- Our Mission

Tips for Guiding Students to Think Creatively

These simple creativity challenges can encourage students to have the mindset of an artist, a designer, and a change-maker.

We’re living in an era when the thinking process is becoming increasingly more important in a student’s learning journey: the ability to be reflective, adaptable, flexible, and nimble during times of constant change.

While an answer, statistic, or other random “product” can be found by simply asking the ever-growing breadth of artificial intelligence options, the process of creative and critical thinking cannot.

How might we shift toward a culture of thinking that’s process oriented in our learning spaces? What types of thinking would be most beneficial during a constant state of flux? Here are three ways of thinking that can help prepare students for career, life, and, most important, humanity.

Thinking like an artist

In a world that’s moving at breakneck speed, thinking like an artist is about slowing down to uncover the nuance, complexity, and emotion of the world around us. Thinking like an artist is about developing the skills for meaningful expression. Adapted from the Columbus Museum of Art’s Making Creativity Visible project, this process focuses on the dispositions inherent in thinking like an artist.

Artists are playful and imaginative, and they experiment with ideas. They generate original ideas and approach the world with an insatiable curiosity. They’re comfortable with ambiguity and persist through failure. They value questioning, collaboration, and reflection. They communicate ideas and celebrate the beauty of thinking in unique and whimsical ways. What if you asked students to think like an artist in your learning space? What would that look, sound, and feel like?

Imagine if you asked students to find an object in the room and to write a series of questions they would like to ask the object. Then have them pick a question and answer it from the object’s perspective. Ask the students to use some simple materials like tape, paper, and scissors to make something connected to the answer they came up with.

This is a quick creativity challenge that can help create the conditions for students to think more like an artist in your space. If we want students to slow down and be more playful with their thinking, we must give them opportunities to exercise these dispositions.

Thinking like a designer

We currently have a surplus of problems facing our world. Our students see, hear, and/or feel the problems that surround us every day. Imagine if we asked our students to think like a designer in our learning spaces. What if we facilitated learning experiences as an opportunity to identify and solve problems?

Designers find inspiration in the people, questions, and problems of their community. They use this inspiration to generate human-centered ideas. Designers prototype and implement a variety of possible solutions. They reflect and iterate on these solutions until they find one that has a lasting and meaningful impact on those most closely connected to the problem. Inspired from the work of IDEO , a design firm in Palo Alto, California, thinking like a designer can help students see how learning can be a more collective act, as opposed to the more individualistic one common throughout schools today.

How might you create space in your classroom to empower students to think more like a designer? Imagine if you had the students at the beginning of the year write down one worry they had about the upcoming year on a sticky note. Next they each found a partner and shared their worry. You gave them the time to conduct an empathy interview to get a better understanding of the worry. Then, with simple materials like tape, paper, string, scissors, and markers, you tasked them with designing an artifact that would help relieve some of the stress of their classmate’s worry. After students completed their artifact, they took turns sharing the artifact, its meaning, and how it addressed the worry of a classmate.

The purpose of this creativity challenge is to recognize the power in thinking like a designer —finding inspiration in those around us and gathering ideas from deep, meaningful conversation and creating solutions that matter to others.

Thinking like a change agent

One element we need more of in our schools is meaning. Students know that much of what they’re learning is isolated and devoid of meaning. They know that the majority of what they’re learning is to satisfy state measured assessments. What if we asked students to think more like an agent of change in our learning spaces? What might that look, sound, and feel like?

Pulling from the work of the Columbus Museum of Art and Project Zero’s Cultivating Creative and Civic Capacities project, I and my colleagues have identified some essential dispositions of thinking like a change agent. Change agents must be able to imagine a more beautiful, just, and sustainable world for everyone. They must be able to slow down to investigate the complexity of taking action. They must be able to harness the power of influence to inspire change. Lastly, they must be able to explore the tensions between the individual and the collective society we all live in.

How might you create the conditions in your learning space for students to think like a change agent ? Imagine if you took your students on a noticing stroll around the campus or community. What if you asked them to identify meaningful issues, problems, or questions that they observed along the way, and to investigate some of these noticings to dig deeper into the interconnected nature of the causes and impact and where there might be opportunities for transformation?

Students could then take time to imagine new possibilities. How might your students design possibilities that influence others to take action and enable student experiences to be more beautiful, just, and sustainable?

The purpose of this creativity challenge is to help provide a process for students to find meaning by thinking like a change agent. What if we moved from maintaining the status quo to challenging it?

Creative Learning in Education

- Open Access

- First Online: 25 June 2021

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Ronald A. Beghetto 3

37k Accesses

15 Citations

2 Altmetric

Creative learning in schools represents a specific form of learning that involves creative expression in the context of academic learning. Opportunities for students to engage in creative learning can range from smaller scale curricular experiences that benefit their own and others’ learning to larger scale initiatives that can make positive and lasting contributions to the learning and lives of people in and beyond the walls of classrooms and schools. In this way, efforts aimed at supporting creative learning represent an important form of positive education. The purpose of this chapter is to introduce and discuss the co-constitutive factors involved in creative learning. The chapter opens by clarifying the nature of creative learning and then discusses interrelated roles played by students, teachers, academic subject matter, uncertainty, and context in creative learning. The chapter closes by outlining future directions for research on creative learning and positive education.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Creative Ecologies and Education Futures

Teaching Creatively and Teaching for Creativity

Supporting creative teaching and learning in the classroom: myths, models, and measures.

Although schools and classrooms have sometimes been characterized as contexts that suppress or even kill student creativity (Robinson, 2006 ), educational settings hold much promise for supporting students’ creative learning. Prior research has, for instance, indicated that there is on an average positive relationship ( r = .22) between measures of creativity and academic achievement (Gajda, Karwowski, & Beghetto, 2016 ). This association tends to grow when measures are more fine-tuned to assess creativity and academic learning in specific subject areas (Karwowski et al., 2020 ). These findings suggest that under the right conditions, creativity and learning can be complementary.

Indeed, creativity researchers have long asserted that creativity and learning are tightly coupled phenomena (Guilford, 1950 , 1967 ; Sawyer, 2012 ). Moreover, recent theoretical and empirical work has helped to clarify the construct and process of creative learning (Beghetto, 2020 ; Beghetto & Schuh, 2020 ; Gajda, Beghetto, & Karwowski, 2017 ). Creative learning in schools represents a specific form of learning that involves creative expression in the context of academic learning. More specifically, creative learning involves a “combination of intrapsychological and interpsychological processes that result in new and personally meaningful understandings for oneself and others” (Beghetto, p. 9).

Within the context of schools and classrooms, the process of creative learning can range from smaller scale contributions to one’s own and others’ learning (e.g., a student sharing a unique way of thinking about a math problem) to larger scale and lasting contributions that benefit the learning and lives of people in and beyond the walls of the classroom (e.g., a group of students develop and implement a creative solution for addressing social isolation in the lunchroom). In this way, efforts aimed at supporting creative learning represents a generative form of positive education because it serves as a vehicle for students to contribute to their own and others learning, life, and wellbeing (White & Kern, 2018 ). The question then is not whether creative learning can occur in schools, but rather what are the key factors that seem to support creative learning in schools and classrooms? The purpose of this chapter is to address this question.

What’s Creative About Creative Learning?

Prior to exploring how creative learning can be supported in schools and classrooms, it is important to first address the question of what is creative about creative learning? Creative learning pertains to the development of new and meaningful contributions to one’s own and others’ learning and lives. This conception of creative learning adheres to standard definitions of creativity (Plucker, Beghetto, & Dow, 2004 ; Runco & Jaeger, 2012 ), which includes two basic criteria: it must be original (new, different, or unique) as defined within a particular context or situation, and it must be useful (meaningful, effectively meets task constraints, or adequately solves the problem at hand). In this way, creativity represents a form of constrained originality. This is particularly good news for educators, as supporting creative learning is not about removing all constraints, but rather it is about supporting students in coming up with new and different ways of meeting academic criteria and learning goals (Beghetto, 2019a , 2019b ).

For example, consider a student taking a biology exam. One question on the exam asks students to draw a plant cell and label its most important parts. If the student responds by drawing a picture of a flower behind the bars of a jail cell and labels the iron bars, lack of windows, and incarcerated plant, Footnote 1 then it could be said that the student has offered an original or even humorous response, but not a creative one. In order for a response to be considered creative, it needs to be both original and meaningfully meet the task constraints. If the goal was to provide a funny response to the prompt, then perhaps it could be considered a creative response. But in this case, the task requires students to meet the task constraints by providing a scientifically accurate depiction of a plant cell. Learning tasks such as this offer little room for creative expression, because the goal is often to determine whether students can accurately reproduce what has been taught.

