An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE Open Med

Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers

Ylona chun tie.

1 Nursing and Midwifery, College of Healthcare Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia

Melanie Birks

Karen francis.

2 College of Health and Medicine, University of Tasmania, Australia, Hobart, TAS, Australia

Background:

Grounded theory is a well-known methodology employed in many research studies. Qualitative and quantitative data generation techniques can be used in a grounded theory study. Grounded theory sets out to discover or construct theory from data, systematically obtained and analysed using comparative analysis. While grounded theory is inherently flexible, it is a complex methodology. Thus, novice researchers strive to understand the discourse and the practical application of grounded theory concepts and processes.

The aim of this article is to provide a contemporary research framework suitable to inform a grounded theory study.

This article provides an overview of grounded theory illustrated through a graphic representation of the processes and methods employed in conducting research using this methodology. The framework is presented as a diagrammatic representation of a research design and acts as a visual guide for the novice grounded theory researcher.

Discussion:

As grounded theory is not a linear process, the framework illustrates the interplay between the essential grounded theory methods and iterative and comparative actions involved. Each of the essential methods and processes that underpin grounded theory are defined in this article.

Conclusion:

Rather than an engagement in philosophical discussion or a debate of the different genres that can be used in grounded theory, this article illustrates how a framework for a research study design can be used to guide and inform the novice nurse researcher undertaking a study using grounded theory. Research findings and recommendations can contribute to policy or knowledge development, service provision and can reform thinking to initiate change in the substantive area of inquiry.

Introduction

The aim of all research is to advance, refine and expand a body of knowledge, establish facts and/or reach new conclusions using systematic inquiry and disciplined methods. 1 The research design is the plan or strategy researchers use to answer the research question, which is underpinned by philosophy, methodology and methods. 2 Birks 3 defines philosophy as ‘a view of the world encompassing the questions and mechanisms for finding answers that inform that view’ (p. 18). Researchers reflect their philosophical beliefs and interpretations of the world prior to commencing research. Methodology is the research design that shapes the selection of, and use of, particular data generation and analysis methods to answer the research question. 4 While a distinction between positivist research and interpretivist research occurs at the paradigm level, each methodology has explicit criteria for the collection, analysis and interpretation of data. 2 Grounded theory (GT) is a structured, yet flexible methodology. This methodology is appropriate when little is known about a phenomenon; the aim being to produce or construct an explanatory theory that uncovers a process inherent to the substantive area of inquiry. 5 – 7 One of the defining characteristics of GT is that it aims to generate theory that is grounded in the data. The following section provides an overview of GT – the history, main genres and essential methods and processes employed in the conduct of a GT study. This summary provides a foundation for a framework to demonstrate the interplay between the methods and processes inherent in a GT study as presented in the sections that follow.

Glaser and Strauss are recognised as the founders of grounded theory. Strauss was conversant in symbolic interactionism and Glaser in descriptive statistics. 8 – 10 Glaser and Strauss originally worked together in a study examining the experience of terminally ill patients who had differing knowledge of their health status. Some of these suspected they were dying and tried to confirm or disconfirm their suspicions. Others tried to understand by interpreting treatment by care providers and family members. Glaser and Strauss examined how the patients dealt with the knowledge they were dying and the reactions of healthcare staff caring for these patients. Throughout this collaboration, Glaser and Strauss questioned the appropriateness of using a scientific method of verification for this study. During this investigation, they developed the constant comparative method, a key element of grounded theory, while generating a theory of dying first described in Awareness of Dying (1965). The constant comparative method is deemed an original way of organising and analysing qualitative data.

Glaser and Strauss subsequently went on to write The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (1967). This seminal work explained how theory could be generated from data inductively. This process challenged the traditional method of testing or refining theory through deductive testing. Grounded theory provided an outlook that questioned the view of the time that quantitative methodology is the only valid, unbiased way to determine truths about the world. 11 Glaser and Strauss 5 challenged the belief that qualitative research lacked rigour and detailed the method of comparative analysis that enables the generation of theory. After publishing The Discovery of Grounded Theory , Strauss and Glaser went on to write independently, expressing divergent viewpoints in the application of grounded theory methods.

Glaser produced his book Theoretical Sensitivity (1978) and Strauss went on to publish Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists (1987). Strauss and Corbin’s 12 publication Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques resulted in a rebuttal by Glaser 13 over their application of grounded theory methods. However, philosophical perspectives have changed since Glaser’s positivist version and Strauss and Corbin’s post-positivism stance. 14 Grounded theory has since seen the emergence of additional philosophical perspectives that have influenced a change in methodological development over time. 15

Subsequent generations of grounded theorists have positioned themselves along a philosophical continuum, from Strauss and Corbin’s 12 theoretical perspective of symbolic interactionism, through to Charmaz’s 16 constructivist perspective. However, understanding how to position oneself philosophically can challenge novice researchers. Birks and Mills 6 provide a contemporary understanding of GT in their book Grounded theory: A Practical Guide. These Australian researchers have written in a way that appeals to the novice researcher. It is the contemporary writing, the way Birks and Mills present a non-partisan approach to GT that support the novice researcher to understand the philosophical and methodological concepts integral in conducting research. The development of GT is important to understand prior to selecting an approach that aligns with the researcher’s philosophical position and the purpose of the research study. As the research progresses, seminal texts are referred back to time and again as understanding of concepts increases, much like the iterative processes inherent in the conduct of a GT study.

Genres: traditional, evolved and constructivist grounded theory

Grounded theory has several distinct methodological genres: traditional GT associated with Glaser; evolved GT associated with Strauss, Corbin and Clarke; and constructivist GT associated with Charmaz. 6 , 17 Each variant is an extension and development of the original GT by Glaser and Strauss. The first of these genres is known as traditional or classic GT. Glaser 18 acknowledged that the goal of traditional GT is to generate a conceptual theory that accounts for a pattern of behaviour that is relevant and problematic for those involved. The second genre, evolved GT, is founded on symbolic interactionism and stems from work associated with Strauss, Corbin and Clarke. Symbolic interactionism is a sociological perspective that relies on the symbolic meaning people ascribe to the processes of social interaction. Symbolic interactionism addresses the subjective meaning people place on objects, behaviours or events based on what they believe is true. 19 , 20 Constructivist GT, the third genre developed and explicated by Charmaz, a symbolic interactionist, has its roots in constructivism. 8 , 16 Constructivist GT’s methodological underpinnings focus on how participants’ construct meaning in relation to the area of inquiry. 16 A constructivist co-constructs experience and meanings with participants. 21 While there are commonalities across all genres of GT, there are factors that distinguish differences between the approaches including the philosophical position of the researcher; the use of literature; and the approach to coding, analysis and theory development. Following on from Glaser and Strauss, several versions of GT have ensued.

Grounded theory represents both a method of inquiry and a resultant product of that inquiry. 7 , 22 Glaser and Holton 23 define GT as ‘a set of integrated conceptual hypotheses systematically generated to produce an inductive theory about a substantive area’ (p. 43). Strauss and Corbin 24 define GT as ‘theory that was derived from data, systematically gathered and analysed through the research process’ (p. 12). The researcher ‘begins with an area of study and allows the theory to emerge from the data’ (p. 12). Charmaz 16 defines GT as ‘a method of conducting qualitative research that focuses on creating conceptual frameworks or theories through building inductive analysis from the data’ (p. 187). However, Birks and Mills 6 refer to GT as a process by which theory is generated from the analysis of data. Theory is not discovered; rather, theory is constructed by the researcher who views the world through their own particular lens.

