Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

How Money Changes the Way You Think and Feel

The term “affluenza”—a portmanteau of affluence and influenza, defined as a “painful, contagious, socially transmitted condition of overload, debt, anxiety, and waste, resulting from the dogged pursuit of more”—is often dismissed as a silly buzzword created to express our cultural disdain for consumerism. Though often used in jest, the term may contain more truth than many of us would like to think.

Whether affluenza is real or imagined, money really does change everything, as the song goes—and those of high social class do tend to see themselves much differently than others. Wealth (and the pursuit of it) has been linked with immoral behavior—and not just in movies like The Wolf of Wall Street .

Psychologists who study the impact of wealth and inequality on human behavior have found that money can powerfully influence our thoughts and actions in ways that we’re often not aware of, no matter our economic circumstances. Although wealth is certainly subjective, most of the current research measures wealth on scales of income, job status, or socioeconomic circumstances, like educational attainment and intergenerational wealth.

Here are seven things you should know about the psychology of money and wealth.

More money, less empathy?

Several studies have shown that wealth may be at odds with empathy and compassion . Research published in the journal Psychological Science found that people of lower economic status were better at reading others’ facial expressions —an important marker of empathy—than wealthier people.

“A lot of what we see is a baseline orientation for the lower class to be more empathetic and the upper class to be less [so],” study co-author Michael Kraus told Time . “Lower-class environments are much different from upper-class environments. Lower-class individuals have to respond chronically to a number of vulnerabilities and social threats. You really need to depend on others so they will tell you if a social threat or opportunity is coming, and that makes you more perceptive of emotions.”

While a lack of resources fosters greater emotional intelligence, having more resources can cause bad behavior in its own right. UC Berkeley research found that even fake money could make people behave with less regard for others. Researchers observed that when two students played Monopoly, one having been given a great deal more Monopoly money than the other, the wealthier player expressed initial discomfort, but then went on to act aggressively, taking up more space and moving his pieces more loudly, and even taunting the player with less money.

Wealth can cloud moral judgment

It is no surprise in this post-2008 world to learn that wealth may cause a sense of moral entitlement. A UC Berkeley study found that in San Francisco—where the law requires that cars stop at crosswalks for pedestrians to pass—drivers of luxury cars were four times less likely than those in less expensive vehicles to stop and allow pedestrians the right of way. They were also more likely to cut off other drivers.

Another study suggested that merely thinking about money could lead to unethical behavior. Researchers from Harvard and the University of Utah found that study participants were more likely to lie or behave immorally after being exposed to money-related words.

“Even if we are well-intentioned, even if we think we know right from wrong, there may be factors influencing our decisions and behaviors that we’re not aware of,” University of Utah associate management professor Kristin Smith-Crowe, one of the study’s co-authors, told MarketWatch .

Wealth has been linked with addiction

While money itself doesn’t cause addiction or substance abuse, wealth has been linked with a higher susceptibility to addiction problems. A number of studies have found that affluent children are more vulnerable to substance-abuse issues , potentially because of high pressure to achieve and isolation from parents. Studies also found that kids who come from wealthy parents aren’t necessarily exempt from adjustment problems—in fact, research found that on several measures of maladjustment, high school students of high socioeconomic status received higher scores than inner-city students. Researchers found that these children may be more likely to internalize problems, which has been linked with substance abuse.

But it’s not just adolescents: Even in adulthood, the rich outdrink the poor by more than 27 percent.

Money itself can become addictive

The pursuit of wealth itself can also become a compulsive behavior. As psychologist Dr. Tian Dayton explained, a compulsive need to acquire money is often considered part of a class of behaviors known as process addictions, or “behavioral addictions,” which are distinct from substance abuse.

These days, the idea of process addictions is widely accepted. Process addictions are addictions that involve a compulsive and/or an out-of-control relationship with certain behaviors such as gambling, sex, eating, and, yes, even money.…There is a change in brain chemistry with a process addiction that’s similar to the mood-altering effects of alcohol or drugs. With process addictions, engaging in a certain activity—say viewing pornography, compulsive eating, or an obsessive relationship with money—can kickstart the release of brain/body chemicals, like dopamine, that actually produce a “high” that’s similar to the chemical high of a drug. The person who is addicted to some form of behavior has learned, albeit unconsciously, to manipulate his own brain chemistry.

While a process addiction is not a chemical addiction, it does involve compulsive behavior —in this case, an addiction to the good feeling that comes from receiving money or possessions—which can ultimately lead to negative consequences and harm the individual’s well-being. Addiction to spending money—sometimes known as shopaholism—is another, more common type of money-associated process addiction.

Wealthy children may be more troubled

Children growing up in wealthy families may seem to have it all, but having it all may come at a high cost. Wealthier children tend to be more distressed than lower-income kids, and are at high risk for anxiety, depression, substance abuse, eating disorders, cheating, and stealing. Research has also found high instances of binge-drinking and marijuana use among the children of high-income, two-parent, white families.

“In upwardly mobile communities, children are often pressed to excel at multiple academic and extracurricular pursuits to maximize their long-term academic prospects—a phenomenon that may well engender high stress,” writes psychologist Suniya Luthar in “The Culture Of Affluence.” “At an emotional level, similarly, isolation may often derive from the erosion of family time together because of the demands of affluent parents’ career obligations and the children’s many after-school activities.”

We tend to perceive the wealthy as “evil”

On the other side of the spectrum, lower-income individuals are likely to judge and stereotype those who are wealthier than themselves, often judging the wealthy as being “cold.” (Of course, it is also true that the poor struggle with their own set of societal stereotypes.)

Rich people tend to be a source of envy and distrust, so much so that we may even take pleasure in their struggles, according to Scientific American . According to a University of Pennsylvania study entitled “ Is Profit Evil? Associations of Profit with Social Harm ,” most people tend to link perceived profits with perceived social harm. When participants were asked to assess various companies and industries (some real, some hypothetical), both liberals and conservatives ranked institutions perceived to have higher profits with greater evil and wrongdoing across the board, independent of the company or industry’s actions in reality.

Money can’t buy happiness (or love)

We tend to seek money and power in our pursuit of success (and who doesn’t want to be successful, after all?), but it may be getting in the way of the things that really matter: happiness and love.

There is no direct correlation between income and happiness. After a certain level of income that can take care of basic needs and relieve strain ( some say $50,000 a year , some say $75,000 ), wealth makes hardly any difference to overall well-being and happiness and, if anything, only harms well-being: Extremely affluent people actually suffer from higher rates of depression . Some data has suggested money itself doesn’t lead to dissatisfaction—instead, it’s the ceaseless striving for wealth and material possessions that may lead to unhappiness. Materialistic values have even been linked with lower relationship satisfaction .

But here’s something to be happy about: More Americans are beginning to look beyond money and status when it comes to defining success in life. According to a 2013 LifeTwist study , only around one-quarter of Americans still believe that wealth determines success.

This article originally appeared in the Huffington Post .

About the Author

Carolyn gregoire, you may also enjoy.

Does Wealth Reduce Compassion?

Low-Income People Quicker to Show Compassion

Why Does Happiness Inequality Matter?

Are the Rich More Lonely?

What Inequality Does to Kids

When the Going Gets Tough, the Affluent Get Lonely

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Why Are We So Emotional about Money?

- Rakshitha Arni Ravishankar

Our relationship with money is just as personal as any other big relationship in our lives.

