007811702x

2012 Ideal for any Cultural Anthropology course, this brief and inexpensive collection of ethnographic case studies exposes students to fifteen different cultures. Culture Sketches introduces students to ethnography without overwhelming them with excessive reading material. Each sketch, or chapter, was selected for its relevance to students and for its ability to reflect the basic concepts found in introductory courses. All sketches follow a logical, consistent organization that makes it easy for students to understand major themes such as geography, myth creation, history, sociopolitical systems, and belief systems. The new edition offers a new chapter, "The Roma: , Rights, and the Road Ahead", adding geographic breadth to the text.

| |

| | | To obtain an instructor login for this Online Learning Center, ask your . If you're an instructor thinking about adopting this textbook, for review. | | |

and .

is one of the many fine businesses of . |

- Current Issue

- Join the SCA

SCA WebsiteSubmission guidelines, ( con traducción al español ). Cultural Anthropology publishes ethnographic writing informed by a wide array of theoretical perspectives, innovative in form and content, and focused on both traditional and emerging topics. It also welcomes essays concerned with ethnographic methods and research design in historical perspective, and with ways cultural analysis can address broader public audiences and interests. Research ArticlesA research article submitted to Cultural Anthropology should: - Be more than a solid ethnographic case study; we are looking for works that draw on original field research, or historical evidence considered anthropologically, to make explicit contributions to contemporary conversations and theoretical developments in cultural anthropology.

- Consider the extent to which citations engage with a demographically diverse set of authors, both as appropriate to the case study, and as generative of fresh theoretical insights that are productive of a more ethical, decolonized, and counterhegemonic discipline. Many fields of classic and contemporary cultural anthropology (e.g, the study of kinship, household, ritual, environments, and colonialism) have rich and complex genealogies that have not been adequately recognized in Anglophone scholarship. Works published in Cultural Anthropology should make an effort to engage with the diverse canon that has constituted these fields. Citing and engaging the work of scholars from the country and region where the research was conducted, as well as other scholars who have worked in that region (including non-English language publications), are also relevant criteria of evaluation.

- Engage and cite research beyond the author’s core networks. We especially welcome works that take alternative analyses seriously into account.

- Build arguments with claims that are proportionate to the data presented.

- Speak relevantly and reflexively to issues of research ethics, design, and methodology.

- Include an informative title and abstract that are concise and clear, which introduce the theoretical and empirical dimensions of the article and which are written with minimal jargon for a broad anthropological audience.

