Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Intercultural Communication — Intercultural Communication: Understanding, Challenges, and Importance

Intercultural Communication: Understanding, Challenges, and Importance

- Categories: Intercultural Communication

About this sample

Words: 2184 |

11 min read

Published: Aug 14, 2023

Words: 2184 | Pages: 5 | 11 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, the meaning of culture, communication as a part of intercultural communication, intercultural communication defined, the importance of studying intercultural communication, barriers to intercultural communication.

- Understanding your own identity.

- Enhancing personal and social interactions.Solving misunderstandings, miscommunications & mistrust.

- Enhancing and enriching the quality of civilization.

- Becoming effective citizens of our national communities

- Ethnocentrism

- Stereotyping

- Discrimination

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

5 pages / 2486 words

5 pages / 2229 words

2 pages / 720 words

3 pages / 1503 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Intercultural Communication

NAKAI, F. (2002). The Role of Cultural Influences in Japanese Communication : A Literature Review on Social and Situational Factors and Japanese Indirectness Fuki NAKAI. Japan: Fuki NAKAI, p.114.Terzuolo, C. (2019). Navigating [...]

Intercultural communication is a vital component of our increasingly interconnected world, enabling individuals to effectively navigate diverse cultural environments and interact with people from different backgrounds. In [...]

In a world that constantly brings individuals from diverse backgrounds together, the complexities and implications of interacting with strangers become increasingly relevant. This essay delves into the intricate dynamics of [...]

The concept of intercultural encounters has gained immense significance in our increasingly interconnected world. These encounters refer to the interactions between individuals or groups from different cultural backgrounds, [...]

I never moved schools, not even once. For the past 18 years, I have always lived in a densely packed town called Bandar Lampung – a city on the southern tip of Sumatra Island, Indonesia. I had always been surrounded by familiar [...]

The term “Gung Ho” is an Americanized Chinese expression for “Work” and “Together”. Gung Ho is a 1986 comedy film which was directed by Ron Howard and starring Michael Keaton. The movie is a very good reflection of the real time [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

APPLY NOW --> REQUEST INFO

Apply Today

Ready to apply to Penn LPS Online? Apply Now

Learn more about Penn LPS Online

Request More Information

Why cross-cultural communication is important—and how to practice it effectively

Many bachelor’s degree programs require students to complete a few courses in a foreign language; learning another language can be a vital skill in many careers as well as a way to gain broader perspective on culture and global connections. But language instruction often requires an immersive and intensive classroom schedule that isn’t well-suited to part-time study or the flexible online platform offered by Penn LPS Online’s Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences (BAAS) degree.

“When we were thinking about what the new Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences would look like, we thought that the residential language program didn’t work as well to address the needs of a very diverse student body which might not even be located here in Philadelphia,” recalls Dr. Christina Frei, Academic Director of the Penn Language Center . “We needed to figure out a way to still have a discussion about language in the degree. I proposed that we offer a course that focuses on the role that language plays in intercultural communication.”

The resulting course is one of the foundational requirements of the BAAS degree. The purpose of ICOM 100: Intercultural Communication is to develop effective communication skills and cultural understanding globally as well as within diverse communities. While the Intercultural Communication course does not replace the intensive language instruction necessary to speak and read in another language, it does develop the intercultural perspective, which is vital to learning a new language and engaging meaningfully with people across language and cultural differences. “Language is embedded and highly connected to culture. One cannot understand language outside of cultural or vice versa,” says Frei. “I designed the course to pique students' interest in the power of language and the complexities of language and culture.”

What is intercultural communication?

Intercultural communication has become a key concept in language instruction, but only recently. “In the last 20 years—and particularly in the last 10 years—we really understand more about the role that language plays in identity,” says Frei. In her many roles at Penn, Frei ensures that language and cultural studies meet the standards of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL), which has started to center identity and culture. At the Penn Language Center, which houses language instruction that falls outside of established foreign language departments such as the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures (for which Frei is the Undergraduate Chair), Frei oversees course offerings and learning opportunities in languages spoken in Africa and South Asia as well as American Sign Language and even language instruction for professional use (such as Spanish for health professionals and Chinese for business). Frei is also the Executive Director of Language Instruction for the School of Arts and Sciences, and in that capacity, she oversees language education across Penn to ensure professional standards are met and a cohesive pedagogical approach is achieved. “Over the last 10 years, the best practices have changed, and ACTFL really has begun to look towards intercultural communication,” says Frei.

To understand what intercultural communication is, it helps to understand culture as something active and pervasive. “Culture is a verb,” says Frei, citing one of the assigned texts from her course: Intercultural Communication: A Critical Introduction by Ingrid Piller. “You’re doing culture all the time,” explains Frei. “In order to become aware of what culture actually is, you have to really develop a critical eye to look at your perceptions and your surroundings.” Doing culture can include ways of speaking and acting but also thoughts and beliefs you’re not even aware of—although you’re most likely to become aware of how you “do culture” when you interact with someone who “does culture” differently. Intercultural communication encompasses a vast array of verbal and nonverbal interactions that may take place on such occasions: learning a new language or visiting another country are common examples but joining a new workplace or participating in a community organization with members of diverse backgrounds can also engage intercultural communication skills.

“If you want to do culture interculturally, you cannot do it by exclusion,” adds Frei. “Inclusivity, to me, is the new word for being truly multicultural, to really be open-minded and understanding about the differences that human beings have in their lives, their languages, and in their beliefs and cultural practices.”

The importance of intercultural communication

Intercultural communication plays a pivotal role in our increasingly globalized world, where people from various cultural backgrounds interact regularly. It is of paramount importance as it facilitates understanding and collaboration among individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds, helping to break down the walls of stereotypes and assumptions that can hinder effective communication. In a world where cultural diversity is the norm, effective intercultural communication fosters empathy, reduces misunderstandings arising from differing cultural norms, and promotes tolerance. By embracing the nuances of different cultures, we bridge divides and harness the rich tapestry of perspectives, ideas, and talents that diverse populations bring to the table. It is a cornerstone for successful diplomacy, international business, and peaceful coexistence. Intercultural communication promotes unity in diversity, enhancing our collective capacity to address global challenges and build a more inclusive and harmonious global community.

How do you develop intercultural understanding in the classroom?

To provide a broad range of opportunities for students to analyze examples of “doing culture,” the Intercultural Communication course incorporates an array of readings, videos, and websites to explore different ways of expressing and interpreting culture through language. There are recorded interviews with scholars and activists who have compelling perspectives on how to “do culture” as a member of a minority population: a Lakota historian who protested the construction of a pipeline in the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, an applied linguist involved in a social impact project with a Bangladeshi community in Philadelphia, and the director of the American Sign Language program at Penn who shares insight about language and culture within the deaf community. In addition to the Intercultural Communication textbook and assorted reading assignments, the students read The Enigma of Arrival , V.S. Naipaul’s autobiographical novel about his journey from the island of Trinidad to the countryside of England. “It’s a fabulous book that I hope the students enjoy reading,” says Frei. “It’s one person’s story about coming to a new place and doing culture from the outside, so to speak. There is a lot of self-observation and self-reflectivity about how, as he is doing culture, he begins to understand himself and the place differently.”

