Software Engineering Institute

Cite this post.

AMS Citation

McAllister, J., 2016: Cyber Intelligence and Critical Thinking. Carnegie Mellon University, Software Engineering Institute's Insights (blog), Accessed September 13, 2024, https://insights.sei.cmu.edu/blog/cyber-intelligence-and-critical-thinking/.

APA Citation

McAllister, J. (2016, February 15). Cyber Intelligence and Critical Thinking. Retrieved September 13, 2024, from https://insights.sei.cmu.edu/blog/cyber-intelligence-and-critical-thinking/.

Chicago Citation

McAllister, Jay. "Cyber Intelligence and Critical Thinking." Carnegie Mellon University, Software Engineering Institute's Insights (blog) . Carnegie Mellon's Software Engineering Institute, February 15, 2016. https://insights.sei.cmu.edu/blog/cyber-intelligence-and-critical-thinking/.

IEEE Citation

J. McAllister, "Cyber Intelligence and Critical Thinking," Carnegie Mellon University, Software Engineering Institute's Insights (blog) . Carnegie Mellon's Software Engineering Institute, 15-Feb-2016 [Online]. Available: https://insights.sei.cmu.edu/blog/cyber-intelligence-and-critical-thinking/. [Accessed: 13-Sep-2024].

BibTeX Code

@misc{mcallister_2016, author={McAllister, Jay}, title={Cyber Intelligence and Critical Thinking}, month={Feb}, year={2016}, howpublished={Carnegie Mellon University, Software Engineering Institute's Insights (blog)}, url={https://insights.sei.cmu.edu/blog/cyber-intelligence-and-critical-thinking/}, note={Accessed: 2024-Sep-13} }

Cyber Intelligence and Critical Thinking

Jay mcallister, february 15, 2016.

In June, representatives of organizations in the government, military, and industry sectors--including American Express and PNC--traveled to Pittsburgh to participate in a crisis simulation the SEI conducted. The crisis simulation--a collaborative effort involving experts from the SEI's Emerging Technology Center (ETC) and CERT Division --involved a scenario that asked members to sift through and identify Internet Protocol (IP) locations of different servers, as well as netflow data. Participants also sorted through social media accounts from simulated intelligence agencies, as well as fabricated phone logs and human intelligence. Our aim with this exercise was to help cyber intelligence analysts from various agencies learn to think critically about the information they were digesting and make decisions that will protect their organizations in the event of a cyber attack or incident and increase resilience against future incidents. This blog post, the second in a series highlighting cyber intelligence work from the ETC , highlights the importance of critical thinking in cyber intelligence, as well as a three-step approach to taking a more holistic view of cyber threats.

The importance of applying critical thinking to cyber intelligence cannot be overstated. In our work with organizations, we have noticed that when a new threat arises, instead of holistically assessing it, organizations often simply request the latest, greatest analytic tool or contract out the work to third-party intelligence providers. As a former intelligence analyst--prior to joining the SEI, I served as a counterintelligence and counterterrorism analyst for the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) --I know from experience that the operational tempo required for intelligence analysts to keep pace with the ever-changing cyber environment is overwhelming at best. While technology and external resources offer value, analysts also need to critically assess the information they receive.

In 2013, the Defense Science Board echoed a similar sentiment. In their report, Resilient Military Systems and the Advanced Cyber Threat they included the following among their recommendations to improve DoD systems' resilience: "Refocus intelligence collection and analysis to understand adversarial cyber capabilities, plans and intentions, and to enable counterstrategies."

Foundations of Our Work

Our work in cyber intelligence started in 2012 with a request from the government to assess the state of the practice of cyber intelligence. Our work on that initial project involved an examination of the cyber intelligence practices of 30 organizations (6 from government and 24 from industry), specifically their strategic approaches to cyber intelligence. Our work focused on identifying the methodologies, processes, tools and training that shaped how these organizations assessed and analyzed cyber threats. As detailed in an earlier blog post , our work on this project resulted in an implementation framework that captured best practices.

When this work concluded, several participant organizations approached the ETC about leading an effort that would research and develop technical solutions and analytical practices to help people make better judgments and quicker decisions with cyber intelligence. As a result, ETC launched the Cyber Intelligence Research Consortium .

The first year of this consortium focused primarily on continuing our research in cyber intelligence, as well as identifying best practices and challenges. Nearly four years after our initial research began, we have noted clear examples of a strategic shift among participant organizations with respect to cyber intelligence. They are investing resources in hiring intelligence analysts from a pool of vetted and qualified experts, and they are investing significant resources in acquiring tools and tradecraft. However, they are not yet making effective use of the intelligence provided by these resources.

In both government and industry, organizational resilience in the wake of an attack relies on an analyst's ability to holistically assess a threat. The remainder of this post proposes a three-step approach for holistically approaching a cyber threat.

Three Steps to Holistically Assess Cyber Threats

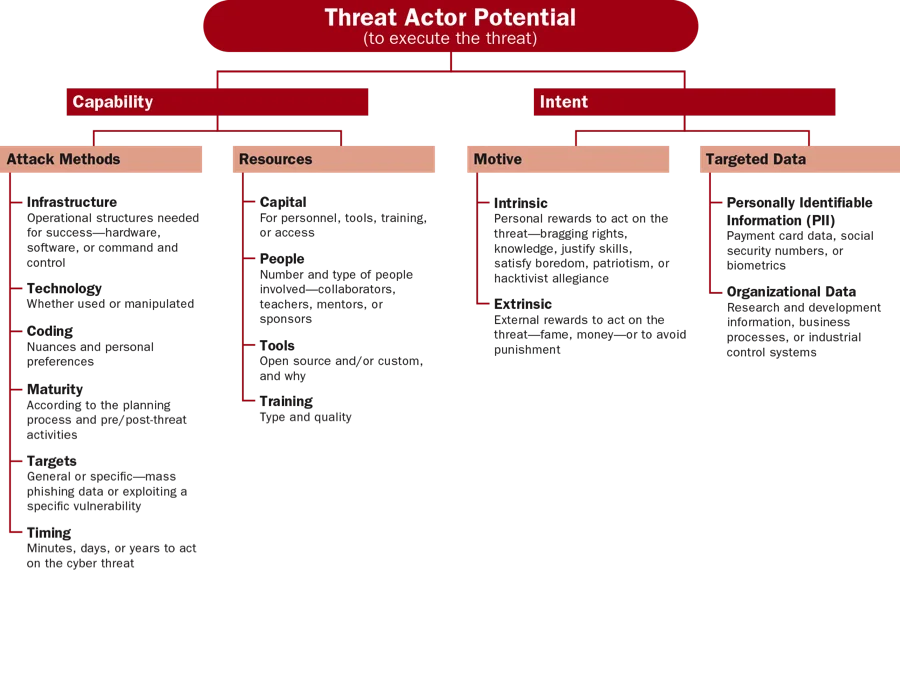

First and foremost, applying critical thinking--which brings together all the skills shown in the "conceptual framework" above--to cyber threats improves an analyst's ability to accurately evaluate and estimate a threat's potential to impact and expose its target. My ETC colleagues and I propose a three-step approach to holistically assess cyber threats:

- Establish a baseline of how the threat will be analyzed . This step involves outlining the approach so that the analyst uses all the skills represented in the conceptual framework . Since the framework is non-linear, the components can be approached in whatever order makes sense.

- Leverage creative brainstorming. When facing a potential cyber threat, analysts don't have the luxury of time to stare into space and wait for an "ah ha" moment. Creative brainstorming techniques such as those found in human-centered design accelerate the time it takes to get to an "ah ha" moment. To enhance an analyst's creative brainstorming skills, I recommend looking at recent brainstorming research including that by Luma Institute , specifically their 36 techniques for creative brainstorming and practice them daily.

