- Latest News

- North & East

- Environment

- International

- Social Love

- Horse Racing

- World Champs

- Commonwealth Games

- FIFA World Cup 2022

- Art & Culture

- Tuesday Style

- Food Awards

- JOL Takes Style Out

- Design Week JA

- Black Friday

- Relationships

- Motor Vehicles

- Place an Ad

- Jobs & Careers

- Study Centre

- Jnr Study Centre

- Supplements

- Entertainment

- Career & Education

- Classifieds

- Design Week

In defence of Ja’s cultural identity

A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots.

— Marcus Garvey

OVER the years, a lot has been said and written about Jamaica’s cultural identity. Jamaica’s motto “Out of Many One People” aptly describes the melting pot development of the Jamaican society. The composition of the Jamaican society is predominantly made up of people of African descent. However, there are also white Jamaicans, Indo-Jamaicans, Chinese Jamaicans, as well as Jamaicans of lighter skin tone who have intermixed with other ethnic groups to produce a culturally rich and diverse people.

Jamaica has a common heritage with many other Caribbean islands. This common heritage has been interwoven by the experiences of the transatlantic slave trade, exploitation, colonialisation, and emancipation from slavery. Our proximity to North America, mainly the United States of America, has played a significant role in impacting Jamaica’s cultural identity. In fact, there are many who are of the opinion that Jamaica no longer has a true authentic culture due to the cross-fertilisation of both cultures.

Jamaicans have always had an obsession with most things ‘foreign’. Jamaicans have become accustomed to a way of life which largely has been void of the historical trappings of our African ancestry, and this has been replaced with a developed Eurocentric taste. For the most part, the media should take some responsibility for the reshaping of the Jamaican culture. Africa is often portrayed as war-torn, and a famine- and disease-ridden continent. The media has had to take responsibility for misinforming and poorly educating its audience (the world), much to the disservice of its mandate to teach as it ignored the positive side of Africa.

Despite a slowdown in the global economic recovery, Africa continues to be one of the fastest-growing regions in the world today. According to the African Development Bank (ADB), the economic boom in Africa is not only confined to the continent’s natural resources, but incorporates less traditional areas, such as retail commerce, transportation, telecommunications, and manufacturing, which are all areas expected to grow by leaps and bounds. An ADB report projects that, by 2030, consumer spending will increase from US$680 billion in 2008 to US$2.2 trillion. This is indeed remarkable news and augurs well for the future of the continent.

A working definition of culture is of utmost importance in any discussion regarding cultural identity. The term culture means different things to different people. However, there are some basic tenets that must be incorporated in the definition of culture, such as reference to the arts, beliefs, customs, food, dress, institutions and other entities of human thought. I dare say that culture is very much a dynamic process and is ever-evolving.

Despite efforts by our Caricom leaders to integrate the Caribbean Community, the Caribbean as a region is no way closer to full integration today in 2015 than it was when the original Treaty of Chaguaramas was signed on July 4, 1973.

The Jamaican culture refers to human activities within different aspects of everyday life that relate to Jamaican traditions. Most Jamaicans easily identify more with our North American neighbours in the United States of America and Canada than their neighbours in the Caribbean region. The distance, cost of travel, and other cultural nuances associated with movement throughout the Caribbean region makes it less attractive for Caribbean peoples to visit each other in their respective islands. Additionally, there is a perception among many Jamaicans that they are not welcome in other Caribbean territories. This perception has become the reality for a significant number of Jamaicans and was reinforced recently by the Shanique Myrie versus Barbados case.

Jamaican Shanique Myrie was denied entry into Barbados, she subsequently sued for being assault — the term finger-rape became part of our lingua, taken from an Observer headline — and the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) awarded her costs against the Barbadian Government. The perception many have of Jamaicans tends to be one clothed in negativity. Oftentimes Jamaicans are described as overly aggressive. Aggression has a different connotation than assertiveness. The fact is most Jamaicans are assertive, and this is probably a direct result of our forefathers’ history of slavery and the inhumane conditions they experienced during the Middle Passage. There is no way a people could have endured such harsh conditions, packed together like sardines abroad ships, and emerge from that experience without some level of assertiveness, and yes, aggression.

The Jamaican cultural identity continues to evolve. Our values and attitudes are no longer being shaped and defined by ourselves. Instead, the Jamaican cultural identity has become a cultural hybrid mirroring closely the happenings of those who now have control of the purse strings to which the Jamaican state needs access.

This can be seen in the proliferation of fast-food eateries on the Jamaican landscape. This has resulted in the Jamaican populace sharing some of the same issues associated with some of the issues our rich neighbours to the North now face. More and more Jamaicans are now overweight, obese even, as they turn to unhealthy processed and prepackaged foods instead of cooking a healthy meal.

In an age of globalisation and advances in technology, governments no longer have full control over what their population is fed. Social media, for example, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, have all added to the cultural penetration which has swept and continues to impact the Jamaican cultural landscape. Our young men, for the most part, now wear their pants below their waist exposing their undergarments. This once-alien cultural practice has taken hold especially of our young men. Tight-fitting clothing for males is another example of this cultural invasion. In a bygone era in Jamaica male clothing, especially pants, was loose fitting; however, the genie has been let out the box and, in some instances, there is blur of what constitutes male versus female clothing.

The cultural penetration sweeping Jamaica, and indeed the rest of the Caribbean, is so pervasive and powerful that in many instances international lending agencies are able to influence legislative laws in the parliament of sovereign states in exchange for providing funding for them to satisfy their balance of payment problems.

On the other hand, our closeness to North America has had and continues to have some positive spin-off on the Jamaican culture and life in general. Jamaica’s track and field programme has benefited tremendously over the years from our athletes competing against US athletes. Our athletes are now respected and in demand.

Another positive impact on the Jamaican culture comes in the form of economics. Remittances or foreign exchange inflows now account for approximately 15 per cent of Jamaica’s Gross Domestic Product. Thirdly, more and more Jamaicans are now doing their tertiary level studies in the United States. Upon their return home they oftentimes bring with them expertise and qualifications to help in nation-building.

The Jamaican culture has evolved into a world-class brand that is envied and admired globally. Our distinct dialect — patois — has been used repeatedly in US pop culture, mainly Hollywood movie and TV shows. In 2013 there was even a controversial Volkswagen advertisement which included Jamaican patois. This speaks volumes of the importance and acceptance that the global community attaches to the Jamaican culture and brand. It would be remiss if during the discourse we did not mention reggae. The history of reggae music lives right here in Jamaica. Reggae music is now known in almost every country on the planet due largely to the efforts of cultural icon Bob Marley.

We must and should strengthen our local institutions in an effort to counter this cultural invasion. We need to refocus more on our national symbols to reclaim and reaffirm our cultural identity. This can be done, in part, by exposing our students to the importance of retaining our culture as well as the significance of respecting our national symbols. Ensuring that civics becomes a compulsory subject at the secondary level of the education system would be one such way of maintaining our cultural integrity.

We may have different religions, different languages, different skin colour, but we all belong to one human race.

— Kofi Annan

Wayne Campbell is an educator and social commentator with an interest in development policies as they affect culture and/or gender issues. [email protected] www.wayaine.blogspot.com

ALSO ON JAMAICA OBSERVER

HOUSE RULES

- We welcome reader comments on the top stories of the day. Some comments may be republished on the website or in the newspaper; email addresses will not be published.

