Home — Essay Samples — Business — Comparative Analysis — Comparative Politics Approaches

Comparative Politics Approaches

- Categories: Comparative Analysis

About this sample

Words: 1297 |

Published: Feb 13, 2024

Words: 1297 | Pages: 3 | 7 min read

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Business

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 912 words

4 pages / 1658 words

4 pages / 1991 words

3 pages / 1419 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Comparative Analysis

The dichotomy between liberalism and conservatism has been a defining feature of political discourse for centuries. These two ideologies represent different approaches to governance, societal values, and economic policies. [...]

The study of cultural and rhetorical devices is essential for understanding how communication varies across different societies and contexts. Cultural devices refer to the symbols, norms, and practices that characterize a [...]

The Han Dynasty of China (206 BCE–220 CE) and the Roman Empire (27 BCE–476 CE) were two of the most powerful and influential empires in ancient history. Both empires left an indelible mark on the world through their innovations, [...]

The study of political power and its distribution within society has long been a central theme in political science. Among the myriad of theories that attempt to explain the dynamics of governance and influence, three stand out [...]

For this discussion post I am going to compare and contrast two theories of aging as it relates to the care giver, explain one thing I learned that I didn’t previously know, and state one piece of information that will affect my [...]

What would a story be without setting multiple of emotions in between thrilling moments in a story? In most stories the way the author sets the tone and setting of the story can catch a reader’s attention, especially if it’s [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Comparative Analysis Within Political Science

What Are The Advantages of Comparing Institutions and Political Processes In Two Or More Countries Compared To the Study Of the Same Institutions Or Processes In a Single Country?

This essay will serve as a brief introduction to the practical, conceptual and theoretical values of comparative analysis within political science. Following a brief explanation of the methodology, this essay will explain the importance of its role and the benefits it brings to the political field of research. The essay will also focus on the benefits of comparatively analysing the collating institutions and processes of two or more countries as opposed to one.

Comparative analysis (CA) is a methodology within political science that is often used in the study of political systems, institutions or processes. This can be done across a local, regional, national and international scale. Further, CA is grounded upon empirical evidence gathered from the recording and classification of real-life political phenomena. Where-by other political studies develop policy via ideological and/or theoretical discourse, comparative research aims to develop greater political understanding through a scientifically constrained methodology. Often referred to as one of the three largest subfields of political science, It is a field of study that was referred to as “the greatest intellectual achievement” by Edward A. Freeman (Lijphart, ND).

Using the comparative methodology, the scholar may ask questions of various political concerns, such as the connection, if any, between capitalism and democratization or the collation between federal and unitary states and electoral participation. CA can be employed on either a single country (case) or group of countries. For the study of one country to be considered comparative, it is essential that the findings of the research are referenced into a larger framework which engages in a systematic comparison of analogous phenomena. Subsequent to applying a comparative methodology in the collation or collection of data, established hypothesises can then be tested in an analytical study involving multiple cases (Caramani, 2011).

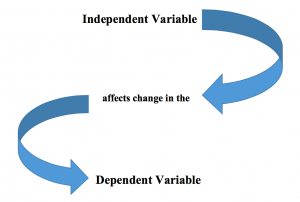

Patterns, similarities and differences are examined to assess the relationships of variants between the two or more separate systems. It is this nature of the analysis that renders it comparative. Henceforth the researcher is subsequently able to isolate the independent variables of each study case. If the independent variables of “X” and “Y” exist, their relationship to dependant variable “Z” can be hypothesised, tested and established (Landman, 2008). This isolation is essential for the most defining and significant strength of CA, that is to establish the hypothetical relationships among variables (Guy, 2011). This empirical analysis can be used to explain a system, present theoretical ideas for modification and even to reasonably predict the future consequence of the case study in question.

While some researchers may favour a large amount of countries for their study (large-N) others will use a smaller amount of units (small-N) (Guy, 1988). The size of the case study is directly collated with the subject and it must lend the study sufficient statistical power. The researcher decides whether it is most appropriate to study one or more units for comparison and whether to use quantitative or qualitative research methods (Guy, 1988). The methodology of utilising multiple countries when analysing is the closet replication of the experimental method used in natural science (Lim, 2010). A clear strength of this method is the inclusion of the ability to implement statistical controls to deduct rival explanations, its ability to make strong inferences that hold for more cases, and its ability to classify ‘deviant’ countries that contradict the outcomes expected from the theory being tested (Guy, 2011).

