Korean War: 4 SEQ Samples

The topic of the Korean War revolves around the reasons why it happened and whether it was a proxy war or just a civil war. These are just samples for students to refer to so that they have a model to use when answering a similar question.

For ease of download, I have included the pdf download in the box below.

Download Here!

1. Explain how post-war developments in Asia and Europe impacted Korea.

( P ) Post-WWII development in Asia impacted Korea as it led to the necessity to contain the spread of communism in the Asia-Pacific.

( E ) In October 1949, China turned communist, and China signed the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance in February 1950 with the Soviet Union. The communists viewed Korea as a potential platform to expand their global influence into the Asia-Pacific. Hence, Mao, the leader of communist China, focused his attention on the assistance of North Korea, which served as a counter-balance to the American influence in Japan. As a result, the National Security Council prepared a top-secret report called the NSC-68, stressing the importance of the Americans to contain the spread of communism on a global basis.

( E ) Thus, the communist take-over in China meant that Korea had become an essential platform over which both ideologies wanted to gain control to prevent the spread of communism.

( L ) Thus, post-war development made Korea a battleground in the Cold War.

( P ) Post-war development in Europe also significantly impacted Korea as the Soviets had gained greater leverage against Western powers.

( E ) In August 1949, the Soviet Union had successfully exploded its first atomic bomb. This event created atomic parity with the USA, meaning that the USA could not use atomic diplomacy as an effective threat against the Soviet Union.

( E ) Therefore, by early 1950, the Soviet Union was more inclined to support a possible North Korean invasion of the South. Kim Il-Sung approached Stalin for help in April 1950. Kim persuaded Stalin that he could easily and swiftly conquer the South. Stalin was concerned about the alliance of America and Japan and saw this as an opportunity to counter American influence in the region.

( L ) Thus, encouraged by their attainment of atomic parity, Stalin granted Kim permission to attack the South.

2. “The Americans were responsible for the escalation of the Korean War.” How far do you agree with this statement? Explain your answer.

( P ) The escalation of the Korean War was a result of American involvement.

( E ) The American intervention triggered China’s entry into the Korean War. By Oct 1950, UN troops had captured Pyongyang, occupied two-thirds of North Korea and reached the Yalu River. The presence of the UN troops was alarming to the Chinese, who felt threatened. Hence, when they ignored the repeated Chinese warnings, China joined the North Korean troops fighting the war.

( E ) Instead of being a civil war between North and South Koreas, it escalated into a more significant regional conflict – involving the USA and its allies on one side and North Korea and China and the USSR.

( L ) Therefore, US involvement had worsened the conflict.

( P ) However, the Americans were not to be blamed for the escalation of the Korean War.

( E ) This escalation was caused by both the Soviet Union and China. The Soviet Union and China supported Kim Il Sung’s government in North Korea. They sought to extend the communist sphere of influence. The Soviet Union also supplied the North with the weaponry that would help it to invade the South. Even though Stalin did not actively encourage Kim to invade the South, he eventually approved and asked China to help Kim. Kim Il Sung also did not take any direct action against South Korea until he had attained Stalin’s approval and support.

( E ) Therefore, the indirect involvement of the Soviet Union gave Kim the confidence to carry out the invasion, which led to the Korean War and escalated into a proxy war that saw Chinese troops and Soviet-trained troops in the war.

( L ) Thus, the Soviet Union and China were responsible for the Korean War.

( J ) In conclusion, the USA had its motivations for becoming involved in Korea as part of the Cold War against the Soviet Union. Hence, the USA is responsible for escalating the Korean War. The USA saw the North Korean invasion of South Korea as part of a Soviet plan to gain hegemony in Asia and eventually control the world. As a result, they led to a significant force to counter the North Korean advance, which also led to the involvement of Chinese troops and thus escalating the Korean War.

3. “South Korea was to be blamed for the Korean War.” How far do you agree with this statement? Explain your answer.

( P ) I agree that South Korea was to be blamed for the Korean War.

( E ) Border clashes between North Korea and South Korea were standard in 1949 and 1950. South Korea started these clashes to try to capture territory in North Korea. However, Syngman Rhee’s aggressive actions in planning border clashes backfired as they failed to achieve their goals. These failed invasions set the stage for North Korea’s invasion of the South in June 1950, which started the Korean War as they convinced North Korea of the ineffectiveness of the South Korean forces.

( E ) For example, South Korean warships on North Korean military installations provoked the North Korean army and resulted in fierce fighting by both sides. It also affected the USA’s goodwill towards South Korea and made the USA even more reluctant to send heavy weapons to South Korea. As a result, these border clashes revealed the weaknesses of the South Korean forces and their inability to launch successful offensive attacks. Desertions by South Korean soldiers were common and showed the unpopularity of Rhee’s regime.

( L ) Hence, South Korea was to be blamed for the Korean War.

( P ) However, I’m afraid I disagree with the statement because the Soviet Union was also blamed for the Korean War.

( E ) The Soviet Union supported North Korea’s invasion of South Korea. In early 1950, Stalin changed his mind and became more willing to help Kim’s invasion after developments like the communist victory in China, the Soviet explosion of the atomic bomb and the US Defensive Perimeter. Hence, the Soviet Union trained the North Korean army and provided military equipment such as tanks, guns and fighter planes. As a result, Soviet support for Kim’s invasion of South Korea led to the outbreak of the Korean War.

( E ) It helped make the North Korean army strong and gave them the military capability to launch an offensive attack on South Korea. It also gave Kim the confidence to invade South Korea because he could count on Stalin and Mao to help him should the invasion go wrong. Indeed, the North Korean forces launched a surprise attack on South Korea on 25 June 1950 and started the Korean War.

( L ) Hence, USSR was to be blamed for the Korean War.

( J ) In conclusion, I partly disagree that South Korea was responsible for the Korean War. South Korea incited frequent border clashes, which increased tensions between the two sides and made the conflict inevitable. Within this setting of increasing provocation by the South, the Soviet Union could offer its support to North Korea to mount the offensive and invade South Korea, which then triggered the outbreak of the Korean War.

At the same time, Soviet Union’s financial, military, technical and logistical support for North Korea did help to make the North Korean army strong. It gave them the military capability and the confidence to launch a successful offensive attack and invasion of South Korea. Hence, both sides are responsible for the Korean War

4. “The Korean War was mainly about the reunification of the two Koreas.” How far do you agree with this statement? Explain your answer.

( P ) The Korean War was mainly because of the desire by both sides for unification.

( E ) The Korean peninsula was halved at the 38th parallel after Japan had surrendered and Japanese soldiers left Korea. The USSR occupied the northern part temporarily and the USA the southern region. The United Nations called for an election in 1947 to establish a single government to reunite Korea, but the USSR refused to hold it. As a result, Korea splintered into two halves in 1949. Both Syngman Rhee (President of South Korea) and Kim Il Sung (President of North Korea) claimed the right to rule over Korea. As a result, there were border raids and conflicts between small groups of soldiers from the North and South.

( E ) Syngman kept provoking the North Koreans by launching raids into North Kore but failed. On the other hand, Kim was also determined to unite the Korean peninsula under communism. With the blessings of the USSR, the North Korean army invaded South Korea.

( L ) Thus, a civil war broke out with Koreans fighting against each other because both sides desired unification.

( P ) However, the Korean War was primarily due to interference by external powers.

( E ) The USSR was to be blamed for the Korean War. From the start, Stalin had backed Kim Il-Sung to run a communist government in Korea due to Stalin’s attempt to keep North Korea communist and spread communism across Asia. The USSR supplied North Korea with military equipment and training. As the leader of the communist bloc, it also encouraged China to back North Korea directly, which led to Kim daring to invade South Korea in 1950.

( E ) The USSR was thus to blame because it used Korea as the ground for a proxy war to demonstrate its superiority over its superpower rival – the United States.

( L ) Thus, the Korean War was because of external powers.

( P ) The US was also responsible for the outbreak of the Korean War.

( E ) During the Cold War, the US was determined not to let Korea fall into the hands of communism. When World War II ended, the US set up a democratic government in Korea. They even supported Syngman Rhee – a leader who abused his authority in South Korea.

( E ) As a result, when North Korean soldiers invaded South Korea, the US was determined to protect South Korea, activated a UN coalition force under its leadership, and intervened in the conflict, turning a civil war into an international problem.

( L ) Thus, the Korean War was a result of American intervention.