- Please understand that comments are moderated and it is not always possible to publish all that have been submitted. We will, however, try to publish comments that are representative of all received.

- We ask that comments are civil and free of libellous or hateful material. Also please stick to the topic under discussion.

- Please do not write in block capitals since this makes your comment hard to read.

- Please don't use the comments to advertise. However, our advertising department can be more than accommodating if emailed: [email protected] .

- If readers wish to report offensive comments, suggest a correction or share a story then please email: [email protected] .

- Lastly, read our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy

Recent Posts

- Privacy Policy

- Editorial Code of Conduct

We’re fighting to restore access to 500,000+ books in court this week. Join us!

Send me an email reminder

By submitting, you agree to receive donor-related emails from the Internet Archive. Your privacy is important to us. We do not sell or trade your information with anyone.

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Caribbean cultural identity : the case of Jamaica : an essay in cultural dynamics

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

Page 21 & 22 is physically missing.

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

161 Previews

7 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by Lotu Tii on December 11, 2013

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- Corpus ID: 132985690

Caribbean Cultural Identity: The Case of Jamaica

- R. Nettleford

- Published 1978

89 Citations

Cultural identity and the arts - new horizons for caribbean social sciences, freedom to “catch the spirit”: conceptualizing black church studies in a caribbean context, the evolution of the cultural policy regime in the anglophone caribbean, toward a cyclical theory of race relations in jamaica.

- Highly Influenced

Globalization and Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica: The Homogenization of Content and Americanization of Jamaican TV through Programme Modeling

Constructing “gaydren”: the transnational politics of same-sex desire in 1970s and 1980s jamaica, ‘race’ and inequality in postcolonial urban settings examples from peru, jamaica, and indonesia, a mailman to make government understand: the calypsonian (chalkdust) as political opposition in the caribbean, emancipating the nation (again): notes on nationalism, “modernization,” and other dilemmas in post‐colonial jamaica, cultural complexity, postcolonial perspectives, and educational change: challenges for comparative educators, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Cultural action and social change : the case of Jamaica; an essay in Caribbean cultural identity

Journal title, journal issn, volume title.

Monograph on the cultural heritage and the cultural factors of social change in the Caribbean, particularly in Jamaica - discusses the dilemma of cultural diversity and national unity, legacy of slavery and colonialism; cultural nationalism, preservation of traditional cultural values and art; cultural policy formulation, role of the arts and the mass media in national development; cultural integration and regional cooperation. Bibliographic notes.

Description

Item.page.type, item.page.format, collections.

THE CONSTRUCTION OF A JAMAICAN IDENTITY

During the period 1938 to 1962 there was a concerted effort on the part of middle class Jamaica to move away from the European cultural aesthetic and seek to develop a uniquely Jamaican cultural identity. In various cultural spheres, the African or Black aesthetic emerged from the background. In Art for instance, exhibitions began to feature native artist whose subject and style mirrored a local narrative. Traditional musical forms such as Kumina also began to make their way into mainstream society and influenced popular music such as Mento.

This development took place against a background of antagonistic relations amongst the racial groups. However, much of this occurred in private. Publicly there was an illusion of racial unity that was maintained for the “greater good of the country”.

In the creation of a new nation, the architects of Jamaica’s Independence wisely sought to maintain the perceived outward expression of racial unity. This was the understanding that went into the coining of the Jamaican motto “Out of many, one people”.

Extracted from, Independence: What it Means to Us,United Printers Ltd,: Marcus Garvey Drive, Kingston

Enjoyed the exhibition? Share the link with a friend

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Globalisation and Cultural Identity in Caribbean Society: The Jamaican Case

Related Papers

American Ethnologist

Don Robotham

Acta Hispanica

In examining Caribbean identity, it is essential to examine the demarcation of the area, delimit the boundaries, assess how local people have defined or redefined themselves in space and time, and how this is influenced by economics and politics. Obviously the key is the geographic proximity of the Caribbean Sea and its history, which result in many similarities in time, but there is variation, and there are differences. Two significant researchers who investigated the most important common elements like colonization, plantation economy and slavery, Charles Wagley and Sidney Mintz cultural anthropologists, conducted their fieldwork in Brazil, Puerto Rico, Haiti and Jamaica. In defining the “Caribbean” within Plantation America cultural sphere, Charles Wagley took into account the geography, the environment, linguistics, the modes of production, the local histories. Both anthropologists made sociocultural, ethnographic and demographic analyses, comparing the colonial structures in th...

Charles Carnegie

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences

Cristina-Georgiana Voicu

Suzanne Burke

This paper addresses the complexities involved in developing cultural policies in the Anglophone Caribbean. The first section examines the evolution of the cultural policy agenda in the 40-odd years since the independence era. It traces and analyses the policy trajectory from one that sought to promote the intrinsic values of culture, to one that currently espouses the more instrumental value of the cultural industries. The next section analyses the efficacy of the policy path by examining a regional cultural policy initiative, the Caribbean Festival for the Arts (CARIFESTA). The paper suggests that the Caribbean cultural policies have under performed because of critical disjunctures. These generally involve the imposition of a nationalistic policy framework on the transnational structure of the Caribbean cultural sector. The paper concludes by suggesting a regional cultural approach to policy formulation can provide a more effective mechanism to encourage and harness the cultural wealth of the Anglophone Caribbean. The Anglophone Caribbean 1 is perhaps best known for its dynamic cultural expressions , and the wealth of its cultural assets and resources. From the musical stylings of reggae icon Bob Marley, to the poetic musings of Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott, and the splendor of Trinidad and Tobago's overseas Carnival complex, the cultural products of the Caribbean have secured a place in the global cultural marketplace. In the 40-odd years since the region's independence from Britain, many aspects of Caribbean culture are clearly discernible in global entertainment products including music, film and video, and the visual arts. However, these accomplishments have occurred in large part, without the sustained benefit of local and regional cultural policy support. Notwithstanding the ongoing pronouncements of successive political regimes regarding the central role of culture, and more specifically, of cultural policies in the overall development of the region, the Anglo-phone Caribbean has acquired a poor record of cultural policy activation. With the possible exception of Jamaica, and more latterly Barbados and St Lucia, few countries in the region have developed clearly articulated policy positions. 2 What has emerged in the post independence period is a set of practices, programmes, and texts that are philosophically grounded in a nationalist framework, and activated through the Ministries of Culture and other public sector agencies. This approach to cultural policy development has yielded

Leah Broome

Caribbean Quartely

Oscar Webber

Anthurium A Caribbean Studies Journal

Carole Boyce-Davies

Anton Allahar

Claudia Rauhut

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

Culture Name

Orientation.

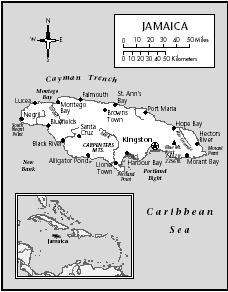

Identification. In 1494, Columbus named the island Santiago. The Spanish wrote the name used by the native Taino, "Yamaye," as "Xaymaca." The Taino word is purported to mean "many springs." The abbreviated name, "Ja" and the Rastafarian term "Jamdung" (Jamdown) are used by some residents, along with "Yaahd" (Yard), used mainly by Jamaicans abroad, in reference to the deterritorialization of the national culture.