Deviant countries or cases are units which appear to be exceptions to the norm of the theory being analysed. They are most prevalent in studies of processes and institutions involving only one country. This is due to the fact that there is often a severely limited amount of variability being tested (Lim, 2010). In testing for the relationship between income inequality and political violence in sixty countries, Muller and Seligson identified which countries collated with their theory and which did not. Brazil, Panama, and Gabon were found to have a lower level of political violence than was expected for their national level of income inequality. Alternatively, with a low national level of income inequality, the UK was shown to have a higher than expected amount of political violence (Harro and Hauge, 2003). This identification of these ‘deviant’, cases allowed researchers to look for the explanations. They were able to deduct them from their analysis and increase the accuracy of their predictions for the other cases. This could not have been achieved in a single-country study and would have inevitably left the findings unbalanced and inaccurate.

Selection bias is a reductive practice that is most common with single-country studies. It arises through the deliberate prejudice of countries chosen for examination. The most damaging form of selection bias to the validity of the research is when only case(s) that support the theory being hypothesised are analysed. The serious problem of selection bias occurs much less frequently in studies that contain multiple countries (Lim, 2010). This is because Studies that compare institutions and processes in multiple countries often rely on a sufficient number of observations that reduce the problem or at least its effects of selection bias. Using multiple countries reduces the risk of this invalidity causing phenomena.

However, the research of a single country is clearly valuable; it can produce an insightful exploration of many domestic institutions such as social healthcare, and also processes such as immigration. The findings however are mostly applicable to the country of analysis. Whereas the findings of multi-national CA are also domestically valuable, they also tend to be more inherently valuable to the wider international field. This is because the comparisons of multi-national institutions and processes that are functionally collated have an increased global validity and transferability than the findings of comparison of a single nation (Keman, 2011). The comparative results of a single nation must be hypothesised with other understandings and predications relying substantially on theoretical observations, assumptions and past studies. Inevitably, studying more than one country lends the study a greater field of which to analyse. It is by the CA of subjects from multiple countries that thematic maps can be developed, national, regional and global trends can be identified, and transnational organisations can make acutely informed decisions. These practical benefits are not possible when analysing a phenomenon from one country without cross-case comparison. Analysing multiple cross-national units also furthers our understanding of the similarities, differences and relationships between the case study itself, and the geo-political, economic, and socio-cultural factors that would otherwise escape unaccounted.

The popularity of comparative method of analysing two or more countries has steadily increased (Landman, 2008). Indeed it can be regarded as essential to the understanding and development of modern day political, and international relation’s theory. With the constant dissolvent of countries around the world such as Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia combined with the potential for the creation of new states such as Palestine; the CA which involves different countries offers a wealth of information and most importantly, prediction for their futures. This theoretical framework for prediction is invaluable to society.

Alternatively analysis applied to a single-nation case is less applicable on a global scale (Lim, 2010). For example; studying the process of democratization in one Latin American country, although it offers important inferences that can be examined in other countries with a similar set of circumstances, is arguably insufficient to develop a theory of democratization itself that would be globally applicable. Quite simply, the singular analysis of an institution or process involving only one country often fails to provide a global set of inferences to accurately theorise a process (Harro and Hauge, 2003).

Comparing and contrasting processes and institutions of two or more countries allows the isolation of specific national variants (Hopkin, 2010). It also encourages the clear revealing of common similarities, trends and causation and the deduction of false causation. This means that established hypothesis are continually ripe for revaluation and modification. It enables the researcher to minimise the reductive phenomenon of having ‘too many variables not enough countries’, this occurs when the researcher is unable to isolate the dependant variable of the study because there are too many potential variables (Harro and Hauge, 2003). This problem is far more associated with single-country studies because it results from a surplus of potential explanatory factors combined with an insufficient amount of countries or cases in the study (Harro and Hauge, 2003).

Studies involving multiple countries assists in the defining of results as being idiographic in nature or nomothetic (Franzese, 2007). It also assists in making the important distinction between causation, positive correlation, negative correlation and non-correlation. When analysing only one case or country it is harder to correctly make a distinction between these relationships especially one that is not only subject to the one country.

It is by studying institutions and processes of different countries by use of an empirical methodological framework, that the researcher is able to realise inferences without the ambiguity of generalisations. The separation of the cases being compared offers the researcher a richer study ground of variables that assist in acutely testing hypothesises and in the creation of others. It is through CA that correlating, dependent and independent relationships can be identified (Lim, 2010). The inclusion of multiple countries in a study lends the findings wider validity (Keman, 2011). For example, Gurr demonstrated that the amounts of civil unrest in 114 countries are directly related to the existence of economic and political deprivation. This theory holds true for a majority of countries that it is tested with (Keman, 2011).

It should also be noted that all countries, to differing degrees, are functioning in an interdependent globalized environment. Because of immigration, economic and political interdependence, the study of an institutions and/or processes within a single country inevitably gives a reduction in the transferability of the findings. This is because the findings at least are only as applicably transferable as their counterparts are functionally equivalent. It also somewhat fails to account for transnational trends (Franzese, 2007). Alternatively, comparison involving multiple nations, especially using quantitative techniques, can offer valuable empirically-based geopolitical and domestic generalizations. These assist in the evolution of our understanding of political phenomena and produce great recommendations into how to continue particular research using the same form of analysis or a different method all together.

