- Poetry Contests

The Ten Best Poems to Analyze

by Adam Sedia

The Roman poet Horace famously set forth the twofold purpose of poetry: to teach and to delight. The sheer aesthetic and imaginative language of poetry is often on its own enough to delight, but in analyzing the poem teaching and delighting converge. The reader both unearths the deeper, hidden meanings of the poem and at the same time derives an intellectual satisfaction at the discovery.

Not all poems contain the same analytical depth, however. Some are “tougher nuts to crack” to arrive at their analytical core or contain multiple layers or facets of meaning that are equally valid from the face of the text. The list below collects ten of these analytically-intensive poems to provide a basic illustration of this type of poem.

Selecting a poem as analytically “deep” is not meant to disparage other poems. Many fine poems excluded from this list sacrifice analytical depth for directness of message, beauty or innovativeness of language, or narrative drama. All of these legitimate poetic goals justify at times sacrifice of analytical depth, and that does not detract from the poem’s merit. Consequently, this list is not to be construed as a sort of “best poems” compilation. Analytical depth alone is not the “be all and end all” of poetry.

It is also necessary here to set forth three qualifications. First, and most obviously, the poems selected are confined only to those written in English. Textual analysis is serious work, able to be undertaken seriously only in the native language of the text. Many great poems in other languages have at least the same level of analytical depth as those presented here, but doing them justice would require presentation in their native language and discussion of their subtleties in the original, which is far beyond the scope of this compilation.

Second, this list omits epic poems from consideration. The best epics have an analytical richness derived from a combination of the language and the narrative structure, and including them would crowd out lyric poems from the list that often have analytical depth as their primary feature. Accordingly, the list focuses exclusively on lyric and short narrative poems.

And finally, the list is confined only to classical poems—that is, poems written in meter according to form. Modernist works like those of William Butler Yeats, T.S. Eliot, and Ezra Pound are written in a hyper-elusive cubist style that demands exhaustive analysis, usually without any particular meaning intended. It can even be said that in modernist and contemporary poetry, analysis, not aesthetics, serves as the primary poetic end. Including modernist poetry in the list would be to give it an unfair advantage in the field of analytical depth.

In many ways, analytical depth is harder to achieve in a classical poem, where formal strictures demand unity of language and structural coherence, and do not allow for a stream-of-consciousness presentation of images that characterizes modernist poetry. This list, then, presents the best analytically deep poems that achieve their depth within the confines and exquisiteness of classical form.

1. Sonnet 142 by William Shakespeare (1609)

Love is my sin, and thy dear virtue hate, Hate of my sin, grounded on sinful loving: O, but with mine compare thou thine own state, And thou shalt find it merits not reproving; Or, if it do, not from those lips of thine, That have profan’d their scarlet ornaments And seal’d false bonds of love as oft as mine, Robb’d others’ beds’ revenues of their rents. Be it lawful I love thee, as thou lov’st those Whom thine eyes woo as mine importune thee: Root pity in thy heart, that when it grows, Thy pity may deserve to pitied be. If thou dost seek to have what thou dost hide, By self-example mayst thou be denied!

All of Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets are masterpieces, and many contain many facets and layers of analysis, so selection from among them was difficult. Sonnet 142, though, comes first because of its striking use of contrast and innovative use of form. Shakespeare transforms love into sin and hate into virtue; below the superficial curse is an urging to pity. The structural analysis is also intriguing: although the rhyme scheme is Shakespearian, the presentation of the solution at the beginning of the third quatrain resembles more the Italian form of the sonnet.

2. “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning” by John Donne (1633)

As virtuous men pass mildly away, And whisper to their souls to go, Whilst some of their sad friends do say, “Now his breath goes,” and some say, “No.”

So let us melt, and make no noise, No tear-floods, nor sigh-tempests move; ‘Twere profanation of our joys To tell the laity our love.

Moving of th’ earth brings harms and fears; Men reckon what it did, and meant; But trepidation of the spheres, Though greater far, is innocent.

Dull sublunary lovers’ love —Whose soul is sense—cannot admit Of absence, ‘cause it doth remove The thing which elemented it.

But we by a love so much refined, That ourselves know not what it is, Inter-assurèd of the mind, Care less, eyes, lips and hands to miss.

Our two souls therefore, which are one, Though I must go, endure not yet A breach, but an expansion, Like gold to aery thinness beat.

If they be two, they are two so As stiff twin compasses are two; Thy soul, the fix’d foot, makes no show To move, but doth, if th’ other do.

And though it in the centre sit, Yet, when the other far doth roam, It leans, and hearkens after it, And grows erect, as that comes home.

Such wilt thou be to me, who must, Like th’ other foot, obliquely run; Thy firmness makes my circle just And makes me end where I begun.

Donne’s style is labeled “metaphysical” for its philosophical treatment of its subjects, and this “Valediction” is regarded as one of the finest examples of metaphysical poetry. Here, Donne weaves together conceits (extended metaphors), ultimately comparing the union of souls to the ends of a compass, with each soul’s path likened to the infinity of the circle. Along the way, Donne introduces several metaphysical ideas, including a discussion of astronomy (“trepidation of the spheres” and “sublunary”) and the nature of the soul. What is ostensibly a love poem is actually a deep philosophical contemplation of the human soul.

3. “The Sick Rose” by William Blake (1789)

O Rose thou art sick, The invisible worm That flies in the night, In the howling storm,

Has found out thy bed Of crimson joy: And his dark secret love Does thy life destroy.

From Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience , this short, eight-line poem has been called “one of the most baffling and enigmatic in the English language.” It lends itself to myriad interpretations, from the ravages of syphilis on the eighteenth-century nobility to the effect of experience on the human condition. Its open metaphors and laconic tone make the interpretive possibilities endless.

4. “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” by William Wordsworth (1815)

The Child is father of the Man; And I could wish my days to be Bound each to each by natural piety.

I. There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream, The earth, and every common sight, To me did seem Apparelled in celestial light, The glory and the freshness of a dream. It is not now as it hath been of yore;— Turn wheresoe’er I may, By night or day, The things which I have seen I now can see no more.

II. The rainbow comes and goes, And lovely is the rose; The moon doth with delight Look round her when the heavens are bare; Waters on a starry night Are beautiful and fair; The sunshine is a glorious birth; But yet I know, where’er I go, That there hath passed away a glory from the earth.

III. Now, while the birds thus sing a joyous song, And while the young lambs bound As to the tabor’s sound, To me alone there came a thought of grief: A timely utterance gave that thought relief, And I again am strong. The cataracts blow their trumpets from the steep; No more shall grief of mine the season wrong; I hear the echoes through the mountains throng; The winds come to me from the fields of sleep, And all the earth is gay; Land and sea Give themselves up to jollity, And with the heart of May Doth every beast keep holiday. Thou child of joy, Shout round me, let me hear thy shouts, thou happy shepherd-boy!