Location and Geography. Jamaica, one of the Greater Antilles, is situated south of Cuba. Divided into fourteen parishes, it is 4,244 square miles (10,990 square kilometers) in area. In 1872, Kingston, with a quarter of the population, became the capital.

Demography. The population in 1998 was 2.75 million. Fifty-three percent of the population resides in urban areas. The population is 90 percent black, 1 percent East Indian, and 7 percent mixed, with a few whites and Chinese. The black demographic category includes the descendants of African slaves, postslavery indentured laborers, and people of mixed ancestry. The East Indians and Chinese arrived as indentured laborers.

Linguistic Affiliation. The official language is English, reflecting the British colonial heritage, but even in official contexts a number of creole dialects that reflect class, place, and social context are spoken.

Symbolism. The national motto, which was adopted after independence from Great Britain in 1962, is "Out of many, one people." In the national flag, the two black triangles represent historical struggles and hardship, green triangles represent agricultural wealth and hope, and yellow cross-stripes represent sunshine and mineral resources.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Jamaica was a Spanish colony from 1494 to 1655 and a British colony from 1655 to 1962. The colonial period was marked by conflict between white absentee owners and local managers and merchants and African slave laborers. After independence, there was conflict between plantation and industrial economic interests and those of small, peasant cultivators and landless laborers. In the 1920s, rural, landless unemployed persons moved into the Kingston-Saint Andrew area in search of work. The new urban poor, in contrast to the white and brown-skinned political, merchant, and professional upper classes threw in sharp relief the status of the island as a plural society. In 1944, with the granting of a new constitution, Jamaicans gained universal suffrage. The struggle for sovereignty culminated with the gaining of independence on 6 August 1962.

National Identity. Class, color, and ethnicity are factors in the national identity. Jamaican Creole, or Jamaica Talk, is a multiethnic, multiclass indigenous creation and serves as a symbol of defiance of European cultural authority. Identity also is defined by a religious tradition in which there is minimal separation between the sacred and the secular, manipulable spiritual forces (as in obeah ), and ritual dance and drumming; an equalitarian spirit; an emphasis on self-reliance; and a drive to succeed economically that has perpetuated Eurocentric cultural ideals.

Ethnic Relations. The indigenous Taino natives of the region, also referred to as Arawaks, have left evidence of material and ideational cultural influence. Jews came as indentured servants to help establish the sugar industry and gradually became part of the merchant class. East Indians and Chinese were recruited between the 1850s and the 1880s to fill the labor gap left by ex-slaves and to keep plantation wages low. As soon as the Chinese finished their indentured contracts, they established small businesses. East Indians have been moving gradually from agricultural labor into mercantile and professional activities.

The major ethnic division is that between whites and blacks. The achievement of black majority rule has led to an emphasis on class relations, shades of skin color, and cultural prejudices, rather than on racial divisions. Jamaica has never experienced entrenched ethnic conflict between blacks and Indians or Chinese.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Settlement patterns were initiated by plantation activities. Lowland plantations, complemented by urban trade and administrative centers, ports, and domestic markets, were the hub of activity. As the plantations declined and as the population grew, urban centers grew faster than did job opportunities, leading to an expanding slum population and the growth of urban trading and other forms of "informal" economic activities.

Architecture reflects a synthesis of African, Spanish, and baroque British influences. Traces of pre-Columbian can be seen in the use of palm fronds thatch and mud walls (daub). Styles, materials, size, and furnishings differ more by class than by ethnicity. Since much of Caribbean life takes place outdoors, this has influenced the design and size of buildings, particularly among the rural poor. The Spanish style is reflected in the use of balconies, wrought iron, plaster and brick facades, arched windows and doors, and high ceilings. British influence, with wooden jalousies, wide porches, and patterned railings and fretwork, dominated urban architecture in the colonial period. Plantation houses were built with stone and wood, and town houses typically were built with wood, often on a stone or cement foundation. The kitchen, washroom, and "servant" quarters were located separately or at the back of the main building. The traditional black peasant dwelling is a two-room rectangular structure with a pitched thatched roof and walls of braided twigs covered with whitewashed mud or crude wooden planks. These dwellings are starting to disappear, as they are being replaced by more modern dwellings with cinder block walls and a corrugated metal roof.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. A "country" morning meal, called "drinking tea," includes boiled bananas or roasted breadfruit, sauteed callaloo with "saal fish" (salted cod), and "bush" (herbal) or "chaklit" (chocolate) tea. Afro-Jamaicans eat a midafternoon lunch as the main meal of the day. This is followed by a light meal of bread, fried plantains, or fried dumplings and a hot drink early in the evening. A more rigid work schedule has forced changes, and now the main meal is taken in the evening. This meal may consist of stewed or roasted beef, boiled yam or plantains, rice and peas, or rice with escoviched or fried fish.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Rice is a ubiquitous ceremonial food. Along with "ground provisions" such as sweet potato, yam, and green plantains, it is used in African and East Indian ceremonies. It also is served with curried goat meat as the main food at parties, dances, weddings, and funerals. Sacrificially slaughtered animals and birds are eaten in a ritual context. Several African-religious sects use goats for sacrifice, and in Kumina, an Afro-religious practice, goat blood is mixed with rum and drunk.

Basic Economy. Since the 1960s, the economy, which previously had been based on large-scale agricultural exportation, has seen considerable diversification. Mining, manufacturing, and services are now major economic sectors.

Land Tenure and Property. Land tenure can be classified into legal, extralegal, and cultural-institutional. The legal forms consist of freehold tenure, leasehold and quitrent, and grants. The main extralegal means of tenure is squatting. The cultural-institutional form of tenure is traditionally known as "family land," in which family members share use rights in the land.

Commercial Activities. The economy is based primarily on manufacturing and services. In the service economy, tourism is the largest contributor of foreign exchange. The peasantry plays a significant role in the national economy by producing root crops and fruits and vegetables.

Trade. The main international trading partners are the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the Caribbean Economic Community. The major imports are consumer goods, construction hardware, electrical and telecommunication equipment, food, fuel, machinery, and transportation equipment. The major exports are bauxite and alumina, apparel, sugar, bananas, coffee, citrus and citrus products, rum, cocoa, and labor.

Division of Labor. In the plantation economy, African slaves performed manual labor while whites owned the means of production and performed managerial tasks. As mulattos gained education and privileges, they began to occupy middle-level positions. This pattern is undergoing significant change, with increased socioeconomic integration, the reduction of the white population by emigration, and the opening of educational opportunities. Blacks now work in all types of jobs, including the highest political and professional positions; the Chinese work largely in retail and wholesale trades; and Indians are moving rapidly into professional and commercial activities. Women traditionally are associated with domestic, secretarial, clerical, teaching, and small-scale trading activities.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. The bulk of national wealth is owned by a small number of light-skinned or white families, with a significant portion controlled by individuals of Chinese and Middle Eastern heritage. Blacks are confined largely to small and medium-size retail enterprises. While race has played a defining role in social stratification, it has not assumed a caste-like form, and individuals are judged on a continuum of color and physical features.

