MedicalCRITERIA.com

Unifying concepts, modified medical research council (mmrc) dyspnea scale.

The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale is recommended for conducting assessments of dyspnea and disability and functions as an indicator of exacerbation.

The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale

| Grade 0 | I only get breathless with strenuous exercise |

| Grade 1 | I get short of breath when hurrying on level ground or walking up a slight hill |

| Grade 2 | On level ground, I walk slower than people of the same age because of breathlessness, or I have to stop for breath when walking at my own pace on the level |

| Grade 3 | I stop for breath after walking about 100 yards or after a few minutes on level ground |

| Grade 4 | I am too breathless to leave the house or I am breathless when dressing |

An mMRC scale grade of 3 have a significantly poorer prognosis and that the mMRC scale can be used to predict hospitalization and exacerbation.

References:

- Natori H, Kawayama T, Suetomo M, Kinoshita T, Matsuoka M, Matsunaga K, Okamoto M, Hoshino T. Evaluation of the Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale for Predicting Hospitalization and Exacerbation in Japanese Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Intern Med. 2016;55(1):15-24. [Medline]

- Launois C, Barbe C, Bertin E, Nardi J, Perotin JM, Dury S, Lebargy F, Deslee G. The modified Medical Research Council scale for the assessment of dyspnea in daily living in obesity: a pilot study. BMC Pulm Med. 2012 Oct 1;12:61. [Medline]

Created Feb 10, 2021.

Related Posts

The muscle scale grades muscle power on a scale of 0 to 5 in relation…

The Hachinski ischemic score (HIS) is known to be a simple clinical tool, currently used…

The Karnofsky Performance Status Scale (KPS) was designed to measure the level of patient activity…

Instructions: This scale is intended to record your own assessment of any sleep difficulty you…

The FAST scale is a functional scale designed to evaluate patients at the more moderate-severe…

Users Online

Medical disclaimer, recent posts.

- Rosemont Criteria for Chronic Pancreatitis

- Diagnostic Criteria for Idiopathic Multicentric Castleman Disease (iMCD)

- Diagnostic Criteria of Lipedema

- Diagnostic Criteria of Acute Adrenal Insufficiency

- Diagnostic Criteria for Peripartum Cardiomyopathy

- About Us (1)

- Allergy (3)

- Anesthesiology (5)

- Cardiology (55)

- Critical Care (17)

- Dermatology (7)

- Diabetes (14)

- Endocrinology and Metabolism (21)

- Epidemiology (6)

- Family Practice (7)

- Gastroenterology (64)

- Hematology (41)

- Immumology (6)

- Infectious Disease (44)

- Internal Medicine (1)

- Nephrology (17)

- Neurology (79)

- Nutrition (30)

- Obstetrics & Gynecology (21)

- Oncology (13)

- Ophthalmology (4)

- Orthopedic (5)

- Otolaryngology (5)

- Pathologic (1)

- Pediatrics (14)

- Pharmacology (3)

- Physical Therapists (7)

- Psychiatry (51)

- Pulmonary (23)

- Radiology (5)

- Rheumatology (52)

- Surgery (8)

- Urology (5)

Copyright by MedicalCriteria.com

Last Updated on 21 June, 2021 by Guillermo Firman

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Measuring Shortness of Breath (Dyspnea) in COPD

How the Perception of Disability Directs Treatment

Dyspnea is the medical term used to describe shortness of breath, a symptom considered central to all forms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) including emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

As COPD is both a progressive and non-reversible, the severity of dyspnea plays a key role in determining both the stage of the disease and the appropriate medical treatment.

Challenges in Diagnosis

From a clinical standpoint, the challenge of diagnosing dyspnea is that it is very subjective. While spirometry tests (which measures lung capacity) and pulse oximetry (which measures oxygen levels in the blood) may show that two people have the same level of breathing impairment, one may feel completely winded after activity while the other may be just fine.

Ultimately, a person's perception of dyspnea is important as it helps ensure the person is neither undertreated nor overtreated and that the prescribed therapy, when needed, will improve the person's quality of life rather than take from it.

To this end, pulmonologists will use a tool called the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale to establish how much an individual's shortness of breath causes real-world disability.

How the Assessment Is Performed

The process of measuring dyspnea is similar to tests used to measure pain perception in persons with chronic pain. Rather than defining dyspnea in terms of lung capacity, the mMRC scale will rate the sensation of dyspnea as the person perceives it.

The severity of dyspnea is rated on a scale of 0 to 4, the value of which will direct both the diagnosis and treatment plan.

| Grade | Description of Breathlessness |

|---|---|

| 0 | "I only get breathless with strenuous exercise." |

| 1 | "I get short of breath when hurrying on level ground or walking up a slight hill." |

| 2 | "On level ground, I walk slower than people of the same age because of breathlessness or have to stop for breath when walking at my own pace." |

| 3 | "I stop for breath after walking about 100 yards or after a few minutes on level ground." |

| 4 | "I am too breathless to leave the house, or I am breathless when dressing." |

Role of the MMRC Dyspnea Scale

The mMRC dyspnea scale has proven valuable in the field of pulmonology as it affords doctors and researchers the mean to:

- Assess the effectiveness of treatment on an individual basis

- Compare the effectiveness of a treatment within a population

- Predict survival times and rates

From a clinical viewpoint, the mMRC scale correlates fairly well to such objective measures as pulmonary function tests and walk tests . Moreover, the values tend to be stable over time, meaning that they are far less prone to subjective variability that one might assume.

Using the BODE Index to Predict Survival

The mMRC dyspnea scale is used to calculate the BODE index , a tool which helps estimate the survival times of people living with COPD.

The BODE Index is comprised of a person's body mass index ("B"), airway obstruction ("O"), dyspnea ("D"), and exercise tolerance ("E"). Each of these components is graded on a scale of either 0 to 1 or 0 to 3, the numbers of which are then tabulated for a final value.

The final value—ranging from as low as 0 to as high as 10—provides doctors a percentage of how likely a person is to survive for four years. The final BODE tabulation is described as follows:

- 0 to 2 points: 80 percent likelihood of survival

- 3 to 4 points: 67 percent likelihood of survival

- 5 of 6 points: 57 percent likelihood of survival

- 7 to 10 points: 18 percent likelihood of survival

The BODE values, whether large or small, are not set in stone. Changes to lifestyle and improved treatment adherence can improve long-term outcomes, sometimes dramatically. These include things like quitting smoking , improving your diet and engaging in appropriate exercise to improve your respiratory capacity.

In the end, the numbers are simply a snapshot of current health, not a prediction of your mortality. Ultimately, the lifestyle choices you make can play a significant role in determining whether the odds are against you or in your favor.

Janssens T, De peuter S, Stans L, et al. Dyspnea perception in COPD: association between anxiety, dyspnea-related fear, and dyspnea in a pulmonary rehabilitation program . Chest. 2011;140(3):618-625. doi:10.1378/chest.10-3257

Manali ED, Lyberopoulos P, Triantafillidou C, et al. MRC chronic Dyspnea Scale: Relationships with cardiopulmonary exercise testing and 6-minute walk test in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients: a prospective study . BMC Pulm Med . 2010;10:32. doi:10.1186/1471-2466-10-32

Esteban C, Quintana JM, Moraza J, et al. BODE-Index vs HADO-score in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Which one to use in general practice? . BMC Med . 2010;8:28. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-28

Chhabra, S., Gupta, A., and Khuma, M. " Evaluation of Three Scales of Dyspnea in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. " Annals of Thoracic Medicine. 2009; 4(3):128-32. DOI: 10.4103/1817-1737.53351 .

Perez, T.; Burgel, P.; Paillasseur, J.; et al. " Modified Medical Research Council scale vs Baseline Dyspnea Index to Evaluate Dyspnea in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. " International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease . 2015; 10:1663-72. DOI: 10.2147/COPD.S82408 .

