How Capitalism Actually Generates More Inequality

Why extending markets or increasing competition won’t reduce inequality.

By Geoffrey M. Hodgson

At least nominally, capitalism embodies and sustains an Enlightenment agenda of freedom and equality. Typically there is freedom to trade and equality under the law, meaning that most adults – rich or poor – are formally subject to the same legal rules. But with its inequalities of power and wealth, capitalism nurtures economic inequality alongside equality under the law.

Today, in the USA, the richest 1 per cent own 34 per cent of the wealth and the richest 10 per cent own 74 per cent of the wealth. In the UK, the richest 1 per cent own 12 per cent of the wealth and the richest 10 per cent own 44 per cent of the wealth. In France the figures are 24 cent and 62 per cent respectively. The richest 1 percent own 35 percent of the wealth in Switzerland, 24 per cent in Sweden and 15 percent in Canada. Although there are important variations, other developed countries show similar patterns of inequality within this range. [1]

Get Evonomics in your inbox

In their book The Spirit Level, Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett showed multiple deleterious effects of inequalities of income and wealth. Using data from twenty-three developed countries and from the separate states of the United States, they observed negative correlations between inequality, on the one hand, and physical health, mental health, education, child well-being, social mobility, trust and community life, on the other hand. They also found positive correlations between inequality and drug abuse, imprisonment, obesity, violence, and teenage pregnancies. They suggested that inequality creates adverse outcomes through psycho-social stresses generated through interactions in an unequal society.

Although economic inequality is endemic to capitalism, data gathered by Thomas Piketty in his Capital in the Twentieth Century , and in my book entitled Conceptualizing Capitalism , show that there are large variations in measures of inequality in different major capitalist countries, and through time. The existence of such variety within capitalism suggests that it possible to alleviate inequality, to a significant degree, within capitalism itself.

But first we must be clear about the drivers of inequality within the system. What are the mechanisms within capitalism that exacerbate inequalities of income or wealth?

Some inequality results from individual differences in talent or skill. But this cannot explain the huge gaps between rich and poor in many capitalist countries. Much of the inequality of wealth found within capitalist societies results from inequalities of inheritance. The process is cumulative: inequalities of wealth often lead to differences in education, economic power, and further inequalities in income. [2]

Do markets create inequality?

To what extent can inequalities of income or wealth be attributed to the fundamental institutions of capitalism, rather than a residual landed aristocracy, or other surviving elites from the pre-capitalist past? A familiar mantra is that markets are the source of inequality under capitalism. Can markets be blamed for inequality?

In real-world markets different sellers or buyers vary hugely in their capacities to influence prices and other outcomes. When a seller has sufficient saleable assets to affect market prices, then strategic market behaviour is possible to drive out competitors.

Would more competition, with greater numbers of market participants, fix this problem? If markets per se are to be blamed for inequality, then it has to be shown that competitive markets also have this outcome. Unless we can demonstrate their culpability, blaming competitive markets for inequalities of success or failure might be like blaming the water for drowning a weak swimmer.

To demonstrate that competitive markets are a source of inequality we would have to start from an imagined world where there was initial equality in the distribution of income and wealth, and then show how markets led to inequality. I know of no such theoretical explanation.

Markets involve voluntary exchange, where both parties to an exchange expect benefits. One party to the exchange may benefit more than the other; but there is no reason to assume that individuals who benefit more, or benefit less (in one exchange) will generally do so. And if some traders become more powerful in the market than others, then its competitiveness is reduced.

There is another reason why it is a mistake to focus on markets. In the sense of organized arenas of exchange, markets have existed for thousands of years. We need to look at new institutional drivers of inequality that became prominent in the last 400 years or so. These new institutional changes were additional to markets.

The sources of inequality within capitalism

So if markets per se are not the root cause of inequality under capitalism, then what is? A clear answer to this question is vital if effective policies to counter inequality are to be developed. Capitalism builds on historically-inherited inequalities of class, ethnicity, and gender. By affording more opportunities for the generation of profits, it may also exaggerate differences due to location or ability. Partly through the operation of markets, it can also enhance positive feedbacks that further magnify these differences. But its core sources of inequality lie elsewhere.

Because waged employees are not slaves, they cannot use their lifetime capacity for work as collateral to obtain money loans. The very commercial freedom of workers denies them the possibility to use their labour assets or skills as collateral. By contrast, capitalists may use their property to make profits, and as collateral to borrow money, invest and make still more money. Differences become cumulative, between those with and without collateralizable assets, and between different amounts of collateralizable wealth. Even when workers become home-owners with mortgages, the wealthier can still race ahead.

Unlike owned capital, free labour power cannot be used as collateral to obtain loans for investment. At least in this respect, capital and labour do not meet on a level playing field, this asymmetry is a major driver of inequality.

The foremost generator of inequality under capitalism is not markets but capital . This may sound Marxist, but it is not. In my Conceptualizing Capitalism I define capital differently from Marx and from most other economists and sociologists. My definition of capital corresponds to its enduring and commonplace business meaning. (Piketty’s definition is also similar to mine.) Capital is money, or the realizable money-value of collateralizable property . Unlike labour, capital can be used as collateral and the loan obtained can help generate further wealth.

Because workers are free to change jobs, employers have diminished incentives to invest in the skills of their workforce. Especially as capitalism becomes more knowledge-intensive, this can create an unskilled and low-paid underclass and further exacerbate inequality, unless compensatory measures are put in place. A socially-excluded underclass is observable in several developed capitalist countries.

Another source of inequality results from the inseparability of the worker from the work itself. By contrast, the owners of other factors of production are free to trade and seek other opportunities while their property makes money or yields other rewards. This puts workers at a disadvantage. Through positive feedbacks, even slight disadvantages can have cumulative effects.

None of these core drivers of inequality can be diminished by extending markets or increasing competition. These drivers are congenital to capitalism and its system of wage labour. If capitalism is to be retained, then the compensatory arrangements that are needed to counter inequality cannot simply be extensions of markets or private property rights.

These ineradicable asymmetries between labour and capital mean that ultra-individualist arguments against trade unions are misconceived. In a system that is biased against them, workers have a right to organize and defend their rights, even if it reduces competition in labour markets.

Reducing inequality – within capitalism

The twentieth-century socialist experiments in Russia and China undermined human rights in their efforts to reduce inequality. This is not a road that we should attempt to follow.

Instead, we have to look at ways of reducing inequality within capitalism, and which do not undermine capitalism’s unparalleled capacity to increase productivity and generate wealth.

Long ago, Thomas Paine (1737-1809) argued for an inheritance tax, but balanced this by a grant to each adult at reaching the age of maturity. In this way, wealth would be recycled from the dead to the young, providing greater equality of opportunity across the board. Paine also advocated welfare provision and a guaranteed pension for those over 50.

Bruce Ackerman and Anne Alstott took up Paine’s agenda in their proposal for a ‘stakeholder society.’ They argued that ‘property is so important to the free development of individual personality that everybody ought to have some’. They echoed Francis Bacon: ‘Wealth is like muck. It is not good but if it be spread.’

Ackerman and Alstott stressed progressive taxes on wealth rather than on income. Echoing Paine, they proposed a large cash grant to all citizens when they reach the age of majority, around the benchmark cost of taking a bachelor’s degree at private university in the United States. This grant would be repaid into the national treasury at death. To further advance redistribution, they argued for the gradual implementation of an annual wealth tax of two percent on a person’s net worth above a threshold of $80,000. Like Paine, they argued that every citizen has the right to share in the wealth accumulated by preceding generations. A redistribution of wealth, they proposed, would bolster the sense of community and common citizenship.

Increased wealth or inheritance taxes are likely to be unpopular because they are perceived as an attack on the wealth that we have built up and wish to pass on to our children or others of our choice. But the brilliance of Paine’s 1797 proposal for a cash grant at the age of majority is that it offers a quid-pro-quo for wealth or inheritance taxes at later life.

People will be more ready to accept wealth taxation if they have earlier benefitted from a large cash grant in their youth. Wealth would by recycled to younger generations rather than syphoned away. The more fortunate or successful can be persuaded to give up some of their advantages if they see the benefits for society as a whole.

In the economy, there are many ways of spreading power and influence more broadly. The idea of extending employee shareholding is growing in popularity. This is a flexible strategy for extending ownership of revenue-producing assets in society. In the USA alone, over ten thousand enterprises, employing over ten million workers, are part of employee-ownership, stock bonus, or profit-sharing schemes. Employee ownership can increase incentives, personal identification with the enterprise, and job satisfaction for workers.

As modern capitalist economies become more knowledge-intensive, access to education to develop skills becomes all the more important. Those deprived of such education suffer a degree of social exclusion, and, unless it is addressed, this problem is likely to get worse. Widespread skill-development policies are needed, alongside integrated measures to deal with job displacement and unemployment.

A key challenge for modern capitalist societies, alongside the needs to protect the natural environment and enhance the quality of life, is to retain the dynamic of innovation and investment while ensuring that the rewards of the global system are not returned largely to the richer owners of capital. As Paine put it in 1797:

All accumulation, therefore, of personal property, beyond what a man’s own hands produce, is derived to him by living in society; and he owes on every principle of justice, of gratitude, and of civilization, a part of that accumulation from whence the whole came.

We need to update Paine’s approach to dealing with inequality, to suit modern times.

[1] Data are for 2010 and from the Credit Suisse Research Institute (2012). See also Piketty (2014) for extensive data on inequality.

[2] See Bowles and Gindis (2002) and Credit Suisse Research Institute (2012). See Ackerman and Alstott, (1999) and Atkinson (2015) on policies to reduce inequality.