- Perform the holistic threat assessment. The assessment evaluates the threat from the three perspectives shown in the figures below:

The three steps outlined in this approach enable analysts to avoid intelligence tunnel vision and seek to understand all causes and effects of relevant threats, which can significantly improve the efficiency and effectiveness of cyber intelligence efforts.

Two Case Studies

This section presents two examples of how a holistic approach to cyber intelligence improved an organization's ability to counteract cyber threat.

- A civil service federal government agency was monitoring open source publications from an entity known to sponsor cyber threat actors who frequently targeted the agency. By examining threat actor potential, organizational impact, and target exposure, the agency came to understand the motivations of the sponsored cyber threat actors, what effects a successful attack might have on the organization, and what vulnerabilities existed that exposed the agency to the threat. This approach enabled the agency's analysts to narrow down the types of data likely to be targeted, to work with network security experts to create diversions and honey pots , and to proactively defend against the threat.

- An organization we worked with from the retail sector focused on the extracurricular activities of its CEO, who was active with companies, non-profits, and policy institutes in a capacity that had nothing to do with his responsibilities at the retail company. The company's cyber intelligence analysts knew this and maintained an awareness of his activities, so when hacktivists publicly threatened attacks against one of the institutes, the analysts knew this could have implications for the retail organization. This attention to target exposure (their CEO's connection with a targeted entity), along with an examination of threat actor potential and organizational impact, enabled analysts to prepare for and successfully stop the attack that eventually happened.

Wrapping Up and Looking Ahead

While the ETC will continue in its efforts to combat the dizzying operational tempo of cyber intelligence with technology, it is equally important to focus on enhancing analytical brainpower. As intelligence analysis pioneer Dr. Richards J. Heuer once observed,

Analysts at all levels devote little attention to improving how they think. To penetrate the heart and soul of improving analysis, it is necessary to better understand, influence, and guide the mental processes of analysts themselves.

There is an elegance involved in designing, developing, and delivering ways for analysts to enhance critical thinking skills. We are working on several fronts to help intelligence analysts acquire these skills:

- I teach a graduate-level strategic cyber intelligence course through Carnegie Mellon's Information Networking Institute (INI); the second offering of the course wrapped up at the end of the fall semester, and I plan to teach it again in Fall 2016. In that class, I emphasize the importance of taking a holistic approach to analyzing cyber threats. My colleague, Jared Ettinger, and I also are working with INI to develop a second cyber intelligence course to be taught for the first time in spring 2017.

- Our Cyber Intelligence Research Consortium is continuing to meet and work on real cyber intelligence problems facing real organizations. We will hold a tradecraft lab in April featuring cyber intelligence experts, discussion amongst members, and output of student projects being run through CMU's Heinz College about cyber intelligence strategy. We are also in the early stages of planning for another crisis simulation for August 2016.

We welcome your feedback on this research and suggestions for future posts in the comments section below.

Additional Resources

View the slides for my presentation, Be Like Water Applying Analytical Adaptability to Cyber Intelligence , which I presented at the 2015 RSA Conference.

Learn more about the ETC's Cyber Intelligence Research Consortium .

Digital Library Publications

Send a message, get updates on our latest work..

Sign up to have the latest post sent to your inbox weekly.

Each week, our researchers write about the latest in software engineering, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. Sign up to get the latest post sent to your inbox the day it's published.

Critical Thinking and Effective Communication in Security Domains

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 21 January 2022

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Cihan Aydiner 2

59 Accesses

This chapter explores the critical thinking and effective communication skills in security domains both for educational and professional settings. The literature shows the gap among research, learning goals, teaching, and practice of critical thinking and effective communication skills in education and training. So, this study aims to create a starting guidance document to improve these skills in security domains with a direct approach. This study conceptualizes these skills as shown in the literature and shows the barriers as well as strategies to prevent barriers for critical thinking and effective communication developments. Also, it provides examples to teach these skills in security domains by asking appropriate questions, using selected red teaming techniques, and discussing recommendations for effective communication. This study asserts that direct approaches to teaching and applying critical thinking and effective communication skills may be more productive than indirect approaches in education and practice. Also, the chapter argues that supporting direct strategies by providing required resources to faculty and professionals in the field is an essential step for effective teaching of these skills. Further studies are encouraged to provide specific and practical examples to develop critical thinking and effective communication skills in subfields of security domains.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Making Waves Through Education: A Method for Addressing Security Grand Challenges in Educational Contexts

Developing an effective and comprehensive communication curriculum for undergraduate medical education in Poland – the review and recommendations

Ackerman GA, Clifford D (2019) Towards a definition of red teaming. Center for advanced red teaming. University at Albany, Albany. Available via https://www.albany.edu/sites/default/files/2019-11/CART%20Definition.pdf . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Google Scholar

Bailenson JN (2021) Nonverbal overload: a theoretical argument for the causes of zoom fatigue. Technol Mind Behav. Available via https://tmb.apaopen.org/pub/nonverbal-overload/release/2 . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Bailin S, Case R, Coombs JR, Daniels LB (1999) Conceptualizing critical thinking. J Curric Stud:285–302

Baybutt P (2016) A framework for critical thinking in process safety management. Process Saf Prog:337–340. Available via https://aiche-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ezproxy.libproxy.db.erau.edu/doi/10.1002/prs.11858 . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Bellaera L, Weinstein-Jones Y, Ilie S, Baker ST (2021) Critical thinking in practice: the priorities and practices of instructors teaching in higher education.. Thinking Skills and Creativity. Available via https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1871187121000717 . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Betts K (2009) Lost in translation: importance of effective communication in online education. Online J Distance Learn Adm 12:2. Available via https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ869279 . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Bloom BS (1956) Taxonomy of educational objectives. Handbook I: the cognitive domain. David McKay Co. Inc., New York

Bloom BS (1973) Taxonomy of educational objectives, the classification of educational goals. Handbook II: the affective domain. David McKay Co. Inc., New York

Browne MN, Keeley SM (2018) Asking the right questions: a guide to critical thinking, 12th edn. Pearson, New York

Cozine K (2015) Thinking interestingly: the use of game play to enhance learning and facilitate critical thinking within a homeland security curriculum. Br J Educ Stud 63(3):367–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2015.1069256

Article Google Scholar

DeFilippis E, Impink SM, Singell M, Polzer JT, Sadun R (2020) Collaborating during coronavirus: the impact of COVID-19 on the nature of work. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working paper 27612. Available via https://www.nber.org/papers/w27612 . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Erickson BL, Peters CB, Strommer DW (2006) Teaching first-year college students: revised and expanded edition of teaching college freshmen. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Erikson MG, Erikson M (2019) Learning outcomes and critical thinking – good intentions in conflict. Stud High Educ 44(12):2293–2303. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1486813

Glaser EM (1941) An experiment in the development of critical thinking. Teacher’s College, Columbia University

Griffin RW (2016) Fundamentals of management. South-Western Cengage Learning, Mason

Isaias P, Issa T (2014) Promoting communication skills for information systems students in Australian and Portuguese higher education: action research study. Educ Inf Technol 19:841–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-013-9257-9

Joly H, Lambert C (2021) The heart of business: leadership principles for the next era of capitalism. Harvard Business Review Press, Boston

Jonassen DH (2000) Toward a design theory of problem solving. Educ Technol Res Dev 48(4):63–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02300500

Kardos M, Dexter P (2017) A simple handbook for non-traditional red teaming, Australian Government Department of Defense, Joint & Operations Analysis Division, 26. Available via https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/1027344.pdf . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Kiltz L (2009) Developing critical thinking skills in homeland security and emergency management courses. J Homel Secur Emerg Manag 6(1):1–25