IV. Ye blessed creatures, I have heard the call Ye to each other make; I see The heavens laugh with you in your jubilee; My heart is at your festival. My head hath its coronal, The fulness of your bliss, I feel—I feel it all. Oh evil day if I were sullen While Earth herself is adorning This sweet May morning, And the children are culling On every side, In a thousand valleys far and wide, Fresh flowers, while the sun shines warm, And the babe leaps up on his mother’s arm: I hear, I hear, with joy I hear! —But there’s a tree, of many, one, A single field which I have looked upon, Both of them speak of something that is gone: The pansy at my feet Doth the same tale repeat. Whither is fled the visionary gleam? Where is it now, the glory and the dream?

V. Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting: The soul that rises with us, our life’s star, Hath had elsewhere its setting, And cometh from afar; Not in entire forgetfulness, And not in utter nakedness, But trailing clouds of glory do we come From God, who is our home. Heaven lies about us in our infancy! Shades of the prison-house begin to close Upon the growing boy, But he beholds the light, and whence it flows, He sees it in his joy; The youth, who daily farther from the East Must travel, still is nature’s priest, And by the vision splendid Is on his way attended; At length the man perceives it die away, And fade into the light of common day.

VI. Earth fills her lap with pleasures of her own; Yearnings she hath in her own natural kind, And even with something of a mother’s mind, And no unworthy aim, The homely nurse doth all she can To make her foster-child, her inmate man, Forget the glories he hath known, And that imperial palace whence he came.

VII. Behold the child among his new-born blisses, A six years’ darling of a pigmy size! See, where ‘mid work of his own hand he lies, Fretted by sallies of his mother’s kisses, With light upon him from his father’s eyes! See at his feet some little plan or chart, Some fragment from his dream of human life, Shaped by himself with newly-learned art— A wedding or a festival, A mourning or a funeral; And this hath now his heart, And unto this he frames his song. Then will he fit his tongue To dialogues of business, love, or strife: But it will not be long Ere this be thrown aside, And with new joy and pride The little actor cons another part, Filling from time to time his ‘humorous stage’ With all the persons, down to palsied age, That Life brings with her in her equipage, As if his whole vocation Were endless imitation.

VIII. Thou, whose exterior semblance doth belie Thy soul’s immensity; Thou, best philosopher, who yet dost keep Thy heritage, thou eye among the blind, That, deaf and silent, read’st the eternal deep, Haunted for ever by the eternal mind,— Mighty prophet! seer blest! On whom those truths do rest, Which we are toiling all our lives to find, In darkness lost, the darkness of the grave; Thou, over whom thy immortality Broods like the day, a master o’er a slave, A presence which is not to be put by; Thou little child, yet glorious in the might Of heaven-born freedom on thy being’s height, Why with such earnest pains dost thou provoke The years to bring the inevitable yoke, Thus blindly with thy blessedness at strife? Full soon thy soul shall have her earthly freight, And custom lie upon thee with a weight, Heavy as frost, and deep almost as life!

IX. O joy, that in our embers Is something that doth live, That nature yet remembers What was so fugitive! The thought of our past years in me doth breed Perpetual benediction: not indeed For that which is most worthy to be blest— Delight and liberty, the simple creed Of childhood, whether busy or at rest, With new-fledged hope still fluttering in his breast:— Not for these I raise The song of thanks and praise; But for those obstinate questionings Of sense and outward things, Fallings from us, vanishings; Blank misgivings of a creature Moving about in worlds not realized, High instincts before which our mortal nature Did tremble like a guilty thing surprised: But for those first affections, Those shadowy recollections, Which, be they what they may, Are yet the fountain light of all our day, Are yet a master light of all our seeing; Uphold us, cherish, and have power to make Our noisy years seem moments in the being Of the eternal silence: truths that wake, To perish never; Which neither listlessness, nor mad endeavor, Nor man nor boy, Nor all that is at enmity with joy, Can utterly abolish or destroy! Hence in a season of calm weather, Though inland far we be, Our souls have sight of that immortal sea Which brought us hither, Can in a moment travel thither, And see the children sport upon the shore, And hear the mighty waters rolling evermore.

X. Then sing, ye birds! sing, sing a joyous song! And let the young lambs bound As to the tabor’s sound! We in thought will join your throng, Ye that pipe and ye that play, Ye that through your hearts to-day Feel the gladness of the May! What though the radiance which was once so bright Be now forever taken from my sight, Though nothing can bring back the hour Of splendor in the grass, of glory in the flower? We will grieve not, rather find Strength in what remains behind; In the primal sympathy Which, having been, must ever be; In the soothing thoughts that spring Out of human suffering; In the faith that looks through death, In years that bring the philosophic mind.

XI. And O ye fountains, meadows, hills, and groves, Forebode not any severing of our loves! Yet in my heart of hearts I feel your might; I only have relinquished one delight To live beneath your more habitual sway. I love the brooks, which down their channels fret, Even more than when I tripped lightly as they: The innocent brightness of a new-born day Is lovely yet: The clouds that gather round the setting sun Do take a sober coloring from an eye That hath kept watch o’er man’s mortality; Another race hath been, and other palms are won. Thanks to the human heart by which we live, Thanks to its tenderness, its joys, and fears, To me the meanest flower that blows can give Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears.

Typically Wordsworth’s poetry is clear and direct, easily understandable on a first reading. Highly atypical of Wordsworth, the “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” is a discursive, deeply philosophical poem that requires an understanding of Platonism to grasp fully. At its core, the poem views the human soul as originating in the realm of the ideal, and the conflict of life is to return to that ideal despite its loss as the world makes its impressions on the developing mind. The poem’s length allows for several detailed elaborations of this idea.

5. “Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1818)

This sonnet packs in multiple layers of meaning. The most obvious reading addresses the futility of human grandeur, but closer reading reveals a message about art and artists, and how artistic portrayal turns perception into reality. Combine this with a complex, double-layered narrative structure and historical allusions to Napoleon, and the reader has a deep and multidimensional work to enjoy.

6. “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning (1842)

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall, Looking as if she were alive. I call That piece a wonder, now; Fra Pandolf’s hands Worked busily a day, and there she stands. Will’t please you sit and look at her? I said “Fra Pandolf” by design, for never read Strangers like you that pictured countenance, The depth and passion of its earnest glance, But to myself they turned (since none puts by The curtain I have drawn for you, but I) And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst, How such a glance came there; so, not the first Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, ’twas not Her husband’s presence only, called that spot Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek; perhaps Fra Pandolf chanced to say, “Her mantle laps Over my lady’s wrist too much,” or “Paint Must never hope to reproduce the faint Half-flush that dies along her throat.” Such stuff Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough For calling up that spot of joy. She had A heart—how shall I say?— too soon made glad, Too easily impressed; she liked whate’er She looked on, and her looks went everywhere. Sir, ’twas all one! My favour at her breast, The dropping of the daylight in the West, The bough of cherries some officious fool Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule She rode with round the terrace—all and each Would draw from her alike the approving speech, Or blush, at least. She thanked men—good! but thanked Somehow—I know not how—as if she ranked My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name With anybody’s gift. Who’d stoop to blame This sort of trifling? Even had you skill In speech—which I have not—to make your will Quite clear to such an one, and say, “Just this Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss, Or there exceed the mark”—and if she let Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse— E’en then would be some stooping; and I choose Never to stoop. Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt, Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands; Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands As if alive. Will’t please you rise? We’ll meet The company below, then. I repeat, The Count your master’s known munificence Is ample warrant that no just pretense Of mine for dowry will be disallowed; Though his fair daughter’s self, as I avowed At starting, is my object. Nay, we’ll go Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though, Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity, Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me!

