An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Miscarriage matters: the epidemiological, physical, psychological, and economic costs of early pregnancy loss

Affiliations.

- 1 Division of Biomedical Sciences, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Warwick, UK; Tommy's National Centre for Miscarriage Research, University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust, Coventry, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Tommy's National Centre for Miscarriage Research, Institute of Metabolism and Systems Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK.

- 3 University of Illinois Recurrent Pregnancy Loss Program, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

- 4 Warwick Clinical Trials Unit, University of Warwick, Warwick, UK.

- 5 Division of Biomedical Sciences, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Warwick, UK; Tommy's National Centre for Miscarriage Research, University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust, Coventry, UK.

- 6 Tommy's Charity, Laurence Pountney Hill, London, UK.

- 7 CONICET, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Instituto de Química Biológica de la Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales IQUIBICEN, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- 8 Department of Biology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA.

- 9 Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

- 10 Tommy's National Centre for Miscarriage Research, Imperial College London, London, UK.

- 11 Centre for Recurrent Pregnancy Loss of Western Denmark, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Aalborg University Hospital, Aalborg, Denmark.

- 12 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Nagoya City University, Nagoya, Japan.

- PMID: 33915094

- DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00682-6

Miscarriage is generally defined as the loss of a pregnancy before viability. An estimated 23 million miscarriages occur every year worldwide, translating to 44 pregnancy losses each minute. The pooled risk of miscarriage is 15·3% (95% CI 12·5-18·7%) of all recognised pregnancies. The population prevalence of women who have had one miscarriage is 10·8% (10·3-11·4%), two miscarriages is 1·9% (1·8-2·1%), and three or more miscarriages is 0·7% (0·5-0·8%). Risk factors for miscarriage include very young or older female age (younger than 20 years and older than 35 years), older male age (older than 40 years), very low or very high body-mass index, Black ethnicity, previous miscarriages, smoking, alcohol, stress, working night shifts, air pollution, and exposure to pesticides. The consequences of miscarriage are both physical, such as bleeding or infection, and psychological. Psychological consequences include increases in the risk of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide. Miscarriage, and especially recurrent miscarriage, is also a sentinel risk marker for obstetric complications, including preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, placental abruption, and stillbirth in future pregnancies, and a predictor of longer-term health problems, such as cardiovascular disease and venous thromboembolism. The costs of miscarriage affect individuals, health-care systems, and society. The short-term national economic cost of miscarriage is estimated to be £471 million per year in the UK. As recurrent miscarriage is a sentinel marker for various obstetric risks in future pregnancies, women should receive care in preconception and obstetric clinics specialising in patients at high risk. As psychological morbidity is common after pregnancy loss, effective screening instruments and treatment options for mental health consequences of miscarriage need to be available. We recommend that miscarriage data are gathered and reported to facilitate comparison of rates among countries, to accelerate research, and to improve patient care and policy development.

Copyright © 2021 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

Declaration of interests We declare no competing interests.

- Miscarriage: worldwide reform of care is needed. The Lancet. The Lancet. Lancet. 2021 May 1;397(10285):1597. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00954-5. Epub 2021 Apr 27. Lancet. 2021. PMID: 33915093 No abstract available.

- Making miscarriage matter. Chong K, Li W, Roberts I, Mol BW. Chong K, et al. Lancet. 2021 Aug 28;398(10302):743-744. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01379-9. Lancet. 2021. PMID: 34454666 No abstract available.

- Making miscarriage matter. Lucas S, Knight M, Lucas N, Rodger A. Lucas S, et al. Lancet. 2021 Aug 28;398(10302):744-745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01381-7. Lancet. 2021. PMID: 34454667 No abstract available.

- Making miscarriage matter. Agampodi S, Hettiarachchi A, Agampodi T. Agampodi S, et al. Lancet. 2021 Aug 28;398(10302):745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01426-4. Lancet. 2021. PMID: 34454668 No abstract available.

Similar articles

- Subsequent pregnancy outcomes after second trimester miscarriage or termination for medical/fetal reason: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Patel K, Pirie D, Heazell AEP, Morgan B, Woolner A. Patel K, et al. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2024 Mar;103(3):413-422. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14731. Epub 2023 Nov 30. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2024. PMID: 38037500 Free PMC article. Review.

- Risk of placental dysfunction disorders after prior miscarriages: a population-based study. Gunnarsdottir J, Stephansson O, Cnattingius S, Akerud H, Wikström AK. Gunnarsdottir J, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jul;211(1):34.e1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.041. Epub 2014 Feb 1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014. PMID: 24495667

- Spontaneous first trimester miscarriage rates per woman among parous women with 1 or more pregnancies of 24 weeks or more. Cohain JS, Buxbaum RE, Mankuta D. Cohain JS, et al. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017 Dec 22;17(1):437. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1620-1. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017. PMID: 29272996 Free PMC article.

- Do women with recurrent miscarriage constitute a high-risk obstetric population? Fawzy M, Saravelos S, Li TC, Metwally M. Fawzy M, et al. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2016 Apr;19(1):9-15. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2016.1142214. Epub 2016 Mar 22. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2016. PMID: 27002424

- Pregnancy complications and later life women's health. McNestry C, Killeen SL, Crowley RK, McAuliffe FM. McNestry C, et al. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2023 May;102(5):523-531. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14523. Epub 2023 Feb 17. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2023. PMID: 36799269 Free PMC article. Review.

- From bench to in silico and backwards: What have we done on genetics of recurrent pregnancy loss and implantation failure and where should we go next? Gomes FG, Boquett JA, Kowalski TW, Bremm JM, Michels MS, Pretto L, Rockenbach MK, Vianna FSL, Schuler-Faccini L, Sanseverino MTV, Fraga LR. Gomes FG, et al. Genet Mol Biol. 2024 Aug 26;46(3 Suppl 1):e20230127. doi: 10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2023-0127. eCollection 2024. Genet Mol Biol. 2024. PMID: 39186710 Free PMC article.

- Effect of subchorionic hematoma on first-trimester maternal serum free β-hCG and PAPP-A levels. Akay A, Reis YA, Şahin B, Öncü AK, Obut M, İskender C, Çelen Ş. Akay A, et al. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2024 Jul 26;46:e-rbgo66. doi: 10.61622/rbgo/2024rbgo66. eCollection 2024. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2024. PMID: 39176201 Free PMC article.

- Clinical predictive value of pre-pregnancy tests for unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion: a retrospective study. Wang J, Li D, Guo Z, Ren Y, Wang L, Liu Y, Kang K, Shi W, Huang J, Liao S, Hao Y. Wang J, et al. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024 Aug 7;11:1443056. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1443056. eCollection 2024. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024. PMID: 39170044 Free PMC article.

- Depression after pregnancy loss: the role of the presence of living children, the type of loss, multiple losses, the relationship quality, and coping strategies. Balle SR, Nothelfer C, Mergl R, Quaatz SM, Hoffmann S, Hoffmann H, Allgaier AK, Eichhorn K. Balle SR, et al. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2024;15(1):2386827. doi: 10.1080/20008066.2024.2386827. Epub 2024 Aug 14. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2024. PMID: 39140607 Free PMC article.