( J ) In conclusion, the Korean war was fundamentally a conflict between the two Koreas, as armed contact between the two Koreas had already occurred before the intervention of the US and the Soviet Union. The presence of the support of the superpowers merely sought to escalate the conflict to a new level given the increase in terms of military aid, resulting in North Korea’s crossing of the 38th Parallel in June 1950.

This is part of the History Structured Essay Question series. For more information on the Korean War, you can click here . For more information about the O level History Syllabus, you can click here . You can download the pdf version below.

Other chapters are found here:

- Treaty of Versailles

- League of Nations

- Rise of Stalin

- Stalin’s Rule

- Rise of Hitler

- Hitler’s Rule

- Reasons for World War II in Europe

- Reasons for the Defeat of Germany

- Reasons for World War II in Asia-Pacific

- Reasons for the Defeat of Japan

- Reasons for the Cold War

- Cuban Missile Crisis

- Reasons for the End of the Cold War

Critical Thought English & Humanities is your best resource for English, English Literature, Social Studies, Geography and History.

My experience, proven methodology and unique blend of technology will help your child ace their exams.

If you have any questions, please contact us!

Similar Posts

Rise of Stalin: 5 SEQ Samples

A common question for O Level history is the rise of Stalin. In this blog post, I have included some sample essay questions to help students score well.

Complete Sample Social Studies Issue 1 SRQ

Especially for students struggling with the Social Studies SRQ Issue 1 questions: Here are some sample essays! Ace your examination with these samples!

Social Studies SBQ (Source Based Questions)

Mastering Social Studies Source Based Questions is one of the most difficult tasks. Read on to find out more.

How to score 10/10 for Editing

Do you keep failing your Editing? How can you improve your Editing? Read on to find out how you can score full marks for the Editing section of the English paper.

2020 History Elective: Can we predict what is going to be tested?

In the upcoming 2020 History Elective examination, can we predict what is going to come out for the paper? Should we even try? Read on to find out more!

Social Studies Comparison Format

Is your child confused about the Social Studies Comparison question? If they are, read this blog to understand how to answer these sort of questions!

Korean War: History, Causes, and Effects Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Causes of korean war, the causes of korean war are generally, course of the conflict, effect of korean war to american foreign policy.

Bibliography

The Korean War which is termed as the forgotten war was a military conflict that started in June 1950 between North Korean who were supported by peoples republic of China backed by Soviet Union and South Korean with support from the United Nations and the American forces.

The war was an episode of cold war where by the United States of America and Russia were fighting ideologically behind the scenes by using South and North Korea as their battle zone. After the world war two, British and American forces set a pro-western government in the southern part of Korean Peninsula while the Soviet Union initiated a communist rule in the North. The net effect of these ideological differences was the Korean War.

The causes of the Korean War can be examined in two facets:

- Ideological

Politically, the Soviet Union wanted Korea to be loyal to Russia .This was because Korea was seen as a springboard that would be used to initiate an attack on Russia. Korean being loyal to Russia was a strategy to prevent future aggression.

The major cause of the war however, was difference in ideology between South and North Korea with Russia and America behind the scene. The two Korean zones established two separate governments with different ideologies. This were the major event that initiated the conflict In Korea.

American and Soviet military occupation in North and South Korea.

The American and Soviet forces occupation in Korea divided the country on ideological basis. These differences resulted to the formation of 38 th parallel which was a border between South and North Korea. This boarder increasingly became politically contested by the two functions and attracted cross boarder raids. The situation became even worse when these cross border skirmishes escalated to open warfare when North Korean army attacked South Korea on June 1950.The two super power majorly the American and Soviet Union acted by providing support and war equipment’s to the two conflicting sides.

Role of the America and Soviet Union in armament and military support to South and NorthKorea.

The Russians backed the communist regime in North Korea with the help of Kim Il-Sung and established North Korean Peoples Army which was equipped by Russian made war equipments. In South Korea, American backed government benefited from training and support from the Americans army.

Military and strategic imbalance between North and South Korea

The America and Russia failure to withdraw their troops by the late 1948, led to tensions between the two sides. By 1949, the American had started to withdraw its troops but the Russian troops still remained in North Korea considering that Korea lay as its strategic base.

This was followed by invasion of South Korea by the North Korean army because of the military imbalance that existed in the region. This forced the American to return back and give reinforcement to South Korea which was by then over ran by North Korean Army in support of the Russian troops.

Korea, a formally a Japanese colony before the end of the Second World War, changed hands to allied powers after the defeat of Japan in the year 1948. The Americans occupied the southern part of Korea while the Soviet occupied the Northern region. Korea by this time was divided along 38 th parallel which demarked the boarder of the two governments.38 th parallel was an area of 2.5-mile that was a demilitarized zone between north and South Korea.

In June 1950, the North Korean people army attacked South Korea by crossing 38 th parallel. On June 28 th the same year Rhee who was the then leader of South Korean evacuated Seoul and ordered the bombardment of bridge across Han River to prevent North Korean forces from advancing south wards.

The inversion of South Korea forced Americans to intervene and on June 25 th 1950, United Nations in support of South Korea, jointly condemned North Korea’s action to invade the South. USSR challenged the decision and claimed that the Security Council resolution was based on the American intelligence and North Korea was not invited to the Security Council meeting which was a violation of the U.N. charter article 32.

North Korea continued its offensive utilizing both air and land invasion by use of about 231,000 military personnel. This offensive was successful in capturing significant southern territories such as Kaesong, Ongjin, chuncheon and Uijeonghu.

In this expedition, the North Korea people’s army used heavy military equipment such as 105T-34 and T-85 tanks, 150 Yak fighters and 200 artillery pieces. The South Korean forces were ill prepared for such offensive and within days they were overran by the advancing Northern army. Most of Southern forces either surrendered or joined the Northern Korean army. In response to this aggression, the then American president Henry Truman gave an order to general Mac Arthur who was stationed in Japan to transfer the troops in Japan to combat in Korea.

The battle of Osan was the first involvement of the American army in the Korean war. The war involved a task force comprised of 540 infantry men from 24 th infantry division on July 5 th 1950. This task force was unsuccessful in its campaign to repel the North Korean army and instead suffered a casualty of 180 soldiers of whom were either dead, wounded or taken prisoner. The task force lacked effective military equipment to fight the North Koreans T-34 and T-85 tanks. The American 24 th division suffered heavy loses and were pushed back to Taejeon.

Between August and September 1950, there was a significant escalation of conflict in Korea. This was the start of the battle of Pusan perimeter. At this battle, the American forces attempted to recapture then taken territories by the North Korean army. The United States Air force slowed North Korean advances by destroying 32 bridges.

The intense bombardment by the United States air force, made North Korean Units to fight during the nights and hide in ground tunnels during the day. The U.S. army destroyed transportation hubs and other key logistic positions which paralyzed North Korean advances.

Between October and December 1950, the Chinese entered the war on the side of the North Koreans. The United States seventh fleet was dispatched to protect Taiwan from people’s Republic of China under Mao Zedong. In 15 th October 1950, Charlie Company and 70 th Tank battalion Captured Namchonjam city and two days later Pyongyang which was the Capital of North Korea fell to the American 1 st cavalry division.

The first major offensive by China took place on 25 October by attacking the advancing U.N. forces at Sino-Korean border. Fighting on 38 th parallel happened between January and June 1951 when the U.N. command forces were ambushed by Chinese troops. The U.N. forces retreated to Suwon in the west.

On July 10 th 1951, there was a stalemate between the two warring sides which led to armistice being negotiated. The negotiation went on for the next two years. The armistice deal was reached with formation of Korean demilitarized zone ending the war. Both sides withdrew for their combat position. The U.N. was given the mandate to see a peaceful and fair resolution of the conflict in the effort to end the war. The war resulted to about 1,187,682 deaths and unprecedented destruction of property.

The Korean War on the side of Americans perpetuated the Truman’s doctrine which was of the opinion that Russia was trying to influence the world with forceful communist ideology and therefore the United States of America would help any country that was under threat of communist.

The Korean conflict also brought into focus in future efforts to win communism from spreading allover the world. The United States realized that the best solution to stop the spreading of communism ideology was to be military in nature. The war also made America to recognize China as a powerful military might in Asia. Future diplomatic actions would need to take into account Chinas potential might.

After the war, military assistance was provided to Philippine government, French Indochina and Taiwan with the motive to contain the spread of communism in Asia. This military assistance would extend also in Europe to country under communist threat of occupation.

Feldman, Tenzerh. The Korean war . Minneapolis: Twenty-First Century Books, 2004.

Fitzgerald, Brian. The Korean war: American’s forgotten wa r. Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2006.