Conversely, consider a biology teacher who invites students to identify their own scientific question or problem, which is unique and interesting to them. The teacher then asks them to design an inquiry-based project aimed at addressing the question or problem. Next, the teacher invites students to share their questions and project designs with each other. Although some of the questions students identify may have existing answers in the scientific literature, this type of task provides the openings necessary for creative learning to occur in the classroom. This is because students have an opportunity to identify their own questions to address, develop their own understanding of new and different ways of addressing those questions, and share and receive feedback on their unique ideas and insights. Providing students with semi-structured learning experiences that requires them to meet learning goals in new and different ways helps to ensure that students are developing personally and academically meaningful understandings and also provides them with an opportunity to potentially contribute to the understanding of their peers and teachers (see Ball, 1993 ; Beghetto, 2018b ; Gajda et al., 2017 ; Niu & Zhou, 2017 for additional examples).

Creative learning can also extend beyond the walls of the classroom. When students have the opportunity and support to identify their own problems to solve and their own ways of solving them, they can make positive and lasting contributions in their schools, communities, and beyond. Legacy projects represent an example of such efforts. Legacy projects refer to creative learning endeavours that provide students with opportunities to engage with uncetainty and attempt to develop sustainable solutions to complex and ill-defined problems (Beghetto, 2017c , 2018b ). Such projects involve a blend between learning and creative expression with the aim of making a creative contribution. A group of fourth graders who learned about an endangered freshwater shrimp and then worked to restore the habitat by launching a project that spanned across multiple years and multiple networks of teachers, students, and external partners is an example of a legacy project (see Stone & Barlow, 2010 ).

As these examples illustrate, supporting creative learning is not simply about encouraging original student expression, but rather involves providing openings for students to meet academic learning constraints in new and different ways, which can benefit their own, their peers’, and even their teachers’ learning. Creative learning can also extend beyond the classroom and enable students to make a lasting and positive contribution to schools, communities, and beyond. In this way, the process of creative learning includes both intra-psychological (individual) and inter-psychological (social) aspects (Beghetto, 2016).

At the individual level, creative learning occurs when students encounter and engage with novel learning stimuli (e.g., a new concept, a new skill, a new idea, an ill-defined problem) and attempt to make sense of it in light of their own prior understanding (Beghetto & Schuh, 2020 ). Creative learning at the individual level involves a creative combinatorial process (Rothenberg, 2015 ), whereby new and personally meaningful understanding results from blending what is previously known with newly encountered learning stimuli. Creativity researchers have described this form of creativity as personal (Runco, 1996), subjective (Stein, 1953 ), or mini - c creativity Footnote 2 (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2007 ). This view of knowledge development also aligns with how some constructivist and cognitive learning theorists have conceptualized the process of learning (e.g., Alexander, Schallert, & Reynolds, 2009 ; Piaget, 1973 ; Schuh, 2017 ; Von Glasersfeld, 2013 ).

If students are able to develop a new and personally meaningful understanding, then it can be said that they have engaged in creative learning at the individual level. Of course, not all encounters with learning stimuli will result in creative learning. If learning stimuli are too discrepant or difficult, then students likely will not be able to make sense of the stimuli. Also, if students are able to accurately reproduce concepts or solve challenging tasks or problems using memorized algorithms (Beghetto & Plucker, 2006 ) without developing personally meaningful understanding of those concepts or algorithms, then they can be said to have successfully memorized concepts and techniques, but not to have engaged in creative learning. Similarly, if a student has already developed an understanding of some concept or idea and encounters it again, then they will be reinforcing their understanding, rather than developing a new or understanding (Von Glasersfeld, 2013 ). Consequently, in order for creative learning to occur at the individual level, students need to encounter optimally novel learning experiences and stimuli, such that they can make sense of those stimuli in light of their own prior learning trajectories (Beghetto & Schuh, in press; Schuh, 2017 ).

Creative learning can also extend beyond individual knowledge development. At the inter-psychological (or social) level, students have an opportunity to share and refine their conceptions with teachers and peers, making a creative contribution to the learning and lives of others (Beghetto, 2016). For instance, as apparent in the legacy projects, it is possible for students to make creative contributions beyond the walls of the classroom, which occasionally can be recognized by experts as a significant contribution. Student inventors, authors, content creators, and members of community-based problem solving teams are further examples of the inter-psychological level of creative contribution.

In sum, creative learning is a form of creative expression, which is constrained by an academic focus. It is also a special case of academic learning, because it focuses on going beyond reproductive and reinforcement learning and includes the key creative characteristics (Beghetto, 2020 ; Rothenberg, 2015 ; Sawyer, 2012 ) of being both combinatorial (combining existing knowledge with new learning stimuli) and emergent (contributing new and sometimes surprising ideas, insights, perspectives, and understandings to oneself and others).

Locating Creative Learning in Schools and Classrooms

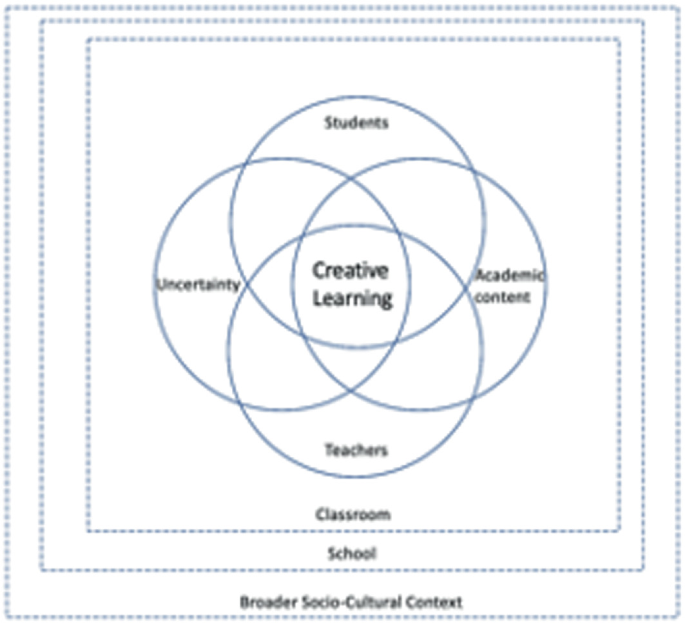

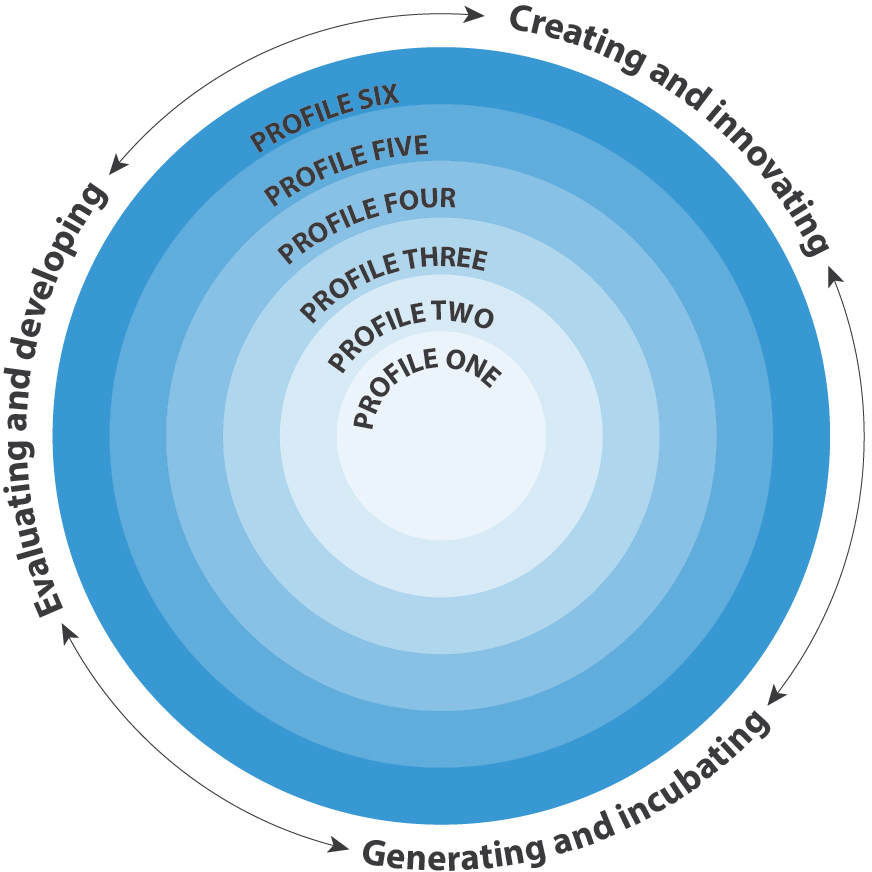

Having now explored the question of what makes creative learning creative, we can now turn our attention to locating the factors and conditions that can help support creative learning in schools and classrooms. As illustrated in Fig. 19.1 , there are at least four interrelated components posited as being necessary for creative learning to occur in schools, classrooms, and beyond: students, teachers, academic subject matter, and uncertainty. Creative learning in schools and classrooms occurs at the intersection of these four factors. Further, the classroom, school, and broader sociocultural contexts play an important role in determining whether and how creative learning will be supported and expressed. Each of these factors will be discussed in the sections that follow.

