Click here to search FAQs

- History of the College

- Purpose and Mandate

- Centering Equity

- Act and Regulations

- By-laws and Policies

- Council and Committees

- Annual Reports

- News Centre

- Fair Registration Practices Report

- Executive Leadership Team

- Career Opportunities

- Accessibility

- About RECEs

- Public Register

- Professional Regulation

- Code and Standards

- Unregulated Persons

- Approval of Education Programs

- CPL Program

- Standards in Practice

- Sexual Abuse Prevention Program

- New Member Resources

- Wellness Resources

- Annual Meeting of Members

- Beyond the College

- Apply to the College

- Who Is Required to Be a Member?

- Requirements and FAQs for Registration

- Education Programs

- Request for Review by the Registration Appeals Committee FAQs

- Individual Assessment of Educational Qualifications

Case Studies and Scenarios

Case studies.

Each case study describes the real experience of a Registered Early Childhood Educator. Each one profiles a professional dilemma, incorporates participants with multiple perspectives and explores ethical complexities. Case studies may be used as a source for reflection and dialogue about RECE practice within the framework of the Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice.

Scenarios are snapshots of experiences in the professional practice of a Registered Early Childhood Educator. Each scenario includes a series of questions meant to help RECEs reflect on the situation.

Case Study 1: Sara’s Confusing Behaviour

Case study 2: getting bumps and taking lumps, case study 3: no qualified staff, case study 4: denton’s birthday cupcakes, case study 5: new kid on the block, case study 6: new responsibilities and challenges, case study 7: valuing inclusivity and privacy, case study 8: balancing supervisory responsibilities, case study 9: once we were friends, scenarios, communication and collaboration.

Barbara, an RECE, is working as a supply staff at various centres across the city. During her week at a centre where she helps out in two different rooms each day, she finds that her experience in the school-age program isn’t as straightforward as when she was in the toddler room. Barbara feels completely lost in this program.

Do You Really Know Who Your Friends Are?

Joe is an RECE at an elementary school and works with children between the ages of nine and 12 years old. One afternoon, he finds a group of children huddled around the computer giggling and whispering. Joe quickly discovers they’re going through his party photos on Facebook as one of the children’s parents recently added him as a friend.

Conflicting Approaches

Amina, an experienced RECE, has recently started a new position with a child care centre. She’s assigned to work in the infant room with two colleagues who have worked in the room together for ten years. As Amina settles into her new role, she is taken aback by some of the child care approaches taken by her colleagues.

What to do about Lisa?

Shane, an experienced supervisor at a child care centre, receives a complaint about an RECE who had roughly handled a child earlier that day. The interaction had been witnessed by a parent who confronted the RECE. After some words were exchanged, the RECE left in tears.

Duty to Report

Zoë works as an RECE in a drop-in program at a family support centre. She has a great rapport for a family over a 10-month period and beings to notice a change in the mom and child. One day, as the child is getting dressed to go home for the day, she notices something alarming and brings it to the attention of her supervisor.

Posting on Social Media

Allie, an RECE who has worked at the same child care centre for the last three years, recently started a private social media group to collaborate and discuss programming ideas. As the group takes a negative turn with rude and offensive comments, it’s brought to her supervisor’s attention.

Early Childhood Education: How to do a Child Case Study-Best Practice

- Creating an Annotated Bibliography

- Lesson Plans and Rubrics

- Children's literature

- Podcasts and Videos

- Cherie's Recommended Library

- Great Educational Articles

- Great Activities for Children

- Professionalism in the Field and in a College Classroom

- Professional Associations

- Pennsylvania Certification

- Manor's Early Childhood Faculty

- Manor Lesson Plan Format

- Manor APA Formatting, Reference, and Citation Policy for Education Classes

- Conducting a Literature Review for a Manor education class

- Manor College's Guide to Using EBSCO Effectively

- How to do a Child Case Study-Best Practice

- ED105: From Teacher Interview to Final Project

- Pennsylvania Initiatives

Description of Assignment

During your time at Manor, you will need to conduct a child case study. To do well, you will need to plan ahead and keep a schedule for observing the child. A case study at Manor typically includes the following components:

- Three observations of the child: one qualitative, one quantitative, and one of your choice.

- Three artifact collections and review: one qualitative, one quantitative, and one of your choice.

- A Narrative

Within this tab, we will discuss how to complete all portions of the case study. A copy of the rubric for the assignment is attached.

- Case Study Rubric (Online)

- Case Study Rubric (Hybrid/F2F)

Qualitative and Quantitative Observation Tips

Remember your observation notes should provide the following detailed information about the child:

- child’s age,

- physical appearance,

- the setting, and

- any other important background information.

You should observe the child a minimum of 5 hours. Make sure you DO NOT use the child's real name in your observations. Always use a pseudo name for course assignments.

You will use your observations to help write your narrative. When submitting your observations for the course please make sure they are typed so that they are legible for your instructor. This will help them provide feedback to you.

Qualitative Observations

A qualitative observation is one in which you simply write down what you see using the anecdotal note format listed below.

Quantitative Observations

A quantitative observation is one in which you will use some type of checklist to assess a child's skills. This can be a checklist that you create and/or one that you find on the web. A great choice of a checklist would be an Ounce Assessment and/or work sampling assessment depending on the age of the child. Below you will find some resources on finding checklists for this portion of the case study. If you are interested in using Ounce or Work Sampling, please see your program director for a copy.

Remaining Objective

For both qualitative and quantitative observations, you will only write down what your see and hear. Do not interpret your observation notes. Remain objective versus being subjective.

An example of an objective statement would be the following: "Johnny stacked three blocks vertically on top of a classroom table." or "When prompted by his teacher Johnny wrote his name but omitted the two N's in his name."

An example of a subjective statement would be the following: "Johnny is happy because he was able to play with the block." or "Johnny omitted the two N's in his name on purpose."

- Anecdotal Notes Form Form to use to record your observations.

- Guidelines for Writing Your Observations

- Tips for Writing Objective Observations

- Objective vs. Subjective

Qualitative and Quantitative Artifact Collection and Review Tips

For this section, you will collect artifacts from and/or on the child during the time you observe the child. Here is a list of the different types of artifacts you might collect:

Potential Qualitative Artifacts

- Photos of a child completing a task, during free play, and/or outdoors.

- Samples of Artwork

- Samples of writing

- Products of child-led activities

Potential Quantitative Artifacts

- Checklist

- Rating Scales

- Product Teacher-led activities

Examples of Components of the Case Study

Here you will find a number of examples of components of the Case Study. Please use them as a guide as best practice for completing your Case Study assignment.

- Qualitatitive Example 1

- Qualitatitive Example 2

- Quantitative Photo 1

- Qualitatitive Photo 1

- Quantitative Observation Example 1

- Artifact Photo 1

- Artifact Photo 2

- Artifact Photo 3

- Artifact Photo 4

- Artifact Sample Write-Up

- Case Study Narrative Example Although we do not expect you to have this many pages for your case study, pay close attention to how this case study is organized and written. The is an example of best practice.

Narrative Tips

The Narrative portion of your case study assignment should be written in APA style, double-spaced, and follow the format below:

- Introduction : Background information about the child (if any is known), setting, age, physical appearance, and other relevant details. There should be an overall feel for what this child and his/her family is like. Remember that the child’s neighborhood, school, community, etc all play a role in development, so make sure you accurately and fully describe this setting! --- 1 page

- Observations of Development : The main body of your observations coupled with course material supporting whether or not the observed behavior was typical of the child’s age or not. Report behaviors and statements from both the child observation and from the parent/guardian interview— 1.5 pages

- Comment on Development: This is the portion of the paper where your professional analysis of your observations are shared. Based on your evidence, what can you generally state regarding the cognitive, social and emotional, and physical development of this child? Include both information from your observations and from your interview— 1.5 pages

- Conclusion: What are the relative strengths and weaknesses of the family, the child? What could this child benefit from? Make any final remarks regarding the child’s overall development in this section.— 1page

- Your Case Study Narrative should be a minimum of 5 pages.