The study of processes and institutions within two or more countries has been criticised for producing less in-depth information compared to studies involving one country (Franzese, 2007). While this is appears to be a substantial criticism; there is not always agreement between scholars that this trade-off between quantity and quality is substantial, or indeed extremely relevant. Robert Franzese claims that the relative loss of detail which results from analysing large amounts of cross-national cases, does not justify retreating to qualitative study of a few cases (Franzese, 2007). This is because most generalizations from single-country studies will inevitably be limited, since the country as a unit is bound by unique internal characteristics.

It is clear that both single-nation and multinational studies play an important role in CA. Yet as evidenced above, the strengths of encompassing multiple countries into comparative research far outweigh any reduction in the quality of the findings. Indeed, multinational studies work to reduce selection bias, and encourage global transferability, assists in variable deduction and receive recognition as being empirically scientific.

Bibliography

Caramani, D. (2011) Introduction to Comparative Politics. In: Daniele Caramani (ed)’ Comparative Politics’. 2nd edition. London, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1-19

Culpepper, P. (2002 ) ’Single Country Studies and Comparative Politics’ Cambridge Massachusetts, Harvard University press.

Franzese, R. (2007) ‘Multicausality, Context-Conditionally, and Endogeneity’ In: Carels Boix and Susan Stokes. ed(s) ‘The Oxford Handbook of Political Science’. Oxford University Press: New York. pp29-72

Guy, P. (1988) ‘The Importance of Comparison’. In: ‘ Comparative Politics Theory and Methods.’ Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 2-27

Guy, P. (2011) ‘Approaches in Comparative Politics’. In: Daniele Caramani (ed) ‘ Comparative Politics ’.2nd edition. London, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp37-49

Harrop, M. and Hauge, R. (2003) ‘ The Comparative Approach’ . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Hopkin, J. (2010) ‘The Comparative Method’. In: David Marsh & Gerry Stoker .ed(s)‘ Theory and Methods in Political Science’ . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 285-307

Keman, H. (2011) ‘Comparative Research Methods’ . In Daniele Caramani (ed) ‘Comparative Politics’. 2 nd edition. London , Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.50-63

Landman, T. (2008) ‘Why Compare Countries?’.In: ‘ Issues and Methods in Comparative Politics: An Introduction .’ 3rd ed. London: Routledge, pp. 3-22

Lijhart, A. (ND) ‘ Comparative Politics and the Comparative Model’. In: ‘The American Political Science Review ’ . Vol 65, No 3. New York: American Political Science Association, pp. 682-693

Lim, T. (2010) ’ Doing Comparative Politics: An Introduction to Approaches and Issues’ . 2 nd edition. London: Lynne Rienner

— Written by: Alexander Stafford Written at: Queen’s University of Belfast Written for: Dr Elodie Fabre Date written: February 2013

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The European Quality of Government Index: A Critical Analysis

- The Battle of Austerlitz and the Utility of Game Theory for Operational Analysis

- Globalisation, Agency, Theory: A Critical Analysis of Marxism in Light of Brexit

- Between Pepe and Beyoncé: The Role of Popular Culture in Political Research

- Queer Asylum Seekers as a Threat to the State: An Analysis of UK Border Controls

- Offensive Realism and the Rise of China: A Useful Framework for Analysis?

Please Consider Donating

Before you download your free e-book, please consider donating to support open access publishing.

E-IR is an independent non-profit publisher run by an all volunteer team. Your donations allow us to invest in new open access titles and pay our bandwidth bills to ensure we keep our existing titles free to view. Any amount, in any currency, is appreciated. Many thanks!

Donations are voluntary and not required to download the e-book - your link to download is below.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

27 Overview of Comparative Politics

Carles Boix is the Robert Garrett Professor of Politics and Public Affairs at Princeton University and the Director of the Institutions and Political Economy Research Group at the University of Barcelona.

Susan Stokes is a John S. Saden Professor of Political Science and director of the Yale Program on Democracy. Her research has been supported by the National Science Foundation, the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, the American Philosophical Society, and the Russell Sage Foundation.

- Published: 05 September 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article discusses several crucial questions that comparative political scientists address. These questions also form part of the basis of the current volume. The article first studies the theory and methods used in gathering data and evidence, and then focuses on the concepts of states, state formation, and political consent. Political regimes, political conflict, mass political mobilization, and political instability are other topics examined in this article. The latter portion of the article is devoted to determining how political demands are processed and viewing governance using a comparative perspective.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 148 |

| November 2022 | 91 |

| December 2022 | 47 |

| January 2023 | 34 |

| February 2023 | 29 |

| March 2023 | 18 |

| April 2023 | 26 |

| May 2023 | 30 |

| June 2023 | 7 |

| July 2023 | 32 |

| August 2023 | 34 |

| September 2023 | 80 |

| October 2023 | 122 |

| November 2023 | 82 |

| December 2023 | 41 |

| January 2024 | 43 |

| February 2024 | 35 |

| March 2024 | 27 |

| April 2024 | 22 |

| May 2024 | 28 |

| June 2024 | 21 |

| July 2024 | 29 |

| August 2024 | 27 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Help and information

- Comparative Politics

- Environmental Politics

- European Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Human Rights and Politics

- International Political Economy

- International Relations

- Introduction to Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Philosophy

- Political Theory

- Politics of Development

- Security Studies

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Politics (1st edn)

- Acknowledgements

- List of Boxes

- List of Tables

- About the authors

- How to Use This Book

- How to Use the Online Resources

- 1. Introduction: The Nature of Politics and Political Analysis

- 2. Politics and the State

- 3. Political Power, Authority, and the State

- 4. Democracy

- 5. Democracies, Democratization, and Authoritarian Regimes

- 6. Nations and Nationalism

- 7. The Ideal State

- 8. Ideologies

- 9. Political Economy: National and Global Perspectives

- 10. Institutions and States

- 11. Laws, Constitutions, and Federalism

- 12. Votes, Elections, Legislatures, and Legislators

- 13. Political Parties

- 14. Executives, Bureaucracies, Policy Studies, and Governance

- 15. Media and Politics

- 16. Civil Society, Interest Groups, and Populism

- 17. Security Insecurity, and the State

- 18. Governance and Organizations in Global Politics

- 19. Conclusion: Politics in the Age of Globalization

p. 1 1. Introduction: The Nature of Politics and Political Analysis

- Peter Ferdinand , Peter Ferdinand Emeritus Reader in Politics and International Studies, University of Warwick

- Robert Garner Robert Garner Professor of Politics, University of Leicester

- and Stephanie Lawson Stephanie Lawson Professor of Politics and International Studies, Macquarie University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/hepl/9780198787983.003.0001

- Published in print: 12 April 2018

- Published online: August 2018

This chapter discusses the nature of politics and political analysis. It first defines the nature of politics and explains what constitutes ‘the political’ before asking whether politics is an inevitable feature of all human societies. It then considers the boundary problems inherent in analysing the political and whether politics should be defined in narrow terms, in the context of the state, or whether it is better defined more broadly by encompassing other social institutions. It also addresses the question of whether politics involves consensus among communities, rather than violent conflict and war. The chapter goes on to describe empirical, normative, and semantic forms of political analysis as well as the deductive and inductive methods of the study of politics. Finally, it examines whether politics can be a science.

- political analysis

- empirical analysis

- normative analysis

- semantic analysis

- deductive method

- inductive method

You do not currently have access to this chapter

Please sign in to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Politics Trove. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 07 September 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [81.177.182.159]

- 81.177.182.159

Characters remaining 500 /500

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 Chapter 8: Comparative Politics

Comparative politics centers its inquiry into politics around a method, not a particular object of study. This makes it unique since all the other subfields are orientated around a subject or focus of study. The comparative method is one of four main methodological approaches in the sciences (the others being statistical method, experimental method, and case study method). The method involves analyzing the relationship between variables that are different or similar to one another. Comparative politics commonly uses this comparative method on two or more countries and evaluating a specific variable across these countries, such as a political structure, institution, behavior, or policy. For example, you may be interested in what form of representative democracy best brings about consensus in government. You may compare majoritarian and proportional representation systems, such as the United States and Sweden, and evaluate the degree to which consensus develops in these governments. Conversely, you may take two proportional systems, such as Sweden and the United Kingdom, and evaluate whether there is any difference in consensus-building among similar forms of representative government. Although comparative politics often makes comparisons across countries, it can also conduct comparative analysis within one country, looking at different governments or political phenomena through time.

The comparative method is important to political science because the other main scientific methodologies are more difficult to employ. Experiments are very difficult to conduct in political science—there simply is not the level of recurrence and exactitude in politics as there is in the natural world. The statistical method is used more often in political science but requires mathematical manipulation of quantitative data over a large number of cases. The higher the number of cases (the letter N is used to denote number of cases), the stronger your inferences from the data. For a smaller number of cases, like countries, of which there is a limited number, the comparative method may be superior to statistical methodology. In short, the comparative method is useful to the study of politics in smaller cases that require comparative analysis between variables.

Most Similar Systems Design (MSSD)

This strategy is predicated on comparing very similar cases which differ in their dependent variable. In other words, two systems or processes are producing very different outcomes—why? The assumption here is that comparing similar cases that bring about different outcomes will make it easier for the researcher to control factors that are not the causal agent and isolate the independent variable that explains the presence or absence of the dependent variable. A benefit of this strategy is that it keeps confusing or irrelevant variables out of the mix by identifying two similar cases at the outset. Two similar cases implied a number of control variables—elements that make the cases similar—and very few elements that are dissimilar. Among those dissimilar elements is likely your independent variable that produced the presence/absence of your dependent variable. A downside to this approach is that when comparing across countries, it can be difficult to find similar cases due to a limited number of them. There can be a more strict or loose application of the MSSD model—similarities may be fairly exact or roughly the same, depending on the characteristic involved, and will influence your research project accordingly.

Example 8.1

Suppose you want to study how well forms of representative government develop consensus and agreement over policy matters. You may observe that nearly identical representative systems of government exist in County A and Country B, but are producing very different results.

- Country A has a proportional representation system and has a long and successful track record of producing consensus among lawmakers over a number of policy issues.

- Country B, however, is riddled with partisan disagreement and a lack of consensus over a similar kind and number of policy issues.

In this instance, you may also observe a number of similarities that act as control variables in your research—both countries have a bicameral legislature, a similar number of representatives per capita. This is a research project well suited to the MSSD approach, as it allows multiple control points (proportional representation, bicameral legislature, number of representatives, etc.) and allows for the researcher to focus on fine grain points of difference among the cases. You may observe in this example one intriguing difference in demographics—County A’s population is smaller and largely homogenous, whereas Country B’s population is larger and more diverse. It may be that in Country B this diverse population is well represented in the legislature but leads to more policy disputes and a relative lack of consensus when compared to Country A.

Most Different Systems Design (MDSD)

This strategy is predicated on comparing very different cases that are all have the same dependent variable. This strategy allows the research to identify a point of similarity between otherwise different cases and thus identify the independent variable that is causing the outcome. In other words, the cases we observe may have very different variables between them yet we can identify the same outcome happening—why do we have different systems producing the same outcome? The task is to then sift through the variables existing between the cases and isolate those that are in fact similar, since a similar variable between the cases may in fact be the causal agent that is producing the same outcome. An advantage to the MDSD approach is that it doesn’t have as many variables that need to be analyzed as the MSSD approach does—a researcher only needs to identify the same variable that exists across all different cases. The MSSD approach, on the other hand, tends to have a lot more variables that have to be considered although it may provide a more precise link between the independent and dependent variables.

Example 8.2

Let’s use an example that will help illustrate the MDSD approach. Suppose you observe two very different forms of representative government producing the same outcome: Country A has a majoritarian, winner-take-all representational system and Country B has a proportional representation system, yet in both countries there is a high degree of efficiency and consensus in the legislative process.

Why do two systems have the same outcome?

You may list a number of variables and compare them across the two cases, sifting through to locate similar variables. Unlike the MSSD approach, which seeks to locate different variables across similar cases, the MDSD approach is the opposite—the task is to locate similar variables across different cases. You may observe that despite the fact that these two countries have very different systems of representation, both have unicameral legislatures and a low number of representatives per capita. These factors may produce higher levels of efficiency and consensus in the legislative process, thus explaining the same dependent variable despite different cases.

The Nation-State

Much of comparative politics focuses on comparisons across countries, so it is necessary to examine the basic unit of comparative politics research—the nation-state.

A nation is a group of people bound together by a similar culture, language, and common descent, whereas a state is a political sovereign entity with geographic boundaries and a system of government. A nation-state, in an ideal sense, is when the boundaries of a national community are the same as the boundaries of a political entity. In this sense, we may say that a nation-state is a country in which the majority of its citizens share the same culture and reflect this shared identity in a sovereign political entity located somewhere in the world. Nation-states are therefore countries with a predominant ethnic group that articulates a culturally and politically shared identity. As should be apparent, this definition has some gray areas—culture is fluid and changes over time; migration patterns can change the make up of a nation-state and thus influence cultural and political changes; minority populations may substantially contribute to the characteristics that make up a shared national identity, and so on.

Nations may include a diaspora or population of people that live outside the nation-state. Some nations do not have states. The Kurdish nation is an example of a distinct ethnic group that lacks a state—the Kurds live in a region that straddles the borders of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran. Some other examples of nations without states include the numerous indigenous nations of the Americas, the Catalan and Basque nations in Spain, the Palestinian people in the Middle East, the Tibetan and Uyghur people in China, the Yoruba people of West Africa, and the Assamese people in India. Some previously stateless nations have since attained statehood—the former Yugoslav republics, East Timor, and South Sudan are somewhat recent examples. Not all stateless nations seek their own state, but many if not most have some kind of movement for greater autonomy if not independence. Some autonomous of breakaway regions are nations that have by force exercised autonomy from another country that claims that region. There are many such regions in the former Soviet Union: Abkhazia and South Ossetia (breakaway regions from Georgia), Transdniestria (breakaway region from Moldovia), Nagorno-Karabagh (breakaway region from Azerbaijan), and the recent self-declared autonomous provinces of Luhansk and Donetsk in the Ukraine. Most of these movements for autonomy are actively supported by Russia in an effort to control their sphere of influence. Abkhazians, South Ossetians, Trandniestrians, and residents of Luhansk and Donetsk can apply for Russian passports.

Lastly, some countries are not nation-states either because they do not possess a predominate ethnic majority or have structured a political system of more devolved power for semi-autonomous or autonomous regions. Belgium, for example, is a federal constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system with three highly autonomous regions: Flanders, Wallonia, and the Brussels capital region. The European Union is an interesting case of a supra-national political union of 28 states with a standardized system of laws and an internal single economic market. An outgrowth of economic agreements among Western European countries in the 1950s, the EU is today one of the largest single markets in the world and accounts for roughly a quarter of the global economic output. In addition to a parliament, the EU government, located in Brussels, Belgium, has a commission to execute laws, a courts system, and two councils, one for national ministers of the member states and the other for heads of state or government of the member states. The EU’s complicated political system allows for varying and overlapping levels of legal and political authority. Some member states have anti-EU movements in their countries that broadly share a concern over a loss of political and cultural autonomy in their country. The United Kingdom’s decision to leave the EU, known as “Brexit,” has been a complex and controversial process.

As this brief overview suggests, the concept of a nation-state is central to global politics. Crucial questions on what constitutes a nation-state underpin many of the most significant political conflicts in the world. Autonomous movements that seek greater sovereignty for a particular nation are found in every region of the world. At the heart of the relationship between nations and states is the idea of self-determination—that distinct cultural groups should be able to define their own political and economic destiny. Self-determination as a conception of justice suggests that freedom is not just individual but also communal—the freedom of defined groups to autonomy and self-direction.

Self-determination as a conception of justice suggests that freedom is not just individual but also communal—the freedom of defined groups to autonomy and self-direction.

The push and pull of power that brings nations together or tears them apart is everywhere in global politics. Moreover, states may appear stronger than they actually are, as the unexpected fall of the Soviet Union suggests. The legitimacy of the state and the cohesiveness of a nation go a long way toward understanding stability in the global world.

Comparing Constitutional Structures and Institutions

In Chapter Four we provided an overview of constitutions as a blueprints for political systems and in Chapter Three’s focus on political institutions we discussed legislative, executive, and judicial units and powers such as unicameral or bicameral legislatures, presidential systems, judicial review, and so on. The relationship between similar and different institutional forms make up the nuts and bolts of comparative political inquiry. In comparing constitutions across countries, each constitution speaks to the unique characteristics of a political community but there are also similarities. Constitutions typically outline the nature of political leadership, structure a form of political representation, provide for some form of executive authority, define a legal system for adjudicating law, and authorize and limit the reach of government power. On the other hand, there are several unique factors that determine a constitution an government. Geography, for example, often has a profound impact on the constitutional structure and form of government.

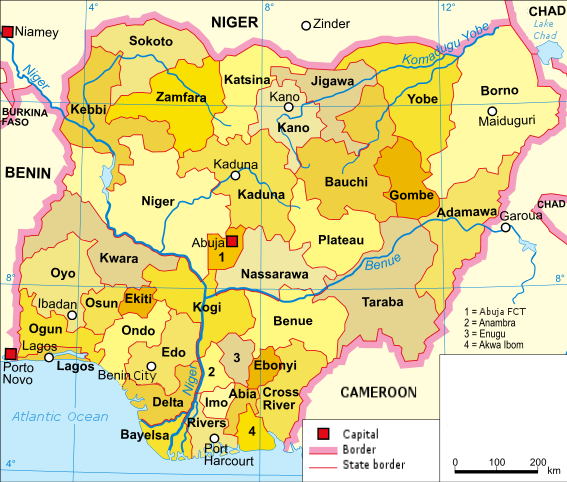

Large countries with scattered populations, for example, must be more sensitive to the legitimacy of the state in regions far removed from the center of government power. Some governments have moved their seat of power to more centralized and less populous cities in response to this concern—Abuja, Nigeria, Canberra, Australia, Dodoma, Tanzania, Yamoussoukro, Côte d’Ivoire, Brasilia, Brazil and Washington DC in the United States are examples of capital cities founded as a more central location in order to better balance power among competing regions.

Another factor is social stratification—differentiation in society based on wealth and status. What is typically regarded as lower, middle, and upper classes in most developed societies, social stratification can be complex, overlapping, and influenced by a variety of group characteristics such as race or ethnicity and gender. Social stratification can lead to political stratification—differing levels of access, representation, influence, and control of political power in government. This derived power can in turn reinforce social stratification in various ways. For example, the wealthy and privileged of a country may have derived political power from their wealth and in turn shape and influence government in such a way as to protect and increase their wealth, influence, and privilege. With the comparative method of political inquiry, political scientists can study the degrees to which social stratification effects political processes across countries. This kind of comparative inquiry can yield important insights such as whether wealth derived from group characteristics leads to greater political stratification than wealth derived across more diverse groups, or whether reforms directed at lessening political stratification have any effect on social stratification.