2016 August 11

Donating = Changing Economics. And Changing the World.

Evonomics is free, it’s a labor of love, and it's an expense. We spend hundreds of hours and lots of dollars each month creating, curating, and promoting content that drives the next evolution of economics. If you're like us — if you think there’s a key leverage point here for making the world a better place — please consider donating. We’ll use your donation to deliver even more game-changing content, and to spread the word about that content to influential thinkers far and wide.

MONTHLY DONATION $3 / month $7 / month $10 / month $25 / month

If you liked this article, you'll also like these other Evonomics articles...

Be involved.

We welcome you to take part in the next evolution of economics. Sign up now to be kept in the loop!

- Contributors

The future of economics is here! Be a part of the conversation by getting the latest in your inbox.

Photo by Harry Gruyaert/Magnum

The great wealth wave

The tide has turned – evidence shows ordinary citizens in the western world are now richer and more equal than ever before.

by Daniel Waldenström + BIO

Recent decades have seen private wealth multiply around the Western world, making us richer than ever before. A hasty glance at the soaring number of billionaires – some doubling as international celebrities – prompts the question: are we also living in a time of unparalleled wealth inequality? Influential scholars have argued that indeed we are. Their narrative of a new gilded age paints wealth as an instrument of power and inequality. The 19th-century era with low taxes and minimal market regulation allowed for unchecked capital accumulation and then, in the 20th century, the two world wars and progressive taxation policies diminished the fortunes of the wealthy and reduced wealth gaps. Since 1980, the orthodoxy continues, a wave of market-friendly policies reversed this equalising historical trend, boosting capital values and sending wealth inequality back towards historic highs.

The trouble with the powerful new orthodoxy that tries to explain the history of wealth is that it doesn’t fully square with reality. New research studies, and more careful inspection of the previous historical data, paint a picture where the main catalysts for wealth equalisation are neither the devastations of war nor progressive tax regimes. War and progressive taxation have had influence, but they cannot count as the main forces that led to wealth inequality falling dramatically over the past century. The real influences are instead the expansion from below of asset ownership among everyday citizens, constituted by the rise of homeownership and pension savings. This popular ownership movement was made possible by institutional changes, most important democracy, and followed suit by educational reforms and labour laws, and the technological advancements lifting everyone’s income. As a result, workers became more productive and better paid, which allowed them to get mortgages to purchase their own homes; homeownership rates soared in the West from the middle of the century. As standards of living improved, life spans increased so that people started saving for retirement, accumulating another important popular asset.

Today, the populations of Europe and the United States are substantially richer in terms of real purchasing-power wealth than ever before. We define wealth as the value of all assets, such as homes, bank deposits, stocks and pension funds, less all debts, mainly mortgages. When counting wealth among all adults, data show that its value has increased more than threefold since 1980, and nearly 10 times over the past century. Since much of this wealth growth has occurred in the types of assets that ordinary people hold – homes and pension savings – wealth has also become more equally distributed over time. Wealth inequality has decreased dramatically over the past century and, despite the recent years’ emergence of super-rich entrepreneurs, wealth concentration has remained at its historically low levels in Europe and has increased mainly in the US.

Among scholars in economics and economic history, a new narrative is just beginning to emerge, one that accentuates this massive rise of middle-class ownership and its implications for society’s total capital stock and its distribution. Capitalism, it seems, did not result in boundless inequality, even after the liberalisations of the 1980s and corporate growth in the globalised era. The key to progress, measured as a combination of wealth growth and falling or sustained inequality, has been political and institutional change that enabled citizens to become educated, better paid, and to amass wealth through housing and pension savings.

I n his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2014), Thomas Piketty examined the long-run evolution of capital and wealth inequality since industrialisation in a few Western economies. The book quickly received wide acclaim among both academics and policymakers, and it even became a worldwide bestseller.

Piketty’s narrative outlined wealth accumulation and concentration as following a U-shaped pattern over the past century. At the time of the outbreak of the First World War, wealth levels and inequality peaked as a result of an unregulated capitalism, low taxation or democratic influence. During the 20th century, wartime capital destruction and postwar progressive taxes slashed wealth among the rich and equalised ownership. Since 1980, however, goes Piketty’s narrative, neoliberal policies have boosted capital values and wealth inequality towards historic levels.

Immediately after publication, Capital generated fierce debate among economists, focused primarily on the book’s theoretical underpinnings. For example, Piketty had sketched a couple of ‘fundamental laws’ of capitalism, defining the economic importance of aggregate wealth. The first law stated that the share of capital income in total income (the other share coming from labour) is a function of how much capital there is in the economy and its rate of return to capital owners. The second law stated that the amount of capital in the economy, measured as its share in total output, is determined by the balance between saving to accumulate capital and income growth. While these laws were actually fairly uncontroversial relationships, almost definitions, they laid out a mechanistic view of inequality trends that attracted considerable attention and scrutiny among Piketty’s fellow theoretical economists.

My work arrives at a striking new conclusion for the history of wealth and inequality in the West

However, what the academic debate cared less about was the empirical side of the analysis. Almost nothing was said about the historical data and the empirical conclusions underlying the claims about U-shaped patterns and main driving forces. The void in critical scrutiny exposed a widespread disinterest among mainstream economists in history and the fine-grained aspects of source materials, measurement and institutional contexts.

In recent years, a new strand of historical wealth inequality research has emerged from universities around the world. It offers a more nuanced empirical picture, including new data and revised evidence, pointing to different results and interpretations. In Piketty’s book, most of the analysis centred on the historical experiences of France, and then there was additional evidence presented for the United Kingdom and Germany (together making up Europe) and the US. Newer work reexamines and extends the historical wealth accumulation and inequality trends. Some of these contributions also revise the earlier data series, such as those analysing Germany and the UK. Other studies expand the empirical base by incorporating previously unexplored countries, such as Spain and Sweden. A number of ongoing research projects into the history of wealth distribution examine more new countries, including Switzerland, the Netherlands and Canada. Their findings will soon be added to this historical wealth database.

My work with new data, published in my book Richer and More Equal (2024), arrives at a new conclusion for the history of wealth and inequality in the West. The new results are striking. Data show that we are both richer and more equal today than we were in the past. An accumulation of housing wealth and pension savings among workers in the middle classes emerges as the main factor producing greater equality: today, three-fourths of all private assets are either homes or long-term pension and insurance savings.

U nderlying the change in personal wealth formation over the 20th century are a number of political and economic developments. The democratisation of the Western world began with the extension of universal suffrage during the 1910s. This movement initiated a process of reforming the educational system, to extend basic schooling to the population and facilitating access to higher education. New labour laws improved working life by restricting the working hours per day, allowing unions to be active. Better training and nicer workplaces raised worker productivity and earnings, creating opportunity for working- and middle-class households to purchase their own homes. The improved living standards also led to longer lives. Between the 1940s and today, life expectancy at birth increased by almost 20 years in Western countries, most of which were spent in retirement. Pension systems started evolving during the postwar era, both as public-sector unfunded systems based on promises about a future income, and as private-sector funded systems where individual pension funds were accumulated as part of people’s long-term saving.

At the core of the new findings are three empirical observations.