Make sure to NOT to use the child’s real name in the Narrative Report. You should make reference to course material, information from your textbook, and class supplemental materials throughout the paper .

Same rules apply in terms of writing in objective language and only using subjective minimally. REMEMBER to CHECK your grammar, spelling, and APA formatting before submitting to your instructor. It is imperative that you review the rubric of this assignment as well before completing it.

Biggest Mistakes Students Make on this Assignment

Here is a list of the biggest mistakes that students make on this assignment:

- Failing to start early . The case study assignment is one that you will submit in parts throughout the semester. It is important that you begin your observations on the case study before the first assignment is due. Waiting to the last minute will lead to a poor grade on this assignment, which historically has been the case for students who have completed this assignment.

- Failing to utilize the rubrics. The rubrics provide students with guidelines on what components are necessary for the assignment. Often students will lose points because they simply read the descriptions of the assignment but did not pay attention to rubric portions of the assignment.

- Failing to use APA formatting and proper grammar and spelling. It is imperative that you use spell check and/or other grammar checking software to ensure that your narrative is written well. Remember it must be in APA formatting so make sure that you review the tutorials available for you on our Lib Guide that will assess you in this area.

- << Previous: Manor College's Guide to Using EBSCO Effectively

- Next: ED105: From Teacher Interview to Final Project >>

- Last Updated: Jul 5, 2024 9:53 AM

- URL: https://manor.libguides.com/earlychildhoodeducation

Manor College Library

700 fox chase road, jenkintown, pa 19046, (215) 885-5752, ©2017 manor college. all rights reserved..

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 11 September 2017

A case of a four-year-old child adopted at eight months with unusual mood patterns and significant polypharmacy

- Magdalena Romanowicz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4916-0625 1 ,

- Alastair J. McKean 1 &

- Jennifer Vande Voort 1

BMC Psychiatry volume 17 , Article number: 330 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

44k Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Long-term effects of neglect in early life are still widely unknown. Diversity of outcomes can be explained by differences in genetic risk, epigenetics, prenatal factors, exposure to stress and/or substances, and parent-child interactions. Very common sub-threshold presentations of children with history of early trauma are challenging not only to diagnose but also in treatment.

Case presentation

A Caucasian 4-year-old, adopted at 8 months, male patient with early history of neglect presented to pediatrician with symptoms of behavioral dyscontrol, emotional dysregulation, anxiety, hyperactivity and inattention, obsessions with food, and attachment issues. He was subsequently seen by two different child psychiatrists. Pharmacotherapy treatment attempted included guanfacine, fluoxetine and amphetamine salts as well as quetiapine, aripiprazole and thioridazine without much improvement. Risperidone initiated by primary care seemed to help with his symptoms of dyscontrol initially but later the dose had to be escalated to 6 mg total for the same result. After an episode of significant aggression, the patient was admitted to inpatient child psychiatric unit for stabilization and taper of the medicine.

Conclusions

The case illustrates difficulties in management of children with early history of neglect. A particular danger in this patient population is polypharmacy, which is often used to manage transdiagnostic symptoms that significantly impacts functioning with long term consequences.

Peer Review reports

There is a paucity of studies that address long-term effects of deprivation, trauma and neglect in early life, with what little data is available coming from institutionalized children [ 1 ]. Rutter [ 2 ], who studied formerly-institutionalized Romanian children adopted into UK families, found that this group exhibited prominent attachment disturbances, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), quasi-autistic features and cognitive delays. Interestingly, no other increases in psychopathology were noted [ 2 ].

Even more challenging to properly diagnose and treat are so called sub-threshold presentations of children with histories of early trauma [ 3 ]. Pincus, McQueen, & Elinson [ 4 ] described a group of children who presented with a combination of co-morbid symptoms of various diagnoses such as conduct disorder, ADHD, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety. As per Shankman et al. [ 5 ], these patients may escalate to fulfill the criteria for these disorders. The lack of proper diagnosis imposes significant challenges in terms of management [ 3 ].

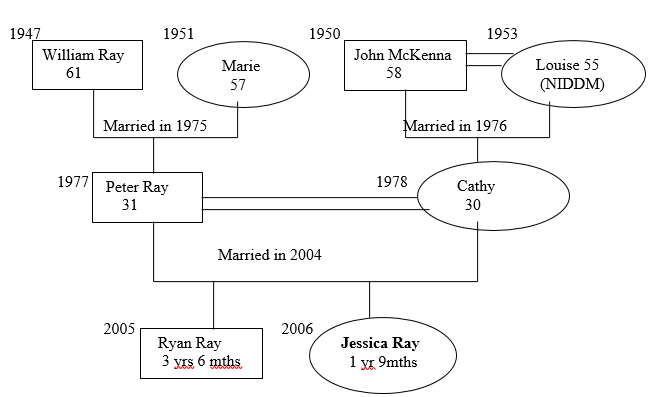

J is a 4-year-old adopted Caucasian male who at the age of 2 years and 4 months was brought by his adoptive mother to primary care with symptoms of behavioral dyscontrol, emotional dysregulation, anxiety, hyperactivity and inattention, obsessions with food, and attachment issues. J was given diagnoses of reactive attachment disorder (RAD) and ADHD. No medications were recommended at that time and a referral was made for behavioral therapy.

She subsequently took him to two different child psychiatrists who diagnosed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD), PTSD, anxiety and a mood disorder. To help with mood and inattention symptoms, guanfacine, fluoxetine, methylphenidate and amphetamine salts were all prescribed without significant improvement. Later quetiapine, aripiprazole and thioridazine were tried consecutively without behavioral improvement (please see Table 1 for details).

No significant drug/substance interactions were noted (Table 1 ). There were no concerns regarding adherence and serum drug concentrations were not ordered. On review of patient’s history of medication trials guanfacine and methylphenidate seemed to have no effect on J’s hyperactive and impulsive behavior as well as his lack of focus. Amphetamine salts that were initiated during hospitalization were stopped by the patient’s mother due to significant increase in aggressive behaviors and irritability. Aripiprazole was tried for a brief period of time and seemed to have no effect. Quetiapine was initially helpful at 150 mg (50 mg three times a day), unfortunately its effects wore off quickly and increase in dose to 300 mg (100 mg three times a day) did not seem to make a difference. Fluoxetine that was tried for anxiety did not seem to improve the behaviors and was stopped after less than a month on mother’s request.

J’s condition continued to deteriorate and his primary care provider started risperidone. While initially helpful, escalating doses were required until he was on 6 mg daily. In spite of this treatment, J attempted to stab a girl at preschool with scissors necessitating emergent evaluation, whereupon he was admitted to inpatient care for safety and observation. Risperidone was discontinued and J was referred to outpatient psychiatry for continuing medical monitoring and therapy.

Little is known about J’s early history. There is suspicion that his mother was neglectful with feeding and frequently left him crying, unattended or with strangers. He was taken away from his mother’s care at 7 months due to neglect and placed with his aunt. After 1 month, his aunt declined to collect him from daycare, deciding she was unable to manage him. The owner of the daycare called Child Services and offered to care for J, eventually becoming his present adoptive parent.