Cultural Anthropology welcomes multimedia content as part of regular article submissions. In addition to images, submissions may include video and/or audio clips that are integral to the text’s argumentation. Cultural Anthropology does not publish special issues or book reviews. Submitting a Research ArticleThe journal’s online submission system is the only acceptable means of submitting a manuscript for review . Manuscripts sent directly to the editors will not be considered. If you encounter any technical difficulties, please contact [email protected] for assistance. The target length of your initial submission should be 9,000 words, including notes and references . Manuscripts over 9,500 words will be returned for further editing. All submissions must include an abstract of no more than 150 words, as well as 5–7 keywords. Manuscripts submitted to Cultural Anthropology should not be under simultaneous consideration by any other journal or have been published elsewhere. When submitting a revised manuscript, please log in to your account at journal.culanth.org , where you will see your original submission. In the Review tab, you will see a box labeled Revisions; click on Upload File. Please also upload a cover letter of no more than two pages in which you explain your revision strategy and outline the major changes you have made to the text. The cover letter may be shared with reviewers, so it should not contain any identifying information. If your title or abstract changes during revisions, please click on the Publication tab to update them. Our editorial office will be automatically notified when you upload revised files, but please reach out to [email protected] if you have any questions. Short-Form EssaysColloquy is a section of Cultural Anthropology that features guest-edited collections of 3–5 short-form essays (roughly 2,000 words each) that are engaged in debate, development, and productive conversation with one another over a shared theme or concept. Colloquy contributions should be theoretically ambitious and informed by field research, but they need not be ethnographic essays. We welcome efforts to expand the conceptual and methodological horizons of anthropological practice. Submitting a Colloquy CollectionIf you are interested in proposing a Colloquy collection, please send a paragraph outlining how you propose to approach your theme to [email protected]. You should include a list of 3–5 confirmed or interested participants, including names, affiliations, essay titles, and a paragraph-long abstract for each participant’s essay. If your proposal is accepted, you will be asked to gather, edit, and introduce the collection, for a total word count of no more than 12,000 words (including endnotes and excluding references, although these should be kept to a minimum), to submit for review as a single document through the journal’s online submission system . The collection will be sent out for peer review, so author names should appear only in the cover letter. Article Processing and Submission ChargesCultural Anthropology does not use article processing charges (APCs) to support the cost of publication. Members of the Society for Cultural Anthropology (SCA) support the journal through their membership dues. Authors who are members of the American Anthropological Association (AAA), but not of the SCA, must join the SCA before their manuscripts will be reviewed. Authors who are not members of the AAA may pay a submission fee of $25 in lieu of becoming a member of the AAA and SCA. Authors can pay the fee with a credit card (MasterCard, Visa, or American Express) using the AAA’s secure payment system ; select the option “Manuscript Processing Fee - SCA Nonmember.” The editorial office will be notified once the charge has been paid and will proceed with the review of your manuscript. Submission charges only apply to initial submissions; no charge applies to resubmitted manuscripts. In the case of coauthored manuscripts, as long as at least one of the authors is a current SCA member, no submission fee will apply. Moreover, if payment of the submission fee would represent a significant financial hardship for the author, a request for a waiver with a brief explanation may be sent to [email protected] . Cultural Anthropology follows the Chicago Manual of Style (17th ed., 2017) for most matters of style, including hyphenation, capitalization, punctuation, abbreviations, and grammar, and Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (11th ed., 2003) for spelling. Manuscripts must be double-spaced and in a 12-point font, preferably Times New Roman; this applies to block quotes and excerpts, notes, and references. Margins throughout the manuscript should be set at 1 inch. Citations and reference lists should use Chicago ’s author-date format . Sources appearing in the references list must be cited in text and vice versa. In text, references are cited in parentheses, with last name(s), year of publication, and page numbers for direct quotations. The references list should be ordered alphabetically by author’s last name. If possible, please provide digital object identifier (DOIs) for all journal articles. Cultural Anthropology takes plagiarism very seriously, and asks authors to be sure that they have properly acknowledged the scholarly work of others. Failure to do so can be considered grounds for the rejection of a submitted article. Images should not be embedded in your manuscript, but uploaded separately. In the manuscript, please indicate where you would like each image to appear by adding in-text callouts between paragraphs: for example, “<IMAGE 1 HERE>.” Then, once you have uploaded the manuscript to OJS, you should upload the images and a Word document with captions for each image as supplementary files.  Our Review ProcessAll manuscripts are given an initial review by the editorial collective within 7–10 days of their submission. At that point, the editors will either inform the author that the article has been declined or will initiate the journal’s double-blind peer review process. Each article sent out for review is sent to two or three reviewers, who are selected by the journal’s editorial board and are asked to disclose any conflicts of interest before accepting the assignment. A decision about whether to accept, reject, or invite revisions to the article is generally made within three months of sending it out for review. Authors should prepare their manuscripts in order to facilitate anonymous review. Any identifying references to the author should be removed prior to submission. Our Production ProcessOnce an article has been accepted and scheduled for publication, it will be copyedited for clarity and consistency with Cultural Anthropology ’s house style. Authors will have the opportunity to review the copyedited manuscript and to make additional changes, in consultation with the managing editor. Once an article has been typeset, only very small corrections will be permitted. Authors are expected to respond promptly to all inquiries from the editorial office in order to avoid delays in the production schedule. As of 2023, Cultural Anthropology will be published under a CC BY-NC 4.0 license , meaning all CA authors will retain their copyright and the published version of the article is freely available to download, save, reproduce, and transmit for noncommercial, scholarly, and educational purposes under the Creative Commons BY-NC 4.0 license. Cultural Anthropology requires authors to provide the journal with their ORCID identifier early in the production process. Amendments and RetractionsIf an author discovers a significant error or inaccuracy in their article after it has been published, it is the author’s obligation to notify the editorial collective and to cooperate fully if an amendment or retraction is judged to be in order. In the event that an allegation of research misconduct relating to a published article is brought to the editorial collective, the journal will follow the guidelines of the Committee on Publication Ethics in responding to the allegation. Directrices para la Presentación de Originales a Cultural AnthropologyCultural Anthropology publica textos etnográficos inspirados en un amplio abanico de perspectivas teóricas, innovadores en forma y contenido, y centrados en temas tanto tradicionales como emergentes. De igual modo damos la bienvenida a contribuciones que pongan el acento en los métodos etnográficos y el diseño de la investigación desde una perspectiva histórica, a la par que propuestas de análisis cultural que busquen la interpelación e interés de públicos y audiencias más amplias. Artículos de InvestigaciónUn artículo de investigación enviado a Cultural Anthropology debe: - Ser algo más que un sólido estudio de caso etnográfico. Buscamos trabajos basados en investigaciones de campo originales, o en análisis de materiales históricos desde una perspectiva antropológica, que contribuyan explícitamente a los debates y desarrollos teóricos de la antropología cultural contemporánea.