If money brings up a lot of emotions for you, you’re not alone. Financial expert Ramit Sethi explains our relationship with money is just as personal and valuable as any other relationship in our life. Here are some ways to build a healthier relationship with money.

- First, know that it’s okay to feel emotional about money. Use them to understand your values, your fears, your needs, and your wants.

- Then, start educating yourself about money. Understand what terms like credit, loan, compound interest, etc. mean. Often, the fear of money comes from a lack of knowledge or awareness about it.

- Finally, be inspired by money. Instead of focusing on what you don’t have, think about what money can buy. Don’t just focus on the materialistic aspects but also the experiences it affords you.

How do you feel about money?

- RR Rakshitha Arni Ravishankar is an associate editor at Ascend.

Partner Center

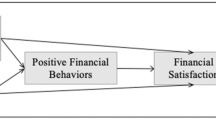

Catch Them Young: Impact of Financial Socialization, Financial Literacy and Attitude Toward Money on Financial Well-being of Young Adults

- International IJC 44(3)

- Indian Institute of Management Kashipur

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

- Burgundy School of Business

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- J Fam Econ Issues

- Pardeep Ahlawat

- Aarti Deveshwar

- Mahender Yadav

- EUR J MARKETING

- Welf Hermann Weiger

- Christian Tetteh-Afi

- Tobias Kraemer

- Genesis Anne B. Rodriguez

- J Financ Serv Market

- Müzeyyen Çiğdem Akbaş

- Anjelica Dew O. Oro

- Intan Maizura Abdul Rashid

- Syahril Iman Faisal

- Noraznira Abd Razak

- Jeswin Jose

- Nabanita Ghosh

- Karold A Saludez

- Jay-Ar R Anunciacion

- Lyka O. Castillo

- Lukas Menkhoff

- Int J Consum Stud

- INT J BEHAV DEV

- QUAL LIFE RES

- Genevieve E. O'Connor

- Barbara O'Neill

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

260 Money Topics to Write About & Essay Examples

Looking for a topic about money? Money won’t leave anyone indifferent! There are lots of money essay topics for students to explore.

🏆 Best Money Essay Examples & Ideas

👍 good money essay topics, 💡 easy money topics to write about, 📃 interesting topics about money, 📑 good research topics about money, 📌 most interesting money topics to write about, ❓ research questions about money.

You might want to focus on the issue of money management or elaborate on why money is so important nowadays. Other exciting topics for a money essay are the relation between money and love, the role of money in education, etc. Below you’ll find a list of money topics to write about! These ideas can also be used for discussions and presentations. Money essay examples are a nice bonus to inspire you even more!

- Can Money Buy You Happiness? First of all, given that happiness is related to the satisfaction of personal needs, there is also a need to consider the essential need of human life such as housing, medicine, and food.

- Connection Between Money and Happiness Critical analysis of money-happiness relationship shows that socioeconomic factors determine the happiness of an individual; therefore, it is quite unsatisfactory to attribute money as the only factor and determinant of happiness.

- Money as a Form of Motivation in the Work Place This then shows that money can and is used as a motivational factor in the work place so that employees can strive to give their best and their all at the end of the day.

- I Don’t Believe Money Can Buy Happiness This shows that as much as money is essential in acquisition and satisfaction of our needs, it does not guarantee our happiness by its own and other aspects of life have to be incorporated to […]

- Money, Happiness and Relationship Between Them The research conducted in the different countries during which people were asked how satisfied they were with their lives clearly indicated the existence of a non-linear relationship between the amount of money and the size […]

- Anti-Money Laundering and Hawala System in Dubai To prevent money launders and agents, most countries enacted the anti-money laundering acts with the goal of tracking and prosecuting offenders.

- Money and Banking: General Information The essay gives the definition of money and gives a brief description of the functions of money. As a store of value, money can be saved reliably and then retrieved in the future.

- Money: Good or Evil? Comparing & Contrasting While there are those amongst us who subscribe to the school of though that “money is the source of all evil”, others are of the opinion that money can buy you anything, literary.

- Time Value of Money: Importance of Calculating Due to fluctuations in economies, all organizations need to take into consideration concepts of the time value of money in any investment venture.

- The Global Media Is All About Money and Profit Making It is noteworthy that the advertisement are presented through the media, which confirms the assertion that global media is all about money and profit making. The media firms control the information passed to the public […]

- Does Money Buy Happiness? Billions of people in all parts of the world sacrifice their ambitions and subconscious tensions on the altar of profitability and higher incomes. Yet, the opportunity costs of pursuing more money can be extremely high.

- Discussion: Can Money Buy Happiness? Reason Two: Second, people are psychologically predisposed to wanting more than they have, so the richer people are, the less feasible it is to satisfy their demands.

- Prices Rise When the Government Prints too Much Money Makinen notes that an increase in the supply of money in an economy relative to the output in the economy could lead to inflationary pressure on prices of goods and services in the economy.

- Money and Modern Life The rich and the powerful are at the top while the poor and helpless are at the bottom, the rest lie in-between.

- Two Attitudes Towards Money The over-dependence on money to satisfy one’s emotional needs is a negative perspective of money. The positive attitude of money is rarely practiced by people.

- Why Money Is Important: Benefits & Downsides The notion originated from the Bible because the person who made Jesus suffer on the cross was enticed by the love of money to forsake Jesus.

- Giving Money to the Homeless: Is It Important? The question of whether a person should give money to a homeless person or not is a complicated one and cannot have the right answer.

- Anti-Money Laundering in Al Ansari Exchange Case Study Details Company name: Al Ansari Exchange Headquarters: Dubai, United Arab Emirates Sector: Financial Services Number of employees: 2500 Annual gross revenue: UAED 440.

- Are Workers Motivated Mainly by Money? Related to the concept of work and why people work is the original concept developed by Karl Marx in the so-called conflict theory.

- Money and Its Value Throughout the World History What is important is the value that people place on whatever unit they refer to as amoney.’ Money acts as a medium of exchange and an element of measurement of the value of goods and […]

- Efforts to Raise Money for Charity However, the point is that charity is supposed to be for a simple act of giving and not expecting any returns from it.

- Money and Happiness in Poor and Wealthy Societies Comprehending the motivations for pursuing money and happiness is the key to understanding this correlation. The Easterlin paradox summed this view by showing that income had a direct correlation with happiness.

- Time Value of Money Compounding was done on the amount that I had lent out using the market rate over the duration of time the person held my money.

- Success and Money Correlation The development of the information technologies and the ongoing progress led to the reconsideration of the values and beliefs. It is significant to understand that there is no right or wrong answer for the question […]

- “College Is a Waste of Time and Money” by Bird Bird’s use of logical fallacies, like if students do not want to go to college, they should not do it until the reasons of their unwillingness are identified, proves that it is wrong to believe […]

- Money, Success, and Relation Between Them In particular, the modern generation attaches so much importance to money in the sense that success and money are presumed to be one and the same thing.

- The Relationship Between Money Supply and Inflation It is evidenced that changing the money supply through the central banks leads to a control of the inflationary situations in the same economy.

- Money Laundering: Most Effective Combat Strategies The practice of money laundering affects the economy and security of a country. Countries have directed their efforts to curb money laundering to control the downwards projections of their countries’ economies.

- Strategies to Save and Protect Money Thus, the main points of expenditure will be clearly marked, which will help to exclude the purchase of unnecessary goods and services.

