From 1871 to 2021: A Short History of Education in the United States

In 1600s and 1700s America, prior to the first and second Industrial Revolutions, educational opportunity varied widely depending on region, race, gender, and social class.

Public education, common in New England, was class-based, and the working class received few benefits, if any. Instructional styles and the nature of the curriculum were locally determined. Teachers themselves were expected to be models of strict moral behavior.

By the mid-1800s, most states had accepted three basic assumptions governing public education: that schools should be free and supported by taxes, that teachers should be trained, and that children should be required to attend school.

The term “normal school” is based on the French école normale, a sixteenth-century model school with model classrooms where model teaching practices were taught to teacher candidates. In the United States, normal schools were developed and built primarily to train elementary-level teachers for the public schools.

The Normal School The term “normal school” is based on the French école normale , a sixteenth-century model school with model classrooms where model teaching practices were taught to teacher candidates. This was a laboratory school where children on both the primary or secondary levels were taught, and where their teachers, and the instructors of those teachers, learned together in the same building. This model was employed from the inception of the Buffalo Normal School , where the “School of Practice” inhabited the first floors of the teacher preparation academy. In testament to its effectiveness, the Campus School continued in the same tradition after the college was incorporated and relocated on the Elmwood campus.

Earlier normal schools were reserved for men in Europe for many years, as men were thought to have greater intellectual capacity for scholarship than women. This changed (fortunately) during the nineteenth century, when women were more successful as private tutors than were men.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, newly industrialized European economies needed a reliable, reproducible, and uniform work force. The preparation of teachers to accomplish this goal became ever more important. The process of instilling in future citizens the norms of moral behavior led to the creation of the first uniform, formalized national educational curriculum. Thus, “normal” schools were tasked with developing this new curriculum and the techniques through which teachers would communicate and model these ideas, behaviors, and values for students who, it was hoped, through formal education, might desire and seek a better quality of life.

In the United States, normal schools were developed and built primarily to train elementary-level teachers for the public schools. In 1823, Reverend Samuel Read Hall founded the first private normal school in the United States, the Columbian School in Concord, Vermont. The first public normal school in the United States was founded shortly thereafter in 1839 in Lexington, Massachusetts. Both public and private “normals” initially offered a two-year course beyond the secondary level, but by the twentieth century, teacher-training programs required a minimum of four years. By the 1930s most normal schools had become “teachers colleges,” and by the 1950s they had evolved into distinct academic departments or schools of education within universities.

The Buffalo Normal School Buffalo State was founded in 1871 as the Buffalo Normal School. It changed its name more often than it changed its building. It has been called the State Normal and Training School (1888–1927), the State Teachers College at Buffalo (1928–1946), the New York State College for Teachers at Buffalo (1946–1950), SUNY, New York State College for Teachers (1950–1951), the State University College for Teachers at Buffalo (1951–1959), the State University College of Education at Buffalo (1960–1961), and finally the State University College at Buffalo in 1962, or as we know it more succinctly, SUNY Buffalo State College.

As early as the 1800s, visionary teachers explored teaching people with disabilities. Thomas Galludet developed a method to educate the deaf and hearing impaired. Dr. Samuel Howe focused on teaching the visually impaired, creating books with large, raised letters to assist people with sight impairments to “read” with their fingers.

What Goes Around, Comes Around: What Is Good Teaching? Throughout most of post-Renaissance history, teachers were most often male scholars or clergymen who were the elite literates who had no formal training in “how” to teach the content in which they were most well-versed. Many accepted the tenet that “teachers were born , not made .” It was not until “pedagogy,” the “art and science of teaching,” attained a theoretical respectability that the training of educated individuals in the science of teaching was considered important.

While scholars of other natural and social sciences still debate the scholarship behind the “science” of teaching, even those who accept pedagogy as a science admit that there is reason to support one theory that people can be “born” with the predisposition to be a good teacher. Even today, while teacher education programs are held accountable by accreditors for “what” they teach teachers, the “dispositions of teaching” are widely debated, yet considered essential to assess the suitability of a teacher candidate to the complexities of the profession. Since the nineteenth century, however, pedagogy has attempted to define the minimal characteristics needed to qualify a person as a teacher. These have remained fairly constant as the bases for educator preparation programs across the country: knowledge of subject matter, knowledge of teaching methods, and practical experience in applying both are still the norm. The establishment of the “norms” of pedagogy and curriculum, hence the original name of “normal school” for teacher training institutions, recognized the social benefit and moral value of ensuring a quality education for all.

As with so many innovations and trends that swept the post-industrial world in the twentieth century, education, too, has experienced many changes. The names of the great educational theorists and reformers of the Progressive Era in education are known to all who know even a little about teaching and learning: Jean Piaget , Benjamin Bloom , Maria Montessori , Horace Mann , and John Dewey to name only a few.

As early as the 1800s, visionary teachers explored teaching people with disabilities. Thomas Galludet developed a method to educate the deaf and hearing impaired. He opened the Hartford School for the Deaf in Connecticut in 1817. Dr. Samuel Howe focused on teaching the visually impaired, creating books with large, raised letters to assist people with sight impairments to “read” with their fingers. Howe led the Perkins Institute, a school for the blind, in Boston. Such schools were usually boarding schools for students with disabilities. There are still residential schools such as St. Mary’s School for the Deaf in Buffalo, but as pedagogy for all children moved into the twentieth century, inclusive practice where children with disabilities were educated in classrooms with non-disabled peers yielded excellent results. This is the predominant pedagogy taught by our Exceptional Education faculty today.

As the reform movements in education throughout the twentieth century introduced ideas of equality, child-centered learning, assessment of learner achievement as a measure of good teaching, and other revolutionary ideas such as inquiry-based practice, educating the whole person, and assuring educational opportunities for all persons, so did the greater emphasis on preparing teachers to serve the children of the public, not just those of the elite.

This abridged version of events that affected teacher education throughout the twentieth century mirrors the incredible history of the country from WWI’s post-industrial explosion to the turbulent 1960s, when the civil rights movement and the women’s rights movement dominated the political scene and schools became the proving ground for integration and Title IX enforcement of equality of opportunity. Segregation in schools went to the Supreme Court in 1954 with Brown vs. Board of Education. Following this monumental decision, schools began the slow process of desegregating schools, a process that, sadly, is still not yet achieved.

As schools became more and more essential to the post-industrial economy and the promotion of human rights for all, teaching became more and more regulated. By the end of the twentieth century, licensing requirements had stiffened considerably in public education, and salary and advancement often depended on the earning of advanced degrees and professional development in school-based settings.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the Sputnik generation’s worship of science gave rise to similarities in terminology between the preparation of teachers and the preparation of doctors. “Lab schools” and quantitative research using experimental and quasi-experimental designs to test reading and math programs and other curricular innovations were reminiscent of the experimental designs used in medical research. Student teaching was considered an “internship,” akin to the stages of practice doctors followed. Such terminology and parallels to medicine, however, fell out of vogue with a general disenchantment with science and positivism in the latter decades of the twentieth century. Interestingly, these parallels have resurfaced today as we refer to our model of educating teachers in “clinically rich settings.” We have even returned to “residency” programs, where teacher candidates are prepared entirely in the schools where they will eventually teach.

As schools became more and more essential to the post-industrial economy and the promotion of human rights for all, teaching became more and more regulated. By the end of the twentieth century, licensing requirements had stiffened considerably in public education, and salary and advancement often depended on the earning of advanced degrees and professional development in school-based settings. Even today, all programs in colleges and universities that prepare teachers must follow extensive and detailed guidelines established by the New York State Education Department that determine what must be included in such programs. Additions such as teaching to students with disabilities and teaching to English language learners are requirements that reflect the changing needs of classrooms.