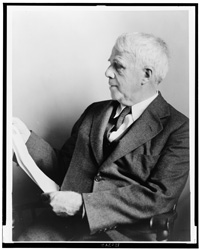

Along with “Porphyria’s Lover,” this is one of Browning’s most well-known dramatic monologues. The speaker is an actual historical figure, Alfonso II, Duke of Ferrara (1533-1598), describing his deceased last wife, Lucrezia de’ Medici (1545-1561), to the ambassador of the Austrian emperor, whose daughter he plans to marry next (see images above of Alfonso and Lucrezia). The duke’s monologue offers a psychologically rich profile of paranoia and narcissism, all of which must be considered in light of the audience to whom Browning has him speaking. This short monologue provides one of the best examples of psychological analysis in literature.

7. “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe (1845)

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore — While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door. “ ’Tis some visiter,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door — Only this and nothing more.”

Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December; And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor. Eagerly I wished the morrow; — vainly I had sought to borrow From my books surcease of sorrow — sorrow for the lost Lenore — For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore — Nameless here for evermore.

And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain Thrilled me — filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before; So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating “ ’Tis some visiter entreating entrance at my chamber door — Some late visiter entreating entrance at my chamber door; — This it is and nothing more.”

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer, “Sir,” said I, “or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore; But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping, And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door, That I scarce was sure I heard you” — here I opened wide the door; —— Darkness there and nothing more.

Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing, Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before; But the silence was unbroken, and the stillness gave no token, And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, “Lenore?” This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, “Lenore!” — Merely this and nothing more.

Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning, Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before. “Surely,” said I, “surely that is something at my window lattice; Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore — Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore;— ‘Tis the wind and nothing more!”

Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter, In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore; Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he; But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door — Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door — Perched, and sat, and nothing more.

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling, By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore, “Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou,” I said, “art sure no craven, Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore — Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore!” Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly, Though its answer little meaning — little relevancy bore; For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being Ever yet was blessed with seeing bird above his chamber door — Bird or beast upon the sculptured bust above his chamber door, With such name as “Nevermore.”

But the Raven, sitting lonely on the placid bust, spoke only That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour. Nothing farther then he uttered — not a feather then he fluttered — Till I scarcely more than muttered “Other friends have flown before — On the morrow he will leave me, as my Hopes have flown before.” Then the bird said “Nevermore.”

Startled at the stillness broken by reply so aptly spoken, “Doubtless,” said I, “what it utters is its only stock and store Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore — Till the dirges of his Hope that melancholy burden bore Of ‘Never — nevermore’.”

But the Raven still beguiling my sad fancy into smiling, Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird, and bust and door; Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore — What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore Meant in croaking “Nevermore.”

This I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom’s core; This and more I sat divining, with my head at ease reclining On the cushion’s velvet lining that the lamp-light gloated o’er, But whose velvet-violet lining with the lamp-light gloating o’er, She shall press, ah, nevermore!

Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer Swung by seraphim whose foot-falls tinkled on the tufted floor. “Wretch,” I cried, “thy God hath lent thee — by these angels he hath sent thee Respite — respite and nepenthe, from thy memories of Lenore; Quaff, oh quaff this kind nepenthe and forget this lost Lenore!” Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil! — prophet still, if bird or devil! — Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore, Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted — On this home by Horror haunted — tell me truly, I implore — Is there — is there balm in Gilead? — tell me — tell me, I implore!” Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil! — prophet still, if bird or devil! By that Heaven that bends above us — by that God we both adore — Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn, It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore — Clasp a rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore.” Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

“Be that word our sign of parting, bird or fiend!” I shrieked, upstarting — “Get thee back into the tempest and the Night’s Plutonian shore! Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken! Leave my loneliness unbroken! — quit the bust above my door! Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!” Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door; And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming, And the lamp-light o’er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor; And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor Shall be lifted — nevermore!

Poe’s reputation as a master of the macabre does this poem serious injustice. Far more than just a creepy tale, “The Raven” represents the inward battle with nihilism as hinted in the raven’s mantra, “nevermore.” The raven itself presents a masterful use of personification of an idea, and Poe draws the reader into the inward psychological battle raging in the speaker as he confronts nihilism personified.

8. “Dover Beach” by Matthew Arnold (1867)

The sea is calm tonight. The tide is full, the moon lies fair Upon the straits; on the French coast the light Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand, Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay. Come to the window, sweet is the night-air! Only, from the long line of spray Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land, Listen! you hear the grating roar Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling, At their return, up the high strand, Begin, and cease, and then again begin, With tremulous cadence slow, and bring The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago Heard it on the Ægean, and it brought Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow Of human misery; we Find also in the sound a thought, Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled. But now I only hear Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar, Retreating, to the breath Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true To one another! for the world, which seems To lie before us like a land of dreams, So various, so beautiful, so new, Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light, Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain; And we are here as on a darkling plain Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, Where ignorant armies clash by night.

As with Browning, Arnold offers a poem of psychological depth by presenting a monologue with an identified speaker (a woman, the object of the speaker’s professed love). And like “The Raven,” the poem offers an analysis of the individual reaction to nihilism. The speaker quite literally “stares into the abyss” and ponders what remains when faith and the certitude it gives have been lost. Along the way the poem presents several complex metaphors and Classical allusions. Ostensibly the poem ends by seeking solace in love, but the resolution—likely intentionally—seems an inadequate self-delusion.

9. “Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening” by Robert Frost (1923)

My little horse must think it queer To stop without a farmhouse near Between the woods and frozen lake The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake To ask if there is some mistake. The only other sound’s the sweep Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep, But I have promises to keep, And miles to go before I sleep, And miles to go before I sleep.

Stylistically, this poem is classic Frost: direct in its description, with simple, almost laconic language. But the simple surface presents a rich series of metaphors: the woods, the horse’s presumed thoughts, and the “sleep” referenced at the end. On one level, the speaker is transfixed by the beauty of the scene, but on another, like “Dover Beach,” the speaker here stares into the abyss and confronts the mystery its darkness presents.

10. “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks (1959)

The Pool Players. Seven at the Golden Shovel.

We real cool. We Left school. We

Lurk late. We Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We Die soon.

At a mere eight lines and twenty-four syllables (all of monosyllabic words), this poem packs the most punch into its sparse form with an explosion of rhyme, alliteration, anaphora, and staccato-like meter. The poem imagines pool players at a bar making various boasts, each one alluding to the Seven Deadly Sins, and offers a Biblical warning at the end: “The wages of sin is death.” Who are the cool-seeming “Pool Players” today and what do they do? What may be their end? The poem naturally leads to a host of ominous reflections and avenues for analysis.

Adam Sedia (b. 1984) lives in his native Northwest Indiana and practices law as a civil and appellate litigator. In addition to the Society’s publications, his poems and prose works have appeared in The Chained Muse Review, Indiana Voice Journal, and other literary journals. He is also a composer, and his musical works may be heard on his YouTube channel.

NOTE TO READERS: If you enjoyed this poem or other content, please consider making a donation to the Society of Classical Poets.

The Society of Classical Poets does not endorse any views expressed in individual poems or commentary.

CODEC Stories:

Share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

11 Responses

Wow! Adam. Grand slam. Great selections and terse, cogent, summary analyses that could serve as an introduction to a master class on poetry for college level students and even high school if the teacher were as enthusiastic about the subject as you are! Ask, “Choose one of the described poems and write a three-page reflection on its possible meaning(s) and how it might relate to your own life, thoughts and experience.”

If I were to suggest an additional poem it would be any number of those written by Emily Dickerson, many of which are provocativly enigmatic and multi-layered in meaning.

Excellent and eloquent as always, Adam.

Thank you! I thought it best to keep my summaries terse. Providing too much of my analysis would ruin the fun of analyzing the poems on one’s own.

I agonized over this list. I wanted to provide a nice array of styles and time periods, so I had to omit some poets and poems that would have fit well in this list.

I liked this compilation a lot, Adam. “Dover Beach is one of my all-time favorite poems, which I never tire of re-reading. Another favorite of mine is Dylan Thomas’ “A Refusal to Mourn…,” which also lends itself to deep analysis, Robert Frost’s dictum that to much explaining can ruin a poem notwithstanding.

This articulate, informative, and straightforward post by Adam is one of the reasons why the SCP is growing in popularity every single day. The teaching of good literature in the American public schools is now virtually dead or corrupted by left-liberalism and wokeism. Adam shows what real education in literature is supposed to do.

If any English teacher were to attempt to put together a syllabus for a poetry class using these ten excellent poems, and to explicate them with Adam’s succinct clarity, he would be chastised and dismissed by his supervisors. Even Brooks’s excellent “We Real Cool” would be off-limits as subject matter, because it presents “a negative, racist, and stereotypical picture of black ghetto life.” (No kidding — that’s the kind of thinking that dominates English departments today.)

You touch on an important point. Pedagogy is crucial, and our children are being deliberately kept from civilization’s greatest works. How is intellectual starvation any less a crime than physical starvation?

Once upon a time I wanted to be an academic but knew I would never survive in academia. Turns out, I learn later, that law has become just as woke. I really would like to turn back to my original passion and teach the world about great poetry. The SCP is doing a marvelous job on that with its “best of” series. I also hope to contribute more essays here.

Adam – Thank you for this marvelous and highly educational compilation. Amazingly, the one time that I studied poetry – for a two week period in a high school freshman English class – the last three poems on your list, along with “Mother to Son” by Langston Hughes, were the poems that stayed in my mind forever, and gave me the idea to try writing poetry a full fifty years later. This terrific work is indeed a brilliant example of SCP’s uniqueness.

Thank you for sharing your story. It’s not so much a case of “great minds think alike” as great poetry being immediately recognizable (it’s pretty wild that three of these poems were taught in your class). Reading great poetry was what inspired me to try my hand at it as well. Nothing is as inspiring as reading great work.

Adam, thank you for this stimulating contribution. My first guess at the poems that would be included was “My Last Duchess.” Imagine my delight to see that you agree! Does “We Real Cool” allude to all seven of the Deadly Sins? I recognized only pride (real cool), wrath (strike straight), sloth (left school), avarice (thin gin), and lust (jazz June).

The remaining two (gluttony and envy) had to be excluded from Brooks’s composition for aesthetic reasons. Her description is of young men who live the “fast life,” and who come to youthful death as a result of their living in a world of macho swaggering, wenching, drinking, and fighting.

Gluttony would not fit here, as it is not the most typical sin of such young men — and besides, gluttony is a more fitting subject for a comic poem. Envy is also not suited to the poem, since it is not an immediately visible sin, and is therefore not easy to depict. Besides, tough young guys are mostly known for their pride, arrogance, and truculence, while envy is usually associated with quiet little nerds.

Every decision in writing a poem is primarily based on aesthetic effect before anything else.

Adam, what an admirable job you’ve done with the choices made and the write ups… just enough information to intrigue and engage, but plenty of room left to explore. Wonderful!

Wow! It was as though we were walking through the forest and watching all the leaves change color and picking out which color is the best one holding your breath in wee of the view in the forest.

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Captcha loading... In order to pass the CAPTCHA please enable JavaScript.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

EH -- Researching Poems: Strategies for Poetry Research

- Find Articles

- Strategies for Poetry Research

Page Overview

This page addresses the research process -- the things that should be done before the actual writing of the paper -- and strategies for engaging in the process. Although this LibGuide focuses on researching poems or poetry, this particular page is more general in scope and is applicable to most lower-division college research assignments.

Before You Begin

Before beginning any research process, first be absolutely sure you know the requirements of the assignment. Things such as

- the date the completed project is due

- the due dates of any intermediate assignments, like turning in a working bibliography or notes

- the length requirement (minimum word count), if any

- the minimum number and types (for example, books or articles from scholarly, peer-reviewed journals) of sources required

These formal requirements are as much a part of the assignment as the paper itself. They form the box into which you must fit your work. Do not take them lightly.

When possible, it is helpful to subdivide the overall research process into phases, a tactic which

- makes the idea of research less intimidating because you are dealing with sections at a time rather than the whole process

- makes the process easier to manage

- gives a sense of accomplishment as you move from one phase to the next

Characteristics of a Well-written Paper

Although there are many details that must be given attention in writing a research paper, there are three major criteria which must be met. A well-written paper is

- Unified: the paper has only one major idea; or, if it seeks to address multiple points, one point is given priority and the others are subordinated to it.

- Coherent: the body of the paper presents its contents in a logical order easy for readers to follow; use of transitional phrases (in addition, because of this, therefore, etc.) between paragraphs and sentences is important.

- Complete: the paper delivers on everything it promises and does not leave questions in the mind of the reader; everything mentioned in the introduction is discussed somewhere in the paper; the conclusion does not introduce new ideas or anything not already addressed in the paper.

Basic Research Strategy

- How to Research From Pellissippi State Community College Libraries: discusses the principal components of a simple search strategy.

- Basic Research Strategies From Nassau Community College: a start-up guide for college level research that supplements the information in the preceding link. Tabs two, three, and four plus the Web Evaluation tab are the most useful for JSU students. As with any LibGuide originating from another campus, care must be taken to recognize the information which is applicable generally from that which applies solely to the Guide's home campus. .

- Information Literacy Tutorial From Nassau Community College: an elaboration on the material covered in the preceding link (also from NCC) which discusses that material in greater depth. The quizzes and surveys may be ignored.

Things to Keep in Mind

Although a research assignment can be daunting, there are things which can make the process less stressful, more manageable, and yield a better result. And they are generally applicable across all types and levels of research.

1. Be aware of the parameters of the assignment: topic selection options, due date, length requirement, source requirements. These form the box into which you must fit your work.

2. Treat the assignment as a series of components or stages rather than one undivided whole.

- devise a schedule for each task in the process: topic selection and refinement (background/overview information), source material from books (JaxCat), source material from journals (databases/Discovery), other sources (internet, interviews, non-print materials); the note-taking, drafting, and editing processes.

- stick to your timetable. Time can be on your side as a researcher, but only if you keep to your schedule and do not delay or put everything off until just before the assignment deadline.

3. Leave enough time between your final draft and the submission date of your work that you can do one final proofread after the paper is no longer "fresh" to you. You may find passages that need additional work because you see that what is on the page and what you meant to write are quite different. Even better, have a friend or classmate read your final draft before you submit it. A fresh pair of eyes sometimes has clearer vision.

4. If at any point in the process you encounter difficulties, consult a librarian. Hunters use guides; fishermen use guides. Explorers use guides. When you are doing research, you are an explorer in the realm of ideas; your librarian is your guide.

A Note on Sources

Research requires engagement with various types of sources.

- Primary sources: the thing itself, such as letters, diaries, documents, a painting, a sculpture; in lower-division literary research, usually a play, poem, or short story.

- Secondary sources: information about the primary source, such as books, essays, journal articles, although images and other media also might be included. Companions, dictionaries, and encyclopedias are secondary sources.

- Tertiary sources: things such as bibliographies, indexes, or electronic databases (minus the full text) which serve as guides to point researchers toward secondary sources. A full text database would be a combination of a secondary and tertiary source; some books have a bibliography of additional sources in the back.

Accessing sources requires going through various "information portals," each designed to principally support a certain type of content. Houston Cole Library provides four principal information portals:

- JaxCat online catalog: books, although other items such as journals, newspapers, DVDs, and musical scores also may be searched for.

- Electronic databases: journal articles, newspaper stories, interviews, reviews (and a few books; JaxCat still should be the "go-to" portal for books). JaxCat indexes records for the complete item: the book, journal, newspaper, CD but has no records for parts of the complete item: the article in the journal, the editorial in the newspaper, the song off the CD. Databases contain records for these things.

- Discovery Search: mostly journal articles, but also (some) books and (some) random internet pages. Discovery combines elements of the other three information portals and is especially useful for searches where one is researching a new or obscure topic about which little is likely to be written, or does not know where the desired information may be concentrated. Discovery is the only portal which permits simul-searching across databases provided by multiple vendors.

- Internet (Bing, Dogpile, DuckDuckGo, Google, etc.): primarily webpages, especially for businesses (.com), government divisions at all levels (.gov), or organizations (.org). as well as pages for primary source-type documents such as lesson plans and public-domain books. While book content (Google Books) and journal articles (Google Scholar) are accessible, these are not the strengths of the internet and more successful searches for this type of content can be performed through JaxCat and the databases.

NOTE: There is no predetermined hierarchy among these information portals as regards which one should be used most or gone to first. These considerations depend on the task at hand and will vary from assignment o assignment.

The link below provides further information on the different source types.

- Research Methods From Truckee Meadows Community College: a guide to basic research. The tab "What Type of Source?" presents an overview of the various types of information sources, identifying the advantages and disadvantages of each.

- << Previous: Find Books

- Last Updated: Sep 3, 2024 10:23 AM

- URL: https://libguides.jsu.edu/litresearchpoems

Poetry & Poets

Explore the beauty of poetry – discover the poet within

How To Write A Poetry Research Paper

Introduction

Writing a poetry research paper can be an intimidating task for students. Even for experienced writers, the process of writing a research paper on poetry can be daunting. However, there are a few helpful tips and guidelines that can help make the process easier. Writing a research paper on poetry requires the student to have an analytical understanding of the poet or poet’s work and to utilize multiple sources of evidence in order to make a convincing argument. Before starting the research paper, it is important to properly analyze the poem and to understand the form, structure, and language of the poem.

The process of writing a research paper requires numerous steps, beginning with researching the poet and poem. If a poet is unknown, the research process must be started by learning about their biography, other works, and their impact on society. With online databases, libraries, and archives the research process can move quickly. It is important to carefully document sources for later use when creating bibliographies for the paper. Once the process of researching the poem has been completed, the next step is to analyze the poem itself. It is important for the student to read the poem carefully in order to understand the meaning, as well as its tone, imagery, and metaphors. Furthermore, analyzing other poems by the same poet can help students observe patterns, trends, or elements of a poet’s work.

Outlining and Structure

Outlining the research paper is just as important as analyzing the poem itself. Many students make the mistake of not taking enough time to craft a detailed outline that follows the structure of the paper. An effective outline will make process of writing the research paper more efficient, allowing for ease of transitions between sections of the paper. When writing the paper, it is important to think through the structure of the paper and how to make a strong argument. Support for the argument should be based on concrete evidence, such as literary criticism, literary theory, and close readings of the poem. It is essential to have a clear argument that is consistent throughout the body of the paper.

Citing Sources

When writing a research paper it is also important to cite all sources that are used. The style used for citing sources will depend on the style guide indicated by the professor or the school’s guidelines. Whether using MLA, APA, or Chicago style, it is important to adhere to the style guide indicated in order to have a complete and well-written paper.

Once the research and outlining is complete, the process of drafting a poetry research paper can begin. When constructing the first draft, it is especially useful to re-read the poem and to recall evidence that supports the argument made about the poem. Additionally, it is important to proofread and edit the first draft in order to make the argument more clear and to check for any grammar or spelling errors.

Writing a research paper on poetry does not have to be a difficult task. By taking the time to properly research, analyze, and structure the paper, the process of writing a successful poetry research paper becomes easier. Following these steps— researching the poet, understanding the poem itself, outlining the paper, citing sources, and drafting the paper— will ensure a great and thorough paper is prepared.

Using Imagery and Metaphor

The use of imagery and metaphor is an essential element when writing poetry. Imagery can be used to provide vivid descriptions of scenes and characters, while metaphor can be used to create deeper meanings and analogies. Understanding the use of imagery and metaphor can help to break down the poem and discover hidden meanings. Students researching poetry should pay special attentions to the poetic devices used to further the story or allusions to other works, such as classical mythology. Paying close attention to the language, metaphors, and imagery used by the poet can help to uncover the true meaning of the poem. By breaking down the element of the poem and focusing on individual elements, it is much easier to make valid conclusions about the poem and its author.

Understanding Rhyme and Meter

Rhyme and meter are two of the most important and complex elements of poetry. These two poetic techniques are used to help the poet structure their poem to provide rhythm and flow. Most commonly, rhyme and meter help to provide emphasis to certain words or phrases to give them additional meaning. When analyzing poetry, it is important to pay attention to the written rhyme schemes and meter of the poem. There are various patterns of rhyme, such as couplets, tercets, and quatrains. Meter, usually governed by iambs and trochees, can give the poem an added sense of rhythm to further emphasize certain words, phrases, or thoughts.

Exploring Themes

Themes are the central ideas behind a poem. The themes of a poem can be subtle and can be found in the language and images used. Exploring the poem through a thematic analysis can help to identify the true meaning of the poem and the message that the poet is conveying. When researching a poem, it is important to identify the primary theme of the poem and to look for evidence in the poem that can be used to support the claim. By paying attention to the language of a poem, students can uncover the deeper meanings within the poem and can move past the literal interpretation of the poem.

Analyzing Discourse and Context

In addition to the written aspects of a poem, it is important to consider the historical and social context of the poem. The context of the poem can be used to further understand its deeper meanings and implications. Collingwood’s theory of re-enactment can be used to reconstruct the context of a poem in order to gain a deeper understanding of the poem. When researching a poem, it is important to consider the the time period in which the poem was written, the author’s other works, and the broader literary context of the poem. Examining the discourse used by the poet can help to uncover the true message of the poem and the impact on society at the time.

Finding Inspiration

When researching poetry, it is important for the student to find inspiration in the form of other authors, critics, and theorists. Studying the works of other authors can provide valuable insight into a poem and can inform the student’s own interpretations. In addition to studying critics and theorists, the student should also look to other poets and authors as sources of inspiration. The student can explore the works of similar poets or authors to learn how they use their poetic elements in their work. This can help students to gain insight into the language, imagery, and themes present in the poem being researched.

Minnie Walters

Minnie Walters is a passionate writer and lover of poetry. She has a deep knowledge and appreciation for the work of famous poets such as William Wordsworth, Emily Dickinson, Robert Frost, and many more. She hopes you will also fall in love with poetry!

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

A Full Guide to Writing a Perfect Poem Analysis Essay

01 October, 2020

14 minutes read

Author: Elizabeth Brown

Poem analysis is one of the most complicated essay types. It requires the utmost creativity and dedication. Even those who regularly attend a literary class and have enough experience in poem analysis essay elaboration may face considerable difficulties while dealing with the particular poem. The given article aims to provide the detailed guidelines on how to write a poem analysis, elucidate the main principles of writing the essay of the given type, and share with you the handy tips that will help you get the highest score for your poetry analysis. In addition to developing analysis skills, you would be able to take advantage of the poetry analysis essay example to base your poetry analysis essay on, as well as learn how to find a way out in case you have no motivation and your creative assignment must be presented on time.

What Is a Poetry Analysis Essay?

A poetry analysis essay is a type of creative write-up that implies reviewing a poem from different perspectives by dealing with its structural, artistic, and functional pieces. Since the poetry expresses very complicated feelings that may have different meanings depending on the backgrounds of both author and reader, it would not be enough just to focus on the text of the poem you are going to analyze. Poetry has a lot more complex structure and cannot be considered without its special rhythm, images, as well as implied and obvious sense.

While analyzing the poem, the students need to do in-depth research as to its content, taking into account the effect the poetry has or may have on the readers.

Preparing for the Poetry Analysis Writing

The process of preparation for the poem analysis essay writing is almost as important as writing itself. Without completing these stages, you may be at risk of failing your creative assignment. Learn them carefully to remember once and for good.

Thoroughly read the poem several times

The rereading of the poem assigned for analysis will help to catch its concepts and ideas. You will have a possibility to define the rhythm of the poem, its type, and list the techniques applied by the author.

While identifying the type of the poem, you need to define whether you are dealing with:

- Lyric poem – the one that elucidates feelings, experiences, and the emotional state of the author. It is usually short and doesn’t contain any narration;

- Limerick – consists of 5 lines, the first, second, and fifth of which rhyme with one another;

- Sonnet – a poem consisting of 14 lines characterized by an iambic pentameter. William Shakespeare wrote sonnets which have made him famous;

- Ode – 10-line poem aimed at praising someone or something;

- Haiku – a short 3-line poem originated from Japan. It reflects the deep sense hidden behind the ordinary phenomena and events of the physical world;

- Free-verse – poetry with no rhyme.

The type of the poem usually affects its structure and content, so it is important to be aware of all the recognized kinds to set a proper beginning to your poetry analysis.

Find out more about the poem background

Find as much information as possible about the author of the poem, the cultural background of the period it was written in, preludes to its creation, etc. All these data will help you get a better understanding of the poem’s sense and explain much to you in terms of the concepts the poem contains.

Define a subject matter of the poem

This is one of the most challenging tasks since as a rule, the subject matter of the poem isn’t clearly stated by the poets. They don’t want the readers to know immediately what their piece of writing is about and suggest everyone find something different between the lines.

What is the subject matter? In a nutshell, it is the main idea of the poem. Usually, a poem may have a couple of subjects, that is why it is important to list each of them.

In order to correctly identify the goals of a definite poem, you would need to dive into the in-depth research.

Check the historical background of the poetry. The author might have been inspired to write a poem based on some events that occurred in those times or people he met. The lines you analyze may be generated by his reaction to some epoch events. All this information can be easily found online.

Choose poem theories you will support

In the variety of ideas the poem may convey, it is important to stick to only several most important messages you think the author wanted to share with the readers. Each of the listed ideas must be supported by the corresponding evidence as proof of your opinion.

The poetry analysis essay format allows elaborating on several theses that have the most value and weight. Try to build your writing not only on the pure facts that are obvious from the context but also your emotions and feelings the analyzed lines provoke in you.

How to Choose a Poem to Analyze?

If you are free to choose the piece of writing you will base your poem analysis essay on, it is better to select the one you are already familiar with. This may be your favorite poem or one that you have read and analyzed before. In case you face difficulties choosing the subject area of a particular poem, then the best way will be to focus on the idea you feel most confident about. In such a way, you would be able to elaborate on the topic and describe it more precisely.

Now, when you are familiar with the notion of the poetry analysis essay, it’s high time to proceed to poem analysis essay outline. Follow the steps mentioned below to ensure a brilliant structure to your creative assignment.

Best Poem Analysis Essay Topics

- Mother To Son Poem Analysis

- We Real Cool Poem Analysis

- Invictus Poem Analysis

- Richard Cory Poem Analysis

- Ozymandias Poem Analysis

- Barbie Doll Poem Analysis

- Caged Bird Poem Analysis

- Ulysses Poem Analysis

- Dover Beach Poem Analysis

- Annabelle Lee Poem Analysis

- Daddy Poem Analysis

- The Raven Poem Analysis

- The Second Coming Poem Analysis

- Still I Rise Poem Analysis

- If Poem Analysis

- Fire And Ice Poem Analysis

- My Papa’S Waltz Poem Analysis

- Harlem Poem Analysis

- Kubla Khan Poem Analysis

- I Too Poem Analysis

- The Juggler Poem Analysis

- The Fish Poem Analysis

- Jabberwocky Poem Analysis

- Charge Of The Light Brigade Poem Analysis

- The Road Not Taken Poem Analysis

- Landscape With The Fall Of Icarus Poem Analysis

- The History Teacher Poem Analysis

- One Art Poem Analysis

- The Wanderer Poem Analysis

- We Wear The Mask Poem Analysis

- There Will Come Soft Rains Poem Analysis

- Digging Poem Analysis

- The Highwayman Poem Analysis

- The Tyger Poem Analysis

- London Poem Analysis

- Sympathy Poem Analysis

- I Am Joaquin Poem Analysis

- This Is Just To Say Poem Analysis

- Sex Without Love Poem Analysis

- Strange Fruit Poem Analysis

- Dulce Et Decorum Est Poem Analysis

- Emily Dickinson Poem Analysis

- The Flea Poem Analysis

- The Lamb Poem Analysis

- Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night Poem Analysis

- My Last Duchess Poetry Analysis

Poem Analysis Essay Outline

As has already been stated, a poetry analysis essay is considered one of the most challenging tasks for the students. Despite the difficulties you may face while dealing with it, the structure of the given type of essay is quite simple. It consists of the introduction, body paragraphs, and the conclusion. In order to get a better understanding of the poem analysis essay structure, check the brief guidelines below.

