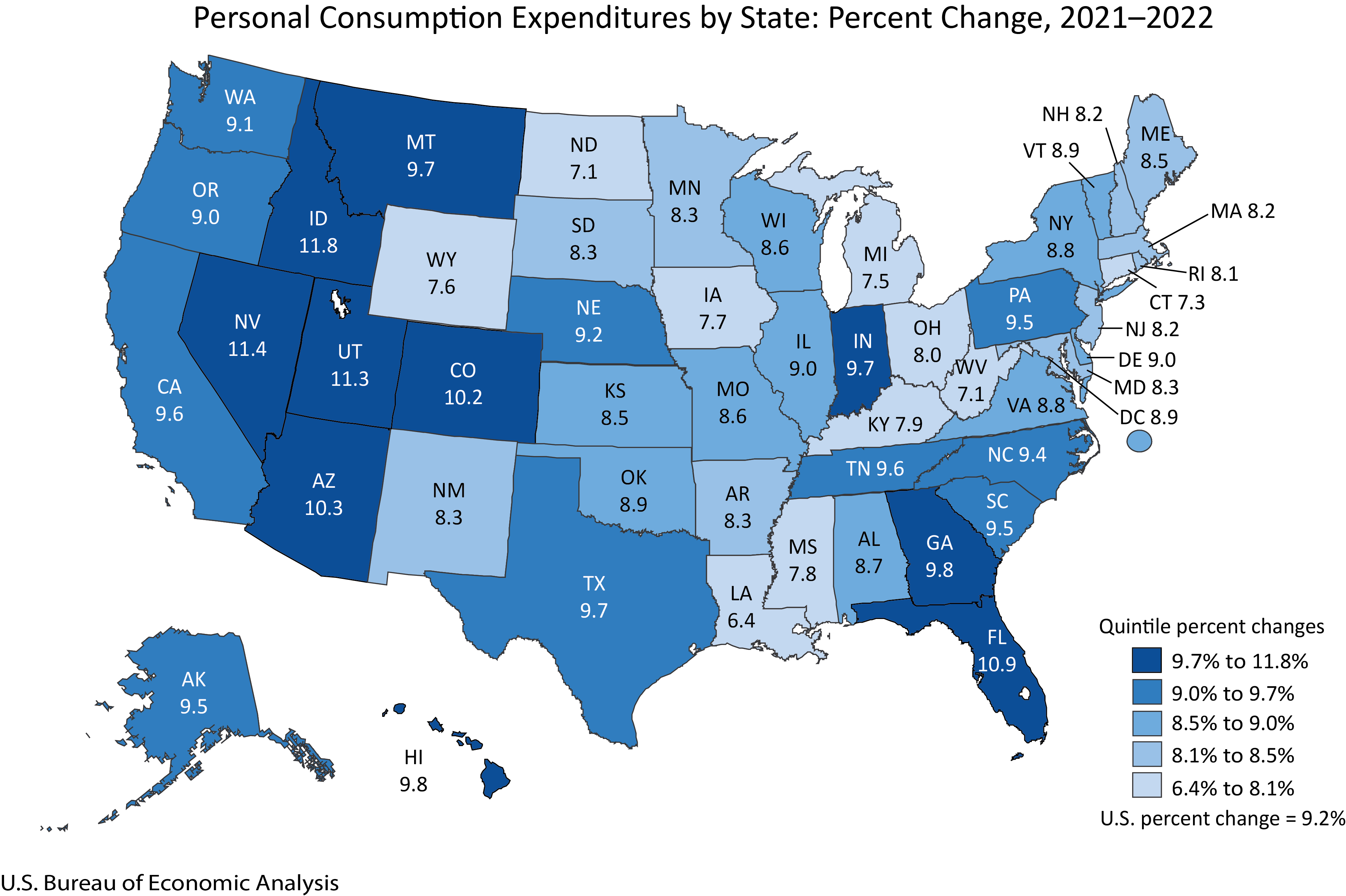

Personal Consumption Expenditures by State, 2022

Nationally, personal consumption expenditures (PCE), in current dollars, increased 9.2 percent in 2022 after increasing 12.9 percent in 2021. PCE increased in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, with the percent change ranging from 11.8 percent in Idaho to 6.4 percent in Louisiana.

- Current Release: October 4, 2023

- Next release: October 3, 2024

Personal Consumption Expenditures by State: Percent Change, '21-'22

- Federal Reserve Facebook Page

- Federal Reserve Instagram Page

- Federal Reserve YouTube Page

- Federal Reserve Flickr Page

- Federal Reserve LinkedIn Page

- Federal Reserve Threads Page

- Federal Reserve Twitter Page

- Subscribe to RSS

- Subscribe to Email

- Recent Postings

- Publications

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve, the central bank of the United States, provides the nation with a safe, flexible, and stable monetary and financial system.

Economic Research

Finance and economics discussion series.

Benjamin Knox and Jakob Ahm Sørensen

David Bowman , Yesol Huh , and Sebastian Infante

Bradley Katcher, Geng Li , Alvaro Mezza , and Steve Ramos

International Finance Discussion Papers

Baris Kaymak and Immo Schott

Christoph E. Boehm and T. Niklas Kroner

Martin Bodenstein , Pablo Cuba-Borda , Nils Goernemann , Ignacio Presno

Jessica N. Flagg and Simona M. Hannon

Danilo Cascaldi-Garcia and Hyunseung Oh

Data, Models and Tools

FRB/US Model :

A large-scale estimated general equilibrium model of the U.S. economy for FRB/US Model

Yield Curve Models and Data :

Models of daily yield curves, and a dynamic term structure model of Treasury yields

Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) :

Information on families' balance sheets, pensions, income, and demographic characteristics

Economic Research Data:

View selected research data from the Federal Reserve Board's working papers and notes series.

Estimated Dynamic Optimization (EDO) Model :

A medium-scale New Keynesian dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model of the U.S. economy.

Research Resources

- Staff Publications and Working Papers 2022-2023 (PDF)

- Research Support

- Seminars and Workshops

- Visiting Scholars

- Alumni List

- Other Research

- Federal Reserve Board Research Data Center

Meet the Researchers

By Division

Consumer and Community Affairs Financial Stability International Finance Monetary Affairs Office of Board Members Research and Statistics Reserve Bank Operations and Payment Systems Supervision and Regulation

By Field of Interest

Finance International Economics Macroeconomics Mathematical and Quantitative Methods Microeconomics

All Researchers

- Overview of economist positions

- Frequently asked questions

- Overview of research assistant positions

Disclaimer: The economic research that is linked from this page represents the views of the authors and does not indicate concurrence either by other members of the Board's staff or by the Board of Governors. The economic research and their conclusions are often preliminary and are circulated to stimulate discussion and critical comment.

The Board values having a staff that conducts research on a wide range of economic topics and that explores a diverse array of perspectives on those topics. The resulting conversations in academia, the economic policy community, and the broader public are important to sharpening our collective thinking.

