An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Human Subjects Research

Types of Human Subjects Research

On this page, analysis of existing data or specimens, observational studies, interventional studies.

If you're using private information, data, or specimens, your research may be exempt from the Code of Federal Regulations 45 Part 46. You may refer to the NIH Office of Extramural Research (OER) decision tool or consult with your institutional review board (IRB) or independent ethics committee (IEC). The NIDCR evaluates each project independently to determine oversight needs and whether the NIDCR Clinical Terms of Award (CToA) applies.

Toolkit for Analysis of Existing Data

In an observational study, the investigator simply records observations and analyzes data, without assigning participants to a specific intervention or treatment. These studies may focus on observation of risk factors, natural history, variations in disease progression or disease treatment without delivering or assigning an intervention. They often assess specific health characteristics of the enrolled human subjects by collecting medical/dental history, exposure, or clinical data; obtaining biospecimens (e.g., for biomarker or genomic analyses); or obtaining photographic, radiographic or other images from research subjects.

Toolkit for Observational Studies

The NIH defines an intervention as a manipulation of the subject or the subject's environment for the purpose of modifying one or more health-related biomedical or behavioral processes and/or endpoints. The NIH further defines a clinical trial as a research study in which one or more human subjects are prospectively assigned to one or more interventions (which may include placebo or other control) to evaluate the effects of those interventions on health-related biomedical or behavioral outcomes.

Toolkit for Interventional Studies

Defining Research with Human Subjects

A study is considered research with human subjects if it meets the definitions of both research AND human subjects, as defined in the federal regulations for protecting research subjects.

Research. A systematic inquiry designed to answer a research question or contribute to a field of knowledge, including pilot studies and research development.

Human subject: A living individual about whom an investigator (whether professional or student) conducting research:

- Obtains information or biospecimens through intervention or interaction with the individual, and uses, studies, or analyzes the information or biospecimens; or

- Obtains, uses, studies, analyzes, or generates identifiable private information or identifiable biospecimens.

The following sections will explain some of the words in the previous definitions.

The regulatory language:

A systematic inquiry designed to answer a research question or contribute to a field of knowledge, including pilot studies and research development.

The explanation:

Understanding what constitutes a systematic inquiry varies among disciplines and depends on the procedures and steps used to answer research questions and how the search for knowledge is organize and structured.

Pilot Studies and Research Development

Pilot studies are designed to conduct preliminary analyses before committing to a full-blown study or experiment.

Research development includes activities such as convening a focus group consisting of members of the proposed research population to help develop a culturally appropriate questionnaire.

Practical applications:

- You are conducting a pilot study or other activities preliminary to research; or

- You have designed a study to collect information or biospecimens in a systematic way to answer a research question; or

- You intend to study, analyze, or otherwise use existing information or biospecimens to answer a research question.

Human Subjects

Human subjects are living individuals about whom researchers obtain information or biospecimens through interaction, intervention, or observation of private behavior, to also include the use, study, and analysis of said information or biospecimens.

Obtaining, using, analyzing, and generating identifiable private information or identifiable biospecimens that are provided to a researcher is also considered to be human subjects.

To meet the definition of human subjects, the data being collected or used are about people. Asking participants questions about their attitudes, opinions, preferences, behavior, experiences, background/history, and characteristics, or analyzing demographic, academic or medical records, are just some examples of human subjects data.

- Interacting with people to gather data about them using methods such as interviews, focus groups, questionnaires, and participant observation; or

- Conducting interventions with people such as experiments or manipulations of subjects or subjects' environments; or

- Observing or recording behavior, whether in-person and captured in real time or in virtual spaces, like social media sites (e.g., Twitter) or online forums (e.g., Reddit); or

- Obtaining existing information about individuals, such as students’ school records or patients’ health records, or data sets provided by another researcher or organization.

Interactions and Interventions

Interventions are manipulations of the subject or the subject's environment, for example is a behavioral change study using text messages about healthy foods.

Interactions include communication or interpersonal contact between investigator and participant.

A study may include both interventions and interactions.

Interactions and interventions do not require in-person contact, but may be conducted on-line.

Private Information

Private information includes information or biospecimens: 1) about behavior that occurs in a context in which an individual can reasonably expect that no observation or recording is taking place; 2) that has been provided for specific purposes by an individual; and 3) that the individual can reasonably expect will not be made public (for example, a medical record).

Private information must be individually identifiable (i.e., the identity of the subject is or may readily be ascertained by the investigator or associated with the information) in order for the information to constitute research involving human subjects.

The regulations are clear that it is the subjects’ expectations that determine what behaviors, biospecimens, and identifiable information must be considered private. Subjects’ understanding of what privacy means are not universal, but are very specific and based on multiple interrelated factors, such as the research setting, cultural norms, the age of the subjects, and life experiences. For example, in the United States, health records are considered private and protected by law, but in some countries, health information is not considered private but are of communal concern.

Identifiable Information

The identity of the subject is associated with the data gathered from the subject(s) existing data about the subjects. Even if the data (including biospecimens) do not include direct identifiers, such as names or email addresses, the data are considered identifiable if names of individuals can easily be deduced from the data.

If there are keys linking individuals to their data, the data are considered identifiable.

Levels of Review

Not all projects that meet the definition of research with human subjects need review by the actual committee. For example, projects that pose negligible risk to participants may be reviewed and recommended for approval by IRB staff ; other projects may need to undergo review and approval by at least one member of the IRB committee or a quorum of the full board. Determination as to the need for review should always be made by the IRB staff.

Examples of Studies That MAY Meet the Definition of Research with Human Subjects

The following examples will likely require further consultation with an IRB staff member.

Analysis of existing information with no identifiers

If researchers have no interaction with human subjects, but will be conducting a secondary analysis of existing data without individual identifiers, the analysis of those data may not be research with human subjects.

Expert consultation

Key words in the definition of a human subject are "a living individual about whom" a researcher obtains, uses, studies, analyzes, or generates information. People can provide you information that is not about them but is important for the research. For example, a researcher may contact non-governmental organizations to ask about sources of funding.

Program evaluations and quality improvement studies

Program evaluations are generally intended to query whether a particular program or curriculum meets its goals. They often involve pre- and post-surveys or evaluations.

Some program evaluations include a research component. If data are collected about the characteristics of the participants to analyze the relationship between demographic variable and success of the program, the study may become research with human subjects. Research question: Are there different learning outcomes associated with different levels of participant confidence?

Classroom research

Classes designed to teach research methods such as fieldwork, statistical analysis, or interview techniques, may assign students to conduct interviews, distribute questionnaires, or engage in participant observation. If the purpose of these activities is solely pedagogical and are not designed to contribute to a body of knowledge, the activities do not meet the definition of research with human subjects.

Vignettes: Applying the Definitions

Art in Cambodia

An art history student wants to study art created by Cambodians in response to the massacres committed by the Khmer Rouge. The art she will study includes paintings, sculpture, video, and the performing arts.

Much of the research will be archival, using library and online resources. In addition, she will visit Cambodia. While there, she will speak with several museum curators for assistance locating and viewing art collections related to the massacres.

Is this research with human subjects?

No. Although the student will speak with curators, they are not the subjects of her research and she is not interested in learning anything about them. They will, in effect, serve as local guides.

What would make the study research with human subjects?

