Language Objectives: A Step by Step Guide

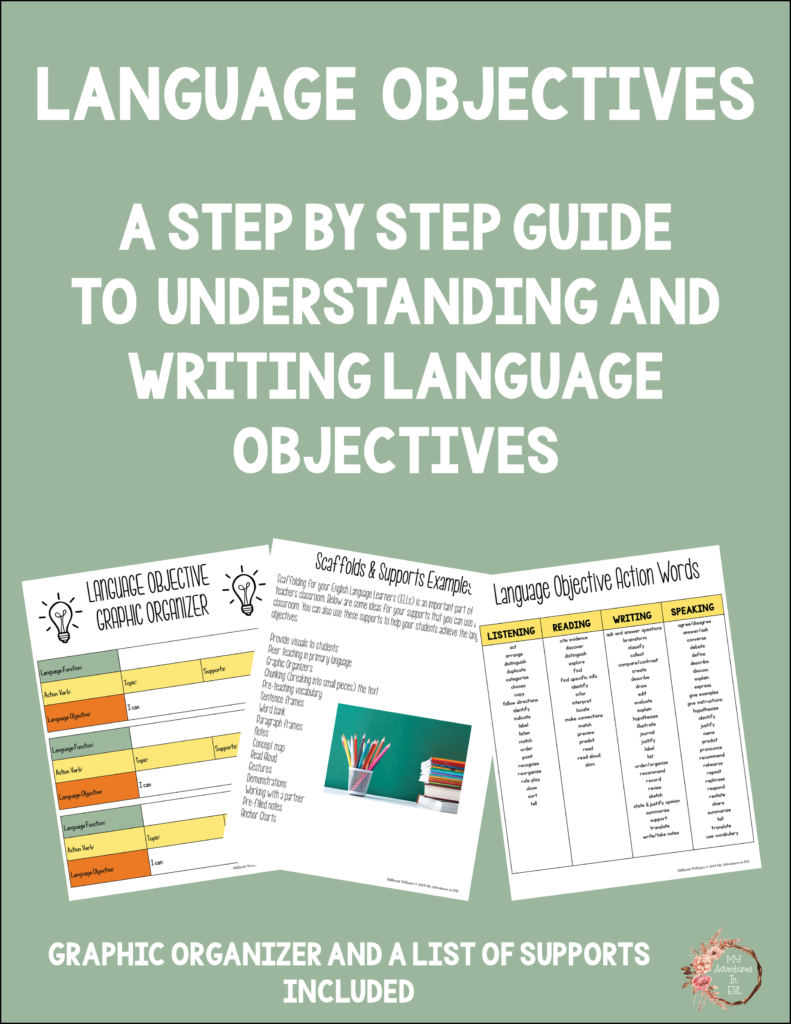

Do you want to know how to write language objectives? Download the Language Objective Guide to use the graphic organizer with this process. This guide will walk you through how to write language objectives step-by-step. You may be thinking what is a language objective? You might not be sure about content objectives. Teacher talk can get a little overwhelming. I know when I first started I had no idea what all these words mean. Here is a list of commonly used words with their definitions.

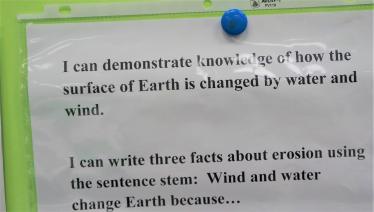

A content objective tells the student what they will be learning during the lesson. For example, I can analyze the connections and distinctions between individuals, ideas, or events in a text. A language objective tells how the students will learn and/or demonstrate their learning through the four domains of language. The four domains of language are reading, listening, speaking, and writing. Here is an example of a language objective: I can write the connections between events in a text.

If you were anything like me, I was confused on how to write language objectives. Here is a step by step process of how to write a language objective. Remember to ask yourself “How will the students show me through reading, listening, speaking, and writing that they understand the content objective?” Below is a video that I made that explains in detail how to write a language objective.

- Identify the content objective. What do you want the students to learn from the lesson?

- Think about where your students are in their language learning process. Even in mainstream classrooms where are you students in regards to the four domains of language.

- Identify the domain that you are asking students to do in the lesson. For example, there is a lesson where the students will be presenting to the class. The domain you are asking them to demonstrate their understanding would be speaking.

Now that you have gathered the information above here is how you write the language objective:

Sample Language Objective (Writing): I can summarize “ Little Red Riding Hood” using sentence frames with a partner.

- Looking at the chart identify the language domain you will be using in class (Listening, Reading, Speaking, and/or Writing)

- Find the action verb that you will be using. The action verbs vary based on Bloom’s Taxonomy. Use the chart in this document to help you in deciding on the action verb.

- What is the topic of the lesson?

- Include any scaffolds/supports you will have for the students. A scaffold is teacher added supports for the students so they can master the objective of the lesson.

You May Also Like

Finding a Curriculum: Tips & Strategies

Preparing for the New School Year in the Midst of Uncertainty

Virtual Classroom Management

- I nfographics

- Show AWL words

- Subscribe to newsletter

- What is academic writing?

- Academic Style

- What is the writing process?

- Understanding the title

- Brainstorming

- Researching

- First draft

- Proofreading

- Report writing

- Compare & contrast

- Cause & effect

- Problem-solution

- Classification

- Essay structure

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Book review

- Research proposal

- Thesis/dissertation

- What is cohesion?

- Cohesion vs coherence

- Transition signals

- What are references?

- In-text citations

- Reference sections

- Reporting verbs

- Band descriptors

Show AWL words on this page.

Levels 1-5: grey Levels 6-10: orange

Show sorted lists of these words.

| --> |

Any words you don't know? Look them up in the website's built-in dictionary .

|

|

Choose a dictionary . Wordnet OPTED both

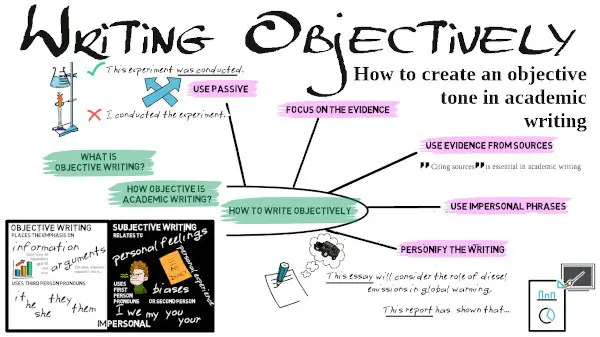

Writing objectively How and when to use an impersonal tone

For another look at the same content, check out the video on YouTube (also available on Youku ). There is a worksheet (with answers and teacher's notes) for this video.

Academic writing is generally impersonal and objective in tone. This section considers what objective writing is , how objective academic writing is , then presents several ways to make your writing more objective . There is also an academic article , to show authentic examples of objective language, and a checklist at the end, that you can use to check the objectivity of your own writing.

What is objective writing?

Objective writing places the emphasis on facts, information and arguments, and can be contrasted with subjective writing which relates to personal feelings and biases. Objective writing uses third person pronouns (it, he, she, they), in contrast to subjective writing which uses first person pronouns (I, we) or second person pronoun (you).

How objective is academic writing?

Although many academic writers believe that objectivity is an essential feature of academic writing, conventions are changing and how much this is true depends on the subject of study. An objective, impersonal tone remains essential in the natural sciences (chemistry, biology, physics), which deal with quantitative (i.e. numerical) methods and data. In such subjects, the research is written from the perspective of an impartial observer, who has no emotional connection to the research. Use of a more subjective tone is increasingly acceptable in areas such as naturalist research, business, management, literary studies, theology and philosophical writing, which tend to make greater use of qualitative rather than quantitative data. Reflective writing is increasingly used on university courses and is highly subjective in nature.

How to write objectively

There are many aspects of writing which contribute to an objective tone. The following are some of the main ones.

Use passive

Objective tone is most often connected with the use of passive, which removes the actor from the sentence. For example:

- The experiment was conducted.

- I conducted the experiment.

- The length of the string was measured using a ruler.

- I measured the length of the string with a ruler.

Most academic writers agree that passive should not be overused, and it is generally preferrable for writing to use the active instead, though this is not always possible if the tone is to remain impersonal without use of I or other pronouns. There is, however, a special group of verbs in English called ergative verbs , which are used in the active voice without the actor of the sentence. Examples are dissolve, increase, decrease, lower, and start . For example:

- The white powder dissolved in the liquid.

