An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Facts Views Vis Obgyn

- v.4(4); 2012

Teaching professionalism – Why, What and How

Due to changes in the delivery of health care and in society, medicine became aware of serious threats to its professionalism. Beginning in the mid-1990s it was agreed that if professionalism was to survive, an important step would be to teach it explicitly to students, residents, and practicing physicians. This has become a requirement for medical schools and training programs in many countries. There are several challenges in teaching professionalism. The first challenge is to agree on the definition to be used in imparting knowledge of the subjects to students and faculty. The second is to develop means of encouraging students to consistently demonstrate the behaviors characteristic of a professional - essentially to develop a professional identity.

Teaching of professionalism must be both explicit and implicit. The cognitive base consisting of definitions and attributes and medicine’s social contract with society must be taught and evaluated explicitly. Of even more importance, there must be an emphasis on experiential learning and reflection on personal experience. The general principles, which can be helpful to an institution or program of teaching professionalism, are presented, along with the experience of McGill University, an institution which has established a comprehensive program on the teaching of professionalism.

“Teaching professionalism is not so much a particular segment of the curriculum as a defining dimension of medical education as a whole” (Sullivan WM, 2009, p. xi).

Why teach Professionalism?

The past half century has seen major changes in the practice of medicine. The explosion of science and technology, as well as the development of multiple specialties and sub-specialties, has made the profession both more diverse and disease oriented (Starr, 1984). The increased complexity of care and its cost have brought third party payers, either governments or the corporate sector, into the business of health. Society has also changed. Starting in the 1960s all forms of authority were questioned, including the professions (Krause, 1996; Hafferty & McKinley, 1993). Medicine in particular was seen as self serving rather than promoting the public good and was felt to self-regulate poorly with weak standards applied irregularly. There was a feeling that the professions did not deserve the trust or their privileged position in society. As a result medicine began to examine the threats to its professionalism and, starting in the mid-1990s, realized that if professionalism was to survive, action would be required. It was concluded that one important step would be to teach professionalism explicitly to students, residents, and practicing physicians (Cruess & Cruess, 1997a; Cruess & Cruess, 1997b; Cohen, 2006). In many western countries this has become a requirement for accreditation of medical schools and training programs. There has been an amazing increase in the medical literature on professionalism and medicine’s social contract with society, as well as how best to teach and evaluate professionalism (Cruess et al., 2009; Stern, 2005; Hodges et al., 2011).

The Challenges

There are several challenges inherent in teaching professionalism (Cruess et al., 2009; Cruess & Cruess, 2006). The first is to obtain agreement on a definition. The next is how best to impart knowledge of professionalism to students and faculty. Of great importance is how to encourage those behaviors characteristic of a professional (developing a professional identity). Traditionally professionalism was taught by role-models (Wright et al., 1998; Kenny et al., 2003; Cruess et al., 2008). This is still an essential method but it is no longer sufficient. Both faculty, many of whom are role-models, and students should understand the nature of contemporary professionalism. In the literature there are two approaches to teaching professionalism; to teach it explicitly as a series of traits (Swick, 2000) or as a moral endeavor, stressing reflection and experiential learning (Coulehan, 2005; Huddle, 2005). Neither alone is sufficient. Teaching it by providing a definition and listing a series of traits gives students only a theoretical knowledge of the subject. Relying solely on role modeling and experiential learning is selective, often disorganized, and actually represents what was done in the past. Both approaches must be combined in order that students both understand the nature of professionalism and internalize its values (Ludmerer, 1999).

The first step to be taken in teaching professionalism is to teach its cognitive base explicitly. (Cruess et al., 2009; Cruess & Cruess, 2006) This will allow both faculty and students to have the same understanding of the nature of professionalism and share the same vocabulary as they reflect upon it. A medical institution should therefore select and agree on the definition of a profession and its attributes. There is some confusion in the literature on the exact nature of the words profession and professionalism, with some believing that it is difficult to define professionalism as it is too complex and context driven. There are however several definitions available, and all contain similar content (Stern, 2005; Swick, 2000; Steinert et al., 2007; Sullivan and Arnold, 2009; Todhunter et al., 2011). There are also attributes, drawn from the literature, which outline what is expected of a medical professional and these can form the basis of identifying the behaviors which reflect these attributes (Cruess et al., 2009).

Profession and Professionalism

The literature contains many definitions which can serve as the basis of the teaching of professionalism. While the arrangement of the words may vary, the content of these definitions is remarkably similar. The International Charter on Medical Professionalism (Brennan et al., 2002), the Royal College of Physicians of London (2005), Swick (2000), Stern (2005) and others have published acceptable definitions. We developed and published the following definition of profession which has served us well in our teaching programs (Cruess et al., 2004).

Profession: An occupation whose core element is work based upon the mastery of a complex body of knowledge and skills. It is a vocation in which knowledge of some department of science or learning or the practice of an art founded upon it is used in the service of others. Its members are governed by codes of ethics and profess a commitment to competence, integrity and morality, altruism, and the promotion of the public good within their domain. These commitments form the basis of a social contract between a profession and society, which in return grants the profession a monopoly over the use of its knowledge base, the right to considerable autonomy in practice and the privilege of self-regulation. Professions and their members are accountable to those served, to the profession and to society.

Professionalism as a term is obviously derived from the word profession. The definition provided by the Royal College of Physicians of London is useful for teaching (2005).

Professionalism: A set of values, behaviors, and relationships that underpins the trust that the public has in doctors.

We believe that physicians serve two separate but interlocking roles as they practice medicine, those of the healer and the professional ( Figure 1 ). While they cannot be separated in practice, for teaching purposes it is useful to distinguish them (Cruess et al., 2009). The healer has been present since before recorded history and the characteristics of the healer appear to be universal. In every society those who are ill wish healers to demonstrate competence, caring and compassion, and treat them as individuals. While the word profession has been used since the time of Hippocrates, the modern professions arose in the guilds and universities of medieval England and Europe (Starr, 1984; Hafferty & McKinley, 1993). The medical profession had little impact on society until science provided a base for modern medicine and the Industrial Revolution provided sufficient wealth so that health care could actually be purchased. At this time, society turned to the pre-existing professions and organized the delivery of healthcare around them by granting licensure. This provided a monopoly over practice, considerable autonomy, the privilege of self-regulation, and financial rewards. The attributes of the healer and of the professional are shown in Figure 2 . Together, they outline societal expectations of individual physicians and the medical profession under medicine’s social contract.

The definitions and list of attributes which serve as the basis of the cognitive base should be taught as early as possible in the curriculum and expanded in later sessions to reinforce the knowledge base and provide experience in using the vocabulary. As students gain experience, the concept of the social contract between society and medicine (Cruess & Cruess, 2008) can be introduced. Sociologists tell us that society uses professions to organize the essential complex services that it requires, including those of the healer. It has been described by Klein (2006) as a “bargain” in which medicine is granted prestige, autonomy, the privilege of self-regulation and rewards on the understanding that physicians will be altruistic, self-regulate well, be trustworthy, and address the concerns of society. Although it is not a written contract with deliverables, there are reciprocal expectations and obligations on both sides. The concept of the social contract assists in introducing the obligations of a physician arising from the contract and provides a justification for their presence. In addition, as medicine and society change, the contract, as well as the professionalism which is linked to it, must evolve.