Advertisement

Gender inequality as a barrier to economic growth: a review of the theoretical literature

- Open access

- Published: 15 January 2021

- Volume 19 , pages 581–614, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Manuel Santos Silva 1 &

- Stephan Klasen 1

57k Accesses

31 Citations

27 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In this article, we survey the theoretical literature investigating the role of gender inequality in economic development. The vast majority of theories reviewed argue that gender inequality is a barrier to development, particularly over the long run. Among the many plausible mechanisms through which inequality between men and women affects the aggregate economy, the role of women for fertility decisions and human capital investments is particularly emphasized in the literature. Yet, we believe the body of theories could be expanded in several directions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Gender Inequality and Growth in Europe

The effect of gender inequality on economic development: case of african countries.

The Feminization U

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Theories of long-run economic development have increasingly relied on two central forces: population growth and human capital accumulation. Both forces depend on decisions made primarily within households: population growth is partially determined by households’ fertility choices (e.g., Becker & Barro 1988 ), while human capital accumulation is partially dependent on parental investments in child education and health (e.g., Lucas 1988 ).

In an earlier survey of the literature linking family decisions to economic growth, Grimm ( 2003 ) laments that “[m]ost models ignore the two-sex issue. Parents are modeled as a fictive asexual human being” (p. 154). Footnote 1 Since then, however, economists are increasingly recognizing that gender plays a fundamental role in how households reproduce and care for their children. As a result, many models of economic growth are now populated with men and women. The “fictive asexual human being” is a dying species. In this article, we survey this rich new landscape in theoretical macroeconomics, reviewing, in particular, micro-founded theories where gender inequality affects economic development.

For the purpose of this survey, gender inequality is defined as any exogenously imposed difference between male and female economic agents that, by shaping their behavior, has implications for aggregate economic growth. In practice, gender inequality is typically modeled as differences between men and women in endowments, constraints, or preferences.

Many articles review the literature on gender inequality and economic growth. Footnote 2 Typically, both the theoretical and empirical literature are discussed, but, in almost all cases, the vast empirical literature receives most of the attention. In addition, some of the surveys examine both sides of the two-way relationship between gender inequality and economic growth: gender equality as a cause of economic growth and economic growth as a cause of gender equality. As a result, most surveys end up only scratching the surface of each of these distinct strands of literature.

There is, by now, a large and insightful body of micro-founded theories exploring how gender equality affects economic growth. In our view, these theories merit a separate review. Moreover, they have not received sufficient attention in empirical work, which has largely developed independently (see also Cuberes & Teignier 2014 ). By reviewing the theoretical literature, we hope to motivate empirical researchers in finding new ways of putting these theories to test. In doing so, our work complements several existing surveys. Doepke & Tertilt ( 2016 ) review the theoretical literature that incorporates families in macroeconomic models, without focusing exclusively on models that include gender inequality, as we do. Greenwood, Guner and Vandenbroucke ( 2017 ), in turn, review the theoretical literature from the opposite direction; they study how macroeconomic models can explain changes in family outcomes. Doepke, Tertilt and Voena ( 2012 ) survey the political economy of women’s rights, but without focusing explicitly on their impact on economic development.

To be precise, the scope of this survey consists of micro-founded macroeconomic models where gender inequality (in endowments, constraints, preferences) affects economic growth—either by influencing the economy’s growth rate or shaping the transition paths between multiple income equilibria. As a result, this survey does not cover several upstream fields of partial-equilibrium micro models, where gender inequality affects several intermediate growth-related outcomes, such as labor supply, education, health. Additionally, by focusing on micro-founded macro models, we do not review studies in heterodox macroeconomics, including the feminist economics tradition using structuralist, demand-driven models. For recent overviews of this literature, see Kabeer ( 2016 ) and Seguino ( 2013 , 2020 ). Overall, we find very little dialogue between the neoclassical and feminist heterodox literatures. In this review, we will show that actually these two traditions have several points of contact and reach similar conclusions in many areas, albeit following distinct intellectual routes.

Although the incorporation of gender in macroeconomic models of economic growth is a recent development, the main gendered ingredients of those models are not new. They were developed in at least two strands of literature. First, since the 1960s, “new home economics” has applied the analytical toolbox of rational choice theory to decisions being made within the boundaries of the family (see, e.g., Becker 1960 , 1981 ). Footnote 3 A second literature strand, mostly based on empirical work at the micro level in developing countries, described clear patterns of gender-specific behavior within households that differed across regions of the developing world (see, e.g., Boserup 1970 ). Footnote 4 As we shall see, most of the (micro-founded) macroeconomic models reviewed in this article use several analytical mechanisms from "new home economics”; these mechanisms can typically rationalize several of the gender-specific regularities observed in early studies of developing countries. The growth theorist is then left to explore the aggregate implications for economic development.

The first models we present focus on gender discrimination in (or on access to) the labor market as a distortionary tax on talent. If talent is randomly distributed in the population, men and women are imperfect substitutes in aggregate production, and, as a consequence, gender inequality (as long as determined by non-market processes) will misallocate talent and lower incentives for female human capital formation. These theories do not rely on typical household functions such as reproduction and childrearing. Therefore, in these models, individuals are not organized into households. We review this literature in section 2 .

From there, we proceed to theories where the household is the unit of analysis. In sections 3 and 4 , we cover models that take the household as given and avoid marriage markets or other household formation institutions. This is a world where marriage (or cohabitation) is universal, consensual, and monogamous; families are nuclear, and spouses are matched randomly. The first articles in this tradition model the household as a unitary entity with joint preferences and interests, and with an efficient and centralized decision making process. Footnote 5 These theories posit how men and women specialize into different activities and how parents interact with their children. Section 3 reviews these theories. Over time, the literature has incorporated intra-household dynamics. Now, family members are allowed to have different preferences and interests; they bargain, either cooperatively or not, over family decisions. Now, the theorist recognizes power asymmetries between family members and analyzes how spouses bargain over decisions. Footnote 6 These articles are surveyed in section 4 .

The final set of articles we survey take into account how households are formed. These theories show how gender inequality can influence economic growth and long-run development through marriage market institutions and family formation patterns. Among other topics, this literature has studied ages at first marriage, relative supply of potential partners, monogamy and polygyny, arranged and consensual marriages, and divorce risk. Upon marriage, these models assume different bargaining processes between the spouses, or even unitary households, but they all recognize, in one way or another, that marriage, labor supply, consumption, and investment decisions are interdependent. We review these theories in section 5 .

Table 1 offers a schematic overview of the literature. To improve readability, the table only includes studies that we review in detail, with articles listed in order of appearance in the text. The table also abstracts from models’ extensions and sensitivity checks, and focuses exclusively on the causal pathways leading from gender inequality to economic growth.

