- PUBLICATIONS

- RESTORATIONS

© 2021 RAA. All rights reserved.

RESEARCH ON ARMENIAN ARCHITECTURE U.S.A.

| Type | Booklet |

| Title | RESEARCH ON ARMENIAN ARCHITECTURE U.S.A. |

| Project Author | Armen Hakhnazarian |

| Brief Information | The booklet presents the activity of the RAA (Research on Armenian Architecture) Organization, especially focusing on its goals and publications. |

Privacy Preference Center

Privacy preferences.

You are in a modal window. Press the escape key to exit.

Quick Links

- Kazan Visiting Professor

- Minor Requirements

- Upcoming Courses

- Scholarships

- Armenian Students Organization (ASO)

- News and Events

- Churches of Historic Armenia

- Arts of Armenia

- Armenian Architecture

- Armenian Publication Series

- Library and Photo Archive

- Grants and Projects

- Armenian Art-Miniatures

- Fresno Institute for Classical Armenian Translation (FICAT)

Armenian Studies Program

Arts of Armenia-Architecture

ARCHITECTURE, FIRST OF THE ARTS

Of all the arts, architecture is supreme. For the general public used to visiting museums filled with paintings of compact size easily hung by the hundreds, the priority given to architecture in the art world may seem strange. But buildings are not susceptible to display in museums, when reduced to photos or models, they seem pale next to the immediate beauty of original art works. Thus, architectural monuments are only accessible to the public by distant travel or through specialized books. Art historians have always put architecture in a different category; they have measured the value of monuments by standards other than those appropriate to smaller decorative creations in whatever medium.

So, too, in the realm of Armenian art, architecture takes pride of place. It was the first of the arts of Armenia to be seriously studied, and to this day Armenian architecture receives more scholarly attention than all of the other arts combined. The separateness of architecture from the other arts is not due just to size, though certainly the immense mass of any building compared to other works of art is so disproportionate that no real comparison is possible, nor to the labor, in the case of architecture perforce collective, required for its creation. Because buildings are natural vehicles for decoration, they differ from other art objects by often incorporating in themselves the two most important of the other arts: painting and sculpture.

SHAPES OF BUILDINGS

In the study of architecture, however, primary attention is not given to the decoration, but to the structural forms of buildings and their evolution. Thus, monuments are analyzed by their architectural aspects -- the general design or look of the interior and exterior of buildings -- and architectonic considerations -- the methods used to construct them. Classes of buildings are studied by their plans.

Everyone is familiar with certain common types of structures; their names immediately evoke specific images: skyscraper, lighthouse, pyramid, windmill, stadium, Greek temple. Other types of buildings are less precisely visualized, because their forms are diverse: houses and churches, for instance, vary greatly in different parts of the world. They are differentiated architectonically by materials and methods of construction, architecturally by their shape.

The form of a building is expressed by its ground plan. Simply stated, a ground plan, or just plan, is the contour of the walls of any structure with all of its entrances and other openings indicated in an overhead view of the building magically sliced away at ground level. The thickness of the dark black lines, the size of the empty spaces for doors, reflect accurately and to scale the actual size of walls and openings.

A. PRE-CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE IN ARMENIA AND THE PLACE OF THE CHURCH

The history of Armenian architecture is in reality the history of the development of a single type of building: the church. Two observations should come to mind, each raising certain questions. First, since the church is a Christian building for worship, and since Armenia was converted as a national entity in the early fourth century, does that mean that there is no architecture in Armenia before Christianity? No. We know very sophisticated building techniques were in use in Armenia and a strong architectural tradition in stone was exercised for more than a thousand years before the first church was built.

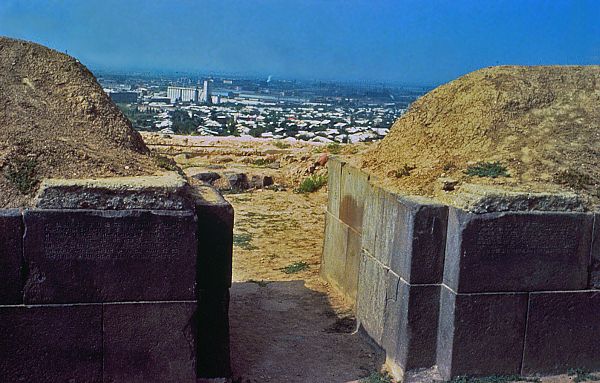

Unfortunately, only a handful of pre-Christian examples has survived and they are from three distinct epochs: Urartian, Hellenistic, and late Roman. They will be discussed briefly in chronological order. A considerable number of temples and fortified garrison cities are known belonging to the kingdom of Urartu (ninth to the sixth centuries B.C.), the most famous examples being the garrisons of Erebuni [1] and Karmir Blur in Soviet Armenia, Toprakkale, the royal capital near Van, and the temple of Mousasir (known from an Assyrian carving). None of these survived above ground; they were all discovered in the past century by archaeological excavations. The kingdom or Urartu itself was forgotten for 2500 years after its destruction in the early sixth century B.C. until it was literally dug up in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Urartian architecture used carefully cut stone often of very large size for the foundations of walls and the supports of wooden columns for temples and assembly rooms. The compact efficiency of such towns as Erebuni [1] , the innovative design of the temple of Mousasir, and the remnants of simple houses with primitive domes points to a flourishing architectural activity. Unfortunately, from the four centuries immediately following the end of the Urartian kingdom, no architectural monuments have been uncovered in Armenia. It is only in the centuries just before the Christian era that our next link in the building tradition of the land is found.

At the site of Garni [ 2, 124 , 164 ], some fifty kilometers northeast of modern Erevan, a number of important constructions survive from three different periods. The oldest is made up of a number of important fragments of a defensive wall around the locality. Dating to the first century before Christ, the wall is made up in parts of enormous monolithic stones carefully carved and placed upon each other without the use of mortar. This technique was known throughout the Middle East in the Roman period. The second period is represented by the splendid, though small, temple of Garni [ 2, 124 , 164 ], following the general design of a Greco-Roman temple so characteristic of the Mediterranean world. There is still some debate concerning the use of the building (temple or summer residence) and its date of construction (first or third century A.D.), but no argument about the elegance of its proportions or the skill of its decorative friezes. The temple remained standing until 1679 when it was destroyed during an earthquake. It was restored in the 1970s and has the distinction of being the only Greco-Roman temple standing above ground in the entire Soviet Union.

The most recent architectural vestige at Garni [ 2 , 164 ] is the bath, probably of the fourth century, excavated and restored like Erebuni [1], Karmir Blur, and the temple of Garni [ 2 , 164 ] with the encouragement and support of the Armenian government. The baths, built of brick and volcanic stone, are small and follow the general layout of Roman baths with a tepidarium, caldarium, and frigidarium (a warm washing room, a steam room, and a cooling room). Since Armenia was pagan for centuries before Christianity, did not other temples exist? Yes, we know of them from the Armenian histories of the fifth century, but as the historians tell us, the first Christians led by St. Gregory and his followers, in their zeal, willfully destroyed all the sanctuaries of the pagan religion, leaving us with an architectural void.

B. ARMENIAN ARCHITECTURE AS CHURCH ARCHITECTURE

Beside these limited ancient examples and the urban architecture of the twentieth century in the Armenia Republic, Armenian architecture is essentially that of church buildings, thus a Christian architecture. Its productive history spans the period from the fourth to the seventeenth century. Though it should be noted that in modern times, especially in the diaspora, churches continued to be built and are now being erected in large numbers, scholars have not yet studied this phenomenon, leaving modern Armenian church architecture rootless and for the moment outside the art historical tradition.