Research process

Before commencing any research study, the researcher must have a solid understanding of the research process. A well-developed outline of the study and an understanding of the important considerations in designing and undertaking a GT study are essential if the goals of the research are to be achieved. While it is important to have an understanding of how a methodology has developed, in order to move forward with research, a novice can align with a grounded theorist and follow an approach to GT. Using a framework to inform a research design can be a useful modus operandi.

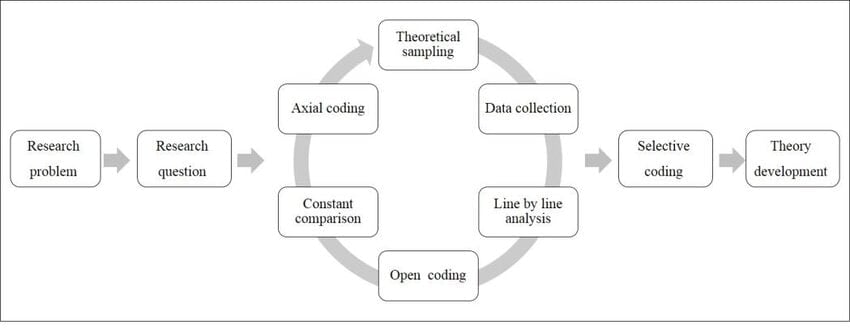

The following section provides insight into the process of undertaking a GT research study. Figure 1 is a framework that summarises the interplay and movement between methods and processes that underpin the generation of a GT. As can be seen from this framework, and as detailed in the discussion that follows, the process of doing a GT research study is not linear, rather it is iterative and recursive.

Research design framework: summary of the interplay between the essential grounded theory methods and processes.

Grounded theory research involves the meticulous application of specific methods and processes. Methods are ‘systematic modes, procedures or tools used for collection and analysis of data’. 25 While GT studies can commence with a variety of sampling techniques, many commence with purposive sampling, followed by concurrent data generation and/or collection and data analysis, through various stages of coding, undertaken in conjunction with constant comparative analysis, theoretical sampling and memoing. Theoretical sampling is employed until theoretical saturation is reached. These methods and processes create an unfolding, iterative system of actions and interactions inherent in GT. 6 , 16 The methods interconnect and inform the recurrent elements in the research process as shown by the directional flow of the arrows and the encompassing brackets in Figure 1 . The framework denotes the process is both iterative and dynamic and is not one directional. Grounded theory methods are discussed in the following section.

Purposive sampling

As presented in Figure 1 , initial purposive sampling directs the collection and/or generation of data. Researchers purposively select participants and/or data sources that can answer the research question. 5 , 7 , 16 , 21 Concurrent data generation and/or data collection and analysis is fundamental to GT research design. 6 The researcher collects, codes and analyses this initial data before further data collection/generation is undertaken. Purposeful sampling provides the initial data that the researcher analyses. As will be discussed, theoretical sampling then commences from the codes and categories developed from the first data set. Theoretical sampling is used to identify and follow clues from the analysis, fill gaps, clarify uncertainties, check hunches and test interpretations as the study progresses.

Constant comparative analysis

Constant comparative analysis is an analytical process used in GT for coding and category development. This process commences with the first data generated or collected and pervades the research process as presented in Figure 1 . Incidents are identified in the data and coded. 6 The initial stage of analysis compares incident to incident in each code. Initial codes are then compared to other codes. Codes are then collapsed into categories. This process means the researcher will compare incidents in a category with previous incidents, in both the same and different categories. 5 Future codes are compared and categories are compared with other categories. New data is then compared with data obtained earlier during the analysis phases. This iterative process involves inductive and deductive thinking. 16 Inductive, deductive and abductive reasoning can also be used in data analysis. 26

Constant comparative analysis generates increasingly more abstract concepts and theories through inductive processes. 16 In addition, abduction, defined as ‘a form of reasoning that begins with an examination of the data and the formation of a number of hypotheses that are then proved or disproved during the process of analysis … aids inductive conceptualization’. 6 Theoretical sampling coupled with constant comparative analysis raises the conceptual levels of data analysis and directs ongoing data collection or generation. 6

The constant comparative technique is used to find consistencies and differences, with the aim of continually refining concepts and theoretically relevant categories. This continual comparative iterative process that encompasses GT research sets it apart from a purely descriptive analysis. 8

Memo writing is an analytic process considered essential ‘in ensuring quality in grounded theory’. 6 Stern 27 offers the analogy that if data are the building blocks of the developing theory, then memos are the ‘mortar’ (p. 119). Memos are the storehouse of ideas generated and documented through interacting with data. 28 Thus, memos are reflective interpretive pieces that build a historic audit trail to document ideas, events and the thought processes inherent in the research process and developing thinking of the analyst. 6 Memos provide detailed records of the researchers’ thoughts, feelings and intuitive contemplations. 6

Lempert 29 considers memo writing crucial as memos prompt researchers to analyse and code data and develop codes into categories early in the coding process. Memos detail why and how decisions made related to sampling, coding, collapsing of codes, making of new codes, separating codes, producing a category and identifying relationships abstracted to a higher level of analysis. 6 Thus, memos are informal analytic notes about the data and the theoretical connections between categories. 23 Memoing is an ongoing activity that builds intellectual assets, fosters analytic momentum and informs the GT findings. 6 , 10

Generating/collecting data

A hallmark of GT is concurrent data generation/collection and analysis. In GT, researchers may utilise both qualitative and quantitative data as espoused by Glaser’s dictum; ‘all is data’. 30 While interviews are a common method of generating data, data sources can include focus groups, questionnaires, surveys, transcripts, letters, government reports, documents, grey literature, music, artefacts, videos, blogs and memos. 9 Elicited data are produced by participants in response to, or directed by, the researcher whereas extant data includes data that is already available such as documents and published literature. 6 , 31 While this is one interpretation of how elicited data are generated, other approaches to grounded theory recognise the agency of participants in the co-construction of data with the researcher. The relationship the researcher has with the data, how it is generated and collected, will determine the value it contributes to the development of the final GT. 6 The significance of this relationship extends into data analysis conducted by the researcher through the various stages of coding.

Coding is an analytical process used to identify concepts, similarities and conceptual reoccurrences in data. Coding is the pivotal link between collecting or generating data and developing a theory that explains the data. Charmaz 10 posits,

codes rely on interaction between researchers and their data. Codes consist of short labels that we construct as we interact with the data. Something kinaesthetic occurs when we are coding; we are mentally and physically active in the process. (p. 5)

In GT, coding can be categorised into iterative phases. Traditional, evolved and constructivist GT genres use different terminology to explain each coding phase ( Table 1 ).