Klemmer ET, Snyder FW (2006) Measurement of time spent communicating. J Commun 22(2):142–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1972.tb00141.x

Knight R, Nurse JRC (2020) A framework for effective corporate communication after cyber security incidents. Comput Secur J 99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2020.102036 . Available via https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167404820303096 . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Kurfiss J (1988) Critical thinking theory, research, practice and possibilities. ASHE-ERIC higher education report, no 2. Association for Study for Higher Education, Washington, DC. Available via https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED304041 . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Lai ER (2011) Critical thinking: a literature review . Available via Pearson http://images.pearsonassessments.com/images/tmrs/CriticalThinkingReviewFINAL.pdf . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Landry T (2017) Embracing the devil: an analysis of the formal adoption of red teaming in the security planning for major events. Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California. Available via https://www.hsaj.org/articles/13948 . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Matherly C (2013) The red teaming essential. Social psychology premier for adversarial based alternative analysis. American Military University, Charles Town. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299135949_The_Red_Teaming_Essential_Social_Psychology_Premier_for_Adversarial_Based_Alternative_Analysis . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Mousena E, Raptis N (2020) Beyond teaching: school climate and communication in the educational context. Intechopen Book Series. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.93575 . Available via https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/73237 . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking Instruction (2021) Available via https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/critical-thinking-where-to-begin/796 . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Patry J (1996) Critical thinking handbook. Foundation for Critical Thinking, Rohnert Park

Paul R, Elder L (2000) Critical thinking handbook: basic theory and instructional structures. Available via http://www.criticalthinking.org.resources/articles/therole-of-questions.html . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Paul R, Elder L (2005) The miniature guide to critical thinking: concepts and tools. The Foundation for Critical Thinking. Available via https://www.criticalthinking.org/files/Concepts_Tools.pdf . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Ragazzi F (2016) The Paris attacks: magical thinking & hijacking trust. Crit Stud Secur 4(2):225–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/21624887.2016.1216051

Ramsay JD, Tanali Irmak R (2018) Development of competency-based education standards for homeland security academic programs. J Homel Secur Emerg Manag 15(3):1–27

Retz K (2020) The professional skills handbook for engineers and technical professionals. CRC Press, Boca Raton. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780367853099

Book Google Scholar

Safi A, Burell D (2007) Developing critical thinking leadership skills in homeland security professionals, law enforcement agents and intelligence analysts. Homel Defense J. Available via https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/developing-critical-thinking-leadership-skills-homeland-security . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Saltzman B (2021) Critical thinking for more effective communication: fueling your communication engine with critical thinking. LinkedIn Learning. Available via https://www.linkedin.com/learning/critical-thinking-for-more-effective-communication/fueling-your-communication-engine-with-critical-thinking?autoAdvance=true&autoSkip=false&autoplay=true&resume=false&u=26194554 . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Stansberry S, Haulmark M, Sheeran L (2003) “I agree” does not constitute discussion: applying theoretical frameworks to assess student learning in asynchronous online discussions. Natl Soc Sci J 20(1) Available via: http://www.nssa.us/nssajrnl/20_1/html/stansberry_I_agree_pub_format.htm . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Stauffer B (2020) What are the 4 C’s of 21st century skills? Applied Educational Systems. Available via https://www.aeseducation.com/blog/four-cs-21st-century-skills . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Taylor TZ, Prescott R, Harrup K (2021) Developing critical thinking skills among transportation security officers (TSOs) through sharing tacit knowledge. J Transport Secur 14:107–118. Available via https://doi-org.ezproxy.libproxy.db.erau.edu/10.1007/s12198-021-00231-9 . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

The Center for Homeland Defense and Security's University and Agency Partnership Program (CHDS) (2020). UAPP programs and resources. Available via https://www.uapi.us/programs/2077 . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Thonney T, Montgomery JC (2019) Defining critical thinking across disciplines: an analysis of community college faculty perspectives. Coll Teach 67(3):169–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2019.1579700

Tutorialspoint (2016) Effective communication. Available via https://www.tutorialspoint.com/effective_communication/effective_communication_tutorial.pdf . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

United Kingdom Ministry of Defence (MOD) (2021) Red teaming guide, 3rd edn Available via https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1027158/20210625-Red_Teaming_Handbook.pdf . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

United States Government US Army (2016) Command red team, joint doctrine note JDN 1–16 command red team 16. Available via https://irp.fas.org/doddir/dod/jdn1_16.pdf . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

United States. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) (2021) IS-242.C: effective communication instructor guide. Available via https://training.fema.gov/is/courseoverview.aspx?code=IS-242.c . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies (2018) The Red Team Handbook (Applied Critical Thinking Handbook). ver. 9.0. UFMCS, Fort Leavenworth. Available via https://usacac.army.mil/sites/default/files/documents/ufmcs/The_Red_Team_Handbook.pdf . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

World Economic Forum (2020) The future of jobs report 2020. Available via https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2020/in-full/infographics-e4e69e4de7 . Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Zenko M (2015) Red team: how to succeed by thinking like the enemy. Basic Books, New York

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Security and Emergency Services, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University – Worldwide, Daytona Beach, FL, USA

Cihan Aydiner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cihan Aydiner .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

College of Public Health, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

Anthony J. Masys

Section Editor information

The Pennsylvania State University (Penn State), Penn State Harrisburg, School of Public Affairs, Middletown, PA, USA

Alexander Siedschlag

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Aydiner, C. (2022). Critical Thinking and Effective Communication in Security Domains. In: Masys, A.J. (eds) Handbook of Security Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51761-2_2-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51761-2_2-1

Received : 11 December 2021

Accepted : 18 December 2021

Published : 21 January 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-51761-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-51761-2

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Physics and Astronomy Reference Module Physical and Materials Science Reference Module Chemistry, Materials and Physics

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Active Directory Attack

- Network Attack

- Mitre Att&ck

- E-Mail Attack

CVE-2023-21554 – Hunt For MSMQ QueueJumper In The Environment

Os credential dumping- lsass memory vs windows logs, credential dumping using windows network providers – how to respond, the flow of event telemetry blocking – detection & response, uefi persistence via wpbbin – detection & response, what is session hijacking/cookie hijacking – demo, linux event logs and its record types – detect & respond, how businesses can minimize network downtime, recovering sap data breaches caused by ransomware, how does dga malware operate and how to detect in a…, how to optimize business it infrastructure, how businesses can identify and address cybersecurity lapses , cybersecurity management 101: balancing risk management with compliance requirements, remote desktop gateway – what is it, how to detect malware c2 with dns status codes, how brazilian students use ai, tools online casinos use to protect players, vdr — a space for efficient and secure transactions, how encryption plays a vital role in safeguarding against digital threats, push notification protocols: ensuring safety in digital communication, phishing scam alert: fraudulent emails requesting to clear email storage space…, vidar infostealer malware returns with new ttps – detection & response, new whiskerspy backdoor via watering hole attack -detection & response, redline stealer returns with new ttps – detection & response, understanding microsoft defender threat intelligence (defender ti), threat hunting playbooks for mitre tactics, masquerade attack part 2 – suspicious services and file names, masquerade attack – everything you need to know in 2022, mitre d3fend knowledge guides to design better cyber defenses, mapping mitre att&ck with window event log ids, how email encryption protects your privacy, how to check malicious phishing links, emotet malware with microsoft onenote- how to block emails based on…, how dmarc is used to reduce spoofed emails , hackers use new static expressway phishing technique on lucidchart.

- Editors Pick

Beyond Technical Skills: How Cybersecurity Courses Enhance Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving

In today’s hyper-connected world, cybersecurity is paramount. As the digital sector continues to expand, the demand for proficient cybersecurity professionals has never been greater. Traditionally, the focus in cybersecurity education has been on imparting technical skills to combat cyber threats. While technical proficiency is undeniably crucial, the rapidly evolving threat landscape necessitates a shift towards a more holistic approach.