As the world changed, so did the preparation of teachers. The assimilation of the normal school into colleges and universities marked the evolution of teaching as a profession, a steady recognition over the last 150 years that has allowed the teacher as scientist to explore how teaching and learning work in tandem and to suggest that pedagogy is dynamic and interactive with sociopolitical forces and that schools play a critical role in the democratic promotion of social justice.

Campus Schools and Alternative Classroom Organization During the ’60s and ’70s, new concepts of schooling such as multigrade classrooms and open-concept spaces, where students followed their own curiosity through project-based learning, were played out right here at Buffalo State in what was then the College Learning Lab (Campus School). Campus School shared many of the college’s resources and served as the clinical site for the preparation of teachers. School administration and teachers held joint appointments at the college and in the lab. Classrooms were visible through one-way glass, where teacher candidates could observe and review what they saw with the lab school teacher afterward. Participation in these classrooms was a requirement during the junior year. (I myself did my junior participation in a 5/6 open class there.)

However, as the SUNY colleges became less and less supported by New York State budgetary allocations, the Campus School was soon too expensive to staff and to maintain. The baby boom was over, and the population was shrinking. Job opportunities for the graduates of Buffalo State were rare. A 10-year cycle of teacher shortage and teacher over-supply continues to be a trend.

Standards and Norms In the 1980s, education in America once again turned to “norming,” but now the norms were not measuring one child against others; rather, each child was assessed as he or she approached the “national standards” that theoretically defined the knowledge and skills necessary for all to achieve.

Fearing America’s loss of stature as the technologically superior leader of the free world, A Nation at Risk , published in 1983, cast a dark shadow over teaching and schools for many years to come until its premises were largely disrupted. During the time after this report, however, being a teacher was not a popular career choice, and teaching as a profession was called into question.

By 1998, almost every state had defined or implemented academic standards for math and reading. Principals and teachers were judged; students were promoted or retained, and legislation was passed so that high school students would graduate or be denied a diploma based on whether or not they had met the standards, usually as measured by a criterion-referenced test.

In the 1980s, education in America once again turned to “norming,” but now the norms were not measuring one child against others; rather, each child was assessed as he or she approached the “national standards” that theoretically defined the knowledge and skills necessary for all to achieve.

The pressure to teach to a standards-based curriculum, to test all students in an effort to ensure equal education for all, led to some famous named policies of presidents and secretaries of education in the later twentieth century. National panels and political pundits returned to the roots of the “normal school” movement, urging colleges of teacher education to acquaint teacher candidates with the national educational standards known as Goals 2000 . The George H. W. Bush administration kicked off an education summit with the purpose of “righting the ship” since the shock of A Nation at Risk . Standards-based curriculum became a “teacher proof” system of ensuring that all children—no matter what their socioeconomic privilege—would be taught the same material. This “curriculum first” focus for school planning persisted through the Clinton administration with the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), the George W. Bush administration with No Child Left Behind , and the Obama administration with Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) and the accompanying federal funding called Race to the Top . Such packaged standards-based curriculum movements once again turned the public eye to a need to conform, achieve, and compete.

For teachers, the most important development from this pressure to teach to the standards was the controversial Common Core , a nationalized curriculum based on standards of education that were designed to give all students common experiences within a carefully constructed framework that would transcend race, gender, economics, region, and aptitude. So focused were the materials published on the Common Core that schools began to issue scripted materials to their teachers to ensure the same language was used in every classroom. Teacher autonomy was suppressed, and time for language arts and mathematics began to eclipse the study of science, social studies, art, music.

Now What? That takes us almost to today’s schools, where teachers are still accountable for helping student achieve the Common Core standards or more currently the National Standards. Enter the COVID pandemic. Full stop.

Curriculum, testing, conformity, and standards are out the window. The American parent can now “see into” the classroom and the teacher can likewise “see into” the American home. Two-dimensional, computer-assisted instruction replaced the dynamic interactive classroom where learning is socially constructed and facilitated by teachers who are skilled at classroom management, social-emotional learning, and project-based group work. Teacher candidates must now rely on their status as digital natives to engage and even entertain their students who now come to them as a collective of individuals framed on a computer screen rather than in a classroom of active bodies who engage with each other in myriad ways. Last year’s pedagogical challenges involved mastery of the 20-minute attention span, the teacher as entertainer added to the teacher as facilitator . Many of our teacher candidates learned more about themselves than they did about their students. Yet, predominately, stories of creativity, extraordinary uses of technology, and old-fashioned persistence and ingenuity were the new “norm” for the old Buffalo State Normal School.

There has been nothing “normal” about these last two years as the world learns to cope with a silent enemy. There will be no post-war recovery, no post-industrial reforms, no equity of opportunity in schools around the world. But there will be teaching. And there will be learning. And the Buffalo State Normal School will continue to prepare the highest quality practitioners whose bags of tricks grow ever-more flexible, driven by a world where all that is known doubles in just a few days. Pedagogy is still a science. Teaching is a science, but it is also a craft practiced by master craftsmen and women and learned by apprentices.

Teaching has been called the noblest profession. From our earliest roots as the Buffalo Normal School to the current challenges of post-COVID America, we have never changed our dedication to that conviction.

Ultimately, however, as even the earliest teacher educators knew, the art of teaching is that ephemeral quality that we cannot teach, but which we know when we see it at work, that makes the great teacher excel far beyond the competent teacher.

Teaching has been called the noblest profession. From our earliest roots as the Buffalo Normal School to the current challenges of post-COVID America, we have never changed our dedication to that conviction. We are still doing what the words of Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai encourage us to do: “One child, one teacher, one book, one pen can change the world.” That was and always will be the mission of Buffalo State, “the Teachers College.”

This article was contributed as part of a guest author series observing the 150th anniversary celebration of Buffalo State College. Campus authors who are interested in submitting articles or story ideas pertaining to the sesquicentennial are encouraged to contact the editor .

Wendy Paterson, ’75, ’76, Ph.D., dean of the School of Education, is an internationally recognized scholar in the areas of early literacy and reading, developmental and educational technology, and single parenting. She received the SUNY Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Professional Service in 1996.

Read other stories in the 150th anniversary guest author series:

Pomp, Pageantry Seize the Day in 1869 Normal School Cornerstone Laying

Transforming Lives for 150 Years: Memoir of a 1914 Graduate

Buffalo Normal School Held Opening Ceremony 150 Years Ago Today

New Buffalo Normal School Replaces Outgrown Original

The Grover Cleveland–E. H. Butler Letters at Buffalo State

Test Your College Knowledge with a Buffalo State Crossword Puzzle

Photo: Staff of the Record student newspaper, 1913 .