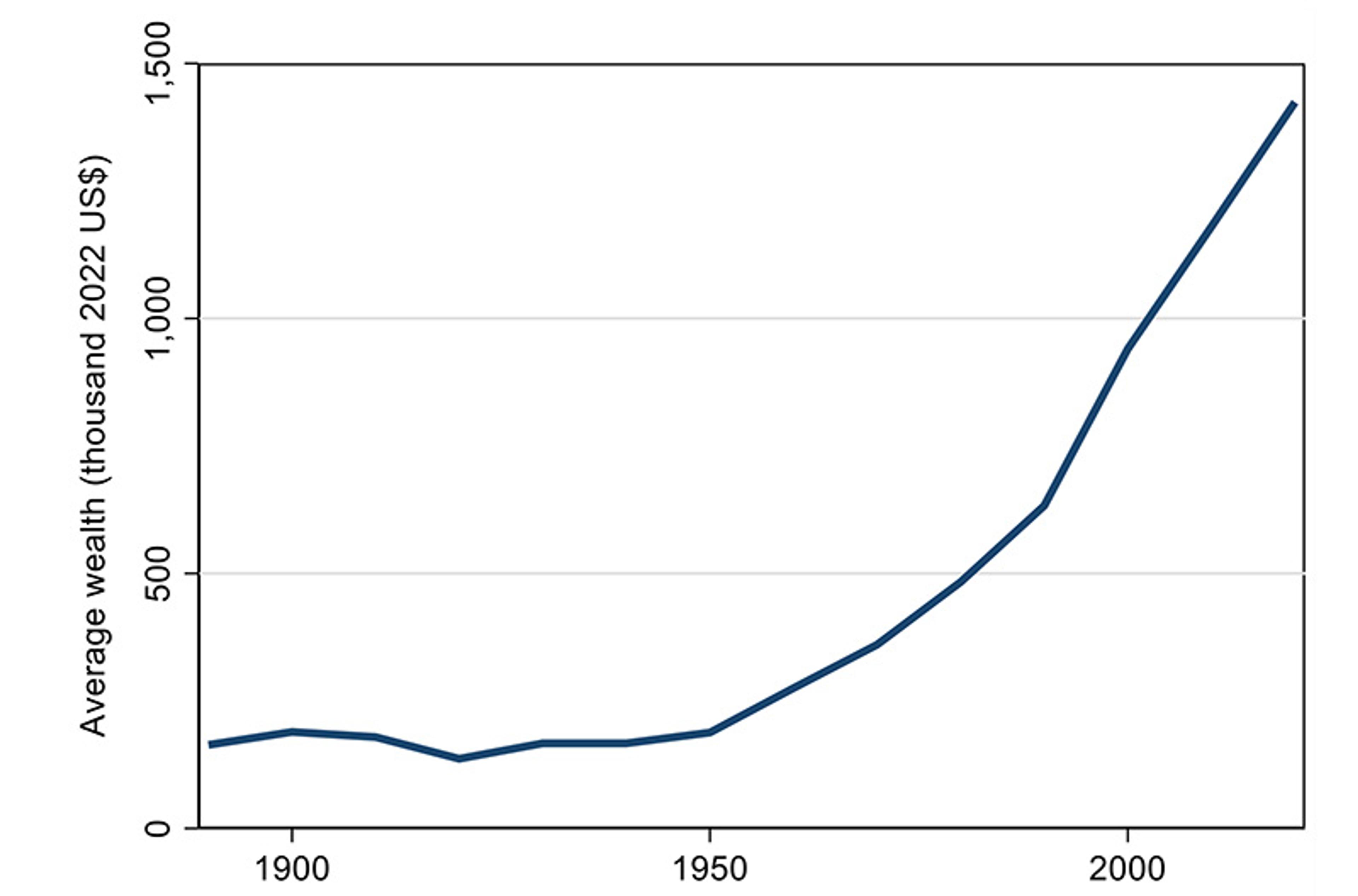

The first is that the populations in Western countries are richer today than ever before in history. By rich, again, I mean having a high level of average wealth in the adult population. Why this measure of riches captures relevant aspects of welfare is because higher wealth permits a lot of good things in life. It allows for higher consumption, more savings and larger investment for future prosperity. It also promises better insurance against unforeseen events. Figure 1 below illustrates the growth in the average real per-capita wealth in a selection of Western countries over the past 130 years. It is dramatic. During the first half of the past century, the average wealth in the Western population hovered at a stable level. Since the end of the Second World War, asset values started to increase, doubling the level in only a couple of decades. From 1950 to 2020, average wealth in the West increased sevenfold.

Over the past 130 years, a monumental shift in wealth composition has taken place

A fact to notice specifically is how wealth has grown each single postwar decade up to the present day. For several reasons, this consistency of growth is a marvel. It affirms the robustness of the result: we are wealthier today than in history, and this fact does not depend on the choice of start or end date but holds regardless of the time period considered. The steady increase in wealth is not confined to investment-driven growth in Europe’s early postwar decades. Neither does it hinge on the market liberalisations of the 1980s and ’90s. However, it is notable how the lifting of regulations and the historically high taxes since the 1980s are indeed associated with the highest pace of value-creation that the Western world has ever experienced.

Figure 1: rising real average wealth in the Western world. Note: wealth is expressed in real terms, meaning that it is adjusted for the rise in consumer prices and thus expresses change in purchasing power. The line is an unweighted mean of the average wealth in the adult population in six countries (France, Germany, Spain, Sweden, the UK and the US) expressed in constant 2022 US dollars. Source: Waldenström (2024, Chapter 2)

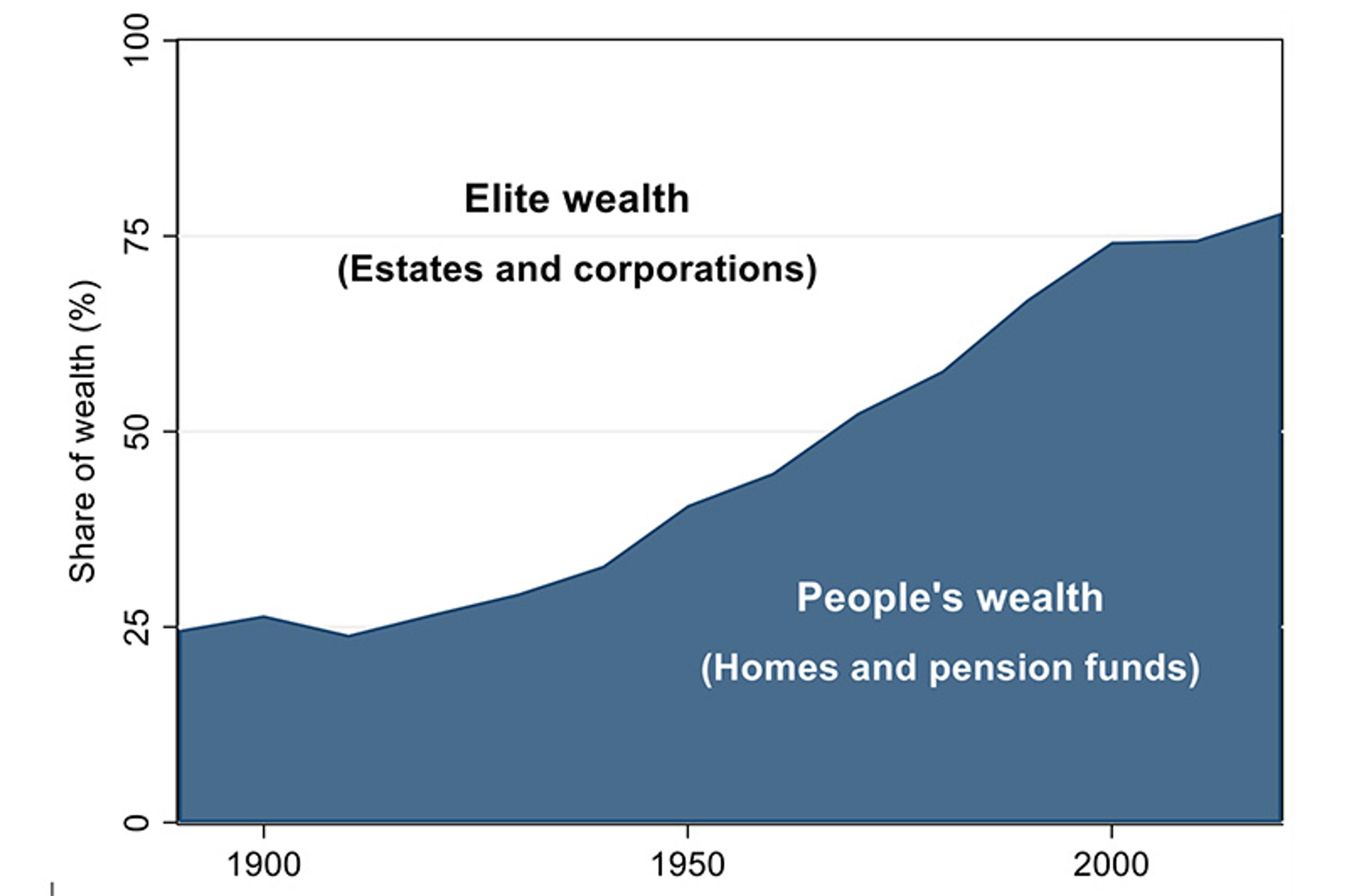

A second fact coming out of the historical evidence is that wealth in the aggregate has changed in its appearance. The composition of assets people hold tells us about the economic structure of society and what functions wealth plays in the population. For example, whether most assets are tied to the agricultural economy or to industrial activities signifies the degree of economic modernisation in the historical analysis. The importance of ordinary people’s assets in the aggregate signifies the degree to which workers take part in the value-creation processes of the market economy. Figure 2 below displays the division across asset classes in the aggregate portfolio since the end of the 19th century. It is evident that, over the past 130 years, a monumental shift in wealth composition has taken place. A century ago, wealth comprised primarily agricultural land and industrial capital. Today, the majority of personal wealth is tied up in housing and pension funds.

Figure 2: the aggregate composition of assets: from elite wealth to people’s wealth . Note: unweighted average of six countries (France, Germany, Spain, Sweden, the UK and the US). Source: Waldenström (2024, Chapter 3)

The transformation of wealth composition has strong distributional implications. Individual ownership data, often called microdata, show how ownership structures across wealth distribution bear a pattern of who owns what. Historically, the rich held agricultural estates and shares in industrial corporations. This is especially true over the long term of history, but it remains so now too. In contrast, the working population acquires wealth in their homes and long-term savings in pension funds. Homeownership rates today range from 50 to 80 per cent. Labor-force participation rates are even higher. In substance, this tells us that housing and work-related pension funds are assets that dominate the ownership of ordinary people in the lower and middle classes, which in turn links the relative aggregate importance of housing and pension funds for wealth inequality.

