An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Impression Management and Career Related Outcomes: A Systematic Literature Review

Esraa al-shatti.

1 Kedge Business School, Talence, France

2 Université de Pau et des Pays de l'Adour, Pau, France

Associated Data

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Despite the popularity of the term impression management (IM) in the literature, there is no consensus as how different types of IM (direct vs. indirect) and modes of interaction (face-to-face vs. online) promote career-related outcomes. While most empirical studies focus on direct IM, individuals engage in both types of IM and interaction modes, particularly indirect IM in the online context. Indeed, recent developments suggest that online interactions now prevail over face-to-face interactions, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, this study presents the first systematic literature review that differentiates between types of IM (direct vs. indirect) and modes of interaction (face-to-face vs. online) in a career development perspective. The review shows that direct IM is more widely studied in the face-to-face than online interaction mode, while indirect IM is neglected in both interaction modes. This study thus provides evidence of the need to investigate and differentiate between the different types of IM and interaction modes for career-related outcomes, highlighting some research gaps and directions for future inquiry.

Introduction

In recent years, impression management (IM) has received renewed attention among scholars (e.g., Liu et al., 2019 ; Yang et al., 2021 ). IM can be defined as the process by which “individuals attempt to control the impressions others form of them” (Leary and Kowalski, 1990 ). IM is of primary importance for individuals, since the impressions they make on others influences how others perceive and treat them (Bozeman and Kacmar, 1997 ; Gioaba and Krings, 2017 ). Amongst other tools, IM has revolutionized career development, offering competitive and sustainable career opportunities (Villeda and McCamey, 2019 ). For example, developing a resume and showing daily achievements online are unavoidable tools to enhance our career (El Ouirdi et al., 2015 ). In this vein, individuals using IM have higher chances of getting positive job interview ratings (Amaral et al., 2019 ). A better understanding of the mechanism linking IM and the career-related outcomes requires distinguishing between different IM types, as different IM mechanisms might lead to different career outcomes.

First, IM may depend on the mechanism used, creating favorable impressions through two different types: direct and indirect IM. Direct IM refers to “individuals self-promoting their own achievements and success” (Tal-Or and Drukman, 2010 ). Indirect IM (also called impression management by association) refers to “behaviors undertaken by individuals at work through associations with other colleagues to create favorable impressions of themselves” (Cialdini and Richardson, 1980 ). Whereas, the literature mainly considers direct IM, indirect IM is now widely used, especially on social media platforms that are invading our lives. Using posts associated with a particular company/institute and connecting and following people on social network platforms are good examples of indirect IM. Unfortunately, evidence is lacking on the difference that direct and indirect IM might have on career outcomes.

Second, IM may depend on the interaction mode adopted: face-to-face or online (Zhao et al., 2008 ). Face-to-face interaction refers to the visibility of a physical body in social interactions, such as physical characteristics (i.e., gender, race, and looks), physical settings (i.e., furniture and decor), and personal attributes (i.e., appearance, language, and manner). Online interactions instead denote the invisibility of the physical body in social interactions through text or voice messages (Zhao et al., 2008 ). Very few studies explore the notion of IM in the online context. Since recruiters increasingly use social networking platforms in their search for candidates (Villeda and McCamey, 2019 ), understanding online IM for potential career consequences, and differentiating between the online and face-to-face contexts that lead to different career-related outcomes, is pivotal.

In this systematic literature review composed of 55 articles in English published from 1980 to 2020, we explore how the different IM mechanisms (i.e., direct vs. indirect, and face-to-face vs. online) contribute to individuals' career development, and seek to answer the following questions:

- Are there any difference between IM types (direct vs. indirect) and career related outcomes?

- Does IM have similar effects on career development in the face-to-face and online contexts?

A key contribution of this study is providing insights on the state-of-the-art of IM and the difference between the types (direct vs. indirect) and interaction modes (face-to-face vs. online) for a better understanding of the relevance of IM and the resulting career-related outcomes.

Practical Insights Into the Prevalence of New Forms of IM

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals and organizations have been forced to operate through online technologies and social platforms (Bhaskar et al., 2021 ). Consulting the social networking profiles of potential candidates on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn is more than ever a fundamental human resource management practice in the modern organization (Villeda and McCamey, 2019 ). The information provided allows gauging the personality and interests of candidates and their alignment with the organizational culture.

The structure of social media enables individuals to share their achievements directly (direct IM) or through association with others (indirect IM). While direct IM has been widely examined (e.g., Andrews and Kacmar, 2001 ), indirect IM has become more salient in the contemporary context. Indeed, in the individual perspective, the extensive use of social media creates additional opportunities for indirect IM through allowing people to easily associate themselves with others on different social media platforms. In the organizational perspective, contemporary managers systematically consult social media that influence their professional decisions (Fieseler and Ranzini, 2015 ). For example, managers use social media to assess the suitability of a job seeker for a particular position (Van Iddekinge et al., 2016 ). Researching a job seeker's social media presence allows managers to see what others are saying about them. For instance, platforms such as LinkedIn allow users to recommend each other (considered indirect IM), and the testimonials on a user's platform can reveal what they might offer the company. Indirect IM is thus becoming fundamental in determining career outcomes.

As the prevalence and popularity of online social networking has grown extensively in recent years (Schivinski et al., 2020 ), IM has moved from the face-to-face to the online interaction mode. From the employee perspective, online social networking provides valuable resources, such as building business relations, identifying opportunities, and interacting with others (Nazir et al., 2020 ). From an organizational perspective, online social networking is recognized as a dominant communications tool (Dwivedi et al., 2020 ) that allows reducing recruitment costs (Leader-Chivée and Cowan, 2008 ). Interestingly, HR managers consider individuals' information on online social networking platforms as “honest” and accurate in comparison to the traditional résumé used in the face-to-face context (Zide et al., 2014 ). Likewise, Rowell ( 2010 ) shows that 70% of HR managers reject job applicants due to their online social networking behavior. The emergence and anchoring of new forms of IM lead us to differentiate between direct vs. indirect, and online vs. face-to-face IM, to understand their consequences on career outcomes.

Theoretical Impression Management Perspective

Individuals manage their impressions for career path purposes as IM can enhance their career opportunities. We next present the different types of IM linked to career-related outcomes.

Impression Management: From Direct to Indirect

Impression management refers to human behavior designed to obtain a favorable reaction from others (Felson, 1978 ; Bolino et al., 2008 ) through self-presentation (Goffman, 1959 ). IM theory was first conceptualized by Goffman ( 1959 ) who proposed a dramaturgical model of social life composed of two key players: an “actor” who engages in “IM tactics” and an “audience” that interacts with “actors” to create a desired image. IM tactics can be categorized as direct and indirect (Cialdini and Richardson, 1980 ). First, direct IM refers to individuals presenting their own achievements and success (Tal-Or and Drukman, 2010 ), including assertive and defensive tactics (Wayne and Kacmar, 1991 ; Stevens and Kristof, 1995 ). Assertive tactics are “proactive behaviors undertaken by individuals to create a specific identity to further their careers.” Defensive tactics are “reactive behaviors used by individuals following actions that may portray them negatively” seeking to “avoid negative career implications” (Andrews and Kacmar, 2001 ). Direct IM is premised to be linked with outcomes, including interview performance, job offers, hiring decisions, perceived qualifications, adequacy of information, and interviewer confidence (Gilmore and Ferris, 1989 ; Leary and Kowalski, 1990 ; Bolino et al., 2008 ).

Indirect IM refers to individuals managing their association with others for the purposes of creating a favorable impression of themselves (Cialdini and Richardson, 1980 ). Indirect tactics create impressions by involving a third party to manage the individual's image. Indirect IM supports the balance theory of Heider ( 1958 ) postulating that people tend to see things alike when they are associated with one another in order to maintain cognitive balance. According to Andrews and Kacmar ( 2001 ), indirect IM involves four connection-focused tactics: boasting, blurring, blaring, and burying. Boasting is defined as an individual embracing his or her positive connections by associating with favorable others. Burying is the individual tendency to conceal relationships with unsuccessful others for the sake of creating a perfect image of him or herself. Blaring is defined as an individual minimizing a connection with unfavorable others, especially in public. Finally, blurring refers to an individual's tendency to use the success of others, especially in the work place, as this will increase the perception of how successful he/she is in his/her career. Early work on indirect IM deems that it positively influences career-related outcomes, such as self-promotion (Cialdini, 1989 ).

Impression Management: From Face-to-Face to Online

Whatever the tactics, IM is used in two interaction modes: face-to-face and online. While IM research is extensive, studies linking the phenomenon with online social networking and career-related outcomes are scarce. However, the fluidity of social media platforms, especially their ability to address multiple audiences and diverse purposes, renders the online context interesting to understand IM (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010 ). Indeed, IM theory has been extended to the online context (Zhao et al., 2008 ; Hogan, 2010 ; Rosenberg and Egbert, 2011 ; Harrison and Budworth, 2015 ). Several researchers recognize the potential of online social networking and its relation to impression formation (Tong et al., 2008 ; Zhao et al., 2008 ). IM theory provides a framework to assess online impressions created by job seekers through the information they display (Barrick et al., 2009 ; Harrison and Budworth, 2015 ). Therefore, social media users ensure that their profile is catchy, aiming to influence how others perceive them (Rosenberg and Egbert, 2011 ). Indeed, individuals tend to follow and connect with particular people, companies, and associations for the sake of enhancing their image via indirect IM in the online context. This favorable image thus fosters positive career outcomes (El Ouirdi et al., 2015 ).

The Systematic Literature Review Methodology

To explore the effects of the different IM tactics on career related outcomes, we conducted a systematic literature review (SLR). SLR involves gathering extant literature on a subject that meets the predetermined inclusion criteria and answers the established research question(s). Its purpose is to formulate a broad perspective of a research area and provide an unbiased summary of the literature (Torraco, 2005 ; Borrego et al., 2014 ). Moreover, a well-structured SLR has numerous benefits, such as explaining a specific problem, revealing gaps and inconsistencies in the literature, and providing guidance for future research and practice (Baumeister and Leary, 1997 ). The methodology also ensures the generation of knowledge in a structured and systematic way from multiple studies. One of the key advantages of SLR is that it allows the restrictive retrieval of data from multiple databases, ensuring it is comparatively less biased than traditional literature reviews (Borrego et al., 2014 ).

Different authors have presented guiding principles to assist SLR researchers in constructing procedures that adhere to the methodology and the strategies to evaluate suitable research (Nightingale, 2009 ). Following the four stages of Tranfield et al. ( 2003 ) in this review, we first defined the search strategy and identified potential databases before embarking on the search (Higgins and Green, 2008 ). Second, we identified suitable articles based on the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Third, we undertook a synthesis of the selected studies that involved extracting and categorizing the data. Last, we analyzed the results and drew conclusions. For the sake of transparency and to ensure our literature review is reproducible, all the relevant steps are detailed next. Figure 1 represents the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009 ). It allows to have a better overview of the different steps taken for this SLR.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Searching the Empirical Literature

For this review, we checked different databases according to the IM definition. We then drew on seminal IM research papers to define the key terms and exact concepts later used to define the search terms and the time period. Based on these results and the information on the different terms used to describe IM, we identified the most promising search terms for our literature review as shown in Table 1 (e.g., impression management) using reliable databases, including Web of Science, Scopus, Science Direct, ProQuest, and Wiley. Web of Science and Scopus are citation databases that search multiple databases and sources to identify studies based on keywords, while the ProQuest search encompassed 18 databases.

Summary of search result.

| . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Impression Management | 706 | 748 | 144 | 847 | 105 |

| 2 | Impression Management + Human Resource | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 3 | Impression Management + Career | 6 | 5 | 0 | 11 | 1 |

| 4 | Impression Management + Social Media | 8 | 12 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| 5 | Impression Management + Social Networking | 16 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| 6 | Impression Management + Online | 11 | 16 | 2 | 10 | 3 |

| 7 | Impression Management + by association | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 8 | Impression Management + face-to-face | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | Impression Management + Job | 24 | 28 | 1 | 32 | 8 |

| 10 | Impression Management + connection focus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | Impression Management + tactics | 40 | 46 | 3 | 46 | 11 |

| 12 | Impression Management + indirect | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 13 | Impression Management + self-presentation | 19 | 15 | 3 | 21 | 4 |

| 14 | Impression Management + self-promotion | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

WS, Web of Science; SC, Scopus; SD, Science Direct; PQ, ProQuest; WI, Wiley. The search results are limited to the title field .

We used the following keywords in our search: IM, HR, career, social media, social networking, online, impression management by association, face-to-face , and job search in combination with impression management . We chose to begin our SLR in 1980 because critical theoretical IM frameworks were published at that time (Cialdini and Richardson, 1980 ).

After defining the research parameters, we performed the literature search initially resulting in 1,700 publications which we recorded and organized using Refworks and Excel (Callahan, 2010 ).

Screening the Literature

We screened the resulting 1,700 publications in two steps. In the first step, we searched for relevant publications using the defined search terms and filtered the results for the related literature. Following the literature search recommendations (Brocke et al., 2015 ), we performed a backward (screening the references using these papers) and forward search (publications that cite these papers). Additionally, we followed Levy and Ellis's ( 2006 ) ranking approach to select the appropriate journals. For our selection process, we picked the top tier IM journals enriched with those that focus on similar or adjacent topics, as our study includes online social networking as well as individuals' career-related outcomes. We selected numerous reputable journals, including Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Academy of Management, Journal of Management, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Career Development International , amongst many more. After screening the literature, 237 articles remained.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were set as part of the protocol prior to the start of the project. Included manuscripts needed to be (a) academic-peer-reviewed, (b) the focus of these publication needed to be centered around impression management, (c) these papers needed to be specifically aligned with career related outcomes from different mode of interactions (i.e., face-to-face and online) (d) in English, (e) the year of publication had to fall between 1980 and 2020. In contrast, we excluded: (1) Publication in non-English format, (2) duplicated research papers, (3) non-peer-reviewed articles (such as non-academic journals), (3) unpublished doctoral theses, and (4) gray literature (such as conferences and working papers).

We considered the 237 articles for inclusion and exclusion. The first step in this process entailed removing unrelated papers, reducing the number of records to 105. Next, we checked the articles for their relevance to our study based on the title, keywords, and abstract. After evaluating all publications, we identified 55 articles as relevant to our research topic. Table 2 provides the authors/date and career related outcomes according to the direct and indirect IM, face-to-face and online research focus. We extracted those variables from the individual papers: salary, promotion, performance assessment, job promotion, job interview ratings, interviewers' judgements, job interview evaluation, hiring recommendations, job offer, second job interview, recruiter evaluation, promotion scores, performance appraisal, supervisor liking, performance ratings, career success, performance evaluation, salary progression, promotability assessments, influence job search, recruitment process, selection process, job interview assessment, job performance, job design, employee selection, job satisfaction, job commitment, career satisfaction, adjusted salary, self-promotion, salary recommendations, and job opportunities.

Search results and classification.

| Face-to-face direct IM | Higgins et al. ( ) | Salary, promotion, performance assessment |

| Bolino et al. ( ) | Job promotion | |

| Baron ( ) | Job interview ratings (interview selection) | |

| Gilmore and Ferris ( ) | Influence interviewers' judgements | |

| Ellis et al. ( ) | Job Interview evaluation | |

| Higgins and Judge ( ) | Hiring recommendations, job offer | |

| Stevens and Kristof ( ) | Second job interview, job offer | |

| Kristof-Brown et al. ( ) | Job interview | |

| McFarland et al. ( ) | Recruiter evaluations, promotion scores | |

| Bolino and Turnley ( ) | Performance appraisal | |

| Wayne and Ferris ( ) | Supervisor liking, performance rating | |

| Judge and Bretz ( ) | Career success | |

| Ferris et al. ( ) | Performance evaluation | |

| Harris et al. ( ) | Performance ratings | |

| Treadway et al. ( ) | Performance ratings | |

| Wayne and Kacmar ( ) | Performance appraisal | |

| Wayne and Liden ( ) | Performance appraisal | |

| Barsness et al. ( ) | Performance appraisal | |

| Wayne et al. ( ) | Career success: performance ratings, salary progression, promotability assessments, | |

| Kacmar and Carlson ( ) | Influence job search and the recruitment process | |

| Swann et al. ( ) | Selection process | |

| Roulin and Bourdage ( ) | Job interview | |

| Gioaba and Krings ( ) | Job interview Job offer | |

| Von Baeyer et al. ( ) | Job interview | |

| Noor et al. ( ) | Job interview assessment | |

| Tsai et al. ( ) | Job interview evaluation | |

| Weiss and Feldman ( ) | Job interview | |

| Bourdage et al. ( ) | Job interview | |

| Tsai et al. ( ) | Job interview | |

| Chen et al. ( ) | Job interview | |

| Viswesvaran et al. ( ) | Job performance | |

| Zivnuska et al. ( ) | Job performance | |

| Foldes et al. ( ) | Job performance | |

| O'Connell et al. ( ) | Job performance | |

| Ispas et al. ( ) | Job performance | |

| Ingold et al. ( ) | Job performance | |

| Brouer et al. ( ) | Job performance | |

| Peck and Levashina ( ) | Job interview, job performance | |

| Probst et al. ( ) | Job performance | |

| Kacmar and Carlson ( ) | Job interview, performance appraisal | |

| Law et al. ( ) | Job offer | |

| Westphal ( ) | Job design | |

| Avery and McKay ( ) | Employee selection | |

| Harris et al. ( ) | Job satisfaction | |

| Asawo and George ( ) | Job commitment | |

| Cheng et al. ( ) | Career success: job performance, career satisfaction, adjusted salary | |

| Face-to-face indirect IM | Cialdini and Richardson ( ) | Self-promotion |

| Cialdini and de Nicholas ( ) | Self-promotion | |

| Finch and Cialdini ( ) | Self-promotion | |

| Andrews and Kacmar ( ) | Developed connection-focused tactics scale | |

| Online direct IM | Rosenberg and Egbert ( ) | Self-promotion |

| Stopfer et al. ( ) | Self-promotion | |

| Nestler and Back ( ) | Self-promotion | |

| Harrison and Budworth ( ) | Hiring and salary recommendations | |

| Paliszkiewicz and Madra-Sawicka ( ) | Job opportunities | |

| Online indirect IM | No studies found | No studies found |

Data Management and Analysis

To identify the current and future research topics according to the 55 articles identified, we developed a framework to classify the articles. As a starting point, we analyzed studies in the face-to-face context, including career-related outcomes of direct and indirect IM. Then, we extended our analysis to the online context. Table 3 shows the classification by frequency, differentiating between the interaction modes (face-to-face vs. online) and career-related outcomes of the IM mechanisms (direct vs. indirect) adopted. Separating the interaction modes (face-to-face vs. online) allows identifying the gap in the literature and illustrating the importance of understanding both modes and IM tactics to achieve the desired career-related outcome.

IM studies.

| IM study focus | Face-to-face direct IM | 46 | 79% |

| Face-to-face indirect IM | 4 | 12% | |

| Online direct IM | 5 | 9% | |

| Online indirect IM | 0 | 0% | |

| Total | 55 | 100% |

Indeed, while most of the studies identified deal with direct IM in the online context, some older studies explore the link between indirect face-to-face IM and career-related outcomes. However, while several authors integrate direct IM in the online context, we found no studies dealing with indirect IM in the online context.

Direct IM in the Face-to-Face Context

Regarding direct IM in the face-to-face context, most studies focus on the link between IM and job interview, job performance, and other career-related outcomes as detailed next.

Direct Face-to-Face IM and Job Interview

Numerous studies focus on the effect of direct face-to-face IM, with job interview as the most common career-related outcome (Gilmore and Ferris, 1989 ; Baron, 1993 ; Ellis et al., 2002 ; Kristof-Brown et al., 2002 ; Law et al., 2002 ; Weiss and Feldman, 2006 ; Noor et al., 2017 ; Peck and Levashina, 2017 ; Roulin and Bourdage, 2017 ). For instance, Von Baeyer et al. ( 1981 ) study a male interviewer's knowledge and attitude toward female candidates in a stereotyped environment. Kacmar and Carlson ( 1994 ) focus on the process of women searching for jobs using direct IM. Stevens and Kristof ( 1995 ) examine the relationship between direct IM and job interview outcome. Tsai et al. ( 2005 ) explore the effect of direct IM tactics on job interviews, showing these have a positive influence on interviewer evaluation. Chen et al. ( 2010 ) study applicant direct IM tactics in job interviews with the moderating role of interviewer affectivity. Empirical evidence shows that direct IM tactics, such as self-focused IM, other-focused IM, and non-verbal IM, positively influence interviewer evaluations through self-focused direct IM.

Tsai et al. ( 2010 ) study direct IM tactics in job interviews with an emphasis on three defensive applicant tactics: apologies, justifications, and excuses. Collecting empirical data through observing applicant interviews, they explore the moderating effect of negative competence- and integrity-related concerns on the three direct IM defensive tactics, finding that the apologies tactic has the strongest impact.

Swann et al. ( 2015 ) study direct IM and job interviews in the medical context. Although unable to provide conclusive evidence, the authors offer a brief overview of direct IM over time, and encourage training models that provide a logical and systematic approach for candidates to ensure that the results of interview selection are closely correlated with good clinical outcomes for successful candidates. Bourdage et al. ( 2017 ) show the difference between reality and faking in job interviews. Direct IM is used to impress interviewers, as candidates attempt to create a likable impression and gain job opportunities. They approach direct IM from various perspectives, such as being honest and deceptive, IM effectiveness, IM as a shield against discrimination, and IM as dyadic and beyond the applicant.

Gioaba and Krings ( 2017 ) study effective ways of mitigating discrimination against older applicants based on direct IM in job interviews. They find that the use of direct IM by older applicants provides stronger job interview and hiring opportunities. Similarly to Bourdage et al. ( 2017 ), Roulin and Bourdage ( 2017 ) extend the study of the use of honesty and deceptive direct IM across multiple job interviews.

Overall, these studies show that direct IM tactics lead to positive effects on job interviews in the face-to-face interaction mode.

Direct Face-to-Face IM and Job Performance

Numerous scholars study the positive effect of direct IM in the face-to-face interaction mode on individuals' job performance (Wayne and Ferris, 1990 ; Wayne and Kacmar, 1991 ; Ferris et al., 1994 ; Wayne and Liden, 1995 ; Bolino and Turnley, 2003 ; Zivnuska et al., 2004 ; Barsness et al., 2005 ; Foldes et al., 2006 ; Harris et al., 2007 ; O'Connell et al., 2011 ).

Viswesvaran et al. ( 2001 ) study direct face-to-face IM and job performance by exploring the relationship between direct IM scale scores, overall job performance, and managerial interpersonal interactions. Zivnuska et al. ( 2004 ) investigate the interactive effect of organizational politics and direct IM on supervisor ratings of employee performance. In their study, Ispas et al. ( 2014 ) find a significant link between direct IM and objective job performance. Another study in the field of direct IM and job performance is that of Ingold et al. ( 2015 ) who focus on direct IM, faking in the selection context, and job performance. The authors find that candidates that faked direct IM in interviews also falsified a personality inventory, and that this deceit is positively related to supervisor job performance rating.

Brouer et al. ( 2016 ) study direct IM and the ability to manage resources with job performance as mediator. They find that higher levels of social resources, such as reputation and leader-member exchange, are positively related to job performance. Peck and Levashina ( 2017 ) study direct IM in relation to interviews and job performance, finding that direct IM has a stronger impact on interview and job performance rating. The most recent study is that of Probst et al. ( 2019 ) investigating the relationship between job insecurity and direct IM to determine a relationship between supervisor-focused IM, lower job insecurity, positive in-role behavior, and job performance. Accordingly, if direct IM is correctly practiced, irrespective of whether true or false, it will lead to a better job performance rating.

Overall, the use of direct IM at the workplace has a positive effect on employees' job performance rating.

Direct Face-to-Face IM and Other Career Outcomes

Several studies link direct face-to-face IM and different career-related outcomes, such as salary increase, hiring recommendations, promotions, job commitment, and overall career success (Judge and Bretz, 1994 ; Kacmar and Carlson, 1994 ; Wayne et al., 1997 ; Higgins et al., 2003 ; McFarland et al., 2003 ; Higgins and Judge, 2004 ; Avery and McKay, 2006 ; Bolino et al., 2008 ; Westphal, 2010 ; Asawo and George, 2018 ).

For example, Kang et al. ( 2012 ) investigate the relationship between job insecurity and IM work-related behaviors, finding that the perception of job insecurity leads to reduced extra-role and IM behavior. Evidently, the intensity of withdrawal increases with increased employability. Harris et al. ( 2013 ) study IM behaviors in relation to IM culture and job outcomes, such as performance, promotion, compensation, and IM tactics (intimidation and exemplification), finding that intimidation has negative effects, while exemplification has positive effects on IM tactics. Cheng et al. ( 2014 ) focus on the interactive effects of task performance and IM tactics on career outcomes, finding that the relationship between task performance and career satisfaction is greater among employees who frequently use self-promotion.

Generally, in the face-to-face interaction mode, a strong relation is found between direct IM and career-related outcomes, such as salary increase, job promotion, job commitment, and hiring recommendations.

Indirect IM in the Face-to-Face Context

While generally few scholars focus on indirect compared to direct IM, some studies consider indirect IM in the face-to-face interaction mode with different career-related outcomes, such as job engagement and job satisfaction. Cialdini and Richardson ( 1980 ) show that individuals tend to use indirect IM tactics, for example, highlighting successful connections with others to enhance their personal image (prestige). Cialdini ( 1989 ) shows that an individual's image can be enhanced by associating with successful others and disassociating from failures. Finch and Cialdini ( 1989 ) reveal that unit-connection plays an essential role in individuals' image simply by associating themselves by birth date with favorable or unfavorable individuals. Finally, Andrews and Kacmar ( 2001 ) develop and validate an indirect IM scale, albeit not adopted in relation to career-related outcomes.

Overall, these studies show that indirect IM has positive effects on career-related outcomes that are underestimated.

Direct IM in the Online Context

Some researchers have recently focused on direct IM in the online context (Rosenberg and Egbert, 2011 ; Nestler and Back, 2013 ; Stopfer et al., 2013 ; Harrison and Budworth, 2015 ; Paliszkiewicz and Madra-Sawicka, 2016 ). For instance, Paliszkiewicz and Madra-Sawicka ( 2016 ) illustrate the importance of online IM on LinkedIn to benefit from the platform features and gain job opportunities. Harrison and Budworth ( 2015 ) find a positive relation between verbal and non-verbal IM on hiring and salary recommendations in social media platforms. Three studies deal with the importance of IM in online social networks for self-promotion purposes (Rosenberg and Egbert, 2011 ; Nestler and Back, 2013 ; Stopfer et al., 2013 ).

Overall, these studies show the importance of using direct IM in the online context to obtain the desired career outcomes.

Indirect IM in the Online Context

As mentioned, we found no studies that deal specifically with indirect IM in the online context.

Our analysis of the 55 studies provides deep insights on IM and career-related outcomes in both the face-to-face and online context. Figure 2 provides an illustration of what is IM and what are its associations.

Individuals shape their impressions in accordance with how they represent themselves and what they want to show recruiters and managers, both in a direct and indirect way, and in the face-to-face and online contexts. We do not observe any major differences between IM mechanisms (direct vs. indirect) and interaction mode (face-to-face vs. online) in relation to their positive role in career-related outcomes.

Indeed, both the direct vs. indirect IM mechanisms are linked to individuals' career success. Regarding career-related outcomes, such as job interviews and job performance, most studies naturally relate to direct IM in the face-to-face interaction mode. In the very few studies that deal with the online interaction mode, self-promotion is the common career-related outcome. For a better overview of IM in all contexts and circumstances, further research is needed on the different potential outcomes. For example, in the online mode, it may be worth exploring whether IM is so powerful that it impacts job performance despite the absence of direct physical interactions.

In addition, scholars have focused mainly on direct IM, neglecting the importance of indirect IM. In particular, no studies focus on the indirect online interaction mode, while only 4 deal with indirect face-to-face interactions. There is thus a gap in the literature in differentiating between direct vs. indirect IM in the face-to-face vs. online interaction modes, which is crucial to career-related outcomes. To fully capture the IM phenomenon, scholars should consider the impact of indirect IM in general, and specifically in the online context, on career-related outcomes.

Our review clearly shows the need to differentiate IM (direct vs. indirect) in both contexts (face-to-face vs. online) and the career-related outcomes. Even if not our main aim, this systematic literature review allows highlighting some additional unanswered questions for future researchers to address as specified in Table 4 .

Indirect IM questions and future research avenues.

| Unintended indirect IM in the job search context |

| Effects of indirect IM in the job search context: online vs. face-to-face |

| Deceptive vs. honest indirect IM in the job search context |

| Which connection-focused tactic is mostly used in the job search context? |

| Combination or single use of connection-focused tactics? |

| Antecedents of indirect IM |

| Indirect IM in the online and face-to-face context |

| Unintended use of indirect IM in the job search context |

| Intended use of indirect IM in the job search context |

| Influence of social networking platforms on individuals' indirect IM |

| Job seekers use of indirect IM vs. employers' reactions to indirect IM |

| Is building relationships online the main factor of indirect IM? |

| How do individuals using social networking react to indirect IM? |

Implications for Individuals and Career Counselors

Research on IM (direct vs. indirect) has practical implication for individuals and career counselors. For individuals, making the right association with successful others and disassociating from unsuccessful others is a significant element in succeeding at work and enhancing prestige (Andrews and Kacmar, 2001 ). Further, the literature shows that individuals who create an impression need to maintain this impression even at later stages to manage and strengthen the image in the minds of others (Higgins et al., 2003 ; Barrick et al., 2009 ). First, associating with a third party is theoretically proven to create a cognitive balance in the mind of the others (Kacmar et al., 2011 ). As such, individuals in the workplace engage with higher reputation individuals and learn from the best because associating with unfavorable others will affect their career outcome. Second, individuals using online social networking must pay attention to who they are connected and associated with, as this will lead to either valuable or adverse future returns. Individuals are frequently evaluated for career purposes enabled by the accessibility of social network platforms.

A better understanding of online social networking is also crucial for career counselors to stay up to date with digital trends. Scholars indicate the emergence of online social networking for both job seekers and career counselors (Bolino et al., 2016 ). According to the analysis of social networking platforms, career counselors mainly use LinkedIn when checking individuals or job seekers for career purposes, as it is used more for professional networking, while Facebook and Twitter also share non-professional content, potentially leading to bias. However, every jobseeker has a social life, and rejecting individuals because of their Facebook content may lead to disregarding those who could in fact benefit the organization.

Limitations

This SLR took great care to avoid any publication bias. First, the Preferred Reporting Items in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram shows the clarity and credibility of our research (Moher et al., 2009 ). This universally accepted evidence-based checklist reduces publication bias. Second, we were highly concerned about the gray literature. However, we decided to remove gray literature from our inclusion criteria. Gray literature is composed of working papers, conferences and articles that are not academically peer-reviewed (Adams et al., 2016 ). We are aware that some authors encourage to include gray literature (e.g., Briner and Denyer, 2012 ). However, we follow the recommendation of Kraus et al. ( 2020 ) to exclude it. Traditional reviews are criticized for subjective literature selection and quality appraisal (Denyer and Tranfield, 2006 ). Indeed, by integrated peer review articles, the process is more transparent and replicable. Also, the selected papers have been checked through the academic process. It thus represents a guarantee of quality. We acknowledge that this strategy can still be responsible of a publication bias as all papers of good quality are not all published in peer reviewed journals. Third, we considered five main and highly reliable database to reduce the publication bias such as Web of Science, Scopus, Wiley, Science Direct and Proquest. Finally, the included papers were checked by two authors to enhance the credibility and to evaluate the quality of the methodology of the papers that are included in the SLR. Because we chose only peer reviewed articles in main research database and because all papers have been checked by two authors to detect any quality problem, we can ensure a good methodological quality of the included studies.

Besides, our aim was to do a systematic literature review in order to compare direct vs. indirect and online vs. face to face IM. Unfortunately, due to the weak number of peer reviewed publications about indirect IM and online IM, a quantitative meta-analysis would have not been appropriated. Nevertheless, it would be very insightful to do in the future a quantitative analysis of the impact of different types of IM on career related outcomes when more publications will be available.

This literature review shows that indirect IM is often overlooked by researchers, highlighting the need for further investigations on both interactions modes (face-to-face vs. online). While the literature shows that job seekers and recruiters use online social networking to create a positive image, the field has received limited academic attention, and further research is needed to understand this phenomenon in greater detail.

Data Availability Statement

Author contributions.

EA-S did the SLR. MO helped in the writing of the paper. All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Adams R. J., Smart P., Huff A. S. (2016). Shades of grey: guidelines for working with the grey literature in systematic reviews for management and organizational studies . Int. J. Manag. Rev. 19 , 432–454. 10.1111/ijmr.12102 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Amaral A. A., Powell D. M., Ho J. L. (2019). Why does impression management positively influence interview ratings? the mediating role of competence and warmth . Int. J. Select. Assess. 27 , 315–327. 10.1111/ijsa.12260 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Andrews M. C., Kacmar K. (2001). Impression management by association: construction and validation of a scale . J. Vocat. Behav. 58 , 142–161. 10.1006/jvbe.2000.1756 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Asawo S. P., George B. M. (2018). Leaders' intimidation impression management and subordinates' affective job commitment in Nigeria . Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 21 , 2–16. 10.1108/IJOTB-03-2018-002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Avery D. R., McKay P. F. (2006). Target practice: an organizational impression management approach to attracting minority and female job applicants . Pers. Psychol. 59 , 157–187. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00807.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baron R. A. (1993). Interviewers' moods and evaluations of job applicants: the role of applicant qualifications . J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 23 , 253–271. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1993.tb01086.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barrick M. R., Shaffer J. A., DeGrassi S. W. (2009). What you see may not be what you get: relationships among self-presentation tactics and ratings of interview and job performance . J. Appl. Psychol. 94 , 1394–1411. 10.1037/a0016532 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barsness Z. I., Diekmann K. A., Seidel M. L. (2005). Motivation and opportunity: the role of remote work, demographic dissimilarity, and social network centrality in impression management . Acad. Manag. J 48 , 401–419. 10.5465/amj.2005.17407906 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baumeister R. F., Leary M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1 , 311–320. 10.1037/1089-2680.1.3.311 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bhaskar S., Nurtazina A., Mittoo S., Banach M., Weissert R. (2021). Editorial: telemedicine during and beyond COVID-19 . Front. Public Health 9 :662617. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.662617 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bolino M. C., Kacmar K. M., Turnley W. H., Gilstrap J. B. (2008). A multilevel review of impression management motives and behaviors . J. Manag. 34 , 1080–1109. 10.1177/0149206308324325 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bolino M. C., Long D., Turnley W. (2016). Impression management in organizations: critical questions, answers, and areas for future research . Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 3 , 377–406. 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062337 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bolino M. C., Turnley W. H. (2003). More than one way to make an impression: exploring profiles of impression management . J. Manag. 29 , 141–160. 10.1177/014920630302900202 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Borrego M., Foster M. J., Froyd J. E. (2014). Systematic literature reviews in engineering education and other developing interdisciplinary fields . J. Eng. Educ. 103 , 45–76. 10.1002/jee.20038 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bourdage J. S., Roulin N., Levashina J. (2017). Editorial: impression management and faking in job interviews . Front. Psychol. 8 :1294. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01294 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bozeman D. P., Kacmar K. (1997). A cybernetic model of impression management processes in organizations . Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 69 , 9–30. 10.1006/obhd.1996.2669 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Briner R. B., Denyer D. (2012). “Systematic review and evidence synthesis as a practice and scholarship tool,” in Handbook of Evidence-Based Management: Companies, Classrooms, and Research , ed Rousseau D. M. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press; ), 17. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brocke J. V., Simons A., Riemer K., Niehaves B., Plattfaut R., Cleven A. (2015). Standing on the shoulders of giants: challenges and recommendations of literature search in information systems research . Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 31 , 205–224. 10.17705/1CAIS.03709 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brouer R. L., Gallagher V. C., Badawy R. L. (2016). Ability to manage resources in the impression management process: the mediating effects of resources on job performance . J. Bus. Psychol. 31 , 515–531. 10.1007/s10869-015-9426-5 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Callahan J. L. (2010). Constructing a manuscript: distinguishing integrative literature reviews and conceptual and theory articles . Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 9 , 300–304. 10.1177/1534484310371492 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen C.-C., Yang I. W.-F., Lin W.-C. (2010). Applicant impression management in job interview: the moderating role of interviewer affectivity . J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 83 , 739–757. 10.1348/096317909X473895 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cheng J.-W., Chiu W.-L., Chang Y.-Y., Johnstone S. (2014). Do you put your best foot forward? interactive effects of task performance and impression management tactics on career outcomes . J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 146 , 621–640. 10.1080/00223980.2013.818929 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cialdini R. B. (1989). “Indirect tactics of image management: beyond basking,” in Impression Management in the Organization , eds Giacolone R. A., Rosenfeld P. (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; ), 45–56. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cialdini R. B., de Nicholas M. E. (1989). Self-presentation by association . J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57 , 626–631. 10.1037/0022-3514.57.4.626 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cialdini R. B., Richardson K. D. (1980). Two indirect tactics of impression management: basking and blasting . J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 39 , 406–415. 10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.406 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Denyer D., Tranfield D. (2006). Using qualitative research synthesis to build an actionable knowledge base . Manag. Decis. 44 , 213–227. 10.1108/00251740610650201 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dwivedi Y. K., Ismagilova E., Hughes D. L., Carlson J., Filieri R., Jacobson J., et al.. (2020). Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: perspectives and research propositions . Int. J. Inf. Manag. 59 :102168. 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102168 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- El Ouirdi M., Segers J., El Ouirdi A., Pais I. (2015). Predictors of job seekers' self-disclosure on social media . Comput. Hum. Behav. 53 , 1–12. 10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.039 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ellis A. P. J., West B. J., Ryan A. M., DeShon R. P. (2002). The use of impression management tactics in structured interviews: a function of question type? J. Appl. Psychol. 87 , 1200–1208. 10.1037/0021-9010.87.6.1200 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Felson R. B. (1978). Aggression as impression management . Soc. Psychol. Q. 41 , 205–213. 10.2307/3033557 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ferris G. R., Judge T. A., Rowland K. M., Fitzgibbons D. E. (1994). Subordinate influence and the performance evaluation process: test of a model . Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 58 , 101–135. 10.1006/obhd.1994.1030 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fieseler C., Ranzini G. (2015). The networked communications manager . Corp. Commun. Int. J. 20 , 500–517. 10.1108/CCIJ-02-2015-0009 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Finch J. F., Cialdini R. B. (1989). Another indirect tactic of (self-) image management . Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 15 , 222–232. 10.1177/0146167289152009 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Foldes H. J., Ones D. S., Sinangil H. K. (2006). Neither here, nor there: impression management does not predict expatriate adjustment and job performance . Psychol. Sci. 48 , 357–368. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/26669028.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilmore D. C., Ferris G. R. (1989). The effects of applicant impression management tactics on interviewer judgments . J. Manag. 15 , 557–564. 10.1177/014920638901500405 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gioaba I., Krings F. (2017). Impression management in the job interview: an effective way of mitigating discrimination against older applicants? Front. Psychol. 8 , 1–12. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00770 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goffman E. (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life . New York, NY: Anchor Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Harris K. J., Gallagher V. C., Rossi A. M. (2013). Impression management (IM) behaviors, IM culture, and job outcomes . J. Manag. Issues 25 , 154–171. [ Google Scholar ]

- Harris K. J., Kacmar K. M., Zivnuska S., Shaw J. D. (2007). The impact of political skill on impression management effectiveness . J. Appl. Psychol. 92 , 278–285. 10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.278 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harrison J. A., Budworth M. (2015). Unintended consequences of a digital presence . Career Dev. Int. 20 , 294–314. 10.1108/CDI-06-2014-0080 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Heider F. (1958). The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations . New York, NY: Wiley. [ Google Scholar ]

- Higgins C. A., Judge T. A. (2004). The effect of applicant influence tactics on recruiter perceptions of fit and hiring recommendations: a field study . J. Appl. Psychol. 89 , 622–632. 10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.622 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Higgins C. A., Judge T. A., Ferris G. R. (2003). Influence tactics and work outcomes: a meta-analysis . J. Organ. Behav. 24 , 89–106. 10.1002/job.181 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Higgins J., Green S. (2008). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions . London: The Cochrane Collaboration. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hogan B. (2010). The presentation of self in the age of social media: distinguishing performances and exhibitions online . Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 30 , 377–386. 10.1177/0270467610385893 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ingold P. V., Kleinmann M., König C. J., Melchers K. G. (2015). Shall we continue or stop disapproving of self-presentation? evidence on impression management and faking in a selection context and their relation to job performance . Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 24 , 420–432. 10.1080/1359432X.2014.915215 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ispas D., Iliescu D., Ilie A., Sulea C., Askew K., Rohlfs J. T., et al.. (2014). Revisiting the relationship between impression management and job performance . J. Res. Pers. 51 , 47–53. 10.1016/j.jrp.2014.04.010 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Judge T. A., Bretz R. D. (1994). Political influence behavior and career success . J. Manag. 20 , 43–65. 10.1177/014920639402000103 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kacmar K. M., Bachrach D. G., Harris K. J., Shaw J. D., Noble D. (2011). The moderating effect of impression management on the organizational citizenship behaviour-voluntary turnover relationship . J. Appl. Manag. Entrep. 16 , 4–26. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kacmar K. M., Carlson D. S. (1994). Using impression management in women's job search process . Am. Behav. Sci. 37 , 1–15. 10.1177/0002764294037005008 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kacmar K. M., Carlson D. S. (1999). Effectiveness of impression management tactics across human resource situations1 . J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 29 , 1293–1315. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb02040.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kang D.-S., Gold J., Kim D. (2012). Responses to job insecurity the impact on discretionary extra-role and impression management behaviors and the moderating role of employability . Career Dev. Int. 17 , 314–332. 10.1108/13620431211255815 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kaplan A., Haenlein M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! the challenges and opportunities of social media . Bus. Horiz. 53 , 59–68. 10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kraus S., Breier M., Dasí-Rodríguez S. (2020). The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research . Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 16 , 1023–1042. 10.1007/s11365-020-00635-4 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kristof-Brown A., Barrick R. M., Franke M. (2002). Applicant impression management: dispositional influences and consequences for recruiter perceptions of fit and similarity . J. Manag. 28 , 27–46. 10.1177/014920630202800103 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Law K., Mobley W. H., Wong C.-S. (2002). Impression management and faking in biodata scores among Chinese jobseekers . Asia Pacific J. Manag. 19 , 541–556. 10.1023/A:1020521726390 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leader-Chivée L., Cowan E. (2008). Networking the way to success: online social networks for workplace and competitive advantage . People Strategy 31 , 40–46. [ Google Scholar ]

- Leary M. R., Kowalski R. M. (1990). Impression management: a literature review and two-component model . Psychol. Bull. 107 , 34–47. 10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.34 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levy Y., Ellis T. J. (2006). A systems approach to conduct an effective literature review in support of information systems research . Informing Sci. Int. J. Emerg. Transdiscipl. 9 , 181–212. 10.28945/479 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu F., Chow I. H., Huang M. (2019). Increasing compulsory citizenship behavior and Workload: Does impression management matter? Front. Psychol. 10 :1726. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01726 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McFarland L. A., Ryan A. M., Kriska S. D. (2003). Impression management use and effectiveness across assessment methods . J. Manag. 29 , 641–661. 10.1016/S0149-2063_03_00030-8 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement . BMJ 6 :e1000097. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nazir M., Tian J., Hussain I., Arshad A., Shad M. A. (2020). Examining the relationship of online social networking sites' activities, customers' brand choice, and brand perception in Health-related businesses . Front. Psychol. 11 :546087. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.546087 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nestler S., Back M. D. (2013). Applications and extensions of the lens model to understand interpersonal judgments at zero acquaintance . Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 22 , 374–379. 10.1177/0963721413486148 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nightingale A. (2009). A guide to systematic literature reviews . Surgery (Oxford) 27 , 381–384. 10.1016/j.mpsur.2009.07.005 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Noor M. S. N. F., Tab M. F., Kamarulzaman R. (2017). Exploring job interview skills of future engineers: application of appraisal analysis assessment and verbal impression management . J. Tech. Educ. Train. 9 , 87–99. [ Google Scholar ]

- O'Connell M. S., Kung M.-C., Tristan E. (2011). Beyond impression management: evaluating three measures of response distortion and their relationship to job performance . Int. J. Sel. Assess. 19 , 340–351. 10.1111/j.1468-2389.2011.00563.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paliszkiewicz J., Madra-Sawicka M. (2016). Impression management in social media: the example of LinkedIn . Management 11 , 203–212. [ Google Scholar ]

- Peck J. A., Levashina J. (2017). Impression management and interview and job performance ratings: a meta-analysis of research design with tactics in mind . Front. Psychol. 8 :201. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00201 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Probst T. M., Jiang L., Bohle S. A. L. (2019). Job insecurity and impression management Which is the horse and which is the cart when it comes to job performance? Career Dev. Int. 25 , 306–324. 10.1108/CDI-04-2018-0119 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rosenberg J., Egbert N. (2011). Online impression management: personality traits and concerns for secondary goals as predictors of self-presentation tactics on Facebook . J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 17 , 1–18. 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2011.01560.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Roulin N., Bourdage J. S. (2017). Once an impression manager, always an impression manager? antecedents of honest and deceptive impression management use and variability across multiple job interviews . Front. Psychol. 8 :29. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00029 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rowell E. (2010). Didn't Get Hired Because of Facebook? You're Not Alone . Available online at: https://ezinearticles.com/?Didnt-Get-Hired-Because-of-Facebook?-Youre-Not-Aloneandid=3669704 (accessed August 17, 2019).

- Schivinski B., Brzozowska-Woś M., Stansbury E., Satel J., Montag C., Pontes H. M. (2020). Exploring the role of social media use motives, psychological well-being, self-esteem, and affect in problematic social media use . Front. Psychol. 11 :617140. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.617140 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stevens C. K., Kristof A. L. (1995). Making the right impression: a field study of applicant impression management during job interviews . J. Appl. Psychol. 80 , 587–606. 10.1037/0021-9010.80.5.587 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stopfer J. M., Egloff B., Nestler S., Back M. D. (2013). Being popular in online social networks: how agentic, communal, and creativity traits relate to judgments of status and liking . J. Res. Pers. 47 , 592–598. 10.1016/j.jrp.2013.05.005 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Swann R. F., Bolton D. M., Lawrentschuk N. (2015). The career medical interview: solid selector or just ‘impression management? BJU Int. 116 , 1–4. 10.1111/bju.13269 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tal-Or N., Drukman D. (2010). Third-person perception as an impression management tactic . Media Psychol. 13 , 301–322. 10.1080/15213269.2010.503516 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tong S. T., Van Der Heide B., Langwell L., Walther J. B. (2008). Too much of a good thing? the relationship between number of friends and interpersonal impressions on Facebook . J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 13 , 531–549. 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2008.00409.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Torraco R. J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: guidelines and examples . Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 4 , 356–367. 10.1177/1534484305278283 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tranfield D., Denyer D., Smart P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review . Br. J. Manag. 14 , 207–222. 10.1111/1467-8551.00375 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Treadway D. C., Ferris G. R., Duke A. B., Adams G. L., Thatcher J. B. (2007). The moderating role of subordinate political skill on supervisors' impressions of subordinate ingratiation and ratings of subordinate interpersonal facilitation . J. Appl. Psychol. 92 , 848–855. 10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.848 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tsai W., Chen C., Chiu S. (2005). Exploring boundaries of the effects of applicant impression management tactics in job interviews . J. Manag. 31 , 108–125. 10.1177/0149206304271384 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tsai W.-C., Huang T.-C., Wu C.-Y., Lo I.-H. (2010). Disentangling the effects of applicant defensive impression management tactics in job interviews . Int. J. Sel. Assess. 18 , 131–140. 10.1111/j.1468-2389.2010.00495.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Iddekinge C., Lanivich S., Roth P., Junco E. (2016). Social media for selection? validity and adverse impact potential of a facebook-based assessment . J. Manag. 42 , 1811–1835. 10.1177/0149206313515524 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Villeda M., McCamey R. (2019). Use of social networking sites for recruiting and selecting in the hiring process . Int. Bus. Res. 12 , 66–78. 10.5539/ibr.v12n3p66 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Viswesvaran C., Ones D. S., Hough L. M. (2001). Do impression management scales in personality inventories predict managerial job performance ratings? Int. J. Sel. Assess. 9 , 277–289. 10.1111/1468-2389.00180 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Von Baeyer C. L., Sherk D. L., Zanna M. P. (1981). Impression management in the bob interview: when the female applicant meets the male (chauvinist) interviewer . Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 7 , 45–51. 10.1177/014616728171008 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wayne S. J., Ferris G. R. (1990). Influence tactics, affect, and exchange quality in supervisor-subordinate interactions: A laboratory experiment and field study . J. Appl. Psychol. 75 , 487–499. 10.1037/0021-9010.75.5.487 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wayne S. J., Kacmar K. (1991). The effects of impression management on the performance appraisal process . Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 48 , 70–88. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90006-F [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wayne S. J., Liden R. C. (1995). Effects of impression management on performance ratings: a longitudinal study . Acad. Manag. J. 38 , 232–260. 10.2307/256734 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wayne S. J., Liden R. C., Graf I. K., Ferris G. R. (1997). The role of upward influence tactics in human resource decisions . Pers. Psychol. 50 , 979–1006. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1997.tb01491.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weiss B., Feldman R. S. (2006). Looking good and lying to do it: deception as an impression management strategy in job interviews . J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 36 , 1070–1086. 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00055.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Westphal J. D. (2010). An impression management perspective on job design: the case of corporate directors . J. Organ. Behav. 31 , 319–327. 10.1002/job.643 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yang H., Zhang L., Wu Y. J., Shi H., Xie S. (2021). Influence of entrepreneurial orientation on venture capitalists' initial trust . Front. Psychol . 12 :633771. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633771 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhao S., Grasmuck S., Martin J. (2008). Identity construction on Facebook: digital empowerment in anchored relationships . Comput. Hum. Behav. 24 , 1816–1836. 10.1016/j.chb.2008.02.012 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zide J., Elman B., Shahani-Denning C. (2014). LinkedIn and recruitment: how profiles differ across occupations . Empl. Relat. 36 , 583–604. 10.1108/ER-07-2013-0086 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zivnuska S., Kacmar K. M., Witt L. A., Carlson D. S., Bratton V. K. (2004). Interactive effects of impression management and organizational politics on job performance . J. Organ. Behav. 25 , 627–640. 10.1002/job.262 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY article

Impression management and interview and job performance ratings: a meta-analysis of research design with tactics in mind.

- Department of Management and Information Systems, Kent State University, Kent, OH, USA

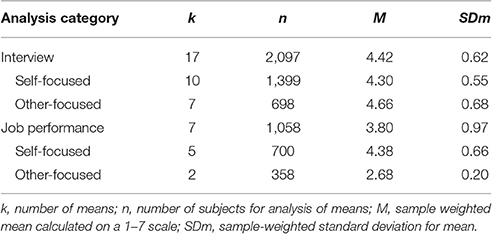

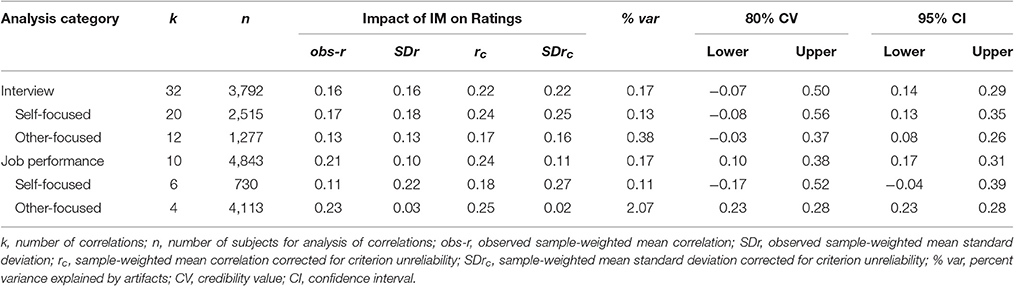

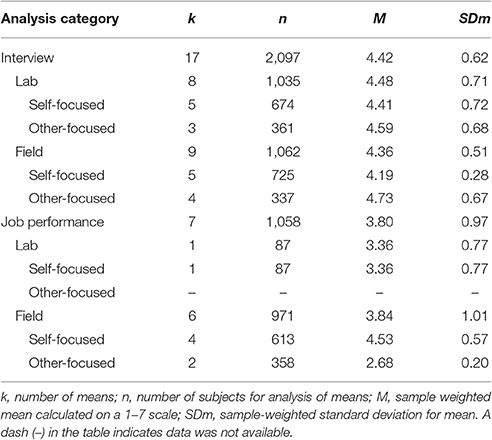

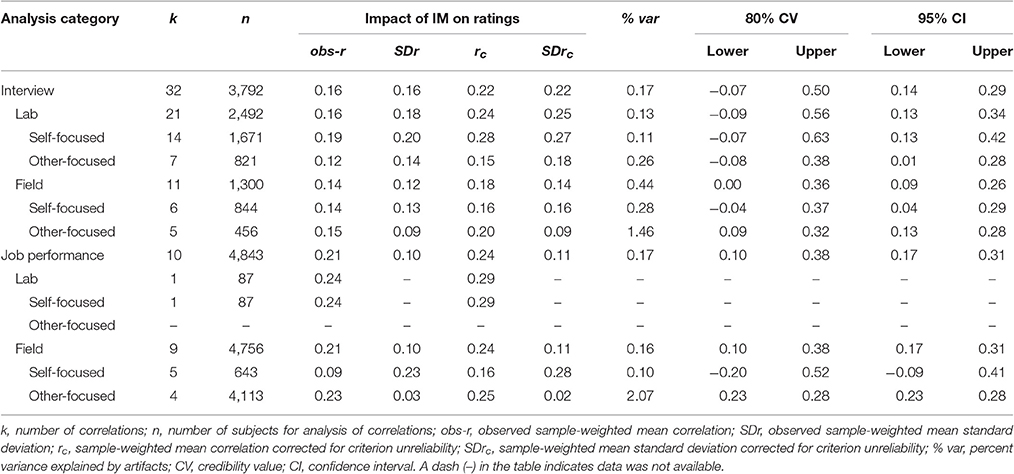

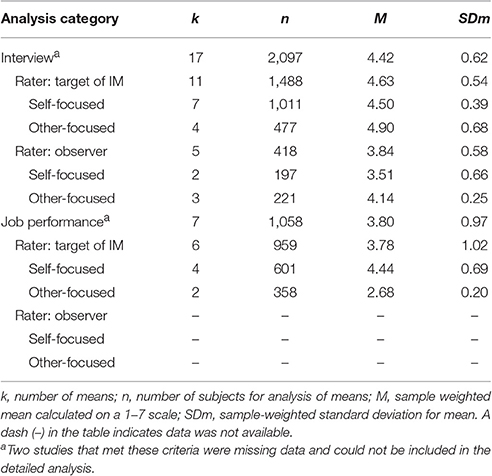

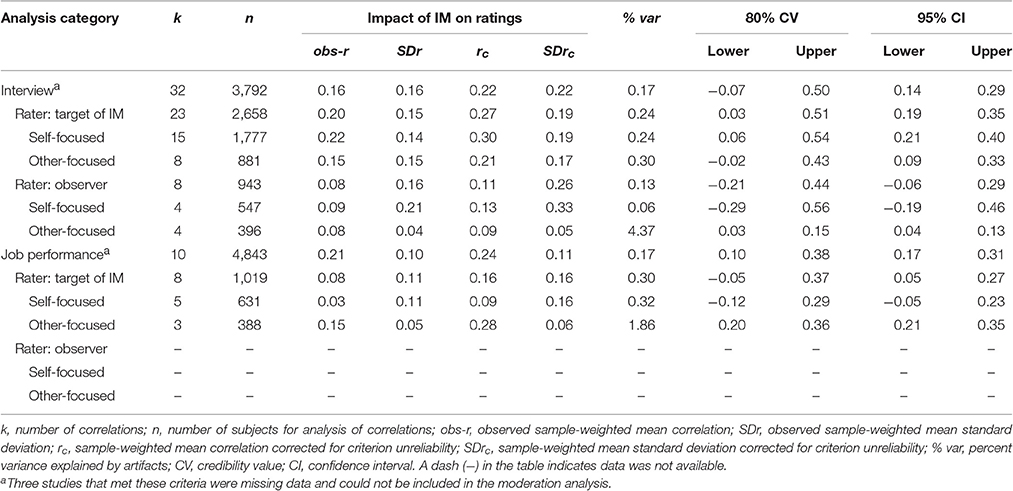

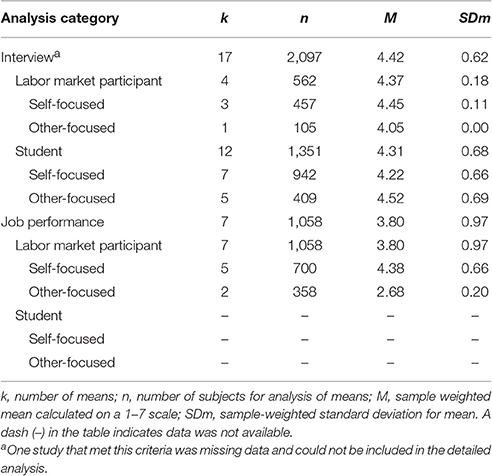

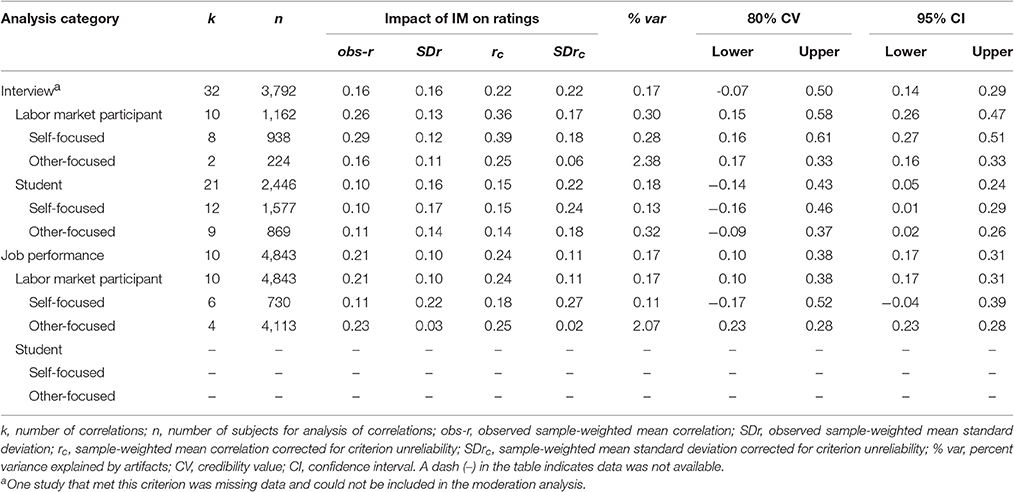

Impression management (IM) is pervasive in interview and job performance settings. We meta-analytically examine IM by self- and other-focused tactics to establish base rates of tactic usage, to understand the impact of tactics on interview and job performance ratings, and to examine the moderating effects of research design. Our results suggest IM is used more frequently in the interview rather than job performance settings. Self-focused tactics are more effective in the interview rather than in job performance settings, and other-focused tactics are more effective in job performance settings rather than in the interview. We explore several research design moderators including research fidelity, rater, and participants. IM has a somewhat stronger impact on interview ratings in lab settings than field settings. IM also has a stronger impact on interview ratings when the target of IM is also the rater of performance than when the rater of performance is an observer. Finally, labor market participants use IM more frequently and more effectively than students in interview settings. Our research has implications for understanding how different IM tactics function in interview and job performance settings and the effects of research design on IM frequency and impact.

Introduction

Impression management (IM) is ubiquitous throughout the interview and during employment. Candidates and employees strive to put their best foot forward to impress employers (e.g., Barrick et al., 2009 ). IM is defined as conscious or unconscious, deceptive or authentic, goal directed behavior. Individuals behave or display props in an attempt to control the impressions others form of them in social interactions (e.g., Schlenker, 1980 ; Gardner and Martinko, 1988 ; Leary and Kowalski, 1990 ; Bozeman and Kacmar, 1997 ; Bolino et al., 2008 , 2016 ). Researchers are examining a variety of experimental designs. However, single studies cannot assess the full magnitude of the relationship between IM tactics and ratings. Thus, the current paper positions a meta-analytical investigation of IM on interview and job performance ratings.

There are a few meta-analyses on IM and interview and performance outcomes ( Higgins et al., 2003 ; Barrick et al., 2009 ; Levashina et al., 2014 ), but these studies each approach the IM and rating relationship from a specific lens leaving a gap in our overall understanding of IM. The most recent study by Levashina et al. (2014) examines these relationships in the context of the structured employment interview. They find self-promotion ( r = 0.26) and other-focused ( r = 0.13) tactics both impact structured interview ratings ( Levashina et al., 2014 ). Higgins et al. (2003) analyze IM tactics through the lens of influence tactics and in many cases the dependent variable reflects a work outcome measure that includes combined interview ratings, performance ratings, and extrinsic measures of success. They find ingratiation has a stronger impact on ratings in lab studies ( r = 0.33) than in field studies ( r = 0.21) ( Higgins et al., 2003 ). Barrick et al. (2009) meta-analytically examine self-presentation tactics of appearance, IM, and nonverbal and verbal behavior and the relationship with interview and performance outcomes. They find IM more strongly impacts interview ratings ( r = 0.47) than job performance ( r = 0.15) ratings. They also conclude self-presentation has a comparable impact on ratings in both the lab and the field. Yet, the impact of IM on ratings is slightly higher for field studies ( r = 0.36) than lab studies ( r = 0.30) and the impact of nonverbal and verbal behavior is higher for lab studies ( r = 0.41) than field studies ( r = 0.32) ( Barrick et al., 2009 ). Each of these studies provide important information to advance the field forward, but the proliferation of IM research using various research design techniques necessitates an updated meta-analysis. The study herein establishes a base rate of IM in interview and job performance settings, explores the impact of self- and other-focused tactics on ratings, and examines research design factors that moderate the relationship between IM and interview and job performance outcomes.

Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

IM is a social influence process involving interactions between an actor, target, and environment ( Goffman, 1959 ). Social influence theory suggests every social interaction involves one party trying to influence the other ( Levy et al., 1998 ). Such motives are particularly invoked during situations in which an individual has the opportunity to develop an identity and obtain social and material outcomes. Social and material outcomes include obtaining a job in the case of an interview or obtaining a raise in the case of performance appraisal ( Leary and Kowalski, 1990 ).

IM is most commonly categorized into self-focused (e.g., self-promotion) and other-focused (e.g., ingratiation) tactics. Self-focused tactics involve the applicant trying to promote perceptions of competence ( Ellis et al., 2002 ). Interviewers form perceptions of the candidate during the interview and make attributions of competence. Self-focused tactics positively influence perceptions because the tactics limit the cognitive effort raters must go through to assess competence and instead directly provide attributional evidence for the individual's competence.

Hypothesis 1a: Self-focused tactics will be positively related to interview ratings.

Hypothesis 1b: Self-focused tactics will be positively related to job performance ratings.

Other-focused tactics are often used to elicit attraction, interpersonal liking, or perceptions of similarity ( Ellis et al., 2002 ; Kristof-Brown et al., 2002 ), which are important influences on rating outcomes ( Wayne et al., 1997 ).

Hypothesis 2a: Other-focused tactics will be positively related to interviewer ratings.

Hypothesis 2b: Other-focused tactics will be positively related to job performance ratings.

Interviews and job performance present unique situations for IM to occur. Interviews are shorter in nature and require less time for an individual to keep up impressions compared to ratings over a longer period of job performance. Also, asymmetric information during an interview allows candidates to engage in substantial IM because the interviewer does not have prior experience or knowledge of the candidate other than what is presented during the interview and in other selection measures (e.g., resumes, personality tests, etc.). However, supervisors have access to the candidate's history of behavior and can base ratings on job performance throughout the period rather than short term IM tactics. Further, interviews typically involve engaging with strangers, and job performance typically involves engaging with familiar people.

We posit that these situational differences between interviews and job performance lead to different impacts for self-promotion and ingratiation on interview and job performance ratings. Individuals are more prone to self-enhancement with strangers ( Tice et al., 1995 ), and interviews typically take place between strangers rather than familiar others. IM as a goal directed behavior is desirable when it is beneficial to the actor and viewed as believable by the target ( Schlenker, 2011 ). Self-focused tactics are beneficial in creating images of competence and believable if the interviewer is only relying on other selection measures and the current interview. Yet, these same self-focused tactics are not as believable or beneficial in generating positive job performance ratings. Supervisors are familiar with their employee's level of competence after exposure to performance over time, so self-promotion claims promoting competence are less beneficial and may even be unbelievable if such claims differ from the supervisor's own perceptions. Further, people generally become more modest over time as they get to know others, so the use of repeated self-promotive behaviors risks arrogance and can potentially damage relationships causing dislike ( Schlenker, 2011 ). Prior research suggests self-promotion strategies have a negligible effect on supervisor liking ( Wayne and Ferris, 1990 ) and in some cases a negative effect on supervisor liking, a precursor to career success ( Judge and Bretz, 1994 ). On the other hand, ingratiatory tactics are suggested as more situationally appropriate in job performance settings than self-promotion tactics ( Ferris et al., 1994 ). Prior research suggests other-focused tactics increase manager liking of subordinate and perceptions of similarity to the subordinate leading to increased performance ratings ( Wayne et al., 1997 ). Researchers examining the effects of self-focused vs. other-focused tactics on interviews and job performance find other-focused tactics to have a greater impact on ratings during performance appraisals than during interviews ( Kacmar and Carlson, 1999 ). In conclusion, we posit self-focused IM will more strongly impact interview rather than performance ratings. We also posit other-focused IM will more strongly impact performance ratings than interview ratings.

Hypothesis 3a: Self-focused tactics will be more strongly related to interview ratings than job performance ratings.

Hypothesis 3b: Other-focused tactics will be more strongly related to job performance ratings than to interview ratings.

Research Design Moderators

We expect several important moderators related to research design to influence the relationship between IM and ratings. These moderators include fidelity of the research setting, whether the target of IM or an observer rates performance, and whether the participants are current labor market participants or students.

Researchers offer different opinions on the validity of experimental lab studies compared to high fidelity employment situations. Lab studies have similar levels of external validity to field studies if participants are placed in authentic situations that ensure psychological realism ( Colquitt, 2008 ). Anderson et al. (1999) analyze meta-analyses of psychological research conducted in the lab vs. the field to determine the similarity between lab and field effect sizes. They correlate the effect sizes of the lab and field research for the same constructs and find a 0.73 correlation between effect sizes ( Anderson et al., 1999 ). This relatively strong correlation is evidence of similar generalizability for lab and field studies in psychological research ( Colquitt, 2008 ). However, the nature of the relationship between lab and field studies varies across particular literatures ( Colquitt, 2008 ), which is the case for employment research.

Employment interview researchers often call into question the external validity of experimental lab studies compared to field studies, particularly due to the high-stakes nature of employment interviews and consequences of the rating ( Jelf, 1999 ; Posthuma et al., 2002 ). The resulting experimental research on the impact of IM in lab and field studies has varying results. Higgins et al. (2003) find ingratiation has a higher impact on interview and job performance assessments in the lab rather than in the field. Barrick et al. (2009) find IM has a slightly higher impact on interview ratings in the field than in the lab, though they deem this difference insignificant. Barrick et al. (2009) also find verbal and non-verbal behavior has a higher impact in the lab than in the field. Despite these differing results, we expect IM has a higher impact on ratings in the lab rather than in the field based on the difference in accountability between lab and field settings.