- Trends, spatiotemporal variation and decomposition analysis of pregnancy termination among women of reproductive age in Ethiopia: Evidence from the Ethiopian demographic and health survey, from 2000 to 2016. Tebeje TM, Seifu BL, Seboka BT, Mare KU, Chekol YM, Tesfie TK, Gelaw NB, Abebe M. Tebeje TM, et al. Heliyon. 2024 Jul 14;10(14):e34633. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34633. eCollection 2024 Jul 30. Heliyon. 2024. PMID: 39130402 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

- Cited in Books

Grants and funding

- 212233/Z/18/Z/WT_/Wellcome Trust/United Kingdom

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

Other Literature Sources

- The Lens - Patent Citations

- scite Smart Citations

- Genetic Alliance

- MedlinePlus Consumer Health Information

- MedlinePlus Health Information

Research Materials

- NCI CPTC Antibody Characterization Program

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 7, Issue 3

- Experience of miscarriage: an interpretative phenomenological analysis

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- S Meaney 1 , 2 ,

- P Corcoran 1 ,

- N Spillane 2 ,

- K O'Donoghue 2 , 3

- 1 National Perinatal Epidemiology Centre, University College Cork, Ireland

- 2 Pregnancy Loss Research Group, Dept. of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University College Cork, Ireland

- 3 The Irish Centre for Fetal and Neonatal Translational Research (INFANT), University College Cork, Ireland

- Correspondence to Dr S Meaney; s.meaney{at}ucc.ie

Objective The objective of the study was to explore the experiences of those who have experienced miscarriage, focusing on men's and women's accounts of miscarriage.

Design This was a qualitative study using a phenomenological framework. Following in-depth semistructured interviews, analysis was undertaken in order to identify superordinate themes relating to their experience of miscarriage.

Setting A large tertiary-level maternity hospital in Ireland.

Participants A purposive sample of 16 participants, comprising 10 women and 6 men, was recruited.

Results 6 superordinate themes in relation to the participant's experience of miscarriage were identified: (1) acknowledgement of miscarriage as a valid loss; (2) misperceptions of miscarriage; (3) the hospital environment, management of miscarriage; (4) support and coping; (5) reproductive history; and (6) implications for future pregnancies.

Conclusions One of the key findings illustrates a need for increased awareness in relation to miscarriage. The study also indicates that the experience of miscarriage has a considerable impact on men and women. This study highlights that a thorough investigation of the underlying causes of miscarriage and continuity of care in subsequent pregnancies are priorities for those who experience miscarriage. Consideration should be given to the manner in which women who have not experienced recurrent miscarriage but have other potential risk factors for miscarriage could be followed up in clinical practice.

- QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

- pregnancy loss

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011382

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study uses interpretative phenomenological analysis in order to interpret the experience of miscarriage.

Much of the research in relation to pregnancy loss is focused on women's experience. Purposive sampling was undertaken to ensure that both women's and men's experiences were included in this study.

Participants from this study were drawn from a large tertiary maternity hospital with a dedicated pregnancy loss clinic and it may be possible that their experiences may differ from those who attend a hospital where such a clinic is not available to them.

Miscarriage is the most common adverse outcome in pregnancy. This study highlights the need for the provision of appropriate clinical information as well as supportive information when counselling individuals who experienced miscarriage.

Introduction

Improvements in the quality of care provided during pregnancy have led to substantial reductions in perinatal and maternal mortality as well as a reduction in other adverse pregnancy outcomes. 1 However, these advances have had little effect on the high rate of miscarriage with between 20% and 30% of pregnancies ending in miscarriage. 1 , 2 Until now, much of the research has aimed to identify potential risk factors as the underlying aetiology of miscarriage is not well understood. 2

Studies indicate the need for familial and social support following miscarriage as it can be an extremely painful and upsetting experience, 3 , 4 with some women experiencing medical complications. 5 , 6 Quantitative studies indicate that the experience of miscarriage can negatively impact on the men's and women's psychological well-being. 4 , 7–14 These studies also report that the high levels of stress and anxiety experienced 7–9 can endure for 6–12 months following miscarriage. 8

In contrast, an interventional study in the USA examined the changes of women's feeling over the course of year following miscarriage. Swanson et al 15 found that women's responses recorded at 1 year were not significantly different from those recorded at 6 weeks. Considering the high incidence of miscarriage and the reported impact on the emotional well-being of people, there are comparatively few studies that have qualitatively examined the experience of miscarriage. Of these, most studies focused on the women's experience of miscarriage 3 , 16–18 whereby the male experience has been reported based on the women's perspective. 16 , 19 Our study builds on these findings as it aimed to explore the experiences of people who have experienced miscarriage. The purpose of this study was to focus on men's and women's accounts of miscarriage. Through a qualitative analysis, the objective of the study was to gain detailed insight into their expectations of pregnancy as well as their experience of miscarriage diagnosis and management.

An interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) was undertaken as this approach has its theoretical foundations in phenomenology. 20–22 Phenomenology examines perceptions and engages with the way individuals reflect on the experiences they deem significant in their lives. 21 Researchers who engage in IPA acknowledge how experience is subjective and is therefore only accessible through interpretation. 20 IPA has an ideographic approach which allows the researcher to rigorously explore how these experiences may affect a person. 20 IPA has increasingly been used in healthcare research as its ideographic approach facilitates researchers to rigorously explore how specific phenomena may affect a patient and consequently will impact on patient care. 20

The study took place in a large tertiary-level Irish maternity hospital. The sample was initially recruited from a list of women who had previously participated in a prospective cohort study regarding miscarriage 23 and agreed to be contacted for future research. It is important to note that there are geographical variations for the definition of miscarriage. For the purposes of this study, miscarriage was defined as any pregnancy loss which occurred before 24 weeks gestation in a fetus weighing <500 g. Participants were eligible for the study if they were aged 18 years and older and had experienced one or more miscarriages. Letters were sent to invite women and their partners to participate in the present study by the primary author. If an opt-out form was not returned, the primary author made contact to provide more detailed information about the study. Over the course of the study, six opt-out forms were returned. Three participants were recruited using snowballing techniques, through contact with the Miscarriage Association of Ireland and/or through the bereavement and loss hospital team. Information on the study was forwarded to them and they made contact with the primary author to become involved in the study. None of the participants were known to the researcher.

The primary author recruited until data saturation was met. The final sample consisted of 16 participants (10 female and 6 male), 4 of whom were couples ( table 1 ). All the participants signed an informed consent and were interviewed individually, by the primary author (an experienced female qualitative researcher), using a semistructured interview schedule ( table 2 ). All the interviews were conducted in a room onsite in the maternity hospital or a location convenient to the participant, with the exception of one interview that was undertaken by telephone under participant request. Each interview was digitally recorded and contemporaneous notes were taken immediately after each interview. The average interview was 43 min, ranging from 28 to 69 min in length.

- View inline

Overview of the sample

Overview of the semistructured interview schedule

The IPA involved: first listening and re-reading the interviews a number of times to ensure that a general sense of the participants' accounts were acquired. Second, emergent themes were initially identified which were then refined as similar themes were clustered together and subordinate and superordinate themes were identified. Patterns and connections across each individual transcript were examined. Finally, a master table of themes was created after each transcript was integrated into the final analysis. All analyses were carried out using Nvivo V.10 software (QSR International, Doncaster, Australia) by the primary author, a health sociologist. The analyses were then presented to the co-authors for review.

Analysis of the data indicated six superordinate themes in relation to the participant's experience of miscarriage: acknowledgement of miscarriage as a valid loss, misperceptions of miscarriage, the hospital environment, management of miscarriage, support and coping, reproductive history and implications for future pregnancies.