Students analyze and reflect on these cultural artifacts in class discussions and written assignments. “The workshops that I usually offer here at Penn and the courses I teach have a communicative approach with a lot of reflection, so that's part of the Intercultural Communication course as well,” says Frei. “We do tons of personal reflection because it’s important to know what your own prejudices are, what your own value system is, what your own sense-making is, and what your own analysis is, and what your own observations are.” In particular, students are asked to step back and observe how they communicate with others, from workplace and religious communities to interactions with friends and family to brief encounters at the supermarket. “It's almost like an anthropological journal, if you wish,” says Frei. ”It builds a particular kind of sensitivity to observe without judgment what you’re thinking and how you react, which helps you to be inclusive, to have empathy, and to understand the people you engage with.”

Though the course is asynchronous, Frei says, discussion boards and reflective practices bring students into the discussion and require them to communicate clearly and thoughtfully with one another. “Perhaps that’s the beauty of an online course,” says Frei. “You really do need to listen or read and pay attention to what your peers are saying. I think they really will gain an understanding of what intercultural communication means to each of them.”

“The students are actually creating the knowledge of the course,” she adds. “I'm giving them a tool kit, but what they actually do with it is up to them—and that’s very exciting.”

Tips for effective cross-cultural communication

To succeed in the course, Frei emphasizes that students need to pace themselves and schedule themselves plenty of time to think, reflect, and feel as they go through the coursework. “These are not just assignments where you can just check a box and you're done. These are thinking pieces,” says Frei. “Students need to really make sure to put some time aside because they have to think in order to do the work. They need to allow themselves to be open-minded about themselves and perhaps, in their own thinking, surprise themselves.”

Time management gives students the space needed to develop their practice of reflection, which is an important skill for communication in any context. For Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences students, Frei notes, reflection is built-in throughout the entire degree, culminating in the ePortfolio degree requirement . “It makes complete sense,” she says. “The ePortfolio is not just a curated collection of your best work. It’s a curated collection that you thought about and where you reflected on your benchmarks, your rubrics, your qualifiers for your best work.” Likewise, reflection is a vital step in thinking about culture and language.

But to Frei, reflection is deeply entwined with the concept of self-care. “Ask yourself: How can I be healthy emotionally, intellectually, physically? How does that all come into the mix?” says Frei. In her German classes, Frei will often ask students to complete a self-assessment of their reading practices: where do they typically sit, how focused do they usually feel, what kinds of emotions to do they experience and when. By being attuned to those details, says Frei, a student can make choices that will help them both enjoy and absorb more in their reading. Likewise, when it comes to language and culture, “self-care is key,” she says. “Self-reflection and understanding your own practices, your own cultural beliefs, your own cultural practices and perspectives will help you to sensitize you.”

“This is a course that shares knowledge through books and instructional design. You’ll gain insights into minority discourses and you’ll learn about communication and language. Those skills are transferable to other courses,” says Frei. “But it’s also a place where you can get to know yourself a little bit more. I think that could be really helpful.”

For more information about this unique online degree and its requirements, visit the Penn LPS Online feature “What is a Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences degree? ”

Dive deeper into all the opportunities available through Penn LPS Online by visiting our homepage .

Cross-Cultural Narratives: Stories and Experiences of International Students

- Publisher: STAR Scholars

- Editor: Ravichandran Ammigan

- ISBN: 978-1-7364699-0-3

- University of Delaware

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Carolina Gomez

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 23 March 2022

Communication competencies, culture and SDGs: effective processes to cross-cultural communication

- Stella Aririguzoh 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 9 , Article number: 96 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

32k Accesses

30 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

- Cultural and media studies

Globalization has made it necessary for people from different cultures and nations to interact and work together. Effective cross-cultural communication seeks to change how messages are packaged and sent to people from diverse cultural backgrounds. Cross-cultural communication competencies make it crucial to appreciate and respect noticeable cultural differences between senders and receivers of information, especially in line with the United Nations’ (UN) recognition of culture as an agent of sustainable development. Miscommunication and misunderstanding can result from poorly encrypted messages that the receiver may not correctly interpret. A culture-literate communicator can reduce miscommunication arising from a low appreciation of cultural differences so that a clement communication environment is created and sustained. This paper looks at the United Nations’ recognition of culture and how cultural differences shape interpersonal communication. It then proposes strategies to enhance cross-cultural communication at every communication step. It advocates that for the senders and receivers of messages to improve communication efficiency, they must be culture and media literates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Assessment of the impacts of artificial intelligence (AI) on intercultural communication among postgraduate students in a multicultural university environment

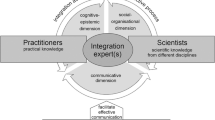

Communication tools and their support for integration in transdisciplinary research projects

Challenges in implementing cultural adaptations of digital health interventions, public interest.

The United Nations has recognized culture as a causal agent of sustainability and integrated it into the SDG goals. Culture reinforces the economic, social, and communal fabrics that regulate social cohesion. Communication helps to maintain social order. The message’s sender and the receiver’s culture significantly influence how they communicate and relate with other people outside their tribal communities. Globalization has compelled people from widely divergent cultural backgrounds to work together.

People unconsciously carry their cultural peculiarities and biases into their communication processes. Naturally, there have been miscommunications and misunderstandings because people judge others based on their cultural values. Our cultures influence our behaviour and expectations from other people.

Irrespective of our ethnicities, people want to communicate, understand, appreciate, and be respected by others. Culture literate communicators can help clear some of these challenges, create more tolerant communicators, and contribute to achieving global sustainable goals.

Introduction

The United Nations established 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 to transform the world by 2030 through simultaneously promoting prosperity and protecting the earth. The global body recognizes that culture directly influences development. Thus, SDG Goal 4.7 promotes “… a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development.” Culture really matters (Seymour, 2007 ). Significantly, cultural cognition influences how people process information from different sources and suggests policies they may support or oppose (Rachlinski, 2021 ). Culture can drive sustainable development (United Nations, 2015 ; De Beukelaer and Freita, 2015 ; Kangas et al., 2017 ; Heckler, 2014 ; Dessein et al., 2015 ; and Hosagrahar, 2017 ).