- Hacerse cargo de que toda cita académica pone en juego un conjunto de autores y autoras demográficamente diverso, tanto en lo que respecta al estudio de caso en cuestión, como en su apuesta por una visión teórica disciplinar más ética, descolonizada y contrahegemónica. Muchos campos de la antropología cultural clásica y contemporánea (por ejemplo, el estudio del parentesco, el hogar, el ritual, el paisaje o el colonialismo) tienen genealogías ricas y complejas no siempre reconocidas adecuadamente en la tradición anglófona. Los trabajos publicados en Cultural Anthropology deberían hacer un esfuerzo por comprometerse con la diversidad canónica que ha constituido estos campos. Por ello, citar y dialogar con el trabajo de la academia del país y la región donde se ha realizado la investigación, así como de otras personas que han trabajado en esa misma región –incluidas las publicaciones en lengua no inglesa–, son criterios relevantes de evaluación.

- Establecer un diálogo y citar investigaciones cuyas contribuciones orbiten más allá de las redes académicas de les autores. Nos interesan especialmente aquellos trabajos que se toman con seriedad análisis y propuestas alternativas.

- Desarrollar una propuesta argumentativa cuyas afirmaciones guarden proporción con los datos presentados.

- Interpelar reflexivamente la propia ética, diseño y metodología de la investigación.

- Incluir un título y un resumen informativos que sean concisos y claros, que presenten las dimensiones teóricas y empíricas del artículo y estén escritos con un mínimo de jerga para un público antropológico amplio. Deberán incluirse copias en castellano y en inglés tanto del título como del resumen.