This article explores the pivotal role of critical thinking and problem-solving in cybersecurity education, emphasizing their significance beyond technical skills.

The Role of Technical Skills in Cybersecurity

- Technical Skills as the Foundation: Technical skills form the cornerstone of cybersecurity knowledge. Proficiency gained through the cybersecurity course in network security, encryption, firewall configuration, and malware analysis is essential for effectively safeguarding digital assets. Without these technical competencies, cybersecurity professionals would be ill-equipped to defend against cyber threats.

- Essential Technical Competencies: Cybersecurity education traditionally emphasizes the mastery of essential technical competencies. These skills enable professionals to understand and mitigate specific threats and vulnerabilities effectively. However, relying solely on technical expertise has its limitations.

- Limitations of a Solely Technical Approach: The cybersecurity landscape is constantly evolving, with attackers adopting new tactics and techniques. Relying solely on technical skills may not be sufficient to adapt to these ever-changing threats. A more comprehensive approach that includes critical thinking and problem-solving is required.

The Expanding Scope of Cybersecurity Threats

- Evolving Nature of Cyber Threats: Cyber threats are dynamic and increasingly sophisticated. Attack vectors have diversified, encompassing not only malware and viruses but also social engineering, phishing attacks, and advanced persistent threats (APTs). The landscape is in a state of constant flux, requiring cybersecurity professionals to remain adaptable.

- Sophisticated Attack Vectors and Tactics: Attackers are using more sophisticated tactics, often employing zero-day vulnerabilities and advanced evasion techniques. These tactics challenge the efficacy of purely technical solutions. Cybersecurity experts must be able to think critically to identify and address emerging threats effectively.

- Adaptation to New Challenges: As the digital environment evolves, so do the challenges faced by cybersecurity professionals. To stay ahead of attackers, professionals need to cultivate critical thinking and problem-solving abilities that extend beyond their technical toolkit.

The Importance of Critical Thinking in Cybersecurity

- Definition and Significance of Critical Thinking: Critical thinking is the capability to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information to make informed decisions. In cybersecurity, it involves the capacity to assess complex situations, identify potential threats, and develop proactive strategies.

- Role of Critical Thinking in Problem Identification: Critical thinking plays a pivotal role in identifying and assessing problems in cybersecurity. It allows professionals to recognize anomalies, vulnerabilities, and potential threats that might go unnoticed by relying solely on technical tools.

- Analyzing Complex Cyber Threats: Cyber threats are often multifaceted and elusive. Critical thinking enables professionals to analyze these threats from multiple angles, helping them to comprehend the broader context and anticipate adversary tactics.

Problem-Solving in Cybersecurity

- The Problem-Solving Process in Cybersecurity: Problem-solving is a structured approach to addressing cybersecurity challenges. It involves defining the problem, generating potential solutions, evaluating those solutions, and implementing the most effective one. Problem-solving is essential for mitigating threats and vulnerabilities effectively.

- Developing Effective Strategies: Cybersecurity professionals must develop effective strategies to counter threats. This includes not only identifying vulnerabilities but also devising comprehensive plans to remediate them. Problem-solving skills are instrumental in crafting and implementing these strategies.

- Real-World Problem-Solving Scenarios: The real world of cybersecurity is rife with complex problems. Professionals often encounter scenarios where critical thinking and problem-solving are required to assess risks, respond to incidents, and protect systems and data effectively.

The Integration of Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving in Cybersecurity Courses

- Incorporating Critical Thinking Exercises and Case Studies: Cybersecurity courses can integrate critical thinking exercises and case studies into their curriculum. These exercises challenge students to apply their analytical skills to real-world scenarios, fostering a deeper understanding of cybersecurity challenges.

- Hands-on Problem-Solving Challenges in Cybersecurity Labs: Practical labs and hands-on challenges provide students with opportunities to apply problem-solving skills. These exercises simulate real threats and incidents, allowing students to develop strategies to mitigate them.

- Thinking Like Attackers to Anticipate Threats: An effective cybersecurity approach involves thinking like an attacker. By analyzing systems and applications from an adversary’s perspective, professionals can better anticipate potential vulnerabilities and preemptively address them.

Benefits of Emphasizing Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving

- Enhanced Adaptability: Critical thinking and problem-solving skills enhance professionals’ adaptability to new and evolving threats. They can quickly assess and respond to emerging challenges, reducing the impact of cyber incidents.

- Improved Decision-Making Under Pressure: In high-pressure situations, such as cyberattacks, professionals with strong critical thinking and problem-solving abilities make better decisions. They can prioritize actions effectively and minimize damage.

- Holistic and Proactive Cybersecurity: A holistic approach to cybersecurity that includes critical thinking and problem-solving goes beyond merely reacting to threats. It enables professionals to proactively identify vulnerabilities and weaknesses, reducing the overall risk landscape.

Case Studies: Success Stories of Critical Thinkers in Cybersecurity

Real-Life Examples of Cybersecurity Professionals: Examining real-life success stories of cybersecurity professionals who excelled due to their critical thinking and problem-solving skills demonstrates the practical application of these abilities. These professionals have demonstrated how these skills can make a difference in the cybersecurity field.

Challenges and Considerations in Incorporating Critical Thinking

- Resistance to Change in Cybersecurity Education: Incorporating critical thinking and problem-solving into cybersecurity education may face resistance, as the field has traditionally emphasized technical skills. Overcoming this resistance requires recognition of the changing threat landscape and the importance of holistic skills.

- Balancing Technical and Non-Technical Skills: Finding the right balance between technical and non-technical skills in the curriculum can be challenging. Cybersecurity education must evolve to ensure that students develop both sets of skills effectively.

- Evaluating and Assessing Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving Abilities: Assessing critical thinking and problem-solving skills can be challenging. Developing effective evaluation methods and metrics is essential to measure these skills accurately.

Preparing the Next Generation of Cybersecurity Professionals

- The Evolving Role of Educators and Institutions: Educators and institutions play a crucial role in preparing the next generation of cybersecurity professionals. They must adapt their curricula to emphasize critical thinking and problem-solving while continuing to provide technical foundations.

- Fostering a Culture of Continuous Learning and Critical Thinking: The cybersecurity industry must foster a culture of continuous learning and critical thinking. Professionals should be encouraged to develop these skills through cybersecurity coursesthroughout their careers to remain effective in addressing new threats.

- The Future of Cybersecurity Education and Its Impact on the Industry: As the threat landscape continues to evolve, cybersecurity education will play a pivotal role in shaping the industry’s future. A focus on critical thinking and problem-solving will be vital to building a workforce capable of defending against emerging cyber threats.

In the ever-changing digital landscape, cybersecurity professionals face an array of complex challenges. While technical skills remain essential, the importance of critical thinking and problem-solving cannot be overstated. Emphasizing these skills in cybersecurity education equips professionals to adapt to evolving threats, make effective decisions under pressure, and develop proactive cybersecurity strategies . As the role of cybersecurity professionals continues to evolve, cultivating these non-technical skills will be crucial for securing the digital world effectively and safeguarding our interconnected society.

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Privacy Policy

- Artificial Intelligence

- Generative AI

- Business Operations

- IT Leadership

- Application Security

- Business Continuity

- Cloud Security

- Critical Infrastructure

- Identity and Access Management

- Network Security

- Physical Security

- Risk Management

- Security Infrastructure

- Vulnerabilities

- Software Development

- Enterprise Buyer’s Guides

- United States

- United Kingdom

- Newsletters

- Foundry Careers

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Member Preferences

- About AdChoices

- E-commerce Links

- Your California Privacy Rights

Our Network

- Computerworld

- Network World

“Thinking About Thinking” is Critical to Cybersecurity

Most cybersecurity vulnerabilities are created by human decisions—many of which aren’t made consciously. here’s why understanding the mental shortcuts we use in decision-making can help strengthen cybersecurity..

