International Institute for Capacity Building in Africa

United Republic of Tanzania (Mainland and Zanzibar): Education Country Brief

This brief provides data and references to the literature on issues that matter for education in Tanzania. It is part of a series that provides a brief introduction to the state of education systems in Africa. The work was prepared for country pages on IICBA’s website and a digital repository of resources at the country, sub-regional, and continental level. The brief series also informs work conducted in the context of (i) the European Union’s Africa Regional Teachers’ Initiative and (ii) the KIX (Knowledge and Innovation eXchange) Africa 19 Hub for anglophone countries that promotes the use of evidence for policy making and benefits from funding from the Global Partnership for Education and Canada’s International Development Research Center. This brief and its associated webpage are meant to be updated as new information becomes available, at least on a yearly basis.

Key resources: This brief provides the following resources:

- Educational outcomes: Estimates are provided for learning poverty (the share of 10-year-old children not able to read and understand a simple text), educational attainment and/or enrollment rates at various levels of education, the components of the human capital index, and human capital wealth as a share of national wealth.

- Selected literature: Links are provided to selected publications at the global, regional, and country levels with a focus on six themes: (i) learning assessment systems; (ii) early childhood education; (iii) teaching and learning; (iv) the data challenge; (v) gender equality; and (vi) equity and inclusion.

- Country policies: Links are provided to key institutions (including Ministries) managing the education system, selected policy and planning documents, and websites that aim to provide comparative data on policies across countries.

- Knowledge repositories and other resources: Links are provided to a dozen digital repositories that collate publications and resources on education issues in Africa.

- Data: Links are provided to data sources that can help inform education policy.

This country brief provides a brief introduction to selected issues and research relevant to Tanzania’s education system and links to resources that may be useful to official of Ministries of Education and other education stakeholders. A special focus is placed on thematic areas from the KIX (Knowledge and Innovation eXchange) initiative for which UNESCO IICBA manages the Secretariat of the Africa KIX 19 Hub. Together with the associated webpages on UNESCO IICBA’s website, the brief is to be updated as new information becomes available, typically every year. The brief starts with a review of basic data on educational outcomes including learning poverty, educational attainment, and the human capital index. The focus then shifts to information related to the thematic areas of focus of the KIX Africa 19 Hub, namely: (i) learning assessment (ii) early childhood education; (iii) teaching & learning (iv) data challenge; (v) gender equality; and (vi) equity and inclusion. The brief also includes links to country documents and processes as well as a range of other resources and websites.

Educational Outcomes and Human Capital

Tanzania , like many other African countries, is facing a learning crisis. In sub-Saharan Africa, learning poverty, defined as the share of children unable to read and understand an age-appropriate text by age 10, is estimated at 89 percent by the World Bank, UNESCO, and other organizations. While specific country estimates are not available for Tanzania, the World Bank Capital Index suggests concerning developments. According to their data, students in Tanzania score 388 on a harmonized test score scale where 625 represents advanced attainment and 300 represents minimum attainment. This benchmark corresponds to the advanced achievement standard set by the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study. It is imperative to improve the quality of the education provided in schools.

Schooling does not imply learning, but lack of learning increases the likelihood of dropping out of school. According to the World Bank and UNESCO Institute of Statistics, the primary school completion rate was at 66 percent in 2020 for boys and 72 percent for girls. In the same year, lower secondary completion was at 32% for men and 35% for women. Gross enrollment in tertiary education was at 9 percent for men in 2020 versus 7 percent for women.

The Human Capital Index for Tanzania also provides other useful statistics based on five other variables: (i) the probability that a child will survive past age five (95 percent); (ii) the years of schooling that a child is expected to complete by age 18 (7.2 years); (iii) the learning-adjusted years of schooling that a child is expected to complete, a measure combining the years of schooling and average harmonized test scores (4.5 years); (iv) the adult survival rate (78 percent of 15-year olds surviving until age 60); and finally (v) the probability that a child will not be stunted in early childhood (68 percent). Based on these five variables and the harmonized test score , the expected productivity in adulthood of a child is estimated in comparison to full productivity that could be expected with full education and health. The estimate is that a child born in Tanzania today will reach only 39 percent of its potential. This is lower than the average for sub-Saharan Africa region and lower middle-income countries.

One last statistic may help make the case for the importance of investing in education for the country’s development. A country’s wealth mainly consists of three types of capital: (1) Produced capital comes from investments in assets such as factories, equipment, or infrastructure; (2) Natural capital consists of assets such as agricultural land and both renewable and nonrenewable natural resources; (3) Human capital is measured as the present value of the future earnings of the labor force, which in turn depends on the level of educational attainment of the labor force. The latest estimates from the World Bank suggest that human capital wealth in Tanzania accounts for 61 percent of national wealth.

Selected Literature

Supporting countries in using evidence for policymaking is an objective shared by many organizations and initiatives. Under the KIX initiative for which UNESCO IICBA manages the KIX Africa 19 Hub and collaborates with KIX Africa 21, the focus is on six themes: (i) learning assessment systems (ii) early childhood education; (iii) teaching and learning (iv) the data challenge; (v) gender equality; and (vi) equity and inclusion. For each topic, a link is provided to the GPE-KIX Discussion paper written at the start of the initiative in 2019 and additional publications that could be useful for policy. By necessity, to keep this brief short, only a few resources can be mentioned, but additional resources can be accessed through digital repositories listed below. A brief note on UNESCO IICBA research is also provided.

Learning Assessment Systems [GPE-KIX Discussion Paper] . Learning assessment tools and systems are essential to gauge and improve learning outcomes for students. A primer on large scale assessments from the World Bank provides guidance on such assessments, as does a review of learning assessments in Africa from UNESCO IIEP. Among regional assessments, PASEC (Programme for the Analysis of Education Systems) for francophone countries in West and Central Arica and SEACMEQ (Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality) for anglophone countries in East and Southern Africa are the best known. These instruments target primary schools. Other tools that focus and assess the learning outcomes of young learners include the Early Grade Reading and Mathematics Assessments (EGRA/EGMA). Supported and funded primarily by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), these assessments are administered by different agencies such as the World Bank, RTI International and others across the continent. The West African Examinations Council also provides guidance on examinations and certificate accreditation in Anglophone countries of West Africa. Also interesting is PISA for development which is being piloted in secondary schools in a few African countries.

Tanzania and Zanzibar participate in regional and international assessments such as SEACMEQ . Within Tanzania, the National Examination Council of Tanzania operating under the Ministry of Education Science and Technology (MoEST) administers national exams, including the Primary School Leaving Examination, the Certificate of Secondary Education Examination (CSEE) at the end of lower secondary education (Form 4), the Advanced CSEE at the end of upper secondary, national exams (Standard 4 in primary and Form 2 in lower secondary education)), as well as the exams for teacher training.

One comprehensive study, Cilliers et al. (2020) , evaluated a low-stakes accountability program in Tanzania called ‘Big Results Now in Education’ (BRN), which published both nationwide and within-district school rankings. The study found showed that the BRN program had a positive impact on the educational achievements of schools in the bottom two deciles of their respective districts. The study was carried out using a diverse range of data sources, including the Tanzania Primary School Leaving Examination, administrative data from the Education Management Information System (EMIS), and micro-data from the World Bank's Service Delivery Indicators (SDI) survey in Tanzania.

Furthermore, A 2019 survey from The Teaching and Learning: Educators' Network for Transformation (TALENT) indicated that Tanzania has a national policy on assessment underscoring the country’s commitment to using a structured approach to assessing educational outcomes. In the same year, the World Bank analyzed the learning outcomes of students in Tanzania , utilizing data collected from Service Delivery Indicators (SDI) and data from Systems Approach for Better Education Results (SABER) Service Delivery.