A second observation arising from the idea of Armenian architecture being confined to Christian buildings is the lack of any secular construction. Were there not palaces and fortresses for the kings and catholicoi? Or bridges and caravansaries to accommodate the extensive trade that passed through the country? Did not people live in houses and were not these grouped together in cities? The answer is yes, but few examples have survived. Common dwellings were made of perishable materials, wood, mud brick, or simply dug into the ground or a hillside. The excavations of the medieval capital city of Ani [ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ] made in the beginning of this century, confirm the lack of substantial dwellings that could be considered architectural monuments. Several bridges -- among them Sanahin [ 38 ], twelfth century, Ashtarak, seventeenth century -- and a few caravansaries have survived; they have been brought together in a book by V. M. Harutiunian. The stone foundations of important residences of the catholicos have been excavated at Zvart'nots' [ 17 , 128 ] and Dvin. They date from the sixth and seventh centuries. An extremely large number of fortresses with their inner complex of dwellings, churches, and other buildings was constructed in Greater Armenia, the most famous being Amberd of the tenth century, and, from the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries, in Cilician Armenia, among which the best known are Sis, Lampron [ 37 ], Korykos, Silifke, Anavarza, and Yilankale. A large volume devoted to a general survey of Armenian fortresses was published by the Mekhitarist father M. Hovannisian; recently, Robert Edwards has devoted a detailed study to 75 Cilician Armenian fortresses (see the bibliography for full references to all works cited in this text).

Thousands of Armenian churches were built during the long history of Christianity. They varied in size from very small to large, though there were no giant structures like St. Peters in Rome or Hagia Sophia in Constantinople or the large cathedrals of Europe. Some churches were intended to stand alone, while others were parts of monasteries. A large number of types were developed, providing a great variety of exterior shapes and interior volumes. Some types are found in adjoining Christian areas, but in Armenia their plans were usually modified to conform to local conditions. A number of unique church forms were invented by Armenian architects in their pursuit of ever more efficiently built and aesthetically conceived houses of worship.

1. CLASSIFICATION OF MONUMENTS

The data of architecture, as in any scientific discipline, are studied by arranging what is diverse and heterogeneous into categories based on similarities of features and according to periods. The convenience of this methodology for a coherent discussion of architectural features should never obscure the reality that such labels as medieval, renaissance, modern are made up by scholars, whereas the architects and builders were totally oblivious to such considerations. They erected buildings as they were needed with the material available and in a style either asked for by a patron or within own their competence and preference.

2. FORMATION OF A NATIONAL STYLE

Despite the large diversity in the types of early churches, Armenian architecture achieved a distinctive style through the combination of a number of common characteristics and materials. The compositional employment of these traits was unique to Armenia, though its northern neighboring Georgia was also to benefit by a flourishing of building activity. By the late sixth or early seventh century a unique national style of church architecture came into being. Some scholars have called this phenomenon the first national style in Christian architecture. It had been achieved long before the Byzantine, Romanesque, and Gothic or the less known Ethiopian, Scandinavian, and Slavic styles were concretely formed.

What are the features that make an Armenian church instantly recognizable? First, all churches are built entirely in stone. The scarcity of wood prevented its architectural use in medieval Armenia. With rare exceptions, the stone used is a volcanic tufa abundant in Armenia in many colors and shades: pink, red, orange, black. Dark basalt was also used for more sturdy foundation work. Only in outlying regions of Armenia, where tufa is not readily available, was another stone substituted. In many respects tufa is an ideal material for construction because it is light of weight, easy to sculpt, and has the property of becoming harder and more durable with exposure to air and the passage of time. Second, ceilings were always vaulted. Since wood was not available for making simple flat roofs, stones were employed, but their weight demanded they be arranged in arcs so that the thrust of their mass could be directed to robust stone walls and thence to the ground. This at first produced buildings with thick walls and few and small openings to comfortably accommodate the pressure from above.

Third, the Armenian preference or weakness for the dome manifested itself very early. By the end of the sixth century, a church without a dome was unthinkable. Other than a few early exceptions, the dome or cupola was elevated above the other vaulted ceilings by a cylindrical drum (usually polygonal on the outside). The prevalence of the dome forced architects to think in terms of centrally planned buildings. Fourth, roofs were composite in their appearance because they had to cover the vaults and domes of a complex, though symmetric, group of inner spaces. Like the inner and outer walls and the drum, they too were made of tufa thinly cut into uniform shingles. These are not all the features common to Armenian architecture, rather they are the ones that provide the stylistic likeness so quickly perceived by the eye when looking at Armenian churches. Each church is, however, an individual creation, distinguished by its inner and outer form, its size, and its decoration. Most belong to a certain class of building, though some are unique. Almost all monuments of whatever period have a ground plan elaborated during the first three hundred years of Christianity in Armenia (fourth to seventh centuries) when the creative energies of Armenian architects seemed to overcome all obstacles engendered by construction in stone that sought ever more inner space and less massive structures.

C. THE PERIODIZATION OF ARMENIAN ARCHITECTURE

The historical vicissitudes of the Armenian nation are accurately reflected in the moments of flourishing and decline of its architecture. Four distinct periods of building activity, interspersed by nearly equally long moments of stagnation, mirror the political strength or weakness of Armenia's rulers.

1. The Formative Period (Fourth to the Seventh Centuries)

The first or formative period of Armenian architecture is the most brilliant, a golden age paralleling the golden age of Armenian letters. It is also the longest period starting with the conversion to Christianity in the fourth century, even though few surviving monuments can be dated so early, and ending with the Arab invasion and occupation of Armenia, which, in the mid-seventh century, suddenly destroyed a robust architectural tradition at its zenith. Then two full centuries pass without churches or other monuments being erected in Armenia.

2. The Bagratid Revival (Ninth to the Eleventh Centuries)

The second period begins almost simultaneously with the re-establishment of the Bagratid kingdom in the 880s, very slowly at first, beginning by unashamedly imitating existing structures from the formative period until the techniques forgotten during the lapse of seven or eight generations were again mastered. The tenth and eleventh centuries, under the patronage of the Bagratid kings of Ani and Kars, the Artsrunis of Aght'amar [ 26 , 161 ] and the area around Lake Van and the rulers of Siunik, not only bear witness to a new architectural vigor perfectly at ease with the skills that produced the older forms, but one that began to innovate and experiment in the search for more height and space, for new forms. Like the previous period, this one was also doomed by the sudden loss of political autonomy resulting from the weakening of the Armenian kingdoms by the Byzantine Empire and their final destruction by the invasion of the Seljuk Turks after the mid-eleventh century.

3. The Flourishing of Monasteries (Twelfth to the Fourteenth Centuries)

The beginning of the next period coincided with the independence of Georgia at the end of the twelfth century under queen T'amar and her Armenian generals Ivané and Zakaré. The Armenian Zakarid dynasty provided the necessary security essential for the flourishing of architecture and the construction and expansion of large monastic complexes. From the twelfth century to the fourteenth a new renaissance, encouraged and patronized by large noble families, gave Armenian architecture its last creative moment before the renewed suffering and stagnation of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

4. The Seventeenth Century

The successive invasions of Greater Armenia by Timur Lang at the end of the fourteenth century, coinciding with the destruction of the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia by the Mamluks in 1375, ended architectural activity for nearly 250 years. No new buildings were erected until the seventeenth century and existing structures were barely maintained. In the seventeenth century a final national revival under the rule of the Safavid Shahs of Iran produced a limited series of new constructions [ 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ], the churches at Mughni [ 58 ] and Shoghakat' [ 59 ] at Etchmiadzin are two important examples in Greater Armenia and the churches of New Julfa [ 57 ], the Armenian suburb of Isfahan, are the most famous of diasporan monuments. During this period many older monuments were restored and expanded: Aght'amar [ 26 ], the cathedral of Etchmiadzin [ 3 , 4 ], Hrip'simé [ 13 , 14 ] are among the best known.

5. Modern Armenian Architecture

Innovative architecture after the seventeenth century came to a stop in Armenian proper, but Armenian architecture continued in diasporan cities like Constantinople, Tiflis, and more remote areas such as Singapore. In the second half of the nineteenth century a new architecture development in all Armenian communities was inspired by the national revival. In the years 1915 and after Armenian culture stopped totally in the ancient homeland. The Armenian population in eastern Anatolia was disseminated and the surviving remnants deported. Large numbers of ancient medieval monuments were destroyed. During the same years the Bolshevik revolution and the effects of its anti-religious propaganda after Armenian was made a Soviet Republic in 1920 also resulted in the abandoning of buildings of the cult and occasionally in their destruction.