Stueck, William. The Korean war : An international history. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1997.

- Ethic of War as the Way Avoid the Conflicts

- Burning Down of the Village in Platoon

- The Impact of Events in the Middle East on American Foreign Policy 1980s

- Homeland Security & Ethical Criminal Investigations

- Current Trends Affecting Global Hospitality Industry

- Why U.S. Troops Should Stay in Afghanistan

- An Individual’s Opinion Poisons a Nation

- The Libyan Conflict Explained

- Lehrack, Otto. First Battle: Operation Starlite and the Beginning of the Blood Debt in Vietnam Havertown, PA: Casemate, 2004

- The Significance of the Korean War

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, October 10). Korean War: History, Causes, and Effects. https://ivypanda.com/essays/lees-korean-war/

"Korean War: History, Causes, and Effects." IvyPanda , 10 Oct. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/lees-korean-war/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Korean War: History, Causes, and Effects'. 10 October.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Korean War: History, Causes, and Effects." October 10, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/lees-korean-war/.

1. IvyPanda . "Korean War: History, Causes, and Effects." October 10, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/lees-korean-war/.

IvyPanda . "Korean War: History, Causes, and Effects." October 10, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/lees-korean-war/.

Home — Essay Samples — War — Korean War

Essays on Korean War

Korean war essay topics and outline examples, essay title 1: the korean war (1950-1953): uncovering the origins, cold war context, and global implications.

Thesis Statement: This essay delves into the complex origins of the Korean War, the Cold War context that fueled the conflict, and the far-reaching global implications of the war, including its impact on international alliances and the division of Korea.

- Introduction

- Background and Historical Context: Pre-war Korea and Its Division

- The Cold War Setting: U.S.-Soviet Rivalry and Proxy Wars

- The Outbreak of War: North Korea's Invasion and International Response

- The Course of the Conflict: Battles, Truce Talks, and Stalemate

- Global Implications: The Korean War's Impact on East Asia and International Relations

- Legacy and Repercussions: The Division of Korea and Ongoing Tensions

Essay Title 2: The Korean War's Forgotten Heroes: Examining the Role of United Nations Forces and the Armistice Agreement

Thesis Statement: This essay focuses on the often-overlooked contributions of United Nations forces in the Korean War, the complexities of the Armistice Agreement, and the enduring impact of the war on Korean society and international peacekeeping efforts.

- The United Nations Coalition: Multinational Forces in Korea

- The Armistice Negotiations: Challenges, Agreements, and Ongoing Tensions

- Forgotten Heroes: Stories of Courage and Sacrifice

- Korean War Veterans: Their Post-War Experiences and Commemoration

- Peacekeeping and Reconciliation Efforts: The Role of the United Nations

- Implications for Modern International Conflict Resolution

Essay Title 3: The Korean War and the Origins of the Cold War: Analyzing the Impact on U.S.-Soviet Relations and Global Alliances

Thesis Statement: This essay explores how the Korean War influenced U.S.-Soviet relations, the formation of military alliances such as NATO and the Warsaw Pact, and the Cold War's evolution into a global struggle for influence.

- The Korean War as a Catalyst: Escalation of Cold War Tensions

- Military Alliances: NATO, the Warsaw Pact, and the Globalization of the Cold War

- The U.S.-Soviet Confrontation: Proxy Warfare and Diplomatic Efforts

- International Response and Support for North and South Korea

- The Aftermath of the Korean War: Paving the Way for Future Cold War Conflicts

- Assessing the Korean War's Long-Term Impact on U.S.-Soviet Relations

The Korean War – a Conflict Between The Soviet Union and The United States

The local and global effects of the korean war, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Role of The Korean War in History

The origin of the korean conflict, the role of the battle of chipyong-ni in the korean war, the korean war and its impact on lawrence werner, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Historical Accuracy of The Book Korean War by Maurice Isserman

Solutions for disputes and disloyalty, depiction of the end of the korean war in the film the front line, the impact of war on korea.

25 June, 1950 - 27 July, 1953

Korean Peninsula, Yellow Sea, Sea of Japan, Korea Strait, China–North Korea border.

China, North Korea, South Korea, United Nations, United States

Korean War was a conflict between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and the Republic of Korea (South Korea) in which at least 2.5 million persons lost their lives. The war reached international proportions in June 1950 when North Korea, supplied and advised by the Soviet Union, invaded the South.

North Korean invasion of South Korea repelled; US-led United Nations invasion of North Korea repelled; Chinese and North Korean invasion of South Korea repelled; Korean Armistice Agreement signed in 1953; Korean conflict ongoing.

Relevant topics

- Vietnam War

- Israeli Palestinian Conflict

- The Spanish American War

- Syrian Civil War

- Atomic Bomb

- Nuclear Weapon

- Treaty of Versailles

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Please enter at least 3 characters

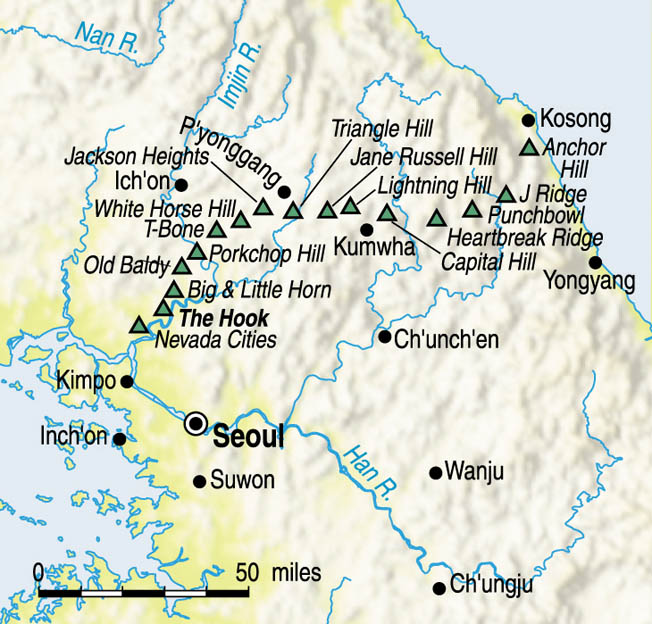

Fighting for the Hook

United Nations forces fought a series of bloody battles with Chinese and Korean Communists for a piece of strategic real estate known as “the Hook.”

This article appears in: February 2007

By Al Hemingway

Peering intently through a telescope, General Lemuel C. Shepherd, the commandant of the Marine Corps, scanned the shell-pocked Korean terrain in front of his position. Shepherd had made a special visit to the Korean front lines to obtain a firsthand view of the Main of Line of Resistance (MLR) his Marines were defending. In the early spring of 1952, under orders from the U.S. Eighth Army in Korea, the entire 25,000-man 1st Marine Division had moved from the east-central sector of the country to the western part of I Corps to man positions along the extreme left flank of an area called the Jamestown Line. In early March the Marines, joined by the attached 1st Korean Marine Corps, completed the move. Maj. Gen. John T. Selden, 1st Marine Division commander, now had 32 miles of harsh country to defend.

Shepherd, for his part, was concerned about the leathernecks’ difficult assignment. In front of their positions was a small speck of land protruding beyond the MLR like a huge thumb. This seemingly insignificant feature, called the Hook by those who had to defend it, dominated the approach to the vital Samichon Valley. The landscape surrounding the Hook was a defender’s nightmare—steep, rugged hills inundated the countryside. If the Chinese managed to break through the Marines’ lines, they could march unhindered all the way to Seoul, the capital of South Korea. As poor a military position as the Hook was, the Marines had no alternative but to occupy it. In enemy hands, the consequences would be catastrophic. Chinese occupation of the Hook would afford a corridor for the enemy to outflank the right flank and reach the Imjin River. This in turn would not only cut off the Marines from the adjacent 1st Commonwealth Division, but also probably render the entire United Nations position beyond the Imjin untenable.

Throughout the spring and summer of 1952, Marines and other Allied units battled the Communists for the various hills and other important terrain features. These bitter, sharp clashes were dubbed “the outpost battles.” In early October, the 7th Marines occupied the Jamestown Line near the Hook. To keep a watchful eye on their adversaries, the Marines established two small combat outposts, Seattle and Warsaw. On October 2, the Chinese struck at Seattle and seized it. Concerned about the Hook, the defenders decided to create another position dubbed Ronson (so named after a Marine had misplaced his Ronson lighter there after a night patrol) about 275 yards west of the Hook. Warsaw was 600 yards northeast of the salient.

