National Historical Publications & Records Commission

The Papers of Thomas A. Edison

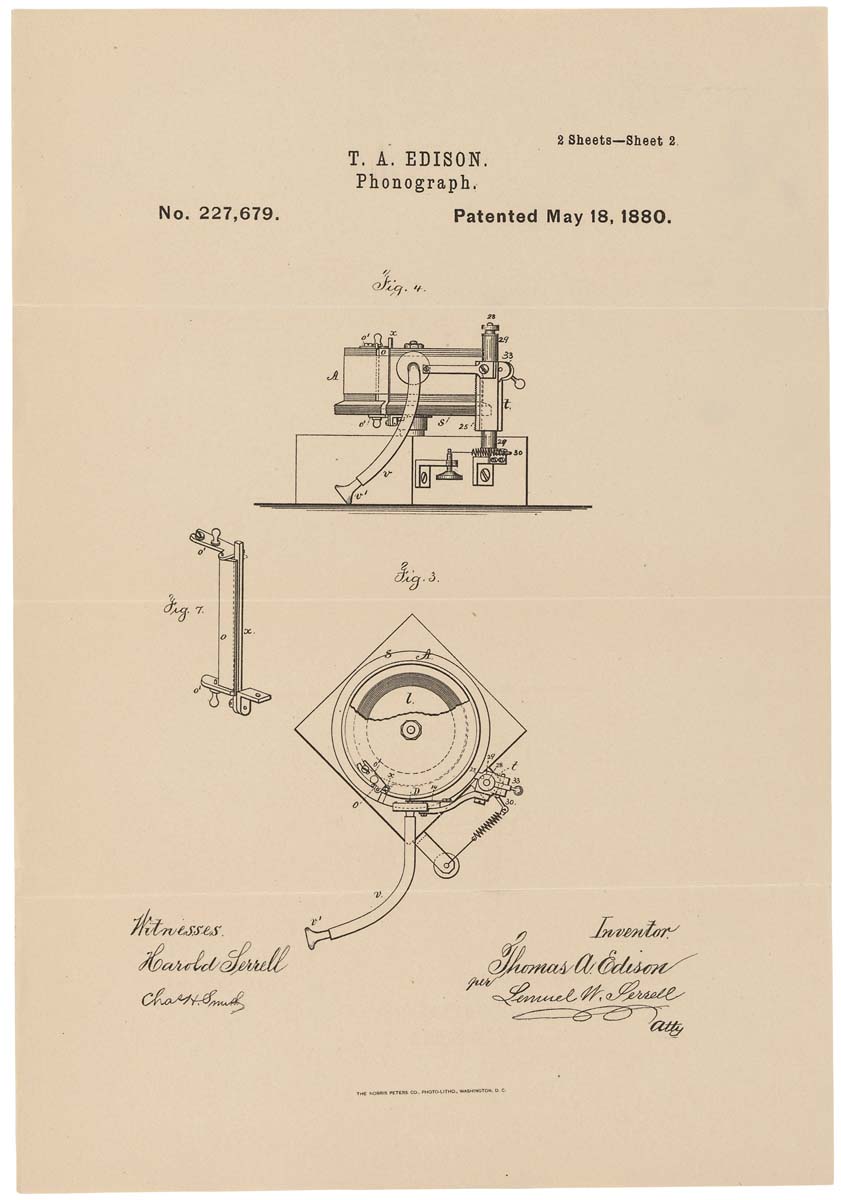

Drawing for a Phonograph, 1880, by Thomas A. Edison. National Archives.

Rutgers University

Publisher: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Project Website: http://edison.rutgers.edu/index.htm

A comprehensive edition of the papers of Thomas Alva Edison (1847 –1931), American inventor and businessman. He invented or developed the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and a long-lasting, practical electric light bulb. Dubbed “The Wizard of Menlo Park,” Edison applied the principles of mass production and large-scale teamwork to the process of invention, and because of that, he is often credited with the creation of the first industrial research laboratory. The NHPRC also funded a microfilm collection http://edison.rutgers.edu/microfilm.htm (1989-1999) containing approximately ten percent of the 5 million pages of Edison documents at the Edison National Historic Site. 288 microfilm reels covering the years 1850-1919.

Eight completed volumes of a planned 15-volume print edition, along with a digital edition of nearly 175,000 documents.

Previous Record | Next Record | Return to Index

- Search Grant Programs

- Application Review Process

- Manage Your Award

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- Search All Past Awards

- Divisions and Offices

- Professional Development

- Workshops, Resources, & Tools

- Sign Up to Be a Panelist

- Emergency and Disaster Relief

- Equity Action Plan

- States and Jurisdictions

- Featured NEH-Funded Projects

- Humanities Magazine

- Information for Native and Indigenous Communities

- Information for Pacific Islanders

- Search Our Work

- American Tapestry

- Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative

- Humanities Perspectives on Artificial Intelligence

- Pacific Islands Cultural Initiative

- United We Stand: Connecting Through Culture

- A More Perfect Union

- NEH Leadership

- Open Government

- Contact NEH

- Press Releases

- NEH in the News

Thomas Edison Papers

Division of research programs.

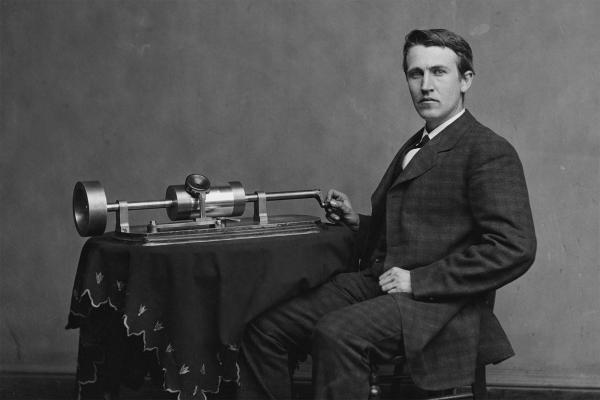

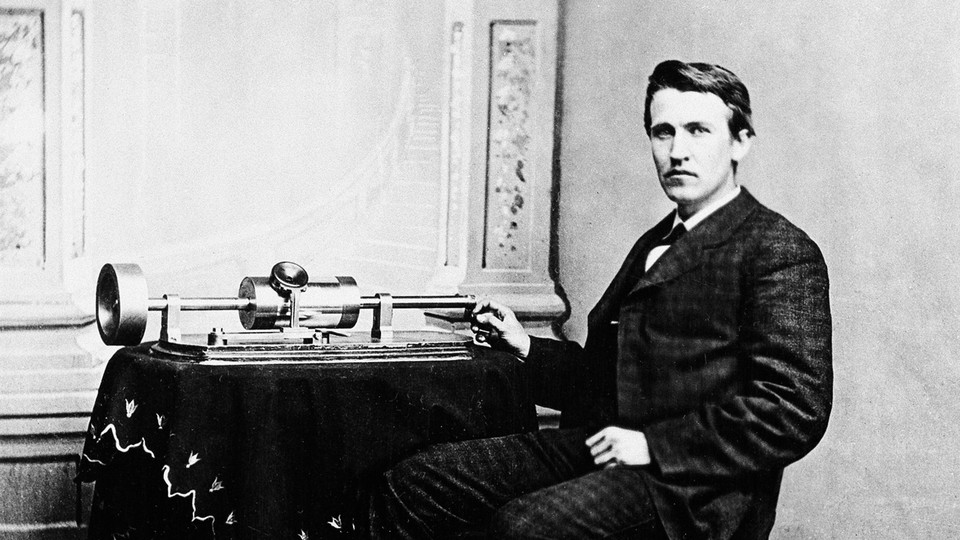

Thomas Edison with phonograph, 1870s.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Alva Edison was the most prolific inventor in American history. He amassed a record 1,093 patents covering key innovations and minor improvements in wide range of fields, including telecommunications, electric power, sound recording, motion pictures, primary and storage batteries, and mining and cement technology. Browse Edison’s laboratory notebooks, drawings, diaries, ambitious “to do” lists, and even notes for a science fiction novel at the NEH-funded Thomas Edison Papers project.

Related on NEH.gov

Heartbreak at menlo park.

Top of page

Collection Inventing Entertainment: The Early Motion Pictures and Sound Recordings of the Edison Companies

Life of thomas alva edison.