Only after the Second World War did a demographically expanding and constantly immigrating nation display a need for new church buildings. Everywhere in the diaspora, but especially in the Americas and western Europe, new churches were and are being built. In Armenia the same tendency has been gaining momentum, especially in the 1980s, under the leadership of both the Catholicos of All Armenians, Vazgen I, and the Committee for the Preservation of Monuments, which have undertaken the restoration and even rebuilding of the hundreds of medieval monuments that fall under its jurisdiction. Large numbers of churches and monasteries sequestered by the Soviet regime have been returned to the Catholicos by the new Armenian Republic.

D. METHODS OF CONSTRUCTION

Armenian architects and masons during the first two centuries after the conversion to Christianity developed the characteristic building expertise associated with nearly all Armenian edifices erected after the sixth century. Before tracing the formal steps followed in achieving these results, the building technique itself should be understood. The architectonic problem was singular: How to build churches with complex interior volumes in stone that would both resist the immense weight of the masonry vaulting and roofing and not crumble under the jarring effects of earthquakes. Armenia is a highly volcanic and active seismic land. The lateral movement caused by earth tremors could easily cause the upsetting of the often delicate balance of forces developed to support stone domes. The major solution was the skillful use of concrete, not in the form we know of it today, but similar to that developed in Roman architecture in the Near East, perhaps the original sources from which Armenian artisans borrowed the formula. Buildings were virtually poured into being from the ground up, but instead of the modern usage of wooden forms into which a thick liquid mixture of cement, gravel, and sand -- modern concrete -- is poured, a more integrated method was used.

Onto modern concrete buildings a decorative facing material, often marble, is added later. This external siding is not organically related to the constructional process. In the Armenian case the parallel forms employed to contain the inner core of mortar were finely cut slabs of tufa. Elevated a few rows at a time, these tufa forms adhered permanently to the wet mixture (composed of broken tufa, often of large size, and other stones, lime mortar, and usually eggs) poured in between them. As the binding material dried, it formed a nearly solid, concrete-like mass, which, because of the property of tufa discussed earlier, hardened as time passed.

For architectonic forces, this inner core is the major support, the transmitter of the weight, of vaulted roofs and domes, rather than the carefully carved exterior masonry that we admire. Furthermore, this manner of slowly raising a building was extended above the level of the walls directly into the vaults, the drum, and the dome, giving the whole structure the solidity associated with reinforced concrete of today. The architects employed various innovations to ameliorate constantly the quality of their work, for instance tufa of lesser density or large terra-cotta jars were often used in the core of the domes to reduce their weight.

The facing of inside and outside walls, even though it played a secondary role in support, was executed with great care. There was an aesthetic consideration that played with the natural beauty of tufa in two principal ways. Often the entire building would be made with tufa of exactly the same color and hue. The perfectly cut stone was usually laid one upon the other without the use of mortar. To give some buildings a perfectly unified and singular look, tufa of the same color was ground into powder that was then applied along the joints, concealing them and giving an effect of walls without seams. The other major use of tufa was to highlight rather than hide the differences in color. Blocks of contrasting colors were juxtaposed to give checkerboard or other decorative effects.

A more important reason for the care devoted to the tufa walls was protection against earthquakes. Shocks to a building, usually in a rocking motion, could precipitate the detaching and falling away of blocks of stone from the inner core. By beveling the tufa slabs, varying their size and height, and breaking up the straight vertical and horizontal lines of successive rows, a very resistant surface cohesion was produced. Nevertheless, after more than a thousand years some medieval Armenian churches abandoned for centuries to the elements and vandalism stand today as though naked with only their inner concrete core intact. The outer stones have either fallen away or willfully pried loose by present day villagers in search of ready-made building materials for their homes.

Once perfected, this method of construction became the standard into modern times. Its evolution was cautiously nurtured by several generations of builders in the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries who were confronted by the challenge of patronage from all parts of the newly converted Armenia. The land became an experimental workshop for architecture just as that experienced by the Roman Empire after its acceptance of Christianity in the same fourth century. Armenian architects, by rejecting the use of wood for roofing as in neighboring Syria and the more easily manipulated brick so popular in the Roman and Byzantine Empires to the west, confronted the ungrateful task of all stone construction with persistence and genius. The earlier churches of whatever design were characterized by the use of heavy and thick stone for walls, often with mortar placed between joints. The inner core was so narrow that the real work of supporting the superstructure was performed by the walls themselves. Gradually in the fifth and sixth centuries, as the masons saw that the domes and vaults of earlier buildings were steadfast and resistant to shock, the blocks of stone became thinner and the inner core of mortar wider. Eventually large stone blocks were reserved for the lowest courses and for the corners where two walls met. By the end of the sixth century the confidence of architects was such that windows and other openings were added to edifices, while domes became bigger and interior management of space more audacious. Some domes did suffer design weaknesses, a few had to be rebuilt, but on the whole, as the numerous extent monuments erected more than a thousand years ago eloquently testify, the work of Armenian craftsmen was executed to last for eternity.

E. THE FORMS OF ARMENIAN ARCHITECTURE

In the early period, so much innovation took place, so many architectural experiments were being carried out simultaneously, that it is impossible to conceive the historical progression of Armenian monuments in a strictly linear fashion. There was, however, in certain areas of development, as for instance the working out of the concrete core technique outlined above, a roughly describable forward movement. The rest of this essay, in introducing the various monuments illustrated in the photographic compliment which accompanies it, will be devoted to an explanation of the major types of church buildings used in Armenia.

1. The Basilica and the Single Nave Church

The earliest church structures in Armenia were the basilicas, of which at least seven have survived [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. All have three aisles. There was also a more simple variant, the hall church with a single aisle (Lernakerd [ 5 ]). Great numbers of these single nave churches were constructed from the fourth to the sixth centuries. They are of varying size and are found throughout the country. Some varieties have a room for liturgical purposes adjoining the apse (Karnut, Diraklar), and sometimes a covered porch on one side (Tanahat and at Garni and Dvin). Variations of the pure basilican plan include a nave ending in a salient or protruding apse and side aisles with apses such as Kasagh [ 8 ], Eghvard, and Dvin; with the addition of two chambers flanking the apse, which of course is no longer salient, as Ashtarak, Tziranavor, and Tsiternavank' [ 7 ]; with covered porches on the north and south and chambers at the east as Tekor, or chambers at both ends as Ereruk [ 6 ].

Since the dating of most Armenian basilicas is approximate, no certain chronological progression according to type can be determined. Armenian basilicas are similar to the Syrian variety, and like so many early Christian doctrines and practices the basilican form must have entered Armenia from that southern neighbor. There are, however, characteristic differences. Armenian basilicas are built in stone and almost without exception have stone vaults over aisles and naves, whereas in Syria, though walls and apses are of stone, roofs are generally unvaulted and wooden like Byzantine and Roman counterparts. A single roof covers both central and side aisles in most Armenian basilicas, while in Syria and the West the central nave usually has a separate and higher roof.

2. Domed Basilica and Domed Single Nave Church

The Armenian fondness for vaulting and the dome soon resulted in the transformation of both the single hall church and three-aisled basilica (a form considered alien to Armenia) to a domed building in which the cupola served as the focal point. By the late fifth or early sixth century the basilica of Tekor was modified by the addition of a dome over the central bay of the nave; in the first quarter of the next century the basilican cathedral of Dvin was also changed in this manner. Coterminously, perhaps starting as early as the fifth century at Zovuni, single aisle churches with a central dome resting on massive piers jutting out from the north and south walls were constructed (Ptghni [ 9 ], sixth century; Talish or Aruch', seventh century; and after the ninth century, Marmashen [ 28 ], Amberd, 126 [30], St. Mariam at Bjni [ 31 ] and the church of Tigran Honents' [ 36 , 163 ] at Ani. In the seventh century, basilicas were built similar to Tekor with domes resting on four central, free-standing pillars: Odzun [ 20 , 126 ], Bagavan, Mren, Gayané [ 15 , 16 ], Talin [ 19, 125 ], and the famous cathedral of Ani (989-1001) [ 33 , 34 ]. At this stage, however, the term basilica no longer entirely fits the last group, for if we remove the eastern end with apse and side chambers of the churches of Mren and Gayané [ 15 , 16 ], we are left with a nearly square interior of nine bays, the central one bearing the dome.