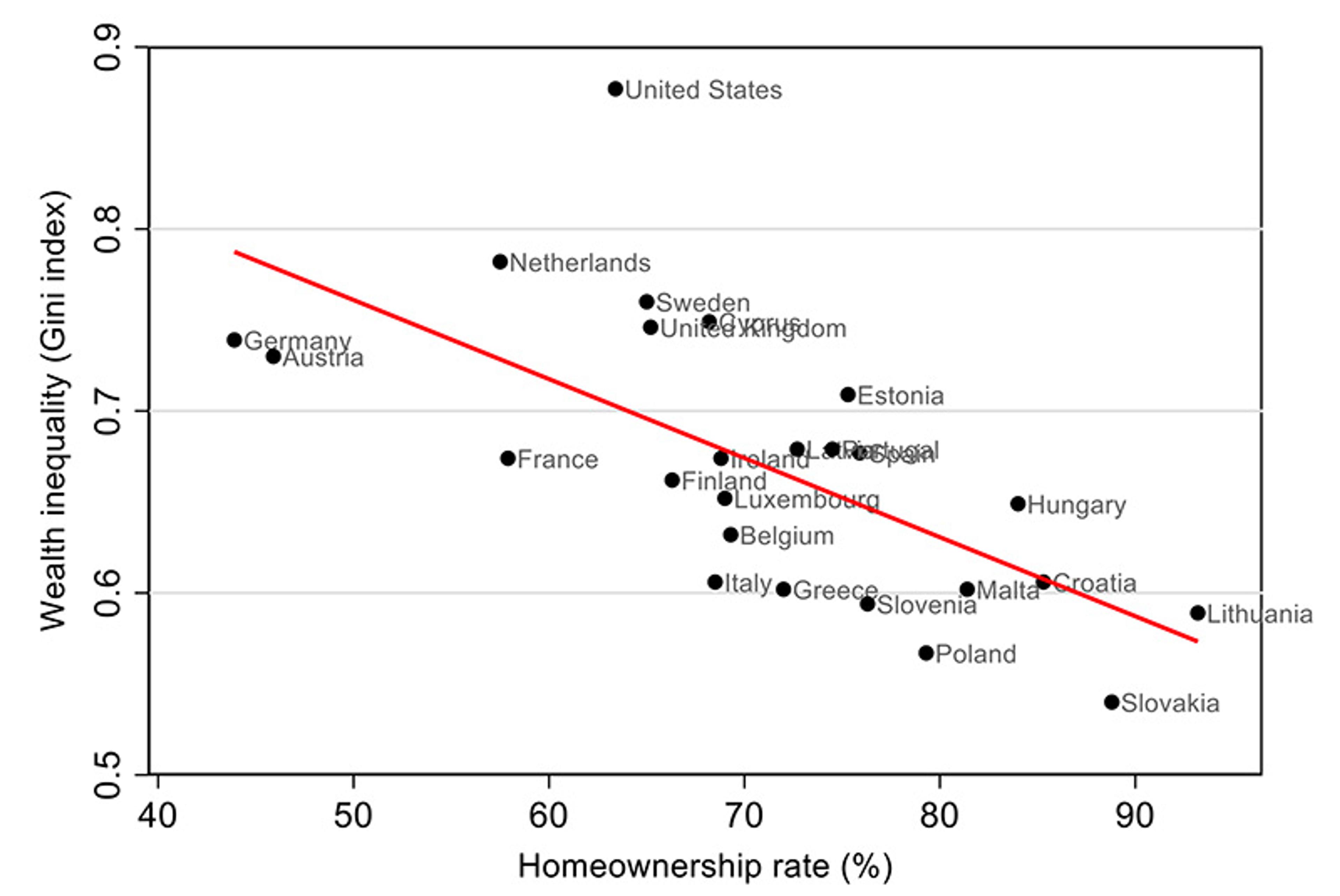

L ooking closer at the relationship between the share of a country’s citizens who own their homes and the level of wealth inequality, the distributional pattern becomes evident. Figure 3 below plots countries according to their homeownership rates and wealth inequality, as measured by the common Gini coefficient that ranges from 0 (no inequality) to 1 (one individual owns everything), using recent wealth and homeownership surveys. Countries with higher levels of homeownership have lower wealth inequality. The straight line in the figure has a negative slope, which suggests that raising the homeownership rate by 10 points leads to an expected reduction in wealth inequality by 0.04 Gini points. As an example, France has a lower homeownership than Italy ( 60 per cent compared with 70 per cent), and a higher wealth inequality (0.67 versus Italy’s 0.61).

Figure 3: homeownership and wealth inequality in Europe and the US. Source: Waldenström (2024, Chapter 6)

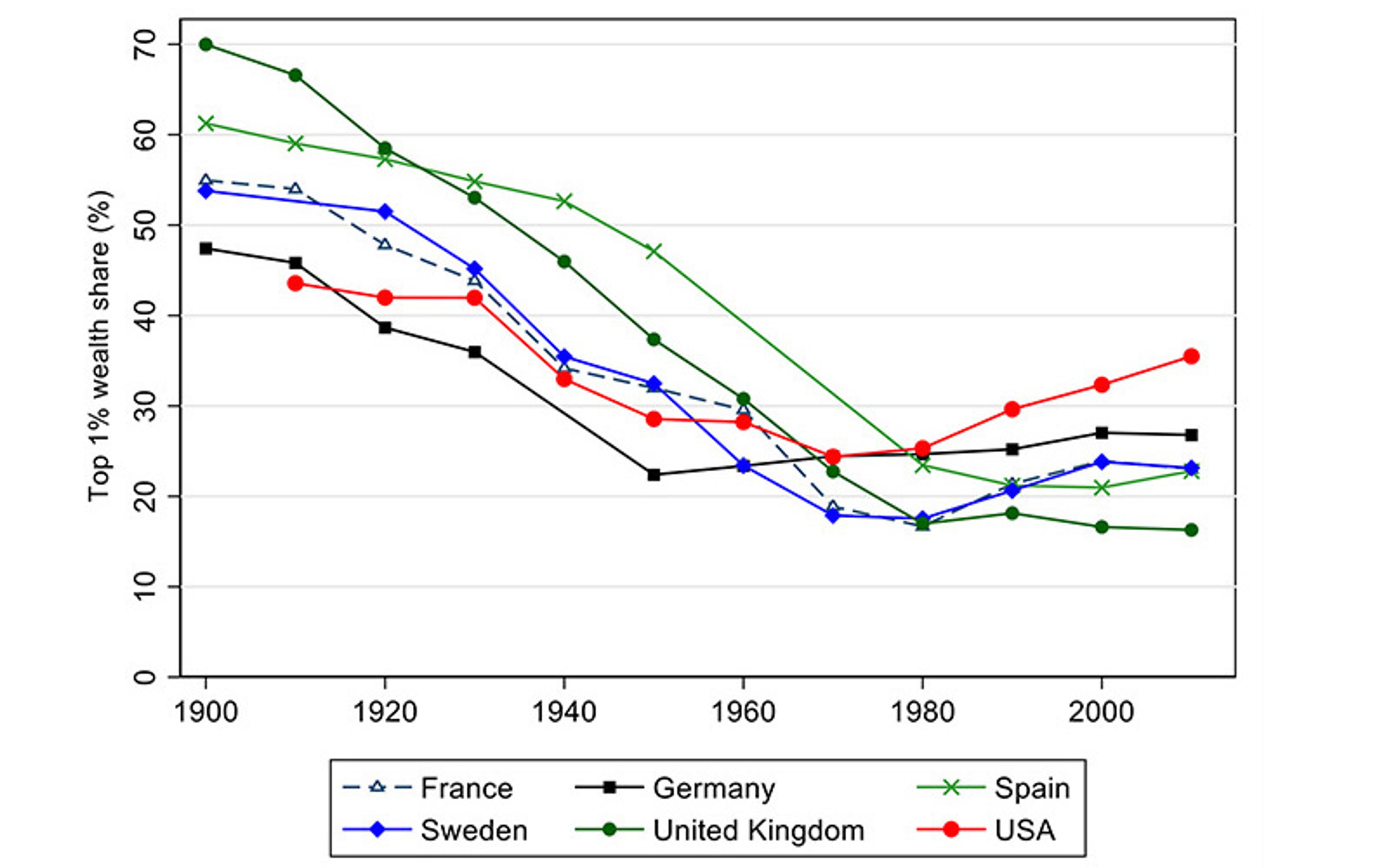

The historical shift in the nature of wealth, from being elite-centric to more democratic, can thus be expected to have profound implications for the distribution of wealth. Figure 4 below presents the most recent data from European countries and the US. They reveal in graphical form how wealth inequality has decreased substantially over the past century. The wealthiest percentile once held around 60 per cent of all wealth. The share ranged from 50 per cent of wealth in the US and Germany to 70 per cent in the UK.

Most wealth today is in homes and pensions, assets predominantly of low- and middle-wealth households

Since the first half of the 20th century, the tide has turned. A great wealth equalisation took place throughout the Western world. From the 1920s to the 1970s, wealth concentration fell steadily. In the 1970s, wealth equalisation stopped, but then Europe and the US follow separate paths. In Europe, top wealth shares stabilise at historically low levels, perhaps with a slight increasing tendency. As of 2010, the richest 1 per cent in society holds a share of total wealth at around 20 per cent in Europe. That is roughly one-third of its share of national wealth from a century earlier. Countries like the UK, the Netherlands, Italy and Finland have top percentile shares of around 16-18 per cent. A bit higher are countries like Spain, Denmark, Norway and Sweden with top shares at around 21-24 per cent. Germany has an even higher share, around 27 per cent, and Switzerland’s richest percentile group owns about 30 per cent of all wealth.

This stability of post-1970 top wealth shares may seem contradictory when contrasted with the large increases in aggregate wealth values over recent decades. However, it is consistent with most of the asset ownership patterns documented above, with most of wealth today being in housing and pensions, assets predominantly held by low- and middle-wealth households.

The US wealth concentration experience is somewhat different. Wealth inequality in the beginning of the 20th century was somewhat lower in the US than in most European countries, perhaps reflecting being a younger nation with less established elite structures. The equalisation trend also happened in the US, but it was less pronounced than in Europe. Today, US wealth concentration is currently much higher than in Europe. This situation, as the figure below shows, is the result of several years of steady increase. In historical perspective, however, even the current US level of wealth inequality is lower than it was before the Second World War, and it pales in comparison with the extreme levels of wealth concentration that the people of Europe experienced 100 years ago.