One of the most famous and prolific inventors of all time, Thomas Alva Edison exerted a tremendous influence on modern life, contributing inventions such as the incandescent light bulb, the phonograph, and the motion picture camera, as well as improving the telegraph and telephone. In his 84 years, he acquired an astounding 1,093 patents. Aside from being an inventor, Edison also managed to become a successful manufacturer and businessman, marketing his inventions to the public. A myriad of business liaisons, partnerships, and corporations filled Edison's life, and legal battles over various patents and corporations were continuous. The following is only a brief sketch of an enormously active and complex life full of projects often occurring simultaneously. Several excellent biographies are readily available in local libraries to those who wish to learn more about the particulars of his life and many business ventures.

Edison's Early Years

Thomas A. Edison's forebears lived in New Jersey until their loyalty to the British crown during the American Revolution drove them to Nova Scotia, Canada. From there, later generations relocated to Ontario and fought the Americans in the War of 1812. Edison's mother, Nancy Elliott, was originally from New York until her family moved to Vienna, Canada, where she met Sam Edison, Jr., whom she later married. When Sam became involved in an unsuccessful insurrection in Ontario in the 1830s, he was forced to flee to the United States and in 1839 they made their home in Milan, Ohio.

Thomas Alva Edison was born to Sam and Nancy on February 11, 1847, in Milan, Ohio. Known as "Al" in his youth, Edison was the youngest of seven children, four of whom survived to adulthood. Edison tended to be in poor health when young.

To seek a better fortune, Sam Edison moved the family to Port Huron, Michigan, in 1854, where he worked in the lumber business.

Edison was a poor student. When a schoolmaster called Edison "addled," his furious mother took him out of the school and proceeded to teach him at home. Edison said many years later, "My mother was the making of me. She was so true, so sure of me, and I felt I had some one to live for, some one I must not disappoint." 1 At an early age, he showed a fascination for mechanical things and for chemical experiments.

In 1859, Edison took a job selling newspapers and candy on the Grand Trunk Railroad to Detroit. In the baggage car, he set up a laboratory for his chemistry experiments and a printing press, where he started the Grand Trunk Herald , the first newspaper published on a train. An accidental fire forced him to stop his experiments on board.

Around the age of twelve, Edison lost almost all his hearing. There are several theories as to what caused his hearing loss. Some attribute it to the aftereffects of scarlet fever which he had as a child. Others blame it on a conductor boxing his ears after Edison caused a fire in the baggage car, an incident which Edison claimed never happened. Edison himself blamed it on an incident in which he was grabbed by his ears and lifted to a train. He did not let his disability discourage him, however, and often treated it as an asset, since it made it easier for him to concentrate on his experiments and research. Undoubtedly, though, his deafness made him more solitary and shy in dealings with others.

Telegraph Work

In 1862, Edison rescued a three-year-old from a track where a boxcar was about to roll into him. The grateful father, J.U. MacKenzie, taught Edison railroad telegraphy as a reward. That winter, he took a job as a telegraph operator in Port Huron. In the meantime, he continued his scientific experiments on the side. Between 1863 and 1867, Edison migrated from city to city in the United States taking available telegraph jobs.

In 1868 Edison moved to Boston where he worked in the Western Union office and worked even more on his inventions. In January 1869 Edison resigned his job, intending to devote himself fulltime to inventing things. His first invention to receive a patent was the electric vote recorder, in June 1869. Daunted by politicians' reluctance to use the machine, he decided that in the future he would not waste time inventing things that no one wanted.

Edison moved to New York City in the middle of 1869. A friend, Franklin L. Pope, allowed Edison to sleep in a room at Samuel Laws' Gold Indicator Company where he was employed. When Edison managed to fix a broken machine there, he was hired to manage and improve the printer machines.

During the next period of his life, Edison became involved in multiple projects and partnerships dealing with the telegraph. In October 1869, Edison formed with Franklin L. Pope and James Ashley the organization Pope, Edison and Co. They advertised themselves as electrical engineers and constructors of electrical devices. Edison received several patents for improvements to the telegraph. The partnership merged with the Gold and Stock Telegraph Co. in 1870. Edison also established the Newark Telegraph Works in Newark, NJ, with William Unger to manufacture stock printers. He formed the American Telegraph Works to work on developing an automatic telegraph later in the year. In 1874 he began to work on a multiplex telegraphic system for Western Union, ultimately developing a quadruplex telegraph, which could send two messages simultaneously in both directions. When Edison sold his patent rights to the quadruplex to the rival Atlantic & Pacific Telegraph Co., a series of court battles followed in which Western Union won. Besides other telegraph inventions, he also developed an electric pen in 1875.

His personal life during this period also brought much change. Edison's mother died in 1871, and later that year, he married a former employee, Mary Stilwell, on Christmas Day. While Edison clearly loved his wife, their relationship was fraught with difficulties, primarily his preoccupation with work and her constant illnesses. Edison would often sleep in the lab and spent much of his time with his male colleagues. Nevertheless, their first child, Marion, was born in February 1873, followed by a son, Thomas, Jr., born on January 1876. Edison nicknamed the two "Dot" and "Dash," referring to telegraphic terms. A third child, William Leslie was born in October 1878.

Edison opened a new laboratory in Menlo Park, NJ, in 1876. This site later become known as an "invention factory," since they worked on several different inventions at any given time there. Edison would conduct numerous experiments to find answers to problems. He said, "I never quit until I get what I'm after. Negative results are just what I'm after. They are just as valuable to me as positive results." 2 Edison liked to work long hours and expected much from his employees.

In 1877, Edison worked on a telephone transmitter that greatly improved on Alexander Graham Bell's work with the telephone. His transmitter made it possible for voices to be transmitted at higer volume and with greater clarity over standard telephone lines.

Edison's experiments with the telephone and the telegraph led to his invention of the phonograph in 1877. It occurred to him that sound could be recorded as indentations on a rapidly-moving piece of paper. He eventually formulated a machine with a tinfoil-coated cylinder and a diaphragm and needle. When Edison spoke the words "Mary had a little lamb" into the mouthpiece, to his amazement the machine played the phrase back to him. The Edison Speaking Phonograph Company was established early in 1878 to market the machine, but the initial novelty value of the phonograph wore off, and Edison turned his attention elsewhere.

Edison focused on the electric light system in 1878, setting aside the phonograph for almost a decade. With the backing of financiers, The Edison Electric Light Co. was formed on November 15 to carry out experiments with electric lights and to control any patents resulting from them. In return for handing over his patents to the company, Edison received a large share of stock. Work continued into 1879, as the lab attempted not only to devise an incandescent bulb, but an entire electrical lighting system that could be supported in a city. A filament of carbonized thread proved to be the key to a long-lasting light bulb. Lamps were put in the laboratory, and many journeyed out to Menlo Park to see the new discovery. A special public exhibition at the lab was given for a multitude of amazed visitors on New Year's Eve.

Edison set up an electric light factory in East Newark in 1881, and then the following year moved his family and himself to New York and set up a laboratory there.

In order to prove its viability, the first commercial electric light system was installed on Pearl Street in the financial district of Lower Manhattan in 1882, bordering City Hall and two newspapers. Initially, only four hundred lamps were lit; a year later, there were 513 customers using 10,300 lamps. 3 Edison formed several companies to manufacture and operate the apparatus needed for the electrical lighting system: the Edison Electric Illuminating Company of New York, the Edison Machine Works, the Edison Electric Tube Company, and the Edison Lamp Works. This lighting system was also taken abroad to the Paris Lighting Exposition in 1881, the Crystal Palace in London in 1882, the coronation of the czar in Moscow, and led to the establishment of companies in several European countries.

The success of Edison's lighting system could not deter his competitors from developing their own, different methods. One result was a battle between the proponents of DC current, led by Edison, and AC current, led by George Westinghouse . Both sides attacked the limitations of each system. Edison, in particular, pointed to the use of AC current for electrocution as proof of its danger. DC current could not travel over as long a system as AC, but the AC generators were not as efficient as the ones for DC. By 1889, the invention of a device that combined an AC induction motor with a DC dynamo offered the best performance of all, and AC current became dominant. The Edison General Electric Co. merged with Thomson-Houston in 1892 to become General Electric Co., effectively removing Edison further from the electrical field of business.