Acknowledgement of miscarriage as a valid loss

“But the miscarriage itself, I'd say it was until then…and the whole discussion became a very public thing…it was only at that stage that I started to move on from it and that would have been five years, five years later and it was always something that would of upset me…it is hard to know what you are grieving for in a way because it is fleeting, you know the whole experience of being pregnant and then not being pregnant and thinking if I didn't remember this baby then who would.” (P15, male, two miscarriages)

“At this stage I think we had attended a couple of the, of the October, the ahhh annual ahhhh [prompt from interviewer; the annual service of remembrance] yeah. And again they are huge out pouring of grief, and of joy for life, but of grief. The people there and the support, but the fact that there are children and parents and grandparents, it just gives a sense that look it doesn't matter what age you are, doesn't matter how wealthy you are, doesn't matter what colour you are, we have all experienced this in our own way and we are all here today to remember that. And, I think for me, that, that was [pause] I haven't missed one yet and I'll still be going for another while yet. You know, that's a lovely outreach and very important.” (P13 male, two miscarriages)

“What I think happens, from my own experience, is I don't think it is recognised enough. Like cancer is recognised, god help us we have all had it and all those things. But a loss, it's a different loss when it's a child. They're still a child, they may not be grown but they're still a child” (P1, female, two miscarriages)

The acknowledgement of the loss through miscarriage, both by people and through ritual, was of importance. Participants discussed marking or remembering their loss in a variety of ways such as keeping a diary, writing of poems and songs or through the organisation of a funeral or similar ceremony. Some participants spoke of the importance of rituals particularly around the anniversary of the miscarriage in order to continue to acknowledge their loss. A number of participants remarked about the significance of attending the annual service of remembrance, which is organised by the hospital.

Misperceptions of miscarriage

“I got spotting and I thought surely it's not going to happen again, cause they [people] always say one spontaneous [miscarriage] but you never (pause) but I think with miscarriage people just don't talk about it and they just don't think that it happens to everybody and they don't think it is as common as it is until you talk to other people about it. So I think the perception I would have had was if you had one you're not really likely to have another, that's what I thought.” (P3, female, four miscarriages)

“A friend of mine in work is pregnant and it's her first pregnancy and she's not kind of as worried as I am for her. She is oblivious and naïve and while I'm thinking ‘oh god’ she is saying ‘it's fine’.” (P7, female, two miscarriages)

“Well when I did have the miscarriage and I said it to people, everyone says ‘oh you know I had one’ and it all comes out from the woodwork and em everyone knows someone who has had a miscarriage. It's so common how could you not but people generally don't talk about it…you don't have the knowledge…people need to know that this can happen.” (P11, female, three miscarriages)

The hospital environment and management of miscarriage

When the participants spoke about how they were treated in the hospital, they remarked about how divergent an experience it was. The participants stated that any negative experiences in the hospital were related to the administration and/or physical design of the hospital specifically relating to the emergency department and the general clinics. When the women were miscarrying, they first attended the emergency department and found it difficult to be sitting in the waiting area surrounded by women attending with varying symptoms. This was considered one of the hardest aspects of the miscarriage experience as they felt they could not express any emotion (eg, anger or upset) relating to their loss, as they did not wish to distress the other pregnant women.

“We came straight up here [the maternity hospital] and we went into the emergency place downstairs and we were seen straight away. But there were other patients and staff behind curtains, we were behind ours waiting on the doctor to come round. And there were nurses in there chatting and they were laughing and chatting and jokes and stuff, which they are entitled to have…but I was there with [husband] and we were worried sick that we were losing our baby and the doctor came in and she went through all the things and said ‘No, I can't find a fetal heartbeat, it's gone’. Well, I started roaring crying, I was so upset but all the life was happening all around us, carrying on you know happily in behind the curtains…it was absolutely horrendous. But they organised for me to come back to the early pregnancy clinic, you know I didn't have to speak to anybody we just left the hospital [pause] that was hard.” (P8, female, seven miscarriages)

“That was hugely traumatic, cause em, I didn't miscarry the same as the last time it just went on and on and on. I was in and out of here [maternity hospital] every second day for blood tests. The first day they went up a bit and then they went down a bit and then it was kind of, like, and it was just two weeks really of turmoil.” (P4, female, three miscarriages)

“I woke up an hour later and I just completely haemorrhaged and I passed out a couple of times. Then I got in the bath and em, I was saying god people should warn people or prepare people if they are going to have miscarriages, cause I didn't know what was happening to me. And em what I excreted was unbelievable cause I was 12 weeks. And I started vomiting and I passed out again and then he rang the hospital. I tried talking to the hospital but I couldn't get the words out I was so weak at this point, you know, and they told me to come straight in. So I did and they killed me [slang: were annoyed with me] when I got in cause they said I should've called the ambulance.” (P3, female, three miscarriages)

“The first and the last were spontaneous and the last two I had to take medication but it would of happened inevitably but I, I just wanted to speed up [the miscarriage]…” (P5, female, four miscarriages)

Participants experienced anxiety about attending the hospital to get tests over a number of days to confirm the loss of their baby. This was relatively impractical for some with work commitments, but was also difficult as they did not want to reattend the hospital to face the inevitable diagnosis. Many of the women expressed how they had suspected that something was wrong but had no knowledge of what to expect or what is considered normal while miscarrying. Those who miscarried at a later gestation discussed how they were wholly unprepared for the extent of the bleeding when they miscarried ( box 3 ). When women had a choice, most chose to have some form of medical intervention. A number of factors influenced the decision to choose to intervene with women citing other commitments such as having to take care of other children in the family.

Support and coping

Keeping busy helped participants cope with their loss; this was particularly evident in the participants who already had children. Participants were hesitant to receive formal support by way of counselling and most opted for support from family, friends and/or support groups instead. Men felt that their primary role was to support their partners through the loss and, at times reluctantly, while planning subsequent pregnancies. During subsequent pregnancies, the participants disclosed that high levels of anxiety were experienced. They spoke of how they navigated through the pregnancy focusing on specific gestational weeks as goals, including exceeding the gestation they had experienced their miscarriage(s) at, as well as those coinciding with clinic appointments at the maternity hospital. Many of the participants detailed how these actions meant they could not fully enjoy the experience of being pregnant.

“I was upset for a good while after but I had the other three [children] to keep me going [slang: busy] with school and everything…I had the D&C the same week as my daughter's communion, so I had to just go ahead and get on with things you know, I had to be happy for her.” (P10, female, two miscarriages)

“I'd say we were slightly different in that if we had called it a day at the end of number seven, we both would have been extremely disappointed but you know I think, em, it's more about protection I suppose, I didn't want to have to go through it again. The decision was extremely difficult, now I mean [wife] was very much in favour of going forward and trying again, em, I would have been a bit more reticent I suppose, em a bit more, you know, a bit more nervous about it. Obviously she had major concerns but you I think, I think it was a case of a tough decision but we just went for it.” (P9, male, seven miscarriages)

“I love babies and if someone was to say on Friday that you are pregnant and you are going to have to have the baby tomorrow, I would say yeah that's great but I just can't do the, the nine months of worrying.” (P7, female, two miscarriages)

“I went up to the [early pregnancy clinic] and they said ‘the next time you get pregnant call us here and come in and we will do a scan, we will do an early scan, we will give you that reassurance’. That made a huge difference, it made a huge difference because it felt like ok someone is not saying ‘yeah, yeah, yeah move it along, move it along, next person’ someone is actually saying ‘we care about you, we know this is hard and the next time you get pregnant we know it's going to be distressful for the first few weeks so come in and we will give you scans’. And they were so good about it and when I did get pregnant it was one of the first calls I did make.” (P12, female, two miscarriages)

Reproductive history and implications for future pregnancies

“We already had a loss, I know they were two, two different losses but I was thinking not again, what is going on, is there something wrong with me, am I ever going to have children.” (P1, female, two miscarriages)

“One of the things that I asked for was an appointment with [the specialist in pregnancy loss]to have tests done to see why I was having the miscarriages but I was told I would have to have 3 miscarriages before they would see me and I was kind of thinking, do they not take age into account? You know, you have to have three and I think two is an adequate level at my age. If I was in my twenties maybe you'd manage the three but not at my age.” (P4, female, three miscarriages)

Medical investigations, such as karyotyping, are not offered to women unless they have experienced recurrent miscarriage (three consecutive miscarriages). 24 Participants expressed frustration that these tests were not offered to them following a second miscarriage. This dissatisfaction was heightened in women who felt that other risk factors, such as advancing maternal age, should be considered ( box 5 ).

