- Authors and Poets

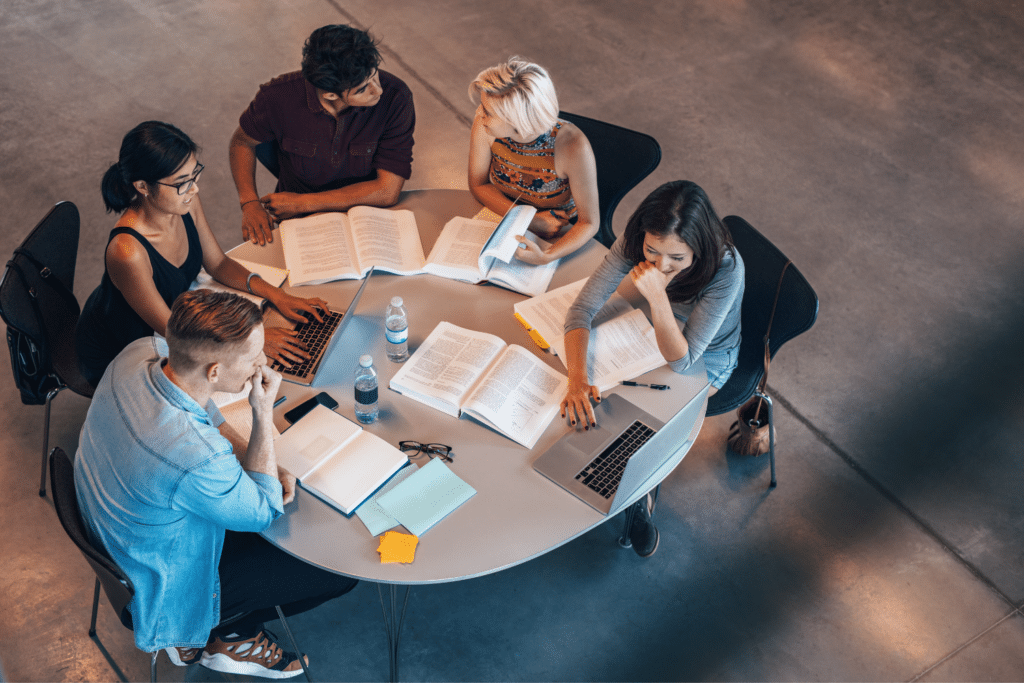

- College Students

- book lovers

- Teachers & Teaching

- Books & Movies

The eNotes Blog

Books, study tips, new features, and more—from your favorite literature experts.

- for students

How to Write an In-Class Essay: 5 Practical Tips for Success

In-class essays can be intimidating. You might even say they’re some of the hardest things you’ll have to do in an English class. You’re given a prompt, a limited amount of time, and the pressure to produce a polished essay on the spot. Even if you are a good writer, this can be daunting because of the location and time limit. But with the right preparation and mindset, you can confidently approach these assignments and score the grade you want. Here are five practical tips for writing a successful in-class essay.

1. Understand the Prompt Before You Start Writing

One of the most common mistakes students make during an in-class essay is rushing into writing without fully understanding the prompt. It’s tempting to dive in quickly, but taking a few minutes to analyze the question will save you time and frustration later.

- What is the prompt asking? Is it asking for an argument, comparison, analysis, or explanation?

- Break down key terms : Identify action words like “analyze,” “compare,” or “discuss” so you know exactly what kind of response is expected.

- Look for multiple parts : Many essay prompts contain more than one question or angle. Make sure you address every part to ensure you fully answer the prompt.

2. Plan Your Essay with a Quick Outline

In a timed setting, you may think you don’t have time to outline—but even a brief plan will keep your thoughts organized and your essay structured. Spend the first 5-10 minutes creating a basic roadmap for your essay. Here’s how:

- Write a clear thesis statement : Your thesis should directly answer the prompt and set up your main argument or point.

- Jot down your main points : Quickly list the two or three key points that will support your thesis. These will become the basis for your body paragraphs.

- Plan examples or evidence : For each point, think of at least one piece of evidence (like facts, quotes, or examples) that you can use to back up your argument.

- Decide on your conclusion : Your conclusion doesn’t have to be elaborate, but have an idea of how you will restate your thesis and wrap up your argument.

3. Start Strong with a Clear Introduction

Your introduction is the first impression your essay makes, so start strong. A clear and concise introduction will set the tone for your essay and grab your reader’s attention. In an in-class essay, keep your introduction simple but effective:

- Start with a hook : A brief, thought-provoking statement or question related to the topic can engage your reader. For example, if the prompt is about leadership, you might start with a quote or an interesting fact.

- Introduce the topic : Give some background or context for the prompt without going into too much detail. This sets up your thesis without wasting time.

- End with your thesis : State your thesis clearly, ensuring it directly answers the prompt and lays out the structure for the rest of your essay.

4. Stay Focused with Clear Body Paragraphs

When writing under pressure, it’s easy to get off track. To avoid this, structure your body paragraphs around clear, distinct points that support your thesis. Here’s how to ensure your paragraphs are effective:

- Topic sentence : Each paragraph should start with a topic sentence that clearly states the main point. This will help you stay focused and ensure each paragraph contributes to your overall argument.

- Support with evidence : After your topic sentence, provide examples or evidence that back up your point. Whether it’s a quote, statistic, or personal experience, make sure your evidence is relevant and explained clearly.

- Explain your analysis : Don’t just drop in evidence—explain why it supports your argument and how it connects to your thesis.

- Link back to the thesis : At the end of each paragraph, tie your point back to the thesis. This will help your essay feel cohesive and prevent your argument from losing direction.

5. Leave Time for a Quick Review

In-class essays are timed, but it’s important to leave at least a few minutes at the end to review your work. Even a quick review can catch simple mistakes that could otherwise hurt your grade. Here’s what to look for during your review:

- Check your thesis : Make sure your thesis is clear and that each paragraph directly supports it.

- Look for transitions : Smooth transitions between paragraphs help the essay flow logically and make it easier to read. Add connecting phrases if needed.

- Fix grammar and spelling errors : Quick fixes like correcting misspelled words or awkward phrasing can make a big difference in your essay’s polish.

- Clarify unclear sentences : If a sentence feels clunky or hard to read, simplify it for clarity. Clear, concise writing is always better than complicated or wordy sentences.

In-class essays can be stressful, but with the right approach, you can write a strong, well-organized essay that earns a good grade. Start by understanding the prompt, plan your essay with a quick outline, and write clear, focused paragraphs. Most importantly, don’t forget to leave time for a quick review to polish your work. With these five tips, you’ll be ready to tackle your next in-class essay with confidence!

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply, discover more from the enotes blog.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Would you like to explore a topic?

- LEARNING OUTSIDE OF SCHOOL

Or read some of our popular articles?

Free downloadable english gcse past papers with mark scheme.

- 19 May 2022

The Best Free Homeschooling Resources UK Parents Need to Start Using Today

- Joseph McCrossan

- 18 February 2022

How Will GCSE Grade Boundaries Affect My Child’s Results?

- Akshat Biyani

- 13 December 2021

How to Write the Perfect Essay: A Step-By-Step Guide for Students

- June 2, 2022

- What is an essay?

What makes a good essay?

Typical essay structure, 7 steps to writing a good essay, a step-by-step guide to writing a good essay.

Whether you are gearing up for your GCSE coursework submissions or looking to brush up on your A-level writing skills, we have the perfect essay-writing guide for you. 💯

Staring at a blank page before writing an essay can feel a little daunting . Where do you start? What should your introduction say? And how should you structure your arguments? They are all fair questions and we have the answers! Take the stress out of essay writing with this step-by-step guide – you’ll be typing away in no time. 👩💻

What is an essay?

Generally speaking, an essay designates a literary work in which the author defends a point of view or a personal conviction, using logical arguments and literary devices in order to inform and convince the reader.

So – although essays can be broadly split into four categories: argumentative, expository, narrative, and descriptive – an essay can simply be described as a focused piece of writing designed to inform or persuade. 🤔

The purpose of an essay is to present a coherent argument in response to a stimulus or question and to persuade the reader that your position is credible, believable and reasonable. 👌

So, a ‘good’ essay relies on a confident writing style – it’s clear, well-substantiated, focussed, explanatory and descriptive . The structure follows a logical progression and above all, the body of the essay clearly correlates to the tile – answering the question where one has been posed.