An Improved Phonograph

Edison's wife, Mary, died on August 9, 1884, possibly from a brain tumor. Edison remarried to Mina Miller on February 24, 1886, and, with his wife, moved into a large mansion named Glenmont in West Orange, New Jersey. Edison's children from his first marriage were distanced from their father's new life, as Edison and Mina had their own family: Madeleine, born on 1888; Charles on 1890; and Theodore on 1898. Unlike Mary, who was sickly and often remained at home, and was also deferential to her husband's wishes, Mina was an active woman, devoting much time to community groups, social functions, and charities, as well as trying to improve her husband's often careless personal habits.

In 1887, Edison had built a new, larger laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey. The facility included a machine shop, phonograph and photograph departments, a library, and ancillary buildings for metallurgy, chemistry, woodworking, and galvanometer testings.

While Edison had neglected further work on the phonograph , others had moved forward to improve it. In particular, Chichester Bell and Charles Sumner Tainter developed an improved machine that used a wax cylinder and a floating stylus, which they called a graphophone. They sent representatives to Edison to discuss a possible partnership on the machine, but Edison refused to collaborate with them, feeling that the phonograph was his invention alone. With this competition, Edison was stirred into action and resumed his work on the phonograph in 1887. Edison eventually adopted methods similar to Bell and Tainter's in his own phonograph.

The phonograph was initially marketed as a business dictation machine. Entrepreneur Jesse H. Lippincott acquired control of most of the phonograph companies, including Edison's, and set up the North American Phonograph Co. in 1888. The business did not prove profitable, and when Lippincott fell ill, Edison took over the management. In 1894, the North American Phonograph Co. went into bankruptcy, a move which allowed Edison to buy back the rights to his invention. In 1896, Edison started the National Phonograph Co. with the intent of making phonographs for home amusement. Over the years, Edison made improvements to the phonograph and to the cylinders which were played on them, the early ones being made of wax. Edison introduced an unbreakable cylinder record, named the Blue Amberol, at roughly the same time he entered the disc phonograph market in 1912. The introduction of an Edison disc was in reaction to the overwhelming popularity of discs on the market in contrast to cylinders. Touted as being superior to the competition's records, the Edison discs were designed to be played only on Edison phonographs, and were cut laterally as opposed to vertically. The success of the Edison phonograph business, though, was always hampered by the company's reputation of choosing lower-quality recording acts. In the 1920s, competition from radio caused business to sour, and the Edison disc business ceased production in 1929.

Other Ventures: Ore-milling and Cement

Another Edison interest was an ore-milling process that would extract various metals from ore. In 1881, he formed the Edison Ore-Milling Co., but the venture proved fruitless as there was no market for it. In 1887, he returned to the project, thinking that his process could help the mostly depleted Eastern mines compete with the Western ones. In 1889, the New Jersey and Pennsylvania Concentrating Works was formed, and Edison became absorbed by its operations and began to spend much time away from home at the mines in Ogdensburg, New Jersey. Although he invested much money and time into this project, it proved unsuccessful when the market went down and additional sources of ore in the Midwest were found.

Edison also became involved in promoting the use of cement and formed the Edison Portland Cement Co. in 1899. He tried to promote widespread use of cement for the construction of low-cost homes and envisioned alternative uses for concrete in the manufacture of phonographs, furniture, refrigerators, and pianos. Unfortunately, Edison was ahead of his time with these ideas, as widespread use of concrete proved economically unfeasible at that time.

Motion Pictures

In 1888, Edison met Eadweard Muybridge at West Orange and viewed Muybridge's zoopraxiscope. This machine used a circular disc with still photographs of the successive phases of movement around the circumference to recreate the illusion of movement. Edison declined to work with Muybridge on the device and decided to work on his own motion picture camera at his laboratory. As Edison put it in a caveat written the same year, "I am experimenting upon an instrument which does for the eye what the phonograph does for the ear." 4

The task of inventing the machine fell to Edison's associate William K. L. Dickson. Dickson initially experimented with a cylinder-based device for recording images, before turning to a celluloid strip. In October of 1889, Dickson greeted Edison's return from Paris with a new device that projected pictures and contained sound. After more work, patent applications were made in 1891 for a motion picture camera, called a Kinetograph, and a Kinetoscope, a motion picture peephole viewer.

Kinetoscope parlors opened in New York and soon spread to other major cities during 1894. In 1893, a motion picture studio, later dubbed the Black Maria (the slang name for a police paddy wagon which the studio resembled), was opened at the West Orange complex. Short films were produced using variety acts of the day. Edison was reluctant to develop a motion picture projector, feeling that more profit was to be made with the peephole viewers.

When Dickson aided competitors on developing another peephole motion picture device and the eidoloscope projection system, later to develop into the Mutoscope, he was fired. Dickson went on to form the American Mutoscope Co. along with Harry Marvin, Herman Casler, and Elias Koopman. Edison subsequently adopted a projector developed by Thomas Armat and Charles Francis Jenkins and re-named it the Vitascope and marketed it under his name. The Vitascope premiered on April 23, 1896, to great acclaim.

Competition from other motion picture companies soon created heated legal battles between them and Edison over patents. Edison sued many companies for infringement. In 1909, the formation of the Motion Picture Patents Co. brought a degree of cooperation to the various companies who were given licenses in 1909, but in 1915, the courts found the company to be an unfair monopoly.

In 1913, Edison experimented with synchronizing sound to film. A Kinetophone was developed by his laboratory which synchronized sound on a phonograph cylinder to the picture on a screen. Although this initially brought interest, the system was far from perfect and disappeared by 1915. By 1918, Edison ended his involvement in the motion picture field.

Edison's Later Years

In 1911, Edison's companies were re-organized into Thomas A. Edison, Inc. As the organization became more diversified and structured, Edison became less involved in the day-to-day operations, although he still had some decision-making authority. The goals of the organization became more to maintain market viability than to produce new inventions frequently.

A fire broke out at the West Orange laboratory in 1914, destroying 13 buildings. Although the loss was great, Edison spearheaded the rebuilding of the lot.

When Europe became involved in World War I, Edison advised preparedness, and felt that technology would be the future of war. He was named head of the Naval Consulting Board in 1915, an attempt by the government to bring science into its defense program. Although mainly an advisory board, it was instrumental in the formation of a laboratory for the Navy which opened in 1923, although several of Edison's suggestions on the matter were disregarded. During the war, Edison spent much of his time doing naval research, in particular working on submarine detection, but he felt that the navy was not receptive to many of his inventions and suggestions.

In the 1920s, Edison's health became worse, and he began to spend more time at home with his wife. His relationship with his children was distant, although Charles was president of Thomas A. Edison, Inc. While Edison continued to experiment at home, he could not perform some experiments that he wanted to at his West Orange laboratory because the board would not approve them. One project that held his fascination during this period was the search for an alternative to rubber.

Henry Ford, an admirer and friend of Edison's, reconstructed Edison's invention factory as a museum at Greenfield Village, Michigan, which opened during the 50th anniversary of Edison's electric light in 1929. The main celebration for Light's Golden Jubilee, co-hosted by Ford and General Electric, took place in Dearborn along with a huge celebratory dinner in Edison's honor attended by notables such as President Hoover, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., George Eastman, Marie Curie, and Orville Wright. Edison's health, however, had declined to the point that he could not stay for the entire ceremony.

For his last two years, a series of ailments caused his health to decline even more until he lapsed into a coma on October 14, 1931. He died on October 18, 1931, at his estate, Glenmont, in West Orange, New Jersey.

- Martin V. Melosi, Thomas A. Edison and the Modernization of America , (Glenview, Illinois: Scott, Foresman/Little, Brown Higher Education, 1990) p. 8. [ Return to text ]

- Poster for Thomas A. Edison 150th Anniversary, 1847-1997, United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Edison National Historic Site, West Orange, New Jersey. [ Return to text ]

- Melosi, p. 73. [ Return to text ]

- Matthew Josephson, Edison: A Biography , (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1959) p. 386. [ Return to text ]

History Vault

- Bookmarks and MARC records

Thomas A. Edison Papers

Thomas A. Edison Papers (Module 19)

Inventor, businessman, scientist, industrialist, entrepreneur, engineer—Thomas Alva Edison developed many of the technologies that have shaped the modem world. Perhaps more than anyone else, Edison integrated the worlds of science, technology, business, and finance. Edison's work laid the foundation for the age of electricity, recorded sound, and motion pictures. In addition, he used team research and development with such great success at his Menlo Park and, West Orange, New Jersey, laboratories that he helped introduce the era of modem industrial research.

