The Socratic Journey of Faith and Reason

Western Civilization was built on the transcendentals of Truth, Beauty, and Goodness. In this blog you will get unique, comprehensive, and integrated perspective on how philosophy, theology and art built Western Civilization and why it is in trouble today. I welcome you if you are a first time visitor. If you like what you see, please like and subscribe. Thank you!

8. Socrates and the Unexamined Life

“The unexamined life is not worth living.” 1 -Plato’s Apology , 38a

This now famous line, which Socrates spoke at his trial, has rippled throughout Western Civilization. If I could sum up Socrates’ legacy in one maxim, it would be this quote. We must know ourselves and by extension the reason why we are here.

Socrates may have gotten this idea from the phrase, “know thyself (γνῶθι σεαυτόν), that was inscribed on the temple of Delphi. 2 Or he may have first learned it by reading the works of Heraclitus . Regardless, the important thing is that he burned this idea of self-examination into the collective conscience of Western Civilization by proclaiming. It’s non-negotiable as he faced death by execution.

The famous inscription on the Temple of Delphi was more than a maxim. It was a warning for those who wished to be initiated into the higher mysteries of the divine nature. One could not proceed into the higher mysteries without a proper self-understanding. Knowing thyself then was the doorway into union with the divine. And union with the divine was the catalyst through both divine and human universe myteries, would eventually unfold.

Many Greeks gave lip service to this idea of self-examination, but Socrates lived it. Socrates taught that we need to start from a position of knowing that we are ignorant, rather than thinking we know more than we do. The first step is knowing that we don’t know. Humility is a prerequisite for wisdom. The modern West is characterized by a hubris. That does not allow such an admission and therefore relegates us to not only an ignorance of our ignorance,. But, an ignorance of the wisdom necessary in order to build a vibrant and prosperous and God-centered civilization characterized by truth, beauty, and goodness.

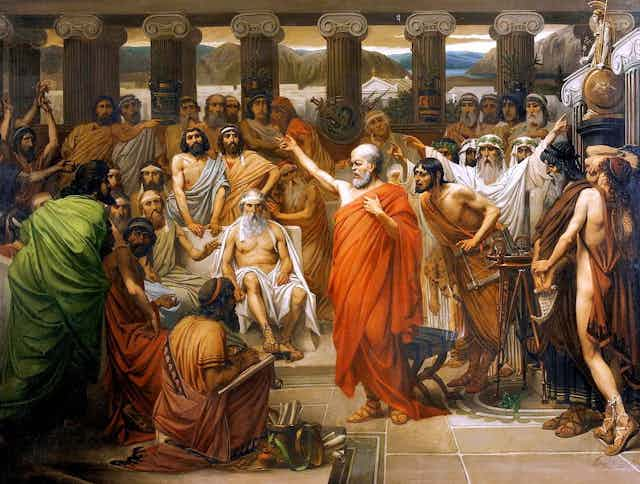

Socrates not only embraced this idea of self-examination, but his goal was to have the city of Athens do the same. That was his purpose. He saw himself as one whose mission it was to raise Athens out of its stupor. And, to set its sights on the transcendent. Consider the following quote:

“I am far from making a defense now on my own behalf, as might be thought, but on yours, to prevent you from wrongdoing by mistreating the God’s gift to you by condemning me; for if you kill me you will not easily find another like me. I was attached to this city by the god as upon a great and noble horse which was somewhat sluggish because of its size and needed to be stirred up by a kind of gadfly. It is to fulfill some such function that I believe the god has placed me in the city.” 3 -Plato’s Apology , 30 d-e

Socrates’ Purpose

Notice that Socrates conveys a sense of purpose in regards to his mission. But also a sense of humility as well. He was charged by the gods to stir Athens up out of its sluggishness. But his role was that of merely a “gadfly.” What Socrates did not realize was that his legacy was not only to stir up Athens, for that would be too small of a thing, but to stir up Western civilization as well. And that includes us. He is asking us to examine our lives to discover our particular God-given purpose. This, I claim, is his main legacy.

What gave credibility to this and what separated him from the Sophists is that he lived a life of virtue, rather than just telling others to do so. He practiced what he preached. He lived a life of poverty, refusing to get rich off of speaking fees like the Sophists. In other words, he didn’t “sell out.” Consider the following Socrates quote:

“That I am the kind of person to be a gift of god to this city, you might realize from the fact that it does not seem like human nature for me to have neglected all my own affairs and to have tolerated this neglect for so many years while I was always concerned with you, approaching each one of you like a father or an elder brother to persuade you to care for virtue.” 4 -Plato’s Apology , 31 a-c

We can hear echoes of St. Paul in this quote who, in his New Testament writings, said that he suffered much and was deprived in order that he could care for his spiritual children. 5

The Art of Self-Examination – Personality

In regards to self-examination, many people do not even know where to begin. We don’t even realize that self-examination is essential for a fulfilled life. We sometimes equate self-examination with self-centeredness, morbid introspection, or even narcissism, when actually it is just the opposite. A self-centered person is too self focused to see himself or herself objectively. They are to lost in themselves, to see their purpose in relationship to other people people, their environment, and God. Proper and periodic self-examination is the mark of a healthy individual. But it takes a lifetime and it occurs on on various levels of complexity. We all have a sense of trying to find our purpose, where in the world we fit in.

It is always good to start with one’s temperament, with questions like – are you an introvert or an extrovert? The world need both types of people to make things work. But often in an extroverted society like ours, the introvert, who does not recognize themselves as an introvert, usually struggles. An introvert, who needs to think to come up with good ideas will often find that his work environment does not provide for such practices. Rather, it is full of “team building” practices and constant activity that can leave an introvert drained.

Likewise, spiritual “retreats” are often anything but. They are oftentimes filled with constant activities, leaving no room for contemplation and prayer. For introverts, a good place for self-examination is to recognize that they are introverts and to adjust accordingly. The same holds true for extroverts that find themselves in more contemplative societies or communities. We must understand our temperamental tendencies and what energizes us and adjust accordingly.

From Hippocrates to Myers-Briggs

One can go deeper into understanding oneself by considering the what the Greek physician Hippocrates (c. 460 – c. 370 BC) deemed the four temperaments – sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic. 6 The sanguine is outgoing, but can be diffuse. The choleric is goal driven, but can be angry. The melancholic is a deep thinker, but oftentimes depressed. And the phlegmatic is calm and stable, but can be sluggish and unproductive. Most people are a mixture of these in different proportions with usually one dominating. I used to attend a church that used these in counseling and found that they can be quite useful. But, one can take it too far and start “pigeonholing” people. Like anything else, if used in moderation, it can be very helpful.

Finally, if you want to get real technical, you can use the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator ® (MBTI ® ), also known as the 16 personality types. 7 We all know this test by initials such as ISTJ, etc. For more information on this, please click the link below. This is the test most often used in large corporations. I took it myself and found it very useful.

The Art of Self-Examination – Human Nature

Temperament is just one aspect of self-examination, but we must go deeper still. Another aspect of self-examination is probing the mysteries of human nature. What does it mean to by human verses non-human? What makes us different? As a society, we have lost our way in understanding human nature. And if we don’t understand who we are, we will never know true happiness, the deep sense of well-being and blessedness that Aristotle termed eudaimonia .