Cultural Anthropology acepta contenidos multimedia como parte de los trabajos propuestos. Además de imágenes, estos pueden incluir vídeos y/o clips de audio que formen parte de la argumentación del texto. Cultural Anthropology no publica números especiales ni reseñas de libros. Envío de un Artículo de InvestigaciónEl sistema de envío en línea de la revista es el único medio aceptable para enviar un manuscrito para su revisión. Los manuscritos enviados directamente al colectivo editorial no serán considerados. Si tiene algún problema técnico, póngase en contacto con [email protected] para obtener ayuda. Los originales enviados tendrán una extensión inicial de 9.000 palabras, incluidas las notas y bibliografía. Los manuscritos de más de 9.500 palabras se devolverán para su revisión. Todos los envíos deben incluir un resumen de no más de 150 palabras, así como de 5 a 7 palabras clave. Los manuscritos enviados a Cultural Anthropology no deben de estar siendo considerados para su publicación por ninguna otra revista, ni haber sido publicados en otro lugar. Para enviar una nueva versión de su manuscrito que responda a las recomendaciones de la revisión por pares debe acceder a su cuenta en journal.culanth.org, donde podrá ver también su envío original. En la pestaña Review (Revisión) verá una casilla denominada Revisions (Revisiones); podrá subir la nueva versión del texto haciendo clic en Upload File (Subir Fichero). Debe subir también una carta de presentación de no más de dos páginas en la que explique su estrategia de revisión y describa los principales cambios que ha realizado en el texto. La carta de presentación puede ser compartida con les revisores, por lo que no debe contener ninguna información que pueda servir para identificarle como autor o autora. Si el título o el resumen cambian durante las revisiones, haga clic en la pestaña Publication (Publicación) para actualizarlos. Nuestra oficina editorial recibirá una notificación automática cuando suba los archivos revisados, pero le rogamos que se ponga en contacto con [email protected] si tiene alguna duda. Gastos de Procesamiento y Envío de ArtículosCultural Anthropology no realiza cargos por el procesamiento de artículos (APCs) para financiar el costo de la publicación. Los socios y socias de la Society for Cultural Anthropology (SCA) subvencionan la revista a través de sus cuotas. Los autores y autoras que sean socias de la Asociación Americana de Antropología (AAA), pero no de la SCA, deben unirse a la SCA antes de que sus manuscritos sean revisados. Les autores que no sean socias de la AAA pueden pagar una cuota de envío de 25 dólares en lugar de asociarse a la AAA y la SCA. La cuota se puede pagar con una tarjeta de crédito (MasterCard, Visa o American Express) utilizando el sistema de pago seguro de la AAA, para lo cual debe seleccionar la opción "Manuscript Processing Fee - SCA Nonmember" (Tasa de Procesamiento de Manuscritos-SCA No socias). La oficina editorial será notificada una vez que se haya pagado el cargo y procederá a la revisión de su manuscrito. Los cargos por envío sólo se aplican a los envíos iniciales; no se aplica ningún cargo a los manuscritos reenviados. En el caso de manuscritos en coautoría, siempre que al menos uno de les autores sea socia de la SCA no se aplicará ninguna tasa de envío. Además, si el pago de la tasa de envío representara una dificultad financiera importante para un autor o autora, puede enviarse una solicitud de exención con una breve explicación a [email protected]. Cultural Anthropology se adhiere al Manual de Estilo de Chicago (17ª ed., 2017) para la mayoría de las cuestiones de estilo, incluyendo guiones, puntuación y abreviaturas. Los manuscritos deben ir a doble espacio y con un tipo de letra de 12 puntos, preferiblemente Times New Roman; esto se aplica a las citas en bloque y a los extractos, notas y referencias. Los márgenes de todo el manuscrito deben ser de 1 pulgada (2.54 centímetros). Cultural Anthropology recomienda el uso de lenguaje inclusivo y no sexista en los textos que se presenten para publicación. Conscientes de que no todos los textos se muestran igualmente viables para su adaptación, confiamos en el cuidado del contenido más allá de soluciones morfológicas. Valgan como ejemplo estas mismas directrices, donde hemos optado