But, how do you go about making sure that you tick all these boxes and keep within a specified word count? Read on for the answer as well as an example essay structure to follow and a handy step-by-step guide to writing the perfect essay – hooray. 🙌

Sometimes, it is helpful to think about your essay like it is a well-balanced argument or a speech – it needs to have a logical structure, with all your points coming together to answer the question in a coherent manner. ⚖️

Of course, essays can vary significantly in length but besides that, they all follow a fairly strict pattern or structure made up of three sections. Lean into this predictability because it will keep you on track and help you make your point clearly. Let’s take a look at the typical essay structure:

#1 Introduction

Start your introduction with the central claim of your essay. Let the reader know exactly what you intend to say with this essay. Communicate what you’re going to argue, and in what order. The final part of your introduction should also say what conclusions you’re going to draw – it sounds counter-intuitive but it’s not – more on that below. 1️⃣

Make your point, evidence it and explain it. This part of the essay – generally made up of three or more paragraphs depending on the length of your essay – is where you present your argument. The first sentence of each paragraph – much like an introduction to an essay – should summarise what your paragraph intends to explain in more detail. 2️⃣

#3 Conclusion

This is where you affirm your argument – remind the reader what you just proved in your essay and how you did it. This section will sound quite similar to your introduction but – having written the essay – you’ll be summarising rather than setting out your stall. 3️⃣

No essay is the same but your approach to writing them can be. As well as some best practice tips, we have gathered our favourite advice from expert essay-writers and compiled the following 7-step guide to writing a good essay every time. 👍

#1 Make sure you understand the question

#2 complete background reading.

#3 Make a detailed plan

#4 Write your opening sentences

#5 flesh out your essay in a rough draft, #6 evidence your opinion, #7 final proofread and edit.

Now that you have familiarised yourself with the 7 steps standing between you and the perfect essay, let’s take a closer look at each of those stages so that you can get on with crafting your written arguments with confidence .

This is the most crucial stage in essay writing – r ead the essay prompt carefully and understand the question. Highlight the keywords – like ‘compare,’ ‘contrast’ ‘discuss,’ ‘explain’ or ‘evaluate’ – and let it sink in before your mind starts racing . There is nothing worse than writing 500 words before realising you have entirely missed the brief . 🧐

Unless you are writing under exam conditions , you will most likely have been working towards this essay for some time, by doing thorough background reading. Re-read relevant chapters and sections, highlight pertinent material and maybe even stray outside the designated reading list, this shows genuine interest and extended knowledge. 📚

#3 Make a detailed plan

Following the handy structure we shared with you above, now is the time to create the ‘skeleton structure’ or essay plan. Working from your essay title, plot out what you want your paragraphs to cover and how that information is going to flow. You don’t need to start writing any full sentences yet but it might be useful to think about the various quotes you plan to use to substantiate each section. 📝

Having mapped out the overall trajectory of your essay, you can start to drill down into the detail. First, write the opening sentence for each of the paragraphs in the body section of your essay. Remember – each paragraph is like a mini-essay – the opening sentence should summarise what the paragraph will then go on to explain in more detail. 🖊️

Next, it's time to write the bulk of your words and flesh out your arguments. Follow the ‘point, evidence, explain’ method. The opening sentences – already written – should introduce your ‘points’, so now you need to ‘evidence’ them with corroborating research and ‘explain’ how the evidence you’ve presented proves the point you’re trying to make. ✍️

With a rough draft in front of you, you can take a moment to read what you have written so far. Are there any sections that require further substantiation? Have you managed to include the most relevant material you originally highlighted in your background reading? Now is the time to make sure you have evidenced all your opinions and claims with the strongest quotes, citations and material. 📗

This is your final chance to re-read your essay and go over it with a fine-toothed comb before pressing ‘submit’. We highly recommend leaving a day or two between finishing your essay and the final proofread if possible – you’ll be amazed at the difference this makes, allowing you to return with a fresh pair of eyes and a more discerning judgment. 🤓

If you are looking for advice and support with your own essay-writing adventures, why not t ry a free trial lesson with GoStudent? Our tutors are experts at boosting academic success and having fun along the way. Get in touch and see how it can work for you today. 🎒

Popular posts

- By Guy Doza

- By Joseph McCrossan

- In LEARNING TRENDS

- By Akshat Biyani

What are the Hardest GCSEs? Should You Avoid or Embrace Them?

- By Clarissa Joshua

4 Surprising Disadvantages of Homeschooling

- By Andrea Butler

Want to try tutoring? Request a free trial session with a top tutor.

More great reads:.

Benefits of Reading: Positive Impacts for All Ages Everyday

- May 26, 2023

15 of the Best Children's Books That Every Young Person Should Read

- By Sharlene Matharu

- March 2, 2023

Ultimate School Library Tips and Hacks

- By Natalie Lever

- March 1, 2023

Book a free trial session

Sign up for your free tutoring lesson..

Celebrating 150 years of Harvard Summer School. Learn about our history.

12 Strategies to Writing the Perfect College Essay

College admission committees sift through thousands of college essays each year. Here’s how to make yours stand out.

Pamela Reynolds

When it comes to deciding who they will admit into their programs, colleges consider many criteria, including high school grades, extracurricular activities, and ACT and SAT scores. But in recent years, more colleges are no longer considering test scores.

Instead, many (including Harvard through 2026) are opting for “test-blind” admission policies that give more weight to other elements in a college application. This policy change is seen as fairer to students who don’t have the means or access to testing, or who suffer from test anxiety.

So, what does this mean for you?

Simply that your college essay, traditionally a requirement of any college application, is more important than ever.

A college essay is your unique opportunity to introduce yourself to admissions committees who must comb through thousands of applications each year. It is your chance to stand out as someone worthy of a seat in that classroom.

A well-written and thoughtful essay—reflecting who you are and what you believe—can go a long way to separating your application from the slew of forgettable ones that admissions officers read. Indeed, officers may rely on them even more now that many colleges are not considering test scores.

Below we’ll discuss a few strategies you can use to help your essay stand out from the pack. We’ll touch on how to start your essay, what you should write for your college essay, and elements that make for a great college essay.

Be Authentic

More than any other consideration, you should choose a topic or point of view that is consistent with who you truly are.

Readers can sense when writers are inauthentic.

Inauthenticity could mean the use of overly flowery language that no one would ever use in conversation, or it could mean choosing an inconsequential topic that reveals very little about who you are.

Use your own voice, sense of humor, and a natural way of speaking.

Whatever subject you choose, make sure it’s something that’s genuinely important to you and not a subject you’ve chosen just to impress. You can write about a specific experience, hobby, or personality quirk that illustrates your strengths, but also feel free to write about your weaknesses.

Honesty about traits, situations, or a childhood background that you are working to improve may resonate with the reader more strongly than a glib victory speech.

Grab the Reader From the Start

You’ll be competing with so many other applicants for an admission officer’s attention.

Therefore, start your essay with an opening sentence or paragraph that immediately seizes the imagination. This might be a bold statement, a thoughtful quote, a question you pose, or a descriptive scene.

Starting your essay in a powerful way with a clear thesis statement can often help you along in the writing process. If your task is to tell a good story, a bold beginning can be a natural prelude to getting there, serving as a roadmap, engaging the reader from the start, and presenting the purpose of your writing.

Focus on Deeper Themes

Some essay writers think they will impress committees by loading an essay with facts, figures, and descriptions of activities, like wins in sports or descriptions of volunteer work. But that’s not the point.

College admissions officers are interested in learning more about who you are as a person and what makes you tick.

They want to know what has brought you to this stage in life. They want to read about realizations you may have come to through adversity as well as your successes, not just about how many games you won while on the soccer team or how many people you served at a soup kitchen.

Let the reader know how winning the soccer game helped you develop as a person, friend, family member, or leader. Make a connection with your soup kitchen volunteerism and how it may have inspired your educational journey and future aspirations. What did you discover about yourself?

Show Don’t Tell

As you expand on whatever theme you’ve decided to explore in your essay, remember to show, don’t tell.

The most engaging writing “shows” by setting scenes and providing anecdotes, rather than just providing a list of accomplishments and activities.

Reciting a list of activities is also boring. An admissions officer will want to know about the arc of your emotional journey too.

Try Doing Something Different

If you want your essay to stand out, think about approaching your subject from an entirely new perspective. While many students might choose to write about their wins, for instance, what if you wrote an essay about what you learned from all your losses?

If you are an especially talented writer, you might play with the element of surprise by crafting an essay that leaves the response to a question to the very last sentence.

You may want to stay away from well-worn themes entirely, like a sports-related obstacle or success, volunteer stories, immigration stories, moving, a summary of personal achievements or overcoming obstacles.