3. Central Plan

Truly centrally planned domed churches of varying models were built during the sixth and seventh centuries and perhaps even as early as the late fifth century during the reconstruction of Etchmiadzin [ 3 , 4 ] itself. At Agarak there is a tetraconch or quatrefoil church composed of four salient apses, joined without intervening walls, supporting a dome. Another series of well-known cruciform chapels and churches of small dimensions has an exterior plan in the shape of a Greek cross with arms of equal length forming an outside tetraconch (Mankanots', St. Sarkis at Bjni [ 23 ], and Tarkmanch'ats'), or with the same exterior and only one apse at the east end (Karmravor [ 21 ] and Lmbatavank'), or with an extended western arm and three interior apses forming a trefoil (St. Anania at Alaman and St. Mariam at Talin [ 22 ]).

4. Niche-buttressed Square

Another variant of the quatrefoil, what Josef Strzygowski called the niche-buttressed square, has four apses protruding from the middle of each of the four walls of a square; the weight of the centrally placed dome is absorbed by these four protruding niches that buttress the walls. All such churches have a pair of chambers added to the sanctuary; one type has a dome resting on four free-standing pillars with pendentives (masonry corners in the shape of spherical triangles) which form a circular base as a transitional element for a cylindrical drum. The most famous examples are Etchmiadzin [ 3 , 4 ] and Bagaran. Another type features a dome that covers the entire interior and rests on an octagonal base and drum formed by the walls and four corner squinches (arches): Mastara [ 10 ], Artik [ 18 ], Voskepar, and the church of the Holy Apostles at Kars [ 25 ].

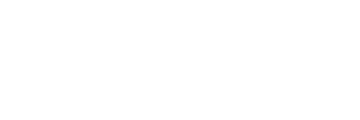

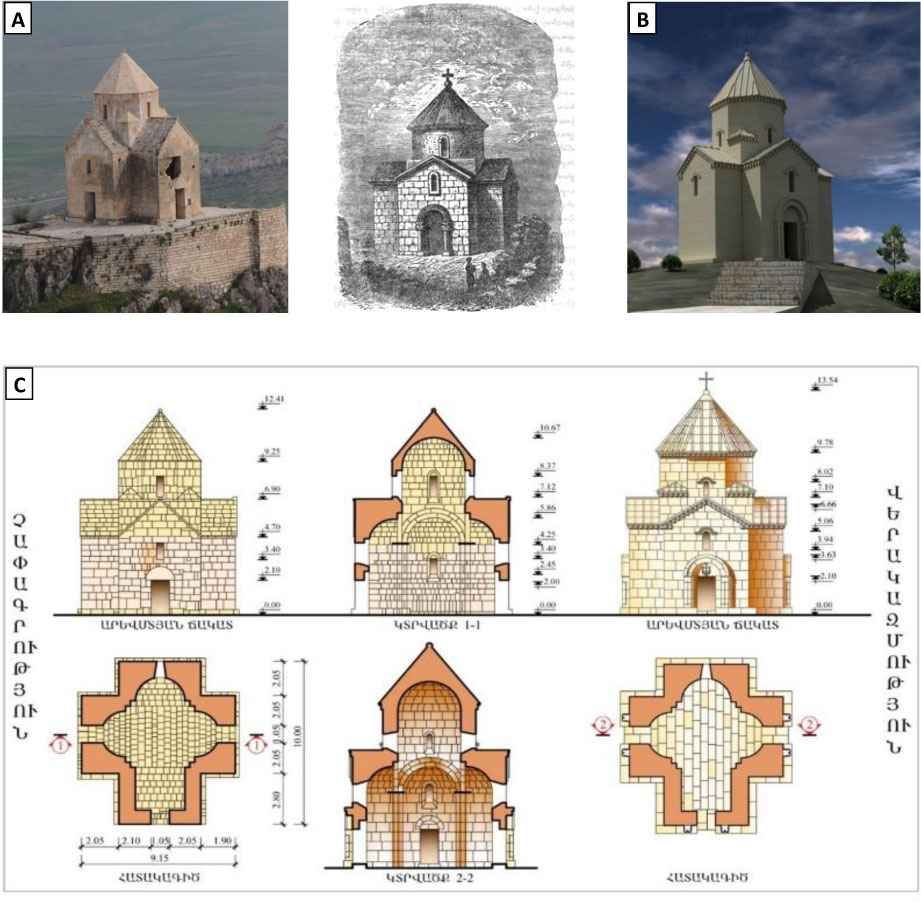

5. Hrip'simé Type

The most developed central plan and the one considered most uniquely Armenian (or Caucasian, since early examples are also found in Georgia) is the radiating or Hrip'simé type [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 26 ], which takes its name from the most famous example, the church of St. Hrip'simé [ 13 , 14 ] built in 618 at Etchmiadzin. The oldest dated monument with this form, however, is the church at Avan (591-609) [ 11 ] near Erevan, though some Italian scholars suggest that the church at Soradir [ 12 ] east of Lake Van may be an even earlier sixth century prototype. The basic plan of the Hrip'simé type is an interior tetraconch, that is interior apses joined to form a four leaf clover shape. At the intersection of these apses in each of the corners are deep circular niches (three-quarter cylinders), which, with the four apses themselves, create an octagonal base as a support for a high cylindrical drum. This in turn is crowned by the usual dome.

Leading off the corner niches are four chambers, either circular in shape (Avan [ 11 ]) or more usually square (Hrip'simé [ 12 , 13 , 14 ] and Sisian). This very symmetrical plan allows a proportionally large interior space to be created, unhindered by columns or piers. Since, however, this complex inner space is enclosed in massive stone walls, the exterior of the building in Armenian architecture, often does not reflect the contour of the interior. The high drum supporting the dome is pierced by windows to admit light into the large central space; windows on other walls are relatively small.

Each of the façades of Hrip'simé [ 13 , 14 ] and Sisian are indented by pairs of deep triangular slits, which place in relief the otherwise hidden inner tetraconch. Only the exterior of Soradir [ 12 ] (and the tenth century church of Aght'amar [ 26 ], which copies the Soradir [ 12 ] plan minus the corner chambers) to some degree has an exterior that reflects the interior articulation.

6. Circular Plan

The ultimate design in the centralized plan is of course the perfectly circular church. In the seventh century, the aisled tetraconch of Zvart'nots' [ 17 , 128 ] perfected the circular plan. The church is really thirty-two sided. Its domed quatrefoil interior reached some forty meters in height. The inner ground space, according to the most recent reconstruction of S. Mnats'akanian, was surrounded by a single tiered ambulatory with open passages leading into the center through an arcade formed of six columns on each of the north, west and south lobes of the tetraconch. This impressive building erected by Catholicos Nersés III between 641 and 653 had an overall diameter equal to its height. Other circular churches of the seventh century include the octafoils of Zoravar and Irind. The plan of Zvart'nots' [ 17 , 128 ] itself was later imitated in both Georgia and Armenia, the best known example being a near replica of it in the eleventh century church Gagikashen at Ani, which like Zvart'nots' [ 17 , 128 ] itself is now destroyed. Among later circular plans is the church of St. Sargis at Khtzkonk' [35] and the hexafoils of the Shepherd's church and St. Gregory Abughamrents' at Ani.

7. The Gavit' or Jamatun

By the mid-seventh century Armenian architecture developed most of its basic forms. During the various architectural renaissances of the medieval period, these forms were imitated and elaborated. One exception was the newly developed narthex, called a gavit' or jamatun in Armenian [ 43 ]. These special square halls were usually attached to the western entrance of churches. They were very popular in monastic complexes where they served as meeting rooms and vestibules. The twelfth to the fourteenth centuries was a period of great expansion of monasteries (in Armenian vank'), which in times of danger also housed neighboring villagers. Pairs of large intersecting arches [ 41 ], held up by four sturdy and squat columns, supported the roofs of jamatuns. Their intersection in the upper region of the hall created an open lantern for light and air. The walls were massive and contained few and small windows. Excellently preserved examples are found at Haghbat [ 41], Sanahin [ 43 ], Geghart [ 45 , 135 ], Goshavank' [ 49 ], Magaravank' and Hovhannavank' [ 46 ].