Comparison of coding terminology in traditional, evolved and constructivist grounded theory.

| Grounded theory genre | Coding terminology | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Intermediate | Advanced | |

| Traditional | Open coding | Selective coding | Theoretical coding |

| Evolved | Open coding | Axial coding | Selective coding |

| Constructivist | Initial coding | Focused coding | Theoretical coding |

Adapted from Birks and Mills. 6

Coding terminology in evolved GT refers to open (a procedure for developing categories of information), axial (an advanced procedure for interconnecting the categories) and selective coding (procedure for building a storyline from core codes that connects the categories), producing a discursive set of theoretical propositions. 6 , 12 , 32 Constructivist grounded theorists refer to initial, focused and theoretical coding. 9 Birks and Mills 6 use the terms initial, intermediate and advanced coding that link to low, medium and high-level conceptual analysis and development. The coding terms devised by Birks and Mills 6 were used for Figure 1 ; however, these can be altered to reflect the coding terminology used in the respective GT genres selected by the researcher.

Initial coding

Initial coding of data is the preliminary step in GT data analysis. 6 , 9 The purpose of initial coding is to start the process of fracturing the data to compare incident to incident and to look for similarities and differences in beginning patterns in the data. In initial coding, the researcher inductively generates as many codes as possible from early data. 16 Important words or groups of words are identified and labelled. In GT, codes identify social and psychological processes and actions as opposed to themes. Charmaz 16 emphasises keeping codes as similar to the data as possible and advocates embedding actions in the codes in an iterative coding process. Saldaña 33 agrees that codes that denote action, which he calls process codes, can be used interchangeably with gerunds (verbs ending in ing ). In vivo codes are often verbatim quotes from the participants’ words and are often used as the labels to capture the participant’s words as representative of a broader concept or process in the data. 6 Table 1 reflects variation in the terminology of codes used by grounded theorists.

Initial coding categorises and assigns meaning to the data, comparing incident-to-incident, labelling beginning patterns and beginning to look for comparisons between the codes. During initial coding, it is important to ask ‘what is this data a study of’. 18 What does the data assume, ‘suggest’ or ‘pronounce’ and ‘from whose point of view’ does this data come, whom does it represent or whose thoughts are they?. 16 What collectively might it represent? The process of documenting reactions, emotions and related actions enables researchers to explore, challenge and intensify their sensitivity to the data. 34 Early coding assists the researcher to identify the direction for further data gathering. After initial analysis, theoretical sampling is employed to direct collection of additional data that will inform the ‘developing theory’. 9 Initial coding advances into intermediate coding once categories begin to develop.

Theoretical sampling

The purpose of theoretical sampling is to allow the researcher to follow leads in the data by sampling new participants or material that provides relevant information. As depicted in Figure 1 , theoretical sampling is central to GT design, aids the evolving theory 5 , 7 , 16 and ensures the final developed theory is grounded in the data. 9 Theoretical sampling in GT is for the development of a theoretical category, as opposed to sampling for population representation. 10 Novice researchers need to acknowledge this difference if they are to achieve congruence within the methodology. Birks and Mills 6 define theoretical sampling as ‘the process of identifying and pursuing clues that arise during analysis in a grounded theory study’ (p. 68). During this process, additional information is sought to saturate categories under development. The analysis identifies relationships, highlights gaps in the existing data set and may reveal insight into what is not yet known. The exemplars in Box 1 highlight how theoretical sampling led to the inclusion of further data.

Examples of theoretical sampling.

| In Chamberlain-Salaun GT study, ‘the initial purposive round of concurrent data generation and analysis generated codes around concepts of physical disability and how a person’s health condition influences the way experts interact with consumers. Based on initial codes and concepts the researcher decided to theoretically sample people with disabilities and or carers/parents of children with disabilities to pursue the concepts further’ (p. 77). In Edwards grounded theory study, theoretical sampling led to the inclusion of the partners of women who had presented to the emergency department. ‘In one interview a woman spoke of being aware that the ED staff had not acknowledged her partner. This statement led me to ask other women during their interviews if they had similar experiences, and ultimately to interview the partners to gain their perspectives. The study originally intended to only focus on the women and the nursing staff who provided the care’ (p. 50). |

Thus, theoretical sampling is used to focus and generate data to feed the iterative process of continual comparative analysis of the data. 6

Intermediate coding

Intermediate coding, identifying a core category, theoretical data saturation, constant comparative analysis, theoretical sensitivity and memoing occur in the next phase of the GT process. 6 Intermediate coding builds on the initial coding phase. Where initial coding fractures the data, intermediate coding begins to transform basic data into more abstract concepts allowing the theory to emerge from the data. During this analytic stage, a process of reviewing categories and identifying which ones, if any, can be subsumed beneath other categories occurs and the properties or dimension of the developed categories are refined. Properties refer to the characteristics that are common to all the concepts in the category and dimensions are the variations of a property. 37

At this stage, a core category starts to become evident as developed categories form around a core concept; relationships are identified between categories and the analysis is refined. Birks and Mills 6 affirm that diagramming can aid analysis in the intermediate coding phase. Grounded theorists interact closely with the data during this phase, continually reassessing meaning to ascertain ‘what is really going on’ in the data. 30 Theoretical saturation ensues when new data analysis does not provide additional material to existing theoretical categories, and the categories are sufficiently explained. 6

Advanced coding

Birks and Mills 6 described advanced coding as the ‘techniques used to facilitate integration of the final grounded theory’ (p. 177). These authors promote storyline technique (described in the following section) and theoretical coding as strategies for advancing analysis and theoretical integration. Advanced coding is essential to produce a theory that is grounded in the data and has explanatory power. 6 During the advanced coding phase, concepts that reach the stage of categories will be abstract, representing stories of many, reduced into highly conceptual terms. The findings are presented as a set of interrelated concepts as opposed to presenting themes. 28 Explanatory statements detail the relationships between categories and the central core category. 28

Storyline is a tool that can be used for theoretical integration. Birks and Mills 6 define storyline as ‘a strategy for facilitating integration, construction, formulation, and presentation of research findings through the production of a coherent grounded theory’ (p. 180). Storyline technique is first proposed with limited attention in Basics of Qualitative Research by Strauss and Corbin 12 and further developed by Birks et al. 38 as a tool for theoretical integration. The storyline is the conceptualisation of the core category. 6 This procedure builds a story that connects the categories and produces a discursive set of theoretical propositions. 24 Birks and Mills 6 contend that storyline can be ‘used to produce a comprehensive rendering of your grounded theory’ (p. 118). Birks et al. 38 had earlier concluded, ‘storyline enhances the development, presentation and comprehension of the outcomes of grounded theory research’ (p. 405). Once the storyline is developed, the GT is finalised using theoretical codes that ‘provide a framework for enhancing the explanatory power of the storyline and its potential as theory’. 6 Thus, storyline is the explication of the theory.

Theoretical coding occurs as the final culminating stage towards achieving a GT. 39 , 40 The purpose of theoretical coding is to integrate the substantive theory. 41 Saldaña 40 states, ‘theoretical coding integrates and synthesises the categories derived from coding and analysis to now create a theory’ (p. 224). Initial coding fractures the data while theoretical codes ‘weave the fractured story back together again into an organized whole theory’. 18 Advanced coding that integrates extant theory adds further explanatory power to the findings. 6 The examples in Box 2 describe the use of storyline as a technique.