Outmanned and Outgunned

The leathernecks’ main problem was manpower. The Marines, plus attached units, had 5,000 troops to defend the Hook. To alleviate the shortage, “clutch platoons” were organized, using Marine cooks, clerks, and motor transport personnel to perform Minuteman-type assignments. They could quickly be formed into reserve rifle platoons in extreme emergency conditions. The leathernecks were not only outmanned, but they were outgunned. To their front were the 356th and 357th Regiments, 119th Division, and 40th Chinese Communist Forces (CCF). Numbering about 7,000 men, the Chinese also possessed 10 battalions of artillery—something the Marines notably lacked—approximately 120 guns in all. In addition, the Marines also suffered from a severe shortage of 105mm and 155mm howitzer shells.

Enemy activity increased dramatically in the last week of October; thousands of artillery rounds were fired on Marine emplacements. Most of the enemy fire was concentrated on the Hook, Warsaw, and Ronson. Marine and Army artillery units responded, trying to silence the enemy guns. Air strikes and tanks guided by forward observers attempted to halt the incessant bombardment. Everyone was braced for the inevitable assault.

On the cold night of October 26, a company from the 3rd Battalion, 357th Regiment attacked Ronson’s small group, raining down mortar and artillery rounds. Trying in vain to hold on, the riflemen responded with automatic weapons fire. It was no use—every American defender was killed. While Ronson was being overrun, a large enemy force from the 9th Company, 357th Regiment descended on Warsaw, which was defended by a reinforced platoon from Company A, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines. Lieutenant John Babson quickly radioed for “box me in” fire (artillery fire that formed a protective shield around the outpost). Despite the heavy shelling, the Chinese penetrated the perimeter. The fighting was hand-to-hand. Just past 7 pm, a clutch platoon was readied to reinforce Warsaw when a radio transmission was received: “We are being overrun.” The outpost was assumed lost. However, just before 8 pm another message requested variable-time fuses to be detonated over the imperiled position. This was the last word heard from the defenders of Warsaw. Only three Marines survived the Communist attack.

As the two outposts were being decimated, a massive bombardment saturated the Hook itself. “Some 34,000 rounds of CCF artillery were used to soften the position before seizure,” Lt. Col. Norman Hicks wrote, “and when the enemy assault came, there were few able to resist.” Captain Paul Byrum’s Company C, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines guarded the important hill. He decided to reconnoiter the ridgeline after receiving a call from Ronson that they were being overrun. He and a sergeant were forced to split up because of the Communist mortar barrage. The sergeant was later killed, and Byrum was buried four times with dirt from near misses.

The Chinese Advance

At exactly 7 pm, the Chinese converged on the Hook in a classic three-pronged maneuver. In less than an hour the enemy had reached the main trench line of Charlie Company. “They were coming over the ridge, gangs of them yelling and blowing horns,” said Pfc. James Yarborough. “They had a horn that sounded like a milk cow. We couldn’t get our guns to work, and we only had two hand grenades. I threw one and my buddy had the pin pulled and was ready to throw the other when he got hit. I threw it.”

Yarborough and his friend managed to emerge from the bunker and lay motionless near the concertina wire on the perimeter. “I lay there and watched the bunker about two and a half hours,” he recalled. “My buddy was still close to it. Finally they came out and it looked as if they were going to shoot him. I still had my carbine and I fired to scatter them. Somehow I got through the wire. My buddy, he got away too.”

Chinese infantrymen breached the wire and infiltrated the trenches. A forward observation team from Battery F, 2nd Battalion, 11th Marines directed accurate fire on the enemy attackers. When they lost communications, 2nd Lt. Sherrod Skinner, Jr., directed his men to leave the bunker and continue to fight. Trapped by the overwhelming enemy numbers, he organized a makeshift defensive position and poured fire into the advancing Communists. During the intense combat, Skinner was struck twice while attempting to replenish the machine-gun squads with ammunition and grenades.

Despite their heroic stand, the Marines were outnumbered by the Chinese. Skinner ordered everyone back to their bunkers. Corporal Franklin Roy and Pfc. Vance Worster killed a dozen enemy soldiers before depleting their ammunition. Skinner felt their only hope was to play dead. As the men lay motionless, the enemy searched them. As they were departing, they tossed chicoms (Chinese hand grenades) into the bunker opening. One of the projectiles peppered Worster’s legs with shrapnel. Skinner rolled over on another one, taking the full brunt of the explosion, which killed him instantly.

Although wounded several times, Roy crawled from the sandbagged bunker and discovered a box of hand grenades. He began lobbing them at the enemy until he exhausted his supply. He finally made his way to friendly lines and informed them of what had happened. Unknown to Roy, Worster had already succumbed to his wounds. Skinner was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor, and Roy and Worster received Navy Crosses for their bravery.

The determined attack on the Hook soon forced Charlie Company from its positions. By dawn, the Communists had gained a toehold on the Hook. Marine historian Lt. Col. Robert Heinl, Jr., present during the battle, later commented, “Soon it was apparent that a serious situation confronted the 7th Marines. This was clearly reflected in the faces and demeanor of the regimental commander and executive officer. Enemy fire was unceasing, and his attack continued.” What remained of Charlie Company had climbed a crest overlooking the Hook and began firing down on the occupants. A platoon from Able Company, originally slated to go to Warsaw, joined them there, keeping the Communists in check and preventing their advance.

Retaking the Hook

More reinforcements were needed, however, if the enemy was to be driven from the Hook. Captain Fred McLaughlin’s Able Company, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines was tapped to link up with Charlie Company and retake the all-important position. McLaughlin had just minutes to devise a plan of attack. He told Lieutenant Stanley Rauh to take a platoon, dig in on the left flank, and deliver as much firepower as possible to create a diversion. Meanwhile, he would take the remaining force of approximately 150 men around the right flank.

Just before daylight, Rauh’s men moved out. As the Marines made their way toward the Hook, the Communist shelling became heavier. When their radio was destroyed by enemy fire, Rauh grabbed a tank’s infantry phone in the rear of the tracked vehicle. Suddenly a white phosphorous round impacted close to them, and Rauh and a sergeant were wounded. The intense heat from the shell fused shut the bolt on Rauh’s carbine and scorched his hands. Because of the lack of water, his men urinated on his hands to stop the burning.

Reaching the command post, Rauh found Byrum still alive. He set out to rescue several isolated pockets of trapped Marines who had been fighting all night. Pfc. Enrique Romero-Nieves picked up an armful of hand grenades and singlehandedly assaulted an enemy bunker. When a bullet shattered his arm, he continued his advance using his belt buckle to pull the pins from the grenades as he moved forward. He survived to be presented a Navy Cross.

Marine and Army rounds began impacting on Warsaw to prevent the enemy from using the position as a forward observation point. Heavy fighting continued at the Hook as Marine tanks positioned themselves on any flat surface they could find and pounded the Chinese now holding fortifications that had been held by the leathernecks a few hours before. Fighter aircraft strafed and napalmed enemy troops attempting to reinforce the Hook from the former Marine outpost on Warsaw. In spite of the superb support, the battle was far from over. The enemy displayed no signs of retreating from the Hook. Rauh recalled: “Communications on the hook were terrible due to the incoming, the terrain and the general confusion of battle. At one point I was talking to the battalion by radio not three feet away from and facing my radioman when a grenade landed on his chest, killing him—I didn’t get touched—only severely jarred. A few moments later a mortar fragment tore the flesh off above my knee.”

The situation at the Hook was desperate. Colonel Thomas C. Moore, Jr., 7th Marines commander, had no choice but to release his last reserve company. Realizing that Able Company and the remnants of Charlie were too weak to push the enemy off the Hook, Moore decided to send in Company H, 3rd Battalion. The enemy, now consolidating forces and moving on the adjacent Hill 146, had to be stopped.

While the beleaguered Marines were immersed in bitter fighting to regain the Hook, the CCF hurled themselves against the nearby outposts of Carson-Reno-Vegas. Defending these positions were elements of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines. A patrol from Company E had just set up an ambush when two CCF companies, moving to attack Reno, wandered into their fields of fire. Just as the enemy was about to advance, the riflemen opened fire, catching the Communists completely by surprise. A few hours later the Chinese returned in force, assaulting the Marines’ perimeter in waves. As the enemy pressed forward, the leathernecks took shelter in their reinforced bunkers while artillery from the 11th Marines caught the CCF units in the open, forcing them to retreat. Reno had been saved.

