What creativity really is - and why schools need it

Associate Professor of Psychology and Creative Studies, University of British Columbia

Disclosure statement

Liane Gabora's research is supported by a grant (62R06523) from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

University of British Columbia provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation CA.

University of British Columbia provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

Although educators claim to value creativity , they don’t always prioritize it.

Teachers often have biases against creative students , fearing that creativity in the classroom will be disruptive. They devalue creative personality attributes such as risk taking, impulsivity and independence. They inhibit creativity by focusing on the reproduction of knowledge and obedience in class.

Why the disconnect between educators’ official stance toward creativity, and what actually happens in school?

How can teachers nurture creativity in the classroom in an era of rapid technological change, when human innovation is needed more than ever and children are more distracted and hyper-stimulated ?

These are some of the questions we ask in my research lab at the Okanagan campus of the University of British Columbia. We study the creative process , as well as how ideas evolve over time and across societies. I’ve written almost 200 scholarly papers and book chapters on creativity, and lectured on it worldwide. My research involves both computational models and studies with human participants. I also write fiction, compose music for the piano and do freestyle dance.

What is creativity?

Although creativity is often defined in terms of new and useful products, I believe it makes more sense to define it in terms of processes. Specifically, creativity involves cognitive processes that transform one’s understanding of, or relationship to, the world.

There may be adaptive value to the seemingly mixed messages that teachers send about creativity. Creativity is the novelty-generating component of cultural evolution. As in any kind of evolutionary process, novelty must be balanced by preservation.

In biological evolution, the novelty-generating components are genetic mutation and recombination, and the novelty-preserving components include the survival and reproduction of “fit” individuals. In cultural evolution , the novelty-generating component is creativity, and the novelty-preserving components include imitation and other forms of social learning.

It isn’t actually necessary for everyone to be creative for the benefits of creativity to be felt by all. We can reap the rewards of the creative person’s ideas by copying them, buying from them or simply admiring them. Few of us can build a computer or write a symphony, but they are ours to use and enjoy nevertheless.

Inventor or imitator?

There are also drawbacks to creativity . Sure, creative people solve problems, crack jokes, invent stuff; they make the world pretty and interesting and fun. But generating creative ideas is time-consuming. A creative solution to one problem often generates other problems, or has unexpected negative side effects.

Creativity is correlated with rule bending, law breaking, social unrest, aggression, group conflict and dishonesty. Creative people often direct their nurturing energy towards ideas rather than relationships, and may be viewed as aloof, arrogant, competitive, hostile, independent or unfriendly.

Also, if I’m wrapped up in my own creative reverie, I may fail to notice that someone else has already solved the problem I’m working on. In an agent-based computational model of cultural evolution , in which artificial neural network-based agents invent and imitate ideas, the society’s ideas evolve most quickly when there is a good mix of creative “inventors” and conforming “imitators.” Too many creative agents and the collective suffers. They are like holes in the fabric of society, fixated on their own (potentially inferior) ideas, rather than propagating proven effective ideas.

Of course, a computational model of this sort is highly artificial. The results of such simulations must be taken with a grain of salt. However, they suggest an adaptive value to the mixed signals teachers send about creativity. A society thrives when some individuals create and others preserve their best ideas.

This also makes sense given how creative people encode and process information. Creative people tend to encode episodes of experience in much more detail than is actually needed. This has drawbacks: Each episode takes up more memory space and has a richer network of associations. Some of these associations will be spurious. On the bright side, some may lead to new ideas that are useful or aesthetically pleasing.

So, there’s a trade-off to peppering the world with creative minds. They may fail to see the forest for the trees but they may produce the next Mona Lisa.

Innovation might keep us afloat

So will society naturally self-organize into creators and conformers? Should we avoid trying to enhance creativity in the classroom?

The answer is: No! The pace of cultural change is accelerating more quickly than ever before. In some biological systems, when the environment is changing quickly, the mutation rate goes up. Similarly, in times of change we need to bump up creativity levels — to generate the innovative ideas that will keep us afloat.

This is particularly important now. In our high-stimulation environment, children spend so much time processing new stimuli that there is less time to “go deep” with the stimuli they’ve already encountered. There is less time for thinking about ideas and situations from different perspectives, such that their ideas become more interconnected and their mental models of understanding become more integrated.

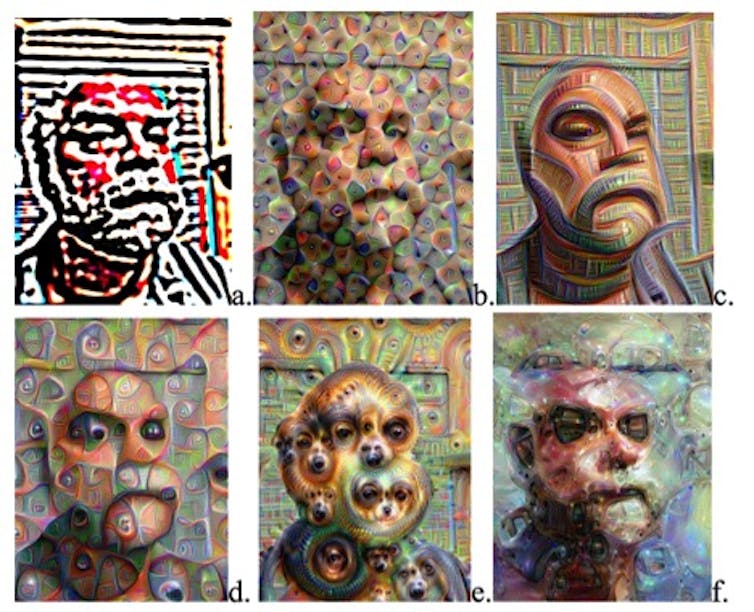

This “going deep” process has been modeled computationally using a program called Deep Dream , a variation on the machine learning technique “Deep Learning” and used to generate images such as the ones in the figure below.

The images show how an input is subjected to different kinds of processing at different levels, in the same way that our minds gain a deeper understanding of something by looking at it from different perspectives. It is this kind of deep processing and the resulting integrated webs of understanding that make the crucial connections that lead to important advances and innovations.

Cultivating creativity in the classroom

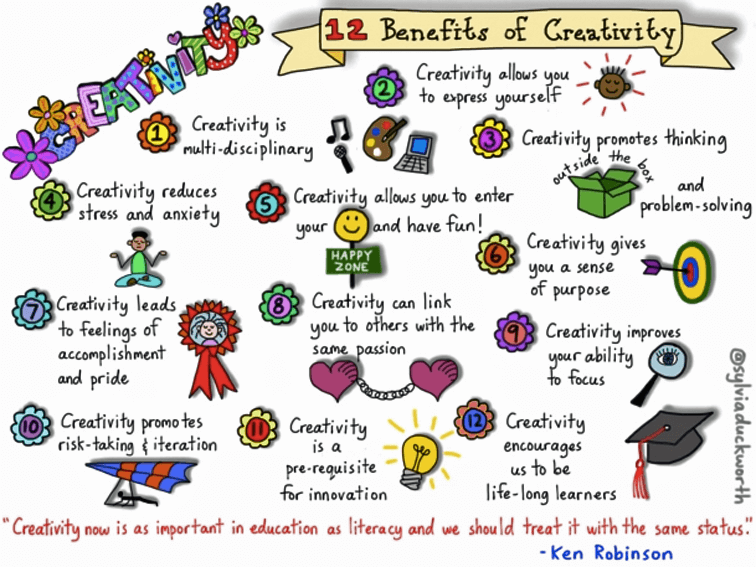

So the obvious next question is: How can creativity be cultivated in the classroom? It turns out there are lots of ways ! Here are three key ways in which teachers can begin:

Focus less on the reproduction of information and more on critical thinking and problem solving .