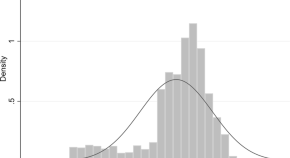

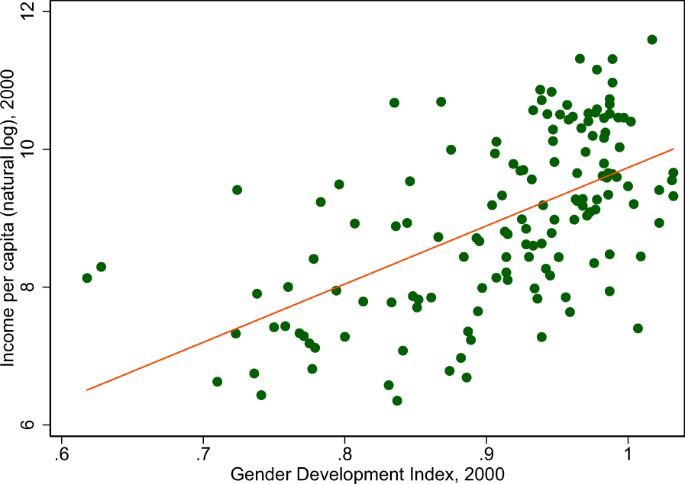

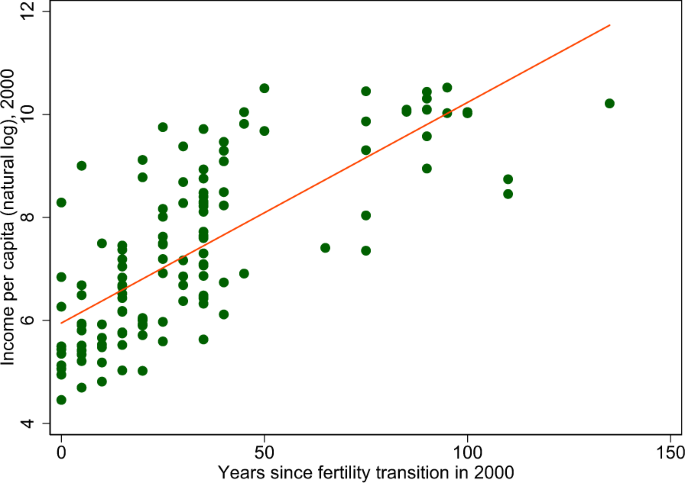

The vast majority of theories reviewed argue that gender inequality is a barrier to economic development, particularly over the long run. The focus on long-run supply-side models reflects a recent effort by growth theorists to incorporate two stylized facts of economic development in the last two centuries: (i) a strong positive association between gender equality and income per capita (Fig. 1 ), and (ii) a strong association between the timing of the fertility transition and income per capita (Fig. 2 ). Footnote 7 Models that endogenize a fertility transition are able to generate a transition from a Malthusian regime of stagnation to a modern regime of sustained economic growth, thus replicating the development experience of human societies in the very long run (e.g., Galor 2005a , b ; Guinnane 2011 ). In contrast, demand-driven models in the heterodox and feminist traditions have often argued that gender wage discrimination and gendered sectoral and occupational segregation can be conducive to economic growth in semi-industrialized export-oriented economies. Footnote 8 In these settings—that fit well the experience of East and Southeast Asian economies—gender wage discrimination in female-intensive export industries reduces production costs and boosts exports, profits, and investment (Blecker & Seguino 2002 ; Seguino 2010 ).

Income level and gender equality. Income is the natural log of per capita GDP (PPP-adjusted). The Gender Development Index is the ratio of gender-specific Human Development Indexes: female HDI/male HDI. Data are for the year 2000. Sources: UNDP

Income level and timing of the fertility transition. Income is the natural log of per capita GDP (PPP-adjusted) in 2000. Years since fertility transition are the number of years between 2000 and the onset year of the fertility decline. See Reher ( 2004 ) for details. Sources: UNDP and Reher ( 2004 )

In most long-run, supply-side models reviewed here, irrespectively of the underlying source of gender differences (e.g., biology, socialization, discrimination), the opportunity cost of women’s time in foregone labor market earnings is lower than that of men. This gender gap in the value of time affects economic growth through two main mechanisms. First, when the labor market value of women’s time is relatively low, women will be in charge of childrearing and domestic work in the family. A low value of female time means that children are cheap. Fertility will be high, and economic growth will be low, both because population growth has a direct negative impact on long-run economic performance and because human capital accumulates at a slower pace (through the quantity-quality trade-off). Second, if parents expect relatively low returns to female education, due to women specializing in domestic activities, they will invest relatively less in the education of girls. In the words of Harriet Martineau, one of the first to describe this mechanism, “as women have none of the objects in life for which an enlarged education is considered requisite, the education is not given” (Martineau 1837 , p. 107). In the long run, lower human capital investments (on girls) lead to slower economic development.

Overall, gender inequality can be conceptualized as a source of inefficiency, to the extent that it results in the misallocation of productive factors, such as talent or labor, and as a source of negative externalities, when it leads to higher fertility, skewed sex ratios, or lower human capital accumulation.

We conclude, in section 6 , by examining the limitations of the current literature and pointing ways forward. Among them, we suggest deeper investigations of the role of (endogenous) technological change on gender inequality, as well as greater attention to the role and interests of men in affecting gender inequality and its impact on growth.

2 Gender discrimination and misallocation of talent

Perhaps the single most intuitive argument for why gender discrimination leads to aggregate inefficiency and hampers economic growth concerns the allocation of talent. Assume that talent is randomly distributed in the population. Then, an economy that curbs women’s access to education, market employment, or certain occupations draws talent from a smaller pool than an economy without such restrictions. Gender inequality can thus be viewed as a distortionary tax on talent. Indeed, occupational choice models with heterogeneous talent (as in Roy 1951 ) show that exogenous barriers to women’s participation in the labor market or access to certain occupations reduce aggregate productivity and per capita output (Cuberes & Teignier 2016 , 2017 ; Esteve-Volart 2009 ; Hsieh, Hurst, Jones and Klenow 2019 ).

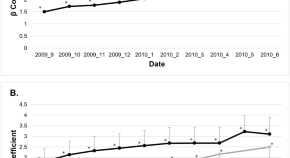

Hsieh et al. ( 2019 ) represent the US economy with a model where individuals sort into occupations based on innate ability. Footnote 9 Gender and race identity, however, are a source of discrimination, with three forces preventing women and black men from choosing the occupations best fitting their comparative advantage. First, these groups face labor market discrimination, which is modeled as a tax on wages and can vary by occupation. Second, there is discrimination in human capital formation, with the costs of occupation-specific human capital being higher for certain groups. This cost penalty is a composite term encompassing discrimination or quality differentials in private or public inputs into children’s human capital. The third force are group-specific social norms that generate utility premia or penalties across occupations. Footnote 10

Assuming that the distribution of innate ability across race and gender is constant over time, Hsieh et al. ( 2019 ) investigate and quantify how declines in labor market discrimination, barriers to human capital formation, and changing social norms affect aggregate output and productivity in the United States, between 1960 and 2010. Over that period, their general equilibrium model suggests that around 40 percent of growth in per capita GDP and 90 percent of growth in labor force participation can be attributed to reductions in the misallocation of talent across occupations. Declining in barriers to human capital formation account for most of these effects, followed by declining labor market discrimination. Changing social norms, on the other hand, explain only a residual share of aggregate changes.

Two main mechanisms drive these results. First, falling discrimination improves efficiency through a better match between individual ability and occupation. Second, because discrimination is higher in high-skill occupations, when discrimination decreases, high-ability women and black men invest more in human capital and supply more labor to the market. Overall, better allocation of talent, rising labor supply, and faster human capital accumulation raise aggregate growth and productivity.

