Qualitative Data Coding 101

How to code qualitative data, the smart way (with examples).

By: Jenna Crosley (PhD) | Reviewed by:Dr Eunice Rautenbach | December 2020

As we’ve discussed previously , qualitative research makes use of non-numerical data – for example, words, phrases or even images and video. To analyse this kind of data, the first dragon you’ll need to slay is qualitative data coding (or just “coding” if you want to sound cool). But what exactly is coding and how do you do it?

Overview: Qualitative Data Coding

In this post, we’ll explain qualitative data coding in simple terms. Specifically, we’ll dig into:

- What exactly qualitative data coding is

- What different types of coding exist

- How to code qualitative data (the process)

- Moving from coding to qualitative analysis

- Tips and tricks for quality data coding

What is qualitative data coding?

Let’s start by understanding what a code is. At the simplest level, a code is a label that describes the content of a piece of text. For example, in the sentence:

“Pigeons attacked me and stole my sandwich.”

You could use “pigeons” as a code. This code simply describes that the sentence involves pigeons.

So, building onto this, qualitative data coding is the process of creating and assigning codes to categorise data extracts. You’ll then use these codes later down the road to derive themes and patterns for your qualitative analysis (for example, thematic analysis ). Coding and analysis can take place simultaneously, but it’s important to note that coding does not necessarily involve identifying themes (depending on which textbook you’re reading, of course). Instead, it generally refers to the process of labelling and grouping similar types of data to make generating themes and analysing the data more manageable.

Makes sense? Great. But why should you bother with coding at all? Why not just look for themes from the outset? Well, coding is a way of making sure your data is valid . In other words, it helps ensure that your analysis is undertaken systematically and that other researchers can review it (in the world of research, we call this transparency). In other words, good coding is the foundation of high-quality analysis.

What are the different types of coding?

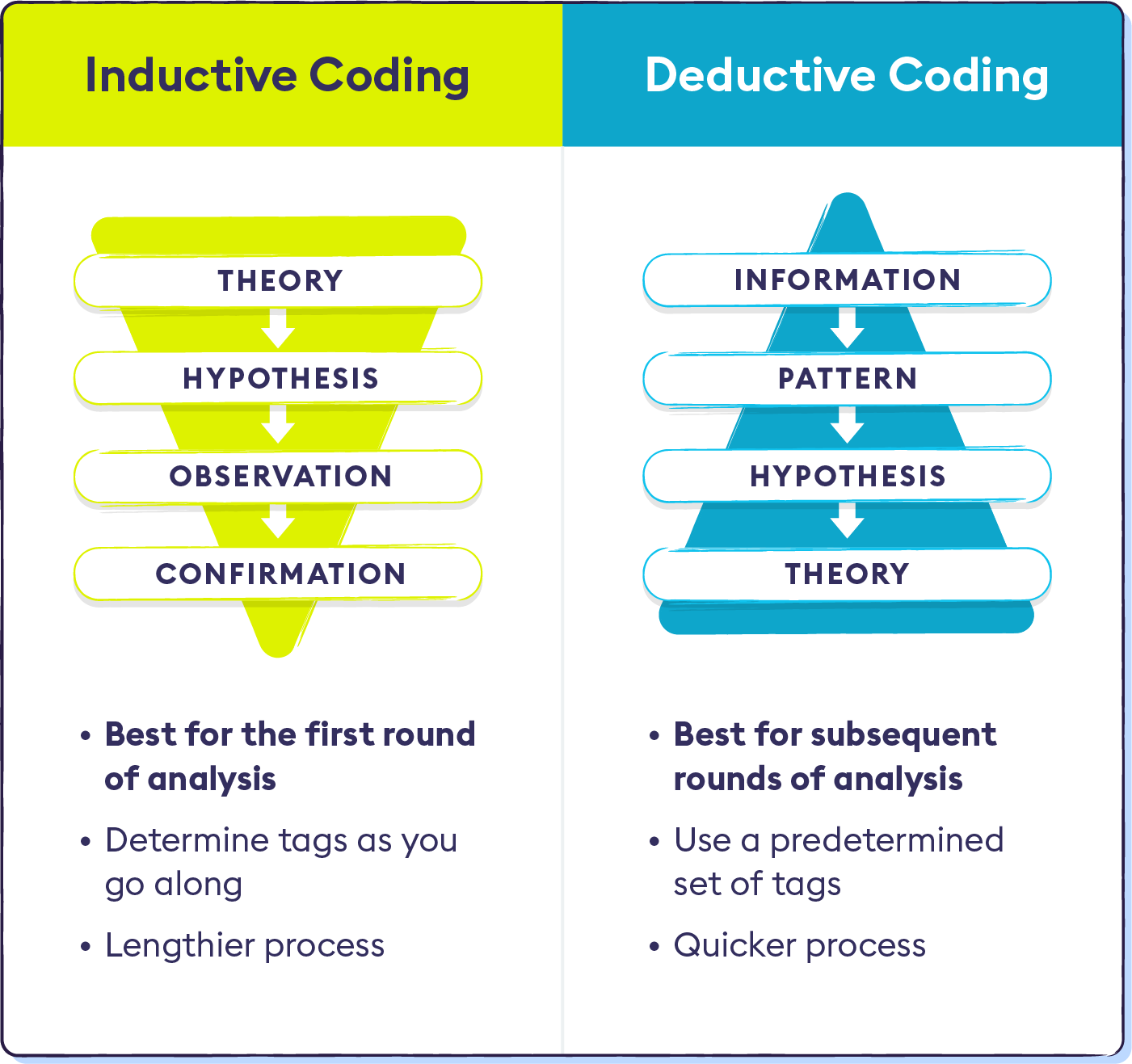

Now that we’ve got a plain-language definition of coding on the table, the next step is to understand what overarching types of coding exist – in other words, coding approaches . Let’s start with the two main approaches, inductive and deductive .

With deductive coding, you, as the researcher, begin with a set of pre-established codes and apply them to your data set (for example, a set of interview transcripts). Inductive coding on the other hand, works in reverse, as you create the set of codes based on the data itself – in other words, the codes emerge from the data. Let’s take a closer look at both.

Deductive coding 101

With deductive coding, we make use of pre-established codes, which are developed before you interact with the present data. This usually involves drawing up a set of codes based on a research question or previous research . You could also use a code set from the codebook of a previous study.

For example, if you were studying the eating habits of college students, you might have a research question along the lines of

“What foods do college students eat the most?”

As a result of this research question, you might develop a code set that includes codes such as “sushi”, “pizza”, and “burgers”.

Deductive coding allows you to approach your analysis with a very tightly focused lens and quickly identify relevant data . Of course, the downside is that you could miss out on some very valuable insights as a result of this tight, predetermined focus.

Inductive coding 101

But what about inductive coding? As we touched on earlier, this type of coding involves jumping right into the data and then developing the codes based on what you find within the data.

For example, if you were to analyse a set of open-ended interviews , you wouldn’t necessarily know which direction the conversation would flow. If a conversation begins with a discussion of cats, it may go on to include other animals too, and so you’d add these codes as you progress with your analysis. Simply put, with inductive coding, you “go with the flow” of the data.

Inductive coding is great when you’re researching something that isn’t yet well understood because the coding derived from the data helps you explore the subject. Therefore, this type of coding is usually used when researchers want to investigate new ideas or concepts , or when they want to create new theories.

A little bit of both… hybrid coding approaches

If you’ve got a set of codes you’ve derived from a research topic, literature review or a previous study (i.e. a deductive approach), but you still don’t have a rich enough set to capture the depth of your qualitative data, you can combine deductive and inductive methods – this is called a hybrid coding approach.

To adopt a hybrid approach, you’ll begin your analysis with a set of a priori codes (deductive) and then add new codes (inductive) as you work your way through the data. Essentially, the hybrid coding approach provides the best of both worlds, which is why it’s pretty common to see this in research.

Need a helping hand?

How to code qualitative data

Now that we’ve looked at the main approaches to coding, the next question you’re probably asking is “how do I actually do it?”. Let’s take a look at the coding process , step by step.

Both inductive and deductive methods of coding typically occur in two stages: initial coding and line by line coding .

In the initial coding stage, the objective is to get a general overview of the data by reading through and understanding it. If you’re using an inductive approach, this is also where you’ll develop an initial set of codes. Then, in the second stage (line by line coding), you’ll delve deeper into the data and (re)organise it according to (potentially new) codes.