Factors involved in creative learning in schools, classrooms, and beyond

The Role of Students in Creative Learning

Students, of course, play a central role in creative learning. At the individual level, students’ idiosyncratic learning histories will influence the kinds of creative insights, ideas, and interpretations they have when engaging with new learning stimuli (Beghetto & Schuh, 2020 ; Schuh, 2017 ). Although a case can be made that subjective and personally meaningful creative insights and experiences are sufficient ends in themselves (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2007 ; Runco, 1996 ; Stein, 1953 ), creative learning tends to be situated in well-developed subject areas. Moreover, the goals of most formal educational activities, such as those that occur in schools and classrooms, include making sure that students have developed an accurate or at least a compatible understanding of existing concepts, ideas, and skills (Von Glasersfeld, 2003). Consequently, creative learning in schools—even at the individual level—involves providing students with opportunities to test out and receive feedback on their personal understandings and insights to ensure that what they have learned fits within the broader academic subject area. When this occurs, creative learning at the individual level represents a blend of idiosyncratic and generally agreed upon academic knowledge.

Notably, the idiosyncratic portion of this blend is not merely surplus ideas or insights, but rather has the potential to creatively contribute to the learning and understanding of others. Indeed, the full expression of creative learning extends beyond the individual and also has the opportunity to contribute to the learning and lives of others. At both the individual and social level of creative learning, students’ need to be willing to share, test, and receive feedback on their conceptions, otherwise the full expression of creative learning will be short-circuited. Thus, an important question, at the student level, is what factors might influence students’ willingness to share their ideas with others?

Creativity researchers have identified at least three interrelated student factors that seem to play a role in determining students’ willingness to share their conceptions with others: creative confidence, valuing creativity , and intellectual risk - taking. Creative confidence beliefs refer to a somewhat broad category of creative self-beliefs that pertain to one’s confidence in the ability to think and act creatively (Beghetto & Karwowski, 2017 ). Creative confidence beliefs can range from more situationally and domain-specific beliefs (e.g., I am confident I can creatively solve this particular problem in this particular situation) to more general and global confidence beliefs (e.g., I am confident in my creative ability). Much like other confidence beliefs (Bandura, 2012 ), creative confidence beliefs are likely influenced by a variety of personal (e.g., physiological state), social (e.g., who is present, whether people are being supportive), and situational (e.g., specific nature of the task, including constraints like time and materials) factors. Recent research has indicated that creative confidence beliefs mediate the link between creative potential and creative behaviour (Beghetto, Karwowski, Reiter-Palmon, 2020 ; Karwowski & Beghetto, 2019 ).

In the context of creative learning, this line of work suggests that students need to be confident in their own ideas prior to being willing to share those ideas with others and test out their mini-c ideas. However, valuing creativity and the willingness to take creative risks also appear to play key roles. Valuing creativity refers to whether students view creativity as an important part of their identity and whether they view creative thought and activity as worthwhile endeavours (Karwowski, Lebuda, & Beghetto, 2019 ). Research has indicated that valuing creativity moderates the mediational relationship between creative confidence and creative behaviour (Karwowski & Beghetto, 2019 ).

The same can be said for intellectual risk-taking, which refers to adaptive behaviours that puts a person at risk of making mistakes or failing (Beghetto, 2009 ). Findings from a recent study (Beghetto, Karwowski, Reiter-Palmon, 2020 ) indicate that intellectual risk-taking plays a moderating role between creative confidence and creative behaviour. In this way, even if a student has confidence in their ideas, unless they identify with and view such ideas as worthwhile and are willing to take the risks of sharing those ideas with others, then they are not likely to make a creative contribution to their own and others learning.

Finally, even if students have confidence, value creativity, and are willing to take creative risks, unless they have the opportunities and social supports to do so then they will not be able to realize their creative learning potential. As such, teachers, peers, and others in the social classroom, school, and broader environments are important for bringing such potential to fruition.

The Role of Teachers in Creative Learning

Teachers play a central role in designing and managing the kinds of learning experiences that determine whether creativity will be supported or suppressed in the classroom. Indeed, unless teachers believe that they can support student creativity, have some idea of how to do so, and are willing to try then it is unlikely that students will have systematic opportunities to engage in creative learning (Beghetto, 2017b ; Davies et al., 2013 ; Gralewski & Karawoski, 2018 ; Paek & Sumners, 2019 ). Each of these teacher roles will be discussed in turn.

First, teachers need to believe that they can support student creativity in their classroom. This has less to do with whether or not they value student creativity, as previous research indicates most generally do value creativity, and more about whether teachers have the autonomy, curricular time, and knowledge of how to support student creativity (Mullet, Willerson, Lamb, & Kettler, 2016 ). In many schools and classrooms, the primary aim of education is to support students’ academic learning. If teachers view creativity as being in competition or incompatible with that goal, then they will understandably feel that they should focus their curricular time on meeting academic learning goals, even if they otherwise value and would like to support students’ creative potential (Beghetto, 2013 ). Thus, an important first step in supporting the development of students’ creative potential is for teachers to recognize that supporting creative and academic learning can be compatible goals. When teachers recognize that they can simultaneously support creative and academic learning then they are in a better position to more productively plan for and respond to opportunities for students’ creative expression in their everyday lessons.

Equipped with this recognition, the next step in supporting student creativity is for teachers to develop the knowledge and skills necessary for infusing creativity into their curriculum (Renzulli, 2017 ) so that they can teach for creativity. Teaching for creativity in the K-12 classroom differs from other forms of creativity teaching (e.g., teaching about creativity, teaching with creativity) because it focuses on nurturing student creativity in the context of specific academic subject areas (Beghetto, 2017b ; Jeffrey & Craft, 2004 ). This form of creative teaching thereby requires that teachers have an understanding of pedagogical creativity enhancement knowledge (PCeK), which refers to knowing how to design creative learning experiences that support and cultivate students’ adapted creative attitudes, beliefs, thoughts, and actions in the planning and teaching of subject matter (Beghetto, 2017a ). Teaching for creativity thereby involves designing lessons that provide creative openings and expectations for students to creatively meet learning goals and academic learning criteria. As discussed, this includes requiring students to come up with their own problems to solve, their own ways of solving them, and their own way of demonstrating their understanding of key concepts and skills. Teaching for creativity also includes providing students with honest and supportive feedback to ensure that students are connecting their developing and unique understanding to existing conventions, norms, and ways of knowing in and across various academic domains.

Finally, teachers need to be willing to take the instructional risks necessary to establish and pursue openings in their planned lessons. This is often easier said than done. Indeed, even teachers who otherwise value creativity may worry that establishing openings in their curriculum that require them to pursue unexpected student ideas will result in the lesson drifting too far off-track and into curricular chaos (Kennedy, 2005 ). Indeed, prior research has demonstrated that it is sometimes difficult for teachers to make on-the-fly shifts in their lessons, even when the lesson is not going well (Clark & Yinger, 1977 ). One way that teachers can start opening up their curriculum is to do so in small ways, starting with the way they plan lessons. Lesson unplanning—the process of creating openings in the lesson by replacing predetermined features with to-be-determined aspects (Beghetto, 2017d )—is an example of a small-step approach. A math teacher who asks students to solve a problem in as many ways as they can represent a simple, yet potentially generative form of lesson unplanning. By starting small, teachers can gradually develop their confidence and willingness to establish openings for creative learning in their curriculum while still providing a supportive and structured learning environment. Such small, incremental steps can lead to larger transformations in practice (Amabile & Kramer, 2011 ) and reinforce teachers’ confidence in their ability to support creative learning in their classroom.