- I dissolved the white powder in the liquid.

- The white powder was dissolved in the liquid.

- The tax rate increased in 2010.

- We increased the tax rate in 2010.

- The tax rate was increased in 2010.

- The building work started six months ago.

- The workers started the building work six months ago.

- The building work was started six months ago.

Focus on the evidence

Another way to use active voice while remaining objective is to focus on the evidence, and make this the subject of the sentence. For example:

- The findings show...

- The data illustrate...

- The graph displays...

- The literature indicates...

Use evidence from sources

Evidence from sources is a common feature of objective academic writing. This generally uses the third person active. For example:

- Newbold (2021) shows that... He further demonstrates the relationship between...

- Greene and Atwood (2013) suggest that...

Use impersonal constructions

Impersonal constructions with It and There are common ways to write objectively. These structures are often used with hedges (to soften the information) and boosters (to strengthen it) . This kind of language allows the writer to show how strongly they feel about the information, without using emotive language, which should be avoided in academic writing.

- It is clear that... (booster)

- It appears that... (hedge)

- I believe that...

- There are three reasons for this.

- I have identified three reasons for this.

- There are several disadvantages of this approach.

- This is a terrible idea.

Personify the writing

Another way to write objectively is to personify the writing (essay, report, etc.) and make this the subject of the sentence.

- This essay considers the role of diesel emissions in global warming.

- I will discuss the role of diesel emissions in global warming.

- This report has shown that...

- I have shown that...

In short, objective writing means focusing on the information and evidence. While it remains a common feature of academic writing, especially in natural sciences, a subjective tone is increasingly acceptable in fields which make use of qualitative data, as well as in reflective writing. Objectivity in writing can be achieved by:

- using passive;

- focusing on the evidence ( The findings show... );

- referring to sources ( Newbold (2021) shows... );

- using impersonal constructions with It and There ;

- using hedges and boosters to show strength of feeling, rather than emotive language;

- personifying the writing ( This report shows... ).

Bailey, S. (2000). Academic Writing. Abingdon: RoutledgeFalmer

Bennett, K. (2009) 'English academic style manuals: A survey', Journal of English for Academic Purposes , 8 (2009) 43-54.

Cottrell, S. (2013). The Study Skills Handbook (4th ed.) , Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Hinkel, E. (2004). Teaching Academic ESL Writing: Practical Techniques in Vocabulary and Grammar . Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc Publishers.

Hyland, K. (2006) English for Academic Purposes: An advanced resource book . Abingdon: Routledge.

Jordan, R. R. (1997) English for academic purposes: A guide and resource book for teachers . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Example article

Below is an authentic academic article. It has been abbreviated by using the abstract and extracts from the article; however, the language is unchanged from the original. Click on the different areas (in the shaded boxes) to highlight the different objective features.

Title: Obesity bias and stigma, attitudes and beliefs among entry-level physiotherapy students in the Republic of Ireland: a cross sectional study. Source: : https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031940621000353

| [1] | Nat Rev Endocrinol, 16 (5) (2020), p. 253 |

| [2] | F. Rubino, R.M. Puhl, D.E. Cummings, R.H. Eckel, D.H. Ryan, J.I. Mechanick, et al. Nat Med, 26 (4) (2020), pp. 485-497 |

| [3] | J. Seymour, Jl Barnes, J. Schumacher, Rl. Vollmer Inquiry, 55 (2018), Article 46958018774171 |

| [4] | S.M. Phelan, D.J. Burgess, M.W. Yeazel, W.L. Hellerstedt, J.M. Griffin, M. van Ryn Obes Rev, 16 (4) (2015), pp. 319-32 |

| [5] | J.A.M.M. Sabin, B.A. Nosek PLoS One, 7 (2012), Article e48448 |

GET FREE EBOOK

Like the website? Try the books. Enter your email to receive a free sample from Academic Writing Genres .

Below is a checklist for using objectivity in academic writing. Use it to check your writing, or as a peer to help. Note: you do not need to use all the ways given here.

| The writing is . | ||

| The writing uses to avoid personal pronouns (e.g. ). Passive is not overused. | ||

| The writing (e.g. ). | ||

| The writing uses and third person pronouns (e.g. ). | ||

| The writing uses with and . | ||

| The writing uses (e.g. |

Next section

Read more about writing critically in the next section.

- Critical writing

Previous section

Go back to the previous section about using complex grammar .

- Complex grammar

Author: Sheldon Smith ‖ Last modified: 05 February 2024.

Sheldon Smith is the founder and editor of EAPFoundation.com. He has been teaching English for Academic Purposes since 2004. Find out more about him in the about section and connect with him on Twitter , Facebook and LinkedIn .

Compare & contrast essays examine the similarities of two or more objects, and the differences.

Cause & effect essays consider the reasons (or causes) for something, then discuss the results (or effects).

Discussion essays require you to examine both sides of a situation and to conclude by saying which side you favour.

Problem-solution essays are a sub-type of SPSE essays (Situation, Problem, Solution, Evaluation).

Transition signals are useful in achieving good cohesion and coherence in your writing.

Reporting verbs are used to link your in-text citations to the information cited.

4 Chapter 4: Writing and Teaching to Language Objectives

- All teachers are language teachers.

- Language and content strengths and needs provide a foundation for creating learning objectives.

- Content objectives support facts, ideas, and processes.

- Language objectives support the development of language related to content and process.

- Objectives must be directly addressed by lesson activities.

As you read the scenarios below, think about how your classroom context might be like those of the teachers depicted. Reflect on how you might address the situations these teachers face.

STOP AND DO

Before reading the chapter, discuss with your classmates why the students and the teachers in the scenarios may be having problems. What information or understandings can provide solutions for the teachers?

Both teachers in the chapter-opening scenarios recognize that their students need language help. Like many teachers, however, they have misunderstandings about how language learning occurs, a lack of knowledge about how to integrate content and language, and no notion of why they should. Teachers can help students access the academic content of the class; however, if language is a barrier to access, then they must also consider ways to help learners access the language they need. Contrary to Ms. Alvarez’s belief in the scenario, students do not “absorb” language without scaffolding and focused attention, just like they need for learning content (Crawford & Krashen, 2007). A specific focus on central skills and concepts is critical to learning both language and content. This specific focus on language is important in all classrooms, whether content is presented in an elementary classroom in a thematic unit or in a secondary classroom as a discrete subject. This focus is important because, as we outlined in Chapter 1, each content area has jargon, technical vocabulary, and genre that is specific to that content area. Because ELL and other language teachers may not be well versed in the vocabulary and discourses of all the content areas, regular classroom teachers are probably best suited to teach these types of language with the support of language educators. In essence, all teachers are language teachers to some extent, even if they teach the language of only one content area, as they often do at the secondary level. Chapter 3 focused on understanding students’ needs, backgrounds, and interests. Although content standards and goals for specific grade levels are often prescribed in statewide curricula, the objectives and activities that help learners reach those goals can and should be based on what teachers discover about their students. This chapter focuses on integrating social and academic language needs into content lessons so that all students can access the academic content. An important aspect of teaching language across content areas and themes is understanding how to develop appropriate and relevant language objectives as part of lessons. The development of language objectives and activities that support the objectives is the main emphasis of this chapter.

Understanding Objectives

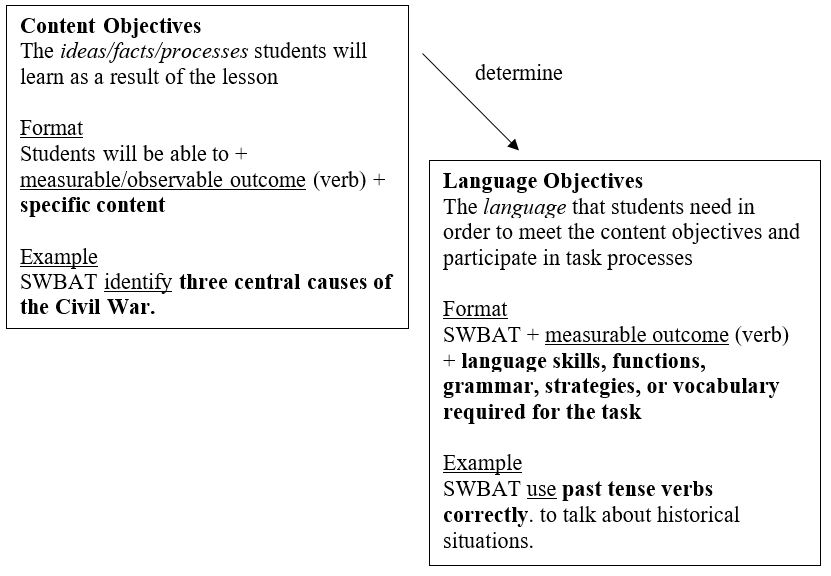

Different texts call learning objectives by different terms, but it is the idea behind them that is important rather than the exact label. In this text, objectives are statements of attainable, quantifiable lesson outcomes that guide the activities and assessment of the lesson. Objectives differ from goals and standards , which can also be called “learning targets” and are very general statements of learning outcomes. Objectives are also different from activities or tasks , which explain what the students will do to reach the objectives and goals. Objectives typically follow a general format, as outlined in the formula below:

“Students will be able to” + concrete, measurable outcome + content to be learned

The three parts of this formula are equally important. First, “students will be able to”—often abbreviated SWBAT—indicates that what follows in the objective are criteria against which a student’s performance can be evaluated after the lesson. Note that starting an objective with the words “Students will” is not the same as SWBAT because “Students will” indicates what activities the students will do rather than the outcomes that they are expected to achieve from participating in the activity. Second, the concrete, measurable outcome presents the criterion that the evaluation will focus on. The chart in Figure 4.1 presents a list of possible action verbs that can be used to state the measurable outcome. Finally, the third part of the objective states the exact content to be learned and sometimes also includes to what degree it should be mastered (100% accuracy, 9 out of 10 times, etc.).

| bstract activate adjust analyze arrange assemble assess associate calculate carry out categorize change classify compare compose | contrast conduct construct criticize critique define demonstrate describe design develop differentiate direct discover distinguish draw | dramatize mploy establish estimate evaluate examine explain explore express rmulate eneralize dentify illustrate infer interpret | introduce investigate list locate modify ame bserve organize erform plan predict prepare produce propose rate | recall recognize record relate reorganize repeat replace report research restate revise select sequence simplify sketch | skim solve state summarize survey test theorize track translate use verbalize visualize rite |

Figure 4.1 Measurable verbs. Source: Adapted from Action Verbs for Learning Objectives © 2004 Education Oasis™ http://www.educationoasis.com

Content objectives

Most mainstream teachers are accustomed to writing content objectives. Content objectives support the development of facts, ideas, and processes. For example, in a unit about the Civil War, one of the content objectives might be:

- SWBAT name three of five central causes of the Civil War in writing.

Others might include

- SWBAT list the major battles of the Civil War.

- SWBAT recite the first section of the Gettysburg Address.

Which objectives the teacher chooses may depend on the dictates of standards, grade-level requirements, and curricula. Whatever criteria are used for choosing them, those objectives should be developed based on what students already know and need to know and provide a strong guide for the development of the rest of the lesson.

Look at the standards and other content requirements for teaching in your current or future area(s). Write one or more content objectives that might be appropriate for the students that you plan to or do teach. Refer to Figure 4.1 for action verbs. Then review others’ objectives and see what questions you still have about content objectives. [1]

Language objectives

Constructing Language Objectives

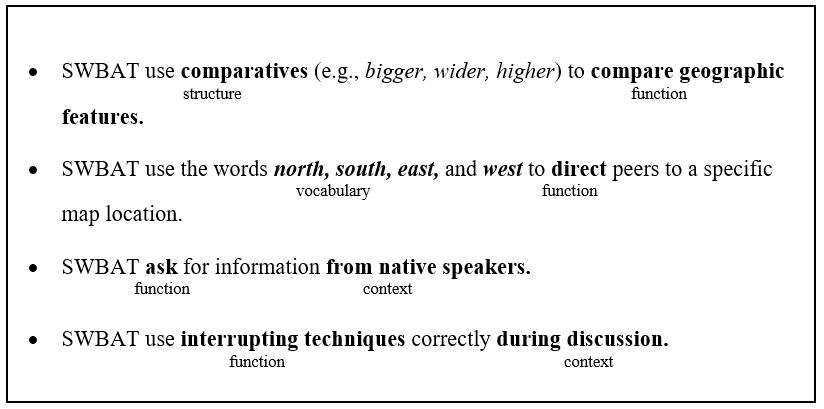

The first step in creating language objectives is to determine social and academic language needs based on content objectives. Language needs can fall into these five general categories (adapted from Echevarria, Vogt, & Short, 2016):

- Vocabulary : Including concept words and other words specific to the content, for example, words that end in -ine , insect body parts, parts of a map, precipitation, condensation, and evaporation.

- Language functions : What students can do with language, for example, define, describe, compare, explain, summarize, ask for information, interrupt, invite, read for main idea, listen and give an opinion, edit, elicit elements of a genre.

- Grammar : How the language is put together (its structure), for example, verb tenses, sentence structure, punctuation, question formation, prepositional phrases.

- Discourse : Ways students use language, for example, in genres such as autobiographies, plays, persuasive writing, newspaper articles, proofs, research reports, speeches, folktales from around the world.

- Language learning strategies : A systematic plan to learn language, for example, determining patterns, previewing texts, taking notes.

For example, the chart in Figure 4.3 shows some of the language in these categories that students might need in order to meet the stated content objective in a lesson on the Civil War.

| Content Objective: SWBAT state | ||||

| slavery North South economy secession federal abolition | Past tense Complete sentences | Narrative and report genres | Identify main ideas. Make a statement. Summarize. Define words. Use cause and effect. Spelling. Arguing. | Take notes. Listen strategically. |

Figure 4.3 Determining language needs.

STOP AND THINK

Can you think of more examples of the five kinds of language listed previously? Can you think of other types of language that students might need in order to meet the content objective in Figure 4.3? Depending on the teacher’s understandings of her students’ language needs and on what she sees as the most important language elements to emphasize, she might choose one or more of the following language objectives for this lesson:

- SWBAT spell the following vocabulary correctly: economy, secession, federal, abolition .

- SWBAT listen carefully for main ideas from a reading on the Civil War .

- SWBAT use past tense verbs to write complete sentences .

| Arctic animals | SWBAT identify the habitats of Arctic animals by writing the name and the place. | Vocabulary like the names of the animals and habitats, spelling, defining. | The names, but not the definitions, of the habitats. | SWBAT write the definitions of Arctic animal habitats. |

| Our Community | SWBAT describe five important community landmarks. | Adjectives, present tense, prepositions of location. | They can use many adjectives but need more. They know simple present tense. | SWBAT use prepositions of location accurately. |

| Ancient Greece | SWBAT explain three contributions to current life made by the ancient Greeks. | Past tense, present tense, sentence format, connectors ( , etc.). | They know how to make past and present tense sentences. | SWBAT use connectors correctly in oral and written texts. |

| Sports | SWBAT demonstrate the rules of American football. | Sequencing ( ); modal verbs ( ); football vocabulary. | They have already learned the vocabulary. | SWBAT use sequencing words to explain a series of events or items |

| Argument | SWBAT compose a five-paragraph argumentative essay. | Essay format, paragraph format, sentence format, topic sentences, conclusions, logic, argument support. | They understand paragraphs and sentences, but they do not know about persuasion/ argument. | SWBAT construct an argument with three reasons to support their position. |

| Graphs | SWBAT compare the effectiveness of pie charts, line charts, and bar graphs given specific data. | Comparatives; vocabulary such as ; present tense | They know the vocabulary. | SWBAT use comparatives to write present tense |

Figure 4.5 Sample objective development process.

Look at Figure 4.5. For each objective, underline the concrete, measurable outcome and circle the content to be learned. Check your answers with a partner. Every content objective does not necessarily require a language objective, and some lessons do not have language objectives at all because all students can access the content with skills and vocabulary that they already possess. However, it is important to examine possible language barriers to content in every lesson and to address them if needed. In summary, the important features of language objectives include the following:

- They derive from the content to be taught.

- They consider the strengths and needs of students.

- They present measurable, achievable outcomes.

First, review the objective(s) you wrote for the Stop and Do about content objectives above. List all of the potential language that students might need in order to access the information and achieve the objective(s). Then choose the most important language, without which students could not possibly access the content, and write one or more language objectives that address this language need.

Teaching to the Language Objectives

Creating language objectives is a good start for addressing the social and academic language needs of students, particularly ELLs, but equally important is that lesson tasks address the objectives. This chapter presents some guidelines for making sure that students meet the language objectives. Chapters 7–11 present specific ideas for teaching to language objectives in a variety of disciplines. Guideline 1: Integrate language and content Just as tasks that address content objectives are integrated into the whole lesson rather than being addressed one by one, language objectives should also be integrated into the lesson and not taught in isolation from it. For example, these objectives were chosen for the Civil War lesson:

- Content: SWBAT state three of five central causes of the Civil War in writing.

- Language: SWBAT use reading strategies to uncover main ideas from a reading on the Civil War.

The teacher could teach about the central causes of the Civil War, separately teach how to identify main ideas, and then hope that the students will apply their knowledge to their Civil War task. This process, however, is problematic in several ways. First, it indicates to students that language is separate from content when it is actually derived directly from the content. In other words, teaching the language objective without content removes much of the context for the language. Second, it breaks up the lesson into chunks, each of which constitutes a separate preparation for the teacher. This is neither an efficient use of the teacher’s and students’ time nor an effective way to teach language. [2] As noted in Chapter 1, some authors believe that all language is contextualized to some extent, but treating language separately from content takes away the specific context that gives the language meaning, making the language more difficult to understand and use. A better choice is for the teacher to integrate the content and language. So, for example, while the students are looking for the causes of the Civil War in their textbooks, the teacher can ask them how they figure out what the causes are, and the students can make a list of strategies to find main ideas. They can practice together by finding the first cause of the Civil War and explaining to each other how they found it. This choice makes the lesson more efficient (by teaching the two objectives at the same time) and effective (helping students see how language and content are related and moving them toward reaching both objectives). Guideline 2: Use pedagogically sound techniques In the past, language was typically taught through drill and practice, exercises with few context clues, and mechanical worksheets. Research has found that these techniques are effective for very few students in very limited contexts. Effective language instruction, in addition to being integrated into content instruction, should meet the following basic criteria:

- It is authentic . This means that it comes from contexts that students actually work in and that it is not stilted or discrete just for grammar study. It is language that students need for a real purpose.

- Language is taught both explicitly and implicitly . Students are both directly exposed and indirectly exposed so they can use strategies to figure out some meaning on their own.

- It is multimodal . Students are exposed to language through different modes such as graphics, reading, and listening, and they can respond in text, drawing, and voice.

- It is relevant . Not all students in a class need all of the language instruction. The teacher can choose to whom the lesson is aimed (small groups, individual students, the whole class) to make it relevant.

- It is based on interaction . Collaboration and cooperation help learners test their assumptions about language.

Guideline 3: Break down the language Each language objective can actually imply a variety of smaller topics. For example, for students to learn past tense, they have to understand what it means in a time sense and also that there are regular and irregular past tense verbs (e.g., those with -ed added, those with alternative changes), different spellings (e.g., go/went), and different pronunciations (e.g., sometimes the -ed ending is pronounced “ed” and sometimes it is pronounced “t”). As with any content, the instructional approach can go whole to part or part to whole or both ways, depending on how students learn best. For example, the teacher might have students read a passage and ask how we know when the events happened (whole) and then review the various aspects of past tense (parts). Or the teacher and students can point out the different aspects of past tense verbs in a required reading first and then work toward a more general understanding of how it helps us know when events occurred. Either way, the parts of past tense should be examined in light of their use in class content. [3] Figure 4.6 summarizes these three basic guidelines for language instruction. Additional guidelines are presented throughout this book.

| Integrate language and content | Contextualize the language instruction by using content as the language source. |

| Use pedagogically sound techniques | Language instruction should be authentic, multimodal, both explicit and implicit, relevant, and based in interaction. |

| Break down the language | Teach wholes and parts to address the different learning needs of students. |

Figure 4.6 Basic guidelines for helping students meet language objectives.

After reading the chapter, what would you tell the teachers in the chapter-opening scenarios to help them with their concerns?

Every teacher is a language teacher, at least in part, because the language of the content areas requires students to learn social and academic language in order to access the content. Teachers can use their content objectives, which support facts, ideas, and processes, to determine language objectives, which support the development of language related to content and process. Then, by following principles of good pedagogy, teachers can integrate the language and content in lesson activities. Following this process helps make learning more efficient and effective and ensures that all students have a chance to succeed. As crucial as this is, the next chapter shows that there are additional important components of lesson design that teachers can master in order to help all students achieve.

For Reflection

- You as a language teacher . How are you, or will you be, a language teacher? Think about the ways you and your students use or will be required to use language in your classroom. What do these uses mean for your teaching?

- Choosing modes . Think about a lesson you have observed or taught. How can you include more modes so that students are exposed to language in a variety of ways?

- Meeting the standards . Choose one of the content standards from your current or future grade level or content area. Develop one or more content objectives and then create language objectives for the same standard.

- Break down language . Choose a grammar point, language function, or discourse. Using any resources that you need to, list all the aspects of your choice and describe how you might use steps to teach your choice to your current or future students.

Crawford, J., & Krashen, S. (2007). English learners in American classrooms: 101 questions, 101 answers . New York: Scholastic. Echevarria, J., Vogt, M., & Short, D. (2016). Making content comprehensible for English learners . Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

- Find state and national standards by content area on the Education World website at http://www.educationworld.com/standards/index.shtml . ↵

- To decontextualize means to consider something alone or take something away from its context. ↵

- In addition to the techniques and strategies described in this text, others can be found in many excellent guides. See, for example, Herrell and Jordan’s (2016) Fifty Strategies for Teaching English Language Learners (5th edition) and Making Content Comprehensible for English Learners: The SIOP Model (5th edition) by Echevarria, Vogt, and Short (2016). ↵

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

Reflections on Teaching Multilingual Learners

Multilingual Learners, SIOP and more…

Writing Effective Language Objectives

Writing language objectives can be hard!

Teachers are generally comfortable writing content objectives because those are based on content standards that teachers are familiar with and are sometimes stated right in curricular materials, e.g., In this unit students will…..

Language objectives, not so much.

Including a language objective in every lesson was popularized by the SIOP Model beginning in 2000 and is now a widely accepted practice. After nearly twenty years, it is the feature about which we continue to receive the most questions, bar none.

In short, content objectives (CO) are related to the key concept of the lesson. Although language objectives (LO) connect to the lesson’s topic or activities, their purpose is to promote student academic language growth in reading, writing, speaking and listening. Writing a LO isn’t always as straightforward as a CO because it is based on an aspect of language that students need to learn. It typically takes more thought and preparation. Fortunately, there are ELL/ELD standards to help guide you in writing language objectives.

In our book, Developing Academic Language , Deborah Short and I provide guidelines for identifying objectives and incorporating them into lessons. These guidelines include determining what we want students to learn (CO) and then considering the language needed to accomplish those objectives (LO). It is important that active, measurable verbs are used in objectives so that learning can be assessed. Students are more likely to take responsibility for their own learning when measurable objectives allow them to gauge their progress. Avoid verbs such as learn, understand, become aware of since these cannot be measured.

In a lesson from a unit on the Lewis and Clark expedition, the unit’s guiding standard is, Explain events, ideas, or concepts in a historical, scientific, or technical text, including what happened and why, based on specific information in the text. A content objective for the lesson might be: Students will identify and describe the main events on the Lewis and Clark expedition .

Language objectives might be: Students will describe the main events using past tense verbs , and Students will categorize vocabulary terms using a List-Group-Label activity .

We promote the practice of posting and discussing objectives with students. An agenda, commonly written by teachers on the board, is a list of activities and is not the same as objectives. Objectives focus on an outcome, not an activity. They are the content-based learning targets students need to be able to accomplish the activities. Remember, objectives are what you want students to know or be able to do by the end of the lesson, so instruction needs to address what you’ve set out to do.

When writing language objectives we suggest that teachers:

- Have a consistent introduction that students recognize . Pick whichever one will resonate with your students: SWBAT (students will be able to), SW (students will), We will , Today I will and so forth .

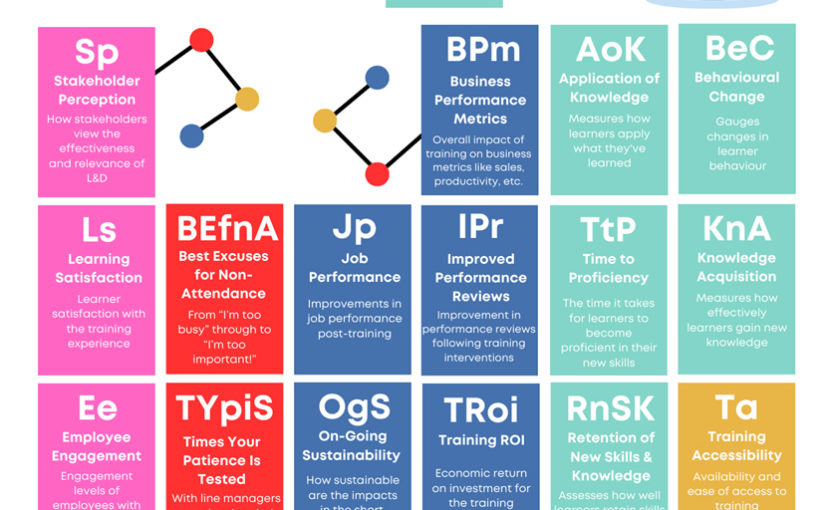

- State the outcome using active, measurable verbs . SIOPer @carlota_holder created this graphic to illustrate some active verbs that may be used across the four domains.. The lists aren’t exhaustive but are a handy reminder of verbs to use. Some, of course, fit in multiple categories. Compare works in writing and speaking as does persuade.

In the listening domain above, the objective would need to include an observable, measurable action such as, Students will listen for details and raise a hand when a key detail is mentioned, or Students will pay attention to the presentation and take notes on the outline provided .

- Focus on the aspect of language students will learn or practice in the lesson . The language feature may need to be explicitly taught or refined and practiced.

So, here’s how a language objective is constructed:

Students will describe the main events using past tense verbs.

Introduction – Active, measurable verb – Language to be learned or practiced

Additional information may be part of the objective, if desired for clarity:

Students will categorize vocabulary terms using a List-Group-Label activity.

Introduction – Active verb – Language learned – Activity

To see objectives in action in a social studies classroom, click here .

One thing is certain, the more you practice writing language objectives, the easier it becomes. Keep in mind a quote from SIOP expert Andrea Rients (@RientsAndrea), “Nobody dies from writing a bad language objective” to which another veteran SIOPer Ana Segulin ( @asegulin) replied, “A bad language objective is better than NO language objective.”

Post based on : Short, D. & Echevarria, J. (2016). Developing Academic Language Using the SIOP Model . Boston: Pearson.

Echevarria, J., Vogt, M.E. & Short, D. (2017). Making Content Comprehensible for English Learners: The SIOP ® Model, Fifth Edition. Boston: Pearson.

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Mrs.Judy Araujo, M.Ed.,CAGS, Reading Specialist

Donations are appreciated to help alleviate the maintenance fees for this unsponsored website. Receive a Word doc of any of my pages with your donation. Thank you! :)

Writing ELA Objectives

This page will teach you all about writing ELA objectives.

See content and language objectives at the bottom of the page..

ASK YOURSELF: What do you want your students to learn as a result of the lesson?

- IEP Goal Bank comes in handy to write objectives, too!

- Education Oasis ~ Stems

- See also writing Content and Language Objectives on my RETELL page .

- Also, check out Hundreds of Free Lesson Plans !

Writing ELA Objectives in 3 easy steps: create a stem, add a verb, and determine the outcome.

Step 1: CREATE A STEM

- After completing the lesson, the students (we) will be able to. . .

- After this unit, the students (we) will. . .

- By completing the activities, the students (we) will. . .

- During this lesson, the students (we) will. . .

Make the stems kid-friendly! 🙂

Step 2: ADD A VERB

- After completing the lesson, the students (we) will be able to predict . . .

- After this unit, the students (we) will distinguish . . .

- By completing the activities, the students (we) will construct . . .

- During this lesson, the students (we) will defend . . .

Step 3: DETERMINE ACTUAL PRODUCT, PROCESS, OUTCOME

OBJECTIVE SAMPLES ~ notice how the objectives become more challenging as we move through Bloom’s Taxonomy. Try to teach towards the upper end of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

The student will. . .

KNOWLEDGE:

- Draw scenes from chapter_______. Under each scene, describe what is happening.

- Use a story map to show the events in chapter ________.

- Draw a cartoon strip of the chapter’s beginning, middle, and end.

- List the story’s main events.

- Make a timeline of events.

- Make a facts chart.

- List the pieces of information you remember.

- Make an acrostic.

- Recite a poem.

- Make a chart showing. . .

COMPREHENSION:

- Draw a picture that summarizes the chapter. Then, write a sentence that tells about the picture.

- Summarize the chapter in your own words in one paragraph.

- Summarize the chapter in your own words in two paragraphs.

- Cut out or draw pictures to show an event in the story.

- Illustrate the main idea.

- Make a cartoon strip showing the sequence of events.

- Write and perform a play based on the story.

- Make a coloring book based on the story.

- Retell the story.

- Paint a picture of your favorite part.

- Prepare a flow chart of the sequence of events.

- Write a summary.

APPLICATION:

- Be a new character to the story. Tell the story’s ending would change.

- With a partner, change the ending of the story. One person will be a new character, and the other be a character from the book.

- In a group, act out the ending of the story.

- Construct a model to demonstrate how something works.

- Make a diorama to illustrate an important event.

- Compose a book about. . .

- Make a scrapbook about. . .

- Make a paper-mache map showing information about. . .

- Make a puzzle game using ideas from the book.

- Make a clay model of. . .

- Paint a mural of . . .

- Design a market strategy for a product.

- Design an ethnic costume.

ANALYSIS:

- Take an event in the text. Make a text-to-world connection.

- Take an event from the story and make a text-to-text connection.

- Take an event from the story and make a text-to-self connection.

- Design a questionnaire to gather information.

- Make a flow chart to show critical stages.

- Write a commercial for the book.

- Review the illustrations in terms of form, color, and texture.

- Construct a graph to illustrate selected information.

- Construct a jigsaw puzzle.

- Analyze a family tree showing relationships.

- Write a biography about a person being studied.

SYNTHESIS:

- Design a list of 10 solutions to help a character solve a problem.

- Write a dialogue between you and one of the characters in the book. Then, help the character solve a problem.

- Meet with a partner and role-play how to solve one of the character’s problems.

- Invent a machine to do specific tasks from the text.

- Design a building.

- Create a new product, name it, and plan a marketing campaign.

- Write about your feelings concerning. . .

- Write a tv show, a puppet show, pantomime, or sing about. . .

- Design a book or magazine cover about. . .

- Devise a way to. . .

- Create a language code. . .

- Compose a rhythm or put new words in a melody.

EVALUATE:

- Choose a character and fill out a T chart. Then, express your opinion of the character using 3 pieces of evidence from the book.

- Choose a character and fill out a T chart to express your opinion of the character. Then, come up with one good detail and discuss it with a partner.

- Choose a character from the book. Express your opinion of this character using 5 pieces of evidence from the book in T chart form. Use the T chart, and then write a paragraph.

- Prepare a list of criteria to judge the book. Indicate priority and ratings.

- Conduct a debate about an area of special interest.

- Make a booklet about 5 qualities a character in the book possesses.

- Form a panel to discuss a topic. Discuss criteria.

- Write a letter to_____ advising changes needed.

- Prepare arguments to present your view about. . .

MORE OBJECTIVE SAMPLES…

|

|

|

|

| After completing the lesson, the students (we) will be able to:

|

MORE OBJECTIVES…

Reading comprehension.

- The student will use prereading strategies to predict what the story is about on a post-it note. The student will explain whether their prediction was confirmed at the end of class, with supporting details from the text.

- During the lesson, the student will generate a list of questions about the story as they read.

- After completing the lesson, the student will be able to make generalizations and draw conclusions about the events in the story by citing three examples.

- After reading the text, the student will be able to answer questions about the story’s meaning.

- At the end of the lesson, the student will be able to summarize the passages.

- By completing the activities, the student will be able to discuss interpretations of the story.

- After reading the text, the student will cite passages to support questions and ideas.

- The student will use context to figure out word meanings and write these meanings on the post-it notes.

- During this lesson, the student will read with a purpose and take notes to monitor comprehension.

- During this lesson, the student will practice various reading strategies and explain how two strategies were used.

- By the end of this unit, the students will apply critical reading strategies to identify main ideas in short passages with 70% mastery.

Critical Thinking

- During this lesson, the student will generate ideas with a clear focus in response to questions.

- By the end of this lesson, the student will support ideas with relevant evidence.

- The students will respond to other students’ ideas, questions, and arguments.

- During this lesson, the students will question other students’ perspectives in a debate.

- By the end of this lesson, the students will present ideas logically and persuasively in writing.

Listening and Speaking

- During this lesson, the student will demonstrate comprehension of stories as they are read aloud by participating in every pupil response activity.

- By the end of this lesson, the students will listen actively and carefully to others and retell others’ opinions and ideas.

- During this lesson, the students will respond to other students’ questions while actively participating in a group discussion.

Writing Content and Language Objectives

A Great Resource!

*** PDF of Content and Language Objective Verbs ***

Great examples and step-by-step directions!

Copyright 09/12/2012

Edited on 03/07/2024

Adapted from Education Oasis Curriculum Resources.

Copyscape alerts me to duplicate content. Please respect my work.

English Studies

This website is dedicated to English Literature, Literary Criticism, Literary Theory, English Language and its teaching and learning.

Essay Writing, Objectives, and Key Terms in Essay Writing

Etymology and meanings of the term “essay”.

Etymologically, the term “essay” originates from the French word “essayer.” In the French context, it means means “to try” or “to attempt.” It seems to have originated in the 16th century when Michel de Montaigne, a French philosopher and perhaps the first essayist, popularized the genre with his collection of personal reflections and thoughts called Essais . Since then, this term has taken up several shapes, names, and meanings.

Whereas its gist is concerned, the word “essay” reflects the idea of an intellectual endeavor, or an attempt made to explore a particular topic, or express one’s point of view coherently.

In the composition form, an essay is a form of written composition. It is a concise, well-organized, and coherent argument, or discussion on a specific topic. It also is a literary genre that allows individuals to express their thoughts, ideas, and opinions, providing evidence and proof to support their claims.

Essays typically follow a structured format, including an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. This structure enables the authors to present their arguments logically and persuasively. In an academic setting, it is a requirement to pass a certain course. Therefore, its format could take several shapes such as descriptive, narrative, persuasive, expository, or argumentative, covering a wide range of topics, including but not limited to literature, science, history, philosophy, technology, etc. The main objective, however, is to communicate ideas effectively and engage readers in a thoughtful exploration of a subject. In an academic setting, its main objective is to develop the writing skills of the students to learn the same thing – communicating clearly and concisely.

What Is Essay Required in Academic Writing? What are its Main Objectives?

- Demonstrate Knowledge: The essay provides students an opportunity to demonstrate their understanding of a subject or topic, using the knowledge they gain during a specific.

- Develop Critical Thinking Skills : The essay writing exercise encourages students to think critically, analyze information, and evaluate different perspectives. It helps them to develop skills in high-order thinking such as reasoning, logic, and problem-solving.

- Enhance Research Skills: Essays often require students to research for information and support their arguments. This helps students to improve their research skills such as finding credible sources, evaluating those sources for credibility and legitimacy, and integrating them into their writing as evidence to support their arguments.

- Communicate Ideas Clearly: Writing essays helps students to develop the ability to communicate ideas clearly and make coherently. This practice enables them to organize their thoughts, articulate their perspectives, and present complex concepts in an academic style.

- Develop Writing Skills: Essays provide an opportunity for students to improve their writing skills such as grammar, sentence structure, writing style, vocabulary, and usage. It also allows them to practice expressing their ideas effectively in writing.

- Foster Critical Reading: Writing essays often requires students to read and analyze various sources. This promotes critical reading skills in the students, enabling them to engage with scholarly literature, evaluate arguments, and extract relevant information from texts to enter an academic and research dialogue.

- Promote Time Management and Planning: The process of writing an essay involves planning, organizing ideas, and managing time effectively. It helps students to develop skills in setting priorities, meeting deadlines, and breaking down larger tasks into manageable steps.

- Encourage Originality and Creativity: Essay writing exercises provide students an opportunity to learn to express their original ideas, interpret them further, and develop unique and personal perspectives on a given topic. It also encourages them to be creative in formulating and writing arguments and having different insights into issues.

- Assess Learning and Understanding: Essays serve as an assessment tool for educators to evaluate students’ comprehension, synthesis of information, critical thinking abilities, and writing proficiency. They also allow educators to evaluate the depth of students’ understanding of the subject matter.

These objectives highlight how essays are important in academic writing, emphasizing their role in knowledge demonstration, critical thinking development, research skills enhancement, effective communication, and academic growth of the students. However, writing an essay requires students to know certain jargon about this specific academic activity. Some key terms in essay writing are as follows.

Key Terms in an Essay

- Thesis Statement: It is a clear, concise and synthesized statement. It presents the main argument of the essay. It occurs at the end of the introduction in a common essay.

- Introduction: It is the opening paragraph(s) of the essay. It introduces the topic with a hook that arrests the attention of the readers, provides background information, and presents the thesis statement. In most essays, it is just a single paragraph, while in big essays it could have two or even three short paragraphs.

- Body Paragraphs: It is the main section(s) of the essay that develops and supports the thesis statement by presenting evidence, analysis, and arguments.

- Topic Sentence: It is a sentence at the beginning of a paragraph that introduces the main idea or argument of that specific paragraph.

- Evidence: It includes information, examples, data, or research findings that support the claims and arguments made in the essay.

- Analysis: It is the examination and interpretation of evidence, connecting it to the main argument and demonstrating its relevance and significance.

- Counterargument: It is an opposing viewpoint or argument that challenges the main argument of the essay. The main body of the essay addresses and refutes this argument.

- Conclusion: It is the final paragraph(s) of the essay. It summarizes the main points, restates the thesis statement, and provides a closing thought or call to action.

- Transitions: Words or phrases that connect ideas, sentences, or paragraphs, providing a smooth flow and logical progression of thoughts.

- Citation: It means to acknowledge the sources and refer to them within the text through intext citation. It ensures to give proper credit to the original authors and avoid plagiarism.

- Paraphrase: It means restating someone else’s ideas or information in one’s own words, while still attributing the original source. However, in some cases, it is considered an overall rewriting task or recreating task.

- Synthesis: It is the process of integrating information from various sources or perspectives to develop a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

- Coherence: It is the logical and smooth connection between ideas and paragraphs, ensuring that the essay is easy to follow and understand.

- Academic Style: The formal and objective writing style appropriate for academic essays, characterized by clarity, precision, and adherence to disciplinary conventions.

- Revision: It is the process of reviewing and refining the essay, focusing on improving clarity, coherence, and overall effectiveness.

These key terms help students and writers to provide structure, clarity, and cohesion to their essays, enabling them to effectively communicate their arguments and ideas to their readers and audience.

More from Essay Writing:

- Reflective Essay: How to Write it

- Persuasive Essay

- Debatable Thesis Statement

- Essay Outline: Common Questions

- Essay Outlines: Common Questions

- Sissy Jupe: A Paragon of Humanism in the Midst of Capitalism

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Objective Writing: Student Guidelines & Examples

- Icon Calendar 9 August 2024

- Icon Page 2367 words

- Icon Clock 11 min read

A primary purpose of higher learning is to communicate ideas effectively through objective thinking and writing. Basically, teachers expect students to present accurate findings, concerning a specific matter and use verifiable evidence. Moreover, a particular objective method is unique because it allows one to gather, calculate, or evaluate information. In turn, objective writing enables people to present irrefutable facts, apply critical thinking styles, maintain a neutral tone, and use formal and explicit language.

What Is Objective Writing and Its Purpose

According to its definition, objective writing is a specific style and form of communication that presents information and ideas without bias, emotions, or personal opinions. Unlike subjective writing, which includes personal opinions and emotions, objective one relies on evidence, statistics, and verifiable data to convey its message. For example, the main purpose of objective writing is to provide readers with factual, clear, and unbiased information, allowing them to form their own conclusions (Lindsey & Garcia, 2024). Moreover, this approach is especially important in various contexts, like academic papers, news reporting, and technical documentation, where a particular integrity of the information is crucial. By eliminating personal bias and focusing solely on clear facts, such compositions allows a reader to make informed and well-articulated decisions based on the information provided (Barnett & Gionfriddo, 2016). In terms of pages and words, the length of objective writing depends on academic levels, specific requirements, and study disciplines, while general guidelines are:

High School

- Length: 1-3 pages

- Word Count: 250-750 words

- Context: High school assignments often include essays, reports, or short research papers. A key focus is on developing basic academic skills and an ability to present facts clearly and objectively.

- Length: 2-4 pages

- Word Count: 500-1,000 words

- Context: College-level compositions often involve more detailed essays, research papers, and reports. A particular expectation is for more in-depth analysis and an entire use of multiple sources to support an objective presentation of information.

- Length: 3-5 pages

- Word Count: 750-1,250 words

- Context: At a university level, assignments become more complex and detailed, with an emphasis on critical thinking, research, and an ability to present information in an unbiased manner.

Master’s

- Length: 4-10 pages

- Word Count: 1,000-2,500 words

- Context: Master’s level papers involves comprehensive research papers, theses, or projects that require extensive research, analysis, and a particular presentation of information with a high level of objectivity and academic rigor.

- Length: 6-20+ pages

- Word Count: 1,500-5,000+ words

- Context: Ph.D. works, such as dissertations or research articles, demands original research, deep analysis, and a thorough presentation of findings. Objective compositions at this level are expected to be detailed, unbiased, and contribute to a specific field of study.

| Type | Context | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Essay (Any Type) | To explore a specific topic or argument in a structured format, often with an objective perspective. | High school, college, and university assignments. |

| Research Paper | To present findings from a systematic investigation or study. | Academic settings (high school, college, university, and graduate studies). |

| Report | To provide a detailed account of a specific topic, event, or experiment. | Academic assignments, business, technical fields, and scientific studies. |

| Technical Writing | To explain complex information clearly and concisely. | Manuals, guides, instructions, engineering, and information technology (IT) fields. |

| News Article | To inform a public about current events or issues without bias. | Journalism and media outlets. |

| Literature Review | To summarize, analyze, and examine existing research on a particular topic. | Academic research, thesis, and dissertation writing. |

| Scientific Paper | To communicate new research findings and contribute to scientific knowledge. | Academic journals, conferences, and research institutions. |

| Case Study | To analyze a specific instance, event, or organization in detail. | Business, social sciences, healthcare, and education. |

| Lab Report | To document and analyze the results of a laboratory experiment. | Science courses and research labs. |

| White Paper | To inform or persuade decision-makers on a specific issue or solution. | Business, government, and technology sectors. |

| Policy Analysis | To objectively evaluate and compare public policies or proposals. | Government, public administration, and think tanks. |

| Thesis/Dissertation | To present original research and contribute to an academic field. | Master’s and Ph.D. programs. |

| Annotated Bibliography | To provide summaries and evaluations of sources on a specific topic. | Research preparation and academic studies. |

| Systematic Review | To compile and assess all relevant studies on a particular research question. | Healthcare, social sciences, and academic research. |

| Business Report | To analyze business operations, strategies, or market conditions. | Business courses and corporate settings. |

| Section | Content |

|---|---|

| Title (separate page) | A concise and clear title that reflects a specific content of a whole essay or research paper. |

| Abstract/Executive Summary (optional/separate page) | A brief summary of an entire content, highlighting key points or findings. |

| Introduction (1 paragraph) | An introduction to a chosen topic, outlining a specific purpose and scope of objective writing. |

| Thesis Statement (1 sentence) | A clear statement of a main argument or focus of an entire composition. |

| Body (1 or more paragraphs) | A main content divided into sections or paragraphs with subheadings. |

| Conclusion (1 paragraph) | A summary of key points, findings, or arguments presented. |

| List of References (separate page) | A list of all the sources cited or referenced in an entire paper on accordance with APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, or Harvard citation rules. |

Note: Some sections of objective writing can be added, deleted, or combined with each other, and such a composition depends on what an author intends to share with readers. For example, a key feature of objective writing is a particular use of unbiased and factual language that presents information based on evidence rather than personal opinions or emotions (Lindsey & Garcia, 2024). Besides, an objective writing method is a technique that involves presenting information and arguments in a neutral, unbiased, and fact-based manner without allowing personal opinions or emotions to influence an entire content. Further on, subjective writing expresses personal opinions, emotions, and perspectives, while objective one presents information and facts in an unbiased and neutral manner without personal influence. In turn, an example of objective writing is a research paper that presents data and findings from a study without bias or personal interpretation, allowing readers to draw their own conclusions (Snyder, 2019). Finally, to start objective writing, people begin with a clear and factual statement that introduces a specific topic without personal opinions or emotional language.

Steps on How to Be Objective in Writing

To write objectively, people clearly state a specific goal or purpose in a concise and measurable way, focusing on a desired outcome without personal bias or emotional language.

- Understand Your Purpose: Clearly define a specific goal of your composition to focus on delivering unbiased information.

- Research Thoroughly: Gather all the necessary information from credible sources to ensure accuracy and a balanced perspective.

- Avoid Personal Bias: Keep personal opinions and emotions out of your essay or research paper to maintain objectivity.

- Use Neutral Language: Choose words that are impartial and avoid emotionally charged or persuasive language.

- Stick to Facts: Present verifiable facts and data rather than speculation or assumptions.

- Consider Multiple Viewpoints: Acknowledge different perspectives to provide a well-rounded analysis.

- Cite Sources Properly: Give credit to all sources of information, ensuring transparency and credibility.

- Edit for Objectivity: Review your document to eliminate any unintentional bias or subjective language.

- Be Transparent About Limitations: Clearly state any limitations in your research or analysis to avoid misleading readers.

- Seek Feedback: Have others review your work to identify any potential bias or subjective elements you might have missed.

Presenting Facts

In simple words, objective writing is a factual process that enhances knowledge. For example, students gather facts that support a selected topic and support arguments with evidence from credible sources (Moran, 2019). Besides, they need to address both sides of an opinion. Then, being objective makes essays or research papers appear professional and reliable. In turn, people avoid making judgments and remain fair in their final works (Kraus et al., 2022). As a result, this strategy allows individuals to present accurate information that addresses existing knowledge gaps. In turn, some examples of sentence starters for beginning any writing objectively are:

- Based on the available evidence, it can be concluded that … .

- A thorough review of existing knowledge and literature indicates that … .

- According to a comprehensive analysis of the data, it is evident that … .

- Research conducted by [Author/Institution] suggests that … .

- The findings from various studies consistently show that … .

- An examination of the facts reveals that … .

- Objective analysis of a given situation indicates that … .

- A particular consensus among experts in a field is that … .

- Documented evidence supports the conclusion that … .

- In light of the data presented, it is clear that … .

Using Critical Thinking Skills

Objective writing is unique because it enhances critical thinking. For example, students evaluate, calculate, and verify an obtained set of information (Flicker & Nixon, 2016). In this case, they must gather relevant details and determine their significance to a chosen subject. Besides, people must ensure an intended audience attains a deeper understanding of a presented topic. Therefore, authors need to appraise information to achieve desired goals.

Maintaining a Neutral Tone

Objective writing is essential because it allows students to use a neutral tone. For example, an objective tone is a neutral and impartial manner of writing that focuses on presenting facts and information without emotional influence or personal bias (Lindsey & Garcia, 2024). In this case, one should not use opinionated, biased, or exclusive language. Further on, authors must submit unbiased information to a target audience and allow readers to determine their opinions. However, imbalanced information does not persuade a target audience to accept a narrow way of thinking (Moran, 2019). In turn, such an approach helps writers to present relevant facts about a specific subject. Thus, scholars need to learn how to maintain an objective and neutral tone since this method allows them to be less judgmental.

Following a Formal Style

Objective writing is an essential skill because it helps students to follow a formal style. Basically, academic papers must use official and formal language, and students must avoid personal pronouns (Lindsey & Garcia, 2024). As such, an extensive use of a third person enhances an overall clarity of an assignment. Then, following a formal style helps scholars to avoid intensifiers that exaggerate their arguments. For example, people should avoid words, like “very” and “really,” since they make information vague (Barnett & Gionfriddo, 2016). Besides, scholarly papers require a proper use of punctuation marks. In turn, successful learners proofread their works to ensure they use commas and full stops effectively. Moreover, this approach prevents all forms of miscommunication. As a result, people need to follow standard rules of objective writing because it trains them to maintain a formal tone in their papers.

Expressing Ideas

Objective writing allows students to express ideas explicitly. In this case, they need to develop precise sentences to express their thoughts. For example, to write in objective language, people use neutral and factual words that avoid personal opinions, emotions, or biases, focusing solely on evidence-based information (Lindsey & Garcia, 2024). Besides, this approach helps essays to stand out, while students can make their work comprehensible. Hence, people need to learn key features of objective thinking because it allows them to communicate clearly.

What to Include

| Example | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Facts | Verified information that can be proven to be true. | To provide a solid foundation of truth for objective writing. |

| Statistics | Numerical data that quantifies information. | To support arguments with measurable evidence. |

| Research Findings | Results from studies, experiments, or investigations. | To present evidence derived from systematic inquiry. |

| Expert Opinions | Insights or interpretations from individuals with specialized knowledge. | To enhance credibility by referencing authoritative sources. |

| Historical Events | Documented occurrences from the past. | To provide context and support claims with real-world examples. |

| Case Studies | In-depth analysis of specific instances or examples. | To illustrate points with detailed, real-world examples. |

| Definitions | Clear explanations of key terms or concepts. | To ensure readers understand essential terminology. |

| Comparisons | Objective evaluation of similarities and differences between items. | To help clarify ideas by showing relationships between different elements. |

| Quotations From Sources | Direct excerpts from credible texts or authorities. | To provide evidence and authority to the discussion. |

| Data From Surveys or Polls | Information gathered from surveys or polls, reflecting public opinion or trends. | To add quantitative backing to arguments with up-to-date information. |

Common Mistakes

- Using Biased Language: Inadvertently including words or phrases that convey personal opinions or emotions.

- Ignoring Counterarguments: Failing to acknowledge opposing viewpoints, which can make an entire composition appear one-sided.

- Cherry-Picking Data: Selecting only a particular data that supports a specific viewpoint, leading to a biased representation of information.

- Overgeneralizing: Making broad statements without sufficient evidence, which can lead to inaccurate conclusions.

- Failing to Cite Sources: Not properly attributing information to its original source, reducing credibility and transparency.

- Assuming a Reader’s Agreement: Writing as if a reader already shares your perspective, which can undermine objectivity.

- Relying on Anecdotes: Using personal stories or isolated examples instead of comprehensive evidence, which weakens the objectivity.

- Using Absolutes: Employing terms, like “always” or “never,” that leave no room for exceptions or nuances.

- Misinterpreting Data: Drawing conclusions that are not fully supported by presented evidence, leading to misleading statements.

- Overusing Jargon: Using specialized language that may confuse readers and obscure an objective presentation of information.

Objective writing requires people to cover irrefutable facts. Basically, such a process is unique because it enables students to develop critical thinking skills when completing assignments. Furthermore, they should learn key features of objective writing because they gain a particular ability to follow a neutral tone. In turn, students can learn how to write objectively by using a formal and neutral style and improve an overall quality of their academic essays or research papers.

Barnett, D. L., & Gionfriddo, J. K. (2016). Legal reasoning and objective writing: A comprehensive approach . Wolters Kluwer.

Flicker, S., & Nixon, S. A. (2016). Writing peer-reviewed articles with diverse teams: Considerations for novice scholars conducting community-engaged research. Health Promotion International , 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daw059

Kraus, S., Breier, M., Lim, W. M., Dabić, M., Kumar, S., Kanbach, D., Mukherjee, D., Corvello, V., Piñeiro-Chousa, J., Liguori, E., Palacios-Marqués, D., Schiavone, F., Ferraris, A., Fernandes, C., & Ferreira, J. J. (2022). Literature reviews as independent studies: Guidelines for academic practice. Review of Managerial Science , 16 (8), 2577–2595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00588-8

Lindsey, M., & Garcia, H. (2024). Engaging writing activities: Objective-driven timed exercises for classroom and independent practice . Rowman & Littlefield.

Moran, J. (2019). First you write a sentence: The elements of reading, writing … and life . Penguin Books.

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research , 104 , 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

To Learn More, Read Relevant Articles

Essay on Education

- Icon Calendar 5 December 2019

- Icon Page 708 words

Academic Articles

- Icon Calendar 26 November 2019

- Icon Page 560 words

What is Objective Writing? Why Neutral Language Matters

What is objective writing? Master the skill of delivering unbiased information effectively with proven techniques and examples.

In today’s world, the way we present ideas and data can shape opinions, influence decisions, and impact the world around us. One of the most important principles of communication is objectivity. Objective writing is writing that presents information in a neutral and unbiased way. This means avoiding personal opinions, beliefs, or biases. It also means avoiding using emotional language or making subjective statements. Objective writing is typically clearer and easier to understand than subjective writing. It is also seen as more credible and trustworthy. This is because readers know that the writer is not trying to persuade them or influence their opinions.

Related article: Mastering Critical Reading: Uncover The Art Of Analyzing Texts

In a world where there is so much information available, it is more important than ever to be able to distinguish between objective and subjective writing. Objective writing is essential for fostering critical thinking and making informed decisions. This article will explore the importance of objective writing and its role in communication. We will look at how objective writing can be used to foster credibility, deliver accurate information, and promote critical thinking.

What Is Objective Writing?

Objective writing is a style of writing that presents information in a neutral and unbiased manner, without expressing personal opinions, emotions, or beliefs. The primary goal of objective writing is to provide facts, evidence, and logical reasoning to inform the reader without trying to persuade or influence their opinion.

About the question “What is objective writing?”, the author, in this kind of writing, strives to eliminate any potential bias, avoid making value judgments, and maintain a professional and impartial tone. This type of writing is commonly used in news reporting, scientific research papers, academic essays , and other forms of non-fiction writing.

Benefits Of Writing Objectively

Clarity and Understanding: Objective writing presents information in a clear and unbiased manner, allowing readers to conceive the facts without being influenced by the writer’s personal opinions or emotions. This promotes a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Credibility and Trustworthiness: Objective writing enhances the credibility of the writer and the content. When information is presented without bias, readers are more likely to trust the accuracy and reliability of the material.

Unbiased Evaluation: Objectivity enables fair evaluation of different viewpoints, arguments, and evidence. It allows readers to form their own opinions based on the presented facts, rather than being persuaded by the writer’s subjective views.

Professionalism in Academic and Formal Writing: In academic and formal settings, objective writing is expected as it upholds the standards of professionalism and integrity in research, essays, and reports.

Conflict Resolution: Objective writing is particularly valuable in discussions and debates, as it helps to reduce conflicts by focusing on facts rather than personal feelings or biases.

Avoiding Stereotypes and Prejudices: Writing objectively helps to avoid reinforcing stereotypes and prejudices, promoting a more inclusive and open-minded perspective.

Enhanced Critical Thinking: By analyzing information objectively, writers and readers can engage in deeper critical thinking, questioning assumptions, and considering alternative viewpoints.

Appropriate in Scientific and Technical Fields: In scientific and technical writing, objectivity is essential to maintain the accuracy and validity of research findings and technical information.

Global Audience Accessibility: Objective writing is more accessible to a diverse global audience, as it transcends cultural and individual differences, making the content relevant to a broader readership.

Ethical Reporting: Journalists and reporters strive for objectivity in their news reporting to provide unbiased and truthful information to the public, upholding ethical standards in journalism.

Overall, writing objectively fosters transparency, fairness, and respect for differing perspectives, contributing to more informed, trustworthy, and inclusive communication.

Subjectivity Writing

Subjectivity and objectivity are two fundamental aspects of writing that influence how information is presented and perceived. Subjectivity refers to the presence of personal opinions, feelings, and biases in writing. It involves the writer’s perspective, emotions, and interpretations, which can impact how they convey information to the reader.

What Is Subjective Writing?