Step 1 – Initial coding

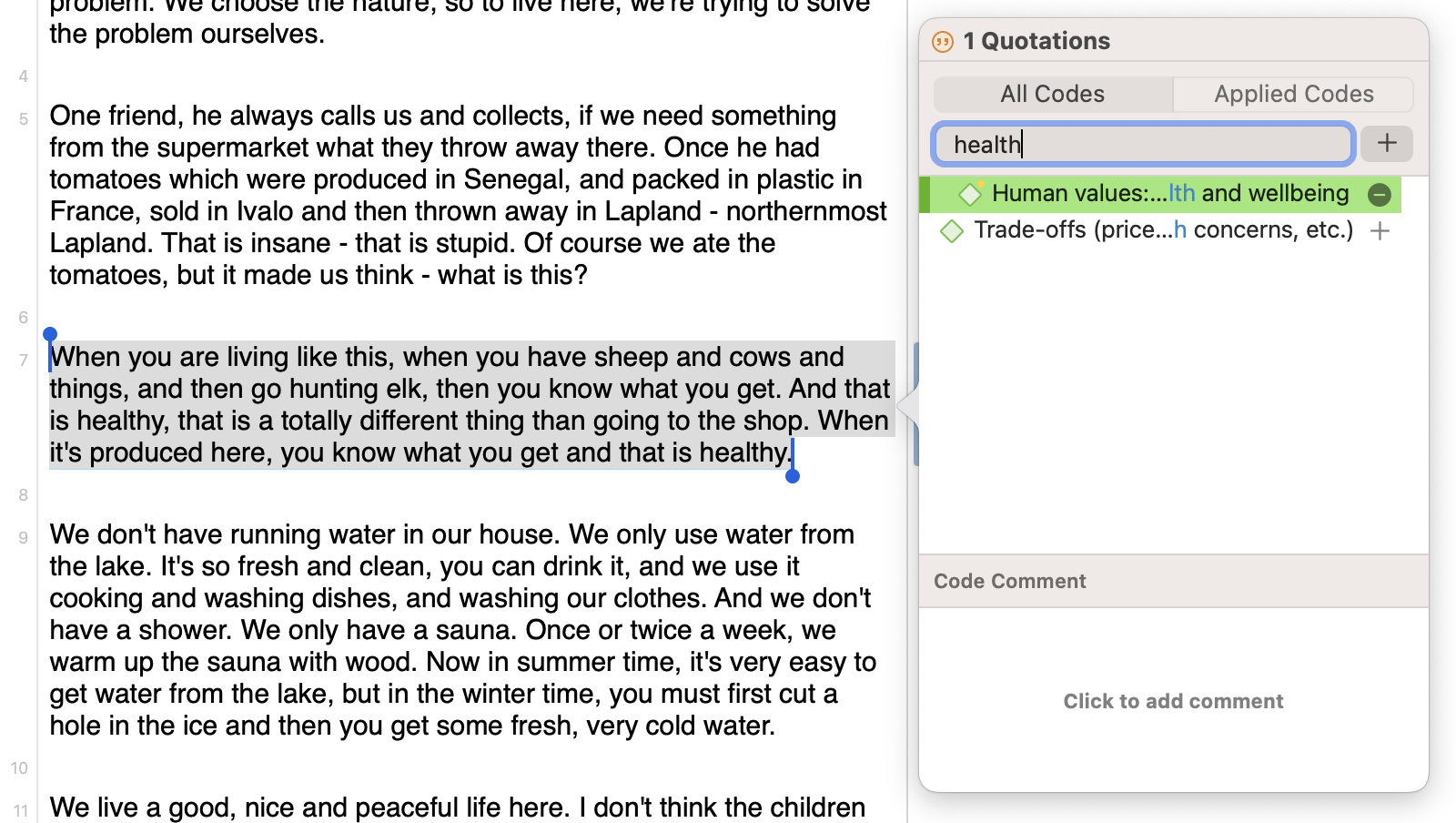

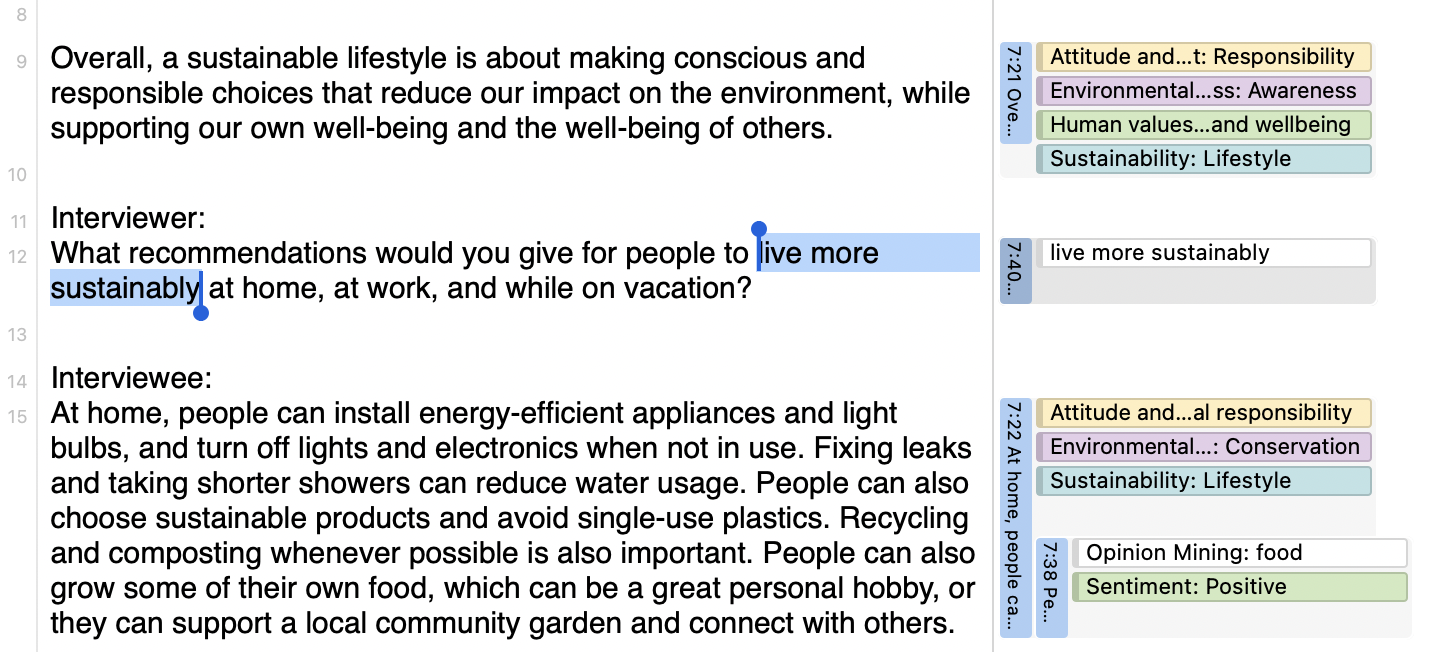

The first step of the coding process is to identify the essence of the text and code it accordingly. While there are various qualitative analysis software packages available, you can just as easily code textual data using Microsoft Word’s “comments” feature.

Let’s take a look at a practical example of coding. Assume you had the following interview data from two interviewees:

What pets do you have?

I have an alpaca and three dogs.

Only one alpaca? They can die of loneliness if they don’t have a friend.

I didn’t know that! I’ll just have to get five more.

I have twenty-three bunnies. I initially only had two, I’m not sure what happened.

In the initial stage of coding, you could assign the code of “pets” or “animals”. These are just initial, fairly broad codes that you can (and will) develop and refine later. In the initial stage, broad, rough codes are fine – they’re just a starting point which you will build onto in the second stage.

How to decide which codes to use

But how exactly do you decide what codes to use when there are many ways to read and interpret any given sentence? Well, there are a few different approaches you can adopt. The main approaches to initial coding include:

- In vivo coding

Process coding

- Open coding

Descriptive coding

Structural coding.

- Value coding

Let’s take a look at each of these:

In vivo coding

When you use in vivo coding , you make use of a participants’ own words , rather than your interpretation of the data. In other words, you use direct quotes from participants as your codes. By doing this, you’ll avoid trying to infer meaning, rather staying as close to the original phrases and words as possible.

In vivo coding is particularly useful when your data are derived from participants who speak different languages or come from different cultures. In these cases, it’s often difficult to accurately infer meaning due to linguistic or cultural differences.

For example, English speakers typically view the future as in front of them and the past as behind them. However, this isn’t the same in all cultures. Speakers of Aymara view the past as in front of them and the future as behind them. Why? Because the future is unknown, so it must be out of sight (or behind us). They know what happened in the past, so their perspective is that it’s positioned in front of them, where they can “see” it.

In a scenario like this one, it’s not possible to derive the reason for viewing the past as in front and the future as behind without knowing the Aymara culture’s perception of time. Therefore, in vivo coding is particularly useful, as it avoids interpretation errors.

Next up, there’s process coding , which makes use of action-based codes . Action-based codes are codes that indicate a movement or procedure. These actions are often indicated by gerunds (words ending in “-ing”) – for example, running, jumping or singing.

Process coding is useful as it allows you to code parts of data that aren’t necessarily spoken, but that are still imperative to understanding the meaning of the texts.

An example here would be if a participant were to say something like, “I have no idea where she is”. A sentence like this can be interpreted in many different ways depending on the context and movements of the participant. The participant could shrug their shoulders, which would indicate that they genuinely don’t know where the girl is; however, they could also wink, showing that they do actually know where the girl is.

Simply put, process coding is useful as it allows you to, in a concise manner, identify the main occurrences in a set of data and provide a dynamic account of events. For example, you may have action codes such as, “describing a panda”, “singing a song about bananas”, or “arguing with a relative”.

Descriptive coding aims to summarise extracts by using a single word or noun that encapsulates the general idea of the data. These words will typically describe the data in a highly condensed manner, which allows the researcher to quickly refer to the content.

Descriptive coding is very useful when dealing with data that appear in forms other than traditional text – i.e. video clips, sound recordings or images. For example, a descriptive code could be “food” when coding a video clip that involves a group of people discussing what they ate throughout the day, or “cooking” when coding an image showing the steps of a recipe.

Structural coding involves labelling and describing specific structural attributes of the data. Generally, it includes coding according to answers to the questions of “ who ”, “ what ”, “ where ”, and “ how ”, rather than the actual topics expressed in the data. This type of coding is useful when you want to access segments of data quickly, and it can help tremendously when you’re dealing with large data sets.

For example, if you were coding a collection of theses or dissertations (which would be quite a large data set), structural coding could be useful as you could code according to different sections within each of these documents – i.e. according to the standard dissertation structure . What-centric labels such as “hypothesis”, “literature review”, and “methodology” would help you to efficiently refer to sections and navigate without having to work through sections of data all over again.

Structural coding is also useful for data from open-ended surveys. This data may initially be difficult to code as they lack the set structure of other forms of data (such as an interview with a strict set of questions to be answered). In this case, it would useful to code sections of data that answer certain questions such as “who?”, “what?”, “where?” and “how?”.

Let’s take a look at a practical example. If we were to send out a survey asking people about their dogs, we may end up with a (highly condensed) response such as the following:

Bella is my best friend. When I’m at home I like to sit on the floor with her and roll her ball across the carpet for her to fetch and bring back to me. I love my dog.

In this set, we could code Bella as “who”, dog as “what”, home and floor as “where”, and roll her ball as “how”.

Values coding

Finally, values coding involves coding that relates to the participant’s worldviews . Typically, this type of coding focuses on excerpts that reflect the values, attitudes, and beliefs of the participants. Values coding is therefore very useful for research exploring cultural values and intrapersonal and experiences and actions.

To recap, the aim of initial coding is to understand and familiarise yourself with your data , to develop an initial code set (if you’re taking an inductive approach) and to take the first shot at coding your data . The coding approaches above allow you to arrange your data so that it’s easier to navigate during the next stage, line by line coding (we’ll get to this soon).

While these approaches can all be used individually, it’s important to remember that it’s possible, and potentially beneficial, to combine them . For example, when conducting initial coding with interviews, you could begin by using structural coding to indicate who speaks when. Then, as a next step, you could apply descriptive coding so that you can navigate to, and between, conversation topics easily. You can check out some examples of various techniques here .

Step 2 – Line by line coding

Once you’ve got an overall idea of our data, are comfortable navigating it and have applied some initial codes, you can move on to line by line coding. Line by line coding is pretty much exactly what it sounds like – reviewing your data, line by line, digging deeper and assigning additional codes to each line.

With line-by-line coding, the objective is to pay close attention to your data to add detail to your codes. For example, if you have a discussion of beverages and you previously just coded this as “beverages”, you could now go deeper and code more specifically, such as “coffee”, “tea”, and “orange juice”. The aim here is to scratch below the surface. This is the time to get detailed and specific so as to capture as much richness from the data as possible.

In the line-by-line coding process, it’s useful to code everything in your data, even if you don’t think you’re going to use it (you may just end up needing it!). As you go through this process, your coding will become more thorough and detailed, and you’ll have a much better understanding of your data as a result of this, which will be incredibly valuable in the analysis phase.

Moving from coding to analysis

Once you’ve completed your initial coding and line by line coding, the next step is to start your analysis . Of course, the coding process itself will get you in “analysis mode” and you’ll probably already have some insights and ideas as a result of it, so you should always keep notes of your thoughts as you work through the coding.

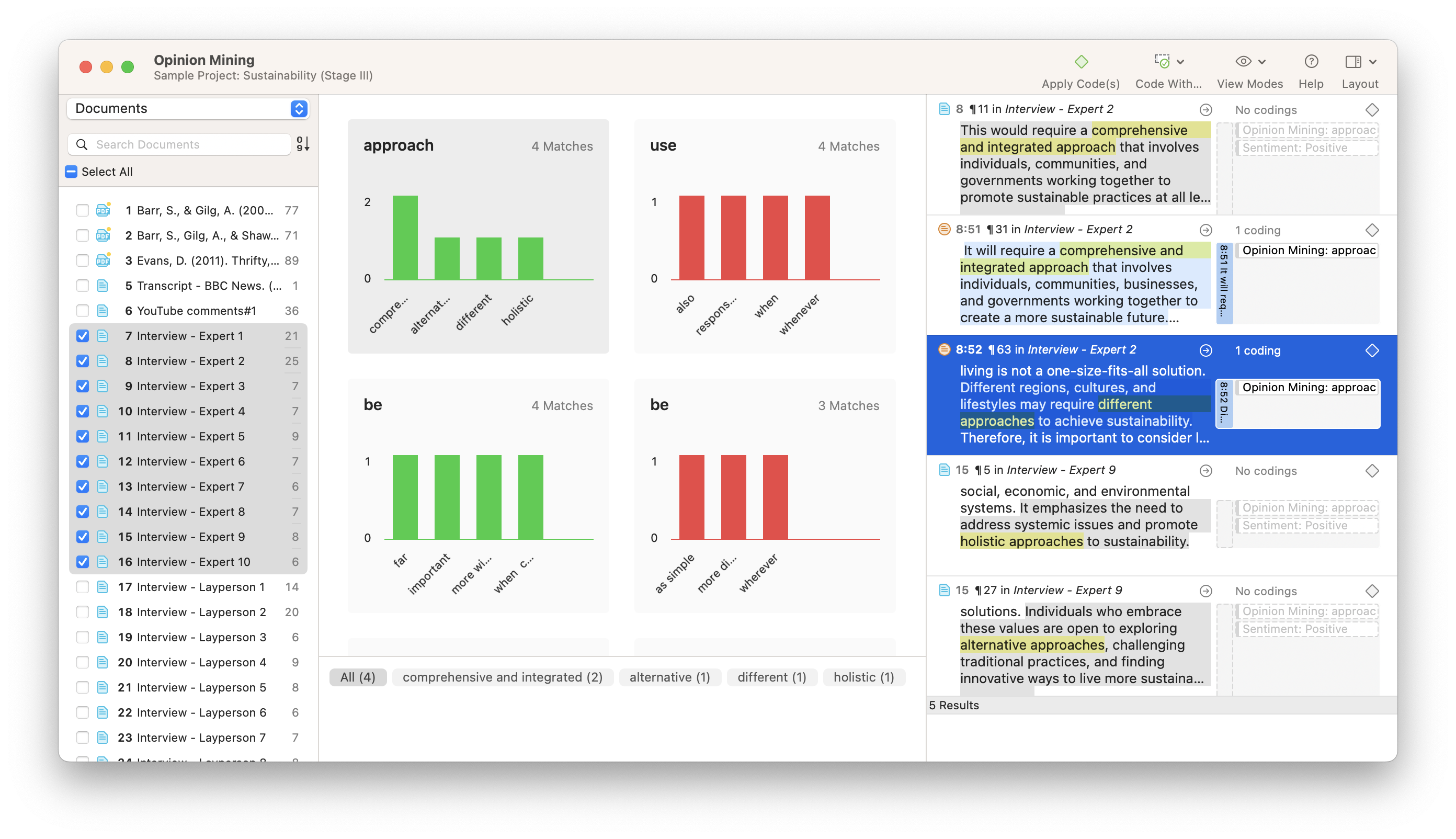

When it comes to qualitative data analysis, there are many different types of analyses (we discuss some of the most popular ones here ) and the type of analysis you adopt will depend heavily on your research aims, objectives and questions . Therefore, we’re not going to go down that rabbit hole here, but we’ll cover the important first steps that build the bridge from qualitative data coding to qualitative analysis.