Developing professional identity

As experience in teaching professionalism has been gained, the realization has grown that the educational objective is to assist students as they develop a professional identity, a process that we are only beginning to understand. Identity can be defined as: “A set of characteristics or a description that distinguishes a person or thing from others” (Oxford Dictionary, 1989). Students enter medicine with an established identity and wish to acquire the identity of a physician. Professional identity formation is an evolving process that involves “a combination of experience and reflection on experience” (Hilton & Slotnick, 2005).

Professional identity develops through socialization which is”the process by which a person learns to function within a particular society or group by internalizing its values and norms” (Oxford Dictionary, 1989). Students must understand the identity they are to acquire and must be exposed to the experiences necessary for the formation of this identity (Hafferty, 2009). Finally, they require time to reflect on these experiences in a safe environment. Fundamental to the process is the presence of role models who demonstrate the behaviors characteristic of the healer and the professional in their daily lives. Finally, the learning environment must be supportive of the development of a professional identity. Teaching institutions are responsible for providing this environment, something that requires them to pay attention to the formal, the informal and the hidden curricula.

General principles

When an institution initiates a program of teaching professionalism, experience has shown that there are some general principles that are useful to follow (Cruess & Cruess, 2006).

Institutional Support

It is difficult to initiate a major teaching program without the support of the Dean’s office and of the Chairs of the major departments. As many bodies accrediting teaching and training programs now require professionalism to be taught and evaluated, administrative and financial support is becoming somewhat easier to obtain. Time must be mobilized in the curriculum, although experience has shown that the amount of additional time required is often not great. Most faculties already have activities taking place whose objective is to develop the professionalism of its students. These can frequently be reorganized into a coherent course to which can be added new learning experiences. In addition some administrative and financial support is almost always required.

Allocation of responsibility for the program

Someone must be responsible for the program and accountable for its performance. Ideally a respected member of the faculty is chosen to lead the design and implementation of the professionalism program and be its champion. In addition the program can benefit from the presence of an advisory committee with broad representation from the faculty. It must be remembered that professionalism crosses departmental lines and ideally exposure to it should come within the context of many departmental activities.

The definition, attributes, and behaviors serve as the basis for instruction at all levels – undergraduate, postgraduate, and practicing physician. Ideally they should inform the admission policies of the medical school, be used for teaching students, residents, and faculty, and for continuing professional development. The unifying theme is a common understanding of nature of professionalism. How it is taught and evaluated will vary depending upon the educational level. There is general agreement that “stage appropriate educational activities”, including assessment, should be devised and that they should represent an integrated entity throughout the continuum of medical education.

Incremental Approach

A comprehensive program for teaching professionalism is difficult to implement at all levels simultaneously. One should start with those activities devoted to the teaching of professionalism that are already in place. New programs often represent a combination of these activities and new learning experiences developed to complement what was previously taught. Once the objectives for the program on teaching professionalism have been developed, the program can be designed and introduced in incremental fashion.

The Cognitive Base

It is important to outline precisely what is to be taught. Thus, the cognitive base requires special attention. The definitions and attributes of the professional, which are to be the foundation of the teaching program, should be developed within the institution and general agreement on the educational approach to the subject obtained. Both the medical school and its teaching hospitals should participate in this process as all share the responsibility to understand and articulate what is expected of both students and faculty. The cognitive base must be taught explicitly and often, with increasing levels of sophistication appropriate to the student’s level of learning.

Experiential learning and Self-Reflection

The introduction of the cognitive base provides learners with both knowledge of the nature of professionalism and its value system. Medicine’s values must then be internalized so that they can serve as the foundation of a professional identity (Hafferty, 2009). There is wide consensus that students must experience situations in which these values become relevant or challenged as a necessary first step in the process of internalization. Learners must also have opportunities and time to reflect upon these experiences in a safe environment (Schon, 1987; Epstein, 1999). Teaching programs should ensure that students are exposed to the wide variety of experiences necessary to encompass knowledge of professionalism. The majority of these encounters will be true clinical situations, but in many instances they can be supplemented with reflection on experience from simulated clinical situations, small group discussions, clinical vignettes, role plays, film and video tape reviews, narratives, portfolios, social media, or directed reading (Cruess & Cruess, 2006).

The experiences used in teaching professionalism should be appropriate to the level of the student (Rudy, 2001). Reflection can be during the experience, on the experience, or after it has occurred, considering how action might differ in similar situations in the future.

Role Modeling

Role models must understand what aspects of professionalism they are modeling and be explicit about what they modeling (Cruess & Cruess, 2006; Wright et al., 1998; Kenny et al., 2003). Faculty development is often required to provide role-models with knowledge of the cognitive base of professionalism (Steinert et al., 2007). The role-modeling of faculty should be assessed and there must be positive or negative consequences to the evaluation (Cruess et al., 2008). Role-models should be supported and good role-models rewarded, poor ones remediated, and those who have demonstrated that they cannot be a good role model removed from teaching.

Both the cognitive base and the behaviors reflective of professional attributes must be evaluated, obviously using different methods. Knowledge can be tested in the traditional ways, including multiple choice questions, essays, short answers etc. It has become clear that professional attitudes and values cannot be reliably evaluated. It is therefore necessary to develop a series of observable behaviors which reflect the attitudes and values of the professional that can be evaluated (Stern, 2005; Hodges et al., 2011). It has also been recognized that only by carrying out multiple observations by multiple observers can reliable and valid results be obtained. Tools have been developed in order to accomplish this, and they should be used to evaluate students, residents, and faculty.

The evaluation of behaviors should be formative as this supports the learning process (Sullivan & Arnold, 2009). Summative evaluation must also be done on students and residents as it is the responsibility of the profession to protect the public from unprofessional practitioners. The professionalism of faculty members must also be assessed (Todhunter et al., 2011). It is a universal complaint of students that they are encouraged to behave professionally but frequently are exposed to unprofessional conduct on the part of their teachers (Brainard & Bilsen, 2007). Assessment of faculty performance offers a possible means of correcting this.

The Environment

The environment in which learning takes place can have a profound positive or negative impact on learning. There are three major components to this environment: the formal, the informal, and the hidden curricula (Hafferty & Franks, 1994; Hafferty, 1998). The formal curriculum consists of the official material contained in the mission statement of an institution and its course objectives. It outlines what the faculty believes they are teaching. The informal curriculum consists of unscripted, unplanned, and highly interpersonal forms of teaching and learning that takes place in classrooms, corridors, elevators - indeed any place where students and faculty have contact. It is here that role models exert their positive or negative influence. Finally, the hidden curriculum functions at the level of the organizational structure and culture of an institution. Allocation of time to certain activities, promotion policies and reward systems, that, for example, rewards research rather than teaching, can have a profound impact on the learning environment. This impact is felt disproportionately in the area of professionalism, which is so heavily dependent upon values. As a part of the establishment of any teaching program on professionalism, all elements of the curriculum must be addressed in order to ensure that they support professional values.

Faculty Development

Faculty development is fundamental to the establishment of a program of teaching professionalism (Steinert et al., 2007). It promotes institutional agreement on definitions and characteristics of professionalism. It allows the faculty to develop methods of teaching and evaluation and, properly used can lead to substantial changes in the curriculum. Most importantly, it helps to ensure the presence of skilled teachers, group leaders, and hopefully role models.