Improving Teaching and Learning [GPE-KIX Discussion Paper] . How teachers and students interact and engage is key to improve learning outcomes. Cost-effective approaches pr ‘smart buys’ to improve learning in low-income countries are discussed in a World Bank report . Teaching is paramount, and therefore so are teacher policies to ensure that successful teachers make for successful students. Standards for the teaching profession were proposed by Education International and UNESCO with regional standards available from the Africa Union Commission, including a framework for standards and competencies.

Tanzania uses a 1-7-4-2-3+ structure compromising early childhood education, primary education (encompassing Standards I to VII), Secondary Ordinary-Level education, Secondary Advanced-Level education, and a minimum of three years of post-secondary education.

As of 2022, Tanzania is in the process of major reforms of the Education Sector, including the review of the Education and Training Policy (2014) and Curriculum for Basic Education. The revision aims primarily to upgrade curricula to align with global developments in technology innovation, as well as to ensure a strong focus on imparting job-relevant skills.

Key relevant bodies responsible for these reforms include The Tanzanian Institute of Education (TIE), which is responsible for curriculum development and, since 2014, textbook development and production. To maintain the quality of education, School Quality Control Offices are established in all 26 regions of mainland Tanzania. There are two standardized and official forms of performance evaluation for teachers, which are the individual Open Performance Review and Assessment System (OPRAS, every six months) and the school-level School Quality Assurance visit.

The World Bank’s report ‘ Tanzania Education Sector Institutional and Governance Assessment’ (2021) examines the drivers of efficient and effective basic education service delivery and provides comprehensive recommendations. In addition, a report by the National Audit Office, Controller and Auditor General’s on ‘ Management of The Provision off Capacity Building to In-Service Teachers’ (2020) reveals that only 18% of primary and 19% of secondary teachers received an in-service training between 2015/16 and 2018/19, and primary teachers who did receive training were mainly in the early grades. Furthermore, continuous professional development is mainly centrally organized and dependent on donor funds.

Lastly, Mbiti et al. (2019) evaluate the impact of providing schools with (i) unconditional grants, (ii) teacher incentives based on student performance, and (iii) both of the above in Tanzania, based on the data from 350 public primary schools across 10 districts in mainland Tanzania.

Strengthening Early Childhood Care and Education [ GPE-KIX Discussion Paper ]. Experiences children undergo in early childhood can affect their entire life. Nurturing care is essential. Essential interventions in early childhood include pre-primary education. Yet less than half of young children in Africa benefit from pre-primary education according to the Global Education Monitoring report 2021 . The Office of Research at UNICEF maintains a webpage with useful links to organizations working on child-related themes organized by subject, including early childhood.

Tanzania’s efforts to enhance Early Childhood Development (ECD) are exemplified by the establishment of the first National Multisectoral ECD Programme for the financial year 2021/2022 to 2025/2026. The program is led by the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children.

For a comprehensive insight into the ECE landscape in Tanzania, the African Early Childhood Network (AfECN) offers the Tanzania: ECD Profile which is based on data from UNICEF’s The State of the World's Children 2023 ).

In Zanzibar, a 2023 UNESCO report on ECE in the continent provides an overview of how Islamic centers of learnings, such as Madrasa’s have played an important role in early learning. A Madrasa preschool programme demonstrated that community-based preschools, supported by NGOs, can be effectively managed, and sustained. The report cites evaluations that reveal that Madrasa preschools compare favorably with other high-quality preschools in terms of classroom practices, learning environments, and children's performance outcomes.

For an in-depth exploration of the factors that facilitate or impede efforts to make early childhood education a political priority in four countries, including Tanzania, see the World Bank’s ‘Political Prioritization of Early Childhood Education in Low- and Middle-Income Countries ’ (2021). Furthermore, the World Bank Early Childhood Stimulation in Tanzania: Findings from a Pilot Study in Katavi Region (2018) investigates the links between early stimulation practices and development of children 0-3 years of age in the Katavi region. Lastly, Mendenhall et al. (2021) explore promising innovations for Teacher Professional Development that can support the uptake of play-based learning in three countries, including Tanzania. Basic data on early childhood development is available from a nurturing care profile .

Achieving Gender Equality In and Through Education [GPE-KIX Discussion Paper] . The cost of gender inequality is massive, as is the cost of not educating girls , including in Africa . When girls lack education, this affects their earnings in adulthood, the number of children they will have and their health, as well as their agency, among others. When girls are not in school, they are also at higher risk of child marriage, with again high costs for them, their children, and society. In Africa, the African Union’s International Centre for the Education of Girls and Women in Africa supports member states on girls’ education.

Alongside the MoEST, the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children is responsible for ensuring the achievement of gender equality in and through education in Tanzania. In this context, a National Accelerated Action and Investment Agenda for Adolescent Health and Wellbeing 2021/22-2024/25 was developed to assess the gendered implications in the education sector and respective commitments.

In 2021, the Tanzanian government announced an expansion of formal education access for girls, particularly pregnant students, and young mothers in government schools. To gain insight into recent progress, the World Bank’s restructuring paper for the Tanzania Secondary Education Quality Improvement Project (SEQUIP) (2022) provides an update on progress and the current situation of gender equality in the country.

Other efforts to empower girls in Tanzania have included the, “Empowerment and Livelihood for Adolescents (ELA)” program by BRAC, evaluated by Buehren et al. (2017) . This initiative included elements such as safe-space clubs, life skills training, and livelihood training, contributing to the broader goal of advancing gender equality in education.

UNICEF’s report “ Menstrual Health and Hygiene (MHH) among school girls in Tanzania” (2021) presents information about the MHH situation among schoolgirls in Tanzania. Global Education Monitoring Report’s “ Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) in Tanzania ” provides an overview of CSE in the country.

A 2022 UNICEF report on Child Marriage in Eastern and Southern Africa reinforces the significance of education as a tool for preventing child marriage. It estimates that 3 in 10 young women were first married or in union before the age of 18. 65% of women aged 20 to 24 years who were first married or in union before age 18 had no education as compared to 9% who had at least a secondary education.

Data Management Systems Strengthening [GPEKIX Discussion Paper] . Education management information systems (EMIS) are key for management. They can also support evidence-based policymaking. In Africa, the African Union’s Institute of Education for Development supports member states on EMIS. In addition to EMIS data, other data sources including household surveys, school surveys, student assessments, and impact evaluations of pilot interventions are essential to inform policy.

In the Tanzanian education sector, Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) activities are jointly supervised by MoEST and the President’s Office – Regional Administration and Local Government (PO-RALG). A critical part of M&E is the Education Sector Management Information System (ESMIS). It was introduced in 2007, harmonizing three subsystems: (i) the Basic Education Management Information System (BEMIS) for (school-level) annual school census (ASC) data; (ii) the Vocational Education and Training Management Information System (VET-MIS) for annual census data from Vocational Training Centers (VTCs) and Folk Development Colleges (FDCs); and (iii) the Higher and Technical Education Management Information System (HET-MIS) for annual census data from technical institutes, colleges, and universities.

To provide valuable demographic data that informs educational planning, the National Bureau of Statistics conducts a population and housing census every 10 years since 1967. The most recent census in 2022 indicates that the population increased by 37% between 2012 and 2022, making the country’s population growth the third highest in the world. However, data on teachers requires further improvement. The World Bank’s report “Tanzania Education Sector Institutional and Governance Assessment” (2021) highlights this challenge.

The Education Sector Development Plan (ESDP) Appraisal Report (2018) , recommends special attention to guarantee suitable coordination between the various ESMIS. The report also suggests rationalizing M&E framework indicators, which currently include over 100 indicators, to streamline the data collection process and enhance its effectiveness. According to a joint 2020 UNESCO and Global Partnership for Education report , Tanzania utilizes StatEduc 2.0 as its EMIS platform.

Equity and Inclusion/Leaving No One Behind [GPEKIX Discussion Paper] . Equity and inclusion are major challenges for education systems. Gender, disability, ethnicity, indigenous status, poverty, displacement, and many other factors may all lead some children to lack access to education. In Africa especially, gaps in educational outcomes between groups may be large, as illustrated in the case of disability . Equity must be at the center of education policy on the continent. The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) are Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) are two major international frameworks related to disability-inclusive education exist.

