Enter the URL below into your favorite RSS reader.

Analyzing the Landscape: Community Organizing and Health Equity

- Citation (BibTeX)

View more stats

In this paper we describe landscape analysis, a participatory research method for public health scholars interested in identifying and elucidating trends, opportunities, and gaps in the field. We used this method to understand the environmental and social conditions of primarily under-resourced communities of color, and identify key organizing strategies and practices used by community organizers to fight for policy and systems change around childhood health equity issues. Using a community-based participatory research approach, we developed and implemented a structured landscape analysis process among a national sample of 45 community-based organizations (CBOs). We discuss in detail our sampling procedures, protocol development, and analysis process. The resulting landscape analysis revealed similar challenges (e.g., lack of adequate housing, poor early childhood education resources) across diverse communities, and the best practices and innovative solutions used by CBOs to address these challenges. The landscape analysis process underscores the important role that social justice grassroots CBOs play in addressing the root causes of health inequity even though they may not identify, or be identified, as “public health” organizations.

Analyzing the Landscape: Community Organizers and Health Equity

Persistent disparities in health stem from social and structural conditions that disadvantage low-income communities of color and put the most vulnerable at increased risk for poor health outcomes (Larson et al. , 2008) . Health outcomes that disproportionately impact children of color, include overweight and obesity (Flores , 2010; Guerrero et al. , 2016; Ogden et al. , 2012) , asthma (Flores , 2010) , and birth outcomes (Blumenshine et al. , 2010) . Health disparities among children are particularly concerning as recent data suggest that for some indicators these disparities are widening (Mehta et al. , 2013) . Poor health in childhood contributes to increased healthcare costs across the lifespan, higher morbidity and mortality, and decreased quality of life (Braveman & Barclay , 2009) . Strategies and interventions seeking to reduce childhood health disparities must address the underlying social determinants including poverty, racism, and segregation (Braveman et al. , 2011; Braveman & Barclay , 2009; Minkler et al. , 2019; Sanders-Phillips et al. , 2009) .

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) – a community-centered approach that strives to equitably involve community members and researchers as partners in the research process – has been used to garner community support for numerous collaborative projects focused on childhood health disparities (Israel et al. , 2003 , 2005) . A CBPR approach leverages the combined expertise of all team members including the lived experience and insider knowledge that community members bring to the partnership. Israel and colleagues (2005) advocate for greater use of CBPR principles and strategies, especially when working with marginalized communities that have been historically excluded from the research process.

Community organizing philosophy dovetails with public health frameworks that prioritize root causes, social justice, and systems change (Minkler et al. , 2019; Pastor et al. , 2018) and a CBPR approach that centers community wisdom (Israel et al. , 1998 , 2003) . A goal of community organizing is to support community empowerment, collective action, and advocacy to change the structures and systems that perpetuate inequity (Christens & Speer , 2015) . Community organizers accomplish this by directly engaging local residents most impacted by social injustice, with the aim of building and sustaining community power in order to advocate for systems change (Fisher et al. , 2018; Grills et al. , 2014; Minkler et al. , 2019; Pastor et al. , 2018; Wallerstein & Duran , 2010) . Organizers understand that social change and the fight for health equity requires a transformational, movement-building approach that transcends individual issues or campaigns (Pastor et al. , 2011) .

Community organizing in the context of public health has been defined as “grassroots movements that empower and mobilize individuals to act in their own collective self-interest to address community health problems by altering the balance of power, resource distribution, and policy decision making in their environments” (Subica et al. , 2016 , p. 80) and is gaining traction as a public health strategy to address the social determinants of health (Grills et al. , 2014; Minkler et al. , 2019; Pastor et al. , 2018) . For example, community organizing has been used to connect individuals to collective efforts that target community conditions harmful to health, including food and recreation environments (Grills et al. , 2014; Subica et al. , 2016) , public safety (Speer et al. , 2003) , education (Gutiérrez & Lewis , 2012) , and environmental health (Cohen et al. , 2016) .

Grassroots social justice organizations, community organizers, and community members are key players in the fight for health equity. Organizers have direct knowledge of and experience with a range of social and structural issues that impact health and a deep understanding of community strengths and needs (Minkler et al. , 2019) . However, community organizing is decentralized and context-specific, making it difficult, at times, to track promising practices or innovative solutions in the field and share knowledge or resources across communities or content areas. To address these challenges, we sought a community-engaged, participatory research method to learn from community organizers about their work on the ground that would also support a big picture analysis to identify shared struggles and best practices in the field. We adapted a process commonly used in community organizing, referred to as landscape analysis, to understand the landscape of issues related to childhood health disparities that could inform community-driven strategies to address health inequities. Our landscape analysis process documents the social justice work and community organizing strategies used to support childhood health in resource-poor communities across the country. Specifically, the landscape analysis revealed important insights about the social and environmental conditions affecting childhood health and the strategies and practices that were most effective for supporting health equity. In this paper, we describe the CBPR framework and methods used in the landscape analysis process including our sampling strategy, development of tools, data collection, data analysis, and data dissemination. We discuss the benefits, limitations, and implications of this approach.

Overview of the Landscape Analysis Process

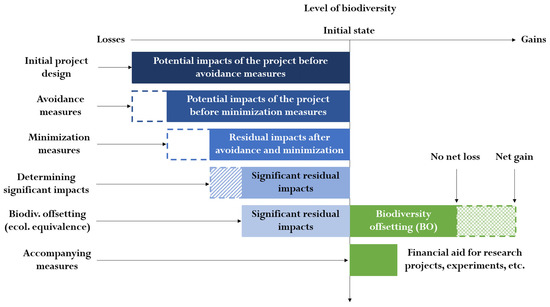

Field scanning (also called landscape scanning) is a practice used in philanthropy to identify the assets, needs, and gaps in a particular field (GrantCraft , 2012; Learning for Action , 2017; Sherry , 2013) . Scanning takes a broad view to better understand opportunities, emerging issues, and field trends. For example, a field scan can help a funder to determine the best investment opportunities, thereby increasing efficiency, illuminate existing tools and strategies to avoid “reinventing the wheel,” and identify opportunities for collaboration and relationship building (Sherry , 2013) . This general approach has been applied to childhood mental health and education systems (Grife & Werner, 2018; (Learning for Action , 2017) . A similar method from the business world called environmental scans draws on both internal (e.g., organizational documents) and external information (e.g., social and political context) to inform strategic planning and assist with decision making (Graham et al. , 2008) . Environmental scans have been used by public health researchers and practitioners to design health programs and interventions (e.g., vaccination programs, cancer screenings) (Graham et al. , 2008; Rowel et al. , 2005; Wilburn et al. , 2016) .