- Money, Happiness and Satisfaction With Life Nonetheless, the previously mentioned examples should be used to remind us that money alone is not a guarantee of happiness, satisfaction with life, and good health.

- The Airtel Money Service: Indian and African Paths When comparing the Indian and African paths in introducing the service, the first difference that arises is the main user of the service as in the case of India, it was the lower middle class.

- Money: Evolution, Functions, and Characteristics It acts as medium of exchange where it is accepted by both buyers and sellers; the buyer gives money to the seller in exchange of commodities.

- Should America Keep Paper Money It is possible to begin the discussion of the need for keeping paper currency from referring to the rights of any people.

- Where Does the Money Go? by Bittle & Johnson Therefore, the authors explain key issues of the national debt in a relatively simple language and provide their opinion on how the country got into that situation and what could be done about it. In […]

- The Use of Money in Business Practices Money is seen as the cause of problems and especially in the minds of emerging market respondents. Through this they can pick up groceries for the old in their neighborhood and make money from this.

- The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World The succinctness of this book lies in the critical analysis and emphasis of the financial history of money in spite of the fact it has impeded some important functions of the global economy.

- Why People Should Donate Time, Money, Energy to a Particular Organization, Charity, or Cause Its vision is to have a world that is free from Alzheimer’s disease.”The Alzheimer’s Association is the leading, global voluntary health organization in Alzheimer’s care and support, and the largest private, nonprofit funder of Alzheimer’s […]

- Money or Family Values First? Which Way to Go As such, family values becomes the epicenter of shaping individual behavior and actions towards the attainment of a certain good, while money assumes the position of facilitating the attainment of a certain good such as […]

- Money Management in the Organization There is a much debate on the issue and several people an financial experts do analyze the historical perspectives of the Active vs Passive money management.

- Two Attitudes Toward Money Two attitudes toward money involve negative perception of money as universal evil and positive perception of money as source of good life and prosperity.

- Relation Between Money and Football In the English league, clubs have been spending millions to sign up a player in the hope that the player will turn the fortunes of the company for the good.

- “From Empire to Chimerica” in “The Ascent of Money” In the chapter “From Empire to Chimerica,” Niall Ferguson traces back the history of the Western financial rise and suggests that nowadays it is being challenged by the developing Eastern world. The hegemonic position of […]

- Paper Money and Its Role Throughout History The adoption of the paper money was considered to be beneficial for both the wealth of the country and the individual businessmen.

- Electronic Money: Challenges and Solutions First of all, it should be pointed out that money is any type of phenomenon which is conventionally accepted as a universal carrier of value, or “any generally accepted means of payment which is allowed […]

- Exploring the Relationship Between Education and Money A person cannot be able to change his/her ascribed status in the society, but only through education a person is able to change his/her Socio-economic status and to some extent that of his/her family once […]

- Drugs: The Love of Money Is the Root of All Evils The political issues concerning the use of drugs consist of, but not limited to, the substances that are defined as drugs, the means of supplying and controlling their use, and how the society relates with […]

- Money Saving Methods for College Students A budget is one of the methods that a college student can use to save money. In the budget, one should indicate how much to save and the means of saving the money.

- Mobile Money Transfer Service The Vodafone team managed to keep mobile banking service simple to its users. Soon mobile banking became a form of viral marketing and drove the growth of the company and its services.

- Opinion on the Importance of Money In the absence of money, individuals and organizations would be forced to conduct transactions through barter trade which is a relatively challenging system due to existence of double coincidence of wants.

- Money Laundering Scene in Police Drama “Ozark” In one of the first season’s episodes, Marty, the main character, illustrates the process of money laundering crime. In the scene, one can see that Marty is fully sane and is committing a crime voluntarily.

- Money From the Christian Perspective Work in Christian missions is a business and since it affects the relationship between the missionary and the people he is trying to reach, missionary funding is essential.

- Business Case Scenario: Missing Money in a Company A possible scenario explaining how money is missing is through the payroll department my first argument seeks to prove the payroll department as the loophole of the company’s misfortunes.

- Sports Stadiums’ Funding by Public Money The issue is controversial from an ethical point of view since not all citizens whose taxes can be spent on the construction of the stadium are interested in or fond of sports.

- Money Laundering: The Kazakhgate Case He was accused of breaking the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1974 and money laundering by the U.S.attorney’s office for the Southern District of New York.

- The Ways Terrorists Raise and Move Money Moreover, the government has put into action the freezing orders and blocking of united states individuals who are presumed to have a hand in terrorist activities.

- “Money as a Weapon” System and Fiscal Triad Furthermore, the fiscal triad encompasses the procurement of products and services and the disbursement and accounting of public funding. Fiscal legislation and contracts are two key components of the “money as a weapon” system.

- The Fiscal Triad and Money as a Weapon System The reliance on the unit commanders sparked the development of the complementary strategy, “Money as a Weapon System,” which became a focal point of the Iraq and Afghanistan campaigns.

- Saving Money Using Electric or Gas Vehicles The central hypothesis of the study is that the electric car will save more money than gas ones. The main expected outcome that the study is counting on is a confirmation of the presented hypothesis […]

- Traditional vs. Modern Forms of Money The most significant argument for the continuing existence of traditional forms of money is the impossibility of converting all financial resources into a digital form.

- Money Laundering Through Cryptocurrencies This study will try to critique the approaches used by countries to address the aspect of money laundering activities and the risks posed by digital currencies.

- Time Value of Money: What You Should Know The time value of money is a paramount financial concept, according to which a certain amount is now worth more than the same amount in the future.

- The Lebanese-Canadian Bank’s Money Laundering The bank was later banned from using the dollar by the American treasury; this resulted in the collapse and eventual sale of the bank.L.C.B.had to pay a settlement fine of one hundred and two million […]

- Play Money Paper: A Report Betas of the Companies in the Portfolio It is noteworthy that in the given portfolio, the beta indices of the companies involved vary considerably.

- Integration of Business Ethics in Preventing Money Laundering Schemes The shipping information within the document seems inaccurate with the intention to launder money from the buyer. The contribution of ocean carrier in the transaction process is doubtful to a given extent.

- Trade-Based Money Laundering The purpose of this paper is to research the subject of trade-based money laundering, its impact on global scene and export controls, identify types of trade finance techniques used to launder illegal money, and provide […]

- Impact of Natural Disasters on Money Markets and Investment Infusion of funds from the central bank during natural disasters results in higher process of exports as a direct result of an increase in the value of the local currency.

- The Perception of Money, Wealth, and Power: Early Renaissance vs. Nowadays In the Renaissance period, power was a questionable pursuit and could be viewed as less stable due to more frequent upheavals.

- Financial Institutions and Money Money is a store of value because it can be saved now and used to purchase se goods and services in the future.

- Researching of the Time Value of Money After receiving the loan, one of the monetary policies that would help PIIGS to stabilize is the deflation of their currency, in this case, the Euro.

- Anti-Money Laundering: Financial Action Task Force Meanwhile, given the limited access for physical assessment of state jurisdictions, it is likely that current provisions of FATF are yet to be revised in spite of pandemic travel and assessment restrictions.