When starting to think about your analysis, it’s useful to ask yourself the following questions to get the wheels turning:

- What actions are shown in the data?

- What are the aims of these interactions and excerpts? What are the participants potentially trying to achieve?

- How do participants interpret what is happening, and how do they speak about it? What does their language reveal?

- What are the assumptions made by the participants?

- What are the participants doing? What is going on?

- Why do I want to learn about this? What am I trying to find out?

- Why did I include this particular excerpt? What does it represent and how?

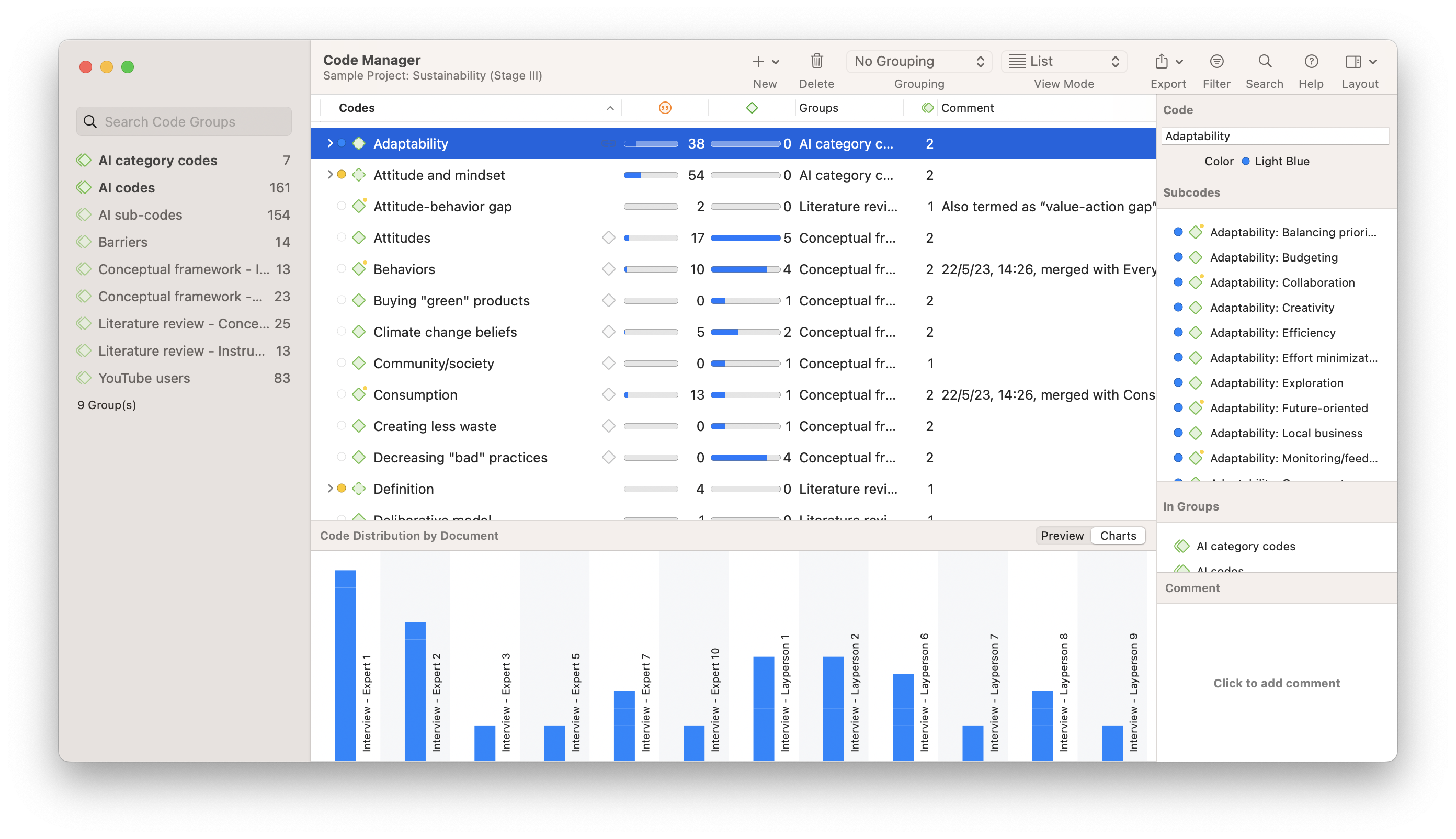

Code categorisation

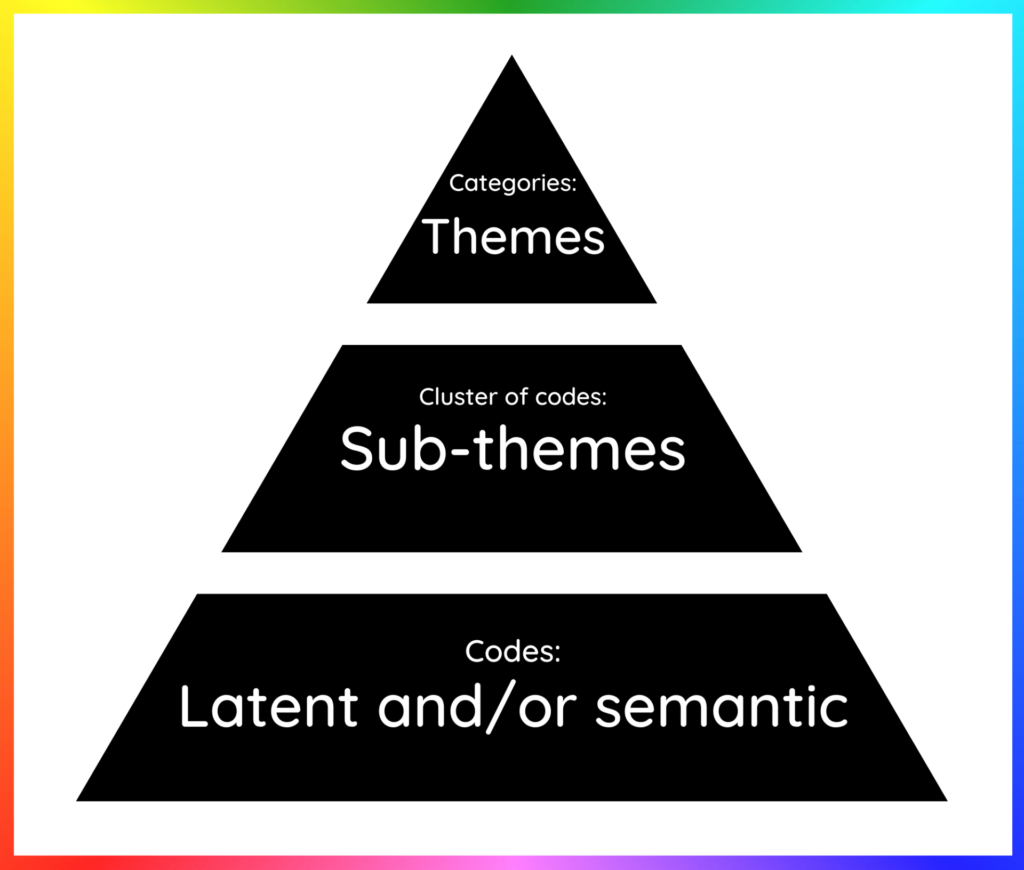

Categorisation is simply the process of reviewing everything you’ve coded and then creating code categories that can be used to guide your future analysis. In other words, it’s about creating categories for your code set. Let’s take a look at a practical example.

If you were discussing different types of animals, your initial codes may be “dogs”, “llamas”, and “lions”. In the process of categorisation, you could label (categorise) these three animals as “mammals”, whereas you could categorise “flies”, “crickets”, and “beetles” as “insects”. By creating these code categories, you will be making your data more organised, as well as enriching it so that you can see new connections between different groups of codes.

Theme identification

From the coding and categorisation processes, you’ll naturally start noticing themes. Therefore, the logical next step is to identify and clearly articulate the themes in your data set. When you determine themes, you’ll take what you’ve learned from the coding and categorisation and group it all together to develop themes. This is the part of the coding process where you’ll try to draw meaning from your data, and start to produce a narrative . The nature of this narrative depends on your research aims and objectives, as well as your research questions (sounds familiar?) and the qualitative data analysis method you’ve chosen, so keep these factors front of mind as you scan for themes.

Tips & tricks for quality coding

Before we wrap up, let’s quickly look at some general advice, tips and suggestions to ensure your qualitative data coding is top-notch.

- Before you begin coding, plan out the steps you will take and the coding approach and technique(s) you will follow to avoid inconsistencies.

- When adopting deductive coding, it’s useful to use a codebook from the start of the coding process. This will keep your work organised and will ensure that you don’t forget any of your codes.

- Whether you’re adopting an inductive or deductive approach, keep track of the meanings of your codes and remember to revisit these as you go along.

- Avoid using synonyms for codes that are similar, if not the same. This will allow you to have a more uniform and accurate coded dataset and will also help you to not get overwhelmed by your data.

- While coding, make sure that you remind yourself of your aims and coding method. This will help you to avoid directional drift , which happens when coding is not kept consistent.

- If you are working in a team, make sure that everyone has been trained and understands how codes need to be assigned.

32 Comments

I appreciated the valuable information provided to accomplish the various stages of the inductive and inductive coding process. However, I would have been extremely satisfied to be appraised of the SPECIFIC STEPS to follow for: 1. Deductive coding related to the phenomenon and its features to generate the codes, categories, and themes. 2. Inductive coding related to using (a) Initial (b) Axial, and (c) Thematic procedures using transcribe data from the research questions

Thank you so much for this. Very clear and simplified discussion about qualitative data coding.

This is what I want and the way I wanted it. Thank you very much.

All of the information’s are valuable and helpful. Thank for you giving helpful information’s. Can do some article about alternative methods for continue researches during the pandemics. It is more beneficial for those struggling to continue their researchers.

Thank you for your information on coding qualitative data, this is a very important point to be known, really thank you very much.

Very useful article. Clear, articulate and easy to understand. Thanks

This is very useful. You have simplified it the way I wanted it to be! Thanks

Thank you so very much for explaining, this is quite helpful!

hello, great article! well written and easy to understand. Can you provide some of the sources in this article used for further reading purposes?

You guys are doing a great job out there . I will not realize how many students you help through your articles and post on a daily basis. I have benefited a lot from your work. this is remarkable.

Wonderful one thank you so much.

Hello, I am doing qualitative research, please assist with example of coding format.

This is an invaluable website! Thank you so very much!

Well explained and easy to follow the presentation. A big thumbs up to you. Greatly appreciate the effort 👏👏👏👏

Thank you for this clear article with examples

Thank you for the detailed explanation. I appreciate your great effort. Congrats!

Ahhhhhhhhhh! You just killed me with your explanation. Crystal clear. Two Cheers!

D0 you have primary references that was used when creating this? If so, can you share them?

Being a complete novice to the field of qualitative data analysis, your indepth analysis of the process of thematic analysis has given me better insight. Thank you so much.

Excellent summary

Thank you so much for your precise and very helpful information about coding in qualitative data.

Thanks a lot to this helpful information. You cleared the fog in my brain.

Glad to hear that!

This has been very helpful. I am excited and grateful.

I still don’t understand the coding and categorizing of qualitative research, please give an example on my research base on the state of government education infrastructure environment in PNG

Wahho, this is amazing and very educational to have come across this site.. from a little search to a wide discovery of knowledge.

Thanks I really appreciate this.

Thank you so much! Very grateful.

This was truly helpful. I have been so lost, and this simplified the process for me.

Just at the right time when I needed to distinguish between inductive and

deductive data analysis of my Focus group discussion results very helpful

Very useful across disciplines and at all levels. Thanks…

Hello, Thank you for sharing your knowledge on us.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Chapter 18. Data Analysis and Coding

Introduction.

Piled before you lie hundreds of pages of fieldnotes you have taken, observations you’ve made while volunteering at city hall. You also have transcripts of interviews you have conducted with the mayor and city council members. What do you do with all this data? How can you use it to answer your original research question (e.g., “How do political polarization and party membership affect local politics?”)? Before you can make sense of your data, you will have to organize and simplify it in a way that allows you to access it more deeply and thoroughly. We call this process coding . [1] Coding is the iterative process of assigning meaning to the data you have collected in order to both simplify and identify patterns. This chapter introduces you to the process of qualitative data analysis and the basic concept of coding, while the following chapter (chapter 19) will take you further into the various kinds of codes and how to use them effectively.