The process itself varies depending on the purpose and goal of the scan, but methods include interviews with key constituents, surveys, literature and documents reviews, focus groups, visual mapping, or some combination of these methods (Sherry , 2013) . Importantly, the information gleaned from the scan is actionable. While field scans and environmental scans are valuable tools for big picture assessment and planning, neither explicitly employs participatory methods, which is central to our work with marginalized communities and community organizers. Therefore, we adapted these approaches for use within a CBPR framework that utilizes participatory methods and a consistent social justice lens to analyze the landscape of health equity community organizing. We define landscape analysis as a participatory data collection and assessment process useful for understanding the broader context, evaluating strengths and challenges, and identifying field trends to inform actionable next steps. We use the term landscape analysis, rather than field scanning, to reflect the preferred terminology among the community organizing practitioners that we work with.

Our goal for the landscape analysis process was twofold. First, we wanted to produce a bird’s eye analysis of community organizing efforts, based on what we learned from community organizers, about the most pressing issues facing their communities as well as the strategies and practices they employ to advance health equity. By capturing these stories from different communities across the country, our intent was to uplift localized efforts, identify promising or innovative solutions, and track trends and patterns on a national scale. The landscape analysis can serve as a resource for organizers, practitioners, and researchers working in the areas of grassroots social justice movements, health equity, and childhood health. Second, we wanted to engage in praxis by putting the research findings into action. Community organizers use landscape analysis to deepen their understanding of the scope, scale, and structural causes of the social and economic conditions they seek to address. An analysis of the landscape also informs an analysis of power – who benefits from the problem, who loses, how the organized power works toward the agenda, and how the organized power works against the agenda (Castellanos & Pateriya , 2003) . The landscape analysis is the first step in developing systems change campaigns and organizing strategies. Therefore, landscape analysis can be leveraged to 1) facilitate networking and alliance building and strengthen the movement by connecting organizations (i.e., by geographic region or by social justice issue area) that might otherwise not know about each other; 2) support shared-learning, collaboration, and maximize the use of existing resources to support collaborative efforts, which can be significant for community-based organizations (CBOs) that are typically operating with limited resources; and 3) track trends and identify best practices for effective organizing and advocacy strategies across the field. In the following sections, we describe the application of the landscape analysis process to a community organizing health equity project, including details of the procedures and methods used, and discuss strengths and limitations of this approach.

Communities Creating Healthy Environments

Since its inception in 2009, the Communities Creating Healthy Environments (CCHE) initiative, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), recognized grassroots social justice organizing as a strategy to address childhood health injustice in marginalized communities using a CBPR framework (Grills et al. , 2014) . CCHE supports the work of grassroots social justice CBOs to advance environmental change using the art and science of community organizing. Over the past decade, the Praxis Project (Praxis) has served as the national program office and the Psychology Applied Research Center at Loyola Marymount University (PARC@LMU) as the national evaluator for CCHE. During Phases 1 (2009-2013) and 2 (2014-2016) of CCHE, Praxis worked directly with CBOs to build organizational capacity, support policy advocacy campaigns (resulting in 72 policy wins that increased access to nutritious and affordable food and safe places to play), and develop a national network of over 200 grassroots social justice CBOs (Grills et al. , 2014) . Phase 3 sought to leverage these networks and relationships to gain insights about best practices and emerging strategies used by organizers to advance health equity efforts.

CCHE network members are working on any number of social justice issues including fair housing, environmental justice, and police accountability, all of which ultimately advance health equity. CBOs often operate with limited resources (i.e., small budgets, reliance on part-time staff or volunteers, etc.) and because campaigns and advocacy work often focus on the local context, community organizing work can be isolating. The landscape analysis presented an opportunity to learn from a wide range of organizers, produce knowledge, and share resources that could be distributed across the CCHE network.

Under the leadership of Praxis, we developed a five-step process to analyze the landscape of childhood health inequities. Consistent with our CBPR approach, project partners (described below) were involved at every stage of the process.

Step 1: Identify Shared Meaning

In coordination with our project partners, Praxis and the CCHE Collaborative (technical assistance providers and other leaders representing national and local community organizing groups affiliated with CCHE since Phase 1), we identified three primary functions of the landscape analysis process: 1) understand the environment and health of African American, American Indian, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Latino children in under-resourced and underserved communities; 2) uplift the current work of grassroots CBOs, including programs, services, organizing activities, and social justice campaigns; and 3) identify key organizing strategies (or “community-defined best practices”) used by grassroots CBOs to improve childhood health, including strategies that are not necessarily labeled as public health strategies. These initial conversations took place primarily via phone and teleconference among key project partners (i.e., PARC@LMU, Praxis, and CCHE Collaborative members).

Step 2: Develop Sampling Strategy and Instruments

Once the project partners agreed to the scope and purpose of the landscape analysis, we were ready to begin developing the methodology and analytic plan. A combined strategy was used to ensure that both rigorous qualitative methods and a community organizing focus guided the instrument development, codebook creation, and data analysis.

Sampling Strategy

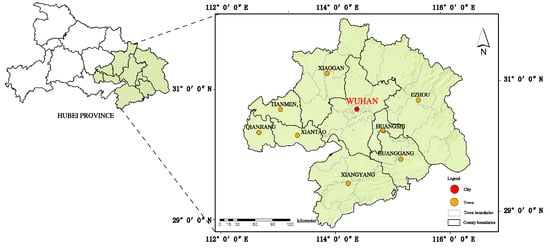

To ensure a representative sample of diverse CBOs (in terms of geographic location and ethnic/racial communities served) the key informant groups were stratified by region (Midwest, Northeast, South, Southwest, and West) and ethnic/racial constituency group (African American, Asian and Pacific Islander, Latino, Indian Country, and Mixed Constituency). Our project partners assisted with developing a list of potential key informants on a shared Google spreadsheet, which allowed individuals to add suggestions, pose questions to each other, and edit the list in real time. The initial sampling pool was drawn from existing network members (from CCHE Phases 1 and 2) and CCHE Collaborative contacts (these included organizations that were not part of the CCHE network previously, but that were engaged in community organizing work that impacted children).

We revised recruitment strategies with input from our project partners and reduced the list of potential key informants from 34 to 20 groups using the following criteria: 1) CBOs representing desired geographic regions and ethnic/racial constituencies; 2) CBOs who knew their communities well and were also focused on improving the lives of children using community-defined practices; and 3) those with whom Praxis and/or CCHE Collaborative members had an existing relationship. Organizations selected for the landscape analysis were engaged in community organizing that may or may not have an explicit focus on childhood health. For example, many CBOs in our sample do not define themselves as health organizations (i.e., focus areas include immigrant rights, economic justice, etc.), but nevertheless, their organizing work impacts community, and particularly children’s, health. Social determinants of health (e.g., racism, poverty, etc.) are central to any public health strategy, especially one aiming to reduce inequity, and can best be discerned through the type of community engagement at which organizers excel.