The findings of this qualitative study indicate that the experience of miscarriage has a considerable impact on men and women. Findings from this study support what has been reported by others, that there is a need for increased awareness in relation to the frequent occurrence of miscarriage. Miscarriage is a common occurrence, yet as revealed by these participants it is not until a miscarriage was experienced that the participants were made aware of these high rates. A study from the USA also indicated that people believe that miscarriage is a rare complication of pregnancy. 25 The participants from this study believed that improvement of information provision would be beneficial in allowing individuals to better prepare for the possibility that their pregnancy could end in miscarriage and, if it does occur, that support is available.

Second, given that a cause cannot be determined in as many as 50% of miscarriages, it was felt that having this information in advance may alleviate some of the guilt experienced. Participants emphasised that such information provision should also focus on the physical aspects of miscarrying. These findings mirror those of Moohan et al , 26 whereby women felt unprepared when miscarrying spontaneously and were questioning of whether what they had experienced was normal. Wong et al 27 support this finding by detailing how miscarriage may be a physically traumatic event as women may experience considerable and sudden pain, loss of blood and may need to be hospitalised. Similar to the longitudinal study by Côté-Arsenault, 28 the participants in this study indicated how pregnancy following miscarriage was stressful. There is a need for improved communication between healthcare professionals and patients to better counsel patients through the miscarriage and provide reassurance in subsequent pregnancies.

One coping strategy adopted by men and women was focusing on commitments, particularly taking care of other children in the family. In a review of the literature on grief following miscarriage, Brier states that having living children has also been used as an indicator for the importance attached to the pregnancy. This belief is based on the assumption that the absence of living children is associated with a relatively greater desire for children. 29 Wong et al 27 also highlight how, given this belief, it is also assumed that women with children will be less emotionally distressed and are less likely to receive emotional support from nursing staff. In contrast, the findings from this study illustrated that these participants were affected emotionally and did go through a grieving process irrespective of gestation of the pregnancy loss or whether they had living children or not. The findings also indicated the importance that healthcare professionals acknowledge miscarriage and how appreciative participants were of the support given to them.

It has been documented that men and women grieve differently following miscarriage in the literature, 30 , 31 and these findings are also reflected in the accounts of the participants in this study. Similar to Johnson and Puddifoot, 31 the men in this study indicated that they were less likely to openly discuss the miscarriage unless prompted by another person with a similar experience. This was also the case with discussing the impact of the miscarriage on them with their partners with the men identifying their primary role as that of a support to their partner. However, as outlined by Brier, 29 this could suggest differences in the general expression of emotion and grief rather than affective reactions to miscarriage. Although the men in this study did not actively seek out support, they did reiterate that certain experiences and rituals were helpful for their grieving process as they allowed them to mark and remember their loss.

Participants in this study were reasonably satisfied with the care provided to them by the hospital. However, a number of shortcomings with the system were identified. When miscarrying, the first contact with the maternity hospital was with the emergency room. It was felt that waiting for extended periods of time in an area with other pregnant women was particularly difficult and a situation which hospital management should be more sensitive to. Wong et al 27 outlined that in previous studies women believed that medical staff do not consider miscarriage as either important or an emergency and considered medical staff insensitive and unsympathetic about accommodation. Our findings build on these results whereby participants identified this insensitivity to be as a result of the hospital setting rather than medical staff. Participants were appreciative of staff, especially those whom they considered to be knowledgeable and those who displayed understanding and compassion. The dedicated early pregnancy clinic was an environment they believed could be further developed to enhance the care currently provided to women when they are miscarrying.

Consistent with a number of other studies, 1 , 4 , 27 all the participants expressed a desire to determine the cause of the miscarriage. Participants expressed dissatisfaction that they were ineligible to have tests to fully investigate the cause of their miscarriage as they had not experienced the requisite three consecutive miscarriages. In our study, this perceived inadequacy in service provision was amplified in women of advancing maternal age. As Brier 29 outlines, maternal age can potentially influence an individual's goals with regard to childbearing. Advancing maternal age in combination with a number of losses experienced by a woman may impact on the duration and intensity of grief experienced. The women in this study expressed dissatisfaction with their ineligibility for investigations, maintaining that staff should appreciate that although they had not experienced recurrent miscarriage, there were other risk factors, such as their age, to be considered.

As part of the analysis, it is important to consider any factors which may influence the results. The participants in the study all made reference to the dedicated early pregnancy loss clinic. This clinic is staffed by a dedicated pregnancy loss team. Such a dedicated clinic is not available in all hospitals. Thus, the presence of such a team in the hospital may have raised awareness about miscarriage among other medical staff and influenced how they cared for the participants sampled here. It is important to note, that although a qualitative methodology was deemed appropriate for this study, the findings of such studies are context-specific. The experiences of the women and men in this study may or may not reflect the experiences of those who attend other units with differing resources and practices. Notwithstanding these limitations, given the level of agreement with other studies, we feel that these results add additional insight into the experiences of miscarriage.

Conclusions

This study highlights that a thorough investigation of the underlying causes of miscarriage and continuity of care in subsequent pregnancies are priorities for those who experience miscarriage. The provision of appropriate clinical information as well as supportive information when counselling individuals who are experiencing a miscarriage is important. Consideration should be given to the manner in which women who have not experienced recurrent miscarriage but have other potential risk factors for miscarriage could be followed up in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the participants for participating in the study and giving of their time freely.

- Simmons RK ,

- Maconochie N , et al

- Maconochie N ,

- Prior S , et al

- Adolfsson A

- Peloggia A ,

- Grimes D , et al

- Saraiya M ,

- Shulman H , et al

- Neugebauer R

- Nikcevic AV ,

- Tunkel SA ,

- Kuczmierczyk AR , et al

- Geller PA ,

- Maruyama T ,

- Koizumi T , et al

- Hiley A , et al

- Serrano F ,

- Swanson KM ,

- Jolley SN , et al

- Gerber-Epstein P ,

- Leichtentritt RD ,

- Benyamini Y

- Glasser JK ,

- Sundaram ME

- Wojnar DM ,

- Adolfsson AS

- Karmali ZA ,

- Powell SH , et al

- Biggerstaff D ,

- Thompson AR

- Flowers P ,

- Lutomski JE ,

- Corcoran P , et al

- ↵ RCOG Green-top Guideline No. 17 . The investigation and treatment of couples with recurrent first-trimester and second-trimester miscarriage . Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists , April 2011 .

- Friedenthal J , et al

- Crawford TJ ,

- Gask L , et al

- Côté-Arsenault D

- Willner H ,

- Deckardt R , et al

- Johnson MP ,

- Puddifoot JE

Twitter Follow Sarah Meaney @sarahmeaney5

Contributors SM and KOD contributed to and were responsible for the conception and design of the study. SM and NS were responsible for data collection. SM was responsible for transcription, data analysis and the initial drafting of the article. SM, PC, NS and KOD contributed to revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Funding This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Ethics approval Ethical approval for the study was provided by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals (CREC; Reference: ECM 4 (iii) 10/01/12).

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement No additional data are available.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 19 November 2018

University students’ awareness of causes and risk factors of miscarriage: a cross-sectional study

- Indra San Lazaro Campillo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7281-8424 1 , 2 ,

- Sarah Meaney 1 , 2 ,

- Jacqueline Sheehan 1 ,

- Rachel Rice 1 &

- Keelin O’Donoghue 1

BMC Women's Health volume 18 , Article number: 188 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

7687 Accesses

9 Citations

15 Altmetric

Metrics details

Spontaneous miscarriage is the most common complication of pregnancy, occurring in up to 20% of pregnancies. Despite the prevalence of miscarriage, little is known regarding peoples’ awareness and understanding of causes of pregnancy loss. The aim of this study was to explore university students’ understanding of rates, causes and risk factors of miscarriage.