The Role of Academic Subject Matter in Creative Learning

Recall that creativity requires a blend of originality and meaningfully meeting criteria or task constraints. If students’ own unique perspectives and interpretations represent the originality component of creativity, then existing academic criteria and domains of knowledge represent the criteria and tasks constraints . Creativity always operates within constraints (Beghetto, 2019a ; Stokes, 2010 ). In the context of creative learning, those constraints typically represent academic learning goals and criteria. Given that most educators already know how to specify learning goals and criteria, they are already half-way to supporting creative learning. The other half requires considering how academic subject matter might be blended with activities that provide students with opportunities to meet those goals and criteria in their own unique and different ways. In most cases, academic learning activities can be thought of as having four components (Beghetto, 2018b ):

The what: What students do in the activity (e.g., the problem to solve, the issue to be addressed, the challenge to be resolved, or the task to be completed).

The how: How students complete the activity (e.g., the procedure used to solve a problem, the approach used to address an issue, the steps followed to resolve a challenge, or the process used to complete a task).

The criteria for success: The criteria used to determine whether students successfully completed the activity (e.g., the goals, guidelines, non-negotiables, or agreed-upon indicators of success).

The outcome: The outcome resulting from engagement with the activity (e.g., the solution to a problem, the products generated from completing a task, the result of resolving an issue or challenge, or any other demonstrated or experienced consequence of engaging in a learning activity).

Educators can use one or more of the above components (i.e., the what, how, criteria, and outcome) to design creative learning activities that blend academic subject matter with opportunities for creative expression. The degrees of freedom for doing so will vary based on the subject area, topics within subject areas, and teachers’ willingness to establish openings in their lessons.

In mathematics, for instance, there typically is one correct answer to solve a problem, whereas other subject areas, such as English Language Arts, offer much more flexibility in the kinds of “answers” or interpretations possible. Yet even with less flexibility in the kinds of originality that can be expressed in a particular subject area, there still remains a multitude of possibilities for creative expression in the kinds of tasks that teachers can offer students. As mentioned earlier, students in math can still demonstrate creative learning in the kinds of problems they design to solve, the various ways they solve them, and even how they demonstrate the outcomes and solutions to those problems.

Finally, teachers can use academic subject matter in at least two different ways to support opportunities for creative learning in their classroom (Beghetto Kaufman, & Baer, 2015 ). The first and most common way is to position subject matter learning as a means to its own end (e.g., we are learning about this technique so that you understand it ). Creativity learning can still operate in this formulation by providing students with opportunities to learn about a topic by meeting goals in unique and different ways, which are still in the service of ultimately understanding the academic subject area. However, the added value in doing so also allows opportunities for students to develop their creative confidence and competence in that particularly subject area.

The second less common, but arguably more powerful, way of positioning academic subject matter in creative learning is as a means to a creative end (e.g., we are learning about this technique so that you can use it to address the complex problem or challenge you and your team identified ). Students who, for instance, developed a project to creatively address the issue of contaminated drinking water in their community would need to learn about water contamination (e.g., how to test for it, how to eradicate contaminates) as part of the process of coming up with a creative solution. In this formulation, both academic subject matter and creative learning opportunities are in the service of attempting to make a creative contribution to the learning and lives of others (Beghetto, 2017c , 2018b ).

The Role of Uncertainty in Creative Learning

Without uncertainty, there is no creative learning. This is because uncertainty establishes the conditions necessary for new thought and action (Beghetto, 2019a ). If students (and teachers) already know what to do and how to do it, then they are rehearsing or reinforcing knowledge and skills. This assertion becomes clearer when we consider it in light of the structure of learning activities. Recall from the previous section, learning activities can be thought of as being comprised of four elements: the what, the how, the criteria for success, and the outcome.

Typically, teachers attempt to remove uncertainty from learning activities by predefining all four aspects of a learning activity. This is understandable as teachers may feel that introducing or allowing for uncertainty to be included in the activity may result curricular chaos, resulting in their own (and their students) frustration and confusion (Kennedy, 2015). Consequently, most teachers learn to plan (or select pre-planned) lessons that provide students with a predetermined problem or task to solve, which has a predetermined process or procedure for solving it, an already established criteria for determining successful performance, and a clearly defined outcome.

Although it is true that students can still learn and develop new and personally meaningful insights when they engage with highly planned lessons, such lessons are “over-planned” with respect to providing curricular space necessary for students to make creative contributions to peers and teachers. Indeed, successful performance on learning tasks in which all the elements are predetermined requires students to do what is expected and how it is expected (Beghetto, 2018a ). Conversely, the full expression of creative learning requires incorporating uncertainty in the form of to-be-determined elements in a lesson. As discussed, this involves providing structured opportunities for students (and teachers) to engage with uncertainty in an otherwise structured and supportive learning environment (Beghetto, 2019a ).

Indeed, teachers still have the professional responsibility to outline the criteria or non-negotiables, monitor student progress, and ensure that they are providing necessary and timely instructional supports. This can be accomplished by allowing students to determine how they meet those criteria. In this way, the role that uncertainty plays in creative learning can be thought of as ranging on a continuum from small openings allowing students to define some element of a learning activity (e.g., the how, what, outcomes) to larger openings where students have much more autonomy in defining elements and even the criteria for success, such as a legacy project whereby they try to make positive and lasting contributions to their schools, communities and beyond.

The Role of Context in Creative Learning

Finally, context also plays a crucial role when it comes to creative learning. Creative learning is always and already situated in sociocultural and historical contexts, which influence and are influenced by students’ unique conceptions of what they are learning and their willingness to share their conceptions with others. As illustrated in Fig. 19.1 , there are at least three permeable contextual settings in which creative learning occurs. The first is the classroom context. Although classrooms and the patterns of interaction that occur within them may appear to be somewhat stable environments, when it comes to supporting creative expression, they can be quite dynamic, variable, and thereby rather unpredictable within and across different settings (Beghetto, 2019b ; Doyle, 2006 ; Gajda et al., 2017 ; Jackson, 1990 ). Indeed, even in classrooms that are characterized as having features and patterns of interaction supportive of creative learning, such patterns may be difficult to sustain over time and even the moment-to-moment supports can be quite variable (Gajda et al., 2017 ).

It is therefore difficult to claim with any level of certainty that a given classroom is “supportive of creativity”; it really depends on what is going on in any given moment. A particular classroom may tend to be more or less supportive across time, however it is the sociodynamic and even material features of a classroom setting that play a key role in determining the kinds and frequency of creative learning openings offered to students (Beghetto, 2017a ).

The same can be said for the school context. The kinds of explicit and tacit supports for creative learning in schools likely play an important role in whether and how teachers and students feel supported in their creative expression (Amabile, 1996 ; Beghetto & Kaufman, 2014 ; Renzulli, 2017 ; Schacter, Thum, & Zifkin, 2006 ). Theoretically speaking, if teachers feel supported by their colleagues and administrators and are actively encouraged to take creative risks, then it seems likely that they would have the confidence and willingness to try. Indeed, this type of social support and modelling can have a cascading influence in and across classrooms and schools (Bandura, 1997 ). Although creativity researchers have theorized and explored the role of context on creative expression (Amabile, 1996 ; Beghetto & Kaufman, 2014 ), research specifically exploring the collective, cascading, and reciprocal effects of school and classroom contexts on creative learning is a promising and needed area of research.

In addition to classroom and school settings, sociocultural theorists in the field of creativity studies (Glăveanu et al., 2020 ) assert that the broader sociocultural influences are not static, unidirectional, or even separate from the people in those contexts, but rather dynamic and co-constitutive processes that influence and are influenced by people in those settings. Along these lines, the kinds of creative learning opportunities and experiences that teachers and students participate in can be thought of as simultaneously being shaped by and helping to shape their particular communities, cultural settings, and broader societies. Consequently, there are times and spaces where creative learning may be more or less valued and supported by the broader sociocultural context. Although some researchers have explored the role of broader societal contexts on creativity (Florida, 2019 ), additional work looking at the more dynamic and reciprocal relationship of creative learning in broader sociocultural and historical contexts is also needed.

Future Directions

Given the dynamic and multifaceted nature of creative learning, researchers interested in examining the various factors involved in creative learning likely would benefit from the development and use of analytic approaches and designs that go beyond single measures or static snapshots to include dynamic (Beghetto & Corazza, 2019 ) and multiple methods (Gajda et al., 2017 ). Such approaches can help researchers better understand the factors at play in supporting the emergence, expression, and sustainability of creative learning in and across various types of school and classroom experiences.