Through an iterative process, we dropped and added CBOs from the list depending on the interest and availability of key informants. We exceeded our target of 20 interviews by December 2016, with a total sample of 23 organizations. Snowball sampling was used to generate a second sampling pool with 64 new organizations identified by key informants from the first round of interviews. Again, with input from CCHE Collaborative members, we reduced the list of potential key informants from 64 to 26 groups using the same criteria from the first round of interviews. As a result, 49 groups were dropped from the initial list and 11 groups were added for a target goal of 26 interviews. Four groups were not available to complete the interview before the end date in September 2017, resulting in a total sample of 22 interviews. The final sample across two rounds of interviews included 45 key informants representing grassroots CBOs across the country. See Table 1 for ethnic/racial constituency and geographic representation breakdown for both rounds of interviews.

| African American | API | Latino | Indian Country | Mixed | Total | |

| Midwest | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 9 |

| Northeast | 2 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 11 |

| South | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Southwest | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| West | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 14 |

Create Instruments

We designed the key informant phone interview protocol in May 2016 with input from project partners. The interview protocol included a statement about confidentiality and the purpose of the landscape analysis, a brief quantitative assessment of organizational capacity needs and strengths (five minutes), and a semi-structured interview (45 to 60 minutes). We found that interviewees were more likely to respond to the organizational capacity survey while we had them on the phone for the interview, rather than try to get them to complete it on their own before or after the phone call. The interviewer read the brief survey questions aloud and recorded their answers in Qualtrics (online survey tool) on behalf of the respondent, and then transitioned to the semi-structured interview questions. The call was recorded on Zoom and the interviewer was trained to take written notes of high-level themes and key words or phrases. In total, the phone call took about one hour and covered the following topics: 1) Social Conditions, Barriers, and Impacts: features of the social and physical environment that inhibit healthy living and impact childhood health; 2) Current Work of the Organization: successful campaigns, efforts and programs to improve health, wellness, or safety in the community; and 3) Best Practices: strategies used by the organization to make a change that matters.

Consistent with our CBPR process, we piloted the interview protocol in June 2016 with four social justice organizations (two Los Angeles-based CBOs and two national non-profits from Indian Country). The protocol underwent substantive changes incorporating observations from the pilot interviews and feedback from our project partners. A slightly modified protocol was developed in consultation with Native Organizers Alliance, a longtime CCHE partner and technical assistance provider, for use with Indian Country constituency members. We finalized the interview protocol, including administration guidelines and questions, in July 2016 and began interviews in August 2016.

Step 3: Data Collection

The landscape analysis data included interviews with key informants and a targeted review of various information sources about each organization and their respective communities (i.e., ethnic/racial and geographic region). PARC@LMU, Praxis, and the CCHE Collaborative comprised the interview team, who jointly conducted 45 key informant interviews over 13 months. Given PARC@LMU’s expertise in mixed methods data collection, we trained the team of eight interviewers on how to administer the organizational capacity survey via Qualtrics and conduct the semi-structured interviews. PARC@LMU was also responsible for scheduling and recording the phone interviews. Both PARC@LMU and Praxis transcribed the interviews for analysis. Interviews were conducted in two stages, as described above in the sample procedures section.

Concurrently, PARC@LMU researchers reviewed documents about the CCHE communities to shed light on the health environment and social contexts that impact children’s health. Specifically, our team pulled information from government sources (e.g., school and education outcomes, health dashboards, crime data, etc.), grey literature including policy papers and reports published by CBOs or foundations, CBO websites and social media, and other media (e.g., news coverage about CBO campaigns). These data-gathering activities helped to provide localized context and relevant information to interpret the key informant interviews through the appropriate lens and to develop written snapshot profiles of each organization (described in greater detail below).

Step 4: Data Analysis

We used an inductive approach to identify specific concepts in the interview transcripts that explain and give meaning to community-defined best practices within a specific cultural and community context as it relates to childhood health inequities. There were two phases in the coding process: 1) develop a first draft of the codebook based on a sample of interviews and 2) analyze all 45 interviews using a refined codebook.

Phase 1 Coding

The coding team (initially comprised of three qualitative researchers) was both interdisciplinary and multi-ethnic, which is integral to our process as it brought different perspectives and insights to the analysis. Two of the three coders were also involved in the documents review of health environment and social context information described above. The three-person team read an initial set of ten randomly selected interviews to develop conceptual categories (“codes”) to fit the interview data. This included use of open-coding procedures and comparison of codes among the coders to verify their descriptive content and confirm that they were grounded in the data. The coders also used analytic memo writing to facilitate their individual analysis and interpretation of the data, which in turn informed the iterative and collaborative coding process. Through a consensus coding process, the codes were collapsed and organized in a codebook consisting of three large themes, 10 codes, and 20 sub-codes.

Phase 2 Coding

At this point a community organizing consultant joined the coding team to further refine the codebook and confirm that the codes aligned with social justice organizing principles and were reflective of community organizing philosophies and strategies. The organizing expert, while not part of the CCHE Network, had over 10 years of experience as a community organizer and held a leadership position at a social justice CBO. Their insights at both the organizing and operational levels helped us to add nuance and precision to the codebook and ensure we included appropriate indicators of social justice community organizing concepts. Using the refined codebook, the four-person team then recoded the initial ten interviews and the community organizing expert coded the remaining thirty-five interviews.

In August 2017, preliminary analyses were presented to the CCHE Strategic Advisory Committee (consisting of childcare providers and educators, community organizers, and childhood health advocates) to vet our findings. The providers in the room affirmed many of our findings related to current social conditions and barriers to childhood health in their respective communities. For example, key informants reported concerns with school discipline practices towards youth of color as young as five years old. Community organizers from California and Colorado validated this finding and elaborated on the problem of “school push-out” occurring in their communities, and how they are organizing parents and educators to end these harmful policies. The themes from the codebook capture the realities of conducting health equity and social change work in underrepresented communities.

Step 5: Data Dissemination

One goal of the landscape analysis process was to inform the social justice and organizing community about relevant work that is happening in other parts of the country in order to broaden the network and facilitate coalition building. This meant identifying ways to share findings beyond traditional research forums (i.e., conference presentations, academic journals), so that insights gained from the interviews could reach our intended audience. In consultation with project partners, and in accordance with the CBPR principle of shared decision-making regarding dissemination of findings, we developed 45 snapshot profiles – brief one- to two-page handouts tailored to each organization’s specific community and cultural context that can be easily shared and utilized by practitioners. In addition, Praxis disseminated the snapshots via their website ( https://www.thepraxisproject.org/ ) to raise awareness and understanding of community organizing efforts vis-à-vis social determinants of health.