Humans make a lot of decisions each day, whether we are aware of them or not. Research shows that people make approximately 200 decisions about food every single day 1 . And, depending on how we define the word “decision,” the daily number can creep into the tens of thousands. Although we may believe our decisions are rational, cognitive scientists argue that we are far less objective than we think. Cognitive biases shape our cybersecurity decisions from the keyboard to the boardroom, and these decisions ultimately determine the effectiveness of our cybersecurity solutions.

Seeing isn’t always believing

Consider the following question: 2

Jack is looking at Anne, but Anne is looking at George. Jack is married, but George is not. Is a married person looking at an unmarried person?

- Cannot be determined

Up to 80% of respondents select “C.” But the correct answer is actually “A.”

It doesn’t matter whether Anne is married or not. If she is married, she is looking at an unmarried person: George. If she is not married, then Jack is looking at an unmarried person: Anne. The reason people often choose “C” is that Anne’s marital status is not provided in the question. In this example, people use a mental shortcut to link Anne’s missing information and “cannot be determined” rather than thinking through multiple options.

Taking mental shortcuts is not limited to tricky logic questions. We use shortcuts so frequently and effortlessly that we do not even realize we’re doing it. However, humans are also capable of engaging in complex analytic thoughts and solving extraordinarily difficult problems.

The Dual Process Theory explains human thought by separating it into two modes: 3

- System 1 is aligned with human intuition. It is characterized by fast, effortless, and emotional thoughts that we unconsciously link with past experiences, thoughts, and patterns.

- System 2 is aligned with analytical and logical thought. It is characterized by effortful thinking and reasoning that we are typically aware of.

Whether we like (or realize) it or not, we spend the vast majority of our lives immersed in System 1 thinking. Our brains use System 1 to optimize the body’s energy—20% of which is going toward brain function. System 1 makes it possible to quickly and effortlessly complete the many simple tasks we engage in throughout the day, such as tying shoes, locating sounds, or avoiding potholes while driving. If we had to depend completely on System 2 and engage in effortful, exact thinking for every decision we faced throughout a day, we might never make it out the front door in the morning.

Although System 1 allows us to function and conserve valuable brainpower, it also creates problems. Our automatic thoughts frequently influence decisions without our awareness—decisions that would be far better suited for a full System 2 analysis. These subconscious influences, or cognitive biases, are systematic departures from logic where rules of thumb supersede the facts at hand.

Decide to do cybersecurity better

Our daily cybersecurity decisions are influenced by our cognitive biases, and while we won’t ever completely escape bias, we can prepare ourselves to make better decisions by thinking about thinking . When we think about thinking, we build awareness of cognitive bias across our organizations, so we can better identify situations where critical decisions and the behaviors they drive are susceptible to increased risk.

Scaling your security strategy to protect remote workers means understanding how workers behave in a remote environment. And Forcepoint is here to help. Visit us to learn more about how risk-adaptive cybersecurity driven by behavioral analytics can secure people and data everywhere.

- Wasink, B. & Sobal, J. (2007). Mindless Eating: The 200 Daily Food Decisions We Overlook. Environment & Behavior, 39, 106-123

- Hector Levasque, as cited by Keith Stanovich, “ Rational and Irrational Thought: The Thinking that IQ Tests Miss ”

- Daniel Kahneman, “ Dual Processing Theory, Heuristics, and Bias”

Related content

Inside-out security: the path to dynamic data protection, building a data protection strategy for remote work, securing innovation in the cloud: best practices for remote development teams, 5 ways to secure data on video conferencing platforms in a remote work environment, from our editors straight to your inbox, show me more, newly patched ivanti csa flaw under active exploitation.

New cryptomining campaign infects WebLogic servers with Hadooken malware

Fortinet confirms breach that likely leaked 440GB of customer data

CSO Executive Sessions: Guardians of the Games - How to keep the Olympics and other major events cyber safe

CSO Executive Session India with Dr Susil Kumar Meher, Head Health IT, AIIMS (New Delhi)

CSO Executive Session India with Charanjit Bhatia, Head of Cybersecurity, COE, Bata Brands

CSO Executive Sessions: DocDoc’s Rubaiyyaat Aakbar on security technology

CSO Executive Sessions: Hong Kong Baptist University’s Allan Wong on security leadership

CSO Executive Sessions: EDOTCO’s Mohammad Firdaus Juhari on safeguarding critical infrastructure in the telecommunications industry

Sponsored Links

- OpenText Financial Services Summit 2024 in New York City!

- Visibility, monitoring, analytics. See Cisco SD-WAN in a live demo.

Security Outside the Box: The Importance of Critical Thinking

Growing up in Nairobi, Kenya, Daniel Mugambi describes his childhood as being “always around computers.” His relationship to them was different than most of ours: instead of spending his hours glued to the screen, he was fascinated by what happened inside the machines. “I would take them apart and try put them back together,” he remembers. Those around him know Mugambi as intensely curious, a trait that goes hand in hand with his ability to think deeply and critically. The same impulses that drove him to understand the inner workings of computers are what make him an excellent future cyber professional. In his own words, “Cybersecurity professionals dedicate their lives to the protection of other’s livelihood and privacy—it’s an honorable duty.”

In the fight against cyber-crime, knowing the laws of cybersecurity isn’t enough. In fact, often laws are nonexistent (at least in the way we think of scientific laws) because the field evolves too quickly for their development. The types of cyber professionals who make it in this ever-evolving field aren’t the students who memorize and are good test takers. “Companies are compromised because hackers are able to think outside the box,” says Mugambi. “They find that one small opportunity and suddenly hold the keys to the kingdom” Hackers succeed because, in thinking outside the box, they find something that hasn’t been thought of before and are able to gain control of entire networks. Likewise, the cyber professionals who succeed are the ones who can think critically—the ones who jump outside the box with hackers and critically examine the situation to find a solution. As a student assistant at Carolina Cyber Center (C3), Daniel Mugambi is one such individual.

As he studies to become a Penetration Tester, Mugambi uses his ability to think critically and operate outside the box to go on the offensive. He explains his field of interest (Penetration Testing) as being able to “measure an organization’s security by hacking into their system. By mimicking a real attacker’s method, we see if the organization’s defenses are up.” Instead of passively allowing attacks to occur, Mugambi creates crisis within a safe context, demonstrating the necessity of critical thinking in the field of cybersecurity. “In cybersecurity, critical thinking is the difference being ten steps ahead of black-hat hackers (the bad guys), or getting hacked—it’s a requirement if we are going to outsmart malicious attacks.” If thinking outside the box is what gives hackers a foothold in our organizations, then we must do more than think originally: we must think critically.

In a country that is “pervasively ill-prepared” (read what Adam Bricker, Executive Director of the Carolina Cyber Center has to say about the Colonial Pipeline attack here ) to protect its critical infrastructure, we need more individuals like Daniel Mugambi. Starting on July 12th, the Carolina Cyber Center begins its Cyber Defense Analyst 6-month cohort for students age 17-21. If you are a critical thinker who believes in protecting our country’s infrastructure, this is for you. Apply before the application deadline to begin your cybersecurity journey and join Daniel Mugambi in protecting our data.

At Carolina Cyber Center, we seek to create cyber professionals of character—individuals with Critical Thinking, Grit, Discipline, Curiosity and Collaboration—whether they begin as an amateur fresh out of high school, mid-life career changers, or are cyber professionals continuing their education. To learn more about what the Carolina Cyber Center offers, visit our website or call us at 828.419.0737.

Carolina Cyber Center of Montreat College

310 Gaither Circle P.O. Box 1267 Montreat, NC 28757

(828) 419-0737

Get Started

No-risk, 30-day money-back guarantee. All instructional materials, labs, certification fees*, books, and range time are included.

Ready to Apply

*First attempt for certification included. The cost for additional certification attempts is the responsibility of the student.

Mastering Essential Soft Skills for Cybersecurity Professionals: A Guide to Implementing the CISO's Strategy

The Soft Side of Cyber Podcast

We launched our first podcast episode on youtube, itunes, spotify, and google play. subscribe and give it a listen today.

Technical expertise is super important in our field. But here's the thing: soft skills are just as crucial when it comes to effectively implementing the boss's strategy. Of course, you might be a whiz at identifying vulnerabilities and responding to threats. Still, without soft skills, you may be unable to maximize your impact on the team, move the needle, and help keep your organization safe.

That's where the Soft Side of Cyber Framework comes in. Our handy guide breaks down the critical soft skills you need to thrive in cybersecurity. In this article, we will explore how you can align your skillset with the framework and make a difference in implementing the CISO's strategy.

Time Management

In the fast-paced world of cybersecurity, effective time management and prioritization are critical to ensuring the most pressing threats and vulnerabilities are addressed promptly. Not to mention, there's always more to do, more demands, and another "critical" thing to deal with. By balancing competing priorities and deadlines, you can maximize your productivity and limited resources.

Effective time management strategies, like setting clear goals, breaking tasks into manageable chunks, and eliminating distractions, can help you stay focused and organized. Time or day blocking, where you schedule out chunks of time to focus intensely on a particular thing, is also a powerful technique for getting things done.

By sharpening your time management and personal organization skills, you'll contribute more effectively to implementing the CISO's strategy and help your organization stay one step ahead of potential threats.

Managing your time and being more efficient is one thing, but you must spend that time on the right things. That's where critical thinking can help.

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is a must-have skill for cybersecurity professionals. It enables you to analyze complex situations, identify potential vulnerabilities, and make well-informed decisions to protect your organization. By honing your critical thinking skills, you'll become a more effective problem solver and contribute to successfully implementing the CISO's strategy.

To sharpen your critical thinking abilities, practice breaking down complex issues into manageable components, question assumptions, and consider multiple perspectives when evaluating potential solutions. Additionally, consciously self-reflect and seek feedback to continuously improve your decision-making process.

Circling back and evaluating your decisions after a certain time to determine if your original assessment was correct and why or why not can help you improve. That process will help you make necessary changes, leading to adaptability.

Adaptability

Adaptability is essential with the amount of change we deal with in this field.

Cybersecurity professionals must be able to quickly adjust their tactics, techniques, and priorities to protect their organization from new risks and vulnerabilities. The latest CVE or zero-day drops, you have to change. Senior leadership has a change of heart about something, and you might need to change. The driver for a change can come from anywhere.

Being adaptable means staying informed about the latest developments and being ready to pivot your approach as needed. This agility allows you to address evolving security challenges and align your efforts with the CISO's strategic objectives.

To enhance your adaptability, embrace a continuous learning mindset and seek opportunities to expand your knowledge and skill set. Stay up-to-date with industry news, attend conferences, and participate in professional training and certification programs. Doing so will prepare you to adjust your strategies and tactics in response to the ever-changing cybersecurity landscape.

Creativity is essential for developing innovative solutions to the dynamic set of problems we face in the field of cybersecurity and keeping pace with evolving threats. Embracing creativity enables you to think outside the box, explore new approaches, and devise unique strategies that align with the CISO's vision and objectives. It's easy to slip into a mindset or cultural trope about not being creative because we work in a technical field, but you have to work against that.

By fostering a creative mindset, you can tap into fresh ideas and perspectives to help your organization stay one step ahead of the risks it faces. Encourage a culture that values creative thinking and supports exploring unconventional ideas. Try things that might fail. This environment will empower your team to challenge assumptions, explore new techniques, and develop more effective cybersecurity strategies per the CISO's plan.

As you implement the CISO's strategy, use your creativity to identify potential gaps in your organization's security posture, develop tailored solutions to address these vulnerabilities, and communicate the value of innovative security initiatives to stakeholders. By leveraging your creative problem-solving skills, you can contribute to a more robust and effective cybersecurity program that aligns with the CISO's vision and bolsters your organization's defenses.

Communication

Communication is essential in almost any field, and cybersecurity is no exception. For us, explaining complex concepts to different audiences is crucial. Therefore, you must adjust your communication style to suit technical and non-technical folks. By keeping it simple, clear, and jargon-free, you'll help others understand the importance of your work and its impact on the organization.

Active listening and empathy are also vital ingredients in effective communication. You build trust and rapport when you actively engage with your audience and show genuine interest in their concerns. Plus, it'll help you spot and address potential security risks more efficiently.

To improve your communication skills, consider joining training programs and workshops or seeking mentorship from experienced professionals. Practice makes perfect, so don't forget to put your communication skills to the test in various settings like team meetings, presentations, and written reports.

Catching up on last week? Check out this reaction video on effective writing skills in cyber .

In the wild world of cybersecurity, threats are constantly evolving and getting trickier. That's why no one person can tackle every challenge alone. Collaboration and teamwork are the secrets to creating effective defense strategies and addressing vulnerabilities. As cybersecurity professionals, we need to work together within our team and across different departments to share knowledge and develop comprehensive solutions.

As you strive to put the CISO's strategy into action, building strong working relationships within your team and across different departments is essential. By fostering a culture of open communication, trust, and collaboration, you can create a united front against cyber threats and ensure that your organization's security measures align with the CISO's vision.

By prioritizing teamwork and collaboration, you'll be better equipped to navigate the complexities of the cybersecurity field, address emerging threats, and effectively contribute to successfully implementing the CISO's strategy.

Leadership isn't just for the top dogs; it's a critical soft skill for all cybersecurity professionals, no matter where they stand in the organization. By showing off your leadership qualities, you'll inspire trust, confidence, and respect among your colleagues and stakeholders, ultimately contributing to a more effective cybersecurity strategy.

Developing a reputation for expertise and reliability is essential to establishing credibility. By consistently delivering high-quality work and showing your commitment to excellence, you'll position yourself as your organization's trusted and valued member.

Don't forget to learn and develop professionally to cultivate your leadership skills continuously. Sit for certifications, attend conferences, and seek opportunities to learn from industry leaders. In addition, you can better guide your organization's cybersecurity efforts by staying current with the latest trends and best practices.

In cybersecurity, persuading decision-makers and stakeholders to invest in and prioritize security efforts is critical to successfully implementing your strategy. To do this effectively, you'll need to hone your persuasion skills, enabling you to convey the importance and value of cybersecurity initiatives compellingly.

By crafting engaging narratives and presenting data-driven arguments, you'll be able to showcase the need for investment in cybersecurity programs and infrastructure that aligns with the CISO's vision. Plus, you'll be able to influence others to adopt a proactive approach to security, ultimately creating a more secure organization that successfully executes the CISO's plan.

By refining your persuasion skills and using them to advocate for the CISO's strategy, you'll help secure the necessary resources, support, and buy-in to create a more resilient and secure organization.

Closing Thoughts

Soft skills are essential for cybersecurity staff like you. By honing these skills, you'll be way more effective at implementing the CISO's strategy and contributing to your organization's security and success. The Soft Side of Cyber Framework is your go-to guide for leveling up your personal and professional growth in the cybersecurity field.

Just think about the impact you can have by improving your soft skills. Not only will you boost your career prospects, but you'll also play a huge role in strengthening your organization's security posture. So, embrace that ongoing commitment to personal and professional growth in cybersecurity, and become the driving force for positive change your organization needs!

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.

You might also like, customer-centric cybersecurity: a service excellence guide.

Business enablement, customer service, and empowering the end user are all terms or phrases we throw around in cybersecurity. Today, we are thrilled to dive deeper into the art of providing exceptional customer service in our ever-evolving cyber landscape. Customer service is talked about in almost every industry, from grocery

Bridging the Gap: A CISO's Guide to Supporting Sales and Marketing with Cybersecurity

Leading a cybersecurity organization is hard. You're not just responsible for security matters, despite what you were told in your interviews. You're expected to help enable the business, support sales and marketing efforts, be a good public representative, be a key component of any digital transformation

- New Zealand

- United States

- United Kingdom

Sharpening Your Critical Thinking Skills: Approaches and Exercises for Cyber Security Experts

Stay Informed With Our Weekly Newsletter

Receive crucial updates on the ever-evolving landscape of technology and innovation.

By clicking 'Sign Up', I acknowledge that my information will be used in accordance with the Institute of Data's Privacy Policy .

Cyber security has become an essential concern for individuals and organisations in today’s rapidly evolving digital landscape.

Critical thinking skills are crucial for cyber security experts as they face increasingly complex challenges and ever-changing threats.

Critical thinking skills in cyber security

Critical thinking is not just an optional skill—it is a necessity when it comes to cyber security.

As cyber attacks become more sophisticated and frequent , professionals in this field must be able to think critically in the face of uncertainty, ambiguity, and complexity.

Critical thinking enables cyber security experts to assess risks, evaluate evidence, and make informed decisions that protect individuals and organisations from potential threats .

The role of critical thinking in cyber security

Critical thinking plays a fundamental role in cyber security by enabling professionals to approach problems and scenarios systematically and analytically.

By applying critical thinking, experts can identify system vulnerabilities, evaluate the effectiveness of security measures, and devise strategies to mitigate risks.

Moreover, critical thinking allows for identifying patterns, connections, and potential threats that may go unnoticed by others.

How critical thinking enhances your cyber security skills

Developing critical thinking skills enhances cyber security professionals’ overall effectiveness and efficiency.

By cultivating critical thinking, experts can improve their problem-solving abilities, identify logical fallacies, and distinguish between relevant and irrelevant information.

Additionally, critical thinking enables professionals to think creatively, finding innovative solutions to emerging cyber threats.

Furthermore, critical thinking in cyber security involves anticipating and adapting to rapidly evolving technological advancements.

Cyber security professionals must stay ahead of the curve as technology advances at an unprecedented pace.

By critically evaluating emerging technologies, experts can assess their potential risks and vulnerabilities, enabling them to develop proactive strategies to safeguard against future threats.

Additionally, critical thinking in cyber security extends beyond technical expertise.

It also encompasses the ability to understand cyber criminals’ motivations and tactics.

Professionals can anticipate their next move and develop effective countermeasures by critically analysing their methods and strategies.

This holistic approach to critical thinking ensures that cyber security professionals are well-equipped to tackle the ever-evolving landscape of cyber threats.

Developing critical thinking

Achieving proficiency in critical thinking requires a combination of self-awareness and active practice.

By understanding the key components of critical thinking and employing effective strategies, cyber security experts can elevate their analytical abilities to the next level.

Developing critical thinking is a journey that involves continuous learning and growth.

It is about acquiring knowledge and honing the ability to think critically and make informed decisions in the ever-evolving cyber security landscape.

Embracing a mindset of intellectual curiosity and a willingness to challenge assumptions is vital to fostering a solid foundation in critical thinking.

The key components of critical thinking

At its core, critical thinking involves the skills of analysis, evaluation, and synthesis.

Cyber security professionals must be able to analyse complex situations, evaluate evidence and arguments, and synthesise information to form logical conclusions.

Additionally, critical thinking encompasses traits such as curiosity, objectivity, and persistence, which are essential for effective problem-solving.

Analytical thinking is crucial in cyber security, where professionals dissect intricate systems and identify vulnerabilities.

Evaluation skills are crucial when assessing the credibility of sources and the validity of information, ensuring that decisions are based on sound reasoning.

Synthesising diverse data points and drawing meaningful connections is a hallmark of advanced critical thinking, enabling professionals to devise comprehensive security strategies.

Strategies for improving critical thinking

Improving critical thinking requires intentional effort and practice.

One useful strategy is active questioning, whereby professionals challenge assumptions, evaluate evidence, and explore alternative perspectives.

Another approach is to cultivate a habit of reflection, regularly reviewing past decisions and seeking opportunities to improve.

Furthermore, seeking diverse sources of information and engaging in collaborative discussions can help broaden one’s perspective and enhance critical thinking abilities.

Collaboration significantly enhances critical thinking skills, as it exposes individuals to different viewpoints and methodologies.

Engaging in discussions with peers and experts in the field can help cyber security professionals refine their analytical thinking and learn to approach problems from various angles.

Embracing a culture of continuous improvement and feedback is essential in mastering critical thinking in the dynamic realm of cyber security.

Practical exercises to boost critical thinking

While understanding the theory behind critical thinking is important, practical exercises can significantly enhance one’s thinking ability.

In the field of cyber security, where real-world scenarios demand quick thinking and accurate decision-making, the following exercises can help professionals sharpen their critical thinking.

Brainstorming exercises for better problem-solving

Brainstorming sessions allow cyber security experts to collectively generate ideas, explore potential solutions, and evaluate their viability.

These exercises encourage critical thinking by involving individuals with different perspectives and expertise by fostering a collaborative environment.

Brainstorming exercises stimulate creativity and help professionals consider alternative approaches to cyber security challenges.

Logic puzzles and how they help in cyber security

Logic puzzles are an excellent way to improve critical thinking skills in cyber security.

These puzzles require individuals to think logically, analyse information, and make deductions based on given conditions.

By solving logic puzzles, professionals can enhance their ability to identify patterns, recognise logical fallacies, and apply structured thinking to real-world cyber security scenarios.

Applying critical thinking to cyber security scenarios

The actual value of critical thinking lies in its practical application.

Professionals with strong critical thinking skills can navigate complexities and find effective solutions when faced with cyber security scenarios.

Identifying potential threats through critical thinking

Critical thinking enables professionals to identify potential threats and vulnerabilities others may overlook.

By actively questioning assumptions, analysing system weaknesses, and evaluating behaviour patterns, experts can identify risks and take proactive measures to mitigate them.

Through critical thinking, cyber security professionals can stay one step ahead of cybercriminals, safeguarding individuals and organisations from potential harm.

Using critical thinking for effective cyber security solutions

Effective cyber security solutions require technical expertise and critical thinking abilities.

By applying critical thinking, professionals can assess the effectiveness of existing security measures, illuminate areas for improvement, and devise tailored solutions.

With a critical thinking mindset, cyber security experts can navigate complex systems, consider multiple factors, and make well-informed decisions that enhance overall security.

Maintaining and improving your critical thinking skills

Developing critical thinking skills is ongoing, requiring continuous learning and practice.

To maintain and enhance these skills, cyber security professionals can adopt the following strategies:

Regular practices for honing critical thinking

Consistency is key to honing critical thinking.

Regular practices such as solving puzzles, seeking out challenging problems, and critically evaluating information can help professionals stay sharp and improve their analytical abilities.

Cyber security experts can stay ahead in this ever-evolving field by dedicating time and effort to critical thinking.

The role of continuous learning in critical thinking development

Critical thinking skills are developed through continuous learning.

Staying updated with the latest industry trends, technologies, and best practices expands knowledge and exposes professionals to diverse perspectives and strategies.

Cyber security experts can continuously refine their critical thinking abilities by seeking opportunities to learn and grow and stay at the forefront of their field.

Critical thinking skills are indispensable for professionals in the dynamic and ever-changing cyber security landscape.

Cyber security experts can sharpen their analytical abilities and approach challenges confidently by understanding the importance of critical thinking, adopting effective strategies, and practising practical exercises.

With strong critical thinking, these professionals can protect individuals and organisations from cyber threats and contribute to a more secure digital environment.

Are you considering a career in cyber security?

Whether you are new to tech or a seasoned professional looking for a change, the Institute of Data’s Cyber Security Program offers an in-depth, balanced, hands-on curriculum for IT and non-IT professionals.

To learn more about our 3-month full-time or 6-month part-time remote bootcamps, download the Cyber Security Course Outline .

Want to learn more about our programs? Our local team is ready to give you a free career consultation . Contact us today!

Follow us on social media to stay up to date with the latest tech news

Stay connected with Institute of Data

Iterating Into Artificial Intelligence: Sid’s Path from HR to Data Science & AI

From Curiosity to Cyber Security: Maria Kim’s Path to Protecting the Digital World

Mastering Cyber Security: Ruramai’s Inspiring Journey from Law to Digital Defence

From Passion to Pursuing a New Career: Neil Kripal’s Driven Journey into Software Engineering

© Institute of Data. All rights reserved.

Copy Link to Clipboard

- Corpus ID: 55398599

Critical Thinking Skills and Best Practices for Cyber Security

- Srinivas Nowduri

- Published 2018

- Computer Science, Education

- International Journal of Cyber-Security and Digital Forensics

Tables from this paper

4 Citations

Multi-dimensional cybersecurity education design: a case study, cybersecurity leaders: knowledge driving human capital development, advancing cybersecurity through knowledge conversion: industry-academia interchange in a doctoral program, puzzle-based honors cybersecurity course for critical thinking development, 19 references, a model of critical thinking as an important attribute for success in the 21st century, what is needed to develop critical thinking in schools, critical thinking in the business curriculum, critical thinking framework for any discipline, critical thinking for 21st-century education: a cyber-tooth curriculum, critical thinking in business education, teaching critical awareness in an introductory course., social problems: a critical thinking approach, a taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

7 Pressing Cybersecurity Questions Boards Need to Ask

- Keri Pearlson

- Nelson Novaes Neto

Don’t leave concerns about critical vulnerabilities for tomorrow.

Boards have a unique role in helping their organizations manage cybersecurity threats. They do not have day to day management responsibility, but they do have oversight and fiduciary responsibility. Don’t leave any questions about critical vulnerabilities for tomorrow. Asking the smart questions at your next board meeting might just prevent a breach from becoming a total disaster.

In this article we offer 7 questions to ask to make sure your board understands how cybersecurity is being managed by your organization. Simply asking these questions will also raise awareness of the importance of cybersecurity, and the need to prioritize action.

For every new technology that cybersecurity professionals invent, it’s only a matter of time until malicious actors find a way around it. We need new leadership approaches as we move into the next phase of securing our organizations. For Boards of Directors (BODs), this requires developing new ways to carry out their fiduciary responsibility to shareholders, and oversight responsibility for managing business risk. Directors can no longer abdicate oversight of cybersecurity or simply delegate it to operating managers. They must be knowledgeable leaders who prioritize cybersecurity and personally demonstrate their commitment. Many directors know this, but still seek answers on how to proceed.

- KP Keri Pearlson is the executive director of the research consortium Cybersecurity at MIT Sloan (CAMS). Her research investigates organizational, strategic, management, and leadership issues in cybersecurity. Her current focus is on the board’s role in cybersecurity.

- NN Nelson Novaes Neto is a Partner and CTO at C6 Bank. He is also a Research Affiliate at MIT Sloan School of Management.

Partner Center

Top Skills Required to Start Your Career in Cybersecurity

Have you been thinking of a career in cybersecurity? It certainly is a good time to do so. Cybersecurity is one of the fastest-growing career fields, with strong demand from employers and a shortage of qualified employees. There are opportunities in nearly every industry, offering good salaries with long-term job security.

To start a cybersecurity career or transition into the field, you must do a quick self-assessment. The concepts can be learned, but it will help if you already possess some of the skills for cybersecurity. Anyone with an excellent approach to problem-solving and attention to detail already has entry-level cyber security skills. With the right kind of thinking and a solid work ethic, you could already be well on your way to a fast-paced, rewarding career.

Considering a Career in Cybersecurity: Why Choose It?

Considering any career, whether you’re just entering the workforce or looking for a new job, can raise some concerns. You may wonder if it’s the right move or if you should choose something else. However, there’s never been a better time to start your career in cybersecurity. It’s a career with and opportunities in several different roles. For example, information security analyst jobs are predicted to grow by 32% between now and 2032 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics).

Experts expect cybersecurity hiring to remain strong for the foreseeable future (Fortune, 2023). As companies return to normal following the Covid-19 pandemic, the way business is done has changed. Remote work has gone from a unique case for field salespeople and branch offices to something more common. Today, the cloud connects employees globally like no one could have imagined just a few years ago (Grand View Research, 2023). This increased adoption of the cloud has only increased the need for information security professionals.

Essential Skills for Entering Field Cybersecurity

So, what are the essential skills needed for cyber security? At the top of the list are problem-solving skills. Day in and day out, cybersecurity professionals are called to address complex issues in creative ways. New information security threats always emerge, requiring cybersecurity pros to think quickly and apply their existing knowledge. Attention to detail, strong analytical skills, and the ability to evaluate the most minute details go a long way in a cybersecurity career.

As an information security worker, you’ll need excellent communication skills. You’ll work with many different people in a wide range of roles from nearly every department. The ability to clearly explain security issues, their impact, and how to address them is critical. At specific points, you’ll be required to speak in technical language. At others, you’ll need to explain things in ways that your non-technical co-workers can understand.

Your next move should be to look for a certification that not only equips you with the foundational technical aspects of cybersecurity but also provides thorough hands-on practice. The best courses will provide extensive lab time so that you can learn and practice in real-world scenarios while building problem-solving skills.

Capture the Flag style critical thinking challenges help build the technical skills required for cyber security. In addition to labs and the cyber range, Capture the Flag style critical thinking challenges are a great way to hone your analytical thinking skills while gaining technical experience. EC-Council’s Certified Cybersecurity Technician (C|CT) course features all the components needed to learn essential cybersecurity skills .

Embarking on Your Cybersecurity Certification Journey

The C|CT program balances teaching and practical experience. You’ll learn about the critical issues cybersecurity pros are dealing with right now and then see how they play out in EC-Council’s Cyber Range. As the course covers information security and network principles, the Cyber Range allows you to address real-world threats and attacks.

With 85 hands-on labs in the Cyber Range and Capture the Flag style critical thinking challenges, the C|CT course teaches cybersecurity skills in ways other certifications don’t. You’ll learn fundamental concepts like data security controls, cryptography and public key infrastructure, virtualization, cloud computing, and the threats surrounding them. Using the network assessment techniques and tools that the pros use, the C|CT certification gives you the head start you need to stand out from others starting a cybersecurity career.

How Do You Apply for the C|CT Course?

To apply for the Certified Cybersecurity Technician course, you can leverage EC-Council’s C|CT Scholarship for career starters. Through this initiative, EC-Council aims to make the C|CT course more accessible to a broader spectrum of individuals and encourage talent development in cybersecurity. With this partial cybersecurity scholarship , you may access all of the course materials at no cost, with the exception of a minimal fee for technology and proctoring of exams. Learn more about the scholarship here .

The C|CT allows cybersecurity professionals to develop their skills in various cybersecurity roles. This includes cybersecurity support technicians, ethical hackers, network support specialists, and more.