Writing the storyline.

| Baldwin describes in her GT study how ‘the process of writing the storyline allowed in-depth descriptions of the categories, and discussion of how the categories of (i) , (ii) and (iii) fit together to form the final theory: ’ (pp. 125–126). ‘The use of storyline as part of the finalisation of the theory from the data ensured that the final theory was grounded in the data’ (p. 201). In Chamberlain-Salaun GT study, writing the storyline enabled the identification of ‘gaps in the developing theory and to clarify categories and concepts. To address the gaps the researcher iteratively returned to the data and to the field and refine the storyline. Once the storyline was developed raw data was incorporated to support the story in much the same way as dialogue is included in a storybook or novel’. |

Theoretical sensitivity

As presented in Figure 1 , theoretical sensitivity encompasses the entire research process. Glaser and Strauss 5 initially described the term theoretical sensitivity in The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Theoretical sensitivity is the ability to know when you identify a data segment that is important to your theory. While Strauss and Corbin 12 describe theoretical sensitivity as the insight into what is meaningful and of significance in the data for theory development, Birks and Mills 6 define theoretical sensitivity as ‘the ability to recognise and extract from the data elements that have relevance for the emerging theory’ (p. 181). Conducting GT research requires a balance between keeping an open mind and the ability to identify elements of theoretical significance during data generation and/or collection and data analysis. 6

Several analytic tools and techniques can be used to enhance theoretical sensitivity and increase the grounded theorist’s sensitivity to theoretical constructs in the data. 28 Birks and Mills 6 state, ‘as a grounded theorist becomes immersed in the data, their level of theoretical sensitivity to analytic possibilities will increase’ (p. 12). Developing sensitivity as a grounded theorist and the application of theoretical sensitivity throughout the research process allows the analytical focus to be directed towards theory development and ultimately result in an integrated and abstract GT. 6 The example in Box 3 highlights how analytic tools are employed to increase theoretical sensitivity.

Theoretical sensitivity.

| Hoare et al. described how the lead author ‘ in pursuit of heightened theoretical sensitivity in a grounded theory study of information use by nurses working in general practice in New Zealand’. The article described the analytic tools the researcher used ‘to increase theoretical sensitivity’ which included ‘reading the literature, open coding, category building, reflecting in memos followed by doubling back on data collection once further lines of inquiry are opened up’. The article offers ‘an example of how analytical tools are employed to theoretically sample emerging concepts’ (pp. 240–241). |

The grounded theory

The meticulous application of essential GT methods refines the analysis resulting in the generation of an integrated, comprehensive GT that explains a process relating to a particular phenomenon. 6 The results of a GT study are communicated as a set of concepts, related to each other in an interrelated whole, and expressed in the production of a substantive theory. 5 , 7 , 16 A substantive theory is a theoretical interpretation or explanation of a studied phenomenon 6 , 17 Thus, the hallmark of grounded theory is the generation of theory ‘abstracted from, or grounded in, data generated and collected by the researcher’. 6 However, to ensure quality in research requires the application of rigour throughout the research process.

Quality and rigour

The quality of a grounded theory can be related to three distinct areas underpinned by (1) the researcher’s expertise, knowledge and research skills; (2) methodological congruence with the research question; and (3) procedural precision in the use of methods. 6 Methodological congruence is substantiated when the philosophical position of the researcher is congruent with the research question and the methodological approach selected. 6 Data collection or generation and analytical conceptualisation need to be rigorous throughout the research process to secure excellence in the final grounded theory. 44

Procedural precision requires careful attention to maintaining a detailed audit trail, data management strategies and demonstrable procedural logic recorded using memos. 6 Organisation and management of research data, memos and literature can be assisted using software programs such as NVivo. An audit trail of decision-making, changes in the direction of the research and the rationale for decisions made are essential to ensure rigour in the final grounded theory. 6

This article offers a framework to assist novice researchers visualise the iterative processes that underpin a GT study. The fundamental process and methods used to generate an integrated grounded theory have been described. Novice researchers can adapt the framework presented to inform and guide the design of a GT study. This framework provides a useful guide to visualise the interplay between the methods and processes inherent in conducting GT. Research conducted ethically and with meticulous attention to process will ensure quality research outcomes that have relevance at the practice level.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

- Sign into My Research

- Create My Research Account

- Company Website

- Our Products

- About Dissertations

- Español (España)

- Support Center

Select language

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português (Brasil)

- Português (Portugal)

Welcome to My Research!

You may have access to the free features available through My Research. You can save searches, save documents, create alerts and more. Please log in through your library or institution to check if you have access.

Translate this article into 20 different languages!

If you log in through your library or institution you might have access to this article in multiple languages.

Get access to 20+ different citations styles

Styles include MLA, APA, Chicago and many more. This feature may be available for free if you log in through your library or institution.

Looking for a PDF of this document?

You may have access to it for free by logging in through your library or institution.

Want to save this document?

You may have access to different export options including Google Drive and Microsoft OneDrive and citation management tools like RefWorks and EasyBib. Try logging in through your library or institution to get access to these tools.

- More like this

- Preview Available

- Scholarly Journal

Grounded Theory Methods and Qualitative Family Research

No items selected.

Please select one or more items.

Select results items first to use the cite, email, save, and export options

You might have access to the full article...

Try and log in through your institution to see if they have access to the full text.

Content area

Among the different qualitative approaches that may be relied upon in family theorizing, grounded theory methods (GTM), developed by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss, are the most popular. Despite their centrality to family studies and to other fields, however, GTM can be opaque and confusing. Believing that simplifying GTM would allow them to be used to greater effect, I rely on 5 principles to interpret 3 major phases in GTM coding: open, axial, and selective. The history of GTM establishes a foundation for the interpretation, whereas recognition of the dialectic between induction and deduction underscores the importance of incorporating constructivism in GTM thinking. My goal is to propose a methodologically condensed but still comprehensive interpretation of GTM, an interpretation that researchers hopefully will find easy to understand and employ.

Key Words: content analysis, grounded theoretical analysis, qualitative methods, theory construction.

There is an irony-perhaps a paradox-here: that a methodology that is based on "interpretation" should itself prove so hard to interpret. (Dey, 1999, p. 23)

Beginning in the early 1970s with the creation of the National Council on Family Relations' Theory Construction and Research Methodology Workshop, and continuing through a series of volumes on family theories and methods (Bengtson, Acock, Allen, Dilworth-Anderson, & Klein, 2005a; Boss, Doherty, LaRossa, Schumm, & Steinmetz, 1993; Burr, Hill, Nye, & Reiss, 1979a, 1979b), family studies has become a field where methodologically based theorizing matters. Cognizant of this fact, family scholars place a premium on research techniques that facilitate the development of new ideas.

In quantitative studies, multivariate statistical techniques are essential to the theorizing process. In qualitative studies, any number of approaches may be used to generate theory, but family scholars tend to rely on a multivariate nonstatistical (or quasistatistical) set of procedures, known as grounded theory methods (GTM). GTM were originally devised to facilitate theory construction, and their proponents routinely assert that a GTM approach promotes theorizing in ways that alternative methods do not (see Glaser, 1978, 1992; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss, 1987; Strauss & Corbin, 1990a, 1998).

Besides being drawn to GTM's theory-generating potential, family scholars may be attracted to GTM's compatibility with quantitative research. Unlike some other qualitative approaches, which are expressly descriptive in their intent (e.g., phenomenological analysis), GTM are purposefully explanatory (Baker,...