A cross-sectional study including university students. An online questionnaire was circulated to all students at the University College Cork using their university email accounts in April and May 2016. Main outcomes included identification of prevalence, weeks of gestation at which miscarriage occurs and causative risk factors for miscarriage.

A sample of 746 students were included in the analysis. Only 20% ( n = 149) of students correctly identified the prevalence of miscarriage, and almost 30% ( n = 207) incorrectly believed that miscarriage occurs in less than 10% of pregnancies. Female were more likely to correctly identify the rate of miscarriage than men (21.8% versus 14.5%). However, men tended to underestimate the rate and females overestimate it. Students who did not know someone who had a miscarriage underestimated the rate of miscarriage, and those who were aware of some celebrities who had a miscarriage overestimated the rate. Almost 43% ( n = 316) of students correctly identified fetal chromosomal abnormalities as the main cause of miscarriage. Females, older students, those from Medical and Health disciplines and those who were aware of a celebrity who had a miscarriage were more likely to identify chromosomal abnormalities as a main cause. However, more than 90% of the students believed that having a fall, consuming drugs or the medical condition of the mother was a causative risk factor for miscarriage. Finally, stress was identified as a risk factor more frequently than advanced maternal age or smoking.

Although almost half of the participants identified chromosomal abnormalities as the main cause of miscarriage, there is still a lack of understanding about the prevalence and most important risk factors among university students. University represents an ideal opportunity for health promotion strategies to increase awareness of potential adverse outcomes in pregnancy.

Peer Review reports

Miscarriage is one of the most common complications in pregnancy [ 1 ]. It is estimated that one out of four clinically recognised pregnancies will end in miscarriage during the first-trimester, and approximately 1% of pregnant women will experience a second-trimester miscarriage [ 2 ]. Despite the prevalence of miscarriage, 50% are attributed to chromosomal abnormalities [ 3 ], and a considerable percentage are classified as unexplained [ 4 ]. Therefore, identifying risk factors and effective interventions to prevent miscarriage has become a priority in the medical and scientific community [ 5 ]. Well-known risk factors include advanced maternal and paternal age, heavy smoking, alcohol consumption, infertility and previous miscarriage [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ].

Preconception health care aims to identify and increase awareness to reduce risk factors before pregnancy that might affect the future maternal, child and family health [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. An effort has been made to develop effective intervention plans and to include preconception risk factors in prenatal prevention programs internationally [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. One of the main recommendations is to promote effective preconception health care interventions to develop curricula of preconception risk factors at undergraduate and postgraduate level [ 15 ]. Insight into students’ awareness of miscarriage might help to assess the effectiveness of preconception care education at a university level, but also to highlight the gaps of knowledge among this targeted population. Therefore, a cross-sectional study was conducted to explore university students’ understanding of prevalence, causes and risk factors of miscarriage.

Study design and data source

A cross sectional study was carried at University College Cork (UCC). Cork is one of the three cities in the Republic of Ireland with the highest full-time enrolments in the academic year 2016/2017 [ 19 ]. UCC currently has 20,000 full-time students of whom 14,000 are undergraduate [ 19 ]. It has over 3000 international students from 100 countries around the world. There are over 120 degree and professional programmes in Medicine, Dentistry, Pharmacy, Nursing and the Clinical Therapies, along with the Humanities, Business, Law, Architecture, Science, Food and Nutritional Sciences, available at UCC. Students were asked to select their area of study at UCC from a list of six options. For the purpose of this study, this list was grouped into four categories in accordance with the organisation of the Colleges within the University (i.e. The College of Medicine and Health, The College of Arts and Social Science, The College of Engineering & Food Science and The College of Business and Commerce & Law) [ 20 ]. For example, the College of Medicine and Health includes the Schools of Medicine, Dental School, Clinical Therapies, Nursing and & Midwifery, Pharmacy and Public Health.

An online questionnaire was circulated to all students at UCC using their university email accounts, in April and May 2016. The questionnaire was compiled using SurveyMonkey®, which is a user-friendly site to develop and administer online surveys. The questionnaire was anonymous and voluntary. An informed consent form explaining the objectives of the survey had to be completed before accessing the questionnaire. The main questionnaire consisted of twenty-six questions utilised to assess students’ understanding of the topic of miscarriage. Topics included general demographic and educational characteristics (i.e. sex, age, marital status, discipline and level of study), general knowledge and risk factors for miscarriage (i.e. agree, disagree and unsure of both well-known and spurious risk factors), identification of previous experience of miscarriage among themselves or their partners, and awareness of family member, friends or a celebrity who had a miscarriage. Students were asked to select the most common causes of miscarriage from a list of six options including lifestyle of mother (i.e. smoking and alcohol), medical condition or medical problem with the mother; genetic problem with the baby; psychological problems during pregnancy (i.e. stress, depression) and incident during pregnancy (i.e. fall, injury, accident). In addition, students were asked to provide rates of miscarriage in Ireland (i.e. “ In your opinion, what percentage of pregnancies in Ireland ends in a miscarriage? Please insert a number anywhere from 0 to 100 %”) and weeks of gestation at which miscarriage occurs (“ when can a miscarriage occur? Between week “x” to week “x” of a pregnancy ”).

Definitions of miscarriage vary significantly between countries and jurisdictions [ 21 ]. For the purposes of this study, miscarriage is defined as the spontaneous demise of a pregnancy from the time of conception up to 24 completed weeks of gestation [ 22 , 23 , 24 ]. This study also reported the number of students who were only aware of first trimester miscarriage, which is defined as the loss of a pregnancy up to 12 weeks of gestation [ 22 , 23 , 24 ]. It is estimated that approximately one fifth of clinical pregnancies will end in a miscarriage in Ireland [ 24 ]. Therefore, a rate of 20% of miscarriage was selected as the cut-off rate in this study.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was carried out using mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Age was categorised using tertiles (i.e. 33.3% of the students were 21 years old or younger and 66.7% were 23 years old or younger). Three categories were created to calculate the number of students who underestimated (i.e. below the correct answer), correctly estimated or overestimated (i.e. above the correct answer) the rate of miscarriage. Information regarding the university students’ knowledge about contributory risk factors of miscarriage was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. In the context of this study, answers were categorised as agree, unsure and disagree.

Chi-square tests were performed to assess the relationship between general demographic and educational characteristics, and knowing someone who had a miscarriage and identifying the correct rate of miscarriage. Chi-square tests were also calculated to investigate the relationship between independent variables and awareness of the most common causes of miscarriage. Binary logistic regression was calculated to estimate the probability of selecting risk factors for miscarriage (i.e. agree versus disagree) and general demographic and educational characteristics, knowing or not someone who had a miscarriage (i.e. themselves, partners, family, friends or celebrities) and whether the rate of miscarriage was correct, underestimated or overestimated. A high number of university students were unsure of their answers, and therefore, we also explored the relationship between agree versus unsure in the identification of risk factors for miscarriage; however, only those results which showed statistically significant differences and which added extra information to the comparison were reported.

A total number of 25 possible causes of miscarriage were alphabetically ordered in the questionnaire. For the purpose of this study we only analysed the Odds Ratios for those risk factors with a strong association with miscarriage (i.e. age, chromosomal abnormalities, smoking, alcohol and medical condition of mother) and for some spurious risk factors for miscarriage (i.e. flu vaccine, flying, hair dye, verbal arguments and vitamin C). Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR and aOR respectively) were calculated for all independent variables with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). All the analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 (IBM).

Overall, 872 students responded to the online survey. Of those, 126 were excluded from the analysis because they did not complete more than half of the survey or they had highly extreme answers in demographic characteristic such as age. Therefore, a total sample of 746 university students were included in our analysis. The mean age was 24.3 years (SD = 6.58), and most of students were between 21 and 22 years old ( n = 284; 38.1%) or were 23 years old or older ( n = 289; n = 38.7%) ranging between 18 and 60 years old. More than half of the respondents were females ( n = 577; 77.3%), and approximately 80% were single ( n = 617). The discipline with the lower response rate was Business and Commerce and Law ( n = 104; 13.9%) and with the highest response rate was Medicine and Health ( n = 280; 31.9%).