By Deborah Leader, RN Deborah Leader RN, PHN, is a registered nurse and medical writer who focuses on COPD.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Disability assessment

- Assessment for capacity to work

- Assessment of functional capability

- Browse content in Fitness for work

- Civil service, central government, and education establishments

- Construction industry

- Emergency Medical Services

- Fire and rescue service

- Healthcare workers

- Hyperbaric medicine

- Military - Other

- Military - Fitness for Work

- Military - Mental Health

- Oil and gas industry

- Police service

- Rail and Roads

- Remote medicine

- Telecommunications industry

- The disabled worker

- The older worker

- The young worker

- Travel medicine

- Women at work

- Browse content in Framework for practice

- Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 and associated regulations

- Health information and reporting

- Ill health retirement

- Questionnaire Reviews

- Browse content in Occupational Medicine

- Blood borne viruses and other immune disorders

- Dermatological disorders

- Endocrine disorders

- Gastrointestinal and liver disorders

- Gynaecology

- Haematological disorders

- Mental health

- Neurological disorders

- Occupational cancers

- Opthalmology

- Renal and urological disorders

- Respiratory Disorders

- Rheumatological disorders

- Browse content in Rehabilitation

- Chronic disease

- Mental health rehabilitation

- Motivation for work

- Physical health rehabilitation

- Browse content in Workplace hazard and risk

- Biological/occupational infections

- Dusts and particles

- Occupational stress

- Post-traumatic stress

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Themed and Special Issues

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Books for Review

- Become a Reviewer

- About Occupational Medicine

- About the Society of Occupational Medicine

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Permissions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Scoring and interpretation, clinical usage and performance, modifications, comparisons.

- < Previous

The MRC breathlessness scale

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Nerys Williams, The MRC breathlessness scale, Occupational Medicine , Volume 67, Issue 6, August 2017, Pages 496–497, https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqx086

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The symptom of breathlessness is a common feature of both respiratory and cardiac problems and is subjective and difficult to quantify thereby causing problems for researchers wanting to assess interventions and compare treatments. In order to develop a measure of the effect of breathlessness on everyday life, data which had been collected from studies on pneumoconiosis in Welsh coal miners were used to develop a series of questions about the disability resulting from breathlessness [ 1 ]. This was then developed into the familiar Medical Research Council (MRC) breathlessness/dyspnoea scale and was published in 1959 [ 2 ]. A respiratory questionnaire has also been developed by the MRC and is published along with guidance for interviewers, the latest version being published in 1986 [ 3 ]. The respiratory questionnaire was specifically designed for large epidemiological studies of between 100 and 1000 patients and is explicitly not for individual use [ 3 ].

Occupational Medicine last reviewed the MRC breathlessness scale including its historical development 8 years ago [ 4 ]. Since then it has continued to be extensively used in clinical research and practice, often in combination with other instruments which measure breathlessness. In its modified form, the questionnaire has more recently been used beyond respiratory conditions to include other system disorders such as obesity [ 5 ].

The scale on the original MRC dyspnoea scale is very simple, consisting of just five items containing statements about the impact of breathlessness on the individual and leading to a grade from 1 to 5. It can be self-administered or with a slight change in format of questions, delivered by a researcher or clinician. Either way it takes seconds to complete.

In the self-administered format, the patient selects the option that best describes their breathlessness as it affects their function. It does not grade breathlessness itself but the functional impact of breathlessness and perceived limitations that result. The grading is outlined in Table 1 .

MRC dyspnoea scale (used with permission of the MRC)

| Grade . | Degree of breathlessness related to activity . |

|---|---|

| 1 | Not troubled by breathless except on strenuous exercise |

| 2 | Short of breath when hurrying on a level or when walking up a slight hill |

| 3 | Walks slower than most people on the level, stops after a mile or so, or stops after 15 min walking at own pace |

| 4 | Stops for breath after walking 100 yards, or after a few minutes on level ground |

| 5 | Too breathless to leave the house, or breathless when dressing/undressing |

| Grade . | Degree of breathlessness related to activity . |

|---|---|

| 1 | Not troubled by breathless except on strenuous exercise |

| 2 | Short of breath when hurrying on a level or when walking up a slight hill |

| 3 | Walks slower than most people on the level, stops after a mile or so, or stops after 15 min walking at own pace |

| 4 | Stops for breath after walking 100 yards, or after a few minutes on level ground |

| 5 | Too breathless to leave the house, or breathless when dressing/undressing |

Adapted from Fletcher [1].

The use of the MRC breathlessness scale either on its own or in combination with other measures is widespread across the world in many scientific studies. The instrument allows stratification of populations to assess the effectiveness of interventions. An example is in pulmonary rehabilitation.

Researchers such as Bestall et al . [ 6 ] have explored its validity in this context. They found that the scale was a simple and valid method which could be used to categorize patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in terms of their disability and it could be used to complement forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV 1 ) in the classification of the severity of disease.

While much of the recent use of the MRC dyspnoea scale is in COPD patients, its performance in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [ 7 ] and sarcoidosis [ 8 ] has also been documented. The original MRC breathlessness scale is currently recommended for use in the diagnosis of patients with COPD by government bodies such as NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in England) [ 9 ] and the modified version is a key feature of the GOLD 2011 (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Airways Disease) recommend ations on assessment. In a study by Jones et al . [ 10 ], the modified MRC (mMRC) dyspnoea scale showed a clear relationship with health status scores and even low mMRC scores were associated with health impairment ( Table 2 ).

The mMRC scale

| Grade . | Description of breathlessness . |

|---|---|

| Grade 0 | I only get breathless with strenuous exercise |

| Grade 1 | I get short of breath when hurrying on level ground or walking up a slight hill |

| Grade 2 | On level ground, I walk slower than people of the same age because of breathlessness, or I have to stop for breath when walking at my own pace on the level |

| Grade 3 | I stop for breath after walking about 100 yards or after a few minutes on level ground |

| Grade 4 | I am too breathless to leave the house or I am breathless when dressing |

| Grade . | Description of breathlessness . |

|---|---|

| Grade 0 | I only get breathless with strenuous exercise |

| Grade 1 | I get short of breath when hurrying on level ground or walking up a slight hill |

| Grade 2 | On level ground, I walk slower than people of the same age because of breathlessness, or I have to stop for breath when walking at my own pace on the level |

| Grade 3 | I stop for breath after walking about 100 yards or after a few minutes on level ground |

| Grade 4 | I am too breathless to leave the house or I am breathless when dressing |

The mMRC breathlessness scale ranges from grade 0 to 4. It is very similar to the original version and is now widely used in studies.

It should be noted that the MRC clearly states on its website that it is unable to give permission for use of any modified version of the scale (including therefore, the mMRC scale) [ 3 ]. Use of the MRC questionnaire is free but should be acknowledged.

The MRC and mMRC scales are just two of many scales used in respiratory research. Chhabra et al . [ 11 ] compared three dyspnoea scales in COPD and found that the grades of dyspnoea on the mMRC were moderately interrelated with the Baseline Dyspnoea Index (BDI) and the Oxygen Cost Diagram (OCD) but the mMRC did not correlate with physiological impairment while the other two instruments did. This study, however, only considered patients with three of the five MRC grades. Other work by Camargo et al . [ 12 ] showed correlation with other instruments. In clinical studies, as opposed to clinical practice, some researchers, usually in the USA, tend to rely on the BDI but they need to be aware that although related to similar factors causing breathlessness, the BDI and mMRC score report the dyspnoea intensity in COPD patients differently and are not interchangeable [ 13 ]. The mMRC scale is often used with the Borg scale of perceived exertion [ 14 ] and the use of several scales including mMRC dyspnoea scale to assess COPD disability [ 14 ], evaluate quality of life [ 15 ] and provide tailored therapy [ 16 ] has been supported across the world [ 4 , 15 , 16 ].

Fletcher CM . The clinical diagnosis of pulmonary emphysema—an experimental study . Proc R Soc Med 1952 ; 45 : 577 – 584 .

Google Scholar

Fletcher CM , Elmes PC , Fairbairn AS , Wood CH . The significance of respiratory symptoms and the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis in a working population . Br Med J 1959 ; 2 : 257 – 266 .

MRC . https://www.mrc.ac.uk/research/facilities-and-resources-for-researchers/mrc-scales/mrc-dyspnoea-scale-mrc-breathlessness-scale/ (23 February 2017, date last accessed).

Stenton C . The MRC breathlessness scale . Occup Med (Lond) 2008 ; 58 : 226 – 227 .

Launois C , Barbe C , Bertin E et al. The modified Medical Research Council scale for the assessment of dyspnea in daily living in obesity: a pilot study . BMC Pulm Med 2012 ; 12 : 61 .

Bestall JC , Paul EA , Garrod R , Garnham R , Jones PW , Wedzicha JA . Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease . Thorax 1999 ; 54 : 581 – 586 .