References:

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/teachereducationx92x1/chapter/education-reforms/

https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Normal_school

https://britannica.com/topic/normal-school

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1216495.pdf

https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Normal_school

http://reformmovements1800s.weebly.com/education.html

http://www.leaderinme.org/blog/history-of-education-the-united-states-in-a-nutshell/

Brewminate: A Bold Blend of News and Ideas

A History of Education from the Ancient World to Today

Share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

The history of education extends at least as far back as the first written records recovered from ancient civilizations.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh Public Historian Brewminate

The history of education extends at least as far back as the first written records recovered from ancient civilizations. Historical studies have included virtually every nation. [1][2][3]

Education in the Ancient World

Middle East

Perhaps the earliest formal school was developed in Egypt’s Middle Kingdom under the direction of Kheti, treasurer to Mentuhotep II (2061-2010 BC). [4]

In Mesopotamia, the early logographic system of cuneiform script took many years to master. Thus only a limited number of individuals were hired as scribes to be trained in its reading and writing. Only royal offspring and sons of the rich and professionals such as scribes, physicians, and temple administrators, were schooled. [5] Most boys were taught their father’s trade or were apprenticed to learn a trade. [6] Girls stayed at home with their mothers to learn housekeeping and cooking, and to look after the younger children. Later, when a syllabic script became more widespread, more of the Mesopotamian population became literate. Later still in Babylonian times there were libraries in most towns and temples; an old Sumerian proverb averred “he who would excel in the school of the scribes must rise with the dawn.” There arose a whole social class of scribes, mostly employed in agriculture, but some as personal secretaries or lawyers. [7] Women as well as men learned to read and write, and for the Semitic Babylonians, this involved knowledge of the extinct Sumerian language, and a complicated and extensive syllabary. Vocabularies, grammars, and interlinear translations were compiled for the use of students, as well as commentaries on the older texts and explanations of obscure words and phrases. In those times of course there were no assignment helpers as we have now, GrabMyEssay would be a great relief for ancient students. Massive archives of texts were recovered from the archaeological contexts of Old Babylonian scribal schools known as edubas (2000–1600 BCE), through which literacy was disseminated. Massive archives of texts were recovered from the archaeological contexts of Old Babylonian scribal schools known as edubas (2000–1600 BCE), through which literacy was disseminated. The Epic of Gilgamesh, an epic poem from Ancient Mesopotamia is among the earliest known works of literary fiction. The earliest Sumerian versions of the epic date from as early as the Third Dynasty of Ur (2150–2000 BC) (Dalley 1989: 41–42).

Ashurbanipal (685 – c. 627 BC), a king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, was proud of his scribal education. His youthful scholarly pursuits included oil divination, mathematics, reading and writing as well as the usual horsemanship, hunting, chariotry, soldierliness, craftsmanship, and royal decorum. During his reign he collected cuneiform texts from all over Mesopotamia, and especially Babylonia, in the library in Nineveh, the first systematically organized library in the ancient Middle East, [8] which survives in part today.

In ancient Egypt, literacy was concentrated among an educated elite of scribes. Only people from certain backgrounds were allowed to train to become scribes, in the service of temple, pharaonic, and military authorities. The hieroglyph system was always difficult to learn, but in later centuries was purposely made even more so, as this preserved the scribes’ status. The rate of literacy in Pharaonic Egypt during most periods from the third to first millennium BC has been estimated at not more than one percent, [9] or between one half of one percent and one percent. [10]

In ancient Israel, the Torah (the fundamental religious text) includes commands to read, learn, teach and write the Torah, thus requiring literacy and study. In 64 AD the high priest caused schools to be opened. [11] Emphasis was placed on developing good memory skills in addition to comprehension oral repetition. For details of the subjects taught, see History of education in ancient Israel and Judah. Although girls were not provided with formal education in the yeshivah, they were required to know a large part of the subject areas to prepare them to maintain the home after marriage, and to educate the children before the age of seven. Despite this schooling system, it would seem that many children did not learn to read and write, because it has been estimated that “at least ninety percent of the Jewish population of Roman Palestine [in the first centuries AD] could merely write their own name or not write and read at all”, [12] or that the literacy rate was about 3 percent. [13]

In the Islamic civilization that spread all the way between China and Spain during the time between the 7th and 19th centuries, Muslims started schooling from 622 in Medina, which is now a city in Saudi Arabia, schooling at first was in the mosques (masjid in Arabic) but then schools became separate in schools next to mosques. The first separate school was the Nizamiyah school. It was built in 1066 in Baghdad. Children started school from the age of six with free tuition. The Quran encourages Muslims to be educated. Thus, education and schooling sprang up in the ancient Muslim societies. Moreover, Muslims had one of the first universities in history which is Al-Qarawiyin University in Fez, Morocco. It was originally a mosque that was built in 859. [14]

In ancient India, education was mainly imparted through the Vedic and Buddhist education system. Sanskrit was the language used to impart the Vedic education system. Pali was the language used in the Buddhist education system. In the Vedic system, a child started his education at the age of five, whereas in the Buddhist system the child started his education at the age of eight. The main aim of education in ancient India was to develop a person’s character, master the art of self-control, bring about social awareness, and to conserve and take forward ancient culture.

The Buddhist and Vedic systems had different subjects. In the Vedic system of study, the students were taught the four Vedas – Rig Veda, Sama Veda, Yajur Veda and Atharva Veda, they were also taught the six Vedangas – ritualistic knowledge, metrics, exegetics, grammar, phonetics and astronomy, the Upanishads and more.

In ancient India, education was imparted and passed on orally rather than in written form. Education was a process that involved three steps, first was Shravana (hearing) which is the acquisition of knowledge by listening to the Shrutis. The second is Manana (reflection) wherein the students think, analyze and make inferences. Third, is Nididhyāsana in which the students apply the knowledge in their real life.

During the Vedic period from about 1500 BC to 600 BC, most education was based on the Veda (hymns, formulas, and incantations, recited or chanted by priests of a pre-Hindu tradition) and later Hindu texts and scriptures. The main aim of education, according to the Vedas, is liberation.

Vedic education included proper pronunciation and recitation of the Veda, the rules of sacrifice, grammar and derivation, composition, versification and meter, understanding of secrets of nature, reasoning including logic, the sciences, and the skills necessary for an occupation. [15] Some medical knowledge existed and was taught. There is mention in the Veda of herbal medicines for various conditions or diseases, including fever, cough, baldness, snake bite and others. [15]

Education, at first freely available in Vedic society, became over time more rigid and restricted as the social systems dictated that only those of meritorious lineage be allowed to study the scriptures, originally based on occupation, evolved, with the Brahman (priests) being the most privileged of the castes, followed by Kshatriya who could also wear the sacred thread and gain access to Vedic education. The Brahmans were given priority even over Kshatriya as they would dedicate their whole lives to such studies. [15][16]

Educating the women was given a great deal of importance in ancient India. Women were trained in dance, music and housekeeping. The Sadyodwahas class of women got educated till they were married. The Brahmavadinis class of women never got married and educated themselves for their entire life. Parts of Vedas that included poems and religious songs required for rituals were taught to women. Some noteworthy women scholars of ancient India include Ghosha, Gargi, Indrani and so on. [17]

The oldest of the Upanishads – another part of Hindu scriptures – date from around 500 BC. The Upanishads are considered as “wisdom teachings” as they explore the deeper and actual meaning of sacrifice. These texts encouraged an exploratory learning process where teachers and students were co-travellers in a search for truth. The teaching methods used reasoning and questioning. Nothing was labeled as the final answer. [15]

The Gurukula system of education supported traditional Hindu residential schools of learning; typically the teacher’s house or a monastery. In the Gurukul system, the teacher (Guru) and the student (Śiṣya) were considered to be equal even if they belonged to different social standings. Education was free, but students from well-to-do families paid “Gurudakshina”, a voluntary contribution after the completion of their studies. Gurudakshina is a mark of respect by the students towards their Guru. It is a way in which the students acknowledged, thanked and respected their Guru, whom they consider to be their spiritual guide. The corpus of Sanskrit literature encompasses a rich tradition of poetry and drama as well as technical scientific, philosophical and generally Hindu religious texts, though many central texts of Buddhism and Jainism have also been composed in Sanskrit.