F. Contemporary Church Architecture

Modern Armenian architecture, especially in church design, is extremely dependent on the ancient tradition. Most new buildings either consciously imitate the most famous monuments of the fourth to the seventh centuries, substituting contemporary constructional advances like reinforced and poured concrete for the traditional Armenian methods, or they combine features -- either tectonic or decorative -- from several old churches with results that are often a hybrid amalgam. Unfortunately, despite the large number of Armenian architects in Armenia and the diaspora and the many opportunities for new church design, innovation and inspiration seem lacking. The willingness of Armenian architects and masons of the past to constantly experiment with new forms has given way to conservative contemporary church boards and architects who seem afraid to deviate from the ancient and glorious tradition.

- Last Updated Feb 9, 2022

Adriano Alpago Novello and Research on Armenian Architecture in Iran

- First Online: 04 January 2022

Cite this chapter

- Marco G. Brambilla 9

Part of the book series: Research for Development ((REDE))

153 Accesses

In studies of Armenian architecture, many extraordinary scholars contributed to the research, documentation, and exploration of Armenian architecture. Adriano Alpago Novello was undoubtedly one of the most accomplished experts of Armenian architecture. His contributions to this specialized field of studies will always remain milestones in the path of research on Armenian architecture. This essay will explore the academic and scientific aspects of the research programs implemented by Alpago Novello and the human element of this outstanding individual. The present article will further try to provide an insight into the challenging and exacting conditions of the field trips conducted by Alpago Novello, this author, and their team in the late 70s in rural North-Western Iran, a territory dominated mainly by the Kurdish population often in conflict with the central government of the time. In addition, due credit shall be given to other scholars who worked directly or indirectly with Alpago Novello and ultimately enriched the body of research on Armenian architecture.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Colonial Past and Neocolonial Present: The Monumental Arch of Tadmor-Palmyra and So-called Roman Architecture in the Near East

Migrating architectures: Palladio’s legacy from Calcutta to New Delhi

Drawing Modernity

Architettura Medievale Armena (1968) In: De Luca (ed) Catalog of the exhibition. Palazzo Venezia, Rome, Italy

Google Scholar

Cuneo P (1988) In: De Luca (ed) Architettura Armena. Rome

Documents of Armenian Architecture, (1988) Sorhul, vol 20. Oemme Edizioni, Milano

Ieni G, Zekyan L (eds) (1975) Atti del Primo Simposio Internazionale di Arte Armena. Bergamo 28–30 Giugno, San Lazzaro, Venezia

Kouymjian D (April 2018) Armenian studies past to present. Hrand Dink Foundation Publication, Istanbul

Novello A, Brambilla et al (1977, 1978) Iran I and Iran II, Milano

Novello AA (1987) The Armenians. Rizzoli, New York

Zekyan BL (ed) (1988) Quinto Simposio Internazionale di Arte Armena. San Lazzaro, Venezia

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of California, Los Angeles, USA

Marco G. Brambilla

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Retired, Former Member of Dipartimento di Architettura e Studi Urbani, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy

Maurizio Boriani

Dipartimento di Architettura e Studi Urbani, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy

Mariacristina Giambruno

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Brambilla, M.G. (2021). Adriano Alpago Novello and Research on Armenian Architecture in Iran. In: Boriani, M., Giambruno, M. (eds) Architectural Heritage in the Western Azerbaijan Province of Iran. Research for Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83094-6_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83094-6_2

Published : 04 January 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-83093-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-83094-6

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The Armenian Highland, the Homeland of Armenians

TO THE ARMENIAN HIGHLAND

About Research on Armenian Architecture Foundation

The purpose of Research on Armenian Architecture Foundation is to find, study and document monuments of Armenian material culture through fieldwork carried out throughout Historical Armenia. The foundation also conducts studies in Diasporan Armenian settlements.

In 1978 Doctor of Architecture Armen Hakhnazarian founded Research on Armenian Architecture NGO in Aachen, Germany.

In 1996 Research on Armenian Architecture NGO opened a branch in Los Angeles, CA, USA, with Shahen Harutiunian as its director.

In 2000 Research on Armenian Architecture NGO opened a branch in Yerevan, Republic of Armenia, with Monumentologist Samvel Karapetian as its director.

In 2010 Research on Armenian Architecture NGO was re-registered as a foundation.

Monuments on MAP

Faithful to its goals, Research on Armenian Architecture Foundation has been carrying out fieldwork throughout Historical Armenia for more than half a century to document and study monuments of Armenian material culture and raise awareness of them. Thanks to these activities, the foundation has rich, systematized archives of 650,000 images, microfilms, plans, maps and other materials.

CALOUSTE GULBENKIAN FOUNDATION

RA Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sport

RA Ministry of Foreign Affairs

AT THE SMITHSONIAN

Unfurling the rich tapestry of armenian culture.

This year’s Smithsonian Folklife Festival will offer a window on Armenian visions of home

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

Ryan P. Smith

Correspondent

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/e9/07e9c4be-df97-4ca6-a414-d1e967b2da02/armenia3.jpg)

A modestly sized landlocked nation framed by the Black Sea to the west and the Caspian to the east, Armenia links the southernmost former Soviet Socialist Republics with the arid sprawl of the Middle East. Armenia’s own geography is heavily mountainous, its many ranges separated by sweeping plateaus of vivid green. The wind is stiff and the climate temperate, and the mountainsides teem with archaeological treasures of a long and meandering history.

Thousands of years ago, the land known as Armenia was roughly seven times the size of the current country. Yet even within the borders of contemporary Armenia, cathedrals, manuscript repositories, memorials and well-worn mountain paths are so dense as to offer the culturally and historically curious a seemingly endless array of avenues to explore.

This year, the Smithsonian Folklife Festival will be bringing deeply rooted Armenian culture to Washington, D.C. From food and handicrafts to music and dance, the festival, taking place in late June and early July, will provide an intimate look at an extremely complex nation. Catalonia , the autonomous region of northeast Spain, is featured alongside Armenia .

What exactly makes Armenia’s cultural landscape so fascinating?

Library of Congress Armenia area specialist Levon Avdoyan , Tufts Armenian architecture expert Christina Maranci , and the Smithsonian's Halle Butvin , curator of the festival's "Armenia: Creating Home" program explain the many nuances of the Armenian narrative.

What was Armenia’s early history like?

Given its strategic geographical status as a corridor between seas, Armenia spent much of its early history occupied by one of a host of neighboring superpowers. The period when Armenia was most able to thrive on its own terms, Levon Avodyan says, was when the powers surrounding it were evenly matched, and hence when none was able to dominate the region (historians call this principle Garsoïan’s Law , after Columbia University Armenia expert Nina Garsoïan ).

Foreign occupation was often brutal for the Armenian people. Yet it also resulted in the diversification of Armenian culture, and allowed Armenia to exert significant reciprocal influence on the cultures of its invaders. “Linguistically, you can show that this happened,” Avodoyan says. “Architecturally this happened.” He says Balkan cruciform churches may very well have their artistic roots in early Armenian designs.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/89/8a/898a9e8c-059e-4860-8ac0-b12ff03e41a8/armenia1.jpg)

What religious trends shaped Armenia?

It’s hard to say what life looked like in pre-Christian Armenia, Avdoyan admits, given that no Armenian written language existed to record historical events during that time. But there are certain things we can be reasonably sure about. Zoroastrianism, a pre-Islamic faith of Persian origin, predominated. But a wide array of regionally variant pagan belief systems also helped to define Armenian culture.

The spontaneous blending of religious beliefs was not uncommon. “Armenia was syncretistic,” Avdoyan says, meaning that the religious landscape was nonuniform and ever-changing . “The entire pagan world was syncretistic. ‘I like your god, we’re going to celebrate your god. Ah, Aphrodite sounds like our Arahit.’ That sort of thing.”

Armenia has long had strong ties with Christian religion. In fact, Armenia was the first nation ever to formally adopt Christianity as its official faith, in the early years of the fourth century A.D. According to many traditional sources, says Levon Avdoyan, “St. Gregory converted King Tiridates, and Tiridates proclaimed Christianity, and all was well.” Yet one hundred years after this supposedly smooth transition, acceptance of the new faith was still uneven, Avdoyan says, and the Armenian language arose as a means of helping the transition along.