Manali ED , Lyberopoulos P , Triantafillidou C et al. MRC chronic dyspnea scale: relationships with cardiopulmonary exercise testing and 6-minute walk test in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients: a prospective study . BMC Pulm Med 2010 ; 10 : 32 .

Marcellis R , Van der Veeke M , Mesters I et al. Does physical training reduce fatigue in sarcoidosis? Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2015 ; 32 : 53 – 62 .

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg101/chapter/1- Guidance ( 23 February 2017 , date last accessed).

Jones PW , Adamek L , NadeauG et al. Comparisons of health status scores with MRC grades in COPD: implications for the GOLD 2011 classification . Eur Respir J 2013 ; 42 : 647 – 654 .

Chhabra SK , Gupta AK , Khuma MZ . Evaluation of three scales of dyspnea in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease . Ann Thorac Med 2009 ; 4 : 128 – 132 .

Camargo LA , Pereira CA . Dyspnea in COPD: beyond the modified Medical Research Council scale . J Bras Pneumol 2010 ; 36 : 571 – 578 .

Perez T , Burgel PR , Paillasseur JL et al. ; INITIATIVES BPCO Scientific Committee . Modified Medical Research Council scale vs Baseline Dyspnea Index to evaluate dyspnea in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease . Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015 ; 10 : 1663 – 1672 .

Bodescu MM , Turcanu AM , Gavrilescu MC , Mihăescu T . Respiratory rehabilitation in healing depression and anxiety in COPD patients . Pneumologia 2015 ; 64 : 14 – 18 .

Hsu KY , Lin JR , Lin MS , Chen W , Chen YJ , Yan YH . The modified Medical Research Council dyspnoea scale is a good indicator of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease . Singapore Med J 2013 ; 54 : 321 – 327 .

Rhee CK , Kim JW , Hwang YI et al. Discrepancies between modified Medical Research Council dyspnea score and COPD assessment test score in patients with COPD . Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015 ; 10 : 1623 – 1631 .

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| August 2017 | 8 |

| September 2017 | 40 |

| October 2017 | 49 |

| November 2017 | 25 |

| December 2017 | 13 |

| January 2018 | 12 |

| February 2018 | 12 |

| March 2018 | 25 |

| April 2018 | 15 |

| May 2018 | 30 |

| June 2018 | 9 |

| July 2018 | 21 |

| August 2018 | 112 |

| September 2018 | 70 |

| October 2018 | 91 |

| November 2018 | 232 |

| December 2018 | 229 |

| January 2019 | 254 |

| February 2019 | 273 |

| March 2019 | 444 |

| April 2019 | 442 |

| May 2019 | 382 |

| June 2019 | 351 |

| July 2019 | 447 |

| August 2019 | 475 |

| September 2019 | 450 |

| October 2019 | 581 |

| November 2019 | 563 |

| December 2019 | 475 |

| January 2020 | 550 |

| February 2020 | 574 |

| March 2020 | 477 |

| April 2020 | 482 |

| May 2020 | 267 |

| June 2020 | 414 |

| July 2020 | 412 |

| August 2020 | 386 |

| September 2020 | 587 |

| October 2020 | 500 |

| November 2020 | 472 |

| December 2020 | 441 |

| January 2021 | 415 |

| February 2021 | 454 |

| March 2021 | 655 |

| April 2021 | 657 |

| May 2021 | 589 |

| June 2021 | 619 |

| July 2021 | 582 |

| August 2021 | 604 |

| September 2021 | 526 |

| October 2021 | 614 |

| November 2021 | 610 |

| December 2021 | 510 |

| January 2022 | 559 |

| February 2022 | 536 |

| March 2022 | 647 |

| April 2022 | 670 |

| May 2022 | 613 |

| June 2022 | 505 |

| July 2022 | 531 |

| August 2022 | 557 |

| September 2022 | 574 |

| October 2022 | 692 |

| November 2022 | 875 |

| December 2022 | 671 |

| January 2023 | 786 |

| February 2023 | 737 |

| March 2023 | 866 |

| April 2023 | 693 |

| May 2023 | 801 |

| June 2023 | 632 |

| July 2023 | 749 |

| August 2023 | 559 |

| September 2023 | 657 |

| October 2023 | 782 |

| November 2023 | 868 |

| December 2023 | 780 |

| January 2024 | 1,325 |

| February 2024 | 1,078 |

| March 2024 | 1,002 |

| April 2024 | 889 |

| May 2024 | 966 |

| June 2024 | 700 |

| July 2024 | 634 |

| August 2024 | 665 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Contact SOM

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1471-8405

- Print ISSN 0962-7480

- Copyright © 2024 Society of Occupational Medicine

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale in GOLD Classification Better Reflects Physical Activities of Daily Living

Affiliations.

- 1 Núcleo de Assistência, Ensino e Pesquisa em Reabilitação Pulmonar, Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina (UDESC), Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil and the Programa de Pós-Graduação em Fisioterapia, Centro de Ciências da Saúde e do Esporte (CEFID), Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina (UDESC), Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil.

- 2 Núcleo de Assistência, Ensino e Pesquisa em Reabilitação Pulmonar, Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina (UDESC), Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil and the Programa de Pós-Graduação em Fisioterapia, Centro de Ciências da Saúde e do Esporte (CEFID), Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina (UDESC), Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil. [email protected].

- PMID: 28874609

- DOI: 10.4187/respcare.05636

Background: In multidimensional Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) classification, the choice of the symptom assessment instrument (modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale [mMRC] or COPD assessment test [CAT]) can lead to a different distribution of patients in each quadrant. Considering that physical activities of daily living (PADL) is an important functional outcome in COPD, the objective of this study was to determine which symptom assessment instrument is more strongly associated with and differentiates better the PADL of patients with COPD.

Methods: The study included 115 subjects with COPD (GOLD 2-4), who were submitted to spirometry, the mMRC, the CAT, and monitoring of PADL (triaxial accelerometer). Subjects were divided into 2 groups using the cutoffs proposed by the multidimensional GOLD classification: mMRC < 2 and ≥ 2 and CAT < 10 and ≥ 10.

Results: Both mMRC and CAT reflected the PADL of COPD subjects. Subjects with mMRC < 2 and CAT < 10 spent less time in physical activities < 1.5 metabolic equivalents of task (METs) (mean of the difference [95% CI] = -62.9 [-94.4 to -31.4], P < .001 vs -71.0 [-116 to -25.9], P = .002) and had a higher number of steps (3,076 [1,999-4,153], P < .001 vs 2,688 [1,042-4,333], P = .002) than subjects with mMRC > 2 and CAT > 10, respectively. Physical activities ≥ 3 METs differed only between mMRC < 2 and mMRC ≥ 2 (39.2 [18.8-59.6], P < .001). Furthermore, only the mMRC was able to predict the PADL alone (time active, r 2 = 0.16; time sedentary, r 2 = 0.12; time ≥ 3 METs, r 2 = 0.12) and associated with lung function (number of steps, r 2 = 0.35; walking time, r 2 = 0.37; time < 1.5 METs, r 2 = 0.25).

Conclusions: The mMRC should be adopted as the classification criterion for symptom assessment in the GOLD ABCD system when focusing on PADL.

Keywords: GOLD classification; activities of daily living; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; dyspnea; exercise; sedentary lifestyle; symptom assessment.

Copyright © 2018 by Daedalus Enterprises.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Similar articles

- Modified Medical Research Council and COPD Assessment Test Cutoff Points. Munari AB, Gulart AA, Araújo J, Zanotto J, Sagrillo LM, Karloh M, Mayer AF. Munari AB, et al. Respir Care. 2021 Dec;66(12):1876-1884. doi: 10.4187/respcare.08889. Epub 2021 Oct 20. Respir Care. 2021. PMID: 34670858

- Differences in classification of COPD group using COPD assessment test (CAT) or modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scores: a cross-sectional analyses. Kim S, Oh J, Kim YI, Ban HJ, Kwon YS, Oh IJ, Kim KS, Kim YC, Lim SC. Kim S, et al. BMC Pulm Med. 2013 Jun 3;13:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-13-35. BMC Pulm Med. 2013. PMID: 23731868 Free PMC article.