UNESCO ( 2013 , p.iii ; 2017 , p.16; 2013a , p. 30) unequivocally states that “culture is a driver of development,” an “enabler of sustainable development and essential for achieving the 2030 Agenda” and as “an essential pillar for sustainable development.” These bold declarations have led to the growth of the cultural sector. The culture industry encourages economic growth through cultural tourism, handicraft production, creative industries, agriculture, food, medicine, and fisheries. Culture is learned social values, beliefs, and customs that some people accept and share collectively. It includes all the broad knowledge, beliefs, art, morals, law, customs, and other experiences and habits acquired by man as a member of a particular society. This seems to support Guiso, Paola and Luigi ( 2006 , p. 23) view of culture as “those customary beliefs and values that ethnic, religious, and social groups transmit fairly unchanged from generation to generation.” They assert that there is a causality between culture and economic outcomes. Bokova ( 2010 ) claims that “the links between culture and development are so strong that development cannot dispense with culture” and “that these links cannot be separated.” Culture includes customs and social behaviour. Causadias ( 2020 ) claims that culture is a structure that connects people, places, and practices. Ruane and Todd ( 2004 ) write that these connections are everyday matters like language, rituals, kingship, economic way of life, general lifestyle, and labour division. Field ( 2008 ) notes that even though all cultural identities are historically constructed, they still undergo changes, transformation, and mutation with time. Although Barth ( 1969 ) affirms that ethnicity is not culture, he points out that it helps define a group and its cultural stuff . The shared cultural stuff provides the basis for ethnic enclosure or exclusion.

The cultural identities of all men will never be the same because they come from distinctive social groups. Cultural identification sorts interactions into two compartments: individual or self-identification and identification with other people. Thus, Jenkins ( 2014 ) sees social identity as the interface between similarities and differences, the classification of others, and self-identification. He argues that people would not relate to each other in meaningful ways without it. People relate both as individuals and as members of society. Ethnicity is the “world of personal identity collectively ratified and publicly expressed” and “socially ratified personal identity‟ (Geertz, 1973 , p. 268, 309). However, the future of ethnicity has been questioned because culture is now seen as a commodity. Many tribal communities are packaging some aspects of their cultural inheritances to sell to other people who are not from their communities (Comaroff and Comaroff, 2009 ).

There is a relationship between culture and communication. People show others their identities through communication. Communication uses symbols, for example, words, to send messages to recipients. According to Kurylo ( 2013 ), symbols allow culture to be represented or constructed through verbal and nonverbal communication. Message receivers may come from different cultural backgrounds. They try to create meaning by interpreting the symbols used in communication. Miscommunication and misunderstanding may arise because symbols may not have the same meaning for both the sender and receiver of messages. If these are not efficiently handled, they may lead to stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. Monaghan ( 2020 ), Zhu ( 2016 ), Holmes ( 2017 ), Merkin ( 2017 ), and Samovar et al. ( 2012 ) observe that inter-cultural communication occurs between people from different cultural groups. It shows how people from different cultural backgrounds can effectively communicate by comparing, contrasting, and examining the consequences of the differences in their communication patterns. However, communicating with others from different cultural backgrounds can be full of challenges, surprises, and re-learning because languages, values, and protocols differ. Barriers, like language and noise, impede communication by distorting, blocking, or altering the meaning.

Communication patterns change from one nation to the next. It is not uncommon, for example, for an American, a Nigerian, a Japanese national, or citizens of other countries to work together on a single project in today’s multi-cultural workplace. These men and women represent different cultural heritages. Martinovski ( 2018 ) remarks that both humans and virtual agents interact in cross-cultural environments and need to correctly behave as demanded by their environment. Possibly too, they may learn how to avoid conflicts and live together. Indeed, García-Carbonell and Rising ( 2006 , p. 2) remark that “as the world becomes more integrated, bridging the gap in cultural conflicts through real communication is increasingly important to people in all realms of society.” Communication is used to co-ordinate the activities in an organization for it to achieve its goals. It is also used to signal and order those involved in the work process.

This paper argues that barriers to cross-cultural communication can be overcome or significantly reduced if the actors in the communication processes become culture literates and competent communicators.

Statement of the problem

The importance of creating and maintaining good communication in human society cannot be overemphasized. Effective communication binds and sustains the community. Cross-cultural communication problems usually arise from confusion caused by misconstruction, misperception, misunderstanding, and misvaluation of messages from different standpoints arising from differences in the cultures of the senders and receivers of messages. Divergences in cultural backgrounds result in miscommunication that negatively limits effective encrypting, transmission, reception, and information decoding. It also hinders effective feedback.

With the rapid spread of communication technologies, no community is completely isolated from the rest of the world. Present-day realities, such as new job opportunities and globalization, compel some people to move far away from their local communities and even their countries of origin to other places where the cultures are different. Globalization minimizes the importance of national borders. The world is no longer seen as a globe of many countries but as a borderless entity (Ohmae, 1999 ) and many markets (Levitt, 1983 ) in different countries with different cultures. As a matter of necessity, people from other countries must communicate.

The United Nations ( 2015 ) recognizes culture’s contribution to sustainable development and promotes local cultures in development programmes to increase local population involvement. Despite the United Nations’ lofty ideals of integrating culture into development, culture has hindered development at different levels. Interventions meant to enhance development are sometimes met with opposition from some people who feel that such programmes are against their own culture.

Gumperz ( 2001 , p. 216) argues that “all communication is intentional and grounded in inferences that depend upon the assumption of mutual good faith. Culturally specific presuppositions play a key role in inferring what is intended.” Cross-border communications reflect the kaleidoscope of the diverse colours of many cultures, meeting, clashing, and fusing. Like Adler ( 1991 , p. 64) observes, “foreigners see, interpret, and evaluate things differently, and consequently act upon them differently.” Diversities in culture shape interpersonal communication. Yet the basic communication process is the same everywhere. It is in these processes that challenges arise. Therefore, this study seeks to examine how each of these steps can be adapted to enhance cross-cultural communication, especially in today’s digitized era of collapsing cultural boundaries. Barriers to cross-cultural communication can be significantly reduced if the actors in the communication processes become culture literates and competent communicators.

Study objectives

The objectives of this study are

To examine United Nations efforts to integrate culture into sustainable development.

To suggest modifications to each communication process step to improve effective cross-cultural communication.

Literature review

Some authors have tried to link culture, communication, and sustainable goals.

The need to know about people’s culture

There are compelling reasons to learn about other people’s cultures.

Cultural literacies: Difficulties in cross-cultural communication can be reduced when senders of messages understand that the world is broader than their ethnocentric circles. It demands that senders of messages know that what they believe may not always be correct when communicating with receivers of these messages who are from different cultures. Logical reasoning will expect increased exposure to different cultures to increase understanding. When people of different groups communicate frequently, it is anticipated that they should understand each other better. This is what Hirsch ( 1987 ) labels as cultural literacy . In the ordinary course of things, common knowledge destroys mutual suspicion and misinterpretation that often generate conflicts.

To protect the earth: It is essential to point out that at “the most global level, the fate of all people, indeed the fate of the earth, depends upon negotiations among representatives of governments with different cultural assumptions and ways of communicating” (Tannen, 1985 , p. 203). If the world is to be protected, it is necessary to understand other peoples’ cultures who live and interact with us at different fronts and in this same world. The world is still our haven. Nevertheless, Vassiliou et al. ( 1972 ) find that increased exposure can increase people’s mutual negative stereotyping. Tannen ( 1985 , p. 211) remarks that stereotypes of ethnic groups partly develop from the poor impressions that people from other cultures have about the natives because they hold different meanings for both parties. Stereotyping is detrimental to cross-cultural communication, and its dismissal is necessary for any successful cross-cultural exchange.