Other occupational choice models assuming gender inequality in access to the labor market or certain occupations reach similar conclusions. In addition to the mechanisms in Hsieh et al. ( 2019 ), barriers to women’s work in managerial or entrepreneurial occupations reduce average talent in these positions, resulting in aggregate losses in innovation, technology adoption, and productivity (Cuberes & Teignier 2016 , 2017 ; Esteve-Volart 2009 ). The argument can be readily applied to talent misallocation across sectors (Lee 2020 ). In Lee’s model, female workers face discrimination in the non-agricultural sector. As a result, talented women end up sorting into ill-suited agricultural activities. This distortion reduces aggregate productivity in agriculture. Footnote 11

To sum up, when talent is randomly distributed in the population, barriers to women’s education, employment, or occupational choice effectively reduce the pool of talent in the economy. According to these models, dismantling these gendered barriers can have an immediate positive effect on economic growth.

3 Unitary households: parents and children

In this section, we review models built upon unitary households. A unitary household maximizes a joint utility function subject to pooled household resources. Intra-household decision making is assumed away; the household is effectively a black-box. In this class of models, gender inequality stems from a variety of sources. It is rooted in differences in physical strength (Galor & Weil 1996 ; Hiller 2014 ; Kimura & Yasui 2010 ) or health (Bloom et al. 2015 ); it is embedded in social norms (Hiller 2014 ; Lagerlöf 2003 ), labor market discrimination (Cavalcanti & Tavares 2016 ), or son preference (Zhang, Zhang and Li 1999 ). In all these models, gender inequality is a barrier to long-run economic development.

Galor & Weil ( 1996 ) model an economy with three factors of production: capital, physical labor (“brawn”), and mental labor (“brain”). Men and women are equally endowed with brains, but men have more brawn. In economies starting with very low levels of capital per worker, women fully specialize in childrearing because their opportunity cost in terms of foregone market earnings is lower than men’s. Over time, the stock of capital per worker builds up due to exogenous technological progress. The degree of complementarity between capital and mental labor is higher than that between capital and physical labor; as the economy accumulates capital per worker, the returns to brain rise relative to the returns to brawn. As a result, the relative wages of women rise, increasing the opportunity cost of childrearing. This negative substitution effect dominates the positive income effect on the demand for children and fertility falls. Footnote 12 As fertility falls, capital per worker accumulates faster creating a positive feedback loop that generates a fertility transition and kick starts a process of sustained economic growth.

The model has multiple stable equilibria. An economy starting from a low level of capital per worker is caught in a Malthusian poverty trap of high fertility, low income per capita, and low relative wages for women. In contrast, an economy starting from a sufficiently high level of capital per worker will converge to a virtuous equilibrium of low fertility, high income per capita, and high relative wages for women. Through exogenous technological progress, the economy can move from the low to the high equilibrium.

Gender inequality in labor market access or returns to brain can slow down or even prevent the escape from the Malthusian equilibrium. Wage discrimination or barriers to employment would work against the rise of relative female wages and, therefore, slow down the takeoff to modern economic growth.

The Galor and Weil model predicts how female labor supply and fertility evolve in the course of development. First, (married) women start participating in market work and only afterwards does fertility start declining. Historically, however, in the US and Western Europe, the decline in fertility occurred before women’s participation rates in the labor market started their dramatic increase. In addition, these regions experienced a mid-twentieth century baby boom which seems at odds with Galor and Weil’s theory.

Both these stylized facts can be addressed by adding home production to the modeling, as do Kimura & Yasui ( 2010 ). In their article, as capital per worker accumulates, the market wage for brains rises and the economy moves through four stages of development. In the first stage, with a sufficiently low market wage, both husband and wife are fully dedicated to home production and childrearing. The household does not supply labor to the market; fertility is high and constant. In the second stage, as the wage rate increases, men enter the labor market (supplying both brawn and brain), whereas women remain fully engaged in home production and childrearing. But as men partially withdraw from home production, women have to replace them. As a result, their time cost of childrearing goes up. At this stage of development, the negative substitution effect of rising wages on fertility dominates the positive income effect. Fertility starts declining, even though women have not yet entered the labor market. The third stage arrives when men stop working in home production. There is complete specialization of labor by gender; men only do market work, and women only do home production and childrearing. As the market wage rises for men, the positive income effect becomes dominant and fertility increases; this mimics the baby-boom period of the mid-twentieth century. In the fourth and final stage, once sufficient capital is accumulated, women enter the market sector as wage-earners. The negative substitution effect of rising female opportunity costs dominates once again, and fertility declines. The economy moves from a “breadwinner model” to a “dual-earnings model”.

Another important form of gender inequality is discrimination against women in the form of lower wages, holding male and female productivity constant. Cavalcanti & Tavares ( 2016 ) estimate the aggregate effects of wage discrimination using a model-based general equilibrium representation of the US economy. In their model, women are assumed to be more productive in childrearing than men, so they pay the full time cost of this activity. In the labor market, even though men and women are equally productive, women receive only a fraction of the male wage rate—this is the wage discrimination assumption. Wage discrimination works as a tax on female labor supply. Because women work less than they would without discrimination, there is a negative level effect on per capita output. In addition, there is a second negative effect of wage discrimination operating through endogenous fertility. Since lower wages reduce women’s opportunity costs of childrearing, fertility is relatively high, and output per capita is relatively low. The authors calibrate the model to US steady state parameters and estimate large negative output costs of the gender wage gap. Reducing wage discrimination against women by 50 percent would raise per capita income by 35 percent, in the long run.

Human capital accumulation plays no role in Galor & Weil ( 1996 ), Kimura & Yasui ( 2010 ), and Cavalcanti & Tavares ( 2016 ). Each person is exogenously endowed with a unit of brains. The fundamental trade-off in the these models is between the income and substitution effects of rising wages on the demand for children. When Lagerlöf ( 2003 ) adds education investments to a gender-based model, an additional trade-off emerges: that between the quantity and the quality of children.

Lagerlöf ( 2003 ) models gender inequality as a social norm: on average, men have higher human capital than women. Confronted with this fact, parents play a coordination game in which it is optimal for them to reproduce the inequality in the next generation. The reason is that parents expect the future husbands of their daughters to be, on average, relatively more educated than the future wives of their sons. Because, in the model, parents care for the total income of their children’s future households, they respond by investing relatively less in daughters’ human capital. Here, gender inequality does not arise from some intrinsic difference between men and women. It is instead the result of a coordination failure: “[i]f everyone else behaves in a discriminatory manner, it is optimal for the atomistic player to do the same” (Lagerlöf 2003 , p. 404).

With lower human capital, women earn lower wages than men and are therefore solely responsible for the time cost of childrearing. But if, exogenously, the social norm becomes more gender egalitarian over time, the gender gap in parental educational investment decreases. As better educated girls grow up and become mothers, their opportunity costs of childrearing are higher. Parents trade-off the quantity of children by their quality; fertility falls and human capital accumulates. However, rising wages have an offsetting positive income effect on fertility because parents pay a (fixed) “goods cost” per child. The goods cost is proportionally more important in poor societies than in richer ones. As a result, in poor economies, growth takes off slowly because the positive income effect offsets a large chunk of the negative substitution effect. As economies grow richer, the positive income effect vanishes (as a share of total income), and fertility declines faster. That is, growth accelerates over time even if gender equality increases only linearly.