- GOLD Classification of COPD: Discordance in Criteria for Symptoms and Exacerbation Risk Assessment. Mittal R, Chhabra SK. Mittal R, et al. COPD. 2017 Feb;14(1):1-6. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2016.1230844. Epub 2016 Oct 10. COPD. 2017. PMID: 27723367

- The COPD Assessment Test: What Do We Know So Far?: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis About Clinical Outcomes Prediction and Classification of Patients Into GOLD Stages. Karloh M, Fleig Mayer A, Maurici R, Pizzichini MMM, Jones PW, Pizzichini E. Karloh M, et al. Chest. 2016 Feb;149(2):413-425. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1752. Epub 2016 Jan 12. Chest. 2016. PMID: 26513112 Review.

- Assessing Symptom Burden. Vogelmeier CF, Alter P. Vogelmeier CF, et al. Clin Chest Med. 2020 Sep;41(3):367-373. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2020.06.005. Clin Chest Med. 2020. PMID: 32800191 Review.

- The Effect of 14-Day Consumption of Hydrogen-Rich Water Alleviates Fatigue but Does Not Ameliorate Dyspnea in Long-COVID Patients: A Pilot, Single-Blind, and Randomized, Controlled Trial. Tan Y, Xie Y, Dong G, Yin M, Shang Z, Zhou K, Bao D, Zhou J. Tan Y, et al. Nutrients. 2024 May 19;16(10):1529. doi: 10.3390/nu16101529. Nutrients. 2024. PMID: 38794767 Free PMC article. Clinical Trial.

- Influencing factors of sedentary behaviour in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Harding S, Richardson A, Glynn A, Hodgson L. Harding S, et al. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2024 May 24;11(1):e002261. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2023-002261. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2024. PMID: 38789283 Free PMC article.

- Prevalence and determinants of health-related quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in Yaoundé, Cameroon: a pilot study. Nsounfon AW, Massongo M, Kuaban A, Komo MEN, Mayap VP, Ekongolo MC, Yone EWP. Nsounfon AW, et al. Pan Afr Med J. 2024 Feb 1;47:39. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2024.47.39.39701. eCollection 2024. Pan Afr Med J. 2024. PMID: 38586064 Free PMC article.

- Evaluation of Pulmonary Function Tests, Dyspnea Scores, and Antibody Levels at the Six-Month Follow-Up of Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19 Pneumonia. Özmen K, Meral M, Kerget B, Yılmazel Uçar E, Sağlam L, Özmen M. Özmen K, et al. Cureus. 2024 Mar 12;16(3):e56003. doi: 10.7759/cureus.56003. eCollection 2024 Mar. Cureus. 2024. PMID: 38476506 Free PMC article.

- Long-term respiratory consequences of COVID-19 related pneumonia: a cohort study. Eizaguirre S, Sabater G, Belda S, Calderón JC, Pineda V, Comas-Cufí M, Bonnin M, Orriols R. Eizaguirre S, et al. BMC Pulm Med. 2023 Nov 11;23(1):439. doi: 10.1186/s12890-023-02627-w. BMC Pulm Med. 2023. PMID: 37951891 Free PMC article.

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources, other literature sources.

- scite Smart Citations

- Genetic Alliance

- MedlinePlus Consumer Health Information

- MedlinePlus Health Information

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 01 October 2012

The modified Medical Research Council scale for the assessment of dyspnea in daily living in obesity: a pilot study

- Claire Launois 1 ,

- Coralie Barbe 2 ,

- Eric Bertin 3 ,

- Julie Nardi 1 ,

- Jeanne-Marie Perotin 1 ,

- Sandra Dury 1 ,

- François Lebargy 1 &

- Gaëtan Deslee 1

BMC Pulmonary Medicine volume 12 , Article number: 61 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

61k Accesses

79 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Dyspnea is very frequent in obese subjects. However, its assessment is complex in clinical practice. The modified Medical Research Council scale (mMRC scale) is largely used in the assessment of dyspnea in chronic respiratory diseases, but has not been validated in obesity. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the use of the mMRC scale in the assessment of dyspnea in obese subjects and to analyze its relationships with the 6-minute walk test (6MWT), lung function and biological parameters.

Forty-five obese subjects (17 M/28 F, BMI: 43 ± 9 kg/m 2 ) were included in this pilot study. Dyspnea in daily living was evaluated by the mMRC scale and exertional dyspnea was evaluated by the Borg scale after 6MWT. Pulmonary function tests included spirometry, plethysmography, diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide and arterial blood gases. Fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, triglyceride, N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide, C-reactive protein and hemoglobin levels were analyzed.

Eighty-four percent of patients had a mMRC ≥ 1 and 40% a mMRC ≥ 2. Compared to subjects with no dyspnea (mMRC = 0), a mMRC ≥ 1 was associated with a higher BMI (44 ± 9 vs 36 ± 5 kg/m 2 , p = 0.01), and a lower expiratory reserve volume (ERV) (50 ± 31 vs 91 ± 32%, p = 0.004), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV 1 ) (86 ± 17 vs 101 ± 16%, p = 0.04) and distance covered in 6MWT (401 ± 107 vs 524 ± 72 m, p = 0.007). A mMRC ≥ 2 was associated with a higher Borg score after the 6MWT (4.7 ± 2.5 vs 6.5 ± 1.5, p < 0.05).

This study confirms that dyspnea is very frequent in obese subjects. The differences between the “dyspneic” and the “non dyspneic” groups assessed by the mMRC scale for BMI, ERV, FEV 1 and distance covered in 6MWT suggests that the mMRC scale might be an useful and easy-to-use tool to assess dyspnea in daily living in obese subjects.

Peer Review reports

Obesity, defined as a Body Mass Index (BMI) greater than or equal to 30 kg/m 2 , is a significant public health concern. According to the World Health Organization, worldwide obesity has more than doubled since 1980 and in 2008 there were about 1.5 billion overweight adults (25 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m 2 ). Of these, over 200 million men and nearly 300 million women were obese [ 1 ].

Dyspnea is very frequent in obese subjects. In a large epidemiological study, 80% of obese patients reported dyspnea after climbing two flights of stairs [ 2 ]. In a series of patients with morbid obesity, Collet et al. found that patients with a BMI > 49 kg/m 2 had more severe dyspnea assessed with BDI (Baseline Dyspnea Index) than obese patients with a BMI ≤ 49 kg/m 2 [ 3 ]. The most frequent pulmonary function abnormalities associated with obesity [ 4 , 5 ] are a decrease in expiratory reserve volume (ERV) [ 6 – 8 ], functional residual capacity (FRC) [ 6 – 8 ], and an increase in oxygen consumption [ 9 ]. Although the mechanisms of dyspnea in obesity remain unclear, it is moderately correlated with lung function [ 3 , 10 – 16 ]. Of note, type 2 diabetes [ 17 ], insulin resistance [ 18 ] and metabolic syndrome [ 19 ] have been shown to be associated with reduced lung function in obesity. It must be pointed out that dyspnea is a complex subjective sensation which is difficult to assess in clinical practice. However, there is no specific scale to assess dyspnea in daily living in obesity. The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale is the most commonly used validated scale to assess dyspnea in daily living in chronic respiratory diseases [ 20 – 22 ] but has never been assessed in the context of obesity without a coexisting pulmonary disease.

The objectives of this pilot study were to evaluate the use of the mMRC scale in the assessment of dyspnea in obese subjects and to analyze its relationships with the 6-minute walk distance (6MWD), lung function and biological parameters.

Adult obese patients from the Department of Nutrition of the University Hospital of Reims (France) were consecutively referred for a systematic respiratory evaluation without specific reason and considered for inclusion in this study. Inclusion criteria were a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m 2 and an age > 18 year-old. Exclusion criteria were a known coexisting pulmonary or neuromuscular disease or an inability to perform a 6MWT or pulmonary function testing. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University Hospital of Reims, and patient consent was waived.

Clinical characteristics and mMRC scale

Demographic data (age, sex), BMI, comorbidities, treatments and smoking status were systematically recorded. Dyspnea in daily living was evaluated by the mMRC scale which consists in five statements that describe almost the entire range of dyspnea from none (Grade 0) to almost complete incapacity (Grade 4) (Table 1 ).

- Six-minute walk test

The 6MWT was performed using the methodology specified by the American Thoracic Society (ATS-2002) [ 23 ]. The patients were instructed that the objective was to walk as far as possible during 6 minutes. The 6MWT was performed in a flat, long, covered corridor which was 30 meters long, meter-by-meter marked. Heart rate, oxygen saturation and modified Borg scale assessing subjectively the degree of dyspnea graded from 0 to 10, were collected at the beginning and at the end of the 6MWT. When the test was finished, the distance covered was calculated.