J was a very needy baby who would wake screaming and was hard to console. More recently he wakes in the mornings anxious and agitated. He is often indiscriminate and inappropriate interpersonally, unable to play with other children. When in significant distress he regresses, and behaves as a cat, meowing and scratching the floor. Though J bonded with his adoptive mother well and was able to express affection towards her, his affection is frequently indiscriminate and he rarely shows any signs of separation anxiety.

At the age of 2 years and 8 months there was a suspicion for speech delay and J was evaluated by a speech pathologist who concluded that J was exhibiting speech and language skills that were solidly in the average range for age, with developmental speech errors that should be monitored over time. They did not think that issues with communication contributed significantly to his behavioral difficulties. Assessment of intellectual functioning was performed at the age of 2 years and 5 months by a special education teacher. Based on Bailey Infant and Toddler Development Scale, fine and gross motor, cognitive and social communication were all within normal range.

J’s adoptive mother and in-home therapist expressed significant concerns in regards to his appetite. She reports that J’s biological father would come and visit him infrequently, but always with food and sweets. J often eats to the point of throwing up and there have been occasions where he has eaten his own vomit and dog feces. Mother noticed there is an association between his mood and eating behaviors. J’s episodes of insatiable and indiscriminate hunger frequently co-occur with increased energy, diminished need for sleep, and increased speech. This typically lasts a few days to a week and is followed by a period of reduced appetite, low energy, hypersomnia, tearfulness, sadness, rocking behavior and slurred speech. Those episodes last for one to 3 days. Additionally, there are times when his symptomatology seems to be more manageable with fewer outbursts and less difficulty regarding food behaviors.

J’s family history is poorly understood, with his biological mother having a personality disorder and ADHD, and a biological father with substance abuse. Both maternally and paternally there is concern for bipolar disorder.

J has a clear history of disrupted attachment. He is somewhat indiscriminate in his relationship to strangers and struggles with impulsivity, aggression, sleep and feeding issues. In addition to early life neglect and possible trauma, J has a strong family history of psychiatric illness. His mood, anxiety and sleep issues might suggest underlying PTSD. His prominent hyperactivity could be due to trauma or related to ADHD. With his history of neglect, indiscrimination towards strangers, mood liability, attention difficulties, and heightened emotional state, the possibility of Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder (DSED) is likely. J’s prominent mood lability, irritability and family history of bipolar disorder, are concerning for what future mood diagnosis this portends.

As evidenced above, J presents as a diagnostic conundrum suffering from a combination of transdiagnostic symptoms that broadly impact his functioning. Unfortunately, although various diagnoses such as ADHD, PTSD, Depression, DMDD or DSED may be entertained, the patient does not fall neatly into any of the categories.

This is a case report that describes a diagnostic conundrum in a young boy with prominent early life deprivation who presented with multidimensional symptoms managed with polypharmacy.

A sub-threshold presentation in this patient partially explains difficulties with diagnosis. There is no doubt that negative effects of early childhood deprivation had significant impact on developmental outcomes in this patient, but the mechanisms that could explain the associations are still widely unknown. Significant family history of mental illness also predisposes him to early challenges. The clinical picture is further complicated by the potential dynamic factors that could explain some of the patient’s behaviors. Careful examination of J’s early life history would suggest such a pattern of being able to engage with his biological caregivers, being given food, being tended to; followed by periods of neglect where he would withdraw, regress and engage in rocking as a self-soothing behavior. His adoptive mother observed that visitations with his biological father were accompanied by being given a lot of food. It is also possible that when he was under the care of his biological mother, he was either attended to with access to food or neglected, left hungry and screaming for hours.

The current healthcare model, being centered on obtaining accurate diagnosis, poses difficulties for treatment in these patients. Given the complicated transdiagnostic symptomatology, clear guidelines surrounding treatment are unavailable. To date, there have been no psychopharmacological intervention trials for attachment issues. In patients with disordered attachment, pharmacologic treatment is typically focused on co-morbid disorders, even with sub-threshold presentations, with the goal of symptom reduction [ 6 ]. A study by dosReis [ 7 ] found that psychotropic usage in community foster care patients ranged from 14% to 30%, going to 67% in therapeutic foster care and as high as 77% in group homes. Another study by Breland-Noble [ 8 ] showed that many children receive more than one psychotropic medication, with 22% using two medications from the same class.

It is important to note that our patient received four different neuroleptic medications (quetiapine, aripiprazole, risperidone and thioridazine) for disruptive behaviors and impulsivity at a very young age. Olfson et al. [ 9 ] noted that between 1999 and 2007 there has been a significant increase in the use of neuroleptics for very young children who present with difficult behaviors. A preliminary study by Ercan et al. [ 10 ] showed promising results with the use of risperidone in preschool children with behavioral dyscontrol. Review by Memarzia et al. [ 11 ] suggested that risperidone decreased behavioral problems and improved cognitive-motor functions in preschoolers. The study also raised concerns in regards to side effects from neuroleptic medications in such a vulnerable patient population. Younger children seemed to be much more susceptible to side effects in comparison to older children and adults with weight gain being the most common. Weight gain associated with risperidone was most pronounced in pre-adolescents (Safer) [ 12 ]. Quetiapine and aripiprazole were also associated with higher rates of weight gain (Correll et al.) [ 13 ].

Pharmacokinetics of medications is difficult to assess in very young children with ongoing development of the liver and the kidneys. It has been observed that psychotropic medications in children have shorter half-lives (Kearns et al.) [ 14 ], which would require use of higher doses for body weight in comparison to adults for same plasma level. Unfortunately, that in turn significantly increases the likelihood and severity of potential side effects.

There is also a question on effects of early exposure to antipsychotics on neurodevelopment. In particular in the first 3 years of life there are many changes in developing brains, such as increase in synaptic density, pruning and increase in neuronal myelination to list just a few [ 11 ]. Unfortunately at this point in time there is a significant paucity of data that would allow drawing any conclusions.

Our case report presents a preschool patient with history of adoption, early life abuse and neglect who exhibited significant behavioral challenges and was treated with various psychotropic medications with limited results. It is important to emphasize that subthreshold presentation and poor diagnostic clarity leads to dangerous and excessive medication regimens that, as evidenced above is fairly common in this patient population.

Neglect and/or abuse experienced early in life is a risk factor for mental health problems even after adoption. Differences in genetic risk, epigenetics, prenatal factors (e.g., malnutrition or poor nutrition), exposure to stress and/or substances, and parent-child interactions may explain the diversity of outcomes among these individuals, both in terms of mood and behavioral patterns [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Considering that these children often present with significant functional impairment and a wide variety of symptoms, further studies are needed regarding diagnosis and treatment.

Abbreviations

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder

Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Reactive Attachment disorder

Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):e1001349. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349 . Epub 2012 Nov 27

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kreppner JM, O'Connor TG, Rutter M, English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team. Can inattention/overactivity be an institutional deprivation syndrome? J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2001;29(6):513–28. PMID: 11761285

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dejong M. Some reflections on the use of psychiatric diagnosis in the looked after or “in care” child population. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;15(4):589–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104510377705 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pincus HA, McQueen LE, Elinson L. Subthreshold mental disorders: Nosological and research recommendations. In: Phillips KA, First MB, Pincus HA, editors. Advancing DSM: dilemmas in psychiatric diagnosis. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2003. p. 129–44.

Google Scholar

Shankman SA, Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Small JW, Seeley JR, Altman SE. Subthreshold conditions as precursors for full syndrome disorders: a 15-year longitudinal study of multiple diagnostic classes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:1485–94.

AACAP. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with reactive attachment disorder of infancy and early childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:1206–18.

