- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Observatory

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Fact sheets /

- Measles is a highly contagious, serious airborne disease caused by a virus that can lead to severe complications and death.

- Measles vaccination averted 57 million deaths being between 2000 and 2022.

- Even though a safe and cost-effective vaccine is available, in 2022, there were an estimated 136 000 measles deaths globally, mostly among unvaccinated or under vaccinated children under the age of 5 years.

- The proportion of children receiving a first dose of measles vaccine was 83% in 2023, well below the 2019 level of 86%.

Measles is a highly contagious disease caused by a virus. It spreads easily when an infected person breathes, coughs or sneezes. It can cause severe disease, complications, and even death.

Measles can affect anyone but is most common in children.

Measles infects the respiratory tract and then spreads throughout the body. Symptoms include a high fever, cough, runny nose and a rash all over the body.

Being vaccinated is the best way to prevent getting sick with measles or spreading it to other people. The vaccine is safe and helps your body fight off the virus.

Before the introduction of measles vaccine in 1963 and widespread vaccination, major epidemics occurred approximately every two to three years and caused an estimated 2.6 million deaths each year.

An estimated 136 000 people died from measles in 2022 – mostly children under the age of five years, despite the availability of a safe and cost-effective vaccine.

Accelerated immunization activities by countries, WHO, the Measles & Rubella Partnership (formerly the Measles & Rubella Initiative), and other international partners successfully prevented an estimated 57 million deaths between 2000–2022. Vaccination decreased an estimated measles deaths from 761 000 in 2000 to 136 000 in 2022 (1) .

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic led to setbacks in surveillance and immunization efforts. The suspension of immunization services and declines in immunization rates and surveillance across the globe left millions of children vulnerable to preventable diseases like measles.

No country is exempt from measles, and areas with low immunization encourage the virus to circulate, increasing the likelihood of outbreaks and putting all unvaccinated children at risk.

We must regain progress and achieve regional measles elimination targets, despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Immunization programs should be strengthened within primary healthcare, so efforts to reach all children with two measles vaccine doses should be accelerated. Countries should also implement robust surveillance systems to identify and close immunity gaps.

Signs and symptoms

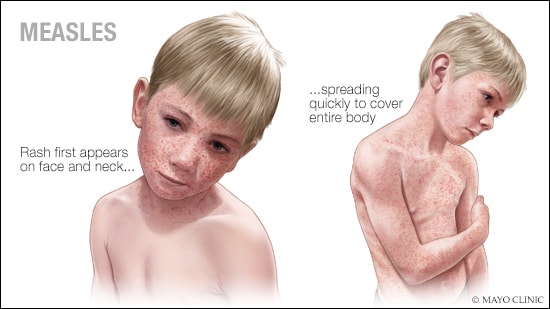

Symptoms of measles usually begin 10–14 days after exposure to the virus. A prominent rash is the most visible symptom.

Early symptoms usually last 4–7 days. They include:

- running nose

- red and watery eyes

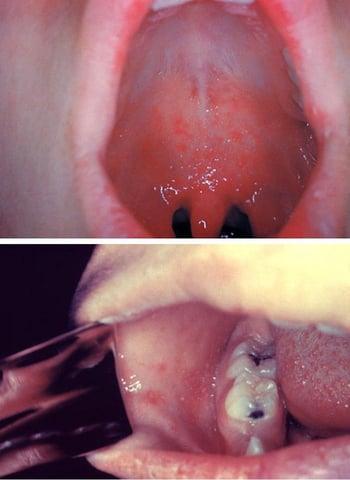

- small white spots inside the cheeks.

The rash begins about 7–18 days after exposure, usually on the face and upper neck. It spreads over about 3 days, eventually to the hands and feet. It usually lasts 5–6 days before fading.

Most deaths from measles are from complications related to the disease.

Complications can include:

- encephalitis (an infection causing brain swelling and potentially brain damage)

- severe diarrhoea and related dehydration

- ear infections

- severe breathing problems including pneumonia.

If a woman catches measles during pregnancy, this can be dangerous for the mother and can result in her baby being born prematurely with a low birth weight.

Complications are most common in children under 5 years and adults over age 30. They are more likely in children who are malnourished, especially those without enough vitamin A or with a weak immune system from HIV or other diseases. Measles itself also weakens the immune system and can make the body “forget” how to protect itself against infections, leaving children extremely vulnerable.

Who is at risk?

Any non-immune person (not vaccinated or vaccinated but did not develop immunity) can become infected. Unvaccinated young children and pregnant persons are at highest risk of severe measles complications.

Measles is still common, particularly in parts of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. The overwhelming majority of measles deaths occur in countries with low per capita incomes or weak health infrastructures that struggle to reach all children with immunization.

Damaged health infrastructure and health services in countries experiencing or recovering from a natural disaster or conflict interrupt routine immunization and overcrowding in residential camps increases the risk of infection. Children with malnutrition or other causes of a weak immune system are at highest risk of death from measles.

Transmission

Measles is one of the world’s most contagious diseases, spread by contact with infected nasal or throat secretions (coughing or sneezing) or breathing the air that was breathed by someone with measles. The virus remains active and contagious in the air or on infected surfaces for up to two hours. For this reason, it is very infectious, and one person infected by measles can infect nine out of 10 of their unvaccinated close contacts. It can be transmitted by an infected person from four days prior to the onset of the rash to four days after the rash erupts.

Measles outbreaks can result in severe complications and deaths, especially among young, malnourished children. In countries close to measles elimination, cases imported from other countries remain an important source of infection.

There is no specific treatment for measles. Caregiving should focus on relieving symptoms, making the person comfortable and preventing complications.

Drinking enough water and treatments for dehydration can replace fluids lost to diarrhoea or vomiting. Eating a healthy diet is also important.

Doctors may use antibiotics to treat pneumonia and ear and eye infections.

All children or adults with measles should receive two doses of vitamin A supplements, given 24 hours apart. This restores low vitamin A levels that occur even in well-nourished children. It can help prevent eye damage and blindness. Vitamin A supplements may also reduce the number of measles deaths.

Community-wide vaccination is the most effective way to prevent measles. All children should be vaccinated against measles. The vaccine is safe, effective and inexpensive.

Children should receive two doses of the vaccine to ensure they are immune. The first dose is usually given at 9 months of age in countries where measles is common and 12–15 months in other countries. A second dose should be given later in childhood, usually at 15–18 months.

The measles vaccine is given alone or often combined with vaccines for mumps, rubella and/or varicella.

Routine measles vaccination, combined with mass immunization campaigns in countries with high case rates are crucial for reducing global measles deaths. The measles vaccine has been in use for about 60 years and costs less than US$ 1 per child. The measles vaccine is also used in emergencies to stop outbreaks from spreading. The risk of measles outbreaks is particularly high amongst refugees, who should be vaccinated as soon as possible.

Combining vaccines slightly increases the cost but allows for shared delivery and administration costs and importantly, adds the benefit of protection against rubella, the most common vaccine preventable infection that can infect babies in the womb.

In 2023, 74% of children received both doses of the measles vaccine, and about 83% of the world's children received one dose of measles vaccine by their first birthday. Two doses of the vaccine are recommended to ensure immunity and prevent outbreaks, as not all children develop immunity from the first dose.

Approximately 22 million infants missed at least one dose of measles vaccine through routine immunization in 2023.

WHO response

In 2020, WHO and global stakeholders endorsed the Immunization Agenda 2021–2030. The Agenda aims to achieve the regional targets as a core indicator of impact, positioning measles as a tracer of a health system’s ability to deliver essential childhood vaccines.

WHO published the Measles and rubella strategic framework in 2020, establishing seven necessary strategic priorities to achieve and sustain the regional measles and rubella elimination goals.

During 2000–2022, supported by the Measles & Rubella Initiative (now the Measles and Rubella Partnership) and Gavi, measles vaccination prevented an estimated 57 million deaths; mostly in the WHO African Region and Gavi-supported countries.

Without sustained attention, hard-fought gains can easily be lost. Where children are unvaccinated, outbreaks occur. Based on current trends of measles vaccination coverage and incidence, the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) concluded that measles elimination is under threat, as the disease resurged in numerous countries that achieved, or were close to achieving, elimination.

WHO continues to strengthen the Global Measles and Rubella Laboratory Network (GMRLN) to ensure timely diagnosis of measles and track the virus’ spread to assist countries in coordinating targeted vaccination activities and reduce deaths from this vaccine-preventable disease.

The IA2030 Measles & Rubella Partnership

The Immunization Agenda 2030 Measles & Rubella Partnership (M&RP) is a partnership led by the American Red Cross, United Nations Foundation, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Gavi, the Vaccines Alliance, the Bill and Melinda French Gates Foundation, UNICEF and WHO, to achieve the IA2030 measles and rubella specific targets. Launched in 2001, as the Measles and Rubella Initiative, the revitalized Partnership is committed to ensuring no child dies from measles or is born with congenital rubella syndrome. The Partnership helps countries plan, fund and measure efforts to permanently stop measles and rubella

1. Minta AA, Ferrari M, Antoni S, et al. Progress Toward Measles Elimination — Worldwide, 2000–2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72:1262–1268. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7246a3

- Measles and rubella strategic framework: 2021-2030

- Measles & Rubella Partnership

- Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals: Measles

- Health topic on measles

(Rubeola; Morbilli; 9-Day Measles)

- Pathophysiology |

- Symptoms and Signs |

- Diagnosis |

- Treatment |

- Prognosis |

- Prevention |

- Key Points |

- More Information |

Measles is a highly contagious viral infection that is most common among children. It is characterized by fever, cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, an enanthem (Koplik spots) on the oral mucosa, and a maculopapular rash that spreads cephalocaudally. Complications, mainly pneumonia or encephalitis, may be fatal, particularly in medically underserved areas. Diagnosis is usually clinical. Treatment is supportive. Vaccination is effective for prevention.

Worldwide, measles infects approximately 10 million people and causes approximately 100,000 to 200,000 deaths each year, primarily in children ( 1 ). These numbers can vary dramatically over a short period of time depending on the vaccination status of the population.

Measles is uncommon in the United States because of routine childhood vaccination, and endemic measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000. An average of 63 cases/year were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from 2000 to 2010.

However, in 2019, incidence in the United States rose to 1274 cases, the highest number reported since 1992. That increase primarily was due to the spread among unvaccinated groups (see the CDC's Measles Cases and Outbreaks ). Parental refusal of vaccination is becoming more frequent as a cause of the increase in vaccine-preventable diseases in children.

In 2020, only 13 measles cases were reported in the United States amid the COVID-19 global pandemic. In 2022, 121 cases were reported (see the CDC's Measles Cases and Outbreaks ).

General reference

1. Patel MK, Goodson JL, Alexander Jr. JP, et al : Progress toward regional measles elimination—worldwide, 2000–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69(45):1700–1705, 2020. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a6

Pathophysiology of Measles

Measles is caused by a paramyxovirus and is a human disease with no known animal reservoir or asymptomatic carrier state. It is extremely communicable; the secondary attack rate is > 90% among susceptible people who are exposed.

Measles is spread mainly by secretions from the nose, throat, and mouth during the prodromal or early eruptive stage. Communicability begins several days before and continues until several days after the rash appears. Measles is not communicable once the rash begins to desquamate.

Transmission is typically by large respiratory droplets that are discharged by cough and briefly remain airborne for a short distance. Transmission may also occur by small aerosolized droplets that can remain airborne (and thus can be inhaled) for up to 2 hours in closed areas (eg, in an office examination room). Transmission by fomites seems less likely than airborne transmission because the measles virus is thought to survive only for a short time on dry surfaces.

An infant whose mother has immunity to measles (eg, because of previous illness or vaccination) receives antibodies transplacentally; these antibodies are protective for most of the first 6 to 12 months of life. Lifelong immunity is conferred by infection.

In the United States, almost all measles cases are imported by travelers or immigrants, with subsequent community transmission occurring primarily among unvaccinated people.

Symptoms and Signs of Measles

After a 7- to 14-day incubation period, measles begins with a prodrome of fever, coryza, hacking cough, and tarsal conjunctivitis. Koplik spots (which resemble grains of white sand surrounded by red areolae) are pathognomonic. These spots appear during the prodrome before the onset of rash, usually on the oral mucosa opposite the 1st and 2nd upper molars. They may be extensive, producing diffuse mottled erythema of the oral mucosa. Sore throat develops.

The rash appears 3 to 5 days after symptom onset, usually 1 to 2 days after Koplik spots appear. It begins on the face in front of and below the ears and on the side of the neck as irregular macules, soon mixed with papules. Within 24 to 48 hours, lesions spread to the trunk and extremities (including the palms and soles) as they begin to fade on the face. Petechiae or ecchymoses may occur with in severe cases.

During peak disease severity, a patient’s temperature may exceed 40 ° C, with periorbital edema, conjunctivitis, photophobia, a hacking cough, extensive rash, prostration, and mild itching. Constitutional symptoms and signs parallel the severity of the eruption.

In 3 to 5 days, the fever decreases, the patient feels more comfortable, and the rash fades rapidly, leaving a coppery brown discoloration followed by desquamation.

Patients who are immunocompromised may not have a rash and can develop severe, progressive giant cell pneumonia.

Complications of measles

Complications of measles include

Bacterial superinfection, including pneumonia

Acute thrombocytopenic purpura

Encephalitis

Transient hepatitis

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis

Bacterial superinfections include pneumonia, laryngotracheobronchitis, and otitis media. Measles transiently suppresses delayed hypersensitivity, which can worsen active tuberculosis and temporarily prevent reaction to tuberculin and histoplasmin antigens in skin tests. Bacterial superinfection is suggested by pertinent focal signs or a relapse of fever, leukocytosis, or prostration.

Pneumonia due to measles virus infection of the lungs occurs in approximately 5% of patients, even during apparently uncomplicated infection. In fatal cases of measles in infants, pneumonia is often the cause of death.

Acute thrombocytopenic purpura may occur after infection resolves and cause a mild, self-limited bleeding tendency; occasionally, bleeding is severe.

Encephalitis occurs in 1/1000 children, usually 2 days to 2 weeks after onset of the rash ( 1 ), often beginning with recrudescence of high fever, headache, seizures, and coma. Cerebrospinal fluid usually has a lymphocyte count of 50 to 500/mcL and a mildly elevated protein level but may be normal initially. Encephalitis may resolve in about 1 week or may persist longer, causing morbidity or death.

Transient hepatitis and diarrhea may occur during an acute infection.

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a rare, progressive, ultimately fatal, late complication of measles.

Atypical measles syndrome is a complication that occurred in people vaccinated with the original killed-virus measles vaccines, which were used in the United States from 1963 to 1967 and until the early 1970s in some other countries ( 2 ). These older vaccines altered disease expression in some patients who were incompletely protected and subsequently infected with wild-type measles. Measles manifestations developed more suddenly, and significant pulmonary involvement was more common. Confirmed cases have been extremely rare since the 1980s. Atypical measles is of note mainly because patients who received a measles vaccine during that time period may report a history of both measles vaccination and measles infection.

Complications references

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) : Measles: For Healthcare Providers. Accessed March 13, 2023.

2. CDC : Measles prevention. MMWR Suppl 38(9):1–18, 1989.

Diagnosis of Measles

History and physical examination

Serologic testing

Viral detection via culture or reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Measles may be suspected in an exposed patient who has coryza, conjunctivitis, photophobia, and cough but is usually suspected only after the rash appears. Diagnosis is usually clinical, by identifying Koplik spots or the rash in an appropriate clinical context. A complete blood count is unnecessary but, if obtained, may show leukopenia with a relative lymphocytosis.

Laboratory confirmation is necessary for public health outbreak control purposes. It is most easily done by demonstration of the presence of measles IgM antibody in an acute serum specimen or by viral culture or RT-PCR of throat swabs, blood, nasopharyngeal swabs, or urine samples. A rise in IgG antibody levels between acute and convalescent sera is highly accurate, but obtaining this information delays diagnosis. All cases of suspected measles should be reported to the local health department even before laboratory confirmation.

Differential diagnosis includes rubella , scarlet fever , drug rash , serum sickness (see table Some Causes of Urticaria ), roseola infantum , infectious mononucleosis , erythema infectiosum , and echovirus and coxsackievirus infections (see table Some Respiratory Viruses ). Manifestations can also resemble Kawasaki disease . The presenting symptoms and signs may cause diagnostic confusion in areas where measles is very rare.

Some of these conditions can be distinguished from typical measles as follows:

Rubella: A recognizable prodrome is absent, fever and other constitutional symptoms are absent or less severe, postauricular and suboccipital lymph nodes are enlarged (and usually tender), and duration is short.

Drug rash: A rash caused by drug hypersensitivity often resembles the measles rash, but a prodrome is absent, there is no cephalocaudal progression or cough, and there is usually a history of recent drug exposure.

Roseola infantum: The rash resembles that of measles, but it seldom occurs in children > 3 years of age. Initial temperature is usually high, Koplik spots and malaise are absent, and defervescence and rash occur simultaneously.

Treatment of Measles

Supportive care

Treatment of measles is supportive, including for encephalitis.

Patients are most contagious for 4 days after the development of the rash. Patients who are otherwise healthy and can be managed as outpatients should be isolated from others during their illness.

Hospitalized patients with measles should be managed with standard and airborne precautions. Single-patient airborne infection isolation rooms and N-95 respirators or similar personal protective equipment are recommended.

≥ 12 months: 200,000 international units (IU)

6 to 11 months: 100,000 IU

< 6 months: 50,000 IU

In children with clinical signs of

Prognosis for Measles

Mortality is approximately 1 to 2/1000 children in the United States, but is much higher in medically underserved countries ( 1 ). Undernutrition and may predispose to mortality.

The CDC estimates that worldwide approximately 134,000 people die each year of measles, typically from complications of pneumonia or encephalitis.

Prognosis reference

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : Global Health: Measles. Accessed 3/13/2023.

Prevention of Measles

A live-attenuated virus vaccine containing measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) is routinely given to children in most nations that have a robust health care system (see also Childhood Vaccination Schedule ).

Two doses are recommended:

The first dose at age 12 to 15 months but can be given as young as age 6 months during a measles outbreak or before international travel

The second dose at age 4 to 6 years

Infants immunized at < 1 year of age still require 2 additional doses given after their first birthday.

MMR vaccination generally provides lasting immunity and has decreased measles incidence in the United States by 99% ( 1 ). A large meta-analysis of cohort studies found the effectiveness of the MMR vaccine in preventing measles in children from age 9 months to 15 years was 95% after one dose and 96% after two doses ( 2 ).

The vaccine causes mild or inapparent, noncommunicable infection. Fever > 38 ° C occurs 5 to 12 days after inoculation in 5 to 15% of vaccinees and can be followed by a rash. Central nervous system reactions are exceedingly rare. The MMR vaccine does not cause autism .

MMR is a live vaccine and is contraindicated during pregnancy.

See MMR Vaccine for more information, including indications , contraindications and precautions , dosing and administration , and adverse effects .

Postexposure prophylaxis

Prevention in susceptible contacts is possible by giving the vaccine within 3 days of exposure. If vaccination cannot occur in that timeframe, immune globulin 0.50 mL/kg IM (maximum dose, 15 mL) is given immediately (within 6 days), with vaccination given 5 to 6 months later if medically appropriate.

Exposed patients with severe immunodeficiency, regardless of vaccination status, and pregnant women who are not immune to measles are given immune globulin 400 mg/kg IV.

In an institutional outbreak (eg, schools), susceptible contacts who refuse or cannot receive vaccination and who also have not received immune globulin should be excluded from the affected institution until 21 days after onset of rash in the last case. Exposed, susceptible health care workers should be excluded from duty from 5 days after their first exposure to 21 days after their last exposure, even if they receive postexposure prophylaxis.

Prevention references

1. McLean HQ, Fiebelkorn AP, Temte JL, Wallace GS; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : Prevention of measles, rubella, congenital rubella syndrome, and mumps, 2013: Summary recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 62(RR-04):1–34, 2013.

2. Di Pietrantonj C, Rivetti A, Marchione P, et al : Vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4(4):CD004407, 2020. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004407.pub4

Incidence of measles is highly variable depending on the vaccination rate in the population.

Measles is highly transmissible, developing in > 90% of susceptible contacts.

Measles causes approximately 134,000 deaths annually, primarily in children in medically underserved areas; pneumonia is a common cause, whereas encephalitis is less common.

Universal childhood vaccination is imperative unless contraindicated (eg, by active cancer, use of immunosuppressants, or HIV infection with severe immunosuppression).

Give postexposure prophylaxis to susceptible contacts within 3 days of exposure; use vaccine unless contraindicated, in which case give immune globulin.

More Information

The following English-language resource may be useful. Please note that THE MANUAL is not responsible for the content of this resource.

CDC: Measles Cases and Outbreaks statistics

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

- Cookie Preferences

On this page

Preparing for your appointment.

Your health care provider can usually diagnose measles based on the disease's characteristic rash as well as a small, bluish-white spot on a bright red background — Koplik's spot — on the inside lining of the cheek. Your provider may ask about whether you or your child has received measles vaccines, whether you have traveled internationally outside of the U.S. recently, and if you've had contact with anyone who has a rash or fever.

However, many providers have never seen measles. The rash can be confused with many other illnesses, too. If necessary, a blood test can confirm whether the rash is measles. The measles virus can also be confirmed with a test that generally uses a throat swab or urine sample.

There's no specific treatment for a measles infection once it occurs. Treatment includes providing comfort measures to relieve symptoms, such as rest, and treating or preventing complications.

However, some measures can be taken to protect individuals who don't have immunity to measles after they've been exposed to the virus.

- Post-exposure vaccination. People without immunity to measles, including infants, may be given the measles vaccine within 72 hours of exposure to the measles virus to provide protection against it. If measles still develops, it usually has milder symptoms and lasts for a shorter time.

- Immune serum globulin. Pregnant women, infants and people with weakened immune systems who are exposed to the virus may receive an injection of proteins (antibodies) called immune serum globulin. When given within six days of exposure to the virus, these antibodies can prevent measles or make symptoms less severe.

Medications

Treatment for a measles infection may include:

Fever reducers. If a fever is making you or your child uncomfortable, you can use over-the-counter medications such as acetaminophen (Tylenol, others), ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, Children's Motrin, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve) to help bring down the fever that accompanies measles. Read the labels carefully or ask your health care provider or pharmacist about the appropriate dose.