This is unfortunate because there is so much confusion in the West in regards to things like race and sex. Our society is unraveling at an ever increasing speed. I remain optimistic that there will be a time in the not-to-distant future where philosophers, theologians, and scientists could all work together once again to develop an understanding of what it means to be human. Many modern intellectuals think they know, but the don’t. And like Socrates said, the starting point is admitting that we don’t know. That is a large barrier to surmount indeed.

We are in a bad place today wrought by much confusion and despair. Because, understanding human nature has been left up to the scientists and psychologists only. By neglecting the spiritual and ontological aspects of human nature, we get a truncated view of what it means to be a human. This is why our leaders, academic, medical, and political, continually churn out, like a defective machine, woefully inadequate answers to life questions.

Talent and Virtue

Another aspect of self-examination is in evaluating our talents – the things of which we are naturally gifted. But specifically, one can drill down into his or her own proclivities, talents, etc., and to develop those over time. Since we Americans are so pragmatic, we have to be careful not to define our talents too narrowly in terms of what is “useful” or vocationally oriented. One might be good a writing poetry even though they will never earn a living by doing so. On the other hand, if God has given you the ability to make money or had given you a lot of money, then you have many opportunities to help the poor or to donate to worthy causes such as stopping modern day infanticide.

And then there is the component of morality or virtue. Aristotle would have us examine ourselves in relation to the four cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance. These virtues and separate yet unified. It is really impossible, if we are to live a life of integrity, to be doing very well in three of the four virtues and terrible in the fourth. For example, we can delude ourselves into thinking that we treat people with justice, are not governed by fear, make decisions with prudence, but are an alcoholic. It doesn’t work that way.

Nevertheless, the prudent thing to do is to examine ourselves to find out which of the four virtues we need to work on. We can set long term goals and short term objectives. For example, if we have a fear of social situations, we can learn over time to expose ourselves to those situations until we eventually overcome that fear.

The best definition of integrity that I know is William Shakespeare’s famous quote from Hamlet, “This above all – to thine own self be true.” 10 And the corollary to that statement is – how can one know how to be true to oneself, if one does not know who they are.

Sun Tzu and the Art of War (and Business)

Sun Tzu (544-496 BC), was a Chinese general, military strategist, and philosopher. We know him as the author The Art of War, that world famous treatise on military strategy. I commonly apply his military wisdom to business competition. One of my favorite sayings of his is that you must know yourself and your enemy. 11 If you do, then you will have victory one hundred times out of one hundred. If you know yourself and not your enemy, then you will have a defeat for every victory.

And finally, if you know neither yourself nor your enemy, you will never have victory. If you are in business, it helps to know what your strengths and weaknesses are juxtaposed to your competition. Don’t try to match your competition’s strength if that is your weakness. Usually, a certain strength will be accompanied by a specific weakness and vice versa. The best situation is where a specific strength that you have corresponds to your competition’s weakness.

Self-Examination and the Soul

This theme of self-examination has a rich history in Christian thought. St. Augustine picked up on this almost a thousand years later when he said in a beautiful poem, “Lord Jesus, let me know myself and know thee.” 12 St. Augustine, along with many other saints, stressed this idea of examining our consciences to understand the sinful tendencies that hinder us from knowing God. It also works the other way as well. As we encounter God, we understand ourselves better. This comports with what the Hebrew Psalmist said,

“Search me, O God, and know my heart. Try me and know my thoughts. And see if there be any wicked way in me, and lead me in the way everlasting.” -Psalm 139:23-24

With the presuppositions of evolutionary biology, then everything that we do is biologically or materially based including our rationality and mental faculties. If we accept these presuppositions, then we become severely limited in our understanding of the human person as we place ourselves in a materialistic prison. This leads to a very erroneous and misguided understanding of ourselves, not to mention dangerous and destructive political and cultural applications. For example, during the COVID outbreak of 2020, the only focus of safety by the powers that by was physical safety. There was no regard or concern by our incompetent overlords for mental and emotional wellbeing. This is because they saw bodies sans souls.

On the other hand, if we accept the true proposition that we are spiritual beings with a soul as well as a body. Then, suddenly everything changes as we are released from our materialistic and nihilistic prison. This enables us to flourish as we live according to our God-given potential. If it is indeed true that we are created in God’s image, then even though we are finite creatures. In reality, we carry inside of us an infinite component of Deity. For those who are Christians and are united to Jesus Christ through the Holy Spirit, this aspect is compounded to an even greater degree.

So rather than being in a materialistic prison, we are freed to explore our infinite selves. If this be the case, then we can never fully plumb the depths of who we are as creatures made in God’s image. There will always be more to learn about ourselves, our spouses, and those with whom we are in relationship. In addition, we now can come to grips with the high calling of reflecting the character of God. The implications of this are endless. We cannot and will not restore and renew the West unless we come to grips with this fundamental fact.

From Self-Examination to Self-Centeredness in Modernity

Socrates sought virtue and thus lived a life of virtue. Some 20th century philosophers like Aldous Huxley have gone in the opposite direction. They desired to live lives of sexual wantonness and therefore sought belief systems to justify their behavior. Rather than seeking a divine purpose, they sought their own pleasures. Modern man has sought his end, not in a higher calling, but in himself. He is turned inward upon himself into a nihilistic darkness. This is why he is so miserable. Consider the following abridged quote from Aldous Huxley, a 20th century philosopher:

“We objected to the morality because it interfered with our sexual freedom. There was one admirably simple method of confuting these people and at the same time justifying ourselves in our political and erotic revolt: we could deny that the world had any meaning whatsoever.” 13

To deny the divine leads to nihilism. The god that we have created is one of nihilism as Huxley has stated above. It came to the fore in the West in the early to mid 20th century with the likes of Kafka, Camus, and Sartre. They didn’t invent this modern pessimistic philosophy from nothing, they simply tapped into the alienation and meaninglessness that proliferated in the West as a result of the prevailing secularism. Today, some people deal with their emptiness by adopting a frenetic lifestyle so that they don’t have time to think about their situation. Others deal with the emptiness by numbing their pain through things like pornography and substance abuse. Some even escape through suicide.

Like ancient Athens, we too need to be awakened out of our slumber and revived from our sluggishness. We too have sunk into the doldrums where we are only seeking the earthly and not the heavenly. Wisdom, according to Socrates, involves reorienting ourselves toward God, to examine ourselves and discover our purpose in light of the divine. Only then does life become meaningful and worth living. Maybe, like Socrates, we could act as gadflies within our culture to this end. Socrates knew his purpose for living. Do you know yours?

Aeschylus, a Greek Playwright, circa 500 B.C. 14 said:

“Know Thyself.” -Prometheus Bound, v. 309

Finally, consider the following question:

It seems that narcissism has replaced healthy self examination. Why do you thing this is so? Please leave your comment below and don’t forget to subscribe. Thank you!

Deo Gratias

Type your email…

Featured Book:

From Amazon: Humility is the key to all the virtues. It’s the necessary foundation for growth in all the others. If we do not know ourselves—if we cannot see our flaws and strengths (but especially our flaws)—clearly, how can we grow in virtue? How can we begin to make ourselves less and God more?