To those who have not yet conducted a qualitative study, the sheer amount of collected data will be a surprise. Qualitative data can be absolutely overwhelming—it may mean hundreds if not thousands of pages of interview transcripts, or fieldnotes, or retrieved documents. How do you make sense of it? Students often want very clear guidelines here, and although I try to accommodate them as much as possible, in the end, analyzing qualitative data is a bit more of an art than a science: “The process of bringing order, structure, and interpretation to a mass of collected data is messy, ambiguous, time-consuming, creative, and fascinating. It does not proceed in a linear fashion: it is not neat. At times, the researcher may feel like an eccentric and tormented artist; not to worry, this is normal” ( Marshall and Rossman 2016:214 ).

To complicate matters further, each approach (e.g., Grounded Theory, deep ethnography, phenomenology) has its own language and bag of tricks (techniques) when it comes to analysis. Grounded Theory, for example, uses in vivo coding to generate new theoretical insights that emerge from a rigorous but open approach to data analysis. Ethnographers, in contrast, are more focused on creating a rich description of the practices, behaviors, and beliefs that operate in a particular field. They are less interested in generating theory and more interested in getting the picture right, valuing verisimilitude in the presentation. And then there are some researchers who seek to account for the qualitative data using almost quantitative methods of analysis, perhaps counting and comparing the uses of certain narrative frames in media accounts of a phenomenon. Qualitative content analysis (QCA) often includes elements of counting (see chapter 17). For these researchers, having very clear hypotheses and clearly defined “variables” before beginning analysis is standard practice, whereas the same would be expressly forbidden by those researchers, like grounded theorists, taking a more emergent approach.

All that said, there are some helpful techniques to get you started, and these will be presented in this and the following chapter. As you become more of an expert yourself, you may want to read more deeply about the tradition that speaks to your research. But know that there are many excellent qualitative researchers that use what works for any given study, who take what they can from each tradition. Most of us find this permissible (but watch out for the methodological purists that exist among us).

Qualitative Data Analysis as a Long Process!

Although most of this and the following chapter will focus on coding, it is important to understand that coding is just one (very important) aspect of the long data-analysis process. We can consider seven phases of data analysis, each of which is important for moving your voluminous data into “findings” that can be reported to others. The first phase involves data organization. This might mean creating a special password-protected Dropbox folder for storing your digital files. It might mean acquiring computer-assisted qualitative data-analysis software ( CAQDAS ) and uploading all transcripts, fieldnotes, and digital files to its storage repository for eventual coding and analysis. Finding a helpful way to store your material can take a lot of time, and you need to be smart about this from the very beginning. Losing data because of poor filing systems or mislabeling is something you want to avoid. You will also want to ensure that you have procedures in place to protect the confidentiality of your interviewees and informants. Filing signed consent forms (with names) separately from transcripts and linking them through an ID number or other code that only you have access to (and store safely) are important.

Once you have all of your material safely and conveniently stored, you will need to immerse yourself in the data. The second phase consists of reading and rereading or viewing and reviewing all of your data. As you do this, you can begin to identify themes or patterns in the data, perhaps writing short memos to yourself about what you are seeing. You are not committing to anything in this third phase but rather keeping your eyes and mind open to what you see. In an actual study, you may very well still be “in the field” or collecting interviews as you do this, and what you see might push you toward either concluding your data collection or expanding so that you can follow a particular group or factor that is emerging as important. For example, you may have interviewed twelve international college students about how they are adjusting to life in the US but realized as you read your transcripts that important gender differences may exist and you have only interviewed two women (and ten men). So you go back out and make sure you have enough female respondents to check your impression that gender matters here. The seven phases do not proceed entirely linearly! It is best to think of them as recursive; conceptually, there is a path to follow, but it meanders and flows.

Coding is the activity of the fourth phase . The second part of this chapter and all of chapter 19 will focus on coding in greater detail. For now, know that coding is the primary tool for analyzing qualitative data and that its purpose is to both simplify and highlight the important elements buried in mounds of data. Coding is a rigorous and systematic process of identifying meaning, patterns, and relationships. It is a more formal extension of what you, as a conscious human being, are trained to do every day when confronting new material and experiences. The “trick” or skill is to learn how to take what you do naturally and semiconsciously in your mind and put it down on paper so it can be documented and verified and tested and refined.

At the conclusion of the coding phase, your material will be searchable, intelligible, and ready for deeper analysis. You can begin to offer interpretations based on all the work you have done so far. This fifth phase might require you to write analytic memos, beginning with short (perhaps a paragraph or two) interpretations of various aspects of the data. You might then attempt stitching together both reflective and analytical memos into longer (up to five pages) general interpretations or theories about the relationships, activities, patterns you have noted as salient.

As you do this, you may be rereading the data, or parts of the data, and reviewing your codes. It’s possible you get to this phase and decide you need to go back to the beginning. Maybe your entire research question or focus has shifted based on what you are now thinking is important. Again, the process is recursive , not linear. The sixth phase requires you to check the interpretations you have generated. Are you really seeing this relationship, or are you ignoring something important you forgot to code? As we don’t have statistical tests to check the validity of our findings as quantitative researchers do, we need to incorporate self-checks on our interpretations. Ask yourself what evidence would exist to counter your interpretation and then actively look for that evidence. Later on, if someone asks you how you know you are correct in believing your interpretation, you will be able to explain what you did to verify this. Guard yourself against accusations of “ cherry-picking ,” selecting only the data that supports your preexisting notion or expectation about what you will find. [2]

The seventh and final phase involves writing up the results of the study. Qualitative results can be written in a variety of ways for various audiences (see chapter 20). Due to the particularities of qualitative research, findings do not exist independently of their being written down. This is different for quantitative research or experimental research, where completed analyses can somewhat speak for themselves. A box of collected qualitative data remains a box of collected qualitative data without its written interpretation. Qualitative research is often evaluated on the strength of its presentation. Some traditions of qualitative inquiry, such as deep ethnography, depend on written thick descriptions, without which the research is wholly incomplete, even nonexistent. All of that practice journaling and writing memos (reflective and analytical) help develop writing skills integral to the presentation of the findings.

Remember that these are seven conceptual phases that operate in roughly this order but with a lot of meandering and recursivity throughout the process. This is very different from quantitative data analysis, which is conducted fairly linearly and processually (first you state a falsifiable research question with hypotheses, then you collect your data or acquire your data set, then you analyze the data, etc.). Things are a bit messier when conducting qualitative research. Embrace the chaos and confusion, and sort your way through the maze. Budget a lot of time for this process. Your research question might change in the middle of data collection. Don’t worry about that. The key to being nimble and flexible in qualitative research is to start thinking and continue thinking about your data, even as it is being collected. All seven phases can be started before all the data has been gathered. Data collection does not always precede data analysis. In some ways, “qualitative data collection is qualitative data analysis.… By integrating data collection and data analysis, instead of breaking them up into two distinct steps, we both enrich our insights and stave off anxiety. We all know the anxiety that builds when we put something off—the longer we put it off, the more anxious we get. If we treat data collection as this mass of work we must do before we can get started on the even bigger mass of work that is analysis, we set ourselves up for massive anxiety” ( Rubin 2021:182–183 ; emphasis added).

The Coding Stage

A code is “a word or short phrase that symbolically assigns a summative, salient, essence-capturing, and/or evocative attribute for a portion of language-based or visual data” ( Saldaña 2014:5 ). Codes can be applied to particular sections of or entire transcripts, documents, or even videos. For example, one might code a video taken of a preschooler trying to solve a puzzle as “puzzle,” or one could take the transcript of that video and highlight particular sections or portions as “arranging puzzle pieces” (a descriptive code) or “frustration” (a summative emotion-based code). If the preschooler happily shouts out, “I see it!” you can denote the code “I see it!” (this is an example of an in vivo, participant-created code). As one can see from even this short example, there are many different kinds of codes and many different strategies and techniques for coding, more of which will be discussed in detail in chapter 19. The point to remember is that coding is a rigorous systematic process—to some extent, you are always coding whenever you look at a person or try to make sense of a situation or event, but you rarely do this consciously. Coding is the process of naming what you are seeing and how you are simplifying the data so that you can make sense of it in a way that is consistent with your study and in a way that others can understand and follow and replicate. Another way of saying this is that a code is “a researcher-generated interpretation that symbolizes or translates data” ( Vogt et al. 2014:13 ).

As with qualitative data analysis generally, coding is often done recursively, meaning that you do not merely take one pass through the data to create your codes. Saldaña ( 2014 ) differentiates first-cycle coding from second-cycle coding. The goal of first-cycle coding is to “tag” or identify what emerges as important codes. Note that I said emerges—you don’t always know from the beginning what will be an important aspect of the study or not, so the coding process is really the place for you to begin making the kinds of notes necessary for future analyses. In second-cycle coding, you will want to be much more focused—no longer gathering wholly new codes but synthesizing what you have into metacodes.

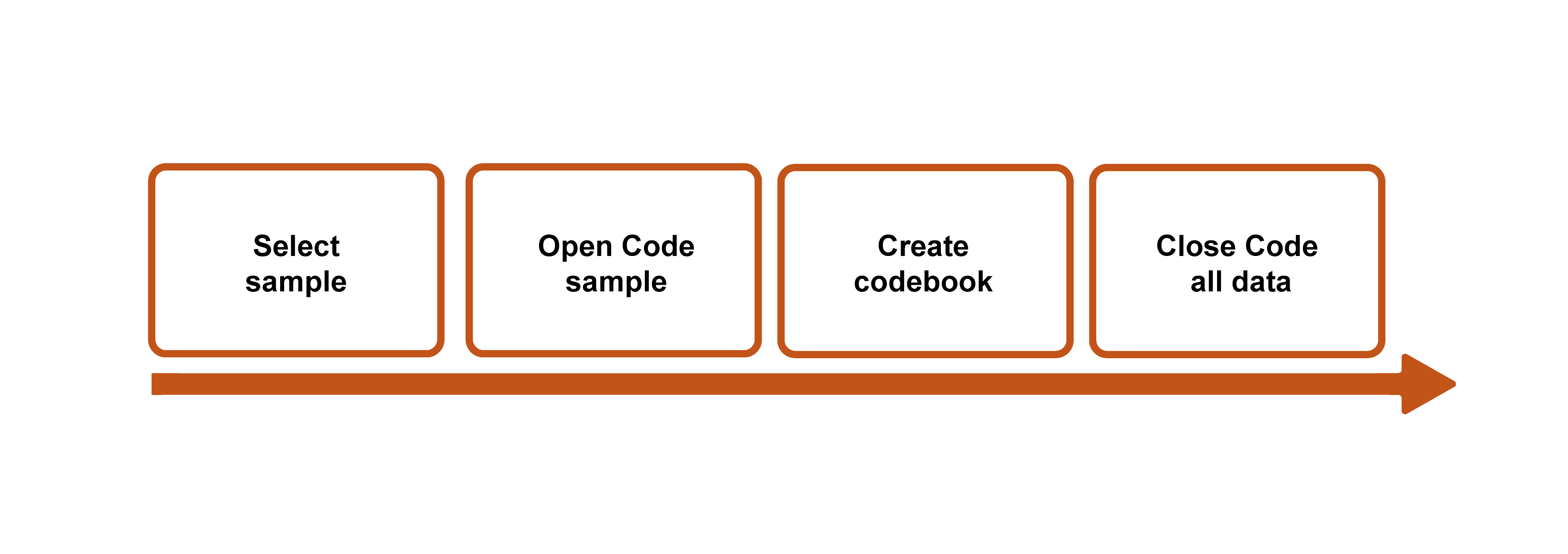

You might also conceive of the coding process in four parts (figure 18.1). First, identify a representative or diverse sample set of interview transcripts (or fieldnotes or other documents). This is the group you are going to use to get a sense of what might be emerging. In my own study of career obstacles to success among first-generation and working-class persons in sociology, I might select one interview from each career stage: a graduate student, a junior faculty member, a senior faculty member.

Second, code everything (“ open coding ”). See what emerges, and don’t limit yourself in any way. You will end up with a ton of codes, many more than you will end up with, but this is an excellent way to not foreclose an interesting finding too early in the analysis. Note the importance of starting with a sample of your collected data, because otherwise, open coding all your data is, frankly, impossible and counterproductive. You will just get stuck in the weeds.

Third, pare down your coding list. Where you may have begun with fifty (or more!) codes, you probably want no more than twenty remaining. Go back through the weeds and pull out everything that does not have the potential to bloom into a nicely shaped garden. Note that you should do this before tackling all of your data . Sometimes, however, you might need to rethink the sample you chose. Let’s say that the graduate student interview brought up some interesting gender issues that were pertinent to female-identifying sociologists, but both the junior and the senior faculty members identified as male. In that case, I might read through and open code at least one other interview transcript, perhaps a female-identifying senior faculty member, before paring down my list of codes.