Spin-offs from globalization: Bokova ( 2013 ) observes that globalization transforms all societies and brings culture to the front. She remarks that communities are increasingly growing diverse and yet interconnected. The spin-offs from globalization open great doors for exchanges, mutual enrichment of persons from different cultures, and pictures of new worlds.

The dynamics of cross-cultural communication

Different cultures emphasize different values. The emphasis on one value by one culture may lead to difficulties in cross-cultural communication with another person who does not see that particular value in the same light, for example, timeliness. It is crucial to note Sapir’s ( 1956 , p. 104) insistence that “every cultural pattern and every single act of social behaviour involves communication in either an explicit or implicit sense.” Even though Hofstede ( 2005 , p. 1) comments that “cultural differences are nuisance at best and often a disaster,” UNESCO ( 1998 , 1999 ) recognizes cultural diversity as an “essential factor of development” and an issue that matters. This makes cultural diversity a blessing rather than a disaster. The various shades of cultural values influence how we behave and communicate with others outside our cultural environment. Our ideals and biases also influence communication.

Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner ( 1997 ) developed a culture model with seven dimensions. They are universalism versus particularism (rules versus relationships); individualism versus communitarianism (the individual versus the group); specific versus diffuse (how far people get involved); neutral versus emotional (how people express emotions) ; achievement versus ascription (how people view status); sequential time versus synchronous time (how people manage time); and internal direction versus outer direction (how people relate to their environment). These cultural models signify how people from these areas communicate. People from different backgrounds may have difficulties communicating as their values may be significantly different. A good communicator must take note of this distinctiveness in values because they impact the communication processes. For example, a person who is particular about upholding written rules may not be interested in knowing who the culprit is before administering sanctions. But the other person interested in maintaining a good relationship with others may re-consider this approach.

Hofstede ( 1980 ) identifies five significant values that may influence cross-cultural communication:

Power distance: This is the gap between the most and the least influential members of society. People from different cultures perceive equality in various ways. The social hierarchy or status determines where individuals are placed. Status is conferred by inheritance or by personal achievement. Some cling to societal classification and its hierarchy of power. Others value and cherish the equality of all people. Yet, other cultures see other people as dependents and somehow inferior beings. A king in an African community is seen as far more powerful and important than his servants, who are expected to pay obeisance to him. Most countries in Europe are egalitarian. Arabic and Asian countries are high on the power index.

Individualism versus collectivism: This explains the extent to which members of a particular culture value being seen first, as individuals or as members of a community. As individuals, they are entirely held accountable for their errors. They are also rewarded as individuals for their exploits. However, in some cultures, the wider community is involved. Suppose a person makes an inglorious error. The whole community where that individual comes from shares in it. The same goes if he wins laurels and awards. The individual does not exist primarily for himself. African, Japanese, Indian, and most Asiatic nations follow the collective approach. A Chinese man has his Guanxi or Guanshi. This is his network of influential and significant contacts that smoothen his business and other activities (Yeung and Tung, 1996 ). He succeeds or fails based on his personal relationships. In other words, the basis of business is friendship. This is clear evidence of collectivism. Most people from America and Europe are individualistic. It must be pointed out that personal values mediate both community and individualistic spirit. Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner’s communitarianism vs. individualism appears very similar to this Hofstede’s individualism/collectivism orientation. The information receiver who values his individuality will be offended if he is seen as just a group member or if his negative performance on the job is discussed openly. The message sender who appreciates his subordinates would send personalized messages and expect their feedback.

Uncertainty avoidance: This shows the degree to which a particular culture is uncomfortable with uncertainties and ambiguities. Some cultures avoid or create worries about how much they disclose to other people. A culture with high uncertainty avoidance scores wants to avoid doubts by telling and knowing the absolute truth in everything. For them, everything should be plainly stated. When situations are not like this, they are offended, worried, and intolerant of other people or groups they feel are hiding facts by not being plain enough. Hofstede and Bond ( 1988 ) write that this trait is very peculiar to western Europeans. This means that people from countries like Greece, Turkey, and Spain are very high on uncertainty avoidance. Communication between people with high or low uncertainties may be hindered. Some people may appear rude and uncouth because of their straightforward ways of talking. Some Africans may see some Americans and people from Europe as too wide-mouthed because they feel they do not use discretion in talking. They say things they may prefer to keep silent about and hide from the public’s ears. On the other hand, some Americans may see some Africans as unnecessarily secretive. Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner’s ( 1997 ) universalism/particularism explains why some cultures insist on applying the rule of law no matter who the offender is.

Masculinity/feminity roles : Hofstede ( 2001 ) defines masculinity as society’s preference for success, heroism, assertiveness, and material rewards for success. Conversely, femininity is seen as the preference for co-operation, diffidence, caring for the weak and quality of life. The male-female contradiction affects communication. Females are expected to be meek homemakers that tend and nurture their family members. Like Sweden and Norway, cultures that favour females do not discriminate between the sexes. Japan and Nigeria have cultures that are predominantly masculine in orientation. Competitive and aggressive females are frowned at and seen as social deviants. In the other cultures where females are more favoured, a man may land in court and face public condemnation for domestic violence. Hofstede ( 1998 ) believes that how different cultures see the male/female roles influence how they treat gender, sexuality, and religion.

Long-time orientations: A particular society accepts some degree of long or short associations. Japanese culture scores high in long-term orientation values, commitments, and loyalty. They respect tradition, and therefore, changes in their society take a longer time to happen. Cultures with low long-term orientation do not value tradition much, nor do they go out of their way to nurture long-standing relationships. Literally, changes occur in rapid succession. There appears to be more attachment to the pursuit of immediate self-satisfaction and simple-minded well-being. Baumeister and Wilson ( 1996 , pp. 322–325) say that meaning comes from a sense of purpose, efficacy, value, and a sense of positive self-worth. Thus, if you communicate with somebody with a short-term orientation, you may think that he is too hasty and intemperate, while he may feel that you are too sluggish and not ready to take immediate action.

Hall ( 1983 ) introduces two other factors:

Time usage: Some cultures are monochronic, while others are polychronic. Monochronic cultures are known for doing one thing at a time. Western Europe is monochronic in time orientation, as illustrated by the familiar adage that says, “There is a time and place for everything!” Persons from this cultural background are very punctual and strictly adhere to plans. They are task-oriented. Polychronic cultures schedule multiple tasks simultaneously, even though there may be distractions and interruptions while completing them. Plans may often change at short notice. Such different time management and usage may constrict effective communication. A London business entrepreneur will find it difficult to understand why his business partner from Nigeria may be thirty minutes late for a scheduled meeting. The answer is in their perception of time. Some Nigerians observe what is referred to as African time , where punctuality is tacitly ignored.