por usar distintos pronombres y formas del sujeto (a veces “autores y autoras”, a veces “les autores”) buscando tanto la inclusividad como la accesibilidad, y ofreciendo una alternativa morfológica para personas con dificultades lecto-escritoras. BibliografíaLas citas y bibliografías deben utilizar el formato autor-fecha de Chicago. Las fuentes que aparecen en la bibliografía deben citarse en el texto y viceversa. En el texto, las referencias se citan entre paréntesis, con los apellidos, el año de publicación y los números de página de las citas directas. La bibliografía debe estar ordenada alfabéticamente por el apellido del autor o autora. Si es posible, facilite el identificador de objeto digital (DOI) de todos los artículos de revistas citados. Debido al esfuerzo editorial que conlleva la apuesta por la publicación de textos en castellano en Cultural Anthropology sólo podemos comprometernos a publicar aquellos textos cuyas autoras o autores se hagan cargo del cumplimiento estricto de las normas de estilo y formato de la revista. No hacerlo será considerado motivo de rechazo del trabajo. Cultural Anthropology se toma muy en serio el plagio y pide a les autores que se aseguren de haber reconocido adecuadamente el trabajo académico de otras personas. No hacerlo puede ser considerado motivo de rechazo de un trabajo. Las imágenes no deben estar integradas en el manuscrito, sino que deben enviarse por separado. En el manuscrito, indique dónde desea que aparezca cada imagen añadiendo llamadas en el texto entre los párrafos: por ejemplo, "<IMÁGEN 1 AQUÍ>". Después, una vez que haya subido el manuscrito a OJS, deberá subir las imágenes y un documento de Word con los pies de foto de cada imagen como archivos complementarios. Nuestro Proceso de RevisiónTodos los manuscritos son sometidos a una revisión inicial por parte del colectivo editorial en un plazo de 7 a 10 días desde su recepción. En ese momento, les editores informarán al autor o autora si el artículo es rechazado o iniciarán el proceso de revisión por el sistema de pares ciegos. Los artículos se enviarán a dos o tres revisores, que son seleccionados por el consejo editorial de la revista y a quienes se les solicita que declaren cualquier conflicto de intereses antes de aceptar el encargo. La decisión de aceptar, rechazar o invitar a revisar el artículo se toma generalmente en los tres meses siguientes al envío de la revisión. Les autores deben preparar sus manuscritos para facilitar la revisión anónima. Cualquier referencia que les identifique debe ser eliminada antes de su envío. Nuestro Proceso de ProducciónUna vez que un artículo ha sido aceptado y programado para su publicación será revisado para cerciorarse de que se adhiere a las normas de estilo y formato de Cultural Anthropology . De no ser así, en consulta con el colectivo editorial los autores y autoras tendrán la oportunidad de revisar el manuscrito y hacer los cambios de estilo y formato necesarios para adecuarse a las normas de la revista. Una vez que el artículo haya sido maquetado, sólo se permitirán correcciones mínimas. Se espera que les autores respondan con prontitud a todas las consultas de la redacción para evitar retrasos en el calendario de producción. A partir de 2023, Cultural Anthropology se publicará bajo una licencia CC BY-NC 4.0 , lo que significa que todas las y los autores de CA conservarán sus derechos de autor y que la versión publicada del artículo se podrá descargar, guardar, reproducir y transmitir libremente para fines no comerciales, académicos y educativos bajo la licencia Creative Commons BY-NC 4.0. Enmiendas y RetractacionesSi une autor o autora descubre un error o inexactitud importante en su artículo tras su publicación, es su obligación notificarlo al colectivo editorial y cooperar plenamente si llegara a ser necesario enmendarlo o retractarlo. En caso de que el colectivo editorial reciba una acusación de mala conducta durante la realización de una investigación relacionada con un artículo publicado en la revista, el colectivo seguirá las directrices del Comité sobre la Ética de Publicar (Committee on Publication Ethics, COPE) para responder a la acusación. Begin typing to search.Showing results mentioning: “ ”, our journal.  - History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