The snapshots highlight the interplay between children’s health, local community conditions and critical issues, organizational wellness and safety efforts, and organizational best practices and accomplishments. In addition to the key informant interviews themselves, several other data sources were used to provide relevant contextual information including regional health statistics (e.g., local health department), administrative data (e.g., census), organizational websites and social media pages, and other public documents and records (e.g., health reports, journal articles, news articles). The snapshots contain brief descriptions of the following: 1) organizational overview including their history, focus areas, and geographic location; 2) mission and/or vision statement; 3) constituencies served; 4) local conditions or barriers in the social and physical environment impacting children’s health in the target community; 5) prevalence of key childhood health indicators, such as childhood obesity, low birth weight, physical activity, and asthma affecting children in the target community; 6) allies or partnerships with other community groups engaged in innovative work around childhood health; 7) ongoing health and wellness efforts, programs, or campaigns at the organization; 8) accomplishments (e.g., policy wins) related to community wellness and safety; 9) community-defined “best practices” or strategies used by the CBO to create long-term community change; and 10) contact information, including website and social media. Direct interview quotes are included to nuance and augment the data. Each snapshot was verified and approved by the key informant before being shared with Praxis, who designed the visual layout. The final snapshots were then shared back with the CBOs for their own use as promotional material.

The landscape analysis revealed challenges familiar to low-income communities of color including limited employment opportunities, lack of affordable housing, unsafe neighborhood conditions, and poor education resources. And although the social and environmental conditions are culturally and contextually distinct within each community, they are also intertwined, complex, and multi-faceted. This has resulted in profound collective and lasting social consequences on the health of children, families, and communities.

Our findings confirm the important role that community-based organizations play in supporting childhood health, regardless of whether an organization’s stated focus is children and/or health. For example, during their key informant interview, an organizer for housing justice and tenant rights described how the stress and fear experienced by families dealing with landlord harassment and neglect trickles down from the parents to the children, contributing to emotional and physical health issues among young children (e.g., anxiety, trouble sleeping, stomach aches, etc.). Organizers in this setting provide tangible and emotional support to families facing eviction.

An unexpected finding was the extent to which community organizing CBOs in our sample serve as a part of the social safety net for poor and working families by providing and/or linking their constituents to support services and resources (given their diverse and immense individual and community needs). One important implication of these findings is to consider holistic community organizing approaches that account for culture and context when attempting to improve childhood health. For example, the community organizers we spoke with identified innovative solutions to these significant challenges, including the practice of leveraging social services (e.g., child care, food pantries) and base-building activities (e.g., youth leadership development) to involve residents and young people in direct-action campaigns. By integrating strategies, organizers help build community power while simultaneously addressing the most pressing needs in the community. These findings challenge conventional funding mechanisms, which can reinforce silos rather than support the integrated way work happens on the ground.

Strengths and Limitations of the Landscape Analysis Approach

A strength of the landscape analysis process was the stratified sampling procedures used to generate a diverse sample of key informants representing various ethnic/racial constituencies and geographic regions. The key informant interviews with community-organizing leaders illustrated the realities of social change efforts in underrepresented communities and provided concrete strategies that can be shared with other organizers.

Another strength is that the method was tailored to encompass CBPR principles and practices including trust and relationship building, collaboration, and centering community knowledge (Minkler et al. , 2019; Wallerstein & Duran , 2010) . First, the deep and long-standing relationships among Praxis, the CCHE Collaborative members, and the key informants was crucial to our sampling and data collection strategies. Not only was insider knowledge necessary for us to become aware of certain CBOs, especially newer organizations, but the well-regarded reputations of Praxis and CCHE within social justice organizing circles contributed to organizers’ willingness to talk with us. In essence, they “vouched” for us as researchers who were committed to social justice and could be trusted to honor the data and respect the communities that shared their stories. Second, the CCHE Collaborative was essential in the development and refinement of the data collection tools—their familiarity with the community-organizing context and subject-matter expertise ensured relevant and appropriate questions were included in our interview protocol, which yielded rich data and new insights.

A common challenge cited by practitioners of CBPR is the time-consuming and labor-intensive nature of collaborative, community-based work (Wallerstein & Duran , 2006) . We found this to be the case with the landscape analysis process as well. The development of our sampling strategy and instruments, data collection, and data analysis were all collaborative processes that took place over several months to ensure that we integrated feedback from project partners. Our methodology relied on in-depth interviews, which are time-consuming and create a significant barrier to data collection. In fact, we encountered challenges in making contact and scheduling interviews with some key informants who did not have time to be interviewed or simply were not interested in participating. When asked for names of potential key informants as part of our snowball sampling procedure, one Executive Director told the interviewer he doubted any of the names he provided would make time for an interview because there is too much day-to-day organizing work. A serious consideration for community-engaged researchers is how to lessen the burden on already overworked leaders in social justice community organizing movements. We attempted to mitigate this barrier by providing a tangible resource, the organizational snapshot profile, as an incentive for participation. Data analysis was also labor intensive as our multidisciplinary data analysis team went through several rounds of coding and revision.

Additionally, resource constraints limited the number of expert advisors we were able to include on our team. Although youth were involved at the level of the actual organizations (i.e., as members and leaders) included in the landscape analysis, they were not directly involved in the instrument development and data analysis process. Similarly, we were not able to include more than one community-organizing expert in the data analysis process. That said, the community-organizing expert played a significant role in revising our codebook and framing our findings given their knowledge of processes, constructs, and trends in the field. Specifically, they directed attention to the “integrated strategies” that CBOs are using (i.e., combining direct service and direct action) as a noteworthy pattern in our data that has implications for the broader field.

Participatory methods like landscape analysis offer a useful tool for applied public health researchers to produce big-picture assessments that can aid in identifying trends and promising practices across a large sample, without sacrificing the richness of individual-level qualitative data. Participatory research increases the ability to authentically capture the factors affecting health and health inequities in communities of color and marginalized communities by revealing the drivers of social determinants of health that are often overlooked in traditional research. The findings underscore the importance of a large, well-established network like CCHE that serves as a critical hub for connecting seemingly dissimilar organizations and supporting local, community-based organizing and advocacy to directly confront racial injustice and health inequities. For close to a decade, the CCHE project has contributed to the general knowledge about the social determinants of health nuanced to community context, culture, and place and is helping to shift the conventional wisdom about what constitutes “public health” work to be more inclusive of grassroots community-organizing strategies and activities (Douglas et al. , 2016; Grills et al. , 2014; Subica et al. , 2016) .

Grassroots CBOs play a critical role in advancing health equity through supporting individual and collective agency among historically disenfranchised communities of color (e.g., building strategic alliances with other like-minded groups to leverage power and shape decision making) and fighting for systems and policy changes using a racial justice and health equity framework that takes into account the socio-cultural-political context of their local communities. Community organizers use landscape analysis to deepen understanding of the structural causes of social conditions and to mobilize and engage those most affected in the definition of issues and construction of solutions (i.e., policy and systems change campaigns) to shift power and transform systems. Therefore, any public health strategy that seeks to address root causes and promote sustainable changes that improve health must work with, and through, these grassroots CBOs. Closing the gaps in health inequities to achieve social justice and health equity requires public health to pursue nontraditional methodologies like community organizing.