The student interviews people as they interact with art to understand the role of the arts in evoking and/or coming to terms with traumatic past events. She interviews people who view the art, such as visitors to museums, and discusses what the art means to them. She may collect information about their experiences during the genocide and compare those experiences with their reactions to the art.

Bank-Supported Micro-Finance in Chile

A researcher is interested in the practice of microfinance in the Chilean Mapuche community. She meets with bankers and asks about the criteria for granting loans, the demographics of the people who receive loans, the types of businesses to which the bank prefers to grant loans, how many loans they give, the payback rates, and other data about the bank’s loan practices.

No. Although the researcher is interviewing bankers, the bankers are only providing information about their banking practices and are not providing any information about themselves. The questions are about “what” rather than “about whom.” The bankers are not human subjects. This type of interview is sometimes referred to as expert consultation.

The researcher explores the impact of small loans, both intended and unintended, on the recipients of the loans. The researcher interviews the recipients of the loans and gathers information from them about their lives before and after they received funding, how the loans affected their relationships with family members and other community members, the impact of the loans on their aspirations, and so on. He asks “about whom” questions designed to understand the impact of micro-loans.

Developing Teaching Materials

A researcher goes to a country in which the infrastructure has been severely damaged to help rebuild schools. The student interviews community members about what curricular materials they need, develops some materials, and teaches a math class.

No. Although interviews are conducted, the intent of interviewing is to assist in resource development rather than answer a research question designed to contribute to a field of knowledge.

If the researcher does pre- and post-testing to assess student learning in his class, is this research with human subjects?

No. The intent is to find out if the materials are effective. This is sometimes referred to as program assessment.

What would make this research with human subjects?

The researcher studies the impact of nutrition and personal variables on learning. He assesses the nutritional composition of the local diet, assesses students’ general health, and compares those data with test scores. He also measures motivation, family composition, and other characteristics of the students using written questionnaires.

Water Conservation

A researcher wants to find out if the campus water conservation program is effective. She will gather some information about water volume usage from the University engineering department. She will also survey residential students about their water usage habits over the last six months, their perceptions of the campus drought education program, and their reactions to the incentives offered by the program (water-saving competitions, free water-saving devices, etc.) She will report her findings to the program’s steering committee and administrators.

No. Although the researcher will systematically survey other students and will be collecting information about them, her intention is to assess the effectiveness of the conservation program.

The researcher designs an online survey to collect information that may help understand factors that influence the residential students’ responses to the conservation program. She asks questions about green attitudes and behaviors, positions on social and political issues, as well as motivation and narcissism.

Campus IRB Guides

- Organizational Chart

- Annual report

- Research Videos

- Institutes & Centers

- Associate Research Deans

- Request LabArchives Access

- How To Get Started

- Help & Support

- Required Forms & Training

- Helpful Resources

- Sponsored Programs

- Licensing & Ventures

- Website tips

- Presentation Tips

- Social Media Tips

- Media Interviews

- Write for The Conversation

- UVA Communicators

- Research Core Resources

- Strategic Investment Fund

- Economic Development

- Research Navigators

- Licensing and Ventures Group

- Graduate & Postdoctoral Affairs

- Corporate & Foundation Relations

- Research Development

- Office of Undergraduate Research

- Animal Care & Use Committee

- Office of Animal Welfare

Human Research Protection Program

- Conflict of Interest

- Controlled Substances

- Environmental Health & Safety

- ResearchUVA Powered by Huron

- Center for Comparative Medicine

- Unmanned Aircraft (UAS)

- National Security Program

- Compliance Education

- University's Compliance Helpline

- Research Misconduct Definitions

- Education & Training

- References and Resources

- Export Controls

- Research Data Compliance

- Research Regulations

- UVA Policy Directory

- Research Continuity Guidance

- Office of Sponsored Programs

- Nobel Laureate Lecture Series

- Webinar: (P2PE) STEM Targeted Initiatives Fund

- Scientific Integrity Workshop

- Research Town Hall

- Tackling the COVID-19 Crisis

- Rath Award Recipients

- Manning Fund for COVID-19 Recipients

- Ivy Fund for COVID-19 Research RFA

- Ivy Foundation COVID-19 Recipients

- 2023 Award Winners

- 2022 Award Winners

- 2021 Award Winners

- 2020 Award Winners

- 2019 Award Winners

- 2024-2025 Syllabus

- 2023-2024 Research Communications Fellows

- 2023-2024 Syllabus and Calendar

- 2022-2023 Research Communications Fellows

- 2022-2023 Calendar

- Research Collaboration Corner

- Ivy Biomedical Innovation Fund

- Coulter Translational Research Partnership

- Entrepreneurship @UVA

- Faculty Fellows

- Development of Large Collaborative Proposals

- Limited Submission Opportunities

- Submitting the Required Internal LOI

- Funding Discovery Tools

- Partners for Broader Impacts

- Internal Funding Opportunities

- Community of Research Development (CoRD)

- Brain and Neuroscience

- Environmental Resilience and Sustainability

- Digital Technology and Society

- Precision Medicine/Health

- UVA Research Update - October 19, 2023

- Prominence-to-Preeminence (P2PE) STEM Targeted Initiatives Fund

Defining Human Subjects Research

Human subjects research is any research or clinical investigation that involves human subjects. The federal regulations define a human subject as a living individual about whom an investigator conducting research obtains (1) data through intervention or interaction with the individual ; or (2) identifiable private information .

Intervention includes both physical procedures by which data are gathered (e.g., survey) and manipulations of the subject or the subject's environment that are performed for research purposes. Interaction includes communication or interpersonal contact between investigator and subject. Private information includes information about behavior that occurs in a context in which an individual can reasonably expect that no observation or recording is taking place, and information which has been provided for specific purposes by an individual and which the individual can reasonably expect will not be made public (for example, a medical record). Private information must be individually identifiable (i.e., the identity of the subject is or may readily be ascertained by the investigator or associated with the information) in order for obtaining the information to constitute research involving human subjects.

Not all research that involves people is "human subjects research" but instead the individual is a " human source ." The term “human source” defines situations where a researcher is interacting with another individual to gain knowledge about something but isn’t collecting personal information about that person. For example, the researcher wants to know the current policies for dealing with bulling at a school, so he calls a school administrator to ask that person about the school’s bullying policy and how it was developed, but does not ask about the administrator’s personal experience and how she felt about the policy. The school administrator is a human source but does not become a human subject until she provides personal information about her experience with the policy, bullying, etc. For more examples, please see the IRB-SBS webpage on Activities That Require IRB-SBS Review.

- Technical Help

- CE/CME Help

- Billing Help

- Sales Inquiries

Human Subjects Research (HSR)

This series provides core training in human subjects research and includes the historical development of human subject protections, ethical issues, and current regulatory and guidance information.

About these Courses

Human Subjects Research (HSR) content is organized into two tracks: Biomedical (Biomed) and Social-Behavioral-Educational (SBE) . They are intended for anyone involved in research studies with human subjects, or who have responsibilities for setting policies and procedures with respect to such research, including Institutional Review Boards (IRBs). HSR Biomed and SBE courses are offered as Comprehensive and Foundation versions.

Comprehensive courses provide an expanded training covering not only major topical areas but also many concepts that are specific to types of research, roles in the protection of human subjects, and advanced modules on informed consent topics, vulnerable populations, stem cell research, phase I research, data and safety monitoring, big data research, mobile apps research, and disaster and conflict research.

Foundations courses provide foundational training covering major topic areas in human subjects protections.