The life, work, and vision of Thomas Edison are documented in the laboratory notebooks, diaries, business records, correspondence, and related papers that have survived since his death. Access to these papers is a boon to scholars in many areas of study: the history of science and technology, business and economic history, the history of popular culture, film history, social and labor history, and other diverse interests. Because of the massive quantity of material and its limited accessibility, these resources have been neglected.

The Edison Papers show directly the interrelatedness of technological innovation and cultural change. Edison's development and promotion of inventions such as the phonograph and the kinetoscope and his marketing of sound recordings and motion pictures both reflected and disrupted the cultural practices of his time. Students of American culture will find these records of special interest.

- Search Thomas A. Edison Papers

- Browse Collections in Thomas A. Edison Papers

- Sales Brochure with description and title list

Patents and related materials

- Patents issued in 1869 First of annual files (there are files for 1869-1933) in collection

- Shop and laboratory scrapbook 1870-71. Some of the drawings are by Edison; others were probably done by draftsmen and mechanics at the American Telegraph Works.

- Patent application drawings 1876-78

- Motion Picture Patents Company files relating to the General Film Company 1916. Correspondence and other documents authored by or sent to Thomas A. Edison, Charles Edison, Leonard W. McChesney, Carl H. Wilson, and other officials of Thomas A. Edison, Inc.

Motion Picture Catalogs

- Raff and Gammon film catalogs Jan 01, 1894 - Dec 31, 1896

- Edison Manufacturing Company film and equipment catalogs Jan 01, 1898 - Dec 31, 1902

- Edison Manufacturing Company film catalogs Jan 01, 1904 - Dec 31, 1907

- Kalem Company film catalog for "Ben Hur" 1908.

- Sears, Roebuck and Company film, equipment, and accessories catalogs 1900, 1907

Clippings and Correspondence

- Unbound miscellaneous clippings, 1906 Lengthy interview, pgs 23-37 of PDF.

- Letters to Edison, opinions on a variety of subjects, 1916. Correspondence and other documents concerning Edison's life story, his response to erroneous newspaper reports about him, his opinions regarding a variety of subjects, and numerous other matters. Letter from T. Roosevelt (p.30), Letters regarding alcohol/prohibition (pgs. 13-4, 46-8)

- Opinions about harnessing hydraulic power from tides 1912.

- Unsolicited personal correspondence to Thomas Edison 1910. Often include his handwritten notes of response

The Papers of Thomas A. Edison

Thomas A. Edison edited by Paul B. Israel, Louis Carlat, Theresa M. Collins, Alexandra R. Rimer, and Daniel J. Weeks

This richly illustrated volume explores Edison’s inventive and personal pursuits from 1885 to 1887. Two decades after the American Civil War, no name was more closely associated with the nation’s inventive and entrepreneurial spirit than that of Thomas Edison. The restless changes of those years were reflected in the life of America’s foremost inventor. Having cemented his reputation with his electric lighting system, Edison had decided to withdraw partially from that field. At the start of 1885, newly widowed at mid-life with three young children, he launched into a series of personal and...

This richly illustrated volume explores Edison’s inventive and personal pursuits from 1885 to 1887. Two decades after the American Civil War, no name was more closely associated with the nation’s inventive and entrepreneurial spirit than that of Thomas Edison. The restless changes of those years were reflected in the life of America’s foremost inventor. Having cemented his reputation with his electric lighting system, Edison had decided to withdraw partially from that field. At the start of 1885, newly widowed at mid-life with three young children, he launched into a series of personal and professional migrations, setting in motion chains of events that would influence his work and fundamentally reshape his life.

Edison’s inventive activities took off in new directions, flowing between practical projects (such as wireless and high-capacity telegraph systems) and futuristic ones (exploring forms of electromagnetic energy and the convertibility of one to another). Inside of two years, he would travel widely, marry the daughter of a prominent industrialist and religious educator, leave New York City for a grand home in a sylvan suburb, and construct a winter laboratory and second home in Florida. Edison’s family and interior life are remarkably visible at this moment; his papers include the only known diary in which he recorded personal thoughts and events. By 1887, the familiar rhythms of his life began to reassert themselves in his new settings; the family faded from view as he planned, built, and occupied a New Jersey laboratory complex befitting his status.

The eighth volume of the series, New Beginnings includes 358 documents (chosen from among thousands) that are the most revealing and representative of Edison’s work, life, and place in American culture in these years. Illustrated with hundreds of Edison’s drawings, these documents are further illuminated by meticulous research on a wide range of sources, including the most recently digitized newspapers and journals of the day.

Related Books

Thomas A. Edison edited by Paul B. Israel, Louis Carlat, David Hochfelder, Theresa M. Collins, and Brian C. Shipley

Thomas A. Edison edited by Paul B. Israel, Louis Carlat, Theresa M. Collins, and David Hochfelder

David C. Hoffman

For those who want to delve deeply into Edison’s life and business dealings, this is another essential key to the puzzle.

A mine of material... Scrupulously edited... No one could ask for more... A choplicking feast for future Edison biographers—well into the next century, and perhaps beyond.

A triumph of the bookmaker's art, with splendidly arranged illustrations, essential background information, and cautionary reminders of the common sources on which Edison's imagination drew.

In the pages of this volume Edison the man, his work, and his times come alive... A delight to browse through or to read carefully.

What is most extraordinary about the collection isn't necessarily what it reveals about Edison's inventions... It's the insight into the process.

Those interested in America's technological culture can eagerly look forward to the appearance of each volume of the Edison Papers.

His lucidity comes through everywhere... His writing and drawing come together as a single, vigorous thought process.

Beyond its status as the resource for Edison studies, providing a near inexhaustible supply of scholarly fodder, this series... will surely become a model for such projects in the future... The sheer diversity of material offered here refreshingly transcends any exclusive restriction to Edisonia.

In its superabundance of detail—steely facts and figures, great plates of text riveted with nouns and graffitied with cryptic drawings (Edison was an untrained but natural draftsman)—the book has the same kind of physical impact as that which stuns you when you enter his laboratory in West Orange, N.J.

Book Details

Calendar of Documents List of Editorial Headnotes List of Maps Preface Chronology of Thomas A. Edison, January 1885-December 1887 Editorial Policy and User's Guide Editorial Symbols List of Abbreviations 1

Calendar of Documents List of Editorial Headnotes List of Maps Preface Chronology of Thomas A. Edison, January 1885-December 1887 Editorial Policy and User's Guide Editorial Symbols List of Abbreviations 1. January-June 1885 2. July-December 1885 3. January-April 1886 4. May-September 1886 5. October-December 1886 6. January-May 1887 7. June-September 1887 8. october-December 1887 Appendix 1. Edison's Autobiographical Notes Appendix 2. Edison's Patent Applications, 1885-1887 Bibliography Credits Index

Thomas A. Edison

Paul b. israel, ph.d., louis carlat, theresa m. collins, alexandra r. rimer, daniel j. weeks.

with Hopkins Press Books

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Early years

- The phonograph

- The electric light

- The Edison laboratory

How did Thomas Edison become famous?

- When was the telephone patented?

Thomas Edison

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Library of Congress - Digital Collections - Life of Thomas Alva Edison

- Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation - Thomas Edison's Inventive Life

- National Park Service - Biography of Thomas Edison

- National Academy of Sciences - Biographical Memoirs - "Thomas Alva Edison"

- Energy.gov - Top 8 Things You Didn’t Know About Thomas Alva Edison

- The Franklin Institute - Case Files: Thomas A. Edison

- Official Site of Edison Innovation Foundation

- The National Museum of American History - Lighting A Revolution - Lamp Inventors 1880-1940: Carbon Filament Incandescent

- American Chemical Society - Biography of Thomas Edison

- Thomas Edison - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Thomas Edison - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

When was Thomas Edison born?

Thomas Alva Edison was born in Milan , Ohio , on February 11, 1847.

When did Thomas Edison die?

Thomas Edison died on October 18, 1931, in West Orange , New Jersey .

Thomas Edison unveiled the phonograph —which reproduced sounds by means of the vibration of a stylus following a groove on a rotating disc—in December 1877. The public’s amazement surrounding this invention was quickly followed by universal acclaim. Edison was projected into worldwide prominence and was dubbed the Wizard of Menlo Park.

How did Thomas Edison change the world?

Thomas Edison played a significant part in introducing the modern age of electricity . His inventions included the phonograph, the carbon-button transmitter for the telephone speaker and microphone , the incandescent lamp , the first commercial electric light and power system, an experimental electric railroad , and key elements of motion-picture equipment.