Curate activities that transcend traditional disciplinary boundaries, such as by painting murals that depict biological food chains, or acting out plays about historical events, or writing poems about the cosmos. After all, the world doesn’t come carved up into different subject areas. Our culture tells us these disciplinary boundaries are real and our thinking becomes trapped in them.

Pose questions and challenges, and follow up with opportunities for solitude and reflection. This provides time and space to foster the forging of new connections that is so vital to creativity.

- Cultural evolution

- Creative pedagody

- Teaching creativity

- Creative thinking

- Back to School 2017

Casual Facilitator: GERRIC Student Programs - Arts, Design and Architecture

Senior Lecturer, Digital Advertising

Service Delivery Fleet Coordinator

Manager, Centre Policy and Translation

Newsletter and Deputy Social Media Producer

Creative Learning in Education

- Open Access

- First Online: 25 June 2021

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Ronald A. Beghetto 3

37k Accesses

14 Citations

2 Altmetric

Creative learning in schools represents a specific form of learning that involves creative expression in the context of academic learning. Opportunities for students to engage in creative learning can range from smaller scale curricular experiences that benefit their own and others’ learning to larger scale initiatives that can make positive and lasting contributions to the learning and lives of people in and beyond the walls of classrooms and schools. In this way, efforts aimed at supporting creative learning represent an important form of positive education. The purpose of this chapter is to introduce and discuss the co-constitutive factors involved in creative learning. The chapter opens by clarifying the nature of creative learning and then discusses interrelated roles played by students, teachers, academic subject matter, uncertainty, and context in creative learning. The chapter closes by outlining future directions for research on creative learning and positive education.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Creative Ecologies and Education Futures

Teaching Creatively and Teaching for Creativity

Supporting creative teaching and learning in the classroom: myths, models, and measures.

Although schools and classrooms have sometimes been characterized as contexts that suppress or even kill student creativity (Robinson, 2006 ), educational settings hold much promise for supporting students’ creative learning. Prior research has, for instance, indicated that there is on an average positive relationship ( r = .22) between measures of creativity and academic achievement (Gajda, Karwowski, & Beghetto, 2016 ). This association tends to grow when measures are more fine-tuned to assess creativity and academic learning in specific subject areas (Karwowski et al., 2020 ). These findings suggest that under the right conditions, creativity and learning can be complementary.

Indeed, creativity researchers have long asserted that creativity and learning are tightly coupled phenomena (Guilford, 1950 , 1967 ; Sawyer, 2012 ). Moreover, recent theoretical and empirical work has helped to clarify the construct and process of creative learning (Beghetto, 2020 ; Beghetto & Schuh, 2020 ; Gajda, Beghetto, & Karwowski, 2017 ). Creative learning in schools represents a specific form of learning that involves creative expression in the context of academic learning. More specifically, creative learning involves a “combination of intrapsychological and interpsychological processes that result in new and personally meaningful understandings for oneself and others” (Beghetto, p. 9).

Within the context of schools and classrooms, the process of creative learning can range from smaller scale contributions to one’s own and others’ learning (e.g., a student sharing a unique way of thinking about a math problem) to larger scale and lasting contributions that benefit the learning and lives of people in and beyond the walls of the classroom (e.g., a group of students develop and implement a creative solution for addressing social isolation in the lunchroom). In this way, efforts aimed at supporting creative learning represents a generative form of positive education because it serves as a vehicle for students to contribute to their own and others learning, life, and wellbeing (White & Kern, 2018 ). The question then is not whether creative learning can occur in schools, but rather what are the key factors that seem to support creative learning in schools and classrooms? The purpose of this chapter is to address this question.

What’s Creative About Creative Learning?

Prior to exploring how creative learning can be supported in schools and classrooms, it is important to first address the question of what is creative about creative learning? Creative learning pertains to the development of new and meaningful contributions to one’s own and others’ learning and lives. This conception of creative learning adheres to standard definitions of creativity (Plucker, Beghetto, & Dow, 2004 ; Runco & Jaeger, 2012 ), which includes two basic criteria: it must be original (new, different, or unique) as defined within a particular context or situation, and it must be useful (meaningful, effectively meets task constraints, or adequately solves the problem at hand). In this way, creativity represents a form of constrained originality. This is particularly good news for educators, as supporting creative learning is not about removing all constraints, but rather it is about supporting students in coming up with new and different ways of meeting academic criteria and learning goals (Beghetto, 2019a , 2019b ).

For example, consider a student taking a biology exam. One question on the exam asks students to draw a plant cell and label its most important parts. If the student responds by drawing a picture of a flower behind the bars of a jail cell and labels the iron bars, lack of windows, and incarcerated plant, Footnote 1 then it could be said that the student has offered an original or even humorous response, but not a creative one. In order for a response to be considered creative, it needs to be both original and meaningfully meet the task constraints. If the goal was to provide a funny response to the prompt, then perhaps it could be considered a creative response. But in this case, the task requires students to meet the task constraints by providing a scientifically accurate depiction of a plant cell. Learning tasks such as this offer little room for creative expression, because the goal is often to determine whether students can accurately reproduce what has been taught.

Conversely, consider a biology teacher who invites students to identify their own scientific question or problem, which is unique and interesting to them. The teacher then asks them to design an inquiry-based project aimed at addressing the question or problem. Next, the teacher invites students to share their questions and project designs with each other. Although some of the questions students identify may have existing answers in the scientific literature, this type of task provides the openings necessary for creative learning to occur in the classroom. This is because students have an opportunity to identify their own questions to address, develop their own understanding of new and different ways of addressing those questions, and share and receive feedback on their unique ideas and insights. Providing students with semi-structured learning experiences that requires them to meet learning goals in new and different ways helps to ensure that students are developing personally and academically meaningful understandings and also provides them with an opportunity to potentially contribute to the understanding of their peers and teachers (see Ball, 1993 ; Beghetto, 2018b ; Gajda et al., 2017 ; Niu & Zhou, 2017 for additional examples).

Creative learning can also extend beyond the walls of the classroom. When students have the opportunity and support to identify their own problems to solve and their own ways of solving them, they can make positive and lasting contributions in their schools, communities, and beyond. Legacy projects represent an example of such efforts. Legacy projects refer to creative learning endeavours that provide students with opportunities to engage with uncetainty and attempt to develop sustainable solutions to complex and ill-defined problems (Beghetto, 2017c , 2018b ). Such projects involve a blend between learning and creative expression with the aim of making a creative contribution. A group of fourth graders who learned about an endangered freshwater shrimp and then worked to restore the habitat by launching a project that spanned across multiple years and multiple networks of teachers, students, and external partners is an example of a legacy project (see Stone & Barlow, 2010 ).

As these examples illustrate, supporting creative learning is not simply about encouraging original student expression, but rather involves providing openings for students to meet academic learning constraints in new and different ways, which can benefit their own, their peers’, and even their teachers’ learning. Creative learning can also extend beyond the classroom and enable students to make a lasting and positive contribution to schools, communities, and beyond. In this way, the process of creative learning includes both intra-psychological (individual) and inter-psychological (social) aspects (Beghetto, 2016).