- Plato, Apology, 38a, Five Dialogues, Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Meno, Phaedo, second ed., Translated by G.M.A. Grube, Revised by John M. Cooper, p. 41, Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., Indianapolis/Cambridge, 2002

- From the article “Delphi,” New World Encyclopedia, https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Delphi

- Plato, Five Dialogues, Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Meno, Phaedo, second ed., 30 d-e, pp. 34-35

- Plato, Five Dialogues, Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Meno, Phaedo, second ed., 31 a-c, pp. 35

- New Testament, 1 Corinthians 4:8-17

- McIntosh, Matthew A. Editor-in-Chief, “The ‘Four Temperaments’ in Ancient and Medieval Medicine,” A Bold Blend of News and Ideas, October 23, 2020, Please click this link for a thought provoking discussion of the four temperaments – https://brewminate.com/the-four-temperaments-in-ancient-and-medieval-medicine/

- https://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/mbti-basics/

- Theology of the Body Institute – https://tobinstitute.org/

- https://shop.corproject.com/collections/books/products/man-and-woman-he-created-them

- Shakespeare, William, Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 3

- Sun Tzu, The Art of War, Translated by James Trapp, Michael Spilling, Project Editor, Designed by Rajdip Sanghera, p.21, Printed and bound in China, Chartwell Books, Inc., New York, 2012, copywrite by Amber Books Ltd., London, UK, 2011

- Kosloski, Philip, “‘Let me know myself’: A beautiful prayer written by St. Augustine,” Aleteia website, 2018, To see the complete prayer, please click the following link – https://aleteia.org/2018/09/16/let-me-know-myself-a-beautiful-prayer-written-by-st-augustine/

- Conner, Frederick W. “‘Attention’!: Aldous Huxley’s Epistemological Route to Salvation.” The Sewanee Review , vol. 81, no. 2, 1973, pp. 282–308. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/27542724 .

- Aeschylus, from the play Prometheus Bound , http://classics.mit.edu/Aeschylus/prometheus.html

- See Post 63 entitled “Plato’s Dialogues: Alcibiades and the Challenge of Self-Examination” to read one of Plato’s earliest dialogues where we encounter Socrates exploring how to properly examine oneself.

Sources and Bibliography:

Aeschylus; Vellacott, Philip, Prometheus Bound and Other Plays: Prometheus Bound, The Suppliants, Seven Against Thebes, The Persians , Penguin Classics, New York, 1961

Clayton, David, The Vision For You: How to Discover the Life You Were Made For , Independently Published, 2018

Coppleston, S.J., Frederick, A History of Philosophy, Book One, An Image Book, Doubleday, New York, 1985

Gerth, Holley, The Powerful Purpose of Introverts: Why the World Needs You to Be You , illustrated paperback, Revell Publishing Group, Ada, Michigan, 2020

Grayland, A.C., The History of Philosophy, Penguin Press, New York, 2019

Hock, Father Conrad, Know Yourself Through the Four Temperaments , Create Space Publishing, Scotts Valley, CA, 2018

Hughes, Bettany, The Hemlock Cup: Socrates, Athens and the Search for the Good Life Paperback – Illustrated, Vintage Publishers, 2012, New York City

John Paul II, author; Michael Waldstein, translator, Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body , Pauline Books & Media, Jamaica Plain, MA, Second Printing edition 2006

Laney, Marti Olsen, The Introvert Advantage: How Quiet People Can Thrive in an Extrovert World , 1st paperback ed., Workman Publishing Company, New York, 2002

Plato, Five Dialogues, Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Meno, Phaedo, second ed., Translated by G.M.A. Grube, Revised by John M. Cooper, Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., Indianapolis/Cambridge, 2002

Plato, The Last Days of Socrates , Revised Ed., Harold Tarrant (Editor, Translator, Introduction) and Hugh Tredennick (Translator), Penguin Classics, New York, 2003

Sun Tzu, The Art of War, Translated by James Trapp, Michael Spilling, Project Editor, Designed by Rajdip Sanghera, Printed and bound in China, Chartwell Books, Inc., New York, 2012, copywrite by Amber Books Ltd., London, UK, 2011

Voegelin, Eric, Order and History, Vol. 2: The World of the Polis , classic reprint hardcover, Forgotten Books Publishers, London, 2018

Wilson, Emily, The Death of Socrates, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2007

Xenophon, Conversations of Socrates, Waterfield, Robin H, Editor and Translator; Tedennick, Hugh, Translator, Penguin Classics, Ney York, Revised ed., 1990

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Join the Conversation

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of new posts by email.

Thank you! Will do. I appreciate the suggestion.

Hello, First I would like to congratulate you on the blog. I think it is an excellent way to delve into the Catholic religion and Platonic philosophy. I am writing to suggest that you put the bibliography in all Plato citations, Example: Criton 49e, to enrich the reading Regards

Your comments are very poignant, poetic, and heartfelt. It made me realize that the world redirects our natural yearnings away from the sublime to the material and temporal and thus misery and frustration ensues. Why do we let the world do this to us? We choose the misery of the temporal over the beauty of the eternal. Most people never realize that the goal of all existence is what is called the Beatific Vision, seeing God face to face. I would be interested to read other people’s responses to Ben’s insightful comments.

I feel that we have fallen from true self-reflection and self- examination in the Socratic fashion. The question has led me on an ongoing journey that is amazing and beautiful as it is terrifying. Though multifaceted, I believe that our obsession with science, material wealth and technology has driven us largely away from God. It’s now all about keeping up with the Joneses at the end of the block. No one is satisfied with nihilism and narcissism which leads to a downward spiral away from true self and towards material and egotistical vanity. I believe we need to look deep into ourselves and into the universe as we fathom eternity, this craving for higher purpose. My question to you and the collective, as existence is a shared experience, how do we stir these yearnings?

Socrates: 'The unexamined life is not worth living.'

The unexamined life is not worth living.

The quote, "The unexamined life is not worth living," attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, carries a profound meaning that invites us to examine our own existence and choices. Socrates believed that a life devoid of introspection, self-reflection, and critical thinking is essentially meaningless and lacks value. This quote emphasizes the importance of self-awareness and questioning one's beliefs, actions, and purpose in life.At a glance, this quote encourages individuals to engage in self-reflection to discover their true passions and values. When we take the time to examine our lives, we become more aware of our desires, dreams, and aspirations. By questioning our thoughts and actions, we gain a deeper understanding of our motivations and the impact they have on ourselves and those around us. Through self-examination, we can align our lives with our authentic selves, leading to a sense of fulfillment and purpose.However, looking beyond the surface meaning of this quote, it also connects to a broader philosophical concept known as existentialism. Existentialism delves into the deeper questions of human existence, transcending the simple act of self-examination. It explores the meaning of life and the power of individual agency in creating one's own purpose.Existentialists argue that humans possess free will and must take responsibility for their actions and choices. They contend that life doesn't inherently have a predefined meaning or purpose but that individuals can create their own meaning through conscious decision-making. This concept challenges the notion that self-examination is solely about discovering one's passions and aligning with them, but rather about actively forging one's own path and defining their existence.When we incorporate the existentialist perspective into Socrates' quote, it adds a layer of complexity and depth. It invites us to not only examine our lives but also to actively shape and create them. Instead of merely accepting the circumstances we find ourselves in, we are called to take charge and become co-creators of our reality. By doing so, we can find meaning, purpose, and fulfillment in even the most challenging and uncertain situations.While the existentialist perspective might seem overwhelming or burdensome to some, it presents an opportunity for personal growth, self-discovery, and liberation. It challenges us to confront difficult questions about our values, beliefs, and the impermanence of existence. By accepting the responsibility to create our own purpose, we transcend the limitations imposed by societal expectations and cultural norms, enabling us to lead more authentic and fulfilling lives.Ultimately, Socrates' quote, "The unexamined life is not worth living," acts as a catalyst for self-reflection and self-discovery. It invites us to go beyond the superficial and to delve deep into the core of our being. By embracing the principles of existentialism, we recognize that we have the power to shape our lives and find meaning in the face of uncertainty. In doing so, we embark on a profound journey of personal growth and self-actualization, turning the examined life into one filled with purpose, passion, and genuine fulfillment.