However, such themes are popular for a reason. They represent the totality of most people’s lives coming out of high school. Therefore, it may be less important to stay away from these topics than to take a fresh approach.

Explore Harvard Summer School’s College Programs for High School Students

Write With the Reader in Mind

Writing for the reader means building a clear and logical argument in which one thought flows naturally from another.

Use transitions between paragraphs.

Think about any information you may have left out that the reader may need to know. Are there ideas you have included that do not help illustrate your theme?

Be sure you can answer questions such as: Does what you have written make sense? Is the essay organized? Does the opening grab the reader? Is there a strong ending? Have you given enough background information? Is it wordy?

Write Several Drafts

Set your essay aside for a few days and come back to it after you’ve had some time to forget what you’ve written. Often, you’ll discover you have a whole new perspective that enhances your ability to make revisions.

Start writing months before your essay is due to give yourself enough time to write multiple drafts. A good time to start could be as early as the summer before your senior year when homework and extracurricular activities take up less time.

Read It Aloud

Writer’s tip : Reading your essay aloud can instantly uncover passages that sound clumsy, long-winded, or false.

Don’t Repeat

If you’ve mentioned an activity, story, or anecdote in some other part of your application, don’t repeat it again in your essay.

Your essay should tell college admissions officers something new. Whatever you write in your essay should be in philosophical alignment with the rest of your application.

Also, be sure you’ve answered whatever question or prompt may have been posed to you at the outset.

Ask Others to Read Your Essay

Be sure the people you ask to read your essay represent different demographic groups—a teacher, a parent, even a younger sister or brother.

Ask each reader what they took from the essay and listen closely to what they have to say. If anyone expresses confusion, revise until the confusion is cleared up.

Pay Attention to Form

Although there are often no strict word limits for college essays, most essays are shorter rather than longer. Common App, which students can use to submit to multiple colleges, suggests that essays stay at about 650 words.

“While we won’t as a rule stop reading after 650 words, we cannot promise that an overly wordy essay will hold our attention for as long as you’d hoped it would,” the Common App website states.

In reviewing other technical aspects of your essay, be sure that the font is readable, that the margins are properly spaced, that any dialogue is set off properly, and that there is enough spacing at the top. Your essay should look clean and inviting to readers.

End Your Essay With a “Kicker”

In journalism, a kicker is the last punchy line, paragraph, or section that brings everything together.

It provides a lasting impression that leaves the reader satisfied and impressed by the points you have artfully woven throughout your piece.

So, here’s our kicker: Be concise and coherent, engage in honest self-reflection, and include vivid details and anecdotes that deftly illustrate your point.

While writing a fantastic essay may not guarantee you get selected, it can tip the balance in your favor if admissions officers are considering a candidate with a similar GPA and background.

Write, revise, revise again, and good luck!

Experience life on a college campus. Spend your summer at Harvard.

Explore Harvard Summer School’s College Programs for High School Students.

About the Author

Pamela Reynolds is a Boston-area feature writer and editor whose work appears in numerous publications. She is the author of “Revamp: A Memoir of Travel and Obsessive Renovation.”

How Involved Should Parents and Guardians Be in High School Student College Applications and Admissions?

There are several ways parents can lend support to their children during the college application process. Here's how to get the ball rolling.

Harvard Division of Continuing Education

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) at Harvard University is dedicated to bringing rigorous academics and innovative teaching capabilities to those seeking to improve their lives through education. We make Harvard education accessible to lifelong learners from high school to retirement.

Preparing for an in-class essay

Danielle Barakat

Community Manager at Atomi

This is a bit of a lengthy one so strap yourselves in.

We have focused a lot of our time looking at how to prepare for exams and how to study or write notes, but we haven’t really had a look at how to prepare for something like an in-class essay. These are a little different because they’re not exactly a full-blown exam but are still a legit assessment that you need to know how to study for.

Everyone has a slightly different approach to this: Do you memorise the whole essay beforehand or do you just know themes and quotes and construct the essay on the day?

Personal opinion: I always liked going in with a pre-prepared essay, but one that was able to change and mould depending on the question. The thing is you need to be prepared at least 3 weeks in advance if you’re going to pick this option and I’ll explain why in a second.

That being said, we’re going to use this article to dive into how you would go about preparing for an in-class essay, no matter which method you use.

1. Start 3 weeks before

Being organised for these assessments is your key to doing well, so it’s important to start collecting your themes, quotes and ideas at least 3 weeks before so that you have enough time to formulate a structured response, have your teacher read over your drafts and give you feedback as well as practise. The essay you write 3 weeks out is not going to be the same essay you write in your assessment - and this is what we want.

This is probably considered the hardest step because it involves actually formulating a thesis and writing the bulk of your essay. But how do you actually do this?

Well, it comes down to personal preference and the way you like to write. Some people like to follow the PEEL structure of essay writing where you break your paragraphs down in order to include:

- Point or topic sentence

- Explanation

- Link sentence

I find this a really good foundation to write your essays because it makes sure you have a solid and succinct overall structure. But it doesn’t stop there. You need to repeat these steps a couple of times per paragraph to get some good quality essay writing. We’ve written a whole post on how to use this essay structure, so check that out here if you’re still a little unsure.

Now that you’ve got the basic structure of your essay down, how do you push the essay up into the band 6 range?

I’ve asked our resident English content creators here at Atomi and here are the 3 things they recommend doing to ensure your essay reaches those higher bands:

a) Start off with a strong introduction

It’s super important that your intro has a very clear thesis and that the points you are planning to address in your essay are clearly outlined from the very beginning. This will prove to the marker that you have a clear understanding of your essay as a whole and that you are completely aware of the points you have to address in order to back up your thesis. You then have to make sure that the body of your essay clearly links to every point made in the introduction. If you follow a good structure, it will be easy to make sure that your paragraphs are doing this, which brings me to my next point...

b) Focus on your sentence structure to ensure you are analysing your evidence properly

But how do you do this?

We recommend the technique - verb - effect method. The reason we use this sentence structure is because it allows you to analyse how the composer has chosen specific techniques in order to teach the audience something.

Let me quickly break down how to actually construct sentences using this method:

- Technique - This one is pretty straight forward. You need to first identify the technique used by the composer, e.g. metaphor or symbolism.

- Verb - This is where you clarify what the technique is actually doing for the audience. For example, does it highlight, contrast or undermine a certain idea or notion?

- Effect - This is probably the most important part of the sentence where you explain the impact this technique has on the audience. Does this technique allow you to prove your topic sentence or thesis, and how? This is where you create a link back to the main idea you’re focusing on in that paragraph.

A few of these per paragraph and you’ll be on your way to a band 6 essay. We go through some example paragraphs using this method in our English: How to Write an Essay video series. Check out the Sentences and Logic videos 😊.

c) Make sure you have a diverse range of evidence and related texts

Don’t just stick to the same old techniques of metaphor or simile. You need to be able to analyse the texts at a higher level in order to push your essay into the high band 5/band 6 range. This means diving deeper into the text and trying to find other forms of evidence that make your essay stronger. The same goes for related texts. Try experimenting with a more diverse range of related texts, for example, a poem instead of a movie or novel. This will prove to the marker that you have a more in-depth understanding of the meaning of the texts and that you are able to establish meaning in various ways in order to prove the point you’re arguing in your essay.

You now have the first draft of your essay. It’s time to send this through to your teacher for them to read and provide you with some feedback.

2. Re-work it

The next step comes after your teacher has sent you back their feedback on your essay. This step is important because your teachers are going to be the ones marking your in-class assessment, so their feedback will give you insights into what they’re expecting. Take what they're saying seriously and re-work your essay to implement their feedback as much as you can.

The process of handing your work in for marking, getting feedback and then re-working it should happen multiple times, not just once. This is how you can get your essay close to perfect.

3. Memorise

Once you have your essay as close to perfect as you can, you should still be about a week out from the assessment. It’s now time to start memorising your essay. Some of you may be shocked that you’re memorising this far out, but the memorising that’s happening now is important for practise purposes. You want to be able to know your essay enough so that you can do some practise questions closed book.

When it comes to memorising, everyone has their own way that works for them. For me, walking around my room saying my essays out loud, paragraph by paragraph until I remembered the whole thing was the only thing that worked. Some people find it easier to write out their essay over and over, but the thing about this is that it takes a lot longer and isn’t as efficient.

For a guide on exactly how to memorise long responses, check this out !

4. Practise

So you now have your essay written and memorised. Well done! But here’s where a lot of people go wrong because they go into the assessment and just regurgitate their memorised essay without changing it. This is bad. Don’t do this.