Symbols of Social Stratification. Black skin is still associated with being "uncivilized," "ignorant," "lazy," and "untrustworthy." Lifestyle, language, cuisine, clothing, and residential patterns that reflect closeness to European culture have been ranked toward the top of the social hierarchy, and symbols depicting African-derived culture have been ranked at the bottom. African symbols are starting to move up in the ranks, however.

Political Life

Government. Jamaica, a member of the British Commonwealth, has a bicameral parliamentary legislative system. The executive branch consists of the British monarch, the governor general, the prime minister and deputy prime minister, and the cabinet. The legislative branch consists of the Senate and the sixty-member elected House of Representatives. The judicial branch consists of the supreme court and several layers of lower courts.

Leadership and Political Officials. The two major parties are the People's National Party (PNP) and the Jamaica Labor Party (JLP). Organized pressure groups include trade unions, the Rastafarians, and civic organizations.

Social Problems and Control. The failure of the socialist experiment in the 1970s and the emphasis on exports have created a burgeoning mass of urban poor (scufflers) who earn a meager living in the informal, largely small-scale trading sector and engage in extralegal means of survival. Also, globalization has led to the growth of the international drug trade. The most serious problem is violent crime, with a high murder rate. Governmental mechanisms for dealing with crime-related social problems fall under the Ministry of National Security and are administered through the Criminal Justice System.

Military Activity. The military consists of the Jamaica Defense Force (which includes the Ground Forces, the Coast Guard, and the Air Wing) and the Jamaica Constabulary Force. Both branches include males and females. The military is deployed mainly for national defense and security purposes but occasionally aids in international crises.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

The social development system combines local governmental programs and policies, international governmental support, and local and international nongovernmental organization (NGO) participation. It is administered largely by the Ministry of Youth and Community Development. The social security and welfare system includes the National Insurance Scheme (NIS) and public assistance programs. NIS benefits include employment benefits; old age benefits; widow and widower, orphan, and special child benefits; and funeral grants.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Over 150 NGOs are active in areas such as environmental protection, the export-import trade, socioeconomic development, and education.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Men are predominant in leadership positions in government, the professions, business, higher education, and European-derived religions and engage in physical labor in agriculture. Women work primarily in paid and unpaid in household labor, formal and informal retail trades, basic and primary education, clerical and administrative jobs, and social welfare.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Traditionally, woman's place is in the home and women receive less remuneration than men. The appropriate place for men is outside the home, in agriculture, business, government, or recreation. This attitude is changing.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Domestic Unit. The domestic unit typically consists of a grandmother, a mother, and the mother's offspring from the current and previous unions. The father may be a permanent part of the unit, may visit for varying periods, or may be absent. Often the unit includes children of kin who are part of other households.

Inheritance. Inheritance generally passes bilaterally from parents to children and grandchildren. Among the poor, land that is inherited helps to maintain strong family and locality relationships.

Kin Groups. The concept of family applies to blood and nonblood kin who maintain an active, functional relationship with respect to material and social support. It is not limited to the household. Family relations are of great importance, and children of the poor often are shifted from household to household for support. Kin relations are traced bilaterally for four or five generations.

Socialization

Infant Care. The use of midwives is still popular, and breast-feeding is done in all the ethnic groups. A baby is named and registered within a few days of its birth, and soon afterward it is "christened." Infants typically sleep with the mother and are carried in her arms. A crying baby is rocked in the mothers arms and hummed to. As a baby ages, the parents and grandparents try to accommodate their expectations to the child's unique qualities; the baby is allowed to "grow into itself."

Child Rearing and Education. Firm discipline underlies child care until a child leaves home and/or becomes a parent. The mother is central, but all members of the household and other close kin have some responsibility in rearing a child. It is believed that the behavior of the pregnant mother influences what the child will become. Children are said to "take after" a parent or to be influenced by "the devil" or the spirits of ancestors. Children are given progressively demanding responsibilities from the age of five or six. For poor parents in all ethnic groups, the single most important route out of poverty is the education of their children. In more traditional settings, the child is "pushed" by the entire family and even the community. The national stereotype is that Indians and Chinese pay greater attention to their offspring, who perform better than blacks.

Higher Education. Higher education is considered essential to national success, and the parliament has established the National Council on Education to oversee higher education policy and implementation. Expenditures on education have continued to rise. There are two universities the University of the West Indies, and the University of Technology.

Politeness and courtesy are highly valued as aspects of being "raised good." They are expressed through greetings, especially from the young to their elders. A child never "backtalks" to parents or elders. Men are expected to open doors for women and help with or perform heavy tasks. Women are expected to "serve" men in domestic contexts and, in more traditional settings, to give the adult males and guests the best part of a meal.

Religious Beliefs. The Anglican church is regarded as the church of the elite, but the middle class in all ethnic groups is distributed over several non-African-derived religions. All the established denominations have been creolized; African-Caribbean religious practices such as Puk-kumina, revivalism, Kumina, Myalism, and Rastafarianism have especially significant African influences.

Religious Practitioners. Among less modernized African Jamaicans, there is no separation between the secular and the sacred. Afro-Jamaican leaders are typically charismatic men and women who are said to have special "gifts" or to be "called."

Rituals and Holy Places. Rituals include "preaching" meetings as well as special healing rituals and ceremonies such as "thanksgiving," ancestral veneration, and memorial ceremonies. These ceremonies may include drumming, singing, dancing, and spirit possession. All places where organized rituals take place are regarded as holy, including churches, "balm yards," silk cotton trees, burial grounds, baptismal sites at rivers, and crossroads.

Medicine and Health Care

Jamaicans use a mix of traditional and biomedical healing practices. The degree of use of traditional means, including spiritual healing, is inversely related to class status. Among the African Jamaicans, illness is believed to be caused by spiritual forces or violation of cultural taboos. Consequently, most illnesses are treated holistically. When traditional means fail, modern medicine is tried.

Secular Celebrations

Independence Day is celebrated on the first Monday in August. Other noteworthy holidays are Christmas, Boxing Day, New Year's Day, and National Heroes Day, which is celebrated the third Monday in October. Chinese New Year is celebrated.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. The arts and humanities have a long tradition of development and public support, but state support has been institutionalized only since independence. Most artists are self-supporting.

Literature. Indians, Chinese, Jews, and Europeans brought aspects of their written tradition, yet current literary works are overwhelmingly African Jamaican. The oral tradition draws on several West African-derived sources, including the griot tradition; the trickster story form; the use of proverbs, aphorisms, riddles, and humor in the form of the "big lie"; and origin stories. The 1940s saw the birth of a movement toward the creation of a "yard" (Creole) literature.

Graphic Arts. The tradition of graphic arts began with indigenous Taino sculpting and pottery and has continued with the evolution of the African tradition. Jamaica has a long tradition of pottery, including items used in everyday domestic life, which are referred to as yabbah. There is a West African tradition of basket and straw mat weaving, seashell art, bead making, embroidery, sewing, and wood carving.

Performance Arts. Most folk performances are rooted in festivals, religious and healing rituals, and other African-derived cultural expressions. Traditional performances take the form of impromptu plays and involve social commentary based on the African Caribbean oratorical tradition ("speechifying" or "sweet talking"). Music is the most highly developed of the performing arts. There is a long tradition of classical music interest, but the country is best known for its internationally popular musical form, reggae. Jamaica also has a strong tradition of folk and religious music. Drama is the least developed performing art, but it has been experiencing a new surge of energy.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

There are physical and social science programs at the University of West Indies (UWI) and the Institute of Jamaica and its ancillary research bodies such as the African Caribbean Institute of Jamaica. The UWI has a medical school and a law school, and there is a University of Technology. Most social science research is done with support from the Institute of Social and Economic Research.