Another seemingly fruitful and important direction for future research on creative learning is to consider it in light of the broader context of positive education. Such efforts can complement existing efforts of researchers in positive education (Kern, Waters, Adler, & White, 2015 ), who have endeavoured to simultaneously examine multiple dimensions involved in the wellbeing of students. Indeed, as discussed, creative learning occurs at the nexus of multiple individual, social, and cultural factors and thereby requires the use of methods and approaches that can examine the interplay among these factors.

In addition, there are a variety of questions that can guide future research on creative learning, including:

How might efforts that focus on understanding and supporting creative learning fit within the broader aims of positive education? How might researchers and educators work together to support such efforts?

What are the most promising intersections among efforts aimed at promoting creative learning and student wellbeing? What are the key complementary areas of overlap and where might there be potential points of tension?

How might researchers across different research traditions in positive education and creativity studies collaborate to develop and explore broader models of wellbeing? What are the best methodological approaches for testing and refining these models? How might such work promote student and teacher wellbeing in and beyond the classroom?

Creative learning represents a potentially important aspect of positive education that can benefit from and contribute to existing research in the field. One way to help realize this potential is for researchers and educators representing a wide array of traditions to work together in an effort to develop an applied understanding of the role creative learning plays in contributing to learn and lives of students in and beyond schools and classrooms.

Creative learning represents a generative and positive educational experience, which not only contributes to the knowledge development of individual students but can also result in creative social contributions to students’ peers, teachers, and beyond. Creative learning thereby represents an important form of positive education that compliments related efforts aimed at building on the strengths that already and always inhere in the interaction among students, teachers, and educational environments. Creative learning also represents an expansion of prototypical learning efforts because it not only focuses on academic learning but also uses it as a vehicle for creative expression and the potential creative contribution to the learning and lives of others. In conclusion, creative learning offers researchers in the fields of creativity studies and positive education an important and complimentary line of inquiry.

This example is based on a popular internet meme of a humorous drawing in response to this question.

Creativity researchers recognize that there are different levels of creative magnitude (Kaufman & Beghetto, 2009 ), which ranges from subjectively experienced creativity ( mini - c ) to externally recognized creativity at the everyday or classroom level ( little - c ), the professional or expert level ( Pro - c ), and even legendary contributions that stand the test of time ( Big - C).

Alexander, P. A., Schallert, D. L., & Reynolds, R. E. (2009). What is learning anyway? A topographical perspective considered. Educational Psychologist, 44, 176–192.

Article Google Scholar

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity . Boulder, CO: Westview.

Google Scholar

Amabile, T. M., & Kramer, S. (2011). The progress principle: Using small wins to ignite joy, engagement, and creativity at work . Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

Ball, D. L. (1993). With an eye on the mathematical horizon: Dilemmas of teaching elementary school mathematics. The Elementary School Journal, 93 (4), 373–397. https://doi.org/10.1086/461730 .

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control . New York: Freeman.

Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38 (1), 9–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311410606 .

Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Correlates of intellectual risk taking in elementary school science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 46, 210–223.

Beghetto, R. A. (2013). Killing ideas softly? The promise and perils of creativity in the classroom . Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Beghetto, R. A. (2016). Creative learning: A fresh look. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 15, 6–23.

Beghetto, R. A. (2017a). Creative openings in the social interactions of teaching. Creativity: Theories-Research-Applications , 3 , 261–273.

Beghetto, R. A. (2017b). Creativity in teaching. In J. C. Kaufman, J. Baer, & V. P. Glăveanu (Eds.), Cambridge Handbook of creativity across different domains (pp. 549–556). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Beghetto, R. A. (2017c). Legacy projects: Helping young people respond productively to the challenges of a changing world. Roeper Review, 39, 1–4.

Beghetto, R. A. (2017d). Lesson unplanning: Toward transforming routine problems into non-routine problems. ZDM - the International Journal on Mathematics Education . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-017-0885-1 .

Beghetto, R. A. (2018a). Taking beautiful risks in education. Educational Leadership, 76 (4), 18–24.

Beghetto, R. A. (2018b). What if?: Building students’ problem-solving skills through complex challenges . Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Beghetto, R. A. (2019a). Structured uncertainty: How creativity thrives under constraints and uncertainty. In C. A. Mullen (Ed.), Creativity under duress in education? (Vol. 3, pp. 27–40). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90272-2_2 .

Beghetto, R. (2019b). Creativity in Classrooms. In J. Kaufman & R. Sternberg (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity (Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology, pp. 587–606). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316979839.029 .

Beghetto, R. A. (2020). Creative learning and the possible. In V. P. Glăveanu (Ed.), The Palgrave Encyclopedia of the Possible (pp. 1–8). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98390-5_57-1 .

Beghetto, R. A., & Corazza, G. E. (2019). Dynamic perspectives on creativity: New directions for theory, research, and practice . Cham, Switerland: Springer International Publishing.

Book Google Scholar

Beghetto, R. A., & Karwowski, M. (2017). Toward untangling creative self-beliefs. The creative self (pp. 3–22). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Beghetto, R. A., Karwowski, M., & Reiter-Palmon, R. (2020). Intellectual Risk taking: A moderating link between creative confidence and creative behavior? Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts . https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000323 .

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2007). Toward a broader conception of creativity: A case for mini-c creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 1, 73–79.

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2014). Classroom contexts for creativity. High Ability Studies, 25 (1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2014.905247 .

Beghetto, R. A., Kaufman, J. C., & Baer, J. (2015). Teaching for creativity in the common core . Teachers College Press.

Beghetto, R. A., & Plucker, J. A. (2006). The relationship among schooling, learning, and creativity: “All roads lead to creativity” or “you can’t get there from here”? In James C. Kaufman & J. Baer (Eds.), Creativity and reason in cognitive development (pp. 316–332). New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606915.019 .

Beghetto, R. A., & Schuh, K. (2020). Exploring the link between imagination and creativity: A creative learning perspective. In D. D. Preiss, D. Cosmelli, & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Mind wandering and creativity . Academic Press.

Clark, C. M., & Yinger, R. J. (1977). Research on teacher thinking. Curriculum Inquiry, 7, 279–304.

Davies, D., Jindal-Snape, D., Collier, C., Digby, R., Hay, P., & Howe, A. (2013). Creative learning environments in education: A systematic literature review. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 8, 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2012.07.004 .

Doyle, W. (2006). Ecological approaches to classroom management. In C. M. Evertson & C. S. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues (pp. 97–125). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Florida, R. (2019). The rise of the creative class . Basic books.

Gajda, A., Beghetto, R. A., & Karwowski, M. (2017). Exploring creative learning in the classroom: A multi-method approach. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 24, 250–267.

Gajda, A., Karwowski, M., & Beghetto, R. A. (2016). Creativity and school achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109, 269–299.

Glăveanu, V. P. (Ed.). (2016). The Palgrave handbook of creativity and culture research . London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Glăveanu, V. P., Hanchett Hanson, M., Baer, J., Barbot, B., Clapp, E. P., Corazza, G. E., … Sternberg, R. J. (2020). Advancing creativity theory and research: A Socio‐cultural manifesto. The Journal of Creative Behavior , 54 , 741–745. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.395 .

Gralewski, J., & Karawoski, M. (2018). Are teachers’ implicit theories of creativity related to the recognition of their students’ creativity? Journal of Creative Behavior, 52, 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.140 .

Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 14, 469–479.

Guilford, J. P. (1967). Creativity and learning. In D. B. Lindsley & A. A. Lumsdaine (Eds.), Brain function, Vol. IV: Brain function and learning (pp. 307–326). Los Angles: University of California Press.

Jackson, P. W. (1990). Life in classrooms . New York: Teachers College Press.

Jeffrey, B., & Craft, A. (2004). Teaching creatively and teaching for creativity: Distinctions and relationships. Educational Studies, 30, 77–87.

Karwowski, M., & Beghetto, R. A. (2019). Creative behavior as agentic action. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 13, 402–415.

Karwowski, M., Jankowska, D. M., Brzeski, A., Czerwonka, M., Gajda, A., Lebuda, I., & Beghetto, R. A. (2020). Delving into creativity and learning. Creativity Research Journal, 32 (1), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2020.1712165 .

Karwowski, M., Lebuda, I., & Beghetto, R. A. (2019). Creative self-beliefs. In J. C. Kaufman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity (2nd ed., pp. 396–418). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity. Review of General Psychology , 13, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013688 .

Kennedy, M. (2005). Inside teaching: How classroom life undermines reform . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kern, M. L., Waters, L. E., Adler, A., & White, M. A. (2015). A multidimensional approach to measuring well-being in students: Application of the PERMA framework. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10 (3), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.936962 .