Socrates: 'Beauty is a short-lived tyranny.'

Socrates: 'death may be the greatest of all human blessings.'.

Socrates: Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living Report

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Works cited.

During his trial at Athens, Socrates said, “Unexamined life is not worthy living” (Baggini). Socrates was tried in court for having encouraged his students to challenge the accepted beliefs or traditions in society (Stern 16). The court gave Socrates several options to choose from, to go in exile, remain silent, or face execution (Stern 18). Socrates chooses to be hanged instead of running away or being silent. He argues that there is no point in living without awareness of what is around you by questioning (Stern 30). Socrates made a decision to be hanged since he believed that living a life where one could not evaluate the world and look for ways of making it better was not worth living. Because of his decision, Socrates was sentenced to death (Stern 30).

By saying that “unexamined life is not worthy living”, Socrates was referring to freedom, a state of making choices about your surrounding, a state of choosing your destination, having the freedom to criticize issues, setting your goals in life, and deciding whether what you are doing is right or wrong (Baggini). In general, Socrates was referring to individuals having the opportunity to understand or know themselves. An examined life is taking control of your life.

To Socrates, life imprisonment would make his life not worth living. This would take his freedom away; he would not have an opportunity to decide what was right or wrong for him (Stern 15). He would no longer examine his environment, nobody would assess his ideas, and neither would he determine his destination. Examining once life is an opportunity to acquire freedom. Having a chance to examine your own life presents you with opportunities to control your life and choose your destiny.

In very simple terms, the unexamined life is a situation in which an individual is not open to question what is around them and what they do (Stern 13). Living unexamined life is living a life, which is not unique, a life that does not reveal new perspectives or ideas; it is a life that has not been appreciated by others in any way (Baggini).

ConclusionIn addition, it is important for individuals to know what is right and wrong in their life. For instance, individuals need to identify their success and failures as well as the reason for the kind of life that they live (Baggini). Socrates chooses death over a confined life because he believed in self-evaluation and knowledge. His choice of death rather than running away or silence is a message that we should appreciate what we believe in rather than living the way other people do or want us to live (Stern 20).

Stern, Paul. Socratic rationalism and political philosophy: An interpretation of Plato’s . New York: Sunny Press, 1993. Print.

Baggini, Julian. The unexamined life is not worth living . 2005. Web.

- Philosophy: Hedonism and Desire Satisfaction Theory

- Moral and Contemporary Philosophy

- Researching Socrates and His Ideas

- What is the value of the examined life?

- The Holocaust: Historical Analysis

- The Doctrine of Negative Responsibility

- Immanuel Kant's and John Stuart Mill's Moral Philosophies

- Aristotle Philosophical Perspective

- Infanticide: the Practice of Killing a Newborn Baby

- Morality of Friedrich Nietzsche and Alasdair MacIntyre

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, January 27). Socrates: Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living. https://ivypanda.com/essays/socrates-unexamined-life-is-not-worth-living/

"Socrates: Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living." IvyPanda , 27 Jan. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/socrates-unexamined-life-is-not-worth-living/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Socrates: Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living'. 27 January.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Socrates: Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living." January 27, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/socrates-unexamined-life-is-not-worth-living/.

1. IvyPanda . "Socrates: Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living." January 27, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/socrates-unexamined-life-is-not-worth-living/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Socrates: Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living." January 27, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/socrates-unexamined-life-is-not-worth-living/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Explainer: Socrates and the life worth living

Lecturer in Philosophy and History, Bond University

Disclosure statement

Oscar Davis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Bond University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Socrates was notoriously annoying. He was likened to a gadfly buzzing around while one is trying to sleep. The Oracle of Delphi declared him the wisest of all human beings. His life and death would go on to shape the history of Western thought.

And yet he proclaimed to know nothing. The genius of Socrates lay in his professed ignorance of what it means to be human.

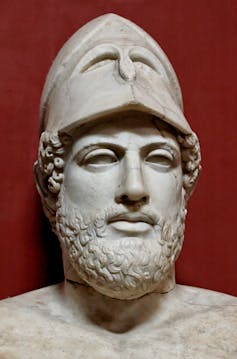

Socrates (469-399 BCE) grew up in Athens over two and half thousand years ago. At the time, the Athenians were recovering from a devastating war with the Persians. As they rebuilt, the military general and politician, Pericles, championed democracy as the form of government to bring Greece into its Golden Age.

The Athenians practised a direct (as opposed to representative) form of democracy. Any male over the age of 20 was obligated to take part. The officials of the assembly were randomly selected through a lottery process and could make executive pronouncements, such as deciding to go to war or banishing Athenian citizens.

The Athens of Pericles flourished. Bustling crowds of traders from around the Mediterranean gathered at the port of Piraeus. In the Athenian agoras – the central marketplaces and assembly areas – the active social and political lives of the Athenian citizens would inspire the mind of Socrates.

Socrates at war

Alcibiades, who would go on to become a prominent Athenian statesman and general, recounts a story of what might be a pivotal moment in the development of Socrates’ thinking.

One morning during the campaign of Potidaea , Socrates became transfixed by a problem that he could not seem to solve. An entire day passed and Socrates had still not moved. In awe, and probably curious to see how long he could keep it up, his fellow soldiers moved their beds outside to watch him during the night. It was not until dawn the next morning that Socrates said a prayer to the new day and walked away.

Jonathan Lear argues in his Tanner Lectures that Socrates is not just standing still because he is lost in thought; he is standing still because he cannot walk. He is standing “not knowing what his next step should be”. Socrates wants to move in the right direction, but does not know what direction that is.

We will never know what Socrates was thinking about. But after standing still and thinking, he appears to have become invigorated. Alcibiades tells us that in the battle that followed Socrates saved his life. For the remainder of the campaign, Socrates fought with a fierceness and bravery that exemplified true courage.

Read more: What is love? In pop culture, love is often depicted as a willingness to sacrifice, but ancient philosophers took a different view

Socrates the gadfly

Socrates never wrote anything down. He hungered for the lively exchange of ideas and believed that writing only served to imprison a thought in letters. He argued that the written word shared a strange quality with paintings. Both appear to us “like living beings, but if one asks them a question, they preserve a solemn silence”.

Much of what we know of Socrates’ activities and conversations, and his death, was recorded by his devoted student Plato. Scholarly debate continues about just how much of Plato’s written record of Socrates’ interrogations we can attribute to Socrates himself. At some point in the Platonic corpus, Socrates becomes a mouthpiece for Plato’s own ideas, but no one can agree precisely when.

Socrates was unsure of what to make of being called the wisest of all human beings. He dedicated his time to questioning fellow Athenians about the nature of things, interrogating ideas such as friendship, love, justice and piety. He was searching for what he believed to be the highest good: knowledge.