How to Run a Landscape Analysis

By Chelsea • May 2, 2018

No organization is an island. While each and every mission-driven organization is unique, many aspects of your work are shared by other organizations. Having similar goals, objectives, and core audiences can make it difficult to know how to stand out. One of the most efficient and cost-saving ways to gain such insight is by understanding and navigating the landscape you operate in.

What is a Landscape Analysis?

Basically, a landscape analysis allows you to learn about your competitor landscape:

Who else is in your sector and doing what you do or want to do? What are they doing well? Where do they fall short (and subsequently, where can you fulfill a need)? What isn’t being done at all?

All of these questions can be answered by a landscape analysis. The process breaks down into three steps, which we explore in more depth later on:

- Identification of key organizations in a field, sector, or location

- Classification of those organizations by relevant characteristics (organization type, target audience, mission)

- Evaluation of how they’re performing relative to the focus of your review

Why is it important?

A better understanding of the broader context in which you are operating can help you design your strategy to maximize your impact. Some benefits can be:

Saving Time & Money

Research can often be an under-resourced line item in a mission-driven organization’s budget. But the upfront investment into a landscape analysis can pay dividends over time by helping avoid problems you might otherwise face, and ensure your offerings are the most effective and unique to grab your audience’s attention and achieve your organizational goals.

Innovating and Improving

Seeing how others are providing a similar offering often sparks creative ideas on your team for how to improve and/or innovate the work.

Making Actionable Decisions

Stuck on how best to move forward or improve your offerings? Knowing what others are doing can help dislodge any of that and bring action items more clearly into focus.

Identifying Opportunities

Differentiating your organization from others in the space is key to success, and a landscape review allows you to identify those areas where you can either outperform others or fill a gap that no one is filling yet. You can quickly get up to speed on everything from a new field to a new geographic focus, from new trends to not-yet identified competitors.

This was where one of our most recent projects with AnitaB.org took us.

AnitaB.org is on a mission to connect, inspire, and guide women in computing and organizations that view technology innovation as a strategic imperative. The organization supports women working in technical fields, as well as the companies that employ them and the academic institutions that educate them. Each year AnitaB.org hosts the Grace Hopper Celebration , a three-day event which draws over 18,000 women together, and it serves as one of the most powerful ways AnitaB.org carries out its mission.

Natania and Mimi attended GHC as part of ThinkShout’s research and introduction to AnitaB.org .

They approached ThinkShout with the goal to provide the same kind of powerful experience and support to women in technology a full 365 days a year, and not just the three days of the Grace Hopper Celebration. Our assignment was to research whether any organization was already providing this kind of support and a sense of community to women in tech, and to also identify online platforms that deliver similar support to their users in unique and innovative ways.

How do you do a landscape analysis?

1. Understand You, Your Goals, and Everyone You Want to Engage

The first step is to be clear about your organizational goals, your target audiences, and what those audiences are looking for. This will ensure that you ask the right questions in your analysis and end up with accurate insights. If you haven’t done so before, conducting user research may help uncover what your audiences really need that they are not currently getting, and can also be great preliminary research into the organizations to include in your landscape analysis (keep an eye out for a future blog post about that!).

Mimi and Chelsea sorted through features to determine how they related to the client/project goals.

For AnitaB.org, we actually started out organizing our thinking around the kind of concrete features that would comprise an online engagement platform — a user’s profile, private messaging and groups, and event functionality, for example. But we stepped back and re-oriented our goal to something that was bigger picture and much more specific to our client’s particular needs: how do we connect women meaningfully and help them advance in their career and as advocates for women in tech via an online platform?

2. Set Parameters

Once you have your goals in hand, you want to determine the parameters, or the criteria, of your analysis: who do you include? Who do you not? You may want to consider:

- Whether organization type matters

- Where there is issue area or mission overlap

- Whether to set a narrow set of parameters within a broad context, or a broad set of parameters within a narrow context

For AnitaB.org, we set a narrow set of parameters within a broad context. We chose to seek out organizations who were meeting their own goals well — these were by and large not the same goals as our client’s — but who did so using similar strategies to AnitaB.org: facilitating connections between people who may otherwise not meet, and providing opportunities for mentorship, professional development, and career advancement.

Photo credit: #WOCinTech Chat on Flickr

Quick Tip: It may be tempting to skip the first two steps and jump right into step 3, but how can you find what you’re looking for if you don’t know what you’re trying to find? A bit more time upfront will result in more efficient research results and outcomes from your analysis.

3. Brainstorm & Vet Potential Organizations

Now that you know what you are looking for, go out and think about every organization that might fit your criteria here! This isn’t the editing stage — that comes next — so be as creative as you can while brainstorming which organizations might fit your criteria. Then, spend a brief time reviewing each one against your parameters, and see how they stack up against each other.

ThinkShout created a list of over 20 organizations that fit our client’s parameters, and it was a diverse list: no two organizations were delivering the same product, but they all had common aspects to their work that mapped back to our goals for our client. We spent about an hour exploring each one and ranking how well it performed against our criteria. Those that ranked highest moved forward in our analysis.

Quick Tip: If you are improving or evolving current offerings, be sure to include your own organization in the next step!

4. Examine Strengths, Weaknesses, and Opportunities of Select Organizations

Time and budget typically don’t allow for a full in-depth analysis of more than a handful of organizations. But you can still get a lot of value of doing a deep dive into those select few. Spend a while longer getting to know your top-ranked organizations, and really uncover those areas where they’re performing well and not so well. An analysis across your select organizations may reveal those opportunities where no one is currently providing any offerings.

Some platforms we included were Italki, NTEN, and Doximity.

At this stage of our client project, we had six platforms that we each spent an additional three hours of time on; getting to know how they facilitated new connections between their users, connected mentors with mentees, delivered professional development content, and promoted career opportunities. In doing so, we came away with many valuable insights that informed the development of the final phase of our project, creating a recommended set of core features for a new online platform. Those insights included:

- Unique and specific features AnitaB.org could take inspiration from to build their own platform,

- Offerings that were so strongly provided by other organizations that it didn’t make sense for our client to invest resources in developing and trying to compete against, and

- A confirmation of market opportunity.

What Could a Landscape Analysis Do For You?

Whether it’s a new website, program, or offering that you’re considering, you don’t want to invest resources in something that someone else is already doing so well that you have no chance to compete with them. On the flip side, if you want to venture into an area that many have struggled with, you want to know what they’ve tried so you can learn their lessons and avoid their same mistakes. After all, your mission, at the end of the day, is at stake. You want to maximize your impact while minimizing cost. A little research in the short-term will go far in ensuring the long-term success of your efforts.