You have requested "on-the-fly" machine translation of selected content from our databases. This functionality is provided solely for your convenience and is in no way intended to replace human translation. Show full disclaimer

Neither ProQuest nor its licensors make any representations or warranties with respect to the translations. The translations are automatically generated "AS IS" and "AS AVAILABLE" and are not retained in our systems. PROQUEST AND ITS LICENSORS SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION, ANY WARRANTIES FOR AVAILABILITY, ACCURACY, TIMELINESS, COMPLETENESS, NON-INFRINGMENT, MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Your use of the translations is subject to all use restrictions contained in your Electronic Products License Agreement and by using the translation functionality you agree to forgo any and all claims against ProQuest or its licensors for your use of the translation functionality and any output derived there from. Hide full disclaimer

Suggested sources

- About ProQuest

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

Grounded Theory Methodology: Principles and Practices

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 13 January 2019

- Cite this reference work entry

- Linda Liska Belgrave 2 &

- Kapriskie Seide 2

2766 Accesses

22 Citations

Since Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss’ (The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Adline De Gruyter, 1967) publication of their groundbreaking book, The Discovery of Grounded Theory , grounded theory methodology (GTM) has been an integral part of health social science. GTM allows for the systematic collection and analysis of qualitative data to inductively develop middle-range theories to make sense of people’s actions and experiences in the social world. Since its introduction, grounded theorists working from diverse research paradigms have expanded the methodology and developed alternative approaches to GTM. As a result, GTM permeates multiple disciplines and offers a wide diversity of variants in its application. The availability of many options can, at times, lead to confusion and misconceptions, particularly among novice users of the methodology. Consequently, in this book chapter, we aim to acquaint readers with this qualitative methodology. More specifically, we sort through five major developments in GTM and review key elements, from data collection through writing. Finally, we review published research reflecting these methods, to illustrate their application. We also note the value of GTM for elucidating components of culture that might otherwise remain hidden.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Grounded Theory Methods

Ahmad F, Hudak PL, Bercovitz K, Hollenberg E, Levison W. Are physicians ready for patients with internet-based health information? J Med Internet Res. 2006;8(3):e22.

Article Google Scholar

Aita K, Kai I. Physicians’ psychosocial barriers to different modes of withdrawal of life support in critical care: a qualitative study in Japan. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(4):616–22.

Bateman J, Allen M, Samani D, Kidd J, Davies D. Virtual patient design: exploring what works and why. A grounded theory study. Med Educ. 2013;47:595–606.

Beard RL, Fetterman DJ, Wu B, Bryant L. The two voices of Alzheimer’s: attitudes toward brain health by diagnosed individuals and support persons. Gerontologist. 2009;49:S40–9.

Belgrave LL, Seide K. Coding for grounded theory. In: Bryant A, Charmaz K, editors. The SAGE handbook of current developments in grounded theory. London. Forthcoming.

Google Scholar

Brown B. Shame resilience theory: a grounded theory study on women and shame. Fam Soc. 2006;87(1):43–52.

Bryant A. Re-grounding grounded theory. J Inf Technol Theory Appl. 2002;4:25–42.

Bryant A. Grounded theory and grounded theorizing: pragmatism in research practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017.

Book Google Scholar

Bryant A, Charmaz K. Grounded theory in historical perspective: an epistemological account. In: Bryant A, Charmaz K, editors. The handbook of grounded theory. London: Sage; 2007a. p. 31–57.

Chapter Google Scholar

Bryant A, Charmaz K. Introduction. In: Bryant A, Charmaz K, editors. The handbook of grounded theory. London: Sage; 2007b. p. 31–57.

Charmaz K. Body, identity and self: adapting to impairment. Sociol Q. 1995;36:657–80.

Charmaz K. Constructivist and objectivist grounded theory. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln Y, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2000. p. 509–35.

Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage; 2006.

Charmaz K. Constructionism and grounded theory. In: Holstein JA, Gubrium JF, editors. Handbook of constructionist research. New York: Guilford; 2007. p. 35–53.

Charmaz K. Shifting the grounds: constructivist grounded theory methods for the twenty-first century. In: Morse J, Stern P, Corbin J, Bowers B, Charmaz K, Clarke A, editors. Developing grounded theory: the second generation. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press; 2009. p. 127–54.

Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2014.

Charmaz K, Belgrave LL. Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis. In: Gubrium JF, Holstein JA, Marvasti AB, McKinney KD, editors. The sage handbook of interview research: the complexity of the craft. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage; 2012. p. 347–65.

Clarke A. From grounded theory to situational analysis: what’s new? Why? How? In: Morse J, Stern P, Corbin J, Bowers B, Charmaz K, Clarke A, editors. Developing grounded theory: the second generation. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press; 2009. p. 194–233.

Clarke A. Feminisms, grounded theory, and situational analysis revisited. In: Clarke AE, Friese C, Washburn R, editors. Situational analysis in practice: mapping research with grounded theory. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press; 2015. p. 84–154.

Clarke A, Friese C. Grounded theory using situational analysis. In: Bryant A, Charmaz K, editors. The sage handbook of grounded theory. London: Sage; 2007. p. 363–97.

Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 4th ed. Los Angeles: Sage; 2015.

Cresswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2009.

Cresswell JW. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage; 2013.

Cresswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2018.

Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. 4th ed. Los Angeles: Sage; 2018.

Denzin NK, Giardina MD. Qualitative inquiry and social justice: towards a politics of hope. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press; 2009.

Erol M. Melting bones: the social construction of postmenopausal osteoporosis in Turkey. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(10):1490–7.

Fielding N. Analytic density, postmodernism, and applied multiple methods research. In: Bergman MM, editor. Advances in mixed methods research: theories and applications. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2008. p. 37–52.

Glaser BG. Theoretical sensitivity. Mill Valley: The Sociology Press; 1978.

Glaser BG, Strauss AL. Awareness of dying. Chicago: Aldine Pub; 1965.

Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Adline De Gruyter; 1967.

Kononowicz AA, Zary N, Edebring S, Hege I. Virtual patients – what are we talking about? A framework to classify the meanings of the term in healthcare education. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:11.

Larsson IE, Sahlsten MJ, Sjöström B, et al. Patient participation in nursing care from a patient perspective: a grounded theory study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2007;21:313–20.

Liamputtong P. Performing qualitative cross-cultural research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

Liamputtong P. Culture as social determinant of health. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Social determinants of health: individual, community and healthcare. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2018.

Lindsay K, Vanderpyl J, Logo P, Dalbeth N. The experience and impact of living with gout: a study of men with chronic gout using a qualitative grounded theory approach. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:1–6.

Nagel DA, Burns VF, Tilley C, Augin D. When novice researchers adopt constructivist grounded theory: Navigating the less traveled paradigmatic and methodological paths in Ph.D. dissertation work. Int J Doctoral Stud. 2015;10:365–83.

Poteat T, German D, Kerrigan D. Managing uncertainty: a grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2013;84:22–9.

Quah S. Health and culture. In: Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology. 2007. Retrieved from http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/tocnode.html?id=g9781405124331_chunk_g978140512433114_ss1-7 .

Schnitzer G, Loots G, Escudero V, Schechter I. Negotiating the pathways into care in a globalizing world: help-seeking behavior of ultra-orthodox Jewish parents. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57(2):153–65.

Seide K. In the midst of it all: a qualitative study of the everyday life of Haitians during an ongoing cholera epidemic. Unpublished Master’s Thesis. University of Miami; 2016.