Low and high context: This refers to how much a culture depends on direct or indirect verbal communication. According to Hall ( 1976 ), low context cultures explicitly refer to the topic of discussion. The speaker and his audience know that the words mean exactly what they say. In high context cultures, the meanings of words are drawn from the context of the communication process. The words may never mean what they say. For example, the sentence: I have heard . In the low context culture, it merely means that the listener has used his ears to listen to what the speaker is saying. In the high context culture, the listener knows more than what the speaker is saying and may be planning something unpleasant. Europeans and North Americans have low contexts. African and Asian nations have high contexts.

Vaknin ( 2005 ) brings in another value:

Exogenic and endogenic: This shows how people relate to their environment. Deeply exogenic cultures look outside themselves to make sense of life. Hence, they believe in God and His power to intervene in the affairs of men. Endogenic cultures draw on themselves when searching for the meaning of life. They think they can generate solutions to tackle the problems facing them. While the endogenic person may exert himself to find a solution to a challenge, his exogenic partner may believe that supernatural help will come from somewhere and refuses to do what is needed. Of course, this provides a problematic platform for effective communication.

The United Nations’ sustainable development goals and culture

The United Nations recognizes that culture is implicitly crucial to the achievement of the SDGs. No meaningful development can occur outside any cultural context because every person is born into a culture. To a large extent, our cultural foundations determine what we do and how we see things. Therefore, culture must be integrated into sustainable development strategies. Some specific goals’ targets acknowledge that culture drives development. Sustainable development revolves around economic, social, and environmental objectives for people. These goals are implicitly or explicitly dependent on culture because culture impacts people.

There are 17 Sustainable Development Goals. However, there are four specific ones that refer to culture are:

SDG 4 focuses on quality education

By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development

In other words, quality education is most effective if it responds to a place and the community’s cultural context and exactitudes. This target hinges on education promoting peace, non-violence, and cultural diversity as precursors to sustainable development. Encouraging respect for cultural diversity within acceptable standards facilitates cultural understanding and peace.

SDG 8 focuses on decent work and economic growth

By 2030, devise and implement policies to promote sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products

Strengthening trade in cultural goods and services will provide growth impetus for local, national, and international markets. These will create employment opportunities for people whose work revolves around cultural goods. Cultural tourism generates revenues that improve the economy. In this sense, culture facilitates the community’s well-being and sustainability.

SDG 11 focuses on sustainable cities and communities

Target 11.4

Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage

When our cultural heritage is carefully managed, it attracts sustainable investments in tourism. The local people living where this heritage is domiciled ensure that it is not destroyed and that they themselves will not damage the heritage areas.

SDG 12 focuses on responsible consumption and production

Develop and implement tools to monitor sustainable development impacts for sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products

Several indigenous livelihoods and crafts are built on local knowledge and management of the ecosystem, natural resources, and local materials. If natural resources are depleted, production will be endangered. Local livelihoods that utilize low technology and energy generate less waste and keep their environment free from pollution. In other words, proper management of the ecosystem prevents biodiversity loss, reduces land degradation, and moderates adverse climate change effects. Where there are natural disasters, traditional knowledge already embedded in the people’s culture helps them become resilient.

Theoretical framework

The social construction of reality is hinged on the belief that people make sense of their social world by assembling their knowledge. Scheler ( 1960 ) labels this assemblage the Sociology of Knowledge . Berger and Luckmann ( 1966 , p.15) contend that this “knowledge is concerned with the analysis of the social construction of reality.” Social construction theory builds on peoples’ comprehension of their own life experiences. From there, people make assumptions about what they think life is or should be. Young and Collin ( 2004 ) present that social constructionism pays more attention to society than individuals. Communities determine what they feel is acceptable. What is widely accepted by a particular community may be unacceptable to other people who are not members of this group. Therefore, people see an issue as good or bad based on their group’s description. Thus, what is a reality in Society A may be seen as illegal in Society B . Berger and Luckmann ( 1966 ) claim that people create their own social and cultural worlds and vice versa. According to them, common sense or basic knowledge is sustained through social interactions. These, in turn, reinforce already existing perceptions of reality, leading to routinization and habitualization. Berger and Luckmann ( 1991 ) say that dialogue is the most important means of maintaining, modifying, and reconstructing subjective reality.

Burr ( 2006 ) writes that the four fundamental tenets of social constructionism are: a critical instance towards taken-for-granted knowledge, historical and cultural specificity; knowledge sustained by social processes; and that knowledge and social action go together. This taken-for-granted knowledge is a basic common-sense approach to daily interactions. Historical and cultural specificities look at the peculiar but past monuments that have shaped the particular society. Knowledge is created and sustained by socialization. Good knowledge improves the common good. However, whoever applies the knowledge he has acquired wrongly incurs sanctions. This is why convicted criminals are placed behind bars.

Social constructions exist because people tacitly agree to act as if they do (Pinker, 2002 ). Whatever people see as realities are actually what they have learnt, over long periods, through their interactions with their society’s socialization agents such as the family, schools and churches. Cultural realities are conveyed through a language: the vehicle for communication. Language communicates culture by telling about what is seen, spoken of, or written about. However, groups construct realities based on their cultures. The media construct realities through the production, reproduction, and distribution of messages from which their consumers give meaning to their worlds and model their behaviours.

The method of study

The discourse analysis method of study is adopted for this work. Foucault ( 1971 ) developed the ‘discursive field’ to understand the relationships between language, social institutions, subjectivity, and power. Foucault writes that discourses relate to verbalization at the most basic level. The discursive method explores the construction of meanings in human communication by offering a meaningful interpretation of messages to enhance purposeful communication. Discourse analysis examines how written, or spoken language is used in real-life situations or in the society. Language use affects the creation of meaning; and, therefore, defines the context of communication. Kamalu and Isisanwo ( 2015 ) posit that discourse analysis considers how language is used in social and cultural contexts by examining the relationship between written and spoken words. Discourse analysis aims to understand how and why people use language to achieve the desired effect. The discursive method explores the construction of meanings in human communication by offering a meaningful interpretation of messages to enhance purposeful communication. Gale ( 2010 ) says that meaning is constructed moment by moment. Garfinkel ( 1967 ) explains this construction as the common-sense actions of ordinary people based on their practical considerations and judgments of what they feel are intelligible and accountable to others. According to Keller ( 2011 ), a peoples’ sense of reality combines their routinized interactions and the meanings they attach to objects, actions, and events. It is in this understanding of the natural use of language that some barriers to effective cross-cultural communication can be reduced.

Messages may assume different meanings in different situations for other people. These meanings affect social interactions. They either encourage or discourage further human communication. As Katz ( 1959 ) has written, interpersonal relationships influence communication. To make meaning out of messages and improve human relationships, it is necessary to understand that content and context may not represent the same thing to people in different situations. Waever ( 2004 , p. 198) states that “things do not have meaning in and of themselves, they only become meaningful in discourse.” Since people’s perspectives are different, it becomes extremely difficult to form a rigid basis on specific ideas. Ideas are discussed on their merits. Discursive analysis inspects the ways individuals construct events by evaluating language usage in writing, speech, conversation, or symbolic communication (Edwards, 1997 ; Harre and Gillet, 1994 ). Language is the carrier of culture. According to Van Dijk ( 1995 , p. 12), this approach is used to study descriptive, explanatory, and practical issues in “the attempt to uncover, reveal or disclose what is implicit, hidden or otherwise not immediately obvious in relations of discursively enacted dominance or their underlying ideologies.” The media play fundamental roles in the processes of constructing or reconstructing reality. They can do these because of Aririguzoh’s ( 2004 ) observation that the press impacts the political and socio-cultural sub-systems.