ThinkShout is Here to Help

Are you considering a landscape analysis for your organization but not sure if you have the bandwidth to take on the work? We’d love to help you! Our team is comprised of former nonprofit staff and agency veterans who have decades of experience working with nonprofits that vary in size, budgets, and goals, so we know what it’s like to be in your shoes. We are here to help you achieve your goals and be your strategic partner. To get started, let us know a little more about your needs.

European Research Infrastructures in the International Landscape

What is landscape analysis?

Landscape analysis is a type of organisational analysis. The concept focused on finding a cohesive and consistent view of the main organisations and initiatives in some analysed area of operations and analysing chosen key aspects of them. In many business-oriented situations this kind of analysis is a part of a business plan – finding out on potential collaborators, market analysis, competitors, etc.

The key elements of a landscape analysis are defining users (stakeholders), the scope (what kinds of organisations are analysed, i.e. the targets of the analysis), methods used, and parameters to study.

In the case of RISCAPE, these elements are

- The users of the RISCAPE analysis are meant to be the primarily national and regional funding agencies, the European Commission services, ESFRI and other national and international bodies developing science infrastructures. Secondary user groups are European and international research infrastructures, researchers and users of the research infrastructures.

- The scope of the RISCAPE analysis is focused on international research infrastructures . As there is no global definition on what actually is a research infrastructure, we define in the Methods workpackage a common scope definition. (see page What are research infrastructures?)

- Methods of the RISCAPE analysis are based on interviews, information collecting from existing available sources (reports, previous landscape analyses, etc.), questionnaires and reaching to the European ESFRI research infrastructures.

- Parameters of the study are still open. Any landscape analysis must include some basic parameters regarding to the existence of an organisation (research infrastructure), but the rest of the parameters are strongly dependent on the needs of the Stakeholders .

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Journal Menu

- Sustainability Home

- Aims & Scope

- Editorial Board

- Reviewer Board

- Topical Advisory Panel

- Instructions for Authors

- Special Issues

- Sections & Collections

- Article Processing Charge

- Indexing & Archiving

- Editor’s Choice Articles

- Most Cited & Viewed

- Journal Statistics

- Journal History

- Journal Awards

- Society Collaborations

- Conferences

- Editorial Office

Journal Browser

- arrow_forward_ios Forthcoming issue arrow_forward_ios Current issue

- Vol. 16 (2024)

- Vol. 15 (2023)

- Vol. 14 (2022)

- Vol. 13 (2021)

- Vol. 12 (2020)

- Vol. 11 (2019)

- Vol. 10 (2018)

- Vol. 9 (2017)

- Vol. 8 (2016)

- Vol. 7 (2015)

- Vol. 6 (2014)

- Vol. 5 (2013)

- Vol. 4 (2012)

- Vol. 3 (2011)

- Vol. 2 (2010)

- Vol. 1 (2009)

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

Landscape Analysis, Planning and Regional Development

- Print Special Issue Flyer

Special Issue Editors

Special issue information, benefits of publishing in a special issue.

- Published Papers

A special issue of Sustainability (ISSN 2071-1050). This special issue belongs to the section " Social Ecology and Sustainability ".

Deadline for manuscript submissions: closed (31 May 2022) | Viewed by 37280

Share This Special Issue

Dear Colleagues, Landscape analysis and planning have been facing more and more challenging goals, with the rapid evolution of socioeconomic and environmental processes, the more and more strict connections between urban and rural areas and the increasing multifaceted nature of many landscapes, the increasing need of activating virtuous circular processes among the various landscape resources, the need of more and more integrated policies and plans at the various scales. Landscape identities and values represent strategic assets for regional development policies and programs, which must increasingly address the challenge of creating more inclusive and resilient societies, with the aim to increase the competitiveness of all regions. This poses both conceptual challenges related to the set-up of regional planning and development models, as well as methodological challenges about the implementation of plans, policies and programs.

The Special Issue addresses new challenges and cross-cutting issues in the landscape analysis and planning and regional development domains, with reference both to rural, periurban and urban landscapes, and both everyday and outstanding or degraded landscapes, in line with the European Landscape Convention. The Special Issue welcomes papers addressing innovative approaches and frameworks in the landscape analysis and planning and regional development fields; papers focusing on new methodological and technological challenges for combining development, social, environmental and economic sustainability, and landscape protection and enhancement; papers addressing the analysis of territorial challenges and the identification of innovative site-specific territorial policies aimed at multi-level, multi-sectoral and evidence-based regional development, from cities to rural areas, at various territorial scales; papers about the evaluation of the impact of landscape planning and regional development policies and plans for urban and rural development, support to policy making and decision making. Papers can also focus on relevant territorial or subject-based case studies, comparative studies, studies using multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches, integrated approaches considering the various landscape features and the various interconnected processes and actors, participatory processes and experiences involving different actors and sectors (public and private, citizens and associations, local and regional organizations and public administrations, etc.)

You may choose our Joint Special Issue in World .

Prof. Patrizia Tassinari Prof. Daniele Torreggiani Guest Editors

Manuscripts should be submitted online at www.mdpi.com by registering and logging in to this website . Once you are registered, click here to go to the submission form . Manuscripts can be submitted until the deadline. All submissions that pass pre-check are peer-reviewed. Accepted papers will be published continuously in the journal (as soon as accepted) and will be listed together on the special issue website. Research articles, review articles as well as short communications are invited. For planned papers, a title and short abstract (about 100 words) can be sent to the Editorial Office for announcement on this website.

Submitted manuscripts should not have been published previously, nor be under consideration for publication elsewhere (except conference proceedings papers). All manuscripts are thoroughly refereed through a single-blind peer-review process. A guide for authors and other relevant information for submission of manuscripts is available on the Instructions for Authors page. Sustainability is an international peer-reviewed open access semimonthly journal published by MDPI.

Please visit the Instructions for Authors page before submitting a manuscript. The Article Processing Charge (APC) for publication in this open access journal is 2400 CHF (Swiss Francs). Submitted papers should be well formatted and use good English. Authors may use MDPI's English editing service prior to publication or during author revisions.

- Landscape analysis and planning

- socioeconomic and environmental processes

- circular processes

- integrated policies and plans

- city and the countryside

- natural and cultural assets

- production and socio-economic processes

- landscape identity

- landscape values

- regional development policies and programs

- inclusive and resilient territories and societies

- approaches and frameworks

- methodological and technological challenges

- territorial development

- social, environmental and economic sustainability

- landscape protection and enhancement

- site-specific territorial policies

- interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches

- integrated plans and programs

- participatory processes

- multi-actor and multi-sector plans and programs

- policy making

- decision making

- Ease of navigation: Grouping papers by topic helps scholars navigate broad scope journals more efficiently.