At the individual level, creative learning occurs when students encounter and engage with novel learning stimuli (e.g., a new concept, a new skill, a new idea, an ill-defined problem) and attempt to make sense of it in light of their own prior understanding (Beghetto & Schuh, 2020 ). Creative learning at the individual level involves a creative combinatorial process (Rothenberg, 2015 ), whereby new and personally meaningful understanding results from blending what is previously known with newly encountered learning stimuli. Creativity researchers have described this form of creativity as personal (Runco, 1996), subjective (Stein, 1953 ), or mini - c creativity Footnote 2 (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2007 ). This view of knowledge development also aligns with how some constructivist and cognitive learning theorists have conceptualized the process of learning (e.g., Alexander, Schallert, & Reynolds, 2009 ; Piaget, 1973 ; Schuh, 2017 ; Von Glasersfeld, 2013 ).

If students are able to develop a new and personally meaningful understanding, then it can be said that they have engaged in creative learning at the individual level. Of course, not all encounters with learning stimuli will result in creative learning. If learning stimuli are too discrepant or difficult, then students likely will not be able to make sense of the stimuli. Also, if students are able to accurately reproduce concepts or solve challenging tasks or problems using memorized algorithms (Beghetto & Plucker, 2006 ) without developing personally meaningful understanding of those concepts or algorithms, then they can be said to have successfully memorized concepts and techniques, but not to have engaged in creative learning. Similarly, if a student has already developed an understanding of some concept or idea and encounters it again, then they will be reinforcing their understanding, rather than developing a new or understanding (Von Glasersfeld, 2013 ). Consequently, in order for creative learning to occur at the individual level, students need to encounter optimally novel learning experiences and stimuli, such that they can make sense of those stimuli in light of their own prior learning trajectories (Beghetto & Schuh, in press; Schuh, 2017 ).

Creative learning can also extend beyond individual knowledge development. At the inter-psychological (or social) level, students have an opportunity to share and refine their conceptions with teachers and peers, making a creative contribution to the learning and lives of others (Beghetto, 2016). For instance, as apparent in the legacy projects, it is possible for students to make creative contributions beyond the walls of the classroom, which occasionally can be recognized by experts as a significant contribution. Student inventors, authors, content creators, and members of community-based problem solving teams are further examples of the inter-psychological level of creative contribution.

In sum, creative learning is a form of creative expression, which is constrained by an academic focus. It is also a special case of academic learning, because it focuses on going beyond reproductive and reinforcement learning and includes the key creative characteristics (Beghetto, 2020 ; Rothenberg, 2015 ; Sawyer, 2012 ) of being both combinatorial (combining existing knowledge with new learning stimuli) and emergent (contributing new and sometimes surprising ideas, insights, perspectives, and understandings to oneself and others).

Locating Creative Learning in Schools and Classrooms

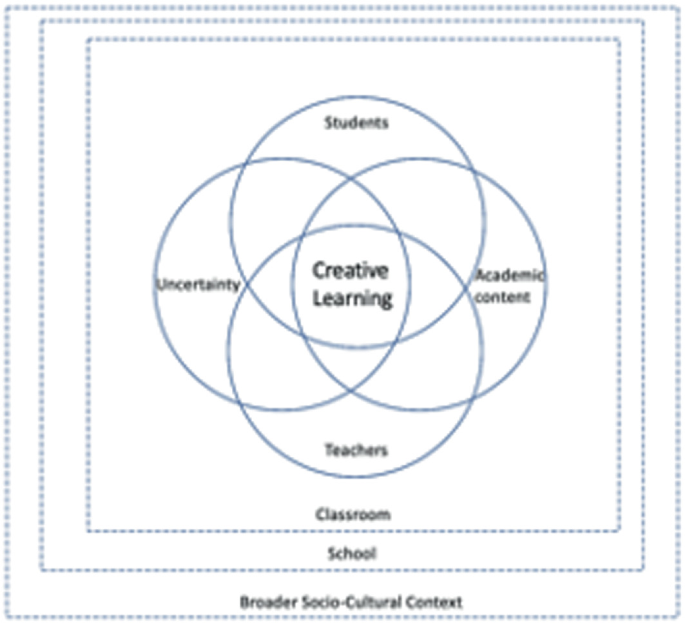

Having now explored the question of what makes creative learning creative, we can now turn our attention to locating the factors and conditions that can help support creative learning in schools and classrooms. As illustrated in Fig. 19.1 , there are at least four interrelated components posited as being necessary for creative learning to occur in schools, classrooms, and beyond: students, teachers, academic subject matter, and uncertainty. Creative learning in schools and classrooms occurs at the intersection of these four factors. Further, the classroom, school, and broader sociocultural contexts play an important role in determining whether and how creative learning will be supported and expressed. Each of these factors will be discussed in the sections that follow.

Factors involved in creative learning in schools, classrooms, and beyond

The Role of Students in Creative Learning

Students, of course, play a central role in creative learning. At the individual level, students’ idiosyncratic learning histories will influence the kinds of creative insights, ideas, and interpretations they have when engaging with new learning stimuli (Beghetto & Schuh, 2020 ; Schuh, 2017 ). Although a case can be made that subjective and personally meaningful creative insights and experiences are sufficient ends in themselves (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2007 ; Runco, 1996 ; Stein, 1953 ), creative learning tends to be situated in well-developed subject areas. Moreover, the goals of most formal educational activities, such as those that occur in schools and classrooms, include making sure that students have developed an accurate or at least a compatible understanding of existing concepts, ideas, and skills (Von Glasersfeld, 2003). Consequently, creative learning in schools—even at the individual level—involves providing students with opportunities to test out and receive feedback on their personal understandings and insights to ensure that what they have learned fits within the broader academic subject area. When this occurs, creative learning at the individual level represents a blend of idiosyncratic and generally agreed upon academic knowledge.

Notably, the idiosyncratic portion of this blend is not merely surplus ideas or insights, but rather has the potential to creatively contribute to the learning and understanding of others. Indeed, the full expression of creative learning extends beyond the individual and also has the opportunity to contribute to the learning and lives of others. At both the individual and social level of creative learning, students’ need to be willing to share, test, and receive feedback on their conceptions, otherwise the full expression of creative learning will be short-circuited. Thus, an important question, at the student level, is what factors might influence students’ willingness to share their ideas with others?

Creativity researchers have identified at least three interrelated student factors that seem to play a role in determining students’ willingness to share their conceptions with others: creative confidence, valuing creativity , and intellectual risk - taking. Creative confidence beliefs refer to a somewhat broad category of creative self-beliefs that pertain to one’s confidence in the ability to think and act creatively (Beghetto & Karwowski, 2017 ). Creative confidence beliefs can range from more situationally and domain-specific beliefs (e.g., I am confident I can creatively solve this particular problem in this particular situation) to more general and global confidence beliefs (e.g., I am confident in my creative ability). Much like other confidence beliefs (Bandura, 2012 ), creative confidence beliefs are likely influenced by a variety of personal (e.g., physiological state), social (e.g., who is present, whether people are being supportive), and situational (e.g., specific nature of the task, including constraints like time and materials) factors. Recent research has indicated that creative confidence beliefs mediate the link between creative potential and creative behaviour (Beghetto, Karwowski, Reiter-Palmon, 2020 ; Karwowski & Beghetto, 2019 ).

In the context of creative learning, this line of work suggests that students need to be confident in their own ideas prior to being willing to share those ideas with others and test out their mini-c ideas. However, valuing creativity and the willingness to take creative risks also appear to play key roles. Valuing creativity refers to whether students view creativity as an important part of their identity and whether they view creative thought and activity as worthwhile endeavours (Karwowski, Lebuda, & Beghetto, 2019 ). Research has indicated that valuing creativity moderates the mediational relationship between creative confidence and creative behaviour (Karwowski & Beghetto, 2019 ).

The same can be said for intellectual risk-taking, which refers to adaptive behaviours that puts a person at risk of making mistakes or failing (Beghetto, 2009 ). Findings from a recent study (Beghetto, Karwowski, Reiter-Palmon, 2020 ) indicate that intellectual risk-taking plays a moderating role between creative confidence and creative behaviour. In this way, even if a student has confidence in their ideas, unless they identify with and view such ideas as worthwhile and are willing to take the risks of sharing those ideas with others, then they are not likely to make a creative contribution to their own and others learning.

Finally, even if students have confidence, value creativity, and are willing to take creative risks, unless they have the opportunities and social supports to do so then they will not be able to realize their creative learning potential. As such, teachers, peers, and others in the social classroom, school, and broader environments are important for bringing such potential to fruition.

The Role of Teachers in Creative Learning

Teachers play a central role in designing and managing the kinds of learning experiences that determine whether creativity will be supported or suppressed in the classroom. Indeed, unless teachers believe that they can support student creativity, have some idea of how to do so, and are willing to try then it is unlikely that students will have systematic opportunities to engage in creative learning (Beghetto, 2017b ; Davies et al., 2013 ; Gralewski & Karawoski, 2018 ; Paek & Sumners, 2019 ). Each of these teacher roles will be discussed in turn.

First, teachers need to believe that they can support student creativity in their classroom. This has less to do with whether or not they value student creativity, as previous research indicates most generally do value creativity, and more about whether teachers have the autonomy, curricular time, and knowledge of how to support student creativity (Mullet, Willerson, Lamb, & Kettler, 2016 ). In many schools and classrooms, the primary aim of education is to support students’ academic learning. If teachers view creativity as being in competition or incompatible with that goal, then they will understandably feel that they should focus their curricular time on meeting academic learning goals, even if they otherwise value and would like to support students’ creative potential (Beghetto, 2013 ). Thus, an important first step in supporting the development of students’ creative potential is for teachers to recognize that supporting creative and academic learning can be compatible goals. When teachers recognize that they can simultaneously support creative and academic learning then they are in a better position to more productively plan for and respond to opportunities for students’ creative expression in their everyday lessons.

Equipped with this recognition, the next step in supporting student creativity is for teachers to develop the knowledge and skills necessary for infusing creativity into their curriculum (Renzulli, 2017 ) so that they can teach for creativity. Teaching for creativity in the K-12 classroom differs from other forms of creativity teaching (e.g., teaching about creativity, teaching with creativity) because it focuses on nurturing student creativity in the context of specific academic subject areas (Beghetto, 2017b ; Jeffrey & Craft, 2004 ). This form of creative teaching thereby requires that teachers have an understanding of pedagogical creativity enhancement knowledge (PCeK), which refers to knowing how to design creative learning experiences that support and cultivate students’ adapted creative attitudes, beliefs, thoughts, and actions in the planning and teaching of subject matter (Beghetto, 2017a ). Teaching for creativity thereby involves designing lessons that provide creative openings and expectations for students to creatively meet learning goals and academic learning criteria. As discussed, this includes requiring students to come up with their own problems to solve, their own ways of solving them, and their own way of demonstrating their understanding of key concepts and skills. Teaching for creativity also includes providing students with honest and supportive feedback to ensure that students are connecting their developing and unique understanding to existing conventions, norms, and ways of knowing in and across various academic domains.

Finally, teachers need to be willing to take the instructional risks necessary to establish and pursue openings in their planned lessons. This is often easier said than done. Indeed, even teachers who otherwise value creativity may worry that establishing openings in their curriculum that require them to pursue unexpected student ideas will result in the lesson drifting too far off-track and into curricular chaos (Kennedy, 2005 ). Indeed, prior research has demonstrated that it is sometimes difficult for teachers to make on-the-fly shifts in their lessons, even when the lesson is not going well (Clark & Yinger, 1977 ). One way that teachers can start opening up their curriculum is to do so in small ways, starting with the way they plan lessons. Lesson unplanning—the process of creating openings in the lesson by replacing predetermined features with to-be-determined aspects (Beghetto, 2017d )—is an example of a small-step approach. A math teacher who asks students to solve a problem in as many ways as they can represent a simple, yet potentially generative form of lesson unplanning. By starting small, teachers can gradually develop their confidence and willingness to establish openings for creative learning in their curriculum while still providing a supportive and structured learning environment. Such small, incremental steps can lead to larger transformations in practice (Amabile & Kramer, 2011 ) and reinforce teachers’ confidence in their ability to support creative learning in their classroom.

The Role of Academic Subject Matter in Creative Learning

Recall that creativity requires a blend of originality and meaningfully meeting criteria or task constraints. If students’ own unique perspectives and interpretations represent the originality component of creativity, then existing academic criteria and domains of knowledge represent the criteria and tasks constraints . Creativity always operates within constraints (Beghetto, 2019a ; Stokes, 2010 ). In the context of creative learning, those constraints typically represent academic learning goals and criteria. Given that most educators already know how to specify learning goals and criteria, they are already half-way to supporting creative learning. The other half requires considering how academic subject matter might be blended with activities that provide students with opportunities to meet those goals and criteria in their own unique and different ways. In most cases, academic learning activities can be thought of as having four components (Beghetto, 2018b ):

The what: What students do in the activity (e.g., the problem to solve, the issue to be addressed, the challenge to be resolved, or the task to be completed).

The how: How students complete the activity (e.g., the procedure used to solve a problem, the approach used to address an issue, the steps followed to resolve a challenge, or the process used to complete a task).

The criteria for success: The criteria used to determine whether students successfully completed the activity (e.g., the goals, guidelines, non-negotiables, or agreed-upon indicators of success).

The outcome: The outcome resulting from engagement with the activity (e.g., the solution to a problem, the products generated from completing a task, the result of resolving an issue or challenge, or any other demonstrated or experienced consequence of engaging in a learning activity).

Educators can use one or more of the above components (i.e., the what, how, criteria, and outcome) to design creative learning activities that blend academic subject matter with opportunities for creative expression. The degrees of freedom for doing so will vary based on the subject area, topics within subject areas, and teachers’ willingness to establish openings in their lessons.

In mathematics, for instance, there typically is one correct answer to solve a problem, whereas other subject areas, such as English Language Arts, offer much more flexibility in the kinds of “answers” or interpretations possible. Yet even with less flexibility in the kinds of originality that can be expressed in a particular subject area, there still remains a multitude of possibilities for creative expression in the kinds of tasks that teachers can offer students. As mentioned earlier, students in math can still demonstrate creative learning in the kinds of problems they design to solve, the various ways they solve them, and even how they demonstrate the outcomes and solutions to those problems.

Finally, teachers can use academic subject matter in at least two different ways to support opportunities for creative learning in their classroom (Beghetto Kaufman, & Baer, 2015 ). The first and most common way is to position subject matter learning as a means to its own end (e.g., we are learning about this technique so that you understand it ). Creativity learning can still operate in this formulation by providing students with opportunities to learn about a topic by meeting goals in unique and different ways, which are still in the service of ultimately understanding the academic subject area. However, the added value in doing so also allows opportunities for students to develop their creative confidence and competence in that particularly subject area.

The second less common, but arguably more powerful, way of positioning academic subject matter in creative learning is as a means to a creative end (e.g., we are learning about this technique so that you can use it to address the complex problem or challenge you and your team identified ). Students who, for instance, developed a project to creatively address the issue of contaminated drinking water in their community would need to learn about water contamination (e.g., how to test for it, how to eradicate contaminates) as part of the process of coming up with a creative solution. In this formulation, both academic subject matter and creative learning opportunities are in the service of attempting to make a creative contribution to the learning and lives of others (Beghetto, 2017c , 2018b ).

The Role of Uncertainty in Creative Learning

Without uncertainty, there is no creative learning. This is because uncertainty establishes the conditions necessary for new thought and action (Beghetto, 2019a ). If students (and teachers) already know what to do and how to do it, then they are rehearsing or reinforcing knowledge and skills. This assertion becomes clearer when we consider it in light of the structure of learning activities. Recall from the previous section, learning activities can be thought of as being comprised of four elements: the what, the how, the criteria for success, and the outcome.

Typically, teachers attempt to remove uncertainty from learning activities by predefining all four aspects of a learning activity. This is understandable as teachers may feel that introducing or allowing for uncertainty to be included in the activity may result curricular chaos, resulting in their own (and their students) frustration and confusion (Kennedy, 2015). Consequently, most teachers learn to plan (or select pre-planned) lessons that provide students with a predetermined problem or task to solve, which has a predetermined process or procedure for solving it, an already established criteria for determining successful performance, and a clearly defined outcome.

Although it is true that students can still learn and develop new and personally meaningful insights when they engage with highly planned lessons, such lessons are “over-planned” with respect to providing curricular space necessary for students to make creative contributions to peers and teachers. Indeed, successful performance on learning tasks in which all the elements are predetermined requires students to do what is expected and how it is expected (Beghetto, 2018a ). Conversely, the full expression of creative learning requires incorporating uncertainty in the form of to-be-determined elements in a lesson. As discussed, this involves providing structured opportunities for students (and teachers) to engage with uncertainty in an otherwise structured and supportive learning environment (Beghetto, 2019a ).

Indeed, teachers still have the professional responsibility to outline the criteria or non-negotiables, monitor student progress, and ensure that they are providing necessary and timely instructional supports. This can be accomplished by allowing students to determine how they meet those criteria. In this way, the role that uncertainty plays in creative learning can be thought of as ranging on a continuum from small openings allowing students to define some element of a learning activity (e.g., the how, what, outcomes) to larger openings where students have much more autonomy in defining elements and even the criteria for success, such as a legacy project whereby they try to make positive and lasting contributions to their schools, communities and beyond.

The Role of Context in Creative Learning

Finally, context also plays a crucial role when it comes to creative learning. Creative learning is always and already situated in sociocultural and historical contexts, which influence and are influenced by students’ unique conceptions of what they are learning and their willingness to share their conceptions with others. As illustrated in Fig. 19.1 , there are at least three permeable contextual settings in which creative learning occurs. The first is the classroom context. Although classrooms and the patterns of interaction that occur within them may appear to be somewhat stable environments, when it comes to supporting creative expression, they can be quite dynamic, variable, and thereby rather unpredictable within and across different settings (Beghetto, 2019b ; Doyle, 2006 ; Gajda et al., 2017 ; Jackson, 1990 ). Indeed, even in classrooms that are characterized as having features and patterns of interaction supportive of creative learning, such patterns may be difficult to sustain over time and even the moment-to-moment supports can be quite variable (Gajda et al., 2017 ).

It is therefore difficult to claim with any level of certainty that a given classroom is “supportive of creativity”; it really depends on what is going on in any given moment. A particular classroom may tend to be more or less supportive across time, however it is the sociodynamic and even material features of a classroom setting that play a key role in determining the kinds and frequency of creative learning openings offered to students (Beghetto, 2017a ).

The same can be said for the school context. The kinds of explicit and tacit supports for creative learning in schools likely play an important role in whether and how teachers and students feel supported in their creative expression (Amabile, 1996 ; Beghetto & Kaufman, 2014 ; Renzulli, 2017 ; Schacter, Thum, & Zifkin, 2006 ). Theoretically speaking, if teachers feel supported by their colleagues and administrators and are actively encouraged to take creative risks, then it seems likely that they would have the confidence and willingness to try. Indeed, this type of social support and modelling can have a cascading influence in and across classrooms and schools (Bandura, 1997 ). Although creativity researchers have theorized and explored the role of context on creative expression (Amabile, 1996 ; Beghetto & Kaufman, 2014 ), research specifically exploring the collective, cascading, and reciprocal effects of school and classroom contexts on creative learning is a promising and needed area of research.

In addition to classroom and school settings, sociocultural theorists in the field of creativity studies (Glăveanu et al., 2020 ) assert that the broader sociocultural influences are not static, unidirectional, or even separate from the people in those contexts, but rather dynamic and co-constitutive processes that influence and are influenced by people in those settings. Along these lines, the kinds of creative learning opportunities and experiences that teachers and students participate in can be thought of as simultaneously being shaped by and helping to shape their particular communities, cultural settings, and broader societies. Consequently, there are times and spaces where creative learning may be more or less valued and supported by the broader sociocultural context. Although some researchers have explored the role of broader societal contexts on creativity (Florida, 2019 ), additional work looking at the more dynamic and reciprocal relationship of creative learning in broader sociocultural and historical contexts is also needed.

Future Directions

Given the dynamic and multifaceted nature of creative learning, researchers interested in examining the various factors involved in creative learning likely would benefit from the development and use of analytic approaches and designs that go beyond single measures or static snapshots to include dynamic (Beghetto & Corazza, 2019 ) and multiple methods (Gajda et al., 2017 ). Such approaches can help researchers better understand the factors at play in supporting the emergence, expression, and sustainability of creative learning in and across various types of school and classroom experiences.

Another seemingly fruitful and important direction for future research on creative learning is to consider it in light of the broader context of positive education. Such efforts can complement existing efforts of researchers in positive education (Kern, Waters, Adler, & White, 2015 ), who have endeavoured to simultaneously examine multiple dimensions involved in the wellbeing of students. Indeed, as discussed, creative learning occurs at the nexus of multiple individual, social, and cultural factors and thereby requires the use of methods and approaches that can examine the interplay among these factors.

In addition, there are a variety of questions that can guide future research on creative learning, including:

How might efforts that focus on understanding and supporting creative learning fit within the broader aims of positive education? How might researchers and educators work together to support such efforts?

What are the most promising intersections among efforts aimed at promoting creative learning and student wellbeing? What are the key complementary areas of overlap and where might there be potential points of tension?

How might researchers across different research traditions in positive education and creativity studies collaborate to develop and explore broader models of wellbeing? What are the best methodological approaches for testing and refining these models? How might such work promote student and teacher wellbeing in and beyond the classroom?

Creative learning represents a potentially important aspect of positive education that can benefit from and contribute to existing research in the field. One way to help realize this potential is for researchers and educators representing a wide array of traditions to work together in an effort to develop an applied understanding of the role creative learning plays in contributing to learn and lives of students in and beyond schools and classrooms.

Creative learning represents a generative and positive educational experience, which not only contributes to the knowledge development of individual students but can also result in creative social contributions to students’ peers, teachers, and beyond. Creative learning thereby represents an important form of positive education that compliments related efforts aimed at building on the strengths that already and always inhere in the interaction among students, teachers, and educational environments. Creative learning also represents an expansion of prototypical learning efforts because it not only focuses on academic learning but also uses it as a vehicle for creative expression and the potential creative contribution to the learning and lives of others. In conclusion, creative learning offers researchers in the fields of creativity studies and positive education an important and complimentary line of inquiry.

This example is based on a popular internet meme of a humorous drawing in response to this question.

Creativity researchers recognize that there are different levels of creative magnitude (Kaufman & Beghetto, 2009 ), which ranges from subjectively experienced creativity ( mini - c ) to externally recognized creativity at the everyday or classroom level ( little - c ), the professional or expert level ( Pro - c ), and even legendary contributions that stand the test of time ( Big - C).

Alexander, P. A., Schallert, D. L., & Reynolds, R. E. (2009). What is learning anyway? A topographical perspective considered. Educational Psychologist, 44, 176–192.

Article Google Scholar

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity . Boulder, CO: Westview.

Google Scholar

Amabile, T. M., & Kramer, S. (2011). The progress principle: Using small wins to ignite joy, engagement, and creativity at work . Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

Ball, D. L. (1993). With an eye on the mathematical horizon: Dilemmas of teaching elementary school mathematics. The Elementary School Journal, 93 (4), 373–397. https://doi.org/10.1086/461730 .

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control . New York: Freeman.

Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38 (1), 9–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311410606 .

Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Correlates of intellectual risk taking in elementary school science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 46, 210–223.

Beghetto, R. A. (2013). Killing ideas softly? The promise and perils of creativity in the classroom . Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Beghetto, R. A. (2016). Creative learning: A fresh look. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 15, 6–23.

Beghetto, R. A. (2017a). Creative openings in the social interactions of teaching. Creativity: Theories-Research-Applications , 3 , 261–273.

Beghetto, R. A. (2017b). Creativity in teaching. In J. C. Kaufman, J. Baer, & V. P. Glăveanu (Eds.), Cambridge Handbook of creativity across different domains (pp. 549–556). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Beghetto, R. A. (2017c). Legacy projects: Helping young people respond productively to the challenges of a changing world. Roeper Review, 39, 1–4.

Beghetto, R. A. (2017d). Lesson unplanning: Toward transforming routine problems into non-routine problems. ZDM - the International Journal on Mathematics Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-017-0885-1 .

Beghetto, R. A. (2018a). Taking beautiful risks in education. Educational Leadership, 76 (4), 18–24.

Beghetto, R. A. (2018b). What if?: Building students’ problem-solving skills through complex challenges . Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Beghetto, R. A. (2019a). Structured uncertainty: How creativity thrives under constraints and uncertainty. In C. A. Mullen (Ed.), Creativity under duress in education? (Vol. 3, pp. 27–40). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90272-2_2 .

Beghetto, R. (2019b). Creativity in Classrooms. In J. Kaufman & R. Sternberg (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity (Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology, pp. 587–606). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316979839.029 .

Beghetto, R. A. (2020). Creative learning and the possible. In V. P. Glăveanu (Ed.), The Palgrave Encyclopedia of the Possible (pp. 1–8). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98390-5_57-1 .

Beghetto, R. A., & Corazza, G. E. (2019). Dynamic perspectives on creativity: New directions for theory, research, and practice . Cham, Switerland: Springer International Publishing.

Book Google Scholar

Beghetto, R. A., & Karwowski, M. (2017). Toward untangling creative self-beliefs. The creative self (pp. 3–22). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Beghetto, R. A., Karwowski, M., & Reiter-Palmon, R. (2020). Intellectual Risk taking: A moderating link between creative confidence and creative behavior? Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts . https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000323 .

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2007). Toward a broader conception of creativity: A case for mini-c creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 1, 73–79.

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2014). Classroom contexts for creativity. High Ability Studies, 25 (1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2014.905247 .

Beghetto, R. A., Kaufman, J. C., & Baer, J. (2015). Teaching for creativity in the common core . Teachers College Press.

Beghetto, R. A., & Plucker, J. A. (2006). The relationship among schooling, learning, and creativity: “All roads lead to creativity” or “you can’t get there from here”? In James C. Kaufman & J. Baer (Eds.), Creativity and reason in cognitive development (pp. 316–332). New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606915.019 .

Beghetto, R. A., & Schuh, K. (2020). Exploring the link between imagination and creativity: A creative learning perspective. In D. D. Preiss, D. Cosmelli, & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Mind wandering and creativity . Academic Press.

Clark, C. M., & Yinger, R. J. (1977). Research on teacher thinking. Curriculum Inquiry, 7, 279–304.

Davies, D., Jindal-Snape, D., Collier, C., Digby, R., Hay, P., & Howe, A. (2013). Creative learning environments in education: A systematic literature review. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 8, 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2012.07.004 .

Doyle, W. (2006). Ecological approaches to classroom management. In C. M. Evertson & C. S. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues (pp. 97–125). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Florida, R. (2019). The rise of the creative class . Basic books.

Gajda, A., Beghetto, R. A., & Karwowski, M. (2017). Exploring creative learning in the classroom: A multi-method approach. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 24, 250–267.

Gajda, A., Karwowski, M., & Beghetto, R. A. (2016). Creativity and school achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109, 269–299.

Glăveanu, V. P. (Ed.). (2016). The Palgrave handbook of creativity and culture research . London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Glăveanu, V. P., Hanchett Hanson, M., Baer, J., Barbot, B., Clapp, E. P., Corazza, G. E., … Sternberg, R. J. (2020). Advancing creativity theory and research: A Socio‐cultural manifesto. The Journal of Creative Behavior , 54 , 741–745. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.395 .

Gralewski, J., & Karawoski, M. (2018). Are teachers’ implicit theories of creativity related to the recognition of their students’ creativity? Journal of Creative Behavior, 52, 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.140 .

Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 14, 469–479.

Guilford, J. P. (1967). Creativity and learning. In D. B. Lindsley & A. A. Lumsdaine (Eds.), Brain function, Vol. IV: Brain function and learning (pp. 307–326). Los Angles: University of California Press.

Jackson, P. W. (1990). Life in classrooms . New York: Teachers College Press.

Jeffrey, B., & Craft, A. (2004). Teaching creatively and teaching for creativity: Distinctions and relationships. Educational Studies, 30, 77–87.

Karwowski, M., & Beghetto, R. A. (2019). Creative behavior as agentic action. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 13, 402–415.

Karwowski, M., Jankowska, D. M., Brzeski, A., Czerwonka, M., Gajda, A., Lebuda, I., & Beghetto, R. A. (2020). Delving into creativity and learning. Creativity Research Journal, 32 (1), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2020.1712165 .

Karwowski, M., Lebuda, I., & Beghetto, R. A. (2019). Creative self-beliefs. In J. C. Kaufman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity (2nd ed., pp. 396–418). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity. Review of General Psychology , 13, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013688 .

Kennedy, M. (2005). Inside teaching: How classroom life undermines reform . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kern, M. L., Waters, L. E., Adler, A., & White, M. A. (2015). A multidimensional approach to measuring well-being in students: Application of the PERMA framework. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10 (3), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.936962 .

Mullet, D. R., Willerson, A., Lamb, K. N., & Kettler, T. (2016). Examining teacher perceptions of creativity: A systematic review of the literature. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 21, 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2016.05.001 .

Niu, W., & Zhou, Z. (2017). Creativity in mathematics teaching: A Chinese perspective (an update. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom (2nd ed., pp. 86–107). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Paek, S. H., & Sumners, S. E. (2019). The indirect effect of teachers’ creative mindsets on teaching creativity. Journal of Creative Behavior, 53, 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.180 .

Piaget, J. (1973). To understand is to invent: The future of education . Location: Publisher.

Plucker, J., Beghetto, R. A., & Dow, G. (2004). Why isn’t creativity more important to educational psychologists? Potential, pitfalls, and future directions in creativity research. Educational Psychologist, 39, 83–96.

Renzulli, J. (2017). Developing creativity across all areas of the curriculum. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom (2nd ed., pp. 23–44). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Robinson, K. (2006). Ken Robinson: Do schools kill creativity? [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.Ted.Com/Talks/Ken_robinson_says_schools_kill_creativity .

Rothenberg, A. (2015). Flight from wonder: An investigation of scientific creativity . New York: Oxford University Press.

Runco, M. A. (1996). Personal creativity: Definition and developmental issues. NewDirections in Child Development, 72 , 3–30.

Runco, M. A., & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The standard definition of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24 (1), 92–96.

Sawyer, R. K. (2012). Explaining creativity: The science of human innovation (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Schacter, J., Thum, Y. M., & Zifkin, D. (2006). How much does creative teaching enhance elementary school students’ achievement? The Journal of Creative Behavior, 40, 47–72.

Schuh, K. L. (2017). Making meaning by making connections . Cham, Switerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-0993-2 .

Sirotnik, K. A. (1983). What you see is what you get: Consistency, persistency, and mediocrity in classrooms. Harvard Educational Review, 53, 16–31.

Stein, M. I. (1953). Creativity and culture. The Journal of Psychology, 36 , 311–322.

Stokes, P. D. (2010). Using constraints to develop creativity in the classroom. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom (pp. 88–112). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Stone, M. K., & Barlow, Z. (2010). Social learning in the STRAW project. In A. E. J. Wals (Ed.), Social learning towards a sustainable world (pp. 405–418). The Netherlands: Wageningen Academic.

Von Glasersfeld, E. (2013). Radical constructivism . New York: Routledge.

White, M., & Kern, M. L. (2018). Positive education: Learning and teaching for wellbeing and academic mastery. International Journal of Wellbeing, 8 (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v8i1.588 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

Ronald A. Beghetto

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ronald A. Beghetto .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Centre for Wellbeing Science , University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Margaret L. Kern

Department of Special Education, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA

Michael L. Wehmeyer

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Beghetto, R.A. (2021). Creative Learning in Education. In: Kern, M.L., Wehmeyer, M.L. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Positive Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64537-3_19

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64537-3_19

Published : 25 June 2021

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-64536-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-64537-3

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Creativity in education.

- Anne Harris Anne Harris RMIT University

- and Leon De Bruin Leon De Bruin RMIT University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.383

- Published online: 26 April 2018

Creativity is an essential aspect of teaching and learning that is influencing worldwide educational policy and teacher practice, and is shaping the possibilities of 21st-century learners. The way creativity is understood, nurtured, and linked with real-world problems for emerging workforces is significantly changing the ways contemporary scholars and educators are now approaching creativity in schools. Creativity discourses commonly attend to creative ability, influence, and assessment along three broad themes: the physical environment, pedagogical practices and learner traits, and the role of partnerships in and beyond the school. This overview of research on creativity education explores recent scholarship examining environments, practices, and organizational structures that both facilitate and impede creativity. Reviewing global trends pertaining to creativity research in this second decade of the 21st century, this article stresses for practicing and preservice teachers, schools, and policy makers the need to educationally innovate within experiential dimensions, priorities, possibilities, and new kinds of partnerships in creativity education.

- creative ecologies

- creative environments

- creative industries

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 19 August 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Character limit 500 /500

Why is Creativity Important in Education?

At its core, creativity is the expression of our most essential human qualities: our curiosity, our inventiveness, and our desire to explore the unknown. As we navigate an increasingly complex and changing world, promoting creativity in education is more important than ever before.

Prisma is the world’s most engaging virtual school that combines a fun, real-world curriculum with powerful mentorship from experienced coaches and a supportive peer community

The Importance of Creativity

We are all creative people, whether you think of yourself as creative or not. It takes creative thinking to paint a picture, but it also takes creative thinking to figure out the right formula to use in a spreadsheet, to invent a twist on a chocolate chip cookie recipe, or to plan a birthday party. But some people are more practiced and comfortable in the creative process than others.

At its core, creativity is the expression of our most essential human qualities: our curiosity, our inventiveness, and our desire to explore the unknown. Using creativity, we are able to push the boundaries of what is possible, imagine new worlds, and find solutions to the most pressing problems facing our society.

In a world where automation looms to take over all but the most innovative tasks—ones that truly require unique thinking—how can we make sure the next generation is capable of creatively solving these problems? We founded Prisma precisely because we were concerned traditional forms of education weren’t up to the challenge of creating future innovators.

In this post, we will explore the importance of creativity in the education system, the role of creativity in students' emotional development, and the ways in which it can be taught .

Creativity in Education

Despite the vital role creativity plays in our lives, it is often undervalued and neglected in our educational system. We are taught to memorize facts and figures, follow rules and procedures, and conform to the expectations of others. This approach may produce technically proficient students, but it fails to cultivate the spirit of creativity at the heart of true innovation.

In a rapidly evolving world with increasing automation, the ability to think creatively and come up with innovative solutions to problems is critical. This is particularly true in education, where fostering creativity can help students develop important critical thinking skills, as well as prepare them for the 21st-century workforce.

Creativity=Critical Thinking

“There’s no doubt that creativity is the most important human resource of all. Without creativity, there would be no progress, and we would forever be repeating the same patterns.” -Edward de Bono

What does creativity have to do with critical thinking ? At its core, creativity is about problem-solving . This is a skill becoming increasingly important right now as the world rapidly changes. To keep up with these changes, young people need to be able to come up with creative ways to solve problems, and be able to adapt to new situations quickly.

At Prisma, learners engage in a workshop called Collaborative Problem-Solving twice per week. These workshops might involve a critical thinking simulation, like when learners had to choose which businesses to invest in, Shark Tank style; or a science simulation where they had to figure out how to power a city using a combination of resources. In real life, much of creative problem solving happens in teams, yet in many traditional schools, kids are asked to solve problems on their own.

To build the form of creativity that leads to innovative thinking, learners need complex, interesting problems to solve. Education needs to figure out ways to design these kinds of authentic problems to prepare learners to succeed.

Creativity & Social Emotional Skills

“The most regretful people on Earth are those who felt the call to creative work, who felt their own creative power restive and uprising, and gave it neither power nor time.” -Mary Oliver

One of the benefits of creativity is the role it can play in the development of emotional intelligence . As mentioned above, creativity is an essential part of what it means to be human. It feels good to make something and be proud of it! When learners are given the opportunity for creative expression, it can help them develop their self-esteem and build confidence .

Prisma learners complete a creative project every 6 weeks based on our interdisciplinary learning themes , and present their final projects during a celebratory “Expo Day.” LaShonda S., a Prisma parent, described how making a creative project for the first time impacted her son this way: “His sense of pride and accomplishment has gone through the roof. He has told all of our family and friends about his podcast.”

Building students’ creativity isn’t just about the warm and fuzzy feelings, though. Going through a creative process is tough, and can build resilience, grit , and tenacity. It’s much easier to follow step-by-step instructions than it is to brainstorm, ideate, and iterate on your own idea. Creative projects can help kids learn to take risks and embrace failure, which is always an important part of the creative process.

In addition, creativity can help students develop important social skills. When learners work on creative projects together, they learn to collaborate and communicate effectively. This is an important skill for the 21st-century workforce , where teamwork and collaboration are essential. Since Prisma is a virtual school, our learners go even further, learning how to collaborate on creative projects virtually with young people all over the world, much like many adults do in their jobs today.

Sign up for more research-backed guides in your inbox

- Prisma is an accredited, project-based, online program for grades 4-12.

- Our personalized curriculum builds love of learning and prepares kids to thrive.

- Our middle school , high school , and parent-coach programs provide 1:1 coaching and supportive peer cohorts .

Role of Creativity in the Education System

The education system has not always prioritized creativity. In fact, many education systems around the world have placed a greater emphasis on rote learning and standardized testing than on creativity and innovation.

Chen Jining, the president of Tsinghua University in China, once described the dichotomy between “A students” And “X students.” “A students” were those who followed all the rules, achieved excellent grades from kindergarten through high school, and aced standardized tests. Jining noticed what these Chinese students often lacked, however, was an aptitude for risk taking, trying new things, and “defining their own problems rather than simply solving the ones in the textbook.” (Mitchell Resnick, Lifelong Kindergarten ). The kind of creative people who could do those things could be thought of as “X students.”

High-achieving students who lack creativity are a major problem for any society who wants to solve problems, invent solutions, and innovate. What kind of learning environment might create a society of “X students” rather than just “A students”?

Creative Thinkers in Education

Fortunately, there are many educators and thinkers working to promote creativity in education. Sir Ken Robinson made a splash when he argued in a highly popular TedTalk and other writing & speeches that traditional education systems kill creativity.

Prisma’s curriculum was inspired by Seymour Papert , a mathematician and computer scientist who was a pioneer in the field of educational technology. Papert believed technology could be used to promote creativity and empower students to learn in new and innovative ways. He also believed creativity was a key component of the learning process, and that students should be given the freedom to explore and experiment to develop their creative thinking skills. His philosophy that learners learn most when engaged in a process of “ hard fun ” inspired the design of Prisma’s engaging curriculum themes & creative projects.

Another influential thinker in the field of creativity in education is Peter Gray , a psychologist and author who has written extensively on the importance of play and creative expression in children's lives. Gray argues play and creativity are essential for children's emotional and cognitive development and that schools should prioritize these activities to promote social skills and academic success.

Assessing Creativity

Unlike standardized tests, which (arguably) provide a clear measure of students' knowledge and understanding, creativity is more difficult to assess. This prompts some educators to dismiss its importance. However, there are ways to measure creativity, such as through creative projects and assessments focusing on problem-solving and critical thinking skills.

Before joining the founding team of Prisma, I researched creative assessment at Harvard. We discovered strategies such as assessing the process as well as the final product, allowing opportunities for peer & family feedback, and incorporating self-assessment and self-reflection helped reliably assess students’ creativity.

4 Ways to Teach Creativity

So how can teachers and homeschool parents foster creativity?

- Design a creative classroom environment , or make your home workspace more creatively inspiring. Of course, at a baseline, a creative learning environment may include materials like art supplies, building blocks, and maker tools, but kids can also be creative with digital tools like Procreate , TinkerCad , Canva , and plain old pen and paper. Remember, creativity is about ideas, not materials!

- Provide opportunities for brainstorming , encouraging students to come up with their own ideas. Instead of deciding in advance what learners will create and what the steps will be, consider coming up with the project together, or letting learners design their own . At Prisma, learners get multiple options each cycle for projects they can complete, and also have the opportunity to propose and design their own projects.

- Foster a creative mindset . This involves encouraging students to take risks and embrace failure, and helping them understand creativity is a process, not a product. At Prisma, this looks like using badges instead of traditional grades , and offering lots of opportunities for kids to reflect on not only what they made, but what they learned along the way. Don’t just give praise for what a learner completed, but their behavior during the process: for example, “I noticed how you changed your idea after you got peer feedback, what a great creative mindset!” instead of “Your drawing is really good!”

- Teach creative thinking skills explicitly . This can involve teaching students how to brainstorm effectively, how to find a creative flow state , and how to give & get feedback on their ideas. At Prisma, we use design thinking frameworks and teach learners the steps.

So what happens when schools decide to emphasize these strategies? Kids can do amazing things! As one Prisma parent describes, “ This year, my 10 year old designed her own ecosystem in TinkerCAD, started her own business with a functioning website, served as "Swedish Ambassador to the UN council" where she debated how to resolve the Syrian refugee crisis, coded her own game to educate others on Audio-Sensory-Processing-Disorder, and wrote her own fairy tale.”

Creativity is a critical component of education in the 21st century. By promoting creativity, you can help students develop important problem-solving and critical thinking skills, as well as foster their emotional and social development. While there are challenges to promoting creativity in the education system, there are also many educators and thinkers who are working to make creativity a priority in education. As we navigate an increasingly complex and changing world, promoting creativity in education is more important than ever before.

More Resources for Creative Education

Our Guide to Design Thinking For Kids

Our Guide to Entrepreneurship For Kids

Our Guide to Curiosity in Education

Our Guide to Interdisciplinary Education

Our Guide to Real-World Education

Join our community of families all over the world doing school differently.

Want to learn more about how Prisma can empower your child to thrive?

More from our blog

Recommendations.

Prisma Newsletter

About The Education Hub

- Course info

- Your courses

- ____________________________

- Using our resources

- Login / Account

What is creativity in education?

- Curriculum integration

- Health, PE & relationships

- Literacy (primary level)

- Practice: early literacy

- Literacy (secondary level)

- Mathematics

Diverse learners

- Gifted and talented

- Neurodiversity

- Speech and language differences

- Trauma-informed practice

- Executive function

- Movement and learning

- Science of learning

- Self-efficacy

- Self-regulation

- Social connection

- Social-emotional learning

- Principles of assessment

- Assessment for learning

- Measuring progress

- Self-assessment

Instruction and pedagogy

- Classroom management

- Culturally responsive pedagogy

- Co-operative learning

- High-expectation teaching

- Philosophical approaches

- Planning and instructional design

- Questioning

Relationships

- Home-school partnerships

- Student wellbeing NEW

- Transitions

Teacher development

- Instructional coaching

- Professional learning communities

- Teacher inquiry

- Teacher wellbeing

- Instructional leadership

- Strategic leadership

Learning environments

- Flexible spaces

- Neurodiversity in Primary Schools

- Neurodiversity in Secondary Schools

Human beings have always been creative. The fact that we have survived on the planet is testament to this. Humans adapted to and then began to modify their environment. We expanded across the planet into a whole range of climates. At some point in time we developed consciousness and then language. We began to question who we are, how we should behave, and how we came into existence in the first place. Part of human questioning was how we became creative.

The myth that creativity is only for a special few has a long, long history. For the Ancient Chinese and the Romans, creativity was a gift from the gods. Fast forward to the mid-nineteenth century and creativity was seen as a gift, but only for the highly talented, romantically indulgent, long-suffering and mentally unstable artist. Fortunately, in the 1920s the field of science began to look at creativity as a series of human processes. Creative problem solving was the initial focus, from idea generation to idea selection and the choice of a final product. The 1950s were a watershed moment for creativity. After the Second World War, the Cold War began and competition for creative solutions to keep a technological advantage was intense. It was at this time that the first calls for STEM in education and its associated creativity were made. Since this time, creativity has been researched across a whole range of human activities, including maths, science, engineering, business and the arts.

The components of creativity