Definition and scopeDistinction between physical anthropology and cultural anthropology. - Evolutionism

- Marxism and the collectors

- Boas and the culture history school

- Mauss and the “sociological” school

- The “grand diffusionists”

- Functionalism and structuralism

- Cultural psychology

- Neo-Marxism and neo-evolutionism

- The new research and fieldwork

- Non-Western cultural anthropologists

- Applied studies

cultural anthropologyOur editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article. - Discover Anthropology - Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Table Of Contents

cultural anthropology , a major division of anthropology that deals with the study of culture in all of its aspects and that uses the methods, concepts, and data of archaeology , ethnography and ethnology, folklore, and linguistics in its descriptions and analyses of the diverse peoples of the world. Etymologically, anthropology is the science of humans. In fact, however, it is only one of the sciences of humans, bringing together those disciplines the common aims of which are to describe human beings and explain them on the basis of the biological and cultural characteristics of the populations among which they are distributed and to emphasize, through time, the differences and variations of these populations. The concept of race, on the one hand, and that of culture , on the other, have received special attention; and although their meaning is still subject to debate, these terms are doubtless the most common of those in the anthropologist’s vocabulary. Anthropology, which is concerned with the study of human differences, was born after the Age of Discovery had opened up societies that had remained outside the technological civilization of the modern West. In fact, the field of research was at first restricted to those societies that had been given one unsatisfactory label after another: “savage,” “primitive,” “tribal,” “traditional,” or even “preliterate,” “prehistorical,” and so on. What such societies had in common, above all, was being the most “different” or the most foreign to the anthropologist; and in the early phases of anthropology, the anthropologists were always European or North American. The distance between the researcher and the object of his study has been a characteristic of anthropological research; it has been said of the anthropologist that he was the “astronomer of the sciences of man.” Anthropologists today study more than just primitive societies. Their research extends not only to village communities within modern societies but also to cities, even to industrial enterprises. Nevertheless, anthropology’s first field of research, and the one that perhaps remains the most important, shaped its specific point of view with regard to the other sciences of man and defined its theme. If, in particular, it is concerned with generalizing about patterns of human behaviour seen in all their dimensions and with achieving a total description of social and cultural phenomena, this is because anthropology has observed small-scale societies, which are simpler or at least more homogeneous than modern societies and which change at a slower pace. Thus they are easier to see whole. What has just been said refers especially to the branch of anthropology concerned with the cultural characteristics of man. Anthropology has, in fact, gradually divided itself into two major spheres: the study of man’s biological characteristics and the study of his cultural characteristics. The reasons for this split are manifold, one being the rejection of the initial mistakes regarding correlations between race and culture. More generally speaking, the vast field of 19th-century anthropology was subdivided into a series of increasingly specialized disciplines, using their own methods and techniques, that were given different labels according to national traditions. Thus two large disciplines—physical anthropology and cultural anthropology—and such related disciplines as prehistory and linguistics now cover the program that originally was set up for a single study of anthropology. The two fields are largely autonomous , having their own relations with disciplines outside anthropology; and it is unlikely that any researchers today work simultaneously in the fields of physical and cultural anthropology. The generalist has become rare. On the other hand, the fields have not been cut off from one another. Specialists in the two fields still cooperate in specific genetic or demographic problems and other matters.  Prehistoric archaeology and linguistics also have notable links with cultural anthropology. In posing the problem of the evolution of mankind in an inductive way, archaeology contributed to the creation of the first concepts of anthropology, and archaeology is still indispensable in uncovering the past of societies under observation. In many areas, when it is a question of interpreting the use of rudimentary tools or of certain elementary religious phenomena, prehistory and cultural anthropology are mutually helpful. “Primitive” societies that have not yet reached the metal age are still in existence. Relations between linguistics and cultural anthropology are numerous. On a purely practical level the cultural anthropologist has to serve a linguistic apprenticeship. He cannot do without a knowledge of the language of the people he is studying, and often he has had to make the first survey of it. One of his essential tasks, moreover, has been to collect the various forms of oral expression, including myths , folk tales, proverbs, and so forth. On the theoretical level, cultural anthropology has often used concepts developed in the field of linguistics: in studying society as a system of communication, in defining the notion of structure, and in analyzing the way in which man organizes and classifies his whole experience of the world. Cultural anthropology maintains relations with a great number of other sciences. It has been said of sociology , for instance, that it was almost the twin sister of anthropology. The two are presumably differentiated by their field of study (modern societies versus traditional societies). But the contrast is forced. These two social sciences often meet. Thus, the study of colonial societies borrows as much from sociology as from cultural anthropology. And it has already been remarked how cultural anthropology intervenes more and more frequently in urban and industrial fields classically the domain of sociology. There have also been fruitful exchanges with other disciplines quite distinct from cultural anthropology. In political science the discussion of the concept of the state and of its origin has been nourished by cultural anthropology. Economists, too, have depended on cultural anthropology to see concepts in a more comparative light and even to challenge the very notion of an “economic man” (suspiciously similar to the 19th-century capitalist revered by the classical economists). Cultural anthropology has brought to psychology new bases on which to reflect on concepts of personality and the formation of personality. It has permitted psychology to develop a system of cross-cultural psychiatry, or so-called ethnopsychiatry . Conversely, the psychological sciences, particularly psychoanalysis, have offered cultural anthropology new hypotheses for an interpretation of the concept of culture. The link with history has long been a vital one because cultural anthropology was originally based on an evolutionist point of view and because it has striven to reconstruct the cultural history of societies about which, for lack of written documents, no historical record could be determined. Cultural anthropology has more recently suggested to historians new techniques of research based on the analysis and criticism of oral tradition . And so “ ethnohistory ” is beginning to emerge. Finally, cultural anthropology has close links with human geography . Both of them place great importance on man either as he uses space or acts to transform the natural environment . It is not without significance that some early anthropologists were originally geographers. We’re fighting to restore access to 500,000+ books in court this week. Join us! Internet Archive Audio - This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet. Mobile Apps- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser ExtensionsArchive-it subscription. - Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page NowCapture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future. Please enter a valid web address - Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Culture sketches : case studies in anthropologyBookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for. - Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png) plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews1,060 Views 49 Favorites DOWNLOAD OPTIONSNo suitable files to display here. IN COLLECTIONSUploaded by station15.cebu on December 14, 2021 An Introduction to Cultural AnthropologyStudying people and cultures around the world Kryssia Campos/Getty Images - Archaeology

- Ph.D., Sociocultural Anthropology, the University of Texas at Austin

- M.A., Social Sciences, University of Chicago

- B.A., Sociology and Anthropology, Carleton College

Cultural anthropology, also known as sociocultural anthropology , is the study of cultures around the world. It is one of four subfields of the academic discipline of anthropology . While anthropology is the study of human diversity, cultural anthropology focuses on cultural systems, beliefs, practices, and expressions. Did You Know?Cultural anthropology is one of the four subfields of anthropology. The other subfields are archaeology, physical (or biological) anthropology, and linguistic anthropology. Areas of Study and Research QuestionsCultural anthropologists use anthropological theories and methods to study culture. They study a wide variety of topics, including identity, religion, kinship, art, race, gender, class, immigration, diaspora, sexuality, globalization, social movements, and many more. Regardless of their specific topic of study, however, cultural anthropologists focus on patterns and systems of belief, social organization, and cultural practice. Some of the research questions considered by cultural anthropologists include: - How do different cultures understand universal aspects of the human experience, and how are these understandings expressed?

- How do understandings of gender, race, sexuality, and disability vary across cultural groups?

- What cultural phenomena emerge when different groups come into contact, such as through migration and globalization?

- How do systems of kinship and family vary among different cultures?

- How do various groups distinguish between taboo practices and mainstream norms?

- How do different cultures use ritual to mark transitions and life stages?