In 2014, Tanzania launched a fee-free education policy for pre-primary and primary education. This policy marked a significant step in enhancing access to education, especially for the most vulnerable populations.

Tanzania ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) in 1991 and ratified the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in 20 09. To ensure the effective implementation of these conventions, Tanzania enacted the Persons with Disabilities Act in both 2010 and 2020. These legislative measures emphasize the importance of special and inclusive education in the country.

A key policy framework in inclusive education is the National Strategy for Inclusive Education 2018-2021 . This strategy prioritizes several vulnerable groups, including over-aged learners with gap years in their education; learners who live more than seven kilometers from school; children with disabilities; children from nomadic communities; orphans; refugees and learners experiencing other emergencies; children living in extreme poverty and teenage girls.

To evaluate progress and impact in this area, a 2020 report by ActionAid, Education International and Light for the World provides a country case study on Tanzania. Furthermore, Plan International (2022) , in Tanzania, demonstrates interventions that support Burundian refugee girls’ education (enrollment and retention in particular) through Menstrual Hygiene Management training and sanitary items.

Note on UNESCO IICBA Research. IICBA recently launched a new program of applied research on teacher and education issues in Africa. A total of 200 publications have been completed from January to September 2023, including studies, discussion papers, training guides, reports, knowledge briefs, event summaries, and interviews. Several of those publications focus on Tanzania. All publications are available on IICBA’s website .

Country Policies

Information on Tanzania’s education system and policies is available on the website of the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology which covers basic and higher education as well as technical education and vocational training (TVET). The Education Sector Development Plan (2016/17-2020/21) that covers Tanzania Mainland is the most recent flagship policy covering the sector in Tanzania Mainland while the Zanzibar Education Development Plan II 2017/2018-2021/2022 is the flagship education policy for education in Zanzibar. The Education Sector Development Plan (ESDP) Appraisal Report (2018) highlights challenges and recommendations within the education sector, including inter and intra-organizational implementation challenges and duplications.

Tanzania does have a teaching service commission which is enabled by the Teachers’ Service Commission of Act of 2015 .

A few organizations aim to capture education policies on specific themes across countries, including Tanzania. UNESCO’s Profiles Enhancing Education Reviews (PEER) covering the themes of the Global Education Monitoring reports, including: inclusion in education (2020 Report), non-state actors in education (2021/22 Report), technology in education (2023 Report) and leadership in education (2024/25 Report, forthcoming). PEER also covers additional topics on key SDG 4 issues, including financing for equity , climate change communication and education , and comprehensive sexuality education .

Knowledge Repositories

Only a few links to the literature on education by theme for Tanzania, Africa, and globally were provided earlier to keep the brief short, but repositories of digital resources facilitate access to the literature. A few of those repositories are listed below by alphabetical order:

- 3ie Development Evidence Portal (DEP): DEP is a repository of rigorous evidence on what works in international development, including in the area of education .

- AERD : The African Education Research Database hosted by the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge collates research by African scholars on education.

- African Development Bank: The Bank has publications that cover a range of topics, including education. It also hosts ADEA which also has selected publications .

- Global Partnership for Education: GPE is one of the largest funders for education in Africa. It collaborates with Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC) to build and mobilize evidence on education through the Global Partnership for Education Knowledge and Innovation Exchange (GPE KIX), which has a Library of research outputs.

- J-PAL: The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab maintains a database of impact evaluations and policy publications, quite a few of which are about education.

- RePEc: Research Papers in Economics is a large archive of research on economics, including the economics of education. It can be searched through IDEAS .

- Teacher Task Force (TTF): The TTF is collaborative across many organizations hosted by UNESCO. It maintains a Knowledge Hub with resources on teacher policies.

- UNESCO HQ: UNESCO is the lead agency in the UN systems on education. Its Digital Library includes UNESCO Open Access which includes most UNESCO publications.

- UNESCO GEM : UNESCO publishes annually a Global Education Monitoring Report on a different theme each year with associated resources and background papers.

- UNESCO IICBA: IICBA is a Category 1 Institute at UNESCO. It conducts research on education in Africa with several publication series and maintains a digital repository.

- UNICEF: Publications can be found under Reports , the Office of Global Insight and Policy , and the Office of Research . Also of interest is the Data Must Speak initiative.

- World Bank: The Open Knowledge Repository provides access to the Bank’s research. It includes a section on Africa with country pages including for Tanzania.

Many organizations maintain websites that include country pages with useful information. Examples include the GPE Tanzania Country Page ; World Bank Tanzania Country Page ; UNESCO IIEP Country Page . Many organizations also maintain blogs on education issues, often with stories on Africa. Examples include Education for All (Global Partnership for Education), Education for Global Development (World Bank), Education Plus Development (Brookings Institutions), and World Education Blog (UNESCO). Beyond blogs focusing on education, blogs on Africa more generally may also provide useful resources. This includes Africa Can End Poverty and Nasikiliza (the World Bank’s two blogs for sub-Saharan Africa ) and Arab Voices (the Bank’s blog for the Middle East and North Africa).

It is often useful to download data for Tanzania and other countries from multi-country databases. The largest database on development, including education data, is the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI). The World Bank also maintain the Education Statistics (EdStats) database. Both World Bank databases rely in part for education on data from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics . UNESCO also maintains the Global Education Observatory and the World Inequality Database in Education (WIDE), as well as a wide range of other databases . Specific estimates are occasionally maintained by other agencies. For example, UNICEF provides data on out-of-school rates, adjusted net attendance rates, completion rates, foundational learning skills, information communication technology skills, youth and adult literacy rates, and school-age digital connectivity. Another useful reference is StatCompiler which provides data at various levels of aggregation from Demographic and Health Surveys across countries and over time, including Tanzania. For comparison purposes, data from the OECD for member and partner countries (including South Africa) can be useful.

References are available through the links provided in this brief.

Transforming Tanzania's Education Landscape

On November 24, 2023, a significant meeting transpired between the Heads of Agencies and Cooperations of the Education Development Partners Group (EdDPG) in Tanzania Mainland and the esteemed Hon. Prof. Adolf Mkenda, Minister for Education, Science and Technology, alongside high-level officials from the Ministry. The primary focus of this gathering was to address pivotal issues concerning the ongoing reform of the Education Sector in Tanzania Mainland. Since September 2022 UNESCO assumed the chairmanship of the EdDPG, a group of multilateral and bilateral agencies providing support to the Education Sector in Tanzania Mainland and Zanzibar. Established in 2001, the primary objective of the EdDPG is to facilitate coordinated interventions and policy dialogue among development partners, aiming to support the Tanzania Education Sector in achieving learning outcomes aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals.

During his address, Prof. Mkenda conveyed his deep appreciation to the Heads of Agencies and Cooperation for their proactive involvement in education reforms, underscoring his unwavering commitment to enhancing the education landscape in Tanzania. He approved the 2023 version of the National 2014 Education and Training Policy, providing insights into the new education structure and curriculum. Prof. Mkenda highlighted the critical challenge of insufficient teachers, emphasizing the need for collaborative efforts to overcome this hurdle in implementing the approved policy. He called for sustained cooperation to ensure increased access to and quality education, leaving no one behind in pursuing educational excellence. UNESCO, UNICEF, SIDA, UNHCR, World Bank, IMF, Belgium Embassy, USAID, KOICA, the Swiss Agency for Development, FCD, Aga Khan Foundation, DVV International, and other Education Development Partners Group members attended the meeting.

On the other hand, the WFP Country Representative in Tanzania, Ms. Sarah Gordon-Gibson, representing the UN Resident Coordinator, emphasized that the UN family in Tanzania stands in solidarity with the Government of the United Republic of Tanzania. This shared commitment is rooted in the United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (UNSDCF) 2022-2027, reflecting a joint dedication to transforming the Education Sector.