“There was a plan put forth by King Vramshapu and the Catholicos (church patriarch) Sahak the Great to invent an alphabet so that they could further propagate the Christian faith,” he explains.

As the still-employed Greek-derived title “Catholicos” suggests, the Christian establishment that took hold in the fourth century was of a Greek orientation. But there is evidence of Christianity in Armenia even before then—more authentically Armenian Christianity adapted from Syriac beliefs coming in from the south. “From Tertullian’s testimony in the second century A.D.,” says Avdoyan, “we have some hints that a small Armenian state was Christian in around 257 A.D.”

Though this alternative take on Christianity was largely snuffed out by the early-fourth century pogroms of rabidly anti-Christian Roman Emperor Diocletian, Avdoyan says facets of it have endured to this day, likely including the Armenian custom of observing Christmas on January 6.

How did Armenia respond to the introduction of Christian beliefs? With the enshrinement of Christianity came a period characterized by what Avdoyan generously terms “relative stability” (major instances of conflict—including a still-famous battle of 451 AD that pitted Armenian nobles against invading Persians eager to reestablish Zoroastrianism as the official faith—continued to crop up). Yet the pagan lore of old did not evaporate entirely. Rather, in Christian Armenia, classic pagan myth was retrofitted to accord with the new faith.

“You can tell that some of these tales, about Ara the Beautiful , etc., have pagan antecedents but have been brought into the Christian world,” Avdoyan says. Old pagan themes remained, but the pagan names were changed to jibe with the Christian Bible.

The invention of an official language for the land of Armenia meant that religious tenets could be disseminated as never before. Armenia’s medieval period was characterized by the proliferation of ideas via richly detailed manuscripts.

What was special about medieval Armenia?

Armenian manuscripts are to this day world-renowned among medieval scholars. “They’re remarkable for their beauty,” Avdoyan says. Many have survived in such disparate places as the Matenadaran repository in Yerevan, the Armenian Catholic monasteries of San Lazzaro in Venice, and the Walters Art Museum in Maryland.

Historians define “medieval Armenia” loosely, but Avdoyan says most place its origin in the early fourth century, with the arrival of Christianity. Some, like Avodyan, carry it as far forward as the 16th century—or even beyond. “I put it with 1512,” Avdoyan says, “because that’s the date of the first published book. That’s the end of the manuscript tradition and the beginning of the print.”

What sets the manuscripts apart is their uniquely ornate illuminated lettering . “The Library of Congress recently bought a 1486 Armenian gospel book,” Avdoyan says, “and our conservationists got all excited because they noticed a pigment that didn’t exist in any other.” Discoveries like this are par for the course with Armenian manuscripts, which continue to draw academic fascination. “There’s still a lot to be learned about the pigments and styles.”

The structure of life in medieval Armenia was a far cry from what Westerners tend to picture when they hear the term “medieval.” A kind of feudalism did take hold for a time, Avdoyan says, but not that of lordships and knights. “Unlike feudalism in Europe, which was tied to the land,” he notes, “feudalism in Armenia was tied to the office. You had azats , the free, you had the nobles, and in a certain period you had the kings.” For a stretch of Armenian history, these divisions of office were rigidly enforced—everyone knew their place. “But by the ninth century, tenth century, it rather fell apart.”

One facet of Armenia’s medieval period that was more consistent was the majesty of the churches and other religious structures erected all across its mountainous topography. These creations are the focus of medieval Armenian art historian Christina Maranci.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/d4/e6d4f61a-33a9-4963-b95c-fba130f026a3/armenia5.jpg)

Armenians take pride in their historic architecture. Why?

It is something of a rarity for a country’s distinctive architecture to inspire ardent national pride, but Christina Maranci says such is most definitely the case in Armenia. “Many Armenians will tell you about Armenian architecture,” she says. To this day, engineering is a highly revered discipline in Armenia, and many study it. “A lot of Armenians know very well how churches are built, and are proud of that.”

Maranci says that what makes Armenian art history so fascinating to study, even before the medieval period, is its simultaneous incorporation of outside techniques and refinement of its native ones. Before Christianity, she says, “you have what you would traditionally consider to be Near Eastern art—Assyrian art, Persian—but you also have evidence for Mediterranean classical traditions, like Hellenistic-looking sculpture and peristyles. Armenia provides a very useful complication of traditional categories of ancient art.”

But later architecture of the region—particularly the Christian architecture of the medieval period—is what it is best known for today.

How far back can we trace Armenian architecture?

With the dawn of national Christianity, Byzantine and Cappadocian influences began to take hold. And places of worship began to dot the land. “The first churches upon the conversion of Armenia to Christianity are largely basilicas,” Maranci notes. “They’re vaulted stone masonry structures, but they don’t use domes for the most part, and they don’t use the centralized planning” that many later Armenian churches claim as a hallmark.

By the seventh century, though, Maranci explains that Armenia began to embrace its own signature architectural style. “You have the domed centralized plan,” she says, which “is distinctive to Armenia and neighboring Georgia, and is distinct from Byzantine architecture, Syrian architecture and Cappadocian architecture.” Within the span of just a few decades, she says, centrally planned churches came to predominate in Armenia. And “it becomes ever more refined through the tenth century, eleventh century, and so on.”

As important in medieval Armenian church architecture as the churches themselves was their situation amid the natural flow of their surroundings. “The outside of the church was, from what we can tell, used in processions and ceremonies as well as the inside,” Maranci says. “In traditional Armenian churches, you see very clearly the way the church building is related to the landscape. That’s another piece that’s important.”

Many of these elegantly geometric models have endured in Armenian architecture through to the present day. Yet Maranci says that the Hamidian Massacres of the 1890s and the Armenian Genocide of 1915 to 1922 have exerted undeniable influences on Armenian architecture and art more broadly. “The recovery of medieval form now has to be mediated through this trauma,” she says. Modern Armenian art often subverts medieval forms to illustrate the annihilating effect of the bloodshed.

Moreover, since many Armenians emigrated out of the nation during or in the wake of these dark periods, diasporic Armenians have had to come up with their own takes on the traditional in new, unfamiliar environs. “You can see how American churches use prefab forms to replicate the Armenian churches,” she says by way of example. In lieu of Armenia’s incredibly sturdy rubble masonry technique—which dates back nearly two millennia—American communities have made do with plywood, drywall and reinforced concrete, improvising with their own materials yet staying true to the ancient architectural layouts.

What is significant about the Armenian diaspora(s)?

Many have heard the phrase “Armenian diaspora,” generally used as a blanket term to encompass those Armenians who fled the region around the time of the genocide and other killings. During and after World War I, an estimated 1.5 million Armenians were killed—the Turkish government, for its part, disputes the death toll and denies that there was a genocide.

Avdoyan notes that, really, there was no one diaspora, but rather many distinct ones across a wide stretch of history. By using the singular term “diaspora,” Avdoyan believes we impute to the various immigrant groups of Armenia a sense of cohesion they do not possess.

“There is no central organization,” he says. “Each group has a different idea of what it means to be Armenian. Each one has a feeling that their Armenian-ness is more genuine or more pure. And it’s also generational.” The Armenians who fled the genocide have identities distinct from those of emigrants who left Armenia after the Lebanese Civil War, and distinct in a different way from those of the emigrants who have left Armenia since it secured its independence from the Soviet Union in 1990. Avodoyan hopes that one day all the different diasporic generations will be able to come together for a cultural conference.

What aspects of Armenian culture will the Folklife Festival be highlighting?

Between the rich artistic and religious history of the Armenian homeland and the various cultural adaptations of diasporic Armenian populations worldwide, the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage had its work cut out for it in selecting elements of Armenian culture to showcase at this year’s Folklife Festival. The Folklife team settled on two major themes to explore—feasting and craft. These will be presented through the lens of home, an essential concept throughout the Armenian narrative.

On every day of the festival, which runs from June 27-July 1 and July 4-July 8, a dedicated “demonstration kitchen” will hold hourly presentations of Armenian recipes in action. Festival curator Halle Butvin calls special attention to Armenian methods of preserving food: “cheesemaking, pickling, making jams and drying herbs and fruits.”