Culture at the international galleries

The affairs of culture came into international prominence at the UNESCO’s World Conference on Cultural Policies held in Mexico in 1982. This conference gave a broad definition of culture to include “the whole complex of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features that characterize a society or social group. It includes not only the arts and letters but also modes of life, the fundamental rights of the human being, value systems, traditions and beliefs” (UNESCO, 1982 , p. 1).

The United Nations World Commission on Culture and Development, led by J. Perez de Cuellar, published our Creative Diversity’s Landmark Report (UNESCO, 1995 ). This report points out the great importance of incorporating culture into development. Although the Commission recognizes cultural diversities, it sees them as the actual vehicles driving creativity and innovation. During the World Decade on Culture and Development (1988–1998), UNESCO stepped up again to campaign for greater recognition of culture’s contribution to national and international development policies. In 1998, Stockholm hosted an Inter-governmental Conference on Cultural Policies for Development. Its Action Plan on Cultural Policies for Development reaffirmed the correlation between culture and development (UNESCO, 1998 ). In 1999, UNESCO and the World Bank held the Inter-governmental Conference, Culture Counts , in Florence. Here, ‘cultural capital’ was emphasized as the tool for sustainable development and economic growth (UNESCO, 1999 ).

The United Nations General Assembly adopted the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document . Here, cultural diversity was explicitly admitted as a contributor to the enrichment of humankind. The United Nations General Assembly Resolutions on Culture and Development adopted in 2010 and 2011 (65/166 and 66/208) recognize culture as an “essential component of human development” and “an important factor in the fight against poverty, providing for economic growth and ownership of the development processes.” These resolutions called for the mainstreaming of culture into development policies at all levels. The UN System Task Team on the Post 2015 Development Agenda issued a report, Realizing the Future We Want for All ( 2012 , p. ii), with a direct charge that culture has a clear role to play in the “transformative change needed for a rights-based, equitable and sustainable process of global development.” Paragraph 71 of the report declares:

It is critical to promote equitable change that ensures people’s ability to choose their value systems in peace, thereby allowing for full participation and empowerment. Communities and individuals must be able to create and practice their own culture and enjoy that of others free from fear. This will require, inter alia, respect for cultural diversity, safeguarding cultural and natural heritage, fostering cultural institutions, strengthening cultural and creative industries, and promoting cultural tourism (p. 33).

In 2005, the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions member states agreed that cultural diversity “increases the range of choices and nurtures human capacities and values. Therefore, it is a mainspring for sustainable development for communities, peoples and nations” (UNESCO, 2005 , p. 1). The Convention reiterated the importance of the link between culture and development. UNESCO also steers an International Fund for Cultural Diversity to promote sustainable development and poverty reduction among the developing and least developed countries that are parties to the Convention.

UN Resolution 2347 of 2017 focuses exclusively on protecting cultural heritage and its necessity for peace and security. This Resolution brings a thorough awareness of culture’s role as a source of stability, inclusion, driver of reconciliation, and resilience. This Resolution reinforces Resolution 2199, adopted in February 2015, partly to fight against international terrorism financing and prohibit the illicit trafficking of cultural goods from Iraq and Syria.

Communication processes for overcoming difficulties in cross-cultural communication

The primary risk in cross-cultural communication is distortion, which creates misunderstanding or even misrepresentation of the conveyed information. Baumgratz ( 1990 , pp. 161–168) shares the opinion that relevant cultural dimensions of what he calls a social communication situation should be mapped out for individuals or groups who are from different nations or cultural origins but who have realized the need to contribute to the achievement of social, institutional, organizational, group, and personal aims. The tactics to overcome difficulties in cross-cultural communication lie in the communication processes. Any of the steps can become a barrier since culture influences the behaviour of both senders and receivers of messages. Barriers impede communication by distorting, blocking, or creating misunderstandings. Hence, it is necessary to create an enabling environment that will make communicating easier. Each of the communication steps can be strategized to enhance communication.

He is the source or initiator of the message. He can be a person or an organization. If the sender is a person, Malec ( 2018 ) refers to him as the carrier of intangible culture and the creator of the tangible ones. Messages are conveyed through spoken or written words. Nevertheless, messages can also be non-verbal. The encoding includes selecting words, symbols, or gestures in composing a message. The sender should encrypt, transfer meaning, or package his messages in ways that the receivers can access them. He should use symbols that the receiver would comprehend. The first thing he should do is use a language that his receiver understands. For example, it is useless to send a message written in English to another person who only understands French. Not only is the effort wasted, but it might also generate hostility. In Nigeria, Mexican soaps are freely watched. However, their producers avoided the obvious language challenge by dubbing in English voice-overs.

Words mean different things in different languages. For example, a British boss would answer yes to a question. However, his American subordinate would answer, yeah . The boss would think that he is disrespectful and impolite. Meanwhile, the American employee would be bewildered by the boss’s apparent coldness. British people use words that have different meanings from their American counterparts. For example, the word, pant , means underwear to a Briton but a pair of trousers to an American. The Englishman may still run into trouble with other nationals because his words have different meanings to these listeners. For example, the English phrase fart means a different thing among the Danish. For them, the word means speed ! The English word gift means poison in German. If an Englishman calls somebody a brat , his Russian friend will conclude that he is calling him his brother , which is what the word means in his language. Igbo children of south-eastern Nigeria call the hawk leke . But for the Yorubas in the southwest, this is the name given to a male child.

The sender, too, must know that even body language may mean different things. He should not assume that non-verbal messages mean the same in every part of the world. In Japan, nodding the head up and down means disagreement. In Nigeria, it means the opposite. Even though his own culture invariably influences the message’s sender, he should understand that his message is intended for a cross-cultural audience. He must also realize that the contents are no longer meant for ethnic communities defined by geographical locations but for an audience connected by frequent interactions that are not necessarily in the same physical place. A message sender that values esprit de corps will incorporate this into his messages by telling them that the laurel does not go to any person in particular but to the winning team. He thus encourages everybody to join in to win, not as individuals but as members of a group. If he is high on doubt avoidance, he makes his messages very direct and unambiguous and leaves no room for misinterpretation. However, a male sender who wants to assert his masculinity may wish to sound harsh. The sender who regularly attends church services may unconsciously put some words of Scripture in his messages because of his exogenic roots. The sender with monochronic orientation will send one message and expect the task to be completed as scheduled. His linear cultural background will be offended if the result is the contrary. Similarly, the sender who places a high value on rules and regulations would send messages of punishment to those who break them but reward those who keep them without minding his relationships with them. An effective sender of messages to a cross-cultural society should state his ideas clearly, offer explanations when needed, or even repeat the whole communication process if he does not get the appropriate feedback.