Article Google Scholar

dosReis S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, Soeken KL. Mental health services for youths in foster care and disabled youths. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(7):1094–9.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Breland-Noble AM, Elbogen EB, Farmer EMZ, Wagner HR, Burns BJ. Use of psychotropic medications by youths in therapeutic foster care and group homes. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(6):706–8.

Olfson M, Crystal S, Huang C. Trends in antipsychotic drug use by very young, privately insured children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:13–23.

PubMed Google Scholar

Ercan ES, Basay BK, Basay O. Risperidone in the treatment of conduct disorder in preschool children without intellectual disability. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2011;5:10.

Memarzia J, Tracy D, Giaroli G. The use of antipsychotics in preschoolers: a veto or a sensible last option? J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(4):303–19.

Safer DJ. A comparison of risperidone-induced weight gain across the age span. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:429–36.

Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2009;302:1765–73.

Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM, Alander SW. Developmental pharmacology – drug disposition, action, and therapy in infants and children. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1157–67.

Monk C, Spicer J, Champagne FA. Linking prenatal maternal adversity to developmental outcomes in infants: the role of epigenetic pathways. Dev Psychopathol. 2012;24(4):1361–76. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000764 . Review. PMID: 23062303

Cecil CA, Viding E, Fearon P, Glaser D, McCrory EJ. Disentangling the mental health impact of childhood abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;63:106–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.024 . [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 27914236

Nemeroff CB. Paradise lost: the neurobiological and clinical consequences of child abuse and neglect. Neuron. 2016;89(5):892–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.019 . Review. PMID: 26938439

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are also grateful to patient’s legal guardian for their support in writing this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Mayo Clinic, Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, 200 1st SW, Rochester, MN, 55901, USA

Magdalena Romanowicz, Alastair J. McKean & Jennifer Vande Voort

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MR, AJM, JVV conceptualized and followed up the patient. MR, AJM, JVV did literature survey and wrote the report and took part in the scientific discussion and in finalizing the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final document.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Magdalena Romanowicz .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication.

Written consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardian for publication of the patient’s details.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Romanowicz, M., McKean, A.J. & Vande Voort, J. A case of a four-year-old child adopted at eight months with unusual mood patterns and significant polypharmacy. BMC Psychiatry 17 , 330 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1492-y

Download citation

Received : 20 December 2016

Accepted : 01 September 2017

Published : 11 September 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1492-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Polypharmacy

- Disinhibited social engagement disorder

BMC Psychiatry

ISSN: 1471-244X

- General enquiries: [email protected]

DBP Community Systems-Based Cases

Introduction.

Following are case studies of children with typical developmental behavioral issues that may require a host of referrals and recommendations.

Case Studies

Case 1: case 2: case 3: sophie mark alejandro.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- About Children & Schools

- About the National Association of Social Workers

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Literature review, alive program, implications for school social work practice.

- < Previous

Trauma and Early Adolescent Development: Case Examples from a Trauma-Informed Public Health Middle School Program

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jason Scott Frydman, Christine Mayor, Trauma and Early Adolescent Development: Case Examples from a Trauma-Informed Public Health Middle School Program, Children & Schools , Volume 39, Issue 4, October 2017, Pages 238–247, https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdx017

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Middle-school-age children are faced with a variety of developmental tasks, including the beginning phases of individuation from the family, building peer groups, social and emotional transitions, and cognitive shifts associated with the maturation process. This article summarizes how traumatic events impair and complicate these developmental tasks, which can lead to disruptive behaviors in the school setting. Following the call by Walkley and Cox for more attention to be given to trauma-informed schools, this article provides detailed information about the Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience program: a school-based, trauma-informed intervention for middle school students. This public health model uses psychoeducation, cognitive differentiation, and brief stress reduction counseling sessions to facilitate socioemotional development and academic progress. Case examples from the authors’ clinical work in the New Haven, Connecticut, urban public school system are provided.

Within the U.S. school system there is growing awareness of how traumatic experience negatively affects early adolescent development and functioning ( Chanmugam & Teasley, 2014 ; Perfect, Turley, Carlson, Yohannan, & Gilles, 2016 ; Porche, Costello, & Rosen-Reynoso, 2016 ; Sibinga, Webb, Ghazarian, & Ellen, 2016 ; Turner, Shattuck, Finkelhor, & Hamby, 2017 ; Woodbridge et al., 2016 ). The manifested trauma symptoms of these students have been widely documented and include self-isolation, aggression, and attentional deficit and hyperactivity, producing individual and schoolwide difficulties ( Cook et al., 2005 ; Iachini, Petiwala, & DeHart, 2016 ; Oehlberg, 2008 ; Sajnani, Jewers-Dailley, Brillante, Puglisi, & Johnson, 2014 ). To address this vulnerability, school social workers should be aware of public health models promoting prevention, data-driven investigation, and broad-based trauma interventions ( Chafouleas, Johnson, Overstreet, & Santos, 2016 ; Johnson, 2012 ; Moon, Williford, & Mendenhall, 2017 ; Overstreet & Chafouleas, 2016 ; Overstreet & Matthews, 2011 ). Without comprehensive and effective interventions in the school setting, seminal adolescent developmental tasks are at risk.

This article follows the twofold call by Walkley and Cox (2013) for school social workers to develop a heightened awareness of trauma exposure's impact on childhood development and to highlight trauma-informed practices in the school setting. In reference to the former, this article will not focus on the general impact of toxic stress, or chronic trauma, on early adolescents in the school setting, as this work has been widely documented. Rather, it begins with a synthesis of how exposure to trauma impairs early adolescent developmental tasks. As to the latter, we will outline and discuss the Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience (ALIVE) program, a school-based, trauma-informed intervention that is grounded in a public health framework. The model uses psychoeducation, cognitive differentiation, and brief stress reduction sessions to promote socioemotional development and academic progress. We present two clinical cases as examples of trauma-informed, school-based practice, and then apply their experience working in an urban, public middle school to explicate intervention theory and practice for school social workers.

Impact of Trauma Exposure on Early Adolescent Developmental Tasks

Social development.

Impact of Trauma on Early Adolescent Development

| Developmental Task . | Impact . | Citations . |

|---|---|---|

| Social development | ||

| Forming and maintaining healthy relationships | ; ; ; | |

| Mentalization and increased cognitive discrimination | ; | |

| Moving from family to peers as primary relationships | ||

| Cognitive development and emotional regulation | ||

| Increasing impulse control and affect regulation | ; ; | |

| Coordinating dynamic between cognition and affect | ; ; ; | |

| Developmental Task . | Impact . | Citations . |

|---|---|---|

| Social development | ||

| Forming and maintaining healthy relationships | ; ; ; | |

| Mentalization and increased cognitive discrimination | ; | |

| Moving from family to peers as primary relationships | ||

| Cognitive development and emotional regulation | ||

| Increasing impulse control and affect regulation | ; ; | |

| Coordinating dynamic between cognition and affect | ; ; ; | |

Traumatic experiences may create difficulty with developing and differentiating another person's point of view (that is, mentalization) due to the formation of rigid cognitive schemas that dictate notions of self, others, and the external world ( Frydman & McLellan, 2014 ). For early adolescents, the ability to diversify a single perspective with complexity is central to modulating affective experience. Without the capacity to diversify one's perspective, there is often difficulty differentiating between a nonthreatening current situation that may harbor reminders of the traumatic experience and actual traumatic events. Incumbent on the school social worker is the need to help students understand how these conflicts may trigger a memory of harm, abandonment, or loss and how to differentiate these past memories from the present conflict. This is of particular concern when these reactions are conflated with more common middle school behaviors such as withdrawing, blaming, criticizing, and gossiping ( Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, 2008 ).