- Anti-Money Laundering in the UK Jurisdiction The regime adopted in the UK is based on the provisions of “the Terrorism Act of 2000, the Proceeds of Crime Act of 2002, as well as the Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing, and Transfer of […]

- Trade-Based Money Laundering and Its Attractiveness The proliferation of the trade-based money laundering is directly related to the growing complexity of international trade systems, where new risks and vulnerabilities emerge and are seen as favorable among terrorist organizations seeking for the […]

- Money Laundering and Sanctions Regulatory Frameworks Under the provisions of OFAC, the company has violated the cybersecurity rules that might indirectly bring a significant threat to the national security or the stability of the United States economy by engaging in online […]

- Type Borrowing Money: Margin Lending In the defense of the storm financial planning firm, BOQ submitted to the authorities that in view of banking regulatory policies, storm had not contravened any of the policies and this is the reason why […]

- Lessons on Financial Planning Using Money Tree Software Financial planning remains a fundamental function among the investors in coming up with a method of using the finances presently and in the future.

- The Supply of Money in the Capitalist Economy In the capitalist economy that the world is currently based on, the supply of money plays a significant role in not only affecting salaries and prices but also the growth of the economy.

- Time Value of Money Defined and Calculations Simply put, the same value of money today is worth the same value in future. The time value of money can therefore be defined as the calculated value of the money taking into consideration various […]

- Anti Money Laundering and Financial Crime There are a number of requirements by the government on the AML procedures to be developed and adopted by the firms in the financial service in industry in an attempt to fight the illegal practice.

- Money Tree Software: Financial Planning This return is important because: It represents the reward the business stakeholders and owner of the business get in staking their money on the business currently and in the future It rewards the business creditors […]

- Money Management: Investment on Exchange-Traded Funds The essay will discuss the possibility of investing in a number of selected ETFs in connection to an investment objective of an individual.

- What Is Money Laundering and Is It Possible to Fight It Certainly and more often money involved in laundering is obtained from illegal activities and the main objective of laundering is to ‘clean’ the dirty money and give it a legitimate appearance in terms of source.

- Time Value of Money: Choosing Bank for Deposit The value of the money is determined by the rate of return that the bank will offer. The future value of the two banks is $20,000 and $22,000 for bank A and bank B respectively.

- How Money Market Mutual Funds Contributed to the 2008 Financial Crisis While how the prices of shares fell below the set $1 per share was a complex process, it became one of the greatest systemic risks posed by the MMMF to the investors and the economy […]

- Time Value of Money From an Islamic Perspective Islamic scholars say that the time value of money and the interest rates imposed on money lent are the reasons why the poor keep on getting poor and the rich richer.

- Rational Decision Making: Money on Your Mind The mind is responsible for making financial decision and it is triggered by the messages we receive on the day to day activities. Lennick and Jordan explain that, we have two systems in the brain; […]

- A Usability Test Conducted on GE Money.com.au It is common knowledge that the easier it is to access services and products on a given website the more likely users will be encouraged to come back.

- “Most Important Thing Is Money Ltd”: Vaccination Development Thus, necessary powers have been vested with the Secretary of State for Health in England, through the recommendations of the Joint Committee on Vaccinations and Immunisation to enforce such preventive steps, through necessary programs that […]

- Money Investments in the Companies and Bonds The stock volume is on the low level now, about 30, but it is connected with the crisis in the world and the additional investment may support the company and increase it. In general the […]

- How the Virus Transformed Money Spending in the US In the article featured in the New York Times, Leatherby and Geller state that the rate at which people spend their money has rapidly decreased due to the emergence of the virus in the United […]

- The Role of Money and Class Division in Society The image of modern American society tries in vain to convey the prevalence of personality over social division. Americans’ perception of financial status has been shaped for years by creating the notion of the “American […]

- Money and American Classes in 1870-1920 Wherein, the time of the stock market emergence was the time of the ongoing “carnival,” where the mystical power of money transferred to miraculous products and medicines and compelling advertisements.

- The Ascent of Money – Safe as Houses Looking from a broad historical perspective, Niall Ferguson devotes the chapter “Save as Houses” to the observation of the real estate concept transformation, describes the place of the real estate market in the economic systems […]

- The Ascent of Money – Blowing Bubbles The price for a share tells how much people rely on the cost of the company in the future. The life of a stock market represents the reflection of human moods on the price of […]

- Canada’s Role in the History of Money: The Relationship Between Ownership and Control Individuals with the predominant shares gain the directorship of the wealth production channels and as such gain control of the diversified owners.

- Why Non-Monetary Incentives Are More Significant Than Money It is important to recognize that both monetary and non-monetary incentives, otherwise known as total rewards, are offered to employees in diverse ways for purposes of attracting and motivating them to the ideals of the […]

- Money Role in Macro Economy The dollar is till now the most accepted currency in the world and this dollar fluctuation that has been caused by the worst recession in American history since the time of the Great Depression is […]

- Change in the Value of Money According to Keynes To explain the effect of inflation on investors, Keynes delves into the history of inflation through the nineteenth century and tries to explain the complacency of investors at the beginning of the First World War […]

- Organizational Communication & the “Money” Aspect While the use of this information is critical for both ensuring survival of the organization and being a frontrunner in its strategies for the future, there are large boulders in use of this information effectively, […]

- Money Makes You Happy: Philosophical Reasoning It is possible to give the right to the ones who think that money can buy happiness. This conclusion is not accepted by psychologists who think that wealth brings the happiness only in the moment […]

- Spare Change: Giving Money to the “Undeserving Poor” To address the central theme of the article, one need to delve deeper into the psyche of giving alms and money to the poor people we meet on the street.

- Money Laundering and Terrorist Finance However, the balance money after the sham gambling is transferred to another ordinary bank account, thereby creating a legal status for the laundered money as if it has come from gambling and will be employed […]

- City Planning. Too Much Money: Why Savings Are Bad The scenario is that the expected growth in economies where the rate of savings is high has not shown a corresponding increase in growth rate also.

- Debates in Endogenous Money: Basil Moore The value of the currency was determined by the value of the precious metal used to mint the currency. From the time Federal Reserve took control of money and credit, economic consistency is attained by […]

- Money and Banking. Financial Markets The essay will examine the essence and the importance of the above-mentioned financial phenomena and see how their interrelation, especially in the negative context, can influence the state of things in society.

- Money and Justice: High-Profile Cases It is estimated that thousands of persons bracketed in the ‘poor’ sector of society go to jail annually in the United States without having spoken to a lawyer.

- Accounting for Public Money After Railway Privatization There were very many problems prior to the railway privatization in 1990.one of the problems that led to the privatization of the railway line in the UK was the misappropriation of taxpayers’ money.

- Time Value of Money and Its Financial Applications The time value of money refers to the idea that money available at the present time is worth more than the same amount in the future, due to its potential earning capacity.

- Money Laundering in the USA and Australia The International Money Fund has established that the aggregate size of money laundering in the World is approximately four percent of the world’s gross domestic product.

- Locke’s Second Treatise of Government and Voltaire’s Candide’s Value on Money Both written at a time when philosophers had started questioning the relevance of capitalism and the concept of wealth creation, it is evident that the two authors were keen on explaining the power of money […]

- The Concept of Money Laundering The first issue I have learned is that the main problem lies in the presence of Big Data that includes trillions of transactions of various financial organizations and systems.

- Time Value of Money – Preparing for Home Ownership The purchase price of the house is determined by using the following formula in Excel. 66 The down payment is 20% of the future value of the house, i.e, $40,278.13.

- Martin Van Buren: Money and Indian Relocation One of the reasons for such collaboration and understanding is the focus on the values we have. I believe this path will bring us to the land we all would like to live in.