This is the information content the sender wants to share with his receivers. These include stories, pictures, or advertisements. He should carefully avoid lurid and offensive content. A French man may see nothing wrong in his wife wearing a very skimpy bikini and other men ogling at her at a public beach. His counterpart from Saudi Arabia will be upset if other men leer at his wife. In addition, the wife would be sanctioned for dressing improperly and appearing in public. If a person has a message to share with others from a different cultural background, he should be careful. His listeners may not isolate his statement as being distinct from his personality.

Societies with high context culture usually consider the messages they send or receive before interpreting them. Messages are hardly delivered straightforwardly. The message is in the associated meanings attached to the pictures and symbols. Thus, those outside that community find it very difficult to understand the meaning of the messages. In low-context communication, the message is the information in words. The words mean what they say. However, a corporate sender of messages, for example, the head of the Human Resources Department of a multi-cultural company interested in building team spirit, may organize informal chit-chats and get-togethers to break the proverbial ice as well as create a convivial atmosphere where people can relate. The message he is passing across is simple: let colleagues relax, relate, and work together as team members irrespective of where they come from. All of these are communicative actions.

The channel’s work is to provide a passage for the sender to guide his message to the receiver. While face-to-face communication is ideal for intimate and close group conversations, it is impossible to talk to everybody simultaneously. Different channels of passing across the same message may be used. For example, the same message may be passed through radio, adapted for television, put online, or printed in newsletters, newspapers, and magazines. The hope is that people who missed the message on one channel may see it on another somewhere else. A pronounced media culture will hasten cross-cultural communication. Many people consume media content. However, these consumers are expected to be media literates. Aririguzoh ( 2007 , p. 144) writes that:

media literacy is the systematic study of the media and their operations in our socio-political systems as well as their contributions to the development and maintenance of culture. It is the information and communication skill that is needed to make citizens more competent. It is the ability to read what the print media offer, see what the visual media present, and hear what the aural media announce. It is a response to the changing nature of information in our modern society.

Official messages should be passed through defined routes and are best written. This would close avenues of possible denials by others if the same message were passed across verbally. It could be difficult to misinterpret the contents of a written document. Written documents have archival values. As much as possible, rumours should be stamped out. A good manager should single out regular gossips in a multi-cultural organization for special attention. Equally, an effective manager heading widely dispersed employees can co-ordinate their activities using communication technologies with teleconferencing features. Aririguzoh ( 2007 , p. 45) notes, “information and communication technologies have transformed the range and speed of dispersing information and of communicating. Today, the whole world lies a click away!”

The media of communication are shaped by the culture of the people who produce them. What they carry as contents and the form they assume are defined by the culture of the sender. In low-context societies, it is common for messages to be written. In high context societies, it is common for statements to be verbal. Importantly, Aririguzoh ( 2013 , pp. 119–120) points out that “… the mass media can effectively be deployed to provide pieces of information that enhance communication, build understanding and strengthen relationships in our rapidly changing environment dictated by the current pace of globalization. The mass media assiduously homogenize tastes, styles, and points of view among many consumers of its products across the globe. They have effectively helped in fading away national distinctions and growing mass uniformity as they create, distribute and transmit the same entertainment, news, and information to millions of people in different nations.”

The receiver is the person the sender directs his message to. In a workplace, the receiver needs the message or information to do his job. The receiver decodes or tries to understand the meaning of the sender’s message by breaking it down into symbols to give the proper feedback. If the message is verbal, the receiver has to listen actively. The message receiver must understand a message based on his existing orientations shaped by his own culture. Even the messages that he picks are selected to conform to his existing preconceptions.

Oyserman et al. ( 2002 ) make an interesting discovery: that receivers from different cultures interpret the message senders’ mannerisms. For an American, a speaker talking very quickly is seen as telling the uncensored truth. In other words, the speaker who talks too slowly implicates himself as a liar! However, for the Koreans, slow speech denotes careful consideration of others. In some cultures, particularly in Asia, the receiver is responsible for effective communication. Kobayashi and Noguchi ( 2001 ) claim that he must become an expert at “understanding without words.” Miyahara ( 2004 , p. 286) emphasizes that even children literarily learn to read other people’s minds by evaluating the subtle cues in their messages and then improvising to display the expected and appropriate social behaviour and communication. Gestures involve the movements of the hands and head of the sender. The receiver clearly understands these body movements. As painted by Sapir ( 1927 , p. 556), “we respond to gestures with an extreme alertness and, one might almost say, in accordance with an elaborate and secret code that is written nowhere, known by none, and understood by all.”

Receivers who value individualism appreciate personal freedom, believe that they can make their own decisions, and respect their performance. Those who prefer communitarianism would prefer group applause and loyalty. A monochromatic receiver would start and finish a task before starting another one. He would be offended when colleagues do not meet deadlines, are late to appointments, and do not keep rigid schedules. His co-worker, who synchronizes his time, develops a flexible working schedule to work at two or more tasks.

This is the final process. Ordinarily, the sender wants a response to determine if the message he sent out has been received and understood. Acknowledging a message does not indicate a clear understanding of its contents. Feedback can be positive or negative. Positive feedback arises when the receiver interprets the message correctly and does what the sender wants. Negative feedback comes when messages are incorrectly interpreted, and the receiver does not do what the sender of the information has intended him to do. Cross-cultural communication recognizes that people come from different backgrounds. Therefore, feedback on diverse messages would be different. A sensitive communicator would be careful how he designs his messages for a heterogeneous audience so that he can elicit the desired feedback.

It must be emphasized that no culture is superior to another as each culture meets the needs of those who subscribe to it. To a large extent, our culture influences our behaviours and expectations from other people. Although there are noticeable similarities and differences, what separates one culture from another is its emphasis on specific values. As the United Nations has affirmed, there is diversity in cultures. These diversities add colour and meaning to human existence. This suggests that particular policies should be carved out to attend to specific locations and supports Satterthwaite’s ( 2014 ) proposition that local actors should be empowered to help achieve the SDGs. What the local populace in one community may appreciate may be frowned upon and even be fought against by residents in another place. As Hossain and Ali ( 2014 ) point out, individuals constitute the societies where they live and work. While Bevir ( 1996 ) describes this relationship as that of mutual dependence, he recognizes that people are influenced by their particular social structures and therefore do not go against them. Bevir believes that social systems exist for individuals.

Societies are built on shared values, norms and beliefs. These, in turn, have profound effects on individuals. Society’s culture affects individuals while the individuals create and shape the society, including initiating sustainable development. Development rests on the shoulders of men. Thus, culture influences the ways individuals behave and communicate. The effective communicator must actively recognize these elements and work them into communication practices. As Renn et al. ( 1997 , p. 218) point out, “sustainable practices can be initiated or encouraged by governmental regulation and economic incentives. A major element to promote sustainability will be, however, the exploration and organization of discursive processes between and among different actors.”

