An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Marital Dissolution Among Interracial Couples

Yuanting zhang.

National Institute of Health moc.eticxe@tnauygnahz

Jennifer Van Hook

Pennsylvania State University ude.usp.pop@koohnavj

Increases in interracial marriage have been interpreted as reflecting reduced social distance among racial and ethnic groups, but little is known about the stability of interracial marriages. Using six panels of Survey of Income and Program Participation (N = 23,139 married couples), we found that interracial marriages are less stable than endogamous marriages, but these findings did not hold up consistently. After controlling for couple characteristics, the risk of divorce or separation among interracial couples was similar to the more-divorce-prone origin group. Although marital dissolution was found to be strongly associated with race/ethnicity, the results failed to provide evidence that interracial marriage is associated with an elevated risk of marital dissolution.

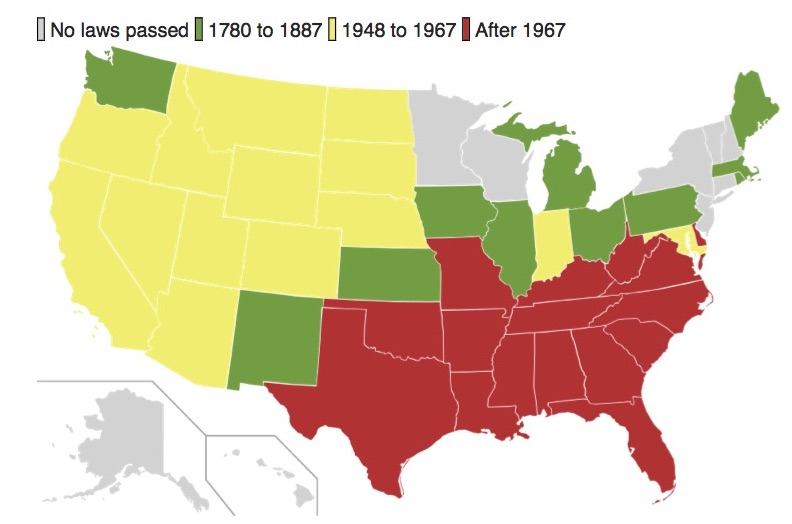

Interracial marriage has long been a topic of interest and controversy in American history and has received a great deal of attention in the family research literature ( Fu, 2006 ; Kalmijn, 1991 ; Tucker & Mitchell-Kernan, 1990 ; Yancey, 2007 ). The antimiscegenation laws in the United States, enacted mainly to prevent Black-White interracial marriages, were struck down in a 1967 Supreme Court decision ( Sollors, 2000 ). Since then interracial marriage has increased dramatically from less than 1% in 1970 among all married couples to more than 5% in 2000. Children living in such families have quadrupled to more than 3 million between 1970 and 2000 ( Lee & Edmonston, 2005 ). Such changes have been interpreted as signifying the fading of racial boundaries in U.S. society ( Qian & Lichter, 2007 ) and as indicating immigrant structural assimilation ( Alba & Golden, 1986 ; Gordon, 1964 ).

Enthusiasm about increases in the prevalence of interracial marriages, however, may be dampened if such marriages are highly likely to break up. Partially because interracial marriage remains a relatively new phenomenon, few studies have assessed the stability of interracial marriages or offered theoretical guidance on this issue. Existing work tends to be dated and focused primarily on Black-White marriages. As a result, little is known about relative stability of such marriages in contemporary American society ( Joyner & Kao, 2005 ). As the U.S. population has grown increasingly diverse, it is important to update prior research to include interracial marriages involving Asians and Hispanics, especially given that they are more likely to intermarry (with non-Hispanic Whites) than are Blacks ( Qian, 1997 ). Also, interracial marriages involving America’s newest minority groups may operate differently than those involving Blacks because of the high levels of racism in the United States directed specifically toward Blacks, which is likely to stress Black-White marriages. In the present study, we analyze the stability of interracial marriages involving Blacks, Asians, and Hispanics over the period 1990 to 2001 by analyzing data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

Background & Theory

Existing work on marital dissolution among interracial couples focused primarily on divorce within Black-White marriages ( Monahan, 1970 ; Rankin & Maneker, 1987 ) or specialized populations such as Hawaiians ( Fu, 2006 ; Jones, 1996 ). Although one study of couples in Iowa found Black-White marriages to be more stable than Black-Black marriages ( Monahan, 1970 ), other studies concluded that interracial marriages were less stable in Hawaii ( Fu, 2006 ; Jones, 1996 ) and in the Netherlands ( Kalmijn, de Graaf, & Janssen, 2005 ). Further, prior research suggested that the stability of interracial marriages differed by gender. On the basis of a California sample, Rankin and Maneker (1987) found that Black men-White women marriages had shorter durations compared to other types of pairings.

Primarily two theoretical frameworks have guided research on the instability of interracial marriages. The first concerns the role of homogamy and the second involves ideas about ethnic convergence of divorce propensities. Sociologists have long found that people tend to date and marry someone who shares a similar cultural background and social economic status, and in many cases someone in the same neighborhood, school, or workplace. Among the explanations for homogamy, geographical propinquity and personal preferences were found to be the two underpinning factors ( Stevens, 1991 ). The pool of potential partners is determined by local demographic and geographic composition, and within this pool people generally prefer someone who is similar to them ( Kalmijn, 1998 ; Stevens & Swicegood, 1987 ).

The basic assumption of the homogamy perspective is that couples with similar characteristics have fewer misunderstandings, less conflict, and enjoy greater support from extended family and friends. Consistent with this idea, endogamous marriages were found to be more stable than those involving couples who were dissimilar on socially significant traits (e.g. age, education, race/ethnicity, and religion) ( Bahr, 1981 ; Jones, 1996 ; Kalmijn et al., 2005 ). Kalmijn (1998) found that interracial couples in particular could face group sanctions if racial heterogamy threatened in-group solidarity. Indeed, interracial couples often faced pressures in the forms of strangers’ stares and anger, and even rejection by their own racial groups because of their “betrayal” and non-conforming behavior of “crossing the line” ( Billingsley, 1968 ). This may be particularly salient for Black-White marriages, as Yancey (2007) found that social discrimination against such couples could be especially harsh. The enduring social boundaries specifically between Blacks and Whites became apparent in the continuation of low levels of Black-White intermarriage and higher levels of intermarriage between non-Hispanic Whites, Asians, and Hispanics, especially among those with higher levels of socioeconomic status ( Qian & Lichter, 2007 ). Other studies have corroborated this view. In their study of multiracial identification among those with Black, Asian, or Hispanic backgrounds, Lee and Bean (2007) found that those with Black backgrounds more consistently identified as Black and not multiracial (similar to the “one-drop” rule as applied in the past), whereas those with Hispanic and, especially, Asian backgrounds exhibited more flexibility and choice in racial/ethnic identification and were more likely to identify as multiracial. Lee and Bean (2007) concluded that these patterns illustrated the salience of the color line that continues to divide Blacks from non-Blacks in U.S. society.

The homogamy perspective predicts that interracial marriages will be less stable than same-race marriages. Thus, Black-White marriages are expected to be more likely to divorce than either Black or White endogamous marriages; similarly, Asian-White marriages are expected to be more likely to divorce than either Asian or White endogamous marriages. The homogamy perspective further leads to the expectation that the stronger the racial boundary of the two groups represented in the couple, the greater the risk of divorce. Thus, Black-White marriages are expected to be at greater risk of divorce than Hispanic-White or Asian-White marriages.

An alternative to the homogamy perspective is the ethnic divorce convergence perspective. Developed by Jones (1996) , “ethnic divorce convergence” perspective theorized that divorce propensities of interracial couples were likely to fall between the divorce patterns of the involved racial groups. This contrasts with the homogamy hypothesis, which predicts higher levels of divorce for interracially married couples. On the basis of his empirical tests using Australian and Hawaiian data, Jones (1994 , 1996) argued that divorce patterns for mixed marriages reflected the interplay of the divorce cultures of the ethnic groups involved, instead of following the divorce culture of the dominant group. For example, he found that Chinese-White couple divorce rates fell somewhere in between divorce rates of Chinese and White endogamous marriages. Similarly, Kalmijn et al. (2005) also reported that interracial marriage divorce rates tended to fall in between the two groups in the Netherlands.

In the United States, Blacks have had higher divorce rates than Whites, whereas Hispanics and Asians have had lower divorce rates ( Frisbie, Bean, & Eberstein, 1980 ; Sweezy & Tiefenthaler, 1996 ), although there have been important differences among the various Hispanic subgroups, with Puerto Ricans having had the highest divorce rates and Cubans, Mexicans, and Mexican Americans the lowest ( Landale & Ogena, 1995 ). Thus, the ethnic convergence hypothesis would lead to the expectation that Black-White interracial marriages will be less likely to dissolve than Black-Black marriages but more likely than White-White marriages. Similarly, Hispanic-White and Asian-White marriages would be expected to be more likely to dissolve than Hispanic or Asian endogamous marriages but less likely than White endogamous marriages. Jones’ (1996) hypothesis could be viewed especially important for couples involving a combination of immigrants and natives because immigrants have had a tendency toward lower levels of divorce than natives ( Frisbie, Opitz, & Kelly, 1985 ), a difference that has been interpreted as reflecting cultural differences ( Oropesa & Landale, 2004 ). Therefore, according to the ethnic convergence hypothesis, immigrant-native marriages would be expected to have divorce risks that fall between those of immigrant-immigrant marriages and native-native marriages. Also, if Hispanic and Asian interracial marriages are less likely to divorce, this could be because so many of these marriages involve immigrants. After controlling for immigration characteristics, the effects of interracial marriage should diminish for these couples.

To assess the homogamy and ethnic convergence hypotheses, it is important to control for correlated factors. Individual-level socioeconomic and demographic characteristics are associated with interracial marriage and are important predictors of divorce. Age at marriage has been one of the most consistent key determinants for predicting marital stability ( South, 1995 ), which also have differed by racial group ( Phillips & Sweeney, 2006 ). Also, people with medium levels of education ( Carter & Glick, 1970 ) and women with higher incomes ( Ruggles, 1997 ) have been more likely to divorce or separate than others. Finally, while having young child(ren) has been shown to increase marital stability, this effect often decreased as the child(ren) grew older ( Cherlin, 1977 ).

In addition to the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of individuals, it is critical to control for couple-level characteristics. The homogamy perspective stresses that partner differences in any socially significant characteristics—not just race—may increase the risk of divorce, and spouses in interracial couples may differ on multiple characteristics. For example, Tucker and Mitchell-Kernan (1990) found that the age gap was larger for interracially married couples than other couples. Partners in interracial couples may also differ with respect to nativity and citizenship. Interracial marriages between immigrants and U.S.-born natives may be at greater risk of divorce because of partner differences in their reasons for entering the relationship. Kalmijn et al. (2005) found that larger cultural differences between the husband and wife increased the risk of divorce. In addition, marriage to U.S. citizens may serve as a legal means to immigrate for many foreigners. Such marriages may be motivated by the desire to obtain U.S. citizenship rather than love or companionship, as evidenced in many cases in France ( Neyrand & M'Sili, 1998 ) and the Netherlands ( Kalmijn et al., 2005 ).

Finally, group-level characteristics, such as marriage cohort, region of residence, religion, and women's changing status, may be associated with divorce or separation ( Trent & South, 1989 ). For example, interracial marriage has been more prevalent in the West than other parts of the country ( Tucker & Mitchell-Kernan, 1990 ), and marital instability has been more common in the West than other regions, although this relationship has varied by race ( Sweeney & Phillips, 2004 ) and has weakened over the years ( Castro Martin & Bumpass, 1989 ).

To summarize, the homogamy perspective leads to the following hypotheses:

- Hypothesis 1: Interracial marriages will be less stable than similar endogamous marriages.

- Hypothesis 2: Black-White couples will have higher risks of marital dissolution than other interracial couples.

- Hypothesis 3: Interracial couples will have higher risks of marital dissolution than endogamous couples among both of the respective origin groups.

On the other hand, the ethnic convergence hypothesis leads to the expectations that:

- d Hypothesis 4: Interracial couples have risks of marital dissolution that fall between those of the respective origin groups.

- e Hypothesis 5: Among Hispanics and Asians, differences in the risk of marital dissolution between interracial and endogamous couples will be partially explained by differences in nativity and citizenship.

Six panels (1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1996, and 2001) of the SIPP were pooled in order to study marital dissolution patterns among interracially married immigrants and natives. The SIPP sample is a multistage-stratified sample of the U.S. civilian non-institutionalized population with sample sizes ranging from approximately 14,000 to 36,700 interviewed households (United States Census Bureau, n.d.). Each of the six SIPP panels includes a separate, independent sample that was interviewed every four months for roughly three to four years. For example, the 1990 panel includes individuals who were interviewed up to 8 times over a period of 32 months between 1990 and 1992, and the 1991 Panel includes an entirely new sample interviewed up to 8 times over a period of 32 months between 1991 and 1993. The respondents in the 1992, 1993, 1996, and 2001 panels were interviewed every 4 months over 40, 36, 48, and 36 months, respectively. Although the SIPP was not designed to study the same marriage cohorts, and it only followed respondents for 3 to 4 years, it provides a unique snapshot of the marital stability of interracially married couples. The advantages of using the SIPP are apparent. First, it followed individuals (and married couples) over time even if they left their original households and formed new ones. Secondly the SIPP included time-varying information on marital status as well as standard social, demographic, and economic variables (these questions were asked at every interview every 4 months). Third, it included a retrospective marriage and migration history for all adult household members.

By combining six SIPP panels, we amassed a sufficiently large sample to examine the stability of interracial marriages separately for couples of various racial/ethnic group combinations. The data used for this paper are mainly couple-level prospective data, which followed couples over time during the 3- to 4-year study period until they divorced/separated, dropped out, or were censored. The analytical sample was first restricted to 29,171 couples with at least one member who was between the ages 18 to 44 and in a first marriage at the beginning of the SIPP panel or were married for the first time during the ongoing waves of the panel. Because of limitations in sample size, Native American endogamous marriages ( n = 91) and White-Native American marriages ( n = 232) were excluded. We further restricted our sample by removing 5,709 couples on the basis of censoring or missing or invalid values for the time or any of our explanatory variables; thus, the final sample contains 23,139 couples.

Key Measures

The dependent variable was the dissolution of marriage by either divorce or separation for all couples. The timing of marital dissolution was determined prospectively by observing year and month in which a married respondent was coded as having changed marital status to divorced or separated. Widowed respondents were censored at the time they were no longer married (or were dropped from the sample). First marriage was defined as an ongoing first marriage at the beginning of the SIPP panel or transition from never married to married for the first time during the SIPP panel. The duration of marriage (measured in days) was obtained by examining the difference between the date of first marriage and the date of marital dissolution. For presentation, the descriptive statistics on marriage duration were reported in years instead of days. Marital duration is implicitly embedded in all of our Cox Proportional Hazards models (duration is not included as an independent variable because the partial likelihood function takes into account the ordering of failure times) ( Box-Steffensmeier & Jones, 2004 ). Interracial couples were identified as those married to a person of a different race or ethnicity. We opted to use broadly defined racial/ethnic categories: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Asian, Hispanic, and other minority. We refer to non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black with the shortened terms “White” and “Black” throughout the remainder of the paper. Marriage types were later further classified by gender (e.g., White husband-Black wife, Black husband-White wife, etc.).

Control Variables

A set of six dummy variables was included in the models to indicate the time period (in five-year intervals) the couple got married (e.g., before 1970, 1970 - 1974, . . . , 1990 - 1994, and 1995 or later). Region of residence at the time of the first interview was classified according to the U.S. Census Bureau standard (Midwest, Northeast, South, and West). Because age at first marriage showed clear non-linearity in our preliminary analysis, we opted to code it as a series of binary variables. The age difference between the spouses was categorized in the same fashion as by Phillips and Sweeney (2006) : husband more than 5 years older than the wife, less than 2 years younger to 5 years older than the wife, or more than 2 years younger than the wife. To measure educational heterogamy, we distinguished between couples for whom the husband had more or less education than his wife. For couples who have the same educational levels, we distinguished among four categories: less than high school, high school, some college, and college or above. We controlled for the wife's income (logged) by summing across income from the previous 4 months at the time of the first interview. Because some respondents have a true zero for their income, log (income + 1) was used instead of log (income). We reported the unlogged mean income (summed over 4 months) in our descriptive statistics. We also controlled for the number of preschool-aged (0 to 4 years old) children living with the couple and both the citizenship and nativity status of the couple. Specifically, we distinguished among couples in which (a) both spouses were foreign born and at least one was a non-citizen; (b) both spouses were foreign-born naturalized citizens; (c) one spouse was a non-citizen but the other was native; (d) one spouse was a naturalized citizen and the other was native; and (e) both spouses were native (born in the United States).

Data Analysis

Cox Proportional Hazards models were used to estimate the relationship between interracial marriage and the hazard of dissolution. All independent variables were non-time-dependent covariates. Cox Proportional Hazards models assume that the underlying hazard rate (rather than survival time) is a function of the independent variables (covariates) and is thus proportional to the hazard function for the baseline category ( Allison, 1995 ). The proportional hazards models are robust and make no parametric assumptions concerning the nature or shape of the underlying survival distribution ( Allison, 1995 ).

Descriptive Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of all the couples that are included in the final analytical sample ( N = 23,139). Approximately 2,059 couples (8.9% of the sample) divorced or separated during the time interval they were followed in the SIPP. The majority (93.5%) of the couples in our sample were endogamous, including 77.4% White-White, 6.4% Black-Black, 7% Hispanic-Hispanic, and 2.7% Asian-Asian couples. The remaining 6.5% of couples were interracially married (including 1% White-Black, 3.5% White-Hispanic, and 1.4% White-Asian pairings, as well as 0.6% of all types of minority-minority marriages combined). Consistent with prior studies (e.g., Qian, 1997 ), there are distinct racial/ethnic differences in being in an interracial marriage (results not shown). Blacks are substantially less likely than Hispanics or Asians to have a White spouse (10.1% vs. 23.5% and 24.6%, respectively).

Potential Predictors of Marital Dissolution by Marriage Type: Descriptive Statistics

| All Couples ( = 23,139) | Endogamous Couples ( = 21,547) | Interracial Couples ( = 1,592) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ||||||

| Marriage Duration | 12.500 | 6.950 | 12.619 | 7.000 | 10.449 | 5.914 |

| Endogamous Couples | ||||||

| White-White | .774 | .828 | ||||

| Black-Black | .064 | .069 | ||||

| Hispanic-Hispanic | .070 | .074 | ||||

| Asian-Asian | .027 | .029 | ||||

| Interracial Couples | ||||||

| All | .065 | 1.000 | ||||

| White H-Black W | .004 | .067 | ||||

| Black H-White W | .006 | .091 | ||||

| White H-Hispanic W | .018 | .281 | ||||

| Hispanic H-White W | .017 | .265 | ||||

| White H-Asian W | .009 | .136 | ||||

| Asian H-White W | .005 | .069 | ||||

| Minority-Minority | .006 | .092 | ||||

| Marriage Cohort | ||||||

| Before 1970 | .063 | .066 | .014 | |||

| 1970 - 1974 | .123 | .127 | .066 | |||

| 1975 - 1979 | .162 | .166 | .111 | |||

| 1980 - 1984 | .225 | .226 | .213 | |||

| 1985 - 1989 | .273 | .269 | .339 | |||

| 1990 - 1994 | .139 | .134 | .213 | |||

| 1995 or later | .015 | .012 | .045 | |||

| Region of Residence | ||||||

| Midwest | .264 | .271 | .159 | |||

| Northeast | .184 | .187 | .138 | |||

| South | .350 | .353 | .303 | |||

| West | .203 | .189 | .401 | |||

| Wife's Age at First Marriage | ||||||

| < 20 years | .241 | .247 | .151 | |||

| 20 - 22 years | .270 | .273 | .232 | |||

| 23 - 26 years | .242 | .241 | .253 | |||

| 27 - 30 years | .126 | .124 | .153 | |||

| > 30 years | .122 | .116 | .211 | |||

| Age Categories | ||||||

| H > 5 years older than W | .185 | .183 | .214 | |||

| H's w/in −2 to 5 years of W | .732 | .741 | .607 | |||

| H > 2 years younger than W | .083 | .076 | .179 | |||

| Education Categories | ||||||

| H more educated than W | .187 | .184 | .236 | |||

| H less educated than W | .174 | .173 | .191 | |||

| Both less than high school | .050 | .051 | .041 | |||

| Both high school | .204 | .207 | .157 | |||

| Both some college | .020 | .018 | .047 | |||

| Both college | .365 | .368 | .328 | |||

| Income at First Spell | 4955.350 | 6136.190 | 4896.100 | 5990.460 | 5807.270 | 7784.820 |

| Number of Preschool-Aged Children | .428 | 0.676 | .425 | 0.674 | .474 | 0.692 |

| Nativity/Citizenship | ||||||

| Both natives | .859 | .877 | .605 | |||

| Both foreign born, at least one is noncitizen | .059 | .060 | .035 | |||

| Both foreign born & citizens | .020 | .021 | .014 | |||

| Noncitizen-native | .030 | .020 | .177 | |||

| Naturalized citizen-native | .032 | .022 | .168 | |||

Note: Means are weighted. Data are from the pooled 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1996, and 2001 Survey of Income and Program Participation panels. Couples in a first marriage at the beginning of the SIPP panel and couples who married during the on-going waves of the panel are included. Marriages involving Native Americans are not included. H = husband, W = wife.

Table 1 also highlights compositional differences between interracial and endogamous marriages. For example, compared with endogamous couples, interracial couples married in more recent time periods were more likely to live in the West and less likely in the Midwest, married on average at older ages (wives), had higher incomes and larger spousal differences in age and education, and were much more likely to involve a combination of foreign-born and native-born spouses. Over one third of interracial couples (34.5%) involved a foreign-born person married to a U.S. native compared with just 4.2% of endogamous couples.

As the focus of our analysis is on marital dissolution, we first examined the observed differentials in marital dissolution without considering the possibly confounding factors associated with both interracial marriage and marital instability during the observation period (results not shown). Consistent with the first homogamy hypothesis, interracial marriages are less stable: 13.7% of interracial couples compared with 9.9% of endogamous couples broke up during their SIPP panel. The descriptive results also confirm the second homogamy hypothesis in which mixed-race couples involving the most socially distant groups (e.g., Blacks and Whites) were most likely to break up: nearly 20% of Black-White couples divorced or separated compared with 13.5% of Hispanic-White couples and 8.4% of Asian-White couples. Furthermore, consistent with the third homogamy hypothesis, both White-Black and Hispanic-White couples were more likely to divorce or separate than endogamous couples from either of the origin groups (10% of White-White, 16% of Black-Black, and 9% among Hispanic endogamous couples). For Asians, however, the results were consistent with the ethnic convergence hypothesis (Hypothesis 4). Roughly 8.3% of Asian-White couples separated or divorced, a level that falls between the relatively high rates for White couples and the relatively low rates among Asian couples (1.4%). The descriptive results thus suggest that interracial couples, especially those involving Blacks and Hispanics, are more likely to divorce or separate than same-race couples. This may be a consequence of potential problems facing interracial couples including stress, social disapproval, and cultural differences. Furthermore, interracial couples differ from endogamous couples in important ways that may elevate the risk of divorce (such as greater age and education differences between spouses). To test this idea, we turn next to the multivariate hazards models.

Multivariate Results

Table 2 presents the results of the Cox Proportional Hazards models of marital dissolution (hazard ratios are displayed). Model 1 includes an indicator of all types of interracial marriages without any controls (Model 1 does not exactly replicate the descriptive results in Table 2 because it conditions the hazard on the duration of marriage). Indeed, interracial marriages are less stable. The risk of marital dissolution among mixed marriages is about 1.21 times that of (or 21% higher than) non-mixed endogamous marriages ( Table 2 , Model 1), and this did not change after adding controls for marriage cohort and region of residence (Model 2). When we added other potential marital dissolution risk factors in Model 3, the hazard ratio associated with mixed marriage declined by 25% to 1.15, and dropped in significance ( p < .01 to p < .10). In general, younger age of first marriage, age and educational differences among the spouses (particularly when the husband is more than two years younger or less educated than the wife); lower levels of education (less than college); lower income; and having no or fewer young children were significantly associated with marital instability. Interracial couples tend to have higher incomes and older ages at marriage (both of which are associated with lower rates of dissolution), so these characteristics cannot explain their higher levels of divorce or separation. Although, mixed marriages are also more likely to involve larger differences in age and education between spouses (consistent with the first homogamy hypothesis), which could partially explain their higher risks of marital dissolution.

Hazard Ratios from Cox Proportional Hazards Models of Marital Dissolution (N = 23,139)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interracial Couple | 1.21 | 1.21 | 1.15 | 1.15 |

| Marriage Cohort | ||||

| (Before 1970) | ||||

| 1970 - 1974 | 1.41 | 1.36 | 1.38 | |

| 1975 - 1979 | 1.37 | 1.24 | 1.25 | |

| 1980 - 1984 | 1.31 | 1.13 | 1.15 | |

| 1985 - 1989 | 1.3 | 1.09 | 1.11 | |

| 1990 - 1994 | 1.2 | .95 | .97 | |

| 1995 or later | 1.07 | .8 | .81 | |

| Region of Residence | ||||

| (Midwest) | ||||

| Northeast | .77 | .82 | .85 | |

| South | 1.18 | 1.14 | 1.15 | |

| West | 1.04 | 1.11 | 1.22 | |

| Wife's Age at First Marriage | ||||

| ( < 20 years) | ||||

| 20 - 22 years | .69 | .70 | ||

| 23 - 26 years | .59 | .60 | ||

| 27 - 30 years | .53 | .54 | ||

| > 30 years | .45 | .46 | ||

| Age Categories | ||||

| (Husband > 5 years older than wife) | ||||

| Husband's age w/in −2 to 5 years of wife | 78 | .77 | ||

| Husband > 2 years younger than wife | 1.30 | 1.28 | ||

| Education Categories | ||||

| (Husband more educated than wife) | ||||

| Both less than high school | 1.02 | 1.22 | ||

| Both high school | 1.1 | 1.09 | ||

| Both some college | .96 | .93 | ||

| Both college | .63 | .62 | ||

| Husband less educated than wife | 1.14 | 1.13 | ||

| Log of Income at 1st Spell | 1 04 | 1.03 | ||

| Number of Preschool-Aged Children | .65 | .66 | ||

| Citizenship | ||||

| (Both natives) | ||||

| Both foreign born, at least one noncitizen | .43 | |||

| Both foreign born & citizens | .48 | |||

| Noncitizen-native | .87 | |||

| Naturalized citizen-native | .94 | |||

| − | 33374.81 | 33321.36 | 32822.32 | 32754.17 |

Note : Omitted categories are shown in parentheses.

We next tested the idea that spousal differences in nativity or citizenship status may explain the higher risk of marital dissolution among mixed-race couples. As shown in Model 4, the risk of divorce was significantly lower for foreign-born couples (both spouses foreign born) than native-born couples, whereas mixed-status couples (foreign-born/native pairings) were not significantly different from couples involving two natives. Unexpectedly, however, the addition of controls for nativity/citizenship status did not alter the hazard ratio associated with interracial marriage.

Thus far, the results support the first homogamy hypothesis, though the support was rather weak. Interracial marriage was positively associated with marital dissolution net of couple characteristics, but this relationship was only marginally significant ( p < .10). To test the remaining hypotheses, it is necessary to examine the risk of marital dissolution separately across racial/ethnic groups. We therefore re-estimated the Cox models shown in Table 2 , this time breaking apart the single indicator of interracial marriage into multiple race combinations (upper panel of Table 3 ). We presented the hazard ratios for race/ethnicity only, although the full models are available to interested readers upon request.

Hazard Ratios from Cox Proportional Hazards Models of Marital Dissolution by Race and Gender of the Couple (N = 23,139)

| Couple Type | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (White-White) | ||||

| Black-Black | 1.69 | 1.63 | 1.59 | 1.63 |

| Black-White | 1.74 | 1.76 | 1.55 | 1.55 |

| Hispanic | .89 | .83 | .75 | .98 |

| Hispanic-White | 1.22 | 1.18 | 1.12 | 1.13 |

| Asian-Asian | .14 | .13 | .16 | .24 |

| Asian-White | .73 | .72 | .75 | .77 |

| Other mixed-race couples | 1.2 | 1.16 | 1.01 | 1.07 |

| (White-White) | ||||

| Black-Black | 1.69 | 1.63 | 1.59 | 1.62 |

| White H-Black W | 1.58 | 1.57 | 1.44 | 1.44 |

| Black H-White W | 1.85 | 1.88 | 1.63 | 1.62 |

| Hispanic-Hispanic | .89 | .83 | .76 | .98 |

| White H-Hispanic W | 1.11 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.06 |

| Hispanic H-White W | 1.33 | 1.28 | 1.18 | 1.19 |

| Asian-Asian | .14 | .13 | .16 | .24 |

| White H-Asian W | .77 | .74 | .74 | .77 |

| Asian H-White W | .67 | .67 | .77 | .79 |

| Other mixed-race | 1.2 | 1.16 | 1.01 | 1.07 |

Note : Controls were added to the models as in Table 2 . Omitted categories are shown in parentheses. H = husband, W = wife.

b p < .10.

When we examine the instability of interracial marriages by race/ethnicity in Table 3 , the results generally reveal patterns that are more consistent with the ethnic convergence than the homogamy hypothesis. Nevertheless, the results were consistent with the second homogamy hypothesis in that the risk of marital dissolution was highest among Black-White couples, followed by Hispanic-White, minority-minority couples, and finally, Asian-White couples. This ordering was retained across all models, although only Black-White couples had significantly greater hazard of dissolution than White endogamous couples when all controls were included in the model (Model 4, Table 3 ).

Overall, neither the descriptive nor the multivariate results provides strong support for the third homogamy hypothesis that interracial couples would be less stable than endogamous marriages from each of the origin groups. Across all four models in Table 3 , the hazard of dissolution for Black-White couples was significantly higher than White-White couples but not significantly higher than Black-Black couples. Among couples involving Hispanics, the risk of marital dissolution for Hispanic-White couples was 22% greater as compared to White-White couples. Though, when we controlled for couple characteristics in Model 3, the difference between Hispanic-White and White-White couples became insignificant. Also, after controlling for nativity and citizenship in Model 4, the difference between Hispanic-White and Hispanic-Hispanic couples also became insignificant. Thus, only Black-White couples were more likely to break up than otherwise similar White-White couples, but their risk of dissolution was no different from that of Black-Black couples.

Finally, the results provided some weak support for the ethnic convergence hypotheses. Among Asians, the hazard of divorce or separation for interracial couples fell between that of Asian and White endogamous couples but the difference from White couples was not significant, thus failing to fully support Hypothesis 4. We had also hypothesized that nativity and citizenship between spouses of Hispanic and Asian interracial couples may help explain their higher risks of marital dissolution (Hypothesis 5). This idea was not fully supported because interracial marriages involving Hispanics or Asians did not experience elevated hazards of dissolution (so there were no significant differences to explain). Nevertheless, nativity and citizenship did help explain the relatively low risks of instability among Hispanic and Asian endogamous couples. When we added controls for nativity and citizenship in Model 4, the hazards for Hispanic and Asian endogamous couples increased, thereby narrowing the difference from both White couples and interracial couples. In fact, the difference between Hispanic-White and Hispanic-Hispanic couples became insignificant after controlling for citizenship and nativity in Model 4.

As a final step, we investigated whether the findings varied by gender combination of interracial couples. We repeated the models by distinguishing among various race/ethnicity and gender combinations as shown in the lower panel of Table 3 (hazard ratios only). Overall, interracial marriages involving a minority husband and White wife were less stable than other types of interracial marriages. Among them, Black husband-White wife and Hispanic husband-White wife couples were particularly likely to break up (Model 1). Nevertheless, the results were consistent with the earlier findings showing little to weak support for the third homogamy hypothesis. After all controls were added, Black husband-White wife couples showed higher risks of dissolution than White couples but similar (and not higher) risks as Black couples. Among Hispanic-White couples, Hispanic husband-White wife were no more likely to dissolve than White or Hispanic endogamous couples.

Marital dissolution of interracial marriage serves as an important indicator of the salience and persistence of racial and ethnic boundaries in the United States. Yet, the majority of the current studies on interracial marriage have focused on the prevalence of such unions instead of their dissolution, while those that have assessed the instability of interracial marriages tend to be dated and have focused solely on Black-White marriages or on interracial marriage in a particular region. The contribution of this study is that it examines the instability of interracial marriage among Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians in contemporary American society, an era marked by increasing diversity and increasing prevalence of interracial marriage. Overall, although marital dissolution was found to be strongly associated with race/ethnicity, the results failed to provide evidence that interracial marriage per se is associated with an elevated risk of marital dissolution. Some have argued that the increasing prevalence of interracial marriage may be associated with the reduction of social distance across groups. The findings described here showing little difference between interracial and endogamous marriages in the risk of divorce or separation lends further credence to this (albeit cautiously) optimistic point of view.

Our first hypothesis (consistent with the “homogamy” perspective) predicts that when couples are dissimilar in racial/ethnic background, their risk of divorce/separation is higher. Our results do show that, on the whole, interracial marriages are less stable than endogamous marriages, even after controlling for couple characteristics. Nonetheless, the analysis compared all interracial marriages with all endogamous marriages and did not take into account group variations in the tendency to divorce or separate. When we divided the results by race/ethnicity, the results were only partially consistent with the homogamy perspective. As we expected, racial/ethnic differences appeared in the risk of divorce or separation. Mixed marriages involving Blacks were the least stable followed by Hispanics, whereas mixed marriages involving Asians were even more stable than endogamous White marriages. In addition, Black husband-White wife pairings were found to be the least stable of all marriage types. One plausible interpretation of these results is that they reflect persistent racism and distrust directed toward Blacks, particularly Black men in the United States. The qualitative findings from Yancey (2007) indicated that Whites who married Blacks experienced more first-hand racism as compared to Whites who married other non-Black minorities. Specifically, White women reported encountering more racial incidents with their Black husbands (e.g. inferior service, racial profiling, and racism against their children) and more hostilities from families and cohorts as compared to other interracial pairings ( Yancey 2007 ). Research in communication and cultural studies echoed Yancey's findings and found that the above-mentioned social pressures tend to increase social isolation of Black-White unions, especially from the White community, and consequently negatively impact the survival of these marriages ( Hibbler & Shinew, 2002 ; Porterfield, 1982 ).

As suggested by the results that compare interracial couples with endogamous couples within racial/ethnic groups , the racial/ethnic patterns in the risk of dissolution appear to reflect broad race/ethnic differences, which may in turn be associated with a number of factors including discrimination, but are not specifically associated with interracial marriage itself. Specifically, in the descriptive results, Black-White and Hispanic-White marriages appeared to be less stable as compared to Black or Hispanic endogamous marriages respectively (consistent with Hypothesis 3). These patterns, however, failed to appear in any of the multivariate models for Blacks, and in the case of Hispanics were attenuated and did not reach statistical significance once couple-level characteristics were controlled. Thus, the third homogamy hypothesis was not supported. Rather, the most consistent result was that the risks of divorce for interracial couples for all combinations (Black-White, Hispanic-White, and Asian-White) were not significantly different from those of the higher-risk origin group. Kalmijn et al. (2005) found a similar pattern in the Netherlands in which the risk of divorce for mixed marriages seemed to be driven more by the divorce-prone group of the couple, a pattern they refer to as consistent with “a weak form of a heterogamy effect” (p. 83). More consistent with the ethnic convergence than the homogamy perspective, this idea makes some sense assuming that it takes both partners to make a marriage work. Furthermore, the results concerning Asians and, to some degree Hispanics, offer some additional support for the ethnic convergence perspective. The risk of divorce for Asian-White couples fell between that of Asian and White couples (significant in the descriptive results but not in the multivariate models), and the differences between Asian and Asian-White couples and between Hispanic and Hispanic-White couples narrowed once citizenship and nativity were added to the model.

The research presented here has several limitations. Although the SIPP data offer important advantages over alternative data, it provides only a snapshot of marriages for a 3- to 4-year time period. Even after pooling six SIPP panels together, the number of interracial couples was small, which may have contributed to the insignificant findings. In addition, because of limitations of the SIPP, we were unable to control for some potentially important measures (such as cohabitation history) and macrolevel forces (institutionalized discrimination and racism). Future research on the stability of interracial marriage would benefit from data that permits larger numbers of interracial couples to be followed over a longer period of time. Because many Hispanic and Asian families are still relatively new to the United States, the generational effect may be more apparent in the long run. Also, qualitative data and mixed methodology could help shed light on the complexity of this issue that quantitative data usually cannot easily answer. Finally, better theoretical frameworks need to be developed to guide the explanation of interracial marital stability. An example concerns the relationship between race and gender combinations and marital stability. In our study, the effects of certain racial/ethnic combinations were similar for both men and women once controls were introduced into the models (e.g., among Asians and Hispanics). Still, Black husband-White wife marriages tended to be less stable than White husband-Black wife marriages. This may reflect differences in the social acceptability of certain combinations, but the precise reasons remain unclear. As interracial marriages and multiracial children become more commonplace, expanding research on the stability of interracial marriage becomes vital, not only for the children born into those marriages, but also because the success and stability of such marriages provides insight into the enduring or waning social rigidity of racial boundaries in the United States.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. Zhenchao Qian for providing many helpful suggestions and comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Contributor Information

Yuanting Zhang, National Institute of Health moc.eticxe@tnauygnahz .

Jennifer Van Hook, Pennsylvania State University ude.usp.pop@koohnavj .

- Alba RD, Golden RM. Patterns of ethnic marriage in the United States. Social Forces. 1986; 65 :202–223. [ Google Scholar ]

- Allison PD. Survival analysis using the SAS system: A practical guide. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bahr HM. Religious intermarriage and divorce in Utah and the Mountain States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1981; 20 :251–261. [ Google Scholar ]

- Billingsley A. Black families in White America. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1968. [ Google Scholar ]

- Box-Steffensmeier JM, Jones BS. Event history modeling: A guide for social scientists. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter H, Glick P. Marriage and divorce: A social and economic study. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1970. [ Google Scholar ]

- Castro Martin T, Bumpass L. Recent trends in marital disruption. Demography. 1989; 26 :37–51. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cherlin A. The effect of children on marital dissolution. Demography. 1977; 14 :265–272. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frisbie WP, Bean FD, Eberstein IW. Recent changes in marital instability among Mexican Americans: Convergence with Black and Anglo trends? Social Forces. 1980; 58 :1205–1220. [ Google Scholar ]

- Frisbie WP, Opitz W, Kelly WR. Marital instability trends among Mexican Americans as compared to Blacks and Anglos: New evidence. Social Science Quarterly. 1985; 66 :587–601. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fu X. Impact of socioeconomic status on inter-racial mate selection and divorce. The Social Science Journal. 2006; 43 :239–258. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gordon MM. Assimilation in American life: The role of race, religion, and national origins. Oxford University Press; New York: 1964. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hibbler DK, Shinew KJ. Interracial couples experience of leisure: A social construction of a racialized other. Journal of Leisure Research. 2002; 34 :135–156. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jones FL. Are marriages that cross ethnic boundaries more likely to end in divorce? Journal of the Australian Population Association. 1994; 11 :115–132. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jones FL. Convergence and divergence in ethnic divorce patterns: A research note. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996; 58 :213–218. [ Google Scholar ]

- Joyner K, Kao G. Interracial relationships and the transition to adulthood. American Sociological Review. 2005; 70 :563–581. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kalmijn M. Shifting boundaries: Trends in religious and educational homogamy. American Sociological Review. 1991; 56 :786–800. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kalmijn M. Intermarriage and homogamy: Causes, patterns, and trends. Annual Review of Sociology. 1998; 24 :395–421. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kalmijn M, de Graaf P, Janssen J. Intermarriage and the risk of divorce in the Netherlands: The effects of differences in religion and in nationality, 1974 - 94. Population Studies. 2005; 59 :71–85. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Landale NS, Ogena NB. Migration and union dissolution among Puerto Rican women. International Migration Review. 1995; 29 :671–692. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee J, Bean FD. Reinventing the color line immigration and America's new racial/ethnic divide. Social Forces. 2007; 86 :561–586. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee SM, Edmonston B. New marriages, new families: U.S. racial and Hispanic intermarriage. Population Bulletin. 2005; 60 (2):1–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Monahan TP. Are interracial marriages less stable? Social Forces. 1970; 48 :461–473. [ Google Scholar ]

- Neyrand G, M'Sili M. Mixed couples in contemporary France: Marriage, acquisition of French nationality and divorce. Population. English selection. 1998; 10 :385–416. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oropesa RS, Landale NS. The future of marriage and Hispanics. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004; 66 :901–920. [ Google Scholar ]

- Phillips JA, Sweeney MM. Can differential exposure to risk factors explain recent racial and ethnic variation in marital disruption? Social Science Research. 2006; 35 :409–434. [ Google Scholar ]

- Porterfield E. Black-American intermarriage in the United States. Marriage and Family Review. 1982; 5 :17–34. [ Google Scholar ]

- Qian Z. Breaking the racial barriers: Variations in interracial marriage between 1980 and 1990. Demography. 1997; 34 :263–276. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Qian Z, Lichter DT. Social boundaries and marital assimilation: Interpreting trends in racial and ethnic intermarriage. American Sociological Review. 2007; 72 :68–94. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rankin RP, Maneker JS. Correlates of marital duration and Black-White intermarriage in California. Journal of Divorce. 1987; 11 :33–49. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ruggles S. The rise of divorce and separation in the United States, 1880 - 1990. Demography. 1997; 34 :455–466. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sollors W. Interracialism: Black-White intermarriage in American history, literature, and law. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- South S. Do you need to shop around? Age at marriage, spousal alternatives and marital dissolution. Journal of Family Issues. 1995; 16 :432–449. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stevens G. Propinquity and educational homogamy. Sociological Forum. 1991; 6 :715–726. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stevens G, Swicegood G. The linguistic context of ethnic endogamy. American Sociological Review. 1987; 52 :73–82. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sweeney MM, Phillips JA. Understanding racial differences in marital disruption: Recent trends and explanations. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004; 66 :639–650. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sweezy K, Tiefenthaler J. Do state-level variables affect divorce rates? Review of Social Economy. 1996; 54 :46–65. [ Google Scholar ]

- Trent K, South SJ. Structural determinants of the divorce rate: A cross-societal analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989; 51 :391–404. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tucker MB, Mitchell-Kernan C. New trends in black american interracial marriage: The social structural context. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990; 52 :209–218. [ Google Scholar ]

- United States Census Bureau [Dec. 15, 2005]; Overview of the Survey of Income and Program Participation. from http://www.sipp.census.gov/sipp/overview.html .

- Yancey G. Experiencing racism: Differences in the experiences of Whites married to Blacks and non-Black racial minorities. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 2007; 38 :197–213. [ Google Scholar ]

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Research on Cross-Race Relationships: An Annotated Bibliography

Prevalence of cross-race relationships in the United States

Chatman, J.A., Polzer, J.T., Barsade, S.G., & Neale, M.A. (1998). Being different yet feeling similar: The influence of demographic composition and organizational culture on work processes and outcomes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43, 749 – 780. The authors examined how demographic diversity and corporate culture interact to influence interaction among members, the salience of social categories, and group creativity, productivity, and conflict in simulated organizations. Corporate culture was manipulated to be either individualistic (rewarding individual rather than team achievement) or collectivistic (rewarding team rather than individual achievement, emphasizing organizational membership), and demographic diversity was based on participants' age, sex, and race. Simulated organizations that were demographically diverse and emphasized organizational membership had more interaction between members and reported other member's demographic characteristics to be less salient than diverse and individualistically oriented organizations. Back to Questions Individual Characteristics

Despite negative social attitudes towards interracial relationships, there are many benefits to cross-race friendships and relationships. These benefits span from decreased prejudice to higher educational aspirations and leadership skills. Overall, studies involving both children and adults overwhelmingly support contentions that cross-race friendships increase positive intergroup relations in the U.S. There has been much replication of studies showing better cross-race attitudes among individuals with high proportions of interracial friendships. For children, the positive effects appear to span beyond intergroup attitudes to social and achievement domains. In addition, there is evidence that individual’s intergroup attitudes could benefit from cross-race friendships merely by observing positive intergroup friendships among their fellow in-group members. Back to Questions

About the Author

Elizabeth page-gould.

Elizabeth Page-Gould, Ph.D., is an associate professor of psychology and the Canada Research Chair of Social Psychophysiology at the University of Toronto.

You May Also Enjoy

Learning about Race

The Perils of Colorblindness

University diversity.

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University website

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Interracial Marriage in "Post-Racial" America

- Jessica Viñas-Nelson

A protestor’s sign from a 2013 marriage equality rally using an image of Richard and Mildred Loving, the couple behind the court case that brought down interracial marriage prohibitions.

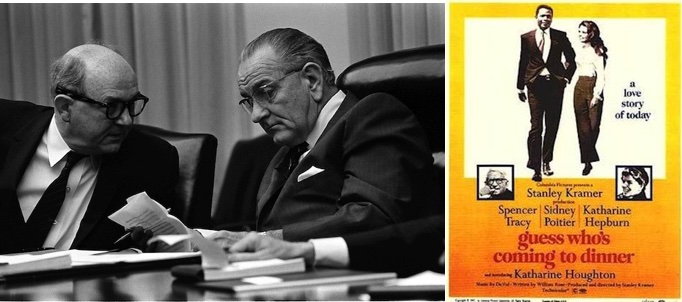

June 12th marks the anniversary of the Supreme Court's Loving v. Virginia case that struck down laws prohibiting interracial marriage. More than fifty years later, it seems absurd to most of us that such laws ever existed in the first place. But, as historian Jessica Viñas-Nelson explains, the fear of interracial marriage has been at the center of America's racial anxiety for a very long time.

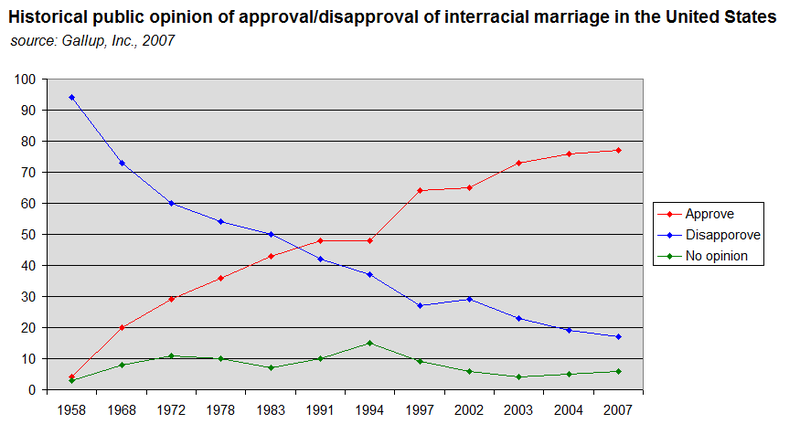

In June, many Americans marked Loving Day—an annual gathering to fight racial prejudice through a celebration of multiracial community. The event takes its name from the 1967 Supreme Court ruling in Loving v. Virginia. The case established marriage as a fundamental right for interracial couples, but 72 percent of the public opposed the court’s decision at the time. Many decried it as judicial overreach and resisted its implementation for decades.

The case that brought down interracial marriage bans in 16 states centered on the aptly named Richard and Mildred Loving. In 1958, the pair were arrested in the middle of the night in their Virginia home after marrying the month before in Washington, D.C. Pleading guilty to “cohabiting as man and wife, against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth,” they were offered one year imprisonment or a suspended sentence if they left their native state.

A 2013 Loving Day celebration in New York City (photo by Willie Davis).

The Lovings chose exile over prison and moved to D.C. but they missed their hometown. After being arrested again in 1963 while visiting relatives in Virginia, Mildred Loving wrote Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who in turn referred her to the American Civil Liberties Union. The ACLU appealed the Lovings’ conviction, arguing interracial marriage bans contradicted the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. Despite this line of argument, lower courts upheld the verdict because, as one jurist wrote, “the fact that [Almighty God] separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.”

After multiple appeals, the case reached the Supreme Court, where Chief Justice Earl Warren’s opinion for the unanimous court declared marriage to be “one of the ‘basic civil rights of man’…To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications…is surely to deprive all the State’s citizens of liberty.” Warren further ruled that interracial marriage bans were designed expressly “to maintain White Supremacy.” The court’s decision not only struck down an 80-year precedent set in the case Pace v. Alabama (1883), but 300 years of legal code.

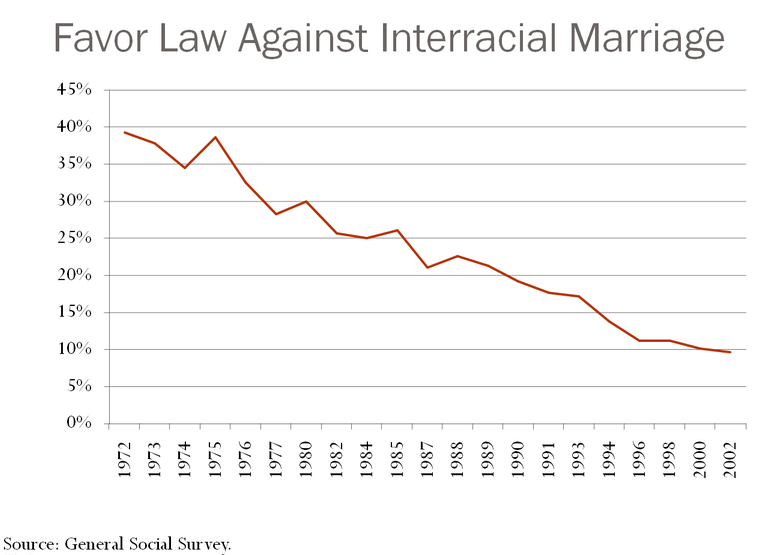

A chart depicting American approval and disapproval of interracial marriage from 1958 to 2007.

In the decades that followed, the nation’s views on interracial marriage have undergone a slow sea change. In 1967, only 3 percent of newlyweds were interracial couples. Today, 17 percent of newlyweds and 10 percent of all married couples differ from one another in race or ethnicity. Even though legal in most states by 1959, the overwhelming majority of white Americans then believed rejecting interracial marriage to be fundamental to the nation’s well-being. In 2017, in contrast, 91 percent of Americans believe interracial marriage to be a good or at least benign thing.

Today, few would publicly admit to opposing interracial marriage. In fact, most Americans now claim to celebrate the precepts behind Loving and the case has become an icon of equality and of prejudice transcended. Accordingly, individuals across the political spectrum, from gay rights activists to opponents of Affirmative Action who call for colorblindness, cite it to support their political agendas.

Yet, for 300 years, interracial marriage bans defined racial boundaries and served as justification for America’s apartheid system. And 50 years on, many of their effects remain.

Founding Myth, Foundational Rejection

The first recorded interracial marriage in American history was the celebrated marriage of the daughter of a Powhatan chief and an English tobacco planter in 1614. Matoaka, better known as Pocahontas, did not wed Captain John Smith as the Disney version of her life implies. Instead, she married John Rolfe as a condition of release after being held captive by English settlers for more than a year.

Rolfe presented her, duly baptized, in England as a symbol of peace, an example of England’s “civilizing” potential in the New World, and a means to raise funds for the Virginia Company’s colony. She died in England soon thereafter and the peace brokered with the marriage collapsed.

John Gadsby Chapman’s 1840 painting depicts Pocahontas’s baptism and rechristening as Rebecca before her 1614 marriage.

This first marriage obtained mythic portions long before Disney remade the story and even shaped Virginia’s laws on interracial marriage. Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924 codified individuals as white only if they had “no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian,” except for those who had one-sixteenth or less blood from American Indians—the so-called “Pocahontas exception”—a concession to some elite families who claimed lineage from Rolfe and Pocahontas’s only child.

While Rolfe—and his alleged future descendants—won esteem for association with an “Indian princess,” relatively little racial mixing occurred between English settlers and Native Americans. English prejudice against a “savage” people, religious injunctions against marrying non-Christians, and a smaller imbalance in gender ratios among English colonists than in French and Spanish colonies contributed to this outcome—not to mention Indian women’s disinclination to select Englishmen, who were much less adept than Native men at hunting, fishing, and other valued skills.

The first laws proscribing interracial relationships, however, did not pertain to Native-English unions but to ones colonial leaders feared would upend the social order because they could promote alliances between indentured servants and slaves.

In 1664, Maryland sought to stanch potential interracial marriages by threatening enslavement for white women who married black men. Two years earlier, Virginia had enacted legislation to profit from white men’s sexual relationships with black women. Children would inherit the social status of their mother, not their father, meaning the children of slave women would be born slaves regardless of the father’s status. Virginia then outlawed interracial marriage entirely in 1691. Virginia’s original penalty for those who wed interracially—banishment—was the same punishment the Lovings received nearly three centuries later.

These laws had clear aims: to control women’s sexuality, to establish categories of slave and free, and to develop racist ideologies justifying discrimination. White men had sexual access to all women and exclusive access to white women. Interracial sex, so long as it remained out-of-wedlock and occurred between white men and black women, merited little legal or social consequence. These laws also set into motion America’s peculiar system of racial classification: hypodescent. Americans would be classified not according to the degree of mixture they contained but by the total absence or presence of blackness.

An 1804 political cartoon referencing the widely rumored relationship between President Thomas Jefferson and his slave, Sally Hemings. DNA evidence has demonstrated the rumor’s veracity.

The first laws prohibiting interracial marriages occurred when wealthy planters were transitioning from using European indentured servants as their primary labor to African slaves. As these two labor pools worked alongside one another and even married one another, planters feared that poor whites and African slaves would overthrow the far smaller planter class.

Interracial marriage bans, therefore, arose to build racial barriers that would supplant alliances among the laborers by creating binary categories of black and white, slave and free. Indeed, Maryland’s assembly passed the statute discouraging marriage between white women and black men within an act authorizing lifelong slavery.

Most other American colonies followed Maryland and Virginia’s lead and banned interracial marriage between 1661 and 1725. Forty-one states in all eventually enacted bans.

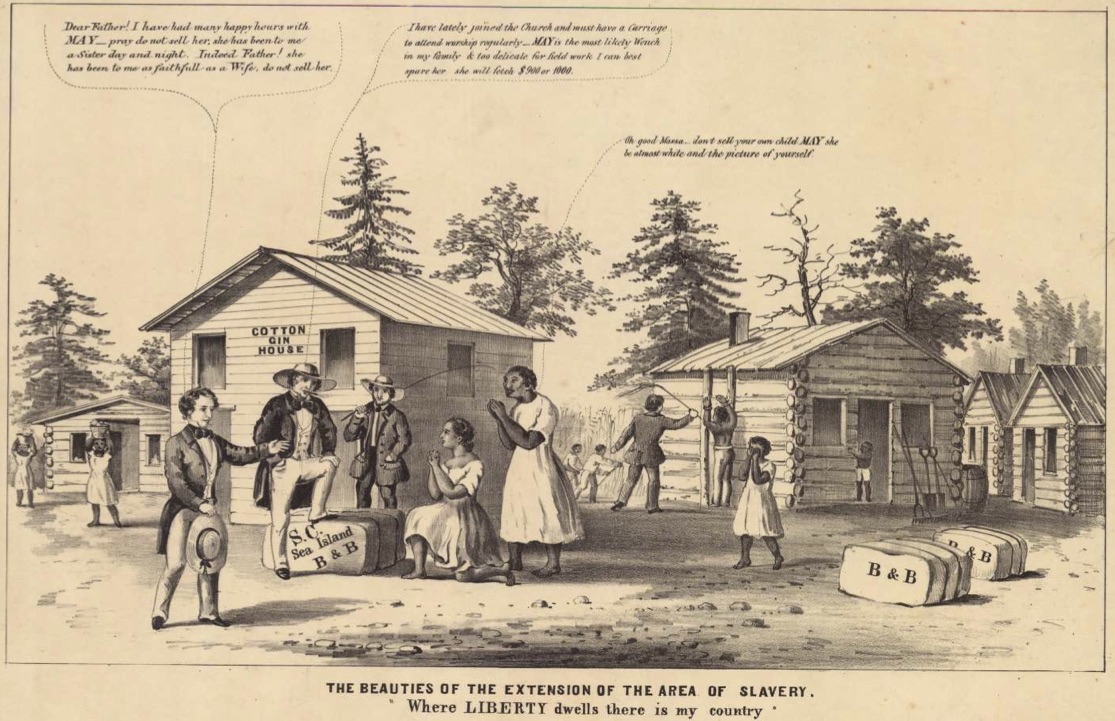

This abolitionist drawing from the 1850s suggests the plight of the enslaved children of white masters, depicting a nearly-white slave and her mother pleading not to be sold.

“The Battering Ram”: Interracial Marriage and the Age of Abolition

Northern colonies and later states also enacted bans on interracial marriage, although some repealed these as they gradually abolished slavery. Nevertheless, white fears of mixed marriages remained a potent political force, particularly in the North.

Most white northerners showed themselves firmly opposed to any suggestion of black equality through their rejection of interracial marriage or even the mere hint of its occurrence. Not coincidently, public hysteria against interracial marriage grew louder in the 1830s when the rights of black people were being contentiously debated and a more vocal and inclusive abolitionist movement emerged. Defenders of slavery accused abolitionists of coveting interracial marriages, despite the undeniable evidence of interracial offspring on Southern plantations resulting from slave owners forcing themselves on slave women.

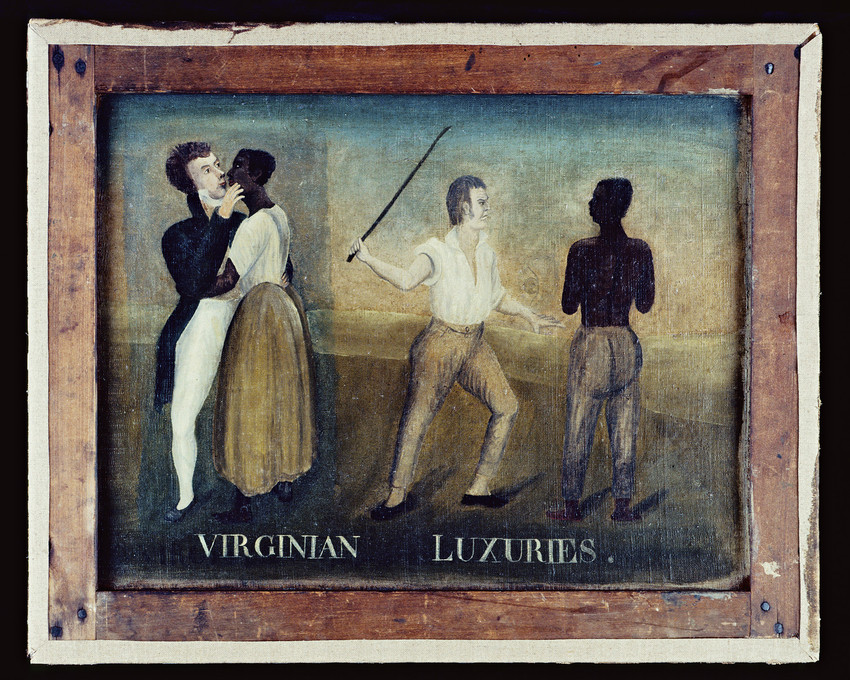

A double-sided painting from New England c1825, Virginia Luxuries features a bust-length portrait on one side and the above image on the reverse. The double-side nature of the painting serves two purposes: as a commentary that behind the respectable exterior of white Virginia gentlemen lies perverse desires and as a means for the owner of the painting to hide its controversial side from unreceptive viewers.

After rumors spread in 1834 that abolitionist ministers had married an interracial couple (they hadn’t), 11 days of racial terror erupted in New York City. A mob attacked a mixed-race gathering of the American Anti-Slavery Society and continued to menace, burn, and destroy the homes and churches of leading abolitionists. The mob’s wrath targeted black churches, homes, schools, and businesses. A similar riot, with similar instigation and targets of violence, occurred in Philadelphia in 1838.

As the targeted violence against abolitionists and black institutions illustrates, by the 1830s, interracial marriage had become a proxy for white anxieties that the social order they had built upon racial distinction might be endangered. Abolition threatened the social order and thus supporters of slavery raised fears of interracial marriage to torpedo abolitionists’ efforts and to hurt the free black population.

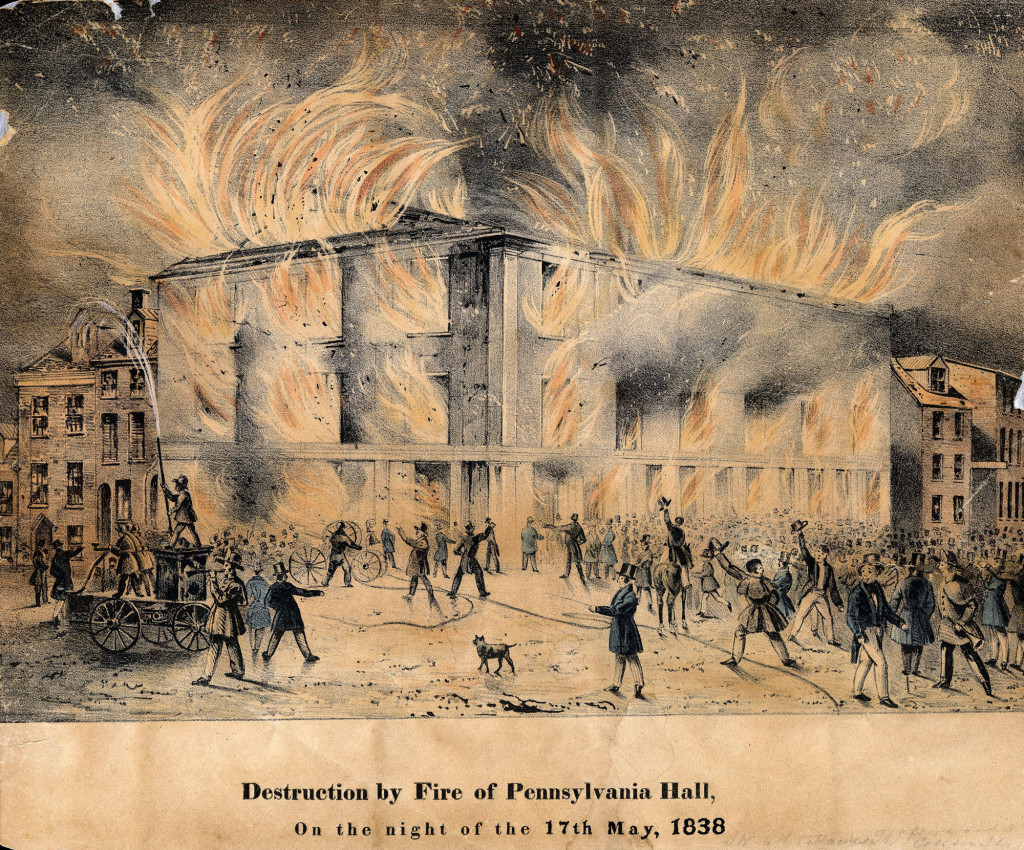

Just days after its grand opening in 1838, a mob burned Pennsylvania Hall—a building constructed as a forum to discuss abolition and other social movements—after rumors spread that an interracial marriage had been performed there.

Many of the 165 anti-abolitionist riots that took place in the 1830s were provoked by rumors of interracial marriages. Little else could more effectively raise a mob or garner as much wrath; anti-abolitionists used this to great effect. In 1838, the black-authored newspaper Colored American astutely labeled the tactic “the battering ram of the pro-slavery party.”

Despite allegations that abolitionists were amalgamationists (supporters of interracial marriage), most in fact opposed interracial marriage and readily crumbled before the oft-repeated question: “Would you let your daughter marry a Negro?”

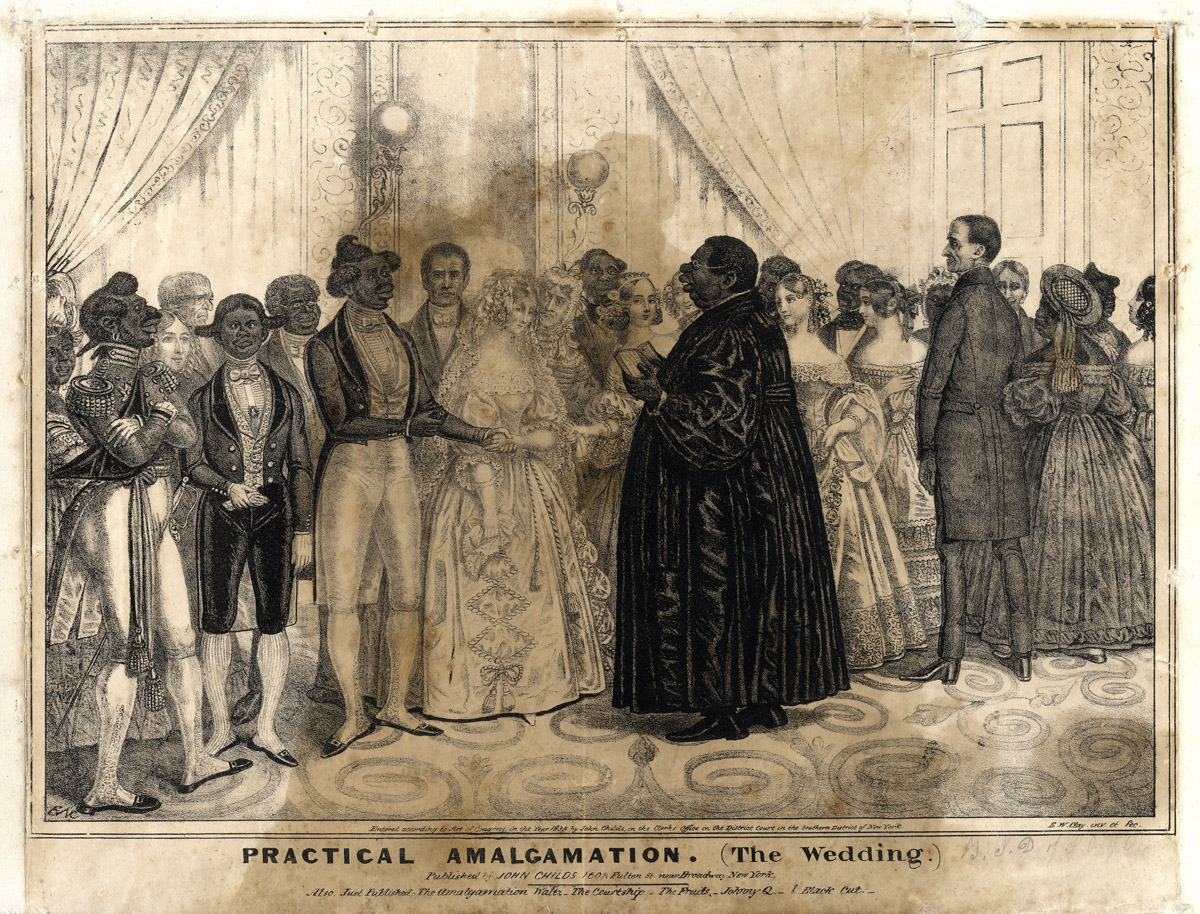

Part of E.W. Clay’s 1839 series of lithographs on the topic, “Practical Amalgamation (The Wedding)” caricatures people of African descent as buffoonish but depicts whites as having delicate and refined features. The black clergyman at center was meant to show a reversal of the racial hierarchy and the man on the far right’s resemblance to William Lloyd Garrison suggests a connection between abolitionists and amalgamation. Clay’s series as a whole encouraged the belief that blacks were physically and socially inferior to whites, yet sought interracial marriages to improve their standing.

Even William Lloyd Garrison, one of the most radical abolitionists, never advocated actual interracial marriages even as he fought for the repeal of marriage bans. Garrison explained that abolitionists’ support for repealing interracial marriage bans “has not been to promote ‘amalgamation,’ but to establish justice.”

Such marriages among abolitionists were also exceedingly rare. One of the few known interracial marriages between abolitionists—William King and Marry Allen (1853)—resulted in their fleeing the country in fear for their lives.

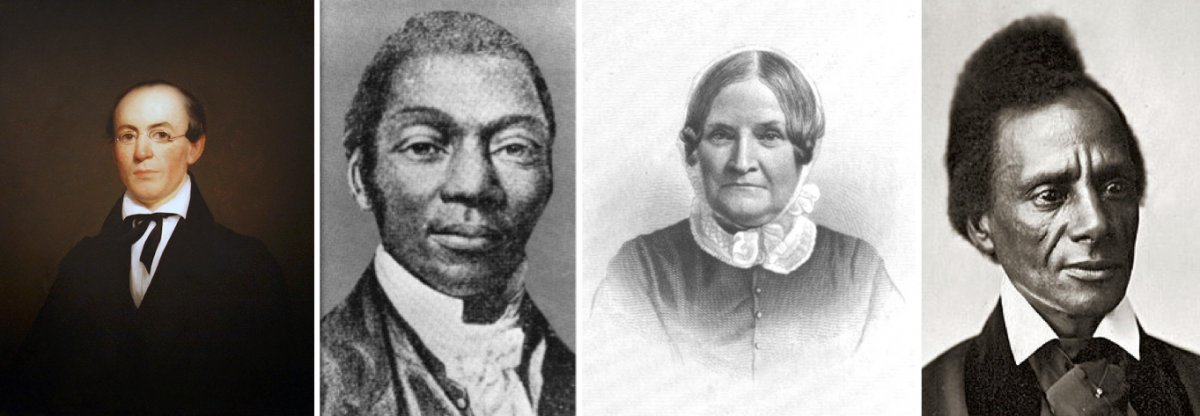

Abolitionist and publisher William Lloyd Garrison spoke out about the injustice of interracial marriage bans ( left ). Abolitionist and writer David Walker called for black unity against racial injustice in 1829 ( second from left ). Abolitionist, writer, and women’s rights advocate Lydia Maria Child argued for the right to interracial marriage in principle, not in practice as she maintained “no abolitionist considers such a thing desirable” ( third from left ). Orator and abolitionist Charles Lenox Remond considered the legality of interracial marriage the epitome of rights necessary for a free and open society and fought for the repeal of Massachusetts’s ban in 1843 ( right ).

Most African Americans too were ambivalent toward marrying interracially. They saw the importance of obtaining the legal right to it in principle, but took pains to deny allegations that they coveted such unions and vehemently decried slave owners’ rape of enslaved women. Perhaps the era’s most famous black pronouncement on the matter came from David Walker’s revolutionary Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World (1829) when he declared: “I would not give a pinch of snuff to be married to any white person I ever saw.” Nevertheless, he argued that marriage bans were a hallmark of inequality and he sought their removal on principle.

Even where interracial relationships were legal, derogatory depictions—like E.W. Clay’s popular series of lithographs—linked it in the white public’s imagination with bastardy, debauchery, and immorality. In rare cases though, interracial couples inside and outside of legal wedlock existed and sometimes even thrived in pockets of the North where local communities paid far less concern than one might expect. Even if community tolerance existed, however, the children of interracial couples unable to legally wed were defined as bastards—a branding that carried real consequences in the 18 th and 19 th centuries as it foreclosed the possibility of inheritance—meaning white property remained in white hands.

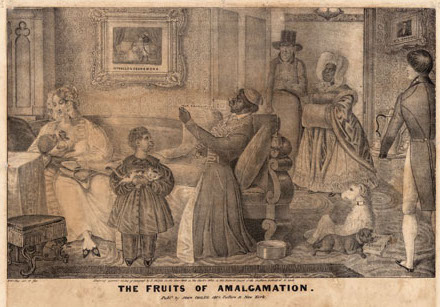

The final image of E.W. Clay’s 1839 series of lithographs on the topic, “Practical Amalgamation (The Fruits of Amalgamation)” implies a direct line between interracial interaction and the upending of social norms and racial hierarchies.

For the enslaved population, however, no such consensual interracial relationship could exist. Even the rare and seemingly loving unions that functioned like marriages between masters and slaves could not—by definition—be consensual. Most interracial sex under slavery, however, did not even have a veneer of loving attachments and was instead the blatant rape of black women by white men. This history’s effect on African Americans’ views of interracial relationships cannot be overstated.

Nor can interracial marriage’s role in politics and legal history be exaggerated.

As part of the justification for the infamous Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) case, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney used the existence of interracial marriage bans as evidence that the Founding Fathers never intended Black Americans to be citizens. These laws, Taney insisted, were evidence of a “perpetual and impassable barrier erected between the white race and [those]…which they looked upon as so far below them in the scale of created beings that intermarriages between white persons and negroes and mulattoes were regarded as unnatural and immoral, and punished as crimes.”

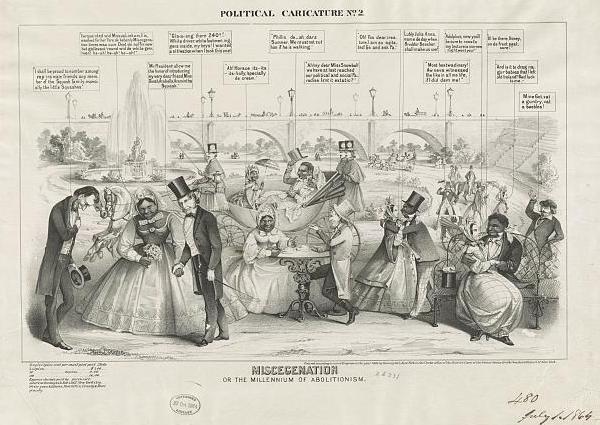

An 1864 political cartoon depicting a ludicrous version of the results of racial equality as allegedly proposed by the Republican Party.

The issue even arose in the legendary debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas. Douglas accused Lincoln of condoning amalgamation, to which Lincoln vehemently protested “that counterfeit logic which concludes that, because I do not want a black woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife.” Accusations, however, continued to plague Lincoln and took on a life of their own in the 1864 election.

Miscegenation and “Purity”

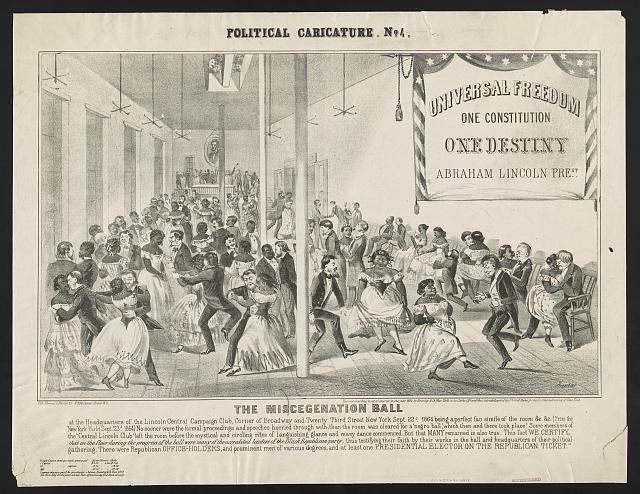

Resurrecting the false connections between abolitionism and amalgamation, Lincoln’s opponents invented a new term in the midst of the Civil War to describe interracial relationships: “miscegenation” (the blending of races). Aiming to cost Lincoln and his party the 1864 election, two Democrats (posing as Republicans) promoted the notion that the Republican Party not only condoned interracial marriages, but actively encouraged them.

An 1864 anti-Republican satire using white northerners’ fears of racial mixing.

The new term did not cost Lincoln reelection, but its overnight and enduring popularity highlights the public’s desire to describe something that had long been around, but suddenly seemed in need of a new moniker in order to associate it with heightened fear of black freedom. Miscegenation permanently rooted itself into America’s racial lexicon and the fear of it became a political wedge issue for at least a century thereafter.

Fears of miscegenation, interracial marriage, or “social equality” arose in nearly every debate over political, economic, and social rights. The topic would even make an appearance in the rationale for the Supreme Court decision that allowed the system of Jim Crow discrimination and supposed “separate but equal” to continue: the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) ruling. “Laws forbidding the intermarriage of the two races,” the court reasoned, “may be said in a technical sense to interfere with the freedom of contract, and yet have been universally recognized as within the police power of the State.” The foundation of post-Civil War white supremacy rested firmly upon opposition to miscegenation.

A rally against integrating Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1959. Protestors connected school desegregation to race mixing and race mixing to both communism and “the Anti-Christ.”

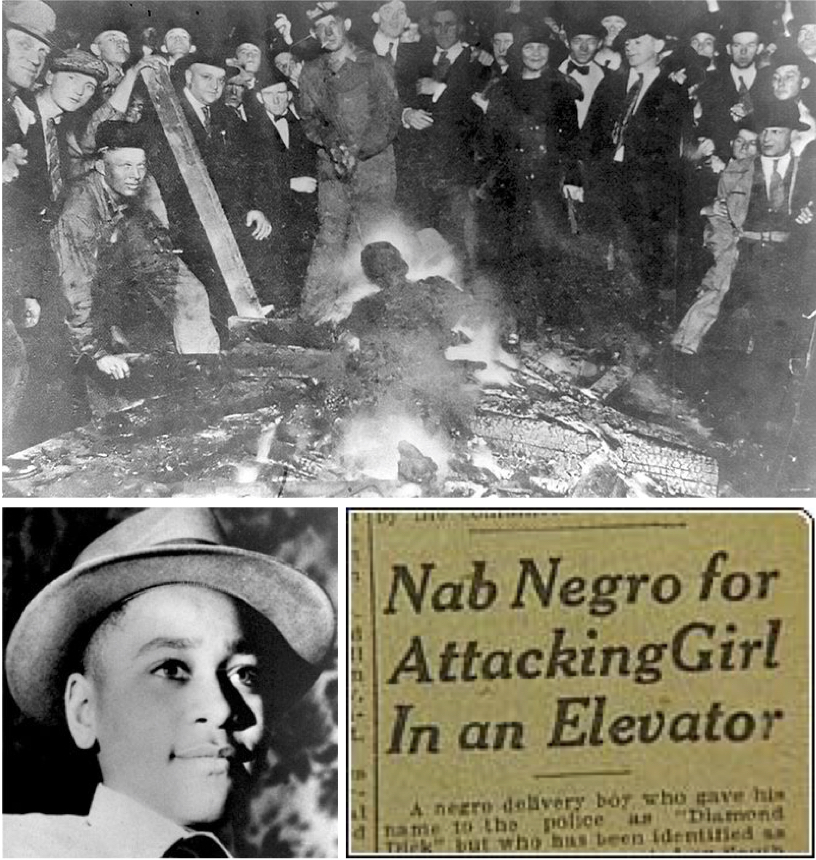

The far more chilling effect of irrational white fears over miscegenation, however, emerged outside of the court system: lynching.

Between 1882 and 1968, at least 3,446 black men were publicly and ritualistically murdered by white mobs. Roughly a third were accused of raping white women, but the alleged need to protect white women from black men—universally portrayed as violent, lustful, and savage—justified lynch mobs’ actions to the larger white public. Black journalist Ida B. Wells demonstrated that many of these accusations of rape stemmed from consensual interracial relationships that had been discovered by white women’s disapproving relatives. Nevertheless, the lynching continued, as did white fears about racial “purity.”

A close examination of almost any act of racial violence against African Americans reveals the specter of rape accusations. A mob hung, shot, and burned William Brown in Omaha, Nebraska in 1919 after he was accused of raping a white woman ( top ). Fourteen-year-old Emmett Till was brutally murdered in 1955 after supposedly whistling at a white woman ( left) . A 1921 newspaper article encouraging violence after a black teen allegedly assaulted a white teen in Tulsa, Oklahoma ( right ). The resulting riot leveled 35 blocks of the city’s black section and killed an estimated 39 to 300 African Americans.

The concept of racial “purity” evolved through interracial marriage law. In post-Civil War Arkansas, a black delegate to the state’s constitutional convention— William H. Grey —mocked a white delegate's insistence that interracial marriage be banned by questioning how such a feat could even be accomplished given that "the purity of the blood, of which the gentleman speaks, has already been somewhat interfered with."

Legislation would become a “farce,” Grey insisted, as scientific boards proved unable to draw a line between black and white given the extent of racial intermixture under slavery (perpetrated by white men, he pointedly noted). Although sound in principle, Grey proved incorrect in the end; state governments found ways to define race.

He was right, however, that the distinction between black and white would not be simple. States’ definitions of the degree of “blood quantum” required to be defined as being a particular race varied over time and place. By the 20 th century, any known presence of African ancestry (the “one-drop rule”) became the measure in many states and in the white public’s imagination. Instead of prejudice lessening over time, whites grew increasingly paranoid about marrying someone with “invisible blackness” and took up genealogy en masse to ferret out “passers.”

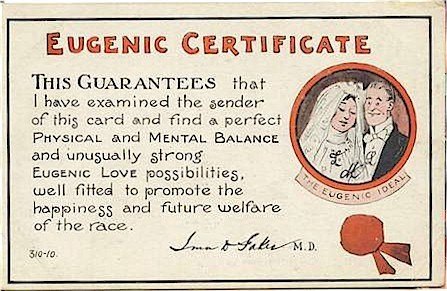

A certificate from 1924 mockingly “guaranteeing” a person’s racial “purity."

Ultimately, county clerks served as the front line in determining race when couples requested marriage licenses and birth certificates. More than merely dictating who could marry each other, racial designations determined where a person could live, work, learn, and socialize.

As the cornerstone of the edifice of Jim Crow, the number of prohibitions against interracial marriage only increased in the late 19 th and early 20 th centuries as new states entered the Union.

Western states adopted prohibitions and included additional groups to discriminate against: people of Asian and American Indian descent. Revealing their true intent to be maintaining white “purity,” none of these laws bothered to prohibit interracial marriages among nonwhite groups or to prohibit marriage among different European nationalities. An Asian American and an African American were free to marry each other, but neither could marry a white person. In contrast, no laws prevented, say, an Italian American and a Polish American from marrying.

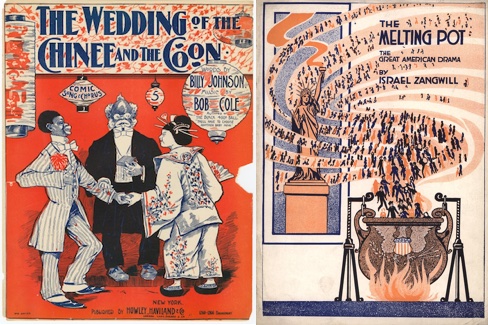

Sheet music from 1897 mocking African Americans and Chinese Americans ( left ). “The Melting Pot” analogy to celebrate America as a blend of nationalities first came into use with Israel Zangwill’s popular 1908 play of the same name ( right ). Conspicuously—and purposefully—absent from his melting pot were African Americans and Asian Americans who Zangwill believed should establish their own homelands elsewhere, even as he advocated for intermarriage among European nationalities.

Even where interracial marriage bans had been repealed, a prominent interracial marriage could ignite white hysteria. Every state in the North except Indiana had repealed its ban by 1887, but when World Heavyweight Boxing Champion Jack Johnson wed interracially in Chicago for the second time in late 1912, white America panicked. In 1913, the U.S. House of Representatives overwhelmingly passed a measure to prohibit interracial marriage in the District of Columbia. Eleven of the 19 states without prohibitions at that time introduced—and nearly passed—bans.

The panic diminished somewhat after an all-white jury convicted Johnson on trumped-up charges of crossing state lines with a woman “for immoral purposes,” but the precariousness of the issue remained a warning for would-be interracial couples and supporters of equal rights.

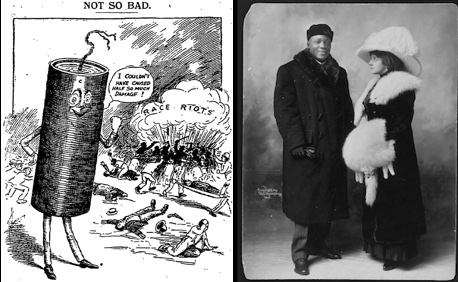

World Heavyweight Boxing Champion Jack Johnson and Etta Terry Duryea, the first of his three white wives, in 1910 ( right ). Attempts to ban interracial marriage at the federal level swept the nation after Johnson’s second marriage to a white woman in 1912. A 1910 cartoon referencing the race riots in more than 50 cities after Jack Johnson defeated the white boxer James Jeffries in what was billed “the fight of the century” and Jeffries the “Great White Hope” ( left ). Johnson's marriage to a white woman likely fueled rioters’ anger.

“One Bombshell at a Time is Enough”: Miscegenation and Civil Rights