Male students were more likely to report that they did not know anyone who had a miscarriage compared to female students (23.9% versus 9.6%; p < 0.001). Students aged 23 years old or older were more likely to report they knew someone who had a miscarriage; however, students of 20 years of age or younger were more likely to report they were aware of a celebrity who had had a miscarriage ( p < 0.05). Single students were also more likely not to know anyone who had a miscarriage compared to those who had a partner, were married, were cohabiting or divorced (14.1% versus 5.8%; p < 0.05). Females were more likely to be aware of a celebrity who had a miscarriage than male students (16.9% versus 7.0%, Table 1 ). Students from Engineering and Food Science ( n = 34; 18.3%) or Business and Commerce and Law ( n = 14; 14.9%) disciplines were more likely to report that they did not know anyone with a miscarriage. Medicine and Health ( n = 159; 74%), and Arts and Social Science ( n = 130; 72.6%) were more likely to know someone who had a miscarriage (Table 1 ).

Only 20% ( n = 149) of students identified a mean rate of 20% for miscarriage. The remaining students underestimated or overestimated the rate of miscarriage (Table 2 ). Female students, older students and those who knew someone who had a miscarriage were more likely to identify the 20% rate of miscarriage. Students from Arts and Social Science ( n = 45, 22.5%) and Medicine and Health ( n = 52, 21.9) were more likely to estimate the correct rate of miscarriage (Table 2 ). A total of 96 (12.9%) students correctly responded that miscarriage happens up to 12 weeks of gestation (early miscarriage) or up to 24 weeks of gestation (late miscarriage). Overall, only 54 (6.2%) students were aware that miscarriage can happen from conception until 24 weeks of gestation. A quarter of all students ( n = 179; 24%) thought miscarriage could happen at any stage of pregnancy.

The most common cause of miscarriage identified by the university students was chromosomal abnormalities in the baby, ( n = 316; 42.4%), followed by medical conditions ( n = 177; 23.7%) and lifestyles ( n = 109; 14.6%). Chromosomal abnormalities of the baby were identified as the most common cause of miscarriage in a higher percentage of female students, older students (i.e. 23 years old or older), students who reported being married, divorced or cohabiting, students from Medicine and Health and for those students who knew a celebrity who had a miscarriage. Male students, younger and single students, students from Engineering and Food Science and Business and Commerce and Law, and students who reported that they did not know anyone who had a miscarriage were more likely to report lifestyles and the medical condition of the mother as the most common cause of miscarriage (Table 3 ).

Students who correctly estimated the rate of miscarriage were more likely to select chromosomal abnormalities as the main cause of miscarriage ( n = 72; 48.3% for correct rate of miscarriage, n = 136; 45.9% for overestimated rate and n = 107; 36.3% for underestimated rate; Table 3 ). Conversely, students who correctly identified the rate of miscarriage were less likely to select psychological problems as the main cause of miscarriage. Students who overestimated the rate of miscarriage were less likely to identify medical conditions of the mother as a cause of miscarriage, whereas those who underestimated were more likely to select it. Approximately 15% (underestimated rate n = 42; correct rate n = 22 and overestimated rate n = 44) of students selected lifestyle behaviour as the main cause of miscarriage independently of the selected rate of miscarriage (Table 3 ).

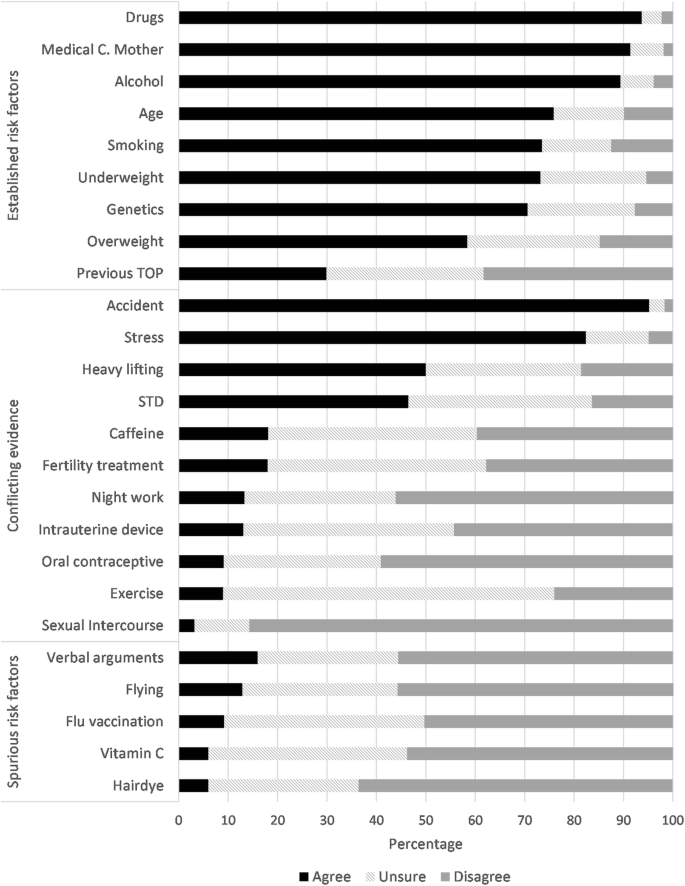

The most reported risk factors for miscarriage were accident or fall, drugs, medical condition of the mother, alcohol, stress, age smoking and being underweight. Most students disagreed that sexual intercourse, hair dye, vitamin C and exercise were risk factors for miscarriage (Fig. 1 ).

Percentage of most selected risk factors for miscarriage

Overall, the majority of college students correctly selected age ( n = 566; 88%) and medical conditions of the mother ( n = 682; 98%) as contributory risk factors for miscarriage. No statistically significant differences between agree or disagree responses for age or for medical conditions of mother were found between groups (Additional file 1 : Table S1). However, students from Arts and Social Science were more likely to be unsure about age as a risk factor (aOR 2.78; 95% CI 1.52–5.09). Students of 21 years of age or older were more likely to identify chromosomal abnormalities as a causative factor for miscarriage than those aged 20 years old or younger (students aged 21–22: aOR 0.27; 95% CI 0.12–0.61 and students aged 23 years old or older: aOR 0.48; 95% CI 0.24–0.96; Additional file 1 : Table S1). Students from Arts and Social Science or Business and Commerce and Law more frequently did not identify chromosomal abnormalities as a potential causative factor compared to college students from Medical and Health (aOR 2.40; 95% CI 1.01–5.73 and aOR 3.0; 95% CI 1.16–7.73 respectively; Additional file 1 : Table S1).

Male students were more likely to agree that smoking was a risk factor for miscarriage compared to female students (aOR 0.47; 95% CI 0.24–0.94). Older students (i.e. 23 years old or older) disagreed more frequently that smoking was a risk factor for miscarriage compared to students who were 20 years old or younger (aOR 2.09; 95% CI 1.08–4.07). Compared to students from Medicine and Health, the remaining disciplines disagreed more frequently that smoking was a risk factor. For alcohol, older students and those from Business and Commerce and Law were more likely to disagree that it was a risk factor for miscarriage (Additional file 1 : Table S1).

Students from Arts and Social Science were more likely to identify flu vaccination as a risk factor for miscarriage ( n = 25; 26.9%; Additional file 1 : Table S2). Students from Engineering and Food Science and Business and Commerce and Law were more likely to identify verbal arguments as a risk factor for miscarriage (aOR 0.56; 95% CI 0.31–0.99 and aOR 0.42; 95% CI 0.21–0.82). Students between 21 and 22 years old were more likely to be unsure that vitamin C was a risk factor for miscarriage compared to younger students (aOR 2.85; 95% CI 1.21–6.72; Additional file 1 : Table S2). Only students who were 23 years old or older were more likely to identify vitamin C as a spurious risk factor compared to students who were 20 years old or younger (aOR 2.34; 95% CI 1.03–5.34; Additional file 1 : Table S2).

Among the remaining potential causative risk factors for miscarriage, male students were less likely to identify working night shifts and previous termination of pregnancy (TOP) as risk factors (aOR 0.45; 95% CI 0.25–0.80and aOR 0.44; 95% CI 0.26–0.72). Older students (i.e. 23 years old or older) were less likely to identify caffeine as a risk factor (aOR 2.61; 95%CI 1.45–4.70). Compared to students from the college of Medicine and Health, those from Business and Commerce and Law were less likely to identify sexually transmitted disease, previous TOP and being underweight as contributory risk factors for miscarriage (aOR 3.39; 95% CI 1.77–6.51 and aOR 2.20; 95% CI 1.13–4.25 and aOR 2.79; 95% CI 1.10–7.03). Students from Engineering and Food Science were less likely to identify night work as a risk factor, but were more likely to consider stress as a contributory risk factor for miscarriage compared to Medicine and Health students (aOR 2.06; 95%CI 1.08–3.93 and aOR 0.36; 95% CI 0.13–0.98). The odds of not identifying oral contraceptive as a cause of miscarriage were lower for students who overestimated the rate of miscarriage compared to those who correctly identified the rate (OR: 0.30; 95% CI 0.12–0.75). Finally, only students from Arts and Social Science were more likely to identify heavy lifting as a risk factor.

Main findings

This cross-sectional study provides insight into university students’ awareness of prevalence and risk factors of miscarriage. The findings of this study illustrate that common misunderstandings still prevail regarding the aetiology of miscarriage, suggesting a deficiency in formal information and access to information related to reproductive health. For example, only 20% of the students correctly identified the prevalence of miscarriage at 20%, and almost 30% incorrectly believed the prevalence of miscarriage is less common than 10%. Female students were more likely to identify the correct rate, but also to overestimate it, and male students tended to underestimate it. Almost one-quarter of the students believed miscarriage can happen from conception until birth, and 87% of the students erroneously selected the weeks of gestation at which miscarriage occurs. Females students, older students, those from Medicine and Health, those who were aware of a celebrity who had a miscarriage, and those who identified the correct rate of miscarriage were more likely to identify chromosomal abnormalities as the most common cause of miscarriage. However, this was only identified by 43% of the total sample.

Strengths and limitations

The nature of the study design implies that data were collected at one point in time. Previous studies have found an association between ethnicity and religion and the perception of risk factors for miscarriage [ 25 ], however we did not include this information in our survey and no comparison can be made. One of the main limitations is that a higher percentage of female students responded to the survey compared to male students. Although similar gender distributions were reported at UCC in the academic year 2006/2007 (36% male and 64% females) [ 26 ], recent overall data shows a more equal gender distribution for third-level graduates in the Republic of Ireland in 2016, with 52.2% of the students being female [ 27 ]. This percentage is similar to the European Union (EU-28) in 2015 [ 28 ]. Nevertheless, our sample seems to be representative of the overall distribution of male and females by discipline. In 2016, women represented more than three out of four (76.4%) graduates in Health, and more than four out of five (82.4%) graduates in Engineering were male [ 27 ] in the Republic of Ireland.

No standardised instrument of relevance was found in the literature for the purpose of this study; and therefore our survey was not validated. A multidisciplinary team specialised in pregnancy loss developed and reviewed all questions. In addition, a patient advocate for women who experience pregnancy loss also reviewed the questionnaire to ensure clarity. To our knowledge, this is one of the largest studies exploring the knowledge of rates and risk factors for miscarriage among college students from multiple disciplines, representing the main strength of this study.

Comparison with other studies

Our study is in keeping with the results of two previous studies [ 25 , 29 ]. In a cross-sectional study including 1084 adults located in 49 states within the United States, Bardos et al. found that half of the participants believed that miscarriage was uncommon, occurring in 5% or less of all pregnancies. Similar to our results, it also found that approximately one fifth of the respondents incorrectly believed that lifestyle behaviours such as consumption of drugs, alcohol or tobacco were the only cause of miscarriage. In addition, men were more likely to identify lifestyle behaviours as a contributing risk factor for miscarriage. Also, participants with a higher educational degree identified chromosomal abnormalities more frequently as a cause of miscarriage compare to less educated respondents [ 25 ]. It is important to note that approximately 80% of these participants attended some college or medical school. Interestingly, in our study, male students were also more likely to identify smoking as a contributing risk factor. In another study, Delgado et at assessed awareness among undergraduate students related to preconception health and pregnancy. Results showed a low to moderate level of awareness, with women having a slightly higher awareness than men [ 29 ].

Assessing the reasons behind overestimating or underestimating the risk of miscarriage is difficult to understand [ 30 ]. It could be possible that students who overestimate the risk of miscarriage were under unnecessary stress or anxiety at the time of this study. Some studies have shown a link between psychological distress and anticipatory representations of possible future threats or overestimating the risk of a disease [ 31 , 32 ]. No studies have evaluated college students’ psychological and lifestyles factors and perception of risk of pregnancy loss; therefore, more research needs to be done to assess which are the underlying factors that might impact on population’s perception of risk of pregnancy loss.

Implications

Despite the high occurrence of miscarriage, some studies highlight the potential barriers that might influence the lack of awareness of this topic among the general public. For example, the existence of guilt, shame or feeling responsible for the pregnancy loss might have reinforced the reclusion of the topic exclusively to the close family or friends, or in some cases, only among the couple who experience miscarriage [ 33 , 34 ]. This has led to miscarriage being a “taboo” or “unspoken” topic in some cultures, increasing the chance of the causes of miscarriage being surrounded by myths and folklore [ 25 , 35 ]. The potential benefits of promoting healthy behaviours, lifestyle, mental and social factors during women and men’s reproductive years has been increasingly accepted in the medical and scientific community [ 13 , 36 ].In this context, preconception health care is a unique opportunity to increase personal responsibility and awareness of risk factors and adverse pregnancy outcomes during the reproductive years of this targeted population [ 16 ].

Universities are underused settings for improving preconception health among the community. They provide an opportunity to reach a population with a diverse socioeconomic and gender background. In a scoping review of 29 preconception health care interventions evaluations, six of them were delivered at a School, college or university settings [ 17 ]. All of them reported an improvement in preconception health knowledge [ 29 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]; however, most of the interventions were provided to women who were identified as being at-risk of developing adverse maternal outcomes, and men were not generally included in the interventions [ 37 ]. Although the Republic of Ireland has one of the highest birth rates in Europe [ 41 ], to our knowledge, there are no preconception healthcare intervention programmes or clinical practice guidelines focused on improved preconception healthcare in higher education settings.

According to our results and the little evidence available, misunderstanding of causes and risk factors for miscarriage is a public health issue. The findings of this study highlight an opportunity for public health interventions to improve reproductive health education. Universally preconception healthcare programmes successfully provide health promotion strategies to increase awareness of potential adverse outcomes in pregnancy. In particular, University settings are an ideal opportunity to reach a targeted population.

Abbreviations

Adjusted odds ratios

Confidence intervals

European Union of 28 member states

Unadjusted odds ratios

Standard deviation

Termination of pregnancy

University College Cork

Jurkovic D, Overton C, Bender-Atik R. Diagnosis and management of first trimester miscarriage. BMJ. 2013;346:f3676.