The gadfly could show up anywhere. In Plato’s Euthyphro , for example, Socrates bumps into Euthyphro, who is on his way to court about to prosecute his father:

What strange thing has happened, Socrates, that you have left your accustomed haunts in the Lyceum and are now haunting the portico where the king archon sits?

Socrates is intrigued by Euthyphro’s legal case, and so begins his inquiry:

do you think your knowledge about divine laws and holiness […] is so exact that […] you are not afraid of doing something unholy yourself in prosecuting your father for murder?

Almost every Socratic dialogue is centred around Socrates’ recognition of his own ignorance. In Euthyphro, the subject he interrogates is piety. What follows adheres to a structure shared by most of the other dialogues, which is known as elenchus or the Socratic method.

Its basic form is as follows:

Socrates engages an interlocutor who appears to possess knowledge about an idea

the interlocutor makes an attempt to define the idea in question

Socrates asks a series of questions which test and unravel the interlocutor’s definition

the interlocutor tries to reassemble their definition, but Socrates repeats step three

both parties arrive at a state of perplexity, or aporia , in which neither can any further define the idea in question.

We can gain a sense of the frustration that this caused some of Socrates’ unwilling victims. Take the final lines of his encounter with Euthyphro as an example:

Socrates : Then don’t you see that now you say that what is precious to the gods is holy? And is not this what is dear to the gods? Euthyphro : Certainly. Socrates : Then either our agreement a while ago was wrong, or if that was right, we are wrong now. Euthyphro : So it seems. Socrates : Then we must begin again at the beginning and ask what holiness is. Since I shall not willingly give up until I learn. […] Euthyphro : Some other time, Socrates. Now I am in a hurry and it is time for me to go.

In Meno , another of Plato’s dialogues, Socrates likens the sting of aporia to that of an electric stingray:

I find you are merely bewitching me with your spells and incantations, which have reduced me to utter perplexity. And if I am indeed to have my jest, I consider that both in your appearance and in other respects you are extremely like the flat torpedo sea-fish; for it benumbs anyone who approaches and touches it, and something of the sort is what I find you have done to me now. For in truth I feel my soul and my tongue quite benumbed, and I am at a loss what answer to give you.

Throughout the dialogues, Socrates demonstrates the disruptive and disorientating experience of aporia, which emerges from philosophical activity. Reflecting upon the declaration of the Oracle of Delphi, we learn that Socrates was wise because, unlike his interlocutors, he did not proclaim to know what he was ignorant of.

Read more: Leaders as healers: Ancient Greek ideas on the health of the body politic

Corrupting the youth and replacing the gods

In the early days of democracy and in a society which was rapidly expanding, one would think that a revolutionary thinker like Socrates would be a highly prized instrument of intellectual progress. But not everyone appreciated the disorientating sting of the gadfly’s thinking.

Plato would later comment on how the Athenians – and perhaps societies in general – react when faced with the disruptive force of critical reflection.

His famous allegory of the cave, which forms part of his Republic , is in many ways the story of a philosopher – the story of his great teacher, Socrates.

The allegory begins with prisoners locked in a cave. All the prisoners can see are the shadows of the passing guards reflected on the wall, and the echoes of the world behind them. This is the condition of a society content with the mere illusions of knowledge, a society that is unreflective and stagnant.

One prisoner manages to escape. Turned towards the entry of the cave, he first notices the brightness of the light – like knowledge, the light is uncomfortable and disruptive after years of contentment with shadows.

Escaping the cave, the prisoner

can see the reflections of people and things in water and then later see the people and things themselves. Eventually, he is able to look at the stars and moon at night until finally he can look upon the sun itself.

Only after he is able to look straight at the “sun itself” – i.e. knowledge of what is good – “is he able to reason about it” and what it is. The freed prisoner, argues Plato, would realise that life outside is far superior to being inside the cave. He would return and encourage the prisoners to free themselves and look around. But the comfort of their belief in the world of shadows and echoes is a strong force to overcome.

Plato says that the prisoners, fearing what awaits outside of the cave, would react violently towards the freed prisoner – even killing him in order to keep the peace.

This was Socrates’ fate.

When the citizens of Athens had finally had enough of Socrates’ pestering questions, they banded together and accused him of corrupting the youth and attempting to replace the old gods.

He was imprisoned. His followers planned an escape, but he refused. Socrates questioned what was to be gained by escaping. Life itself is not ultimately valuable – surely, he says, it is a good and just life that we ultimately value. If he were to escape, he would only be tarnishing his good life with an act of vengeance against the misinformed Athenian citizens. He had nothing to gain by escaping. He could only preserve the harmony of his own soul by accepting his fate.

In his final stand in front of the Athenian judges, Socrates denies all charges. His only crime was forcing Athenians to think:

If again I say that to talk every day about virtue and the other things about which you hear me talking and examining myself and others is the greatest good to man, and that the unexamined life is not worth living, you will believe me still less.

If you are to put me to death, warns Socrates, you will not easily find another like me. Striking dead the gadfly of Athens is easy, but “then you would sleep on for the remainder of your lives, unless the god in his care of you gives you another gadfly”.

But the judges had made up their minds. The majority voted that Socrates would be executed by drinking hemlock.

Socrates teaches us that philosophical contemplation prepares us for the good life. The experience of aporia – in all of its discomfort and disruption – is the very catalyst of wonder. The philosopher, the lover of wisdom, is anyone who dares to escape the cave and look upon the sun, anyone who lives for the values Socrates died for.

- Greek philosophers

University Relations Manager

2024 Vice-Chancellor's Research Fellowships

Head of Research Computing & Data Solutions

Community member RANZCO Education Committee (Volunteer)

Director of STEM

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

- Introduction of moral codes

- Problems of divine origin

- Nonhuman behaviour

- Kinship and reciprocity

- Anthropology and ethics

- The Middle East

- Ancient Greece

- The Epicureans

- Ethics in the New Testament

- St. Augustine

- St. Thomas Aquinas and the Scholastics

- Machiavelli

- The first Protestants

- Early intuitionists: Cudworth, More, and Clarke

- Shaftesbury and the moral sense school

- Butler on self-interest and conscience

- The climax of moral sense theory: Hutcheson and Hume

- The intuitionist response: Price and Reid

- Moore and the naturalistic fallacy

- Modern intuitionism

- Existentialism

- Universal prescriptivism

- Moral realism

- Kantian constructivism: a middle ground?

- Irrealist views: projectivism and expressivism

- Ethics and reasons for action

- The debate over consequentialism

- Varieties of consequentialism

- Objections to consequentialism

- An ethics of prima facie duties

- Rawls’s theory of justice

- Rights theories

- Natural law ethics

- Virtue ethics

- Feminist ethics

- Ethical egoism

- Environmental ethics

- War and peace

- Abortion, euthanasia, and the value of human life

- What is ethics?

- How is ethics different from morality?

- Why does ethics matter?

- Is ethics a social science?

- What did Aristotle do?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Humanities LibreTexts - What is Ethics?

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Ethics and Contrastivism

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Empathy and Sympathy in Ethics

- VIVA Open Publishing - Ethics and Society - Ethical Behavior and Moral Values in Everyday Life

- Philosophy Basics - Ethics

- American Medical Association - Journal of Ethics - Triage and Ethics

- Psychology Today - Ethics and Morality

- Government of Canada - Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat - What is ethics?