The UN family in Tanzania stands in solidarity with the Government of the United Republic of Tanzania in our shared commitment to transforming the education sector. This commitment is firmly rooted in the UNSDCF 2022-2027, launched by Vice President Phillip Mpango last year, that outlines our collective response to contribute more efficiently and effectively to achieve the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in Tanzania.

Mr. Michel Toto, Head of Office and Country Representative of UNESCO, and the Chair of the EdDPG, acknowledged the Government's positive strides in budget allocation for the education sector over the past few years on behalf of the EdDPG. He reiterated the need to increase the education budget from 18% to the recommended rate of 20% to accelerate improvements in education sector outcomes. Mr. Toto reaffirmed the Education Development Partners Group’s commitment to support Tanzania’s Education Sector reform and development. Furthermore, he highlighted UNESCO's available support through its specialized institutes including the International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP), the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), the International Bureau of Education (IBE), and the International Institute for Capacity Building in Africa (IICBA).

We commend the Government's efforts in improving and increasing access to the quality of education at all levels. Globally, we are halfway through implementing Sustainable Development Goal 4 on Education, which seeks to ensure sustainable, inclusive, and equitable quality education, promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all. This goal is at the core of our collective mission.

Participants in group photo during the meeting with the Honourable Minister of Education, Science and Technology

Related items

- Priority Africa

- Country page: United Republic of Tanzania

- Region: Africa

- UNESCO Office in Dar es Salaam

- SDG: SDG 4 - Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

- See more add

This article is related to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals .

Other recent news

Advertisement

Exploring Mathematics Teaching Approaches in Tanzanian Higher Education Institutions: Lecturers’ Perspectives

- Published: 01 February 2023

- Volume 9 , pages 269–294, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Mzomwe Yahya Mazana ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7350-7011 1 , 3 ,

- Calkin Suero Montero ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5686-7285 2 &

- Lembris Laayuni Njotto 3

331 Accesses

Explore all metrics

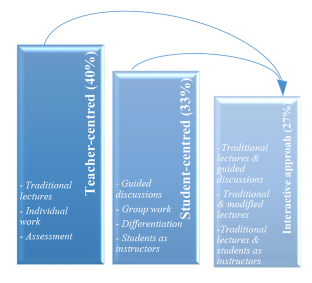

The success of the teaching - learning process in terms of learning outcomes is determined by several factors, primarily the lecturer’s teaching approach used. Despite the importance of the teaching approach, little is known concerning the teaching approaches used by mathematics lecturers in Tanzanian higher education institutions. This study explores the lecturers’ perspectives regarding the teaching approaches they normally use in teaching mathematics, and what motivates their choices, within an emerging economy context. Data are collected through semi-structured interviews with 15 lecturers. Data are analysed using content analysis and descriptive statistics. The findings reveal that lecturers are more likely to choose teacher-centred approaches and that assurance of the right content , content coverage and time-saving aspects are associated with choosing this approach. These findings provide insights into the current state in mathematics classroom regarding teaching approaches, and the motivation behind lecturers’ teaching approach choices, complementing current findings in the literature. We categorise the teaching approaches for mathematics teaching – learning by describing the interactions between the different actors in the classroom (teachers, students, and content) in order to inform and influence successful mathematics teaching practices in emerging economies such as Tanzania.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of the course teaching and learning of mathematics on preservice grades 7 and 8 mathematics teachers in singapore.

Innovative and Powerful Pedagogical Practices in Mathematics Education

Does school teaching experience matter in teaching prospective secondary mathematics teachers? Perspectives of university-based mathematics teacher educators

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Altogether there were 25 full time lecturers of business mathematics subject in these three HEIs.

Abdulwahed, M., Jaworski, B., & Crawford, A. R. (2012). Innovative approaches to teaching mathematics in higher education: a review and critique. Nordic Studies in Mathematics Education , 17 (2), 49–68.

Google Scholar

Adunola, O. (2011). The impact of teachers’ teaching methods on the academic performance of Primary School Pupils in Ijebu-Ode local cut area of Ogun State. Ogun State, Nigeria . Nigeria: Ogun State.

Akiri, E., Tor, H. M., & Dori, Y. J. (2021). Teaching and Assessment Methods: STEM teachers’ perceptions and implementation. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics Science and Technology Education , 17 (6), https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/10882 . Article em1969.

Andrews, P. (2009). Mathematics teachers’ didactic strategies: examining the comparative potential of low inference generic descriptors. Comparative Education Review , 53 (4), 559–581. https://doi.org/10.1086/603583 .

Article Google Scholar

Arora, S., Singhai, M., & Patel, R. (2011). Gender & education determinants of individualism—collectivism: a study of future managers. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations , 47 (2), 321–328. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23070579 .

Beausaert, S. A., Segers, M. S., & Wiltink, D. P. (2013). The influence of teachers’ teaching approaches on students’ learning approaches: the student perspective. Educational Research , 55 (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2013.767022 .

Beck, C. R. (1998). A taxonomy for identifying, classifying, and interrelating teaching strategies. The Journal of General Education , 47 (1), 37–62. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27797363 .

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage publications.

Davis, M. L., Witcraft, S. M., Baird, S. O., & Smits, J. A. (2017). Learning principles in CBT. In The science of cognitive behavioral therapy (pp. 51–76). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803457-6.00003-9

Dawkins, P. C., Oehrtman, M., & Mahavier, W. T. (2019). Professor goals and student experiences in traditional IBL real analysis: a case study. International Journal of Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education , 5 (3), 315–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40753-01 .

Dennehy, E. (2015). Hofstede and learning in higher level education: an empirical study. International Journal of Management in Education , 9 (3), 323–339.

Denscombe, M. (2010). The Good Research Guide: for small-scale social research (4th ed.). McGraw Hill.

Dlamini, G. P. (2016). An Exploration of the Teaching Strategies Used by Mathematical Literacy Teachers: A Case Study of Grade 11 Teachers in UMlazi District.(Masters dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Edgewood) KwaZulu-Nata: University of KwaZulu-Natal, Edgewood. http://hdl.handle.net/10413/13825

Du Plessis, E. (2020). Student teachers’ perceptions, experiences, and challenges regarding learner-centred teaching. South African Journal of Education , 40 (1), https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v40n1a1631 .

Galperin, B. L., & Melyoki, L. L. (2018). Tanzania as an emerging entrepreneurial ecosystem: prospects and challenges. African entrepreneurship (pp. 29–58). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73700-3_3 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Ganyaupfu, E. M. (2013). Teaching methods and students academic performance. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention , 2 (9), 29–35.

Gehrig, B. (2018). Some Challenges to Building STEM Capacity in Emerging Economies: The Case of Namibia. ASEE Annual conference exposition Salt Lake City, Utah: American Society for Engineering education. https://doi.org/10.18260/1-2--30978

Hasanova, N., Abduazizov, B., & Khujakulov, R. (2021). The main differences between teaching approaches, methods, procedures, techniques. Styles And Strategies JournalNX , 7 (02), 371–375.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: the Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture , 2 (1), 2307–0919. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014 .

Ishemo, R. (2021). Progress of the implementation of the learner centred approach in Tanzania. International Journal on Integrated Education , 4 (4), 55–72. https://www.suaire.sua.ac.tz/handle/123456789/4028 .

Jambor, P. Z. (2005). Teaching Methodology in a” Large Power Distance” Classroom: A South Korean Context. Online Submission .

Jaworski, B., & Matthews, J. (2011, February). How we teach mathematics: Discourses on/in university teaching. In Proceedings of the Seventh Congress of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education (pp. 2022–2032). Poland: University of Rzeszów.

Kafyulilo, A. C. (2013). Professional development through teacher collaboration: an approach to enhance teaching and learning in science and Mathematics in Tanzania. Africa Education Review , 10 (4), 671–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2013.853560 .

Kangalawe, R. (2019). Assessment used to measure practical skills in competence-based curriculum in secondary schools in Temeke district, Tanzania [Masters’ dissertation] The catholic university of eastern Africa.