Two epic poems formed part of ancient Indian education. The Mahabharata, part of which may date back to the 8th century BC, [18] discusses human goals (purpose, pleasure, duty, and liberation), attempting to explain the relationship of the individual to society and the world (the nature of the ‘Self’) and the workings of karma. The other epic poem, Ramayana, is shorter, although it has 24,000 verses. It is thought to have been compiled between about 400 BC and 200 AD. The epic explores themes of human existence and the concept of dharma (doing ones duty). [18]

In the Buddhist education system, the subjects included Pitakas. The Vinaya Pitaka is a Buddhist canon that contains a code of rules and regulations that govern the Buddhist community residing in the Monastery. The Vinaya Pitaka is especially preached to Buddhist monks (Sanga) to maintain discipline when interacting with people and nature. The set of rules ensures that people, animals, nature and the environment are not harmed by the Buddhist monks. The Sutta Pitaka is divided into 5 niyakas (collections). It contains Buddhas teachings recorded mainly as sermons. The Abhidhamma Pitaka contains a summary and analysis of Buddha’s teachings.

An early centre of learning in India dating back to the 5th century BC was Taxila (also known as Takshashila ), which taught the three Vedas and the eighteen accomplishments. [19] It was an important Vedic/Hindu [20] and Buddhist [21] centre of learning from the 6th century BC [22] to the 5th century AD. [23][24]

Another important centre of learning from 5th century CE was Nalanda. In the kingdom of Magadha, Nalanda was well known Buddhist monastery. Scholars and students from Tibet, China, Korea and Central Asia traveled to Nalanda in pursuit of education. Vikramashila was one of the largest Buddhist monasteries that was set up in 8th to 9th centuries.

According to legendary accounts, the rulers Yao and Shun (ca. 24th–23rd century BC) established the first schools. The first education system was created in Xia dynasty (2076–1600 BC). During Xia dynasty, government built schools to educate aristocrats about rituals, literature and archery (important for ancient Chinese aristocrats).

During Shang dynasty (1600 BC to 1046 BC), normal people (farmers, workers etc.) accepted rough education. In that time, aristocrats’ children studied in government schools. And normal people studied in private schools. Government schools were always built in cities and private schools were built in rural areas. Government schools paid attention on educating students about rituals, literature, politics, music, arts and archery. Private schools educated students to do farmwork and handworks. [25]

During the Zhou dynasty (1045–256 BC), there were five national schools in the capital city, Pi Yong (an imperial school, located in a central location) and four other schools for the aristocrats and nobility, including Shang Xiang. The schools mainly taught the Six Arts: rites, music, archery, charioteering, calligraphy, and mathematics. According to the Book of Rites, at age twelve, boys learned arts related to ritual (i.e. music and dance) and when older, archery and chariot driving. Girls learned ritual, correct deportment, silk production and weaving. [26]

It was during the Zhou dynasty that the origins of native Chinese philosophy also developed. Confucius (551–479 BC) founder of Confucianism, was a Chinese philosopher who made a great impact on later generations of Chinese, and on the curriculum of the Chinese educational system for much of the following 2000 years.

Later, during the Qin dynasty (246–207 BC), a hierarchy of officials was set up to provide central control over the outlying areas of the empire. To enter this hierarchy, both literacy and knowledge of the increasing body of philosophy was required: “….the content of the educational process was designed not to engender functionally specific skills but rather to produce morally enlightened and cultivated generalists”. [27]

During the Han dynasty (206–221 AD), boys were thought ready at age seven to start learning basic skills in reading, writing and calculation. [25] In 124 BC, the Emperor Wudi established the Imperial Academy, the curriculum of which was the Five Classics of Confucius. By the end of the Han dynasty (220 AD) the academy enrolled more than 30,000 students, boys between the ages of fourteen and seventeen years. However education through this period was a luxury. [26]

The nine-rank system was a civil service nomination system during the Three Kingdoms (220–280 AD) and the Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589 AD) in China. Theoretically, local government authorities were given the task of selecting talented candidates, then categorizing them into nine grades depending on their abilities. In practice, however, only the rich and powerful would be selected. The Nine Rank System was eventually superseded by the imperial examination system for the civil service in the Sui dynasty (581–618 AD).

Greece and Rome

In the city-states of ancient Greece, most education was private, except in Sparta. For example, in Athens, during the 5th and 4th century BC, aside from two years military training, the state played little part in schooling. [28][29] Anyone could open a school and decide the curriculum. Parents could choose a school offering the subjects they wanted their children to learn, at a monthly fee they could afford. [28] Most parents, even the poor, sent their sons to schools for at least a few years, and if they could afford it from around the age of seven until fourteen, learning gymnastics (including athletics, sport and wrestling), music (including poetry, drama and history) and literacy. [28][29] Girls rarely received formal education. At writing school, the youngest students learned the alphabet by song, then later by copying the shapes of letters with a stylus on a waxed wooden tablet. After some schooling, the sons of poor or middle-class families often learnt a trade by apprenticeship, whether with their father or another tradesman. [28] By around 350 BC, it was common for children at schools in Athens to also study various arts such as drawing, painting, and sculpture. The richest students continued their education by studying with sophists, from whom they could learn subjects such as rhetoric, mathematics, geography, natural history, politics, and logic. [28][29] Some of Athens’ greatest schools of higher education included the Lyceum (the so-called Peripatetic school founded by Aristotle of Stageira) and the Platonic Academy (founded by Plato of Athens). The education system of the wealthy ancient Greeks is also called Paideia. In the subsequent Roman empire, Greek was the primary language of science. Advanced scientific research and teaching was mainly carried on in the Hellenistic side of the Roman empire, in Greek.

The education system in the Greek city-state of Sparta was entirely different, designed to create warriors with complete obedience, courage, and physical perfection. At the age of seven, boys were taken away from their homes to live in school dormitories or military barracks. There they were taught sports, endurance and fighting, and little else, with harsh discipline. Most of the population was illiterate. [28][29]

The first schools in Ancient Rome arose by the middle of the 4th century BC. [30] These schools were concerned with the basic socialization and rudimentary education of young Roman children. The literacy rate in the 3rd century BC has been estimated as around one percent to two percent. [31] There are very few primary sources or accounts of Roman educational process until the 2nd century BC, [30] during which there was a proliferation of private schools in Rome. [31] At the height of the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire, the Roman educational system gradually found its final form. Formal schools were established, which served paying students (very little in the way of free public education as we know it can be found). [32] Normally, both boys and girls were educated, though not necessarily together. [32] In a system much like the one that predominates in the modern world, the Roman education system that developed arranged schools in tiers. The educator Quintilian recognized the importance of starting education as early as possible, noting that “memory … not only exists even in small children, but is specially retentive at that age”. [33] A Roman student would progress through schools just as a student today might go from elementary school to middle school, then to high school, and finally college. Progression depended more on ability than age [32] with great emphasis being placed upon a student’s ingenium or inborn “gift” for learning, [34] and a more tacit emphasis on a student’s ability to afford high-level education. Only the Roman elite would expect a complete formal education. A tradesman or farmer would expect to pick up most of his vocational skills on the job. Higher education in Rome was more of a status symbol than a practical concern.