Figure 4: the great wealth equalisation over the 20th century. Source: Waldenström (2024, Chapter 5)

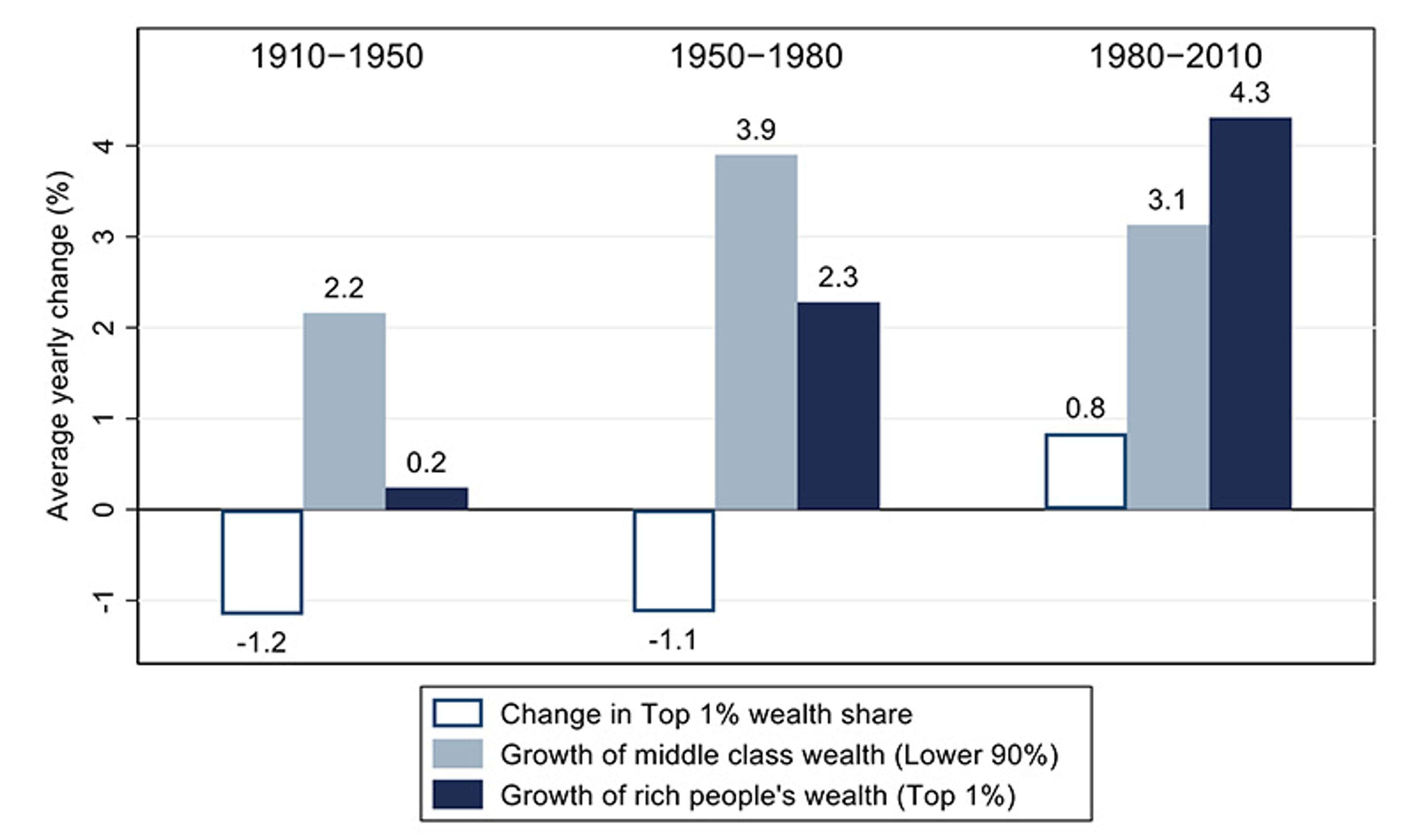

H ow can we account for these historical trends showing a steady growth in average household wealth and, at the same time, wealth inequality falling to historically low levels, where it has remained in Europe but has risen lately in the US? One approach is to break down the top wealth shares into the accumulation of wealth in the top and bottom groups of the distribution. In other words, we decompose the change in top wealth shares by documenting the changes in absolute wealth holdings in the numerator and denominator of the top wealth-share ratio. Figure 5 below shows these numbers, and they are striking.

During no historical time period during the past century did the wealth amounts of the rich fall on average. The falling wealth concentration from 1910 to 1980 was instead the result of wealth accumulating faster in the middle classes than in the top. Since 1950, wealth holdings have actually grown in the entire population. Between 1950 and 1980, it grew faster among the lower groups in the wealth distribution, explaining the continued equalisation. After 1980, wealth has instead grown faster in the top percentile than in the lower classes, which accounts for the halt of the long equalisation trend and a slight upward trend in the top wealth share, driven by the US development, whereas the European countries remained at its historically low levels.

Figure 5: Western wealth growth: the middle class vs the rich. The graph shows a six-country average (France, Germany, Spain, Sweden, the UK, the US) of the average annual growth rate of real (inflation-adjusted) net wealth per adult individual in the top 1 per cent and the lower 90 per cent of the wealth distribution during three time periods. Source: Waldenström (2024, Chapter 6)

Looking at the specific factors that could account for these trends in wealth growth and wealth inequality, there are some that match the evidence better than others. According to the orthodox narrative, the main explanation was the shocks to capital during the world wars and postwar capital taxes, all of which are believed to have created equality through lowering the top of the wealth distribution. In this telling, the physical capital destruction in wars reduced the fortunes of the rich, and the immediate postwar hikes in capital taxes and market regulations, such as price controls and capital market restrictions, prevented the entrepreneurs from rebuilding their wealth.

Wealth and inheritance taxes reached almost confiscatory levels in the early 1970s

However, the thesis has some issues. One is that the evidence shows little difference between belligerent and non-belligerent countries. During both wars, the wealth share of the top 1 per cent fell equally in belligerent countries like France and the UK as in non-belligerent Sweden. Including the immediate postwar years, which were heavily influenced by wartime turbulence, does not change this pattern. Germany’s data from the wars is less clear, but it appears that the country experienced larger losses than others, reducing top wealth shares. Spain, which stayed out of both world wars but fought a civil war in the 1930s, saw the wealth share of the richest 1 per cent remain virtually unchanged between 1936 and 1939, according to preliminary estimates. Looking at the US, top wealth shares fell during both wars.

Analysing instead the changes in absolute wealth held by the rich and by the rest reinforces the conclusion that wars were not a devastating moment for capital owners. In fact, the fortunes of the elite did not shrink significantly, except in France during the First World War and seemingly in Germany during both wars. In other cases, the capital values of the rich remained almost constant, and the wealth equalisation observed can be attributed to growing ownership among groups below the top tier.

Progressive tax policies after the Second World War offer another potential explanation for the wealth-equalisation trend. Capital taxation increased rapidly between the 1950s and the 1980s in most Western countries. Wealth and inheritance taxes reached almost confiscatory levels in the early 1970s, and this coincided with stagnating business activities, few startups, slowed economic growth, and an exodus of prominent entrepreneurs from high- to low-tax countries. Few studies have been able to analyse systematically the extent to which these taxes prevented the rise of new large fortunes, but studies of later periods suggest that there are good grounds to believe they did.

A general problem for the factors above – which focus on shocks to the capital of the rich and thus lowering the top of wealth distribution as the primus motor behind the great wealth equalisation of the 20th century – is that the evidence presented in Figure 5 above shows that it was instead the lifting of the bottom of the distribution that accounted for the equalisation. Let us therefore shift focus and examine the two main channels through which this happened: the accumulation of homeownership and saving for retirement.

At the turn of the 20th century, owning a decent home and saving for retirement were luxuries enjoyed by only a select few – maybe a couple of tens of millions in Western countries. Today, the once-elusive dreams of home ownership and pensions have become a reality for several hundreds of millions of people. Homeownership rates went from 20-40 per cent in the first half of the former century to 50-80 per cent in the modern era. Retirement savings also increased in the postwar period, reflecting the longer life spans that came with the general improvement of living standards. Funded pensions and other insurance savings comprised 5-10 per cent of household portfolios around 1950, but this share increased to 20-40 per cent in the 2000s.

The most crucial equalisation resulted from expanded wealth ownership among ordinary citizens

History demonstrates that the significant wealth equalisation over the past century was primarily driven by a massive increase in homeownership and retirement savings. But what initiated this accumulation of assets by households? The most comprehensive evidence highlights the role of political changes and economic developments that explicitly included new groups in the productive market economy. Firstly, the 1910s and ’20s witnessed a broad wave of political democratisation, extending universal suffrage to the Western world. Following this regime shift, a series of reforms transformed the economic reality for the masses. Educational attainment was expanded, and higher education became accessible to broader segments of society. New labour laws improved workers’ rights, making workplaces safer and reducing working hours. These changes enhanced workers’ productivity and real incomes. Simultaneously, the financial system evolved by offering better services to this new constituency of potential customers, including cheaper loans, savings plans, mutual funds and other financial services.

Thus, the primary drivers behind the great wealth equalisation of the 20th century were not wars or the redistributive effects of capital taxation. While these factors had some impact, the most crucial equalisation resulted from expanded wealth ownership among ordinary citizens, particularly through homeownership and pension savings, and the institutional shifts that enabled the accumulation of these assets.

A general lesson from history is that wealth accumulation is a positive, welfare-enhancing force in free-market economies. It is closely linked to the growth of successful businesses, which leads to new jobs, higher incomes and more tax revenue for the public sector. Various historical, social and economic factors have contributed to the rise of wealth accumulation in the middle class, with homeownership and pension savings being the primary ones.