Keiler, L. S. (2018). Teachers’ roles and identities in student-centered classrooms. International journal of STEM Education , 5 (1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0131-6 .

Kyaruzi, F., Strijbos, J. W., Ufer, S., & Brown, G. T. (2018). Teacher AfL perceptions and feedback practices in mathematics education among secondary schools in Tanzania. Studies in Educational Evaluation , 59 , 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.01.004 .

MacVaugh, J., & Norton, M. (2012). Introducing sustainability into business education contexts using active learning. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education , 13 (1), 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676371211190326 .

Mali, A., & Petropoulou, G. (2017). Characterising undergraduate mathematics teaching across settings and countries: an analytical framework. Nordic Studies in Mathematics Education , 22 (4), 23–42. http://ncm.gu.se/nomad-sokresultat-vy?brodtext=22_4_mali .

Mazana, Y. M., Montero, S., C., & Olifage, C. R. (2019). Investigating students’ attitude towards learning mathematics. International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education , 14 (1), 207–231. https://doi.org/10.29333/iejme/3997

Mendes, I. A. (2019). Active methodologies as investigative practices in the mathematics teaching. International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education , 14 (3), 501–512. https://doi.org/10.29333/iejme/5752 .

Mesa, V., Celis, S., & Lande., E. (2014). Teaching approaches of community college mathematics faculty: do they relate to classroom practices? American Educational Research Journal , 51 (1), 117–151. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831213505759 .

Ministry of Education and Vocational Training (MoEVT)(2014). Sera ya elimu na mafunzo[Education training and policy]. Dar es Salaam:MoEVT

Moate, R. M., & Cox, J. A. (2015). Learner-centered pedagogy: considerations for application in a didactic course. Professional Counselor , 5 (3), 379–389. https://doi.org/10.15241/rmm.5.3.379 .

Mohamed, M., & Karuku, S. (2017). Implementing a competency-based curriculum in science education: A Tanzania mainland case study. In The World of Science Education (pp. 101–118). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6351-089-9_7

Mormina, M. (2019). Science,Technology and Innovation as Social Goods for Development: Rethinking Research Capacity Building from Sen’s capabilities Approach. Science And Engineering Ethics , 25 (1), 671–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-018-0037 .

Muganga, L., & Ssenkusu, P. (2019). Teacher-centered vs. Student-Centered: an examination of student teachers’ perceptions about pedagogical practices at Uganda’s Makerere University. Cultural and Pedagogical Inquiry , 11 (2), 16–40. https://doi.org/10.187.

Mulenga, I. M., & Kabombwe, Y. M. (2019). A competency-based curriculum for zambian primary and secondary schools: learning from Theory and some countries around the World. International Journal of Education and Research , 7 (2), 117–130. http://dspace.unza.zm/handle/123456789/6571 .

National Council for Tectinical Education (NACTE) (2007–2020). NTA Competence Level Descriptors . Retrieved August 27 (2020). from The National Council for Technical Education (NACTE): https://www.nacte.go.tz/index.php/curriculum/competence-descriptor/

National Examinations Council of Tanzania (NECTA) (2018). Examination statistics . Dar Es Salaam: National Examination Council of Tanzania.

Ndihokubwayo, K., Uwamahoro, J., & Ndayambaje (2020). Implementation of the competence-based learning in rwandan physics classrooms: first assessment based on the reformed teaching observation protocol. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics Science and Technology Education , 16 (9), em1880. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/8395 .

Ní Ríordáin, M., Coben, D., & Miller-Reilly, B. (2015). What do we know about Mathematics teaching and learning of multilingual adults and why? Does it matter? Adults Learning Mathematics: An International Journal , 10 (1), 8–23. https://hdl.handle.net/10289/11407 .

Olausson, E., Stafström, C., & Svedin, S. (2009). Cultural dimensions in organizations: A study in Tanzania urn:nbn:se:ltu:diva-52294. Retrieved from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:ltu:diva-52294

Owen, J. P. (1958). The role of economics in education for business administration. Southern Economic Journal , 353–361. https://doi.org/10.2307/1055067 .

Paoletti, T., Krupnik, V., Papadopoulos, D., Olsen, J., Fukawa-Connelly, T., & Weber, K. (2018). Teacher questioning and invitations to participate in advanced mathematics lectures. Educational Studies in Mathematics , 98 (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-018-9807-6 .

Päuler-Kuppinger, L., & Jucks, R. (2017). Perspectives on teaching: conceptions of teaching and epistemological beliefs of university academics and students in different domains. Active Learning in Higher Education , 18 (1), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1177.

Pera, A. T. (2015, February 13). Approaches Retrieved August 12, 2021, from Slideshare: https://www.slideshare.net/angelitopera/approaches-54936041

Petropoulou, G., Jaworski, B., Potari, D., & Zachariades, T. (2020). Undergraduate Mathematics teaching in first year lectures: can it be responsive to student learning needs? International Journal of Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education , 6 (3), 347–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40753-020-00111-y .

Phungphol, Y. (2005). Learner-centered teaching approach: a paradigm shift in thai education. ABAC journal , 25 (2), 5–16.

Pritchard, A. (2009). Ways of Learning:learning theories and learning styles in the classroom (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Purity, W. N. (2019). Influence of culture on education in Kenya and Tanzania. Journal of Comparative Studies and International Education (JCSIE) , 1 (1), 73–96.

Ramburuth, P., & Tani, M. (2009). The impact of culture on learning: exploring student perceptions. Multicultural Education & Technology Journal . https://doi.org/10.1108/17504970910984862 .

Reis, R. (2021). Teaching and Learning Theories:Tomorrow’s Teaching and Learning . Retrieved Jully 25, from Stanford University: https://tomprof.stanford.edu/posting/1505

Schmeisser, C., Krauss, S., Bruckmaier, G., Ufer, S., & Blum, W. (2013). Transmissive and Constructivist Beliefs of in-service Mathematics teachers and of beginning University students. Proficiency and Beliefs in Learning and Teaching Mathematics , 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-299-0_5 .

Serin, H. (2018). A comparison of teacher-centered and student-centered approaches in educational settings. International Journal of Social Sciences & Educational Studies , 5 (1), 164–167. https://doi.org/10.23918/ijsses.v5i1p164 .

Sibomana, A. B., Ukobizaba, F., & Nizeyimana, G. (2021). Teachers’ perceptions of their teaching strategies and their influences on students’ academic achievement in national examinations in Burundi: case of schools in Rumonge province. Rwandan Journal of Education , 5 (2), 153–166.

Syed, M., & Nelson, S. C. (2015). Guidelines for establishing reliability when coding narrative data. Emerging Adulthood , 3 (6), 375–387.

Tadesse, A., Eskelä-Haapanen, S., Posti-Ahokas, H., & Lehesvuori, S. (2021). Eritrean teachers’ perceptions of learner-centred interactive pedagogy. Learning Culture and Social Interaction , 28 , 100451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100451 .

Tambwe, M. A. (2017). Challenges facing the implementation of a competency-based education and training (CBET) system in Tanzanian technical institutions. Education Research Journal , 7 (11), 277–283. http://dspace.cbe.ac.tz:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/330 .

Trigwell, K., Prosser, M., & Taylor, P. (1994). Qualitative differences in approaches to teaching first year university science. Higher education , 27 (1), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01383761 .

Umugiraneza, O., Bansilal, S., & North, D. (2017). Exploring teachers’ practices in teaching Mathematics and Statistics in KwaZulu-Natal schools. South African Journal of Education , 37 (2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n2a1306 .

URT. (2011). Tanzania Education Sector Analysisi: Beyond Primary Education, the Quest for balanced and efficient policy choices for Human Development and Economic Growth . Dar Es Salaam: URT.