Thomas Edison (born February 11, 1847, Milan , Ohio , U.S.—died October 18, 1931, West Orange , New Jersey) was an American inventor who, singly or jointly, held a world-record 1,093 patents . In addition, he created the world’s first industrial research laboratory .

Edison was the quintessential American inventor in the era of Yankee ingenuity. He began his career in 1863, in the adolescence of the telegraph industry, when virtually the only source of electricity was primitive batteries putting out a low-voltage current . Before he died, in 1931, he had played a critical role in introducing the modern age of electricity . From his laboratories and workshops emanated the phonograph , the carbon-button transmitter for the telephone speaker and microphone , the incandescent lamp , a revolutionary generator of unprecedented efficiency , the first commercial electric light and power system, an experimental electric railroad , and key elements of motion-picture apparatus , as well as a host of other inventions.

Edison was the seventh and last child—the fourth surviving—of Samuel Edison, Jr., and Nancy Elliot Edison. At an early age he developed hearing problems, which have been variously attributed but were most likely due to a familial tendency to mastoiditis . Whatever the cause, Edison’s deafness strongly influenced his behaviour and career, providing the motivation for many of his inventions.

In 1854 Samuel Edison became the lighthouse keeper and carpenter on the Fort Gratiot military post near Port Huron , Michigan , where the family lived in a substantial home. Alva, as the inventor was known until his second marriage, entered school there and attended sporadically for five years. He was imaginative and inquisitive, but, because much instruction was by rote and he had difficulty hearing, he was bored and was labeled a misfit. To compensate, he became an avid and omnivorous reader. Edison’s lack of formal schooling was not unusual. At the time of the Civil War the average American had attended school a total of 434 days—little more than two years’ schooling by today’s standards.

In 1859 Edison quit school and began working as a trainboy on the railroad between Detroit and Port Huron. Four years earlier, the Michigan Central had initiated the commercial application of the telegraph by using it to control the movement of its trains, and the Civil War brought a vast expansion of transportation and communication . Edison took advantage of the opportunity to learn telegraphy and in 1863 became an apprentice telegrapher.

Messages received on the initial Morse telegraph were inscribed as a series of dots and dashes on a strip of paper that was decoded and read, so Edison’s partial deafness was no handicap. Receivers were increasingly being equipped with a sounding key, however, enabling telegraphers to “read” messages by the clicks. The transformation of telegraphy to an auditory art left Edison more and more disadvantaged during his six-year career as an itinerant telegrapher in the Midwest, the South, Canada , and New England . Amply supplied with ingenuity and insight, he devoted much of his energy toward improving the inchoate equipment and inventing devices to facilitate some of the tasks that his physical limitations made difficult. By January 1869 he had made enough progress with a duplex telegraph (a device capable of transmitting two messages simultaneously on one wire) and a printer , which converted electrical signals to letters, that he abandoned telegraphy for full-time invention and entrepreneurship.

Edison moved to New York City , where he initially went into partnership with Frank L. Pope, a noted electrical expert, to produce the Edison Universal Stock Printer and other printing telegraphs. Between 1870 and 1875 he worked out of Newark , New Jersey , and was involved in a variety of partnerships and complex transactions in the fiercely competitive and convoluted telegraph industry, which was dominated by the Western Union Telegraph Company . As an independent entrepreneur he was available to the highest bidder and played both sides against the middle. During this period he worked on improving an automatic telegraph system for Western Union’s rivals. The automatic telegraph, which recorded messages by means of a chemical reaction engendered by the electrical transmissions, proved of limited commercial success, but the work advanced Edison’s knowledge of chemistry and laid the basis for his development of the electric pen and mimeograph , both important devices in the early office machine industry, and indirectly led to the discovery of the phonograph . Under the aegis of Western Union he devised the quadruplex, capable of transmitting four messages simultaneously over one wire, but railroad baron and Wall Street financier Jay Gould , Western Union’s bitter rival, snatched the quadruplex from the telegraph company’s grasp in December 1874 by paying Edison more than $100,000 in cash, bonds, and stock, one of the larger payments for any invention up to that time. Years of litigation followed.

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- The Papers of Thomas A. Edison: From Workshop to Laboratory, June 1873-March 1876

In this Book

- Thomas A. Edison. edited by Robert A. Roseberg, Paul B. Israel, Keith A. Nier, and Melodie Andrews

- Published by: Johns Hopkins University Press

- Series: The Papers of Thomas A. Edison

- View Citation

Table of Contents

- Title Page, Frontispiece, Copyright, Dedication

- Calendar of Documents

- pp. xiii-xxiii

- List of Editorial Headnotes

- pp. xxv-xxix

- Chronology of Thomas A. Edison, June 1873–March 1876

- pp. xxx-xxxvi

- Editorial Policy

- pp. xxxvii-xxxix

- Editorial Symbols

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 June–September 1873: (Docs. 341–364)

- 2 October–December 1873: (Docs. 365–389)

- 3 January–March 1874: (Docs. 390–417)

- pp. 121-171

- 4 April–June 1874: (Docs. 418–448)

- pp. 172-225

- 5 July–September 1874: (Docs. 449–494)

- pp. 226-311

- 6 October–December 1874: (Docs. 495–524)

- pp. 312-371

- 7 January–March 1875: (Docs. 525–557)

- pp. 372-460

- 8 April–June 1875: (Docs. 558–590)

- pp. 461-505

- 9 July–September 1875: (Docs. 591–634)

- pp. 506-579

- 10 October–December 1875: (Docs. 635–703)

- pp. 580-703

- 11 January–March 1876: (Docs. 704–737)

- pp. 704-776

- Appendix 1. Edison's Autobiographical Notes

- pp. 777-790

- Appendix 2. Charles Batchelor's Recollections of Edison

- pp. 791-793

- Appendix 3. The Dispute over the Quadruplex

- pp. 794-815

- Appendix 4. Edison's U.S. Patents, July 1873– March 1876

- pp. 816-818

- Bibliography

- pp. 819-824

- pp. 825-826

- pp. 827-842

Additional Information

Project MUSE Mission

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

The Undiscovered World of Thomas Edison

Historians, sorting through a treasure trove of Edison's papers, are discovering revealing details that enrich our portrait of one of America's most accomplished inventors

When an associate asked Thomas Alva Edison about the secret to his talent for invention, the plainspoken Edison retorted, "Genius is hard work, stick-to-itiveness, and common sense."

"There's still more!" his colleague said imploringly. "Although [the rest of us] know quite a lot … and worked hard, we couldn't invent … as you did."

What Edison never seemed to grasp was that his "common sense" was exceedingly uncommon—freakish, really. More patents were issued to him than have been issued to any other single person in U.S. history: 1,093. But Edison's towering status reflects more than his extraordinary productivity. He created things that transformed our world—among them the phonograph, the motion-picture camera, and the incandescent light bulb. And he made substantial contributions to numerous technologies, including telegraphy, telephone communications, and several business procedures.

Yet, in the six decades since the inventor's death, little serious writing has been done about Edison's remarkable genius for invention. In the words of the historian Keith Nier, "He is actually one of the least well known of all famous people, and much of what everybody thinks they know about him is no more reliable than a fairy tale."

Nier is one of eight historians at Rutgers University and at the Edison National Historic Site, in West Orange, New Jersey, who are now trying to set the record straight. The team, headed by Robert Rosenberg, is in the process of editing and publishing selected documents from the inventor's life's work. The scale of their endeavor is virtually unprecedented in the history of technology and science. What is now known as the Edison Papers Project started in 1978, when archivists estimated that the inventor's estate included just over a million pages of documents. Having been told that the contents had been "loosely organized" by previous archivists, the Edison Papers staff expected to have chosen the documents for a highly selective microfilm edition within a decade, after which a still more selective book edition would be completed.

Alas, organization, like beauty, turns out to be in the eye of the beholder. "It was a big mess," recalls the associate director of the project, Thomas Jeffrey, remembering his dismay at seeing for the first time the documents housed at the extensive industrial complex that makes up the Edison National Historic Site. Dusty stacks of papers—many seemingly untouched since Edison's death—sprouted as haphazardly as weeds across the space. Jeffrey, who had been hired to make the initial selection for the microfilm edition, instead found himself leading a scouting expedition. "We went from building to building, room to room, drawer to drawer," he recalls. "It took us more than a year just to get to the end of the paper trail, and when we added up the numbers in our inventory, we were shocked."