- The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money Money is a determinant of the propensity to consume; hence, the more money one makes, the more that he or she consumes and the converse is the case.

- The Practice of Saving Money Knowledge of the language is also a very crucial component of EAP as it aids the learner in understanding questions and responding to them in their examinations.another differentiating factor between the two varieties of English […]

- How Money Markets Operate? Furthermore, only free markets have shown the resilience that is necessary to accompany the fluctuations in demand and supply of the money markets.

- History of Money in Spain The production of coins melted from gold also ceased in the year 1904, with the production of that melted from silver ceasing in the year 1910.

- Management: “Marketplace Money” and “Undercover Boss” In this case, the accents are made on the support of the healthy workforce in order to guarantee the better employees’ performance and on the idea of rewards as the important aspects to stimulate the […]

- Money Compensation for Student-Athletes Besides, sports are highly lucrative for colleges, and students whose labor brings the revenues should share the part of them not to lose the interest in such activities.

- Chapters 1-3 of “Money Mechanics” by David Ashby The retained amount of money in the commercial bank is the primary reserve. The banks can decide to reduce their working reserve, and the money obtained is transferred to the excess reserve fund in accounts […]

- Banking in David Ashby’s “Money Mechanics” Changes in prices may not have a direct effect on the gross domestic product and the planned expenditures because this is determined by the money that is in supply. This causes the GDP and prices […]

- The UAE Against Money Laundering and Terrorism Financing This valuation of the anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism government of the United Arab Emirates is founded on the forty endorsements and the nine special commendations on extremist supporting of the monetary […]

- UAE Anti-Money Laundering Laws and Their Benefits The legal maintenance of counteraction to the legalization of criminal incomes is carried out by means of a system of laws and regulations, controlling financial, bank, and customs relations and establishing the order of licensing […]

- Money, Their Features, Functions and Importance The first hindrance is the inability of the household to monitor the activities of firms. In this case, it is used to state the value of debt.

- Money Market Development Factors The money market is one of the fundamental elements in the functioning of any state. Under these conditions, the gradual rise of technologies and their implementation in the sphere of financial operations alter the money […]

- “God’ Money is Now My Money” by Stanley Seat It could be said that different priorities and the lack of time for supervision of the employees are the critical reasons for the violation of rules and high frequency of fraud in the religious institutions […]

- International Money Laundering Thus, money laundering has a profound impact on the state of the global economy, as well as on the economy of the U.S.

- Cybercrime and Digital Money Laundering The result of the investigation was the indictment of Western Express and a number of the company’s clients for several charges including stolen credit card data trafficking and money laundering.

- Hawala Remittance System: Anti-Money Laundering Compliance The existence and operation of money remittance systems is one of the primary features of developing economic relation at all scales from local to the global ones.

- Time Value of Money in Investment Planning The author of the post makes a good point that an amount of money is worth more the sooner it is received.

- David Leonhardt: May Be Money Does Buy Happiness After All The case study of Japanese citizens that support Easterlin paradox do not factor in the confounding psychological effects of the Second World War on the entire population and the country.

- Illegal Drug Use, Prostitution and Money Laundering Upon discussing the impact of money laundering, illegal drugs, and prostitution, the paper proposes the issuing of a court order restraining the use of wealth acquired from victimless crimes as one of the approaches to […]

- Getting Beyond: Show Me the Money Nevertheless, underpayment and overpayment are common, leading to dissatisfaction. Notably, compensation is part culture, but analytics will gain traction in the big data era, as start-ups leverage such advantages from experts to manage a sales […]

- Space Programs: Progress or Waste of Money? According to Ehrenfreund, the ingenuity to develop technologies and work in space is part of the progress that comes from space programs. Space programs have led to the development of technologies that improve air transport.

- “The Money Machine: How the City Works” by Coggan The media plays a chief role in educating the public concerning the various financial matters that affect the undertakings of the City.

- Money Evolution in Ancient Times and Nowadays In the means to defining what money is, most of the scholars from the psychological and physiological field have come up with the theoretical aspects of money and the ways it influences the economic growth […]

- Mercantilism, Stamped Money, and Under-Consumption It is paramount to note that he criticizes ideas of Ricardo quite frequently, and he believed that he did not consider the ideas that were suggested by other prominent economists.

- Money Evolution in the 21st Century and Before The history of the world cannot be described effectively without identifying the function of money. Money has been used to measure the value of resources and financial markets.

- Monetary Policy in “The Ascent of Money” by Ferguson The rise of Babylon is closely linked to the evolution of the concept of debt and credit; without bond markets and banks, the brilliance of the Italians would not have materialized; the foundation of the […]

- Money History, Ethical and Social Standarts These moral preconditions of the emergence of money, the social conventions that regulate and control it, and the evolvement of its status in the present-day world can be regarded as the most significant events in […]

- World Money History in the 20th Century and New Objects of Value The class materials examined the developments, hurdles, and systems that have emerged due to the changing roles of money in the global economy.

- Medieval England in “Treatise on the New Money” The availability of standard quality coins was crucial to the effective running of the government and the stability of the economy.

- Blowing Bubbles in Ferguson’s “The Ascent of Money” Moreover, the author shows the connection and similarities between the present collapse of a stock market and the Enron default along with a Mississippi Bubble of the eighteenth century that was created by John Law, […]

- Human Bondage in Ferguson’s “The Ascent of Money” One of the greatest revolutions in the ascent of money after the creation of credit banks, the center of the discussion in this chapter is on how issuing bonds can help governments to borrow money […]

- Money History, Bonds, Market Bubbles, and Risks The concept was so important to human progress that the evolution of the financial system needed to support social and economic development resulted in the establishment of the banking system known today.

- Park Avenue: Money, Power and the American Dream This is one of the drawbacks that should be taken into account by the viewers who want to get a better idea about the causes of the problems described in the movie.

- Deflation in the Quantity Theory of Money The present paper analyzes the recent revelations using the quantity theory of money and concludes that the United States Federal Reserve can reverse the anticipated deflation tide by increasing the amount of money circulating in […]

- Money, Its Purpose and Significance in History Money is the undisputed determinant of quality of life for inhabitants of the modern world. The concerns of money have become pertinent to people all over the world, including the ones who are living in […]

- “Who Stole the Money, and When?” by Greenberg The purpose of research developed in the chosen article is to identify possible personal and situational variables that may affect employee theft in a certain work setting and explain their relation to unethical behavior that […]

- Money History From the Middle Ages to Mercantilism Due to the writing, the idea of bond marketing evolved as a reaction of separate governments to the crisis of money flows.

- Money Development From 600 BC to Nowadays Medici family was a financial symbol in Europe huge in success and power in the 16th century. A system of money in deposits and floating exchange rates was introduced to end centuries-old links between money […]

- Dreams of Avarice in Ferguson’s “The Ascent of Money” The chapter “Dreams of Avarice” of the book “The Ascent of Money” explores different stages of development of money functioning in the world by relating them to corresponding historical events.

- Market Society in “What Money Can’t Buy” by Sandels Thus, the author states that the market economy is a positive creation of people while the use of market values in all aspects of people’s life is a negative and even destructive trend.

- Employee Theft in “Who Stole the Money, and When?”