The McGill Experience

In 1997 McGill instituted the teaching of professionalism and over the next six years, in an incremental fashion, developed a four year program on Physicianship (Cruess & Cruess, 2006; Boudreau et al., 2011; Boudreau et al., 2007). The concept includes the separate but overlapping roles of physicians as healers and as professionals. Through a series of faculty development workshops the faculty agreed upon the definitions to be used and the attributes to be taught and evaluated (Steinert et al., 2007). These became the basis for 1. the selection of students 2. the content of teaching and 3. of the evaluation of students, residents, and faculty.

Student selection

McGill changed its student selection process to one utilizing the multiple mini interview process (MMI) (Razack et al., 2009). The mini-interviews take place in a simulation center using actors. There are 10 stations, with each station designed to demonstrate the presence in the applicant of the behaviors found in a model physician. The purpose is to identify those candidates who already demonstrate the attributes of the healer and the professional and, importantly, to publicly indicate the importance of these attributes. For those students who are granted an interview, the MMI score contributes 70% of the candidate’s final ranking on the admission scale. Unpublished data indicates that the MMI scores correlate with clinical performance during medical school.

There are three major aspects to the undergraduate program; whole class activities on both the healer and the professional; unit specific activities in various departments; and a mentorship program. The faculty first identified those components that were already being taught (ethics, professionalism, narrative medicine, end-of-life care) and added the others as they were developed.

Whole class activities

In the undergraduate curriculum, a longitudinal course on Physicianship that the students are required to pass was developed and implemented (Cruess & Cruess, 2006; Boudreau et al., 2007; Boudreau et al., 2011). It contained two separate but overlapping blocks on the healer and the professional.

Whole class activities include lectures on the nature of professionalism. Of symbolic significance, the first lecture on the first day of class is a didactic session on professionalism which presents the definitions and vocabulary which will be used. This is followed by small group sessions with trained faculty that examines vignettes demonstrating good and poor professional behavior. The objective is to identify the attributes present in each, familiarizing students with the vocabulary and the use of the concept. Ethics lectures are given and are always followed by small group discussions. Communication skills are taught using the Calgary-Cambridge format (Kurtz & Silverman, 1996). The subjects covered in the bloc on the Healer are physician wellness, the perspective of both the doctor and patient in the doctor-patient relationship, working with members of the health care team, and analyzing the nature of suffering. Great emphasis is placed upon reviewing narratives of the experiences of both patients and physicians. Other whole class activities include the introduction to the cadaver as the student’s first patient as well as a body donor service developed by students to show appreciation for the donors of the bodies. There is a white coat ceremony given prior to entry into the clinical years. Palliative care is felt to emphasize the healer role and there are special reflective experiences in this domain with mentors. In the last year students attend seminars with the goal of uniting the healer and professionalism roles. Students are given a fuller exposure to the concept of medicine’s social contract with society and encouraged to reflect on which of the public expectations of the profession they will find difficult to fulfill and how they might overcome these difficulties. These discussions are guided by their mentors (Osler Fellows) who have been with them for all four years.

Unit specific activities

Each department is encouraged to develop unit specific activities on the roles of the healer and the professional. Departmental rounds are devoted to the subject, bedside discussions of conflicts in professionalism take place, and the professionalism of students is assessed on ongoing basis. Of necessity, there is less structure to unit-specific activities than is present in whole class activities, but they are of extreme importance in providing experiences upon which students reflect with their mentors.

Osler Fellows

A mentorship program was established with the mentors being given the title of “Osler Fellows”. They were selected from a list of nominations by students and faculty of those recognized as being outstanding teachers, practitioners and role models. Each Osler Fellow mentors six students throughout their medical school career. They are an important part of the teaching of professionalism as they have a series of mandated activities which must be carried out. A portfolio is instituted, with an emphasis on professionalism, and narratives are produced and reviewed. There are of course a host of unscheduled encounters during which the student and mentor establish a relationship. The Osler Fellows have a dedicated faculty development program to familiarize them with their roles (Steinert et al., 2010).

Postgraduate education

During postgraduate training, residents have several half day recall sessions each year (Snell, 2009). At one of these there is a review of the cognitive base of professionalism as many residents are from diverse backgrounds. It is important to provide a common vocabulary for use in training and practice. The review is followed by small group sessions including residents from different specialties who discuss their experiences of professionalism during residency with an emphasis on how they will meet their responsibilities to society. Residents are involved as group leaders for the undergraduate sessions, participate in the assessment of the professionalism of students and faculty, and sessions are held to assist them in understanding their roles as teachers and role-models. The subjects covered in other half-day sessions that relate to professionalism are ethics, malpractice, risk management, teamwork, communication skills, and their own wellness.

Teaching professionalism requires that each teaching community agree on the cognitive base - a definition of profession, the attributes of the professional, and the relationship of medicine to the society which it serves. These should be taught explicitly. The program should extend throughout the continuum of medical education and passing should be obligatory for progression to the next level. The substance of professionalism must become part of each physician’s identity and be reflected in observable behaviors. Professionalism should be taught as “an Ideal to be pursued” rather than as a set of rules and regulations (Cruess et al., 2000).

- Boudreau JD, Cassell EJ, Fuks A. A healing curriculum. Med Ed. 2007; 41 :1193–1201. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boudreau DJ, Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Physicianship- educating for professionalism in the post- Flexnerian era. Perspectives in Biol & Med. 2011; 54 :89–105. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brainard AH, Bilsen HC. Learning professionalism: a view from the trenches. Acad Med. 2007; 82 :1010–1014. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brennan T. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician’s charter. Ann. Int. Med. 2002; 136 :243–246. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen JJ. Professionalism in medical education, an American perspective: from evidence to accountability. Med Educ. 2006; 40 :607–617. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Coulehan J. Today’s professionalism: engaging the mind but not the heart. Acad Med. 2005; 80 :892–898. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Teaching medicine as a profession in the service of healing. Acad Med. 1997; 72 :941–952. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Teaching Professionalism: general principles. Medical Teacher. 2006; 28 :205–208. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Expectations and obligations: professionalism and medicine’s social contract with society. Perspect Biol Med. 2008; 51 :579–598. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Johnston SE. Professionalism – an ideal to be pursued. Lancet. 2000; 365 :156–159. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Cruess R.L., Cruess S.R., and Steinert Y (eds) “Teaching Medical Professionalism”. Cambridge Univ Press; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism must be taught. BMJ. 1997; 315 :1674–1677. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Role modeling: making the most of a powerful teaching strategy. BMJ. 2008; 336 :718–721. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cruess SR, Johnston S, Cruess RL. Professionalism: a working definition for medical educators. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 2004; 16 :74–76. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999; 282 :833–839. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998; 73 :403–407. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hafferty FW. Cruess R.L., Cruess S.R., and Steinert Y (eds) “Teaching Medical Professionalism”. Cambridge Univ Press; 2009. Professionalism and the socialization of medical students; pp. 53–73. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994; 69 :861–871. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hafferty FW, McKinley JB. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1993. The Changing Medical Profession: an International Perspective. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hilton SR, Slotnick HB. Proto-professionalism: how professionalization occurs across the continuum of medical education. Med Ed. 2005; 39 :58–65. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hodges BD, Ginsburg S, Cruess R, et al. Assessment of professionalism: Recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 Conference. Med Teach. 2011; 33 :354–363. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huddle TS. Teaching professionalism: is medical morality a competency? Acad Med. 2005; 80 :885–891. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kenny NP, Mann KV, MacLeod HM. Role modeling in physician’s professional formation: reconsidering an essential but untapped educational strategy. Acad Med. 2003; 78 :1203–1210. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Klein R. The New Politics of the National Health Service. 5th ed. Oxford: Radcliffe Pub; 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Krause E. Death of the Guilds: Professions, States and the Advance of Capitalism, 1930 to the Present. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kurtz SM, Silverman JD. The Calgary-Cambridge reference observation guide: an aid to defining the curriculum and organizing the teaching in communication training programs. Med Ed. 1996; 30 :83–89. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ludmerer KM. Instilling professionalism in medical education. JAMA. 1999; 282 :881–882. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Oxford, U.K.: Clarendon Press; 1989. [ Google Scholar ]