The collection turned out to include at least four million pages, and quite possibly as many as five million. According to Jeffrey's most recent estimate, publishing a representative sample of the inventor's work in both a microfilm edition and a printed edition of fifteen to twenty volumes could take until 2015. (To date the team has published more than 250,000 pages of documents on microfilm and three enormous printed volumes, and has begun preparing for electronic publication.)

Now, seventeen years into the project, the historians have become so intimately acquainted with their subject that, as Rosenberg half guiltily admits, "we've become spies inside his mind." All are acutely aware of their unique privilege. In many instances they are the first people since the inventor's death to gaze on laboratory records, early drafts of patent applications, letters, photos of models, and other telling memorabilia.

Luckily for posterity, the process by which Edison invented is documented in exquisite detail in a series of 3,500 notebooks. The researchers unabashedly compare his fecundity of ideas to Leonardo da Vinci's. The notebooks are filled with fascinating observations and insights—many pertaining to unrelated projects, in a seeming free flow of associations. Consecutive sketches—some rough and crude, others executed with the exactitude of a draftsman—traverse a vast spectrum of technologies.

On New Year's Day, 1871, more than three decades before the Wright brothers' historic flight, Edison speculated that "a Paines engine can be so constructed of steel & with hollow magnets … and combined with suitable air propelling apparatus wings … as to produce a flying machine of extreme lightness and tremendous power." "Discovery," begins an entry dated May 26, 1877. "If you look very closely at any printed matter so that the print is greatly blurred and you see double images of the type … one of the double images is always blue or ultra violet=" "Glorious= Telephone perfected this morning 5 AM," he confidently proclaimed in a notebook entry two months later. "Articulation perfect."

Not all his ideas reached fruition, of course. His flying machine was never mentioned again. Nor does anything appear to have come of the blue-violet optical effect that he found so captivating. As for his "perfected" telephone, it turned out to have numerous flaws that required another nine months to iron out.

Between inventive flurries Edison's mind seems to have wandered, as evidenced by pages decorated in half a dozen florid styles of calligraphy. Occasionally he even jotted down a poem. Here is a notebook sample from the mid-1870s:

A yellow oasis in hell= premeditated stupidity= A phrenological idol. The somber dream of the grey-eyed Corsican A Brain so small that an animalcule went to view it with a compound microscope …

Edison's genius is all the more remarkable when viewed against the backdrop of his unexceptional childhood. Born in 1847, he was raised in Port Huron, Michigan, by parents with no special mechanical bent. His mother, a former schoolteacher, provided him with a few years of instruction at home. His father, a jack-of-all-trades who tried his hand at everything from real-estate speculation to running a small grocery store, was also highly literate and had a collection of books that young Tom eagerly consumed. In his early teens the youth began reading science books that described chemistry experiments. He had a job selling newspapers and candy to passengers on the Grand Trunk Railway between Port Huron and Detroit, and during breaks from work he tried out some of these experiments in a baggage car.

Later in his teens he received a more thorough grounding in the rudiments of what would soon be his trade while hanging around railroad yards, newspaper offices, and machine shops, and working in a jeweler's shop and various telegraph offices. On these jobs he was exposed to lathes and various precision tools, clockwork and printing equipment, and a wide assortment of telegraphy instruments, which he studied and experimented with during his spare time.

By his early twenties Edison, moonlighting as an inventor, had totted up enough successes to win lucrative research contracts from Western Union and other prominent firms, giving him the confidence to strike out on his own. But he never fit the popular stereotype of the reclusive nineteenth-century inventor, struggling alone in a garret. From the start collaboration was critical to his success. Indeed, one of Edison's greatest accomplishments was the invention of an entirely new institution—the independent industrial-research laboratory, or what he affectionately called his "invention factory."

At his first large independent laboratory, in Menlo Park, and later at facilities in West Orange, Edison kept a well-stocked chemistry lab and a machine shop under one roof—a considerable novelty for that period. He also surrounded himself with a core group of half a dozen or more assistants. A few were university-educated men specially chosen because of their expertise in fields in which Edison felt himself to be deficient (mathematics was one). His intimate working relationships with the mechanic and experimenter Charles Batchelor, who assisted him over much of his career; with Francis Upton, a major collaborator on electric lighting; and with the electrical engineer Arthur Kennelly—to mention only a few of his closest associates—have long been appreciated by scholars. But the new research into Edison's papers shows that Edison's talent for motivating people extended well beyond this elite inner circle—a finding that may contain an important lesson for the entrepreneurial research-and-development firms that are the modern-day incarnations of Edison's vision.

Everyone—from his closest lieutenants to the cadre of skilled workers who operated his facilities—was encouraged to jot down diagrams and ideas. Particularly good ideas would be initialed by the experimenter in charge of the project and then developed further by the group, making it impossible to assign the credit for an invention to any one creator. "One of Edison's greatest overlooked talents," the historian Greg Field argues, "was his ability to assemble teams and set up an organizational structure that fostered many people's creativity."

This is not to imply that Edison's opinion carried no more weight than that of any other collaborator. A large, burly figure with piercing eyes and a bristling intolerance for laziness, he was very much the commander leading the charge for innovation. Typically he would surge forth on his own course of research, dashing off ideas and conducting experiments seemingly as fast as they came to mind. Once the groundwork for an invention had been laid, he would leave the details to others. The frequent notes of assistants duly recorded the master's advice: "Mr Edison says the temp is to[o] high." "Edison says this is good brick."

In addition to tapping the creative juices of his staff, Edison was knowledgeable about the research of competitors. Contrary to public perception, he almost never worked on any invention that wasn't already being pursued by several other people. What set him apart from his peers was his knack for transforming those ideas into practical results.

The Edison Papers team has been able to find little evidence to support the view that inspiration again and again struck Edison like lightning bolts out of the blue. Take Edison's widely repeated account of a carbon-filament light bulb that burned forty hours straight as his associates watched, transfixed by the miracle. That episode, dramatized in a Hollywood film starring Spencer Tracy as the great inventor, never really happened. Scrutinizing the notebooks from that period, the scholars discovered that the bulb burned only fifteen and a half hours. According to Paul Israel, a historian preparing a biography of Edison based on the archival endeavor, the team's version of that exciting event became inflated after subsequent tests of other carbon-filament materials confirmed the general approach. "The whole 'Eureka!' story arose afterward, probably because they needed a date for the anniversary of the electric light," Israel theorizes. "So they cast their minds back, and suddenly a fifteen-hour bulb became a forty-hour bulb."

A casual reading of Edison's notebooks leaves one with the impression that Eureka! moments were frequent in the laboratory. That's because Edison tended to become wildly enthusiastic about virtually any quirky or unaccountable phenomenon—from the unexpected deflection of a galvanometer needle during an electrical experiment to his discovery on his daily walk around the lab grounds of a bug emitting an unusual odor (this so fascinated the inventor that he wrote to Charles Darwin about it). Yet the project team can identify only a few Eureka! moments that actually had valuable results over Edison's long and illustrious career, and only one—the discovery of the principles behind the phonograph—that deserves the mythic importance with which the public invests such events.

A classic spinoff, the phonograph emerged unbeckoned from work on telegraphs and telephones. In the interest of efficiency, the American mode of telegraphy used receiving instruments that produced a series of clicks, which operators mentally translated into letters. The clicks themselves left no lasting trace. In 1876 Edison and his associates developed a telegraph recorder that would emboss a message on paper, so that it could be transmitted repeatedly at high speed and a receiving operator could rerun it more slowly for transcription. One July day in 1877 Edison considered using a very similar technique for recording telephone messages. The next day he realized that he could dispense with the electrical message, directly emboss the vibrations of the original sounds, and replay them for a simulacrum of the speaker's voice. This flash of insight paved the way for the modern recording industry.

Why, given that major inventions seldom emerge as revelations, was Edison so effective? The Edison Papers Project scholars can point to attitudes, work habits, and methods of reasoning that clearly contributed to his prolific output.

In Israel's view, perseverance was a cornerstone of Edison's strength. This idea is captured in his famous proclamation, "Invention is ninety-nine percent perspiration, and one percent inspiration." In Victorian-era America, of course, hard work and determination were commonly invoked to explain the self-made man. But the recent scholarship casts doubt on the inventor's clever but ultimately facile account of his own genius, addressing such fundamental issues as what enabled him to push ahead in the face of numerous setbacks and how exactly he learned from failure.