To achieve the United Nations sustainable goals, the competent communicator has to recognize that the culture of the actors in a communication process is the basic foundation for effective communication. For example, while one individual may discuss issues face-to-face and is not afraid to express his feelings candidly, another person may not be so direct. He may even involve third parties to mediate in solving a problem. Either way, their approaches are defined by their cultural backgrounds. It may be counterproductive to assume that either of these approaches is the best. This assertion is supported by the study of Stanton ( 2020 ), who explored intercultural communication between African American managers and Hispanic workers who speak English as a second language. He finds managers that follow culturally sensitive communication strategies getting more work done. Cartwright ( 2020 ) also observes that intercultural competence and recognition of cultural differences in East and Central Europe are foundation pillars for business success. This lends credence to Ruben and Gigliotti ( 2016 ) observation that communication with people from different cultures reduces the barriers associated with intercultural communication and enhances the communication process.

Irrespective of our ethnicities, people want to communicate, understand, appreciate, and be respected by others. Effective communication is the foundation of good human relationships among team members, whether their cultural backgrounds differ or not. Good feedback is achieved when both the sender and receiver of messages create common meanings. This is what discourse is all about. Messages must be meaningful, meaningfully constructed and meaningfully interpreted. Georgiou ( 2011 ) labels this the communicative competence : acknowledgement of the intercultural dimension of foreign language education and successful intercultural interactions that assume non-prejudiced attitudes, tolerance and understanding of other cultures, and cultural self-awareness of the person communicating. An efficient communicator must understand that culture shapes people, and the people then shape society. In other words, communication shapes the world. Therefore, appropriately chosen communication strategies help blend the different cultures.

According to Bokova ( 2013 ), there is “renewed aspirations for equality and respect, for tolerance and mutual understanding, especially between peoples of different cultures.” This means that if all parties respect other team members’ cultures, a clement work environment is inevitable. Cultural literacy creates more tolerant and peaceful work environments. Achieving this starts with a re-examination of the whole communication process. The crux of cross-cultural communication is developing effective ways to appreciate the culture of others involved in the acts of communication. Understanding these differences provides the context for an enhanced understanding of the values and behaviours of others. Reconciling these differences confers competitive advantages to those who communicate effectively. The media must provide the links between senders and receivers of messages in the context of their socio-cultural environments.

The United Nations appreciates the distinctiveness in cultures and has incorporated it as a significant factor in achieving sustainable development goals. This global body has produced different documents championing this. Every development takes place in an environment of culture. The heart of sustainable development is the man. The SDGs will be more meaningful and easily achievable by recognizing that actions should be both locally and culturally relevant. Cultural differences can be effectively managed if senders and receivers of messages understand that culture shapes how people communicate and, by extension, the relationship with other people who may not necessarily be from their tribal communities. Breaking down the barriers to cross-cultural communication lies in understanding these distinct differences and consciously incorporating them into the communication processes to enhance communication competencies.

Data availability

All data analysed are contained in the paper.

Adler N (1991). International dimensions of organizational behavior, 2nd edn. Pws-Kent Publishing Company

Aririguzoh S (2004) How the press impinges on the political and socio-cultural sub-systems. Nsukka J Humanit 14:137–147. http://www.unnfacultyofarts.com/download.php?download_file=UFAJH192.pdf

Aririguzoh S (2007) Media literacy and the role of English language in Nigeria. Int J Commun 6:144–160

Google Scholar

Aririguzoh S (2013) Human integration in globalization: the communication imperative. Niger J Soc Sci 9(2):118–141

Barth F (1969) Introduction. In: Barth F (ed.) Ethnic groups and boundaries: the social organization of culture difference. Little, Brown & Company, pp. 9–30

Baumeister R, Wilson B (1996) Life stories and the four needs for meaning. Psychol Inq 7(4):322–325

Article Google Scholar

Baumgratz G (1990) Personlichkeitsentwicklung und Fremdsprachenerwerb. Transnationale Kommunikationsfthigkeit im Franzosischunterricht (Personality development and foreign language acquisition: transnational communication skills in French lessons). Schoningh

Berger P, Luckmann T (1966) The social construction of reality: a treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Penguin Books Ltd

Berger P, Luckmann T (1991) The social construction of reality. Penguin Books.

Bevir M (1996) The individual and society. Political Stud 44(1):102–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00759.x

Bokova I (2013) The power of culture for development. http://en.unesco.org/post2015/sites/post2015/files/The%20Power%20of%20e%20fCulturor%20Development.pdf

Bokova I (2010) 2010 International year for the rapprochement of culture: message from Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO https://www.un.org/en/events/iyrc2010/message.shtml

Burr V (2006) An introduction to social constructionism. Routledge, Taylor & Francis e-Library

Cartwright CT (2020) Understanding global leadership in eastern and central Europe: the impacts of culture and intercultural competence. In: Warter I, Warter L (eds.) Understanding national culture and ethics in organisations. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp. 63–74

Causadias JM (2020) What is culture? Systems of people, places, and practices. Appl Dev Sci24(4):310–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2020.1789360

Comaroff J, Comaroff J (2009) Ethnicity , inc. University of Chicago Press

De Beukelaer C, Freita R (2015) Culture and sustainable development: beyond the diversity of cultural expressions. In: De Beukelaer C, Pyykkönen MI, Singh JP (eds.) Globalization, culture, and development: the UNESCO convention on cultural diversity. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 203–221

Dessein J, Soini K, Fairclough G, Horlings L (2015) Culture in, for and as sustainable development. Conclusions of COST ACTION IS1007 investigating cultural sustainability. European Cooperation in Science and Technology, University of Jyvaskyla https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3380.7844

Edwards D (1997) Discourse and cognition. Sage

Field L (2008) Abalone tales: Collaborative explorations of sovereignty and identity in native California. Duke University Press Books

Foucault M (1971). The order of discourse. In: Young R (ed.) Untying the text: a post-structuralist reader. Routledge and Kegan Paul Limited

Gale J (2010) Discursive analysis: a research approach for studying the moment-to-moment construction of meaning in systemic practice. Hum Syst21(2):7–37

García-Carbonell A, Rising B (2006) Culture and communication. College of Management Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, pp. 23–40

Garfinkel H (1967) Studies in ethnomethodology. Prentice-Hall

Geertz C (1973) The interpretation of cultures. Basic Books

Georgiou M (2011) Intercultural competence in foreign language teaching and learning: action inquiry in a Cypriot tertiary institution. Doctoral Thesis, University of Nottingham

Guiso L, Paola S, Luigi Z (2006) Does culture affect economic outcomes?. J Econ Perspect20(2):23–48. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.20.2.23

Gumperz JJ (2001) Interactional sociolinguistics: a personal perspective. In: Schiffrin D, Tannen D, Hamilton HE (eds.) The handbook of discourse analysis. Blackwell Publishers Ltd., pp. 215–228

Hall E (1976) Beyond culture. Doubleday