- Greater discoverability: Special Issues support the reach and impact of scientific research. Articles in Special Issues are more discoverable and cited more frequently.

- Expansion of research network: Special Issues facilitate connections among authors, fostering scientific collaborations.

- External promotion: Articles in Special Issues are often promoted through the journal's social media, increasing their visibility.

- e-Book format: Special Issues with more than 10 articles can be published as dedicated e-books, ensuring wide and rapid dissemination.

Further information on MDPI's Special Issue polices can be found here .

Published Papers (12 papers)

Jump to: Research , Review

Jump to: Editorial , Review

Jump to: Editorial , Research

Further Information

Mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

Landscape analysis

- Reference work entry

- Cite this reference work entry

- Stuart A. Harris

Part of the book series: Encyclopedia of Earth Science ((EESS))

54 Accesses

1 Citations

Landscape may be defined as a stretch of country as seen from a particular vantage point. The landscape is made up of rock with its “mantle” of weathered material (saprolite) and soil, together with any vegetation cover and any streams, rivers, lakes, snow or ice that may be present. There can be a tremendous range of variation from one place to another. In the humid tropics, an aerial view will be restricted to the canopy of the dense tropical rain forest. In deserts, the landscape may be dominated by bare rock, while lowlands which have just been deglaciated may be dominated by small lakes and erratic blocks.

Just as the landscape is highly variable, so may be the vantage point. This may be a point on a high hill, perhaps from an aircraft, or it could be virtually at the limit of resolution as in the case of the view from a satellite.

Landscape analysis is the subdivision of landscape for some purpose or other. It may be for some scientific study such as the nature and origin of the...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Chorley, R. J., 1962, Geomorphology and general systems theory, U.S. Geol. Surv. Profess. Paper 500B, 10 p.

Google Scholar

Davis, W. M., 1899, The geographical cycle, Geogr. J., 14, 481–504.

Gilbert, C. K., 1880, Report on the geology of the Henry Mountains, Second ed.,U.S. Govt. Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 170 pp.

Herweijer, S., 1965, Problems of Regional Planning and Development (Netherlands), in International Conference on Regional Development and Economic Change, pp. 101–110, Department of Economics and Education, Toronto.

Jones, D. K., Merton, L. F. H., Poore, M. E. D., and Harris, D. R., 1958, Report on Pasture Research, Survey and Development in Cyprus, Govt. of Cyprus, 88 pp.

Mabbutt, J. A., and Stewart, G. A., 1963, The application of geomorphology in resource surveys in Australia and New Guinea, Revue de Géomorphologie Dynamique, 14, 97–109.

Cross-references

Base Level ; Cycles, Geomorphic ; Desert and Desert Landforms ; Drainage Patterns ; Geomorphic Maps ; Land Mass and Major Landform Classification ; Land Systems ; Open Systems—Allometric Growth ; Physiographic or Landform Maps ; Process—Structure—Stage ; Quantitative Geomorphology .

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 1968 Reinhold Book Corporation

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Harris, S.A. (1968). Landscape analysis . In: Geomorphology. Encyclopedia of Earth Science. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-31060-6_216

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-31060-6_216

Publisher Name : Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN : 978-0-442-00939-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-540-31060-0

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Observatory

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Publications /

Performing a landscape analysis: understanding health product research and development

a quick guide

Market Mapping and Landscape Analysis

Identifying all the key players in a field, sector or geography and classifying them by relevant characteristics (type, revenue, etc.)

Market mapping and landscape analysis involves identifying the key players in a field, sector or geography and classifying them by relevant characteristics (e.g., type of organization, target beneficiary). This helps nonprofits understand the broader context in which they are operating, and design their strategy accordingly to maximize their impact.

Nonprofit Resources

📄 Get more of our best articles, tools, and templates on running a thriving nonprofit.

How it's used

Market mapping and landscape analysis can be used for a variety of purposes to help nonprofits chart their broader strategy and make critical decisions. It can be used to "get smart" on a new field or geography, discover important trends shaping a sector, or identify peers and collaborators. It allows organizations to identify which topics, approaches or beneficiaries are well served by existing organizations, as well as any white space where no organization is currently active.

Market mapping is especially useful for organizations considering significant expansion or shifts in focus, or those conducting a rigorous strategic planning process. It is also a key part of setting up a collective impact collaboration .

Subscribe to get Bridgespan's latest insights and research.

Methodology.

Nonprofit managers can follow four general steps to implement market mapping and landscape analysis:

- Crystallize objectives: The first step in conducting market mapping and landscape analysis is to identify the goals of the analysis and determine the key questions the analysis will help answer.

- Function (e.g. funder, regulator, intermediary, service provider)

- Approach (e.g. research, advocacy, knowledge dissemination, service provision)

- Organization type (e.g. nonprofit, government, university, for-profit)

- Topic (e.g. refugee resettlement, teenage pregnancy prevention, air pollution)

- Beneficiary (e.g. diabetes patients, preschoolers, Latinas)

- Geography (e.g. specific school districts, neighborhoods, cities, states)

- Decide on the critical information to gather: Identify the key data points to collect about each organization or actor. Many of these will be the dimensions identified above (e.g. geographic focus), but there will likely be others as well (e.g. links among organizations, size and number of beneficiaries served, outcomes data, etc.)

- Conduct targeted research: With goals and scope set, staff can conduct targeted research to map the selected field. Research methods may include brainstorming a list of organizations with key stakeholders, reviewing online of databases and existing literature, conducting surveys, and interviewing peers and other field stakeholders.

- Synthesize and draw out implications: Synthesize researched information to provide a clear landscape of the field or sub-field. From here, work with key stakeholders and senior leadership to discern insights and implications for the organization's strategy and work.

Related topics

- Strategic planning

- Benchmarking

- Collective impact collaborations

- Strategic alliances

- Mission and vision statements

- Intended impact and theory of change

Additional resources

How to Conduct and Prepare a Competitive Analysis This short, practical guide is written for a for-profit company but the ideas and lessons contained within it are easily transferred to a nonprofit organization.

The Strong Field Framework: A Guide and Toolkit for Funders and Nonprofits Committed to Large-Scale Impact This toolkit provides an introduction to the Strong Field Framework, which can be utilized by practitioners to assess a field and to propose recommendations for field-building activities.

Examples and case studies

Financing and Sustaining Out-of-School Time Programs in Rural Communities This article highlights the use of domain and field mapping of funding sources for rural out-of-school time programs.

Assessing California's Multiple Pathways Field: Preparing Youth for Success in College and Career The James Irvine Foundation commissioned a landscape analysis of the "multiple pathways" approach to high school education in California–a blend of rigorous academics and real-world experience that seeks to engage youth and help them graduate high school prepared for success in college and career.