Edison could not conceive of any experiment as a flop. As Israel puts it, "He saw every failure as a success, because it channeled his thinking in a more fruitful direction." Israel thinks that Edison may have learned this attitude from his enterprising father, who was not afraid to take risks and never became undone when a business venture crumbled. Sam Edison would simply brush himself off and embark on a new moneymaking scheme, usually managing to shield the family from financial hardship. Israel says, "This sent a very positive message to his son—that it's okay to fail—and may explain why he rarely got discouraged if an experiment didn't work out." In addition to teaching him what wouldn't work, Israel says, failed experiments taught him the much more valuable lesson of what would work—albeit in a different context.

Very few challenges failed to yield to Edison's brute intelligence, but one that did ultimately defeat him was the undersea telegraph. To help his experiments, Edison designed a laboratory model of a transatlantic cable, in which cheap powdered carbon was used to simulate the electrical resistance of thousands of miles of wires. Alas, the rumble of traffic outdoors, clattering in the machine shop, or even the scientists' footsteps shook the equipment enough to change the pressure of the connecting wires on the carbon, thus altering its resistance. Since the accuracy of the model depended upon constant resistance in the carbon, Edison finally abandoned this approach. But later, when confronted with the problem of how to improve the transmission of voices over the telephone, he used a funnel-shaped mouthpiece to focus sound waves on a carbon button. The pressure of those vibrations altered the resistance in the circuit in synchrony with the speaker's voice. In other words, what ruined Edison's underwater-telegraphy experiments is exactly what made his telephone transmitter such a triumph. Indeed, this innovative transmitter rendered Alexander Graham Bell's telephone practical—so much so that it remained the industry standard for a century.

Edison viewed even disasters as an opportunity for learning. On one occasion his lab stove went out in the dead of winter, causing an assortment of expensive chemicals to freeze. On another occasion unprotected chemicals were damaged by sunlight. Instead of bemoaning the losses, Edison put aside all other projects to catalogue changes in the properties of the bottled substances. Keith Nier observes, "He knew how to turn lemons into lemonade."

In his memoirs, and certainly before the press, Edison projected the image of a no-nonsense workaholic. In various respects he lived up to this reputation, often working as many as 112 hours a week. His second wife, Mina, had a cot set up in a corner of his library so that he could take catnaps in a more dignified manner than stretching out on the laboratory bench, as had been his habit. Yet this hard-driving man also had a childlike sense of curiosity and a fun-loving streak that could not always be contained in his rush to meet deadlines and achieve goals.

Perhaps the most delightful document yet unearthed by the project editors is one that captures a giddy moment in the lab during a marathon work spell, when Edison and his colleagues behaved with the goofy abandon of high school kids set loose in chemistry class. Searching for a liquid with specific properties for an electrochemical device, they tried caraway oil, clove oil, oregano oil, nitrogen chromate, and peppermint oil. But as night stretched on into the wee hours of the morning, they adopted a more freewheeling approach. The next notebook entry records that they tested coffee, eggs, sugar, and milk.

Breakfast was scarcely the most exotic material to be harnessed during the course of experimentation. Whale baleen, a tortoise shell, elephant hide, and the hair of a native Amazonian are just a few of the items collected by Edison in his obsessive quest for compounds with unique properties. One of his colleagues joked that his lab storeroom held everything, including "the eyeballs of a US senator." Although most of these substances had no practical applications, a few did. Rain-forest nuts were compressed into bricks from which Edison made phonograph needles. Japanese bamboo was fashioned into a filament for his commercial light. As for the Amazonian's hair, it came in handy as a wig for the first talking doll, in whose chest was concealed a tiny phonograph speaker.

Just as the inventor played with materials, he played with ideas, suspending his critical faculties during the earliest stages of invention. In an era before photocopying machines he developed an electric "pen"—really a puncturing device that rapidly punched holes in a sheet of waxed paper, which then served as a stencil for generating more copies. To make the point of the pen vibrate up and down, Robert Rosenberg, the project director, reports, Edison came up with concepts that "ranged from the practical to the absurd." Rosenberg reviewed a series of drawings showing how the point might be set in motion by a treadle mechanism reminiscent of an early Singer sewing machine, by little waterwheels attached to the end of the shaft, by air pumps, or by an electric motor tethered to the operator's wrist.

Part of the impetus for Edison's dogged search for alternative solutions to problems was his wish to cover himself with as broad a patent as possible. But the project historians emphasize that Edison also simply exulted in the challenge of inventing. It was a test of his ingenuity—almost a matter of pride—to see how many possibilities he could come up with.

Although he cast a wide net initially, Edison would gradually become more focused in his thinking. As his understanding of a problem grew, he typically devised theories, tested them, and then narrowed the range of potential solutions. Still, his inventive process at no stage resembled the linear, step-by-step progression that the scientific method is supposed to be. Just when he appeared to be putting the finishing touches on an invention, Edison would often go back and review his earlier sketches to see if, in the light of the new knowledge he had acquired, abandoned ideas could be resurrected.

A single page from Edison's notebooks beautifully captures his remarkable facility for mixing and matching concepts. It shows three different designs for recording sound, from the time Edison first displayed his phonograph. Those pictures foretell the main directions the recording industry would take throughout the first half of the twentieth century.

One sketch, illustrating the design Edison went on to market commercially, shows a stylus pressed against a cylinder resembling a rolling pin. The so-called "cylinder phonograph" derived directly from a cylinder version of his recording telegraph. A second drawing features a grooved disc not unlike an LP record; it sprang from the basic version of his telegraph recorder, the device that led to the discovery that sound could be captured on paper or foil. The third drawing foreshadows the tape recorder, with paper tape running under a stylus. The project scholars believe that Edison got this idea from his work on earlier printing and chemical telegraph systems, which had similar configurations.

A closely related observation of the scholars—one with exciting implications for school-based programs aimed at cultivating innovative minds—is that Edison employed similar problem-solving strategies across numerous technologies. Notably, he reasoned by analogy, with a distinctive repertoire of forms, models, and design solutions that he applied to invention after invention. Reese Jenkins, who assembled and until last year headed the Edison Papers Project staff, calls these repeating motifs in Edison's work "theme and variations."

To illustrate Edison's brand of logic, Jenkins holds up one of his first drawings of the kinetoscope, a prototype motion-picture camera. "Notice any similarity to his wax-cylinder phonograph?" he asks.

The resemblance is obvious. Both phonograph and kinetoscope consist of an axle supporting a cylinder that has information (either a sound recording or a sequence of still photos) wound along its length. Each device also has a long thin instrument (a stylus in the case of the phonograph and a viewing apparatus in the case of the kinetoscope) held perpendicular to the surface of the cylinder.

Not surprisingly, these forms had a common origin. While Edison was working on an improved model of the phonograph in 1888, Jenkins reports, he was paid a visit by the photographer Eadweard Muybridge, who brought with him some of his famous still photos of animals in motion. Inspired by these images, Edison began to think about developing a moving picture in tandem with his other project. Jenkins finds evidence of a conceptual link between the two inventions in a patent caveat Edison drafted later that year, in which he announced, "I am experimenting upon an instrument which does for the eye what the phonograph does for the ear." He went on to describe the parallel between the spiral of images that make up what we now call film and the spiral grooves on the phonograph record.

The motion-picture camera that evolved from Edison's kinetoscope ultimately abandoned the cylinder in favor of reels of film, thus concealing from generations of scholars its close kinship to the phonograph. "If we hadn't looked at his notebooks and draft caveats," Jenkins points out, "we'd never know what the original impetus for the idea was."

The Edison papers have brought to light another dimension of the inventor's success: the brilliant scientist was also a clever businessman, and capable of engineering literally dazzling public-relations stunts. In a bid to get New York City to allow its streets to be torn up for the laying of electrical cables, Edison invited the entire city council out to Menlo Park at dusk. He directed the aldermen up a narrow staircase in the dark, and as they grumbled and fumbled their way, he clapped his hands. On came a flood of lights, illuminating a lavishly set dining hall complete with a sumptuous feast catered by Delmonico's, then New York's premier restaurant.

Edison knew how to use the rumor mill to enhance his professional image. He portrayed his younger self as having been a guileless rube who didn't know what to do with a check for $40,000 that he received shortly after arriving in New York. The story—originally told by Edison is that after cashing the check, he stuffed the bills into the lining of his coat. Edison loved to tell this fabricated tale, possibly because it fit nicely with that era's image of the wild, enterprising Yankee.

Edison the private man is not nearly as scintillating as Edison the inventor and self-promoter. "He had few of the endearing eccentricities commonly associated with genius," Greg Field says, expressing an opinion also held by his colleagues. Edison was in many respects a typical Victorian man, with solid midwestern tastes. Like many of his contemporaries, he was sheltered from women in his youth, and he seems to have been genuinely chagrined to discover that his partner in marriage would not be his partner at the laboratory bench. Just over a month after marrying Mary Stilwell, the twenty-four-year-old Edison despaired in a notebook, "My wife Dearly Beloved Cannot invent worth a Damn!!" He also shared with Americans of his background stereotypical prejudices against Jews, Poles, Irishmen, and other newly arriving immigrant groups (though ethnic biases apparently never stopped him from hiring anyone he deemed talented).

As he advanced in years, he became increasingly protective of his discoveries. Lisa Gitelman, a project historian, recently uncovered an irate letter (circa 1916) from Edison to his manufacturing department. It had been prompted by the news that teenagers were turning up the speed of his cylinder phonograph to make the music faster. Instead of capitalizing on this trend, Edison complained, "This change of speed is far worse than any loss due to having dance records too slow … They are absolutely right time but young folks of the family want this fast time & like stunts & I dont want it & wont have it." To make sure his will was obeyed, he ordered his machinists to make a governor for the motor.

Of course, next to Edison's accomplishments, his shortcomings seem puny. Even among other hallowed figures in the pantheon of inventors, Edison is Bunyanesque. What Henry Ford is to the automobile, George Eastman to photography, and Charles Goodyear to rubber, Edison is to not one but several of today's essential technologies.

Is the Edison Papers Project helping to demystify his genius? "His ability to reason by analogy and to learn from failure are certainly examples of traits that should be useful to people of all sorts of talents and occupations," Paul Israel says. "Nonetheless, when you see his mind at play in his notebooks, the sheer multitude and richness of his ideas makes you recognize that there is something that can't be understood easily that we may never be able to understand."

About the Author

More Stories

Liberals and Conservatives React in Wildly Different Ways to Repulsive Pictures

How Your Cat Is Making You Crazy

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Thomas Edison

By: History.com Editors

Updated: October 17, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

Thomas Edison was a prolific inventor and savvy businessman who acquired a record number of 1,093 patents (singly or jointly) and was the driving force behind such innovations as the phonograph, the incandescent light bulb, the alkaline battery and one of the earliest motion picture cameras. He also created the world’s first industrial research laboratory. Known as the “Wizard of Menlo Park,” for the New Jersey town where he did some of his best-known work, Edison had become one of the most famous men in the world by the time he was in his 30s. In addition to his talent for invention, Edison was also a successful manufacturer who was highly skilled at marketing his inventions—and himself—to the public.

Thomas Edison’s Early Life

Thomas Alva Edison was born on February 11, 1847, in Milan, Ohio. He was the seventh and last child born to Samuel Edison Jr. and Nancy Elliott Edison, and would be one of four to survive to adulthood. At age 12, he developed hearing loss—he was reportedly deaf in one ear, and nearly deaf in the other—which was variously attributed to scarlet fever, mastoiditis or a blow to the head.

Thomas Edison received little formal education, and left school in 1859 to begin working on the railroad between Detroit and Port Huron, Michigan, where his family then lived. By selling food and newspapers to train passengers, he was able to net about $50 profit each week, a substantial income at the time—especially for a 13-year-old.

Did you know? By the time he died at age 84 on October 18, 1931, Thomas Edison had amassed a record 1,093 patents: 389 for electric light and power, 195 for the phonograph, 150 for the telegraph, 141 for storage batteries and 34 for the telephone.

During the Civil War , Edison learned the emerging technology of telegraphy, and traveled around the country working as a telegrapher. But with the development of auditory signals for the telegraph, he was soon at a disadvantage as a telegrapher.

To address this problem, Edison began to work on inventing devices that would help make things possible for him despite his deafness (including a printer that would convert electrical telegraph signals to letters). In early 1869, he quit telegraphy to pursue invention full time.

Edison in Menlo Park

From 1870 to 1875, Edison worked out of Newark, New Jersey, where he developed telegraph-related products for both Western Union Telegraph Company (then the industry leader) and its rivals. Edison’s mother died in 1871, and that same year he married 16-year-old Mary Stillwell.

Despite his prolific telegraph work, Edison encountered financial difficulties by late 1875, but one year later—with the help of his father—Edison was able to build a laboratory and machine shop in Menlo Park, New Jersey, 12 miles south of Newark.

With the success of his Menlo Park “invention factory,” some historians credit Edison as the inventor of the research and development (R&D) lab, a collaborative, team-based model later copied by AT&T at Bell Labs , the DuPont Experimental Station , the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) and other R&D centers.

In 1877, Edison developed the carbon transmitter, a device that improved the audibility of the telephone by making it possible to transmit voices at higher volume and with more clarity.

That same year, his work with the telegraph and telephone led him to invent the phonograph, which recorded sound as indentations on a sheet of paraffin-coated paper; when the paper was moved beneath a stylus, the sounds were reproduced. The device made an immediate splash, though it took years before it could be produced and sold commercially.

Edison and the Light Bulb

In 1878, Edison focused on inventing a safe, inexpensive electric light to replace the gaslight—a challenge that scientists had been grappling with for the last 50 years. With the help of prominent financial backers like J.P. Morgan and the Vanderbilt family, Edison set up the Edison Electric Light Company and began research and development.

He made a breakthrough in October 1879 with a bulb that used a platinum filament, and in the summer of 1880 hit on carbonized bamboo as a viable alternative for the filament, which proved to be the key to a long-lasting and affordable light bulb. In 1881, he set up an electric light company in Newark, and the following year moved his family (which by now included three children) to New York.

Though Edison’s early incandescent lighting systems had their problems, they were used in such acclaimed events as the Paris Lighting Exhibition in 1881 and the Crystal Palace in London in 1882.

Competitors soon emerged, notably Nikola Tesla, a proponent of alternating or AC current (as opposed to Edison’s direct or DC current). By 1889, AC current would come to dominate the field, and the Edison General Electric Co. merged with another company in 1892 to become General Electric .

Later Years and Inventions

Edison’s wife, Mary, died in August 1884, and in February 1886 he remarried Mirna Miller; they would have three children together. He built a large estate called Glenmont and a research laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey, with facilities including a machine shop, a library and buildings for metallurgy, chemistry and woodworking.

Spurred on by others’ work on improving the phonograph, he began working toward producing a commercial model. He also had the idea of linking the phonograph to a zoetrope, a device that strung together a series of photographs in such a way that the images appeared to be moving. Working with William K.L. Dickson, Edison succeeded in constructing a working motion picture camera, the Kinetograph, and a viewing instrument, the Kinetoscope, which he patented in 1891.

After years of heated legal battles with his competitors in the fledgling motion-picture industry, Edison had stopped working with moving film by 1918. In the interim, he had had success developing an alkaline storage battery, which he originally worked on as a power source for the phonograph but later supplied for submarines and electric vehicles.

In 1912, automaker Henry Ford asked Edison to design a battery for the self-starter, which would be introduced on the iconic Model T . The collaboration began a continuing relationship between the two great American entrepreneurs.

Despite the relatively limited success of his later inventions (including his long struggle to perfect a magnetic ore-separator), Edison continued working into his 80s. His rise from poor, uneducated railroad worker to one of the most famous men in the world made him a folk hero.

More than any other individual, he was credited with building the framework for modern technology and society in the age of electricity. His Glenmont estate—where he died in 1931—and West Orange laboratory are now open to the public as the Thomas Edison National Historical Park .

Thomas Edison’s Greatest Invention. The Atlantic . Life of Thomas Alva Edison. Library of Congress . 7 Epic Fails Brought to You by the Genius Mind of Thomas Edison. Smithsonian Magazine .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

COMMENTS

The Thomas A. Edison Papers Project, a research center at Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences, is one of the most ambitious editing projects ever undertaken by an American university. For decades, the 5 million pages of documents that chronicle the extraordinary life and achievements of Thomas Alva Edison remained hidden and inaccessible to ...

Edison and his associates used ledger volumes, pocket notebooks, and unbound scraps of paper on an irregular basis throughout the inventor's career. In 1877, however, Edison instituted a more regular practice for note keeping that, with some refinements, continued throughout his life.