As a closing remark, it should be recognised that the story of wealth equalisation is not one of unmitigated success. There are still significant disparities in wealth within and among nations, generating instability and injustice. Over the past years, wealth concentration has increased in some countries, most notably in the US. The extent to which this is due to productive entrepreneurship generating products, jobs, incomes and taxes, or to forces that exclude groups from acquiring personal wealth causing tensions and erosive developments in society, is a question that needs to be studied more. However, at this point it is still vital to acknowledge the progress toward greater equality that has been made in our past and understand how it has happened. Only then can we be in a stronger position to lay the foundation for further advancements in our quest for a more just and prosperous world.

Political philosophy

C L R James and America

The brilliant Trinidadian thinker is remembered as an admirer of the US but he also warned of its dark political future

Harvey Neptune

Neuroscience

The melting brain

It’s not just the planet and not just our health – the impact of a warming climate extends deep into our cortical fissures

Clayton Page Aldern

Falling for suburbia

Modernists and historians alike loathed the millions of new houses built in interwar Britain. But their owners loved them

Michael Gilson

Computing and artificial intelligence

Mere imitation

Generative AI has lately set off public euphoria: the machines have learned to think! But just how intelligent is AI?

Anthropology

Your body is an archive

If human knowledge can disappear so easily, why have so many cultural practices survived without written records?

Helena Miton

Illness and disease

Empowering patient research

For far too long, medicine has ignored the valuable insights that patients have into their own diseases. It is time to listen

Charlotte Blease & Joanne Hunt

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Capitalism Has Become An Ideology In Today's America. Here's How It Happened

Rund Abdelfatah

Ramtin Arablouei

Capitalism: What Is It?

A demonstrator holds a sign reading "I love capitalism" during a protest against California's stay-at-home order in 2020. Capitalism started as an economic system; it has become an ideology in the modern United States. Robyn Beck/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

A demonstrator holds a sign reading "I love capitalism" during a protest against California's stay-at-home order in 2020. Capitalism started as an economic system; it has become an ideology in the modern United States.

The Throughline team has been thinking about capitalism a lot these days. It's hard not to when so many people are struggling just to get by.

Capitalism is an economic system, but it's also so much more than that. It's become a sort of ideology, this all-encompassing force that rules over our lives and our minds. It might seem like it's an inevitable force, but really, it's a construction project that took hundreds of years and no part of it is natural or just left to chance.

So here's what we did. First, we wanted to look at what makes American capitalism distinct, if it is even distinct ? Is it uniquely individual, uniquely efficient, uniquely cutthroat? Like, these are all the things that we've been thinking about a lot.

A young girl interacts with an employee maintaining one of tanks at New Jersey SEA LIFE Aquarium inside the American Dream mall in East Rutherford. Michael Loccisano/Getty Images hide caption

A young girl interacts with an employee maintaining one of tanks at New Jersey SEA LIFE Aquarium inside the American Dream mall in East Rutherford.

And so we brought together three REALLY DIFFERENT experts who come at these questions from REALLY DIFFERENT points of view.

Bryan Caplan's an economist and adjunct scholar at the Cato Institute, Vivek Chibber studies Marxist theory and historical sociology, and Kristen Ghodsee is an expert in what happened after the fall of communism in Russia and Eastern Europe.

And we had a conversational round of analysis that led us from colonial times, through waves of innovation and American development to the American Dream Mall in New Jersey.

We compared the happiness index in countries to see crazy things like how much happier people in Denmark report that they are, compared to Americans.

But that's not all. We wanted to dive deeper into the dominance of Capitalism in the 20th century American mindset .

What's the role of government in society? What do we mean when we talk about individual responsibility? What makes us free? 'Neoliberalism' might feel like a term that's hard to define and understand. But it's the dominant socio-economic ideology of both major American political parties — Republican and Democrats — no matter how much partisan rhetoric might be geared towards absolute division.

And this ideology, this belief in free markets, deregulation, and privatization can be traced back — pretty directly — to a group of men meeting in the Swiss Alps.

On April 10, 1947, a group of 39 economists, historians and sociologists gathered in a conference room of a posh ski resort at Mont Pelerin, Switzerland. Glasses clinked. Cigars burned. A mission statement was written.

And from that meeting, they would start an organization called The Mont Pelerin Society, MPS. The ideas discussed in that room more than 70 years ago would evolve and warp and, this is no exaggeration, come to shape the world we live in. Those ideas have dominated our economic system for decades. In the name of free market fundamentals, the forces behind neoliberalism act like an invisible hand, shaping almost every aspect of our lives.

From the TV advertisements we all grew up watching to the way the internet is understood today.

Capitalism: What Makes Us Free?

That's not all. We're also dropping a third episode on Capitalism this coming Thursday, July 8. For that episode, we explore how religion and capitalism joined forces to change the way we think about our work, our society, and ourselves — the Prosperity Gospel.

To receive it when it drops subscribe here in Apple Podcasts or wherever else you get your pods.

- All Articles

- Books & Reviews

- Anthologies

- Audio Content

- Author Directory

- This Day in History

- War in Ukraine

- Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

- Artificial Intelligence

- Climate Change

- Biden Administration

- Geopolitics

- Benjamin Netanyahu

- Vladimir Putin

- Volodymyr Zelensky

- Nationalism

- Authoritarianism

- Propaganda & Disinformation

- West Africa

- North Korea

- Middle East

- United States

- View All Regions

Article Types

- Capsule Reviews

- Review Essays

- Ask the Experts

- Reading Lists

- Newsletters

- Customer Service

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Subscriber Resources

- Group Subscriptions

- Gift a Subscription

Capitalism and Inequality

What the right and the left get wrong, by jerry z. muller.

Detail of A Social History of the State of Missouri by Thomas Hart Benton.

Recent political debate in the United States and other advanced capitalist democracies has been dominated by two issues: the rise of economic inequality and the scale of government intervention to address it. As the 2012 U.S. presidential election and the battles over the "fiscal cliff" have demonstrated, the central focus of the left today is on increasing government taxing and spending, primarily to reverse the growing stratification of society, whereas the central focus of the right is on decreasing taxing and spending, primarily to ensure economic dynamism. Each side minimizes the concerns of the other, and each seems to believe that its desired policies are sufficient to ensure prosperity and social stability. Both are wrong.

Inequality is indeed increasing almost everywhere in the postindustrial capitalist world. But despite what many on the left think, this is not the result of politics, nor is politics likely to reverse it, for the problem is more deeply rooted and intractable than generally recognized. Inequality is an inevitable product of capitalist activity, and expanding equality of opportunity only increases it—because some individuals and communities are simply better able than others to exploit the opportunities for development and advancement that capitalism affords. Despite what many on the right think, however, this is a problem for everybody, not just those who are doing poorly or those who are ideologically committed to egalitarianism—because if left unaddressed, rising inequality and economic insecurity can erode social order and generate a populist backlash against the capitalist system at large.

Over the last few centuries, the spread of capitalism has generated a phenomenal leap in human progress, leading to both previously unimaginable increases in material living standards and the unprecedented cultivation of all kinds of human potential. Capitalism's intrinsic dynamism, however, produces insecurity along with benefits, and so its advance has always met resistance. Much of the political and institutional history of capitalist societies, in fact, has been the record of attempts to ease or cushion that insecurity, and it was only the creation of the modern welfare state in the middle of the twentieth century that finally enabled capitalism and democracy to coexist in relative harmony.

In recent decades, developments in technology, finance, and international trade have generated new waves and forms of insecurity for leading capitalist economies, making life increasingly unequal and chancier for not only the lower and working classes but much of the middle class as well. The right has largely ignored the problem, while the left has sought to eliminate it through government action, regardless of the costs. Neither approach is viable in the long run. Contemporary capitalist polities need to accept that inequality and insecurity will continue to be the inevitable result of market operations and find ways to shield citizens from their consequences—while somehow still preserving the dynamism that produces capitalism's vast economic and cultural benefits in the first place.

COMMODIFICATION AND CULTIVATION

Capitalism is a system of economic and social relations marked by private property, the exchange of goods and services by free individuals, and the use of market mechanisms to control the production and distribution of those goods and services. Some of its elements have existed in human societies for ages, but it was only in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in parts of Europe and its offshoots in North America, that they all came together in force. Throughout history, most households had consumed most of the things that they produced and produced most of what they consumed. Only at this point did a majority of the population in some countries begin to buy most of the things they consumed and do so with the proceeds gained from selling most of what they produced.

The growth of market-oriented households and what came to be called "commercial society" had profound implications for practically every aspect of human activity. Prior to capitalism, life was governed by traditional institutions that subordinated the choices and destinies of individuals to various communal, political, and religious structures. These institutions kept change to a minimum, blocking people from making much progress but also protecting them from many of life's vicissitudes. The advent of capitalism gave individuals more control over and responsibility for their own lives than ever before—which proved both liberating and terrifying, allowing for both progress and regression.

Commodification—the transformation of activities performed for private use into activities performed for sale on the open market—allowed people to use their time more efficiently, specializing in producing what they were relatively good at and buying other things from other people. New forms of commerce and manufacturing used the division of labor to produce common household items cheaply and also made a range of new goods available. The result, as the historian Jan de Vries has noted, was what contemporaries called "an awakening of the appetites of the mind"—an expansion of subjective wants and a new subjective perception of needs. This ongoing expansion of wants has been chastised by critics of capitalism from Rousseau to Marcuse as imprisoning humans in a cage of unnatural desires. But it has also been praised by defenders of the market from Voltaire onward for broadening the range of human possibility. Developing and fulfilling higher wants and needs, in this view, is the essence of civilization.