- Razack S, Faremo S, Drolet F, et al. Multiple mini-interviews versus traditional interviews: stakeholder acceptability comparison. Med Educ. 2009; 43 :993–1000. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Royal College of Physicians of London. Doctors in society: medical professionalism in a changing world. London UK: Royal college of Physicians of London; 2005. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rudy DW, Elam CL, Griffith CH. Developing a stage-appropriate professionalism curriculum. Acad Med. 2001; 76 :503. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schon DA. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Towards a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [ Google Scholar ]

- Snell L. Cruess R.L., Cruess S.R., and Steinert Y (eds) “Teaching Medical Professionalism”. Cambridge Univ Press; 2009. Teaching professionalism and fostering professional values during residency: the McGill experience; pp. 246–263. [ Google Scholar ]

- Starr P. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books; 1984. [ Google Scholar ]

- Steinert Y, Boudreau D, Boillat M, et al. The Osler fellowship: an apprenticeship for medical educators. Acad Med. 2010; 85 :1242–1249. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steinert Y, Cruess RL, Cruess SR, et al. Faculty development as an instrument of change: a case study on teaching professionalism. Acad Med. 2007; 82 :1057–1064. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stern DT. Measuring Medical Professionalism. New York NY: Oxford Univ Press; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sullivan WM. Cruess R.L., Cruess S.R., and Steinert Y (eds) “Teaching Medical Professionalism”. Cambridge Univ Press; 2009. Introduction; pp. 1–7. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sullivan C, Arnold L. Cruess R.L., Cruess S.R., and Steinert Y (eds) “Teaching Medical Professionalism”. Cambridge Univ Press; 2009. Assessment and remediation in programs of teaching professionalism; pp. 124–150. [ Google Scholar ]

- Swick HM. Towards a normative definition of professionalism. Acad Med. 2000; 75 :612–616. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Todhunter S, Cruess RL, et al. Developing and piloting a form for student assessment of faculty professionalism. Advanc Health Sci Edu. 2011; 16 :223–238. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wright SM, Kern D, Kolodner K, et al. Attributes of excellent attending-physician role models. NEJM. 1998; 339 :1986–1993. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Corpus ID: 68404138

Teacher Professionalism Defined and Enacted: A Comparative Case Study of Two Subject Teaching Associations

- Fiona Hilferty

- Published 17 July 2008

7 Citations

Contextualizing teacher professionalism: findings from a cross-case analysis of union active teachers.

- Highly Influenced

- 11 Excerpts

SUPPORTING DEMOCRATIC DISCOURSES OF TEACHER PROFESSIONALISM: THE CASE OF THE ALBERTA TEACHERS' ASSOCIATION

The mediating effect of time management on the relationship between work ethics and professionalism among public school teachers, discourses of teacher professionalism: “from within” and “from without” or two sides of the same coin, primary school teachers' understanding of themselves as professionals, theorising teacher professionalism as an enacted discourse of power, contesting the curriculum: an examination of professionalism as defined and enacted by australian history teachers, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Faculty Development as an Instrument of Change: A Case Study on Teaching Professionalism

Steinert, Yvonne PhD; Cruess, Richard L. MD; Cruess, Sylvia R. MD; Boudreau, J Donald MD; Fuks, Abraham MD

Dr. Steinert is professor, Family Medicine, associate dean, Faculty Development, and director, Centre for Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Dr. Richard Cruess is professor, Surgery, and core faculty, Centre for Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Dr. Sylvia Cruess is professor, Medicine, and core faculty, Centre for Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Dr. Boudreau is associate professor, Medicine, director, Office of Curriculum Development, and core faculty, Centre for Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Dr. Fuks is professor, Medicine, and former dean, Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Steinert, Associate Dean and Director, Centre for Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, Lady Meredith House, McGill University, 1110 Pine Ave. W., Montreal, Quebec, H3A 1A3 Canada; telephone: (514) 398-2698; fax: (514) 398-6649; e-mail: ( [email protected] ).

Faculty development includes those activities that are designed to renew or assist faculty in their different roles. As such, it encompasses a wide variety of interventions to help individual faculty members improve their skills. However, it can also be used as a tool to engage faculty in the process of institutional change. The Faculty of Medicine at McGill University determined that such a change was necessary to effectively teach and evaluate professionalism at the undergraduate level, and a faculty development program on professionalism helped to bring about the desired curricular change. The authors describe that program to illustrate how faculty development can serve as a useful instrument in the process of change.

The ongoing program, established in 1997, consists of medical education rounds and “think tanks” to promote faculty consensus and buy-in, and diverse faculty-wide and departmental workshops to convey core content, examine teaching and evaluation strategies, and promote reflection and self-awareness. To analyze the approach used and the results achieved, the authors applied a well-known model by J.P. Kotter for implementing change that consists of the following phases: establishing a sense of urgency, forming a powerful guiding coalition, creating a vision, communicating the vision, empowering others to act on the vision, generating short-term wins, consolidating gains and producing more change, and anchoring new approaches in the culture. The authors hope that their school’s experience will be useful to others who seek institutional change via faculty development.

Full Text Access for Subscribers:

Individual subscribers.

Institutional Users

Not a subscriber.

You can read the full text of this article if you:

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Silent witnesses: faculty reluctance to report medical students’..., a schematic representation of the professional identity formation and..., medical education in the united states and canada, 2010, an interdisciplinary community diagnosis experience in an undergraduate medical ....

ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining its efforts to eradicate extreme poverty.

Established in 1966, it is owned by 68 members—49 from the region..

- Annual Reports

- Policies and Strategies

ORGANIZATION

- Board of Governors

- Board of Directors

- Departments and Country Offices

ACCOUNTABILITY

- Access to Information

- Accountability Mechanism

- ADB and Civil Society

- Anticorruption and Integrity

- Development Effectiveness

- Independent Evaluation

- Administrative Tribunal

- Ethics and Conduct

- Ombudsperson

Strategy 2030: Operational Priorities

Annual meetings, adb supports projects in developing member countries that create economic and development impact, delivered through both public and private sector operations, advisory services, and knowledge support..