Stern PN. On solid ground: essential properties for growing grounded theory. In: Bryant A, Charmaz K, editors. The sage handbook of grounded theory. London: Sage; 2007. p. 114–26.

Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage; 1990.

Ulysse GA. Papa, patriarchy, and power: snapshots of a good Haitian girl, feminism, & diasporic dreams. J Haitian Stud. 2006;12(1):24–47.

Wertz FJ, Charmaz K, McMullen L, Josselson R, Anderson R, McSpadden E. Five ways of doing qualitative analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2011.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Sociology, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USA

Linda Liska Belgrave & Kapriskie Seide

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Linda Liska Belgrave .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Science and Health, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Pranee Liamputtong

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Belgrave, L.L., Seide, K. (2019). Grounded Theory Methodology: Principles and Practices. In: Liamputtong, P. (eds) Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_84

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_84

Published : 13 January 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-10-5250-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-10-5251-4

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Grounded Theory In Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Grounded theory is a useful approach when you want to develop a new theory based on real-world data Instead of starting with a pre-existing theory, grounded theory lets the data guide the development of your theory.

What Is Grounded Theory?

Grounded theory is a qualitative method specifically designed to inductively generate theory from data. It was developed by Glaser and Strauss in 1967.

- Data shapes the theory: Instead of trying to prove an existing theory, you let the data guide your findings.

- No guessing games: You don’t start with assumptions or try to confirm your own biases.

- Data collection and analysis happen together: You analyze information as you gather it, which helps you decide what data to collect next.

It is important to note that grounded theory is an inductive approach where a theory is developed from collected real-world data rather than trying to prove or disprove a hypothesis like in a deductive scientific approach

You gather information, look for patterns, and use those patterns to develop an explanation.

It is a way to understand why people do things and how those actions create patterns. Imagine you’re trying to figure out why your friends love a certain video game.

Instead of asking an adult, you observe your friends while they’re playing, listen to them talk about it, and maybe even play a little yourself. By studying their actions and words, you’re using grounded theory to build an understanding of their behavior.

This qualitative method of research focuses on real-life experiences and observations, letting theories emerge naturally from the data collected, like piecing together a puzzle without knowing the final image.

When should you use grounded theory?

Grounded theory research is useful for beginning researchers, particularly graduate students, because it offers a clear and flexible framework for conducting a study on a new topic.

Grounded theory works best when existing theories are either insufficient or nonexistent for the topic at hand.

Since grounded theory is a continuously evolving process, researchers collect and analyze data until theoretical saturation is reached or no new insights can be gained.

What is the final product of a GT study?

The final product of a grounded theory (GT) study is an integrated and comprehensive grounded theory that explains a process or scheme associated with a phenomenon.

The quality of a GT study is judged on whether it produces this middle-range theory

Middle-range theories are sort of like explanations that focus on a specific part of society or a particular event. They don’t try to explain everything in the world. Instead, they zero in on things happening in certain groups, cultures, or situations.

Think of it like this: a grand theory is like trying to understand all of weather at once, but a middle-range theory is like focusing on how hurricanes form.

Here are a few examples of what middle-range theories might try to explain:

- How people deal with feeling anxious in social situations.

- How people act and interact at work.

- How teachers handle students who are misbehaving in class.

Core Components of Grounded Theory

This terminology reflects the iterative, inductive, and comparative nature of grounded theory, which distinguishes it from other research approaches.

- Theoretical Sampling: The researcher uses theoretical sampling to choose new participants or data sources based on the emerging findings of their study. The goal is to gather data that will help to further develop and refine the emerging categories and theoretical concepts.

- Theoretical Sensitivity: Researchers need to be aware of their preconceptions going into a study and understand how those preconceptions could influence the research. However, it is not possible to completely separate a researcher’s history and experience from the construction of a theory.

- Coding: Coding is the process of analyzing qualitative data (usually text) by assigning labels (codes) to chunks of data that capture their essence or meaning. It allows you to condense, organize and interpret your data.

- Core Category: The core category encapsulates and explains the grounded theory as a whole. Researchers identify a core category to focus on during the later stages of their research.

- Memos: Researchers use memos to record their thoughts and ideas about the data, explore relationships between codes and categories, and document the development of the emerging grounded theory. Memos support the development of theory by tracking emerging themes and patterns.

- Theoretical Saturation: This term refers to the point in a grounded theory study when collecting additional data does not yield any new theoretical insights. The researcher continues the process of collecting and analyzing data until theoretical saturation is reached.

- Constant Comparative Analysis: This method involves the systematic comparison of data points, codes, and categories as they emerge from the research process. Researchers use constant comparison to identify patterns and connections in their data.

Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss first introduced grounded theory in 1967 in their book, The Discovery of Grounded Theory .

Their aim was to create a research method that prioritized real-world data to understand social behavior.

However, their approaches diverged over time, leading to two distinct versions: Glaserian and Straussian grounded theory.

The different versions of grounded theory diverge in their approaches to coding , theory construction, and the use of literature.

All versions of grounded theory share the goal of generating a middle-range theory that explains a social process or phenomenon.

They also emphasize the importance of theoretical sampling , constant comparative analysis , and theoretical saturation in developing a robust theory

Glaserian Grounded Theory

Glaserian grounded theory emphasizes the emergence of theory from data and discourages the use of pre-existing literature.

Glaser believed that adopting a specific philosophical or disciplinary perspective reduces the broader potential of grounded theory.

For Glaser, prior understandings should be based on the general problem area and reading very wide to alert or sensitize one to a wide range of possibilities.

It prioritizes parsimony , scope , and modifiability in the resulting theory

Straussian Grounded Theory

Strauss and Corbin (1990) focused on developing the analytic techniques and providing guidance to novice researchers.

Straussian grounded theory utilizes a more structured approach to coding and analysis and acknowledges the role of the literature in shaping research.

It acknowledges the role of deduction and validation in addition to induction.

Strauss and Corbin also emphasize the use of unstructured interview questions to encourage participants to speak freely

Critics of this approach believe it produced a rigidity never intended for grounded theory.

Constructivist Grounded Theory

This version, primarily associated with Charmaz, recognizes that knowledge is situated, partial, provisional, and socially constructed. It emphasizes abstract and conceptual understandings rather than explanations.

Kathy Charmaz expanded on original versions of GT, emphasizing the researcher’s role in interpreting findings

Constructivist grounded theory acknowledges the researcher’s influence on the research process and the co-creation of knowledge with participants

Situational Analysis

Developed by Clarke, this version builds upon Straussian and Constructivist grounded theory and incorporates postmodern , poststructuralist , and posthumanist perspectives.

Situational analysis incorporates postmodern perspectives and considers the role of nonhuman actors

It introduces the method of mapping to analyze complex situations and emphasizes both human and nonhuman elements .

- Discover New Insights: Grounded theory lets you uncover new theories based on what your data reveals, not just on pre-existing ideas.

- Data-Driven Results: Your conclusions are firmly rooted in the data you’ve gathered, ensuring they reflect reality. This close relationship between data and findings is a key factor in establishing trustworthiness.

- Avoids Bias: Because gathering data and analyzing it are closely intertwined, researchers are truly observing what emerges from data, and are less likely to let their preconceptions color the findings.

- Streamlined data gathering and analysis: Analyzing and collecting data go hand in hand. Data is collected, analyzed, and as you gain insight from analysis, you continue gathering more data.