Bibliography

Alleyne, Mervyn. The Roots of Jamaican Culture , 1989.

Carnegie, Charles V., ed. Afro-Caribbean Villages in Historical Perspective , 1987.

Cassidy, Frederic. Jamaica Talk: Three Hundred Years of the English Language in Jamaica , 1971.

Chevannes, Barry. Rastafari: Roots and Ideology , 1994.

Curtin, Philip D. Two Jamaicas: The Role of Ideas in a Tropical Colony, 1830–1865, 1955.

Dance, Daryl C. Folklore from Contemporary Jamaicans , 1985.

Kerr, Madeline. Personality and Conflict in Jamaica , 1963.

Mintz, Sidney W. Caribbean Transformations , 1974.

Nettleford, Rex. Caribbean Cultural Identity: The Case of Jamaica , 1979.

Olwig, Karen Fog. "Caribbean Family Land: A Modern Commons." Plantation Society in the Americas , 4 (2 and 3): 135–158, 1997.

Rouse, Irving. The Tainos: Rise and Decline of the People Who Greeted Columbus , 1992.

Senior, Olive. A–Z of Jamaica Heritage , 1985.

Sherlock, Philip, and Hazel Bennett. The Story of the Jamaican People , 1998.

Smith, Michael G. The Plural Society in the British West Indies , 1974.

—T REVOR W. P URCELL

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

- Mobile Apps

- Subscribe Now

Secondary Menu

- Art & Leisure

- Classifieds

Rebuilding Jamaica’s cultural identity

Fostering deeper connection with built environment.

In the heart of the Caribbean lies a nation rich with history, tradition, and a vibrant cultural identity: Jamaica. However, as modernisation surges forward, a concerning trend is emerging: a growing disregard and disconnect between Jamaican citizens and their built environments. This neglect not only threatens the physical aesthetics of the country, but also risks severing the ties that bind its people to their heritage.

I would like to initiate an open conversation where we delve into the pressing need to bridge the gap between cultural identity, tradition, and preservation within Jamaica’s built environment, fostering a harmonious relationship that celebrates our past while embracing our future.

Jamaica’s built environment holds a trove of stories, memories, and legacies that are intertwined with its people’s lives. This synergy is not merely a matter of architecture, but rather, a manifestation of culture, craftsmanship, and tradition. Our architectural heritage speaks volumes about our history, values, and aspirations. Yet with each passing day, we witness the rise of structures that mimic Western ideals, subtly eroding the distinctive Jamaican identity that should be etched into our buildings.

Cultural identity is the soul of a nation, and architecture serves as its tangible expression. A well-preserved built environment is a testament to our roots and achievements. The fusion of colonial, African, and indigenous influences in Jamaican architecture paints a vivid picture of our complex history. From the intricate wooden fretwork to the vernacular constructs that nestle the experiences of freedom and resourcefulness of our rural areas, every inch tells a story. By nurturing, and developing these architectural elements, we establish a living connection between past and present, reminding us all of our shared heritage.

CASTS A SHADOW

Additionally, it is important to acknowledge the negative historical context that sometimes casts a shadow over discussions of craftsmanship and cultural identity. The echoes of slavery and colonialism have, undeniably, left scars on our history. However, focusing solely on the pain and suffering can eclipse the brilliance of our cultural achievements and the resilience of our people. By choosing to highlight the craftsmanship and artistry that existed long before and after those dark times, we can shift the narrative towards empowerment and self-expression.

Headlines Delivered to Your Inbox

Craftsmanship is a cornerstone of tradition, and it finds its truest expression in architecture. The meticulous techniques passed down through generations are a testament to our commitment to excellence. This craftsmanship not only provides aesthetic appeal, but also serves as a tangible link to our ancestors’ skills and dedication. From the artistic detailing of our churches and mahogany furniture to the vibrant motifs adorning our homes, every stroke of craftsmanship is a celebration of our past and a foundation for our future.

However, the present trend seems to lean towards disconnect rather than continuity. Cookie-cutter designs, often imported from the West, are becoming increasingly prevalent. These structures may be functional, but they lack the heart and soul that come with embracing our cultural identity. By continuing down this path, we risk exchanging our vibrant tapestry for a monotone canvas, devoid of the essence that makes Jamaica unique.

ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIP

To counter this alarming trajectory, we must create a romantic relationship between citizens and their built environment. This romance is not about mere aesthetics, but about fostering a deep emotional connection that resonates with our shared heritage.

Imagine walking through streets adorned with buildings that tell stories through their design, materials, and details. These structures would evoke a sense of belonging, pride, and nostalgia, enabling us to navigate our fast-paced world while firmly rooted in our history.

Visualising this transformative concept is vital, and it starts with rendering a future where our culture and traditions flourish. In my architectural renders, I prompt and envision spaces that embody craft, history, and storytelling. From the ornamental mechanisms of the one-stop bus stop to the organised chaos in the timber structures of the blinkin bus station. All these renditions explore and depict moments within our history that are known and unknown, visible, and hidden.

In conclusion, the disconnect Jamaican citizens are experiencing with their built environment is a call to action for rekindling our relationship with our cultural identity and architectural heritage. By romanticising the craftsmanship, culture, and tradition that underpin our built spaces, we can forge a deeper connection that empowers citizens to actively engage in the preservation and evolution of these spaces. Through renderings that inspire and captivate, we can envision a future where our built environment celebrates our uniqueness and paves the way for a harmonious coexistence of tradition and progress. It is time to rewrite the story of our architecture, one that is rich in culture, pride, and a shared sense of belonging.

- An Ode to Jamaica »

View the discussion thread.

‘Jamaica to the world’

A small town on a small island celebrates kamala harris’ meteoric rise.

By Fredreka Schouten, Zoë Todd, Curt Merrill and Byron Manley, CNN

Published August 17, 2024

BROWN’S TOWN, Jamaica — Three and a half years ago, Sherman Harris gathered together a clutch of family and friends at his home on a hilltop here in rural Jamaica to watch his cousin step into history.

As Kamala Harris took the oath of office as vice president of the United States, the room erupted in screams and tears, he recalled.

“Even talking to you now, I feel some sort of tears from my eyes too, you know,” Sherman Harris, 59, said in an interview with CNN. “It's like tears of joy.”

Next week, they will gather again before his widescreen television to watch Harris make history once more, when she formally accepts the Democratic presidential nomination — becoming the first Black woman, the first Jamaican American and the first Asian American to become a major party’s White House standard-bearer.

Although the milestone will be celebrated by her relatives in this town of some 12,000 people on the island’s northern coast, Harris’ Caribbean roots still are coming into focus for the millions of Americans getting acquainted with her after she was suddenly thrust to the top of the Democratic ticket a month ago when President Joe Biden ended his reelection bid and endorsed his vice president.

Already, her Republican rival, Donald Trump, has sought to question her Black identity as the two vie for support among African American voters in states such as Michigan and Georgia who could determine the outcome of this fall’s race. At a gathering of Black journalists last month, Trump falsely claimed that Harris had only recently opted to identify as Black out of political opportunism.