In the predawn hours, How Company slowly made its way toward the Hook. At 8 am, Captain Bernard Belant ordered his company forward. Leading the charge was 2nd Lt. George H. O’Brien, Jr., from Fort Worth, Texas. With his platoon following him, he zigzagged down the slope toward the main trench line. A burst from an enemy rifle struck him in the arm, slamming him to the ground. Undaunted, O’Brien leaped to his feet and continued the assault. He tossed hand grenades in enemy bunkers as he urged his men on.

One eyewitness account of O’Brien’s actions that day noted, “Five gooks jumped out of nowhere and went for O’Brien. The guy must have had tremendous reflexes, because he dropped all five. He was also wounded, but did this stop him? Hell, no! He continued to lead his platoon. He must have been a hell of an officer.” For four hours O’Brien’s platoon held off the Chinese. When they could advance no farther, the platoon formed a defensive perimeter and waited for any enemy counterattack. O’Brien remained with his men until they were relieved by a fresh unit. For his actions at the Hook, O’Brien later would have the Medal of Honor draped around his neck by President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

In spite of the valorous attempts to retake the Hook, the enemy still held onto it. On the morning of October 27, Company I, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines was told to move up and attack. With artillery support from the 11th Marines and additional firepower from four Corsairs, the first platoon had made it to the crest and by mid-afternoon the entire company was advancing. A company of CCF troops was pouring rifle and automatic weapons fire at the leathernecks, who literally had to crawl toward their objective. Chinese gunners were also delivering devastating fire on the regimental command post.

By 5 pm, Item Company Marines had fought their way to the trenches but were forced to pull back when the Communists opened an overwhelming broadside of machine-gun and rifle fire. Most of the riflemen sought refuge on the reverse slope to avoid being caught in an enemy barrage. By nightfall, Company B, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines was assaulting the enemy trenches at the Hook on the left of Company I. Baker Company infantrymen found it tough going as they reconnoitered the many shell craters that dotted the battle-scarred landscape to reach their jumping-off point and strike at the enemy.

Just past midnight on the 28th, the Marines charged, blasting the Chinese with small-arms fire. A flurry of chicoms met the attackers head-on. Throughout the night, Marine artillery hammered the CCF units. By dawn the Hook was taken. Captain Fred McLaughlin, in charge of retrieving any dead and wounded after the battle, later remembered, “I went around an abandoned trench line at one point and there was a face looking at me from the side of the hill. It was just like it was painted on the side of the hill. It was a Chinese trooper who had been blown into the side of the hill, just the face. We dug these people out. I don’t know how many. It seems to me that over a period from 0800 in the morning until 1500 in the afternoon, we probably located 40-50. Most of them were Chinese but we did recover quite a number of American boys who had given their lives up there on that awful hill that day.”

After the savage fighting to seize the Hook, General Mark W. Clark, commander of Allied forces in the Far East, penned a letter to Secretary of Defense Robert Lovett admonishing the Department of Defense for the shortage of artillery shells. The following year, Congress conducted a series of hearings to explore the situation. It was too late for the young men who had died at the Hook. The penetration by the Chinese of the MLR and the capture of the Hook for 36 hours was the first time the enemy had held any Marine outpost for a long time. In the end, the Chinese paid dearly for their incursion, losing 494 killed and 370 wounded. Marine losses were significant as well, with 82 killed, 386 wounded, and 27 missing. The Chinese, however, were determined to capture and hold the valuable piece of land at any price. Soon they would return.

Another Chinese Assault

On November 3, Company D of the 1st Black Watch Regiment and the Canadian Princess Patricia Light Infantry relieved the Marines. Lt. Col. David Rose, commanding officer of the 1st Black Watch Regiment, immediately set out to rebuild and reinforce the fortifications on the Hook, Ronson, Warsaw, the Sausage (a ridge near Hill 121), and Hills 121 and 146. Although the Jocks (slang for British soldiers) did not particularly like their new assignment of digging improved trenches, Rose realized the importance of the task. An improved barbed wire system was installed and communication units laid a new complex pattern of wireless sets and field phones, in some cases doubling and even tripling the number to enhance communications in the event of another attack.

Rose’s elaborate plan was only half completed when, on the night of November 18, Chinese soldiers were spotted by sentries at Warsaw. The enemy quickly overran Warsaw and assaulted the Hook. From their positions at Yong Dong, about 2,500 yards away, machine gunners from the Duke of Wellington Regiment supported the Black Watch by firing on fixed lines across the Samichon Valley and over the heads of the Black Watch. In the end, the Dukes expended over 50,000 rounds in 11 hours. Private Neil Deck of the 3rd Battalion, Canadian Princess Pats later recalled, “In total, we were on the Hook three nights that time. On the second and third nights, I dug the trench deeper as it had been destroyed by the shelling. It was cold and the ground was frozen, so I used a pick when I heard a hissing noise coming from the bottom of the trench. I reached down and felt some cloth. Pulling on it, I realized it was a coat with a body inside. It was one of the British. He was bloated and the noise I heard was the air coming out of him after I had punctured him with the pick. I got sick to my stomach again.”

The Chinese withdrew, but a short time later the all-too familiar sound of a bugle pierced the night air as the enemy swarmed back over the Hook with a vengeance. The Jocks of the Black Watch were forced to pull back under the sheer weight of the advancing Chinese. With the support of the Centurion tanks from B Squadron, the Royal Inniskilling Dragoons finally drove off the CCF soldiers, and the Hook was once again in Allied hands.

After a two-month respite, the Black Watch returned to the Hook in January 1953. Companies were deployed to Hills 121 and the Sausage. One company from the Dukes established headquarters on Hill 146. Nothing changed as the Chinese artillery kept up the tempo with steady bombardments. Their guns, secreted in the sides of hills, were pulled out to fire and then rolled back to be hidden away from U.N. spotter planes.

“The Black Watch Do Not Withdraw”

In the spring, the Hook exploded in colors as the fields came alive again with flowers and weeds. There was no time, however, to admire the scenery. On May 7, 1953, an observation plane was shot down as it was attempted to locate Communist artillery pounding Commonwealth positions on the Hook and surrounding hills. The Jocks on Warsaw saw CCF units massing for an apparent assault. After ordering a withdrawal from Warsaw, Rose radioed for artillery support. Corps artillery sent 72 eight-inch shells screaming into the enemy troops. This seemed to take the wind out of the Chinese for the moment.

By 2 am, the Communists were back. This time the British soldiers from Ronson anticipated the enemy’s intentions. The Chinese were cut to pieces as the 20th Field Regiment sent proximity-fused high-explosive rounds and three-inch mortar shells near Ronson. Turkish units assisted the Black Watch with additional support. Fearing that the British unit had been overrun, an English-speaking Turkish officer telephoned the Black Watch CP and talked to Lt. Col. Rose. “How, many casualties have you?” the Turkish officer asked. “A few,” replied Rose. “Have you withdrawn?” the officer asked. “The Black Watch do not withdraw,” snapped Rose.

Rose, however, was close to being overrun; the Chinese had managed to crawl to within a mere 20 yards of his forward trench line. One machine gun nest, manned by Black Watch privates, let loose 7,500 rounds at the enemy hordes. After a fierce counterattack, the Black Watch drove the enemy back. On May 12, the battered Black Watch was relieved by elements of the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment. In addition, two troops from C Squadron, 1st Royal Tanks brought their Centurions up for additional punch in the event of another attack.

As the night progressed, Chinese loudspeakers kept up a constant haranguing, warning the Dukes that they would be ousted from the Hook by an overwhelming CCF force. At 11 pm on May 17, the enemy was heard approaching the Hook. An artillery barrage made them retreat, and in the ensuing action a CCF soldier was captured. He relayed the unpleasant information that the Dukes were outnumbered five-to-one and that another major assault was imminent. For the following 10 days, the Communists and the Dukes were in a constant sparring match. Patrols from both sides were dispatched to learn each other’s intentions. Sometimes they would engage in brief but hot firefights. Artillery duels were a daily occurrence. “Bunker life was particularly unsavory with having to share one’s abode with rats, mice and other vermin and being inundated with various insecticides and smells of petroleum-burning heaters in a confined underground situation,” recalled Lieutenant Alec Weaver of the 2nd Royal Australian Regiment (RAR) of his tour of duty on the Hook.