- Synthesize Findings : By applying grounded theory to a qualitative metasynthesis , researchers can move beyond a simple aggregation of findings and generate a higher-level understanding of the phenomena being studied.

Limitations

- Time-Consuming: Analyzing qualitative data can be like searching for a needle in a haystack; it requires careful examination and can be quite time-consuming, especially without software assistance6.

- Potential for Bias: Despite safeguards, researchers may unintentionally influence their analysis due to personal experiences.

- Data Quality: The success of grounded theory hinges on complete and accurate data; poor quality can lead to faulty conclusions.

Practical Steps

Grounded theory can be conducted by individual researchers or research teams. If working in a team, it’s important to communicate regularly and ensure everyone is using the same coding system.

Grounded theory research is typically an iterative process. This means that researchers may move back and forth between these steps as they collect and analyze data.

Instead of doing everything in order, you repeat the steps over and over.

This cycle keeps going, which is why grounded theory is called a circular process.

Continue to gather and analyze data until no new insights or properties related to your categories emerge. This saturation point signals that the theory is comprehensive and well-substantiated by the data.

Theoretical sampling, collecting sufficient and rich data, and theoretical saturation help the grounded theorist to avoid a lack of “groundedness,” incomplete findings, and “premature closure.

1. Planning and Philosophical Considerations

Begin by considering the phenomenon you want to study and assess the current knowledge surrounding it.

However, refrain from detailing the specific aspects you seek to uncover about the phenomenon to prevent pre-existing assumptions from skewing the research.

- Discern a personal philosophical position. Before beginning a research study, it is important to consider your philosophical stance and how you view the world, including the nature of reality and the relationship between the researcher and the participant. This will inform the methodological choices made throughout the study.

- Investigate methodological possibilities. Explore different research methods that align with both the philosophical stance and research goals of the study.

- Plan the study. Determine the research question, how to collect data, and from whom to collect data.

- Conduct a literature review. The literature review is an ongoing process throughout the study. It is important to avoid duplicating existing research and to consider previous studies, concepts, and interpretations that relate to the emerging codes and categories in the developing grounded theory.

2. Recruit participants using theoretical sampling

Initially, select participants who are readily available ( convenience sampling ) or those recommended by existing participants ( snowball sampling ).

As the analysis progresses, transition to theoretical sampling , involving the deliberate selection of participants and data sources to refine your emerging theory.

This method is used to refine and develop a grounded theory. The researcher uses theoretical sampling to choose new participants or data sources based on the emerging findings of their study.

This could mean recruiting participants who can shed light on gaps in your understanding uncovered during the initial data analysis.

Theoretical sampling guides further data collection by identifying participants or data sources that can provide insights into gaps in the emerging theory

The goal is to gather data that will help to further develop and refine the emerging categories and theoretical concepts.

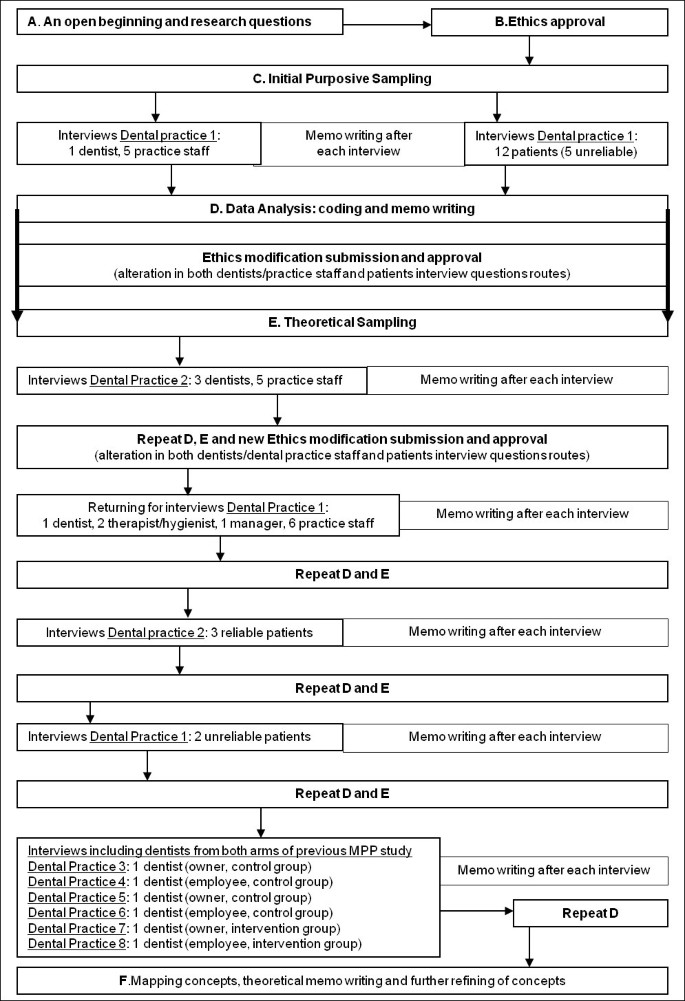

Theoretical sampling starts early in a GT study and generally requires the researcher to make amendments to their ethics approvals to accommodate new participant groups.

3. Collect Data

The researcher might use interviews, focus groups, observations, or a combination of methods to collect qualitative data.

- Observations : Watching and recording phenomena as they occur. Can be participant (researcher actively involved) or non-participant (researcher tries not to influence behaviors), and covert (participants unaware) or overt (participants aware).

- Interviews : One-on-one conversations to understand participants’ experiences. Can be structured (predetermined questions), informal (casual conversations), or semi-structured (flexible structure to explore emerging issues).

- Focus groups : Dynamic discussions with 4-10 participants sharing characteristics, moderated by the researcher using a topic guide.

- Ethnography : Studying a group’s behaviors and social interactions in their environment through observations, field notes, and interviews. Researchers immerse themselves in the community or organization for an in-depth understanding.

4. Begin open coding as soon as data collection starts

Open coding is the first stage of coding in grounded theory, where you carefully examine and label segments of your data to identify initial concepts and ideas.

This process involves scrutinizing the data and creating codes grounded in the data itself.

The initial codes stay close to the data, aiming to capture and summarize critically and analytically what is happening in the data

To begin open coding, read through your data, such as interview transcripts, to gain a comprehensive understanding of what is being conveyed.

As you encounter segments of data that represent a distinct idea, concept, or action, you assign a code to that segment. These codes act as descriptive labels summarizing the meaning of the data segment.

For instance, if you were analyzing interview data about experiences with a new medication, a segment of data might describe a participant’s difficulty sleeping after taking the medication. This segment could be labeled with the code “trouble sleeping”

Open coding is a crucial step in grounded theory because it allows you to break down the data into manageable units and begin to see patterns and themes emerge.

As you continue coding, you constantly compare different segments of data to refine your understanding of existing codes and identify new ones.

For instance, excerpts describing difficulties with sleep might be grouped under the code “trouble sleeping”.

This iterative process of comparing data and refining codes helps ensure the codes accurately reflect the data.

Open coding is about staying close to the data, using in vivo terms or gerunds to maintain a sense of action and process

5. Reflect on thoughts and contradictions by writing grounded theory memos during analysis

During open coding, it’s crucial to engage in memo writing. Memos serve as your “notes to self”, allowing you to reflect on the coding process, note emerging patterns, and ask analytical questions about the data.