ABOUT ADB PROJECTS

- Projects & Tenders

- Project Results and Case Studies

PRODUCTS AND SERVICES

- Public Sector Financing

- Private Sector Financing

- Financing Partnerships

- Funds and Resources

- Economic Forecasts

- Publications and Documents

- Data and Statistics

- Asia Pacific Tax Hub

- Development Asia

- ADB Data Library

- Agriculture and Food Security

- Climate Change

- Digital Technology

- Environment

- Finance Sector

- Fragility and Vulnerability

- Gender Equality

- Markets Development and Public-Private Partnerships

- Regional Cooperation

- Social Development

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Urban Development

REGIONAL OFFICES

- European Representative Office

- Japanese Representative Office | 日本語

- North America Representative Office

LIAISON OFFICES

- Pacific Liaison and Coordination Office

- Pacific Subregional Office

- Singapore Office

SUBREGIONAL PROGRAMS

- Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area (BIMP-EAGA)

- Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) Program

- Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Program

- Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand Growth Triangle (IMT-GT)

- South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation (SASEC)

With employees from more than 60 countries, ADB is a place of real diversity.

Work with us to find fulfillment in sharing your knowledge and skills, and be a part of our vision in achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable asia and the pacific., careers and scholarships.

- What We Look For

- Career Opportunities

- Young Professionals Program

- Visiting Fellow Program

- Internship Program

- Scholarship Program

FOR INVESTORS

- Investor Relations | 日本語

- ADB Green and Blue Bonds

- ADB Theme Bonds

INFORMATION ON WORKING WITH ADB FOR...

- Consultants

- Contractors and Suppliers

- Governments

- Executing and Implementing Agencies

- Development Institutions

- Private Sector Partners

- Civil Society/Non-government Organizations

PROCUREMENT AND OUTREACH

- Operational Procurement

- Institutional Procurement

- Business Opportunities Outreach

Teacher Professional Development Case Studies: K-12, TVET, and Tertiary Education

Share this page.

This publication discusses how to create sustainable and high quality teacher capacity development systems for primary and secondary education, technical and vocational education and training, and higher education.

Download (Free : 2 available)

- PDF File (6.69 MB)

- ePub for Mobile (4.02 MB)

- US$34.00 (paperback)

- http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/SPR210293

Quality teaching is vital to meet the increasingly complex needs of students as they prepare for further education and work in the 21st century. The publication showcases 14 case studies from around the world as examples of teacher professional development programs that support, improve, and harness teaching capabilities and expertise. It also discusses government initiatives and other factors that can contribute to quality teaching.

- Executive Summary

- Principles of Teacher Professional Development

- Cases in K−12

- Cases in Technical and Vocational Education and Training

- Cases in Higher Education

- Recommendations

Additional Details

| Authors | |

| Type | |

| Subjects | |

| Pages | |

| Dimensions | |

| SKU | |

| ISBN |

- 50361-001: Innovation in Education Sector Development in Asia and the Pacific

- ADB's focus on education

- ADB funds and products

- Agriculture and natural resources

- Capacity development

- Climate change

- Finance sector development

- Gender equality

- Governance and public sector management

- Industry and trade

- Information and Communications Technology

- Private sector development

- Regional cooperation and integration

- Social development and protection

- Urban development

- Central and West Asia

- Southeast Asia

- The Pacific

- China, People's Republic of

- Lao People's Democratic Republic

- Micronesia, Federated States of

- Learning materials Guidelines, toolkits, and other "how-to" development resources

- Books Substantial publications assigned ISBNs

- Papers and Briefs ADB-researched working papers

- Conference Proceedings Papers or presentations at ADB and development events

- Policies, Strategies, and Plans Rules and strategies for ADB operations

- Board Documents Documents produced by, or submitted to, the ADB Board of Directors

- Financing Documents Describes funds and financing arrangements

- Reports Highlights of ADB's sector or thematic work

- Serials Magazines and journals exploring development issues

- Brochures and Flyers Brief topical policy issues, Country Fact sheets and statistics

- Statutory Reports and Official Records ADB records and annual reports

- Country Planning Documents Describes country operations or strategies in ADB members

- Contracts and Agreements Memoranda between ADB and other organizations

Subscribe to our monthly digest of latest ADB publications.

Follow adb publications on social media..

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Faculty development as an instrument of change: a case study on teaching professionalism

Affiliation.

- 1 Centre for Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. [email protected]

- PMID: 17971692

- DOI: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000285346.87708.67

Faculty development includes those activities that are designed to renew or assist faculty in their different roles. As such, it encompasses a wide variety of interventions to help individual faculty members improve their skills. However, it can also be used as a tool to engage faculty in the process of institutional change. The Faculty of Medicine at McGill University determined that such a change was necessary to effectively teach and evaluate professionalism at the undergraduate level, and a faculty development program on professionalism helped to bring about the desired curricular change. The authors describe that program to illustrate how faculty development can serve as a useful instrument in the process of change. The ongoing program, established in 1997, consists of medical education rounds and "think tanks" to promote faculty consensus and buy-in, and diverse faculty-wide and departmental workshops to convey core content, examine teaching and evaluation strategies, and promote reflection and self-awareness. To analyze the approach used and the results achieved, the authors applied a well-known model by J.P. Kotter for implementing change that consists of the following phases: establishing a sense of urgency, forming a powerful guiding coalition, creating a vision, communicating the vision, empowering others to act on the vision, generating short-term wins, consolidating gains and producing more change, and anchoring new approaches in the culture. The authors hope that their school's experience will be useful to others who seek institutional change via faculty development.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Promoting an environment of professionalism: the University of Chicago "Roadmap". Humphrey HJ, Smith K, Reddy S, Scott D, Madara JL, Arora VM. Humphrey HJ, et al. Acad Med. 2007 Nov;82(11):1098-107. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000285344.10311.a8. Acad Med. 2007. PMID: 17971700

- From traditional to patient-centered learning: curriculum change as an intervention for changing institutional culture and promoting professionalism in undergraduate medical education. Christianson CE, McBride RB, Vari RC, Olson L, Wilson HD. Christianson CE, et al. Acad Med. 2007 Nov;82(11):1079-88. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181574a62. Acad Med. 2007. PMID: 17971696

- Faculty development for teaching and evaluating professionalism: from programme design to curriculum change. Steinert Y, Cruess S, Cruess R, Snell L. Steinert Y, et al. Med Educ. 2005 Feb;39(2):127-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02069.x. Med Educ. 2005. PMID: 15679679

- Professionalism in medical education: an institutional challenge. Goldstein EA, Maestas RR, Fryer-Edwards K, Wenrich MD, Oelschlager AM, Baernstein A, Kimball HR. Goldstein EA, et al. Acad Med. 2006 Oct;81(10):871-6. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000238199.37217.68. Acad Med. 2006. PMID: 16985343 Review.

- Leadership lessons from curricular change at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine. Loeser H, O'Sullivan P, Irby DM. Loeser H, et al. Acad Med. 2007 Apr;82(4):324-30. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803337de. Acad Med. 2007. PMID: 17414186 Review.

- Impact of group work on the hidden curriculum that induces students' unprofessional behavior toward faculty. Nakamura A, Kasai H, Asahina M, Kamata Y, Shikino K, Shimizu I, Onodera M, Kimura Y, Tajima H, Yamauchi K, Ito S. Nakamura A, et al. BMC Med Educ. 2024 Jul 19;24(1):770. doi: 10.1186/s12909-024-05713-7. BMC Med Educ. 2024. PMID: 39030519 Free PMC article.

- Successful instillation of professionalism in our future doctors. Wargent E, Stocker C. Wargent E, et al. MedEdPublish (2016). 2021 Jun 14;10:173. doi: 10.15694/mep.2021.000173.1. eCollection 2021. MedEdPublish (2016). 2021. PMID: 38486594 Free PMC article.

- School climate's effect on hospitality department students' aesthetic experience, professional identity and innovative behavior. Lin W, Chang YC. Lin W, et al. Front Psychol. 2022 Dec 5;13:1059572. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1059572. eCollection 2022. Front Psychol. 2022. PMID: 36544448 Free PMC article.

- Teaching and Learning Medical Professionalism: an Input from Experienced Faculty and Young Graduates in a Tertiary Care Institute. Panda S, DAS A, DAS R, Shullai WK, Sharma N, Sarma A. Panda S, et al. Maedica (Bucur). 2022 Jun;17(2):371-379. doi: 10.26574/maedica.2022.17.2.371. Maedica (Bucur). 2022. PMID: 36032628 Free PMC article.

- Knowledge of and attitudes toward the WHO MPOWER policies to reduce tobacco use at the population level: a comparison between third-year and sixth-year medical students. Martins SR, Szklo AS, Bussacos MA, Prado GF, Paceli RB, Fernandes FLA, Lombardi EMS, Basso RG, Terra-Filho M, Santos UP. Martins SR, et al. J Bras Pneumol. 2021 Jan 8;47(1):e20190402. doi: 10.36416/1806-3756/e20190402. eCollection 2021. J Bras Pneumol. 2021. PMID: 33439961 Free PMC article.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Wolters Kluwer

Research Materials

- NCI CPTC Antibody Characterization Program

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

The Role of Professional Knowledge in Case-Based Reasoning in Practical Ethics

- Original Paper

- Published: 29 March 2015

- Volume 21 , pages 767–787, ( 2015 )

Cite this article

- Rosa Lynn Pinkus 1 ,

- Claire Gloeckner 2 &

- Angela Fortunato 3

665 Accesses

7 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

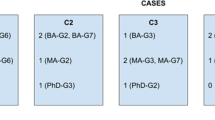

The use of case-based reasoning in teaching professional ethics has come of age. The fields of medicine, engineering, and business all have incorporated ethics case studies into leading textbooks and journal articles, as well as undergraduate and graduate professional ethics courses. The most recent guidelines from the National Institutes of Health recognize case studies and face-to-face discussion as best practices to be included in training programs for the Responsible Conduct of Research. While there is a general consensus that case studies play a central role in the teaching of professional ethics, there is still much to be learned regarding how professionals learn ethics using case-based reasoning. Cases take many forms, and there are a variety of ways to write them and use them in teaching. This paper reports the results of a study designed to investigate one of the issues in teaching case-based ethics: the role of one’s professional knowledge in learning methods of moral reasoning. Using a novel assessment instrument, we compared case studies written and analyzed by three groups of students whom we classified as: (1) Experts in a research domain in bioengineering. (2) Novices in a research domain in bioengineering. (3) The non - research group —students using an engineering domain in which they were interested but had no in-depth knowledge. This study demonstrates that a student’s level of understanding of a professional knowledge domain plays a significant role in learning moral reasoning skills.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price excludes VAT (USA) Tax calculation will be finalised during checkout.

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Validity and reliability of an instrument for assessing case analyses in bioengineering ethics education.

Ethics education in the professions: an unorthodox approach

Collaborative case-based learning process in research ethics

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Medical Ethics

The paper can be obtained by contacting the author Mark Kuczewski directly at <[email protected]>.

This case, “The Price is Right,” is a modified version of a case with the same name found in the text by Harris et al. ( 2009 , p. 335). Technical issues related to bioengineering were added to that generic engineering ethics case.

This was a preliminary study to the one reported here, which is discussed in detail below.

“Learning and Intelligent Systems: Modeling Learning to Reason with Cases in Engineering Ethics: A Test Domain for Intelligent Assistance,” 1997, National Science Foundation award # 9720341.

Scaffolded Writing and Rewriting in the Discipline ( https://sites.google.com/site/swordlrdc/directory , accessed January 29, 2015).

That work was performed under NSF award # 9720341, " Learning and Intelligent Systems: Modeling Learning to Reason with Cases in Engineering Ethics: A Test Domain for Intelligent Assistance", 1997.

The GRE “is a standardized exam used to measure one’s aptitude for abstract thinking in the areas of analytical writing, mathematics and vocabulary” ( www.investopedia.com/terms/g/gre.asp ). Many graduate schools in the US use these scores to determine an applicant’s eligibility for a given graduate program.

Arras, J. D. (1991). Getting down to cases: The revival of casuistry in bioethics. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 16 (1), 29–51.

Article Google Scholar

Arras, J., & Rhoden, N. (1989). Ethical issues in modern medicine . Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company.

Google Scholar

Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2001). Principles of biomedical ethics . New York: Oxford University Press.

Brody, B. A. (1988). Life and death decision-making . New York: Oxford University Press.

Brody, B. A. (2003). Taking issue: Pluralism and casuistry in bioethics . Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Caplan, A. L. (1980). Ethical engineers need not apply: The state of applied ethics today. Science Technology & Human Value, 5 (4), 24–32.

Chambers, T. S. (1995). No Nazis, no space aliens, no slippery slopes and other rules of thumb for clinical ethics. Journal of Medical Humanities, 16 (3), 189–200.

Chi, M. T. H. (1978). Knowledge structures and memory development. In R. S. Siegler (Ed.), Children’s thinking: What develops? (pp. 73–96). Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum.

Chi, M. T., & Koeske, R. D. (1983). Network representation of a child’s dinosaur knowledge. Developmental Psychology, 19 (1), 29–39.

Churchill, L. (1992). Theories of justice. In C. Kjellstrand & J. B. Dossetor (Eds.), Ethical problems in dialysis and transplantation (pp. 21–31). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Chapter Google Scholar

Fisher, F. T., & Peterson, P. L. (2001). A tool to measure adaptive expertise in biomedical engineering students. Multimedia Division (Session 2793) In Proceedings for the 2001 ASEE annual conference , June 24 – 27 , Albuquerque, NM.

Goldin, I., Pinkus, R. L., & Ashley, K. D. (2015). Validity and reliability of an instrument for assessing case analysis in bioengineering ethics education. Science and Engineering Ethics, . doi: 10.1007/s11948-015-9644-2 .

Han, R.-X., Foreman, M., Gollogly, A., Sivarajan, L., & Talman, L. (2007). Interview with Renée C. Fox, Ph.D.: 2007 Lifetime achievement award, American Society for Bioethics and Humanities. Penn Bioethics Journal Vol IV, Issue Fall 2007.

Harris, C. E., Pritchard, M. S., & Rabins, M. J. (2009). Engineering ethics: Concepts and cases . (4th ed.) Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

Jonsen, A. R. (1991). Of balloons and bicycles or the relationship between ethical theory and practical judgment. The Hastings Cent Report, 5 (21), 14–16.

Jonsen, A. R., & Toulmin, S. (1988). The abuse of casuistry: A history of moral reasoning . Berkley: University of California Press.

Keefer, M., & Ashley, K. D. (2001). Case-based approaches to professional ethics: A systematic comparison of students’ and ethicists’ moral reasoning. Journal of Moral Education, 30 (4), 377–398.

Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal. (2007). Call for papers: The method of bioethics. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal., 17 (3), 277–278.

Kuczewski, M. (2004). Methods of bioethics: The four principles approach, casuistry, communitarianism . http://bioethics.lumc.edu/about/people/Kuczewski . Accessed December 8, 2009.

Macklin, R. (1993). Teaching bioethics to future healthcare professionals: A case-based clinical model. Bioethics, 7 (2–3), 200–206.

Martin, T., Rayne, K., Kemp, N. J., Hart, J., & Diller, K. R. (2005). Teaching for adaptive expertise in biomedical engineering ethics. Science and Engineering Ethics, 11 (2), 257–276.

National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2009). Update on the requirement for instruction in the responsible conduct of research . www.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-10-019.html . Accessed January 29, 2015.

National Society of Professional Engineers. (2007). Code of ethics for engineers . http://www.nspe.org/sites/default/files/resources/pdfs/Ethics/CodeofEthics/Code-2007-July.pdf . Accessed January 29, 2015.

Pinkus, R. L., & Gloecker, C. (1999). Want to help students learn engineering ethics? Have them write case studies based on their research/senior design project , Online Ethics Center for Engineering 6/20/2006 National Academy of Engineering. www.onlineethics.org/Education/instructguides/pinkus.aspx . Accessed January 17, 2015.

Pinkus, R. L., Shuman, L. J., Hummon, N. P., & Wolf, H. (1997). Engineering ethics: Balancing cost, risk and schedule: Lessons learned from the space shuttle . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Whitbeck, C. (1995). Teaching ethics to scientists and engineers: Moral agents and moral problems. Science and Engineering Ethics, 1 (3), 299–308.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The first author would like to acknowledge Kevin Ashley and Ilya Goldin for comments on previous drafts of this paper; Micki Chi for her comprehensive body of work in cognitive psychology that led to the development of the MMR; Michel Ferrari and Judith McQuaide for their contributions to the cognitive modeling grant that is quoted in this paper; Rebecca A. Pinkus and Connor Burn for providing a template of a marking grid that ultimately was developed into our assessment instrument; and Stephanie Bird, who served as a supportive and patient mentor to the first author as this paper and the paper by Ilya Goldin and colleagues ( 2015 ) moved from conception to completion. Ann Mertz provided valuable editing for the final version of the paper. Sarah Sudar and Jody Stockdill provided invaluable technical assistance with the completion of this paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Bioengineering, 302 Benedum Hall, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, 15060, USA

Rosa Lynn Pinkus

CR Bard, Bard Medical Division, 8195 Industrial Blvd NE., Covington, GA, 30014, USA

Claire Gloeckner

Oakcrest School, 850 Balls Hill Rd., Mclean, VA, 22101, USA

Angela Fortunato

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rosa Lynn Pinkus .

Appendix: Coding Instructions and Coding Sheet for Student Paper Analysis

Coding instructions.

In order to achieve the most accurate and consistent classification of respondents’ papers, the same method must be used to code each paper. When reviewing the papers, all coders should follow the instructions below. They will take coders through the assessment form in the order it was meant to be used.

Fill in the classification information at the top of the assessment form according to the attached cover letter.

Analytical Components of Methods of Moral Reasoning

While reading the paper, look for these concepts. Write in the page numbers on the appropriate line next to the concept, noting if the respondent has done one or more of the following: labeled (L), defined (D), or applied (A) the concept. Examples:

Label: “Jake was concerned the patient had not given full informed consent.”

Define: “A patient gives informed consent if he or she gives permission for a procedure, being fully and completely aware of all it entails and of all consequences. The consent must be freely given and not coerced.”

Apply correctly: “After she discussed the procedure with her doctor and had her questions answered, Emily freely agreed to have the operation done.”

The attached glossary provides definitions and examples of all the concepts. Use it as a guide in coding. It should be particularly useful in the following two cases: (1) respondents may apply a concept without explicitly labeling it (as shown in the above example) or (2) if you find that there is a serious error in the respondent’s definition or application of the concept. In the latter case, please make a note in the margin. For example: “L, D, informed consent. Incorrect D: the student discusses informing the patient, but does not discuss the meaning of consent.”

If the paper contains a concept not on the list, then add it to the open spaces on the concept checklist.

Higher Order Criteria (Bottom of the Assessment Form)

The criteria listed here capture more abstract aspects of the ethical analysis. Use of these criteria can be indicated with a simple yes or no, but the coder should also provide a brief justification and page number(s) of when the criterion was used.

Professional knowledge means that the case is set in the context of well articulated and relevant technical knowledge.

Identify different perspectives means that the respondent has analyzed the case from different points of view.

Moving flexibly among various perspectives suggests that the person has a deep knowledge of the different perspectives and can use these different domains as they analyze the case. A paper exhibits this by not only analyzing the case from the viewpoints of various case participants but also by explaining how these viewpoints and analyses relate to one another and to the overall ethical analysis.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Pinkus, R.L., Gloeckner, C. & Fortunato, A. The Role of Professional Knowledge in Case-Based Reasoning in Practical Ethics. Sci Eng Ethics 21 , 767–787 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9645-1

Download citation

Received : 29 May 2008

Accepted : 07 January 2015

Published : 29 March 2015

Issue Date : June 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9645-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cognitive science

- Case-based reasoning

- Practical ethics

- Bioengineering

- Expert knowledge

- Professional knowledge

- Responsible conduct of research

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

English Education Journal

2302-6413 (Print)

2716-3687 (Online)

- Other Journals

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Empowering Teachers for Effective Online English Language Instruction: A Case Study of Prezi Video Implementation

Clark, R. E. (2001). Learning from media. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishers. Clark, R.E and Morrison, G.R. (2019). Media and learning: Definition and summary of research, do media influence the cost and access to instruction. Education Encyclopedia State University.com. Accessed from https://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2211/Media-Learning.html on January 31, 2020

Green, J.K., Burrow, M.S. & Carvalho, L. (2020). “Designing for transition: Supporting teachers and students cope with emergency remote education. Postdigit Sci Educ 2, 906–922 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00185-6 Mayer, R. (1997). “Multimedia learning: Are we asking the right questions?” Edycational Psychologist 32(1): 1-19

Morrison, D. (n.d.). How to Develop a Sense of Presence in Online and F2F Courses with Social Media. online learning insights. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from http://onlinelearninginsights.wordpress.com/2014/09/29/how-to-develop-a-sense- of-presence-in-online-and-f2f-courses-with-social-media/

Mousavi, S. Y.; Low, R; and Sweller, J. (1995). "Reducing Cognitive Load by Mixing Auditory and Visual Presentation Modes." Journal of Educational Psychology 87:319–334.

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Preisman, K. A. (2014). “Teaching presence in online education: from the instructor’s point of view”. Online Learning, 10(3), 1–16.

UNT Commons. (2020). “The importance of instructor presence in online learning.” Retrieved on October 25, 2020 from https://teachingcommons.unt.edu/teaching-essentials/online-teaching/importance -instructor-presence-online-learning

Wenger, E. (2000). Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization. 7(2), pp.225-24.

- There are currently no refbacks.

Jalan Ir. Sutami 36 A, Surakarta, 57126

(0271) 638959

Pan-African Journal of Business Management Journal / Pan-African Journal of Business Management / Vol. 8 No. 1 (2024) / Articles (function() { function async_load(){ var s = document.createElement('script'); s.type = 'text/javascript'; s.async = true; var theUrl = 'https://www.journalquality.info/journalquality/ratings/2408-www-ajol-info-pajbm'; s.src = theUrl + ( theUrl.indexOf("?") >= 0 ? "&" : "?") + 'ref=' + encodeURIComponent(window.location.href); var embedder = document.getElementById('jpps-embedder-ajol-pajbm'); embedder.parentNode.insertBefore(s, embedder); } if (window.attachEvent) window.attachEvent('onload', async_load); else window.addEventListener('load', async_load, false); })();

Article sidebar.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Main Article Content

College managerial practices for promoting english language teaching and learning in tanzania: a case study of grade ‘a’ public teachers’ training colleges, deogratius mathew wenga, winfrida saimon malingumu.

This study examined the college management practices for promoting English language teaching and learning in public teachers’ colleges using a case of Grade ‘A’ central zone training institutions. The objective of the study was to identify college management practices for promoting English language teaching and learning. The qualitative study employed a case study design, and interviews and focus group discussions to generate data from 20 conveniently and purposively sampled respondents comprising English language teachers, academic deans, principals and students. The study found out that teachers’ training colleges used performance rewards, close monitoring and evaluation of teachers, debating and other English clubs, staff professional development, and providing supportive teaching and learning environment to enhance English language teaching and learning. Additionally, the teachers’ college management need regular monitoring to ensure that English language promotion plans it was are properly executed instead of remaining only good on paper.

AJOL is a Non Profit Organisation that cannot function without donations. AJOL and the millions of African and international researchers who rely on our free services are deeply grateful for your contribution. AJOL is annually audited and was also independently assessed in 2019 by E&Y.

Your donation is guaranteed to directly contribute to Africans sharing their research output with a global readership.

- For annual AJOL Supporter contributions, please view our Supporters page.

Journal Identifiers

These languages are provided via eTranslation, the European Commission's machine translation service.

- slovenščina

- Azerbaijani

Cultural Heritage Education: Saint James Way as a case study

Join "Exploring the Way of St. James in Education," a course in Porto and the North of Portugal, focused on integrating the Camino de Santiago as a cultural product in educational contexts. Reflect on its significance as a European Cultural Itinerary since 1987, and discover how it has shaped European identity and the continent's cultural landscape.

Description

Learning objectives.

- Learning how to elaborate strategies of cultural heritage education

- To learn more about the Saint James Way – how it was born and how the connection between Santiago de Compostela and Europe shaped the architectural and cultural landscape

- To practice non-formal activities and working methods, to put into practice with students

- Be able to interpret heritage and to use heritage education as a tool to keep students' attention

- To promote personal interpretation and critical thinking based on the experiences taken on the course

Methodology & assessment

Certification details, pricing, packages and other information.

- Price: 480 Euro

- Package contents: Course

Additional information

- Language: English

- Target audience ISCED: Primary education (ISCED 1) Lower secondary education (ISCED 2) Upper secondary education (ISCED 3)

- Target audience type: Teacher Head Teacher / Principal Teacher Educator

- Learning time: 25 hours or more

Upcoming sessions

Porto and North of Portugal

Vocational subjects

Key competences, more courses by this organiser.

Azores, Preserving Nature: Teaching sustainability skills

Next upcoming session 09.09.2024 - 14.09.2024

Yoga and Meditation for Educators: Be a Great Teacher, Be Your Best Self

Next upcoming session 30.09.2024 - 05.10.2024

COMMENTS

Professionalism is a difficult concept to teach to healthcare professionals. Case-studies in written and video format have demonstrated to be effective teaching tools to improve a student's knowledge, but little is known about their impact on student behaviour. The purpose of this research study was to investigate and compare the impact of ...

Case Studies. In October 2023, the Research Partnership for Professional Learning (RPPL) shared a white paper about measuring teacher professional learning. It was collectively produced by a working group across RPPL's network, centering the voices and practices of organizations working alongside districts, schools, and teachers ...

T3. PROFESSIONALISM SCENARIOS AND CASE DISCUSSIONa nd Assessment Tools Guide by S Glover Takahashi. See Professional Role teacher tips appendix for this teaching tool ri e be) the action plan (e.g. who, what, how, whe )?

From teacher-related policy, to pedagogy, professionalism and training (to name a few), the study of teachers and teaching has been critically examined within and across a variety of empirical sites, theoretical perspectives, and methodological approaches. The collection of papers presented in this issue of Critical Studies in Education (CSE ...

Purpose Professionalism is a difficult concept to teach to healthcare professionals. Case-studies in written and video format have demonstrated to be effective teaching tools to improve a student ...

Case study 4: Systematic integrated programme of teaching professionalism Professionalism teaching and evaluation has been integrated within the entire undergraduate and postgraduate programme at McGill University (Cruess 2006 ).

Abstract This article addresses an under-researched area of teacher education by analysing teacher educators' constructions of their professionalism and the constituent professional resources and senses of identity on which that professionalism draws. The research is an embedded case study of 36 teacher educators in two Schools of Education in England, using questionnaires and interviews ...

Teaching professionalism - Why, What and How. Due to changes in the delivery of health care and in society, medicine became aware of serious threats to its professionalism. Beginning in the mid-1990s it was agreed that if professionalism was to survive, an important step would be to teach it explicitly to students, residents, and practicing ...

This qualitative case study (Stake, 1995) examined the kinds of participation and teacher reflection evident in a video-based Professional Learning Community. Case study was an appropriate methodology for uncovering and explicating the meaning and action of social learning (Erickson, 1986) that took place for this grade level team.

This article explores a case study where an expansion of teachers' pedagogical understanding was achieved through schools' collaboration with a non-government organisation (NGO), Evolve which is a not for profit organization based in Victoria Australia that works with at-risk young people, to deliver an education and leadership program to ...

Multiple meta-analyses have now documented small positive effects of teacher professional development (PD) on pupil test scores. However, the field lacks any va...

Purpose: Professionalism is a difficult concept to teach to healthcare professionals. Case-studies in written and video format have demonstrated to be effective teaching tools to improve a student's knowledge, but little is known about their impact on student behaviour. The purpose of this research study was to investigate and compare the impact of the 2 teaching tools on a student's ...

Pamela Osmond-Johnson Education, Sociology Alberta Journal of Educational Research 2017 This paper draws on data collected as part of a study of the discourses of teacher professionalism amongst union active teachers in the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Ontario. Interviews revealed… Expand 3 Highly Influenced PDF 11 Excerpts

Butters, D & Gann, C. (2022). Towards professionalism in higher education: An exploratory case study of struggles and needs of online adjunct professors. Online Learning, 26(3), 259-273. During the past decade, institutions of higher education have significantly increased their use of online modalities to deliver education services to meet society demands (Seaman et al., 2018). More people are ...

Phase II, August, 2010: Professional Development in the United States: Trends and Challenges Phase III, December 2010: Teacher Professional Learning in the United States: Case Studies of State Policies and Strategies This research was made possible through the support of a number of individuals and partner organizations.

The faculty development program designed to enhance the teaching and evaluation of professionalism at McGill University has been described previously. 44 For the purpose of this case study, we have decided to analyze what we have done since 1997 and how our program served as a catalyst in the process of undergraduate curricular change, using ...

This qualitative case study examines teacher professionalism in Kosovo in light of its rapidly developing education system. The study involves 14 teachers at the beginning of their careers (1-7 years of experience) examining teacher thinking against the evolving stages of teacher professionalism, namely pre-professionalism, autonomous ...

This article studies the meaning of professionalism in current attempts to professionalise teachers by means of education. The point of departure for our analysis is a small-scale survey among Swed...