This series also include refresher course options for both the Biomed and SBE tracks. Refresher courses provide retraining for individuals who have already completed a basic course. CITI Program offers a variety of refresher courses so learners can meet retraining requirements with fresh content.

Additional modules of interest within HSR allow for exploration of several important topics and may be selected to meet organizational needs.

HSR includes additional standalone courses for different specific roles including institutional/signatory officials, IRB chairs, public health researchers, and Certified IRB Professionals (CIPs) seeking recertification credit. Topic-focused mini-courses such as Single IRB (sIRB) Use and Administration , Clinical Trial Agreements , Phase I Research , and Community-Engaged and Community-Based Participatory Research , as well as a standalone Revised Common Rule course that covers the regulatory updates to the Common Rule (45 CFR 46, Subpart A) are also available.

All HSR modules reflect the revised Common Rule (2018 Requirements). Upon request, a selection of HSR modules are available as legacy versions (reflecting the pre-2018 requirements).

These courses were written and peer-reviewed by experts.

Note: Organizations subscribing to HSR have access to all of the modules included in the courses below.

Demo of Informed Consent Case Videos:

Language Availability: English, Korean, Spanish, French

Suggested Audiences: Human Subject Protection Staff, Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), Institutional/Signatory Officials, IRB Administrators and Staff, IRB Chairs, Research Team Members, Researchers, Students

Basic Courses

This course provides an expansive review of human subjects research topics for biomedical researchers.

This foundational course provides a focused introduction to the essential human subjects research topics for biomedical researc...

This course provides an expansive review of human subjects research topics for social-behavioral-educational researchers.

This foundational course provides a focused introduction to the essential human subjects research topics for social-behavioral-...

Refresher Courses

This course provides retraining on the HSR Biomed Basic course and discusses core human subjects research topics for biomedical...

This course provides retraining on the HSR SBE Basic course and discusses core human subjects research topics for social-behavi...

Additional Courses

Learn how to create participant-centered informed consent forms through this interactive training.

This course provides detailed training for current and future Institutional Review Board (IRB) chairs.

Provides a foundational training for institutional/signatory officials on their roles and responsibilities as part of an HRPP.

Provides an overview of the structure and function of public health systems, differentiates research and practice, and reviews consent and ethical issues for public health researchers.

Comprehensive training covering the Final Rule updates to the Common Rule.

This course covers relying on a sIRB, serving as a sIRB of record, and authorization agreements.

Provides sites and investigators an overview of CTA development, negotiation, and execution.

Provides an introduction to phase I research and the protection of phase I research subjects.

Delivers introductory information to help researchers and community partners participate in research partnerships.

Additional Courses for Independent Learners

Provides foundational training for IRB members involved in the review of biomedical human subjects research.

Provides foundational training for IRB members involved in review of social-behavioral-educational human subjects research.

Provides foundational training for IRB members involved in the review of both biomedical and social-behavioral-educational huma...

CIP Certified Courses

This course provides advanced learners all the CIP approved modules on topics such as informed consent, U.S. Food and Drug Admi...

This course provides advanced learners a topic-focused course on IRB administration and 4 CE hours for CIP recertification.

This course provides advanced learners a topic-focused course on biomedical and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) researc...

This course provides advanced learners a topic-focused course on subject population and informed consent topics as well as 9 CE...

Who should take human subjects research training?

Basic HSR courses are suitable for all persons involved in research studies involving human subjects (for example, researchers and staff), or who have responsibilities for setting policies and procedures with respect to such research, including Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and other members of organizational communities where research with human subjects occurs.

There are additional standalone courses that are intended for specific audiences such as institutional/signatory officials, IRB chairs, public health researchers, and Certified IRB Professionals (CIPs) seeking recertification credits. Additional standalone courses on IRB Administration and the Revised Common Rule are available. The Revised Common Rule course covers the regulatory updates to the Common Rule (45 CFR 46, Subpart A). Legacy versions of select basic and refresher modules are available for learners who need training on the pre-2018 requirements of the Common Rule. Legacy content must be requested by contacting CITI Program Support .

How long does it take to complete an HSR course?

HSR courses are comprised of modules that include detailed content, images, supplemental materials (such as, case studies), and a quiz. Learners may complete the modules at their own pace. Each module varies in length, and learners may require different amounts of time to complete the module based on their familiarity and knowledge of the topic. In general, modules can take about 30 to 45 minutes to complete.

What different courses are offered in HSR?

This series contains Basic and Refresher courses that are structured into two tracks: Biomedical (Biomed) and Social-Behavioral-Educational (SBE). These tracks contain different levels of review-- Compressive and Foundations. The Foundations level provides a review of the core concepts of human subjects protections, while the Comprehensive level contains additional modules of interest that allow for exploration of several important topics and may be selected to meet organizational needs. Organizations may group these modules to form courses.

Additional courses that are intended for specific audiences such as institutional/signatory officials, IRB chairs, public health researchers, and Certified IRB Professionals (CIPs) seeking recertification credits are also available. HSR also includes a standalone Revised Common Rule course covering the regulatory updates to the Common Rule (2018 Requirements).

The Basic Biomed modules have three corresponding sets of refresher modules and the Basic SBE modules have two corresponding sets of refresher modules. These refresher modules are intended to provide learners with a review of core concepts. It is generally recommended that organizations select refresher module requirements that reflect their selections for the basic course(s). Refresher courses should be taken in a cycle specified by the organization (for example, Refresher Stage 1: 3 years after completion; Refresher Stage 2: 6 years after completion).

The CIP courses should be taken by independent learners who are seeking CIP continuing education (CE) credits for recertification.

How frequently should learners take HSR training?

There is no uniform standard regarding how frequently HSR training should occur. However, most organizations select a three-year cycle of retraining. HSR Refresher courses allow organizations an endless number of options when it comes to presenting content to meet their retraining needs, including different timings between basic and refresher course stages depending on the learner group.

Does HSR fulfill the human subjects training requirement?

Yes, CITI Program’s HSR training fulfills the human subjects research training requirements if the learner completes the basic modules for either the Biomed or SBE Comprehensive or Foundations courses.

As an administrator setting up my organization, how should I select HSR modules for my learner groups?

CITI Program allows organizations to customize their learner groups, which means they can choose the content modules their learners need to complete. We will work with your CITI Program designated admin to determine the learner groups that best fit your organizational needs. You can also choose to use our recommended learner groups.

What topics does HSR cover?

HSR covers the historical development of human subject protections, as well as current regulatory information and ethical issues. It also has additional modules on various topics related to human subject research protections, including cultural competence, advanced issues in informed consent, external IRBs, phase I research, stem cell research, and population-specific content.

What are the advantages of CITI Program’s HSR training?

HSR was developed and reviewed by human subject research experts to help organizations and individuals understand human subjects research protections. Along with CITI Program's advantages, including our experience, customization options, cost effectiveness, and focus on organizational and learner needs, this makes it an excellent choice for HSR training.

Can learner groups include components from HSR and other subjects?

Yes, like all CITI Program educational materials, the modules that make up HSR can be customized to meet the specific needs of your organization. This includes selecting modules from other CITI Program subjects (for example, Good Clinical Practice , Responsible Conduct of Research , or Information Privacy and Security ) when creating a learner group for HSR. Additional subscription charges may apply. We can work with your CITI Program designated admin to determine learner groups and courses for your organization.

Are HSR courses eligible for CIP CE education credits?