In the darkness on May 29, approximately 100 Chinese infantrymen attempted a lateral approach from Hill 121, trying to capture Ronson. They were spotted and annihilated as they tried in a vain attempt to charge, and 30 mangled bodies were on the wire the next morning as testimony to the futility of the attack. During this period, more than 37,000 shells were fired from British guns. In addition, an unbelievable 10,000 mortar rounds were discharged, as well as 500,000 rounds of small-arms ammunition. One American howitzer let loose an illumination round every two minutes for seven hours. When the full extent of the devastation on the Hook was revealed, 10,000 Chinese shells had ploughed the terrain into six-foot furrows and leveled it like a well-worn football field. Hundreds of Chinese had been killed and thousands wounded. The Dukes had lost 28 killed and 121 wounded and 16 missing. For their heroic defense of the Hook, the Dukes were presented with a battle honor for their colors that read: “The Hook 1953.” Headquarters Company of the 1st Battalion was even renamed Hook Company.

Nearing Armistice

The war, unfortunately, was not over—peace talks between the two sides were painfully slow. Realizing that a truce was near, the Chinese were determined to seize as much terrain as possible, and the Hook was high on their list. Another series of attacks against the Hods and the surrounding hills was planned. Throughout the month of July, the Chinese stepped up offensive operations near the Hook. Boulder City, a Marine outpost, came under heavy attack as well. On the night of July 24, Chinese forces with orders to fight to the last man moved against Hills 111 and 119. Company H, 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines was tied in with a machine-gun section from the 2nd RAR led by Sergeant Brian C. Cooper.

In an area designated Betty Grable, the enemy began to form. Allied artillery hammered them as they readied themselves for the coming attack. The CCF units descended on Hill 111 and were soon in the trenches fighting hand-to-hand. British artillery sent scores of high-explosive rounds toward Hills 111 and 119. The machine-gun section from the 2nd RAR on the leathernecks’ right flank also provided timely support. “The scream and thud of incoming artillery and mortar fire was constant,” wrote Private Ron Walker of the 2nd RAR, “the only difference being the closeness of the burst. Whilst being showered with lumps of dirt and debris I waited for the one burst that might be destined to silence me forever.”

Fighting also erupted on Hill 121 as action continued for the next several days on almost every hill and outpost. “Medium shells sounding like express trains passed over us with plenty of crest clearance,” wrote Bruce Matthews of the New Zealand 16th Field Regiment. “But right above our heads 16th Field’s 25-pounder shells were just clearing our crest. An occasional shell exploded over us. Toward midnight, the tempo of the artillery eased off. The U.S. Marines still had an intact line.” After the battle was over, a young British officer from one of the artillery units that had supported the Marines visited their regimental headquarters. He read to the amazed leathernecks the long list of the different types of rounds that had been fired in their behalf. When he finished, the Marine staff was astounded at his flawless rendition. He then smiled and said, “But I am authorized to settle for two bottles of your best whiskey.”

On July 27, an armistice was signed, ending the Korean conflict. Search parties combed the area around the Hook for any dead, wounded, or missing. Lieutenant Weaver of the 2nd RAR remembered, “The carnage was awe inspiring and the stench overbearing. It was a great relief to be able to leave our battered trenches and the horrific scene.” Sadly, the heroic actions of those who fought so bravely on the Hook have been swept into the dustbin of history. But for those who were there, it remains as vivid today as it did more than 50 years ago. Survivor Ron Walker summed it up best: “There was a certain reluctance to leave, as if a certain something had been left behind and more time should be spent looking for it.”

Back to the issue this appears in

Join The Conversation

One thought on “ fighting for the hook ”.

Error in fact: British troops are NOT known as “Jocks.” Only Scottish troops, and the Black Watch (now amalgamated) was a Scottish regiment.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share This Article

- via= " class="share-btn twitter">

Related Articles

Military History

Capturing the Rock: Gibraltar 1704

Weighing the Odds of Crusader Success

Australia’s Venerable Albert Jacka

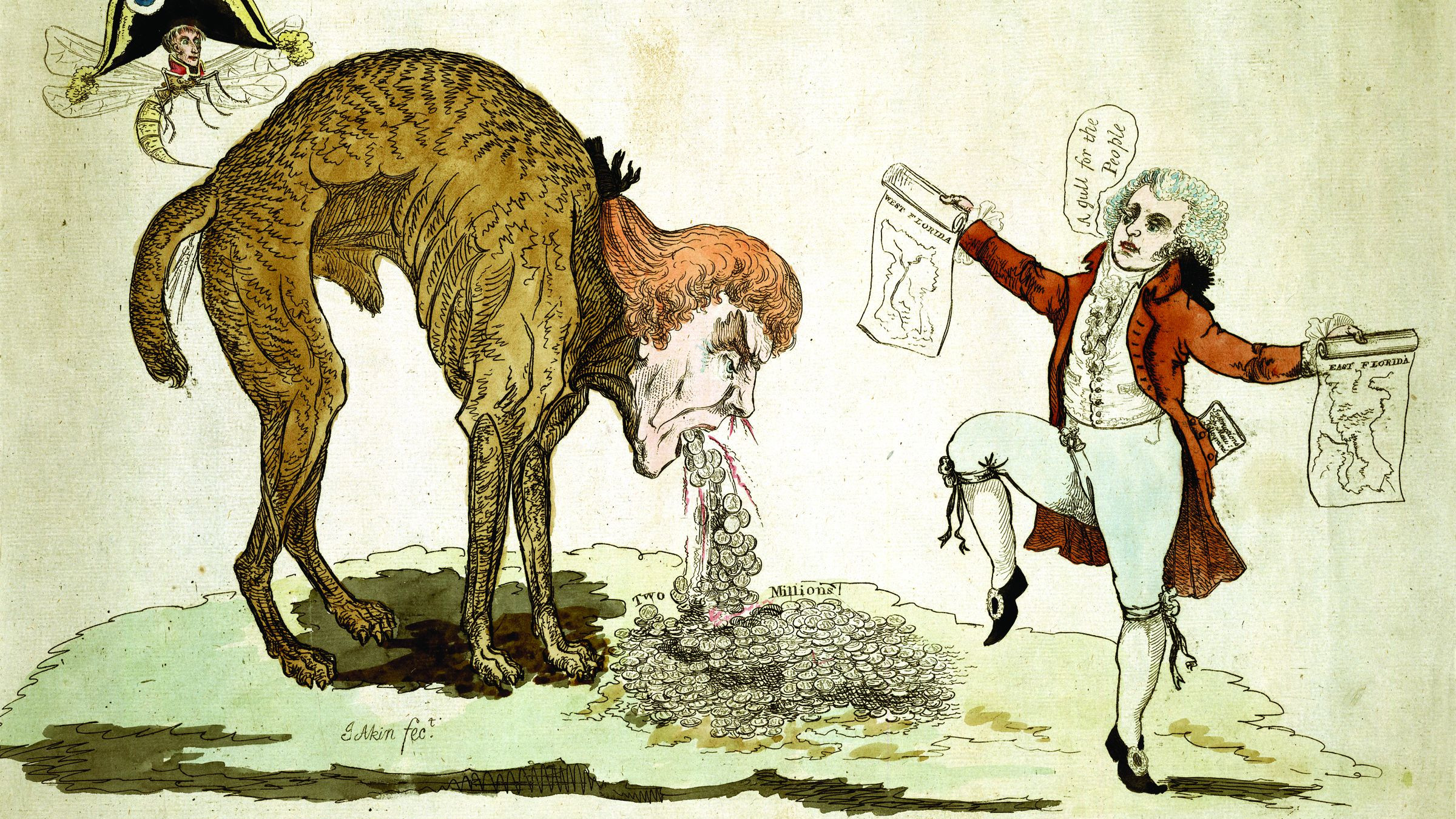

The Florida Annexation

From around the network.

Crossing the Rhine at Remagen

Get the Transports!

The German American Bund: Confessions of a Nazi Spy

Military Games

Paradox Interactive’s East India Company

Memory Bank Multiple Perspectives on the Korean War

Read More »

Multiple Perspectives on the Korean War

But as with all historical interpretation, there are other perspectives to consider. The Soviet Union, for its part, denied Truman’s accusation that it was directly responsible. The Soviets believed that the war was “an internal matter that the Koreans would [settle] among themselves.” They argued that North Korea’s leader Kim Il Sung hatched the invasion plan on his own, then pressed the Soviet Union for aid. The Soviet Union reluctantly agreed to help as Stalin became more and more worried about widening American control in Asia. Stalin therefore approved Kim Il Sung’s plan for invasion, but only after being pressured by Chairman Mao Zedong, leader of the new communist People’s Republic of China.

A historian’s job is to account for as many different perspectives as possible. But sometimes language gets in the way. In order to fully understand the Korean War, historians have had to study documents, conversations, speeches and other communications in multiple languages, including Korean, Chinese, English, Japanese and Russian.

