- Open access

- Published: 29 February 2024

Prevalence, correlates, and reasons for substance use among adolescents aged 10–17 in Ghana: a cross-sectional convergent parallel mixed-method study

- Sylvester Kyei-Gyamfi 1 ,

- Frank Kyei-Arthur 2 ,

- Nurudeen Alhassan 3 ,

- Martin Wiredu Agyekum 4 ,

- Prince Boamah Abrah 5 &

- Nuworza Kugbey 2 , 6

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy volume 19 , Article number: 17 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

2460 Accesses

1 Citations

9 Altmetric

Metrics details

Substance use among adolescents poses significant risks to their health, wellbeing, and development, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, including Ghana. However, little is known about the outlets and reasons for substance use among Ghanaian adolescents. This study examined the prevalence, correlates, reasons for substance use, and outlets of these substances among adolescents aged 10–17 in Ghana.

Data were obtained from the Department of Children, Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection, Ghana, which employed a cross-sectional convergent parallel mixed-methods technique to collect quantitative and qualitative data from children aged 8–17, parents or legal guardians and officials of state institutions responsible for the promotion and protection of children’s rights and wellbeing. Overall, 4144 adolescents aged 10–17 were interviewed for the quantitative data, while 92 adolescents participated in 10 focus group discussions. Descriptive statistics, Pearson’s chi-square test, and multivariable binary logistic regression were used to analyse the quantitative data, while the qualitative data was analysed thematically.

The prevalence of substance use was 12.3%. Regarding the types of substance use, alcohol (56.9%) and cigarettes (26.4%) were the most common substances. Being a male and currently working are significant risk factors, whereas being aged 10–13, and residing in the Middle- and Northern-ecological belts of Ghana are significant protective factors of substance use. Peers, household members who use substances, drug stores, and drug peddlers are the major outlets. The reasons for substance use were fun, substance as an aphrodisiac, boosting self-confidence, dealing with anxiety, and improved social status.

Conclusions

There is a relatively high substance use among adolescents in Ghana, and this calls for a multi-sectoral approach to addressing substance use by providing risk-behaviour counselling, parental control, and effective implementation of substance use laws and regulations.

Adolescence is a developmental phase associated with a greater risk of experimenting and using substances such as alcohol, cannabis and tobacco [ 1 ]. Substance use among adolescents is of major public health concern because of the short-and long-term effects on their health and safety as well as the broader negative social consequences [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Specifically, substance use is associated with an increased risk of road traffic accidents, violence, sexual risk-taking (such as unprotected sex), mental health disorders (including learning disorders) and suicide. While substance use among adolescents is not new in Ghana, there is evidence of the rising prevalence of some substances and the use of ‘new substances’ (such as tramadol), which have greater intoxicating effects [ 5 ]. According to Kyei-Gyamfi et al. [ 5 ], about 7% of children aged 8–17 in Ghana are lifetime users of alcohol.

In Ghana, multiple laws forbid and govern the use and sale of substances to individuals under 18. For instance, the sale of tobacco products to individuals under the age of 18 is regulated by the Tobacco Control Regulations 2016 (L. I. 2247) [ 6 ] and the Public Health Act, 2012 (Act 851) [ 7 ]. Specifically, the Public Health Act, 2012 (Act 851) forbids smoking tobacco products in public places and advertisements on tobacco products. In Ghana, anti-smoking campaigns, such as the SKY Girls campaign, employed diverse channels, including school and community activities, films, and social media, to dissuade adolescents from smoking [ 8 , 9 ]. The Food and Drugs Authority guidelines for the advertisement of foods [ 10 ] stipulate that advertisements for alcoholic beverages should not appeal to or target individuals under 18. Consequently, the Food and Drugs Authority is responsible for examining and authorising all advertisements related to alcoholic beverages. In addition, alcoholic beverage companies are prohibited from selling or providing their products as prizes for sponsorship programmes at educational institutions.

Also, the Liquor Licensing Act 1970 (Act 331) [ 11 ] regulates the sale of alcoholic beverages to individuals under 18. Act 331 also stipulates that individuals under 18 should not be permitted to enter or be found in any premises where alcoholic beverages are sold. Furthermore, the Narcotic Drugs (Control, enforcement and Sanctions) Act, 1990 (P.N.D.C.L. 236) [ 12 ] forbids the utilisation of narcotic drugs by any individual without legal authorization, including children.

While a body of research exists on substance use in Ghana, it is essential to acknowledge some limitations associated with these studies. First, these studies have mainly used a type of substance to measure substance use (e.g., alcohol use, tobacco use, and shisha use) [ 2 , 5 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. For instance, Kugbey’s [ 2 ] study measured substance use among adolescents using alcohol use, amphetamine use, and marijuana use. Similarly, Asante and Nefale [ 18 ] estimated substance use using alcohol use, cigarette use, marijuana use, glue, heroin, and amphetamine. To the best of our knowledge, no study in Ghana has used varieties of substance use as a composite variable to measure substance use. Second, most studies have focused on in-school adolescents [ 2 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. Third, few studies have interrogated the various sources and outlets where adolescents procure substances [ 5 ]. Therefore, this study examined the prevalence, correlates and reasons for substance use as well as the outlets where such substances are procured among adolescents aged 10–17 in Ghana.

Data and sample

The study employed secondary data as the primary source of information. The data was acquired from the Department of Children within the Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection in Ghana, which employed a cross-sectional convergent parallel mixed-method technique to collect quantitative and qualitative data from children aged 8–17, parents or legal guardians and officials of state institutions responsible for the promotion and protection of children rights and wellbeing. A convergent parallel mixed-method technique enables the simultaneous gathering and examination of quantitative and qualitative data [ 20 ]. The secondary data cover several topics, including children’s rights, substance use, employment, and sexual and reproductive health. This study focused on substance use.

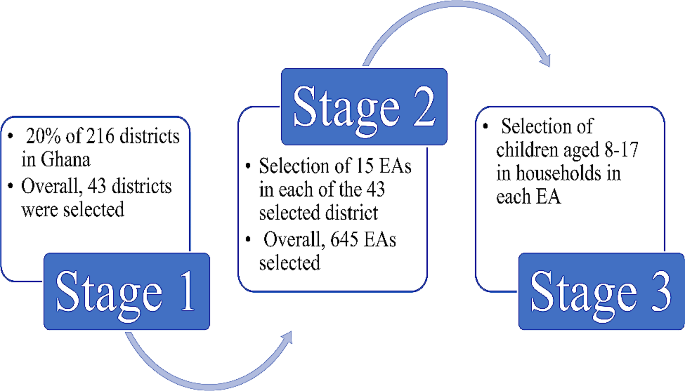

The quantitative data in this study was obtained using a multi-stage sampling procedure to select respondents. In 2018, a sample of 20% of the total 216 districts in Ghana was chosen, with the selection criteria focusing on child welfare issues, such as child rights and child protection. As a consequence, a total of 43 districts were chosen. Furthermore, 645 enumeration areas were selected by choosing 15 enumeration areas in each of the selected 43 districts. Moreover, the study involved the selection of children between the ages of 8 and 17 residing in households within each enumeration area. In each household, it was ensured that just one child between the ages of 8 and 17 was selected for the interview. However, this study focused on adolescents aged 10–17. Overall, 4144 adolescents aged 10–17 were interviewed for the study. Figure 1 is an organisational flow of the multi-stage sampling procedure for the quantitative data collection. The inclusion criteria for children to participate in the study were: they must be aged 8–17, be a member of eligible households in selected EAs, must consent and be willing to participate, and parents/legal guardians must consent for them to participate in the study.

Multi-stage sampling procedure for the quantitative data collection

In order to gather qualitative data, ten focus group discussions (FGDs) were carried out with adolescents aged 10 to 17 years at locations convenient for them. Each FGD consisted of 8–10 participants, encompassing male and female adolescents across various age groups. Overall, 92 adolescents aged 10–17 participated in the ten FGDs. Topics covered in the FGDs included the types of substances adolescents use, where adolescents get substances to use, and the reasons for the use of substances.

The study was approved by the National Child Protection Committee of the Department of Children of the Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection. Adolescents gave their written informed consent before trained research assistants interviewed them. Also, research assistants received written informed consent from parents or legal guardians of eligible adolescents before interviewing them. Experienced research assistants proficient in mixed-method data collection were enlisted and underwent a comprehensive training session on the data collection tools, as well as the objectives and significance of the study. Further information regarding the sampling process might be obtained in prior studies [ 21 ].

Study variables

Dependent variable.

Substance use was the dependent variable for this study. It was a composite variable computed using two questions, “Have you ever taken alcohol?” and “Have you ever taken drugs?”. Respondents who responded “Yes” to either or both questions were classified as engaging in substance use.

Independent variables

The independent variables were sex (Male and Female), age (10–13 and 14–17), education (Less than Junior High School (JHS), JHS, and Senior High School (SHS) and higher), marital status (married and not married), religion (Christianity, Islam, and Other), and currently doing any paid work (Yes and No). The region of residence of respondents was recoded into three (3) ecological belts: Coastal ecological belt (Western, Central, Greater Accra, and Volta regions), Middle ecological belt (Eastern, Ashanti and Brong Ahafo regions), and Northern (Northern, Upper East and Upper West regions) ecological belt.

Statistical analyses

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 was used to perform the statistical analyses for the quantitative data. Descriptive statistics was used to describe the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents and the types of substances respondents use. Pearson’s chi-square test was used to examine the association between substance use and socio-demographic characteristics of respondents. A multivariable binary logistic regression was performed to examine the correlates of substance use. All variables in the quantitative data were determined to be statistically significant at p-value ≤ 0.05.

QSR NVivo version 10 software was used to analyse the qualitative data thematically. The researchers examined all transcripts to gain insights into respondents’ viewpoints regarding substance use among adolescents. Subsequently, the transcripts were thoroughly examined, and utterances pertaining to the substance usage of the adolescents were systematically categorised using codes. Sub-themes were identified from the identification and grouping of similar codes found within the transcripts. Moreover, the process involved clustering comparable sub-themes to generate overarching themes.

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

The socio-demographic characteristics of respondents are displayed in Table 1 . A little more than half of the respondents (50.7%) were males, while most were Christians (76.4%). Most respondents were unmarried (98.9%) and currently not engaged in any paid work (95.2%). Among those currently working, a higher proportion were males (68.3%) than females (31.7%) (See Table S1 in the supplementary material).

More than half of respondents (53.0) were aged 15–17. Also, 3 out of 10 respondents (30.5%) had attained less than JHS education, and about two-fifths (39.6%) resided in the Middle ecological belt.

Prevalence of substance use

The prevalence of substance use was 12.3% (95% CI = 11.34 − 13.37%) (Table 1 ). In terms of sex, a greater proportion of males (15.8%) engaged in substance use than females (8.8%, p ≤ 0.001). More respondents aged 15–17 (18.1%) engaged in substance use than those aged 10–13 (5.9%, p ≤ 0.001). It can be observed that respondents’ education was positively associated with the prevalence of substance use ( p ≤ 0.001). Most respondents with SHS and higher education (19.2%) engaged in substance use, followed by those with JHS (12.0%) and less than JHS (5.7%) education. Also, most respondents who resided in the Coastal ecological belt (16.6%, p ≤ 0.001) and those who are currently doing paid work (28.1%, p ≤ 0.001) engaged in substance use.

Regarding the type of substance respondents use, alcohol (56.9%) and cigarettes (26.4%) were the most common substances (Table 2 ). About 7% of respondents (6.5%) used tramadol, and 4.8% used marijuana. Other substances respondents used include codeine (1.7%), cocaine (1.5%), shisha (1.2%), and heroin (1.0%).

Generally, more male adolescents used all types of substances than female adolescents. For instance, of those adolescents who used codeine, 90% were male, and of those who used tramadol, 86.8% were male. Similarly, older adolescents (14–17 years) generally used all types of substances than younger adolescents (10–13 years), except heroin. For instance, about 9 out of 10 older adolescents (89.5%) used tramadol, while 88.3% used cigarettes. However, more younger adolescents (66.7%) used heroin than older adolescents (33.3%).

Correlates of substance use

From Table 3 , males (AOR = 2.117, 95% C.I. = 1.731–2.589, p ≤ 0.001) and respondents who are currently working (AOR = 1.821, 95% C.I. = 1.295–2.560, p = 0.001) were more likely to engage in substance use. However, respondents aged 10–13 (AOR = 0.333, 95% C.I. = 0.232–0.478, p ≤ 0.001) and residing in the Middle (AOR = 0.510, 95% C.I. = 0.409–0.636, p ≤ 0.001) and Northern (AOR = 0.597, 95% C.I. = 0.451–0.790, p ≤ 0.001) ecological belts were less likely to engage in substance use.

Where respondents get substance

During the FGD with respondents, issues were discussed regarding where children get their substance. Four themes emerged: (a) supplies from their peers, (b) household members who also use substances, (c) purchasing from drug stores, and (d) purchasing from drug peddlers.

(A) supplies from peers

Respondents explained that friends with connections can provide access to illicit substances. They explained that most adolescents who engage in substance use are extremely cautious when searching for their drug of choice, as they are aware that the simplest act of irresponsibility will get them in trouble. As a result, they rely on their peers who also engage in substance use since they can trust them.

Most drug-using young people only associate with peers who also use drugs. Through this, they can establish a network, gain each other’s trust, and obtain supplies, as suppliers find it convenient to give substances to trustworthy individuals. Once a member obtains supplies, they may distribute them within their respective circles. (FGD 1)

(B) household members who use substances

Household members who engage in substance use also serve as suppliers of substances. It was found that some adolescents obtain substances from their siblings, uncles, and other household members who also use substances. One participant explained this phenomenon:

”My first taste of whisky came from my older brother’s room. Since I frequently observe him drinking before meals, I decided to try it one day, and it has since become my primary source of alcohol. Some of my smoking acquaintances obtain their supplies from their brothers, too. (FGD 2)”.

(C) purchasing from drug stores

The FGDs with adolescents revealed that some adolescents acquire tramadol from small medicinal retail outlets known as ‘drug stores’. Adolescents explained that acquiring such medications from a pharmacy is risky due to the possibility of being tracked down for drug use. A participant explained:

When customers enter small drugstores in densely populated communities, they are rarely asked what they intend to use the medication for. Not so with pharmacies, which are well-established and staffed by licenced pharmacists. Due to this, some adolescents purchase codeine and tramadol from them to avoid getting caught. (FGD 3)

(D) purchasing from gangs

Adolescents’ narratives highlighted that they purchase substances from gangs, who often get their supplies from drug peddlers. However, the gangs only sell to individuals they know and can vouch that they may not expose them to the police. Adolescents explained that one must be known to be a reliable client before buying from a gang. These gangs are not at specific locations but operate in areas noted for substance use.

Drug peddlers who occasionally offer marijuana do not sell to adolescents. Typically, an adult member of a gang buys it and distributes it around the groups, usually on the basis that he receives a free supply, while adolescents or underage members provide monies for the purchase of the marijuana. (FGD 4)

Reasons for substance use

Adolescents narrated varied reasons for using substances. Five themes emerged: (a) substance use is fun, (b) use of substances as an aphrodisiac, (c) boosts confidence to approach the opposite sex, (d) forgetting anxieties, and (e) substance use makes one popular and being perceived as the finest.

(A) substance use is fun

For some adolescents, substance use is fun. Occasionally, meeting friends, drinking, and smoking add spice to the entertainment of adolescents. One of the adolescents described how he has enjoyed drinking with his neighbourhood friends over the years:

The greatest time of my life is when my friends and I assemble at drinking places [pubs], listen to music, dance to some songs, consume alcohol, smoke, and party. Life is great when unwinding with friends. (FGD 5)

(B) use of substances as an aphrodisiac

During the FGD, it emerged that the use of tramadol, also known as ‘Tramol’, has become widespread among many adolescents in the country’s urban communities since it serves as an aphrodisiac, which enhances their sexual performance. One adolescent stated:

Boys who use Tramol in my area claim that it allows them to have long-lasting sexual intercourse with their partners whenever they have sex. As a result, many adolescents use Tramol as an aphrodisiac. (FGD 6)

(C) boosts confidence to approach the opposite sex

Some adolescents believe that when they use substances, it boosts their confidence to approach the opposite sex. They use substances to overcome their shyness to approach the opposite sex. Below is the narrative of a respondent:

Some of the boys drink alcohol or even smoke marijuana because they may lack the confidence to approach a girl they are interested in. However, they firmly believe that by using drugs, they will become high and be better positioned to accomplish their goal of flirting with the girls. (FGD 7)

(D) forgetting anxieties

The FGD with adolescents revealed that some adolescents use substances to help them forget about their anxieties about the lack of employment opportunities, educational opportunities, and other family issues. One participant explained why he has been drinking:

I finished Polytechnic and have been home for two years without a job. Most of my peers are in similar situations, so when we get together, those of us with money purchase drinks and split them amongst ourselves so we can commiserate and console ourselves about our jobless situations. (FGD 8)

(E) substance use makes one popular and being perceived as the finest

Adolescents revealed that some adolescents have the misconception that engaging in substance use makes them popular and perceived as the ‘finest’ [best] in their peer group. The following were the sentiments expressed:

Most children who smoke cigarettes and marijuana believe they become popular with their peers and are highly regarded as the finest guys in their group when they smoke. Many boys and girls of my age group are influenced to indulge in substance use due to the widespread prevalence of these misconceptions. (FGD 9)

Although there have been many studies conducted on substance use in Ghana, only a limited number of these studies have utilised multiple types of substances to assess substance use. Moreover, most of these studies have concentrated on adolescents attending school. At the same time, only a limited number of studies have examined the diverse channels and locations through which adolescents obtain substances. To close this disparity in knowledge, this study examined the prevalence, correlates and reasons for substance use as well as the outlets where such substances are procured among adolescents aged 10–17 in Ghana. The findings of this study would contribute to the literature on substance use, and it would help to inform policymakers in providing programmatic responses to address substance use among adolescents, which has long-term health implications for their lives.

We found that the prevalence of substance use among adolescents was 12.3%. The prevalence of substance use in this study is higher than that of 6.6% found in 7.2% in Uganda [ 22 ] and 11.3% in sub-Saharan Africa [ 2 ]. In contrast, the prevalence of substance use in this study is lower than 16.0% in India [ 23 ], 17.1% in Southern Brazil [ 24 ], 32.9% in Nigeria [ 25 ], and 48% in South Africa [ 26 ]. A study in Northern Tanzania reported a lifetime and current prevalence of substance use of 19.7% and 12.8%, respectively [ 27 ]. The variation in the prevalence of this study and other studies could be attributed to the sample size of adolescents, socio-cultural factors, demographic characteristics, age of adolescents and the types of substance use that were considered in each study. For instance, Mavura et al. [ 27 ] considered alcohol, cigarette smoking, marijuana, khat, and recreational drugs (cocaine, heroin) in their study, while in this study, we considered alcohol, smoking and drugs (Marijuana, heroin, cocaine, codeine and tramadol). In addition, the differences in the age of adolescents could account for the variations in the prevalence of substance use among adolescents. In this study, we considered adolescents aged 10–17. However, Kugbey’s [ 2 ] study participants were aged 11–18, while Mmereki et al.’s [ 26 ] study participants were aged 13–21.

The results of this study show that alcohol was the most common substance used among adolescents, followed by smoking (cigarettes), tramadol, marijuana, codeine, cocaine, shisha and heroine. The findings of this study are similar to a study by Mavura et al. [ 27 ], who reported alcohol as the common substance use by adolescents in Tanzania. Similar findings were found by Anyanwu et al. [ 25 ] in Nigeria, Birhanu et al. [ 28 ] in Northwest Ethiopia, and Olawole-Isaac et al. [ 29 ] in Sub-Saharan Africa. The probable reason for the high prevalence of alcohol use may be attributed to the visibility and advertisement of alcohol in Ghana, which may entice adolescents to drink. Akesse-Brempong and Cudjoe [ 30 ] argued that there is a pervasive and robust advertising campaign promoting the consumption of alcoholic beverages in Ghana, which has the potential to influence adolescents to consume alcohol. Aside from the advertisement, there are more drinking spots where adolescents can easily access any alcoholic beverage. Hormenu et al. [ 14 ] reported that in Ghana, about 42.3% of adolescents have ever consumed alcohol. It is, therefore, not surprising that alcohol was the major substance used by adolescents in this study. In addition, studies have identified smoking cigarettes as the second substance adolescents use [ 25 , 27 , 28 ]. In contrast, Srivastava et al. [ 23 ] found the use of tobacco to be higher in India than alcohol.

The findings of the study show that males were more likely to engage in substance use than females, similar to other studies [ 2 , 5 , 28 , 31 ]. The higher use of substances among males may be attributed to gender roles, peer influence and sensation-seeking behaviour, which sometimes forces males to use substances to enable them to behave as they desire [ 28 ]. Iwamoto et al. [ 32 ] reported that substance use, such as alcohol and drugs, shows masculinity, whereas men who do not take alcohol or drugs are considered weak. Men conform to these masculine norms or beliefs, such as “playboy” and “risk-taking and self-reliance”, which increase their risk of substance use. In contrast, engaging in substance use among females is sometimes seen as shameful, and society frowns on it [ 2 ]. Due to this, there could be a situation of underreporting of substance use among adolescent females.

The study results show that adolescents aged 10–13 years were less likely to engage in substance use than those aged 14–17 years. The finding of this study is similar to other studies that reported substance use practice among older adolescents than younger adolescents [ 25 , 26 ]. The probable reason could be that as adolescents grow, they begin to live independent lives by making their own decisions, and this sometimes leads them to engage in unhealthy lifestyles such as drinking alcohol and taking drugs. Older adolescents become susceptible to experimentation with different things, such as drugs and alcohol. Sometimes, this is done out of curiosity or peer pressure from friends as they age [ 25 , 33 ]. However, older adolescents may lack the knowledge and consequences of using these substances, and their continuous use may lead to addiction.

In addition, we found that adolescents who were currently working were more likely to engage in substance use than those who were not working. Adolescents who are working may have the financial resources to purchase substances to use than those who are not working. This finding is similar to previous studies, which found that respondents who were working as vulnerable groups that engaged in substance use [ 23 , 34 , 35 ]. However, this finding is contrary to Masferrer et al. [ 36 ] study, which found substance use is more likely among respondents who are not working.

Furthermore, adolescents residing in the Coastal ecological belt are more likely to engage in substance use than those living in the Middle and Northern ecological belts. Previous studies have found the use of alcohol among persons residing in Coastal areas in Ghana [ 37 ]. Also, the use of tramadol has been documented to be more prevalent in the Greater Accra, Volta, and Western regions, which are found in the Coastal ecological belt [ 38 ]. Kyei-Gyamfi and Kyei-Arthur’s [ 19 ] study on substance smoking in Ghana found cigarette smoking to be more prevalent in the Coastal ecological belt than in the Middle and Northern belts of Ghana. These factors may explain why adolescents living in the Coastal ecological belt are more likely to use substances than those in the Middle and Northern ecological belts.

Consistent with other studies [ 39 , 40 ], the findings of this study revealed various reasons for substance use, such as for fun, as an aphrodisiac, to boost confidence to approach the opposite sex, forgetting anxieties, making one popular and being perceived as the finest. The probable reason for this could be that most adolescents are sometimes shy of approaching the opposite sex. Therefore, they use substances to boost their confidence to approach them. In addition, due to youthful exuberances, adolescents are involved in risky sexual behaviour and, therefore, use various substances as aphrodisiacs to please their partners during sex [ 41 ]. In Ghana, Attila et al. [ 42 ] reported that substance use among adolescents is due to curiosity, which is similar to the findings of this study.

The study found that adolescents obtained their substances from peers, household members who engage in substance use, drug stress and gangs. Similar findings of this study have been reported by other studies [ 43 , 44 ]. For instance, Lopez-Mayan & Nicodemo [ 43 ] reported that peers significantly influence adolescent substance use in Spain. These adolescents get the substances from their peers in schools, thereby impacting their use. Schuler et al.’s [ 44 ] study in Southern California reported that adolescents acquire the substance they use from their friends and family members. Similarly, Srivastava et al.’s [ 23 ] study in India found that the probability of an adolescent engaging in substance use is heightened when they have a family member who also engages in substance use. Thus, peers and family members who use substances may influence adolescents to also use substances.

Limitations

There are some limitations to this study. First, substance use was defined as the lifetime use of a substance, and it was measured by a single question, which was not a robust measure of substance use. Second, children were asked if they had ever used substances. Since substance use is regarded as a deviant behaviour and unlawful, children might fail to disclose their use. Third, there may also be recall bias because children must recollect when they used a substance, which may lead to under reporting of their experiences. Fourth, because this is a cross-sectional study, we are unable to establish causal links between the dependent and independent variables. Despite these limitations, the data’s national representativeness would allow policymakers and researchers to tackle substance use among adolescents across the country.

This study revealed a relatively high prevalence of substance use (12.3%) among adolescents, and alcohol and cigarettes were the main substances used by adolescents. Adolescents obtain the substances they consume from their peers and household members who are substance users, as well as from drug stores and drug peddlers. The study highlighted adolescent’s age, sex, ecological zone of residence and working status as significant correlates of substance use.

Furthermore, it emerged that adolescents use substances because they want to boost their self-confidence to approach the opposite sex, forget their anxieties, and it served as a form of aphrodisiac. Other adolescents use substances since they perceive them as fun, and the use of substances makes their peers perceive them as famous.

Though the study found that only a little over one-tenth of adolescents (12.3%) used substances, substance use is detrimental to the health and wellbeing of adolescents. Consequently, there is a need for muti-sectoral collaborations between institutions mandated to enhance the wellbeing of adolescents and implement substance use laws and regulations, such as the Narcotic Control Authority, the Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection, and other child protection partners, to help reduce adolescent substance use. Also, there is a need to provide risk-behaviour counselling to adolescents and to strengthen parent control to help curb adolescent substance use in Ghana.

Data availability

The raw data for the findings of this study are freely available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

Adjusted Odds Ratio

Confidence Interval

Focus Group Discussions

Junior High School

Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection

Reference Category

Senior High School

West AB, Bittel KM, Russell MA, Evans MB, Mama SK, Conroy DE. A systematic review of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and substance use in adolescents and emerging adults. Translational Behav Med. 2020;10(5):1155–67.

Article Google Scholar

Kugbey N. Prevalence and correlates of substance use among school-going adolescents (11–18 years) in eight Sub-saharan Africa countries. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2023;18(1):1–9.

Moodley SV, Matjila MJ, Moosa M. Epidemiology of substance use among secondary school learners in Atteridgeville, Gauteng. South Afr J Psychiatry. 2012;18(1):2–7.

Google Scholar

Stockings E, Hall WD, Lynskey M, Morley KI, Reavley N, Strang J, Patton G, Degenhardt L. Prevention, early intervention, harm reduction, and treatment of substance use in young people. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):280–96.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Kyei-Gyamfi S, Wellington N, Kyei-Arthur F. Prevalence, reasons, predictors, perceived effects, and regulation of alcohol use among children in Ghana. Journal of Addiction 2023, 2023.

Government of Ghana. Tobacco Control regulations 2016 (L.I. 2247). Accra: Government of Ghana; 2016.

Government of Ghana. Public Health Act, 2012 (Act 851) Accra. Government of Ghana; 2012.

Hutchinson P, Leyton A, Meekers D, Stoecker C, Wood F, Murray J, Dodoo ND, Biney A. Evaluation of a multimedia youth anti-smoking and girls’ empowerment campaign: SKY girls Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–18.

Karletsos D, Hutchinson P, Leyton A, Meekers D. The effect of interpersonal communication in tobacco control campaigns: a longitudinal mediation analysis of a Ghanaian adolescent population. Prev Med. 2021;142:106373.

Food and Drugs Authority. Guidelines for the advertisement of foods Accra. Food and Drugs Authority; 2013.

Government of Ghana. Liquor Licensing Act– 1970 (Act 331). Accra: Government of Ghana; 1970.

Government of Ghana. Narcotic drugs (control, enforcement and sanctions) Act, 1990 (P.N.D.C.L. 236). Accra: Government of Ghana; 1990.

Asante KO, Kugbey N. Alcohol use by school-going adolescents in Ghana: prevalence and correlates. Mental Health Prev. 2019;13:75–81.

Hormenu T, Hagan Jnr JE, Schack T. Predictors of alcohol consumption among in-school adolescents in the Central Region of Ghana: a baseline information for developing cognitive-behavioural interventions. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11):e0207093.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Logo DD, Oppong FB, Singh A, Amenyaglo S, Wiru K, Ankrah ST, Musah LM, Kyei-Faried S, Ansong J, Owusu-Dabo E. Profile and predictors of adolescent tobacco use in Ghana: evidence from the 2017 Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS). J Prev Med Hyg. 2021;62(3):E664.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Parimah F, Davour MJ, Tetteh C, Okyere-Twum E. Shisha Use is Associated with Deviance among High School students in Accra, Ghana. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2022;54(1):54–60.

Massawudu LM, Logo DD, Oppong FB, Afari-Asiedu S, Nakobu Z, Baatiema L, Boateng JK. Predictors of cigarette and shisha use in Nima and Osu communities, Accra, Ghana: a cross-sectional study. Pneumon. 2021;34(4):20.

Asante KO, Nefale MT. Substance use among street-connected children and adolescents in Ghana and South Africa: a cross-country comparison study. Behav Sci. 2021;11(3):28.

Kyei-Gyamfi S, Kyei-Arthur F. Assessment of prevalence, predictors, reasons and regulations of substance smoking among children in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):2262.

Edmonds W, Kennedy T. Convergent-parallel approach. An applied guide to research designs: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. 2nd ed. New York: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2016.

Kyei-Gyamfi S, Coffie D, Abiaw MO, Hayford P, Martey JO, Kyei-Arthur F. Prevalence, predictors and consequences of gambling on children in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):2248.

Kaggwa MM, Abaatyo J, Alol E, Muwanguzi M, Najjuka SM, Favina A, Rukundo GZ, Ashaba S, Mamun MA. Substance use disorder among adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Uganda: retrospective findings from a psychiatric ward registry. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(5):e0269044.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Srivastava S, Kumar P, Rashmi, Paul R, Dhillon P. Does substance use by family members and community affect the substance use among adolescent boys? Evidence from UDAYA study, India. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–10.

Tavares BF, Béria JU, Lima MSD. Factors associated with drug use among adolescent students in southern Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2004;38:787–96.

Anyanwu OU, Ibekwe RC, Ojinnaka NC. Pattern of substance abuse among adolescent secondary school students in Abakaliki. Cogent Med. 2016;3(1):1272160.

Mmereki B, Mathibe M, Cele L, Modjadji P. Risk factors for alcohol use among adolescents: the context of township high schools in Tshwane, South Africa. Front Public Health. 2022;10:969053.

Mavura RA, Nyaki AY, Leyaro BJ, Mamseri R, George J, Ngocho JS, Mboya IB. Prevalence of substance use and associated factors among secondary school adolescents in Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(9):e0274102.

Birhanu AM, Bisetegn TA, Woldeyohannes SM. High prevalence of substance use and associated factors among high school adolescents in Woreta Town, Northwest Ethiopia: multi-domain factor analysis. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–11.

Olawole-Isaac A, Ogundipe O, Amoo EO, Adeloye D. Substance use among adolescents in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. South Afr J Child Health. 2018;12(2 Suppl 1):79–S84.

Akesse-Brempong E, Cudjoe EC. The Alcohol Man: portrayals of men in Popular Ghanaian Alcoholic Beverage Advertisements. Adv Journalism Communication. 2023;11(2):136–57.

Chivandire CT, January J. Correlates of cannabis use among high school students in Shamva District, Zimbabwe: a descriptive cross sectional study. Malawi Med J. 2016;28(2):53–6.

Iwamoto DK, Cheng A, Lee CS, Takamatsu S, Gordon D. Man-ing up and getting drunk: the role of masculine norms, alcohol intoxication and alcohol-related problems among college men. Addict Behav. 2011;36(9):906–11.

Ngesu LM, Ndiku J, Masese A. Drug dependence and abuse in Kenyan secondary schools: strategies for intervention. Educational Res Reviews. 2008;3(10):304.

Gupta S, Khandekar J, Gupta N. Substance use: risk factors among male street children in Delhi. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2013;4(1):163.

Fentaw KD, Fenta SM, Biresaw HB. Prevalence and Associated factors of Substance Use Male Population in East African countries: a multilevel analysis of recent demographic and health surveys from 2015 to 2019. Subst Abuse: Res Treat. 2022;16:11782218221101011.

Masferrer L, Garre-Olmo J, Caparrós B. Is complicated grief a risk factor for substance use? A comparison of substance-users and normative grievers. Addict Res Theory. 2017;25(5):361–7.

Kyei-Arthur F, Kyei-Gyamfi S. Alcohol consumption and risky sexual behaviors among fishers in Elmina in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1328.

Health Minister warns of dangers of Tramadol abuse [ https://www.moh.gov.gh/health-minister-warns-of-dangers-of-tramadol-abuse/ ].

Nawi AM, Ismail R, Ibrahim F, Hassan MR, Manaf MRA, Amit N, Ibrahim N, Shafurdin NS. Risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–15.

Dow SJ, Kelly JF. Listening to youth: adolescents’ reasons for substance use as a unique predictor of treatment response and outcome. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27(4):1122.

Dumbili EW. Gendered sexual uses of alcohol and associated risks: a qualitative study of Nigerian University students. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1–11.

Attila FL, Agyei-Sarpong K, Asamoah-Gyawu J, Dadebo AA, Eshun E, Owusu F, Barimah SJ. Youthful curiosity as a predictor of substance use among students. Mediterranean J Social Behav Res. 2023;7(2):59–64.

Lopez-Mayan C, Nicodemo C. If my buddies use drugs, will I? Peer effects on Substance Consumption among teenagers. Econ Hum Biology. 2023;50:101246.

Schuler MS, Tucker JS, Pedersen ER, D’Amico EJ. Relative influence of perceived peer and family substance use on adolescent alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use across middle and high school. Addict Behav. 2019;88:99–105.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank all respondents who made this study possible and the Department of Children, Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection for granting us access to this dataset.

We did not receive any funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Children, Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection, Accra, Ghana

Sylvester Kyei-Gyamfi

Department of Environment and Public Health, University of Environment and Sustainable Development, Somanya, Ghana

Frank Kyei-Arthur & Nuworza Kugbey

African Institute for Development Policy, Lilongwe, Malawi

Nurudeen Alhassan

Institute for Educational Research and Innovation Studies, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana

Martin Wiredu Agyekum

Department of Social Welfare, Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection, Accra, Ghana

Prince Boamah Abrah

Department of General Studies, University of Environment and Sustainable Development, Somanya, Ghana

Nuworza Kugbey

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed equally. All authors wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Finally, all the authors contributed to the editing of the manuscript, as well as reading and approving the final version submitted.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Frank Kyei-Arthur .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate.

The National Child Protection Committee of the Department of Children of the Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection gave administrative approval for the collection of the secondary data used for this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. All adolescents and their parents or legal guardians gave their written consent to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Working status of adolescents by sex.

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kyei-Gyamfi, S., Kyei-Arthur, F., Alhassan, N. et al. Prevalence, correlates, and reasons for substance use among adolescents aged 10–17 in Ghana: a cross-sectional convergent parallel mixed-method study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 19 , 17 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-024-00600-2

Download citation

Received : 27 September 2023

Accepted : 19 February 2024

Published : 29 February 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-024-00600-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Substance use

- Risk factors

- Protective factors

- Adolescents

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy

ISSN: 1747-597X

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Where is the pain? A qualitative analysis of Ghana’s opioid (tramadol) ‘crisis’ and youth perspectives

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Ad Astra Foundation, Tamale, Ghana, Oxford School of Global and Area Studies, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom, Department of Community Health & Epidemiology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada

- Jacob Albin Korem Alhassan

- Published: December 21, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001045

- Reader Comments

Over the last five years, media reports in West African countries have suggested a tramadol abuse ‘crisis’ characterised by a precipitous rise in use by youth in the region. This discourse is connected to evidence of an emerging global opioid crisis. While the reported increase in tramadol abuse in West Africa is likely true, few studies have critically interrogated structural explanations for tramadol use by youth. Nascent academic literature has sought to explain the rise in drug use as a function of moral weakness among youth. This Ghanaian case study draws on primary and secondary data sources to explore the pain that precedes tramadol abuse. Through a discourse analysis of 295 media articles and 15 interviews (11 with youth who currently use tramadol and 4 with health system stakeholders), this study draws on structural violence and moral panic theories to contribute to the emerging literature on tramadol (ab)use in West Africa. The evidence parsed from multiple sources reveals that government responses to tramadol abuse among Ghanaian youth have focused on arrests and victim blaming often informed by a moralising discourse. Interviews with those who use tramadol on their lived experiences reveal however that although some youth use the opioid for pleasure, many use tramadol for reasons related to work and feelings of dislocation. A more complex way to understand tramadol use among young people in Ghana is to explore the pain that leads to consumption. Two kinds of pain; physical (related to strenuous work) and non-physical (related to anxiety and the condition of youth itself) explain tramadol use requiring a harm reduction and social determinants of health approach rather than the moralising ‘war on drugs’ approach that has been favoured by policy makers.

Citation: Alhassan JAK (2022) Where is the pain? A qualitative analysis of Ghana’s opioid (tramadol) ‘crisis’ and youth perspectives. PLOS Glob Public Health 2(12): e0001045. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001045

Editor: Khameer Kidia, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, UNITED STATES

Received: March 6, 2022; Accepted: November 25, 2022; Published: December 21, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Jacob Albin Korem Alhassan. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Excerpts of the transcripts relevant to the study are available within the paper. Anonymized transcripts are not publicly available due to ethical and legal reasons (participants discuss their use of illicit drugs). The author can make raw data/transcripts available upon request and as appropriate.

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1. Introduction

“It is important we let people know that abusing medicines like tramadol can have bad consequences including death” [ 1 ]. These words by the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Ghana’s Food & Drugs Authority (FDA) were published in an article on 5 May 2018 on GhanaWeb , one of Ghana’s main online news outlets. Although a couple of years prior most newspaper articles did not routinely mention tramadol or its popularly contracted form “tramol” in their reportage (see Fig 1 ), by 2018 it had become common to see newspaper publications and radio and television programs dedicated to helping solve the tramadol ‘crisis’. In the ensuing months international news outlets such as Deutsche Welle all pointed to a rising trend in the consumption of “cheap and accessible” opioids by Ghanaian and West African youth [ 2 ]. While the current West African situation was linked to tramadol, it must be understood in the context of more complex histories of drug use in Africa [ 3 ] and a rise in opioid use globally driven by multiple factors ranging from “aggressive marketing” [ 4 ] by pharmaceutical industries to changing criminal networks connecting and distributing drugs across continents [ 5 ]. The opioid crisis is increasingly recognised as a global health issue particularly in North American and European contexts where pharmaceutical companies are beginning to be held accountable for decades of over-prescribing opioids while understating the dangers of opioid use [ 6 ].

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Source: Author.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001045.g001

Reports of precipitous increases in drug use have become common across several African countries for different drugs. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic for example, associated joblessness has led to a rise in drug use in countries such as Zimbabwe where more youth use crystal meth [ 7 ], while recent research evidence from South Africa illustrates increasing heroin use among the young male labouring poor, many of whom have precarious employment and use heroin as a coping mechanism [ 8 ].

This article is situated in the broader context of drug use in Africa, discourses of a dangerous and precipitous rise in drug use, especially among youth, and questions on how to explain this issue. In this article, I explore the reported rise in tramadol consumption and use in Ghana and media portrayal of this phenomenon over the last five years. I argue that the framing of the tramadol ‘crisis’ was a moral panic and that such framings helped justify the solutions the government and key stakeholders have adopted to respond to its use—namely, public education and arrests while ignoring root causes of drug use such as poor economic prospects. Relying on the lived experiences of Ghanaian youth who use tramadol, I draw on rich local descriptions to offer a different way of thinking about these youth, as many are simply young people striving to survive in an economy where their situations are highly precarious.

Drawing on key themes in Africanist scholarship, I contribute to this nascent literature by critically (re)interpreting the rise in tramadol use in Ghana in the context of youth and waithood. I argue that its use needs to be understood in the context of the physically demanding and precarious employment conditions many young Ghanaians face, their anxiety and uncertainty regarding their prospects and the demanding conditions of work with which many of them must contend.

Finally, I argue that a better way to understand tramadol use among young people in Ghana is to explore the pain that leads to consumption while moving away from the moralising discourses that have been the core approach of the government and other stakeholders. By paying particular attention to pain and themes of youth—and through a proposed framework—I show that tramadol is used as a coping mechanism for many young people who are struggling to find their place in the context of perpetual waithood and global neoliberal processes that shape young people’s lives [ 9 ]. The reality of tramadol use requires improvement of young people’s economic prospects and strengthening of mental health systems rather than victim blaming.

1.1 Tramadol in Ghana

Tramadol is a pharmaceutical drug with weak μ-opioid agonist properties, whose M1 metabolite is the primary mechanism for its analgesic (pain killer) effect [ 10 ]. The drug was originally distributed by the German pharmaceutical company Grünenthal in 1977. It was historically used to treat pain in situations where paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and cyclooxygenase (Cox)-II inhibitors were insufficient or in patients without tolerance to these alternatives [ 11 ]. It is the only opioid not under international drug control. Multiple meetings (four between 1992 and 2006) by the World Health Organisation Expert Committee on Drug Dependence (ECDD) concluded that tramadol has low abuse potential especially among those with no history of substance use although research from China showed some evidence of abuse potential [ 12 ].

The emerging academic literature on tramadol in Ghana falls into two main categories. (There is a third emerging literature on the role of the media in the tramadol ‘crisis’; see Thompson and Ofori-Parku) [ 13 ].

First, there is a developing body of epidemiological literature describing patterns of tramadol use. In a study by Elliason and colleagues [ 14 ] in the Wassa Amenfi West Municipality in the Western Region, consumption patterns were compared by socio-demographic characteristics. Among those sampled the study found that 45% of those who consume tramadol were male and 49% were aged 16–30. One of the most interesting findings from the study which did not receive much analytical attention was the fact that only two per cent (2%) of those who consume tramadol worked in the ‘formal sector.’ Saapiire et al. [ 15 ] based on research in Jirapa in northern Ghana also recently reported a high prevalence of tramadol abuse especially among males (90.7%) compared to females (9.3%) and concluded that formal sector employment is “protective against tramadol abuse.” Given the high percentage of usage among young men working in the informal sector, it would be useful to explore why this demographic uses tramadol more and the ways the context of work may be implicated.

The second body of published academic literature on tramadol has been qualitative studies exploring facilitators and motivations for use. The qualitative literature describes some of the context of this use and primarily focuses on motivations for use and effects of tramadol on users. Fuseini et al. [ 16 ] concluded for example that peer pressure, curiosity and post-traumatic addiction are the main initiating factors for tramadol use. This study also argued that effects of consumption can be desirable (analgesic psychological effects and even aphrodisiac effects) or undesirable (vomiting and seizures or irritability and aloofness) [ 16 ]. Finally, in a qualitative study in Kumasi, Peprah and colleagues [ 17 ] also drew similar conclusions regarding the drivers of tramadol consumption, arguing that people use it because of sexual, psychological and physical motivations.

There are some gaps in the emerging tramadol literature and opportunities for further research. First, most of the literature focuses on the effects of consumption rather than structural causes of tramadol use. Additionally, academic publications on effects of tramadol use have highlighted key challenges including suicide ideation [ 18 ] although almost no overdoses have been reported from Ghana unlike has been the case with opioid crises elsewhere [ 4 ]. The absence of academic reports on overdoses could be because of the lower potency of tramadol although it could also be a function of data unavailability in the African context [ 19 ]. In countries such as the Islamic Republic of Iran for example, overdose rates from tramadol are high and a common cause of poisoning admissions to emergency departments [ 19 ]. Given these dynamics, as the tramadol situation continues to evolve in Ghana, there might be potential lessons for other contexts where stigma related to opioid use has been connected to high overdose rates. Moreover, although extant studies have described the demographic characteristics of tramadol users and highlighted high usage among men, informal sector workers and youth, they have done so mainly through descriptive statistics. This necessitates more research on the lived experience of youth who use tramadol. Finally, there is an emerging interest in harm reduction in Ghana -in the form of needle exchange programs, HIV and hepatitis B & C prevention strategies [ 20 ]—as has been advocated for in Europe and North America. The fact that tramadol is predominantly orally ingested means that new approaches to harm reduction will need to be envisioned drawing on the lived experiences of those who use tramadol.

Drug use is always influenced by a complex set of factors including “productivity, pleasure and intimacy” [ 21 ] thus a biopsychosocial understanding demands a delicate balancing of the deeper structural factors that construct the world inhabited by those who use drugs with their complex lived experiences [ 22 ]. This study turns the analytical gaze toward pain . Such attention reveals the broader causes of tramadol use because attention to and analysis of pain reveals “how the bodily experience itself is influenced by meanings, relationships, and institutions” [ 23 ].

2. Theoretical orientations

This article draws on multiple theories to problematise ongoing framings of tramadol use. First, it draws on the notion of a ‘moral panic’, a state that occurs when “a condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests” [ 24 ]. As applied to youth in Africa, the notion of moral panic is of particular importance given the historical and ongoing representation of African youth as “unruly, destructive and dangerous forces needing containment” [ 25 ]. In practical terms, throughout the article and in analyses, references to tramadol use by youth as “immoral” or a “crisis” are treated with some scepticism while assuming that particular framings of young people as irresponsible drug users can be used by those in power to deflect attention from root causes of drug use [ 26 ].

Secondly, the article draws on anthropological theories of structural violence and the idea of the social determinants of health. The concept of ’structural violence’ was first used by Galtung [ 27 ] to differentiate violence that is direct or interpersonal from violence that is built into social structures. Galtung’s original article was in the field of Peace Studies, however this idea has subsequently been used by authors across disciplines to explore how social structures reduce people’s life chances. For medical anthropologist Paul Farmer [ 28 ], structural violence is “violence exerted systematically” and to study this is to explore the “social machinery of oppression.” Understanding health issues such as addiction therefore requires attention to the ‘pathologies of power,’ the structures that force people to engage in health-destructive behaviours [ 29 ]. Many researchers have used this approach to understand the health of marginalised groups such as Latino migrant workers in the USA [ 30 ] or the drug economy in deindustrialised urban contexts [ 31 ]. I reinterpret tramadol use by Ghanaian youth in the context of the broader social structures of oppression in which they live and work. I draw as well on the idea of the social determinants of health [ 32 ] which posits that health behaviours are influenced by social structures. Thus, where problematic drug use emerges in the analysis, I emphasise the importance of harm reduction principles and addressing the living conditions of youth as an essential step in improving the lives of those who use tramadol.

3. Methods of the study

Ethics statement.

This study received ethics approval from the University of Oxford Social Sciences and Humanities Interdivisional Ethics Committee (SSH_OSGA_ASC_C1_21_030). The study also received an ethics exemption under the Ghana Health Services Ethics Review Committee Standard Operating Procedures 2015 given that it involved interviews with voluntary participants who gave informed consent. Informed consent was obtained from participants verbally and recorded before each interview. Three affirmations were used to secure informed consent. Each participant confirmed (1) that their participation in the research was voluntary, (2) that they give their verbal consent to participate, and (3) that a voice recorder could be used to record responses. The 11 participants received a $10 honorarium each.

Study design

This study is part of a broader research project to understand the drivers of tramadol use among West African youth. I report here mainly on the newspaper sources with some references to interview data although a longer discussion of lived experiences of youth who use tramadol is reported elsewhere [ 33 ]. The research employed a qualitative case study methodology [ 34 ] drawing on multiple methods and relying on primary and secondary data sources. The secondary data analysis involved a discourse analysis [ 35 ] of media reportage on tramadol use in Ghana between 2012 and 2020. In total, 295 newspaper articles were systematically extracted from newspaper search site Factiva , imported into NVivo 12 software, and inductively coded to describe discourses on tramadol consumption (see Fig 1 . for trends in reportage and S1 Table for codes). To conduct the discourse analysis, each article was read in its entirety and coded for: 1) how it described those who use tramadol; 2) explanations offered for tramadol use; 3) descriptions of the effects of tramadol use; and 4) how each article framed the solution to the problem of tramadol use. Once this process was completed codes were combined to explore patterns and to describe the dominant frames used in writing about the tramadol crisis [ 35 ].

Additionally, primary qualitative interviews (lasting between 30 min. and 1 h 15 min.) were conducted with fifteen (15) individuals between March and May 2021 via telephone due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and imported into NVivo 12 software. The final sample of 15 participants was considered appropriate based on emerging analysis that revealed similar responses across interviews (approaching saturation) and the unpredictable pandemic context where interview data collection could only be performed at a distance. Recruitment was done through purposive sampling after a research poster was circulated on social media. Other participants were recruited through personal contacts given the sensitive nature of the research topic. Interviewees consisted of eleven (11) people (ten males and one female) who were currently using tramadol and worked in diverse professions (tricycle riders, self-identified ‘hustlers’, students, teachers, masons etc.). For these 11 participants the criteria for inclusion was that they be youth (age 15–35) who used tramadol [ 36 ]. Interviewees included in this analysis were aged 19–35 and had used tramadol over the last year. Interviews were conducted in English, Dagbani and pidgin English using a semi-structured interview guide. Interviewees were asked to provide a short life history, describe what led them to tramadol use, highlight socioeconomic factors that explain why they use tramadol and describe societal views of those who use tramadol. They were also asked to comment on any available supports if they wanted to stop using tramadol and finally, they were asked to share their hopes for the future ( S1 Text ).

The four other interviews were conducted with stakeholders (a journalist, a mental health nurse, a program manager and a divisional head of one of Ghana’s drug regulatory bodies) who had worked on tackling the problem of tramadol use. These stakeholders were also purposively recruited through a research poster on social media and via personal contacts to better understand Ghana’s policy response to tramadol use. The stakeholders had played keys role in the response to tramadol use in Ghana and provided high-level explanations of how they as individuals and members of institutions understood the problem and the solutions they were advocating to respond to the ‘crisis’.

Participants were recruited across cities (Accra, Tamale, Kumasi and Winneba). Illustrative quotes are labelled according to the location and sequence of interviews: T1-T4 designate Tamale-based interviews; K1-K4 (Kumasi); A1 (Accra), W1-W2 (Winneba), HCP1-3 (Healthcare Professionals), BJ (Broadcast Journalist).

To complete interview data analysis all transcripts were imported into NVivo 12 software and analysed using the six-step process described by Braun and Clark [ 37 ]. This involved: 1) familiarisation—transcripts were read and re-read; 2) generating initial codes—interesting features of each transcript were coded systematically in NVivo; 3) searching for themes—codes were combined into categories and collated into potential themes; 4) reviewing themes—emerging themes were compared to coded extracts; 5) defining and naming themes—themes that told the overall story of the analysis were refined; and 6) producing the report—themes were written up. Emerging findings were discussed with four participants who provided feedback. Research findings are reported drawing on COREQ guidelines ( S1 Checklist ) [ 38 ].

Reflexivity

I approached this study from a critical ontological perspective as a PhD trained health researcher with about 5 years of experience with qualitative methodology. My methodological choices were guided by a commitment to reveal the role of power in shaping vulnerability. I drew on my Ghanaian identity to build ethical and respectful relationships with participants. I recognise that my positionality shapes my framing of the research project and endeavoured during interviews to avoid the use of jargon and to meet participants at a level of equality. I spoke in pidgin and my local language (Dagbani) where necessary and adhered to key principles of relational ethics in working with interviewees who used tramadol.

4. Findings and discussion

It is not entirely clear what caused a major spike in media reportage on tramadol use in 2018 as shown in Fig 1 . The first Ghanaian newspaper reports on tramadol emerged from publications about drug seizures in 2012 in Nigeria. One such article noted that truckloads of drugs intercepted in some ports in West Africa had claimed to be from Ghana as part of the Economic Community of West African States’ (ECOWAS) trade liberalisation scheme but “actually originated from China” [ 39 ]. By 2015 several newspapers were regularly publishing articles on tramadol. Some of these articles focused on contracts awarded to companies to provide drugs for the health sector. From this period onwards news reports emerged regularly on tramadol and were often about criminals arrested with tramadol in their possession. The trend continued for a few months and by March 2018, Ghana’s minister of health issued warnings on the dangers of tramadol use. The sections that follow describe how tramadol use was explained and represented by the media vis à vis theoretical literature on youth.

4.1 The condition of ‘youth’ and youth futures

In analysing media sources to understand how stories are framed, one of the most salient characteristics of tramadol stories has been their connection to youth. The seventh most common word found in newspaper stories was ‘youth’, used 539 times although never clearly defined. That notwithstanding, youth—however defined—remains an important category for theoretical reasons and requires particular attention since participants themselves often invoked ideas of youth in explaining why they used tramadol.

The concept of youth, although sometimes used as a biological signifier to refer to people within the age bracket of 18–25 [ 40 ], is a complex sociological category and subject to manipulation. As Bourdieu [ 41 ] argued, across societies definitions of youth are subject to power dynamics and “the frontier between youth and age is something that is fought over in all societies.” This is particularly the case since the concept of youth and its connotations can be manipulated as a means of scapegoating and apportioning blame.

There are several reasons youth is a fertile ground for the study of health in Africa. First, youth are “particularly sensitive to transformations in the economy as their activities, prospects and ambitions are dislocated and redirected” [ 25 ]. In this sense, the lived experiences of youth who use tramadol can act as a barometer for understanding structural changes in society. Second, in the African postcolonial context in particular, youth has come to indicate “being disadvantaged, vulnerable and marginal in the political and economic sense” [ 42 ]. The fact of marginalisation and disadvantage was described by several interview participants, some of whom described intense despair associated with the condition of youth in Ghana. When I asked one of the interviewees about her hopes for the future as a young person in Ghana she responded:

If I talk about the education side, I really do not have hope because there are a lot of graduates home. And then the maximum of salary some of these graduates get is like 1500 cedis [240 USD] a month. How much is your water bill? Light bill everything? (A1).

Despite such stories of gloom, scholars have sought to explore the condition of youth on the continent not simply as hopeless stories of despair but to recognise within these realities of disadvantage and marginalisation “the diversity of experience as well as the agency and creativity of young people as they try to overcome serious everyday challenges” [ 43 ]. In the context of African youth’s continued challenge to governmental and other authorities by seeking to shape their own destinies and create new ‘youthscapes’ [ 44 ] and spaces for self-fashioning [ 45 ], I start by problematising how the issue of tramadol was framed in media discourses as a problem of ‘youth irresponsibility’. Following this, I explore how such framings fed into the sorts of solutions often proposed by the government and the media. I then contrast this discourse with the lived experience of youth who use tramadol many of whom indicated that palpable pain lay at the heart of their drug use. Interpreted in the context of ethnographies of pain, I argue that tramadol is used to respond to physical and non-physical pain.

4.2 Tramadol consumption as individual moral failure among youth

The primary mode of explanation employed by the media to make sense of the rise in tramadol consumption has been that it is abused because of individual moral failings. Several newspaper stories offered a plethora of explanations on why youth may abuse tramadol ranging from senior high school athletes who have “resorted to the abuse of the drug, claiming it enhances their performance” ( All Africa 4.7.2017) [ 46 ] to multiple media stories explaining that “the youth including students also take the drug to exert their strength when having sexual intercourse with their partners while others take it just for pleasure” ( Ghana News Agency 30.11.2017) [ 47 ].

In these morally tinged discourses, the media highlighted that people “knowingly used the drug for recreational and aphrodisiac purposes” ( Ghana News Agency 8.3.2018) [ 48 ]. These discourses were meant to galvanise societal hatred for tramadol users and therefore relied on ideas of promiscuity that would offend the social sense of morality. For example, in an article on drug confiscation in the Ashanti region, an official of the Food and Drugs Authority asserted that “some of the reasons for the abuse of the drug included supposed enhancement of sexual drive and prolonged ejaculation” ( Ghana News Agency 12.4.2018) [ 49 ]. While it might be the case that some people use tramadol for sexual enhancement [ 17 ], there was an overemphasis on this dimension. Indeed, most stories were focused either on connecting tramadol to sex or crime. Almost half of the news stories reviewed were about crime and arrests of young people with the drug in their possession. Interestingly, none of the interviewees in this research reported being arrested. Despite the overemphasis on sex, I found through interviews that few people use tramadol solely for sexual reasons (only one interviewee mentioned sex as an important reason for his use of tramadol).

Additionally, a neo-traditionalist discourse was invoked to explain tramadol use as a function of moral weakness. There were references by chiefs, queen mothers, religious leaders and opinion leaders who regularly emphasised “the beauty of innocence” and highlighted the necessity for “cultural learning that instils morals, values and norms in the children” as solutions to the tramadol challenge ( Ghana News Agency 24.11.2018) [ 50 ]. According to these authorities, use was on the rise because parents failed to instil morals in their children. The moral discourse often involved the older generation decrying falling moral standards in the country and was so entrenched that even some academic sources relied on this framing as exemplified in Elliason and colleagues [ 14 ] who concluded that “the moral upbringing of the youth” is responsible for the tramadol trend.

It is important to state these discourses explicitly because they heavily shaped what were perceived as the solutions to the problem of tramadol use: education or punishment. By framing it as a problem of youth who simply were morally corrupt, authorities often advocated for campaigns to “educate the youth” on the dangers of consumption and the moral imperative to avoid abusing the drug. Regulatory authorities “appealed to parents to advise their children to desist from the use of the drug since it is destroying a greater number of them” ( Daily Guide 3.8.2017) [ 51 ]. When such persuasion failed to yield the desired results a sort of ‘war on drugs’ approach was adopted. The health minister issued an executive instrument on 26 September 2018 (EI 168) banning the sale of tramadol. The instrument also made 250 mg doses illegal although stores could still sell 50 or 100 mg doses. Finally, it was converted to a prescription drug and several newspapers reported on police swoops to arrest youth who continued to use tramadol. Unfortunately, these ‘solutions’ often failed to target some of the underlying root causes of use and most of them also failed to adopt sustainable approaches. For example, during interviews drug regulators indicated that for youth who may have become addicted to tramadol appropriate solutions would have been to offer them access to rehabilitation centres. According to one regulator however these more long-term approaches were not favoured by government. The reason such solutions received less attention is summarised by a mental health nurse who described Ghana’s mental health system inadequacies:

[In Ghana] mental health itself has been relegated to the background to the extent that even the practitioners are stigmatised… How many traditional government facilities do we have in terms of hospitals that respond to the needs of the mentally ill? Only three in the whole country. And two of them are located down south here, Ankaful and Pantang (HCP 3)

Thus, throughout the discussions on tramadol as a problem of youth irresponsibility, authorities failed to understand why the youth use tramadol or to focus on youth-informed structural solutions to tramadol use. In this sense the moralising discourses that have been adopted by the government and other stakeholders have served to obscure the fact that mental health and addiction services are woefully inadequate in the country.

Famous Ghanaian cartoonist, Tilapia, satirically depicted some of the main supposed motivations for tramadol use; namely sex (a woman runs away from a rather virile young man) and feeling ‘high’ ( Fig 2 ). Tilapia also satirically showed how drug store owners laughed through it all as they made money (for example, although the law illegalised 250 mg, users could simply buy multiple 50 mgs to get the same ‘high’). (See: Tilapia, 2018)

Cartoon by Ghanian artist Tilapia da Cartoonist, April 2018. Reproduced with permission from Tilapia da Cartoonist.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001045.g002

4.3 Pain as a fundamental reason for tramadol use

The discourses above represent some of the ways the Ghanaian news media have understood and reported on the issue of tramadol use. The reports unfortunately paid less attention to the issue of pain which is problematic since a complex set of factors beyond individual choice often determine drug use and addiction [ 22 ]. More importantly discourses that marginalise those who use drugs deserve to be critically assessed because “targeting particular groups of drug users commonly reflect points of social apprehension and serve to enhance the social control and exploitation of subordinated ethnic, class, gender, or other groups characterised as a threat to the status quo” [ 26 ]. In the case of tramadol use in Ghana, this insight suggests that one ought to approach some of the media reports with some scepticism. In the remainder of the article, I argue that a fundamental reason young people in Ghana use tramadol is pain, although other important reasons exist. Using this focus, we can humanise those who use it and appreciate the complex contextual drivers of use beyond moral discourses. Attention to pain also serves as a critique of current policy solutions for eradicating tramadol use.

Pain is a fundamental part of the human condition. It has been of interest to scholars in varied disciplines from philosophy to anthropology because it is a “basic existential fact of our distinctly human way of being-in-the-world. To be human is to be vulnerable to both the possibility and inevitability of suffering pain” [ 52 ]. Understanding, interpreting and describing someone’s pain thus requires attention to the fact that “a person’s experience of pain is multi-dimensional, relating to culture, emotion, mind and body” [ 53 ].