Mullet, D. R., Willerson, A., Lamb, K. N., & Kettler, T. (2016). Examining teacher perceptions of creativity: A systematic review of the literature. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 21, 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2016.05.001 .

Niu, W., & Zhou, Z. (2017). Creativity in mathematics teaching: A Chinese perspective (an update. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom (2nd ed., pp. 86–107). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Paek, S. H., & Sumners, S. E. (2019). The indirect effect of teachers’ creative mindsets on teaching creativity. Journal of Creative Behavior, 53, 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.180 .

Piaget, J. (1973). To understand is to invent: The future of education . Location: Publisher.

Plucker, J., Beghetto, R. A., & Dow, G. (2004). Why isn’t creativity more important to educational psychologists? Potential, pitfalls, and future directions in creativity research. Educational Psychologist, 39, 83–96.

Renzulli, J. (2017). Developing creativity across all areas of the curriculum. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom (2nd ed., pp. 23–44). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Robinson, K. (2006). Ken Robinson: Do schools kill creativity? [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.Ted.Com/Talks/Ken_robinson_says_schools_kill_creativity .

Rothenberg, A. (2015). Flight from wonder: An investigation of scientific creativity . New York: Oxford University Press.

Runco, M. A. (1996). Personal creativity: Definition and developmental issues. NewDirections in Child Development, 72 , 3–30.

Runco, M. A., & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The standard definition of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24 (1), 92–96.

Sawyer, R. K. (2012). Explaining creativity: The science of human innovation (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Schacter, J., Thum, Y. M., & Zifkin, D. (2006). How much does creative teaching enhance elementary school students’ achievement? The Journal of Creative Behavior, 40, 47–72.

Schuh, K. L. (2017). Making meaning by making connections . Cham, Switerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-0993-2 .

Sirotnik, K. A. (1983). What you see is what you get: Consistency, persistency, and mediocrity in classrooms. Harvard Educational Review, 53, 16–31.

Stein, M. I. (1953). Creativity and culture. The Journal of Psychology, 36 , 311–322.

Stokes, P. D. (2010). Using constraints to develop creativity in the classroom. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom (pp. 88–112). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Stone, M. K., & Barlow, Z. (2010). Social learning in the STRAW project. In A. E. J. Wals (Ed.), Social learning towards a sustainable world (pp. 405–418). The Netherlands: Wageningen Academic.

Von Glasersfeld, E. (2013). Radical constructivism . New York: Routledge.

White, M., & Kern, M. L. (2018). Positive education: Learning and teaching for wellbeing and academic mastery. International Journal of Wellbeing, 8 (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v8i1.588 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

Ronald A. Beghetto

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ronald A. Beghetto .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Centre for Wellbeing Science , University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Margaret L. Kern

Department of Special Education, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA

Michael L. Wehmeyer

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Beghetto, R.A. (2021). Creative Learning in Education. In: Kern, M.L., Wehmeyer, M.L. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Positive Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64537-3_19

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64537-3_19

Published : 25 June 2021

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-64536-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-64537-3

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

What creativity really is - and why schools need it

Associate Professor of Psychology and Creative Studies, University of British Columbia

Disclosure statement

Liane Gabora's research is supported by a grant (62R06523) from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

University of British Columbia provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation CA.

University of British Columbia provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

Although educators claim to value creativity , they don’t always prioritize it.

Teachers often have biases against creative students , fearing that creativity in the classroom will be disruptive. They devalue creative personality attributes such as risk taking, impulsivity and independence. They inhibit creativity by focusing on the reproduction of knowledge and obedience in class.

Why the disconnect between educators’ official stance toward creativity, and what actually happens in school?

How can teachers nurture creativity in the classroom in an era of rapid technological change, when human innovation is needed more than ever and children are more distracted and hyper-stimulated ?

These are some of the questions we ask in my research lab at the Okanagan campus of the University of British Columbia. We study the creative process , as well as how ideas evolve over time and across societies. I’ve written almost 200 scholarly papers and book chapters on creativity, and lectured on it worldwide. My research involves both computational models and studies with human participants. I also write fiction, compose music for the piano and do freestyle dance.

What is creativity?

Although creativity is often defined in terms of new and useful products, I believe it makes more sense to define it in terms of processes. Specifically, creativity involves cognitive processes that transform one’s understanding of, or relationship to, the world.

There may be adaptive value to the seemingly mixed messages that teachers send about creativity. Creativity is the novelty-generating component of cultural evolution. As in any kind of evolutionary process, novelty must be balanced by preservation.

In biological evolution, the novelty-generating components are genetic mutation and recombination, and the novelty-preserving components include the survival and reproduction of “fit” individuals. In cultural evolution , the novelty-generating component is creativity, and the novelty-preserving components include imitation and other forms of social learning.

It isn’t actually necessary for everyone to be creative for the benefits of creativity to be felt by all. We can reap the rewards of the creative person’s ideas by copying them, buying from them or simply admiring them. Few of us can build a computer or write a symphony, but they are ours to use and enjoy nevertheless.

Inventor or imitator?

There are also drawbacks to creativity . Sure, creative people solve problems, crack jokes, invent stuff; they make the world pretty and interesting and fun. But generating creative ideas is time-consuming. A creative solution to one problem often generates other problems, or has unexpected negative side effects.

Creativity is correlated with rule bending, law breaking, social unrest, aggression, group conflict and dishonesty. Creative people often direct their nurturing energy towards ideas rather than relationships, and may be viewed as aloof, arrogant, competitive, hostile, independent or unfriendly.

Also, if I’m wrapped up in my own creative reverie, I may fail to notice that someone else has already solved the problem I’m working on. In an agent-based computational model of cultural evolution , in which artificial neural network-based agents invent and imitate ideas, the society’s ideas evolve most quickly when there is a good mix of creative “inventors” and conforming “imitators.” Too many creative agents and the collective suffers. They are like holes in the fabric of society, fixated on their own (potentially inferior) ideas, rather than propagating proven effective ideas.

Of course, a computational model of this sort is highly artificial. The results of such simulations must be taken with a grain of salt. However, they suggest an adaptive value to the mixed signals teachers send about creativity. A society thrives when some individuals create and others preserve their best ideas.

This also makes sense given how creative people encode and process information. Creative people tend to encode episodes of experience in much more detail than is actually needed. This has drawbacks: Each episode takes up more memory space and has a richer network of associations. Some of these associations will be spurious. On the bright side, some may lead to new ideas that are useful or aesthetically pleasing.

So, there’s a trade-off to peppering the world with creative minds. They may fail to see the forest for the trees but they may produce the next Mona Lisa.

Innovation might keep us afloat

So will society naturally self-organize into creators and conformers? Should we avoid trying to enhance creativity in the classroom?

The answer is: No! The pace of cultural change is accelerating more quickly than ever before. In some biological systems, when the environment is changing quickly, the mutation rate goes up. Similarly, in times of change we need to bump up creativity levels — to generate the innovative ideas that will keep us afloat.

This is particularly important now. In our high-stimulation environment, children spend so much time processing new stimuli that there is less time to “go deep” with the stimuli they’ve already encountered. There is less time for thinking about ideas and situations from different perspectives, such that their ideas become more interconnected and their mental models of understanding become more integrated.

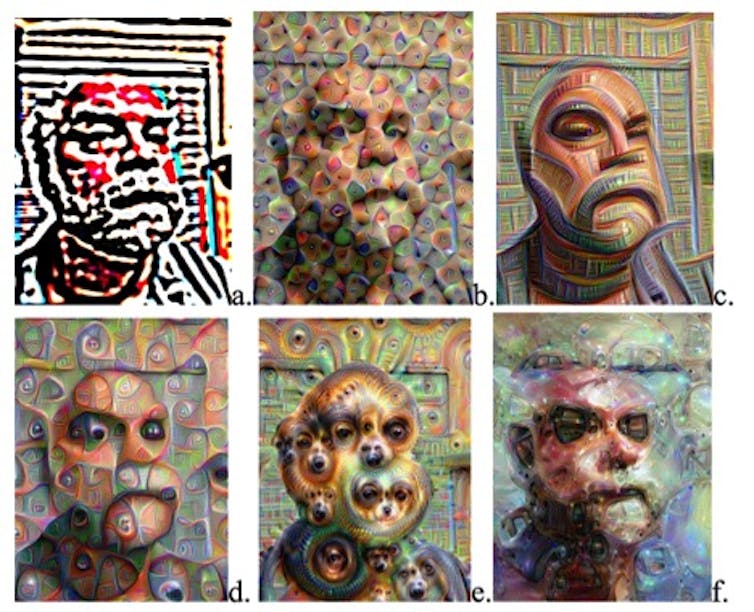

This “going deep” process has been modeled computationally using a program called Deep Dream , a variation on the machine learning technique “Deep Learning” and used to generate images such as the ones in the figure below.