In 1995, the famous Chinese historian Shen Zhihua set out to solve a major problem posed by the war. Many people in the west had argued for decades, as Truman did, that North Korea invaded South Korea at the direction of the Soviet Union. Skeptical of that argument, Zhihua spent 1.4 million yuan ($220,000) of his own money to buy declassified documents from Russian historical archives. Then, he had the papers translated into Chinese so he could read them alongside Chinese government documents.

Zhihua found that Stalin had encouraged Mao Zedong to support North Korea’s invasion plan, vaguely promising Soviet air cover to protect North Korean troops. However, Stalin never believed that the United States and the UN would enter the war, and was reluctant to send the Soviet Air Force because he feared direct confrontation with the United States. When the United States landed at Incheon, Mao recognized that the United States and the UN could quickly overrun North Korea. At that point, he decided to support North Korea with or without Soviet aid, as he was determined to stop the Americans. Stalin eventually did send in the Soviet Air Force, but only after pressure from Mao. Zhihua argued that since China decided to take the lead, the Soviet Union played a weaker role in the war than most western historians believed.

The North Koreans had their own view. They argued that the war began not with their invasion of the south, but with earlier border attacks by South Korean leader Syngman Rhee’s forces, ordered by the United States. The DPRK maintains that the American government planned the war in order to shore up the collapsing Rhee government, to help the American economy and to spread its power throughout Asia and around the world.

Journalist Wilfred Burchett reported on those border incidents prior to the North Korean invasion:

“According to my own, still incomplete, investigation, the war started in fact in August-September 1949 and not in June 1950. Repeated attacks were made along key sections of the 38th parallel throughout the summer of 1949, by Rhee’s forces, aiming at securing jump-off positions for a full-scale invasion of the north. What happened later was that the North Korean forces simply decided that things had gone far enough and that the next assault by Rhee’s forces would be repulsed; that- having exhausted all possibilities of peaceful unification, those forces would be chased back and the south liberated.”

In addition to these perspectives, there are others that still need to be fully studied and understood in the west. Certainly the conflict was fueled and abetted by American, Soviet and European and Chinese designs. But, as historian John Merrill argues, Korean perspectives on the conflict need to be better understood. After all, before the war even began, 100,000 Koreans died in political fighting, guerilla warfare and border skirmishes between 1948 and 1950.

Put simply, Koreans across the peninsula had different ideas about what the future of their country would be like once free of foreign occupation. It is up to us to better understand those perspectives. Only then will we have a fuller understanding of the Korean War, its legacy and its influence on the modern world.

American veterans James Argires, Howard Ballard and Glenn Paige provide their own perspectives on the origins of the conflict.

[ Video: James Argires – Perspectives ]

[ Video: Howard Ballard – Perspectives ]

[ Video: Glenn Paige – Perspectives ]

More History

Prewar Context: Western

North Koreans Stream Toward Pusan

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

The korean war 101: causes, course, and conclusion of the conflict.

North Korea attacked South Korea on June 25, 1950, igniting the Korean War. Cold War assumptions governed the immediate reaction of US leaders, who instantly concluded that Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin had ordered the invasion as the first step in his plan for world conquest. “Communism,” President Harry S. Truman argued later in his memoirs, “was acting in Korea just as [Adolf] Hitler, [Benito] Mussolini, and the Japanese had acted ten, fifteen, and twenty years earlier.” If North Korea’s aggression went “unchallenged, the world was certain to be plunged into another world war.” This 1930s history lesson prevented Truman from recognizing that the origins of this conflict dated to at least the start of World War II, when Korea was a colony of Japan. Liberation in August 1945 led to division and a predictable war because the US and the Soviet Union would not allow the Korean people to decide their own future.

Before 1941, the US had no vital interests in Korea and was largely indifferent to its fate.

Before 1941, the US had no vital interests in Korea and was largely in- different to its fate. But after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his advisors acknowledged at once the importance of this strategic peninsula for peace in Asia, advocating a postwar trusteeship to achieve Korea’s independence. Late in 1943, Roosevelt joined British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kaishek in signing the Cairo Declaration, stating that the Allies “are determined that in due course Korea shall become free and independent.” At the Yalta Conference in early 1945, Stalin endorsed a four-power trusteeship in Korea. When Harry S. Truman became president after Roosevelt’s death in April 1945, however, Soviet expansion in Eastern Europe had begun to alarm US leaders. An atomic attack on Japan, Truman thought, would preempt Soviet entry into the Pacific War and allow unilateral American occupation of Korea. His gamble failed. On August 8, Stalin declared war on Japan and sent the Red Army into Korea. Only Stalin’s acceptance of Truman’s eleventh-hour proposal to divide the peninsula into So- viet and American zones of military occupation at the thirty-eighth parallel saved Korea from unification under Communist rule.

Deterioration of Soviet-American relations in Europe meant that neither side was willing to acquiesce in any agreement in Korea that might strengthen its adversary.

US military occupation of southern Korea began on September 8, 1945. With very little preparation, Washing- ton redeployed the XXIV Corps under the command of Lieutenant General John R. Hodge from Okinawa to Korea. US occupation officials, ignorant of Korea’s history and culture, quickly had trouble maintaining order because al- most all Koreans wanted immediate in- dependence. It did not help that they followed the Japanese model in establishing an authoritarian US military government. Also, American occupation officials relied on wealthy land- lords and businessmen who could speak English for advice. Many of these citizens were former Japanese collaborators and had little interest in ordinary Koreans’ reform demands. Meanwhile, Soviet military forces in northern Korea, after initial acts of rape, looting, and petty crime, implemented policies to win popular support. Working with local people’s committees and indigenous Communists, Soviet officials enacted sweeping political, social, and economic changes. They also expropriated and punished landlords and collaborators, who fled southward and added to rising distress in the US zone. Simultaneously, the Soviets ignored US requests to coordinate occupation policies and allow free traffic across the parallel.

Deterioration of Soviet-American relations in Europe meant that neither side was willing to acquiesce in any agreement in Korea that might strengthen its adversary. This became clear when the US and the Soviet Union tried to implement a revived trusteeship plan after the Moscow Conference in December 1945. Eighteen months of intermittent bilateral negotiations in Korea failed to reach agreement on a representative group of Koreans to form a provisional government, primarily because Moscow refused to consult with anti-Communist politicians opposed to trustee- ship. Meanwhile, political instability and economic deterioration in southern Korea persisted, causing Hodge to urge withdrawal. Postwar US demobilization that brought steady reductions in defense spending fueled pressure for disengagement. In September 1947, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) added weight to the withdrawal argument when they advised that Korea held no strategic significance. With Communist power growing in China, however, the Truman administration was unwilling to abandon southern Korea precipitously, fearing domestic criticism from Republicans and damage to US credibility abroad.

Seeking an answer to its dilemma, the US referred the Korean dispute to the United Nations, which passed a resolution late in 1947 calling for internationally supervised elections for a government to rule a united Korea. Truman and his advisors knew the Soviets would refuse to cooper- ate. Discarding all hope for early reunification, US policy by then had shifted to creating a separate South Korea, able to defend itself. Bowing to US pressure, the United Nations supervised and certified as valid obviously undemocratic elections in the south alone in May 1948, which resulted in formation of the Republic of Korea (ROK) in August. The Soviet Union responded in kind, sponsoring the creation of the Democratic People’s Re- public of Korea (DPRK) in September. There now were two Koreas, with President Syngman Rhee installing a repressive, dictatorial, and anti-Communist regime in the south, while wartime guerrilla leader Kim Il Sung imposed the totalitarian Stalinist model for political, economic, and social development on the north. A UN resolution then called for Soviet-American withdrawal. In December 1948, the Soviet Union, in response to the DPRK’s request, removed its forces from North Korea.

South Korea’s new government immediately faced violent opposition, climaxing in October 1948 with the Yosu-Sunchon Rebellion. Despite plans to leave the south by the end of 1948, Truman delayed military withdrawal until June 29, 1949. By then, he had approved National Security Council (NSC) Paper 8/2, undertaking a commitment to train, equip, and supply an ROK security force capable of maintaining internal order and deterring a DPRK attack. In spring 1949, US military advisors supervised a dramatic improvement in ROK army fighting abilities. They were so successful that militant South Korean officers began to initiate assaults northward across the thirty-eighth parallel that summer. These attacks ignited major border clashes with North Korean forces. A kind of war was already underway on the peninsula when the conventional phase of Korea’s conflict began on June 25, 1950. Fears that Rhee might initiate an offensive to achieve reunification explain why the Truman administration limited ROK military capabilities, withholding tanks, heavy artillery, and warplanes.