Yes, advanced-level modules that meet the criteria in the Certified IRB Professional (CIP) recertification guidelines are eligible as accredited continuing education units for CIPs. These modules were approved by the Council for Certification of IRB Professionals (CCIP) as advanced-level and eligible for CIP CE credit. View CITI Program Advanced-Level Modules/Courses Eligible for CIP® Recertification Credit. for a list of approved modules.

What are the Other Courses for Independent Learners?

The “Other Courses for Independent Learners” are meant to provide additional course options that meet the unique needs of independent learners.

- The IRB Member – Biomedical Focus course is meant for IRB members who review biomedical research.

- The IRB Member – Social-Behavioral-Educational Focus course is meant for IRB members who review social-behavioral-educational research.

- The IRB Member – Biomedical and Social-Behavioral-Educational Combined course is meant for IRB members who review biomedical and social-behavioral-educational research.

These courses are intended for independent learners only. For more information on customizing learner groups as part of an organization subscription, see the “Can learner groups include components from HSR and other subjects?” FAQ.

Are HSR courses eligible for continuing medical education (CME) credits?

Yes, the following courses are eligible for CME credits:

- HSR – Biomedical (Biomed) Comprehensive Course

- HSR – Social-Behavioral-Educational (SBE) Comprehensive Course

- HSR – Biomedical Refresher 1 Course

- HSR – Biomedical Refresher 2 Course

- HSR – Biomedical Refresher 3 Course

- HSR – Social-Behavioral-Educational Refresher 1 Course

- HSR – Social-Behavioral-Educational Refresher 2 Course

- IRB Chair Course

Click on the course name above for details. For more information on how to ensure CME credit availability for learners at your organization, contact Support .

Are HSR courses updated to the Revised Common Rule (2018 requirements)?

Yes. All CITI Program modules affected by revisions to the Common Rule were revised by the general compliance date (21 January 2019). These modules reflect the 2018 Requirements of the Common Rule (the Final Rule issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS] at 45 CFR 46, Subpart A - "Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects" [the Common Rule] on 19 January 2017).

Prior to the general compliance date (21 January 2019), CITI Program modules reflected the pre-2018 requirements version of the Common Rule. CITI Program offers legacy content (upon request) that reflects the pre-2018 requirements of the Common Rule. Contact CITI Program Support for more information.

For more information, refer to support center article Current CITI Program Modules and the Final Revisions to the Common Rule .

Will I be notified if this course is significantly revised or updated?

Yes, CITI Program will notify administrators via email and post news articles on our website when courses are significantly revised or updated.

Is the Participant-Centered Informed Consent Training the same course available on the OHRP’s website?

Yes, CITI Program is proud to host this OHRP training, free for organizations using our HSR series. Integrate this course into your organization’s training curriculum for tracking, documentation, and support in our LMS. If your organization currently subscribes to the HSR series, contact Support to add this new course for free.

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| BUY_NOW | This cookie is set to transfer purchase details to our learning management system. | |

| CART_COUNT | This cookie is set to enable shopping cart details on the site and to pass the data to our learning management system. | |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Advertisement". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| JSESSIONID | session | Used by sites written in JSP. General purpose platform session cookies that are used to maintain users' state across page requests. |

| PHPSESSID | session | This cookie is native to PHP applications. The cookie is used to store and identify a users' unique session ID for the purpose of managing user session on the website. The cookie is a session cookies and is deleted when all the browser windows are closed. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| XSRF-TOKEN | session | The cookie is set by Wix website building platform on Wix website. The cookie is used for security purposes. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| bcookie | 2 years | This cookie is set by linkedIn. The purpose of the cookie is to enable LinkedIn functionalities on the page. |

| lang | session | This cookie is used to store the language preferences of a user to serve up content in that stored language the next time user visit the website. |

| lidc | 1 day | This cookie is set by LinkedIn and used for routing. |

| pll_language | 1 year | This cookie is set by Polylang plugin for WordPress powered websites. The cookie stores the language code of the last browsed page. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _gat | 1 minute | This cookies is installed by Google Universal Analytics to throttle the request rate to limit the colllection of data on high traffic sites. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, campaign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assign a randomly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gat_UA-33803854-1 | 1 minute | This is a pattern type cookie set by Google Analytics, where the pattern element on the name contains the unique identity number of the account or website it relates to. It appears to be a variation of the _gat cookie which is used to limit the amount of data recorded by Google on high traffic volume websites. |

| _gat_UA-33803854-7 | 1 minute | This is a pattern type cookie set by Google Analytics, where the pattern element on the name contains the unique identity number of the account or website it relates to. It appears to be a variation of the _gat cookie which is used to limit the amount of data recorded by Google on high traffic volume websites. |

| _gcl_au | 3 months | This cookie is used by Google Analytics to understand user interaction with the website. |

| _gid | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the website is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages visted in an anonymous form. |

| _hjAbsoluteSessionInProgress | 30 minutes | No description available. |

| _hjFirstSeen | 30 minutes | This is set by Hotjar to identify a new user’s first session. It stores a true/false value, indicating whether this was the first time Hotjar saw this user. It is used by Recording filters to identify new user sessions. |

| _hjid | 1 year | This cookie is set by Hotjar. This cookie is set when the customer first lands on a page with the Hotjar script. It is used to persist the random user ID, unique to that site on the browser. This ensures that behavior in subsequent visits to the same site will be attributed to the same user ID. |

| _hjIncludedInPageviewSample | 2 minutes | No description available. |

| _hjIncludedInSessionSample | 2 minutes | No description available. |

| _hjTLDTest | session | No description available. |

| _uetsid | 1 day | This cookies are used to collect analytical information about how visitors use the website. This information is used to compile report and improve site. |

| BrowserId | 1 year | This cookie is used for registering a unique ID that identifies the type of browser. It helps in identifying the visitor device on their revisit. |

| CFID | session | This cookie is set by Adobe ColdFusion applications. This cookie is used to identify the client. It is a sequential client identifier, used in conjunction with the cookie "CFTOKEN". |

| CFTOKEN | session | This cookie is set by Adobe ColdFusion applications. This cookie is used to identify the client. It provides a random-number client security token. |

| CONSENT | 16 years 5 months 4 days 4 hours | These cookies are set via embedded youtube-videos. They register anonymous statistical data on for example how many times the video is displayed and what settings are used for playback.No sensitive data is collected unless you log in to your google account, in that case your choices are linked with your account, for example if you click “like” on a video. |

| vuid | 2 years | This domain of this cookie is owned by Vimeo. This cookie is used by vimeo to collect tracking information. It sets a unique ID to embed videos to the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| bscookie | 2 years | This cookie is a browser ID cookie set by Linked share Buttons and ad tags. |

| IDE | 1 year 24 days | Used by Google DoubleClick and stores information about how the user uses the website and any other advertisement before visiting the website. This is used to present users with ads that are relevant to them according to the user profile. |

| MUID | 1 year 24 days | Used by Microsoft as a unique identifier. The cookie is set by embedded Microsoft scripts. The purpose of this cookie is to synchronize the ID across many different Microsoft domains to enable user tracking. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | This cookie is set by doubleclick.net. The purpose of the cookie is to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | This cookie is set by Youtube. Used to track the information of the embedded YouTube videos on a website. |

| YSC | session | This cookies is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | These cookies are set via embedded youtube-videos. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | These cookies are set via embedded youtube-videos. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _app_session | 1 month | No description available. |