Van der Wal, G. (2015). Exploring teaching strategies to attain high performance in grade eight Mathematics: a case study of Chungcheongbuk Province, South Korea Doctoral dissertation. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss . 2014.v5n23p1106

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Socio-cultural theory. Mind in Society , 6 , 52–58.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Computing, University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu, Finland

Mzomwe Yahya Mazana

School of Educational Sciences and Psychology, University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu, Finland

Calkin Suero Montero

College of Business Education, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Mzomwe Yahya Mazana & Lembris Laayuni Njotto

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Both authors contributed to implement the study and to write this paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mzomwe Yahya Mazana .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

No conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Mazana, M.Y., Montero, C.S. & Njotto, L.L. Exploring Mathematics Teaching Approaches in Tanzanian Higher Education Institutions: Lecturers’ Perspectives. Int. J. Res. Undergrad. Math. Ed. 9 , 269–294 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40753-023-00212-4

Download citation

Accepted : 16 January 2023

Published : 01 February 2023

Issue Date : August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40753-023-00212-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mathematics

- Teaching approaches

- Teaching strategies

- Higher education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Your subscription is almost coming to an end. Don’t miss out on the great content on Nation.Africa

Ready to continue your informative journey with us?

Your premium access has ended, but the best of Nation.Africa is still within reach. Renew now to unlock exclusive stories and in-depth features.

Reclaim your full access. Click below to renew.

Subscribe for a month to get full access

Ten Tanzanian education-based startups to get funding

By Aurea Simtowe

Mwandishi wa Habari

What you need to know:

- These innovative solutions will enable students to access various lessons through technology, obtain study notes, and help track student attendance

Dar es Salaam. Ten startup ideas in the education sector are set to benefit from funding from the Mastercard Foundation, aimed at bridging the academic gap in the country, particularly for students living in rural areas.

These innovative solutions will enable students to access various lessons through technology, obtain study notes, and help track student attendance.

One of the selected startups is Shulesoft, which allows students from primary to secondary levels to access various subjects through its platform.

What ICT lab means for Tanzania’s digital economy endeavour

Why startup ecosystem needs additional attention in Tanzania

Read : What Tanzania ought to do to attract startup funding

It also assists in managing student attendance, academic performance, school operations, and even fee payments.

Shulesoft and nine others are grabbing this opportunity through the EdTech Project, managed by Sahara Consult in partnership with the Mastercard Foundation.

Speaking during the announcement of the winners, Sahara Consult’s CEO, Nancy Kiondo, said this programme is designed to support promising African EdTech ventures in partnership with innovation hubs and accelerators across the continent.

“Over the next eight months, Tanzania’s inaugural cohort of growth-stage EdTech companies will benefit from Sahara Consult mentorship through business and financial support and insight into the science of learning to prepare them for scale, sustainability and impact,” she said.

According to Nancy, this is the beginning of a new journey in innovation that will increase educational opportunities through technology.

The project will be implemented over the next five years and will address all aspects of education to achieve the desired outcomes.

Acting National Coordinator of the Tanzania Education Network, Martha Makala, noted that the project is essential for nurturing talent and ensuring education is accessible through comprehensive technological means.

“Considering the evolution of science and technology, it is vital for our education system to align with the ongoing fourth industrial revolution,” Ms Makala said.

“This five-year project will help elevate the education sector and complement other stakeholders’ efforts in integrating technology into education.”

Other beneficial startups are Shuleyetu Innovations Limited, Mtabe, Smartdarasa, Infotaaluma, Smartcore Enterprise Limited, Kilimanjaro Planetarium (part of Rada 360 Ltd.), MITz Group Company Limited, Fiqra Technologies, and Taifa Technovation Hub.

Some of these innovations do not require internet access, while others offer simple methods for learning science subjects.

The director general of the National Commission for Science and Technology (Costech), Dr Amos Nungu, said the project signifies the fruitful outcomes of the enabling environment established by the government.

“We invite other stakeholders to collaborate with our youth in various areas to help bring their ideas to market,” said Dr Nungu.

In the headlines

Simu2000 bus terminal closed to pave way for BRT depot construction

The Simu2000 bus terminal in the Ubungo area was closed today, September 14, 2024, to make way for the construction of a depot for the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system.

Calls grow for action plan to protect people with albinism in Tanzania

The African Albinism Network (AAN) executive director, Ikponwosa Ero, criticised Tanzania for its delay in endorsing the NAP, despite having a significantly larger population of people with...

Tanzania’s blueprint for regulatory reforms yields positive results

Since the adoption of the blueprint in 2019, the government has successfully reduced the costs associated with starting and running a business in Tanzania.

- Open access

- Published: 13 September 2024

Evaluating the implementation of the Pediatric Acute Care Education (PACE) program in northwestern Tanzania: a mixed-methods study guided by normalization process theory

- Joseph R. Mwanga 1 ,

- Adolfine Hokororo 1 , 2 ,

- Hanston Ndosi 1 ,

- Theopista Masenge 2 ,

- Florence S. Kalabamu 2 , 3 ,

- Daniel Tawfik 4 ,

- Rishi P. Mediratta 4 ,

- Boris Rozenfeld 5 ,

- Marc Berg 4 ,

- Zachary H. Smith 6 ,

- Neema Chami 1 , 2 ,

- Namala P. Mkopi 2 , 7 ,

- Castory Mwanga 2 ,

- Enock Diocles 1 ,

- Ambrose Agweyu 8 &

- Peter A. Meaney 4

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 1066 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), such as Tanzania, the competency of healthcare providers critically influences the quality of pediatric care. To address this issue, we introduced Pediatric Acute Care Education (PACE), an adaptive learning program to enhance provider competency in Tanzania’s guidelines for managing seriously ill children. Adaptive learning is a promising alternative to current in-service education, yet optimal implementation strategies in LMIC settings are unknown.

(1) To evaluate the initial PACE implementation in Mwanza, Tanzania, using the construct of normalization process theory (NPT); (2) To provide insights into its feasibility, acceptability, and scalability potential.

Mixed-methods study involving healthcare providers at three facilities. Quantitative data was collected using the Normalization MeAsure Development (NoMAD) questionnaire, while qualitative data was gathered through in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus groups discussions (FGDs).

Eighty-two healthcare providers completed the NoMAD survey. Additionally, 24 senior providers participated in IDIs, and 79 junior providers participated in FGDs. Coherence and cognitive participation were high, demonstrating that PACE is well understood and resonates with existing healthcare goals. Providers expressed a willingness to integrate PACE into their practices, distinguishing it from existing educational methods. However, challenges related to resources and infrastructure, particularly those affecting collective action, were noted. Early indicators point toward the potential for long-term sustainability of the PACE, but assessment of reflexive monitoring was limited due to the study’s focus on PACE’s initial implementation.

This study offers vital insights into the feasibility and acceptability of implementing PACE in a Tanzanian context. While PACE aligns well with healthcare objectives, addressing resource and infrastructure challenges as well as conducting a longer-term study to assess reflexive monitoring is crucial for its successful implementation. Furthermore, the study underscores the value of the NPT as a framework for guiding implementation processes, with broader implications for implementation science and pediatric acute care in LMICs.

Peer Review reports

Contributions to the literature

Introduces PACE : This study uniquely evaluated the PACE program in a low-resource setting, offering initial evidence on its implementation and potential impact on pediatric care.

Utilizes the NPT framework : By employing a NPT framework, this research provides a novel methodological example of how to assess the incorporation of e-learning in LMIC clinical settings.

Informs Implementation Strategies : These findings contribute to the design of effective e-learning strategies for healthcare education in LMICs, suggesting practical steps for broader application.

Expands Local Capacity : Demonstrates how PACE can build local healthcare capacity, informing ongoing efforts to sustainably improve pediatric care through education in similar environments.

Context and importance of the study

Pediatric in-service education for healthcare providers in Low- and Middle-income countries (LMICs) often lacks reach, effectiveness, and sustainability, contributing to millions of child deaths annually [ 1 , 2 ]. Pneumonia, birth asphyxia, dehydration, malaria, malnutrition, and anemia cause over 4 million child deaths annually, with half occurring in sub-Saharan Africa and thousands in Tanzania [ 3 , 4 ]. The Tanzanian government aims to reduce neonatal mortality from 20/100,000 to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) target of 12/100,000 by 2030 [ 5 ].