This is also the time to create a codebook if you are using one, a master guide to the codes you are using, including examples (see Sample Codebooks 1 and 2 ). A codebook is simply a document that lists and describes the codes you are using. It is easy to forget what you meant the first time you penciled a coded notation next to a passage, so the codebook allows you to be clear and consistent with the use of your codes. There is not one correct way to create a codebook, but generally speaking, the codebook should include (1) the code (either name or identification number or both), (2) a description of what the code signifies and when and where it should be applied, and (3) an example of the code to help clarify (2). Listing all the codes down somewhere also allows you to organize and reorganize them, which can be part of the analytical process. It is possible that your twenty remaining codes can be neatly organized into five to seven master “themes.” Codebooks can and should develop as you recursively read through and code your collected material. [3]

Fourth, using the pared-down list of codes (or codebook), read through and code all the data. I know many qualitative researchers who work without a codebook, but it is still a good practice, especially for beginners. At the very least, read through your list of codes before you begin this “ closed coding ” step so that you can minimize the chance of missing a passage or section that needs to be coded. The final step is…to do it all again. Or, at least, do closed coding (step four) again. All of this takes a great deal of time, and you should plan accordingly.

Researcher Note

People often say that qualitative research takes a lot of time. Some say this because qualitative researchers often collect their own data. This part can be time consuming, but to me, it’s the analytical process that takes the most time. I usually read every transcript twice before starting to code, then it usually takes me six rounds of coding until I’m satisfied I’ve thoroughly coded everything. Even after the coding, it usually takes me a year to figure out how to put the analysis together into a coherent argument and to figure out what language to use. Just deciding what name to use for a particular group or idea can take months. Understanding this going in can be helpful so that you know to be patient with yourself.

—Jessi Streib, author of The Power of the Past and Privilege Lost

Note that there is no magic in any of this, nor is there any single “right” way to code or any “correct” codes. What you see in the data will be prompted by your position as a researcher and your scholarly interests. Where the above codes on a preschooler solving a puzzle emerged from my own interest in puzzle solving, another researcher might focus on something wholly different. A scholar of linguistics, for example, may focus instead on the verbalizations made by the child during the discovery process, perhaps even noting particular vocalizations (incidence of grrrs and gritting of the teeth, for example). Your recording of the codes you used is the important part, as it allows other researchers to assess the reliability and validity of your analyses based on those codes. Chapter 19 will provide more details about the kinds of codes you might develop.

Saldaña ( 2014 ) lists seven “necessary personal attributes” for successful coding. To paraphrase, they are the following:

- Having (or practicing) good organizational skills

- Perseverance

- The ability and willingness to deal with ambiguity

- Flexibility

- Creativity, broadly understood, which includes “the ability to think visually, to think symbolically, to think in metaphors, and to think of as many ways as possible to approach a problem” (20)

- Commitment to being rigorously ethical

- Having an extensive vocabulary [4]

Writing Analytic Memos during/after Coding

Coding the data you have collected is only one aspect of analyzing it. Too many beginners have coded their data and then wondered what to do next. Coding is meant to help organize your data so that you can see it more clearly, but it is not itself an analysis. Thinking about the data, reviewing the coded data, and bringing in the previous literature (here is where you use your literature review and theory) to help make sense of what you have collected are all important aspects of data analysis. Analytic memos are notes you write to yourself about the data. They can be short (a single page or even a paragraph) or long (several pages). These memos can themselves be the subject of subsequent analytic memoing as part of the recursive process that is qualitative data analysis.

Short analytic memos are written about impressions you have about the data, what is emerging, and what might be of interest later on. You can write a short memo about a particular code, for example, and why this code seems important and where it might connect to previous literature. For example, I might write a paragraph about a “cultural capital” code that I use whenever a working-class sociologist says anything about “not fitting in” with their peers (e.g., not having the right accent or hairstyle or private school background). I could then write a little bit about Bourdieu, who originated the notion of cultural capital, and try to make some connections between his definition and how I am applying it here. I can also use the memo to raise questions or doubts I have about what I am seeing (e.g., Maybe the type of school belongs somewhere else? Is this really the right code?). Later on, I can incorporate some of this writing into the theory section of my final paper or article. Here are some types of things that might form the basis of a short memo: something you want to remember, something you noticed that was new or different, a reaction you had, a suspicion or hunch that you are developing, a pattern you are noticing, any inferences you are starting to draw. Rubin ( 2021 ) advises, “Always include some quotation or excerpt from your dataset…that set you off on this idea. It’s happened to me so many times—I’ll have a really strong reaction to a piece of data, write down some insight without the original quotation or context, and then [later] have no idea what I was talking about and have no way of recreating my insight because I can’t remember what piece of data made me think this way” ( 203 ).

All CAQDAS programs include spaces for writing, generating, and storing memos. You can link a memo to a particular transcript, for example. But you can just as easily keep a notebook at hand in which you write notes to yourself, if you prefer the more tactile approach. Drawing pictures that illustrate themes and patterns you are beginning to see also works. The point is to write early and write often, as these memos are the building blocks of your eventual final product (chapter 20).

In the next chapter (chapter 19), we will go a little deeper into codes and how to use them to identify patterns and themes in your data. This chapter has given you an idea of the process of data analysis, but there is much yet to learn about the elements of that process!

Qualitative Data-Analysis Samples

The following three passages are examples of how qualitative researchers describe their data-analysis practices. The first, by Harvey, is a useful example of how data analysis can shift the original research questions. The second example, by Thai, shows multiple stages of coding and how these stages build upward to conceptual themes and theorization. The third example, by Lamont, shows a masterful use of a variety of techniques to generate theory.

Example 1: “Look Someone in the Eye” by Peter Francis Harvey ( 2022 )

I entered the field intending to study gender socialization. However, through the iterative process of writing fieldnotes, rereading them, conducting further research, and writing extensive analytic memos, my focus shifted. Abductive analysis encourages the search for unexpected findings in light of existing literature. In my early data collection, fieldnotes, and memoing, classed comportment was unmistakably prominent in both schools. I was surprised by how pervasive this bodily socialization proved to be and further surprised by the discrepancies between the two schools.…I returned to the literature to compare my empirical findings.…To further clarify patterns within my data and to aid the search for disconfirming evidence, I constructed data matrices (Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña 2013). While rereading my fieldnotes, I used ATLAS.ti to code and recode key sections (Miles et al. 2013), punctuating this process with additional analytic memos. ( 2022:1420 )

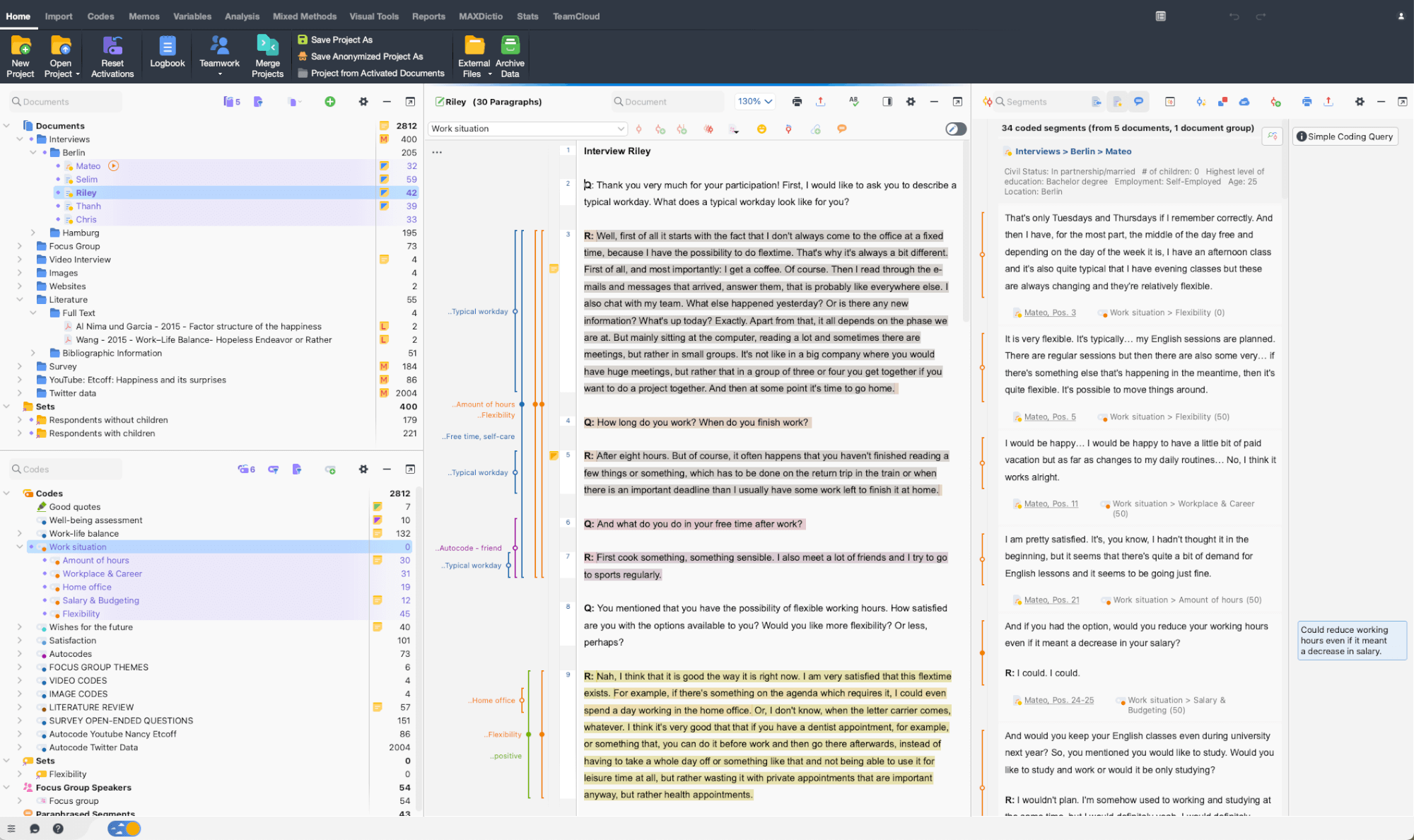

Example 2:” Policing and Symbolic Control” by Mai Thai ( 2022 )

Conventional to qualitative research, my analyses iterated between theory development and testing. Analytical memos were written throughout the data collection, and my analyses using MAXQDA software helped me develop, confirm, and challenge specific themes.…My early coding scheme which included descriptive codes (e.g., uniform inspection, college trips) and verbatim codes of the common terms used by field site participants (e.g., “never quit,” “ghetto”) led me to conceptualize valorization. Later analyses developed into thematic codes (e.g., good citizens, criminality) and process codes (e.g., valorization, criminalization), which helped refine my arguments. ( 2022:1191–1192 )

Example 3: The Dignity of Working Men by Michèle Lamont ( 2000 )

To analyze the interviews, I summarized them in a 13-page document including socio-demographic information as well as information on the boundary work of the interviewees. To facilitate comparisons, I noted some of the respondents’ answers on grids and summarized these on matrix displays using techniques suggested by Miles and Huberman for standardizing and processing qualitative data. Interviews were also analyzed one by one, with a focus on the criteria that each respondent mobilized for the evaluation of status. Moreover, I located each interviewee on several five-point scales pertaining to the most significant dimensions they used to evaluate status. I also compared individual interviewees with respondents who were similar to and different from them, both within and across samples. Finally, I classified all the transcripts thematically to perform a systematic analysis of all the important themes that appear in the interviews, approaching the latter as data against which theoretical questions can be explored. ( 2000:256–257 )

Sample Codebook 1

This is an abridged version of the codebook used to analyze qualitative responses to a question about how class affects careers in sociology. Note the use of numbers to organize the flow, supplemented by highlighting techniques (e.g., bolding) and subcoding numbers.

01. CAPS: Any reference to “capitals” in the response, even if the specific words are not used

01.1: cultural capital 01.2: social capital 01.3: economic capital

(can be mixed: “0.12”= both cultural and asocial capital; “0.23”= both social and economic)

01. CAPS: a reference to “capitals” in which the specific words are used [ bold : thus, 01.23 means that both social capital and economic capital were mentioned specifically

02. DEBT: discussion of debt

02.1: mentions personal issues around debt 02.2: discusses debt but in the abstract only (e.g., “people with debt have to worry”)

03. FirstP: how the response is positioned

03.1: neutral or abstract response 03.2: discusses self (“I”) 03.3: discusses others (“they”)

Sample Coded Passage:

| “I was really hurt when I didn’t get that scholarship. It was going to cost me thousands of dollars to stay in the program, and I was going to have to borrow all of it. My faculty advisor wasn’t helpful at all. They told | 03.2 |

| me not to worry about it, because it wasn’t really that much money! I almost fell over when they said that! Like, do they not understand what it’s like to be poor? I just felt so isolated then. I was on my own. | 02.1. 01.3 |

| I couldn’t talk to anyone about it, because no one else seemed to worry about it. Talk about economic capital!” |

* Question: What other codes jump out to you here? Shouldn’t there be a code for feelings of loneliness or alienation? What about an emotions code ?