Encouraging cognitive discrimination is particularly meaningful given that the second social developmental task for early adolescents is the re-orientation of their primary relationships with family toward peers ( Henderson & Thompson, 2010 ). This shift may become complicated for students facing traumatic stress, resulting in a stunted movement away from familiar connections or a displacement of dysfunctional family relationships onto peers. For example, in the former, a student who has witnessed and intervened to protect his mother from severe domestic violence might believe he needs to sacrifice himself and be available to his mother, forgoing typical peer interactions. In the latter, a student who was beaten when a loud, intoxicated family member came home might become enraged, anxious, or anticipate violence when other students raise their voices.

Cognitive Development and Emotional Regulation

During normative early adolescent development, the prefrontal cortex undergoes maturational shifts in cognitive and emotional functioning, including increased impulse control and affect regulation ( Wigfield, Lutz, & Wagner, 2005 ). However, these developmental tasks can be negatively affected by chronic exposure to traumatic events. Stressful situations often evoke a fear response, which inhibits executive functioning and commonly results in a fight-flight-freeze reaction. If a student does not possess strong anxiety management skills to cope with reminders of the trauma, the student is prone to further emotional dysregulation, lowered frustration tolerance, and increased behavioral problems and depressive symptoms ( Iachini et al., 2016 ; Saltzman, Steinberg, Layne, Aisenberg, & Pynoos, 2001 ).

Typical cognitive development in early adolescence is defined by the ambiguity of a transitional stage between childhood remedial capacity and adult refinement ( Casey & Caudle, 2013 ; Van Duijvenvoorde & Crone, 2013 ). Casey and Caudle (2013) found that although adolescents performed equally as well as, if not better than, adults on a self-control task when no emotional information was present, the introduction of affectively laden social cues resulted in diminished performance. The developmental challenge for the early adolescent then is to facilitate the coordination of this ever-shifting dynamic between cognition and affect. Although early adolescents may display efficient and logically informed behaviors, they may struggle to sustain these behaviors, especially in the presence of emotional stimuli ( Casey & Caudle, 2013 ; Van Duijvenvoorde & Crone, 2013 ). Because trauma often evokes an emotional response ( Johnson & Lubin, 2015 ), these findings insinuate that those early adolescents who are chronically exposed will have ongoing regulation difficulties. Further empirical findings considering the cognitive effects of trauma exposure on the adolescent brain have highlighted detriments in working memory, inhibition, memory, and planning ability ( Moradi, Neshat Doost, Taghavi, Yule, & Dalgleish, 1999 ).

Using a Public Health Framework for School-Based, Trauma-Informed Services

The need for a more informed and comprehensive approach to addressing trauma within the schools has been widely articulated ( Chafouleas et al., 2016 ; Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011 ; Jaycox, Kataoka, Stein, Langley, & Wong, 2012 ; Overstreet & Chafouleas, 2016 ; Perry & Daniels, 2016 ). Overstreet and Matthews (2011) suggested that using a public health model to address trauma in schools will promote prevention, early identification, and data-driven investigation and yield broad-based intervention on a policy and communitywide level. A public health approach focuses on developing interventions that address the underlying causal processes that lead to social, emotional, and cognitive maladjustment. Opening the dialogue to the entire student body, as well as teachers and administrators, promotes inclusion and provides a comprehensive foundation for psychoeducation, assessment, and prevention.

ALIVE: A Comprehensive Public Health Intervention for Middle School Students

| Psychoeducation . | Assessment . | Individualized Support . |

|---|---|---|

| Conduct psychoeducational conversations with all students on the impact of traumatic exposure across developmental domains: social, emotional, cognitive, and academic | Informal process accompanying psychoeducation that leads to the identification of students requiring further, more intensive support | One-on-one counseling related to student's adverse experience Engagement occurs as traumatic stress influences school-based behaviors |

| Psychoeducation . | Assessment . | Individualized Support . |

|---|---|---|

| Conduct psychoeducational conversations with all students on the impact of traumatic exposure across developmental domains: social, emotional, cognitive, and academic | Informal process accompanying psychoeducation that leads to the identification of students requiring further, more intensive support | One-on-one counseling related to student's adverse experience Engagement occurs as traumatic stress influences school-based behaviors |

Note: ALIVE = Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience.

Psychoeducation

The classroom is a place traditionally dedicated to academic pursuits; however, it also serves as an indicator of trauma's impact on cognitive functioning evidenced by poor grades, behavioral dysregulation, and social turbulence. ALIVE practitioners conduct weekly trauma-focused dialogues in the classroom to normalize conversations addressing trauma, to recruit and rehearse more adaptive cognitive skills, and to engage in an insight-oriented process ( Sajnani et al., 2014 ).

Using a parable as a projective tool for identification and connection, the model helps students tolerate direct discussions about adverse experiences. The ALIVE practitioner begins each academic year by telling the parable of a woman named Miss Kendra, who struggled to cope with the loss of her 10-year-old child. Miss Kendra is able to make meaning out of her loss by providing support for schoolchildren who have encountered adverse experiences, serving as a reminder of the strength it takes to press forward after a traumatic event. The intention of this parable is to establish a metaphor for survival and strength to fortify the coping skills already held by trauma-exposed middle school students. Furthermore, Miss Kendra offers early adolescents an opportunity to project their own needs onto the story, creating a personalized figure who embodies support for socioemotional growth.

Following this parable, the students’ attention is directed toward Miss Kendra's List, a poster that is permanently displayed in the classroom. The list includes a series of statements against adolescent maltreatment, comprehensively identifying various traumatic stressors such as witnessing domestic violence; being physically, verbally, or sexually abused; and losing a loved one to neighborhood violence. The second section of the list identifies what may happen to early adolescents when they experience trauma from emotional, social, and academic perspectives. The practitioner uses this list to provide information about the nature and impact of trauma, while modeling for students and staff the ability to discuss difficult experiences as a way of connecting with one another with a sense of hope and strength.

Furthermore, creating a dialogue about these issues with early adolescents facilitates a culture of acceptance, tolerance, and understanding, engendering empathy and identification among students. This fostering of interpersonal connection provides a reparative and differentiated experience to trauma ( Hartling & Sparks, 2008 ; Henderson & Thompson, 2010 ; Johnson & Lubin, 2015 ) and is particularly important given the peer-focused developmental tasks of early adolescence. The positive feelings evoked through classroom-based conversation are predicated on empathic identification among the students and an accompanying sense of relief in understanding the scope of trauma's impact. Furthermore, the consistent appearance of and engagement by the ALIVE practitioner, and the continual presence of Miss Kendra's list, effectively counters traumatically informed expectations of abandonment and loss while aligning with a public health model that attends to the impact of trauma on a regular, systemwide basis.

Participatory and Somatic Indicators for Informal Assessment during the Psychoeducation Component of the ALIVE Intervention

| Participatory . | Somatic . |

|---|---|

| Attempting to the conversation | A disposition |

| Subtle forms of | Bodily of somatic activation |

| A in specific dialogue around certain trauma types | Physical displays of or |

| , functions as a physical form of avoidance | |

| Participatory . | Somatic . |

|---|---|

| Attempting to the conversation | A disposition |

| Subtle forms of | Bodily of somatic activation |

| A in specific dialogue around certain trauma types | Physical displays of or |

| , functions as a physical form of avoidance | |

Notes: ALIVE = Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience. Examples are derived from authors’ clinical experiences.

In addition to behavioral symptoms, the content of conversation is considered. All practitioners in the ALIVE program are mandated reporters, and any content presented that meets criteria for suspicion of child maltreatment is brought to the attention of the school leadership and ALIVE director. According to Johnson (2012) , reports of child maltreatment to the Connecticut Department of Child and Family Services have actually decreased in the schools where the program has been implemented “because [the ALIVE program is] catching problems well before they have risen to the severity that would require reporting” (p. 17).