| _gfpc | session | No description available. |

| _uetvid | 1 year 24 days | No description available. |

| _zm_chtaid | 2 hours | No description available. |

| _zm_csp_script_nonce | session | No description available. |

| _zm_cta | 1 day | No description |

| _zm_ctaid | 2 hours | No description available. |

| _zm_currency | 1 day | No description available. |

| _zm_mtk_guid | 2 years | No description available. |

| _zm_page_auth | session | No description available. |

| _zm_sa_si_none | session | No description |

| _zm_ssid | session | No description available. |

| AnalyticsSyncHistory | 1 month | No description |

| BNI_persistence | 4 hours | No description available. |

| BrowserId_sec | 1 year | No description available. |

| CookieConsentPolicy | 1 year | No description |

| cred | No description available. | |

| f | never | No description available. |

| L-veVQq | 1 day | No description |

| li_gc | 2 years | No description |

| owner_token | 1 day | No description available. |

| PP-veVQq | 1 hour | No description |

| renderCtx | session | This cookie is used for tracking community context state. |

| RL-veVQq | 1 day | No description |

| twine_session | 1 month | No description available. |

| UserMatchHistory | 1 month | Linkedin - Used to track visitors on multiple websites, in order to present relevant advertisement based on the visitor's preferences. |

| web_zak | past | No description |

| wULrMv6t | No description | |

| zm_aid | past | No description |

| zm_haid | past | No description |

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Transl Res

- v.15(9); 2023

- PMC10579004

Protecting human subjects participating in research

Objectives: Institutions conducting research involving human subjects establish institutional review boards (IRBs) and/or human research protection programs to protect human research subjects. Our objectives were to develop performance metrics to measure human research subject protections and to assess how well IRBs and human research protection programs are protecting human research subjects. Methods: A set of five performance metrics for measuring human research subject protections was developed and data were collected through annual audits of informed consent documents and human research protocols at 107 Department of Veterans Affairs research facilities from 2010 through 2021. Results: The proposed performance metrics were: local adverse events that were serious, unanticipated, and related or probably related to research, including those that resulted in hospitalization or death; where required informed consent was not obtained; required Heath Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization was not obtained; non-exempt research was conducted without IRB approval; and research activities were continued during a lapse in IRB continuing reviews. Analysis of these performance metric data from 2010 through 2021 revealed that incident rates of all five performance metrics were very low; three showed a statistically significant trend of improvement ranging from 70% to 100%; and none of these five performance metrics deteriorated. Conclusions: Department of Veterans Affairs human research protection programs appeared to be effective in protecting human research subjects and showed improvement from 2010 through 2021. These proposed performance metrics will be useful in monitoring the effectiveness of human research protection programs in protecting human research subjects.

Introduction

Institutional review boards (IRBs) and comparable entities, such as research ethics committees and ethics review boards, have been established for the primary purpose of protecting human subjects participating in research [ 1 ]. Since the establishment of the IRB system in the 1970s, research institutions have delegated the authorities and responsibilities of protecting human research participants to IRBs [ 2 ].

However, a number of events occurring at the turn of this century suggested that IRB oversight, as practiced at the time, was insufficient in protecting human research subjects. Two young individuals, Jesse Gelsinger and Ellen Roche, who out of altruism volunteered in phase one clinical trials at the University of Pennsylvania and Johns Hopkins University, died on September 17, 1999, and June 2, 2001, respectively, as a result of egregious noncompliance by the investigators, IRBs, and institutions involved [ 3 - 5 ]. In addition, a number of major academic institutions’ federally funded research programs were temporally suspended due to persistent and serious noncompliance with federal regulations [ 3 , 6 ]. It became clear that, in addition to IRBs, investigators, institutions, sponsors of research, research volunteers, and the federal government all share responsibility for protecting human research subjects [ 7 , 8 ].

Substantial efforts were made in the early 2000s to improve our systems for protecting human research subjects, including, but not limited to, stronger federal oversight of research, implementation of voluntary external accreditation of human research protection programs, improved training for investigators and IRB members, improved monitoring and reporting of adverse events, and greater involvement of research participants and the public in these reform efforts [ 6 , 7 ]. While the investment was substantial, it is not clear whether these improvement efforts have resulted in improved protections for research participants.

Despite repeated calls for measuring the effectiveness of IRBs and the enhanced measures listed above in protecting human research subjects, there has been little or no empirical evidence in the literature demonstrating that IRB review and other measures do, in fact, protect human research subjects effectively [ 9 , 10 ]. This has led some investigators to question whether IRBs actually protect human research subjects [ 11 , 12 ]. Critics who are frustrated with the perceived burdens imposed by IRBs, in the absence of demonstrated effectiveness, have suggested that IRBs delay or prevent important research from taking place, while increasing the cost of research and impeding investigators’ opportunities for academic promotion [ 13 , 14 ].

Measuring the incidence of actual harms to participants in research undergoing IRB review versus research not undergoing IRB review would provide a direct comparison of the effectiveness of IRB review. In order to demonstrate that IRBs protect human research subjects, it would be ideal to carry out a prospective, randomized trial, in which comparable research projects are randomly assigned to two groups, one receiving IRB review (the intervention group) versus one not receiving IRB review (the control group). If research subjects in projects receiving IRB review experienced less harms than subjects in projects not receiving IRB review, then one could reasonably conclude that IRBs are effective in protecting human research participants [ 2 , 15 ].

Unfortunately, this ideal study cannot be carried out for at least three reasons. First, the Federal Policy (Common Rule) for the Protection of Human Research Subjects stipulates that no research can be initiated prior to IRB approval, unless it is deemed to be exempt from the Rule’s requirements [ 16 ]. Second, there are no widely accepted strategies for directly measuring the effectiveness of human research subject protections [ 2 , 17 , 18 ]. Finally, given the well-documented harms experienced by human subjects prior to any requirements for IRB review, it could be considered unethical to conduct human research without some form of objective oversight.

Although it would not be possible to conduct the prospective, randomized trial described above, it might be possible to conduct a large retrospective comparison of research receiving versus not receiving IRB review. However, such a comparison would require development of objective criteria sufficient to ensure the equivalence of the research studies compared and a sufficiently large sample of studies from which to draw. This kind of large retrospective comparison would be a major undertaking and would probably have to be conducted on a national scale and at great expense.

Nevertheless, a practical approach focusing on actual harms to human subjects is needed to provide a meaningful measure of the effectiveness of IRB review (and potentially other research protections) at the institutional level.

In this report, we propose a set of performance metrics for assessing the effectiveness of human research subject protections and use data collected from 107 Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities conducting research involving human subjects from 2010 through 2021 to demonstrate the feasibility and utility of implementing these proposed metrics.

Measuring harms to research participants

Human research participants may experience two types of harms: concrete harms, such as physical or psychological injury, and dignitary harms, such as violations of autonomy or privacy rights. Measuring the incidence of these two types of harms actually experienced by research subjects would constitute a direct measure that institutions could use to demonstrate the effectiveness of their IRB reviews and human research protection programs.

Concrete harms

Concrete harms to subjects are reflected by the adverse events (i.e., physical or psychological harms) actually experienced by subjects participating in research. Examples might include death, disease progression, untoward drug effects, medical device malfunctions, failed surgical techniques, or interventions resulting in psychological harms.