Sample Codebook 2

| CODE | DEFINITION | WHEN TO APPLY | IN VIVO EXAMPLE |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALIENATION | Feeling out of place in academia | Any time uses the word alienation or impostor syndrome or feeling out of place | “I was so lonely in graduate school. It was an alienating experience.” |

| CULTURAL CAPITAL | Knowledge or other cultural resources that affect success in academia | When “cultural capital” is used but also when knowledge or lack of knowledge about cultural things are discussed | “We went to a fancy restaurant after my job interview and I was paralyzed with fear because I did not know which fork I was supposed to be using. Yikes!” |

| SOCIAL CAPITAL | Social networks that advance success in academia | When “social capital” is used but also when social networks are discussed or knowing the right people | “I didn’t know who to turn to. It seemed like everyone else had parents who could help them and I didn’t know anyone else who had ever even gone to college!” |

This is an example that uses "word" categories only, with descriptions and examples for each code

Further Readings

Elliott, Victoria. 2018. “Thinking about the Coding Process in Qualitative Analysis.” Qualitative Report 23(11):2850–2861. Address common questions those new to coding ask, including the use of “counting” and how to shore up reliability.

Friese, Susanne. 2019. Qualitative Data Analysis with ATLAS.ti. 3rd ed. A good guide to ATLAS.ti, arguably the most used CAQDAS program. Organized around a series of “skills training” to get you up to speed.

Jackson, Kristi, and Pat Bazeley. 2019. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVIVO . 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. If you want to use the CAQDAS program NVivo, this is a good affordable guide to doing so. Includes copious examples, figures, and graphic displays.

LeCompte, Margaret D. 2000. “Analyzing Qualitative Data.” Theory into Practice 39(3):146–154. A very practical and readable guide to the entire coding process, with particular applicability to educational program evaluation/policy analysis.

Miles, Matthew B., and A. Michael Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. A classic reference on coding. May now be superseded by Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña (2019).

Miles, Matthew B., A. Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldaña. 2019. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook . 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA; SAGE. A practical methods sourcebook for all qualitative researchers at all levels using visual displays and examples. Highly recommended.

Saldaña, Johnny. 2014. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. The most complete and comprehensive compendium of coding techniques out there. Essential reference.

Silver, Christina. 2014. Using Software in Qualitative Research: A Step-by-Step Guide. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA; SAGE. If you are unsure which CAQDAS program you are interested in using or want to compare the features and usages of each, this guidebook is quite helpful.

Vogt, W. Paul, Elaine R. Vogt, Diane C. Gardner, and Lynne M. Haeffele2014. Selecting the Right Analyses for Your Data: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods . New York: The Guilford Press. User-friendly reference guide to all forms of analysis; may be particularly helpful for those engaged in mixed-methods research.

- When you have collected content (historical, media, archival) that interests you because of its communicative aspect, content analysis (chapter 17) is appropriate. Whereas content analysis is both a research method and a tool of analysis, coding is a tool of analysis that can be used for all kinds of data to address any number of questions. Content analysis itself includes coding. ↵

- Scientific research, whether quantitative or qualitative, demands we keep an open mind as we conduct our research, that we are “neutral” regarding what is actually there to find. Students who are trained in non-research-based disciplines such as the arts or philosophy or who are (admirably) focused on pursuing social justice can too easily fall into the trap of thinking their job is to “demonstrate” something through the data. That is not the job of a researcher. The job of a researcher is to present (and interpret) findings—things “out there” (even if inside other people’s hearts and minds). One helpful suggestion: when formulating your research question, if you already know the answer (or think you do), scrap that research. Ask a question to which you do not yet know the answer. ↵

- Codebooks are particularly useful for collaborative research so that codes are applied and interpreted similarly. If you are working with a team of researchers, you will want to take extra care that your codebooks remain in synch and that any refinements or developments are shared with fellow coders. You will also want to conduct an “intercoder reliability” check, testing whether the codes you have developed are clearly identifiable so that multiple coders are using them similarly. Messy, unclear codes that can be interpreted differently by different coders will make it much more difficult to identify patterns across the data. ↵

- Note that this is important for creating/denoting new codes. The vocabulary does not need to be in English or any particular language. You can use whatever words or phrases capture what it is you are seeing in the data. ↵

A first-cycle coding process in which gerunds are used to identify conceptual actions, often for the purpose of tracing change and development over time. Widely used in the Grounded Theory approach.

A first-cycle coding process in which terms or phrases used by the participants become the code applied to a particular passage. It is also known as “verbatim coding,” “indigenous coding,” “natural coding,” “emic coding,” and “inductive coding,” depending on the tradition of inquiry of the researcher. It is common in Grounded Theory approaches and has even given its name to one of the primary CAQDAS programs (“NVivo”).

Computer-assisted qualitative data-analysis software. These are software packages that can serve as a repository for qualitative data and that enable coding, memoing, and other tools of data analysis. See chapter 17 for particular recommendations.

The purposeful selection of some data to prove a preexisting expectation or desired point of the researcher where other data exists that would contradict the interpretation offered. Note that it is not cherry picking to select a quote that typifies the main finding of a study, although it would be cherry picking to select a quote that is atypical of a body of interviews and then present it as if it is typical.

A preliminary stage of coding in which the researcher notes particular aspects of interest in the data set and begins creating codes. Later stages of coding refine these preliminary codes. Note: in Grounded Theory , open coding has a more specific meaning and is often called initial coding : data are broken down into substantive codes in a line-by-line manner, and incidents are compared with one another for similarities and differences until the core category is found. See also closed coding .

A set of codes, definitions, and examples used as a guide to help analyze interview data. Codebooks are particularly helpful and necessary when research analysis is shared among members of a research team, as codebooks allow for standardization of shared meanings and code attributions.

The final stages of coding after the refinement of codes has created a complete list or codebook in which all the data is coded using this refined list or codebook. Compare to open coding .

A first-cycle coding process in which emotions and emotionally salient passages are tagged.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- AI & NLP

- Churn & Loyalty

- Customer Experience

- Customer Journeys

- Customer Metrics

- Feedback Analysis

- Product Experience

- Product Updates

- Sentiment Analysis

- Surveys & Feedback Collection

- Text Analytics

- Try Thematic

Welcome to the community

Coding Qualitative Data: How To Guide

How many hours have you spent sitting in front of Excel spreadsheets trying to find new insights from customer feedback?

You know that asking open-ended survey questions gives you more actionable insights than asking your customers for just a numerical Net Promoter Score (NPS) . But when you ask open-ended, free-text questions, you end up with hundreds (or even thousands) of free-text responses.

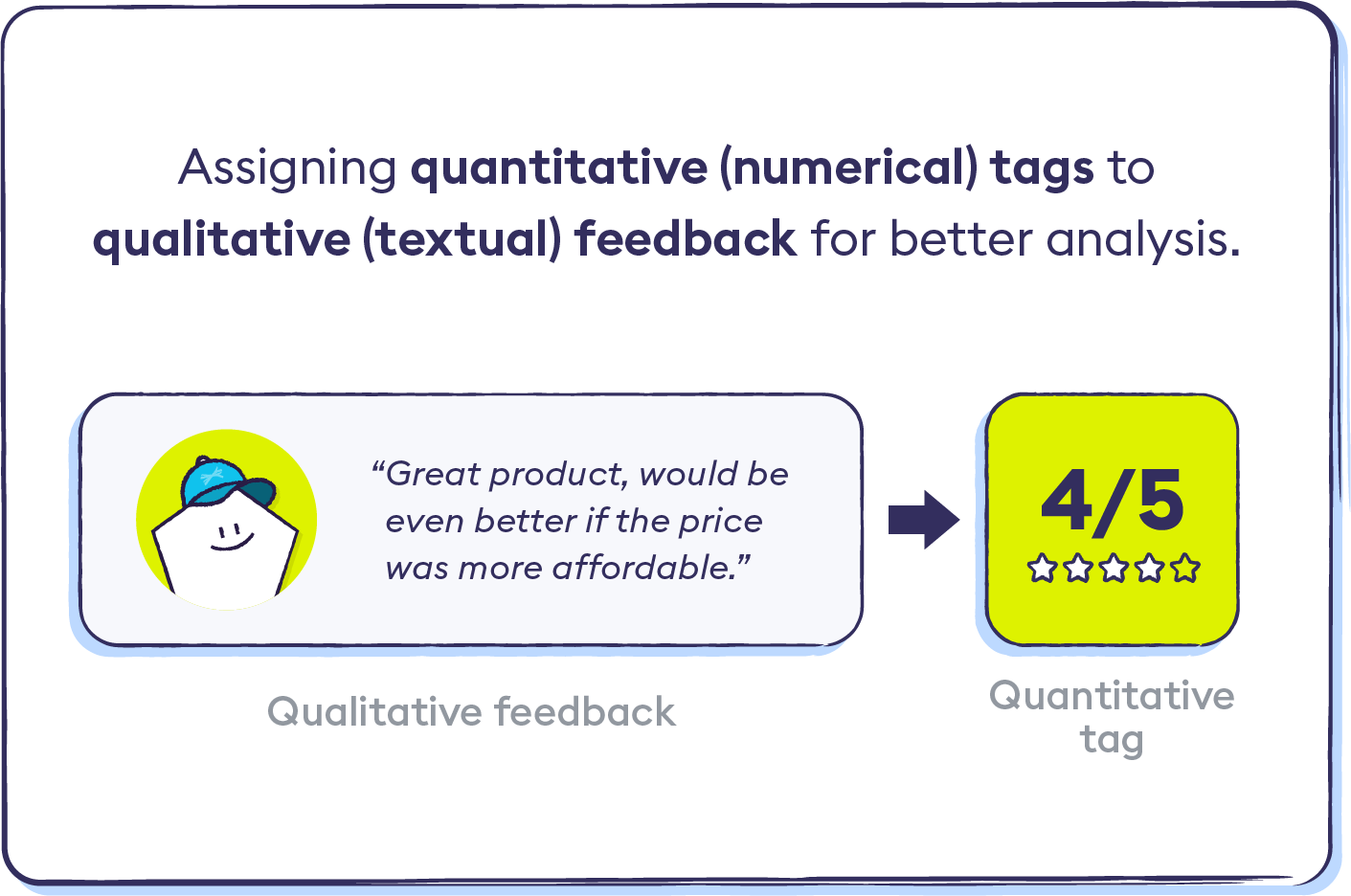

How can you turn all of that text into quantifiable, applicable information about your customers’ needs and expectations? By coding qualitative data.

In this article, we will cover different coding methods for qualitative data, including both manual and automated approaches, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the techniques used in the first-round pass at coding.

Keep reading to learn:

- What coding qualitative data means (and why it’s important)

- Different methods of coding qualitative data

- How to manually code qualitative data to find significant themes in your data

What is coding in qualitative research?

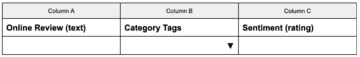

Conducting qualitative research, particularly through coding, is a crucial step in ensuring the validity and reliability of the findings. Coding is the process of labeling and organizing your qualitative data to identify different themes and the relationships between them.

When coding customer feedback , you assign labels to words or phrases that represent important (and recurring) themes in each response. These labels can be words, phrases, or numbers; we recommend using words or short phrases, since they’re easier to remember, skim, and organize.

Coding qualitative research to find common themes and concepts is part of thematic analysis . Thematic analysis extracts themes from text by analyzing the word and sentence structure.

Within the context of customer feedback, it’s important to understand the many different types of qualitative feedback a business can collect, such as open-ended surveys, social media comments, reviews & more.

What is qualitative data analysis?

Qualitative data analysis , including coding and analyzing qualitative data, is essential for understanding the depth and complexity of qualitative data. It is the process of examining and interpreting qualitative data to understand what it represents.

Qualitative analysis is crucial as it involves various methods such as thematic analysis, emotion coding, inductive and deductive thematic analysis, and content analysis. These methods help in coding the data, which is vital for the validity of the analysis.

Qualitative data is defined as any non-numerical and unstructured data; when looking at customer feedback, qualitative data usually refers to any verbatim or text-based feedback such as reviews, open-ended responses in surveys , complaints, chat messages, customer interviews, case notes or social media posts.

For example, NPS metric can be strictly quantitative, but when you ask customers why they gave you a rating a score, you will need qualitative data analysis methods in place to understand the comments that customers leave alongside numerical responses.

Methods of qualitative data analysis

Thematic analysis.

This refers to the uncovering of themes, by analyzing the patterns and relationships in a set of qualitative data. A theme emerges or is built when related findings appear to be meaningful and there are multiple occurrences. Thematic analysis can be used by anyone to transform and organize open-ended responses, analyze online reviews , and other qualitative data into significant themes. Thematic analysis coding is a method that aids in categorizing data extracts and deriving themes and patterns for qualitative analysis, facilitating the identification of themes revolving around a particular concept or phenomenon in the social sciences.