Article Google Scholar

Zinaman MJ, Clegg ED, Brown CC, O’Connor J, Selevan SG. Estimates of human fertility and pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril. 1996;65(3):503–9.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Larsen EC, Christiansen OB, Kolte AM, Macklon N. New insights into mechanisms behind miscarriage. BMC Med. 2013;11.

Regan L, Rai R. Epidemiology and the medical causes of miscarriage. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;14(5):839–54.

Prior M, Bagness C, Brewin J, Coomarasamy A, Easthope L, Hepworth-Jones B, Hinshaw K, O’Toole E, Orford J, Regan L, et al. Priorities for research in miscarriage: a priority setting partnership between people affected by miscarriage and professionals following the James Lind Alliance methodology. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e016571.

De La Rochebrochard E, Thonneau P. Paternal age and maternal age are risk factors for miscarriage; results of a multicentre European study. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(6):1649–56.

Weintraub AY, Sergienko R, Harlev A, Holcberg G, Mazor M, Wiznitzer A, Sheiner E. An initial miscarriage is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes in the following pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(3):286.e1-5.

Hyland A, Piazza KM, Hovey KM, Ockene JK, Andrews CA, Rivard C, Wactawski-Wende J. Associations of lifetime active and passive smoking with spontaneous abortion, stillbirth and tubal ectopic pregnancy: a cross-sectional analysis of historical data from the Women’s health initiative. Tob Control. 2015;24(4):328–35.

Armstrong DS. Impact of prior perinatal loss on subsequent pregnancies. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004;33(6):765–73.

Venners SA, Wang X, Chen C, Wang L, Chen D, Guang W, Huang A, Ryan L, O’Connor J, Lasley B, et al. Paternal smoking and pregnancy loss: a prospective study using a biomarker of pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(10):993–1001.

Seshadri S, Oakeshott P, Nelson-Piercy C, Chappell LC. Prepregnancy care. BMJ. 2012;344:e3467.

Jack BW, Culpepper L. Preconception care. Risk reduction and health promotion in preparation for pregnancy. JAMA. 1990;264(9):1147–9.

Preconception Health and Health Care [ https://www.cdc.gov/preconception/index.html ]. Accessed 23 May 2018.

Atrash HK, Johnson K, Adams M, Cordero JF, Howse J. Preconception care for improving perinatal outcomes: the time to act. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(5 Suppl):S3–11.

Johnson K, Posner SF, Biermann J, Cordero J, Atrash HK, Parker CS, Boulet SL, Curtis MG. Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care - United States. A report of the CDC/ATSDR preconception care work group and the select panel on preconception care. JSTOR. 2006;55:1–23.

Google Scholar

Shawe J, Delbaere I, Ekstrand M, Hegaard HK, Larsson M, Mastroiacovo P, Stern J, Steegers E, Stephenson J, Tyden T. Preconception care policy, guidelines, recommendations and services across six European countries: Belgium (Flanders), Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2015;20(2):77–87.

Hemsing N, Greaves L, Poole N. Preconception health care interventions: a scoping review. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2017;14:24–32.

Boulet SL, Parker C, Atrash H. Preconception care in international settings. Matern Child Hlth J. 2006;10(5 Suppl):S29–35.

Higher Education Authority: Key Facts and Figures ( 2016/2017 ) . In Dublin: Higher Education Authority; 2018.

University College Cork. University College Cork. National University of Ireland, Cork. Principal statute. In: Universities Act 1997. Ireland: University College Cork; 2009.

Wright PM. Barriers to a comprehensive understanding of pregnancy loss. J Loss Trauma. 2011;16(1):1–12.

Royal College of Physicians of Ireland: Ultrasound Diagnosis of Early Pregnancy Miscarriage. In: National Clinical Guidelines in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Republic of Ireland: Royal College of Physicians of Ireland, RCPI; 2010.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: The investigation and treatment of couples with recurrent first-trimester and second-trimester miscarriage. In.: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2011.

Royal College of Physicians of Ireland. The management of second trimester miscarriage. In: National Clinical Guidelines in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Republic of Ireland: Royal College of Pysicians of Ireland, RCPI; 2017.

Bardos J, Hercz D, Friedenthal J, Missmer SA, Williams Z. A national survey on public perceptions of miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1313–20.

Irish Universities Association. Irish Universities Study. Gender at a glance: Evidence from the Irish Universities Study. Ireland: Irish Universities Association; 2009.

Central Statistics Office. Women and Men in Ireland 2016 [ https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-wamii/womenandmeninireland2016/education/#d.en.140093 ] Accessed 3 Aug. 2018.

European Commission. Eurostat. Tertiary education statistics [ http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Tertiary_education_statistics#Gender_distribution_of_participation ] Accessed 3 Aug. 2018.

Delgado CE. Undergraduate student awareness of issues related to preconception health and pregnancy. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(6):774–82.

Sjoberg L. Factors in risk perception. Risk Anal. 2000;20(1):1–11.

Audrain J, Schwartz MD, Lerman C, Hughes C, Peshkin BN, Biesecker B. Psychological distress in women seeking genetic counseling for breast-ovarian cancer risk: the contributions of personality and appraisal. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19(4):370–7.

Grupe DW, Nitschke JB. Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: an integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(7):488–501.

Broen AN, Moum T, Bodtker AS, Ekeberg O. The course of mental health after miscarriage and induced abortion: a longitudinal, five-year follow-up study. BMC Med. 2005;3:18.

Barr P. Guilt- and shame-proneness and the grief of perinatal bereavement. Psychol Psychother. 2004;77(Pt 4):493–510.

Schaffir J. Do patients associate adverse pregnancy outcomes with folkloric beliefs? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(6):301–4.

Hussein N, Kai J, Qureshi N. The effects of preconception interventions on improving reproductive health and pregnancy outcomes in primary care: a systematic review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2016;22(1):42–52.

Dejoy SB. Pilot test of a preconception and midwifery care promotion program for college women. J Midwifery Women Health. 2014;59(5):523–7.

Gardiner P, Hempstead MB, Ring L, Bickmore T, Yinusa-Nyahkoon L, Tran H, Paasche-Orlow M, Damus K, Jack B. Reaching Women Through Health Information Technology: The Gabby Preconception Care System. Am J Health Promot. 2013;27(3):Es11–20.

Richards J, Mousseau A. Community-based participatory research to improve preconception health among Northern Plains American Indian adolescent women. Am Indian Alaska Nat. 2012;19(1):154–85.

Schiavo R, Conzalez-Flores M, Ramesh R, Estrada-Portales I. taking the pulse of progress toward preconception health: preliminary assessment of a national OMH program for infant mortality prevention. J Commun Healthc. 2013;4(2):106–17.

Department of Health. Creating a better future together: National Maternity Strategy 2016-2026. Ireland: Department of Health Dublin. p. 2016.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study received ethical approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospital on ECM 6 (rrrr) 120,416. Consent to participate was implied through completed surveys.

This study was supported by departmental funding. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Pregnancy Loss Research Group, The Irish Centre for Fetal and Neonatal Translational Research, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland

Indra San Lazaro Campillo, Sarah Meaney, Jacqueline Sheehan, Rachel Rice & Keelin O’Donoghue

National Perinatal Epidemiology Centre, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University College Cork, 5th floor, Cork University Maternity Hospital, Wilton, Cork, T12 YE02, Ireland

Indra San Lazaro Campillo & Sarah Meaney

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JS, RR, SM and KOD conception and designed of the survey. JS obtained the data and ISLC analysed them. ISLC and SM interpreted the data. The questionnaire was anonymous and data were only accessed by the authors involved in the study. We confirm that all authors included in this study participated in the drafting and have approved the manuscript for submission. This manuscript has not been published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Indra San Lazaro Campillo .

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

Table S1. Odds Ratios of agreement with strong risk factors for miscarriage. Table S2. Odds Ratios of disagreement with spurious risk factors for miscarriage. (DOCX 33 kb)

Rights and permissions