- Cornell Law School - Legal Information Institute - Ethics

- ethics and morality - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Socrates, who once observed that “the unexamined life is not worth living,” must be regarded as one of the greatest teachers of ethics . Yet, unlike other figures of comparable importance, such as the Buddha or Confucius , he did not tell his audience how they should live. What Socrates taught was a method of inquiry. When the Sophists or their pupils boasted that they knew what justice , piety, temperance, or law was, Socrates would ask them to give an account, which he would then show was entirely inadequate. Because his method of inquiry threatened conventional beliefs, Socrates’ enemies contrived to have him put to death on a charge of corrupting the youth of Athens. For those who thought that adherence to the conventional moral code was more important than the cultivation of an inquiring mind, the charge was appropriate. By conventional standards, Socrates was indeed corrupting the youth of Athens, though he himself considered the destruction of beliefs that could not stand up to criticism as a necessary preliminary to the search for true knowledge. In this respect he differed from the Sophists, with their ethical relativism , for he thought that virtue is something that can be known and that the virtuous person is the one who knows what virtue is.

It is therefore not entirely accurate to regard Socrates as contributing a method of inquiry but as having no positive views of his own. He believed that virtue could be known, though he himself did not profess to know it. He also thought that anyone who knows what virtue is will necessarily act virtuously. Those who act badly, therefore, do so only because they are ignorant of, or mistaken about, the real nature of virtue. This belief may seem peculiar today, in large part because it is now common to distinguish between what a person ought to do and what is in his own interest. Once this assumption is made, it is easy to imagine circumstances in which a person knows what he ought to do but proceeds to do something else—what is in his own interests—instead. Indeed, how to provide self-interested (or merely rational) people with motivating reasons for doing what is right has been a major problem for Western ethics. In ancient Greece, however, the distinction between virtue and self-interest was not made—at least not in the clear-cut manner that it is today. The Greeks believed that virtue is good both for the individual and for the community . To be sure, they recognized that living virtuously might not be the best way to prosper financially; but then they did not assume, as people are prone to do today, that material wealth is a major factor in whether a person’s life goes well or ill.

Socrates’ greatest disciple , Plato, accepted the key Socratic beliefs in the objectivity of goodness and in the link between knowing what is good and doing it. He also took over the Socratic method of conducting philosophy , developing the case for his own positions by exposing errors and confusions in the arguments of his opponents. He did this by writing his works as dialogues in which Socrates is portrayed as engaging in argument with others, usually Sophists. The early dialogues are generally accepted as reasonably accurate accounts of the views of the historical Socrates, but the later ones, written many years after Socrates’ death, use the latter as a mouthpiece for ideas and arguments that were in fact original to Plato.

In the most famous of Plato’s dialogues, Politeia ( The Republic ), the character Socrates is challenged by the following example: Suppose a person obtained the legendary ring of Gyges , which has the magical property of rendering the wearer invisible. Would that person still have any reason to behave justly? Behind this challenge lies the suggestion, made by the Sophists and still heard today, that the only reason for acting justly is that one cannot get away with acting unjustly. Plato’s response to this challenge is a long argument developing a position that appears to go beyond anything the historical Socrates asserted. Plato maintained that true knowledge consists not in knowing particular things but in knowing something general that is common to all the particular cases. This view is obviously derived from the way in which Socrates pressed his opponents to go beyond merely describing particular acts that are (for example) good, temperate, or just and to give instead a general account of goodness, temperance, or justice . The implication is that one does not know what goodness is unless one can give such a general account. But the question then arises, what is it that one knows when one knows this general idea of goodness? Plato’s answer is that one knows the Form of the Good , a perfect, eternal, and changeless entity existing outside space and time, in which particular good things share, or “participate,” insofar as they are good.

It has been said that all of Western philosophy consists of footnotes to Plato. Certainly the central issue around which all of Western ethics has revolved can be traced to the debate between the Sophists, who claimed that goodness and justice are relative to the customs of each society—or, worse still, that they are merely a disguise for the interest of the stronger—and the Platonists, who maintained the possibility of knowledge of an objective Form of the Good.

But even if one could know what goodness or justice is, why should one act justly if one could profit by doing the opposite? This is the remaining part of the challenge posed by the tale of the ring of Gyges, and it is still to be answered. For even if one accepts that goodness is something objective, it does not follow that one has a sufficient reason to do what is good. One would have such a reason if it could be shown that goodness or justice leads, at least in the long run, to happiness ; as has been seen from the preceding discussion of early ethics in other cultures , this issue is a perennial topic for all who think about ethics.

According to Plato, justice exists in the individual when the three elements of the soul—intellect, emotion, and desire—act in harmony with each other. The unjust person lives in an unsatisfactory state of internal discord , trying always to overcome the discomfort of unsatisfied desire but never achieving anything better than the mere absence of want. The soul of the just person, on the other hand, is harmoniously ordered under the governance of reason , and the just person derives truly satisfying enjoyment from the pursuit of knowledge. Plato remarks that the highest pleasure, in fact, comes from intellectual speculation. He also gives an argument for the belief that the human soul is immortal; therefore, even if a just individual lives in poverty or suffers from illness, the gods will not neglect him in the next life, where he will have the greatest rewards of all. In summary, then, Plato asserts that we should act justly because in doing so we are “at one with ourselves and with the gods.”

Today, this may seem like a strange conception of justice and a farfetched view of what it takes to achieve human happiness. Plato does not recommend justice for its own sake, independent of any personal gains one might obtain from being a just person. This is characteristic of Greek ethics, which refused to recognize that there could be an irresolvable conflict between the interest of the individual and the good of the community. Not until the 18th century did a philosopher forcefully assert the importance of doing what is right simply because it is right, quite apart from self-interested motivation ( see below Kant ). To be sure, Plato did not hold that the motivation for each and every just act is some personal gain; on the contrary, the person who takes up justice will do what is just because it is just. Nevertheless, he accepted the assumption of his opponents that one could not recommend taking up justice in the first place unless doing so could be shown to be advantageous for oneself as well as for others.

Although many people now think differently about the connection between morality and self-interest, Plato’s attempt to argue that those who are just are in the long run happier than those who are unjust has had an enormous influence on Western ethics. Like Plato’s views on the objectivity of goodness, the claim that justice and personal happiness are linked has helped to frame the agenda for a debate that continues even today.

Plato founded a school of philosophy in Athens known as the Academy. There Aristotle, Plato’s younger contemporary and only rival in terms of influence on the course of Western philosophy, went to study. Aristotle was often fiercely critical of Plato, and his writing is very different in style and content, but the time they spent together is reflected in a considerable amount of common ground. Thus, Aristotle holds with Plato that the life of virtue is rewarding for the virtuous as well as beneficial for the community. Aristotle also agrees that the highest and most satisfying form of human existence involves the exercise of one’s rational faculties to the fullest extent. One major point of disagreement concerns Plato’s doctrine of Forms, which Aristotle rejected. Thus, Aristotle does not argue that in order to be good one must have knowledge of the Form of the Good.