Content analysis:

This refers to the categorization, tagging and thematic analysis of qualitative data. Essentially content analysis is a quantification of themes, by counting the occurrence of concepts, topics or themes. Content analysis can involve combining the categories in qualitative data with quantitative data, such as behavioral data or demographic data, for deeper insights.

Narrative analysis:

Some qualitative data, such as interviews or field notes may contain a story on how someone experienced something. For example, the process of choosing a product, using it, evaluating its quality and decision to buy or not buy this product next time. The goal of narrative analysis is to turn the individual narratives into data that can be coded. This is then analyzed to understand how events or experiences had an impact on the people involved. Process coding is particularly useful in narrative analysis for identifying specific phases, sequences, and movements within the stories, capturing actions within qualitative data by using codes that typically represent gerunds ending in 'ing', providing a dynamic account of events within the data.

Discourse analysis:

This refers to analysis of what people say in social and cultural context. The goal of discourse analysis is to understand user or customer behavior by uncovering their beliefs, interests and agendas. These are reflected in the way they express their opinions, preferences and experiences. Structural coding is a method that can be applied here, organizing data based on predetermined structures, such as the structure of discourse elements, to enhance the analysis of discourse. It’s particularly useful when your focus is on building or strengthening a brand , by examining how they use metaphors and rhetorical devices.

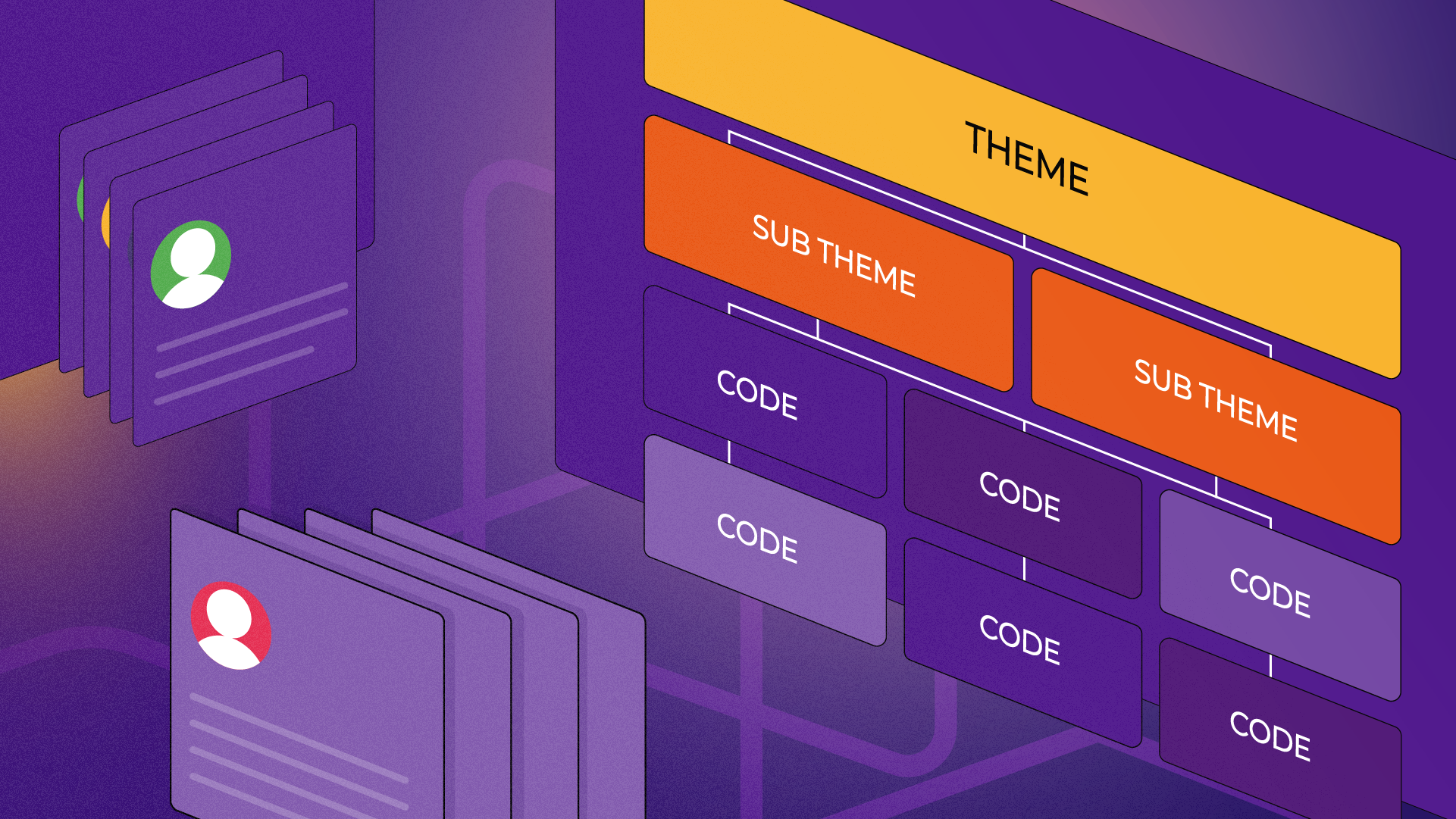

Framework analysis:

When performing qualitative data analysis, it is useful to have a framework to organize the buckets of meaning. A taxonomy or code frame (a hierarchical set of themes used in coding qualitative data) is an example of the result. Don't fall into the trap of starting with a framework to make it faster to organize your data. You should look at how themes relate to each other by analyzing the data and consistently check that you can validate that themes are related to each other .

Grounded theory:

This method of analysis starts by formulating a theory around a single data case. Therefore the theory is “grounded' in actual data. Then additional cases can be examined to see if they are relevant and can add to the original theory.

Why is it important to code qualitative data?

Coding qualitative data makes it easier to interpret customer feedback. Assigning codes to words and phrases in each response helps capture what the response is about which, in turn, helps you better analyze and summarize the results of the entire survey.

Researchers use coding and other qualitative data analysis processes to help them make data-driven decisions based on customer feedback. When you use coding to analyze your customer feedback, you can quantify the common themes in customer language. This makes it easier to accurately interpret and analyze customer satisfaction.

What is thematic coding?

Thematic coding, also called thematic analysis, is a type of qualitative data analysis that finds themes in text by analyzing the meaning of words and sentence structure.

When you use thematic coding to analyze customer feedback for example, you can learn which themes are most frequent in feedback. This helps you understand what drives customer satisfaction in an accurate, actionable way.

To learn more about how Thematic analysis software helps you automate the data coding process, check out this article .

Automated vs. Manual coding of qualitative data

Methods of coding qualitative data fall into three categories: automated coding and manual coding, and a blend of the two.

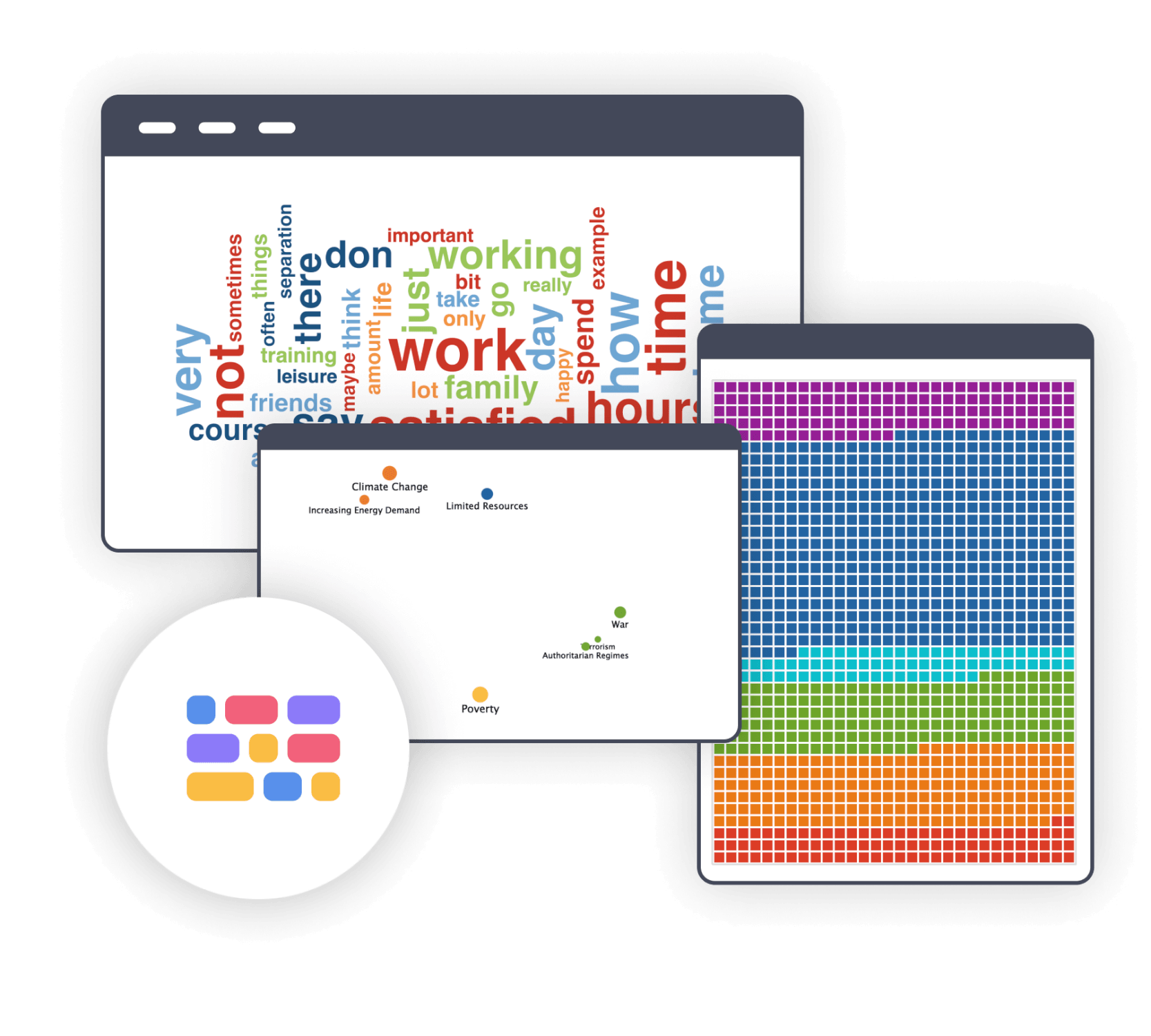

You can automate the coding of your qualitative data with thematic analysis software . Thematic analysis and qualitative data analysis software use machine learning, artificial intelligence (AI) natural language processing (NLP) to code your qualitative data and break text up into themes.

Thematic analysis software is autonomous , which means…

- You don't need to set up themes or categories in advance.

- You don't need to train the algorithm — it learns on its own.

- You can easily capture the “unknown unknowns” to identify themes you may not have spotted on your own.

…all of which will save you time (and lots of unnecessary headaches) when analyzing your customer feedback.

Businesses are also seeing the benefit of using thematic analysis software. The capacity to aggregate data sources into a single source of analysis helps to break down data silos, unifying the analysis and insights across departments . This is now being referred to as Omni channel analysis or Unified Data Analytics .

Use Thematic Analysis Software

Try Thematic today to discover why leading companies rely on the platform to automate the coding of qualitative customer feedback at scale. Whether you have tons of customer reviews, support chat, customer service conversationals ( conversational analytics ) or open-ended survey responses, Thematic brings every valuable insight to the surface, while saving you thousands of hours.

Advances in natural language processing & machine learning have made it possible to automate the analysis of qualitative data, in particular content and framework analysis. The most commonly used software for automated coding of qualitative data is text analytics software such as Thematic .

While manual human analysis is still popular due to its perceived high accuracy, automating most of the analysis is quickly becoming the preferred choice. Unlike manual analysis, which is prone to bias and doesn't scale to the amount of qualitative data that is generated today, automating analysis is not only more consistent and therefore can be more accurate, but can also save a ton of time, and therefore money.

Our Theme Editor tool ensures you take a reflexive approach, an important step in thematic analysis. The drag-and-drop tool makes it easy to refine, validate, and rename themes as you get more data. By guiding the AI, you can ensure your results are always precise, easy to understand and perfectly aligned with your objectives.

Thematic is the best software to automate code qualitative feedback at scale.

Don't just take it from us. Here's what some of our customers have to say:

I'm a fan of Thematic's ability to save time and create heroes. It does an excellent job using a single view to break down the verbatims into themes displayed by volume, sentiment and impact on our beacon metric, often but not exclusively NPS.

It does a superlative job using GenAI in summarizing a theme or sub-theme down to a single paragraph making it clear what folks are trying to say. Peter K, Snr Research Manager.

Thematic is a very intuitive tool to use. It boasts a robust level of granularity, allowing the user to see the general breadth of verbatim themes, dig into the sub-themes, and further into the sentiment of the open text itself. Artem C, Sr Manager of Research. LinkedIn.