Introduction

This will be the first section of your essay. The main purpose of the introductory paragraph is to give a reader an idea of what the essay is about and what theses it conveys. The introduction should start with the title of the essay and end with the thesis statement.

The main goal of the introduction is to make readers feel intrigued about the whole concept of the essay and serve as a hook to grab their attention. Include some interesting information about the author, the historical background of the poem, some poem trivia, etc. There is no need to make the introduction too extensive. On the contrary, it should be brief and logical.

Body Paragraphs

The body section should form the main part of poetry analysis. Make sure you have determined a clear focus for your analysis and are ready to elaborate on the main message and meaning of the poem. Mention the tone of the poetry, its speaker, try to describe the recipient of the poem’s idea. Don’t forget to identify the poetic devices and language the author uses to reach the main goals. Describe the imagery and symbolism of the poem, its sound and rhythm.

Try not to stick to too many ideas in your body section, since it may make your essay difficult to understand and too chaotic to perceive. Generalization, however, is also not welcomed. Try to be specific in the description of your perspective.

Make sure the transitions between your paragraphs are smooth and logical to make your essay flow coherent and easy to catch.

In a nutshell, the essay conclusion is a paraphrased thesis statement. Mention it again but in different words to remind the readers of the main purpose of your essay. Sum up the key claims and stress the most important information. The conclusion cannot contain any new ideas and should be used to create a strong impact on the reader. This is your last chance to share your opinion with the audience and convince them your essay is worth readers’ attention.

Problems with writing Your Poem Analysis Essay? Try our Essay Writer Service!

Poem Analysis Essay Examples

A good poem analysis essay example may serve as a real magic wand to your creative assignment. You may take a look at the structure the other essay authors have used, follow their tone, and get a great share of inspiration and motivation.

Check several poetry analysis essay examples that may be of great assistance:

- https://study.com/academy/lesson/poetry-analysis-essay-example-for-english-literature.html

- https://www.slideshare.net/mariefincher/poetry-analysis-essay

Writing Tips for a Poetry Analysis Essay

If you read carefully all the instructions on how to write a poetry analysis essay provided above, you have probably realized that this is not the easiest assignment on Earth. However, you cannot fail and should try your best to present a brilliant essay to get the highest score. To make your life even easier, check these handy tips on how to analysis poetry with a few little steps.

- In case you have a chance to choose a poem for analysis by yourself, try to focus on one you are familiar with, you are interested in, or your favorite one. The writing process will be smooth and easy in case you are working on the task you truly enjoy.

- Before you proceed to the analysis itself, read the poem out loud to your colleague or just to yourself. It will help you find out some hidden details and senses that may result in new ideas.

- Always check the meaning of words you don’t know. Poetry is quite a tricky phenomenon where a single word or phrase can completely change the meaning of the whole piece.

- Bother to double check if the conclusion of your essay is based on a single idea and is logically linked to the main body. Such an approach will demonstrate your certain focus and clearly elucidate your views.

- Read between the lines. Poetry is about senses and emotions – it rarely contains one clearly stated subject matter. Describe the hidden meanings and mention the feelings this has provoked in you. Try to elaborate a full picture that would be based on what is said and what is meant.

Write a Poetry Analysis Essay with HandmadeWriting

You may have hundreds of reasons why you can’t write a brilliant poem analysis essay. In addition to the fact that it is one of the most complicated creative assignments, you can have some personal issues. It can be anything from lots of homework, a part-time job, personal problems, lack of time, or just the absence of motivation. In any case, your main task is not to let all these factors influence your reputation and grades. A perfect way out may be asking the real pros of essay writing for professional help.

There are a lot of benefits why you should refer to the professional writing agencies in case you are not in the mood for elaborating your poetry analysis essay. We will only state the most important ones:

- You can be 100% sure your poem analysis essay will be completed brilliantly. All the research processes, outlines, structuring, editing, and proofreading will be performed instead of you.

- You will get an absolutely unique plagiarism-free piece of writing that deserves the highest score.

- All the authors are extremely creative, talented, and simply in love with poetry. Just tell them what poetry you would like to build your analysis on and enjoy a smooth essay with the logical structure and amazing content.

- Formatting will be done professionally and without any effort from your side. No need to waste your time on such a boring activity.

As you see, there are a lot of advantages to ordering your poetry analysis essay from HandmadeWriting . Having such a perfect essay example now will contribute to your inspiration and professional growth in future.

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

Poetry Explained

How to Write a Poetry Essay (Complete Guide)

Unlock success in poetry essays with our comprehensive guide. Uncover the process to help aid understanding of how best to create a poetry essay.

While many of us read poetry for pleasure, it is undeniable that many poetry readers do so in the knowledge that they will be assessed on the text they are reading, either in an exam, for homework, or for a piece of coursework. This is clearly a daunting task for many, and lots of students don’t even know where to begin. We’re here to help! This guide will take you through all the necessary steps so that you can plan and write great poetry essays every time. If you’re still getting to grips with the different techniques, terms, or some other aspect of poetry, then check out our other available resources at the bottom of this page.

This Guide was Created by Joe Samantaria

Degree in English and Related Literature, and a Masters in Irish Literature

Upon completion of his degrees, Joe is an English tutor and counts W.B. Yeats , Emily Brontë , and Federico Garcia Lorca among his favorite poets. He has helped tutor hundreds of students with poetry and aims to do the same for readers and Poetry + users on Poem Analysis.

How to Write a Poetry Essay

- 1 Before You Start…

- 2 Introductions

- 3 Main Paragraphs

- 4 Conclusions

- 6 Other Resources

Before You Start…

Before we begin, we must address the fact that all poetry essays are different from one another on account of different academic levels, whether or not the essay pertains to one poem or multiple, and the intended length of the essay. That is before we even contend with the countless variations and distinctions between individual poems. Thus, it is impossible to produce a single, one-size-fits-all template for writing great essays on poetry because the criteria for such an essay are not universal. This guide is, therefore, designed to help you go about writing a simple essay on a single poem, which comes to roughly 1000-1200 words in length. We have designed it this way to mirror the requirements of as many students around the world as possible. It is our intention to write another guide on how to write a comparative poetry essay at a later date. Finally, we would like to stress the fact that this guide is exactly that: a guide. It is not a set of restrictive rules but rather a means of helping you get to grips with writing poetry essays. Think of it more like a recipe that, once practiced a few times, can be modified and adapted as you see fit.

The first and most obvious starting point is the poem itself and there are some important things to do at this stage before you even begin contemplating writing your essay. Naturally, these things will depend on the nature of the essay you are required to write.

- Is the poem one you are familiar with?

- Do you know anything about the context of the poem or the poet?

- How much time do you have to complete the essay?

- Do you have access to books or the internet?

These questions matter because they will determine the type, length, and scope of the essay you write. Naturally, an essay written under timed conditions about an unfamiliar poem will look very different from one written about a poem known to you. Likewise, teachers and examiners will expect different things from these essays and will mark them accordingly.

As this article pertains to writing a poverty essay, we’re going to assume you have a grasp of the basics of understanding the poems themselves. There is a plethora of materials available that can help you analyze poetry if you need to, and thousands of analyzed poems are available right here. For the sake of clarity, we advise you to use these tools to help you get to grips with the poem you intend to write about before you ever sit down to actually produce an essay. As we have said, the amount of time spent pondering the poem will depend on the context of the essay. If you are writing a coursework-style question over many weeks, then you should spend hours analyzing the poem and reading extensively about its context. If, however, you are writing an essay in an exam on a poem you have never seen before, you should perhaps take 10-15% of the allotted time analyzing the poem before you start writing.

The Question

Once you have spent enough time analyzing the poem and identifying its key features and themes, you can turn your attention to the question. It is highly unlikely that you will simply be asked to “analyze this poem.” That would be too simple on the one hand and far too broad on the other.

More likely, you will be asked to analyze a particular aspect of the poem, usually pertaining to its message, themes, or meaning. There are numerous ways examiners can express these questions, so we have outlined some common types of questions below.

- Explore the poet’s presentation of…

- How does the poet present…

- Explore the ways the writer portrays their thoughts about…

These are all similar ways of achieving the same result. In each case, the examiner requires that you analyze the devices used by the poet and attempt to tie the effect those devices have to the poet’s broader intentions or meaning.

Some students prefer reading the question before they read the poem, so they can better focus their analytical eye on devices and features that directly relate to the question they are being asked. This approach has its merits, especially for poems that you have not previously seen. However, be wary of focusing too much on a single element of a poem, particularly if it is one you may be asked to write about again in a later exam. It is no good knowing only how a poem links to the theme of revenge if you will later be asked to explore its presentation of time.

Essay plans can help focus students’ attention when they’re under pressure and give them a degree of confidence while they’re writing. In basic terms, a plan needs the following elements:

- An overarching answer to the question (this will form the basis of your introduction)

- A series of specific, identifiable poetic devices ( metaphors , caesura , juxtaposition , etc) you have found in the poem

- Ideas about how these devices link to the poem’s messages or themes.

- Some pieces of relevant context (depending on whether you need it for your type of question)

In terms of layout, we do not want to be too prescriptive. Some students prefer to bullet-point their ideas, and others like to separate them by paragraph. If you use the latter approach, you should aim for:

- 1 Introduction

- 4-5 Main paragraphs

- 1 Conclusion

Finally, the length and detail of your plan should be dictated by the nature of the essay you are doing. If you are under exam conditions, you should not spend too much time writing a plan, as you will need that time for the essay itself. Conversely, if you are not under time pressure, you should take your time to really build out your plan and fill in the details.

Introductions

If you have followed all the steps to this point, you should be ready to start writing your essay. All good essays begin with an introduction, so that is where we shall start.

When it comes to introductions, the clue is in the name: this is the place for you to introduce your ideas and answer the question in broad terms. This means that you don’t need to go into too much detail, as you’ll be doing that in the main body of the essay. That means you don’t need quotes, and you’re unlikely to need to quote anything from the poem yet. One thing to remember is that you should mention both the poet’s name and the poem’s title in your introduction. This might seem unnecessary, but it is a good habit to get into, especially if you are writing an essay in which other questions/poems are available to choose from.

As we mentioned earlier, you are unlikely to get a question that simply asks you to analyze a poem in its entirety, with no specific angle. More likely, you’ll be asked to write an essay about a particular thematic element of the poem. Your introduction should reflect this. However, many students fall into the trap of simply regurgitating the question without offering anything more. For example, a question might ask you to explore a poet’s presentation of love, memory, loss, or conflict . You should avoid the temptation to simply hand these terms back in your introduction without expanding upon them. You will get a chance to see this in action below.

Let’s say we were given the following question:

Explore Patrick Kavanagh’s presentation of loss and memory in Memory of My Father

Taking on board the earlier advice, you should hopefully produce an introduction similar to the one written below.

Patrick Kavanagh presents loss as an inescapable fact of existence and subverts the readers’ expectations of memory by implying that memories can cause immense pain, even if they feature loved ones. This essay will argue that Memory of My Father depicts loss to be cyclical and thus emphasizes the difficulties that inevitably occur in the early stages of grief.

As you can see, the introduction is fairly condensed and does not attempt to analyze any specific poetic elements. There will be plenty of time for that as the essay progresses. Similarly, the introduction does not simply repeat the words ‘loss’ and ‘memory’ from the question but expands upon them and offers a glimpse of the kind of interpretation that will follow without providing too much unnecessary detail at this early stage.

Main Paragraphs

Now, we come to the main body of the essay, the quality of which will ultimately determine the strength of our essay. This section should comprise of 4-5 paragraphs, and each of these should analyze an aspect of the poem and then link the effect that aspect creates to the poem’s themes or message. They can also draw upon context when relevant if that is a required component of your particular essay.

There are a few things to consider when writing analytical paragraphs and many different templates for doing so, some of which are listed below.

- PEE (Point-Evidence-Explain)

- PEA (Point-Evidence-Analysis)

- PETAL (Point-Evidence-Technique-Analysis-Link)

- IQA (Identify-Quote-Analyze)

- PEEL (Point-Evidence-Explain-Link)

Some of these may be familiar to you, and they all have their merits. As you can see, there are all effective variations of the same thing. Some might use different terms or change the order, but it is possible to write great paragraphs using all of them.

One of the most important aspects of writing these kind of paragraphs is selecting the features you will be identifying and analyzing. A full list of poetic features with explanations can be found here. If you have done your plan correctly, you should have already identified a series of poetic devices and begun to think about how they link to the poem’s themes.

It is important to remember that, when analyzing poetry, everything is fair game! You can analyze the language, structure, shape, and punctuation of the poem. Try not to rely too heavily on any single type of paragraph. For instance, if you have written three paragraphs about linguistic features ( similes , hyperbole , alliteration , etc), then try to write your next one about a structural device ( rhyme scheme , enjambment , meter , etc).

Regardless of what structure you are using, you should remember that multiple interpretations are not only acceptable but actively encouraged. Techniques can create effects that link to the poem’s message or themes in both complementary and entirely contrasting ways. All these possibilities should find their way into your essay. You are not writing a legal argument that must be utterly watertight – you are interpreting a subjective piece of art.

It is important to provide evidence for your points in the form of either a direct quotation or, when appropriate, a reference to specific lines or stanzas . For instance, if you are analyzing a strict rhyme scheme, you do not need to quote every rhyming word. Instead, you can simply name the rhyme scheme as, for example, AABB , and then specify whether or not this rhyme scheme is applied consistently throughout the poem or not. When you are quoting a section from the poem, you should endeavor to embed your quotation within your line so that your paragraph flows and can be read without cause for confusion.