The natural next step is to model how the social norm on gender roles evolves endogenously during the course of development. Hiller ( 2014 ) develops such a model by combining two main ingredients: a gender gap in the endowments of brawn (as in Galor & Weil 1996 ) generates a social norm, which each parental couple takes as given (as in Lagerlöf 2003 ). The social norm evolves endogenously, but slowly; it tracks the gender ratio of labor supply in the market, but with a small elasticity. When the male-female ratio in labor supply decreases, stereotypes adjust and the norm becomes less discriminatory against women.

The model generates a U-shaped relationship between economic development and female labor force participation. Footnote 13 In the preindustrial stage, there is no education and all labor activities are unskilled, i.e., produced with brawn. Because men have a comparative advantage in brawn, they supply more labor to the market than women, who specialize in home production. This gender gap in labor supply creates a social norm that favors boys over girls. Over time, exogenous skill-biased technological progress raises the relative returns to brains, inducing parents to invest in their children’s education. At the beginning, however, because of the social norm, only boys become educated. The economy accumulates human capital and grows, generating a positive income effect that, in isolation, would eventually drive up parental investments in girls’ education. Footnote 14 But endogenous social norms move in the opposite direction. When only boys receive education, the gender gap in returns to market work increases, and women withdraw to home production. As female relative labor supply in the market drops, the social norm becomes more discriminatory against women. As a result, parents want to invest relatively less in their daughters’ education.

In the end, initial conditions determine which of the forces dominates, thereby shaping long-term outcomes. If, initially, the social norm is very discriminatory, its effect is stronger than the income effect; the economy becomes trapped in an equilibrium with high gender inequality and low per capita income. If, on the other hand, social norms are relatively egalitarian to begin with, then the income effect dominates, and the economy converges to an equilibrium with gender equality and high income per capita.

In the models reviewed so far, human capital or brain endowments can be understood as combining both education and health. Bloom et al. ( 2015 ) explicitly distinguish these two dimensions. Health affects labor market earnings because sick people are out of work more often (participation effect) and are less productive per hour of work (productivity effect). Female health is assumed to be worse than male health, implying that women’s effective wages are lower than men’s. As a result, women are solely responsible for childrearing. Footnote 15

The model produces two growth regimes: a Malthusian trap with high fertility and no educational investments; and a regime of sustained growth, declining fertility, and rising educational investments. Once wages reach a certain threshold, the economy goes through a fertility transition and education expansion, taking off from the Malthusian regime to the sustained growth regime.

Female health promotes growth in both regimes, and it affects the timing of the takeoff. The healthier women are, the earlier the economy takes off. The reason is that a healthier woman earns a higher effective wage and, consequently, faces higher opportunity costs of raising children. When female health improves, the rising opportunity costs of children reduce the wage threshold at which educational investments become attractive; the fertility transition and mass education periods occur earlier.

In contrast, improved male health slows down economic growth and delays the fertility transition. When men become healthier, there is only a income effect on the demand for children, without the negative substitution effect (because male childrearing time is already zero). The policy conclusion would be to redistribute health from men to women. However, the policy would impose a static utility cost on the household. Because women’s time allocation to market work is constrained by childrearing responsibilities (whereas men work full-time), the marginal effect of health on household income is larger for men than for women. From the household’s point of view, reducing the gender gap in health produces a trade-off between short-term income maximization and long-term economic development.

In an extension of the model, the authors endogeneize health investments, while keeping the assumption that women pay the full time cost of childrearing. Because women participate less in the labor market (due to childrearing duties), it is optimal for households to invest more in male health. A health gender gap emerges from rational household behavior that takes into account how time-constraints differ by gender; assuming taste-based discrimination against girls or gender-specific preferences is not necessary.

In the models reviewed so far, parents invest in their children’s human capital for purely altruistic reasons. This is captured in the models by assuming that parents derive utility directly from the quantity and quality of children. This is the classical representation of children as durable consumption goods (e.g., Becker 1960 ). In reality, of course, parents may also have egoistic motivations for investing in child quantity and quality. A typical example is that, when parents get old and retire, they receive support from their children. The quantity and quality of children will affect the size of old-age transfers and parents internalize this in their fertility and childcare behavior. According to this view, children are best understood as investment goods.

Zhang et al. ( 1999 ) build an endogenous growth model that incorporates the old-age support mechanism in parental decisions. Another innovative element of their model is that parents can choose the gender of their children. The implicit assumption is that sex selection technologies are freely available to all parents.

At birth, there is a gender gap in human capital endowment, favoring boys over girls. Footnote 16 In adulthood, a child’s human capital depends on the initial endowment and on the parents’ human capital. In addition, the probability that a child survives to adulthood is exogenous and can differ by gender.

Parents receive old-age support from children that survive until adulthood. The more human capital children have, the more old-age support they provide to their parents. Beyond this egoistic motive, parents also enjoy the quantity and the quality of children (altruistic motive). Son preference is modeled by boys having a higher relative weight in the altruistic-component of the parental utility function. In other words, in their enjoyment of children as consumer goods, parents enjoy “consuming” a son more than “consuming” a girl. Parents who prefer sons want more boys than girls. A larger preference for sons, a higher relative survival probability of boys, and a higher human capital endowment of boys positively affect the sex ratio at birth, because, in the parents’ perspective, all these forces increase the marginal utility of boys relative to girls.

Zhang et al. ( 1999 ) show that, if human capital transmission from parents to children is efficient enough, the economy grows endogenously. When boys have a higher human capital endowment than girls, and the survival probability of sons is not smaller than the survival probability of daughters, then only sons provide old-age support. Anticipating this, parents invest more in the human capital of their sons than on the human capital of their daughters. As a result, the gender gap in human capital at birth widens endogenously.

When only boys provide old-age support, an exogenous increase in son preference harms long-run economic growth. The reason is that, when son preference increases, parents enjoy each son relatively more and demand less old-age support from him. Other things equal, parents want to “consume” more sons now and less old-age support later. Because parents want more sons, the sex ratio at birth increases; but because each son provides less old-age support, human capital investments per son decrease (such that the gender gap in human capital narrows). At the aggregate level, the pace of human capital accumulation slows down and, in the long run, economic growth is lower. Thus, an exogenous increase in son preference increases the sex ratio at birth, and reduces human capital accumulation and long-run growth (although it narrows the gender gap in education).

In summary, in growth models with unitary households, gender inequality is closely linked to the division of labor between family members. If women earn relatively less in market activities, they specialize in childrearing and home production, while men specialize in market work. And precisely due to this division of labor, the returns to female educational investments are relatively low. These household behaviors translate into higher fertility and lower human capital and thus pose a barrier to long-run development.