Because we tend to think of commodities as tangible physical objects, we often overlook the extent to which the creation and increasingly cheap distribution of new cultural commodities have expanded what one might call the means of self-cultivation. For the history of capitalism is also the history of the extension of communication, information, and entertainment—things to think with, and about.

Among the earliest modern commodities were printed books (in the first instance, typically the Bible), and their shrinking price and increased availability were far more historically momentous than, say, the spread of the internal combustion engine. So, too, with the spread of newsprint, which made possible the newspaper and the magazine. Those gave rise, in turn, to new markets for information and to the business of gathering and distributing news. In the eighteenth century, it took months for news from India to reach London; today, it takes moments. Books and news have made possible an expansion of not only our awareness but also our imagination, our ability to empathize with others and imagine living in new ways ourselves. Capitalism and commodification have thus facilitated both humanitarianism and new forms of self-invention.

Over the last century, the means of cultivation were expanded by the invention of recorded sound, film, and television, and with the rise of the Internet and home computing, the costs of acquiring knowledge and culture have fallen dramatically. For those so inclined, the expansion of the means of cultivation makes possible an almost unimaginable enlargement of one's range of knowledge.

FAMILY MATTERS

If capitalism has opened up ever more opportunities for the development of human potential, however, not everyone has been able to take full advantage of those opportunities or progress far once they have done so. Formal or informal barriers to equality of opportunity, for example, have historically blocked various sectors of the population—such as women, minorities, and the poor—from benefiting fully from all capitalism offers. But over time, in the advanced capitalist world, those barriers have gradually been lowered or removed, so that now opportunity is more equally available than ever before. The inequality that exists today, therefore, derives less from the unequal availability of opportunity than it does from the unequal ability to exploit opportunity. And that unequal ability, in turn, stems from differences in the inherent human potential that individuals begin with and in the ways that families and communities enable and encourage that human potential to flourish.

The role of the family in shaping individuals' ability and inclination to make use of the means of cultivation that capitalism offers is hard to overstate. The household is not only a site of consumption and of biological reproduction. It is also the main setting in which children are socialized, civilized, and educated, in which habits are developed that influence their subsequent fates as people and as market actors. To use the language of contemporary economics, the family is a workshop in which human capital is produced.

Over time, the family has shaped capitalism by creating new demands for new commodities. It has also been repeatedly reshaped by capitalism because new commodities and new means of production have led family members to spend their time in new ways. As new consumer goods became available at ever-cheaper prices during the eighteenth century, families devoted more of their time to market-oriented activities, with positive effects on their ability to consume. Male wages may have actually declined at first, but the combined wages of husbands, wives, and children made higher standards of consumption possible. Economic growth and expanding cultural horizons did not improve all aspects of life for everybody, however. The fact that working-class children could earn money from an early age created incentives to neglect their education, and the unhealthiness of some of the newly available commodities (white bread, sugar, tobacco, distilled spirits) meant that rising standards of consumption did not always mean an improvement in health and longevity. And as female labor time was reallocated from the household to the market, standards of cleanliness appear to have declined, increasing the chance of disease.

The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw the gradual spread of new means of production across the economy. This was the age of the machine, characterized by the increasing substitution of inorganic sources of power (above all the steam engine) for organic sources of power (human and animal), a process that increased productivity tremendously. As opposed to in a society based largely on agriculture and cottage industries, manufacturing now increasingly took place in the factory, built around new engines that were too large, too loud, and too dirty to have a place in the home. Work was therefore more and more divorced from the household, which ultimately changed the structure of the family.

At first, the owners of the new, industrialized factories sought out women and children as employees, since they were more tractable and more easily disciplined than men. But by the second half of the nineteenth century, the average British workingman was enjoying substantial and sustained growth in real wages, and a new division of labor came about within the family itself, along lines of gender. Men, whose relative strength gave them an advantage in manufacturing, increasingly worked in factories for market wages, which were high enough to support a family. The nineteenth-century market, however, could not provide commodities that produced goods such as cleanliness, hygiene, nutritious meals, and the mindful supervision of children. Among the upper classes, these services could be provided by servants. But for most families, such services were increasingly provided by wives. This caused the rise of the breadwinner-homemaker family, with a division of labor along gender lines. Many of the improvements in health, longevity, and education from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, de Vries has argued, can be explained by this reallocation of female labor from the market to the household and, eventually, the reallocation of childhood from the market to education, as children left the work force for school.

DYNAMISM AND INSECURITY

For most of history, the prime source of human insecurity was nature. In such societies, as Marx noted, the economic system was oriented toward stability—and stagnancy. Capitalist societies, by contrast, have been oriented toward innovation and dynamism, to the creation of new knowledge, new products, and new modes of production and distribution. All of this has shifted the locus of insecurity from nature to the economy.

Hegel observed in the 1820s that for men in a commercial society based on the breadwinner-homemaker model, one's sense of self-worth and recognition by others was tied to having a job. This posed a problem, because in a dynamic capitalist market, unemployment was a distinct possibility. The division of labor created by the market meant that many workers had skills that were highly specialized and suited for only a narrow range of jobs. The market created shifting wants, and increased demand for new products meant decreased demand for older ones. Men whose lives had been devoted to their role in the production of the old products were left without a job and without the training that would allow them to find new work. And the mechanization of production also led to a loss of jobs. From its very beginnings, in other words, the creativity and innovation of industrial capitalism were shadowed by insecurity for members of the work force.

Marx and Engels sketched out capitalism's dynamism, insecurity, refinement of needs, and expansion of cultural possibilities in The Communist Manifesto :

The bourgeoisie has, through its exploitation of the world market, given a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country. To the great chagrin of reactionaries, it has drawn from under the feet of industry the national ground on which it stood. All old-established national industries have been destroyed or are daily being destroyed. They are dislodged by new industries, whose introduction becomes a life and death question for all civilized nations, by industries that no longer work up indigenous raw material, but raw material drawn from the remotest zones; industries whose products are consumed, not only at home, but in every quarter of the globe. In place of the old wants, satisfied by the production of the country, we find new wants, requiring for their satisfaction the products of distant lands and climes. In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal inter-dependence of nations.

In the twentieth century, the economist Joseph Schumpeter would expand on these points with his notion that capitalism was characterized by "creative destruction," in which new products and forms of distribution and organization displaced older forms. Unlike Marx, however, who saw the source of this dynamism in the disembodied quest of "capital" to increase (at the expense, he thought, of the working class), Schumpeter focused on the role of the entrepreneur, an innovator who introduced new commodities and discovered new markets and methods.

The dynamism and insecurity created by nineteenth-century industrial capitalism led to the creation of new institutions for the reduction of insecurity, including the limited liability corporation, to reduce investor risks; labor unions, to further worker interests; mutual-aid societies, to provide loans and burial insurance; and commercial life insurance. In the middle decades of the twentieth century, in response to the mass unemployment and deprivation produced by the Great Depression (and the political success of communism and fascism, which convinced many democrats that too much insecurity was a threat to capitalist democracy itself), Western democracies embraced the welfare state. Different nations created different combinations of specific programs, but the new welfare states had a good deal in common, including old-age and unemployment insurance and various measures to support families.

The expansion of the welfare state in the decades after World War II took place at a time when the capitalist economies of the West were growing rapidly. The success of the industrial economy made it possible to siphon off profits and wages to government purposes through taxation. The demographics of the postwar era, in which the breadwinner-homemaker model of the family predominated, helped also, as moderately high birthrates created a favorable ratio of active workers to dependents. Educational opportunities expanded, as elite universities increasingly admitted students on the basis of their academic achievements and potential, and more and more people attended institutions of higher education. And barriers to full participation in society for women and minorities began to fall as well. The result of all of this was a temporary equilibrium during which the advanced capitalist countries experienced strong economic growth, high employment, and relative socioeconomic equality.

LIFE IN THE POSTINDUSTRIAL ECONOMY

For humanity in general, the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have been a period of remarkable progress, due in no small part to the spread of capitalism around the globe. Economic liberalization in China, India, Brazil, Indonesia, and other countries in the developing world has allowed hundreds of millions of people to escape grinding poverty and move into the middle class. Consumers in more advanced capitalist countries, such as the United States, meanwhile, have experienced a radical reduction in the price of many commodities, from clothes to televisions, and the availability of a river of new goods that have transformed their lives.

Most remarkable, perhaps, have been changes to the means of self-cultivation. As the economist Tyler Cowen notes, much of the fruit of recent developments "is in our minds and in our laptops and not so much in the revenue-generating sector of the economy." As a result, "much of the value of the internet is experienced at the personal level and so will never show up in the productivity numbers." Many of the great musical performances of the twentieth century, in every genre, are available on YouTube for free. Many of the great films of the twentieth century, once confined to occasional showings at art houses in a few metropolitan areas, can be viewed by anybody at any time for a small monthly charge. Soon, the great university libraries will be available online to the entire world, and other unprecedented opportunities for personal development will follow.

All this progress, however, has been shadowed by capitalism's perennial features of inequality and insecurity. In 1973, the sociologist Daniel Bell noted that in the advanced capitalist world, knowledge, science, and technology were driving a transformation to what he termed "postindustrial society." Just as manufacturing had previously displaced agriculture as the major source of employment, he argued, so the service sector was now displacing manufacturing. In a postindustrial, knowledge-based economy, the production of manufactured goods depended more on technological inputs than on the skills of the workers who actually built and assembled the products. That meant a relative decline in the need for and economic value of skilled and semiskilled factory workers—just as there had previously been a decline in the need for and value of agricultural laborers. In such an economy, the skills in demand included scientific and technical knowledge and the ability to work with information. The revolution in information technology that has swept through the economy in recent decades, meanwhile, has only exacerbated these trends.