Document your thoughts, questions, and insights in memos throughout the research process.

These memos serve multiple purposes: tracing your thought process, promoting reflexivity (self-reflection), facilitating collaboration if working in a team, and supporting theory development.

Early memos tend to be shorter and less conceptual, often serving as “preparatory” notes. Later memos become more analytical and conceptual as the research progresses.

Memo Writing

- Reflexivity and Recognizing Assumptions: Researchers should acknowledge the influence of their own experiences and assumptions on the research process. Articulating these assumptions, perhaps through memos, can enhance the transparency and trustworthiness of the study.

- Write memos throughout the research process. Memo writing should occur throughout the entire research process, beginning with initial coding.67 Memos help make sense of the data and transition between coding phases.8

- Ask analytic questions in early memos. Memos should include questions, reflections, and notes to explore in subsequent data collection and analysis.8

- Refine memos throughout the process. Early memos will be shorter and less conceptual, but will become longer and more developed in later stages of the research process.7 Later memos should begin to develop provisional categories.

6. Group codes into categories using axial coding

Axial coding is the process of identifying connections between codes, grouping them together into categories to reveal relationships within the data.

Axial coding seeks to find the axes that connect various codes together.

For example, in research on school bullying, focused codes such as “Doubting oneself, getting low self-confidence, starting to agree with bullies” and “Getting lower self-confidence; blaming oneself” could be grouped together into a broader category representing the impact of bullying on self-perception.

Similarly, codes such as “Being left by friends” and “Avoiding school; feeling lonely and isolated” could be grouped into a category related to the social consequences of bullying.

These categories then become part of the emerging grounded theory, explaining the multifaceted aspects of the phenomenon.

Qualitative data analysis software often represents these categories as nested codes, visually demonstrating the hierarchy and interconnectedness of the concepts.

This hierarchical structure helps researchers organize their data, identify patterns, and develop a more nuanced understanding of the relationships between different aspects of the phenomenon being studied.

This process of axial coding is crucial for moving beyond descriptive accounts of the data towards a more theoretically rich and explanatory grounded theory.

7. Define the core category using selective coding

During selective coding , the final development stage of grounded theory analysis, a researcher focuses on developing a detailed and integrated theory by selecting a core category and connecting it to other categories developed during earlier coding stages.

The core category is the central concept that links together the various categories and subcategories identified in the data and forms the foundation of the emergent grounded theory.

This core category will encapsulate the main theme of your grounded theory, that encompasses and elucidates the overarching process or phenomenon under investigation.

This phase involves a concentrated effort to refine and integrate categories, ensuring they align with the core category and contribute to the overall explanatory power of the theory.

The theory should comprehensively describe the process or scheme related to the phenomenon being studied.

For example, in a study on school bullying, if the core category is “victimization journey,” the researcher would selectively code data related to different stages of this journey, the factors contributing to each stage, and the consequences of experiencing these stages.

This might involve analyzing how victims initially attribute blame, their coping mechanisms, and the long-term impact of bullying on their self-perception.

Continue collecting data and analyzing until you reach theoretical saturation

Selective coding focuses on developing and saturating this core category, leading to a cohesive and integrated theory.

Through selective coding, researchers aim to achieve theoretical saturation, meaning no new properties or insights emerge from further data analysis.

This signifies that the core category and its related categories are well-defined, and the connections between them are thoroughly explored.

This rigorous process strengthens the trustworthiness of the findings by ensuring the theory is comprehensive and grounded in a rich dataset.

It’s important to note that while a grounded theory seeks to provide a comprehensive explanation, it remains grounded in the data.

The theory’s scope is limited to the specific phenomenon and context studied, and the researcher acknowledges that new data or perspectives might lead to modifications or refinements of the theory

- Constant Comparative Analysis: This method involves the systematic comparison of data points, codes, and categories as they emerge from the research process. Researchers use constant comparison to identify patterns and connections in their data. There are different methods for comparing excerpts from interviews, for example, a researcher can compare excerpts from the same person, or excerpts from different people. This process is ongoing and iterative, and it continues until the researcher has developed a comprehensive and well-supported grounded theory.

- Continue until reaching theoretical saturation : Continue to gather and analyze data until no new insights or properties related to your categories. This saturation point signals that the theory is comprehensive and well-substantiated by the data.

8. Theoretical coding and model development

Theoretical coding is a process in grounded theory where researchers use advanced abstractions, often from existing theories, to explain the relationships found in their data.

Theoretical coding often occurs later in the research process and involves using existing theories to explain the connections between codes and categories.

This process helps to strengthen the explanatory power of the grounded theory. Theoretical coding should not be confused with simply describing the data; instead, it aims to explain the phenomenon being studied, distinguishing grounded theory from purely descriptive research.

Using the developed codes, categories, and core category, create a model illustrating the process or phenomenon.

Here is some advice for novice researchers on how to apply theoretical coding:

- Begin with data analysis: Don’t start with a pre-determined theory. Instead, allow the theory to emerge from your data through careful analysis and coding.

- Use existing theories as a guide: While the theory should primarily emerge from your data, you can use existing theories from any discipline to help explain the connections you are seeing between your categories. This demonstrates how your research builds on established knowledge.

- Use Glaser’s coding families: Consider applying Glaser’s (1978) coding families in the later stages of analysis as a simple way to begin theoretical coding. Remember that your analysis should guide which theoretical codes are most appropriate.

- Keep it simple: Theoretical coding doesn’t need to be overly complex. Focus on finding an existing theory that effectively explains the relationships you have identified in your data.

- Be transparent: Clearly articulate the existing theory you are using and how it explains the connections between your categories.

- Theoretical coding is an iterative process : Remain open to revising your chosen theoretical codes as your analysis deepens and your grounded theory evolves.

9. Write your grounded theory

Present your findings in a clear and accessible manner, ensuring the theory is rooted in the data and explains the relationships between the identified concepts and categories.

The end product of this process is a well-defined, integrated grounded theory that explains a process or scheme related to the phenomenon studied.

- Develop a dissemination plan : Determine how to share the research findings with others.

- Evaluate and implement : Reflect on the research process and quality of findings, then share findings with relevant audiences in service of making a difference in the world

Reading List

Grounded Theory Review : This is an international journal that publishes articles on grounded theory.

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide . Sage.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13, 3-21.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A practical guide through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

- Clarke, A. E. (2003). Situational analyses: Grounded theory mapping after the postmodern turn . Symbolic interaction , 26 (4), 553-576.

- Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity . University of California.

- Glaser, B. G. (2005). The grounded theory perspective III: Theoretical coding . Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B. G., & Holton, J. (2004, May). Remodeling grounded theory. In Forum qualitative sozialforschung/forum: qualitative social research (Vol. 5, No. 2).

- Charmaz, K. (2012). The power and potential of grounded theory. Medical sociology online , 6 (3), 2-15.

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1965). Awareness of dying. New Brunswick. NJ: Aldine. This was the first published grounded theory study

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Routledge.

- Pidgeon, N., & Henwood, K. (1997). Using grounded theory in psychological research. In N. Hayes (Ed.), Doing qualitative analysis in psychology Press/Erlbaum (UK) Taylor & Francis.

Grounded Theory Methods and Qualitative Family Research

RALPH LAROSSA Georgia State University