Aristotle conceived of the universe as a hierarchy in which everything has a function. The highest form of existence is the life of the rational being, and the function of lower beings is to serve this form of life. From this perspective Aristotle defended slavery —because he considered barbarians less rational than Greeks and by nature suited to be “living tools”—and the killing of nonhuman animals for food and clothing. From this perspective also came a view of human nature and an ethical theory derived from it. All living things, Aristotle held, have inherent potentialities , which it is their nature to develop. This is the form of life properly suited to them and constitutes their goal. What, however, is the potentiality of human beings? For Aristotle this question turns out to be equivalent to asking what is distinctive about human beings; and this, of course, is the capacity to reason . The ultimate goal of humans, therefore, is to develop their reasoning powers. When they do this, they are living well, in accordance with their true nature, and they will find this the most rewarding existence possible.

Aristotle thus ends up agreeing with Plato that the life of the intellect is the most rewarding existence, though he was more realistic than Plato in suggesting that such a life would also contain the goods of material prosperity and close friendships. Aristotle’s argument for regarding the life of the intellect so highly, however, is different from Plato’s, and the difference is significant because Aristotle committed a fallacy that has often been repeated. The fallacy is to assume that whatever capacity distinguishes humans from other beings is, for that very reason, the highest and best of their capacities. Perhaps the ability to reason is the best human capacity, but one cannot be compelled to draw this conclusion from the fact that it is what is most distinctive of the human species.

A broader and still more pervasive fallacy underlies Aristotle’s ethics. It is the idea that an investigation of human nature can reveal what one ought to do. For Aristotle, an examination of a knife would reveal that its distinctive capacity is to cut, and from this one could conclude that a good knife is a knife that cuts well. In the same way, an examination of human nature should reveal the distinctive capacity of human beings, and from this one should be able to infer what it is to be a good human being . This line of thought makes sense if one thinks, as Aristotle did, that the universe as a whole has a purpose and that human beings exist as part of such a goal-directed scheme of things, but its error becomes glaring if this view is rejected and human existence is seen as the result of a blind process of evolution. Whereas the distinctive capacity of a knife is a result of the fact that knives are made for a specific purpose—and a good knife is thus one that fulfills this purpose well—human beings, according to modern biology , were not made with any particular purpose in mind. Their nature is the result of random forces of natural selection . Thus, human nature cannot, without further moral premises , determine how human beings ought to live.

Aristotle is also responsible for much later thinking about the virtues one should cultivate . In his most important ethical treatise , the Nicomachean Ethics , he sorts through the virtues as they were popularly understood in his day, specifying in each case what is truly virtuous and what is mistakenly thought to be so. Here he applies an idea that later came to be known as the Golden Mean ; it is essentially the same as the Buddha’s middle path between self-indulgence and self-renunciation. Thus, courage, for example, is the mean between two extremes: one can have a deficiency of it, which is cowardice, or one can have an excess of it, which is foolhardiness. The virtue of friendliness, to give another example, is the mean between obsequiousness and surliness.

Aristotle does not intend the idea of the mean to be applied mechanically in every instance: he says that in the case of the virtue of temperance, or self-restraint, it is easy to find the excess of self-indulgence in the physical pleasures, but the opposite error, insufficient concern for such pleasures, scarcely exists. (The Buddha, who had experienced the ascetic life of renunciation, would not have agreed.) This caution in the application of the idea is just as well, for while it may be a useful device for moral education, the notion of a mean cannot help one to discover new truths about virtue. One can determine the mean only if one already has a notion of what is an excess and what is a defect of the trait in question. But this is not something that can be discovered by a morally neutral inspection of the trait itself: one needs a prior conception of the virtue in order to decide what is excessive and what is defective. Thus, to attempt to use the doctrine of the mean to define the particular virtues would be to travel in a circle.

Aristotle’s list of the virtues and vices differs from lists compiled by later Christian thinkers. Although courage, temperance, and liberality are recognized as virtues in both periods, Aristotle also includes a virtue whose Greek name, megalopsyche , is sometimes translated as “ pride ,” though it literally means “greatness of soul.” This is the characteristic of holding a justified high opinion of oneself. For Christians the corresponding excess, vanity, was a vice, but the corresponding deficiency, humility, was a virtue.

Aristotle’s discussion of the virtue of justice has been the starting point of almost all Western accounts. He distinguishes between justice in the distribution of wealth or other goods and justice in reparation , as, for example, in punishing someone for a wrong he has done. The key element of justice, according to Aristotle, is treating like cases alike—an idea that set for later thinkers the task of working out which kinds of similarities (e.g., need, desert, talent) should be relevant. As with the notion of virtue as a mean, Aristotle’s conception of justice provides a framework that requires fleshing out before it can be put to use.

Aristotle distinguished between theoretical and practical wisdom . His conception of practical wisdom is significant, for it involves more than merely choosing the best means to whatever ends or goals one may have. The practically wise person also has the right ends. This implies that one’s ends are not purely a matter of brute desire or feeling; the right ends are something that can be known and reasoned about. It also gives rise to the problem that faced Socrates: How is it that people can know the difference between good and bad and still choose what is bad? As mentioned earlier, Socrates simply denied that this could happen, saying that those who did not choose the good must, appearances notwithstanding, be ignorant of what the good is. Aristotle said that this view was “plainly at variance with the observed facts,” and he offered instead a detailed account of the ways in which one can fail to act on one’s knowledge of the good, including the failure that results from lack of self-control and the failure caused by weakness of will.

Later Greek and Roman ethics

In ethics, as in many other fields, the later Greek and Roman periods do not display the same penetrating insight as the Classical period of 5th- and 4th-century Greek civilization. Nevertheless, the two schools of thought that dominated the later periods, Stoicism and Epicureanism , represent important approaches to the question of how one ought to live.

Liberal Arts

Thinking Now and Then

the unexamined life is not worth living

the unexamined life is not worth living Socrates (Plato, 1997, 33)

The unexamined life is not worth living is perhaps Socrates’ most famous quote and Socrates is perhaps the most widely known figure of philosophy. The words though don’t only belong to Socrates they also belong to his student Plato who wrote them.

The quote comes from Plato’s Apology, apologia in Greek, which in legal proceedings means defence speech. Plato’s Apology is a representation of Socrates real trial of 399 B.C. (2420 years ago) and although it can’t be known what was said at the trial, Plato’s version exists to ask some difficult philosophical questions.

Socrates stands accused of practising a mode of philosophy – socratic questioning – which his accusers claim “makes the worse argument the stronger”, teaches about “things in the sky and things below the earth”, and does not “believe in the gods” so is “corrupting the young”.

Despite Socrates defence the majority of the 501 jurors find him guilty, with one of his accusers (Meletus) calling for a death sentence. This is why Plato’s Apology is also known as the “The Death of Socrates”.

Unsurprised the 70 year old Socrates ponders an appropriate sentence by asking the jurors a difficult question

Clearly it should be a penalty I deserve, and what do I deserve to suffer or to pay because I have deliberately not led a quiet life but have neglected what occupies most people: wealth, household affairs, the position of general or public orator or the other offices, the political clubs and factions that exist in the city? I thought myself too honest to survive if I occupied myself with those things. I did not follow that path that would have made me of no use either to you or to myself, but I went to each of you privately and conferred upon him what I say is the greatest benefit, by trying to persuade him not to care for any of his belongings before caring that he himself should be as good and as wise as possible, not to care for the city’s possessions more than for the city itself, and to care for other things in the same way. What do I deserve for being such a man?