“I don’t know, is she Indian or is she Black?” Trump asked in widely derided comments.

Harris is both. She’s the daughter of an Indian-born mother, Shyamala Gopalan, a breast cancer researcher who died in 2009, and a Jamaican-born father, Donald Harris, an 85-year-old retired Stanford University economist, who has largely remained in the background of his daughter’s public life.

He hails from a family that stretches back for generations in Brown’s Town, a market town in St. Ann Parish, where vendors clustered along the main drag on a recent Sunday morning to sell glossy green avocados, yams and bundles of fragrant thyme.

It's a place Kamala Harris knows from childhood visits and readily claims.

“Half of my family is from St. Ann Parish in Jamaica,” she told the country’s prime minister, Andrew Holness, during a 2022 visit to the White House. “I know I share that history with millions of Americans.”

And it’s a town that proudly claims her.

“You have to recognize individuals who come from humble abodes and really excel,” said Michael Belnavis, the mayor of St. Ann Parish who is mulling ways to honor Harris should she prevail in November. “Coming from Brown’s Town is as humble as it gets.”

Deep roots and a powerful matriarch

The town was named after Hamilton Brown, a slave owner who came to the island from Ireland and, according to family lore, is believed to have been an ancestor of Kamala Harris’ great-grandmother, Christiana Brown, also a descendant of enslaved Jamaicans.

“Miss Chrishy,” as Christiana Brown was known, helped raise her grandson, Donald Harris, who described her in an essay first published in 2018 in the Jamaica Global Online as “reserved and stern in look, firm with ‘the strap’ but capable of the most endearing and genuine acts of love, affection, and care.”

Harris has said his interest in economics and politics was sparked, in part, by observing Miss Chrishy as she went about her daily routine of operating her dry goods store in Brown’s Town.

Although she died in 1951, Miss Chrishy looms large to this day among her descendants, who still talk of her elegant dresses, proper manners and the high standards she set for her children and grandchildren.

“She was the backbone,” said Latoya Harris-Ghartey, Sherman Harris’ 43-year-old daughter. Harris-Ghartey is executive director of Jamaica’s National Education Trust, a government-aligned organization focused on developing the island’s education infrastructure.

Her great-grandmother “believed in getting your books and having a solid education, those sorts of things,” Harris-Ghartey said. “I think that has passed on throughout the line. Everybody always pushes you to be better, to excel.”

Miss Chrishy had several children with Joseph Harris, who raised cattle and grew pimento berries — allspice in its dried form — on a farm perched high above Brown’s Town. He died in 1939, a year after Donald Harris was born, and is buried on the grounds of St. Mark’s Anglican Church — a sanctuary founded by Hamilton Brown and where Harrises have long worshipped.

Brown’s Town might be a small place, but the family has occupied a prominent position there as landowners and businesspeople.

Today, Sherman Harris — Donald Harris’ first cousin — still lives on and works the Harris land, in an area known as Orange Hill for a citrus grove that once stood there, he said. One of its dominant features is the Harris Quarry, started by Sherman Harris’ late father, Newton. Sherman runs it now, and it still produces crushed limestone and bricks.

It’s one of his ventures. On a tour with CNN journalists, he proudly pointed out the three-story commercial building he owns in the heart of Brown’s Town.

It’s to this landscape that Donald Harris would bring Kamala and her younger sister, Maya, on holidays, according to his 2018 essay — taking them through the town’s bustling marketplace, touring his primary school and other landmarks he found meaningful. He recounted the trio trekking through the cow pastures and overgrown paths on Orange Hill during one memorable visit in 1970, as they retraced his boyhood ramblings over the family property.

“Upon reaching the top of a little hill that opened much of that terrain to our full view, Kamala, ever the adventurous and assertive one, suddenly broke from the pack, leaving behind Maya the more cautious one, and took off like a gazelle in Serengeti, leaping over rocks and shrubs and fallen branches, in utter joy and unleashed curiosity, to explore that same enticing terrain,” he wrote. “I couldn’t help thinking there and then: What a moment of exciting rediscovery being handed over from one generation to another!”

Sherman Harris remembers all the cousins playing together during those jaunts to Jamaica in the 1970s, while the adults feasted and socialized. He and Kamala are the same age, born just days apart in October 1964.

What stands out most from those memories, he said, is how smart the girls were – just like their dad, who rose from a rural boyhood to earn a doctorate from the University of California, Berkeley and become the first Black economics professor granted tenure at Stanford .

“Brilliant girls,” Sherman Harris said of Kamala and Maya. Even as young children, they would quiz him on the island’s current affairs, and “I wasn’t able to answer them,” he recalled. “I had to ask Daddy.”

Sherman Harris views his cousin’s ascension as yet another example of “Jamaica to the world,” a reference to the island’s culture, reggae music and food catching fire across the globe. It’s also a sign to him of the Harris drive.

“We have never ventured in much failure, you know,” he said of the Harris clan, adding that the family members are “always successful in whatever we do.”

Out of the spotlight

Even as his daughter climbs to new heights, Donald Harris has remained largely out of the spotlight.

He and Shyamala Gopalan, who met in the 1960s as graduate students at Berkeley, fell in love fighting for civil rights, Kamala Harris wrote of her parents in her 2019 memoir, “The Truths We Hold: An American Journey.” But by the time she was 5, “they had stopped being kind to one another” and soon separated.

They divorced a few years later, and Gopalan became the parent who had the greatest influence in shaping her daughters’ lives, raising them, Kamala Harris wrote, to be “confident, proud black women” in a country that would see them, first and foremost, as African American. Kamala Harris would go on to attend one of the country’s most storied Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Howard University in Washington, DC, and pledge as an Alpha Kappa Alpha while there, joining the nation’s oldest Black sorority.

In her book, Harris “goes on for page after page about her mom,” said veteran California political reporter Dan Morain, who wrote a 2021 biography, “Kamala’s Way: An American Life,” that charted the Democrat’s rise through Golden State and national politics. “She’s really important in her life, and I believe her mother is still with her on a daily basis,” years after her death, he said.

“But she passes over her father,” Morain said.

Harris wrote that her father “remained a part of our lives” after the divorce, spending time with them on weekends and in the summer.

The senior Harris complained that his relationship with his daughters was subject to “arbitrary limits” after a contentious custody fight. The state of California, he wrote bitterly in the essay, operated on the “false assumption … that fathers cannot handle parenting (especially in the case of this father, ‘a neegroe from da eyelans’ was the Yankee stereotype, who might just end up eating his children for breakfast!)”

“Nevertheless, I persisted, never giving up on my love for my children or reneging on my responsibilities as their father,” he added.

Donald Harris did not respond to several interview requests from CNN and largely has shied away from publicity — even as his daughter stands on the cusp of another history-making milestone in his adopted country.

He did emerge publicly during Harris’ 2020 bid for the Democratic presidential nomination to publicly chastise her for joking that of course she had smoked marijuana , given her Jamaican background.

In a since-deleted statement posted on Jamaica Global Online, Donald Harris said his ancestors were “turning in their grave” to see their “family’s name, reputation and proud Jamaican identity” connected with a “fraudulent stereotype of a pot-smoking joy seeker.”