4 Intra-household bargaining: husbands and wives

In this section, we review models populated with non-unitary households, where decisions are the result of bargaining between the spouses. There are two broad types of bargaining processes: non-cooperative, where spouses act independently or interact in a non-cooperative game that often leads to inefficient outcomes (e.g., Doepke & Tertilt 2019 , Heath & Tan 2020 ); and cooperative, where the spouses are assumed to achieve an efficient outcome (e.g., De la Croix & Vander Donckt 2010 ; Diebolt & Perrin 2013 ). As in the previous section, all of these non-unitary models take the household as given, thereby abstracting from marriage markets or other household formation institutions, which will be discussed separately in section 5 . When preferences differ by gender, bargaining between the spouses matters for economic growth. If women care more about child quality than men do and human capital accumulation is the main engine of growth, then empowering women leads to faster economic growth (Prettner & Strulik 2017 ). If, however, men and women have similar preferences but are imperfect substitutes in the production of household public goods, then empowering women has an ambiguous effect on economic growth (Doepke & Tertilt 2019 ).

A separate channel concerns the intergenerational transmission of human capital and woman’s role as the main caregiver of children. If the education of the mother matters more than the education of the father in the production of children’s human capital, then empowering women will be conducive to growth (Agénor 2017 ; Diebolt & Perrin 2013 ), with the returns to education playing a crucial role in the political economy of female empowerment (Doepke & Tertilt 2009 ).

However, different dimensions of gender inequality have different growth impacts along the development process (De la Croix & Vander Donckt 2010 ). Policies that improve gender equality across many dimensions can be particularly effective for economic growth by reaping complementarities and positive externalities (Agénor 2017 ).

The idea that women might have stronger preferences for child-related expenditures than men can be easily incorporated in a Beckerian model of fertility. The necessary assumption is that women place a higher weight on child quality (relative to child quantity) than men do. Prettner & Strulik ( 2017 ) build a unified growth theory model with collective households. Men and women have different preferences, but they achieve efficient cooperation based on (reduced-form) bargaining parameters. The authors study the effect of two types of preferences: (i) women are assumed to have a relative preference for child quality, while men have a relative preference for child quantity; and (ii) parents are assumed to have a relative preference for the education of sons over the education of daughters. In addition, it is assumed that the time cost of childcare borne by men cannot be above that borne by women (but it could be the same).

When women have a relative preference for child quality, increasing female empowerment speeds up the economy’s escape from a Malthusian trap of high fertility, low education, and low income per capita. When female empowerment increases (exogenously), a woman’s relative preference for child quality has a higher impact on household’s decisions. As a consequence, fertility falls, human capital accumulates, and the economy starts growing. The model also predicts that the more preferences for child quality differ between husband and wife, the more effective is female empowerment in raising long-run per capita income, because the sooner the economy escapes the Malthusian trap. This effect is not affected by whether parents have a preference for the education of boys relative to that of girls. If, however, men and women have similar preferences with respect to the quantity and quality of their children, then female empowerment does not affect the timing of the transition to the sustained growth regime.

Strulik ( 2019 ) goes one step further and endogeneizes why men seem to prefer having more children than women. The reason is a different preference for sexual activity: other things equal, men enjoy having sex more than women. Footnote 17 When cheap and effective contraception is not available, a higher male desire for sexual activity explains why men also prefer to have more children than women. In a traditional economy, where no contraception is available, fertility is high, while human capital and economic growth are low. When female bargaining power increases, couples reduce their sexual activity, fertility declines, and human capital accumulates faster. Faster human capital accumulation increases household income and, as a consequence, the demand for contraception goes up. As contraception use increases, fertility declines further. Eventually, the economy undergoes a fertility transition and moves to a modern regime with low fertility, widespread use of contraception, high human capital, and high economic growth. In the modern regime, because contraception is widely used, men’s desire for sex is decoupled from fertility. Both sex and children cost time and money. When the two are decoupled, men prefer to have more sex at the expense of the number of children. There is a reversal in the gender gap in desired fertility. When contraceptives are not available, men desire more children than women; once contraceptives are widely used, men desire fewer children than women. If women are more empowered, the transition from the traditional equilibrium to the modern equilibrium occurs faster.

Both Prettner & Strulik ( 2017 ) and Strulik ( 2019 ) rely on gender-specific preferences. In contrast, Doepke & Tertilt ( 2019 ) are able to explain gender-specific expenditure patterns without having to assume that men and women have different preferences. They set up a non-cooperative model of household decision making and ask whether more female control of household resources leads to higher child expenditures and, thus, to economic development. Footnote 18

In their model, household public goods are produced with two inputs: time and goods. Instead of a single home-produced good (as in most models), there is a continuum of household public goods whose production technologies differ. Some public goods are more time-intensive to produce, while others are more goods-intensive. Each specific public good can only be produced by one spouse—i.e., time and good inputs are not separable. Women face wage discrimination in the labor market, so their opportunity cost of time is lower than men’s. As a result, women specialize in the production of the most time-intensive household public goods (e.g., childrearing activities), while men specialize in the production of goods-intensive household public goods (e.g., housing infrastructure). Notice that, because the household is non-cooperative, there is not only a division of labor between husband and wife, but also a division of decision making, since ultimately each spouse decides how much to provide of his or her public goods.

When household resources are redistributed from men to women (i.e., from the high-wage spouse to the low-wage spouse), women provide more public goods, in relative terms. It is ambiguous, however, whether the total provision of public goods increases with the re-distributive transfer. In a classic model of gender-specific preferences, a wife increases child expenditures and her own private consumption at the expense of the husband’s private consumption. In Doepke & Tertilt ( 2019 ), however, the rise in child expenditures (and time-intensive public goods in general) comes at the expense of male consumption and male-provided public goods.

Parents contribute to the welfare of the next generation in two ways: via human capital investments (time-intensive, typically done by the mother) and bequests of physical capital (goods-intensive, typically done by the father). Transferring resources to women increases human capital, but reduces the stock of physical capital. The effect of such transfers on economic growth depends on whether the aggregate production function is relatively intensive in human capital or in physical capital. If aggregate production is relatively human capital intensive, then transfers to women boost economic growth; if it is relatively intensive in physical capital, then transfers to women may reduce economic growth.

There is an interesting paradox here. On the one hand, transfers to women will be growth-enhancing in economies where production is intensive in human capital. These would be more developed, knowledge intensive, service economies. On the other hand, the positive growth effect of transfers to women increases with the size of the gender wage gap, that is, decreases with female empowerment. But the more advanced, human capital intensive economies are also the ones with more female empowerment (i.e., lower gender wage gaps). In other words, in settings where human capital investments are relatively beneficial, the contribution of female empowerment to human capital accumulation is reduced. Overall, Doepke and Tertilt’s ( 2019 ) model predicts that female empowerment has at best a limited positive effect and at worst a negative effect on economic growth.

Heath & Tan ( 2020 ) argue that, in a non-cooperative household model, income transfers to women may increase female labor supply. Footnote 19 This result may appear counter-intuitive at first, because in collective household models unearned income unambiguously reduces labor supply through a negative income effect. In Heath and Tan’s model, husband and wife derive utility from leisure, consuming private goods, and consuming a household public good. The spouses decide separately on labor supply and monetary contributions to the household public good. Men and women are identical in preferences and behavior, but women have limited control over resources, with a share of their income being captured by the husband. Female control over resources (i.e., autonomy) depends positively on the wife’s relative contribution to household income. Thus, an income transfer to the wife, keeping husband unearned income constant, raises the fraction of her own income that she privately controls. This autonomy effect unambiguously increases women’s labor supply, because the wife can now reap an additional share of her wage bill. Whenever the autonomy effect dominates the (negative) income effect, female labor supply increases. The net effect will be heterogeneous over the wage distribution, but the authors show that aggregate female labor supply is always weakly larger after the income transfer.

Diebolt & Perrin ( 2013 ) assume cooperative bargaining between husband and wife, but do not rely on sex-specific preferences or differences in ability. Men and women are only distinguished by different uses of their time endowments, with females in charge of all childrearing activities. In line with this labor division, the authors further assume that only the mother’s human capital is inherited by the child at birth. On top of the inherited maternal endowment, individuals can accumulate human capital during adulthood, through schooling. The higher the initial human capital endowment, the more effective is the accumulation of human capital via schooling.

A woman’s bargaining power in marriage determines her share in total household consumption and is a function of the relative female human capital of the previous generation. An increase in the human capital of mothers relative to that of fathers has two effects. First, it raises the incentives for human capital accumulation of the next generation, because inherited maternal human capital makes schooling more effective. Second, it raises the bargaining power of the next generation of women and, because women’s consumption share increases, boosts the returns on women’s education. The second effect is not internalized in women’s time allocation decisions; it is an intergenerational externality. Thus, an exogenous increase in women’s bargaining power would promote economic growth by speeding up the accumulation of human capital across overlapping generations.

De la Croix & Vander Donckt ( 2010 ) contribute to the literature by clearly distinguishing between different gender gaps: a gap in the probability of survival, a wage gap, a social and institutional gap, and a gender education gap. The first three are exogenously given, while the fourth is determined within the model.

By assumption, men and women have identical preferences and ability, but women pay the full time cost of childrearing. As in a typical collective household model, bargaining power is partially determined by the spouses’ earnings potential (i.e., their levels of human capital and their wage rates). But there is also a component of bargaining power that is exogenous and captures social norms that discriminate against women—this is the social and institutional gender gap.

Husbands and wives bargain over fertility and human capital investments for their children. A standard Beckerian result emerges: parents invest relatively less in the education of girls, because girls will be more time-constrained than boys and, therefore, the female returns to education are lower in relative terms.

There are at least two regimes in the economy: a corner regime and an interior regime. The corner regime consists of maximum fertility, full gender specialization (no women in the labor market), and large gender gaps in education (no education for girls). Reducing the wage gap or the social and institutional gap does not help the economy escaping this regime. Women are not in labor force, so the wage gap is meaningless. The social and institutional gap will determine women’s share in household consumption, but does not affect fertility and growth. At this stage, the only effective instruments for escaping the corner regime are reducing the gender survival gap or reducing child mortality. Reducing the gender survival gap increases women’s lifespan, which increases their time budget and attracts them to the labor market. Reducing child mortality decreases the time costs of kids, therefore drawing women into the labor market. In both cases, fertility decreases.

In the interior regime, fertility is below the maximum, women’s labor supply is above zero, and both boys and girls receive education. In this regime, with endogenous bargaining power, reducing all gender gaps will boost economic growth. Footnote 20 Thus, depending on the growth regime, some gender gaps affect economic growth, while others do not. Accordingly, the policy-maker should tackle different dimensions of gender inequality at different stages of the development process.

Agénor ( 2017 ) presents a computable general equilibrium that includes many of the elements of gender inequality reviewed so far. An important contribution of the model is to explicitly add the government as an agent whose policies interact with family decisions and, therefore, will impact women’s time allocation. Workers produce a market good and a home good and are organized in collective households. Bargaining power depends on the spouses’ relative human capital levels. By assumption, there is gender discrimination in market wages against women. On top, mothers are exclusively responsible for home production and childrearing, which takes the form of time spent improving children’s health and education. But public investments in education and health also improve these outcomes during childhood. Likewise, public investment in public infrastructure contributes positively to home production. In particular, the ratio of public infrastructure capital stock to private capital stock is a substitute for women’s time in home production. The underlying idea is that improving sanitation, transportation, and other infrastructure reduces time spent in home production. Health status in adulthood depends on health status in childhood, which, in turn, relates positively to mother’s health, her time inputs into childrearing, and government spending. Children’s human capital depends on similar factors, except that mother’s human capital replaces her health as an input. Additionally, women are assumed to derive less utility from current consumption and more utility from children’s health relative to men. Wives are also assumed to live longer than their husbands, which further down-weights female’s emphasis on current consumption. The final gendered assumption is that mother’s time use is biased towards boys. This bias alone creates a gender gap in education and health. As adults, women’s relative lower health and human capital are translated into relative lower bargaining power in household decisions.

Agénor ( 2017 ) calibrates this rich setup for Benin, a low income country, and runs a series of policy experiments on different dimensions of gender inequality: a fall in childrearing costs, a fall in gender pay discrimination, a fall in son bias in mother’s time allocation, and an exogenous increase in female bargaining power. Footnote 21 Interestingly, despite all policies improving gender equality in separate dimensions, not all unambiguously stimulate economic growth. For example, falling childrearing costs raise savings and private investments, which are growth-enhancing, but increase fertility (as children become ‘cheaper’) and reduce maternal time investment per child, thus reducing growth. In contrast, a fall in gender pay discrimination always leads to higher growth, through higher household income that, in turn, boosts savings, tax revenues, and public spending. Higher public spending further contributes to improved health and education of the next generation. Lastly, Agénor ( 2017 ) simulates the effect of a combined policy that improves gender equality in all domains simultaneously. Due to complementarities and positive externalities across dimensions, the combined policy generates more economic growth than the sum of the individual policies. Footnote 22

In the models reviewed so far, men are passive observers of women’s empowerment. Doepke & Tertilt ( 2009 ) set up an interesting political economy model of women’s rights, where men make the decisive choice. Their model is motivated by the fact that, historically, the economic rights of women were expanded before their political rights. Because the granting of economic rights empowers women in the household, and this was done before women were allowed to participate in the political process, the relevant question is why did men willingly share their power with their wives?

Doepke & Tertilt ( 2009 ) answer this question by arguing that men face a fundamental trade-off. On the one hand, husbands would vote for their wives to have no rights whatsoever, because husbands prefer as much intra-household bargaining power as possible. But, on the other hand, fathers would vote for their daughters to have economic rights in their future households. In addition, fathers want their children to marry highly educated spouses, and grandfathers want their grandchildren to be highly educated. By assumption, men and women have different preferences, with women having a relative preference for child quality over quantity. Accordingly, men internalize that, when women become empowered, human capital investments increase, making their children and grandchildren better-off.

Skill-biased (exogenous) technological progress that raises the returns to education over time can shift male incentives along this trade-off. When the returns to education are low, men prefer to make all decisions on their own and deny all rights to women. But once the returns to education are sufficiently high, men voluntarily share their power with women by granting them economic rights. As a result, human capital investments increase and the economy grows faster.