The unexamined life is not worth living in context

In Plato’s recount Socrates says the unexamined life is not worth living as a response to what he calls the slanders of the city against him. The extract below is from Plato’s Apology and begins around line 37 . The jury gives its verdict of guilty, and Meletus asks for the penalty of death to which Socrates replies:

I am convinced that I never willingly wrong anyone, but I am not convincing you of this, for we have talked together but a short time. If it were the law with us, as it is elsewhere, that a trial for life should not last one but many days, you would be convinced, but now it is not easy to dispel great slanders in a short time.

Since I am convinced that I wrong no one, I am not likely to wrong myself, to say that I deserve some evil and to make some such assessment against myself.

What should I fear? That I should suffer the penalty Meletus has assessed against me, of which I say I do not know whether it is good or bad?

Am I then to choose in preference to this something that I know very well to be an evil and assess the penalty at that?

Imprisonment? Why should I live in prison, always subjected to the ruling magistrates, the Eleven?

A fine, and imprisonment until I pay it? That would be the same thing for me, as I have no money.

Exile? for perhaps you might accept that assessment. I should have to be inordinately fond of life, men of Athens, to be so unreasonable as to suppose that other men will easily tolerate my company and conversation when you, my fellow citizens, have been unable to endure them, but found them a burden and resented them so that you are now seeking to get rid of them. Far from it, gentlemen.

It would be a fine life at my age to be driven out of one city after another, for I know very well that wherever I go the young men will listen to my talk as they do here. If I drive them away, they will themselves persuade their elders to drive me out; if I do not drive them away, their fathers and relations will drive me out on their behalf.

Perhaps someone might say: But Socrates, if you leave us will you not be able to live quietly, without talking? Now this is the most difficult point on which to convince some of you. If I say that it is impossible for me to keep quiet because that means disobeying the god, you will not believe me and will think I am being ironical.

On the other hand, if I say that it is the greatest good for a man to discuss virtue every day and those other things about which you hear me conversing and testing myself and others, for the unexamined life is not worth living for men, you will believe me even less.

The unexamined life is not worth living meaning

What does Socrates mean when he says the unexamined life is not worth living? Well firstly Socrates doesn’t expect you or the jurors to believe him.

A clue to what Socrates means is present in the first quote above. Socrates doesn’t believe in living a “quiet life”, that is one that exists with a quiet mind. For him this quiet life is one that would require him to be dishonest – to keep silent the questions that enter his mind.

For Socrates an unexamined life is also one focused on individual wealth and status over and above the wealth and health of the society (the city). Distracted and even driven by possessions this unexamined life gives no thought for wisdom or the good.

Socrates has witnessed the unexamined life in the city he lives and knows he can not live it. In fact for him the thought of doing so is worse than death. Rather than conform to the popular opinion that death is the worst of all things Socrates examines this idea critically.

Death for Socrates is an unknown and therefore he has no fear of what he does not know. He says ‘to fear death, gentleman, is no other than to think oneself wise when one is not, to think one knows what one does not know’. For Socrates an examined life means ‘I do not think I know what I do not know’.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE UNEXAMINED LIFE

Free Socrates Webinar

Learn more about Socrates in a free webinar by Think Learning

Plato’s Apology | Socrates On Trial | The Trial of Socrates

Thinking Now and Then.

Gillian Rose: Fascism and representation

Socrates On Trial

Žižek on the history of humanity and violence

Wherein Lies the Value of Art? Clive Bell’s Radical Aesthetic Vision

Is uni worth it? What’s the point of Higher Education?

The Souls of White Folk

Distorted Rhetoric and Forgotten Principles: How AOC is Reviving Oratory in the US

What did Max Weber mean by the ‘spirit’ of capitalism?

Paul Rée, Nietzsche, and the Myth of Libertas

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Volume 11 Issue 31

- > IS THE UNEXAMINED LIFE WORTH LIVING OR NOT?

Article contents

Is the unexamined life worth living or not.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 March 2012

According to Socrates, an unexamined life is not worth living. This view is controversial. Is the unexamined life worth living or not? Most philosophers disagree about the answer. While some argue for the worthlessness of an unexamined life, others support the superfluity of self critical examination. In his recent article, Jamison pooh-poohed the claim that an unexamined life is not worth living. According to Jamison, not only is an unexamined life worth living; the rigorous examination of life should not be encouraged due to its possible negative effects on the participants and the entire society. In Jamison's view, a consistent and unregulated examination of human life produces a feeling of ecstasy (a specie of spiritual feeling) in those who engage in it. The feeling, if allowed, could endanger both the thinker and the entire society. For Jamison, “once you get a taste of this kind of thing, you do not want to give it up”. Someone who engages in self-critical examination eventually becomes entangled with it. Socrates became entangled in dialectics, became unpopular, was accused of corrupting the youth and eventually sentenced to death.

Access options

1 See Plato's Dialogue, Apology (38a).

2 William S. Jamison, ‘Is the Unexamined Life Worth Living?' Available at http://afwsj.uaa.alaska.edu/un.htm , visited on 20/02/2011

4 Robert Gerzon, ‘Is the unexamined life worth living?’ Available at http://www.gerzon.com/resources/unexam_life.html , visited on 20/02/2011.

7 Jamison, ‘Is the Unexamined Life Worth Living?’.

8 See Bellah , Robert N. , ‘Community Properly Understood: A Defense of “Democratic Communitarianism” in Etzioni , Amitai , (ed.), The Essential Communitarian Reader ( New York : Rowman & LittleField Publisher , 1998 ), pp. 15 – 19 Google Scholar .

9 See Waismann , Friedrich , ‘How I See Philosophy’, in Lewis , H.D. (ed.), Contemporary British Philosophy , Third Series ( London : George Allen and Unwin Ltd , 1956 ) Google Scholar .

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 11, Issue 31

- J.O. Famakinwa

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1477175612000073

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

24/7 writing help on your phone

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

An Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living Meaning Essay

Save to my list

Remove from my list

Introduction

Socrates' perception of unexamined life is not worth living.

The Difference Between Existence and Living

Life is worth living if you are aware of your flaws, finding reason to live an unexamined life.

An Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living Meaning Essay. (2024, Feb 02). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/an-unexamined-life-is-not-worth-living-meaning-essay-essay

"An Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living Meaning Essay." StudyMoose , 2 Feb 2024, https://studymoose.com/an-unexamined-life-is-not-worth-living-meaning-essay-essay

StudyMoose. (2024). An Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living Meaning Essay . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/an-unexamined-life-is-not-worth-living-meaning-essay-essay [Accessed: 14 Sep. 2024]

"An Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living Meaning Essay." StudyMoose, Feb 02, 2024. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://studymoose.com/an-unexamined-life-is-not-worth-living-meaning-essay-essay

"An Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living Meaning Essay," StudyMoose , 02-Feb-2024. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/an-unexamined-life-is-not-worth-living-meaning-essay-essay. [Accessed: 14-Sep-2024]

StudyMoose. (2024). An Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living Meaning Essay . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/an-unexamined-life-is-not-worth-living-meaning-essay-essay [Accessed: 14-Sep-2024]

- An Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living Pages: 6 (1601 words)

- Plato’s The Apology: Is The Unexamined Life Worth Living Pages: 4 (905 words)