One crucial impact of the rise of the postindustrial economy has been on the status and roles of men and women. Men's relative advantage in the preindustrial and industrial economies rested in large part on their greater physical strength—something now ever less in demand. Women, in contrast, whether by biological disposition or socialization, have had a relative advantage in human skills and emotional intelligence, which have become increasingly more important in an economy more oriented to human services than to the production of material objects. The portion of the economy in which women could participate has expanded, and their labor has become more valuable—meaning that time spent at home now comes at the expense of more lucrative possibilities in the paid work force.

This has led to the growing replacement of male breadwinner-female homemaker households by dual-income households. Both advocates and critics of the move of women into the paid economy have tended to overemphasize the role played in this shift by the ideological struggles of feminism, while underrating the role played by changes in the nature of capitalist production. The redeployment of female labor from the household has been made possible in part by the existence of new commodities that cut down on necessary household labor time (such as washing machines, dryers, dishwashers, water heaters, vacuum cleaners, microwave ovens). The greater time devoted to market activity, in turn, has given rise to new demand for household-oriented consumer goods that require less labor (such as packaged and prepared food) and the expansion of restaurant and fast-food eating. And it has led to the commodification of care, as the young, the elderly, and the infirm are increasingly looked after not by relatives but by paid minders.

The trend for women to receive more education and greater professional attainments has been accompanied by changing social norms in the choice of marriage partners. In the age of the breadwinner-homemaker marriage, women tended to place a premium on earning capacity in their choice of partners. Men, in turn, valued the homemaking capacities of potential spouses more than their vocational attainments. It was not unusual for men and women to marry partners of roughly the same intelligence, but women tended to marry men of higher levels of education and economic achievement. As the economy has passed from an industrial economy to a postindustrial service-and-information economy, women have joined men in attaining recognition through paid work, and the industrious couple today is more likely to be made of peers, with more equal levels of education and more comparable levels of economic achievement—a process termed "assortative mating."

INEQUALITY ON THE RISE

These postindustrial social trends have had a significant impact on inequality. If family income doubles at each step of the economic ladder, then the total incomes of those families higher up the ladder are bound to increase faster than the total incomes of those further down. But for a substantial portion of households at the lower end of the ladder, there has been no doubling at all—for as the relative pay of women has grown and the relative pay of less-educated, working-class men has declined, the latter have been viewed as less and less marriageable. Often, the limitations of human capital that make such men less employable also make them less desirable as companions, and the character traits of men who are chronically unemployed sometimes deteriorate as well. With less to bring to the table, such men are regarded as less necessary—in part because women can now count on provisions from the welfare state as an additional independent source of income, however meager.

In the United States, among the most striking developments of recent decades has been the stratification of marriage patterns among the various classes and ethnic groups of society. When divorce laws were loosened in the 1960s, there was a rise in divorce rates among all classes. But by the 1980s, a new pattern had emerged: divorce declined among the more educated portions of the populace, while rates among the less-educated portions continued to rise. In addition, the more educated and more well-to-do were more likely to wed, while the less educated were less likely to do so. Given the family's role as an incubator of human capital, such trends have had important spillover effects on inequality. Abundant research shows that children raised by two parents in an ongoing union are more likely to develop the self-discipline and self-confidence that make for success in life, whereas children—and particularly boys—reared in single-parent households (or, worse, households with a mother who has a series of temporary relationships) have a greater risk of adverse outcomes.

All of this has been taking place during a period of growing equality of access to education and increasing stratification of marketplace rewards, both of which have increased the importance of human capital. One element of human capital is cognitive ability: quickness of mind, the ability to infer and apply patterns drawn from experience, and the ability to deal with mental complexity. Another is character and social skills: self-discipline, persistence, responsibility. And a third is actual knowledge. All of these are becoming increasingly crucial for success in the postindustrial marketplace. As the economist Brink Lindsey notes in his recent book Human Capitalism , between 1973 and 2001, average annual growth in real income was only 0.3 percent for people in the bottom fifth of the U.S. income distribution, compared with 0.8 percent for people in the middle fifth and 1.8 percent for those in the top fifth. Somewhat similar patterns also prevail in many other advanced economies.

Globalization has not caused this pattern of increasingly unequal returns to human capital but reinforced it. The economist Michael Spence has distinguished between "tradable" goods and services, which can be easily imported and exported, and "untradable" ones, which cannot. Increasingly, tradable goods and services are imported to advanced capitalist societies from less advanced capitalist societies, where labor costs are lower. As manufactured goods and routine services are outsourced, the wages of the relatively unskilled and uneducated in advanced capitalist societies decline further, unless these people are somehow able to find remunerative employment in the untradable sector.

THE IMPACT OF MODERN FINANCE

Rising inequality, meanwhile, has been compounded by rising insecurity and anxiety for people higher up on the economic ladder. One trend contributing to this problem has been the financialization of the economy, above all in the United States, creating what was characterized as "money manager capitalism" by the economist Hyman Minsky and has been called "agency capitalism" by the financial expert Alfred Rappaport.

As late as the 1980s, finance was an essential but limited element of the U.S. economy. The trade in equities (the stock market) was made up of individual investors, large or small, putting their own money in stocks of companies they believed to have good long-term prospects. Investment capital was also available from the major Wall Street investment banks and their foreign counterparts, which were private partnerships in which the partners' own money was on the line. All of this began to change as larger pools of capital became available for investment and came to be deployed by professional money managers rather the owners of the capital themselves.

One source of such new capital was pension funds. In the postwar decades, when major American industries emerged from World War II as oligopolies with limited competition and large, expanding markets at home and abroad, their profits and future prospects allowed them to offer employees defined-benefit pension plans, with the risks involved assumed by the companies themselves. From the 1970s on, however, as the U.S. economy became more competitive, corporate profits became more uncertain, and companies (as well as various public-sector organizations) attempted to shift the risk by putting their pension funds into the hands of professional money managers, who were expected to generate significant profits. Retirement income for employees now depended not on the profits of their employers but on the fate of their pension funds.

Another source of new capital was university and other nonprofit organizations' endowments, which grew initially thanks to donations but were increasingly expected to grow further based on their investment performance. And still another source of new capital came from individuals and governments in the developing world, where rapid economic growth, combined with a high propensity to save and a desire for relatively secure investment prospects, led to large flows of money into the U.S. financial system.

Spurred in part by these new opportunities, the traditional Wall Street investment banks transformed themselves into publicly traded corporations—that is to say, they, too, began to invest not just with their own funds but also with other people's money—and tied the bonuses of their partners and employees to annual profits. All of this created a highly competitive financial system dominated by investment managers working with large pools of capital, paid based on their supposed ability to outperform their peers. The structure of incentives in this environment led fund managers to try to maximize short-term returns, and this pressure trickled down to corporate executives. The shrunken time horizon created a temptation to boost immediate profits at the expense of longer-term investments, whether in research and development or in improving the skills of the company's work force. For both managers and employees, the result has been a constant churning that increases the likelihood of job losses and economic insecurity.

An advanced capitalist economy does indeed require an extensive financial sector. Part of this is a simple extension of the division of labor: outsourcing decisions about investing to professionals allows the rest of the population the mental space to pursue things they do better or care more about. The increasing complexity of capitalist economies means that entrepreneurs and corporate executives need help in deciding when and how to raise funds. And private equity firms that have an ownership interest in growing the real value of the firms in which they invest play a key role in fostering economic growth. These matters, which properly occupy financiers, have important consequences, and handling them requires intelligence, diligence, and drive, so it is neither surprising nor undesirable that specialists in this area are highly paid. But whatever its benefits and continued social value, the financialization of society has nevertheless had some unfortunate consequences, both in increasing inequality by raising the top of the economic ladder (thanks to the extraordinary rewards financial managers receive) and in increasing insecurity among those lower down (thanks to the intense focus on short-term economic performance to the exclusion of other concerns).

THE FAMILY AND HUMAN CAPITAL

In today's globalized, financialized, postindustrial environment, human capital is more important than ever in determining life chances. This makes families more important, too, because as each generation of social science researchers discovers anew (and much to their chagrin), the resources transmitted by the family tend to be highly determinative of success in school and in the workplace. As the economist Friedrich Hayek pointed out half a century ago in The Constitution of Liberty , the main impediment to true equality of opportunity is that there is no substitute for intelligent parents or for an emotionally and culturally nurturing family. In the words of a recent study by the economists Pedro Carneiro and James Heckman, "Differences in levels of cognitive and noncognitive skills by family income and family background emerge early and persist. If anything, schooling widens these early differences."

Hereditary endowments come in a variety of forms: genetics, prenatal and postnatal nurture, and the cultural orientations conveyed within the family. Money matters, too, of course, but is often less significant than these largely nonmonetary factors. (The prevalence of books in a household is a better predictor of higher test scores than family income.) Over time, to the extent that societies are organized along meritocratic lines, family endowments and market rewards will tend to converge.

Educated parents tend to invest more time and energy in child care, even when both parents are engaged in the work force. And families strong in human capital are more likely to make fruitful use of the improved means of cultivation that contemporary capitalism offers (such as the potential for online enrichment) while resisting their potential snares (such as unrestricted viewing of television and playing of computer games).