Literacy rates in the Greco-Roman world were seldom more than 20 percent; averaging perhaps not much above 10 percent in the Roman empire, though with wide regional variations, probably never rising above 5 percent in the western provinces. The literate in classical Greece did not much exceed 5 percent of the population. [35][36]

Formal Education in the Middle Ages, 500-1500 CE

The word school applies to a variety of educational organizations in the Middle Ages, including town, church, and monastery schools. During the late medieval period, students attending town schools were usually between the ages of seven and fourteen. Instruction for boys in such schools ranged from the basics of literacy (alphabet, syllables, simple prayers and proverbs) to more advanced instruction in the Latin language. Occasionally, these schools may also have taught rudimentary arithmetic or letter writing and other skills useful in business. Often instruction at various levels took place in the same schoolroom. [37]

During the Early Middle Ages, the monasteries of the Roman Catholic Church were the centers of education and literacy, preserving the Church’s selection from Latin learning and maintaining the art of writing. Prior to their formal establishment, many medieval universities were run for hundreds of years as Christian monastic schools ( Scholae monasticae ), in which monks taught classes, and later as cathedral schools; evidence of these immediate forerunners of the later university at many places dates back to the early 6th century. [38]

The first medieval institutions generally considered to be universities were established in Italy, France, and England in the late 11th and the 12th centuries for the study of arts, law, medicine, and theology.[1] These universities evolved from much older Christian cathedral schools and monastic schools, and it is difficult to define the date on which they became true universities, although the lists of studia generalia for higher education in Europe held by the Vatican are a useful guide.

Students in the twelfth-century were very proud of the master whom they studied under. They were not very concerned with telling others the place or region where they received their education. Even now when scholars cite schools with distinctive doctrines, they use group names to describe the school rather than its geographical location. Those who studied under Robert of Melun were called the Meludinenses . These people did not study in Melun, but in Paris, and were given the group name of their master. Citizens in the twelfth-century became very interested in learning the rare and difficult skills masters could provide. [39]

Ireland became known as the island of saints and scholars. Monasteries were built all over Ireland, and these became centres of great learning.

Northumbria was famed as a centre of religious learning and arts. Initially the kingdom was evangelized by monks from the Celtic Church, which led to a flowering of monastic life, and Northumbria played an important role in the formation of Insular art, a unique style combining Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, Byzantine and other elements. After the Synod of Whitby in 664 AD, Roman church practices officially replaced the Celtic ones but the influence of the Anglo-Celtic style continued, the most famous examples of this being the Lindisfarne Gospels. The Venerable Bede (673–735) wrote his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People, completed in 731) in a Northumbrian monastery, and much of it focuses on the kingdom. [40]

During the reign of Charlemagne, King of the Franks from 768 to 814 AD, whose empire united most of Western Europe for the first time since the Romans, there was a flowering of literature, art, and architecture known as the Carolingian Renaissance. Brought into contact with the culture and learning of other countries through his vast conquests, Charlemagne greatly increased the provision of monastic schools and scriptoria (centres for book-copying) in Francia. Most of the surviving works of classical Latin were copied and preserved by Carolingian scholars.

Charlemagne took a serious interest in scholarship, promoting the liberal arts at the court, ordering that his children and grandchildren be well-educated, and even studying himself under the tutelage of Paul the Deacon, from whom he learned grammar, Alcuin, with whom he studied rhetoric, dialect and astronomy (he was particularly interested in the movements of the stars), and Einhard, who assisted him in his studies of arithmetic. The English monk Alcuin was invited to Charlemagne’s court at Aachen, and brought with him the precise classical Latin education that was available in the monasteries of Northumbria. [41] The return of this Latin proficiency to the kingdom of the Franks is regarded as an important step in the development of mediaeval Latin. Charlemagne’s chancery made use of a type of script currently known as Carolingian minuscule, providing a common writing style that allowed for communication across most of Europe. After the decline of the Carolingian dynasty, the rise of the Saxon Dynasty in Germany was accompanied by the Ottonian Renaissance.

Additionally, Charlemagne attempted to establish a free elementary education by parish priests for youth in a capitulary of 797. The capitulary states “that the priests establish schools in every town and village, and if any of the faithful wish to entrust their children to them to learn letters, that they refuse not to accept them but with all charity teach them … and let them exact no price from the children for their teaching nor receive anything from them save what parents may offer voluntarily and from affection” (P.L., CV., col. 196) [42]

Cathedral schools and monasteries remained important throughout the Middle Ages; at the Third Lateran Council of 1179 the Church mandated that priests provide the opportunity of a free education to their flocks, and the 12th and 13th century renascence known as the Scholastic Movement was spread through the monasteries. These however ceased to be the sole sources of education in the 11th century when universities, which grew out of the monasticism began to be established in major European cities. Literacy became available to a wider class of people, and there were major advances in art, sculpture, music and architecture. [43]

In 1120, Dunfermline Abbey in Scotland by order of Malcolm Canmore and his Queen, Margaret, built and established the first high school in the UK, Dunfermline High School. This highlighted the monastery influence and developments made for education, from the ancient capital of Scotland.

Sculpture, paintings and stained glass windows were vital educational media through which Biblical themes and the lives of the saints were taught to illiterate viewers. [44]

Islamic World

The University of al-Qarawiyyin located in Fes, Morocco is the oldest existing, continually operating and the first degree awarding educational institution in the world according to UNESCO and Guinness World Records [45] and is sometimes referred to as the oldest university. [46]

The House of Wisdom in Baghdad was a library, translation and educational centre from the 9th to 13th centuries. Works on astrology, mathematics, agriculture, medicine, and philosophy were translated. Drawing on Persian, Indian and Greek texts—including those of Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates, Euclid, Plotinus, Galen, Sushruta, Charaka, Aryabhata and Brahmagupta—the scholars accumulated a great collection of knowledge in the world, and built on it through their own discoveries. The House was an unrivalled centre for the study of humanities and for sciences, including mathematics, astronomy, medicine, chemistry, zoology and geography. Baghdad was known as the world’s richest city and centre for intellectual development of the time, and had a population of over a million, the largest in its time. [47]

The Islamic mosque school (Madrasah) taught the Quran in Arabic and did not at all resemble the medieval European universities. [48][49]

In the 9th century, Bimaristan medical schools were formed in the medieval Islamic world, where medical diplomas were issued to students of Islamic medicine who were qualified to be a practicing Doctor of Medicine. [50] Al-Azhar University, founded in Cairo, Egypt in 975, was a Jami’ah (“university” in Arabic) which offered a variety of post-graduate degrees, had a Madrasah and theological seminary, and taught Islamic law, Islamic jurisprudence, Arabic grammar, Islamic astronomy, early Islamic philosophy and logic in Islamic philosophy. [50]

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the town of Timbuktu in the West African nation of Mali became an Islamic centre of learning with students coming from as far away as the Middle East. The town was home to the prestigious Sankore University and other madrasas. The primary focus of these schools was the teaching of the Qur’an, although broader instruction in fields such as logic, astronomy, and history also took place. Over time, there was a great accumulation of manuscripts in the area and an estimated 100,000 or more manuscripts, some of them dated from pre-Islamic times and 12th century, are kept by the great families from the town. [51] Their contents are didactic, especially in the subjects of astronomy, music, and botany. More than 18,000 manuscripts have been collected by the Ahmed Baba centre. [52]

Although there are more than 40,000 Chinese characters in written Chinese, many are rarely used. Studies have shown that full literacy in the Chinese language requires a knowledge of only between three and four thousand characters. [53]

In China, three oral texts were used to teach children by rote memorization the written characters of their language and the basics of Confucian thought.

The Thousand Character Classic, a Chinese poem originating in the 6th century, was used for more than a millennium as a primer for teaching Chinese characters to children. The poem is composed of 250 phrases of four characters each, thus containing exactly one thousand unique characters, and was sung in the same way that children learning the Latin alphabet may use the “alphabet song”.

Later, children also learn the Hundred Family Surnames, a rhyming poem in lines of eight characters composed in the early Song dynasty [54] (i.e. in about the 11th century) which actually listed more than four hundred of the common surnames in ancient China.

From around the 13th century until the latter part of the 19th century, the Three Character Classic, which is an embodiment of Confucian thought suitable for teaching to young children, served as a child’s first formal education at home. The text is written in triplets of characters for easy memorization. With illiteracy common for most people at the time, the oral tradition of reciting the classic ensured its popularity and survival through the centuries. With the short and simple text arranged in three-character verses, children learned many common characters, grammar structures, elements of Chinese history and the basis of Confucian morality.

After learning Chinese characters, students wishing to ascend in the social hierarchy needed to study the Chinese classic texts.

The early Chinese state depended upon literate, educated officials for operation of the empire. In 605 AD, during the Sui dynasty, for the first time, an examination system was explicitly instituted for a category of local talents. The merit-based imperial examination system for evaluating and selecting officials gave rise to schools that taught the Chinese classic texts and continued in use for 1,300 years, until the end the Qing dynasty, being abolished in 1911 in favour of Western education methods. The core of the curriculum for the imperial civil service examinations from the mid-12th century onwards was the Four Books, representing a foundational introduction to Confucianism.

Theoretically, any male adult in China, regardless of his wealth or social status, could become a high-ranking government official by passing the imperial examination, although under some dynasties members of the merchant class were excluded. In reality, since the process of studying for the examination tended to be time-consuming and costly (if tutors were hired), most of the candidates came from the numerically small but relatively wealthy land-owning gentry. However, there are vast numbers of examples in Chinese history in which individuals moved from a low social status to political prominence through success in imperial examination. Under some dynasties the imperial examinations were abolished and official posts were simply sold, which increased corruption and reduced morale.

In the period preceding 1040–1050 AD, prefectural schools had been neglected by the state and left to the devices of wealthy patrons who provided private finances. [55] The chancellor of China at that time, Fan Zhongyan, issued an edict that would have used a combination of government funding and private financing to restore and rebuild all prefectural schools that had fallen into disuse and abandoned. [55] He also attempted to restore all county-level schools in the same manner, but did not designate where funds for the effort would be formally acquired and the decree was not taken seriously until a later period. [55] Fan’s trend of government funding for education set in motion the movement of public schools that eclipsed private academies, which would not be officially reversed until the mid-13th century. [55]

The first millennium and the few centuries preceding it saw the flourishing of higher education at Nalanda, Takshashila University, Ujjain, & Vikramshila Universities. Among the subjects taught were Art, Architecture, Painting, Logic, mathematics, Grammar, Philosophy, Astronomy, Literature, Buddhism, Hinduism, Arthashastra (Economics & Politics), Law, and Medicine. Each university specialized in a particular field of study. Takshila specialized in the study of medicine, while Ujjain laid emphasis on astronomy. Nalanda, being the biggest centre, handled all branches of knowledge, and housed up to 10,000 students at its peak. [56]

Vikramashila Mahavihara, another important center of Buddhist learning in India, was established by King Dharmapala (783 to 820) in response to a supposed decline in the quality of scholarship at Nālandā. [57]

Major work in the fields of Mathematics, Astronomy, and Physics were done by Aryabhata. Approximations of pi, basic trigonometric equation, indeterminate equation, and positional notation are mentioned in Aryabhatiya, his magnum opus and only known surviving work of the 5th century Indian mathematician in Mathematics. [58] The work was translated into Arabic around 820CE by Al-Khwarizmi.

Even during the middle ages, education in India was imparted orally. Education was provided to the individuals free of cost. It was considered holy and honorable to do so. The ruling king did not provide any funds for education but it was the people belonging to the Hindu religion who donated for the preservation of the Hindu education. The centres of Hindu learning, which were the universities, were set up in places where the scholars resided. These places also became places of pilgrimage. So, more and more pilgrims funded these institutions. [59]

After Muslims started ruling India, there was a rise in the spread of Islamic education. The main aim of Islamic education included the acquisition of knowledge, propagation of Islam and Islamic social morals, preservation and spread of Muslim culture etc. Educations was mainly imparted through Maqtabs, Madrassahas and Mosques. Their education was usually funded by the noble or the landlords. The education was imparted orally and the children learnt a few verses from the Quran by rote. [60]

Indigenous education was widespread in India in the 18th century, with a school for every temple, mosque or village in most regions of the country. [61] The subjects taught included Reading, Writing, Arithmetic, Theology, Law, Astronomy, Metaphysics, Ethics, Medical Science and Religion. The schools were attended by students representative of all classes of society. [62]

The history of education in Japan dates back at least to the 6th century, when Chinese learning was introduced at the Yamato court. Foreign civilizations have often provided new ideas for the development of Japan’s own culture.

Chinese teachings and ideas flowed into Japan from the sixth to the 9th century. Along with the introduction of Buddhism came the Chinese system of writing and its literary tradition, and Confucianism.

By the 9th century, Heian-kyō (today’s Kyoto), the imperial capital, had five institutions of higher learning, and during the remainder of the Heian period, other schools were established by the nobility and the imperial court. During the medieval period (1185–1600), Zen Buddhist monasteries were especially important centers of learning, and the Ashikaga School, Ashikaga Gakko, flourished in the 15th century as a center of higher learning.

Central and South American Civilizations – Aztec and Inca

Aztec is a term used to refer to certain ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who achieved political and military dominance over large parts of Mesoamerica in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, a period referred to as the Late post-Classic period in Mesoamerican chronology.

Until the age of fourteen, the education of children was in the hands of their parents, but supervised by the authorities of their calpōlli . Part of this education involved learning a collection of sayings, called huēhuetlàtolli (“sayings of the old”), that embodied the Aztecs’ ideals. Judged by their language, most of the huēhuetlàtolli seemed to have evolved over several centuries, predating the Aztecs and most likely adopted from other Nahua cultures.

At 15, all boys and girls went to school. There were two types of schools: the telpochcalli , for practical and military studies, and the calmecac , for advanced learning in writing, astronomy, statesmanship, theology, and other areas. The two institutions seem to be common to the Nahua people, leading some experts to suggest that they are older than the Aztec culture.

Aztec teachers ( tlatimine ) propounded a spartan regime of education with the purpose of forming a stoical people.

Girls were educated in the crafts of home and child raising. They were not taught to read or write. All women were taught to be involved in religion; there are paintings of women presiding over religious ceremonies, but there are no references to female priests.

Inca education during the time of the Inca Empire in the 15th and 16th centuries was divided into two principal spheres: education for the upper classes and education for the general population. The royal classes and a few specially chosen individuals from the provinces of the Empire were formally educated by the Amautas (wise men), while the general population learned knowledge and skills from their immediate forebears.

The Amautas constituted a special class of wise men similar to the bards of Great Britain. They included illustrious philosophers, poets, and priests who kept the oral histories of the Incas alive by imparting the knowledge of their culture, history, customs and traditions throughout the kingdom. Considered the most highly educated and respected men in the Empire, the Amautas were largely entrusted with educating those of royal blood, as well as other young members of conquered cultures specially chosen to administer the regions. Thus, education throughout the territories of the Incas was socially discriminatory, most people not receiving the formal education that royalty received.

The official language of the empire was Quechua, although dozens if not hundreds of local languages were spoken. The Amautas did ensure that the general population learn Quechua as the language of the Empire, much in the same way the Romans promoted Latin throughout Europe; however, this was done more for political reasons than educational ones.

After the 15th Century to the Modern World

In the 1950s, The Communist Party oversaw the rapid expansion of primary education throughout China. At the same time, it redesigned the primary school curriculum to emphasize the teaching of practical skills in an effort to improve the productivity of future workers. Paglayan [63] notes that Chinese news sources during this time cited the eradication of illiteracy as necessary “to open the way for development of productivity and technical and cultural revolution”. [64] Chinese government officials noted the interrelationship between education and “productive labor” [65] Like in the Soviet Union, the Chinese government expanded education provision among other reasons to improve their national economy.

Modern systems of education in Europe derive their origins from the schools of the High Middle Ages. Most schools during this era were founded upon religious principles with the primary purpose of training the clergy. Many of the earliest universities, such as the University of Paris founded in 1160, had a Christian basis. In addition to this, a number of secular universities existed, such as the University of Bologna, founded in 1088. Free education for the poor was officially mandated by the Church in 1179 when it decreed that every cathedral must assign a master to teach boys too poor to pay the regular fee; [66] parishes and monasteries also established free schools teaching at least basic literary skills. With few exceptions, priests and brothers taught locally, and their salaries were frequently subsidized by towns. Private, independent schools reappeared in medieval Europe during this time, but they, too, were religious in nature and mission. [67] The curriculum was usually based around the trivium and to a lesser extent quadrivium (the seven Artes Liberales or Liberal arts) and was conducted in Latin, the lingua franca of educated Western Europe throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance. [68]

In northern Europe this clerical education was largely superseded by forms of elementary schooling following the Reformation. In Scotland, for instance, the national Church of Scotland set out a programme for spiritual reform in January 1561 setting the principle of a school teacher for every parish church and free education for the poor. This was provided for by an Act of the Parliament of Scotland, passed in 1633, which introduced a tax to pay for this programme. Although few countries of the period had such extensive systems of education, the period between the 16th and 18th centuries saw education become significantly more widespread. [69]

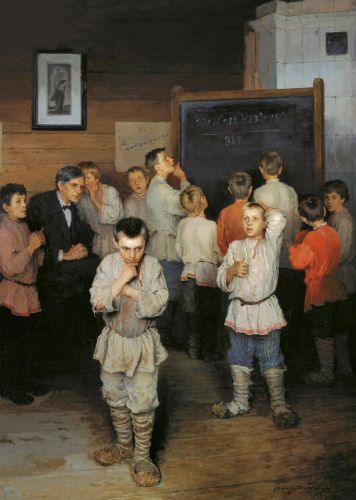

Herbart developed a system of pedagogy widely used in German-speaking areas. Mass compulsory schooling started in Prussia c1800 to “produce more soldiers and more obedient citizens”

In Central Europe, the 17th century scientist and educator John Amos Comenius promulgated a reformed system of universal education that was widely used in Europe. Its growth resulted in increased government interest in education. In the 1760s, for instance, Ivan Betskoy was appointed by the Russian Tsarina, Catherine II, as educational advisor. He proposed to educate young Russians of both sexes in state boarding schools, aimed at creating “a new race of men”. Betskoy set forth a number of arguments for general education of children rather than specialized one: “in regenerating our subjects by an education founded on these principles, we will create… new citizens.” Some of his ideas were implemented in the Smolny Institute that he established for noble girls in Saint Petersburg. [70]

Poland established in 1773 of a Commission of National Education (Polish: Komisja Edukacji Narodowej , Lithuanian: Nacionaline Edukacine Komisija ). The commission functioned as the first government Ministry of Education in a European country. [71]

By the 18th century, universities published academic journals; by the 19th century, the German and the French university models were established. The French established the Ecole Polytechnique in 1794 by the mathematician Gaspard Monge during the French Revolution, and it became a military academy under Napoleon I in 1804. The German university — the Humboldtian model — established by Wilhelm von Humboldt was based upon Friedrich Schleiermacher’s liberal ideas about the importance of seminars, and laboratories. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the universities concentrated upon science, and served an upper class clientele. Science, mathematics, theology, philosophy, and ancient history comprised the typical curriculum.

Increasing academic interest in education led to analysis of teaching methods and in the 1770s the establishment of the first chair of pedagogy at the University of Halle in Germany. Contributions to the study of education elsewhere in Europe included the work of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi in Switzerland and Joseph Lancaster in Britain.

In 1884, a groundbreaking education conference was held in London at the International Health Exhibition, attracting specialists from all over Europe. [72]

In the late 19th century, most of West, Central, and parts of East Europe began to provide elementary education in reading, writing, and arithmetic, partly because politicians believed that education was needed for orderly political behavior. As more people became literate, they realized that most secondary education was only open to those who could afford it. Having created primary education, the major nations had to give further attention to secondary education by the time of World War I. [73]

In the 20th century, new directions in education included, in Italy, Maria Montessori’s Montessori schools; and in Germany, Rudolf Steiner’s development of Waldorf education.

In the Ancien Régime before 1789, educational facilities and aspirations were becoming increasingly institutionalized primarily in order to supply the church and state with the functionaries to serve as their future administrators. France had many small local schools where working-class children — both boys and girls — learned to read, the better to know, love and serve God. The sons and daughters of the noble and bourgeois elites, however, were given quite distinct educations: boys were sent to upper school, perhaps a university, while their sisters perhaps were sent for finishing at a convent. The Enlightenment challenged this old ideal, but no real alternative presented itself for female education. Only through education at home were knowledgeable women formed, usually to the sole end of dazzling their salons. [74]

The modern era of French education begins in the 1790s. The Revolution in the 1790s abolished the traditional universities. [75] Napoleon sought to replace them with new institutions, the Polytechnique, focused on technology. [76] The elementary schools received little attention until 1830, when France copied the Prussian education system.

In 1833, France passed the Guizot Law, the first comprehensive law of primary education in France. This law mandated all local governments to establish primary schools for boys. It also established a common curriculum focused on moral and religious education, reading, and the system of weights and measurements. The expansion of education provision under the Guizot law was largely motivated by the July Monarchy’s desire to shape the moral character of future French citizens with an eye toward promoting social order and political stability.

Jules Ferry, an anti-clerical politician holding the office of Minister of Public Instruction in the 1880s, created the modern Republican school ( l’école républicaine ) by requiring all children under the age of 15—boys and girls—to attend. see Jules Ferry laws Schools were free of charge and secular ( laïque ). The goal was to break the hold of the Catholic Church and monarchism on young people. Catholic schools were still tolerated but in the early 20th century the religious orders sponsoring them were shut down. [77][78]

French colonial officials, influenced by the revolutionary ideal of equality, standardized schools, curricula, and teaching methods as much as possible. They did not establish colonial school systems with the idea of furthering the ambitions of the local people, but rather simply exported the systems and methods in vogue in the mother nation. [79] Having a moderately trained lower bureaucracy was of great use to colonial officials. [80] The emerging French-educated indigenous elite saw little value in educating rural peoples. [81] After 1946 the policy was to bring the best students to Paris for advanced training. The result was to immerse the next generation of leaders in the growing anti-colonial diaspora centered in Paris. Impressionistic colonials could mingle with studious scholars or radical revolutionaries or so everything in between. Ho Chi Minh and other young radicals in Paris formed the French Communist party in 1920. [82]

Tunisia was exceptional. The colony was administered by Paul Cambon, who built an educational system for colonists and indigenous people alike that was closely modeled on mainland France. He emphasized female and vocational education. By independence, the quality of Tunisian education nearly equalled that in France. [83]

African nationalists rejected such a public education system, which they perceived as an attempt to retard African development and maintain colonial superiority. One of the first demands of the emerging nationalist movement after World War II was the introduction of full metropolitan-style education in French West Africa with its promise of equality with Europeans. [84][85]

In Algeria, the debate was polarized. The French set up schools based on the scientific method and French culture. The Pied-Noir (Catholic migrants from Europe) welcomed this. Those goals were rejected by the Moslem Arabs, who prized mental agility and their distinctive religious tradition. The Arabs refused to become patriotic and cultured Frenchmen and a unified educational system was impossible until the Pied-Noir and their Arab allies went into exile after 1962. [86]

In South Vietnam from 1955 to 1975 there were two competing colonial powers in education, as the French continued their work and the Americans moved in. They sharply disagreed on goals. The French educators sought to preserving French culture among the Vietnamese elites and relied on the Mission Culturelle – the heir of the colonial Direction of Education – and its prestigious high schools. The Americans looked at the great mass of people and sought to make South Vietnam a nation strong enough to stop communism. The Americans had far more money, as USAID coordinated and funded the activities of expert teams, and particularly of academic missions. The French deeply resented the American invasion of their historical zone of cultural imperialism. [87]

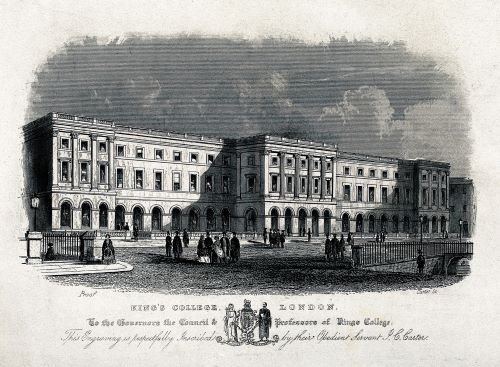

In 1818, John Pounds set up a school and began teaching poor children reading, writing, and mathematics without charging fees. In 1820, Samuel Wilderspin opened the first infant school in Spitalfield. Starting in 1833, Parliament voted money to support poor children’s school fees in England and Wales. [88] In 1837, the Whig Lord Chancellor Henry Brougham led the way in preparing for public education. Most schooling was handled in church schools, and religious controversies between the Church of England And the dissenters became a central theme and educational history before 1900. [89]

The Danish education system has its origin in the cathedral- and monastery schools established by the Church; and seven of the schools established in the 12th and 13th centuries still exist today. After the Reformation, which was officially implemented in 1536, the schools were taken over by the Crown. Their main purpose was to prepare the students for theological studies by teaching them Latin and Greek. Popular elementary education was at that time still very primitive, but in 1721, 240 rytterskoler (“cavalry schools”) were established throughout the kingdom. Moreover, the religious movement of Pietism, spreading in the 18th century, required some level of literacy, thereby promoting the need for public education. Throughout the 19th century (and even up until today), the Danish education system was especially influenced by the ideas of clergyman, politician and poet N. F. S. Grundtvig, who advocated inspiring methods of teaching and the foundation of folk high schools. In 1871, there was a division of the secondary education into two lines: the languages and the mathematics-science line. This division was the backbone of the structure of the Gymnasium (i.e. academic general upper secondary education programme) until the year 2005. [90]

In 1894, the Folkeskole (“public school”, the government-funded primary education system) was formally established (until then, it had been known as Almueskolen (“common school”)), and measures were taken to improve the education system to meet the requirements of industrial society.

In 1903, the 3-year course of the Gymnasium was directly connected the municipal school through the establishment of the mellemskole (‘middle school’, grades 6–9), which was later on replaced by the realskole . Previously, students wanting to go to the Gymnasium (and thereby obtain qualification for admission to university) had to take private tuition or similar means as the municipal schools were insufficient.

In 1975, the realskole was abandoned and the Folkeskole (primary education) transformed into an egalitarian system where pupils go to the same schools regardless of their academic merits.

Shortly after Norway became an archdiocese in 1152, cathedral schools were constructed to educate priests in Trondheim, Oslo, Bergen and Hamar. After the reformation of Norway in 1537, (Norway entered a personal union with Denmark in 1536) the cathedral schools were turned into Latin schools, and it was made mandatory for all market towns to have such a school. In 1736 training in reading was made compulsory for all children, but was not effective until some years later. In 1827, Norway introduced the folkeskole , a primary school which became mandatory for 7 years in 1889 and 9 years in 1969. In the 1970s and 1980s, the folkeskole was abolished, and the grunnskole was introduced. [91]

In 1997, Norway established a new curriculum for elementary schools and middle schools. The plan is based on ideological nationalism, child-orientation, and community-orientation along with the effort to publish new ways of teaching. [92]

In 1842, the Swedish parliament introduced a four-year primary school for children in Sweden, “ folkskola “. In 1882 two grades were added to “ folkskola “, grade 5 and 6. Some “ folkskola ” also had grade 7 and 8, called “ fortsättningsskola “. Schooling in Sweden became mandatory for 7 years in the 1930s and for 8 years in the 1950s and for 9 years in 1962, [93][94]

According to Lars Petterson, the number of students grew slowly, 1900–1947, then shot up rapidly in the 1950s, and declined after 1962. The pattern of birth rates was a major factor. In addition Petterson points to the opening up of the gymnasium from a limited upper social base to the general population based on talent. In addition he points to the role of central economic planning, the widespread emphasis on education as a producer of economic growth and the expansion of white collar jobs. [95]

Japan isolated itself from the rest of the world in the year 1600 under the Tokugawa regime (1600–1867). In 1600 very few common people were literate. By the period’s end, learning had become widespread. Tokugawa education left a valuable legacy: an increasingly literate populace, a meritocratic ideology, and an emphasis on discipline and competent performance. Traditional Samurai curricula for elites stressed morality and the martial arts. Confucian classics were memorized, and reading and recitation of them were common methods of study. Arithmetic and calligraphy were also studied. Education of commoners was generally practically oriented, providing basic three Rs, calligraphy and use of the abacus. Much of this education was conducted in so-called temple schools (terakoya), derived from earlier Buddhist schools. These schools were no longer religious institutions, nor were they, by 1867, predominantly located in temples. By the end of the Tokugawa period, there were more than 11,000 such schools, attended by 750,000 students. Teaching techniques included reading from various textbooks, memorizing, abacus, and repeatedly copying Chinese characters and Japanese script. By the 1860s, 40–50% of Japanese boys, and 15% of the girls, had some schooling outside the home. These rates were comparable to major European nations at the time (apart from Germany, which had compulsory schooling). [96] Under subsequent Meiji leadership, this foundation would facilitate Japan’s rapid transition from feudal society to modern nation which paid very close attention to Western science, technology and educational methods.

After 1868 reformers set Japan on a rapid course of modernization, with a public education system like that of Western Europe. Missions like the Iwakura mission were sent abroad to study the education systems of leading Western countries. They returned with the ideas of decentralization, local school boards, and teacher autonomy. Elementary school enrollments climbed from about 40 or 50 percent of the school-age population in the 1870s to more than 90 percent by 1900, despite strong public protest, especially against school fees.

A modern concept of childhood emerged in Japan after 1850 as part of its engagement with the West. Meiji era leaders decided the nation-state had the primary role in mobilizing individuals – and children – in service of the state. The Western-style school became the agent to reach that goal. By the 1890s, schools were generating new sensibilities regarding childhood. [97] After 1890 Japan had numerous reformers, child experts, magazine editors, and well-educated mothers who bought into the new sensibility. They taught the upper middle class a model of childhood that included children having their own space where they read children’s books, played with educational toys and, especially, devoted enormous time to school homework. These ideas rapidly disseminated through all social classes [98][99]

After 1870 school textbooks based on Confucianism were replaced by westernized texts. However, by the 1890s, a reaction set in and a more authoritarian approach was imposed. Traditional Confucian and Shinto precepts were again stressed, especially those concerning the hierarchical nature of human relations, service to the new state, the pursuit of learning, and morality. These ideals, embodied in the 1890 Imperial Rescript on Education, along with highly centralized government control over education, largely guided Japanese education until 1945, when they were massively repudiated. [100]