This is the number 1 mistake you can make because your teachers and markers will pick up on this instantly because it will be obvious that you haven’t explicitly answered the question.

Practise questions will help overcome this. Get your hands on as many practise questions as possible and give them a go. Start off doing them not under exam conditions. Have your pre-prepared essay in front you and work on moulding your essay and specifically answering the question. Hand these into your teacher for feedback and work with the feedback on your next attempt.

Once you feel confident with this, the next step is to introduce exam conditions so that you can practise moulding your essay in a high pressured environment where you’re relying on your memory rather than a cheat sheet. I would even go to the extent of writing out multiple exam questions, folding them up and then picking them out of a hat when you go to practise so that you can test your ability to answer an unseen question - one that you haven’t had prior time to think about, because after all, that’s what the in-class assessment will be like. Doing this also allows you to test your timing to know whether you can write your essay in the given time slot.

5. The night before the assessment

The night before is finally here. You are now ready. You’ve got your essay, you’ve received feedback from your teacher, you’ve made the amendments, you’ve practised it under exam conditions.

So what now?

Here’s what I would recommend doing:

- Re-read your essay and make sure you’ve got it fully memorised;

- Write it out under exam conditions (whilst timing yourself) one more time;

- Read through your essay one more time;

- Sleep early.

The next morning, make sure you have a good breakfast and then if you’re keen write your essay out one more time (this one’s optional).

You’re now ready to sit an in-class essay assessment.

Good luck! 💪

Published on

February 19, 2019

Recommended reads

How to make a personalised study timetable

How to use Atomi’s 2024 study plans and timetables

Why you need a study plan ahead of your exams

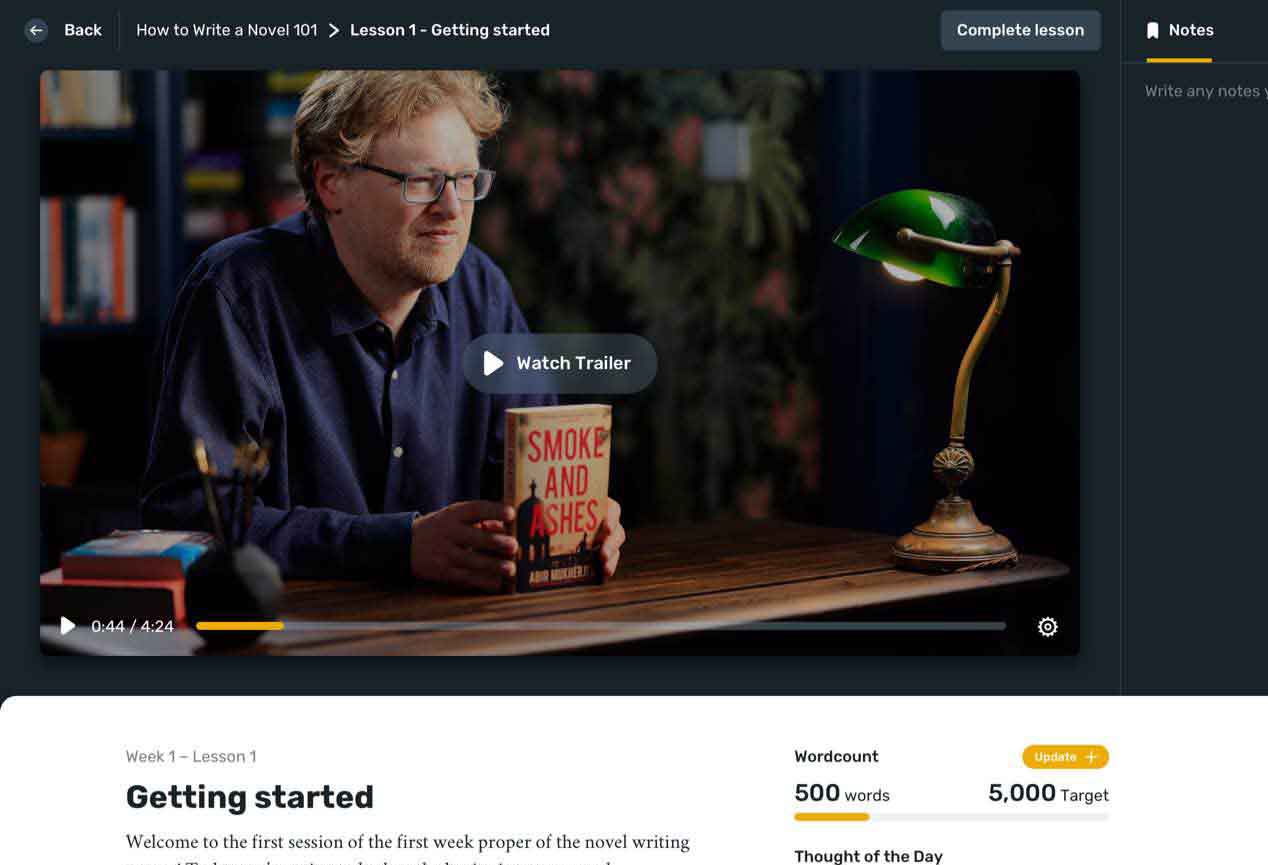

What's atomi.

Engaging, curriculum-specific videos and interactive lessons backed by research, so you can study smarter, not harder.

With tens of thousands of practice questions and revision sessions, you won’t just think you’re ready. You’ll know you are!

Study skills strategies and tips, AI-powered revision recommendations and progress insights help you stay on track.

Short, curriculum-specific videos and interactive content that’s easy to understand and backed by the latest research.

Active recall quizzes, topic-based tests and exam practice enable students to build their skills and get immediate feedback.

Our AI understands each student's progress and makes intelligent recommendations based on their strengths and weaknesses.

Tips for Writing In-Class Essay Exams: Ace Timed Essay Tests

In-class essay exams are significant in the college grading methodology. These exams test your knowledge, understanding of study material, and ability to explain your knowledge in a specific duration. Doing well in these exams will improve your grades and overall academics. Students learn how to manage time and be precise in these time-bound tasks. These learnings will play a role in your future projects.

In-class essay exams are time-bound tasks, and you must finish them quickly and with quality to score good grades.

This article will present practical tips for writing in-class essay exams quickly and accurately. You will find actionable tips on how to prepare before the exam, practice answering, and manage your time to express the main point with specific evidence. Keep reading.

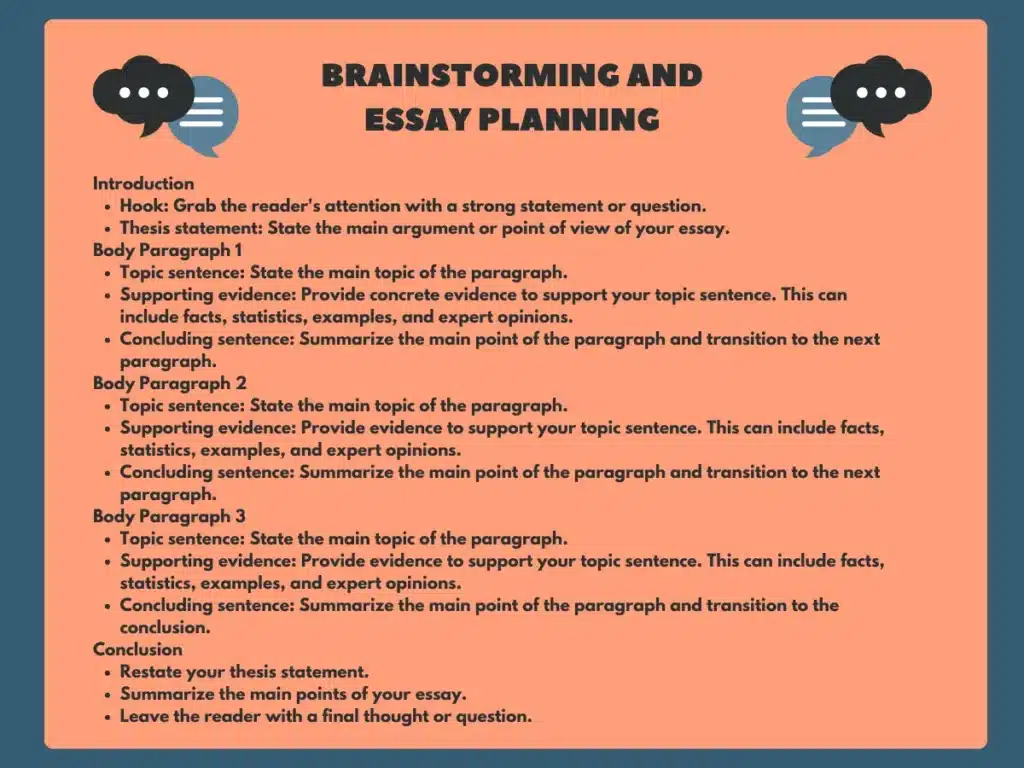

Writing a college essay involves several key steps. Start by understanding the essay prompt and brainstorming ideas. Create an outline to organize your thoughts and structure the essay logically. Craft a compelling introduction that grabs the reader’s attention, followed by body paragraphs that support your main points with evidence and examples. Ensure each paragraph flows coherently and relates back to the thesis statement. Conclude by summarizing your main arguments and reinforcing the essay’s significance. Finally, revise and edit for clarity, coherence, and grammar before submitting.

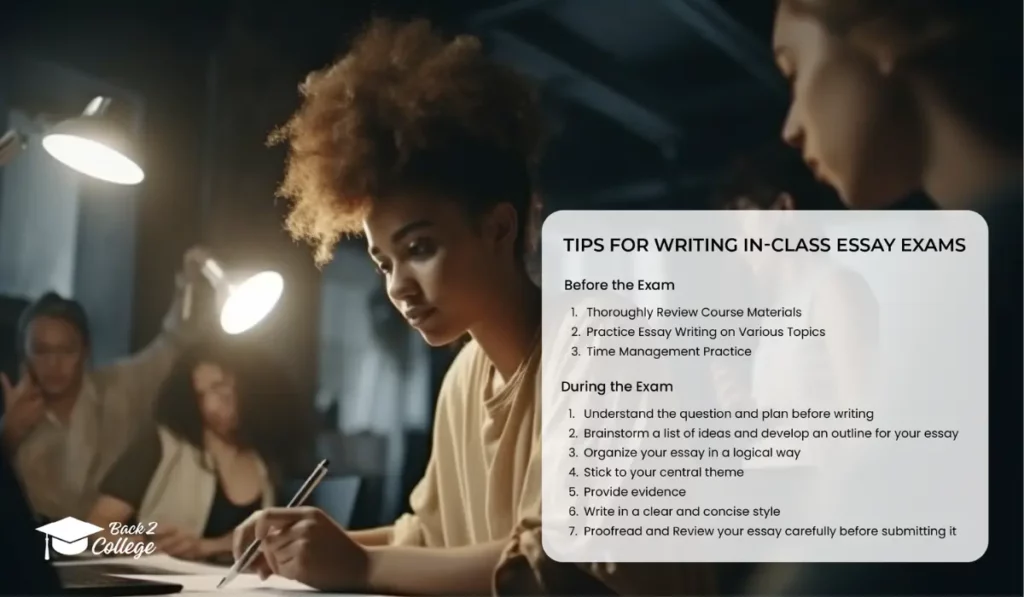

Before the Exam

Exam preparation is essential for success. By taking the time to prepare before the exam, you can increase your chances of doing well.

Here are three key tips for preparation before an in-class essay test:

1. Thoroughly Review Course Materials

Before the exam, make sure to carefully go through your course materials. This step is essential to become well-acquainted with the critical concepts and ideas that the exam might cover. Take the time to revisit your class notes, textbooks, and any relevant readings. This foundational knowledge will serve as the backbone for your essay responses.

2. Practice Essay Writing on Various Topics

To enhance your essay-writing skills, engage in practicing essays on a range of topics. This practice not only hones your ability to express ideas clearly but also helps you understand how to structure an essay effectively. Consider addressing diverse essay prompts and experimenting with different writing styles. This practice will make you more versatile in approaching essay questions during the exam.

3. Time Management Practice

Efficient time management is of utmost importance during an in-class essay exam. To excel in this area, it’s crucial to time yourself while practicing essay writing.

Establish realistic time limits for each phase of the essay-writing process: brainstorming, outlining, drafting, and proofreading. By mastering the art of allocating your time effectively, you ensure that you can successfully complete your essays within the confines of the exam’s time constraints.

Maintain a timer during your practice sessions to instill a sense of time-bound tasks. This will familiarize you with the entire process, making in-class essay writing second nature. Additionally, through consistent practice, you’ll stay composed and collected during the actual exam.

By following these three essential preparation tips, you’ll be well-prepared to tackle in-class essay exams with confidence and skill.

During the Exam

Once you have arrived for the exam, it is important to stay calm and focused. Take a few deep breaths and remind yourself that you are prepared.

Here are some tips for what to do during the exam:

1. Understand the question and plan before writing

Read the question carefully and understand the main topic and what it is asking you. Identify key words like “discuss,” “explain,” “compare,” or “prove” to know the intent of the question. Plan your answer once you understand the question. Create an outline for the answer and choose the main points that you will present and discuss. Arrange the points to ensure the logical flow of the answer so that your teacher can easily follow it.

2. Brainstorm a list of ideas and develop an outline for your essay.

To excel in in-class essay exams, it’s vital to master the art of brainstorming and crafting a structured outline. Begin by reading the prompt carefully to understand what’s required. Then, brainstorm a list of ideas related to the prompt. Group them to find common themes, and select the most relevant ones that align with the prompt.

Your outline acts as a blueprint, showing how your ideas will be organized and support your thesis. Remember, keep the essay prompt’s key words in mind for relevance. Familiarize yourself with various essay types, and practice with different prompts to refine your skills.

To brainstorm a list of ideas and develop an outline for your in-class essay exams, follow these steps:

- Analyze the prompt carefully, identifying key concepts and important ideas.

- Pick a topic you understand and find interesting for a smooth answering process.

- Brainstorm ideas related to the prompt without worrying about completeness.

- Group ideas with common themes or connections.

- Select the most relevant ideas, guided by the essay prompt.

- Use prompt keywords for focus and relevance.

- Be aware of different essay types for effective brainstorming and outlining.

- Practice with various prompts to refine your skills and gain comfort with the process.

Once you have a list of ideas and have organized them into groups, you can begin to develop an outline for your essay. Your outline should show how your ideas will be organized and how they will support your thesis statement.

Here is a simple outline template that you can use:

This is just a basic outline template, of course. You may need to adjust it to fit the specific essay question that you are being asked. But by following these tips, you can brainstorm and outline a clear, concise, and well-organized in-class essay.

3. Organize your essay in a logical way

In crafting a well-structured essay, several strategies can be employed for a logical flow. Here are some valuable tips:

- Choose an Organizational Pattern : Selecting an organizational pattern is crucial. Common options include:

- Chronological Order: This arranges your essay in the order of events. Use words like “first,” “second,” “next,” “then,” and “finally” to maintain the chronological flow.

- Spatial Order: Structure your essay based on location, utilizing terms like “above,” “below,” “beyond,” “behind,” “beside,” “between,” “in front of,” and “on top of.”

- Cause and Effect Order: Organize your essay by explaining causes or effects. Employ phrases like “because,” “as a result,” “therefore,” “consequently,” and “thus.”

- Problem-Solution Order: Identify a problem and propose a solution. Use words such as “first,” “second,” “next,” “then,” and “finally” for this structure.

- Compare and Contrast Order: Analyze and contrast two or more things. Include terms like “similarly,” “differently,” “on the other hand,” “in contrast,” and “however.”

Once you’ve made your choice, stick with it throughout your essay. Consistency in organization ensures a smooth, reader-friendly flow.

- Craft a Clear Thesis Statement : Your thesis statement is the central argument of your essay. It should be concise, clear, and open to debate. Place it in the introduction and support it with evidence in the body paragraph of your essay.

- Utilize Topic Sentences : Every paragraph should begin with a topic sentence, which encapsulates the main idea. These sentences should be reinforced with evidence within the paragraphs.

- Employ Concluding Sentences : A concluding sentence should sum up the primary idea of a paragraph and smoothly transition to the next one.

4. Stick to your central theme

Stick to your main points of the answer. Do not deviate from them and start giving different and irrelevant arguments. Support your ideas and argument with explanations, examples, and any case study. Your in-class essay must be focused on the central theme and present supporting ideas and concepts around that theme. Irrelevant ideas and concepts may dilute the context and logic of the answer and make it harder to follow.

5. Provide evidence

Provide evidence for your claims, thesis, and ideas. Supporting your ideas with evidence gains the trust of the teacher and increases the chances of better grades. Claims without concrete evidence look bluff and irrelevant to the question. Your arguments, thesis, and ideas will look hollow, vague, and unestablished without supporting evidence.

6. Write in a clear and concise style

To craft an essay with precision and brevity, consider these invaluable pointers:

- Trim Excess Phrases : Begin by removing superfluous wording. Employ plain language to express your thoughts. Favor the active voice and reduce wordiness. Avoid commencing sentences with “there is,” “there are,” or “it is,” and cut down on redundant nouns and filler words like “that,” “of,” or “up.”

- Keep It Simple : Opt for straightforward language and shun complexity. Leave out jargon and intricate sentences in favor of clarity and directness.

- Detail Is Key : Provide specific and vivid descriptions. Avoid vague or general language and enhance your writing with rich details.

- Conciseness Is King : Get to the point without delay and minimize excess words and phrases. Clarity often emerges from brevity.

- Activate Your Voice : Employ the active voice, which is concise and direct compared to the passive voice.

- Diversify Sentence Structure : Don’t rely on repetitive sentence structures. Vary your construction to keep your readers engaged.

Here are some specific examples to illustrate these principles:

- Instead of, “The aforementioned individual was in possession of a canine specimen,” say, “The man had a dog.”

- Rather than stating, “The car was fast,” express, “The car could reach speeds exceeding 100 miles per hour.”

- For conciseness, transform, “The reason why I am writing this letter is to inform you that I am resigning from my position” into “I am resigning from my position.”

Additionally, here are some extra tips to elevate your writing:

- Read your work aloud to spot awkward or unclear sentences.

- Consider using a recognized style guide like the Chicago Manual of Style, Associated Press Stylebook, or MLA Style Manual for detailed writing guidelines.

7. Proofread and Review your essay carefully before submitting it

Review your answer for any grammatical errors, irrelevant arguments, ideas, or thesis, and evidence-less claims. Check if the logical flow of the answer is clear. Revise any point or idea that is ambiguous and unclear. Add further clarifications to the ideas and thesis if needed. Remove texts that are irrelevant and vague to provide more clarity.

Proofreading writing assignments involves carefully reviewing your work for errors in spelling, grammar, punctuation, and syntax. It also includes checking for clarity, coherence, and consistency in ideas and arguments. Take time away from the document before proofreading to approach it with fresh eyes. Read the text aloud or use proofreading tools to catch mistakes. Focus on one type of error at a time to ensure thoroughness. Lastly, consider seeking feedback from peers or professors for an additional perspective on your work.

Bonus tips for writing in class essay test questions

- Incorporate the essay prompt’s keywords into your essay to demonstrate your comprehension of the question and direct address.

- Ensure you respond comprehensively to all facets of the exam questions. If it requires multiple actions like analysis, comparison, and contrast, tackle each in your essay.

- Don’t hesitate to assert your perspective. In in-class essay exams, seize the opportunity to showcase your knowledge and critical thinking.

- If you encounter a roadblock, take a deep breath and move forward to the next segment of your essay. You can always return to the challenging part later.

- Be prudent with your time. Avoid excessive focus on any single section of the essay. If time is running short, prioritize completing your conclusion.

A college writing center is a valuable resource that provides students with guidance and support for their writing assignments. It typically offers services such as one-on-one consultations with writing tutors who help students at various stages of the writing process, from brainstorming ideas to polishing final drafts. Writing centers also assist with improving writing skills, refining grammar and style, structuring essays, and citing sources correctly. They are designed to support students in enhancing their writing abilities and producing high-quality academic work.

Final Thoughts

Mastering and practicing the tips for writing in-class essay exams is crucial for every student aiming for better grades and academics. By following tips like understanding the question, outlining the answer, and providing evidence to your claims, a student can improve the quality of the answer.

Practicing writing in-class essays regularly can improve writing speed. Lastly, by reviewing the answer, you can ensure the quality of the answer.

8 Life Skills Needed to Succeed in College And Career

Mastering the Writing Process

Related Articles

How to Study Effectively: Best Strategies to Maximize Your Study Time

The Best Online Degree Programs: Some Of Our Favorite Accredited Schools

The Best Online Colleges for Adult Learners: Accredited and Ready for You

Latest articles.

Future-Proof Your Career: Best Online Degree Programs for 2024

How to Choose the Right Degree Program: Top Tips for Success

The Best Online Master’s Degree Programs for 2024: Top-Rated Picks

3324 E Ray Rd #905 (PO Box 905) Higley, AZ 85236

PH +1 (650) 429-8971

© 2024 Back2college.com

Ultimate Guide to Writing Your College Essay

Tips for writing an effective college essay.

College admissions essays are an important part of your college application and gives you the chance to show colleges and universities your character and experiences. This guide will give you tips to write an effective college essay.

Want free help with your college essay?

UPchieve connects you with knowledgeable and friendly college advisors—online, 24/7, and completely free. Get 1:1 help brainstorming topics, outlining your essay, revising a draft, or editing grammar.

Writing a strong college admissions essay

Learn about the elements of a solid admissions essay.

Avoiding common admissions essay mistakes

Learn some of the most common mistakes made on college essays

Brainstorming tips for your college essay

Stuck on what to write your college essay about? Here are some exercises to help you get started.

How formal should the tone of your college essay be?

Learn how formal your college essay should be and get tips on how to bring out your natural voice.

Taking your college essay to the next level

Hear an admissions expert discuss the appropriate level of depth necessary in your college essay.

Student Stories

Student Story: Admissions essay about a formative experience

Get the perspective of a current college student on how he approached the admissions essay.

Student Story: Admissions essay about personal identity

Get the perspective of a current college student on how she approached the admissions essay.

Student Story: Admissions essay about community impact

Student story: admissions essay about a past mistake, how to write a college application essay, tips for writing an effective application essay, sample college essay 1 with feedback, sample college essay 2 with feedback.

This content is licensed by Khan Academy and is available for free at www.khanacademy.org.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.3 Becoming a Successful College Writer

Learning objectives.

- Identify strategies for successful writing.

- Demonstrate comprehensive writing skills.

- Identify writing strategies for use in future classes.

In the preceding sections, you learned what you can expect from college and identified strategies you can use to manage your work. These strategies will help you succeed in any college course. This section covers more about how to handle the demands college places upon you as a writer. The general techniques you will learn will help ensure your success on any writing task, whether you complete a bluebook exam in an hour or an in-depth research project over several weeks.

Putting It All Together: Strategies for Success

Writing well is difficult. Even people who write for a living sometimes struggle to get their thoughts on the page. Even people who generally enjoy writing have days when they would rather do anything else. For people who do not like writing or do not think of themselves as good writers, writing assignments can be stressful or even intimidating. And of course, you cannot get through college without having to write—sometimes a lot, and often at a higher level than you are used to.

No magic formula will make writing quick and easy. However, you can use strategies and resources to manage writing assignments more easily. This section presents a broad overview of these strategies and resources. The remaining chapters of this book provide more detailed, comprehensive instruction to help you succeed at a variety of assignments. College will challenge you as a writer, but it is also a unique opportunity to grow.

Using the Writing Process

To complete a writing project successfully, good writers use some variation of the following process.

The Writing Process

- Prewriting. In this step, the writer generates ideas to write about and begins developing these ideas.

- Outlining a structure of ideas. In this step, the writer determines the overall organizational structure of the writing and creates an outline to organize ideas. Usually this step involves some additional fleshing out of the ideas generated in the first step.

- Writing a rough draft. In this step, the writer uses the work completed in prewriting to develop a first draft. The draft covers the ideas the writer brainstormed and follows the organizational plan that was laid out in the first step.

- Revising. In this step, the writer revisits the draft to review and, if necessary, reshape its content. This stage involves moderate and sometimes major changes: adding or deleting a paragraph, phrasing the main point differently, expanding on an important idea, reorganizing content, and so forth.

- Editing. In this step, the writer reviews the draft to make additional changes. Editing involves making changes to improve style and adherence to standard writing conventions—for instance, replacing a vague word with a more precise one or fixing errors in grammar and spelling. Once this stage is complete, the work is a finished piece and ready to share with others.

Chances are, you have already used this process as a writer. You may also have used it for other types of creative projects, such as developing a sketch into a finished painting or composing a song. The steps listed above apply broadly to any project that involves creative thinking. You come up with ideas (often vague at first), you work to give them some structure, you make a first attempt, you figure out what needs improving, and then you refine it until you are satisfied.

Most people have used this creative process in one way or another, but many people have misconceptions about how to use it to write. Here are a few of the most common misconceptions students have about the writing process:

- “I do not have to waste time on prewriting if I understand the assignment.” Even if the task is straightforward and you feel ready to start writing, take some time to develop ideas before you plunge into your draft. Freewriting —writing about the topic without stopping for a set period of time—is one prewriting technique you might try in that situation.

- “It is important to complete a formal, numbered outline for every writing assignment.” For some assignments, such as lengthy research papers, proceeding without a formal outline can be very difficult. However, for other assignments, a structured set of notes or a detailed graphic organizer may suffice. The important thing is that you have a solid plan for organizing ideas and details.

- “My draft will be better if I write it when I am feeling inspired.” By all means, take advantage of those moments of inspiration. However, understand that sometimes you will have to write when you are not in the mood. Sit down and start your draft even if you do not feel like it. If necessary, force yourself to write for just one hour. By the end of the hour, you may be far more engaged and motivated to continue. If not, at least you will have accomplished part of the task.

- “My instructor will tell me everything I need to revise.” If your instructor chooses to review drafts, the feedback can help you improve. However, it is still your job, not your instructor’s, to transform the draft to a final, polished piece. That task will be much easier if you give your best effort to the draft before submitting it. During revision, do not just go through and implement your instructor’s corrections. Take time to determine what you can change to make the work the best it can be.

- “I am a good writer, so I do not need to revise or edit.” Even talented writers still need to revise and edit their work. At the very least, doing so will help you catch an embarrassing typo or two. Revising and editing are the steps that make good writers into great writers.

For a more thorough explanation of the steps of the writing process as well as for specific techniques you can use for each step, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

The writing process also applies to timed writing tasks, such as essay exams. Before you begin writing, read the question thoroughly and think about the main points to include in your response. Use scrap paper to sketch out a very brief outline. Keep an eye on the clock as you write your response so you will have time to review it and make any needed changes before turning in your exam.

Managing Your Time

In Section 1.2 “Developing Study Skills” , you learned general time-management skills. By combining those skills with what you have learned about the writing process, you can make any writing assignment easier to manage.

When your instructor gives you a writing assignment, write the due date on your calendar. Then work backward from the due date to set aside blocks of time when you will work on the assignment. Always plan at least two sessions of writing time per assignment, so that you are not trying to move from step 1 to step 5 in one evening. Trying to work that fast is stressful, and it does not yield great results. You will plan better, think better, and write better if you space out the steps.

Ideally, you should set aside at least three separate blocks of time to work on a writing assignment: one for prewriting and outlining, one for drafting, and one for revising and editing. Sometimes those steps may be compressed into just a few days. If you have a couple of weeks to work on a paper, space out the five steps over multiple sessions. Long-term projects, such as research papers, require more time for each step.

In certain situations you may not be able to allow time between the different steps of the writing process. For instance, you may be asked to write in class or complete a brief response paper overnight. If the time available is very limited, apply a modified version of the writing process (as you would do for an essay exam). It is still important to give the assignment thought and effort. However, these types of assignments are less formal, and instructors may not expect them to be as polished as formal papers. When in doubt, ask the instructor about expectations, resources that will be available during the writing exam, and if they have any tips to prepare you to effectively demonstrate your writing skills.

Each Monday in Crystal’s Foundations of Education class, the instructor distributed copies of a current news article on education and assigned students to write a one-and-one-half- to two-page response that was due the following Monday. Together, these weekly assignments counted for 20 percent of the course grade. Although each response took just a few hours to complete, Crystal found that she learned more from the reading and got better grades on her writing if she spread the work out in the following way:

| MONDAY | TUESDAY | WEDNESDAY | THURSDAY | FRIDAY | SATURDAY | SUNDAY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article response assigned. | Read article, prewrite, and outline response paper. | Draft response. | Revise and edit response. |

For more detailed guidelines on how to plan for a long-term writing project, see Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” .

Setting Goals

One key to succeeding as a student and as a writer is setting both short- and long-term goals for yourself. You have already glimpsed the kind of short-term goals a student might set. Crystal wanted to do well in her Foundations of Education course, and she realized that she could control how she handled her weekly writing assignments. At 20 percent of her course grade, she reasoned, those assignments might mean the difference between a C and a B or between a B and an A.

By planning carefully and following through on her daily and weekly goals, Crystal was able to fulfill one of her goals for the semester. Although her exam scores were not as high as she had hoped, her consistently strong performance on writing assignments tipped her grade from a B+ to an A−. She was pleased to have earned a high grade in one of the required courses for her major. She was also glad to have gotten the most out of an introductory course that would help her become an effective teacher.

How does Crystal’s experience relate to your own college experience?

To do well in college, it is important to stay focused on how your day-to-day actions determine your long-term success. You may not have defined your career goals or chosen a major yet. Even so, you surely have some overarching goals for what you want out of college: to expand your career options, to increase your earning power, or just to learn something new. In time, you will define your long-term goals more explicitly. Doing solid, steady work, day by day and week by week, will help you meet those goals.

In this exercise, make connections between short- and long-term goals.

- For this step, identify one long-term goal you would like to have achieved by the time you complete your degree. For instance, you might want a particular job in your field or hope to graduate with honors.

- Next, identify one semester goal that will help you fulfill the goal you set in step one. For instance, you may want to do well in a particular course or establish a connection with a professional in your field.

- Review the goal you determined in step two. Brainstorm a list of stepping stones that will help you meet that goal, such as “doing well on my midterm and final exams” or “talking to Professor Gibson about doing an internship.” Write down everything you can think of that would help you meet that semester goal.

- Review your list. Choose two to three items, and for each item identify at least one concrete action you can take to accomplish it. These actions may be recurring (meeting with a study group each week) or one time only (calling the professor in charge of internships).

- Identify one action from step four that you can do today. Then do it.

Using College Resources

One reason students sometimes find college overwhelming is that they do not know about, or are reluctant to use, the resources available to them. Some aspects of college will be challenging. However, if you try to handle every challenge alone, you may become frustrated and overwhelmed.

Universities have resources in place to help students cope with challenges. Your student fees help pay for resources such as a health center or tutoring, so use these resources if you need them. The following are some of the resources you might use if you find you need help:

- Your instructor. If you are making an honest effort but still struggling with a particular course, set up a time to meet with your instructor and discuss what you can do to improve. He or she may be able to shed light on a confusing concept or give you strategies to catch up.

- Your academic counselor. Many universities assign students an academic counselor who can help you choose courses and ensure that you fulfill degree and major requirements.

- The academic resource center. These centers offer a variety of services, which may range from general coaching in study skills to tutoring for specific courses. Find out what is offered at your school and use the services that you need.

- The writing center. These centers employ tutors to help you manage college-level writing assignments. They will not write or edit your paper for you, but they can help you through the stages of the writing process. (In some schools, the writing center is part of the academic resource center.)

- The career resource center. Visit the career resource center for guidance in choosing a career path, developing a résumé, and finding and applying for jobs.

- Counseling services. Many universities offer psychological counseling for free or for a low fee. Use these services if you need help coping with a difficult personal situation or managing depression, anxiety, or other problems.

Students sometimes neglect to use available resources due to limited time, unwillingness to admit there is a problem, or embarrassment about needing to ask for help. Unfortunately, ignoring a problem usually makes it harder to cope with later on. Waiting until the end of the semester may also mean fewer resources are available, since many other students are also seeking last-minute help.

Identify at least one college resource that you think could be helpful to you and you would like to investigate further. Schedule a time to visit this resource within the next week or two so you can use it throughout the semester.

Overview: College Writing Skills

You now have a solid foundation of skills and strategies you can use to succeed in college. The remainder of this book will provide you with guidance on specific aspects of writing, ranging from grammar and style conventions to how to write a research paper.

For any college writing assignment, use these strategies:

- Plan ahead. Divide the work into smaller, manageable tasks, and set aside time to accomplish each task in turn.

- Make sure you understand the assignment requirements, and if necessary, clarify them with your instructor. Think carefully about the purpose of the writing, the intended audience, the topics you will need to address, and any specific requirements of the writing form.

- Complete each step of the writing process. With practice, using this process will come automatically to you.

- Use the resources available to you. Remember that most colleges have specific services to help students with their writing.

For help with specific writing assignments and guidance on different aspects of writing, you may refer to the other chapters in this book. The table of contents lists topics in detail. As a general overview, the following paragraphs discuss what you will learn in the upcoming chapters.

Chapter 2 “Writing Basics: What Makes a Good Sentence?” through Chapter 7 “Refining Your Writing: How Do I Improve My Writing Technique?” will ground you in writing basics: the “nuts and bolts” of grammar, sentence structure, and paragraph development that you need to master to produce competent college-level writing. Chapter 2 “Writing Basics: What Makes a Good Sentence?” reviews the parts of speech and the components of a sentence. Chapter 3 “Punctuation” explains how to use punctuation correctly. Chapter 4 “Working with Words: Which Word Is Right?” reviews concepts that will help you use words correctly, including everything from commonly confused words to using context clues.

Chapter 5 “Help for English Language Learners” provides guidance for students who have learned English as a second language. Then, Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content” guides you through the process of developing a paragraph while Chapter 7 “Refining Your Writing: How Do I Improve My Writing Technique?” has tips to help you refine and improve your sentences.

Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” through Chapter 10 “Rhetorical Modes” are geared to help you apply those basics to college-level writing assignments. Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” shows the writing process in action with explanations and examples of techniques you can use during each step of the process. Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” provides further discussion of the components of college essays—how to create and support a thesis and how to organize an essay effectively. Chapter 10 “Rhetorical Modes” discusses specific modes of writing you will encounter as a college student and explains how to approach these different assignments.

Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” through Chapter 14 “Creating Presentations: Sharing Your Ideas” focus on how to write a research paper. Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” guides students through the process of conducting research, while Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” explains how to transform that research into a finished paper. Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” explains how to format your paper and use a standard system for documenting sources. Finally, Chapter 14 “Creating Presentations: Sharing Your Ideas” discusses how to transform your paper into an effective presentation.

Many of the chapters in this book include sample student writing—not just the finished essays but also the preliminary steps that went into developing those essays. Chapter 15 “Readings: Examples of Essays” of this book provides additional examples of different essay types.

Key Takeaways

- Following the steps of the writing process helps students complete any writing assignment more successfully.

- To manage writing assignments, it is best to work backward from the due date, allotting appropriate time to complete each step of the writing process.

- Setting concrete long- and short-term goals helps students stay focused and motivated.

- A variety of university resources are available to help students with writing and with other aspects of college life.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Check your paper for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- College essay

How to Write a College Essay | A Complete Guide & Examples

The college essay can make or break your application. It’s your chance to provide personal context, communicate your values and qualities, and set yourself apart from other students.

A standout essay has a few key ingredients:

- A unique, personal topic

- A compelling, well-structured narrative

- A clear, creative writing style

- Evidence of self-reflection and insight

To achieve this, it’s crucial to give yourself enough time for brainstorming, writing, revision, and feedback.

In this comprehensive guide, we walk you through every step in the process of writing a college admissions essay.

Table of contents

Why do you need a standout essay, start organizing early, choose a unique topic, outline your essay, start with a memorable introduction, write like an artist, craft a strong conclusion, revise and receive feedback, frequently asked questions.

While most of your application lists your academic achievements, your college admissions essay is your opportunity to share who you are and why you’d be a good addition to the university.

Your college admissions essay accounts for about 25% of your application’s total weight一and may account for even more with some colleges making the SAT and ACT tests optional. The college admissions essay may be the deciding factor in your application, especially for competitive schools where most applicants have exceptional grades, test scores, and extracurriculars.

What do colleges look for in an essay?

Admissions officers want to understand your background, personality, and values to get a fuller picture of you beyond your test scores and grades. Here’s what colleges look for in an essay :

- Demonstrated values and qualities

- Vulnerability and authenticity

- Self-reflection and insight

- Creative, clear, and concise writing skills

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

It’s a good idea to start organizing your college application timeline in the summer of your junior year to make your application process easier. This will give you ample time for essay brainstorming, writing, revision, and feedback.

While timelines will vary for each student, aim to spend at least 1–3 weeks brainstorming and writing your first draft and at least 2–4 weeks revising across multiple drafts. Remember to leave enough time for breaks in between each writing and editing stage.

Create an essay tracker sheet

If you’re applying to multiple schools, you will have to juggle writing several essays for each one. We recommend using an essay tracker spreadsheet to help you visualize and organize the following:

- Deadlines and number of essays needed

- Prompt overlap, allowing you to write one essay for similar prompts

You can build your own essay tracker using our free Google Sheets template.

College essay tracker template

Ideally, you should start brainstorming college essay topics the summer before your senior year. Keep in mind that it’s easier to write a standout essay with a unique topic.

If you want to write about a common essay topic, such as a sports injury or volunteer work overseas, think carefully about how you can make it unique and personal. You’ll need to demonstrate deep insight and write your story in an original way to differentiate it from similar essays.

What makes a good topic?

- Meaningful and personal to you

- Uncommon or has an unusual angle

- Reveals something different from the rest of your application

Brainstorming questions

You should do a comprehensive brainstorm before choosing your topic. Here are a few questions to get started:

- What are your top five values? What lived experiences demonstrate these values?

- What adjectives would your friends and family use to describe you?

- What challenges or failures have you faced and overcome? What lessons did you learn from them?

- What makes you different from your classmates?

- What are some objects that represent your identity, your community, your relationships, your passions, or your goals?

- Whom do you admire most? Why?

- What three people have significantly impacted your life? How did they influence you?

How to identify your topic

Here are two strategies for identifying a topic that demonstrates your values:

- Start with your qualities : First, identify positive qualities about yourself; then, brainstorm stories that demonstrate these qualities.

- Start with a story : Brainstorm a list of memorable life moments; then, identify a value shown in each story.

After choosing your topic, organize your ideas in an essay outline , which will help keep you focused while writing. Unlike a five-paragraph academic essay, there’s no set structure for a college admissions essay. You can take a more creative approach, using storytelling techniques to shape your essay.

Two common approaches are to structure your essay as a series of vignettes or as a single narrative.

Vignettes structure

The vignette, or montage, structure weaves together several stories united by a common theme. Each story should demonstrate one of your values or qualities and conclude with an insight or future outlook.

This structure gives the admissions officer glimpses into your personality, background, and identity, and shows how your qualities appear in different areas of your life.

Topic: Museum with a “five senses” exhibit of my experiences

- Introduction: Tour guide introduces my museum and my “Making Sense of My Heritage” exhibit

- Story: Racial discrimination with my eyes

- Lesson: Using my writing to document truth

- Story: Broadway musical interests

- Lesson: Finding my voice

- Story: Smells from family dinner table

- Lesson: Appreciating home and family

- Story: Washing dishes

- Lesson: Finding moments of peace in busy schedule

- Story: Biking with Ava

- Lesson: Finding pleasure in job well done

- Conclusion: Tour guide concludes tour, invites guest to come back for “fall College Collection,” featuring my search for identity and learning.

Single story structure

The single story, or narrative, structure uses a chronological narrative to show a student’s character development over time. Some narrative essays detail moments in a relatively brief event, while others narrate a longer journey spanning months or years.

Single story essays are effective if you have overcome a significant challenge or want to demonstrate personal development.

Topic: Sports injury helps me learn to be a better student and person

- Situation: Football injury

- Challenge: Friends distant, teachers don’t know how to help, football is gone for me

- Turning point: Starting to like learning in Ms. Brady’s history class; meeting Christina and her friends

- My reactions: Reading poetry; finding shared interest in poetry with Christina; spending more time studying and with people different from me

- Insight: They taught me compassion and opened my eyes to a different lifestyle; even though I still can’t play football, I’m starting a new game

Brainstorm creative insights or story arcs

Regardless of your essay’s structure, try to craft a surprising story arc or original insights, especially if you’re writing about a common topic.

Never exaggerate or fabricate facts about yourself to seem interesting. However, try finding connections in your life that deviate from cliché storylines and lessons.

| Common insight | Unique insight |

|---|---|

| Making an all-state team → outstanding achievement | Making an all-state team → counting the cost of saying “no” to other interests |

| Making a friend out of an enemy → finding common ground, forgiveness | Making a friend out of an enemy → confront toxic thinking and behavior in yourself |

| Choir tour → a chance to see a new part of the world | Choir tour → a chance to serve in leading younger students |

| Volunteering → learning to help my community and care about others | Volunteering → learning to be critical of insincere resume-building |

| Turning a friend in for using drugs → choosing the moral high ground | Turning a friend in for using drugs → realizing the hypocrisy of hiding your secrets |

Admissions officers read thousands of essays each year, and they typically spend only a few minutes reading each one. To get your message across, your introduction , or hook, needs to grab the reader’s attention and compel them to read more..

Avoid starting your introduction with a famous quote, cliché, or reference to the essay itself (“While I sat down to write this essay…”).

While you can sometimes use dialogue or a meaningful quotation from a close family member or friend, make sure it encapsulates your essay’s overall theme.