Brief review of the literature

Provider knowledge and skills competency are crucial for care quality in LMICs [ 2 , 6 ]. However, conventional in-service education methods are often inadequate and unsustainable [ 6 ]. These methods do not adapt to individual providers’ knowledge or schedules, target minimal competency, and lack long-term refresher learning, limiting their effectiveness [ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ].

Adaptive learning can address these limitations by customizing the timing and sequence of combined e-learning and in-person skills training, creating individualized pathways that reinforce learning and enhance skills competency. This approach helps mitigate manpower and resource shortages in LMICs and represents a strategic innovation in knowledge dissemination.

The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes the importance of e-learning solutions for healthcare workers globally [ 11 ]. Adaptive learning, with its capacity to adjust to individual needs, holds significant promise for enhancing training efficiency. However, formal studies on adaptive learning in LMIC contexts are scarce. Establishing best practices in e-learning and adaptive methodologies will enhance the dissemination of evidence-based interventions and improve clinical practice and patient outcomes.

To address current educational limitations for healthcare workers in LMICs, we developed the Pediatric Acute Care Education (PACE) program [ 12 , 13 ]. This adaptive e-learning program offers 340 learning objectives across 10 assignments, covering newborn and pediatric care guidelines for management of seriously ill children. The PACE program’s implementation strategy includes an adaptive e-learning platform optimized for mobile phones, a steering committee, a full-time PACE coordinator, and an escalating nudge strategy to encourage participation.

Study aims and objectives

The primary aim of this research is to assess the preliminary implementation of the PACE intervention across two types of pediatric acute care facilities: zonal hospitals and health centers. The study has two principal objectives: (1) To evaluate the initial PACE implementation in Mwanza, Tanzania, using the constructs of Normalization Process Theory (NPT); (2) To provide insights into its feasibility, acceptability, and scalability potential.

Study design

This study employed a mixed methods approach to evaluate the implementation of the PACE program in three healthcare settings in northwestern Tanzania, nested within a larger pilot implementation of PACE within eight health facilities of the Pediatric Association of Tanzania’s Clinical Learning Network. The study utilized NPT as a framework, combining quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitatively, a tailored NoMAD survey instrument evaluates the integration of PACE into routine clinical practice. Qualitatively, in-depth interviews and focus group discussions enrich the data.

Theoretical framework

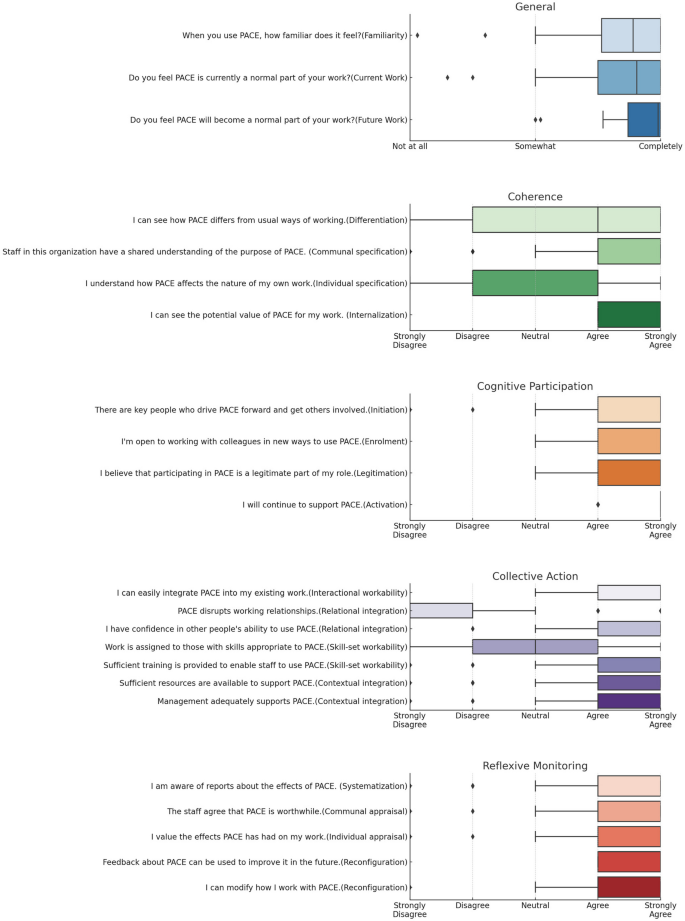

NPT has been described as a sociological toolkit for helping us understand the dynamics of implementing, embedding, and integrating new technology or a complex intervention into routine practice [ 14 ]. NPT provides a conceptual framework for understanding and evaluating the processes (implementation) by which new health technologies and other complex interventions are routinely operationalized in everyday work (embedding) and sustained in practice (integration) [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. The theory is organized around four main constructs, each of which has its own subconstructs [ 15 ]. These constructs collectively offer insights into the feasibility, acceptability, and scalability of an intervention or innovation (Fig. 1 ). Each of these constructs and subconstructs offers a unique lens through which the feasibility, acceptability, and scalability of a new practice can be evaluated, thereby aiding in its effective implementation.

Boxplot of participant responses to NoMAD survey by NPT construct and subconstruct

Study setting

The study was conducted between August 2022 and July 2023 at three healthcare facilities in Mwanza, Tanzania. The Bugando Medical Centre (BMC), an urban zonal referral and teaching hospital, sees about 7,000 births per year and 6,550 pediatric admissions per year for children aged 1 month to 5 years; the urban Makongoro Health Centre, handles approximately 359 births per year but refers newborn and pediatric admissions to the nearby regional or zonal hospital; and the rural Igoma Health Centre sees about 3,850 births per year and 959 pediatric admissions per year for children aged 1 month to 5 years.

Eligibility criteria

Providers included in the study were required to have a minimum command of English and be actively providing pediatric care to sick patients at least part-time. Eligible providers encompassed a wide range of professional cadres, reflecting the diversity of healthcare providers in Tanzania. These included specialists (medical officers with 3 additional years of specialization), medical officers (5 years of education and 1-year internship), nursing officers (4 years of education and 1-year internship), assistant medical officers (clinical officers with 2 additional years of clinical training), assistant nursing officers (3 years of education), clinical officers (3 years of education), clinical assistants (2 years of education), enrolled nurses (2 years of education), and medical attendants (1 year of education). In addition to providers, senior facility staff with administrative roles who supervise PACE providers, such as ward matrons, medical officers-in-charge, and nursing officers-in-charge, were eligible to participate. The bulk of the care is provided by junior medical officers and nurses, who have limited training and experience caring for children with severe illnesses

Recruitment process

Healthcare providers were informed about the study through their facility leaders, and individuals who responded to the survey were not necessarily the same as those who participated in the focus groups or in-depth interviews.

Data collection tools

Nomad questionnaire.

The NoMAD is a 23-item questionnaire based on the NPT that was designed to assess the social processes influencing the integration of complex interventions [ 18 , 21 ]. It includes 3 general items and 20 related to specific NPT constructs (4 Coherence, 7 Collective Action, 4 Cognitive Participation, 5 Reflexive Monitoring). The general items were scored on a scale of 0-100, and the NPT construct items were modified to include a five-point Likert scale (1-Strongly Agree, 5-Strongly Disagree) and additional options for respondents to indicate whether a question was not relevant to their role, stage, or intervention itself. The NPT subconstruct survey items are listed in Table 1 , and the complete survey is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

In-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs)

Interview guides were developed based on previous experience with similar data collection tools. The training and pretesting of the tools were conducted by the study investigators.

Data collection process

Nomad survey.

All PACE participants were invited via WhatsApp to complete the NoMAD survey directly in REDCap, 30 days post-intervention or upon completion of the PACE course.