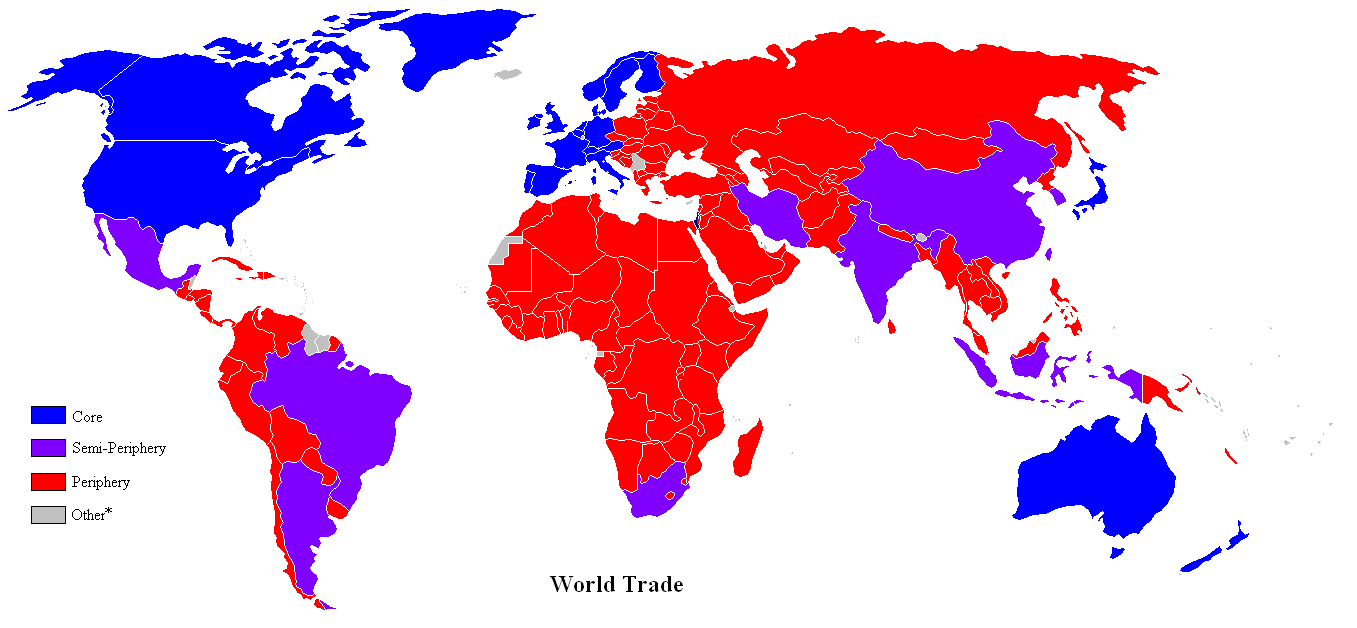

Lastly, global stratification suggests when looking at the global system, there is an unequal distribution of capital and resources such that countries with less powerful economies are dependent on countries with more powerful economies. Three broad classes define this global stratification: core countries, semi-peripheral countries, and peripheral countries. Core countries are highly industrialized and both control and benefit from the global economic market. Their relationship to peripheral countries is typically predicated on resource extraction—core countries may trade or may seek to outright control natural resources in the peripheral countries. Take as an example two open pit uranium mines located near Arlit in the African country of Niger. Niger, one of the poorest countries in the world, was a former colony of France. These mines were developed by French corporations, with substantial backing from the French government, in the early 1970s. French corporations continue to own, process, and transport uranium from the Arlit mines. The vast majority of the uranium needed for French nuclear power reactors and the French nuclear weapons program comes from Arlit. The mines have completely transformed Niger in a number of ways. 90% of the value of Niger’s exports come from uranium extraction and processing, leading to what some economists call a “resource curse”—a situation in which an economy is dominated by a single natural resource, hampering the diversification of the economy, industrialization, and the development of a highly skilled workforce.

Semi-periphery countries have intermediate levels of industrialization and development with a particular focus on manufacturing and service industries. Core countries rely on semi-peripheral countries to provide low cost services, making the economies of core and semi-peripheral countries well integrated with one another, but also creating an economic situation in which semi-peripheral countries become increasingly dependent on consumption in core countries and the global economy generally, sometimes at the expense of more economic self-sufficient and sustainable development. As an example, let’s consider Malaysia, a newly industrialized Asian country of over 40 million people. Malaysia has had a GDP growth rate of over 5% for 50 years. Previously a resource extraction economy, Malaysia went through rapid industrialization and is currently a major manufacturing economy, and is one of the world’s largest exporters of semi-conductors, IT and communication equipment, and electrical devices. It is also the home country of the Karex corporation, the world’s biggest producer of condoms.

Included among core countries are the United States and Canada, Western Europe and the Nordic countries, Australia, Japan, and South Korea. Semi-peripheral countries include China, India, Russia, Iran, Malaysia, Indonesia, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and South Africa. Periphery countries include most of Africa, the Middle East, Central America, Eastern Europe, and several Asian countries. Reflect on the relationship between core, semi-peripheral, and peripheral countries. Do you think this relationship is predicated more on exploitation and control or mutually beneficial economic partnerships in a global environment? Choose three countries—one core, one semi-peripheral, and one peripheral—that have political and economic ties to one another. Evaluate and analyze relations between these countries. What are the prominent economic interactions? What best characterizes the diplomacy and political relations between these countries? Are the forms of government similar or different?

The Value of Languages and Comprehensive Knowledge

Comparative politics arguably requires more comprehensive knowledge of countries, political systems, cultures, and languages than the other sub-disciplines in political science. Language skill, in particular, is often essential for the comparativist to conduct good research. Having some facility with languages spoken in the countries or regions central to the research project gives researcher access to information and opens up avenues of communication and knowledge that is needed for in-depth understanding.

In conducting field research, knowledge of local languages is critically important. Conducting interviews and doing observations in the field require familiarity with common languages spoken in the area. Grants are available from the US State Department and academic institutions for graduate students (and in some cases promising undergraduates) for language programs. The best environment for learning a foreign language is immersive—ideally, students should spend time in areas they have research interests in to gain familiarity with the language(s) and cultural practices. For example, if one wanted to conduct a comparative research project on political development in Kosovo and Abkhazia—two breakaway autonomous republics of similar size and population that are key sites of the geopolitical struggle between the West and Russia—it would be necessary to have some familiarity with Albanian (the dominant language of Kosovo) and Abkhaz, but it may also be helpful to have some exposure to Serbian, Russian, and Georgian as well.

Comparativists should ideally have broad but deep knowledge of the world—understanding regional issues, environmental resources, demographics, and relations between countries provides a pool of general knowledge that can help comparativists avoid obstacles while conducting their research. For example, if one were conducting a study on the relationship between women’s access to contraceptives and the percent of women in the workforce with a data set of some 150 countries, it is useful to know that in the non-Magreb countries of Africa women make up a disproportionately large percentage of agricultural labor. Despite low access to contraceptives, sub-Saharan African countries have relatively high percentages of women in the work force due to the cross-cultural norm of women farmers.

Field Research in Comparative Politics

A crucial component of doing comparative politics is field research—the collection of data or information in the relevant areas of your research focus. Where political theory is akin to the discipline of philosophy, comparative politics is akin to anthropology in this field research component. Comparativists are encouraged to “leave the office” and bring their research out into the relevant areas in the world. Being on the ground affords the researcher a firsthand perspective and access to the sources that underpin good comparative analysis. Conducting surveys with local respondents, doing interviews with key actors in and out of government, and making participant observations are some common methods of gathering evidence for the field researcher. To continue with the above example of Kosovo and Abkhazia, suppose a researcher was interested in comparing constitutional development and reform in the two republics. Interviews with key actors in developing those respective constitutions would provide a firsthand account of the process, while surveys conducted with local responses could measure the degree of support for key reforms. A researcher could also conduct participant observations of the legislative process, media events, or council meetings.

Being in the field always comes with surprises that may alter the research project in numerous ways. Poor infrastructure may hamper travel. Corruption may create obstacles in survey work or interviews. Locals may be unwilling to work with a foreign researcher whose intentions are in doubt. It is always important to balance your ideal research project with the practical realities you find on the ground. Deciding whether to take a short or long trip abroad is also an important consideration—shorter trips may bring more focus and efficiency to your work and also afford more opportunity to identify points of comparison and contrast, whereas longer trips can be more open-ended and immersive, giving the researcher the opportunity to develop contacts and and have a more in-depth cultural experience. Lastly, case selection and sampling are important considerations—macro-level case selection involves identifying a country to conduct field work; meso-level selection involves locating relevant regions or towns; micro-level selection involves identifying individuals to interview or specific documents for content analysis.

Comparative politics is more about a method of political inquiry than a subject matter in politics. The comparative method seeks insight through the evaluation and analysis of two or more cases. There are two main strategies in the comparative method: most similar systems design, in which the cases are similar but the outcome (or dependent variable) is different, and most different systems design, in which the cases are different but the outcome is the same. Both strategies can yield valuable comparative insights. A key unit of comparison is the nation-state, which gives a researcher relatively cohesive cultural and political entities as the basis of comparison. A nation-state is the overlap of a definable cultural identity (a nation) with a political system that reflects and affirms characteristics of that identity (a state).