Pursuing qualified containment in Korea, Truman asked Congress for three-year funding of economic aid to the ROK in June 1949. To build sup- port for its approval, on January 12, 1950, Secretary of State Dean G. Ache- son’s speech to the National Press Club depicted an optimistic future for South Korea. Six months later, critics charged that his exclusion of the ROK from the US “defensive perimeter” gave the Communists a “green light” to launch an invasion. However, Soviet documents have established that Acheson’s words had almost no impact on Communist invasion planning. Moreover, by June 1950, the US policy of containment in Korea through economic means appeared to be experiencing marked success. The ROK had acted vigorously to control spiraling inflation, and Rhee’s opponents won legislative control in May elections. As important, the ROK army virtually eliminated guerrilla activities, threatening internal order in South Korea, causing the Truman administration to propose a sizeable military aid increase. Now optimistic about the ROK’s prospects for survival, Washington wanted to deter a conventional attack from the north.

Stalin worried about South Korea’s threat to North Korea’s survival. Throughout 1949, he consistently refused to approve Kim Il Sung’s persistent requests to authorize an attack on the ROK. Communist victory in China in fall 1949 pressured Stalin to show his support for a similar Korean outcome. In January 1950, he and Kim discussed plans for an invasion in Moscow, but the Soviet dictator was not ready to give final consent. How- ever, he did authorize a major expansion of the DPRK’s military capabilities. At an April meeting, Kim Il Sung persuaded Stalin that a military victory would be quick and easy because of southern guerilla support and an anticipated popular uprising against Rhee’s regime. Still fearing US military intervention, Stalin informed Kim that he could invade only if Mao Zedong approved. During May, Kim Il Sung went to Beijing to gain the consent of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Significantly, Mao also voiced concern that the Americans would defend the ROK but gave his reluctant approval as well. Kim Il Sung’s patrons had joined in approving his reckless decision for war.

On the morning of June 25, 1950, the Korean People’s Army (KPA) launched its military offensive to conquer South Korea. Rather than immediately committing ground troops, Truman’s first action was to approve referral of the matter to the UN Security Council because he hoped the ROK military could defend itself with primarily indirect US assistance. The UN Security Council’s first resolution called on North Korea to accept a cease- fire and withdraw, but the KPA continued its advance. On June 27, a second resolution requested that member nations provide support for the ROK’s defense. Two days later, Truman, still optimistic that a total commitment was avoidable, agreed in a press conference with a newsman’s description of the conflict as a “police action.” His actions reflected an existing policy that sought to block Communist expansion in Asia without using US military power, thereby avoiding increases in defense spending. But early on June 30, he reluctantly sent US ground troops to Korea after General Douglas MacArthur, US Occupation commander in Japan, advised that failure to do so meant certain Communist destruction of the ROK.

Kim Il Sung’s patrons [Stalin and Mao] had joined in approving his reckless decision for war.

On July 7, 1950, the UN Security Council created the United Nations Command (UNC) and called on Truman to appoint a UNC commander. The president immediately named MacArthur, who was required to submit periodic reports to the United Nations on war developments. The ad- ministration blocked formation of a UN committee that would have direct access to the UNC commander, instead adopting a procedure whereby MacArthur received instructions from and reported to the JCS. Fifteen members joined the US in defending the ROK, but 90 percent of forces were South Korean and American with the US providing weapons, equipment, and logistical support. Despite these American commitments, UNC forces initially suffered a string of defeats. By July 20, the KPA shattered five US battalions as it advanced one hundred miles south of Seoul, the ROK capital. Soon, UNC forces finally stopped the KPA at the Pusan Perimeter, a rectangular area in the southeast corner of the peninsula.

On September 11, 1950, Truman had approved NSC-81, a plan to cross the thirty-eighth parallel and forcibly reunify Korea

Despite the UNC’s desperate situation during July, MacArthur developed plans for a counteroffensive in coordination with an amphibious landing behind enemy lines allowing him to “compose and unite” Korea. State Department officials began to lobby for forcible reunification once the UNC assumed the offensive, arguing that the US should destroy the KPA and hold free elections for a government to rule a united Korea. The JCS had grave doubts about the wisdom of landing at the port of Inchon, twenty miles west of Seoul, because of narrow access, high tides, and sea- walls, but the September 15 operation was a spectacular success. It allowed the US Eighth Army to break out of the Pusan Perimeter and advance north to unite with the X Corps, liberating Seoul two weeks later and sending the KPA scurrying back into North Korea. A month earlier, the administration had abandoned its initial war aim of merely restoring the status quo. On September 11, 1950, Truman had approved NSC-81, a plan to cross the thirty-eighth parallel and forcibly reunify Korea.

Invading the DPRK was an incredible blunder that transformed a three-month war into one lasting three years. US leaders had realized that extension of hostilities risked Soviet or Chinese entry, and therefore, NSC- 81 included the precaution that only Korean units would move into the most northern provinces. On October 2, PRC Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai warned the Indian ambassador that China would intervene in Korea if US forces crossed the parallel, but US officials thought he was bluffing. The UNC offensive began on October 7, after UN passage of a resolution authorizing MacArthur to “ensure conditions of stability throughout Korea.” At a meeting at Wake Island on October 15, MacArthur assured Truman that China would not enter the war, but Mao already had decided to intervene after concluding that Beijing could not tolerate US challenges to its regional credibility. He also wanted to repay the DPRK for sending thou- sands of soldiers to fight in the Chinese civil war. On August 5, Mao instructed his northeastern military district commander to prepare for operations in Korea in the first ten days of September. China’s dictator then muted those associates opposing intervention.

On October 19, units of the Chinese People’s Volunteers (CPV) under the command of General Peng Dehuai crossed the Yalu River. Five days later, MacArthur ordered an offensive to China’s border with US forces in the vanguard. When the JCS questioned this violation of NSC-81, MacArthur replied that he had discussed this action with Truman on Wake Island. Having been wrong in doubting Inchon, the JCS remained silent this time. Nor did MacArthur’s superiors object when he chose to retain a divided command. Even after the first clash between UNC and CPV troops on October 26, the general remained supremely confident. One week later, the Chinese sharply attacked advancing UNC and ROK forces. In response, MacArthur ordered air strikes on Yalu bridges without seeking Washing- ton’s approval. Upon learning this, the JCS prohibited the assaults, pending Truman’s approval. MacArthur then asked that US pilots receive permission for “hot pursuit” of enemy aircraft fleeing into Manchuria. He was infuriated upon learning that the British were advancing a UN proposal to halt the UNC offensive well short of the Yalu to avert war with China, viewing the measure as appeasement.

On November 24, MacArthur launched his “Home-by-Christmas Offensive.” The next day, the CPV counterattacked en masse, sending UNC forces into a chaotic retreat southward and causing the Truman administration immediately to consider pursuing a Korean cease-fire. In several public pronouncements, MacArthur blamed setbacks not on himself but on unwise command limitations. In response, Truman approved a directive to US officials that State Department approval was required for any comments about the war. Later that month, MacArthur submitted a four- step “Plan for Victory” to defeat the Communists—a naval blockade of China’s coast, authorization to bombard military installations in Manchuria, deployment of Chiang Kai-shek Nationalist forces in Korea, and launching of an attack on mainland China from Taiwan. The JCS, despite later denials, considered implementing these actions before receiving favorable battlefield reports.

Early in 1951, Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway, new commander of the US Eighth Army, halted the Communist southern advance. Soon, UNC counterattacks restored battle lines north of the thirty-eighth parallel. In March, MacArthur, frustrated by Washington’s refusal to escalate the war, issued a demand for immediate surrender to the Communists that sabotaged a planned cease-fire initiative. Truman reprimanded but did not recall the general. On April 5, House Republican Minority Leader Joseph W. Martin Jr. read MacArthur’s letter in Congress, once again criticizing the administration’s efforts to limit the war. Truman later argued that this was the “last straw.” On April 11, with the unanimous support of top advisors, the president fired MacArthur, justifying his action as a defense of the constitutional principle of civilian control over the military, but another consideration may have exerted even greater influence on Truman. The JCS had been monitoring a Communist military buildup in East Asia and thought a trusted UNC commander should have standing authority to retaliate against Soviet or Chinese escalation, including the use of nuclear weapons that they had deployed to forward Pacific bases. Truman and his advisors, as well as US allies, distrusted MacArthur, fearing that he might provoke an incident to widen the war.