In summary, gender inequality in labor market earnings often implies power asymmetries within the household, with men having more bargaining power than women. If preferences differ by gender and female preferences are more conducive to development, then empowering women is beneficial for growth. When preferences are the same and the bargaining process is non-cooperative, the implications are less clear-cut, and more context-specific. If, in addition, women’s empowerment is curtailed by law (e.g., restrictions on women’s economic rights), then it is important to understand the political economy of women’s rights, in which men are crucial actors.

5 Marriage markets and household formation

Two-sex models of economic growth have largely ignored how households are formed. The marriage market is not explicitly modeled: spouses are matched randomly, marriage is universal and monogamous, and families are nuclear. In reality, however, household formation patterns vary substantially across societies, with some of these differences extending far back in history. For example, Hajnal ( 1965 , 1982 ) described a distinct household formation pattern in preindustrial Northwestern Europe (often referred to as the “European Marriage Pattern”) characterized by: (i) late ages at first marriage for women, (ii) most marriages done under individual consent, and (iii) neolocality (i.e., upon marriage, the bride and the groom leave their parental households to form a new household). In contrast, marriage systems in China and India consisted of: (i) very early female ages at first marriage, (ii) arranged marriages, and (iii) patrilocality (i.e., the bride joins the parental household of the groom).

Economic historians argue that the “European Marriage Pattern” empowered women, encouraging their participation in market activities and reducing fertility levels. While some view this as one of the deep-rooted factors explaining Northwestern Europe’s earlier takeoff to sustained economic growth (e.g., Carmichael, de Pleijt, van Zanden and De Moor 2016 ; De Moor & Van Zanden 2010 ; Hartman 2004 ), others have downplayed the long-run significance of this marriage pattern (e.g., Dennison & Ogilvie 2014 ; Ruggles 2009 ). Despite this lively debate, the topic has been largely ignored by growth theorists. The few exceptions are Voigtländer and Voth ( 2013 ), Edlund and Lagerlöf ( 2006 ), and Tertilt ( 2005 , 2006 ).

After exploring different marriage institutions, we zoom in on contemporary monogamous and consensual marriage and review models where gender inequality affects economic growth through marriage markets that facilitate household formation (Du & Wei 2013 ; Grossbard & Pereira 2015 ; Grossbard-Shechtman 1984 ; Guvenen & Rendall 2015 ). In contrast with the previous two sections, where the household is the starting point of the analysis, the literature on marriage markets and household formation recognizes that marriage, labor supply, and investment decisions are interlinked. The analysis of these interlinkages is sometimes done with unitary households (upon marriage) (Du & Wei 2013 ; Guvenen & Rendall 2015 ), or with non-cooperative models of individual decision-making within households (Grossbard & Pereira 2015 ; Grossbard-Shechtman 1984 ).

Voigtländer and Voth ( 2013 ) argue that the emergence of the “European Marriage Pattern” is a direct consequence of the mid-fourteen century Black Death. They set up a two-sector agricultural economy consisting of physically demanding cereal farming, and less physically demanding pastoral production. The economy is populated by many male and female peasants and by a class of idle, rent-maximizing landlords. Female peasants are heterogeneous with respect to physical strength, but, on average, are assumed to have less brawn relative to male peasants and, thus, have a comparative advantage in the pastoral sector. Both sectors use land as a production input, although the pastoral sector is more land-intensive than cereal production. All land is owned by the landlords, who can rent it out for peasant cereal farming, or use it for large-scale livestock farming, for which they hire female workers. Crucially, women can only work and earn wages in the pastoral sector as long as they are unmarried. Footnote 23 Peasant women decide when to marry and, upon marriage, a peasant couple forms a new household, where husband and wife both work on cereal farming, and have children at a given time frequency. Thus, the only contraceptive method available is delaying marriage. Because women derive utility from consumption and children, they face a trade-off between earned income and marriage.

Initially, the economy rests in a Malthusian regime, where land-labor ratios are relatively low, making the land-intensive pastoral sector unattractive and depressing relative female wages. As a result, women marry early and fertility is high. The initial regime ends in 1348–1350, when the Black Death kills between one third and half of Europe’s population, exogenously generating land abundance and, therefore, raising the relative wages of female labor in pastoral production. Women postpone marriage to reap higher wages, and fertility decreases—moving the economy to a regime of late marriages and low fertility.

In addition to late marital ages and reduced fertility, another important feature of the “European Marriage Pattern” was individual consent for marriage. Edlund and Lagerlöf ( 2006 ) study how rules of consent for marriage influence long-run economic development. In their model, marriages can be formed according to two types of consent rules: individual consent or parental consent. Under individual consent, young people are free to marry whomever they wish, while, under parental consent, their parents are in charge of arranging the marriage. Depending on the prevailing rule, the recipient of the bride-price differs. Under individual consent, a woman receives the bride-price from her husband, whereas, under parental consent, her father receives the bride-price from the father of the groom. Footnote 24 In both situations, the father of the groom owns the labor income of his son and, therefore, pays the bride-price, either directly, under parental consent, or indirectly, under individual consent. Under individual consent, the father needs to transfer resources to his son to nudge him into marrying. Thus, individual consent implies a transfer of resources from the old to the young and from men to women, relative to the rule of parental consent. Redistributing resources from the old to the young boosts long-run economic growth. Because the young have a longer timespan to extract income from their children’s labor, they invest relatively more in the human capital of the next generation. In addition, under individual consent, the reallocation of resources from men to women can have additional positive effects on growth, by increasing women’s bargaining power (see section 4 ), although this channel is not explicitly modeled in Edlund and Lagerlöf ( 2006 ).

Tertilt ( 2005 ) explores the effects of polygyny on long-run development through its impact on savings and fertility. In her model, parental consent applies to women, while individual consent applies to men. There is a competitive marriage market where fathers sell their daughters and men buy their wives. As each man is allowed (and wants) to marry several wives, a positive bride-price emerges in equilibrium. Footnote 25 Upon marriage, the reproductive rights of the bride are transferred from her father to her husband, who makes all fertility decisions on his own and, in turn, owns the reproductive rights of his daughters. From a father’s perspective, daughters are investments goods; they can be sold in the marriage market, at any time. This feature generates additional demand for daughters, which increases overall fertility, and reduces the incentives to save, which decreases the stock of physical capital. Under monogamy, in contrast, the equilibrium bride-price is negative (i.e., a dowry). The reason is that maintaining unmarried daughters is costly for their fathers, so they are better-off paying a (small enough) dowry to their future husbands. In this setting, the economic returns to daughters are lower and, consequently, so is the demand for children. Fertility decreases and savings increase. Thus, moving from polygny to monogamy lowers population growth and raises the capital stock in the long run, which translates into higher output per capita in the steady state.

Instead of enforcing monogamy in a traditionally polygynous setting, an alternative policy is to transfer marriage consent from fathers to daughters. Tertilt ( 2006 ) shows that when individual consent is extended to daughters, such that fathers do not receive the bride-price anymore, the consequences are qualitatively similar to a ban on polygyny. If fathers stop receiving the bride-price, they save more physical capital. In the long run, per capita output is higher when consent is transferred to daughters.