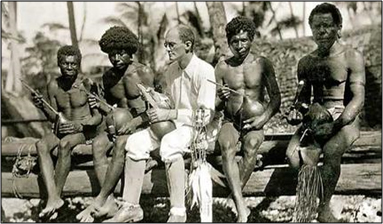

History and Key FiguresCultural anthropology’s roots date back to the 1800s, when early scholars like Lewis Henry Morgan and Edward Tylor became interested in the comparative study of cultural systems. This generation drew on the theories of Charles Darwin , attempting to apply his concept of evolution to human culture. They were later dismissed as so-called “armchair anthropologists,” since they based their ideas on data collected by others and did not personally engage first-hand with the groups they claimed to study. These ideas were later refuted by Franz Boas, who is widely hailed as the father of anthropology in the U.S. Boas strongly denounced the armchair anthropologists’ belief in cultural evolution, arguing instead that all cultures had to be considered on their own terms and not as part of a progress model. An expert in the indigenous cultures of the Pacific Northwest, where he participated in expeditions, he taught what would become the first generation of American anthropologists as a professor at Columbia University. His students included Margaret Mead , Alfred Kroeber, Zora Neale Hurston , and Ruth Benedict. Boas’ influence continues in cultural anthropology’s focus on race and, more broadly, identity as forces that are social constructed and not biologically based. Boas fought staunchly against the ideas of scientific racism that were popular in his day, such as phrenology and eugenics. Instead, he attributed differences between racial and ethnic groups to social factors. After Boas, anthropology departments became the norm in U.S. colleges and universities, and cultural anthropology was a central aspect of study. Students of Boas went on to establish anthropology departments across the country, including Melville Herskovits, who launched the program at Northwestern University, and Alfred Kroeber, the first professor of anthropology at the University of California at Berkeley. Margaret Mead went on to become internationally famous, both as an anthropologist and scholar. The field grew in popularity in the U.S. and elsewhere, giving way to new generations of highly influential anthropologists like Claude Lévi-Strauss and Clifford Geertz. Together, these early leaders in cultural anthropology helped solidify a discipline focused explicitly on the comparative study of world cultures. Their work was animated by a commitment to true understanding of different systems of beliefs, practice, and social organization. As a field of scholarship, anthropology was committed to the concept of cultural relativism , which held that all cultures were fundamentally equal and simply needed to be analyzed according to their own norms and values. The main professional organization for cultural anthropologists in North America is the Society for Cultural Anthropology , which publishes the journal Cultural Anthropology . Ethnographic research, also known as ethnography , is the primary method used by cultural anthropologists. The hallmark component of ethnography is participant observation, an approach often attributed to Bronislaw Malinowski. Malinowski was one of the most influential early anthropologists, and he pre-dated Boas and the early American anthropologists of the 20th century. For Malinowski, the anthropologist’s task is to focus on the details of everyday life. This necessitated living within the community being studied—known as the fieldsite—and fully immersing oneself in the local context, culture, and practices. According to Malinowski, the anthropologist gains data by both participating and observing, hence the term participant observation. Malinowski formulated this methodology during his early research in the Trobriand Islands and continued to develop and implement it throughout his career. The methods were subsequently adopted by Boas and, later, Boas’ students. This methodology became one of the defining characteristics of contemporary cultural anthropology. Contemporary Issues in Cultural AnthropologyWhile the traditional image of cultural anthropologists involves researchers studying remote communities in faraway lands, the reality is far more varied. Cultural anthropologists in the twenty-first century conduct research in all types of settings, and can potentially work anywhere that humans live. Some even specialize in digital (or online) worlds, adapting ethnographic methods for today’s virtual domains. Anthropologists conduct fieldwork all around the world, some even in their home countries. Many cultural anthropologists remain committed to the discipline’s history of examining power, inequality, and social organization. Contemporary research topics include the influence of historical patterns of migration and colonialism on cultural expression (e.g. art or music) and the role of art in challenging the status quo and effecting social change. Where Do Cultural Anthropologists Work?Cultural anthropologists are trained to examine patterns in daily life, which is a useful skill in a wide range of professions. Accordingly, cultural anthropologists work in a variety of fields. Some are researchers and professors in universities, whether in anthropology departments or other disciplines like ethnic studies, women’s studies, disability studies, or social work. Others work in technology companies, where there is an increasing demand for experts in the field of user experience research. Additional common possibilities for anthropologists include nonprofits, market research, consulting, or government jobs. With broad training in qualitative methods and data analysis, cultural anthropologists bring a unique and diverse skill set to a variety of fields. - McGranahan, Carol. "On Training Anthropologists Rather Than Professors" Dialogs, Cultural Anthropology website, 2018.

- " Social and Cultural Anthropology " Discover Anthropology UK, The Royal Anthropological Institute, 2018 .

- " What is Anthropology? " American Anthropological Association , 2018.

- An Introduction to Medical Anthropology

- An Introduction to Visual Anthropology

- Anthropology vs. Sociology: What's the Difference?

- Franz Boas, Father of American Anthropology

- What Is Ethnomusicology? Definition, History, and Methods

- Anthropology Defined

- Biography of Claude Lévi-Strauss, Anthropologist and Social Scientist

- Career Options for Archaeology Degrees

- Is Anthropology a Science?

- Ethnoarchaeology: Blending Cultural Anthropology and Archaeology

- Processual Archaeology

- Definition of Cultural Materialism

- Cultural Ecology

- What Is Structural Violence?

- Introduction to the Lapita Cultural Complex

- The Culture-Historical Approach: Social Evolution and Archaeology