Pulmonary function tests

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) included forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV 1 ), vital capacity (VC), forced vital capacity (FCV), FEV 1 /VC, functional residual capacity (FRC), expiratory reserve volume (ERV), residual volume (RV), total lung capacity (TLC) and carbon monoxide diffusing capacity of the lung (DLCO) (BodyBox 5500 Medisoft Sorinnes, Belgium). Results were expressed as the percentage of predicted values [ 24 ]. Arterial blood gases were measured in the morning in a sitting position.

Biological parameters

After 12 hours of fasting, blood glucose, glycated hemoglobin (HbAIc), total cholesterol, triglyceride, N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro BNP), C-reactive protein (CRP) and hemoglobin levels were measured.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are described as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and qualitative variables as number and percentage. Patients were separated in two groups according to their dyspnea: mMRC = 0 (no dyspnea in daily living) and mMRC ≥ 1 (dyspnea in daily living, ie at least short of breath when hurrying on level ground or walking up a slight hill).

Factors associated with mMRC scale were studied using Wilcoxon, Chi-square or Fisher exact tests. Factors associated with Borg scale were studied using Wilcoxon tests or Pearson’s correlation coefficients. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analysis were performed using SAS version 9.0 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results and discussion

Demographic characteristics.

Fifty four consecutive patients with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m 2 were considered for inclusion. Of these, 9 patients were excluded because of an inability to perform the 6MWT related to an osteoarticular disorder (n = 2) or because of a diagnosed respiratory disease (n = 7; 5 asthma, 1 hypersensitivity pneumonia and 1 right pleural effusion).

Results of 45 patients were considered in the final analysis. Demographic characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 2 . Mean BMI was 43 ± 9 kg/m 2 , with 55% of the patients presenting an extreme obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m 2 , grade 3). Regarding smoking status, 56% of patients were never smokers and 11% were current smokers. The main comorbidities were hypertension (53%), dyslipidemia (40%) and diabetes (36%). Severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome was present in 16 patients (43%).

Dyspnea assessment by the mMRC scale and 6MWT

Results of dyspnea assessment are presented in Table 3 . Dyspnea symptom assessed by the mMRC scale was very frequent in obese subjects with 84% (n = 38) of patients with a mMRC scale ≥ 1 and 40% (n = 18) of patients with a mMRC scale ≥ 2 (29% mMRC = 2, 9% mMRC = 3 and 2% mMRC = 4).

The mean distance covered in 6MWT was 420 ± 112 m. Sixteen percent of patients had a decrease > 4% of SpO2 during the 6MWT and one patient had a SpO2 < 90% at the end of the 6MWT (Table 4 ). The dyspnea sensation at rest was very slight (Borg = 1 ± 1.5) but severe after exertion (Borg = 5.4 ± 2.4). Fifty-three percent of patients exhibited a Borg scale ≥ 5 after the 6MWT which is considered as severe exertional dyspnea. No complication occurred during the 6MWT. Subjects with a mMRC score ≥ 2 had a higher Borg score after the 6MWT than subjects with a mMRC score < 2 (6.5 ± 1.5 vs 4.7 ± 2.5, p < 0.05).

Lung function tests

Results of spirometry, plethysmography and arterial blood gases are shown in Table 4 . Overall, the PFTs results remained in the normal range for most of the patients, except for ERV predicted values which were lower (ERV = 56 ± 34%). There were an obstructive ventilatory disorder defined by a FEV 1 /VC < 0.7 in 5 patients (11%) with 5 patients (13%) exhibiting a mMRC ≥ 1, a restrictive ventilatory disorder defined by a TLC < 80% in 5 patients (13%) with 5 patients (16%) exhibiting a mMRC ≥ 1, and a decrease in alveolar diffusion defined by DLCO < 70% in 10 patients (26%) with 9 patients (28%) exhibiting a mMRC ≥ 1. Arterial blood gases at rest were in the normal range with no hypoxemia < 70 mmHg and no significant hypercapnia > 45 mmHg.

Fifteen percent (n = 7) of patients presented anemia. All patients had a hemoglobin level ≥ 11 g/dL. Mean NT pro-BNP was 117 ± 285 pg/mL. Four patients (10%) had a pro-BNP > 300 pg/mL.Forty-five percent of patients had a fasting glucose level > 7 mmol/L, 51% a Hba1c > 6%, 29% a triglyceride level ≥ 1.7 mmol/L, 35% a total cholesterol level > 5.2 mmol/L and 31% a CRP level > 10 mg/L.

Relationships between the mMRC scale and clinical characteristics, PFTs and biological parameters

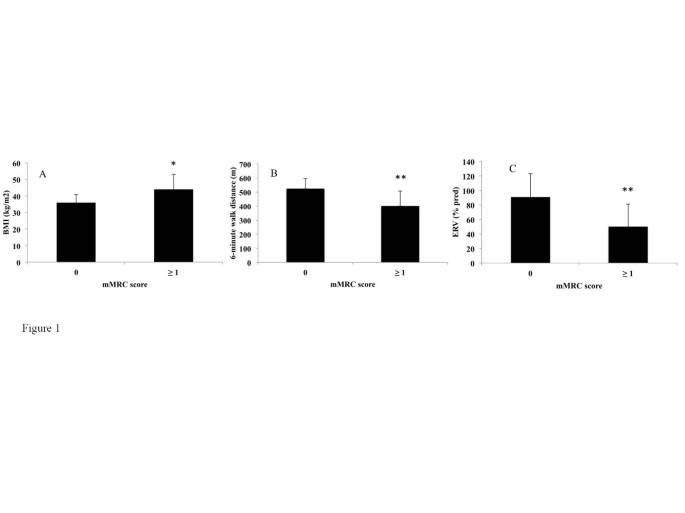

The comparisons between the mMRC scale and demographic, lung functional and biological parameters are shown in Table 5 . Subjects in the mMRC ≥ 1 group had a higher BMI (p = 0.01) (Figure 1 A), lower ERV (p < 0.005) (Figure 1 B), FEV 1 (p < 0.05), covered distance in 6MWT (p < 0.01) (Figure 1 C) and Hb level (p < 0.05) than subjects in the mMRC = 0 group. Of note, there was no association between the mMRC scale and age, sex, smoking history, arterial blood gases, metabolic parameters and the apnea/hypopnea index.

Differences in Body Mass Index (BMI) (A), Expiratory reserve volume (ERV) (B) and 6-minute walk distance (C) between non-dyspneic (modified Medical Research Council score = 0) and dyspneic (mMRC score ≥ 1) subjects. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. A Wilcoxon test was used.

The relationships between the Borg scale after 6MWT and demographic, lung functional and biological parameters were also analysed. The Borg score after 6MWT was correlated with a higher BMI (correlation coefficient = +0.44, p < 0.005) and a lower FEV 1 (correlation coefficient = -0.33, p < 0.05). No relationship was found between the Borg score after 6MWT and ERV or hemoglobin level. The Borg score after 6MWT was correlated with a higher fasting glucose (correlation coefficient = +0.46, p < 0.005) whereas this parameter was not associated with the mMRC scale (data not shown). We found no statistically different change in Borg scale ratings of dyspnea from rest to the end of the 6MWT between the two groups (p = 0.39).

In this study, 45 consecutive obese subjects were specifically assessed for dyspnea in daily living using the mMRC scale. Our study confirms the high prevalence of dyspnea in daily living in obese subjects [ 2 ] with 84% of patients exhibiting a mMRC scale ≥ 1 and 40% a mMRC scale ≥ 2. Interestingly, the presence of dyspnea in daily living (mMRC ≥ 1) was associated with a higher BMI and a lower ERV, FEV 1 , distance covered in 6MWT and hemoglobin level. Furthermore, a mMRC score ≥ 2 in obese subjects was associated with a higher Borg score after the 6MWT (data not shown).