The images show how an input is subjected to different kinds of processing at different levels, in the same way that our minds gain a deeper understanding of something by looking at it from different perspectives. It is this kind of deep processing and the resulting integrated webs of understanding that make the crucial connections that lead to important advances and innovations.

Cultivating creativity in the classroom

So the obvious next question is: How can creativity be cultivated in the classroom? It turns out there are lots of ways ! Here are three key ways in which teachers can begin:

Focus less on the reproduction of information and more on critical thinking and problem solving .

Curate activities that transcend traditional disciplinary boundaries, such as by painting murals that depict biological food chains, or acting out plays about historical events, or writing poems about the cosmos. After all, the world doesn’t come carved up into different subject areas. Our culture tells us these disciplinary boundaries are real and our thinking becomes trapped in them.

Pose questions and challenges, and follow up with opportunities for solitude and reflection. This provides time and space to foster the forging of new connections that is so vital to creativity.

- Cultural evolution

- Creative pedagody

- Teaching creativity

- Creative thinking

- Back to School 2017

Admissions Officer

Director of STEM

Community member - Training Delivery and Development Committee (Volunteer part-time)

Chief Executive Officer

Head of Evidence to Action

Creativity and critical thinking and what it means for schools

- Ravi Gurumurthy

About Nesta

Nesta is an innovation foundation. For us, innovation means turning bold ideas into reality and changing lives for the better. We use our expertise, skills and funding in areas where there are big challenges facing society.

Director of Education

Joysy was the Director of Education and led Nesta's work in education across innovation programmes, research and investment.

On this page

Creativity is one of the most critical skills for the future. Without creativity, there would be no innovation. However, there is mixed evidence on how to develop it and whether it is transferable. OECD has done research with schools and teachers in 11 countries to develop and trial resources to develop creativity and critical thinking in primary and secondary education. At Nesta, we’d like to see the UK do more to engage with this community of innovative practice, and test the most promising solutions developed in other contexts.

An OECD event 24-25 September , where Nesta Chief Executive Geoff Mulgan was invited to speak, helped to share emerging answers to the question “How can creative thinking across all disciplines including the arts, sciences and humanities be supported by the current education system?”. There were lots of examples on how to foster and assess creativity and critical thinking. The upcoming Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2021 will have a creativity assessment.

Andreas Schleicher, Director for Education and Skills at OECD said, “Memorisation is less useful as problems become more difficult.” In the data that he showed, in many countries, there seems to be a significant gap between what teachers report to be desirable pedagogies and what actually happens in classrooms. What was surprising was that UK has highest level of prevalence of memorisation in classrooms.

“The dilemma for educators is that routine academic knowledge (the skills that are easiest to teach and easiest to test) are exactly the skills that are also easiest to digitise" Andreas Schleicher

“The dilemma for educators is that routine academic knowledge (the skills that are easiest to teach and easiest to test) are exactly the skills that are also easiest to digitise, automate and outsource. However, educational success is no longer about reproducing content knowledge, but about extrapolating from what we know and applying that knowledge creatively in novel situations, and about thinking across the boundaries of subject-matter disciplines.”

Creativity is not solely related to arts and culture. There is also the development of cross-disciplinary creative thinking skills (e.g. coming up with original & creative ideas in science). There is evidence that these skills give us an edge in a world driven by Artificial Intelligence (AI) and new technologies. We know that creative thinking is not sufficiently supported within the current curriculum in England. Sir Nicholas Serota, chair of Arts Council England spoke about the upcoming Durham Commision report. He mentioned the Manifesto for a Creative Britain created by young people back in 2008 but not a single recommendation has been implemented by the government.

Much of the development in this space is being driven on the international stage and by countries like the US and Australia. Promisingly, the Welsh government has included a focus on ‘creativity and innovation’ within its new curriculum. We would like to see similar changes in England.

How Nesta is moving the agenda forward

At Nesta, part of our work in Education is based on the belief that young people need a broader education so that everyone thrives in a fast changing world.

More recently we have been asking ourselves - what will be the long-term impact of the decline of arts in schools? Are creative careers and pursuits increasingly elitist? How will AI challenge our preconceptions around human creativity? How do we turn the tide and bridge the growing ‘creativity divide’?

Nesta’s research shows that creativity will become even more important to the growth of jobs between now and 2030. Based on analysis of 35 million job adverts, research from the Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre found that creative industries don’t have a monopoly on creativity.

We must use and apply this labour market research to education. What transferable skills are employers looking for and what are the most effective ways of giving young people the creative skills needed to thrive now and in the future .

We will be developing new partnerships and programmes to support this work. To date, we have researched and supported wider skills linked to creativity, including collaborative problem solving , social and emotional skills.

We are bringing business and education together to create new opportunities for learners. We are supporting innovative approaches to providing multidisciplinary, real-world learning and collaborative problem solving opportunities to young people. Some examples of work that we are doing include:

- Maths Mission - working with Tata on the Cracking the Code challenge, where we have made links between problem-solving, maths and creativity. Secondary school students work in teams to design a maths game and present their idea combining maths, creativity and communication skills.

- Longitude Explorer Prize - working on building AI skills, entrepreneurial and innovation skills in 11-16 year olds by getting them to solve problems they care about. This is in partnership with businesses and government to build future talent pipeline.

- Future Ready Fund - supporting ten high-potential approaches to developing social and emotional skills in young people. We contributed to the manifesto on social and emotional skills and the setup of Karanga , a global alliance for social emotional learning and life skills.

With the Durham Commission launching their long-awaited report next month, we believe there is an opportunity to build a revitalised coalition and consensus on the importance of creativity - and move from talk to action. We will be developing new partnerships and programmes supporting high-potential approaches, building on our expertise in both the creative economy and education.

Despite recognition of the importance of these skills, funding, policy and provision in the UK has not yet caught up. We are commissioning new research on social and emotional skills to develop an understanding of ‘what works’ in building these skills, and we're exploring new approaches to bridge the gap between labour market demand and supply of skills . We are also funding low-cost, high-quality interventions which will support provision in schools.

We invite you to help us build the evidence for what works in developing creative skills that improve life outcomes, and campaign for reimagining education. Please get in touch at [email protected]

Also of interest

Transforming early childhood: narrowing the gap between children from lower- and higher-income families

The future of early-years data

Arts Impact Chats: Angela Dixon, Saffron Hall

Stay up to date.

Join our mailing list to receive the Nesta edit: your first look at the latest insights, opportunities and analysis from Nesta and the innovation sector.

* denotes a required field

Sign up for our newsletter

You can unsubscribe by clicking the link in our emails where indicated, or emailing [email protected] . Or you can update your contact preferences . We promise to keep your details safe and secure. We won’t share your details outside of Nesta without your permission. Find out more about how we use personal information in our Privacy Policy .

Skolera LMS Blog Educational Technology Articles and News

7 Methods to Develop Creative Thinking Skills for Students

Aida Elbanna Teaching Strategies Comments Off on 7 Methods to Develop Creative Thinking Skills for Students 16,854 Views

Creative thinking skills for students are what every teacher knows to be crucial in the learning process. Giving students the chance and space to think creatively will definitely be fruitful in the long run.

Creative-based activities, games, and questions are endless. Consider trying to implement any of these exercises at least once a week for your class, and you’ll notice a huge improvement in engagement as well as creativity.

What Is Creative Thinking in Education?

According to Kampylis and Berki (2014) ,

“Creative thinking is defined as the thinking that enables students to apply their imagination to generating ideas, questions and hypotheses, experimenting with alternatives and to evaluating their own and their peers’ ideas, final products and processes.”

Importance of Creative Thinking for Students

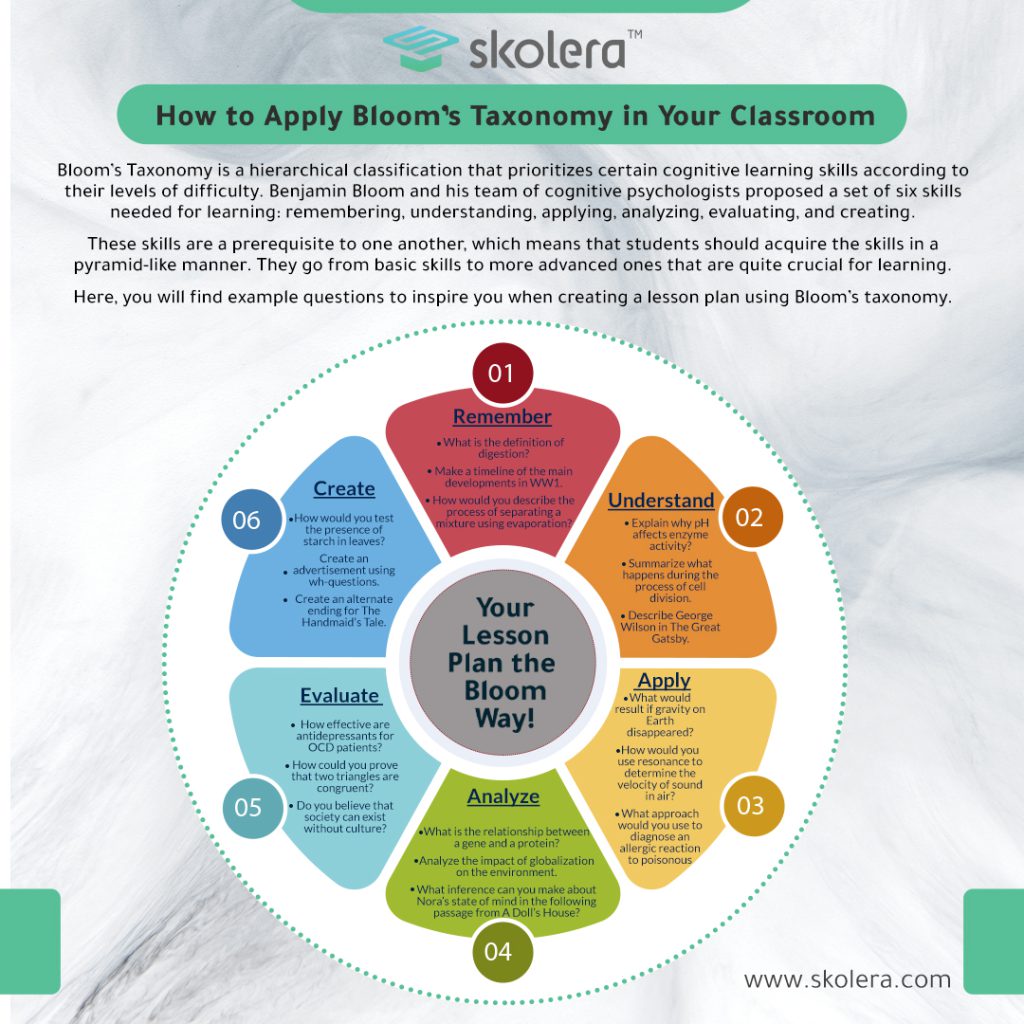

Developing creative thinking in learners has long been considered an essential aspect of education and brain development. Harold Bloom (1956), the American Literary critic and educator, devised his Bloom’s Taxonomy which categorises learning into 6 categories—the final stage is to “create.”

Bloom asserts that creation is an indispensable part of learning in which students are allowed to produce their own unique work, investigate solutions to problems, design a product, or develop a theory.

Therefore, it can be said that creative thinking for students forms the culmination of students’ knowledge and education.

The Importance of Bloom’s Taxonomy : The Teacher’s Guide to an Exceptional Classroom

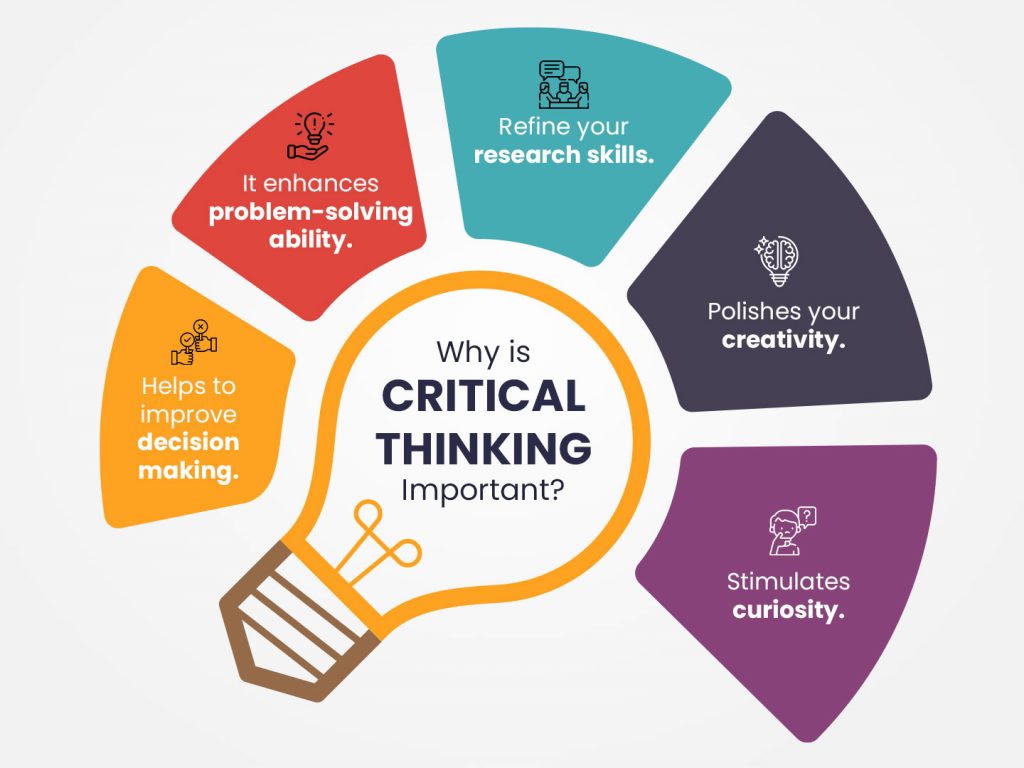

In an article entitled “Creative and Critical Thinking Skills in Problem-based Learning Environments,” Bengi Birgili asserts that critical thinking skills entail analysing sources for credibility, making connections and drawing conclusions.

He talks about how critical thinking involves several processes and cognitive actions.

He believes that people, or rather students, who practice critical thinking on a regular basis can never behave without thinking, can think independently and can identify problems in detail.

Here are some of Birgili’s characteristics that go into the process of critical thinking:

- Being analytical

- Thinking without prejudice

- Paying attention to details

- Being open to changes

As Edward de Bono , author of Six Thinking Hats puts it:

“Creativity involves breaking out of established patterns in order to look at things in a different way.”

Creative Thinking Examples for Students

Below are some methods, exercises and activities that teachers and schools can make use of for developing students’ creative thinking skills in the classroom or even beyond the school.

a) Creative Thinking Games For Students

Dictionary story.

This exercise can be quite beneficial for teachers who like to pique students’ interest in vocabulary and enrich their skills. So get yourself a dictionary, cit pick a random word, and try to make up a brief story using the word you chose, the word above it, and the word below it.

This exercise will reveal your students’ potential to find connections between words and mix ideas that might not relate to each other at first glance.

Ultimately, your students would have crafted a narrative out of simple means. This can form the basis of your fiction writing lessons and help your students when they are stuck for ideas.

Six-word story

When teachers are at a loss for creative thinking exercises for students, they like to resort to the old-fashioned technique called “six-word story.” It basically tests the students’ ability to be creative using only six words to form a story.

According to Doug Weller , three elements make up a good six-word story: it makes sense to the reader, it takes him/her on a journey, and it leaves the reader with emotion. A perfect example of this would be Hemingway’s famous “For sale: baby shoes. Never worn.”

Make sure to give this exercise to your students next lesson and watch their creative minds bloom!

Avoid the letter ‘e’

Henri Matisse, the French Visual Artist, says “Don’t wait for inspiration. It comes while working.” Recent research has debunked the myth that creativity is inherent or genetic. On the contrary, scientists now believe that creativity is a skill that is acquired through regular practice and exercise.

An entertaining way to develop your students’ creative thinking skills is to play the game “avoid the letter e.” You can organize the class into pairs and allow them to have a conversation without using the letter ‘e’.

This will train their minds to be resourceful when it comes to language usage.

b) Creative Thinking Activities For Students

Take a look at some of these creative thinking activities for students to use online or in the actual classroom.

-Look Away from What You Are Creating

Working on drawing what you actually see rather than what you imagine you see is the aim of the exercise.