Damien King, a retired economics professor at the University of the West Indies in Jamaica who now runs a think tank on the island, first met the elder Harris in the mid-1980s and said he was not surprised by the public rebuke. “He is somebody who has always been unafraid to speak his mind,” King said.

And among the economists who know him, Harris is considered a free thinker, willing to challenge his field’s “orthodoxy,” King added.

Former Harris student Steven Fazzari, an economist who teaches at Washington University in St. Louis, described his former professor as someone who thinks “deeply about economic theory.”

“He’s not the kind of economist who’s going to talk to you about what the GDP is going to be and what inflation is going to be in the next quarter,” he said.

Harris, who served at Fazzari’s doctoral thesis adviser at Stanford, encouraged originality and was a friendly and supportive figure to his students, Fazzari added.

Fazzari had not seen Harris for years, until he and several other former students arranged a dinner with him last fall in Washington, where Harris maintains a residence.

“It was wonderful,” he said of the dinner. “Don Harris in his mid-80s is just like the Don Harris I knew at Stanford. He was articulate. He was gracious. He remembered all of us. He remembered all of our dissertation topics.”

‘That’s my cousin running’

Kamala Harris’ ancestry has already been thrust into the center of the presidential campaign, as Trump grapples with how to confront her last-minute candidacy and reaches for a strategy to blunt her momentum.

During a combative interview at the National Association of Black Journalists’ convention late last month, Trump went personal — falsely claiming that Harris had opted to “turn Black.” He later inexplicably called her “Kamabla” in series of posts on his Truth Social site.

Trump’s running mate, Ohio Sen. JD Vance, meanwhile, has questioned her authenticity — calling her a “phony” who “grew up in Canada,” a reference to the years she spent living in Montreal, where her mother had taken a teaching position at McGill University.

The mischaracterization of Harris’ racial identity “plays into these tropes of the tragic mulatto who’s doomed and sneaky and deceptive” and belongs nowhere, said Danielle Casarez Lemi, who studies race and ethnic politics as a Tower Center fellow at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. She’s also the co-author, alongside Nadia Brown, of “Sister Style: The Politics of Appearance for Black Women Political Elites.”

“It’s a way to try to damage her credibility anyway that he can,” she said of Trump. “Whether it’s going to work, who knows?”

Dahlia Walker-Huntington, a Jamaican American lawyer and longtime Harris supporter, called Trump’s comments challenging the vice president’s racial identity “condescending.”

“It is also ignorant to think that we can only have one identity” in a society that is increasingly multiracial and multicultural, said Walker-Huntington, who divides her time between South Florida and Kingston. “The America of 2024 is the America that Kamala Harris represents.”

Walker-Huntington said she has followed Harris’ career for years, going back to her time as a local prosecutor and California attorney general. She first met Harris at a Florida fundraiser in 2018 for Florida Sen. Bill Nelson’s campaign and would go on to become an enthusiastic backer of Harris’ short-lived presidential bid.

Now, along with other Caribbean American supporters, Walker-Huntington is activating networks of friends, relatives and acquaintances in the hopes of getting Harris over the top this time.

“I support her because she’s a strong woman, and she stands up for her convictions,” Walker-Huntington said. “The fact that she’s Jamaican, that’s icing on the cake. It makes me feel like that’s my cousin running for the presidency of the United States.”

CNN has reached out to the Harris campaign.

Those who know her say she celebrates her ties to the island to this day. On the eve of her swearing-in as vice president, Harris told The Washington Post that her father instilled in her and her sister a deep pride in Jamaica and its history. Walker-Huntington and Winston Barnes — an elected official in Miramar, Florida, who also hails from Jamaica — said she was quick to banter with a group of them in a Jamaican accent when they first met her at the Nelson event a few years ago.

The vice president’s cousin, Sherman Harris, said he has not seen her for years, but Donald Harris still visits with the family.

Jamaica has formally recognized Donald Harris, bestowing on him an Order of Merit in 2021 for “outstanding contribution to National Development.” Over the years, he has served as an economic adviser to the Jamaican government and helped craft a 2012 strategy to encourage economic growth on the island.

Back in Brown’s Town, there’s been talk of adding Kamala Harris’ visage to the mural of prominent Jamaicans that encircles the grounds of St. Mark’s, her cousin said. It currently includes figures such as sprinter Usain Bolt and Black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey, who was born in the parish.

But Belnavis, the mayor of St. Ann, said he is thinking bigger — a statue, perhaps, in or near a municipal building if Harris wins the US presidency.

“The murals that you see on the walls eventually will wear away and so on,” he said. “We want something more permanent.”

Liberation through Rhythm: BU Ethnomusicologist Studies History and Present of African Beats

BU ethnomusicologist Michael Birenbaum Quintero studies African beats and their impacts in Colombia, Cuba, and the US

Michael Birenbaum Quintero explores how African rhythms have influenced the cultures in Colombia, Cuba, and the US

Jake belcher.

Michael Birenbaum Quintero is Colombian American, but as a young man growing up in the States, he had little connection to his South American heritage. His way back into it was studying Colombia’s music.

“It was a way to find out things that I wanted to know about myself. And then I started finding out more about Colombia at large,” he says. “It’s a very fascinating, complex, tragic, beautiful, overwhelming place.”

An expert on how music intertwines with culture, Birenbaum Quintero is a Boston University College of Fine Arts associate professor of music and chair of musicology and ethnomusicology. His office at 808 Comm Ave is crowded both with the books and papers accruing from an academic career and the instruments of someone with a serious percussion habit, including an array of hand drums and shakers—and not one, but two marimbas.

His mother was Jewish and from the Bronx and his father had grown up outside Cali, Colombia. He was young when his parents split up and his father was deported back to Colombia, where he died. Growing up in New York City and New Jersey, Birenbaum Quintero missed a relationship with his father’s side of his heritage.

Music was a big part of his life from early on. He played guitar in high school, but switched to a tres, a Cuban guitar, and later to percussion when he started playing with salsa bands as an undergraduate in New York. “All of that music is built off interacting with [rhythm] patterns. And so I found myself exploring the percussion more and more,” he says.

Birenbaum Quintero was teaching ESL in New York City for a living when a chance encounter with an ethnomusicologist—a person who studies music in cultural contexts, including religion, politics, and the environment—started him on a career path in academia. Curiosity about his roots eventually led him from salsa in the direction of Colombian music.

“I was very interested in questions about race, questions of identity,” he says. “And I found there’s also a very interesting story about Black Colombians, about the political process, about the place of music and culture within the political process. So I just found all of that stuff really, really fascinating. And, you know, 21 years later, here I am.”

Music as “Liberation Technology”

Birenbaum Quintero started his academic career with a paper on champeta music , a danceable mash-up of Caribbean and African influences that developed mainly in Cartagena, a busy Caribbean port.

“Decades before world music became part of the music industry in the US and Europe,” he says, “working-class Afro-Colombians were bringing in popular music from across the Black world—Congo, South Africa, Haiti, Jamaica—even when it wasn’t in Spanish, and dancing to it on gigantic speakers featuring electronic effects. This cosmopolitan, technophilic music scene, in this unexpected place, birthed champeta.”

Eventually, he moved on to all-percussion currulao music , which grew among the Afro-Colombian population along Colombia’s Pacific coast, where “it’s really, really isolated,” he says.

“The mountains separate the region from the rest of the country,” he says. “There’s not really any roads; people live in the rainforest. And they go up and down through rivers, and the rivers go east to west, so everything goes to the Pacific. It’s a very, very cutoff, underdeveloped part of the country. And the traditional music that’s there in the southern part of the Pacific coast is gorgeous, beautiful, very powerful, and sounds very, very raw.”

Black Colombians had won the right to collective territory—something like Indian reservations in the US—from the country’s government, he says, and music played an important part in the ways in which they were able to “prove” to the government that they were a separate ethnicity with a specific culture tied to the territory.

“Various strains of currulao play different roles in Afro-Colombian life,” he says, and the deep connection of music and culture is undeniable. “For example, if you look at this marimba, look at the keys, they’re made out of this wood from a specific palm tree called a chonta. And when you cut down a trunk of palm, you’re supposed to cut it down when it’s a new moon, not a full moon.

“When I first heard that, I was like, okay, whatever, they just make this stuff up. But actually, there are scientific reasons for that, which is that the water table is lower during the new moon, which means that it [the wood] dries more quickly. So there’s a lot of relationships with the natural environment and knowledge about the natural environment and the world and so on, that go into that music.”

One result of all his study is his book, Rites, Rights & Rhythms: A Genealogy of Musical Meaning in Colombia’s Black Pacific (Oxford University Press, 2018), which was awarded the 2020 Ruth Stone Prize by the Society for Ethnomusicology for most distinguished first book.

Champeta and currulao are very different and distinct musics and cultures, but they share a social profile with other strains of music in the African diaspora around the Americas.

“Like many countries in the Americas,” Birenbaum Quintero says, “Colombia has a Black population that was enslaved. And the legacy of that is different in different places—not only different between the United States and the rest of the Americas, but also different between Brazil and Colombia and the Dominican Republic, between Haiti and Jamaica.

“In all of these places,” he says, “it’s different because the history is different, but there is racism and white supremacy. And the music, traditional music and some popular music, is a sort of liberation technology. It’s a way to remember things, to pass on things, to create space for community.”

The music, traditional music and some popular music, is a sort of liberation technology. It’s a way to remember things, to pass on things, to create space for community. Michael Birenbaum Quintero

This understanding has been a defining concept of his work—and his involvement in Colombia now goes beyond academic and musical study: he’s helped organize a grassroots Afro-Colombian community music archive; designed cultural policy initiatives with the Colombian Ministry of Culture; performed traditional music and organized tours with Colombian musicians; and even cocomposed a PSA jingle for the Colombian census. He’s appeared on the Afropop Worldwide podcast and NPR to talk about his work.

Following the Musical Crosscurrents Back to Africa

In recent years, Birenbaum Quintero has expanded his interests beyond Colombia to drum-based Afro-Cuban batá music, played on a set of three hand drums and associated with religious practices known as Regla de Ocha in Cuba—or, somewhat pejoratively, as Santeria. The faith, which emerged from enslaved people from the Yoruba ethnicity who recreated their spiritual tradition in the Americas, was illegal in Cuba for much of the 20th century.

But the music made its way to the US, particularly New York, in the 1960s and ’70s, forging religious, political, and identity-based connections between Puerto Ricans, African Americans, Afro-Cubans, and Africans. Without drums to make their own music, says Birenbaum Quintero, people began improvising—building their own, gluing different drums together.

“It was a time of foment” in communities of color then, Birenbaum Quintero says, in New York and elsewhere. “People were having a political, religious, and musical awakening at the same time.”

Musicians like John Coltrane and cultural leaders, including writer Amiri Baraka, connected with traditional ritual and musical practices, like batá, that linked them to African roots and traditions. As the sixties vibe faded, percussionists from Cuba and Puerto Rico, including Milton Cardona, Orlando “Puntilla” Rios, and Daniel Ponce, became session musicians, playing with downtown musical luminaries who had also picked up on the beat, such as Laurie Anderson, David Byrne, Herbie Hancock, and Afrika Bambaataa.

“There’s a couple of different movements that people think about in isolation, but don’t think of as having a relationship with each other: post-punk, world music, and this downtown discovery of hip-hop and of Afro-Cuban music being played in Latino populations uptown,” Birenbaum Quintero says.

All of these musical crosscurrents can eventually be traced back to Africa.

Birenbaum Quintero has followed the sound, spending six weeks in Nigeria in the summer of 2023 exploring the drum-based soundscapes and words that accompany Yoruban Ifá rituals. “They talk about everything,” he says. “They talk about ethics, philosophy, sex; they tell dirty jokes; they talk a lot about listening; and they talk a lot about sound. So, I went to listen to the sound that was happening around these rituals, and to collect some of these texts.”

He wants to take Ifá seriously as an African philosophy, he says. There is a field of study in the Western academy, called sound studies, that looks at how people understand the world through sound—and Ifá has ideas about that.

“I did so much video there of things that I’m still trying to understand, that I think I’m going to be chewing on it for like 20 years,” he says.

Explore Related Topics:

- Share this story

- 0 Comments Add

Staff Writer

Joel Brown is a staff writer at BU Today and Bostonia magazine. He’s written more than 700 stories for the Boston Globe and has also written for the Boston Herald and the Greenfield Recorder . Profile

Jake Belcher Profile

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

Post a comment. Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Latest from The Brink

Oxygen produced in the deep sea raises questions about extraterrestrial life, the histories of enslaved people were written by slavers. a bu researcher is working to change that, making mri more globally accessible: how metamaterials offer affordable, high-impact solutions, “i love this work, but it’s killing me”: the unique toll of being a spiritual leader today, feeling the heat researchers say heat waves will put more older adults in danger, what the history of boston’s harbor can teach us about its uncertain future, eng’s mark grinstaff one of six researchers to receive nsf trailblazer engineering impact awards, how do we solve america’s affordable housing crisis bu research helps inspire a federal bill that suggests answers, missile defense won’t save us from growing nuclear arsenals, this ai software can make diagnosing dementia easier and faster for doctors, suicide now the primary cause of death among active duty us soldiers, state laws banning abortion linked to increases in mental health issues, scuba diving safely for marine biology research, heat waves are scorching boston, but are some neighborhoods hotter than others, six bu researchers win prestigious early-career award to advance their work, new ai program from bu researchers could predict likelihood of alzheimer’s disease, being open about lgbtq+ identities in the classroom creates positive learning environments, should schools struggling with classroom management clamp down with more suspensions or turn to restorative justice, getting police officers to trust implicit bias training, the solar system may have passed through dense interstellar cloud 2 million years ago, altering earth’s climate.

- Politics & Social Sciences

- Anthropology

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Caribbean cultural identity; the case of Jamaica, an essay in cultural dynamics. Paperback – Import, January 1, 1978

- Print length 239 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Institute of Jamaica

- Publication date January 1, 1978

- See all details

Product details

- ASIN : B0000EE0XI

- Publisher : Institute of Jamaica (January 1, 1978)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 239 pages

- Item Weight : 1.74 pounds

About the author

Rex m. nettleford.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 62% 0% 0% 38% 0% 62%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 62% 0% 0% 38% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 62% 0% 0% 38% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 62% 0% 0% 38% 0% 38%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 62% 0% 0% 38% 0% 0%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Advertisement

Supported by

Behind the Obama-Harris Friendship: A Key Endorsement and a Kindred Spirit