The assessment of dyspnea in clinical practice is difficult. Regarding the mMRC scale, two versions of this scale have been used, one with 5 grades [ 20 ] as used in this study and an other with 6 grades [ 25 ] leading to some confusion. Other scales have been also used to assess dyspnea [ 26 ]. Collet at al. [ 3 ], Ofir et al. [ 11 ] and El-Gamal [ 27 ] et al provided some evidence to support the use of the BDI, Oxygen cost diaphragm (OCD) and Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ) to evaluate dyspnea in obesity. El-Gamal et al [ 27 ] demonstated the responsiveness of the CRQ in obesity as they did measurements before and after gastroplaty-induced weight loss within the same subjects. The Baseline Dyspnea Index (BDI) uses five grades (0 to 4) for 3 categories, functional impairment, magnitude of task and magnitude of effort with a total score from 0 to 12 [ 28 ]. The University of California San Diego Shortness of Breath Questionnaire comprises 24 items assessing dyspnea over the previous week [ 29 ]. It must be pointed out that these scores are much more time consuming than the mMRC scale and are difficult to apply in clinical practice.

To our knowledge, the mMRC scale has not been investigated in the assessment of dyspnea in daily living in obese subjects without a coexisting pulmonary disease. The mMRC scale is an unidimensional scale related to activities of daily living which is widely used and well correlated with quality of life in chronic respiratory diseases [ 20 ] such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [ 21 ] or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [ 22 ]. The mMRC scale is easy-to-use and not time consuming, based on five statements describing almost the entire range of dyspnea in daily living. Our study provides evidence for the use of the mMRC scale in the assessment of dyspnea in daily living in obese subjects. Firstly, as expected, our results demonstrate an association between the mMRC scale and the BMI in the comparison between “dyspneic” and “non dyspneic” groups. Secondly, in our between-group comparisons, the mMRC scale was associated with pulmonary functional parameters (lower ERV, FEV 1 and distance walked in 6MWT) which might be involved in dyspnea in obesity. The reduction in ERV is the most frequent functional respiratory abnormality reported in obesity [ 6 – 8 ]. This decrease is correlated exponentially with BMI and is mainly due to the effect of the abdominal contents on diaphragm position [ 30 ]. While the FEV 1 might be slightly reduced in patients with severe obesity, the FEV 1 /VC is preserved as seen in our study [ 31 ]. The determination of the walking distance and the Borg scale using the 6MWT is known to be a simple method to assess the limitations of exercise capacity in chronic respiratory diseases [ 23 ]. Two studies have shown a good reproducibility of this test [ 32 , 33 ] but did not investigate the relationships between the 6MWD and dyspnea in daily living. Our study confirms the feasibility of the 6MWD in clinical practice in obesity and demonstrates an association between covered distance in 6MWT and the presence or the absence of dyspnea in daily living assessed by the mMRC scale. It must be pointed out that the 6MWT is not a standardized exercise stimulus. Exercise testing using cycloergometer or the shuttle walking test could be of interest to determine the relationships between the mMRC scale and a standardize exercise stimulus. In our between-group comparisons, BMI and FEV 1 were associated with the mMRC scale and correlated with the Borg scale after 6MWT. Surprisingly, the ERV was associated with the mMRC scale but not with the Borg scale. Moreover, the fasting glucose was correlated with the Borg scale after 6MWT but not associated with the mMRC scale. Whether these differences are due to a differential involvement of these parameters in dyspnea in daily living and at exercise, or simply related to a low sample size remains to be evaluated.

As type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome [ 17 – 19 ], anemia and cardiac insufficiency have been shown to be associated with lung function and/or dyspnea, we also investigated the relationships between dyspnea in daily living and biological parameters. A mMRC scale ≥ 1 was associated with a lower hemoglobin level. However, all patients had a hemoglobin level > 11 g/dL and the clinical significance of the association between dyspnea in daily living and a mildly lower hemoglobin level has to be interpreted cautiously and remains to be evaluated. Of note, we did not find any associations between the mMRC scale and triglyceride, total cholesterol, fasting glucose, HbA1C, CRP or NT pro-BNP.

The strength of this study includes the assessment of the relationships between the mMRC scale and multidimensional parameters including exertional dyspnea assessed by the Borg score after 6MWT, PFTs and biological parameters. The limitations of this pilot study are as follows. Firstly, the number of patients included is relatively low. This study was monocentric and did not include control groups of overweight and normal weight subjects. Due to the limited number of patients, our study did not allow the analysis sex differences in the perception of dyspnea. Secondly, we did not investigate the relationships between the mMRC scale and other dyspnea scales like the BDI which has been evaluated in obese subjects and demonstrated some correlations with lung function [ 3 ]. Thirdly, it would have been interesting to assess the relationships between the mMRC scale and cardio-vascular, neuromuscular and psycho-emotional parameters which might be involved in dyspnea. Assessing the relationships between health related quality of life and dyspnea would also be useful. Finally, fat distribution (eg Waist circumferences or waist/hip ratios) has not been specifically assessed in our study but might be assessed at contributing factor to dyspnea. Despite these limitations, this pilot study suggests that the mMRC scale might be of value in the assessment of dyspnea in obesity and might be used as a dyspnea scale in further larger multicentric studies. It remains to be seen whether it is sensitive to changes with intervention.

Conclusions

This pilot study investigated the potential use of the mMRC scale in obesity. The differences observed between the “dyspneic” and the “non dyspneic” groups as defined by the mMRC scale with respect to BMI, ERV, FEV 1 and distance covered in 6MWT suggests that the mMRC scale might be an useful and easy-to-use tool to assess dyspnea in daily living in obese subjects.

Abbreviations

Body Mass Index

- Modified Medical Research Council scale

Expiratory volume in one second

Vital capacity

Forced vital capacity

Functional residual capacity

Expiratory reserve volume

Residual volume

Total lung capacity

Carbon monoxide diffusing capacity of the lung

Glycated hemoglobin

N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide

Serum C reactive protein.

WHO: Obesity and overweight. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/ ,

Sjöström L, Larsson B, Backman L, Bengtsson C, Bouchard C, Dahlgren S, Hallgren P, Jonsson E, Karlsson J, Lapidus L: Swedish obese subjects (SOS). Recruitment for an intervention study and a selected description of the obese state. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1992, 16: 465-479.

PubMed Google Scholar

Collet F, Mallart A, Bervar JF, Bautin N, Matran R, Pattou F, Romon M, Perez T: Physiologic correlates of dyspnea in patients with morbid obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007, 31: 700-706.

CAS Google Scholar

Salome CM, King GG, Berend N: Physiology of obesity and effects on lung function. J Appl Physiol. 2010, 108: 206-211. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00694.2009.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gibson GJ: Obesity, respiratory function and breathlessness. Thorax. 2000, 55 (Suppl 1): S41-S44.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ray CS, Sue DY, Bray G, Hansen JE, Wasserman K: Effects of obesity on respiratory function. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983, 128: 501-506.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Jones RL, Nzekwu M-MU: The effects of body mass index on lung volumes. Chest. 2006, 130: 827-833. 10.1378/chest.130.3.827.

Biring MS, Lewis MI, Liu JT, Mohsenifar Z: Pulmonary physiologic changes of morbid obesity. Am J Med Sci. 1999, 318: 293-297. 10.1097/00000441-199911000-00002.

Babb TG, Ranasinghe KG, Comeau LA, Semon TL, Schwartz B: Dyspnea on exertion in obese women: association with an increased oxygen cost of breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008, 178: 116-123. 10.1164/rccm.200706-875OC.

Sahebjami H: Dyspnea in obese healthy men. Chest. 1998, 114: 1373-1377. 10.1378/chest.114.5.1373.

Ofir D, Laveneziana P, Webb KA, O’Donnell DE: Ventilatory and perceptual responses to cycle exercise in obese women. J Appl Physiol. 2007, 102: 2217-2226. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00898.2006.

Romagnoli I, Laveneziana P, Clini EM, Palange P, Valli G, de Blasio F, Gigliotti F, Scano G: Role of hyperinflation vs. deflation on dyspnoea in severely to extremely obese subjects. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2008, 193: 393-402. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2008.01852.x.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Jensen D, Webb KA, Wolfe LA, O’Donnell DE: Effects of human pregnancy and advancing gestation on respiratory discomfort during exercise. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007, 156: 85-93. 10.1016/j.resp.2006.08.004.

Scano G, Stendardi L, Bruni GI: The respiratory muscles in eucapnic obesity: their role in dyspnea. Respir Med. 2009, 103: 1276-1285. 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.03.023.

Ora J, Laveneziana P, Ofir D, Deesomchok A, Webb KA, O’Donnell DE: Combined effects of obesity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on dyspnea and exercise tolerance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009, 180: 964-971.

Sava F, Laviolette L, Bernard S, Breton M-J, Bourbeau J, Maltais F: The impact of obesity on walking and cycling performance and response to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD. BMC Pulm Med. 2010, 10: 55-10.1186/1471-2466-10-55.

Lecube A, Sampol G, Muñoz X, Hernández C, Mesa J, Simó R: Type 2 diabetes impairs pulmonary function in morbidly obese women: a case-control study. Diabetologia. 2010, 53: 1210-1216. 10.1007/s00125-010-1700-5.

Lecube A, Sampol G, Muñoz X, Lloberes P, Hernández C, Simó R: Insulin resistance is related to impaired lung function in morbidly obese women: a case-control study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010, 26: 639-645. 10.1002/dmrr.1131.

Leone N, Courbon D, Thomas F, Bean K, Jégo B, Leynaert B, Guize L, Zureik M: Lung function impairment and metabolic syndrome: the critical role of abdominal obesity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009, 179: 509-516. 10.1164/rccm.200807-1195OC.

Mahler DA, Wells CK: Evaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspnea. Chest. 1988, 93: 580-586. 10.1378/chest.93.3.580.

Hajiro T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, Ikeda A, Koyama H, Izumi T: Analysis of Clinical Methods Used to Evaluate Dyspnea in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998, 158: 1185-1189.

Nishiyama O, Taniguchi H, Kondoh Y, Kimura T, Kato K, Kataoka K, Ogawa T, Watanabe F, Arizono S: A simple assessment of dyspnoea as a prognostic indicator in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2010, 36: 1067-1072. 10.1183/09031936.00152609.

ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002, 166: 111-117.

Standardized lung function testing. Official statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J Suppl. 1993, 16: 1-100.

Eltayara L, Becklake MR, Volta CA, Milic-Emili J: Relationship between chronic dyspnea and expiratory flow limitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996, 154: 1726-1734.

Gerlach Y, Williams MT, Coates AM: Weighing up the evidence-a systematic review of measures used for the sensation of breathlessness in obesity. Int J Obes. 2012

Google Scholar

El-Gamal H, Khayat A, Shikora S, Unterborn JN: Relationship of dyspnea to respiratory drive and pulmonary function tests in obese patients before and after weight loss. Chest. 2005, 128: 3870-3874. 10.1378/chest.128.6.3870.

Mahler DA, Weinberg DH, Wells CK, Feinstein AR: The measurement of dyspnea. Contents, interobserver agreement, and physiologic correlates of two new clinical indexes. Chest. 1984, 85: 751-758. 10.1378/chest.85.6.751.

Eakin EG, Resnikoff PM, Prewitt LM, Ries AL, Kaplan RM: Validation of a new dyspnea measure: the UCSD Shortness of Breath Questionnaire. University of California, San Diego. Chest. 1998, 113: 619-624. 10.1378/chest.113.3.619.

Parameswaran K, Todd DC, Soth M: Altered respiratory physiology in obesity. Can Respir J. 2006, 13: 203-210.

Sin DD, Jones RL, Man SFP: Obesity is a risk factor for dyspnea but not for airflow obstruction. Arch Intern Med. 2002, 162: 1477-1481. 10.1001/archinte.162.13.1477.

Beriault K, Carpentier AC, Gagnon C, Ménard J, Baillargeon J-P, Ardilouze J-L, Langlois M-F: Reproducibility of the 6-minute walk test in obese adults. Int J Sports Med. 2009, 30: 725-727. 10.1055/s-0029-1231043.

Larsson UE, Reynisdottir S: The six-minute walk test in outpatients with obesity: reproducibility and known group validity. Physiother Res Int. 2008, 13: 84-93. 10.1002/pri.398.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2466/12/61/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the personnel of the Department of Nutrition and Pulmonary Medicine of the University Hospital of Reims for the selection and clinical/functional assessment of the patients.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Service des Maladies Respiratoires, INSERM UMRS 903, Hôpital Maison Blanche, CHU de Reims, 45 rue Cognacq Jay 51092, Reims, Cedex, France

Claire Launois, Julie Nardi, Jeanne-Marie Perotin, Sandra Dury, François Lebargy & Gaëtan Deslee

Unité d'Aide Méthodologique, Pôle Recherche et Innovations, Hôpital Robert Debré, CHU de Reims, Reims, France

Coralie Barbe

Service d’Endocrinologie-Diabétologie-Nutrition, Hôpital Robert Debré, CHU de Reims, Reims, France

Eric Bertin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Claire Launois .

Additional information

Competing interests.

None of the authors of the present manuscript have a commercial or other association that might pose a conflict of interest.

Authors’ contributions

CL, CB, EB, JN, JMP, SD, FL and GD conceived the study. CL acquired data. CB performed the statistical analysis. CL and GD drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript prior to submission.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Launois, C., Barbe, C., Bertin, E. et al. The modified Medical Research Council scale for the assessment of dyspnea in daily living in obesity: a pilot study. BMC Pulm Med 12 , 61 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-12-61

Download citation

Received : 06 April 2012

Accepted : 22 September 2012

Published : 01 October 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-12-61

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Lung function

BMC Pulmonary Medicine

ISSN: 1471-2466

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Dyspnea MRC Scale

Evaluates the severity of dyspnea in patients who suffer from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

In the text below the calculator you can find more information about the two versions of the scale and about dyspnea signs in COPD.

The dyspnea MRC scale evaluates how dyspnea affects patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and provides a severity grade.

The scale can be used alongside the BODE index to evaluate the prognosis of COPD patients.

The five clinical grades of dyspnea (breathlessness attributed to low fitness or COPD) are determined based on the individual’s respiratory reaction to different physical daily activities.

The MRC scale was created by Fletcher in 1952 and has been tested, alongside data from the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) spirometric classification of COPD.

1. Dyspnea scale calculator

2. MRC scale explained

3. About dyspnea in COPD

4. References

- Original MRC

- Modified MRC

Please select one of the grades provided:

To embed this calculator, please copy this code and insert it into your desired page:

To Save This Calculator As A Favourite You Must Be Logged In...

Creating an account is free and takes less than 1 minute.

Send Us Your Feedback

Steps on how to print your input & results:

1. Fill in the calculator/tool with your values and/or your answer choices and press Calculate.

2. Then you can click on the Print button to open a PDF in a separate window with the inputs and results. You can further save the PDF or print it.

Please note that once you have closed the PDF you need to click on the Calculate button before you try opening it again, otherwise the input and/or results may not appear in the pdf.

MRC scale explained

This is a five grade clinical scale for patients with COPD that assesses the degree of dyspnea severity based on its impact on different physical daily activities.

The Medical Research Council scale was created by Fletcher in 1952 and starts from no nuisance from breathlessness during normal activities. Along the scale the degree of dyspnea increases.

The following table introduces the two versions of the MRC scale:

| Grade 1 - Not troubled by breathlessness except on strenuous exercise. | Grade 0 - I only get breathless with strenuous exercise. |

| Grade 2 - Short of breath when hurrying on the level or walking up a slight hill. | Grade 1 - I get short of breath when hurrying on level ground or walking up a slight hill. |

| Grade 3 - Walks slower than most people on the level, stops after a mile or so, or stops after 15 minutes walking at own pace. | Grade 2 - On level ground, I walk slower than people of the same age because of breathlessness, or I have to stop for breath when walking at my own pace on the level. |

| Grade 4 - Stops for breath after walking about 100 yards or after a few minutes on level ground. | Grade 3 - I stop for breath after walking about 100 yards or after a few minutes on level ground. |

| Grade 5 - Too breathless to leave the house or breathless when undressing. | Grade 4 - I am too breathless to leave the house or I am breathless when dressing or undressing. |

Currently, the modified version of the MRC (the MMRC) is most often used, especially alongside the BODE index, in the prognosis of patients diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The discriminative capacity of the MRC has been compared to data from the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) spirometric classification of COPD.

The two assessment methods have proven sufficient sensitivity separately but do not correlate between stages.

About dyspnea in COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a respiratory condition characterized by the following symptoms:

■ Breathlessness;

■ Cough (sometimes chronic);

■ Sputum production;

■ Wheezing;

■ Chest tightness;

■ Airway irritability.

The above are suggestive of chronic COPD whilst COPD exacerbation means a stronger infective episode of COPD when the symptom severity increases and fatigue and weight loss are also experienced.

Dyspnea or breathlessness, is defined as a sensation of difficulty in breathing. This is most often attributed to lack of exercise and low level of fitness but also to pulmonary conditions such as COPD.

On exertion, a certain degree of breathlessness can occur normally but in pathological cases, it occurs at a level of activity that is either generally well tolerated or at a level of activity that the patient used to tolerate.

The symptoms include a clearly audible breathing, gasping, flaring nostrils, cyanosis, distressed facial expression and chest protrusion.

The following introduces major causes of dyspnea:

■ Heart attack, congestive heart failure, arrhythmias;

■ Pneumonia or pulmonary hypertension;

■ Gastroesophageal reflux disease;

■ Presence of allergies;

■ Chest wall trauma or foreign object inhalation.

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND) occurs at night and awakens the patient. PND is only relieved by an upright position.

Dyspnea needs to be differenced from other respiratory frequency or flow variations such as tachypnea, hyperventilation, and hyperpnea.

Original source

Fletcher CM. The clinical diagnosis of pulmonary emphysema; an experimental study . Proc R Soc Med. 1952; 45(9):577-84.

Other references

1. Stenton C. The MRC breathlessness scale . Occup Med (Lond). 2008; 58(3):226-7.

2. Fletcher CM, Elmes PC, Fairbairn AS, Wood CH. The significance of respiratory symptoms and the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis in a working population . Br Med J. 1959; 2(5147):257-66.

3. Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones PW, Wedzicha JA. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease . Thorax. 1999; 54(7):581-6.

4. Rhee CK, Kim JW, Hwang YI, Lee JH, Jung KS, Lee MG, Yoo KH, Lee SH, Shin KC, Yoon HK. Discrepancies between modified Medical Research Council dyspnea score and COPD assessment test score in patients with COPD . Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015; 10:1623-31.

Specialty: Pulmonology

System: Respiratory

Objective: Evaluation

Type: Scale

No. Of Criteria: 5

Year Of Study: 1952

Abbreviation: MRC

Article By: Denise Nedea

Published On: June 13, 2017

Last Checked: June 13, 2017

Next Review: June 13, 2023

Get This Tool Embedded Into Your Website

for just $20/Year

The tool will be add free;

There is no resource limitation, as if the tool was hosted on your site, so all your users can make use of it 24/7;

The necessary tool updates will take place in real time with no effort on your end;

A single click install to embed it into your pages, whenever you need to use it.

Contact us below for pricing & ordering

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis

Evaluation of the Individual Activity Descriptors of the mMRC Breathlessness Scale: A Mixed Method Study

Janelle yorke.

1 Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

2 Christie Patient Centred Research, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust, Whittington, Manchester, UK

Naimat Khan

3 Medicines Evaluation Unit, Wythenshawe, Manchester, UK

Adam Garrow

Sarah tyson, jorgen vestbo.

4 Department of Respiratory Medicine, Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester, UK

Paul W Jones

5 St George's Hospital, University of London, London, UK

The modified-Medical Research Council (mMRC) breathlessness scale consists of five grades that contain of a description of different activities. It has wide utility in the assessment of disability due to breathlessness but was originally developed before the advent of modern psychometric methodology and, for example contains more than one activity per grade. We conducted an evaluation of the mMRC structure.

Patients and Methods

Cognitive debriefing was conducted with COPD patients to elicit their understanding of each mMRC activity. In a cross-sectional study, patients completed the mMRC scale (grades 0–4) and an MRC-Expanded (MRC-Ex) version consisting of 10-items, each containing one mMRC activity. Each activity was then given a 4-point response scale (0 “not at all” to 4 “all of the time”) and all 10 items were given to 203 patients to complete Rasch analysis and assess the pattern of MRC item severity and its hierarchical structure.

Cognitive debriefing with 36 patients suggested ambiguity with the term “strenuous exercise” and perceived severity differences between mMRC activities. 203 patients completed the mMRC-Ex. Strenuous exercise was located third on the ascending severity scale. Rasch identified the mildest term was “walking up a slight hill” (logit −2.76) and “too breathless to leave the house” was the most severe (logit 3.42).

This analysis showed that items that were combined into a single mMRC grade may be widely separated in terms of perceived severity when assessed individually. This suggests that mMRC grades as a measure of individual disability related to breathlessness contain significant ambiguity due to the combination of activities of different degrees of perceived severity into a single grade.

Introduction

Breathlessness is a complex subjective sensation that is common and debilitating in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Breathlessness is an important predictor of exercise tolerance 1 and both factors have been shown to influence patients’ health status at all levels of COPD severity. 2 Breathlessness can be quantified directly using scales such as the Borg and Visual Analogue Scales (VAS) or indirectly through its impact on physical activity. 3 , 4 The modified-Medical Research Council (mMRC) breathlessness scale classifies the disability associated with breathlessness by identifying different levels of activities that induce or are restricted by breathlessness. 5

The MRC breathlessness scale was first published in 1959 by Fletcher et al based on their study of respiratory symptoms experienced by Welsh coal miners in the 1940s. 5 It was originally developed as an epidemiological tool for studies of the general population, but over many decades has morphed into a tool that is applied at an individual patient level. The questionnaire is frequently used in COPD as breathlessness is a crucial symptom in this condition. 3 The original version of the MRC consists of scale ranges from grade 1 to 5. The mMRC version is now used which is similar in wording for each grade but consists of scale ranges from grade 0 to 4. It is important to note that it does not measure breathlessness directly, unlike other scales such as the Borg scale. Rather it measures the degree of activity at which a person gets breathlessness (such as “with strenuous exercise”) or limits what a person can do (such as “too breathless to leave the house”). It consists of five grades (1 to 5) that contain statements describing a range of physical limitations associated with breathlessness.

There is an assumption that the mMRC Grades are Guttman scaled 6 in which a person who fulfils the criteria for Grade 4, should also fulfil the criteria for Grade 3, 2 etc. Except for MRC Grade 0 (“not troubled by breathlessness except on strenuous exercise”), each grade consists of two different activity descriptions. For example, the components of Grade 4 include “too breathless to leave the house” or “breathless when dressing”; reflecting potentially large differences in activity level. To our knowledge the comparability of different mMRC grade components has not been previously subjected to rigorous testing.

The mMRC breathlessness scale has good discriminative ability and is a simple method of categorising patients with COPD in terms of their disability 7 , 8 and survival. 9 Thus, it is recommended for use as a marker of disability in international COPD guidelines 10 , 11 and used to assess suitability for pulmonary rehabilitation in the UK. 10 However, due to the wide spread of severity between MRC grades it is too insensitive to detect relevant changes in activity limitation due to breathlessness following an intervention. 3 Despite the widespread use of the scale, there has been little work to evaluate its psychometric properties, particularly the effect of combining different activity descriptions within the mMRC grades and the ordering of the grade severity. It is important to confirm whether the different components within each grade represent the same level of exertion. This study aimed to examine the content and construct validity of the MRC scale using cognitive debriefing with COPD patients and modern psychometric techniques. Specific objectives included: i) to determine how patients with COPD understand and interpret each mMRC grade descriptor; ii) to determine if patient responses to individual mMRC activities meet the requirements for Guttman scaling; and iii) to measure the similarity of scores between different activity descriptors within a single mMRC grade.

We used both qualitative and quantitative approaches to explore patients understanding more fully of the mMRC descriptors and to quantify the hierarchical structure of the scale. To achieve this, the study was conducted in two phases: Phase 1: cognitive debriefing to ascertain patients’ comprehension and views of each mMRC activity and Phase 2: application of descriptive statistics and Rasch analysis to assesses the performance of each mMRC grade component. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical approval for was provided by the National Research Ethics Committee for Greater Manchester East (ref: 12/NW/0608). This study was conducted between January 2013 – July 2015.

In each phase of the study, the participants were identified from a research database of COPD patients (n>800) recruited from primary care and hospital clinics; these patients had volunteered to participate in research studies at the Medicines Evaluation Unit, adjacent to Wythenshawe Hospital (South Manchester). Potential participants for each study phase were contacted by telephone to ascertain their interest in taking part. If interested, a study information pack was mailed to the patient and a suitable time to attend the research facility for consenting and data collection was agreed which were completed on the same day. Participants were paid a nominal fee for taking part in the study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria