Faculty Resources

Assignments

The assignments in this course are openly licensed, and are available as-is, or can be modified to suit your students’ needs. Selected answer keys are available to faculty who adopt Waymaker, OHM, or Candela courses with paid support from Lumen Learning. This approach helps us protect the academic integrity of these materials by ensuring they are shared only with authorized and institution-affiliated faculty and staff.

If you import this course into your learning management system (Blackboard, Canvas, etc.), the assignments will automatically be loaded into the assignment tool, where they may be adjusted, or edited there. Assignments also come with rubrics and pre-assigned point values that may easily be edited or removed.

The assignments for Introductory Psychology are ideas and suggestions to use as you see appropriate. Some are larger assignments spanning several weeks, while others are smaller, less-time consuming tasks. You can view them below or throughout the course.

You can view them below or throughout the course.

| Explain behavior from 3 perspectives. | Watch a TED talk | |

| Describe and discuss a PLOS research article. | Compare a popular news article with research article | |

| Describe parts of the brain involved in daily activities. | Create a visual/infographic about a part of the brain

| |

| Describe sleep stages and ways to improve sleep. | Track and analyze sleep and dreams. Record sleep habits and dreams a minimum of 3 days.

| |

| Demonstrate cultural differences in perception. *If used in conjunction with the “Perception and Illusions” assignment, this post could ask students to bring in examples/evidence from the illusion task. | Apply Food Lab research and the Delbouef Illusion to recommend plate size and dinner set-up.

Apply an understanding of Martin Doherty’s research on developmental and cross-cultural effects in the Ebbinghaus illusion. Find an illusion, describe it, and explain whether or not it may show cross-cultural effects. | |

| Choose to respond to two questions from a list. | Describe 3 smart people and analyze what contributes to their intelligence.

Examine an experiment about cognitive overload and decision-making when given many options. | |

| Create a mnemonic and explain an early childhood memory. | Apply knowledge from module on memory, thinking and intelligence, and states of consciousness to help a struggling student. | |

| Write examples of something learned through classical, operant, and observational learning. | Spend at least 10 days using conditioning principles to break or make a habit.

| |

| Pick an age and describe the age along with developmental theories and if you agree or disagree with the theoretical designations. | Find toys for a child of 6 months, 4 years, and 8 years, then explain theories for the age and why the toys are appropriate. | |

| Pick one question to respond to out of 4 options. | Create a shortened research proposal for a study in social psychology (or one that tests common proverbs).

| |

| Use two of the theories presented in the text to analyze the Grinch’s personality. | Take two personality tests then analyze their validity and reliability.

Examine various types of validity and design a new way to test the validity of the Blirt test. | |

| What motivates you to do your schoolwork? | Demonstrate the James-Lange, Cannon-Bard, Schachter-Singer, and cognitive-mediational theories of emotion.

Take a deeper look at the Carol Dweck study on mindset and analyze how the results may appear different if the control benchmark varied. | |

| Pick a favorite I/O topic or give advice on conducting an interview. | Investigate and reflect on KSAs needed for future job. | |

| Diagnose a fictional character with a psychological disorder. | Research one disorder and create an “At-a-Glance” paper about the main points. | |

| Choose to respond to one of four questions. | Describe 3 different treatment methods for the fictional character diagnosed for the “Diagnosing Disorders” discussion.

| |

| Give advice on managing stress or increasing happiness. | Pick from three options to do things related to tracking stress and time management.

|

CC licensed content, Original

- Assignments with Solutions. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Pencil Cup. Authored by : IconfactoryTeam. Provided by : Noun Project. Located at : https://thenounproject.com/term/pencil-cup/628840/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

General Psychology Copyright © by OpenStax and Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Faculty Resources

Assignments.

The assignments in this course are openly licensed, and are available as-is, or can be modified to suit your students’ needs. Selected answer keys are available to faculty who adopt Waymaker, OHM, or Candela courses with paid support from Lumen Learning. This approach helps us protect the academic integrity of these materials by ensuring they are shared only with authorized and institution-affiliated faculty and staff.

If you import this course into your learning management system (Blackboard, Canvas, etc.), the assignments will automatically be loaded into the assignment tool, where they may be adjusted, or edited there. Assignments also come with rubrics and pre-assigned point values that may easily be edited or removed.

The assignments for Introductory Psychology are ideas and suggestions to use as you see appropriate. Some are larger assignments spanning several weeks, while others are smaller, less-time consuming tasks. You can view them below or throughout the course.

You can view them below or throughout the course.

| —Perspectives in Psychology Explain behavior from 3 perspectives | Watch a TED talk | |

| —Analyzing Research Describe and discuss a PLOS research article | —Psychology in the News Compare a popular news article with research article | |

| —Using Your Brain Describe parts of the brain involved in daily activities | –Brain Part Infographic Create a visual/infographic about a part of the brain

| |

| —Sleep Stages Describe sleep stages and ways to improve sleep | Track and analyze sleep and dreams. Record sleep habits and dreams a minimum of 3 days.

| |

| —Cultural Influences on Perception Demonstrate cultural differences in perception. *If used in conjnuction with the “Perception and Illusions” assignment, this post could ask students to bring in examples/evidence from the illusion task | —Applications of the Delbouef Illusion Apply Food Lab research and the Delbouef Illusion to recommend plate size and dinner set-up. Apply an understanding of Martin Doherty’s research on developmental and cross-cultural effects in the Ebbinghaus illusion. Find an illusion, describe it, and explain whether or not it may show cross-cultural effects. | |

| Thinking about Intelligence Choose to respond to two questions from a list | —What Makes Smarts? Describe 3 smart people and analyze what contributes to their intelligence. —The Paradox of ChoiceExamine an experiment about cognitive overload and decision-making when given many options. | |

| —Explaining Memory Create a mnemonic and explain an early childhood memory | —Study Guide Apply knowledge from module on memory, thinking and intelligence, and states of consciousness to help a struggling student. | |

| —What I Learned Write examples of something learned through classical, operant, and observational learning | —Conditioning Project Spend at least 10 days using conditioning principles to break or make a habit.

| |

| —Stages of Development Pick an age and describe the age along with developmental theories and if you agree or disagree with the theoretical designations | —Developmental Toys Assignment Find toys for a child of 6 months, 4 years, and 8 years, then explain theories for the age and why the toys are appropriate. | |

| —Thinking about Social Psychology Pick one question to respond to out of 4 options | —Designing a Study in Social Psychology Create a shortened research proposal for a study in social psychology (or one that tests common proverbs).

| |

| —Personality and the Grinch Use two of the theories presented in the text to analyze the Grinch’s personality | —Assessing Personality Take two personality tests then analyze their validity and reliability. —Personality—BlirtatiousnessExamine various types of validity and design a new way to test the validity of the Blirt test. | |

| –What Motivates You? What motivates you to do your schoolwork? | —Theories of Emotion Demonstrate the James-Lange, Cannon-Bard, Schachter-Singer, and cognitive-mediational theories of emotion. –Growth Mindsets and the Control ConditionTake a deeper look at the Carol Dweck study on mindset and analyze how the results may appear different if the control benchmark varied. | |

| —Thinking about Industrial/Organizational Psychology Pick a favorite I/O topic or give advice on conducting an interview | — KSAs Assignment Investigate and reflect on KSAs needed for future job. | |

| —Diagnosing Disorders Diagnose a fictional character with a psychological disorder | —Disorder At-a-Glance Research one disorder and create an “At-a-Glance” paper about the main points. | |

| —Thinking about Treatment Choose to respond to one of four questions | —Treating Mental Illness Describe 3 different treatment methods for the fictional character diagnosed for the “Diagnosing Disorders” discussion.

| |

| —Thoughts on Stress and Happiness Give advice on managing stress or increasing happiness | –Time and Stress Management Pick from three options to do things related to tracking stress and time management.

|

Discussion Grading Rubric

The discussions in the course vary in their requirements and design, but this rubric below may be used and modified to facilitate grading.

| Response is superficial, lacking in analysis or critique. Contributes few novel ideas, connections, or applications. | Provides an accurate response to the prompt, but the information delivered is limited or lacking in analysis. | Provides a thoughtful and clear response to the content or question asked. The response includes original thoughts and novel ideas. | __/4 | |

| Includes vague or incomplete supporting evidence or fails to back opinion with facts. | Supports opinions with details, though connections may be unclear, not firmly established, or explicit. | Supports response with evidence; makes connections to the course content and/or other experiences. Cites evidence when appropriate. | __/2 | |

| Provides brief responses or shows little effort to participate in the learning community. | Responds kindly and builds upon the comments from others, but may lack depth, detail, and/or explanation. | Kindly and thoroughly extend discussions already taking place or poses new possibilities or opinions not previously voiced. Responses are substantive and constructive. | __/4 | |

| Total | __/10 |

- Assignments with Solutions. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Pencil Cup. Authored by : IconfactoryTeam. Provided by : Noun Project. Located at : https://thenounproject.com/term/pencil-cup/628840/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1. Introducing Psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior . The word “psychology” comes from the Greek words “psyche,” meaning life , and “logos,” meaning explanation . Psychology is a popular major for students, a popular topic in the public media, and a part of our everyday lives. Television shows such as Dr. Phil feature psychologists who provide personal advice to those with personal or family difficulties. Crime dramas such as CSI , Lie to Me , and others feature the work of forensic psychologists who use psychological principles to help solve crimes. And many people have direct knowledge about psychology because they have visited psychologists, for instance, school counselors, family therapists, and religious, marriage, or bereavement counselors.

Because we are frequently exposed to the work of psychologists in our everyday lives, we all have an idea about what psychology is and what psychologists do. In many ways I am sure that your conceptions are correct. Psychologists do work in forensic fields, and they do provide counseling and therapy for people in distress. But there are hundreds of thousands of psychologists in the world, and most of them work in other places, doing work that you are probably not aware of.

Most psychologists work in research laboratories, hospitals, and other field settings where they study the behavior of humans and animals. For instance, my colleagues in the Psychology Department at the University of Maryland study such diverse topics as anxiety in children, the interpretation of dreams, the effects of caffeine on thinking, how birds recognize each other, how praying mantises hear, how people from different cultures react differently in negotiation, and the factors that lead people to engage in terrorism. Other psychologists study such topics as alcohol and drug addiction, memory, emotion, hypnosis, love, what makes people aggressive or helpful, and the psychologies of politics, prejudice, culture, and religion. Psychologists also work in schools and businesses, and they use a variety of methods, including observation, questionnaires, interviews, and laboratory studies, to help them understand behavior.

This chapter provides an introduction to the broad field of psychology and the many approaches that psychologists take to understanding human behavior. We will consider how psychologists conduct scientific research, with an overview of some of the most important approaches used and topics studied by psychologists, and also consider the variety of fields in which psychologists work and the careers that are available to people with psychology degrees. I expect that you may find that at least some of your preconceptions about psychology will be challenged and changed, and you will learn that psychology is a field that will provide you with new ways of thinking about your own thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Psychology is in part the study of behavior. Why do you think these people are behaving the way they are?

- Dominic Alves - Café Smokers - CC BY 2.0; Daniela Vladimirova - Reservoir Dogs debate, 3 in the morning - CC BY 2.0; Kim Scarborough - Old Ladies - CC BY-SA 2.0; Pedro Ribeiro Simões - Playing Chess - CC BY 2.0; epSos .de - Young Teenagers Playing Guitar Band of Youth - CC BY 2.0; Marco Zanferrari - 1... - CC BY-SA 2.0; CC BY 2.0 Pedro Ribeiro Simões - Relaxing - CC BY 2.0. ↵

Introduction to Psychology Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

You must enable JavaScript in order to use this site.

Service update: Some parts of the Library’s website will be down for maintenance on August 11.

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Psychology 1: assignment.

- Find Popular Press Article

- Find Peer Reviewed Article: Strategy 1

- Find Peer Reviewed Article: Strategy 2

- Off-Campus Access + Getting Help

Assignment 3: Popular Press vs. Peer Reviewed Articles

Overview: Like a literature review, this assignment is intended to have you compare and contrast the writing style and potential uses of a popular press article versus a peer-reviewed primary research article that discusses a psychological phenomenon, written within the last 10 years. The articles need to address the same area of interest (for example, depression and gender, love and crying, teenage norms and ostracism etc.), but do not have to necessarily be about the same exact experiment. For hints on appropriate psychological phenomena, reference the textbook and lecture notes.

List of journals for Psych 1 assignment

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychologist

- Health Psychology

- Journal of Abnormal Psychology

- Journal of Applied Psychology

- Journal of Comparative Psychology

- Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology

- Journal of Counseling Psychology

- Journal of Educational Psychology

- Journal of Mind and Behavior most recent 4 years not available

- Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

- Journal of Social Psychology

- Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology

- Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

- Next: Find Popular Press Article >>

- Last Updated: Aug 6, 2024 3:12 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/psychology1

Browse Course Material

Course info.

- Prof. John D. E. Gabrieli

Departments

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

As Taught In

- Cognitive Science

Learning Resource Types

Introduction to psychology, writing assignment 1.

Topic: Are studies of cognitive and emotional developments in adolescents useful for setting public policy guidelines?

To begin this assignment, you will read three sources (full citations and abstracts below):

- An analysis by Steinberg et al. of emotional and cognitive development in adolescents and how our understanding of these topics should be used in setting public policy, such as juvenile access to abortions or the death penalty;

- A criticism of this position by Fischer et al., who have a different perspective on how public policy should take into account emotional and cognitive development in juveniles; and,

- A rebuttal of the Fischer position by Steinberg et al.

Review the writing assignment guidelines given on the Syllabus . Your specific goal for Writing Assignment 1 is to analyze the arguments in the three papers, construct a coherent argument about the role of studies of cognitive and emotional development in setting public policy guidelines, and support this argument with specific evidence from the papers. A number of different approaches to this topic can satisfy the requirements of this writing assignment. For example, your thesis might address:

- In what circumstances can psychological research on cognitive and emotional development be used to set public policy?

- When, if ever, should public policy distinguish between cognitive and emotional development and why (or why not)?

- Whose view of psychological development – Steinberg or Fischer – is better for setting public policy and why?

There is no “correct” answer you are expected to discover. Instead, you should read the papers and develop your own conclusion about what role psychological research should play in setting public policy. Your thesis should clearly state your position, and you should use the rest of the paper to justify your conclusion with specific evidence from the background readings.

Abstracts are presented courtesy of the American Psychological Association.

Steinberg, L., et al. “ Are Adolescents Less Mature than Adults? Minors’ Access to Abortion, the Juvenile Death Penalty, and the Alleged APA ‘Flip-Flop’ .” American Psychologist 64, no. 7 (2009): 583–94.

Abstract : “The American Psychological Association’s (APA’s) stance on the psychological maturity of adolescents has been criticized as inconsistent. In its Supreme Court amicus brief in Roper v. Simmons (2005), which abolished the juvenile death penalty, APA described adolescents as developmentally immature. In its amicus brief in Hodgson v. Minnesota (1990), however, which upheld adolescents’ right to seek an abortion without parental involvement, APA argued that adolescents are as mature as adults. The authors present evidence that adolescents demonstrate adult levels of cognitive capability earlier than they evince emotional and social maturity. On the basis of this research, the authors argue that it is entirely reasonable to assert that adolescents possess the necessary skills to make an informed choice about terminating a pregnancy but are nevertheless less mature than adults in ways that mitigate criminal responsibility. The notion that a single line can be drawn between adolescence and adulthood for different purposes under the law is at odds with developmental science. Drawing age boundaries on the basis of developmental research cannot be done sensibly without a careful and nuanced consideration of the particular demands placed on the individual for “adult-like” maturity in different domains of functioning.”

Fischer, K. W., et al. “ Narrow Assessments Misrepresent Development and Misguide Policy .” American Psychologist 64, no. 7 (2009): 595–600.

Abstract : “Intellectual and psychosocial functioning develop along complex learning pathways. Steinberg, Cauffman, Woolard, Graham, and Banich (see record 2009-18110-001 ) measured these two classes of abilities with narrow, biased assessments that captured only a segment of each pathway and created misleading age patterns based on ceiling and floor effects. It is a simple matter to shift the assessments to produce the opposite pattern, with cognitive abilities appearing to develop well into adulthood and psychosocial abilities appearing to stop developing at age 16. Their measures also lacked a realistic connection to the lived behaviors of adolescents, abstracting too far from messy realities and thus lacking ecological validity and the nuanced portrait that the authors called for. A drastically different approach to assessing development is required that (a) includes the full age-related range of relevant abilities instead of a truncated set and (b) examines the variability and contextual dependence of abilities relevant to the topics of murder and abortion.”

Steinberg, L., et al. (2009b) “ Reconciling the Complexity of Human Development with the Reality of Legal Policy .” American Psychologist 64, no. 7 (2009): 601–4.

Abstract : “The authors respond to both the general and specific concerns raised in Fischer, Stein, and Heikkinen’s (see record 2009-18110-002 ) commentary on their article (Steinberg, Cauffman, Woolard, Graham, & Banich) (see record 2009-18110-001 ), in which they drew on studies of adolescent development to justify the American Psychological Association’s positions in two Supreme Court cases involving the construction of legal age boundaries. In response to Fischer et al.’s general concern that the construction of bright-line age boundaries is inconsistent with the fact that development is multifaceted, variable across individuals, and contextually conditioned, the authors argue that the only logical alternative suggested by that perspective is impractical and unhelpful in a legal context. In response to Fischer et al.’s specific concerns that their conclusion about the differential timetables of cognitive and psychosocial maturity is merely an artifact of the variables, measures, and methods they used, the authors argue that, unlike the alternatives suggested by Fischer et al., their choices are aligned with the specific capacities under consideration in the two cases. The authors reaffirm their position that there is considerable empirical evidence that adolescents demonstrate adult levels of cognitive capability several years before they evince adult levels of psychosocial maturity.”

You are leaving MIT OpenCourseWare

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

50+ Research Topics for Psychology Papers

How to Find Psychology Research Topics for Your Student Paper

- Specific Branches of Psychology

- Topics Involving a Disorder or Type of Therapy

- Human Cognition

- Human Development

- Critique of Publications

- Famous Experiments

- Historical Figures

- Specific Careers

- Case Studies

- Literature Reviews

- Your Own Study/Experiment

Are you searching for a great topic for your psychology paper ? Sometimes it seems like coming up with topics of psychology research is more challenging than the actual research and writing. Fortunately, there are plenty of great places to find inspiration and the following list contains just a few ideas to help get you started.

Finding a solid topic is one of the most important steps when writing any type of paper. It can be particularly important when you are writing a psychology research paper or essay. Psychology is such a broad topic, so you want to find a topic that allows you to adequately cover the subject without becoming overwhelmed with information.

I can always tell when a student really cares about the topic they chose; it comes through in the writing. My advice is to choose a topic that genuinely interests you, so you’ll be more motivated to do thorough research.

In some cases, such as in a general psychology class, you might have the option to select any topic from within psychology's broad reach. Other instances, such as in an abnormal psychology course, might require you to write your paper on a specific subject such as a psychological disorder.

As you begin your search for a topic for your psychology paper, it is first important to consider the guidelines established by your instructor.

Research Topics Within Specific Branches of Psychology

The key to selecting a good topic for your psychology paper is to select something that is narrow enough to allow you to really focus on the subject, but not so narrow that it is difficult to find sources or information to write about.

One approach is to narrow your focus down to a subject within a specific branch of psychology. For example, you might start by deciding that you want to write a paper on some sort of social psychology topic. Next, you might narrow your focus down to how persuasion can be used to influence behavior .

Other social psychology topics you might consider include:

- Prejudice and discrimination (i.e., homophobia, sexism, racism)

- Social cognition

- Person perception

- Social control and cults

- Persuasion, propaganda, and marketing

- Attraction, romance, and love

- Nonverbal communication

- Prosocial behavior

Psychology Research Topics Involving a Disorder or Type of Therapy

Exploring a psychological disorder or a specific treatment modality can also be a good topic for a psychology paper. Some potential abnormal psychology topics include specific psychological disorders or particular treatment modalities, including:

- Eating disorders

- Borderline personality disorder

- Seasonal affective disorder

- Schizophrenia

- Antisocial personality disorder

- Profile a type of therapy (i.e., cognitive-behavioral therapy, group therapy, psychoanalytic therapy)

Topics of Psychology Research Related to Human Cognition

Some of the possible topics you might explore in this area include thinking, language, intelligence, and decision-making. Other ideas might include:

- False memories

- Speech disorders

- Problem-solving

Topics of Psychology Research Related to Human Development

In this area, you might opt to focus on issues pertinent to early childhood such as language development, social learning, or childhood attachment or you might instead opt to concentrate on issues that affect older adults such as dementia or Alzheimer's disease.

Some other topics you might consider include:

- Language acquisition

- Media violence and children

- Learning disabilities

- Gender roles

- Child abuse

- Prenatal development

- Parenting styles

- Aspects of the aging process

Do a Critique of Publications Involving Psychology Research Topics

One option is to consider writing a critique paper of a published psychology book or academic journal article. For example, you might write a critical analysis of Sigmund Freud's Interpretation of Dreams or you might evaluate a more recent book such as Philip Zimbardo's The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil .

Professional and academic journals are also great places to find materials for a critique paper. Browse through the collection at your university library to find titles devoted to the subject that you are most interested in, then look through recent articles until you find one that grabs your attention.

Topics of Psychology Research Related to Famous Experiments

There have been many fascinating and groundbreaking experiments throughout the history of psychology, providing ample material for students looking for an interesting term paper topic. In your paper, you might choose to summarize the experiment, analyze the ethics of the research, or evaluate the implications of the study. Possible experiments that you might consider include:

- The Milgram Obedience Experiment

- The Stanford Prison Experiment

- The Little Albert Experiment

- Pavlov's Conditioning Experiments

- The Asch Conformity Experiment

- Harlow's Rhesus Monkey Experiments

Topics of Psychology Research About Historical Figures

One of the simplest ways to find a great topic is to choose an interesting person in the history of psychology and write a paper about them. Your paper might focus on many different elements of the individual's life, such as their biography, professional history, theories, or influence on psychology.

While this type of paper may be historical in nature, there is no need for this assignment to be dry or boring. Psychology is full of fascinating figures rife with intriguing stories and anecdotes. Consider such famous individuals as Sigmund Freud, B.F. Skinner, Harry Harlow, or one of the many other eminent psychologists .

Psychology Research Topics About a Specific Career

Another possible topic, depending on the course in which you are enrolled, is to write about specific career paths within the field of psychology . This type of paper is especially appropriate if you are exploring different subtopics or considering which area interests you the most.

In your paper, you might opt to explore the typical duties of a psychologist, how much people working in these fields typically earn, and the different employment options that are available.

Topics of Psychology Research Involving Case Studies

One potentially interesting idea is to write a psychology case study of a particular individual or group of people. In this type of paper, you will provide an in-depth analysis of your subject, including a thorough biography.

Generally, you will also assess the person, often using a major psychological theory such as Piaget's stages of cognitive development or Erikson's eight-stage theory of human development . It is also important to note that your paper doesn't necessarily have to be about someone you know personally.

In fact, many professors encourage students to write case studies on historical figures or fictional characters from books, television programs, or films.

Psychology Research Topics Involving Literature Reviews

Another possibility that would work well for a number of psychology courses is to do a literature review of a specific topic within psychology. A literature review involves finding a variety of sources on a particular subject, then summarizing and reporting on what these sources have to say about the topic.

Literature reviews are generally found in the introduction of journal articles and other psychology papers , but this type of analysis also works well for a full-scale psychology term paper.

Topics of Psychology Research Based on Your Own Study or Experiment

Many psychology courses require students to design an actual psychological study or perform some type of experiment. In some cases, students simply devise the study and then imagine the possible results that might occur. In other situations, you may actually have the opportunity to collect data, analyze your findings, and write up your results.

Finding a topic for your study can be difficult, but there are plenty of great ways to come up with intriguing ideas. Start by considering your own interests as well as subjects you have studied in the past.

Online sources, newspaper articles, books , journal articles, and even your own class textbook are all great places to start searching for topics for your experiments and psychology term papers. Before you begin, learn more about how to conduct a psychology experiment .

What This Means For You

After looking at this brief list of possible topics for psychology papers, it is easy to see that psychology is a very broad and diverse subject. While this variety makes it possible to find a topic that really catches your interest, it can sometimes make it very difficult for some students to select a good topic.

If you are still stumped by your assignment, ask your instructor for suggestions and consider a few from this list for inspiration.

- Hockenbury, SE & Nolan, SA. Psychology. New York: Worth Publishers; 2014.

- Santrock, JW. A Topical Approach to Lifespan Development. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Navigation Menu

Search code, repositories, users, issues, pull requests..., provide feedback.

We read every piece of feedback, and take your input very seriously.

Saved searches

Use saved searches to filter your results more quickly.

To see all available qualifiers, see our documentation .

- Notifications You must be signed in to change notification settings

NPTEL Assignment Answers and Solutions 2024 (July-Dec). Get Answers of Week 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 8 10 11 12 for all courses. This guide offers clear and accurate answers for your all assignments across various NPTEL courses

progiez/nptel-assignment-answers

Folders and files.

| Name | Name | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 164 Commits | ||||

Repository files navigation

Nptel assignment answers 2024 with solutions (july-dec), how to use this repo to see nptel assignment answers and solutions 2024.

If you're here to find answers for specific NPTEL courses, follow these steps:

Access the Course Folder:

- Navigate to the folder of the course you are interested in. Each course has its own folder named accordingly, such as cloud-computing or computer-architecture .

Locate the Weekly Assignment Files:

- Inside the course folder, you will find files named week-01.md , week-02.md , and so on up to week-12.md . These files contain the assignment answers for each respective week.

Select the Week File:

- Click on the file corresponding to the week you are interested in. For example, if you need answers for Week 3, open the week-03.md file.

Review the Answers:

- Each week-XX.md file provides detailed solutions and explanations for that week’s assignments. Review these files to find the information you need.

By following these steps, you can easily locate and use the assignment answers and solutions for the NPTEL courses provided in this repository. We hope this resource assists you in your studies!

List of Courses

Here's a list of courses currently available in this repository:

- Artificial Intelligence Search Methods for Problem Solving

- Cloud Computing

- Computer Architecture

- Cyber Security and Privacy

- Data Science for Engineers

- Data Structure and Algorithms Using Java

- Database Management System

- Deep Learning for Computer Vision

- Deep Learning IIT Ropar

- Digital Circuits

- Ethical Hacking

- Introduction to Industry 4.0 and Industrial IoT

- Introduction to Internet of Things

- Introduction to Machine Learning IIT KGP

- Introduction to Machine Learning

- Introduction to Operating Systems

- ML and Deep Learning Fundamentals and Applications

- Problem Solving Through Programming in C

- Programming DSA Using Python

- Programming in Java

- Programming in Modern C

- Python for Data Science

- Soft Skill Development

- Soft Skills

- Software Engineering

- Software Testing

- The Joy of Computation Using Python

- Theory of Computation

Note: This repository is intended for educational purposes only. Please use the provided answers as a guide to better understand the course material.

📧 Contact Us

For any queries or support, feel free to reach out to us at [email protected] .

🌐 Connect with Progiez

⭐️ Follow Us

Stay updated with our latest content and updates by following us on our social media platforms!

🚀 About Progiez

Progiez is an online educational platform aimed at providing solutions to various online courses offered by NPTEL, Coursera, LinkedIn Learning, and more. Explore our resources for detailed answers and solutions to enhance your learning experience.

Disclaimer: This repository is intended for educational purposes only. All content is provided for reference and should not be submitted as your own work.

Contributors 3

3 Ways War Affects Sleep Long Term

War ends, but the effects on sleep can linger for life..

Posted September 1, 2024 | Reviewed by Kaja Perina

- Why Is Sleep Important?

- Take our Sleep Habits Test

- Find a sleep counsellor near me

- War has a negative and lasting impact on sleep.

- Sleep deprivation, trauma, environmental factors, and social factors can contribute to chronic suffering.

- Veterans, refugees, and even children born after a war experience disrupted sleep for years.

The right to live in peace is enshrined in the United Nations' 2016 Declaration on the Right to Peace . War and conflict affect people's lives in thousands of different ways, one of which is how we sleep. Even when war ends, the effects of that experience linger on in struggles to feel rested.

Here are three examples of how war creates chronic sleep difficulties for soldiers, victims of violence, and even the next generation of children.

1. Children Conceived After the War

Parents' war-related stress can lead to children's ongoing sleep challenges, even when those children are conceived after the war has stopped. In one study , children's sleep patterns were reported by the mothers and by the children themselves at various ages up to age 10.

These children were born in an Israeli hospital to some mothers who witnessed bombings directly and to some mothers who were not directly exposed. This war experience happened shortly before the child was conceived. The children in the study were conceived two to twelve months later.

For mothers who experienced high emotional distress during war in the months before conception, daughters' sleep was significantly affected up to age 10 (when the study ended). While boys showed no sleep disruption correlating with their mother's war distress, girls had disturbances in the areas of "night wakings, parasomnias, sleep-disordered breathing, sleep anxiety , and bedtime resistance." (The study does not mention nonbinary children.)

2. Refugees and New Social Conditions

When refugees struggle to get good sleep in their new country, the trauma of the war at home isn't the only reason. Around 6.5 million Ukrainians fled fled their country in the face of a Russian invasion. Researchers found that in some cases these refugees' subsequent sleep disruptions related to changes in diet and social rhythms (such as the timing of work).

While PTSD and other mental health struggles contribute to unsatisfying sleep , other factors can matter at least as much. Many Sudanese men who fled their country and found sanctuary in Australia suffered from insomnia , restless legs, daytime sleepiness and fatigue.Sudanese women refugees did not seem to have the same high levels of difficulties with sleep.

The men's sleep issues may not only relate to the trauma of war in their homeland, but also to low income and lack of employment opportunities in their new country.

3. Veterans and Chronic Fatigue

Soldiers rarely get enough sleep . In some cases, this sleep deprivation becomes chronic even after they've left the military. Nearly 1 in 3 US veterans who were deployed in the 1990-91 Gulf War returned with a complex condition known as Gulf War Illness.

Many people who fought in later wars, such as the American war in Iraq and Afghanistan, returned with similar symptoms, although there are some differences. The main symptoms are chronic fatigue and pain, as well as low mood and poor memory .

A study in California found that Gulf War veterans with poor sleep had a smaller brainstem than the control group. We still don't know the exact causes of Gulf War Illness, but some theories suggest it could be related to environmental conditions like dust exposure, burning oil wells, chemical weapons, and more, as well as psychological distress and PTSD .

Whatever the cause, these veterans continue to suffer from the effects of their war experience, decades later.

Marion Lougheed is an anthropologist, editor, and writer whose research focuses on the cultural dimensions of sleep. She is currently finishing up a Ph.D. in social anthropology at York University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Centre

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- Calgary, AB

- Edmonton, AB

- Hamilton, ON

- Montréal, QC

- Toronto, ON

- Vancouver, BC

- Winnipeg, MB

- Mississauga, ON

- Oakville, ON

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Almost 3,000 prisoners waiting for psychology and addiction services

The importance of addressing the drugs crisis in prisons around the country was brought into sharp focus last month when 11 suspected drug overdoses were rushed to hospital from Portlaoise Prison. Picture: Collins Photos

Almost 3,000 people in Irish prisons are on waiting lists to access psychology and addiction services.

The number of people waiting to for a psychology appointment is almost four times the number currently receiving mental health services in the prison system.

As of August 1, the number of people on the prison psychology service was 526 while approximately 2,090 are waiting to be seen.

According to the Irish Prison Service (IPS), the average wait time for a psychology service is 31.4 days.

In addition, the most recent figures from the Department of Justice shows that at the end of June, there were 888 prisoners waiting to access addiction counselling services.

The importance of addressing the drugs crisis in prisons around the country was brought into sharp focus last month when 11 suspected drug overdoses were rushed to hospital from Portlaoise Prison.

Earlier in the summer, prison numbers breached the 5,000 mark for the first time ever and the department estimates that up to 70% of the prisoner population have addiction issues.

It is simply not good enough that prisoners are not getting the supports that they need while in custody, Sinn Féin TD Mark Ward said.

There has been a problem with drugs in our prison for a long, long time now and if somebody is actively seeking help for their addiction they should be given that help at the earliest possible stage.

Mr Ward said it is "simply not good enough" to have a 12-week delay in accessing the necessary services.

With dangerous new drugs circulating in Irish prisons, mental health and addiction supports are more than just life-changing, they are life saving, the Dublin TD said.

Addiction therapy in prisons is provided through Merchant's Quay Ireland with 19 addiction counsellors currently working with recent recruitments set to increase this capacity.

There are approximately 350 prisoners under the care of psychiatric services who have a diagnosis such as schizophrenia and psychosis. A waiting list for those who are critically ill and require admission to the Central Mental Hospital for treatment varied between 15-25 people over the last three years with the list reviewed on a weekly basis.

Irish Penal Reform Trust (IPRT) executive director Saoirse Brady said the current situation in prisons is concerning as prison is inherently traumatic but is compounded when it is overcrowded.

Ms Brady said the IPS is failing to reach its own targets for the number of people who should be seen by a psychologist.

In 2022, the target was 2,000 prisoners but just 1,303 people were seen. Last year, the target was raised to 2,200 but the real figure fell short once again with 1,627 prisoners seen in 2023.

The IPRT will be asking for further investment in prison services in the upcoming budget to resource prison psychology service and addiction couselling.

"I would say they need to invest at least €1m in mental health and addiction services within prison to really address some of those basic needs that people have," said Ms Brady.

The IPS have put forward proposals for additional mental health support as part of the estimates process for Budget 2025, and these are being considered.

Irish Examiner’s WhatsApp channel

Follow and share the latest news and stories

More in this section

Watch: Thousands line Skibbereen streets for Olympic Gold winning rowers homecoming

Lunchtime News

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Please click here for our privacy statement.

Puzzles hub

Jennifer Horgan

For a fresh perspective on life today

Sunday, September 1, 2024 - 3:00 PM

Monday, September 2, 2024 - 9:00 AM

Sunday, September 1, 2024 - 10:00 PM

Fergus Finlay

Family Notices

© Examiner Echo Group Limited

- Open access

- Published: 31 August 2024

The links between symptom burden, illness perception, psychological resilience, social support, coping modes, and cancer-related worry in Chinese early-stage lung cancer patients after surgery: a cross-sectional study

- Yingzi Yang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4242-0444 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Xiaolan Qian 1 na1 ,

- Xuefeng Tang 1 ,

- Chen Shen 2 ,

- Yujing Zhou 3 ,

- Xiaoting Pan 2 &

- Yumei Li 4

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 463 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

This study aims to investigate the links between the clinical, demographic, and psychosocial factors and cancer-related worry in patients with early-stage lung cancer after surgery.

The study utilized a descriptive cross-sectional design. Questionnaires, including assessments of cancer-related worry, symptom burden, illness perception, psychological resilience, coping modes, social support and participant characteristics, were distributed to 302 individuals in early-stage lung cancer patients after surgery. The data collection period spanned from January and October 2023. Analytical procedures encompassed descriptive statistics, independent Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, Kruskal-Wallis- H - test, Spearman correlation analysis, and hierarchical multiple regression.

After surgery, 89.07% had cancer-related worries, with a median (interquartile range, IQR) CRW score of 380.00 (130.00, 720.00). The most frequently cited concern was the cancer itself (80.46%), while sexual issues were the least worrisome (44.37%). Regression analyses controlling for demographic variables showed that higher levels of cancer-related worry (CRW) were associated with increased symptom burden, illness perceptions, and acceptance-rejection coping modes, whereas they had lower levels of psychological resilience, social support and confrontation coping modes, and were more willing to obtain information about the disease from the Internet or applications. Among these factors, the greatest explanatory power in the regression was observed for symptom burden, illness perceptions, social support, and sources of illness information (from the Internet or applications), which collectively explained 52.00% of the variance.

Conclusions

Healthcare providers should be aware that worry is a common issue for early stage lung cancer survivors with a favorable prognosis. During post-operative recovery, physicians should identify patient concerns and address unmet needs to improve patients’ emotional state and quality of life through psychological support and disease education.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Lung cancer is a common malignant neoplasm that often causes considerable psychological distress to patients and their families [ 1 ]. Due to the increasing public awareness of health screening in recent years and the use and promotion of low-dose computed tomography (CT) screening for early screening and detection of lung cancer, the incidence of early-stage lung cancer has been increasing [ 2 ]. According to the clinical diagnostic criteria for lung cancer, early-stage non-small cell lung cancer refers to a tumor that is confined to the lung and has not metastasized to distant organs or lymph nodes, generally referring to stage I and II [ 3 , 4 ]. For individuals diagnosed with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer, radical surgical resection offers the most beneficial treatment option for extended survival [ 5 , 6 ]. It can be said that after diagnosis and active treatment of early-stage lung cancer patients, the recurrence rate 5 years after surgery is low. Although the survival rate after radical resection has improved, a decline in lung function is inevitable. According to studies [ 7 , 8 ], lung function experienced a steep decline at 1 month after lung resection, partially recovered at 3 months, and stabilized at 6 months after surgery. Patients who have undergone surgery for lung cancer often experience post-treatment symptoms, including pain, dyspnea, and fatigue, which negatively affect their quality of life [ 9 ]. A previous study conducted by our team [ 10 ] found that post-operative lung cancer patients had various unmet needs during their recovery, including physiological, safety, family and social support, and disease information. The psychological distress experienced by patients, including worry, anxiety, and fear, increases due to unmet needs after cancer treatments [ 11 , 12 ].

In recent years, there has been an increasing focus on Cancer-related worry (CRW) as a form of psychological distress experienced by cancer patients. CRW refers to the uncertainty of cancer patients’ future after cancer diagnosis. It encompasses areas of common concern to cancer patients, such as cancer itself, disability, family, work, economic status, loss of independence, physical pain, psychological pain, medical uncertainty, and death. The purpose of CRW is to reflect the unmet needs or concerns of cancer patients [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Unlike anxiety, worry primarily reflects the patient’s repetitive thoughts about the uncertainty of the future [ 13 ]. It is also a cognitive manifestation of the uncertainty of disease prognosis [ 16 ].

Currently, measurement scales such as the State Train Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) are frequently used to evaluate physical symptoms caused by autonomic nervous activity in patients. However, they do not assess patients’ concerns or anxiety content [ 17 ]. Some scholars [ 13 , 17 , 18 ] have developed tools to measure the degree and content of cancer-related worries. The CRW questionnaire is a tool for measuring and evaluating the anxiety status of patients. It can also detect their needs or preferences through convenient means, allowing for the design of personalized care [ 13 ]. These questionnaires were primarily utilized to assess the level and nature of worry among cancer patients diagnosed with breast, prostate, skin, and adolescent cancers [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ], However, it has not been employed in the post-operative population for early-stage lung cancer.

Theory framework

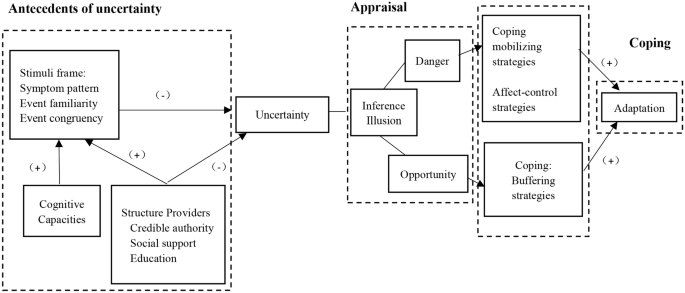

Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Theory [ 23 ] defines illness uncertainty as a cognitive state that arises when individuals lack sufficient information to effectively construct or categorize disease-related events. The theory explains how patients interpret the uncertainty of treatment processes and outcomes through a cognitive framework. It consists of three main components (see Fig. 1 ): (a) antecedents of uncertainty, (b) appraisal of uncertainty, and (c) coping with uncertainty. The antecedents of uncertainty include the stimulus frame (such as symptom burden), cognitive capacity (like disease perception), and structure providers (including social support and sources of disease information). Managing uncertainty requires coping modes such as emotional regulation and proactive problem-solving. Studies [ 24 ] have shown that there is a correlation between the way patients manage their emotions and the coping modes they experience when faced with difficulties. Patients with positive emotional coping modes are less likely to worry, while patients with avoidance coping modes are more likely to experience emotional distress. Furthermore, previous research [ 25 ] has shown a strong correlation between psychological resilience and cancer-related worries. Psychological resilience reflected an individual’s ability to adapt and cope with stress or adversity, and was an important indicator of a patient’s psychological traits [ 26 ]. Furthermore, it had a significant impact on their mental state and quality of life. Specifically, higher levels of cancer worries have been linked to lower levels of psychological resilience.

Based on the theoretical framework and literature research presented, it is hypothesized that factors such as psychological resilience, antecedents of disease uncertainty (symptom burden, disease perception, social support and sources of disease information), and coping modes will correlate with the level of cancer-related worries in postoperative patients with early-stage lung cancer. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the potential correlates of cancer-related worry in early-stage lung cancer patients after surgery. This analysis will aid medical professionals in comprehending the worry state and unmet needs of early-stage lung cancer patients after surgery, and in tailoring rehabilitation programs and psychological interventions accordingly.

Mishel’s uncertainty in Illness theory framework

Study design

The study was cross-sectional in design. The Stimulating the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist was completed (see S1 STROBE Checklist).

Setting and participants

This study included patients who underwent surgical treatment for lung cancer at a general hospital in Shanghai between January and October 2023. The study inclusion criteria were: (1) age over 18 years; (2) clinical diagnosis of early-stage primary non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Tumor node metastasis classification (TNM) I to II [ 27 , 28 ], and received video-assisted thoracic surgery; (3) recovery time after surgery was within 1 month. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy or second surgery may be required. (2) If other malignant tumors are present, they may also need to be treated. (3) Patients with severe psychological or mental disorders may not be candidates for this survey. (4) Patients with speech communication difficulties or hearing and visual impairments may require additional accommodations.

Sample size was calculated using G*Power software version 3.1.9 [ 29 ]. Calculate power analysis using F-test and linear multiple regression: fixed model, R2 increase as statistical test, and “A priori: Calculate required sample size - given alpha, power, and effect size” as type of power analysis. Cohen’s f2 = 0.15, medium effect size, α = 0.05, power (1-β) = 0.80, number of tested predictors = 8, total number of predictors = 10 as input parameters. The analysis showed that the minimum required sample size was 109 adults. Finally, the required sample size was determined to be over 120 adults with a probability of non-response rate of 10%.

Research team and data collection

The research team consisted of two nursing experts, four nursing researchers (one of whom had extensive experience in nursing psychology research), a group of clinical nurses, and several research assistants. To ensure the scientific quality and rigor of the research, the team was responsible for overseeing the quality of the project design and implementation process. Prior to conducting the formal survey, all research assistants received consistent training and evaluation to ensure consistent interpretation of questionnaire responses.

One month after surgery marks the first stage of the early recovery process for lung cancer patients and is a critical period for psychological adjustment [ 30 ]. Understanding a patient’s psychological state is critical to providing excellent medical care. During this period, patients typically need to visit the outpatient clinic for wound suture removal and dressing changes, further emphasizing the importance of postoperative recovery. Therefore, we chose this time frame for our research to gain a more comprehensive understanding of patients’ psychological well-being.

Prior to the start of the study, the hospital management and department head worked with us to provide comprehensive and standardized training to all participating investigators to ensure the reliability and consistency of the study. Research assistants rigorously screened patients based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, which were designed to ensure a representative sample of lung cancer patients in the early recovery phase.

To obtain informed consent, patients were provided with detailed information and explanations and asked to complete the questionnaire voluntarily. To accommodate the different needs and preferences of patients, we used a combination of electronic and paper questionnaires. The electronic questionnaires were administered via the Questionnaire Star platform ( https://www.wjx.cn/ ), allowing patients to scan a two-dimensional (QR) code to access the survey. For those who preferred paper questionnaires, research assistants provided physical copies and assisted with completion as needed. The questionnaire was designed with consistent instructions to ensure that patients had a full understanding of the questions. Upon completion, each questionnaire was carefully reviewed and checked for accuracy. In addition, to reduce attrition, we obtained patients’ consent to keep their contact information, which allowed us to communicate with them further and collect additional data.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the hospital ethics committee. All participants gave informed consent prior to enrollment.

Sociodemographic questionnaire

We developed a sociodemographic survey based on a literature review and expert consultation. The survey includes patient demographic data such as age, sex, residence, lifestyle, education, marital status, childbearing history, religion, insurance, economic status (annual household income), smoking habits, employment status, sources of disease information, and previous psychological counseling. Clinical case information includes physical comorbidity, clinical tumor stage, and cancer type.

Cancer-related worry

The study measured participants’ cancer-related worry using the Brief Cancer-related Worry Inventory (BCWI), which was originally designed by Hirai et al. [ 13 ] to evaluate distinct concerns and anxiety levels among individuals with cancer. For this research, we used the 2019 Chinese edition of the BCWI, as introduced and updated by He et al. [ 31 ] (see Supplementary Table 2 ). The BCWI was comprised of 16 items, which were divided into three domains: (1) future prospects, (2) physical and symptomatic problems, and (3) social and interpersonal problems. Participants were asked to assess their cancer-related worries on a scale ranging from 0 to 100. Worry severity was determined by summing the scores for each item. The higher the total score, the more intense the patient’s cancer-related worry. The BCWI provided a concise evaluation of cancer-related worries in cancer patients. With only 16 items, it was able to differentiate them from symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.96.

Symptom burden

The M.D. Anderson Symptom Assessment Scale [ 32 ] was a widely used tool for evaluating symptom burden in cancer patients. The Chinese version of MDASI-C was translated and modified by researchers at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. The questionnaire included 13 multidimensional symptom items, such as pain, fatigue, nausea, restless sleep, distress, and shortness of breath, forgetfulness, loss of appetite, lethargy, dry mouth, sadness, vomiting, and numbness. Six additional items were used to evaluate the impact of these symptoms on work, mood, walking, relationships, and daily enjoyment. Patients rated the severity of their symptoms over the past 24 h on a scale of 0 (absent) to 10 (most severe), providing a comprehensive assessment of symptom burden across multiple dimensions. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this study was 0.95.

Illness perception

The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ) was used to measure participants’ illness perception. The scale, developed by Broadbent [ 33 ], was later revised by Mei [ 34 ] to include a Chinese version. It consisted of eight items divided into cognition, emotion, and comprehension domains as well as one open-ended question (What are the three most important factors in the development of lung cancer, in order of importance? ). The study utilized a 10-point Likert scale to rank items one through eight, with a range of 0–80 points. The ninth item required an open response. A higher total score indicated a greater tendency for individuals to experience negative perceptions and perceive symptoms of illness as more severe. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale of eight scoring items was found to be 0.73.

Psychological resilience

The study measured participants’ psychological resilience using the 10-item Connor Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10), originally developed by Connor and Davidson [ 35 ], and later revised by Campbell based on CD-RISC-25. The scale was designed to assess an individual’s level of emotional resilience in a passionate environment. It comprised 10 items, rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = always). The total score ranged from 0 to 40 points, with higher scores indicating greater resilience. The study utilized the Chinese version of CD-RISC10, which was translated and revised by Ye et al. [ 36 ], to measure psychological resilience. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.96.

Coping modes

The study measured participants’ coping modes using the Medical Coping Modes Questionnaire (MCMQ), a specialized tool for measuring patient coping modes. The MCMQ was first designed by Feifel in 1987 [ 37 ] and was translated and revised into Chinese by Shen S and Jiang Q in 2000 [ 38 ]. It consisted of 20 items and three dimensions: confrontation (eight items), avoidance (seven items), and acceptance-resignation (five items). The study utilized a 4-point scoring system to evaluate coping events, with scores ranging from 1 to 4 based on the strength of each event. Eight items (1, 4, 9, 10, 12, 13, 18, and 19) were negatively scored, resulting in a total score range of 20 to 80 points. A higher score indicated a more frequent use of this coping mode. The three dimensions of this scale can be split into three scales for separate use. The reliability coefficients of the Confrontation Coping Mode Scale, Avoidance Coping Mode Scale, and Acceptance-resignation Coping Mode Scale were 0.69, 0.60, and 0.76.

Social Support

The study used the Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS) developed by Zimet [ 39 ] to assess the level of self-understanding and perceived social support in postoperative lung cancer patients. The Chinese version of the PSSS, as adapted by Chou [ 40 ], showed satisfactory reliability and validity. The 12-item scale comprised of three dimensions: family, friend, and other support, and was rated using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The scale’s total score ranged from 12 to 84, with a higher score indicating a greater subjective sense of social support received by individuals. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale in this study was 0.94.

Statistical analyses

The questionnaire was validated and double-checked before being input into Excel to ensure accuracy. Statistical analysis and processing of the questionnaire data were conducted using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) 26.0 software. All statistical tests were two-sided with a significance level of α = 0.05. The quantitative data were presented using means and standard deviations, while the qualitative data were represented by frequency distributions. The data that conforms to normal distribution was analyzed using independent sample t-test for comparison between two groups and one-way ANOVA analysis for comparison between multiple groups. Non-normal distribution data were analyzed using non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test for comparison between two groups and Kruskal-Wallis - H -Test for comparison between multiple groups. Additionally, Spearman correlation analysis was used to study the correlations among CRW, MDASI-C, BIPQ, CD-RISC-10, MCMQ, and PSSS. A hierarchical linear regression analysis was performed to identify the multidimensional factors affecting CRW. All variables significantly correlated with the outcome variable ( p < 0.05) were included in the corresponding hierarchical regression analysis. Using Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Theory as a framework, a four-step model was adopted to study the factors influencing cancer-related concerns. The model includes individual factors such as sociodemographic and disease-related data, as well as psychological resilience, stimulus frame (symptom burden, illness perception, social support, and sources of disease information), and coping modes.

In this study, 307 questionnaires were distributed (227 electronic, 80 paper). Five paper questionnaires were invalid, resulting in 302 valid questionnaires and a recovery rate of 98.37%. The participants were 302 postoperative lung cancer patients, with 36.75% male and 63.25% female, aged 18–83 years (mean age 52.73, SD 13.07). Most patients (90.07%) were married. Additional demographic and clinical information is in Table 1 .

89.07% of people had cancer-related worries after surgery and median (interquartile range, IQR) score for CRW was 380.00 (130.00, 720.00) with a range of 0-1600. 86.42% reported worry about future prospects, 84.11% worry about physical and symptomatic problems, 79.80% worry about social and interpersonal problems. Among the 16 worry items of BCWI, the highest frequency of patient worries was “About cancer itself” (80.46%), followed by “About whether cancer might get worse in the future” (79.14%); the lowest frequency concern was “about sexual issues” (44.37%). According to the average score of the items in the three dimensions of CRW, it could be seen that patients had the highest standardized score (standardized score = median score/the total score of the dimension*100%) in future prospects (30.00%), the second standardized score in physical and symptomatic problems (20.00%), and the lowest in social and interpersonal problems (15.00%) as it is shown in Table 2 .

On the total score of the CRW scale, patients’ cancer-related worry was significantly correlated with their gender ( p = 0.009) and annual family income ( p = 0.018; see Table 1 ). The results suggested that gender and annual family income were related to the level of concern patients had after developing cancer. Additionally, there was a correlation between patients who received information about their disease from the internet or applications and their level of CRW ( p = 0.024; see Table 1 ).

The correlation analysis between various scales revealed a significant correlation ( p < 0.05; see Table 3 ) between CRW and MDASI-C, BIPQ, CD-RISC-10, and two dimensions of MCMQ (excluding avoidance). It was worth noting that avoidance coping modes did not show a correlation with CRW. In addition, according to the summary of the ninth open-ended question on the BIPQ, patients believed that the main causes of lung cancer were genetics, fatigue, stress from work, family or life, negative emotions (anger, worry) and unhealthy lifestyle (diet, work and rest, smoking), environmental factors (poor air quality, secondhand smoke, cooking fumes), and new coronavirus pneumonia (including vaccination, new coronavirus infection), etc. Further stratified linear regression analysis was conducted to determine the correlation between the dependent and independent variables (Table 4 ).

Table 4 presented the results of the hierarchical linear regression analysis for CRW in early-stage lung cancer patients. First, all scales included in the hierarchical regression analysis were tested for collinearity (variance inflation factor, VIF). The average VIF value was slightly above 1, indicating that the results were acceptable [ 41 ]. Second, the core research variables were divided into four levels according to the theoretical research, and the variables included in each level were analyzed separately. Model 1 included personal characteristics as independent variables and explained 5% of the variance in CRW. The analysis identified only two variables associated with CRW: being female (compared to male) and having low income (compared to high income). In model 2, psychological resilience was identified as an individual psychological characteristic and placed in the second level, resulting in a 9% increase in explanatory power. Model 3 added the antecedents of uncertainty, including symptom burden, illness perception, social support, and source of disease information, at the third level. This significantly increased the explanatory power of the overall regression model by 53%. The addition of coping modes, specifically confrontation coping mode and acceptance-resignation coping mode, to model 4 only increased the explanatory power of the overall regression model by 1%. The overall model demonstrated a total explanatory power of 68%. In Model 4, factors that significantly correlated with CRW included middle income( β = 2.17), psychological resilience( β =-2.42), symptom burden( β = 12.62), illness perception( β = 9.17), social support( β =-3.27), and source of disease( β = 2.01), as well as confrontation coping mode ( β =-1.98) and acceptance-resignation coping mode( β = 2.77), see Table 4 .

This study analyzed data from 302 patients to investigate the clinical, demographic, and psychosocial factors that correlated with cancer-related worry in patients with early-stage lung cancer after surgery. The study extended our understanding of the specific content and relevant factors of psychological distress in post-operative patients with early-stage lung cancer, a relationship that had not been fully investigated.

The study revealed that Chinese patients with early stage lung cancer were primarily concerned about their future prospects related to the disease itself, while sexual life problems caused by cancer were of least concern. This finding was consistent with previous studies [ 42 ], but this study provided more specific information on patients’ cancer-related worries. Lung cancer was widely perceived as a serious illness by the public due to its high cancer-specific mortality rate and low survival rate after diagnosis [ 43 ]. Consequently, patients with lung cancer often experience significant psychological distress after diagnosis. Even if the tumor was successfully removed, patients might still face challenges during recovery [ 44 ]. According to Reese’s research [ 45 ], long-term survivors of lung cancer experienced mild sexual distress. They also noted that sexual distress was significantly associated with physical and emotional symptoms. Although this study found that patients were least concerned about sexual distress, it should be noted that this study was based on the early stages of recovery after cancer surgery. Due to the postoperative repair of their body and emotions, patients were primarily focused on meeting their physiological and safety needs [ 10 ]. Further validation and exploration are required as there are limited studies on sexual distress in post-operative patients with early-stage lung cancer.

This study found that gender and annual family income were associated with the CRW of early-stage lung cancer patients. Among them, women and patients from low-income families had higher CRW scores, which was similar to the results of CRW in other cancer studies [ 14 , 46 ]. The reason might be that women were more conscious about uncomfortable symptoms than men, and women were more concerned about the duration of the disease and subsequent treatment effects than men [ 47 ]. Moreover, lower annual family income might cause patients to face more financial pressure in terms of medical expenses and treatment, thereby increasing their concerns about the consequences of the disease [ 48 ]. In addition, several other studies have found that education level, smoking status, and tumor stage had an impact on cancer-related worry scores [ 14 , 47 ], but this study did not show statistical significance.

After controlling for demographic covariate factors, the study found a significant negative relationship between psychological resilience and CRW. In a study conducted by Chen et al. [ 49 ], lower levels of psychological resilience were observed in post-operative lung cancer patients, which had a direct impact on their emotional state. In the context of treatment and recovery after lung cancer surgery, medical professionals should prioritize enhancing patients’ psychological resilience. This could be achieved through psychological support and appropriate interventions to improve emotional health and quality of life.

The antecedents in the illness uncertainty theoretical framework, such as symptom burden, illness perception, social support, and sources of disease information, were shown to be significantly associated with patients’ cancer worries in this study. The theory of uncertainty in illness [ 50 ] posited that uncertainty was caused by stimulus frames, cognitive abilities, and structural providers. In this study, these antecedents corresponded to symptom burden, illness perception, social support, and sources of disease information, and they correlated with patient worry related to cancer. Patients with a high symptom burden, high illness perception, low social support, and excessive attention to disease information on the Internet were more likely to have high cancer-related concerns. Previous studies [ 40 , 51 ] have verified the relationship between symptom burden, illness perception, and social support with psychological distress in lung cancer patients. However, there have been few studies on this patient group after surgery for early-stage lung cancer, particularly based on the uncertainty theoretical framework. Additionally, when analyzing the antecedents of structured providers, we included the sources from which patients receive information about their disease, particularly statistics from medical staff and online platforms. Our study found that patients who frequently accessed disease information on the internet had higher cancer-related worry scores. This was consistent with previous qualitative studies [ 10 ] which had shown that patients often turn to the internet for disease-related knowledge due to a perceived lack of effective information from medical staff.