Focus group discussions and in-depth interviews

We employed a purposeful sampling strategy for the qualitative components, selecting senior healthcare providers for in-depth interviews (IDIs) and junior providers for focus group discussions (FGDs). This approach ensured junior providers felt comfortable speaking openly, avoiding inhibition from senior participants in focus groups, and facilitated methodological triangulation to enhance the credibility and validity of the findings. Data was triangulated using three different types: methodological triangulation with IDIs and FGDs, investigator triangulation with different research assistants collecting data, and data triangulation using data from IDIs, FGDs and NoMAD surveys. Data collection began with a series of field visits, guided by NPT constructs, and included IDIs and FGDs. FGDs, segregated by sex but including a mix of cadres from each health facility, enriched the diversity of perspectives. The iterative nature of our methodology allowed for continuous refinement of our theoretical framework, methodologies, and sampling strategies, informed by emerging data. Consequently, the guides for both the IDIs and FGDs were dynamically modified to reflect the evolving study themes. All sessions, including IDIs and FGDs, were conducted in Kiswahili at the providers’ work premises, adding contextual depth. The IDI and FGD interview guides were originally developed in English, translated into Kiswahili (the national language), and then back translated into English to ensure that the meaning was retained. Both IDIs and FGDs were meticulously audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and then translated into English for analysis. Back-translation was employed to ensure validity.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis.

Descriptive statistics are reported as frequencies and percentages or medians and interquartile ranges, with comparisons via Fisher’s exact test or the Mann‒Whitney U test as appropriate. Analyses were conducted using Stata 17.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Qualitative analysis

The analysis process, conducted concurrently with data collection, was instrumental in achieving theoretical saturation, marked by the cessation of new information from ongoing IDIs and FGDs. To ensure the validity and depth of our findings, we implemented member checking and investigator triangulation, with two independent investigators coding and interpreting the data using NVivo 2020 software (QSR International Pty Ltd., Sydney, Australia). This software facilitated a hybrid coding approach in which blended deductive and inductive methods were used for comprehensive thematic content analysis. Contextual insights from the IDIs and FGDs were key to interpreting the findings, with representative quotations included to illustrate the identified themes. Data triangulation was achieved using diverse data sources, and the research team’s expertise further enhanced the rigor and reflexivity of the analysis.

Summary of feasibility, acceptability and scalability

We used the Proctors definition of implementation outcomes and mapped the NoMAD survey results to NPT subconstructs using the definition of May et al. [ 22 , 23 ].

Feasibility is concerned with the practical aspects of implementing a new intervention, including resource allocation, training, and ease of integration into existing work. In the NPT, this aligns closely with the construct of “collective action,” which refers to the operational work that people do to enact a set of practices. To assess feasibility, we interpreted our responses as follows: “Sufficient training is provided to enable staff to use PACE” (collective action, skill set workability); “Sufficient resources are available to support PACE”; “Management adequately supports PACE” (collective action, contextual integration); and “I can easily integrate PACE into my existing work” (collective action, interactional workability).

Acceptability refers to the extent to which the new intervention is agreeable or satisfactory among its users. To assess acceptability, we interpreted our responses as follows: “Staff in this organization have a shared understanding of the purpose of PACE” (coherence: communal specification); “I believe that participating in PACE is a legitimate part of my role” (cognitive participation, legitimation); “The staff agree that PACE is worthwhile” (reflexive monitoring, communal appraisal); and “I value the effects PACE has had on my work” (reflexive monitoring, individual appraisal). In addition, we compared scores between zonal hospitals and health centers.

Scalability involves the ability to expand the intervention to other settings while maintaining its effectiveness. To assess scalability, we interpreted our responses as “I will continue to support PACE” (cognitive participation, activation); “Work is assigned to those with skills appropriate for PACE” (collective action, skill set workability); “feedback about PACE can be used to improve it in the future”; and “I can modify how I work with PACE” (reflexive monitoring, reconfiguration).

Ethical considerations

All the providers provided informed consent, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Tanzania National Institute of Medical Research (NIMR/HO/R.8a/Vol. IX/3990), Stanford University (60379), the ethics committee of the Catholic University of Health and Allied Science (no ID number given), and the Mwanza Regional Medical Officer (Ref. No. AG.52/290/01A/115).

Techniques to enhance trustworthiness

Techniques to enhance trustworthiness included a purposeful sampling strategy, meticulous data collection in Kiswahili with back-translation, and the use of methodological, investigator, and data triangulation [ 24 ]. The analysis process was iterative and concurrent with data collection, employing hybrid coding and member checking to ensure systematic, explicit, and reproducible findings.

Reporting guidelines

This study adheres to the STROBE and SRQR reporting guidelines for comprehensive and explicit reporting of observational and qualitative studies, respectively [ 25 , 26 ].

Provider demographics

Eighty-two of the 272 eligible healthcare providers from the three facilities completed the NoMAD survey, resulting in a 30% response rate. Of the 82 respondents, 59 were from zonal hospitals and 23 from health centers (Table 2 ). The median ages were 27 and 29 years for zonal hospital and health center staff, respectively. The gender distribution was similar in both settings, with 39% female in the zonal hospital group and 43.5% in the health centers.

There were significant differences in cadre distribution: zonal hospitals had more medical staff (47.5% vs. 8.7%) and nurses (42.4% vs. 30.4%), while health centers had more clinical officers (30.4% vs. 0%). Clinical experience also varied, with a median of 1 year at zonal hospitals and 4 years at health centers ( p = 0.004). Previous participation in newborn or pediatric in-service education (e.g., Helping Babies Breathe, Helping Children Survive) was similar across the facilities, ranging from 71% to 73%. Job satisfaction scores did not significantly differ between the two groups.

A total of seventy-nine healthcare providers participated in IDIs or FGDs. Twenty-four senior providers completed IDIs, 18 from the zonal hospital and 6 from health centers., 13 FGDs with an average of 4 junior providers per group were conducted to achieve thematic saturation, including 39 participants from zonal hospitals and 16 from health centers. The represented cadres included medical officers (26, 32.9%), nurses (19, 24.1%), interns (16, 20.3%), clinical officers (12, 15.2%), assistant medical officers (3, 3.8%), and medical attendants (3, 3.8%). Clinical experience among participants ranged from 1 to 20 years. Compared to the NoMAD survey, participants in IDIs and FGDs included a higher proportion of medical officers (including interns) and clinical officers, but a lower proportion of nursing officers and other cadres.

NoMAD survey results

General items.

Familiarity and general satisfaction with PACE were high, with median scores of 89 and 91, respectively, and both showed moderate, balanced variability (interquartile ranges of 76-100 and 75-100, respectively) (Table 3 , Fig. 1 ). Optimism for the future use of PACE was highest, with a median score of 99 and narrow variability (87-100), indicating a strong skew towards higher scores. No significant differences were observed between the zonal hospitals and health centers.

NPT constructs

Providers reported understanding how to work together and plan the activities to put PACE and its components into practice. Strong agreement on the value of PACE is indicated by the median score for “Internalization" (1, “strongly agree,” IQR [1, 2]) (Table 3 , Fig. 1 ). Agreement on PACE’s purpose and its differentiation from existing work is indicated by the median scores for “Communal Specification” (2, “agree,” IQR [1, 2]), “Differentiation” (2, “agree,” IQR [1, 4]) and “Individual Specification” (2, “agree,” IQR [2, 4]), respectively. No significant differences were observed between the zonal hospitals and health centers.

Cognitive participation

Providers reported understanding how to work together to create networks of participation and communities of practice around PACE and its components. Strong agreement for ongoing PACE support, PACE participation and leadership, and PACE integration into work is indicated by the median scores for “Activation” (1, “strongly agree,” IQR [1, 1]), “Enrollment” (1, “strongly agree,” IQR [1, 1]), “Initiation” (1, “strongly agree,” IQR [1, 1]), and “Legitimation” (1, “strongly agree,” IQR [1, 2]), respectively. Narrow IQRs highlight the homogeneous support among providers. No significant differences were observed between the zonal hospitals and health centers.

Collective action