Adverse events can be anticipated or unanticipated, and related or unrelated to the research. Anticipated adverse events related to research are the foreseeable risks of the research interventions (e.g., the administration of investigational drugs or the use of medical devices). These foreseeable risks are typically described in the research protocol, investigator’s brochure, and informed consent document that the IRB reviews. They must be disclosed to potential participants considering research participation [ 19 ].

Serious adverse events that are unanticipated and related to research are especially important because they constitute actual harms to subjects associated with previously unknown risks that were not disclosed to them. These events typically require substantive changes in the research protocol and informed consent document, and/or corrective actions to protect the safety and welfare of future participants [ 19 ]. As demonstrated in the case of Jesse Gelsinger and Ellen Roche, unanticipated, serious, research-related adverse events often occur due to egregious noncompliance by investigators, IRBs, and/or institutions [ 3 - 5 ].

The Common Rule requires that unanticipated, serious adverse events be promptly reported to the IRB, institutional official, agency head, and the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) [ 16 , 19 ]. The OHRP defines serious adverse event as any adverse event that (1) results in death; (2) is life-threatening (places the subject at immediate risk of death from the event as it occurred); (3) results in inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization; (4) results in a persistent or significant disability/incapacity; (5) results in a congenital anomaly or birth defect; or (6) based upon appropriate medical judgment, may jeopardize the subject’s health and may require medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the other outcomes listed in this definition [ 19 ].

We propose that the incidence of adverse effects determined by the IRB to be unanticipated, serious, and related (or possibly related) to the research would constitute a useful metric for capturing concrete harms actually experienced by research subjects.

Institutions could monitor trends in this metric to access the relative effectiveness of its IRB reviews (and other human research protections) over time.

Dignitary harms

We propose that dignitary harms associated with violations of human autonomy rights occur when research subjects are not given the opportunity to exercise meaningful informed consent. Enrolling subjects in research without obtaining informed consent is contrary to the ethical principle of respect for persons of the Belmont Report, and is a violation of the subject’s right to be respected as an autonomous person [ 20 ]. Thus, the incidence of failure to obtain informed consent from subjects (or their legally authorized representatives) constitutes a metric directly reflecting dignitary harm to human autonomy rights.

We propose that dignitary harms associated with violations of human privacy rights occur when research subjects are not afforded all the protections required under the Heath Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) [ 21 ]. Thus, the incidence of failure to obtain HIPAA authorization from subjects (or their legally authorized representatives) constitutes a metric directly reflecting dignitary harms to human privacy rights.

Other metrics that may indirectly reflect dignitary harms to subjects include the incidence of (non-exempt) research conducted without IRB approval and the incidence of research conducted without continuing IRB review because meaningful informed consent and full HIPAA protections are uncertain under those circumstances.

In addition, the Common Rule requires IRBs to ensure that research has met eight approval criteria that satisfy all three ethical principles of the Belmont Report [ 16 ] and reflect basic human dignitary rights. Thus, when human research is conducted without prospective IRB review, approval, and oversight, or when investigators continue research activities during lapses in required IRB continuing review, research participants are not afforded Common Rule protections, including assurance of their basic dignitary rights. They are also exposed to situations that could result in serious harm.

We sought to demonstrate the utility of the performance metrics proposed above by examining quality assurance data available from the 107 Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical facilities with human research programs.

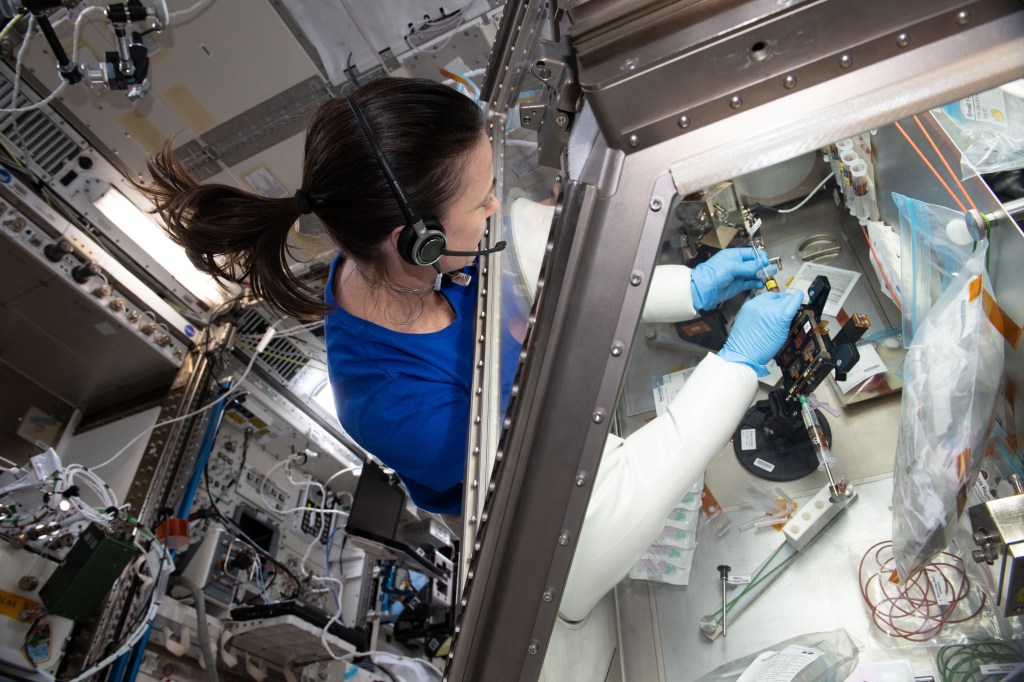

Data collection

The VA Office of Research Oversight (ORO) has collected quality assurance performance metric data on VA human research protection programs each year starting in 2010. VA facility research compliance officers were required to conduct audits of all informed consent documents annually and regulatory audits of all human research protocols once every three years using auditing tools that ORO had developed (available at https://www.va.gov/ORO/orochecklists.asp). Approximately one third of all active human research protocols were audited each year. For protocols that had been active for more than three years, protocol regulatory audits were limited to the most recent three years of research. Results of these audits conducted between June 1 and May 31 of each year were collected from all VA research facilities through a web-based system [ 22 , 23 ].

Ethic statement (human subject protections)

This was a quality assurance project. It did not involve human subjects and no individually identifiable information was collected. Therefore, no IRB review and approval were necessary [ 24 ].

Data analysis

Data on human research subject protection performance metrics from 2010 through 2021 were used in this study. We used analysis of ordinal categorical data as described by Agresti [ 25 ] to determine the trend of change from 2010 through 2021. This was performed using JavaStat ordinal contingency table analysis available at www.statpages.info. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. For those performance metrics with statistically significant changes, we also calculated percent changes from 2010 through 2021 using the following formula: Percent change = [(rate in 2021 - rate in 2010) ÷ rate in 2010] × 100 [ 23 ].

Assessing human research subject protections

Unanticipated, serious adverse events related to research.

Metrics reflecting unanticipated, serious adverse events constitute direct measures of concrete harms experienced by human research subjects.

Table 1 shows data from 2010 through 2021 on local adverse events that were determined by IRBs to be unanticipated, serious, and related (or probably related) to research, as well as those adverse events resulting in hospitalization or death. The numbers of protocols audited each year ranged from 2,102 in 2010, to 4,249 in 2012.

Local adverse events determined to be serious, unanticipated, and related or probably related to research

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | value | % Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total active protocols | 14,944 | 16,421 | 16,602 | 16,568 | 16,244 | 15,769 | 15,699 | 15,279 | 15,258 | 15,061 | 14,637 | 15,015 | ||

| Protocols audited | 2,102 | 3,558 | 4,249 | 3,834 | 4,183 | 3,980 | 3,801 | 3,573 | 3,564 | 3,569 | 3,348 | 3,540 | ||

| Local adverse events serious, unanticipated, and research related | 25 (1.19%) | 43 (1.21%) | 17 (0.40%) | 29 (0.76%) | 13 (0.31%) | 45 (1.13%) | 15 (0.39%) | 13 (0.36%) | 39 (1.09%) | 15 (0.42%) | 18 (0.54%) | 13 (0.37%) | 0.0005 | -70% |

| Resulted in hospitalization | 11 (0.52%) | 10 (0.28%) | 5 (0.12%) | 2 (0.05%) | 0 (0.00%) | 4 (0.10%) | 2 (0.05%) | 3 (0.08%) | 9 (0.25%) | 0 (0.00%) | 3 (0.09%) | - | 0.0013 | -83% |

| Result in death | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (0.05%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.03%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.03%) | 0 (0.00%) | - | 0.7844 | N/A |

The rates of local adverse events that were determined to be unanticipated, serious, and related (or probably related) to research were low, ranging from 0.31% (i.e., 0.31 events per 100 protocols) in 2014 to 1.19% in 2010. They showed a statistically significant trend of change, decreasing from 1.19% in 2010 to 0.37% in 2021, an improvement of 70%.

The rates of these adverse events resulting in hospitalization ranged from 0.00% in 2014 and 2019, to 0.52% in 2010. They showed a statistically significant trend of change, decreasing from 0.52% in 2010 to 0.09% in 2020, an improvement of 83%.

The rates of death resulting from these adverse events were extremely low. In only 3 out of 12 years were any deaths reported (i.e., 1 or 2 deaths representing 0.03% and 0.05%), and there was no statistically significant trend of change from 2010 through 2020.

Informed consent and HIPAA authorization

Metrics reflecting failure to obtain informed consent and failure to obtain HIPAA authorization constitute direct measures of dignitary harms experienced by human research subjects.

Table 2 shows data from 2010 through 2021 on informed consent documents audited each year; informed consent documents that were not obtained; HIPAA authorizations required; and HIPAA authorizations that were not obtained.

Informed consent document and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | value | % Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total active protocols | 14,944 | 16,421 | 16,602 | 16,568 | 16,244 | 15,769 | 15,699 | 15,279 | 15,258 | 15,061 | 14,637 | 15,015 | ||

| Protocols audited | - | 15,978 | 16,546 | 16,522 | 15,730 | 15,765 | 15,629 | 15,264 | 15,233 | 14,892 | 13,985 | 12,066 | ||

| ICDs audited | 89,216 | 100,832 | 99,013 | 102,085 | 93,206 | 86,389 | 89,024 | 90.153 | 82,849 | 73,331 | 57,828 | 35,323 | ||

| Informed consent not obtained | - | - | 358 (0.36%) | 110 (0.11%) | 89 (0.10%) | 95 (0.11%) | 29 (0.03%) | 34 (0.04%) | 85 (0.11%) | 74 (0.10%) | 38 (0.07%) | 138 (0.39%) | 0.0000 | +8% |

| HIPAA authorization Required | - | 95,916 | 96,290 | 97,297 | 87,528 | 82,577 | 86,109 | 87,045 | 78,372 | 69,970 | 52,756 | 33,356 | ||

| Authorization not obtained | - | 1,383 (1.44%) | 827 (0.86%) | 1,164 (1.20%) | 783 (0.89%) | 698 (0.85%) | 486 (0.56%) | 572 (0.66%) | 518 (0.66%) | 529 (0.76%) | 535 (1.01%) | 477 (1.43%) | 0.0000 | -7% |

The numbers of informed consent documents audited ranged from 35,323 in 2021 to 102,085 in 2013. The number of informed consent documents not obtained, which included missing informed consent documents as well as informed consent documents not signed by the subjects (or legally authorized representatives), was small, ranging from 0.36% in 2012 to 0.03% in 2016. There was a statistically significant trend of change, decreasing from 2012 to 2016 and then increasing from 2016 to 2021. As a result, the percentage difference between 2012 (0.36%) and 2021 (0.39%) was only 8%.

The number of required HIPAA authorizations audited ranged from 33,356 in 2021 to 97,297 in 2013. The number of required HIPAA authorizations not obtained was small, ranging from 0.56% in 2016 to 1.44% in 2011. There was a statistically significant trend of change, decreasing from 2011 to 2016 and then increasing from 2016 to 2021. As a result, the percentage difference between 2011 (1.44%) and 2021 (1.43%) was only 7%.

Initial and continuing IRB reviews

Metrics reflecting failure to obtain required initial review and failure to obtain required continuing IRB review while continuing research activities, constitute indirect measures of dignitary harms experienced by human research subjects.

Table 3 shows data from 2010 through 2021 on protocols conducted and completed without IRB review and approval; protocols requiring IRB continuing reviews; and protocols in which investigators continued research activities during lapses in required IRB continuing review.

Institutional review board initial and continuing reviews

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | value | % Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total active protocols | 14,944 | 16,421 | 16,602 | 16,568 | 16,244 | 15,769 | 15,699 | 15,279 | 15,258 | 15,061 | 14,637 | 15,015 | ||

| Protocols audited | 2,102 | 3,558 | 4,249 | 3,834 | 4,183 | 3,980 | 3,801 | 3,573 | 3,564 | 3,569 | 3,348 | 3,540 | ||

| Conducted without required IRB approval | 1 (0.05%) | 2 (0.06%) | 1 (0.02%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.0049 | -100% |

| Protocols requiring IRB continuing review | 1,606 | 2,942 | 3,411 | 3,112 | 3,593 | - | 3,162 | 3,094 | 3,035 | 2,861 | 2,547 | 2,147 | ||

| Continued research during lapse | 2 (0.12%) | 6 (0.20%) | 4 (0.12%) | 3 (0.10%) | 11 (0.31%) | - | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 3 (0.10%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (0.08%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.0030 | -100% |

The numbers and rates of protocols conducted without IRB approval were very small, and they happened only in the first 3 years from 2010 through 2012, ranging from 0.02% in 2012 to 0.06% in 2011. After 2012, there were no research protocols conducted without IRB prior approval. Thus, from 2010 to 2021, there was a statistically significant trend of change, decreasing from 0.05% in 2010 to 0.00% in 2021, a decrease of 100%.

The numbers and rates of investigators continuing research activities during lapses in IRB continuing reviews were very small, ranging from 0.00% to 0.31% in 2014. There was a statistically significant trend of change, decreasing from 0.12% in 2010 to 0.00% in 2021, an improvement of 100%.

In this report, we proposed a set of five performance metrics to measure the effectiveness of protections for human research subjects. The first metric (unanticipated, serious adverse events related to the research) captures concrete harms actually experienced by subjects participating in research. The second and third metrics (failure to obtain informed consent and failure to obtain HIPAA authorization) capture dignitary harms actually experienced by human research subjects.

The final two metrics (failure to obtain required initial IRB review and failure to obtain required continuing IRB review while continuing research activities) constitute indirect measures of dignitary harms that may or may not have been associated with harms actually experienced by subjects. However, these two metrics are important to measure because these situations place subjects at risk of harm in the absence of objective oversight. For example, in 2016, an investigator at Southern Illinois University injected himself and at least 17 other “volunteers” with a live attenuated herpes simplex virus vaccine that he had developed without approval from the IRB, submission of an investigational new drug application (IND) to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), or obtaining informed consent from participants [ 26 ].

Ideally, all of these five human research subject protection performance metrics should have zero incidence rates, and in any case, their incidence rates should always be kept as low as possible (i.e., the lower the incidence rates, the better the human research subject protections).

The proposed performance metrics allow us to monitor trends in the effectiveness of human research protection programs in protecting human research subjects, as well as to identify areas of vulnerability for quality improvement purposes. For example, the VA data presented in this report revealed that:

● Incidence rates of all five human research subject protections performance metrics were very low (i.e., mostly less than 1%), and some were or approached 0%.

● Three of the five performance metrics showed statistically significant trends of improvement from 2010 through 2021, i.e., local adverse events that were unanticipated, serious, and related (or probably related) to research improved by 70%, those resulting in hospitalization improved by 83%, and failure to obtain required initial IRB review and failure to obtain required continuing review both improved by 100%.

● None of the five proposed human research subject protections performance metrics deteriorated from 2010 through 2021.

Thus, based on the proposed human research subject protections performance metrics, VA human research protection programs appeared effective in protecting human subjects participating in research, and that they showed improvement from 2010 through 2021.

The Common Rule was extensively revised in 2018 with the stated goal of enhancing human research subject protections and reducing burdens to investigators and IRBs [ 27 ]. The revised Common Rule was implemented on January 21, 2019. The proposed metrics for measuring human research subject protections could be used to assess whether the revised Common Rule in fact improved human research subject protections by comparing data collected before and after implementation of the revised Rule.

Limitations

One could argue that when human research is carried out without IRB review and approval, there would be no relevant records to review. However, with the general awareness of the requirement for IRB approval prior to the initiation of any nonexempt human research, it is hard for any investigators to hide human research activities that are not approved by IRBs. Unauthorized research like the above mentioned live attenuated herpes simplex virus vaccine study [ 26 ] will eventually come to light. Another potential source of research conducted without IRB approval is non-exempt research carried out (intentionally or un-intentionally) as exempt protocols without IRB approval. Institutions should periodically monitor exempt protocols to ensure that they are in fact exempt from IRB review and approval [ 28 ].

It is not clear whether high-risk research, such as cancer research protocols or significant-risk device studies, has a higher incidence of unanticipated, serious adverse events related to the research as compared to minimal risk research. If that were the case, institutions conducting more high-risk research would likely be found to be less effective in protecting human research subjects than institutions conducting mostly minimal risk research using the proposed performance metrics. Further studies are necessary to clarify this issue.

While we believe that the proposed metrics capture most concrete and dignitary harms actually experienced by research participants, there may be other metrics that better capture the effectiveness of human research subject protections. Better metrics can only be developed if more research institutions begin using the proposed metrics, or other metrics of their choice, to assess the effectiveness of their human research protection programs and publish the results. The experience gained and lessons learned through this process will eventually guide us to a set of mutually agreed upon performance metrics for measuring human research subject protections.

We proposed a set of five performance metrics for measuring human research subject protections: Unanticipated serious adverse events related to the research, failure to obtain informed consent, failure to obtain HIPAA authorization, failure to obtain required initial IRB review, and failure to obtain required continuing IRB review while continuing research activities. We used VA quality performance data collected from 2010 through 2021 to demonstrate the feasibility and utility of implementing these proposed performance metrics.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Yen B. Nguyen, Pharm.D., and all VA research compliance officers for their contributions in conducting the audits and collecting the data presented in this report.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

Clinical Research Manager

- Madison, Wisconsin

- SCHOOL OF MEDICINE AND PUBLIC HEALTH/OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY-GEN

- Partially Remote

- Staff-Full Time

- Opening at: Aug 20 2024 at 14:40 CDT

- Closing at: Sep 3 2024 at 23:55 CDT

Job Summary:

The Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology is seeking a Clinical Research Manager to join their exceptional team! The Clinical Research Manager supervises the Human Subjects core of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology to support the clinical, translational and population health research missions of the department. The CRM will manage clinical coordinators, regulatory specialists and a clinical research supervisor, and set goals and priorities for the core. The CRM will interface with faculty as they develop and conduct research projects and engage in discussions and negotiations with UnityPoint Meriter and School of Medicine and Public Health to develop workflows and structures required to conduct on-going and future human subjects research projects. This position reports directly to the Department Administrator for Research and will serve in a leadership role in the development and administration of clinical research studies, including strategic and operational planning, development, and implementation of policies and systems. This position will be the expert in the planning, executing and closing of clinical research studies for the Department of Ob/Gyn.

Responsibilities:

- 25% Plans staff implementation of protocols and on-going quality review of one or multiple, basic or moderately complex clinical research trials or programs

- 25% Analyzes research portfolios and accounts, solicits internal and external research opportunities, promotes unit capabilities, and makes recommendations to leadership for strategic program enhancements

- 10% Compiles audits and documents research data to ensure necessary compliance with institutional policies and procedures

- 5% Composes, assembles, and submits grant proposals and protocols according to applicable rules and regulations

- 10% Exercises supervisory authority, including hiring, transferring, suspending, promoting, managing conduct and performance, discharging, assigning, rewarding, disciplining, and/or approving hours worked of at least 2.0 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees

- 5% Develops and monitors the program budget; and reviews and approves expenditures

- 10% Builds research infrastructure across clinical environments to improve processes, communication, and efficient clinical research operations.

- 5% Serves as the point of contact for collaborators outside of the department for potential research collaborations, operational questions, and improvements.

- 5% Monitors compliance of all clinical trial regulations while maintaining security and privacy.

Institutional Statement on Diversity:

Diversity is a source of strength, creativity, and innovation for UW-Madison. We value the contributions of each person and respect the profound ways their identity, culture, background, experience, status, abilities, and opinion enrich the university community. We commit ourselves to the pursuit of excellence in teaching, research, outreach, and diversity as inextricably linked goals. The University of Wisconsin-Madison fulfills its public mission by creating a welcoming and inclusive community for people from every background - people who as students, faculty, and staff serve Wisconsin and the world. For more information on diversity and inclusion on campus, please visit: Diversity and Inclusion

Required Bachelor's Degree Preferred focus in business healthcare or related field

Qualifications:

Required Qualifications: - Minimum two years of experience as a clinical research coordinator. - Minimum two year of experience as a program manager/supervisor & managing teams. - Experience and knowledge in setting up clinical studies and all required components (staffing, regulatory, budget, etc.). - Experience and knowledge of investigator initiated trials, industry sponsored trials (clinical, basic and translational). - Experience in developing workflows/protocols for human subjects recruitment and tissue collection; data collection; study initiation and tracking, annual reports. - Experience with REDCap, ONCORE, any other regulatory programs that can track research/regulatory procedures. - Exposure to budgeting, forecasting, and accounting in healthcare or a research environment. - Exposure to clinical trial agreement development and negotiation process. - Exposure to pre-award or post-award administration related to various extramural sponsors.

Full Time: 100% This position may require some work to be performed in-person, onsite, at a designated campus work location. Some work may be performed remotely, at an offsite, non-campus work location.

Appointment Type, Duration:

Ongoing/Renewable