Case Example 1

The following demonstrates a middle school classroom psychoeducation session and assessment facilitated by an ALIVE practitioner (the first author). All names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect confidentiality.

Ms. Skylar's seventh grade class comprised many students living in low-income housing or in a neighborhood characterized by high poverty and frequent criminal activity. During the second week of school, I introduced myself as a practitioner who was here to speak directly about difficult experiences and how these instances might affect academic functioning and students’ thoughts about themselves, others, and their environment.

After sharing the Miss Kendra parable and list, I invited the students to share their thoughts about Miss Kendra and her journey. Tyreke began the conversation by wondering whether Miss Kendra lost her child to gun violence, exploring the connection between the list and the story and his own frequent exposure to neighborhood shootings. To transition a singular connection to a communal one, I asked the students if this was a shared experience. The majority of students nodded in agreement. I referred the students back to the list and asked them to identify how someone's school functioning or mood may be affected by ongoing neighborhood gun violence. While the students read the list, I actively monitored reactions and scanned for inattention and active avoidance. Performing both active facilitation of discussion and monitoring students’ reactions is critical in accomplishing the goals of providing quality psychoeducation and identifying at-risk students for intervention.

After inspection, Cleo remarked that, contrary to a listed outcome on Miss Kendra's list, neighborhood gun violence does not make him feel lonely; rather, he “doesn't care about it.” Slumped down in his chair, head resting on his crossed arms on the desk in front of him, Cleo's body language suggested a somatized disengagement. I invited other students to share their individual reactions. Tyreke agreed that loneliness is not the identified affective experience; rather, for him, it's feeling “mad or scared.” Immediately, Greg concurred, expressing that “it makes me more mad, and I think about my family.”

Encouraging a variety of viewpoints, I stated, “It sounds like it might make you mad, scared, and may even bring up thoughts about your family. I wonder why people have different reactions?” Doing so moved the conversation into a phase of deeper reflection, simultaneously honoring the students’ voiced experience while encouraging critical thinking. A number of students responded by offering connections to their lives, some indicating they had difficulty identifying feelings. I reflected back, “Sometimes people feel something, but can't really put their finger on it, and sometimes they know exactly how they feel or who it makes them think about.”

I followed with a question: “How do you think it affects your schoolwork or feelings when you're in school?” Greg and Natalia both offered that sometimes difficult or confusing thoughts can consume their whole day, even while in class. Sharon began to offer a related comment when Cleo interrupted by speaking at an elevated volume to his desk partner, Tyreke. The two began to snicker and pull focus. By the time they gained the class's full attention, Cleo was openly laughing and pushing his chair back, stating, “No way! She DID!? That's crazy”; he began to stand up, enlisting Tyreke in the process. While this disruption may be viewed as a challenge to the discussion, it is essential to understand all behavior in context of the session's trauma content. Therefore, Cleo's outburst was interpreted as a potential avenue for further exploration of the topic regarding gun violence and difficulties concentrating. In turn, I posed this question to the class: “Should we talk about this stuff? I wonder if sometimes people have a hard time tolerating it. Can anybody think of why it might be important? Sharon, I think you were saying something about this.” While Sharon continued to share, Cleo and Tyreke gradually shifted their attention back to the conversation. I noted the importance of an individual follow-up with Cleo.

Natalia jumped back in the conversation, stating, “I think we talk about stuff like this so we know about it and can help people with it.” I checked in with the rest of the class about this strategy for coping with the impact of trauma exposure on school functioning: “So it sounds like these thoughts have a pretty big impact on your day. If that's the case, how do you feel less worried or mad or scared?” Marta quickly responded, “You could talk to someone.” I responded, “Part of my job here is to be a person to talk to one-on-one about these things. Hopefully, it will help you feel better to get some of that stuff off your chest.” The students nodded, acknowledging that I would return to discuss other items on the list and that there would be opportunities to check in with me individually if needed.

On reflection, Cleo's disruption in the discussion may be attributed to his personal difficulty emotionally managing intrusive thoughts while in school. This clinical assumption was not explicitly named in the moment, but was noted as information for further individual follow-up. When I met individually with Cleo, Cleo reported that his cousin had been shot a month ago, causing him to feel confused and angry. I continued to work with him individually, which resulted in a reduction of behavioral disruptions in the classroom.

In the preceding case example, the practitioner performed a variety of public health tasks. Foremost was the introduction of how traumatic experience may affect individuals and their relationships with others and their role as a student. Second, the practitioner used Miss Kendra and her list as a foundational mechanism to ground the conversation and serve as a reference point for the students’ experience. Finally, the practitioner actively monitored individual responses to the material as a means of identifying students who may require more support. All three of these processes are supported within the public health framework as a means toward assessment and early intervention for early adolescents who may be exposed to trauma.

Individualized Stress Reduction Intervention

Students are seen for individualized support if they display significant externalizing or internalizing trauma-related behavior. Students are either self-referred; referred by a teacher, administrator, or staff member; or identified by an ALIVE practitioner. Following the principle of immediate engagement based on emergent traumatic material, individual sessions are brief, lasting only 15 to 20 minutes. Using trauma-centered psychotherapy ( Johnson & Lubin, 2015 ), a brief inquiry addressing the current problem is conducted to identify the trauma trigger connected to the original harm, fostering cognitive discrimination. Conversation about the adverse experience proceeds in a calm, direct way focusing on differentiating between intrusive memories and the current situation at school ( Sajnani et al., 2014 ). Once the student exhibits greater emotional regulation, the ALIVE practitioner returns the student to the classroom in a timely manner and may provide either brief follow-up sessions for preventive purposes or, when appropriate, refer the student to more regular, clinical support in or out of the school.

Case Example 2

The following case example is representative of the brief, immediate, and open engagement with traumatic material and encouragement of cognitive discrimination. This intervention was conducted with a sixth grade student, Jacob (name and identifying information changed to ensure confidentiality), by an ALIVE practitioner (the second author).

I found Jacob in the hallway violently shaking a trash can, kicking the classroom door, and slamming his hands into the wall and locker. His teacher was standing at the door, distressed, stating, “Jacob, you need to calm down and go to the office, or I'm calling home!” Jacob yelled, “It's not fair, it was him, not me! I'm gonna fight him!” As I approached, I asked what was making him so angry, but he said, “I don't want to talk about it.” Rather than asking him to calm down or stop slamming objects, I instead approached the potential memory agitating him, stating, “My guess is that you are angry for a very good reason.” Upon this simple connection, he sighed and stopped kicking the trash can and slamming the wall. Jacob continued to demonstrate physical and emotional activation, pacing the hallway and making a fist; however, he was able to recount putting trash in the trash can when a peer pushed him from behind, causing him to yell. Jacob explained that his teacher heard him yelling and scolded him, making him more mad. Jacob stated, “She didn't even know what happened and she blamed me. I was trying to help her by taking out all of our breakfast trash. It's not fair.”

The ALIVE practitioner listens to students’ complaints with two ears, one for the current complaint and one for affect-laden details that may be connected to the original trauma to inquire further into the source of the trigger. Affect-laden details in case example 2 include Jacob's anger about being blamed (rather than toward the student who pushed him), his original intention to help, and his repetition of the phrase “it's not fair.” Having met with Jacob previously, I was aware that his mother suffers from physical and mental health difficulties. When his mother is not doing well, he (as the parentified child) typically takes care of the household, performing tasks like cooking, cleaning, and helping with his two younger siblings and older autistic brother. In the past, Jacob has discussed both idealizing his mother and holding internalized anger that he rarely expresses at home because he worries his anger will “make her sick.”