The demonstration kitchen will also be showing off recipes featuring foraged foods, in honor of the self-sufficient food-gathering common in mountainous Armenia, as well as foods tied to the time-honored ritual of coming together for feasting: “Armenian barbecue, tolma, lavash, cheese, different salads. . . some of the major staples of an Armenian feast.”

Linked to feasting is Armenia’s dedication to its national holidays. “Vardavar, a pagan water-throwing tradition takes place on July 8 and Festivalgoers will get a chance to participate,” Butvin says. She says celebrants can expect to learn how to make such treats as gata (sweet bread), pakhlava (filo pastry stuffed with chopped nuts) and sujukh (threaded walnuts dipped in mulberry or grape syrup) for the occasion.

Diasporic Armenian eats will be prepared as well as time-honored homeland fare. Since “Armenian cultural life really does revolve around the home,” Butvin says, “we’ll have the whole site oriented around that, with the hearth—the tonir —at the center.”

Tonirs , the clay ovens in which Armenian lavash bread is cooked, are traditionally made specially by highly skilled Armenian craftsmen. One such craftsman will be on site at the Folklife Festival, walking visitors through the process by which he creates high-performance high-temperature ovens from scratch.

Another featured craft which speaks to the value Armenians place on architecture is the stone carving technique known as khachkar. Khachkars are memorial steles carved with depictions of the cross, and are iconic features of Armenian places of worship. Visitors will get hands-on exposure to the art of khachkar, as well as other longstanding Armenian specialties like woodcarving and rugmaking.

Musically, guests can expect a piquant blend of Armenian jazz and folk tunes. Butvin is looking forward to seeing the camaraderie between the various acts in the lineup, who all know one another and will be building on each other’s music as the festival progresses. “They will play in different groupings,” Butvin says—guests can expect “a lot of exchanges and influences taking place between the artists.”

And what would music be without dance? Butvin says the dance instruction component of the Folklife Festival will tie in thematically with the feasting traditions emphasized among the culinary tents. “Usually you eat, drink, listen to music, and then dance once you’re feeling a little tipsy,” Butvin says. “That’s kind of the process of the feast.”

The emphasis of the Armenian portion of the festival on home and family will contrast well with the Catalonian activities’ stress on street life. “The whole Catalonian site is focused around the street and the plaza and this public space,” Butvin says, “whereas the Armenia side is really focused on the home itself. It will be an interesting difference, to look at the two.”

Butvin is hopeful the festival will show visitors the wonders of Armenian culture while also impressing upon them the degree to which it has spread and evolved all over the globe. “All of these different objects and traditions help to create a sense of home for Armenians,” she says—even those Armenians “who are in diaspora, who are trying to hold on to this sense of Armenian-ness.”

The Smithsonian Folklife Festival takes place on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., June 27 to July 1, and July 4 to July 8, 2018. Featured programs are "Catalonia: Tradition and Creativity from the Mediterranean" and "Armenia: Creating Home."

Get the latest on what's happening At the Smithsonian in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

Ryan P. Smith | READ MORE

Ryan graduated from Stanford University with a degree in Science, Technology & Society and now writes for both Smithsonian Magazine and the World Bank's Connect4Climate division. He is also a published crossword constructor and a voracious consumer of movies and video games.

- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Architecture News

Design in Armenia: New Architecture Building on History

- Written by Eric Baldwin

- Published on May 04, 2020

The architecture of Armenia responds to both past traditions and the country's earthquake-prone geography. Known for medieval churches, Armenia has also become home to modern projects that reinterpret familiar construction methods and organizational principles. Acknowledging a reputation for sturdy concrete and stone structures, the country's contemporary architects are experimenting with different materials to create lighter and more open structures.

Historic buildings in Armenia feature thick walls and low-slung profiles, usually made of a readily available material like stone. From ancient geometric groundwork to massive rock walls, the country's built environment dates back millennia. This history was continuously influenced by regional cultures and religions, and more recently, by large building projects. Beyond the country's borders, the Armenian diaspora led to sacred architecture and churches to be constructed around the world. The following projects look back into the country itself to examine the new buildings and architecture built over the last ten years.

Dilijan Central School by Storaket Architectural Studio

The building of “Dilijan Central School” is located in the city of Dilijan. In recent years the education sphere in Dilijan is under development, which is evidenced by the creation of Dilijan International School and Scientific Research Center of Central Bank of Armenia. Dilijan Central School is intended for the children of employees of these two institutions, which serves as an elementary and middle school.

UWC Dilijan College by Tim Flynn Architects

One of the main goals of the UWC College Dilijan project was to create an Armenian international school that is a lot more than a typical school by integrating the complex of modern buildings into the natural historical environment. The famous Armenian tufa and local stone were used as the main building materials, while eco-friendly “green” walls and roofs were used for school’s main building.

BigBek Office by snkh studio

The office of Armenian software development company BigBek is located in Yerevan ’s Soviet era automotive manufacturing plant called ErAZ, which is now transforming into office spaces for Armenia ’s intensively growing IT community. The main goal of this project was to create an open workspace for up to 30 employees with a strict functional division in only 177 square meters.

American University of Armenia Renovation by Storaket Architectural Studio

The old building of the American University of Armenia (AUA) in Yerevan was built in 1979 by two of the most prominent Armenian architects of the time, Mark Grigoryan and Henrik Arakelyan. The building has a symmetric triangular shape with a light colored facade, a conceptual approach to balance its formal mass. Through this renovation project, an interior was created, where the old and the modern meet to create a reciprocal harmony.

Ayb Middle School by Storaket Architectural Studio

The C building was designed for the current elementary school, and in the future, will be utilized for Ayb Middle School. The building is situated in front of the A and B buildings with a capacity to accommodate 240 students. Just as in the first two buildings, the C building’s architectural philosophy lies in creating an open and collaborative educational environment that is multi-functional.

TS Apartment by snkh studio

T.S. apartment is located in the neighborhood of Yerevan - Cascade, in a neoclassical building. A small balcony of the bedroom is the only point that overlooks the Cascade, where during the warm days, a lot of open air concerts are held. The client wanted a bedroom that could easily transform so he could host friends to enjoy the concerts.

Smart Center by Studio Paul Kaloustian

Targeting rural regions, the Smart Centers are made to respect the integrity of rural aesthetics in sync with contemporary architectural design, maintaining the authenticity of the region, while encouraging progressive ideology. Each campus is made to utilize sustainable and green design, off the grid components and renewable energy. They have classrooms, health posts, studios, computer lounges, meeting points, an auditorium for performances and presentations, libraries, restaurants and various spaces for diverse indoor and outdoor activities.

- Sustainability

想阅读文章的中文版本吗?

亚美尼亚建筑合集,走进历史的新建筑

You've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

Building Armenia: the secret to modern architecture with ancient roots

The architecture of Armenia responds both to past traditions, and the country’s earthquake-prone geography. Acknowledging a reputation for sturdy concrete, stone structures and medieval churches, the country’s contemporary architects are experimenting with different materials to create lighter and more open structures.

Historic buildings in Armenia feature thick walls and low-slung profiles, usually made of a readily-available material like stone. From ancient geometric groundwork to massive rock walls, the country’s built environment dates back millennia. This history was continuously influenced by regional cultures and religions, and more recently, by large Soviet building projects. Beyond the country’s borders, the Armenian diaspora led to sacred architecture and churches to be constructed around the world. The following projects look back into the country itself to examine the new buildings and architecture built over the last ten years.

Dilijan Central School by Storaket Architectural Studio

Dilijan Central School. Image: Sona Manukyan and Ani Avagyan

Education in the Armenian city of Dilijan has been developing rapidly in recent years, with the creation of both the Dilijan International School and the Scientific Research Center of Central Bank of Armenia. The Dilijan Central School is intended for the children of employees at both institutions, and serves as an elementary and middle school.

UWC Dilijan College by Tim Flynn Architects

UWC Dilijan College. Image: Daniil Kolodin

UWC College Dilijan was built with hopes to integrate a complex of modern buildings into the city’s natural historical environment. The famous Armenian tufa, a soft volcanic rock, was used as a main building material along with local stone, while eco-friendly “green” walls and roofs were also used for school’s main building.

BigBek Office by snkh studio

BigBek Office. Image: Sona Manukyan and Ani Avagyan

The office of Armenian software development company BigBek is located in Yerevan ’s Soviet-era automotive plant ErAZ — now transformed into office space for Armenia ’s growing IT community. The project’s main goal was to create an open workspace for up to 30 employees with a strict functional division in a space of just 177 square metres.

American University of Armenia Renovation by Storaket Architectural Studio

American University of Armenia. Image: Sona Manukyan and Ani Avagyan

The old building of the American University of Armenia (AUA) in Yerevan was built in 1979 by two of the most prominent Armenian architects of the time, Mark Grigoryan and Henrik Arakelyan. The building has a symmetric triangular shape with a light-coloured facade, a conceptual approach to balance its formal mass. Through this renovation project, an interior was created that would allow the old and the modern meet and create a reciprocal harmony.

Ayb Middle School by Storaket Architectural Studio

Ayb Middle School. Image: Sona Manukyan and Ani Avagyan

This building was designed for the area’s current elementary school, but in future will be utilised for Ayb Middle School. The building is situated in front of the A and B buildings with a capacity to accommodate 240 students. Just as in the first two buildings, the C building’s architectural philosophy lies in creating an open and collaborative educational environment that is multi-functional.

TS Apartment by snkh studio

TS Apartment. Image: Sona Manukyan and Ani Avagyan

TS Apartment is located close to the Yerevan Cascade, in a neoclassical building. The bedroom’s small balcony overlooks the Cascade monument itself, where during the warm days, open air concerts are held. The client wanted a bedroom that could easily transform so that he could host friends to enjoy these concerts.

Smart Centre by Studio Paul Kaloustian

Smart Centre. Image: Ieva Saudargaite

Targeting rural regions, Smart Centres are designed to respect the integrity of rural aesthetics in sync with contemporary architectural design, maintaining the authenticity of the region while encouraging progressive ideology. Each is made to utilise sustainable and green design, off-the-grid components and renewable energy. The centres themselves have classrooms, health posts, studios, computer lounges, meeting points, an auditorium , libraries, restaurants, and various spaces for indoor and outdoor activities.

Get to know Armenian culture with contemporary folk beats, political documentaries and surreal novels

Eastern Bloc architecture: 50 buildings that defined an era

How Slovakia’s Soviet ties led to a unique form of sci-fi architecture

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Armen Kazaryan

Public Views

MONOGRAPHIES

- 1 Organized conferences, sessions and seminars

- 1 Other

- 1 Conference Organization and Presentations

- 2 Books

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Journals

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Article Contents

Proceedings of the 4th international conference on architecture: heritage, traditions and innovations (ahti 2022).

This article discusses the parts of Ghevond Alishan's fundamental works related to architectural heritage. Our goal was to reveal the approaches and research methods that Alishan the Armenologist was guided by when presenting the architectural heritage. All the types of architectural monuments and groups of monuments (such as settlements, cities, fortresses, people's houses, monastic complexes, churches, engineering structures) to which the great scientist referred were observed. The article singles out the important directions of architectural heritage research. The important mission of Alishan's research, both for its time and in general, in the archiving, comprehensive research, popularization and transmission of the Armenian architectural heritage has been appreciated.

1. INTRODUCTION

Ghevond Alishan has a special place among the grateful people of Armenian architectural science. The issue of comprehensive research on Armenian architecture has received constant attention and discussion in the works of Alishan. He is one of the founders of the School of Armenology and was of the opinion that there is no history without geography and chronology, and that architecture does not exist without space and environment.

The great Armenologist dedicates all his potential to the region – to the Armenian world and landscape – in which inseparable parts are architectural monuments and whose history Alishan presents in his works.

Many researchers have referred to Alishan's life and activities. Starting with the Mekhitarists (Simon Yeremyan, Arsen Ghazikyan, priest Leon Zekiyan, etc.), then also the biographers, historians and literary critics of the Soviet-Armenian period (Ashot Melkonyan, Edik Minasyan, Suren Shtikyan, Irma Safrazbekyan, Aelita Dolukhanyan, etc.) referred to his literary and historical work. The materials related to Armenian architecture published in “Bazmavep” were coordinated and classified by David Kertmenjyan [ 1 ] and Ashot Grigoryan discussed the ecological mystical perceptions of Ghevond Alishan [ 2 ].

The aim of the presented examination was to reveal the approaches and research method by which Alishan the Armenologist was guided in presenting the architectural heritage. In order to achieve the goal, the basic works of Alishan were read in detail, the parts where the Armenian architectural heritage is presented were separated. They are systematized and presented as part of the theory of Armenian architecture. Both the study of world architecture and the development of Armenian architectural science had at its roots bibliographies and topographies, which were the basis for new developments in the theory and history of 19th century architecture, providing a transition to modern manifestations of architectural thought.

Naturally, in this development, the mission of Alishan's research to archive Armenian architectural heritage, comprehensive research, popularization, and passing it on to future generations may play a role.

2. ALISHAN'S INNOVATIVE METHOD OF REPRESENTATION OF ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE AND RESTORATION OF MONUMENTS

From the beginning, Alishan presented the geography and history of Armenia together with a general description of historical and architectural monuments and antiquities. Unlike previous researchers (A. Kostandyants, M. Taghiadyan, S. Jalalyants, M. Barkhudaryan), who wrote their works during their travels based on the rich and factual materials collected by travelers (Tavernie, Zh. Chardin, I. Chopin, etc.), Alishan made his multifaceted descriptions of Armenia, literary, historical-geographical generalizations, based solely on in-depth knowledge gained, arguments drawn from various scientific studies and historians. It is noteworthy that the eminent scientist has never been to Armenia, but as a result of large-scale source studies and accumulation of a large scientific resource, he was able to clarify and document many historical-geographical names, describe and locate many antiquities. This, unfortunately, is a possible feature of the scientist Alishan compared to the representatives of the Armenian architectural complexes before that.

He intended to summarize the history-geography of all 15 Armenian worlds in his work “Topography of the Great Armenians”. However, he managed to publish only the works “Shirak”, “Sisuan”, “Sisakan”, “Ayrarat”, which are very valuable works in terms of research of architectural monuments and have become the subject of our discussion.

“The Topography of the Great Armenians” was published in Venice in mid-1855 [ 3 ], which was a great success and was considered by contemporaries (Marie Jean Brosse, Edouard Dulorie) [ 4 ]. The information about the historical-geographical and monuments of Armenia before Alishan was extremely fragmentary, contradictory, rather contradictory than complementary. European-Russian travelers (Tavernier, Chopin, Chardin) provided informal descriptions of several Armenian provinces, including illustrations of 19th-century scientific concepts about Armenia and its culture.

In “Topography of the Great Armenians”, Alishan presents both the natural and cultural landscape of Armenian world. Climatic characteristics of rivers, mountains, different places, scientific descriptions of flora and fauna are an inseparable part of the historical states of Armenia (Vaspurakan, Syunik, Artsakh, Ayrarat, Tayk, etc.) and the historical-geographical description and scientific history of the antiquities (folk houses, Etchmiadzin Cathedral, Van Fortress etc.). This was a completely new approach and a new methodology.

In some cases, the materials in “Topography of the Great Armenians” still have significance today. For us, the information and the picture mentioned in the work about the church near Shushi, which is surely the central dome church of Vankasar in the Askeran region of the Artsakh Republic, which is also known as Tigranakert Church in medieval Armenian sources, were useful to us. Today, it stands on top of a mountain, altered in the 1980s as a result of Azerbaijan's fraudulent “restoration”. The proposal to restore the church was made because of a combination of original measurements, factual evidence, comparative materials (particularly Karashamb, Aylaber, St. Astvatsatsin three-altar churches in Talin), rich medieval cultural layer and architectural complexes of the region. Thus, the whole bankruptcy of the version of considering the material cultural monuments created by the Artsakh part of the Armenian people as Afghan is revealed [ 5 ]. Today, after the second Artsakh war, the church of Vankasar appeared again in the “captivity” of Azerbaijan.