Landscape analysis of Community-Based Organizations: Maniema, North Kivu, Orientale and South Kivu Provinces of Democratic Republic of Congo The first 18 pages of this report provide an excellent example of the insights and next steps an organization can learn from a landscape analysis. The introduction and methods sections also reveal how one can go about implementing a landscape analysis. The remaining pages provide examples of the insights produced by an in-depth landscape analysis.

Note: This page was originally featured in the Nonprofit Management Tools and Trends report (2015)

Related Content

Funding models, donor relationship management, performance measurement and improvement.

Conducting a Community Landscape Analysis

What is a landscape analysis.

A Landscape Analysis outlines the strengths, resources, and needs of a particular community. It provides a framework for designing a service and ensuring that it is embedded directly in the needs of the community.

Why should you conduct a Landscape Analysis?

Prior to starting any type of community program — whether a tutoring program or any other service — you should confirm that there is a need and a desire for the proposed program in the community you aim to serve. The information you gather through a Landscape Analysis will allow you to thoroughly map these community needs and desires, ensuring that they remain paramount when you design your program, set priorities, and make strategic decisions. A Landscape Analysis will enable your program to keep the actual needs of the community in mind at all times, rather than your own hypotheses about its needs. Doing this essential groundwork will aid in designing an effective tutoring program that the whole community values.

Who should be considered in a Landscape Analysis?

While there are no strict limits regarding who can be involved, here is some basic guidance about whose needs should be prioritized:

- Students and families who will likely benefit from the tutoring program. Ensure that you hear from a wide range of voices so that you can holistically understand the needs of the community of potential beneficiaries.

- Other stakeholders beyond students and families, such as teachers and school administrators, who will have a solid expert understanding of students’ needs for additional tutoring services.

- Other community members, or like-minded organizations that have a history operating in the community and can help you to carry out the assessment itself or assist with program design planning.

How do you conduct a Landscape Analysis?

The qualitative and quantitative data you collect will help you define your tutoring program’s necessary inputs, benchmark outputs, and desired impact. Here are some of the sources from which you may want to collect information:

- Interviews & Focus Groups: Solicit direct input from both the beneficiaries of tutoring (families and students) as well as other stakeholders (such as school administrators and teachers) to understand what needs they observe and experience. This will help you understand students’ academic context and where a tutoring program might fit in.

- Public Forums: Seek out public forums already happening that relate to the needs you have identified. Attend local school board meetings and other community gatherings to better learn the local political landscape.

- Observations: Directly observe and speak with those on the front line. Visit tutoring programs or similar services that already exist and see what they look like in action.

- Needs Surveys: Collect an easily-parsed set of data points by having community members rate proposed services and answer a few open-ended questions to help you understand the aggregate needs of the community.

- Existing Quantitative Data: Review and synthesize available data from sources such as: research studies that have already been conducted (e.g., recent research related to learning loss); publicly available resources such as US Census data about the community; and local school district records on student achievement and graduation rates.

Analyzing Your Findings

As you analyze findings, look for trends. Consider the following:

- For example, you may find that the community already has robust services for literacy programs in early elementary school that have supported students both in school and, with family participation, at home.

- Identifying gaps will help you design your tutoring program to fill them. For example, you may find that there are limited programs or services available to students who struggle in math in the secondary setting. If so, this may be where tutoring would be most beneficial.

- For example, you may have heard that there is a lower rate of involvement in after-school programs in secondary settings due to time constraints for youth that have taken on part-time work. This can help inform the design of your program. How will you ensure tutoring is available to students at a time when they can actually be involved?

- For example, you might learn that there are many university students in the area who have interest in working in the community, but there is no formal relationship between the school district and the local university. Your tutoring program could bridge this gap and leverage this local talent; accessing low-hanging fruit like this will help your program meet community needs efficiently.

- For example, you might learn that another tutoring program is starting up in the community or that state policy was just enacted that requires tutoring to be done by certified teachers. Identifying and taking into consideration any threats will help you both design and pitch your program.

Sharing Your Findings

You should produce a simple report you can use to present your findings both to the community and to additional stakeholders (such as funders). This report can serve as a summarizing tool to help you advocate for your tutoring program, directly connecting the development of your program to the needs of the community. A report typically includes the following:

- An overview of whose needs you considered in your Landscape Analysis.

- A description of the methods your program used to collect qualitative and quantitative data.

- A summary of the number and demographic characteristics of the individuals who contributed to the dataset, such as the number of individuals who completed a needs survey and a demographics overview of survey respondents.

- An outline of the process, including both its strengths and any challenges you may have faced. Openness about challenges is particularly important so that the reader has a holistic understanding when reviewing your report. For example, did you have difficulty achieving high completion rates for a survey? How might that skew your findings?

- A synthesis of key findings. This is where you would address the actual results and insights gained from the analysis you conducted, articulating the strengths, gaps, challenges, and opportunities in the community.

- A set of recommended next steps. Based on the Landscape Analysis, what are your recommendations? How should the design of the tutoring program adapt to address the specific needs of this particular community?

Additional Resources

The Community Toolbox, developed by the University of Kansas, lists a number of resources to support programs in developing a robust Landscape Analysis, sometimes referred to as a Community Needs Assessment .

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Data and Tools

- National Forest Service Library

Descriptive approaches to landscape analysis

| Authors: | R. Burton Litton Jr. |

| Year: | 1979 |

| Type: | General Technical Report |

| Station: | Pacific Southwest Research Station |

| Source: | In: Elsner, Gary H., and Richard C. Smardon, technical coordinators. 1979. Proceedings of our national landscape: a conference on applied techniques for analysis and management of the visual resource [Incline Village, Nev., April 23-25, 1979]. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-35. Berkeley, CA. Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Exp. Stn., Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: p. 77-87 |

Parent Publication

- Proceedings of our national landscape: a conference on applied techniques for analysis and management of the visual resource [Incline Village, Nev., April 23-25, 1979]

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Digg

Latest Earthquakes | Chat Share Social Media

Landscape transcriptomic analysis detects thermal stress responses and potential adaptive variation in wild brook trout during successive heatwaves

Extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, are becoming more frequent and intense as a result of climate change. Importantly, such extreme weather events can be more important drivers of extirpation and selection than changes in annual or seasonal averages and they pose a particularly large threat to poikilothermic organisms. In this study, we evaluate the thermal stress response of a coldwater adapted fish species, the eastern brook trout (*Salvelinus fontinalis*), to two successive heatwaves during July and August 2022.

Citation Information

| Publication Year | 2024 |

|---|---|

| Title | Landscape transcriptomic analysis detects thermal stress responses and potential adaptive variation in wild brook trout during successive heatwaves |

| DOI | |

| Authors | Tyler Wagner, Justin Waraniak |

| Product Type | Software Release |

| Record Source | |

| USGS Organization | Cooperative Research Units Program |

Related Content

Tyler wagner, phd, research fish biologist.

Advertisement

Supported by