I know sometimes when you are trying to help mom, there are times she gets upset with you for not doing it exactly right, or when your brothers start something, she will blame you. What just happened sounds familiar—you were trying to help your teacher by taking out the garbage when another student pushed you, and then you were the one who got in trouble.

Jacob nodded his head and explained that he was simply trying to help.

I moved into a more detailed inquiry, to see if there was a more recent stressor I was unaware of. When I asked how his mother was doing this week, Jacob revealed that his mother's health had deteriorated and his aunt had temporarily moved in. Jacob told me that he had been yelled at by both his mother and his aunt that morning, when his younger brother was not ready for school. I asked, “I wonder if when the student pushed you it reminded you of getting into trouble because of something your little brother did this morning?” Jacob nodded. The displacement was clear: He had been reminded of this incident at school and was reacting with anger based on his family dynamic, and worries connected to his mother.

My guess is that you were a mix of both worried and angry by the time you got to school, with what's happening at home. You were trying to help with the garbage like you try to help mom when she isn't doing well, so when you got pushed it was like your brother being late, and then when you got blamed by your teacher it was like your mom and aunt yelling, and it all came flooding back in. The problem is, you let out those feelings here. Even though there are some similar things, it's not totally the same, right? Can you tell me what is different?

Jacob nodded and was able to explain that the other student was probably just playing and did not mean to get him into trouble, and that his teacher did not usually yell at him or make him worried. Highlighting this important differentiation, I replied, “Right—and fighting the student or yelling at the teacher isn't going to solve this, but more importantly, it isn't going to make your mom better or have your family go any easier on you either.” Jacob stated that he knew this was true.

I reassured Jacob that I could help him let out those feelings of worry and anger connected to home so they did not explode out at school and planned to meet again. Jacob confirmed that he was willing to do that. He was able to return to the classroom without incident, with the entire intervention lasting less than 15 minutes.

In case example 2, the practitioner was available for an immediate engagement with disturbing behaviors as they were happening by listening for similarities between the current incident and traumatic stressors; asking for specific details to more effectively help Jacob understand how he was being triggered in school; providing psychoeducation about how these two events had become confused and aiding him in cognitively differentiating between the two; and, last, offering to provide further support to reduce future incidents.

Germane to the practice of school social work is the ability to work flexibly within a public health model to attend to trauma within the school setting. First, we suggest that a primary implication for school social workers is not to wait for explicit problems related to known traumatic experiences to emerge before addressing trauma in the school, but, rather, to follow a model of prevention-assessment-intervention. School social workers are in a unique position within the school system to disseminate trauma-informed material to both students and staff in a preventive capacity. Facilitating this implementation will help to establish a tone and sharpened focus within the school community, norming the process of articulating and engaging with traumatic material. In the aforementioned classroom case example, we have provided a sample of how school social workers might work with entire classrooms on a preventive basis regarding trauma, rather than waiting for individual referrals.

Second, in addition to functional behavior assessments and behavior intervention plans, school social workers maintain a keen eye for qualitative behavioral assessment ( National Association of Social Workers, 2012 ). Using this skill set within a trauma-informed model will help to identify those students in need who may be reluctant or resistant to explicitly ask for help. As called for by Walkley and Cox (2013) , we suggest that using the information presented in Table 1 will help school social workers understand, identify, and assess the impact of trauma on early adolescent developmental tasks. If school social workers engage on a classroom level in trauma psychoeducation and conversations, the information in Table 3 may assist with assessment of children and provide a basis for checking in individually with students as warranted.

Third, school social workers are well positioned to provide individual targeted, trauma-informed interventions based on previous knowledge of individual trauma and through widespread assessment ( Walkley & Cox, 2013 ). The individual case example provides one way of immediately engaging with students who are demonstrating trauma-based behaviors. In this model, school social workers engage in a brief inquiry addressing the current trauma to identify the trauma trigger, discuss the adverse experience in a calm but direct way, and help to differentiate between intrusive memories and the current situation at school. For this latter component, the focus is on cognitive discrimination and emotional regulation so that students can reengage in the classroom within a short time frame.

Fourth, given social work's roots in collaboration and community work, school social workers are encouraged to use a systems-based approach in partnering with allied practitioners and institutions ( D'Agostino, 2013 ), thus supporting the public health tenet of establishing and maintaining a link to the wider community. This may include referring students to regular clinical support in or out of the school. Although the implementation of a trauma-informed program will vary across schools, we suggest that school social workers have the capacity to use a public health school intervention model to ecologically address the psychosocial and behavioral issues stemming from trauma exposure.

As increasing attention is being given to adverse childhood experiences, a tiered approach that uses a public health framework in the schools is necessitated. Nevertheless, there are some limitations to this approach. First, although the interventions outlined here are rooted in prevention and early intervention, there are times when formal, intensive treatment outside of the school setting is warranted. Second, the ALIVE program has primarily been implemented by ALIVE practitioners; the results from piloting this public health framework in other school settings with existing school personnel, such as school social workers, will be necessary before widespread replication.

The public health framework of prevention-assessment-intervention promotes continual engagement with middle school students’ chronic exposure to traumatic stress. There is a need to provide both broad-based and individualized support that seeks to comprehensively ameliorate the social, emotional, and cognitive consequences on early adolescent developmental milestones associated with traumatic experiences. We contend that school social workers are well positioned to address this critical public health issue through proactive and widespread psychoeducation and assessment in the schools, and we have provided case examples to demonstrate one model of doing this work within the school day. We hope that this article inspires future writing about how school social workers individually and systemically address trauma in the school system. In alignment with Walkley and Cox (2013) , we encourage others to highlight their practice in incorporating trauma-informed, school-based programming in an effort to increase awareness of effective interventions.

Card , N. A. , Stucky , B. D. , Sawalani , G. M. , & Little , T. D. ( 2008 ). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review of gender difference, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment . Child Development, 79 , 1185 – 1229 .

Google Scholar

Casey , B. J. , & Caudle , K. ( 2013 ). The teenage brain: Self control . Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22 ( 2 ), 82 – 87 .

Chafouleas , S. M. , Johnson , A. H. , Overstreet , S. , & Santos , N. M. ( 2016 ). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 144 – 162 .

Chanmugam , A. , & Teasley , M. L. ( 2014 ). What should school social workers know about children exposed to intimate partner violence? [Editorial]. Children & Schools, 36 , 195 – 198 .

Cook , A. , Spinazzola , J. , Ford , J. , Lanktree , C. , Blaustein , M. , Cloitre , M. , et al. . ( 2005 ). Complex trauma in children and adolescents . Psychiatric Annals, 35 , 390 – 398 .

D'Agostino , C. ( 2013 ). Collaboration as an essential social work skill [Resources for Practice] . Children & Schools, 35 , 248 – 251 .

Durlak , J. A. , Weissberg , R. P. , Dymnicki , A. B. , Taylor , R. D. , & Schellinger , K. B. ( 2011 ). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions . Child Development, 82 , 405 – 432 .

Frydman , J. S. , & McLellan , L. ( 2014 ). Complex trauma and executive functioning: Envisioning a cognitive-based, trauma-informed approach to drama therapy. In N. Sajnani & D. R. Johnson (Eds.), Trauma-informed drama therapy: Transforming clinics, classrooms, and communities (pp. 179 – 205 ). Springfield, IL : Charles C Thomas .

Google Preview

Hartling , L. , & Sparks , J. ( 2008 ). Relational-cultural practice: Working in a nonrelational world . Women & Therapy, 31 , 165 – 188 .

Henderson , D. , & Thompson , C. ( 2010 ). Counseling children (8th ed.). Belmont, CA : Brooks-Cole .

Iachini , A. L. , Petiwala , A. F. , & DeHart , D. D. ( 2016 ). Examining adverse childhood experiences among students repeating the ninth grade: Implications for school dropout prevention . Children & Schools, 38 , 218 – 227 .

Jaycox , L. H. , Kataoka , S. H. , Stein , B. D. , Langley , A. K. , & Wong , M. ( 2012 ). Cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools . Journal of Applied School Psychology, 28 , 239 – 255 .

Johnson , D. R. ( 2012 ). Ask every child: A public health initiative addressing child maltreatment [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.traumainformedschools.org/publications.html

Johnson , D. R. , & Lubin , H. ( 2015 ). Principles and techniques of trauma-centered psychotherapy . Arlington, VA : American Psychiatric Publishing .

Moon , J. , Williford , A. , & Mendenhall , A. ( 2017 ). Educators’ perceptions of youth mental health: Implications for training and the promotion of mental health services in schools . Child and Youth Services Review, 73 , 384 – 391 .

Moradi , A. R. , Neshat Doost , H. T. , Taghavi , M. R. , Yule , W. , & Dalgleish , T. ( 1999 ). Everyday memory deficits in children and adolescents with PTSD: Performance on the Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test . Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40 , 357 – 361 .

National Association of Social Workers . ( 2012 ). NASW standards for school social work services . Retrieved from http://www.naswdc.org/practice/standards/NASWSchoolSocialWorkStandards.pdf

Oehlberg , B. ( 2008 ). Why schools need to be trauma informed . Trauma and Loss: Research and Interventions, 8 ( 2 ), 1 – 4 .

Overstreet , S. , & Chafouleas , S. M. ( 2016 ). Trauma-informed schools: Introduction to the special issue . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 1 – 6 .

Overstreet , S. , & Matthews , T. ( 2011 ). Challenges associated with exposure to chronic trauma: Using a public health framework to foster resilient outcomes among youth . Psychology in the Schools, 48 , 738 – 754 .

Perfect , M. , Turley , M. , Carlson , J. S. , Yohannan , J. , & Gilles , M. S. ( 2016 ). School-related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms in students: A systematic review of research from 1990 to 2015 . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 7 – 43 .

Perry , D. L. , & Daniels , M. L. ( 2016 ). Implementing trauma-informed practices in the school setting: A pilot study . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 177 – 188 .

Porche , M. V. , Costello , D. M. , & Rosen-Reynoso , M. ( 2016 ). Adverse family experiences, child mental health, and educational outcomes for a national sample of students . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 44 – 60 .

Sajnani , N. , Jewers-Dailley , K. , Brillante , A. , Puglisi , J. , & Johnson , D. R. ( 2014 ). Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience. In N. Sajnani & D. R. Johnson (Eds.), Trauma-informed drama therapy: Transforming clinics, classrooms, and communities (pp. 206 – 242 ). Springfield, IL : Charles C Thomas .

Saltzman , W. R. , Steinberg , A. M. , Layne , C. M. , Aisenberg , E. , & Pynoos , R. S. ( 2001 ). A developmental approach to school-based treatment of adolescents exposed to trauma and traumatic loss . Journal of Child and Adolescent Group Therapy, 11 ( 2–3 ), 43 – 56 .

Sibinga , E. M. , Webb , L. , Ghazarian , S. R. , & Ellen , J. M. ( 2016 ). School-based mindfulness instruction: An RCT . Pediatrics, 137 ( 1 ), e20152532 .

Tucker , C. , Smith-Adcock , S. , & Trepal , H. C. ( 2011 ). Relational-cultural theory for middle school counselors . Professional School Counseling, 14 , 310 – 316 .

Turner , H. A. , Shattuck , A. , Finkelhor , D. , & Hamby , S. ( 2017 ). Effects of poly-victimization on adolescent social support, self-concept, and psychological distress . Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32 , 755 – 780 .

van der Kolk , B. A. ( 2005 ). Developmental trauma disorder: Toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories . Psychiatric Annals, 35 , 401 – 408 .

Van Duijvenvoorde , A.C.K. , & Crone , E. A. ( 2013 ). The teenage brain: A neuroeconomic approach to adolescent decision making . Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22 ( 2 ), 114 – 120 .

Walkley , M. , & Cox , T. L. ( 2013 ). Building trauma-informed schools and communities [Trends & Resources] . Children & Schools, 35 , 123 – 126 .

Wigfield , A. W. , Lutz , S. L. , & Wagner , L. ( 2005 ). Early adolescents’ development across the middle school years: Implications for school counselors . Professional School Counseling, 9 ( 2 ), 112 – 119 .

Woodbridge , M. W. , Sumi , W. C. , Thornton , S. P. , Fabrikant , N. , Rouspil , K. M. , Langley , A. K. , & Kataoka , S. H. ( 2016 ). Screening for trauma in early adolescence: Findings from a diverse school district . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 89 – 105 .

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| August 2017 | 5 |

| September 2017 | 34 |

| October 2017 | 112 |

| November 2017 | 163 |

| December 2017 | 85 |

| January 2018 | 75 |

| February 2018 | 83 |

| March 2018 | 115 |

| April 2018 | 160 |

| May 2018 | 76 |

| June 2018 | 83 |

| July 2018 | 105 |

| August 2018 | 342 |

| September 2018 | 273 |

| October 2018 | 339 |

| November 2018 | 307 |

| December 2018 | 308 |

| January 2019 | 52 |

| February 2019 | 67 |

| March 2019 | 86 |

| April 2019 | 97 |

| May 2019 | 67 |

| June 2019 | 116 |

| July 2019 | 220 |

| August 2019 | 213 |

| September 2019 | 299 |

| October 2019 | 312 |

| November 2019 | 387 |

| December 2019 | 222 |

| January 2020 | 235 |

| February 2020 | 389 |

| March 2020 | 291 |

| April 2020 | 488 |

| May 2020 | 154 |

| June 2020 | 337 |

| July 2020 | 298 |

| August 2020 | 283 |

| September 2020 | 494 |

| October 2020 | 583 |

| November 2020 | 535 |

| December 2020 | 385 |

| January 2021 | 332 |

| February 2021 | 543 |

| March 2021 | 582 |

| April 2021 | 617 |

| May 2021 | 401 |

| June 2021 | 361 |

| July 2021 | 342 |

| August 2021 | 314 |

| September 2021 | 388 |

| October 2021 | 468 |

| November 2021 | 396 |

| December 2021 | 310 |

| January 2022 | 244 |

| February 2022 | 349 |

| March 2022 | 362 |

| April 2022 | 441 |

| May 2022 | 236 |

| June 2022 | 264 |

| July 2022 | 240 |

| August 2022 | 202 |

| September 2022 | 258 |

| October 2022 | 355 |

| November 2022 | 345 |

| December 2022 | 276 |

| January 2023 | 228 |

| February 2023 | 358 |

| March 2023 | 408 |

| April 2023 | 436 |

| May 2023 | 292 |

| June 2023 | 248 |

| July 2023 | 226 |

| August 2023 | 203 |

| September 2023 | 248 |

| October 2023 | 304 |

| November 2023 | 429 |

| December 2023 | 333 |

| January 2024 | 189 |

| February 2024 | 264 |

| March 2024 | 362 |

| April 2024 | 563 |

| May 2024 | 315 |

| June 2024 | 282 |

| July 2024 | 274 |

| August 2024 | 406 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- About Children & Schools

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1545-682X

- Print ISSN 1532-8759

- Copyright © 2024 National Association of Social Workers

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy