How to Write a Perfect Assignment: Step-By-Step Guide

Table of contents

- 1 How to Structure an Assignment?

- 2.1 The research part

- 2.2 Planning your text

- 2.3 Writing major parts

- 3 Expert Tips for your Writing Assignment

- 4 Will I succeed with my assignments?

- 5 Conclusion

How to Structure an Assignment?

To cope with assignments, you should familiarize yourself with the tips on formatting and presenting assignments or any written paper, which are given below. It is worth paying attention to the content of the paper, making it structured and understandable so that ideas are not lost and thoughts do not refute each other.

If the topic is free or you can choose from the given list — be sure to choose the one you understand best. Especially if that could affect your semester score or scholarship. It is important to select an engaging title that is contextualized within your topic. A topic that should captivate you or at least give you a general sense of what is needed there. It’s easier to dwell upon what interests you, so the process goes faster.

To construct an assignment structure, use outlines. These are pieces of text that relate to your topic. It can be ideas, quotes, all your thoughts, or disparate arguments. Type in everything that you think about. Separate thoughts scattered across the sheets of Word will help in the next step.

Then it is time to form the text. At this stage, you have to form a coherent story from separate pieces, where each new thought reinforces the previous one, and one idea smoothly flows into another.

Main Steps of Assignment Writing

These are steps to take to get a worthy paper. If you complete these step-by-step, your text will be among the most exemplary ones.

The research part

If the topic is unique and no one has written about it yet, look at materials close to this topic to gain thoughts about it. You should feel that you are ready to express your thoughts. Also, while reading, get acquainted with the format of the articles, study the details, collect material for your thoughts, and accumulate different points of view for your article. Be careful at this stage, as the process can help you develop your ideas. If you are already struggling here, pay for assignment to be done , and it will be processed in a split second via special services. These services are especially helpful when the deadline is near as they guarantee fast delivery of high-quality papers on any subject.

If you use Google to search for material for your assignment, you will, of course, find a lot of information very quickly. Still, the databases available on your library’s website will give you the clearest and most reliable facts that satisfy your teacher or professor. Be sure you copy the addresses of all the web pages you will use when composing your paper, so you don’t lose them. You can use them later in your bibliography if you add a bit of description! Select resources and extract quotes from them that you can use while working. At this stage, you may also create a request for late assignment if you realize the paper requires a lot of effort and is time-consuming. This way, you’ll have a backup plan if something goes wrong.

Planning your text

Assemble a layout. It may be appropriate to use the structure of the paper of some outstanding scientists in your field and argue it in one of the parts. As the planning progresses, you can add suggestions that come to mind. If you use citations that require footnotes, and if you use single spacing throughout the paper and double spacing at the end, it will take you a very long time to make sure that all the citations are on the exact pages you specified! Add a reference list or bibliography. If you haven’t already done so, don’t put off writing an essay until the last day. It will be more difficult to do later as you will be stressed out because of time pressure.

Writing major parts

It happens that there is simply no mood or strength to get started and zero thoughts. In that case, postpone this process for 2-3 hours, and, perhaps, soon, you will be able to start with renewed vigor. Writing essays is a great (albeit controversial) way to improve your skills. This experience will not be forgotten. It will certainly come in handy and bring many benefits in the future. Do your best here because asking for an extension is not always possible, so you probably won’t have time to redo it later. And the quality of this part defines the success of the whole paper.

Writing the major part does not mean the matter is finished. To review the text, make sure that the ideas of the introduction and conclusion coincide because such a discrepancy is the first thing that will catch the reader’s eye and can spoil the impression. Add or remove anything from your intro to edit it to fit the entire paper. Also, check your spelling and grammar to ensure there are no typos or draft comments. Check the sources of your quotes so that your it is honest and does not violate any rules. And do not forget the formatting rules.

with the right tips and guidance, it can be easier than it looks. To make the process even more straightforward, students can also use an assignment service to get the job done. This way they can get professional assistance and make sure that their assignments are up to the mark. At PapersOwl, we provide a professional writing service where students can order custom-made assignments that meet their exact requirements.

Expert Tips for your Writing Assignment

Want to write like a pro? Here’s what you should consider:

- Save the document! Send the finished document by email to yourself so you have a backup copy in case your computer crashes.

- Don’t wait until the last minute to complete a list of citations or a bibliography after the paper is finished. It will be much longer and more difficult, so add to them as you go.

- If you find a lot of information on the topic of your search, then arrange it in a separate paragraph.

- If possible, choose a topic that you know and are interested in.

- Believe in yourself! If you set yourself up well and use your limited time wisely, you will be able to deliver the paper on time.

- Do not copy information directly from the Internet without citing them.

Writing assignments is a tedious and time-consuming process. It requires a lot of research and hard work to produce a quality paper. However, if you are feeling overwhelmed or having difficulty understanding the concept, you may want to consider getting accounting homework help online . Professional experts can assist you in understanding how to complete your assignment effectively. PapersOwl.com offers expert help from highly qualified and experienced writers who can provide you with the homework help you need.

Will I succeed with my assignments?

Anyone can learn how to be good at writing: follow simple rules of creating the structure and be creative where it is appropriate. At one moment, you will need some additional study tools, study support, or solid study tips. And you can easily get help in writing assignments or any other work. This is especially useful since the strategy of learning how to write an assignment can take more time than a student has.

Therefore all students are happy that there is an option to order your paper at a professional service to pass all the courses perfectly and sleep still at night. You can also find the sample of the assignment there to check if you are on the same page and if not — focus on your papers more diligently.

So, in the times of studies online, the desire and skill to research and write may be lost. Planning your assignment carefully and presenting arguments step-by-step is necessary to succeed with your homework. When going through your references, note the questions that appear and answer them, building your text. Create a cover page, proofread the whole text, and take care of formatting. Feel free to use these rules for passing your next assignments.

When it comes to writing an assignment, it can be overwhelming and stressful, but Papersowl is here to make it easier for you. With a range of helpful resources available, Papersowl can assist you in creating high-quality written work, regardless of whether you’re starting from scratch or refining an existing draft. From conducting research to creating an outline, and from proofreading to formatting, the team at Papersowl has the expertise to guide you through the entire writing process and ensure that your assignment meets all the necessary requirements.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

A step-by-step guide for creating and formatting APA Style student papers

The start of the semester is the perfect time to learn how to create and format APA Style student papers. This article walks through the formatting steps needed to create an APA Style student paper, starting with a basic setup that applies to the entire paper (margins, font, line spacing, paragraph alignment and indentation, and page headers). It then covers formatting for the major sections of a student paper: the title page, the text, tables and figures, and the reference list. Finally, it concludes by describing how to organize student papers and ways to improve their quality and presentation.

The guidelines for student paper setup are described and shown using annotated diagrams in the Student Paper Setup Guide (PDF, 3.40MB) and the A Step-by-Step Guide to APA Style Student Papers webinar . Chapter 1 of the Concise Guide to APA Style and Chapter 2 of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association describe the elements, format, and organization for student papers. Tables and figures are covered in Chapter 7 of both books. Information on paper format and tables and figures and a full sample student paper are also available on the APA Style website.

Basic setup

The guidelines for basic setup apply to the entire paper. Perform these steps when you first open your document, and then you do not have to worry about them again while writing your paper. Because these are general aspects of paper formatting, they apply to all APA Style papers, student or professional. Students should always check with their assigning instructor or institution for specific guidelines for their papers, which may be different than or in addition to APA Style guidelines.

Seventh edition APA Style was designed with modern word-processing programs in mind. Most default settings in programs such as Academic Writer, Microsoft Word, and Google Docs already comply with APA Style. This means that, for most paper elements, you do not have to make any changes to the default settings of your word-processing program. However, you may need to make a few adjustments before you begin writing.

Use 1-in. margins on all sides of the page (top, bottom, left, and right). This is usually how papers are automatically set.

Use a legible font. The default font of your word-processing program is acceptable. Many sans serif and serif fonts can be used in APA Style, including 11-point Calibri, 11-point Arial, 12-point Times New Roman, and 11-point Georgia. You can also use other fonts described on the font page of the website.

Line spacing

Double-space the entire paper including the title page, block quotations, and the reference list. This is something you usually must set using the paragraph function of your word-processing program. But once you do, you will not have to change the spacing for the entirety of your paper–just double-space everything. Do not add blank lines before or after headings. Do not add extra spacing between paragraphs. For paper sections with different line spacing, see the line spacing page.

Paragraph alignment and indentation

Align all paragraphs of text in the body of your paper to the left margin. Leave the right margin ragged. Do not use full justification. Indent the first line of every paragraph of text 0.5-in. using the tab key or the paragraph-formatting function of your word-processing program. For paper sections with different alignment and indentation, see the paragraph alignment and indentation page.

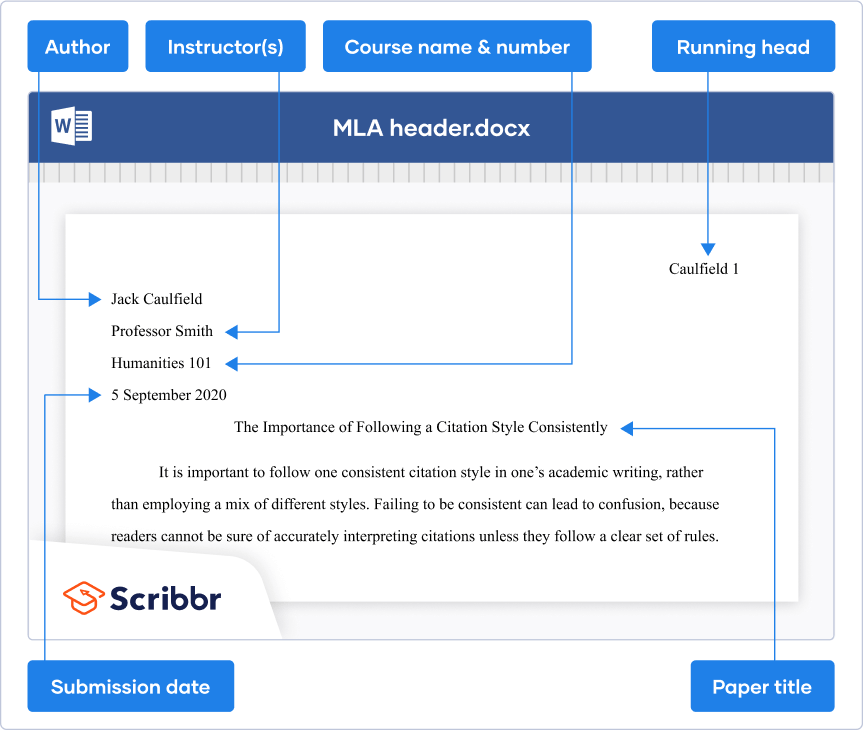

Page numbers

Put a page number in the top right of every page header , including the title page, starting with page number 1. Use the automatic page-numbering function of your word-processing program to insert the page number in the top right corner; do not type the page numbers manually. The page number is the same font and font size as the text of your paper. Student papers do not require a running head on any page, unless specifically requested by the instructor.

Title page setup

Title page elements.

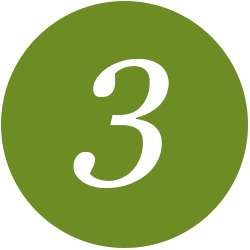

APA Style has two title page formats: student and professional (for details, see title page setup ). Unless instructed otherwise, students should use the student title page format and include the following elements, in the order listed, on the title page:

- Paper title.

- Name of each author (also known as the byline).

- Affiliation for each author.

- Course number and name.

- Instructor name.

- Assignment due date.

- Page number 1 in the top right corner of the page header.

The format for the byline depends on whether the paper has one author, two authors, or three or more authors.

- When the paper has one author, write the name on its own line (e.g., Jasmine C. Hernandez).

- When the paper has two authors, write the names on the same line and separate them with the word “and” (e.g., Upton J. Wang and Natalia Dominguez).

- When the paper has three or more authors, separate the names with commas and include “and” before the final author’s name (e.g., Malia Mohamed, Jaylen T. Brown, and Nia L. Ball).

Students have an academic affiliation, which identities where they studied when the paper was written. Because students working together on a paper are usually in the same class, they will have one shared affiliation. The affiliation consists of the name of the department and the name of the college or university, separated by a comma (e.g., Department of Psychology, George Mason University). The department is that of the course to which the paper is being submitted, which may be different than the department of the student’s major. Do not include the location unless it is part of the institution’s name.

Write the course number and name and the instructor name as shown on institutional materials (e.g., the syllabus). The course number and name are often separated by a colon (e.g., PST-4510: History and Systems Psychology). Write the assignment due date in the month, date, and year format used in your country (e.g., Sept. 10, 2020).

Title page line spacing

Double-space the whole title page. Place the paper title three or four lines down from the top of the page. Add an extra double-spaced blank like between the paper title and the byline. Then, list the other title page elements on separate lines, without extra lines in between.

Title page alignment

Center all title page elements (except the right-aligned page number in the header).

Title page font

Write the title page using the same font and font size as the rest of your paper. Bold the paper title. Use standard font (i.e., no bold, no italics) for all other title page elements.

Text elements

Repeat the paper title at the top of the first page of text. Begin the paper with an introduction to provide background on the topic, cite related studies, and contextualize the paper. Use descriptive headings to identify other sections as needed (e.g., Method, Results, Discussion for quantitative research papers). Sections and headings vary depending on the paper type and its complexity. Text can include tables and figures, block quotations, headings, and footnotes.

Text line spacing

Double-space all text, including headings and section labels, paragraphs of text, and block quotations.

Text alignment

Center the paper title on the first line of the text. Indent the first line of all paragraphs 0.5-in.

Left-align the text. Leave the right margin ragged.

Block quotation alignment

Indent the whole block quotation 0.5-in. from the left margin. Double-space the block quotation, the same as other body text. Find more information on the quotations page.

Use the same font throughout the entire paper. Write body text in standard (nonbold, nonitalic) font. Bold only headings and section labels. Use italics sparingly, for instance, to highlight a key term on first use (for more information, see the italics page).

Headings format

For detailed guidance on formatting headings, including headings in the introduction of a paper, see the headings page and the headings in sample papers .

- Alignment: Center Level 1 headings. Left-align Level 2 and Level 3 headings. Indent Level 4 and Level 5 headings like a regular paragraph.

- Font: Boldface all headings. Also italicize Level 3 and Level 5 headings. Create heading styles using your word-processing program (built into AcademicWriter, available for Word via the sample papers on the APA Style website).

Tables and figures setup

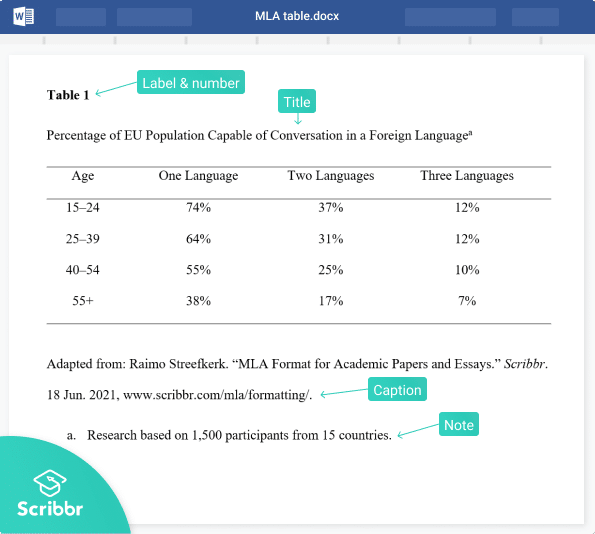

Tables and figures are only included in student papers if needed for the assignment. Tables and figures share the same elements and layout. See the website for sample tables and sample figures .

Table elements

Tables include the following four elements:

- Body (rows and columns)

- Note (optional if needed to explain elements in the table)

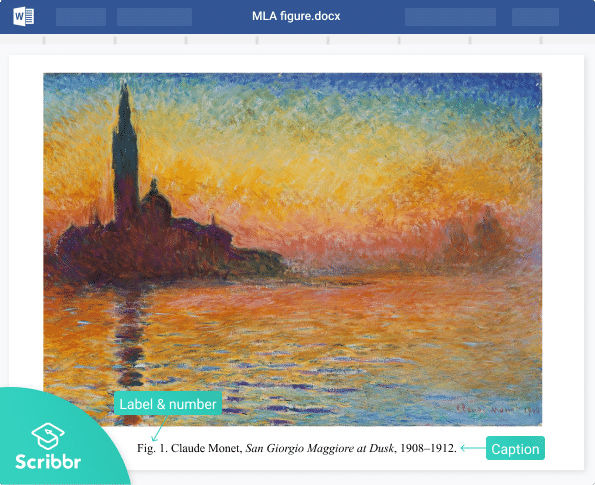

Figure elements

Figures include the following four elements:

- Image (chart, graph, etc.)

- Note (optional if needed to explain elements in the figure)

Table line spacing

Double-space the table number and title. Single-, 1.5-, or double-space the table body (adjust as needed for readability). Double-space the table note.

Figure line spacing

Double-space the figure number and title. The default settings for spacing in figure images is usually acceptable (but adjust the spacing as needed for readability). Double-space the figure note.

Table alignment

Left-align the table number and title. Center column headings. Left-align the table itself and left-align the leftmost (stub) column. Center data in the table body if it is short or left-align the data if it is long. Left-align the table note.

Figure alignment

Left-align the figure number and title. Left-align the whole figure image. The default alignment of the program in which you created your figure is usually acceptable for axis titles and data labels. Left-align the figure note.

Bold the table number. Italicize the table title. Use the same font and font size in the table body as the text of your paper. Italicize the word “Note” at the start of the table note. Write the note in the same font and font size as the text of your paper.

Figure font

Bold the figure number. Italicize the figure title. Use a sans serif font (e.g., Calibri, Arial) in the figure image in a size between 8 to 14 points. Italicize the word “Note” at the start of the figure note. Write the note in the same font and font size as the text of your paper.

Placement of tables and figures

There are two options for the placement of tables and figures in an APA Style paper. The first option is to place all tables and figures on separate pages after the reference list. The second option is to embed each table and figure within the text after its first callout. This guide describes options for the placement of tables and figures embedded in the text. If your instructor requires tables and figures to be placed at the end of the paper, see the table and figure guidelines and the sample professional paper .

Call out (mention) the table or figure in the text before embedding it (e.g., write “see Figure 1” or “Table 1 presents”). You can place the table or figure after the callout either at the bottom of the page, at the top of the next page, or by itself on the next page. Avoid placing tables and figures in the middle of the page.

Embedding at the bottom of the page

Include a callout to the table or figure in the text before that table or figure. Add a blank double-spaced line between the text and the table or figure at the bottom of the page.

Embedding at the top of the page

Include a callout to the table in the text on the previous page before that table or figure. The table or figure then appears at the top of the next page. Add a blank double-spaced line between the end of the table or figure and the text that follows.

Embedding on its own page

Embed long tables or large figures on their own page if needed. The text continues on the next page.

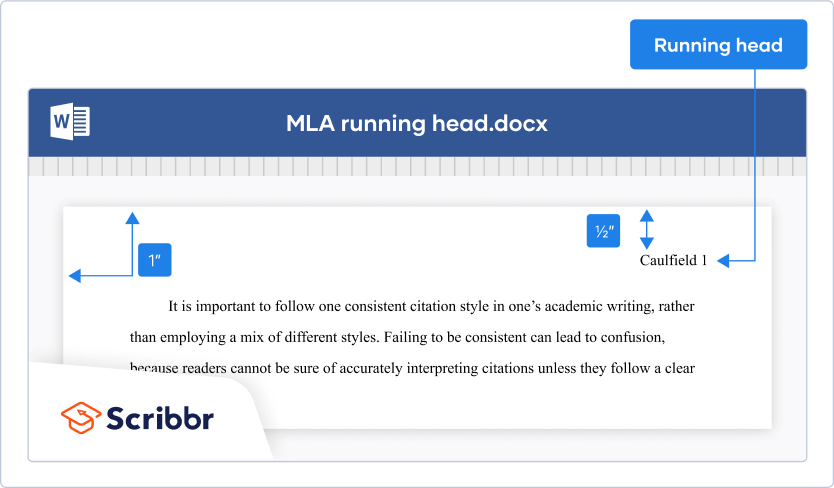

Reference list setup

Reference list elements.

The reference list consists of the “References” section label and the alphabetical list of references. View reference examples on the APA Style website. Consult Chapter 10 in both the Concise Guide and Publication Manual for even more examples.

Reference list line spacing

Start the reference list at the top of a new page after the text. Double-space the entire reference list (both within and between entries).

Reference list alignment

Center the “References” label. Apply a hanging indent of 0.5-in. to all reference list entries. Create the hanging indent using your word-processing program; do not manually hit the enter and tab keys.

Reference list font

Bold the “References” label at the top of the first page of references. Use italics within reference list entries on either the title (e.g., webpages, books, reports) or on the source (e.g., journal articles, edited book chapters).

Final checks

Check page order.

- Start each section on a new page.

- Arrange pages in the following order:

- Title page (page 1).

- Text (starts on page 2).

- Reference list (starts on a new page after the text).

Check headings

- Check that headings accurately reflect the content in each section.

- Start each main section with a Level 1 heading.

- Use Level 2 headings for subsections of the introduction.

- Use the same level of heading for sections of equal importance.

- Avoid having only one subsection within a section (have two or more, or none).

Check assignment instructions

- Remember that instructors’ guidelines supersede APA Style.

- Students should check their assignment guidelines or rubric for specific content to include in their papers and to make sure they are meeting assignment requirements.

Tips for better writing

- Ask for feedback on your paper from a classmate, writing center tutor, or instructor.

- Budget time to implement suggestions.

- Use spell-check and grammar-check to identify potential errors, and then manually check those flagged.

- Proofread the paper by reading it slowly and carefully aloud to yourself.

- Consult your university writing center if you need extra help.

About the author

Undergraduate student resources

APA Style 7th Edition

- Advertisements

- Books & eBooks

- Book Reviews

- Class Notes, Class Lectures and Presentations

- Encyclopedias & Dictionaries

- Government Documents

- Images, Charts, Graphs, Maps & Tables

- Journal Articles

- Magazine Articles

- Newspaper Articles

- Personal Communication (Interviews & Emails)

- Social Media

- Videos & DVDs

- What is a DOI?

- When Creating Digital Assignments

- When Information is Missing

- Works Cited in Another Source

- In-Text Citation Components

- Paraphrasing

- Paper Formatting

- Citation Basics

- Reference List and Sample Papers

- Annotated Bibliography

- Academic Writer

- Plagiarism & Citations

Step-by-Step Guide for APA Style Student Papers

Setting Up and Formatting a Student APA Paper

If your paper will follow strict APA formatting, follow the steps below. Your paper should have three major sections: the title page, main body, and references list. The Publication Manual covers these guidelines in Chapter 2; the APA website also has a Quick Answers--Formatting page.

These guidelines will cover how to set up a student paper in APA format. The 7th edition now has specific formatting for student papers versus a professional paper ( i.e. one being submitted for publication). If your instructor has requested a different format or additional elements, use your instructor's preferences.

Official Resources

- APA Style: Sample Papers

- APA Style: Student Title Page Guide [PDF]

APA Style: Paper Format

1. Set the Margins to One Inch

The margins of the paper should be set to 1" (one inch) all around.

Step-by-Step Directions

- Go to the Page Layout or Layout tab

- Click Margins

- Select the Normal option

2. Set the Spacing to Double

The line spacing for the paper should be set to double (2.0).

- Go to the Home tab

- In the Paragraph box, click the icon that looks like two up/down arrows with text to the right

- Pick 2.0

- Alternate Method: You can also press the Control Key along with the number 2 to quickly double space.

3. Create a Title for Your Paper

Your title should summarize the main topic of your paper. Try not to be too wordy or off-topic. While there is no word limit for titles, "short but sweet" is the goal. The APA Style Blog has further information on titles: Five Steps to a Great Title . Use title case for paper titles.

Example Titles

- Attitudes of College Students Towards Transportation Fees

- Effect of Red Light Cameras on Traffic Fatalities

- Juror Bias in Capital Punishment Cases

4. Add Page Numbers to the Header

Insert the page number in the right area of the header. Use the built-in page numbering system; do not attempt to type each page number manually.

- Go to the Insert tab

- Press Tab once or twice to go to the far right

- Click Page Number

- Click Current Position

5. Create the Title Page

Depending on your instructor's directions, on the first page you may need to include the following information:

- Title of Your Paper

- Florida State College at Jacksonville

- Course Number: Course Name

This information will be centered , and will be a few lines down from the top.

- Go to the top of the first page.

- Press Enter 3-4 times.

- Center your text.

- Type in the title of your paper, in bold .

- Press Enter twice, in order to have one blank line between the title and the next element.

- On the next line, type your full name.

- On the next line, type Florida State College at Jacksonville.

- On the next line, type your course number, a colon, and your course name.

- On the next line, type your instructor's name.

- On the next line, type the due date of the paper.

6. Set Up the References List

The references list should be on a new page, and should be the last section of your paper.

Heading of Reference List

The heading at the top of the reference list should say References at the top ( not Bibliography or Works Cited, unless your instructor tells you otherwise) and bolded .

Hanging Indent

All reference lists should have a hanging indent. An example of a hanging indent is shown below:

George, M. W. (2008). The elements of library research: What every student needs to know . Princeton University Press.

To create a hanging indent in Word, you can press the Control key along with the letter T .

Line spacing in the reference list should be set to double (2.0).

Alphabetizing

When organizing your references list, you must alphabetize your references. Generally, you will organize by the author's last name. Go letter by letter and ignore spaces, hyphens, punctuation etc.

If a work has no author, use the title to alphabetize. You will use the first significant word to alphabetize; this means you skip words like the, a, and an.

Example of Proper Order:

- Alcott, L. M. (1868)...

- Alcott, L. M. (1893)...

- Anonymous. (1998). Beowulf ...

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017).

- Etiquette in Florida. (n.d.).

- Grammar Girl. (2009, May 21)...

- Johnson, C. L., & Tuite, C. (Eds.). (2009)...

- Johnson, S. K. (2003)...

- Oxford English dictionary (2nd ed.). (1989)...

- A prescription for health care. (2009). Consumer Reports ...

- Southeast Asia. (2003). In The new encyclopaedia Britannica ...

Source: Publication Manual , 2.12; 9.44-9.49

But What About...?

APA does not specify a specific font or size, just that it must be legible. Their only guidelines is that the same font should be used throughout the paper. Some suggestions are 11-point Calibri, 11-point Arial, 10-point Lucida Sans Unicode, 12-point Times New Roman, and 11-point Georgia.

If your instructor has specified a font or font size, follow those guidelines.

Source: Publication Manual , 2.19

The Running Head?

Student papers do not need a running head.

Source: Publication Manual , 2.8; 2.18

- << Previous: Formatting

- Next: Citation Basics >>

- Last Updated: Mar 4, 2024 1:55 PM

- URL: https://guides.fscj.edu/APAStyle7

Writing Center

Completing an Academic Writing Project

Step by Step

UNDERSTANDING AN ASSIGNMENT

Before getting started, it's usually a good idea to consider where you want to go and how you want to get there. Consider these questions before you continue to step two.

A. Do you know when your assignment is due, and do you understand the basic guidelines of the assignment?

B. Do you understand the purpose or goals of the assignment?

C. Do you understand who the audience of this assignment is, and do you know how to appropriately address them?

A. Understanding the Basic Guidelines of an Assignment

Read your assignment and class notes carefully and see if you can answer these questions:

- When is my assignment due?

- What is the word or page requirement?

- Do I need to do any research for this assignment? If so, how many sources are required and what type of sources must they be? For example, some instructors will only accept research taken from peer-reviewed journals, while others may have certain restrictions concerning Internet sources. (If this is all sounding very mysterious to you, stay tuned; you'll find more help with research in Step 4: Research. )

- Do I need to use specific style guidelines, such as MLA, APA, or Chicago?

Return to the Step One Questions

B. understanding the purpose or goals of an assignment.

Reading Assignments for Keywords

Once you understand the basic requirements of an assignment, the next step is to carefully and critically reread the assignment sheet and circle key words that will help you understand the instructor's expectations. It's especially helpful to circle key ideas from the course, or verbs like analyze , compare , interpret , evaluate , or explain . The circled ideas should help you understand what concepts from the course are particularly important, and the circled verbs will help clarify what you are supposed to do with those concepts.

Does the assignment call for a discipline-specific form? Does it ask for material to be addressed in a certain order, i.e. a lab report, literature review, position paper, or an essay with an intro, body, and conclusion?

Talking With Instructors About Assignments

If there are any terms or ideas in your assignment that are unfamiliar or confusing to you, don't be afraid to ask your instructor for help. Most instructors are happy to help you out, especially if you come to them well ahead of any deadlines. Professors keep office hours for a reason—use them!

C. Understanding and Addressing Audience

Before you get started on your paper, make sure you understand who your audience is, and consider what type of "voice" and evidence you should use to address that audience. This is not as daunting a process as it may seem. All writers make decisions about what written voice is appropriate for a particular piece of writing; in an email to your BFF (or best friend), you would most likely use different vocabulary, discuss different topics, and maybe even construct your sentences differently than you would in a letter to your granny.

Rather than making an abstract decision about what constitutes a "correct voice," it will often be easier for you to consider what you know about the intended audience, and then write accordingly. What does the audience care about? What are they are familiar with? What kind of language do they use? And what is your purpose in communicating with them? Is it to show you read the text, can apply a concept to a real-life situation, or to convince them of something?

If you were to write an email to a friend about a movie you'd recently seen, called "Night of the Kilbot" for instance, it's appropriate to use a casual tone and your personal opinion to persuade her she ought to see the movie. When you are writing a formal paper in a university setting, the written voice shifts again. Your immediate reader will obviously be your instructor, but references to a specific reader in a personal or casual voice ("I don't know if you know what the KilBots did next, Prof. Smith, but it was so awesome that the scientific community could only say, 'Oh, snap!'") sound odd and aren't appropriate. This is because the assumed audience for college writing isn't a single person, but really a larger body of educated readers—people who know enough about your topic to grasp your thesis and evidence. And this educated audience values evidence over opinion (examples, statistics, logical lines of reasoning). The written voice that results from assuming this audience is what most people call "academic voice."

A university paper about a film, then, might be expected to include discussion of visual composition, use of terms like "mise-en-scene," or thoughtful analysis of artificial intelligence. The voice might sound something like:

The robots' search for acceptance on an unfamiliar planet creates a sense of pathos in the viewer, though the surprising complexity of the film's androids stands in direct contrast to the one-dimensional performances of the human players.

Writing for an academic audience might require some extra attention at first, and small adjustments might need to be made based on what field you're writing about. (Some fields are okay with the use of "I" in a formal paper, for instance, but others aren't.) In time, however, writing in an appropriate academic voice becomes more natural, and an ability to analyze what's appropriate for your audience can often help you figure out how to phrase thoughts clearly and effectively in any piece of writing.

Return to the List of Steps

FINDING A TOPIC

Once you understand your assignment, the next step is finding a strong topic. Make sure these statements about your topic are true before you continue to step three.

A. I know what I want to write about.

B. My idea fits the assignment.

C. My idea interests me.

A. Coming Up With a Topic You Want to Write About

Before you begin writing your first draft, you have to have an idea, right? This work you do before the rough draft is called "pre-writing," and it helps you find ideas you didn't even know you had. Here are a few brainstorming/pre-writing techniques :

Listing is… making a list. It's worth your time to spend 15 minutes making a list of ideas at the very beginning of your writing process. Think about how many brands of cold cereal supermarkets have. Try to get that many ideas out on paper before you even think about narrowing your topic down. After you've printed your list, circle the 3-5 most interesting or important ones. Use those ideas you've circled with the following tactics.

If you're a visual person, try clustering . It's like free association. Write your main idea down in the center of your paper, then draw a circle around it. That's like your solar system's sun. Now, write your topics around it, like planets. Each of these topics can have things related to them—your own opinions, interesting points, whatever—so write those little things around the planets. Those little things are the moons and satellites. Now, stand back and look at your paper's solar system. Whichever planet looks the most interesting to you (it might be the one with the most moons and satellites) could be your topic.

Freewriting

Once you have an idea or two, start freewriting . Don't worry about logic, grammar, or spelling; just get your ideas out on paper. Give yourself a goal, like "fill one page," and stop when you've reached it. Finally: read your work, and decide which of the things you wrote interest you most.

After a ten-minute freewrite, circle the most important or interesting sentence you've written. Copy this sentence at the top of a new sheet of paper, and freewrite again based on that sentence. This is kind of like zooming in on one neighborhood using Google Maps, and it lets you get into depth and detail before you even start working on your rough draft. Repeat as many times as you like.

Focused Surfing

Unlike regular Web surfing, which is a way to waste time while procrastinating, focused surfing is early research. The trick is to keep a word processing document open while you're surfing. That way, you can write down your reactions to things you read on the Web. Be careful if you do this, because sometimes people copy ideas they've seen online without even realizing that they're doing it, and this can lead to unintentional plagiarism . To avoid this, don't cut-and-paste text from the sites you're visiting. Make yourself summarize, in your own words, what is important or useful about this site. Also: keep a list in your new document of the sites you visit. You'll need the accurate site name and online address later, so you might as well note it now.

Talking About It

When you're at work or hanging out, talk about the things you're studying in class. Don't talk about the other students or the teacher or your grade; talk about the things you're reading and studying. Maybe the person you're talking to will have some strong opinions about them. If you agree or disagree with whomever you're talking with, that might be a good topic to write about. After all, if you get stuck or bored, you can always just call your friend up and start the conversation again.

Return to the Step Two Questions

B. making sure your topic fits the assignment.

If you're not sure your topic fits the assignment, the best way to confirm this is to check the tips in Step One: Understanding an Assignment .

C. Using Class Notes and Readings to Come Up With Topics That Interest You

When surfing the Web for school, remember your general subject. This sounds obvious, but the Internet has a way of getting people off track. Here's a trick: Write your general subject area, like "nurses in the US Civil War" on a sticky note, and attach that note to the frame of your computer screen. Looking at that note occasionally will help keep you on track. In addition, keep a word-processing file open on your computer while you surf, and note interesting sites on a new document. That way, you'll remember where you found everything interesting.

Using a Reading Journal

If you've taken notes during any classes, or written any response papers, or taken any reading quizzes, or written anything in the margins of your class readings… this is a great time to look over those things. If you've kept notes on your class readings in a separate notebook (a reading journal), check that too. If you see anything in there that interests you—anything that doesn't make sense, or that really makes sense, or that touches on something you think you might want to do if you ever get out of college—write that down on a fresh sheet of paper. Now try the brainstorming topics listed above.

Developing Your Argument

If you know what your assignment requires and you know what topic you'd like to write about, your next step is to develop your argument. You might start by writing a "working thesis statement" that you can adjust or change as you research and write. It’s sort of like making a plan for the weekend on Tuesday night: you know the plan will probably be modified, but it’s a good place to start. Make sure you can confidently respond to each of these statements before moving on to step four.

A. My assignment requires an argument or thesis statement.

B. My argument includes a clear topic and an assertion about that topic.

C. My argument or thesis statement is a debatable claim.

D. My argument can be supported with logic and evidence.

A. Figuring Out if Your Assignment Requires an Argument or Thesis Statement

Not all writing assignments require a formal thesis statement, but most do. It is important to read over your assignment carefully to determine if your assignment would benefit from having one. Remember, a thesis statement is just a fancy phrase for the main point of your paper. Nearly all types of academic writing need a central direction or point. Even if you plan on using many different kinds of examples, anecdotes, or pieces of evidence, you will want to make sure to bring them together under a clearly stated thesis statement somewhere in the beginning of your paper. There are some foreseeable projects that might not require a formal thesis statement—such as an informal reflection essay or a piece of fiction writing—but it is very likely that even the most informal of writings would do better in having at least a topic sentence outlining or hinting at the main direction of the paper.

Return to the Step Three Questions

B. what makes for a good working thesis or provisional argument, the idea of a working thesis.

A thesis statement is the main point or assertion of your paper. A working thesis is just a thesis that isn't quite sure of itself yet. You, the author, are still working out where you want your paper to go. You might be perfectly confident about your topic—that is, generally you know what you want to write about—but you still might not be sure how you want to deal with it or what direction you want to take that topic. A working thesis is just a thesis in a sort of rough draft form. It's not final or complete. It may be lacking focus or a debatable claim, or a combination of both.

Should I worry about only having a working thesis?

No, not necessarily. Often, it can be useful to have a general thesis to start out with simply so you can feel free to charge ahead and begin writing on your topic. An unrefined thesis usually occurs when you haven't spent enough time exploring the complexities of your topic. Simply writing about your topic can help determine the main focus of your paper.

How can I tell if my thesis is in good shape or is still in the working stages?

The best way to know if your thesis is still in the working stage is to "grill it," that is, interrogate or question every single word of the thesis and determine if each word is sufficiently specific and meaningful. Assault your thesis with a barrage of questions, asking what , who , where , when , and why . To some degree, your thesis should answer all of these questions. If you find it doesn't, then you know you still have some work to do. Don't worry; many writers do not discover their true, final thesis until after finishing their first full draft.

The importance of a thesis containing both a topic and an assertion

As mentioned, for your working thesis to attain the status of a thesis statement, it must possess both a topic and an assertion about that topic. In other words, you must put forth a debatable argument about your topic.

For example, an incomplete thesis might look something like this:

A wolverine's claws are useful in defending themselves.

That statement might make for a good starting topic but it does not really assert anything that is debatable or interesting. Turning that topic into a thesis could look like this:

A wolverine's claws are quite sharp and consequently help the animal defend itself from predators.

Here, the writer mentions both a topic (a wolverine's claws and self-defense against predators) and an assertion (a wolverine's claws are quite sharp and help defend it from predators). However, as we will see in part three, the above thesis could be stronger with a more debatable assertion or claim.

C. The Importance of a Thesis Making a Debatable Claim

A truly debatable assertion makes for a stronger argument.

A thesis must not only make an assertion about the topic; it must make a debatable or controversial claim about the topic. The example in the previous detail section (What is a working thesis?) about wolverines possesses the two key ingredients of a thesis, but its assertion is boring and rather obvious. A stronger thesis might state:

Not only are a wolverine's claws the sharpest and most deadly of any species classified within the Mustelidae family, they use these claws in self-defense against a dozen various predators found in its home ecosystem.

This thesis statement makes a much more debatable claim—"the wolverine's claws are the sharpest and most deadly of any species classified within the Mustelidea family."

Arousing suspicion or intellectual interest in the reader

If an assertion is debatable enough, a reader might question its accuracy. A strong thesis should arouse at least a little of this skepticism in its reader, which in turn might be proof that the thesis author is claiming something interesting and worth debating. Regarding our example, a reader might wonder: Even if a wolverine's claws are somehow the sharpest, does that make them automatically the deadliest?

D. A Thesis Must be Supportable with Logic and Evidence

The paragraphs that follow your thesis should be full of support, e.g. examples, anecdotes, or evidence. Additionally, each paragraph should link back up to your thesis statement in a logical way. If after examining your working thesis you find that evidence or logic can't be used to support it, then your thesis is probably too opinion based.

Now that you have a topic and an argument or a working thesis, you'll want to do some research to find out what others have said or written about your topic. There are many approaches to research, and a vast number of methods for finding information. You should also keep in mind any requirements or expectations your instructor has for the research part of your assignment. Consider these statements about research before moving to the next step.

A. I have familiarized myself with my topic in general, noting helpful resources.

B. I have found a sufficient number of sources that deal specifically with my topic.

C. My sources fit my instructor's guidelines.

D. My sources do not all hold exactly the same opinion, or repeat the same information.

E. I have explored sources that do not agree with my argument.

A. Familiarizing Yourself With Your Topic

Familiarizing yourself with doing research and learning the basics of your topic can be a great place to start. Need to review how to begin researching? Check out the PSU Library’s DIY Research Guide .

Backgrounding

Look through more general sources such as encyclopedias or articles giving subject overviews. You can turn to the web for basic information on sites like Wikipedia, but be sure you use those kinds of sites primarily as starting points that lead to more specific sources.

Keeping Track of Sources

Make it easier on yourself later by keeping a running log of materials you have looked through (including websites). If you do this ahead of time, you will not be scrambling backwards to create your Works Cited/References/Bibliography page. Nobody wants to be accused of plagiarism (see item E in Step 9: Checking Your Use of Research ). For help with proper citation, drop by the Writing Center or schedule an appointment with a tutor.

Stay Organized

Some folks prefer a more organized approach to research using notecards while others work best by highlighting texts or dog-earing helpful pages. However you do your research, make sure you know what information you want to use from each source and where to locate it.

Return to the Step Four Questions

B. locating a diverse array of sources.

Locating a good number of sources can be one of the toughest parts of doing research, but also one of the most fun and interesting. Try following the steps outlined below:

Spread Your Reach

Look to source lists from your background materials. These may point to important work in the field. Or, talk to someone in the know. This may be your instructor or classmates, or it may mean contacting a professional in the field. Try to do some brainstorming on your own:

- Ask the Journalist's Questions (who, what, where, when, how, and why) to better orient yourself within your topic; this will help you determine where to look.

- Using basic internet search engines ( Google , Bing , Yahoo , etc.), you may be able to discover additional avenues to go down. In the process, you may come across references to sources to track down in the library.

Research at the Library

Though we live in an increasingly electronic world, in which research is done on Internet databases and the results are kept in electronic form, a good university library is still the primary site for doing effective research:

- The PSU Library offers many services to students looking to survive the world of academia. Plus, utilizing library resources proves an invaluable element of varying sources.

- Communicate with librarians directly over the phone or internet with Ask Us! .

- You can also walk over to the 2nd floor of Millar Library and talk to the helpful folks at the Research Desk.

- Or schedule a one-on-one meeting with a librarian familiar with your subject area.

- Surf to the library's Where to Search page for information on different resources.

- Browse pages tailored for specific classes listed at Course Guides .

C. Paying Attention to Specific Guidelines

Specific guidelines or requirements from your instructor can be used to direct your research, saving you time while helping you fulfill the assignment. In evaluating sources, you must be critical in discerning the credibility, reliability, accuracy of any given source. Ask basic questions of a source:

- What type of source is it (print, database, electronic media, etc.)?

- Who is the author? What credentials do they have? Where have they been published? Are they a scholar or professor associated with a respected, reputable institution?

- How current is the source? When was it published, and where?

- Who is the intended audience?

- Is the source primary or secondary? Is it current in the field or discipline?

- Does it suit your needs? Will it lend support and credence to your own project (essay, thesis, dissertation, freelance article, etc.)?

Use reliable resources by asking these questions when choosing where to turn for information:

- Is it current? Publication dates of quality sources are easily identifiable, and as a general rule, you want to look at the most recent articles available. These are often journal articles.

- Is it relevant? All information should support your thesis and assertions.

- Is it biased? Web sites, journals and writers also have affiliations with certain organizations and philosophies; these affiliations can affect bias. Before you incorporate a source into your written work, you need to know what its affiliations are and how those affiliations may create bias.

- Is it specific? Sweeping generalizations are to be avoided. Secondary sources using vague language and broad generalizations will adversely affect your arguments and your entire essay. Essays and sources should offer specific evidence and a lot of it.

- Is it authoritative? Reliable sources always have an author and clearly identify an author's experience and education. Many offer a way to contact the author. If you use a source without an author (heaven forbid), the web site or journal should make clear its reasons for publishing the work, as well as a way to contact the author or editor. When you use secondary sources in your essays (1) they should have expertise in their field; (2) their area of expertise should be a legitimate field of study; (3) they should only make claims within the area of their expertise; (4) there should be an adequate degree of agreement among experts; (5) the author should be identified.

D. Varying Sources

Varying sources ensures you produce a paper that stands on more than one leg. In general, try not to rely too heavily on any one source; rather, use the means at your disposal to find an array of strong supports in different areas.

Searching for Books and Materials

In the digital age, every library is actually multiple libraries. If a library doesn't have a book or other source immediately on hand, the item can often be easily borrowed, in physical or electronic form, from another library. A wider selection of materials can be found using Interlibrary Loan resources or through the WorldCat database.

- The Summit Regional Catalog

- ILLiad , or Inter-Library Loan

- The WorldCat Worldwide Database

Browsing Databases for Academic Journals

The library provides access to over 200 premier databases and full-text resources . Google Scholar allows users to use a myriad of search functions while displaying links to comparable or related works. However, you may have to return to the library's databases for full access to some articles found through this site.

Working with the Internet

Beware of online sources. With the onslaught of electronic media, and the Internet in particular, everyone is a pundit, expert, or sudden scholar. Remember that anyone can post online, or put up their own website. Online material is especially mutable and ever-changing. Evaluation of such sources is scant at best. If a source seems suspect or of questionable credibility, confirm the source or information yourself. Using the internet alone in a paper can signal a lack of effort to some instructors. If you are unsure about expectations for your assignment, check with your instructor via a question after class, a quick e-mail, or a phone call. Consider your use of popular sources versus scholarly or academic sources. You may be able to find information comparable to a site of questionable authorship through the library's resources.

Supporting Your Assertions with Data

From time to time it will be necessary to use quantitative data in your papers. After you have collected your data you will need to communicate it to your readers. Below are some tips for making that communication effective:

- Be selective —choose carefully how to display quantitative data and where in your paper it is appropriate to include the information.

- Be clear —provide enough information in a chart, graph, or table that it can be read and understood on its own. When including multiple pieces of data in visual form be consistent in your presentation.

- Discuss —refer to your data in the text of your paper, but don’t just repeat the facts and figures. In the text, your job is to expand on the information, put it in context, and support the claims you are making in your paper.

- Look again —review the work you have done with quantitative data.

Using Non-Print Sources

Interacting with non-print sources can be as daunting as it may be intriguing. Interviews may be useful and appropriate for some assignments. If so, ask pertinent, probing questions. Keep good notes or use a recorder to ensure you present your contact’s sentiments honestly. Audio/Visual sources open a whole new can of worms for good…or evil. Be careful when working with films, podcasts, recordings, and the like that may be interesting, but may not be appropriate for your piece. If you end up using an A/V source, refresh yourself on the ways to incorporate such quotes in your paper.

E. Exploring Contrary or Differing Ideas

Exploring contrary or differing ideas generally makes your paper stronger. Showing you have considered alternatives to your own point of view, just like varying sources , indicates a higher level of critical thinking to your reader(s). Speculating about how others may view your ideas or issues will improve your ability to prepare for any questions or objections that may enter the reader's mind.

When dealing with texts and sources, never forget to ask critical questions of your resources. A few moments analyzing an issue can lead you to that next brilliant point in your research and writing. While managing differing viewpoints may seem overwhelming, do not be afraid to dig into your topic and find a niche, a home for your idea. Addressing the ideas of readers who disagree with your approach builds another line of defense for your convincing argument. Also, consider other approaches to your specific supports. You may find stronger sources or simply more diverse ideas that improve the soundness of your work.

Organizational Planning

After generating ideas, developing a working thesis, and doing some research, most writers come up with some kind of organizational plan before they write a draft. The plan can be modified, but without at least some sense of organization, starting can be difficult. Have you organized your ideas and research into an organizational plan? Check to see if these statements are true for you.

A. I have finished my research, but can’t decide where to begin.

B. I have created an effective organizational plan for my first draft.

C. I have double-checked my organizational plan, and it is comprehensive.

D. My organizational plan is complete. I'm ready to create a draft.

A. Using an Organizational Plan or Outline to Get Started

Making an organizational plan or outline can help you organize your ideas before you start writing.

What is an outline?

An outline is a tool writers use to organize and examine their thoughts prior to writing them in draft form. Think of it as a map or blueprint for your paper.

How do outlines work?

Outlines work for writers the same way budgets do for entrepreneurs. When looking at a budget an entrepreneur is able to take a step back and see how much money is being spent on each section of their business. A close look at a budget often reveals where a business is losing or making money. Writers design outlines to have the same perspective.

By taking a step back and viewing their ideas in outline form, writers are able to save time by seeing (prior to writing the draft) whether or not their thoughts flow in a clear, logical order and draw the reader to a logical conclusion. A close look at an outline can also help writers catch mistakes such as deviation from the thesis, the addition of unnecessary topics and lack of support.

Outlines are easier to manipulate than drafts and allow writers the ability to shuffle their ideas around until they find the perfect structure for their project or assignment.

Return to the Step Five Questions

B. tips for using outlines effectively.

Outlines come in all shapes and sizes. Choose the structure that works best for you or feel free to make one up on your own. The only rule to remember when writing an outline is to write your thesis at the top so that you can be sure you don't deviate from it.

The nesting method of outlining, which is probably the most traditional, involves putting main ideas, or "headings," in a I, II, III… order with supporting ideas, or "subheads," beneath in an indented i, ii, iii…list. Two popular ways to organize a nest-style outline are by topic and sentence.

Topic Outlines

In a topic outline, the headings are given in single words or brief phrases. Consider the following example:

Thesis: The tradition of bride-kidnapping in Kyrgyzstan has created a culture of fear for the young village women there .

- New York Times story of Jyldyz' escape.

- Statistics of women kidnapped during the day vs. at night.

- Statistics of women polled about being scared of traveling after dark.

Sentence Outlines

In a sentence outline, all the headings are expressed in complete sentences. For example…

- The New York Times ran a story about a sixteen year-old girl named Jyldyz who, after a violent confrontation, narrowly escaped being bride kidnapped while walking home from a neighbor's house at night

- In Kyrgyzstan women are seventy-five percent more likely to be bride kidnapped at night than during the day.

- In a 2003 pew research poll teenage Kyrgyz women said that they were one hundred percent more scared about traveling out at night than during the day because of the potential of being bride kidnapped.

Get Creative with Your Outline

There are as many ways to outline as there are writers. Feel free to be creative. For example you might put all of your topics and pieces of supporting evidence onto notecards, then spread them on the floor and arrange them. Or you might try the clustering method, where you jot down ideas as they come to you and watch for ways to draw them together.

Some writers like the idea tree, where you place a topic at the head of your page and begin "branching" off with supporting ideas and materials then expanding these "limbs" by branching off again and again with more details.

The point of making an outline is to help you organize and structure your thoughts, not hold you to a rigid standard.

C. Double-checking Your Outline for Comprehensiveness

Before you go on to write your draft, recheck your outline one last time:

- Do all of your headings (primary topics/ideas) directly support your thesis?

- Do all of your subheads (topic/idea supports) directly support your heads?

- Try to visualize your outline as a finished paper. Is your information and research presented in the most logical, natural way for your reader to approach? Remember, it is easier to rearrange things now than when you are at the draft stage.

- Did you include any extraneous information that doesn't seem to fit the scope of the project or assignment? If so, lose it now before it derails your paper.

D. Finishing Your Outline: Next Steps

Congratulations on finishing your outline!

When you are writing your draft remember that your outline is malleable—you are not married to it. If something happens during the writing of your paper that makes you break the structure of the outline don't be afraid to go with it. An outline should only be used as a guide, not a law.

Writing a First Draft

In this step we explore how to get words on paper and feel good about them. Though the process of actually composing sentences and paragraphs into a full draft is often shrouded in mystery (or at least not discussed in much detail), most writers keep guidelines like these in mind as they compose a first draft.

A. I have started composing paragraphs with confidence, and I am not hesitating or feeling uncertain about my plan.

B. I am still confident that my topic is a strong one and fits the assignment.

C. I have considered my audience while composing my first draft.

A. Avoiding the Permanent Pause: Thoughts on "Writer's Block"

Many writers suffer at the mercy of the great myth of "getting it right the first time." This myth tells us that the best way to write is "all at once," and ideally (according to this myth), a writer opens a new computer document, composes an introduction, and begins to type one paragraph after the next in an orderly fashion until, upon approaching the length requirement, the writer composes a nice conclusion that ties everything together, hits print, and is done.

This rarely happens. Our thoughts do not often spontaneously spool out in well-stated grammatical sentences arranged in a logical and effective order. The mind associates freely: a thought about computers leads to a thought about a music playlist on your computer, which leads to a thought about a band, which leads to a thought about a concert, which leads to a thought about money, which leads to a thought about things you don’t have, which leads to a thought, strangely, about moon rocks. Or something like that.

Thought may proceed this way, but an essay cannot. So writers often find themselves in a deadlock with that heartless little cursor, struggling to type the next line and feeling that they are lacking direction. If you feel every written word is permanent, it makes sense to pause before writing the next word. And before the next sentence. And, again, before the next paragraph. It becomes dangerously easy, in that frame of mind, to become permanently paused.

But fear not. There is hope.

The next time you begin a new writing project, try thinking about the project as a series of steps that you can start and stop several times, as opposed to completing all of them at once. Knowing that you’re going to let yourself go back and fix things later will keep you from having that "every word I write is set in stone" feeling. Most people write much faster and produce better material when they give themselves the freedom to write a first draft with a few rough edges. A writing project that includes some pre-writing brainstorming, the composition of a draft, some reorganization and fixing, and strategies for straightening things up when you’re done will usually help you write faster, make your writing time feel more productive, and strengthen the quality of your final product.

"Re-visioning" your essay: how writing a rough draft often changes your ideas and focus

The mind associates freely, but an essay cannot. It is true that a final product should not feel like a string of loosely connected combinations of words. But during the writing process itself, this kind of loose connectivity of ideas is perfectly permissible because writing is more than just writing, it is also thinking . Some people even claim that they must write in order to truly understand what they think.

You may start a rough draft with the feeling that you know exactly what you will say in the essay. You may even have a handy outline in which you've detailed all the pertinent points you want to make. An outline is an excellent tool for preparing to draft, and you should use it if it suits your process. But as you start to write, you may find new ideas popping into your mind asking to be heard, ideas that may differ from your original, neatly mapped-out ideas. Since you now know that every word you write is not set in stone, you can be kind to your new ideas, giving them space in your draft and revisiting them with curiosity as you start to revise. Being open to new thoughts that emerge as you write is particularly important because they will often be even better, more precise, analytical or fresh—than any ideas you could have come up with before you started drafting. This is because writing begets deeper thinking, which begets deeper writing, which begets yet deeper thinking…and on and on while serious smartness accumulates.

Practice letting new ideas into your draft, no matter how random or weird they may seem to you at first and no matter how they may deviate from your outline. When it's time to start looking over what you've written, highlight ideas that emerged during the drafting process itself, overlooking (for the moment) ideas that you mapped-out before hand. Can one of your new ideas provide a more fruitful and interesting focus for your essay? Let yourself "re-vision" the possibilities. In your next draft, if you wish, explore them. This step is part of the process we call "Global Revision" because it involves totally re-seeing your essay from the inside out.

Thoughts about why you became disenchanted with your topic

Boredom sets in when we don't give attention to our new ideas. Think about it: new ideas give us a sense of exhilaration, a feeling that our brains are changing and growing. The mind takes pleasure in real learning when surprising connections are made, but it will fall into torpor when it is forced to simply plug data into pre-crafted formulas or to regurgitate existing information. Even when it is difficult, the writing process can be a pleasurable experience because it is a great way to engage in real learning, to alight on new ideas and to stimulate the mind. If you are disenchanted, give yourself the opportunity to create new ideas by revisiting generative invention strategies (do we still have this one?) , or by paying attention to how writing a rough draft often changes your ideas and focus (resource for this?) . Most importantly, keep your mind open to sparks of imagination and creative connections that may help inject excitement into your writing process.

Return to the Step Six Questions

B. thoughts about why your topic might not fit the assignment.

Essays whose topics fail to fit the assignment are usually the victims of misunderstanding. For instance, an instructor may want you to analyze a film, but you take analyze to mean "summarize," and give a detailed plot summary rather than an in-depth interpretation of the film's meanings and messages. Or, you might believe that a research paper should simply report on a topic, rather than also take a position and develop that position through the use of different kinds of evidence. On the other hand, instructors have been known to write confusing or cryptic assignments that simply cannot be understood, not even by other instructors.

The best thing you can do is talk to your instructor, ask questions, and make sure you both have the same ideas about what the assignment should accomplish. If you've already chosen a topic, but aren't sure if it's appropriate, talk to your instructor as soon as possible.

Keep in mind that different disciplines adhere to different writing styles and rules. Misunderstandings might arise if, for instance, you are asked to write a 12-page paper on David Copperfield but only have experience writing plans, memos, and analyses for your business and economics classes. Think of this as an opportunity to practice gaining flexibility in your writing. For example, in this instance you could take the time to look at sample literature essays or to seek out other resources for writing about literature. Also remember to talk to your instructor and visit the Writing Center for guidance.

In each case, understanding the assignment as your instructor intended it to be understood is essential for choosing an appropriate topic. Make sure you have a firm grasp on this part of the writing process before you invest too heavily in any topic.

C. Thinking About Audience While Composing a Rough Draft

Many writers run into problems in their rough drafting process when they try to force their writing to sound "academic" right off the bat. If you worry excessively about sounding academic you might find yourself too intimidated to write, and/or too beholden to "academese," a kind of stilted, overly-formal writing that is neither clear nor easy to read. In a rough draft of an academic essay it's not necessary to write in an academic voice, even if the final draft will strive for it. Instead, in a rough draft, try writing in whatever voice makes it easiest for you to get your ideas onto paper. Then, as you revise, you can adjust your voice.

For instance, if you are writing a film analysis and you are having trouble conveying your ideas in a sophisticated way, you might first try writing it as if you were addressing a friend in an email:

So like a million people, I went and saw "Night of the KilBot" last weekend. The alien robots were awesome!!! But the acting was ridiculous, and there's no way Scarlett Johansson could conquer a Bone-Krushing KilBot using only a re-wired curling iron. Whatever!

The voice there is perfectly appropriate for a casual email to a friend, and the opinions are clear. When you begin the global revision process, highlight and then transform these kinds of phrases to address your intended audience.

For a formal paper in a university setting, your immediate reader will obviously be your instructor, but the assumed audience for college writing is really a larger body of educated readers—people who know enough about your topic to grasp your thesis and evidence. The written voice that results from assuming this audience is what most people call "academic voice."

For revision, you might transform your previously informal phrase about Night of the KilBot into something that sounds more academic, like this:

Expanding and Improving Ideas

There are few things in the world that can be done perfectly on the first try. It's normal, and probably good, for the first draft of a piece of writing to have elements that can be worked on, and successful writers craft strong pieces of writing by revising many, if not all, aspects of their first drafts. Looking at your own draft, check for these elements.

A. My rough draft includes a strong introduction.

B. My paragraphs have a clear focus, adequate development, and specific purpose.

C. The ideas in my draft are fully developed and don’t need to be expanded or refined.

D. My rough draft includes a strong conclusion.

A. Writing a Strong Introduction

Introductions are a lot like first impressions: terribly important and fairly irrevocable. A good introduction will set the tone of your piece and help the readers know what to expect in the coming pages.

A strong introduction should:

- Grab and engage the reader

- Act as a map for the reader by letting them know the direction the paper will take

- Establish the tone of the paper

If you have already written a draft introduction but find that you are bored, frustrated, or confused by it, try taking one of the following approaches:

Direct Statement of Fact

Often, writers spend too much time in their introductions "warming up." Beginning your paper with a direct statement of fact is helpful because it requires you to be short and to the point, which is often what readers are looking for.

The Surprising Statement

Sometimes simply using the direct statement of fact method can be boring. If you really want to grab a reader's attention you can try hooking them with a surprising statement.

The Anecdote

An anecdote is a short, interesting story. Beginning your paper with an anecdote that is relevant to your topic is another interesting way to lead your reader in.

A humorous quote or statement can liven up an introduction and get the reader excited about reading your piece. Remember, always be aware of your audience and subject matter when choosing what tone to use in your paper. Some readers expect serious writing and some subjects aren't laughing matters.

Reflection/Questions

Writing, particularly the type you will see in college, generally seeks to answer a question of some kind. Many writers find it effective to simply pose the question in their introduction.

Return to the Step Seven Questions

B. sharpening paragraphs.

In refining your essay, it is important to pay attention to what work each paragraph is doing for your paper and how you've broken up your paragraphs. Take a closer look at each of your paragraphs and make sure they all have a clear focus or main idea, as well as a specific purpose in your paper.

How to organize a paragraph

First of all, a paragraph should usually be about one thing. The easiest way to make sure your paragraph has a clear, single focus is to include a topic sentence at the beginning of the paragraph that states the main idea. The rest of the sentences in the paragraph should develop, support, or elaborate upon the main idea stated in the topic sentence. This might involve:

- Discussing examples, details, facts, or statistics

- Using quotes and paraphrased material from sources

- Examining and evaluating causes and effects

- Defining or describing terms

When to start a new paragraph

Just as a speaker who rambles for a long time without pausing soon becomes difficult to follow, if your whole paper is one long paragraph, your reader might get confused or give up. Some reasons to begin a new paragraph include:

- To show you're switching to a new idea

- To signal a change in time or place

- To move to the next step in the process

- To introduce a new source or alternate opinion

When each paragraph focuses on one thing, the content becomes easier for the audience to read, follow, and understand.

The purpose of a paragraph

The basic purpose of each paragraph in your paper is to support your thesis. No matter how beautifully written and logically constructed, a paragraph that does not in some way help you defend the main assertion of your paper probably does not belong. If it doesn't fit, you must omit.

Look closely at each paragraph in your essay and ask yourself, "What does this paragraph do for my paper?" You should be able to sum up the purpose of each paragraph in a single sentence, such as "Gives a specific example of the problem," "Addresses an opposing viewpoint," or "Presents statistics that support my thesis." If you can't describe what a paragraph does, or if a paragraph does something that may not be relevant to your thesis, you need to consider whether or not that paragraph truly belongs in your paper.

C. Getting More From Existing Ideas: Expanding and Refining