AI-powered software to transform qualitative data at scale through a thematic and content analysis.

How to manually code qualitative data

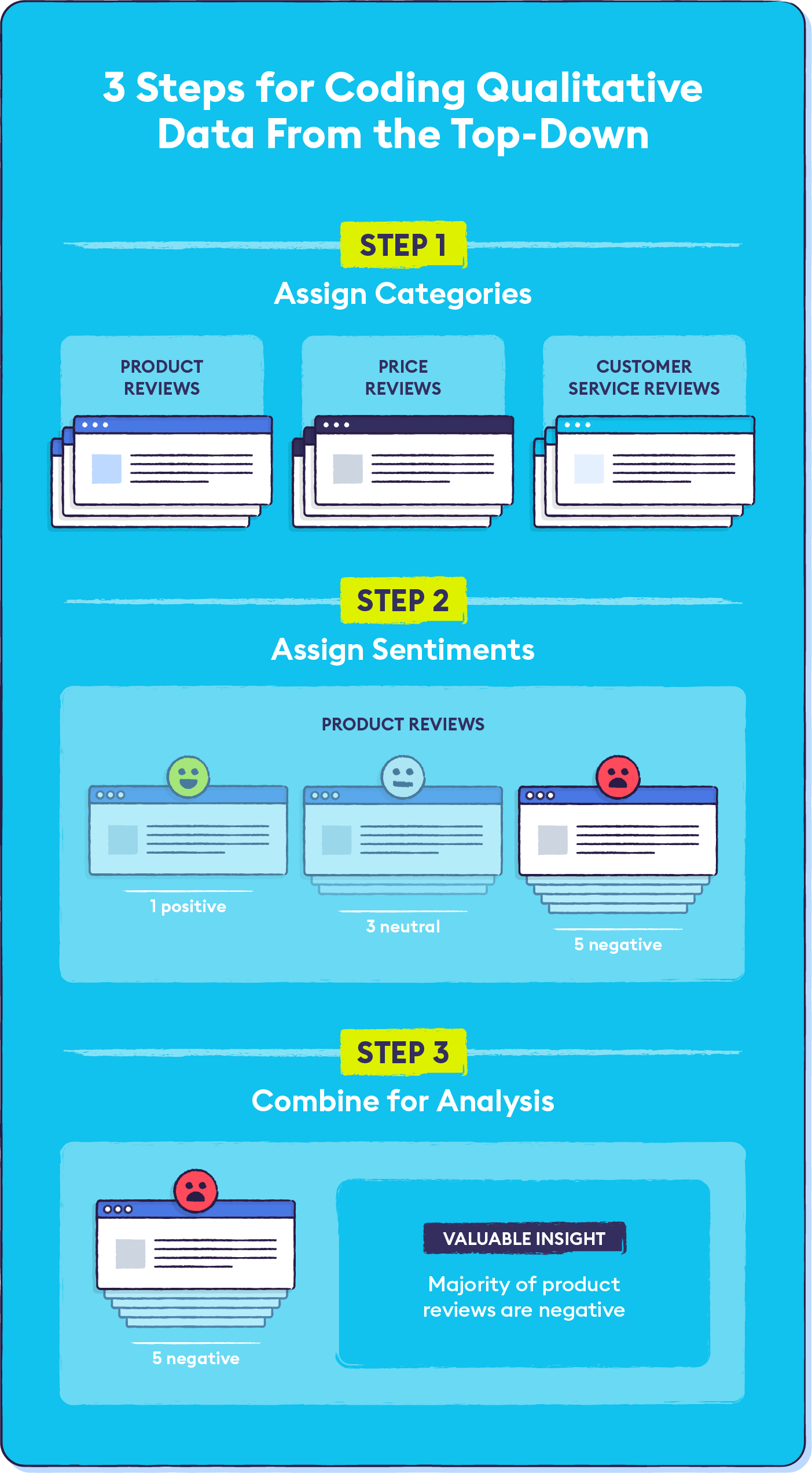

For the rest of this post, we'll focus on manual coding. Different researchers have different processes, but manual coding usually looks something like this:

- Choose whether you'll use deductive or inductive coding.

- Read through your data to get a sense of what it looks like. Assign your first set of codes.

- Go through your data line-by-line to code as much as possible. Your codes should become more detailed at this step.

- Categorize your codes and figure out how they fit into your coding frame.

- Identify which themes come up the most — and act on them.

Let's break it down a little further…

Deductive coding vs. inductive coding

Before you start qualitative data coding, you need to decide which codes you'll use.

What is Deductive Coding?

Deductive coding means you start with a predefined set of codes, then assign those codes to the new qualitative data. These codes might come from previous research, or you might already know what themes you're interested in analyzing. Deductive coding is also called concept-driven coding.

For example, let's say you're conducting a survey on customer experience . You want to understand the problems that arise from long call wait times, so you choose to make “wait time” one of your codes before you start looking at the data.

The deductive approach can save time and help guarantee that your areas of interest are coded. But you also need to be careful of bias; when you start with predefined codes, you have a bias as to what the answers will be. Make sure you don't miss other important themes by focusing too hard on proving your own hypothesis.

What is Inductive Coding?

Inductive coding , also called open coding, starts from scratch and creates codes based on the qualitative data itself. You don't have a set codebook; all codes arise directly from the survey responses.

Here's how inductive coding works:

- Break your qualitative dataset into smaller samples.

- Read a sample of the data.

- Create codes that will cover the sample.

- Reread the sample and apply the codes.

- Read a new sample of data, applying the codes you created for the first sample.

- Note where codes don't match or where you need additional codes.

- Create new codes based on the second sample.

- Go back and recode all responses again.

- Repeat from step 5 until you've coded all of your data.

If you add a new code, split an existing code into two, or change the description of a code, make sure to review how this change will affect the coding of all responses. Otherwise, the same responses at different points in the survey could end up with different codes.

Sounds like a lot of work, right? Inductive coding is an iterative process, which means it takes longer and is more thorough than deductive coding. A major advantage is that it gives you a more complete, unbiased look at the themes throughout your data.

Combining inductive and deductive coding

In practice, most researchers use a blend of inductive and deductive approaches to coding.

For example, with Thematic, the AI inductively comes up with themes , while also framing the analysis so that it reflects how business decisions are made . At the end of the analysis, researchers use the Theme Editor to iterate or refine themes. Then, in the next wave of analysis, as new data comes in, the AI starts deductively with the theme taxonomy.

Categorize your codes with coding frames

Once you create your codes, you need to put them into a coding frame. A coding frame represents the organizational structure of the themes in your research. There are two types of coding frames: flat and hierarchical.

Flat Coding Frame

A flat coding frame assigns the same level of specificity and importance to each code. While this might feel like an easier and faster method for manual coding, it can be difficult to organize and navigate the themes and concepts as you create more and more codes. It also makes it hard to figure out which themes are most important, which can slow down decision making.

Hierarchical Coding Frame

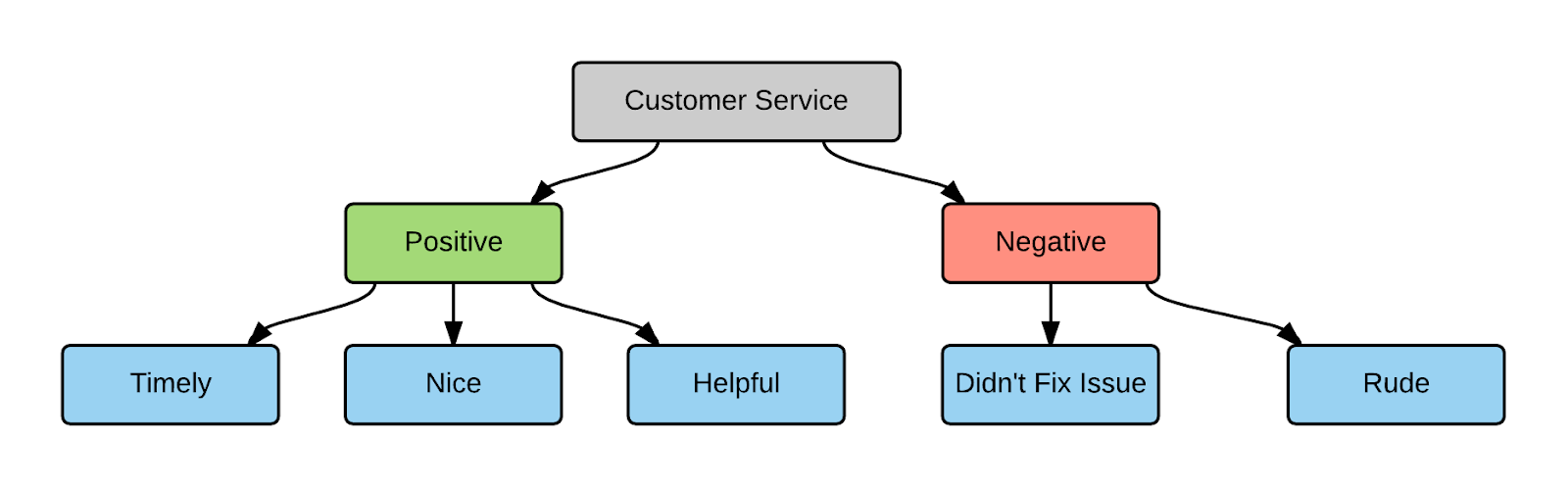

Hierarchical frames help you organize codes based on how they relate to one another. For example, you can organize the codes based on your customers' feelings on a certain topic:

Hierarchical Coding Frame example

In this example:

- The top-level code describes the topic (customer service)

- The mid-level code specifies whether the sentiment is positive or negative

- The third level details the attribute or specific theme associated with the topic

Hierarchical framing supports a larger code frame and lets you organize codes based on organizational structure. It also allows for different levels of granularity in your coding.

Whether your code frames are hierarchical or flat, your code frames should be flexible. Manually analyzing survey data takes a lot of time and effort; make sure you can use your results in different contexts.

For example, if your survey asks customers about customer service, you might only use codes that capture answers about customer service. Then you realize that the same survey responses have a lot of comments about your company's products. To learn more about what people say about your products, you may have to code all of the responses from scratch! A flexible coding frame covers different topics and insights, which lets you reuse the results later on.

Tips for manually coding qualitative data

Now that you know the basics of coding your qualitative data, here are some tips on making the most of your qualitative research.

Use a codebook to keep track of your codes

As you code more and more data, it can be hard to remember all of your codes off the top of your head. Tracking your codes in a codebook helps keep you organized throughout the data analysis process. Your codebook can be as simple as an Excel spreadsheet or word processor document. As you code new data, add new codes to your codebook and reorganize categories and themes as needed.

Make sure to track:

- The label used for each code

- A description of the concept or theme the code refers to

- Who originally coded it

- The date that it was originally coded or updated

- Any notes on how the code relates to other codes in your analysis

How to create high-quality codes - 4 tips

1. cover as many survey responses as possible..

The code should be generic enough to apply to multiple comments, but specific enough to be useful in your analysis. For example, “Product” is a broad code that will cover a variety of responses — but it's also pretty vague. What about the product? On the other hand, “Product stops working after using it for 3 hours” is very specific and probably won't apply to many responses. “Poor product quality” or “short product lifespan” might be a happy medium.

2. Avoid commonalities.

Having similar codes is okay as long as they serve different purposes. “Customer service” and “Product” are different enough from one another, while “Customer service” and “Customer support” may have subtle differences but should likely be combined into one code.

3. Capture the positive and the negative.

Try to create codes that contrast with each other to track both the positive and negative elements of a topic separately. For example, “Useful product features” and “Unnecessary product features” would be two different codes to capture two different themes.

4. Reduce data — to a point.

Let's look at the two extremes: There are as many codes as there are responses, or each code applies to every single response. In both cases, the coding exercise is pointless; you don't learn anything new about your data or your customers. To make your analysis as useful as possible, try to find a balance between having too many and too few codes.

Group responses based on themes, not words

Make sure to group responses with the same themes under the same code, even if they don't use the same exact wording. For example, a code such as “cleanliness” could cover responses including words and phrases like:

- Looked like a dump

- Could eat off the floor

Having only a few codes and hierarchical framing makes it easier to group different words and phrases under one code. If you have too many codes, especially in a flat frame, your results can become ambiguous and themes can overlap. Manual coding also requires the coder to remember or be able to find all of the relevant codes; the more codes you have, the harder it is to find the ones you need, no matter how organized your codebook is.

Make accuracy a priority

Manually coding qualitative data means that the coder's cognitive biases can influence the coding process. For each study, make sure you have coding guidelines and training in place to keep coding reliable, consistent, and accurate .

One thing to watch out for is definitional drift, which occurs when the data at the beginning of the data set is coded differently than the material coded later. Check for definitional drift across the entire dataset and keep notes with descriptions of how the codes vary across the results.