- European Union Anti-Money Laundering Directive

- Park Avenue: Money, Power and the American Dream – Movie Analysis

- T-Shirts “SENIOR 2016” and Time Value of Money

- Time and Money in “Neptune’s Brood” by Charles Stross

- Virgin Money Company’s Business Model in Canada

- Money in History and World Cultures

- Is College Education Worth the Money

- Artworks Comparison: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and Tribute Money

- Money and Happiness Connection – Philosophy

- “Art for Money’s Sake” by William Alden

- Central Bank of Bahrain and Money Supply Regulation

- Psychological Research: Money Can Buy Happiness

- Finance: The History of Money

- Finance in the Book “The Ascent of Money” by Niall Ferguson

- Criminal Law: Blood Money From the Human Organs Sale

- Money as an Emerging Market Phenomenon

- Cyber-Crime – New Ways to Steal Identity and Money

- The Case of Stolen Donation Money

- Money and Banking: The Economic Recession of 2007

- Money and Banking: David S. Ashby’s Perspective

- Christian Moral Teaching and Money

- Money and Capital Markets: Turkey, India and China

- Money and Capital Markets: Central Banks

- Anti Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism

- Mobile Money Transfer as an Alternative Product for Vodafone Group Plc

- UK and USA During the Period 2000-2010: Consumer Price Index, Unemployment Rate, Money Supply and Interest Rate

- Money Mechanics in the U.S.

- Money and Markets vs. Social Morals

- Money Laundering In Saudi Arabia

- Inflation Tax – Printing More Money to Cover the War Expenses

- Banks and the Money Supply

- Money Mechanics in Banks System

- Money Laundering In Russia

- Money and Work Performance

- Sports and Money in Australia

- Money Supply and Exchange Rates

- Central Banking and the Money Supply

- The Different Roles Played By the Central Bank, Depository Institutions, and Depositors in the Determination of Money Supply

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Karl Marx: The Role of Money in Human Life

- How Saudi Banks Deal With Money Laundery

- The Ascent of Money

- Niall Ferguson’s ‘The Ascent of Money’

- Role of Money in the American Dream’s Concept

- Money, Motivation and Employee Performance

- Money and Commodity Circulatory Processes

- Motivate Your Employees produced by BNet Video for CBS Money Watch

- We Should Use Tax Money to Enforce Mandatory Drug Treatments on Drug

- The World Surrounded by Money

- The World of Money

- Edwin Arlington Robinson: Money and Happiness in “Richard Cory”

- Federal Reserve; Money and Banking

- Ways to Spend Money in Saudi Arabia

- Sports Industry: Morality vs. Money

- Making Money on Music: The Company That Has to Stay Afloat

- Federal Reserve and the Role of Money in It

- What Do Money and Credit Tell Us About Actual Activity in the United States?

- What Influence Does Money Have on Us Politics?

- Can Money Change Who We Are?

- Does Government Spending Crowd Out Donations of Time and Money?

- Does More Money Mean More Bank Loans?

- Are Corporate Ceos Earning Too Much Money?

- Did the Turmoil Affect Money-Market Segmentation in the Euro Area?

- How Appealing Are Monetary Rewards in the Workplace?

- How Does Inflation Affect the Function of Money?

- Can Banks Individually Create Money Out of Nothing?

- Are Credit Cards Going to Be the Money of the Future?

- Does Money Protect Health Status?

- Can Cryptocurrencies Fulfill the Functions of Money?

- What Tools Used by the Federal Reserve to Control Money Supply?

- Are Athletes Overpaid Money Professional Sports?

- Does Electronic Money Mean the Death of Cash?

- What Does Motivate Employees and Whether Money a Key?

- What Are the Three Functions of Money?

- Are Gym Memberships Worth the Money?

- Does Broad Money Matter for Interest Rate Policy?

- Does Money Help Predict Inflation?

- Does One’s Success Depend on the Amount of Money a Person Earns?

- How Does Federal Reserve Control the Money Supply?

- Does Interest Rate Influence Demand for Money?

- Does Commodity Money Eliminate the Indeterminacy of Equilibria?

- Are College Degrees Worth the Money?

- Can Money Matter for Interest Rate Policy?

- How Banks Create Money and Impact of Credit Booms?

- How Can Virtualization Save Organization Money?

- Can Money Diminish Student Performance Disparities Across Regions?

- Wall Street Questions

- Time Management Essay Titles

- Stress Titles

- Bitcoin Research Topics

- Technology Essay Ideas

- Charity Ideas

- Economic Topics

- Cheating Questions

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 2). 260 Money Topics to Write About & Essay Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/money-essay-topics/

"260 Money Topics to Write About & Essay Examples." IvyPanda , 2 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/money-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '260 Money Topics to Write About & Essay Examples'. 2 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "260 Money Topics to Write About & Essay Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/money-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "260 Money Topics to Write About & Essay Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/money-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "260 Money Topics to Write About & Essay Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/money-essay-topics/.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Philosophy of Money and Finance

Finance and philosophy may seem to be worlds apart. But they share at least one common ancestor: Thales of Miletus. Thales is typically regarded as the first philosopher, but he was also a financial innovator. He appears to have been what we would now call an option trader. He predicted that next year’s olive harvest would be good, and therefore paid a small amount of money to the owners of olive presses for the right to the next year’s use. When the harvest turned out to be as good as predicted, Thales earned a sizable amount of money by renting out the presses (Aristotle, Politics , 1259a).

Obviously, a lot has changed since Thales’ times, both in finance and in our ethical and political attitudes towards finance. Coins have largely been replaced by either paper or electronic money, and we have built a large infrastructure to facilitate transactions of money and other financial assets—with elements including commercial banks, central banks, insurance companies, stock exchanges, and investment funds. This institutional multiplicity is due to concerted efforts of both private and public agents, as well as innovations in financial economics and in the financial industry (Shiller 2012).

Our ethical and political sensitivities have also changed in several respects. It seems fair to say that most traditional ethicists held a very negative attitude towards financial activities. Think, for example, of Jesus’ cleansing of the temple from moneylenders, and the widespread condemnation of money as “the root of all evil”. Attitudes in this regard seem to have softened over time. However, the moral debate continues to recur, especially in connection with large scandals and crises within finance, the largest such crisis in recent memory of course being the global financial crisis of 2008.

This article describes what philosophical analysis can say about money and finance. It is divided into five parts that respectively concern (1) what money and finance really are (metaphysics), (2) how knowledge about financial matters is or should be formed (epistemology), (3) the merits and challenges of financial economics (philosophy of science), (4) the many ethical issues related to money and finance (ethics), and (5) the relationship between finance and politics (political philosophy).

1.1 What is Money?

1.2 what is finance, 2. epistemology, 3. philosophy of science, 4.1.1 the love of money, 4.1.2 usury and interest, 4.1.3 speculation and gambling, 4.2.1 deception and fraud, 4.2.2 avoiding conflicts of interest, 4.2.3 insider trading, 4.3.1 systemic risk and financial crises, 4.3.2 microfinance, 4.3.3 socially responsible investment, 5.1 financialization and democracy, 5.2 finance, money, and domestic justice, 5.3 finance and global justice, other internet resources, related entries, 1. metaphysics.

Money is so ever-present in modern life that we tend to take its existence and nature for granted. But do we know what money actually is? Two competing theories present fundamentally different ontologies of money.

The commodity theory of money: A classic theory, which goes back all the way to Aristotle ( Politics , 1255b–1256b), holds that money is a kind of commodity that fulfills three functions: it serves as (i) a medium of exchange, (ii) a unit of account, and (iii) a store of value. Imagine a society that lacks money, and in which people have to barter goods with each other. Barter only works when there is a double coincidence of wants ; that is, when A wants what B has and B wants what A has. But since such coincidences are likely to be uncommon, a barter economy seems both cumbersome and inefficient (Smith 1776, Menger 1892). At some point, people will realize that they can trade more easily if they use some intermediate good—money. This intermediate good should ideally be easy to handle, store and transport (function i). It should be easy to measure and divide to facilitate calculations (function ii). And it should be difficult to destroy so that it lasts over time (function iii).

Monetary history may be viewed as a process of improvement with regard to these functions of money (Ferguson 2008, Weatherford 1997). For example, some early societies used certain basic necessities as money, such as cattle or grain. Other societies settled on commodities that were easier to handle and to tally but with more indirect value, such as clamshells and precious metals. The archetypical form of money throughout history are gold or silver coins—therefore the commodity theory is sometimes called metallism (Knapp 1924, Schumpeter 1954). Coinage is an improvement on bullion in that both quantity and purity are guaranteed by some third party, typically the government. Finally, paper money can be viewed as a simplification of the trade in coins. For example, a bank note issued by the Bank of England in the 1700s was a promise to pay the bearer a certain pound weight of sterling silver (hence the origin of the name of the British currency as “pounds sterling”).

The commodity theory of money was defended by many classical economists and can still be found in most economics textbooks (Mankiw 2009, Parkin 2011). This latter fact is curious since it has provoked serious and sustained critique. An obvious flaw is that it has difficulties in explaining inflation, the decreasing value of money over time (Innes 1913, Keynes 1936). It has also been challenged on the grounds that it is historically inaccurate. For example, recent anthropological studies question the idea that early societies went from a barter economy to money; instead money seems to have arisen to keep track of pre-existing credit relationships (Graeber 2011, Martin 2013, Douglas 2016).

The credit theory of money: According to the main rival theory, coins and notes are merely tokens of something more abstract: money is a social construction rather than a physical commodity. The abstract entity in question is a credit relationship; that is, a promise from someone to grant (or repay) a favor (product or service) to the holder of the token (Macleod 1889, Innes 1914, Ingham 2004). In order to function as money, two further features are crucial: that (i) the promise is sufficiently credible, that is, the issuer is “creditworthy”; and (ii) the credit is transferable, that is, also others will accept it as payment for trade.

It is commonly thought that the most creditworthy issuer of money is the state. This thought provides an alternative explanation of the predominance of coins and notes whose value is guaranteed by states. But note that this theory also can explain so-called fiat money, which is money that is underwritten by the state but not redeemable in any commodity like gold or silver. Fiat money has been the dominant kind of money globally since 1971, when the United States terminated the convertibility of dollars to gold. The view that only states can issue money is called chartalism , or the state theory of money (Knapp 1924). However, in order to properly understand the current monetary system, it is important to distinguish between states’ issuing versus underwriting money. Most credit money in modern economies is actually issued by commercial banks through their lending operations, and the role of the state is only to guarantee the convertibility of bank deposits into cash (Pettifor 2014).

Criticisms of the credit theory tend to be normative and focus on the risk of overexpansion of money, that is, that states (and banks) can overuse their “printing presses” which may lead to unsustainable debt levels, excessive inflation, financial instability and economic crises. These are sometimes seen as arguments for a return to the gold standard (Rothbard 1983, Schlichter 2014). However, others argue that the realization that money is socially constructed is the best starting point for developing a more sustainable and equitable monetary regime (Graeber 2010, Pettifor 2014). We will return to this political debate below ( section 5.2 ).

The social ontology of money: But exactly how does the “social construction” of money work? This question invokes the more general philosophical issue of social ontology, with regard to which money is often used as a prime example. In an early philosophical-sociological account, Georg Simmel (1900) describes money as an institution that is a crucial precondition for modernity because it allows putting a value on things and simplifies transactions; he also criticizes the way in which money thereby replaces other forms of valuation (see also section 4.1 ).

In the more recent debate, one can distinguish between two main philosophical camps. An influential account of social ontology holds that money is the sort of social institution whose existence depends on “collective intentionality”: beliefs and attitudes that are shared in a community (Searle 1995, 2010). The process starts with someone’s simple and unilateral declaration that something is money, which is a performative speech act. When other people recognize or accept the declaration it becomes a standing social rule. Thus, money is said to depend on our subjective attitudes but is not located (solely) in our minds (see also Lawson 2016, Brynjarsdóttir 2018, Passinsky 2020, Vooys & Dick 2021).

An alternative account holds that the creation of money need not be intentional or declarative in the above sense. Instead money comes about as a solution to a social problem (the double coincidence of wants) – and it is maintained simply because it is functional or beneficial to us (Guala 2016, Hindriks & Guala 2021). Thus what makes something money is not the official declarations of some authority, but rather that it works (functions) as money in a given society (see also Smit et al. 2011; 2016). (For more discussion see the special issue by Hindriks & Sandberg 2020, as well as the entries on social ontology and social institutions ).

One may view “finance” more generally (that is, the financial sector or system) as an extension of the monetary system. It is typically said that the financial sector has two main functions: (1) to maintain an effective payments system; and (2) to facilitate an efficient use of money. The latter function can be broken down further into two parts. First, to bring together those with excess money (savers, investors) and those without it (borrowers, enterprises), which is typically done through financial intermediation (the inner workings of banks) or financial markets (such as stock or bond markets). Second, to create opportunities for market participants to buy and sell money, which is typically done through the invention of financial products, or “assets”, with features distinguished by different levels of risk, return, and maturation.

The modern financial system can thus be seen as an infrastructure built to facilitate transactions of money and other financial assets, as noted at the outset. It is important to note that it contains both private elements (such as commercial banks, insurance companies, and investment funds) and public elements (such as central banks and regulatory authorities). “Finance” can also refer to the systematic study of this system; most often to the field of financial economics (see section 3 ).

Financial assets: Of interest from an ontological viewpoint is that modern finance consists of several other “asset types” besides money; central examples include credit arrangements (bank accounts, bonds), equity (shares or stocks), derivatives (futures, options, swaps, etc.) and funds (trusts). What are the defining characteristics of financial assets?

The typical distinction here is between financial and “real” assets, such as buildings and machines (Fabozzi 2002), because financial assets are less tangible or concrete. Just like money, they can be viewed as a social construction. Financial assets are often derived from or at least involve underlying “real” assets—as, for example, in the relation between owning a house and investing in a housing company. However, financial transactions are different from ordinary market trades in that the underlying assets seldom change hands, instead one exchanges abstract contracts or promises of future transactions. In this sense, one may view the financial market as the “meta-level” of the economy, since it involves indirect trade or speculation on the success of other parts of the economy.

More distinctly, financial assets are defined as promises of future money payments (Mishkin 2016, Pilbeam 2010). If the credit theory of money is correct, they can be regarded as meta-promises: promises on promises. The level of abstraction can sometimes become enormous: For example, a “synthetic collateralized debt obligation” (or “synthetic CDO”), a form of derivative common before the financial crisis, is a promise from person A (the seller) to person B (the buyer) that some persons C to I (speculators) will pay an amount of money depending on the losses incurred by person J (the holder of an underlying derivative), which typically depend on certain portions (so-called tranches) of the cash flow from persons K to Q (mortgage borrowers) originally promised to persons R to X (mortgage lenders) but then sold to person Y (the originator of the underlying derivative). The function of a synthetic CDO is mainly to spread financial risks more thinly between different speculators.

Intrinsic value: Perhaps the most important characteristic of financial assets is that their price can vary enormously with the attitudes of investors. Put simply, there are two main factors that determine the price of a financial asset: (i) the credibility or strength of the underlying promise (which will depend on the future cash flows generated by the asset); and (ii) its transferability or popularity within the market, that is, how many other investors are interested in buying the asset. In the process known as “price discovery”, investors assess these factors based on the information available to them, and then make bids to buy or sell the asset, which in turn sets its price on the market (Mishkin 2016, Pilbeam 2010).

A philosophically interesting question is whether there is such a thing as an “intrinsic” value of financial assets, as is often assumed in discussions about financial crises. For example, a common definition of an “asset bubble” is that this is a situation that occurs when certain assets trade at a price that strongly exceed their intrinsic value—which is dangerous since the bubble can burst and cause an economic shock (Kindleberger 1978, Minsky 1986, Reinhart & Rogoff 2009). But what is the intrinsic value of an asset? The rational answer seems to be that this depends only on the discounted value of the underlying future cash flow—in other words, on (i) and not (ii) above. However, someone still has to assess these factors to compute a price, and this assessment inevitably includes subjective elements. As just noted, it is assumed that different investors have different valuations of financial assets, which is why they can engage in trades on the market in the first place.

A further complication here is that (i) may actually be influenced by (ii). The fundamentals may be influenced by investors’ perceptions of them, which is a phenomenon known as “reflexivity” (Soros 1987, 2008). For example, a company whose shares are popular among investors will often find it easier to borrow more money and thereby to expand its cash flow, in turn making it even more popular among investors. Conversely, when the company’s profits start to fall it may lose popularity among investors, thereby making its loans more expensive and its profits even lower. This phenomenon amplifies the risks posed by financial bubbles (Keynes 1936).

Given the abstractness and complexity of financial assets and relations, as outlined above, it is easy to see the epistemic challenges they raise. For example, what is a proper basis for forming justified beliefs about matters of money and finance?

A central concept here is that of risk. Since financial assets are essentially promises of future money payments, a main challenge for financial agents is to develop rational expectations or hypotheses about relevant future outcomes. The two main factors in this regard are (1) expected return on the asset, which is typically calculated as the value of all possible outcomes weighted by their probability of occurrence, and (2) financial risk, which is typically calculated as the level of variation in these returns. The concept of financial risk is especially interesting from a philosophical viewpoint since it represents the financial industry’s response to epistemic uncertainty. It is often argued that the financial system is designed exactly to address or minimize financial risks—for example, financial intermediation and markets allow investors to spread their money over several assets with differing risk profiles (Pilbeam 2010, Shiller 2012). However, many authors have been critical of mainstream operationalizations of risk which tend to focus exclusively on historical price volatility and thereby downplay the risk of large-scale financial crises (Lanchester 2010, Thamotheram & Ward 2014).

This point leads us further to questions about the normativity of belief and knowledge. Research on such topics as the ethics of belief and virtue epistemology considers questions about the responsibilities that subjects have in epistemic matters. These include epistemic duties concerning the acquisition, storage, and transmission of information; the evaluation of evidence; and the revision or rejection of belief (see also ethics of belief ). In line with a reappraisal of virtue theory in business ethics, it is in particular virtue epistemology that has attracted attention from scholars working on finance. For example, while most commentators have focused on the moral failings that led to the financial crisis of 2008, a growing literature examines epistemic failures.

Epistemic failings in finance can be detected both at the level of individuals and collectives (de Bruin 2015). Organizations may develop corporate epistemic virtue along three dimensions: through matching epistemic virtues to particular functions (e.g., diversity at the board level); through providing adequate organizational support for the exercise of epistemic virtue (e.g., knowledge management techniques); and by adopting organizational remedies against epistemic vice (e.g., rotation policies). Using this three-pronged approach helps to interpret such epistemic failings as the failure of financial due diligence to spot Bernard Madoff’s notorious Ponzi scheme (uncovered in the midst of the financial crisis) (de Bruin 2014a, 2015).

Epistemic virtue is not only relevant for financial agents themselves, but also for other institutions in the financial system. An important example concerns accounting (auditing) firms. Accounting firms investigate businesses in order to make sure that their accounts (annual reports) offer an accurate reflection of the financial situation. While the primary intended beneficiaries of these auditing services are shareholders (and the public at large), accountants are paid by the firms they audit. This remuneration system is often said to lead to conflicts of interest. While accounting ethics is primarily concerned with codes of ethics and other management tools to minimize these conflicts of interests, an epistemological perspective may help to show that the business-auditor relationship should be seen as involving a joint epistemic agent in which the business provides evidence, and the auditor epistemic justification (de Bruin 2013). We will return to issues concerning conflicts of interest below (in section 4.2 ).

Epistemic virtue is also important for an effective governance or regulation of financial activities. For example, a salient epistemic failing that contributed to the 2008 financial crisis seems to be the way that Credit Rating Agencies rated mortgage-backed securities and other structured finance instruments, and with related failures of financial due diligence, and faulty risk management (Warenski 2008). Credit Rating Agencies provide estimates of credit risk of bonds that institutional investors are legally bound to use in their investment decisions. This may, however, effectively amount to an institutional setup in which investors are forced by law partly to outsource their risk management, which fails to foster epistemic virtue (Booth & de Bruin 2021, de Bruin 2017). Beyond this, epistemic failures can also occur among regulators themselves, as well as among relevant policy makers (see further in section 5.1 ).

A related line of work attests to the relevance of epistemic injustice to finance. Taking Fricker’s (2009) work as a point of departure, de Bruin (2021) examines testimonial injustice in financial services, whereas Mussell (2021) focuses on the harms and wrongs of testimonial injustice as they occur in the relationship between trustees and fiduciaries.

Compared to financial practitioners, one could think that financial economists should be at an epistemic advantage in matters of money and finance. Financial economics is a fairly young but well established discipline in the social sciences that seeks to understand, explain, and predict activities within financial markets. However, a few months after the crash in 2008, Queen Elizabeth II famously asked a room full of financial economists in London why they had not predicted the crisis (Egidi 2014). The Queen’s question should be an excellent starting point for an inquiry into the philosophy of science of financial economics. Yet only a few philosophers of science have considered finance specifically (Vergara Fernández & de Bruin 2021). [ 1 ]

Some important topics in financial economics have received partial attention, including the Modigliani-Miller capital structure irrelevance theorem (Hindriks 2008), the efficient market hypothesis (Collier 2011), the Black-Scholes option pricing model (Weatherall 2017), portfolio theory (Walsh 2015), financial equilibrium models (Farmer & Geanakoplos 2009), the concept of money (Mäki 1997), and behavioral finance (Brav, Heaton, & Rosenberg 2004), even though most of the debate still occurs among economists interested in methodology rather than among philosophers. A host of topics remain to be investigated, however: the concept of Value at Risk (VaR) (and more broadly the concept of financial risk), the capital asset pricing model (CAPM), the Gaussian copula, random walks, financial derivatives, event studies, forecasting (and big data), volatility, animal spirits, cost of capital, the various financial ratios, the concept of insolvency, and neurofinance, all stand in need of more sustained attention from philosophers.