Use caution when giving aspirin to children or teenagers. Though aspirin is approved for use in children older than age 3, children and teenagers recovering from chickenpox or flu-like symptoms should never take aspirin. This is because aspirin has been linked to Reye's syndrome, a rare but potentially life-threatening condition, in such children.

- Antibiotics. If a bacterial infection, such as pneumonia or an ear infection, develops while you or your child has measles, your health care provider may prescribe an antibiotic.

- Vitamin A. Children with low levels of vitamin A are more likely to have a more severe case of measles. Giving a child vitamin A may lessen the severity of measles infection. It's generally given as a large dose of 200,000 international units (IU) for children older than a year. Smaller doses may be given to younger children.

If you or your child has measles, keep in touch with your health care provider as you monitor the progress of the disease and watch for complications. Also try these comfort measures:

- Take it easy. Get rest and avoid busy activities.

- Drink plenty of fluids. Drink plenty of water, fruit juice and herbal tea to replace fluids lost by fever and sweating. If needed, you can buy rehydration solutions without a prescription. These solutions contain water and salts in specific proportions to replace both fluids and electrolytes.

- Moisten the air. Use a humidifier to relieve a cough and sore throat. Adding moisture to the air can help ease discomfort. Choose a cool-mist humidifier and clean it daily because bacteria and molds can flourish in some humidifiers.

- Moisten your nose. Saline nasal sprays can soothe irritation by keeping the inside of the nose moist.

- Rest your eyes. If you or your child finds bright light irritating, as do many people with measles, keep the lights low or wear sunglasses. Also avoid reading or watching television if light from a reading lamp or from the television is bothersome.

If you suspect that you or your child has measles, you need to contact your health care provider. When you check in for the appointment, be sure to tell the check-in desk that you suspect an infectious disease. You and your child may be asked to wear a face mask or shown to an exam room immediately.

What you can do

Before your appointment, make a list of:

- Any symptoms you or your child is experiencing, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason for which you scheduled the appointment.

- Key personal information, including any recent travel or contact with someone who was sick.

- All medications, vitamins or supplements that you or your child is taking.

- Questions to ask your health care provider.

Some basic questions to ask include:

- What's the most likely cause of my or my child's symptoms?

- Are there other possible causes?

- What treatments are available, and which do you recommend?

- Is there anything I can do to make my child more comfortable?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can take with me? What websites do you recommend?

What to expect from your doctor

Your health care provider may ask that you come in before or after office hours to reduce the risk of exposing others to measles. In addition, if the provider believes that you or your child has measles, the provider must report those findings to the local health department.

Your provider is likely to ask you a number of questions, such as:

- Have you or your child been vaccinated against measles? If so, do you know when?

- Have you traveled out of the U.S. recently?

- Does anyone else live in your household? If yes, have they been vaccinated against measles?

What you can do in the meantime

While you're waiting to see the health care provider:

- Stay well hydrated

- Bring a fever down safely

- Isolate from others

May 11, 2022

- AskMayoExpert. Measles. Mayo Clinic; 2021.

- For healthcare professionals: Diagnosing and treating measles. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/index.html. Accessed Feb. 7, 2022.

- Questions about measles. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/faqs.html. Accessed Feb. 7, 2022.

- Kliegman RM, et al. Measles. In: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Feb. 7, 2022.

- Goldman L, et al., eds. Measles. In: Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Feb. 7, 2022.

- Jong EC, et al., eds. Measles. In: Netter's Infectious Diseases. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2022. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Feb. 7, 2022.

- Perrone O, et al. The importance of MMR immunization in the United States. Pediatrics. 2020; doi:10.1542/peds.2020-0251.

- Measles (rubeola): Cases and outbreaks. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html. Access Feb. 7, 2022.

- Fast facts on global measles, rubella, and congenital rubella syndrome (CRS). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/measles/data/fast-facts-global-measles-rubella.html. Accessed Feb. 7, 2022.

- AskMayoExpert. Measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccination. Mayo Clinic; 2021.

- Measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/vaccines/mmr-vaccine.html. Accessed Feb. 8, 2022.

- AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases. Recommendations for prevention and control of influenza in children, 2017-2018. Pediatrics. 2017; doi:10.1542/peds.2017-2550.

- Sullivan JE, et al. Clinical report — Fever and antipyretic use in children. Pediatrics. 2011; doi:10.1542/peds.2010-3852. Reaffirmed July 2016.

- 314 labeling of drug preparations containing salicylates. Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=76be002fc0488562bf61609b21a6b11e&mc=true&node=se21.4.201_1314&rgn=div8. Accessed Feb. 22, 2018.

- Renaud DL (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Feb. 27, 2018.

- Combination vaccines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/parents/why-vaccinate/combination-vaccines.html. Accessed Feb. 8, 2022.

- DeStefano F, et al. The MMR vaccine and autism. Annual Review of Virology. 2019; doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-092818-015515.

- Preventing waterborne germs at home. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/drinking/preventing-waterborne-germs-at-home.html#anchor_1605186128924. Accessed Feb. 9, 2022.

- Tosh PK (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Feb. 11, 2022.

- Diseases & Conditions

- Measles diagnosis & treatment

News from Mayo Clinic

More Information

- Measles vaccine: Can I get the measles if I've already been vaccinated?

CON-XXXXXXXX

5X Challenge

Thanks to generous benefactors, your gift today can have 5X the impact to advance AI innovation at Mayo Clinic.

Warning: The NCBI web site requires JavaScript to function. more...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Noah P. Kondamudi ; James R. Waymack .

Affiliations

Last Update: August 12, 2023 .

- Continuing Education Activity

Measles, also known as rubeola, is a preventable, highly contagious, acute febrile viral illness. It remains an important cause of global mortality and morbidity, particularly in the regions of Africa and Southeast Asia. It accounts for about 100,000 deaths annually despite the availability of an effective vaccine. Public health officials declared the elimination of measles from the U.S. in 2000, marking the absence of continuous disease transmission for one year and from the region of the Americas in 2016. However, outbreaks continue to occur through imported disease and transmission among unvaccinated groups of children in the community. According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), there were 372 cases in 2018 and 764 cases through May of 2019. This activity provides an overview of measles prevention, transmission, and diagnosis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in helping their patients prevent this disease.

- Describe the pathophysiology of measles.

- Describe the epidemiology of measles.

- Summarize the role of vaccination in the prevention of measles.

- Describe the importance of communication between the interprofessional care teams and patients to improve vaccination rates and thereby limit morbidity and mortality associated with measles.

- Introduction

Measles, also known as rubeola, is a preventable, highly contagious, acute febrile viral illness. It remains an important cause of global mortality and morbidity, particularly in the regions of Africa and Southeast Asia. [1] [2] It accounts for about 100,000 deaths annually despite the availability of an effective vaccine. Public health officials declared the elimination of measles from the U.S. in 2000, marking the absence of continuous disease transmission for one year and from the region of the Americas in 2016. However, outbreaks continue to occur through imported disease and transmission among unvaccinated groups of children in the community. Measles is a reportable disease in most nations, including the United States. [3]

The causative organism is the measles virus, a member of the Paramyxoviridae family and Morbillivirus genus. It is an enveloped, single-stranded, nonsegmented, negative-sense RNA virus. The genome encodes six structural proteins and two non-structural proteins, V and C. The structural proteins are nucleoprotein, phosphoprotein, matrix, fusion, haemagglutinin (HA), and large protein. The HA protein is responsible for virus attachment to the host cell. [4]

- Epidemiology

The epidemiology of measles is variable across the globe and is related to immunization levels achieved in a particular region. Before implementing widespread vaccination programs, measles accounted for an estimated 2.6 million deaths. Despite vaccination in the present era, The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that approximately 134,200 deaths (15 deaths/hour) occurred in 2015 due to measles. According to the CDC, there were 372 cases in 2018 and 764 cases through May of 2019. Measles is a reportable disease in most nations, including the United States.

The measles virus has no animal reservoir and occurs only in humans. The virus is highly contagious, with each case capable of causing 14 to 18 secondary cases among susceptible populations. Measles is transmitted from person to person by respiratory droplets, small particle aerosols, and close contact. The incubation period is 10 to 14 days, although longer periods have been reported. Unvaccinated young children and pregnant women are at high risk for contracting measles, and measles most commonly affects young children. More recently, there has been a shift to older children and adolescents due to increasing levels of immunization coverage and alterations in the levels of population immunity at different ages. Young infants born to mothers with acquired immunity are protected from measles due to passive antibody transfer, but as these antibodies wane, they become susceptible. Infectiousness of a case is maximal in the four days before and four days after the rash develops, which coincides with peak levels of viremia and the features of cough, conjunctivitis, and coryza. [5] [6] [7] [8]

- Pathophysiology

The inhaled virus from the exposed droplets initially infects the respiratory tract’s lymphocytes, dendritic cells, and alveolar macrophages. It then spreads to the adjacent lymphoid tissue and disseminates throughout the bloodstream resulting in viremia and spreading to distant organs. The virus residing in the dendritic cells and lymphocytes transfers itself to the epithelial cells of the respiratory tract, which are shed and expelled as respiratory droplets during coughing and sneezing, infecting others and perpetuating the cycle. The initial inflammation leads to symptoms of coryza, conjunctivitis, and cough. The appearance of fever coincides with the development of viremia. The skin rash occurs after dissemination and is due to perivascular and lymphocytic infiltrates.

During the prodromal phase, the measles virus depresses host immunity by suppressing interferon production through its nonstructural proteins, V and C. The increasing viral replication then triggers both humoral and cellular immunological responses. The initial humoral response consists of IgM antibody production, which is detectable 3 to 4 days after the rash appears and can persist for 6 to 8 weeks. Subsequently, IgG antibodies are produced, primarily against the viral nucleoprotein. Cellular immune responses are essential for recovery, as demonstrated by elevated Th1-dependent plasma interferon-gamma levels during the acute phase and subsequent elevation of Th2-dependent interleukin 4, interleukin 10, and interleukin 13 levels. [9]

Lymph node biopsy will show the characteristic Warthin-Finkeldey giant cells (fused lymphocytes) in a background of paracortical hyperplasia. [10]

The measles virus is known to induce immunosuppression that can last for weeks to months, even years. This causes increased susceptibility to secondary bacterial and other infections. While the mechanisms causing this phenomenon are unclear, it is hypothesized that measles infection induces the proliferation of measles-specific lymphocytes that replace the previously established memory cells causing "immune amnesia." This results in enhanced susceptibility of the host to secondary infections, leading to most of the morbidity and mortality associated with measles. The neutralizing IgG antibodies against hemagglutinin are responsible for lifelong immunity as they block host cell receptors from binding to the virus.

- History and Physical

The WHO clinical case definition of measles is "any person with fever, generalized maculopapular rash, cough, coryza, or conjunctivitis." Measles is an acute febrile exanthema that is characterized by the three “Cs”: cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis. Koplik spots, small white papules on the buccal mucosa, are pathognomonic for measles and appear a day or two before the rash, although they are not always seen. The fever precedes the rash. The rash appears first on the face and spreads caudally to become generalized. Uncomplicated measles typically resolves a week after the rash onset. [11]

The diagnosis of measles hinges on a high clinical suspicion, especially when evaluating children with febrile illness and a maculopapular rash. A complete blood count may show leukopenia, particularly lymphopenia, and thrombocytopenia. Electrolyte abnormalities may be detected in children with poor intake or diarrhea. Identification of measles-virus-specific IgM antibodies in serum or plasma confirms the diagnosis, although it may be a false negative in up to 25% of cases when done early (less than 3 days of rash onset.) These antibodies usually peak within 1 to 3 weeks after the onset of a rash and become undetectable by 4 to 8 weeks. The gold standard test is the plaque reduction neutralization assay which has the highest sensitivity. Measle virus can be cultured from nasopharyngeal secretions, but this is labor intensive and not practical. [12]

In current clinical practice, polymerase chain reaction detection of viral ribonucleic acid from throat, nasal, nasopharyngeal, and urine samples is most often performed, with sensitivity approaching 100%.

- Treatment / Management

There is no specific antiviral therapy for measles; treatment is primarily supportive. Control of fever, prevention, and correction of dehydration, and infection control measures including appropriate isolation form the mainstay of therapy. [13]

The WHO recommends the administration of daily doses of vitamin A for 2 days and more days for malnourished children. Measles complications should be identified early and appropriate therapy initiated. [14]

- Differential Diagnosis

- Drug infections

- Erythema infectiosum

- Kawasaki disease

- Parvovirus B19 infection

- Pediatric enteroviral infections

- Pediatric rubella

- Pediatric sepsis

- Pediatric toxic shock syndrome

- Scarlet fever

While many will recover from measles with no complications, there is a risk of a poor prognosis. The more common complications due to infection with measles include otitis media and diarrhea. The otitis may lead to hearing loss. Those more likely to have severe complications include infants and children under the age of five years, adults over the age of twenty, pregnant women, and those who are immunocompromised. Encephalitis may occur in 1 out of every 1000 infected children, and 1-2 of all infected children will die of neurologic or respiratory complications from measles.

- Complications

Complications of measles occur most commonly in young infants, pregnant women, and malnourished or immunocompromised children. The most common complication is pneumonia which can be due to the measles virus itself (Hecht giant cell pneumonia) or a secondary bacterial infection. Other complications include croup, otitis media, and diarrhea from secondary infections. Pregnant women with measles are at increased risk for maternal death, spontaneous abortion, intrauterine fetal death, and low birth-weight infants. Measles keratoconjunctivitis occurs mostly in children with vitamin A deficiency and can lead to blindness. Central nervous system complications include acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), measles inclusion body encephalitis (MIBE), and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). [15] ADEM is an autoimmune demyelinating disease that occurs within days to weeks. [16] MIBE is thought to be a progressive brain infection in patients with impaired cellular immunity occurring within months of the initial infection. SSPE is a progressive neurological disease that presents 5 to 10 years after the acute illness and is thought to be caused by an abnormal host response to the production of mutated virions. [17] It occurs mostly among children that developed measles before 2 years of age and manifest with seizures and progressive loss of cognitive and motor function.

- Pearls and Other Issues

Measles is a preventable disease due to the availability of a safe, inexpensive, and effective vaccine. The vaccine is a live attenuated measles strain that is used either as a single component or as a combination vaccine (MMR, MMR-V). The WHO recommends two doses of measles vaccination beginning at age 9 to 12 months and 15 to 18 months in countries where incidence and mortality are still high in the first year of life. In the United States and other developed countries, the first vaccine is given at 12 to 15 months and the second at 4 to 5 years. The WHOs Global Vaccine Action Plan has targeted measles and rubella for elimination in five WHO Regions by 2020. To eliminate measles, vaccination rates of the population must be in the 93% to 95% range.

A widely discredited and withdrawn Lancet article in 1998 created considerable misinformation, purporting a link between the MMR vaccine and autism that led to declining immunization rates, particularly in the United Kingdom and the United States. Many subsequent studies have debunked this myth.

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Measles is a preventable infection, and hence all healthcare workers, including nurses and pharmacists should educate patients on the importance of vaccination. Patients should be informed that the adverse effects of the measles vaccination are rare and minor; without vaccination, there is a high risk of transmitting the infection to others and inducing serious neurological complications.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Measles Infection DermNet New Zealand

Koplik Spots, Measles. This patient presented on the third pre-eruptive day with “Koplik spots” indicative of the beginning onset of measles. In the prodromal or beginning stages, one of the signs of the onset of measles is the eruption (more...)

Exanthem subitum (meaning sudden rash), also referred to as roseola infantum (or rose rash of infants), sixth disease (as the sixth rash-causing childhood disease) and (confusingly) baby measles, or three day fever, is a benign disease of children, generally (more...)

Measles, Day 4 Rash. This child shows a classic day 4 rash with measles. Barbara Rice, NP, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Paramyxovirus Virion Under Transmission, Electron Microscope. The image displays the viral nucleocapsid of a paramyxovirus virion as visualized under a transmission electron microscope. Fred Murphy, MD, Public Health Image Library, Public Domain, Centers (more...)

Disclosure: Noah Kondamudi declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: James Waymack declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Kondamudi NP, Waymack JR. Measles. [Updated 2023 Aug 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Measles - United States, January 4-April 2, 2015. [MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015] Measles - United States, January 4-April 2, 2015. Clemmons NS, Gastanaduy PA, Fiebelkorn AP, Redd SB, Wallace GS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015 Apr 17; 64(14):373-6.

- Measles - United States, January 1-August 24, 2013. [MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013] Measles - United States, January 1-August 24, 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 Sep 13; 62(36):741-3.

- National Update on Measles Cases and Outbreaks - United States, January 1-October 1, 2019. [MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019] National Update on Measles Cases and Outbreaks - United States, January 1-October 1, 2019. Patel M, Lee AD, Clemmons NS, Redd SB, Poser S, Blog D, Zucker JR, Leung J, Link-Gelles R, Pham H, et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Oct 11; 68(40):893-896. Epub 2019 Oct 11.

- Review Measles: Contemporary considerations for the emergency physician. [J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Ope...] Review Measles: Contemporary considerations for the emergency physician. Blutinger E, Schmitz G, Kang C, Comp G, Wagner E, Finnell JT, Cozzi N, Haddock A. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2023 Oct; 4(5):e13032. Epub 2023 Sep 9.

- Review Association Between Vaccine Refusal and Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in the United States: A Review of Measles and Pertussis. [JAMA. 2016] Review Association Between Vaccine Refusal and Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in the United States: A Review of Measles and Pertussis. Phadke VK, Bednarczyk RA, Salmon DA, Omer SB. JAMA. 2016 Mar 15; 315(11):1149-58.

Recent Activity

- Measles - StatPearls Measles - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Author: Selina SP Chen, MD, MPH; Chief Editor: Russell W Steele, MD more...

- Sections Measles

- Practice Essentials

- Pathophysiology

- Epidemiology

- Physical Examination

- Approach Considerations

- Antibody Assays

- Viral Culture

- Polymerase Chain Reaction

- Studies for Suspected Complications

- Tissue Analysis and Histologic Findings

- Supportive Care

- Antiviral Therapy

- Vitamin A Supplementation

- Postexposure Prophylaxis

- Medication Summary

- Immunoglobulins

- Questions & Answers

- Media Gallery

Measles, also known as rubeola, is one of the most contagious infectious diseases, with at least a 90% secondary infection rate in susceptible domestic contacts. Despite being considered primarily a childhood illness, measles can affect people of all ages. (See the image below.)

Although the elimination of endemic measles transmission in the US in 2000 was sustained through at least 2011, according to a CDC study, cases continue to be caused by virus brought into the country by travelers from abroad, with spread occurring largely among unvaccinated individuals. [ 1 ] From January 1 to May 23, 2014, 288 confirmed cases were reported to the CDC, and most occurred in unvaccinated individuals. [ 2 , 3 ]

A study by Gastañaduy et al found that during the 2014 outbreak, the spread of measles was contained in an undervaccinated Amish community by the isolation of case patients, quarantine of susceptible individuals, and giving the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine to more than 10,000 people. As a result, the spread of measles was limited to about 1% in an Amish community of 32,630. [ 4 ]

In 2019, 1274 cases, the highest number of cases since 1992, were reported in the United States in 31 states. All cases were linked to traveler importations that reached at-risk US populations, the majority of whom were unvaccinated or undervaccinated. [ 5 , 6 ]

Signs and symptoms

Onset of measles ranges from 7-14 days (average, 10-12 days) after exposure to the virus. The first sign of measles is usually a high fever (often >104 o F [40 o C]) that typically lasts 4-7 days. The prodromal phase is also marked by malaise; anorexia; and the classic triad of conjunctivitis, cough, and coryza (the “3 Cs”). Other possible prodromal manifestations include photophobia, periorbital edema, and myalgias.

Koplik spots—bluish-gray specks or “grains of sand” on a red base—develop on the buccal mucosa opposite the second molars

Generally appear 1-2 days before the rash and last 3-5 days

Pathognomonic for measles, but not always present

On average, the rash develops about 14 days after exposure

Mild pruritus may also occur

Blanching, erythematous macules and papules begin on the face at the hairline, on the sides of the neck, and behind the ears

Within 48 hours, the lesions coalesce into patches and plaques that spread cephalocaudally to the trunk and extremities, including the palms and soles, while beginning to regress cephalocaudally, starting from the head and neck

Lesion density is greatest above the shoulders, where macular lesions may coalesce

The eruption may also be petechial or ecchymotic in nature

Patients appear most ill during the first or second day of the rash

The exanthem lasts for 5-7 days before fading into coppery-brown hyperpigmented patches, which then desquamate

Immunocompromised patients may not develop a rash

Clinical course

Uncomplicated measles, from late prodrome to resolution of fever and rash, lasts 7-10 days

Cough may be the final symptom to appear

Modified measles

Occurs in individuals who have received serum immunoglobulin after exposure to the measles virus

The incubation period may be as long as 21 days

Similar but milder symptoms and signs may occur

Atypical measles

Occurs in individuals who were vaccinated with the original killed-virus measles vaccine between 1963 and 1967 and who have incomplete immunity

A mild or subclinical prodrome of fever, headache, abdominal pain, and myalgias precedes a rash that begins on the hands and feet and spreads centripetally

The eruption is accentuated in the skin folds and may be macular, vesicular, petechial, or urticarial

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Although the diagnosis of measles is usually determined from the classic clinical picture, laboratory identification and confirmation of the diagnosis are necessary for public health and outbreak control. Laboratory confirmation is achieved by means of the following:

Serologic testing for measles-specific IgM or IgG titers

Isolation of the virus

Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) evaluation

Measles-specific IgM titers

Obtain blood on the third day of the rash or on any subsequent day up to 1 month after onset

The measles serum IgM titer remains positive 30-60 days after the illness in most individuals but may become undetectable in some subjects at 4 weeks after rash onset

False-positive results can occur in patients with rheumatologic diseases, parvovirus B19 infection, or infectious mononucleosis

Measles-specific IgG titers

More than a 4-fold rise in IgG antibodies between acute and convalescent sera confirms measles

Acute specimens should be drawn on the seventh day after rash onset

Convalescent specimens should be drawn 10-14 days after that drawn for acute serum

The acute and convalescent sera should be tested simultaneously as paired sera

Viral culture

Throat swabs and nasal swabs can be sent on viral transport medium or a viral culturette swab

Urine specimens can be sent in a sterile container

Viral genotyping in a reference laboratory may determine whether an isolate is endemic or imported

In immunocompromised patients, isolation of the virus or identification of measles antigen by immunofluorescence may be the only feasible method of confirming the diagnosis

Polymerase chain reaction

RT-PCR, if available, can rapidly confirm the diagnosis of measles [ 7 ]

Blood, throat, nasopharyngeal, or urine specimens can be used

Samples should be collected at the first contact with a suspected case of measles

Case reporting

Immediately reporting any suspected case of measles to a local or state health department is imperative. The US CDC clinical case definition for reporting purposes requires only the following:

Generalized rash lasting 3 days or longer

Temperature of 101.0°F (38.3°C) or higher

Cough, coryza, or conjunctivitis

For reporting purposes for the CDC, cases are classified as follows:

Suspected: Any febrile illness accompanied by rash

Probable: A case that meets the clinical case definition, has noncontributory or no serologic or virologic testing, and is not epidemiologically linked to a confirmed case

Confirmed: A case that is laboratory confirmed or that meets the clinical case definition and is epidemiologically linked to a confirmed case; a laboratory-confirmed case need not meet the clinical case definition

See Workup for more detail.

Treatment of measles is essentially supportive care, as follows:

Maintenance of good hydration and replacement of fluids lost through diarrhea or emesis

IV rehydration may be necessary if dehydration is severe

Vitamin A supplementation should be considered

Postexposure prophylaxis should be considered in unvaccinated contacts; timely tracing of contacts should be a priority. Patients should receive regular follow-up care with a primary care physician for surveillance of complications arising from the infection.

Vitamin A supplementation

The World Health Organization recommends vitamin A supplementation for all children diagnosed with measles, regardless of their country of residence, based on their age, [ 8 ] as follows:

Infants younger than 6 months: 50,000 IU/day PO for 2 doses

Age 6-11 months: 100,000 IU/day PO for 2 doses

Older than 1 year: 200,000 IU/day PO for 2 doses

Children with clinical signs of vitamin A deficiency: The first 2 doses as appropriate for age, then a third age-specific dose given 2-4 weeks later

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Measles, also known as rubeola, is one of the most contagious infectious diseases, with at least a 90% secondary infection rate in susceptible domestic contacts. It can affect people of all ages, despite being considered primarily a childhood illness. Measles is marked by prodromal fever, cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and pathognomonic enanthem (ie, Koplik spots), followed by an erythematous maculopapular rash on the third to seventh day. Infection confers life-long immunity.

A generalized immunosuppression that follows acute measles frequently predisposes patients to bacterial otitis media and bronchopneumonia. In approximately 0.1% of cases, measles causes acute encephalitis. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a rare chronic degenerative disease that occurs several years after measles infection.

After an effective measles vaccine was introduced in 1963, the incidence of measles decreased significantly. Nevertheless, measles remains a common disease in certain regions and continues to account for nearly 50% of the 1.6 million deaths caused each year by vaccine-preventable childhood diseases. The incidence of measles in the United States and worldwide is increasing, with outbreaks being reported particularly in populations with low vaccination rates. [ 9 ]

Maternal antibodies play a significant role in protection against infection in infants younger than 1 year and may interfere with live-attenuated measles vaccination. A single dose of measles vaccine administered to a child older than 12 months induces protective immunity in 95% of recipients. Because measles virus is highly contagious, a 5% susceptible population is sufficient to sustain periodic outbreaks in otherwise highly vaccinated populations.

A second dose of vaccine, now recommended for all school-aged children in the United States, [ 10 ] induces immunity in about 95% of the 5% who do not respond to the first dose. Slight genotypic variation in circulating strains has not affected the protective efficacy of live-attenuated measles vaccines.

Unsubstantiated claims that suggest an association between the measles vaccine and autism have resulted in reduced vaccine use and contributed to a recent resurgence of measles in countries where immunization rates have fallen to below the level needed to maintain herd immunity. [ 11 , 12 ]

Considering that for industrialized countries such as the United States, endemic transmission of measles may be reestablished if measles immunity falls to less than 93-95%, efforts to ensure high immunization rates among people in both developed and developing countries must be sustained.

Supportive care is normally all that is required for patients with measles. Vitamin A supplementation during acute measles significantly reduces risks of morbidity and mortality.

In temperate areas, the peak incidence of infection occurs during late winter and spring. Infection is transmitted via respiratory droplets, which can remain active and contagious, either airborne or on surfaces, for up to 2 hours. Initial infection and viral replication occur locally in tracheal and bronchial epithelial cells.

After 2-4 days, measles virus infects local lymphatic tissues, perhaps carried by pulmonary macrophages. Following the amplification of measles virus in regional lymph nodes, a predominantly cell-associated viremia disseminates the virus to various organs prior to the appearance of rash.

Measles virus infection causes a generalized immunosuppression marked by decreases in delayed-type hypersensitivity, interleukin (IL)-12 production, and antigen-specific lymphoproliferative responses that persist for weeks to months after the acute infection. Immunosuppression may predispose individuals to secondary opportunistic infections, [ 13 ] particularly bronchopneumonia, a major cause of measles-related mortality among younger children.

In individuals with deficiencies in cellular immunity, measles virus causes a progressive and often fatal giant cell pneumonia .

In immunocompetent individuals, wild-type measles virus infection induces an effective immune response, which clears the virus and results in lifelong immunity. [ 14 ]

The cause of measles is the measles virus, a single-stranded, negative-sense enveloped RNA virus of the genus Morbillivirus within the family Paramyxoviridae. Humans are the natural hosts of the virus; no animal reservoirs are known to exist. This highly contagious virus is spread by coughing and sneezing via close personal contact or direct contact with secretions.

Risk factors for measles virus infection include the following:

Children with immunodeficiency due to HIV or AIDS, leukemia, alkylating agents, or corticosteroid therapy, regardless of immunization status

Travel to areas where measles is endemic or contact with travelers to endemic areas

Infants who lose passive antibody before the age of routine immunization

Risk factors for severe measles and its complications include the following:

Malnutrition

Underlying immunodeficiency

Vitamin A deficiency

United States statistics

The practice of administering 2 doses of live-attenuated measles vaccine to children to prevent school outbreaks of measles was implemented when the vaccine was first licensed in 1963. The immunization program resulted in a decrease of more than 99% in reported incidence.

From 1989 to 1991, a major resurgence occurred, affecting primarily unvaccinated preschoolers. This measles resurgence resulted in 55,000 cases and 130 deaths [ 15 ] and prompted the recommendation that a second dose of measles vaccine be given to preschoolers in a mass vaccination campaign that led to the effective elimination in the United States of endemic transmission of the measles virus. [ 16 ]

By 1993, vaccination programs had interrupted the transmission of indigenous measles virus in the United States; since then, most reported cases of measles in the United States have been linked to international travel. [ 17 ] By 1997-1999, the incidence of measles had been reduced to a historic low (< 0.5 cases per million persons). From 1997 to 2004, the reported incidence was as low as 37-116 cases per year. From November 2002 on, measles was not considered an endemic disease in the United States.

From 2000 through 2007, an average of 63 cases were reported annually to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In 2004, 34 cases were reported; after that all-time low, however, the annual incidence began to increase, with most cases linked either directly or indirectly to international travel. Incomplete vaccination rates facilitate the spread once the virus is imported to the United States.

In 2005, 66 cases of measles were reported to the CDC. [ 18 ] Of these, 34 were linked with a single outbreak in Indiana associated with the return of an unvaccinated 17-year-old American traveling in Romania. In 2006, a total of 49 confirmed cases were reported in the United States.

From January to June 2008, 131 cases of measles were reported to the CDC. [ 19 ] Although 90% of those 131 cases were associated with importation of the virus to the United States from overseas, 91% of those affected were unvaccinated or had unknown or undocumented vaccination status. At least 47% of the 131 measles infections were in school-aged children whose parents chose not to have them vaccinated. [ 19 ]

In the period from January 1 to May 20, 2011, a total of 118 cases were reported to the CDC; this represents the highest reported number of measles cases for the same period since 1996. [ 20 ] Of the 118 cases, 105 (89%) were associated with importation; the source of the remaining 13 cases could not be ascertained. In all, 105 (89%) of the 118 patients were unvaccinated; 24 (20%) were persons 12 months to 19 years of age whose parents claimed a religious or personal exemption.

Approximately half of the 118 cases—58, or 49%—were accounted for by 9 outbreaks. The largest of these outbreaks involved 21 persons in Minnesota, in a setting where parental concerns about the safety of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine caused many children to go unvaccinated. [ 21 ] As a result of this outbreak, many persons were exposed, and at least 7 infants too young to receive MMR vaccine were infected.

Although the elimination of endemic measles transmission in the US in 2000 was sustained through at least 2011, according to a CDC study, cases continue to be caused by virus brought into the country by travelers from abroad, with spread occurring largely among unvaccinated individuals. In 88% of the cases reported between 2000 and 2011, the virus originated from a country outside the US, and 2 out of every 3 individuals who developed measles were unvaccinated. Moreover, the director of the CDC noted that, in 2013, US measles cases increased threefold from the previous median, to 175 cases. [ 22 , 1 ] Most of these cases were outbreaks in children whose parents had refused immunization.

This trend of increased incidence continued into 2014. From January 1 to May 23, 2014, 288 confirmed cases were reported to the CDC, a figure that exceeds the highest reported annual total number of cases (220 cases in 2011) since measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000. Of the 288 cases, 200 (69%) occurred in unvaccinated individuals and 58 (20%) in persons with unknown vaccination status. Nearly all of the 2014 cases reported (280 [97%]) were associated with importations from at least 18 countries. Eighteen states and New York City reported measles infections during this period, and 15 outbreaks accounted for 79% of reported cases, including a large ongoing outbreak in Ohio primarily among unvaccinated Amish persons. [ 2 ]

A research letter by Clemmons et al reported 1789 cases of measles in the US from 2001 to 2015, of which, 69.5% (1243 cases) were from unvaccinated individuals. The study also reported that incidence per million population increased from 0.28 in 2001 to 0.56 in 2015. [ 23 ]

In 2019, 1274 cases, the highest number of cases in the United States since 1992, were reported in 31 states. All cases were linked to traveler importations that reached at-risk US populations, the majority of whom were unvaccinated or undervaccinated. [ 5 ]

Despite the highest recorded immunization rates in history, young children who are not appropriately vaccinated may experience more than a 60-fold increase in risk of disease due to exposure to imported measles cases from countries that have not yet eliminated the disease.

International statistics

In developing countries, measles affects 30 million children a year and causes 1 million deaths. Measles causes 15,000-60,000 cases of blindness per year.

In 1998, the cases of measles per 100,000 total population reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) was 1.6 in the Americas, 8.2 in Europe, 11.1 in the Eastern Mediterranean region, 4.2 in South East Asia, 5.0 in the Western Pacific region, and 61.7 in Africa. In 2006, only 187 confirmed cases were reported in the Western Hemisphere (mainly in Venezuela, Mexico, and the United States). [ 24 ]

Between 2000 and 2008, the number of worldwide measles cases reported to the WHO and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) declined by 67% (from 852,937 to 278,358). During the same 8-year period, global measles mortality dropped by 78%. However, it is believed that global measles incidence and mortality remain underreported, with many countries, particularly those with the highest disease burden, lacking complete, reliable surveillance data. [ 25 ]

Since 2008, France has been experiencing an outbreak of measles, which has not yet begun to slacken. [ 26 ] Over the same period, outbreaks have also been occurring in the 46 countries of the WHO African Region. [ 27 ] Worldwide, most reported cases of measles occur in Africa. [ 28 ] In 2019, the Samoan Ministry of Health declared a measles outbreak, the first Pacific island country to take action with the global resurgence of measles. [ 29 ] Vaccine hesitancy and low vaccination rates in Samoa stemmed from an erroneous mixed vaccine administration resulting in the deaths of two children in 2018. [ 30 ]

Following a worldwide decline in measles vaccination coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic, measles-related deaths rose by 43% in 2022, compared with 2021. The number of total reported cases increased by 18% during the same period, accounting for about 9 million cases and 136,000 deaths globally, mostly among children. [ 31 ]

Age-related demographics

Although measles is historically a disease of childhood, infection can occur in unvaccinated or partially vaccinated individuals of any age or in those with compromised immunity.

Unvaccinated young children are at the highest risk. Age-specific attack rates may be highest in susceptible infants younger than 12 months, school-aged children, or young adults, depending on local immunization practices and incidence of the disease. Complications such as otitis media, bronchopneumonia, laryngotracheobronchitis (ie, croup), and diarrhea are more common in young children.

Of the 66 cases of measles reported in the United States in 2005, 7 (10.6%) involved infants, 4 (6.1%) involved children aged 1-4 years, 33 (50%) involved persons aged 5-19 years, 7 (10.6%) involved adults aged 20-34 years, and 15 (22.7%) involved adults older than 35 years. [ 18 ]

Among the 118 US patients reported to have measles between January 1 and May 20, 2011, age ranged from 3 months to 68 years. [ 20 ] More than half were younger than 20 years: 18 (15%) were younger than 12 months, 24 (20%) were 1-4 years old, 23 (19%) were 5-19 years old, and 53 (45%) were 20 years of age or older.

In heavily populated, underdeveloped countries, measles is most common in children younger than 2 years.

Sex- and race-related demographics

Unvaccinated males and females are equally susceptible to infection by the measles virus. Excess mortality following acute measles has been observed among females at all ages, but it is most marked in adolescents and young adults. Excessive non–measles-related mortality has also been observed among female recipients of high-titer measles vaccines in Senegal, Guinea Bissau, and Haiti. [ 32 ]

Measles affects people of all races.

The prognosis for measles is generally good, with infection only occasionally being fatal. The CDC reports the childhood mortality rate from measles infection in the United States to be 0.1-0.2%. However, many complications and sequelae may develop, and measles is a major cause of childhood blindness in developing countries.

Morbidity and mortality

Globally, measles remains one of the leading causes of death in young children. According to the CDC, measles caused an estimated 197,000 deaths worldwide in 2007. [ 24 ] An estimated 85% of these deaths occurred in Africa and Southeast Asia. From 2000-2007, deaths worldwide fell by 74% (to 197,000 from an estimated 750,000), thanks to the partnership of several global organizations.

Case-fatality rates are higher among children younger than 5 years. The highest fatality rates are among infants aged 4-12 months and in children who are immunocompromised because of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or other causes.

Complications of measles are more likely to occur in persons younger than 5 years or older than 20 years, and morbidity and mortality are increased in persons with immune deficiency disorders, malnutrition, vitamin A deficiency, and inadequate vaccination.

Croup, encephalitis, and pneumonia are the most common causes of death associated with measles. Measles encephalitis, a rare but serious complication, has a 10% mortality.

Complications

Most complications of measles occur because the measles virus suppresses the host’s immune responses, resulting in a reactivation of latent infections or superinfection by a bacterial pathogen. Consequently, pneumonia, whether due to the measles virus itself, to tuberculosis, to or another bacterial etiology, is the most frequent complication. Pleural effusion, hilar lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, hyperesthesia, and paresthesia may also be noted.