Microeconomics: Essay on Microeconomics

Microeconomics studies the economic actions and behaviour of individual units and small groups of individual units.

In microeconomic theory we discuss how the various cells of economic organism, that is, the various units of the economy such as thousands of consumers, thousands of producers or firms, thousands of workers and resource suppliers in the economy do their economic activities and reach their equilibrium states.

“Microeconomics consists of looking at the economy through a microscope, as it were, to see how the millions of cells in the body economic-the individuals or households as consumers, and the individuals or firms as producers—play their part in the working of the whole economic organism.”- Professor Lerner.

In other words, in microeconomics we make a microscopic study of the economy. But it should be remembered that microeconomics does not study the economy in its totality. Instead, in microeconomics we discuss equilibrium of innumerable units of the economy piecemeal and their inter-relationship to each other.

For instance, in microeconomic analysis we study the demand of an individual consumer for a good and from there go on to derive the market demand for the good (that is, demand of a group of individuals consuming a particular good). Likewise, microeconomic theory studies the behaviour of the individual firms in regard to the fixation of price and output and their reactions to the changes in the demand and supply conditions. From there we go on to establish price-output fixation by an industry (Industry means a group of firms producing the same product).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, microeconomic theory seeks to determine the mechanism by which the different economic units attain the position of equilibrium, proceeding from the individual units to a narrowly defined group such as a single industry or a single market. Since microeconomic analysis concerns itself with narrowly defined groups such as an industry or market.

However it does not study the totality of behaviour of all units in the economy for any particular economic activity. In other words, the study of economic system or economy as a whole lies outside the domain of microeconomic analysis.

Microeconomic Theory Studies Resource Allocation, Product and Factor Pricing :

Microeconomic theory takes the total quantity of resources as given and seeks to explain how they are allocated to the production of particular goods. It is the allocation of resources that determines what goods shall be produced and how they shall be produced. The allocation of resources to the production of various goods in a free-market economy depends upon the prices of the various goods and the prices of the various factors of production.

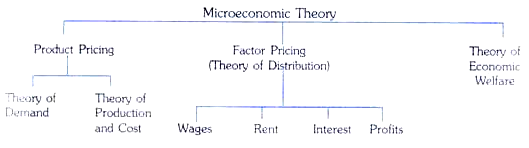

Therefore, to explain how the allocation of resources is determined, microeconomics proceeds to analyse how the relative prices of goods and factors are determined. Thus the theory of product pricing and the theory of factor pricing (or the theory of distribution) falls within the domain of microeconomics.

The theory of product pricing explains how the relative prices of cotton cloth, food grains, jute, kerosene oil and thousands of other goods are determined. The theory of distribution explains how wages (price for the use of labour), rent (payment for the use of land), interest (price for the use of capital) and profits (the reward for the entrepreneur) are determined. Thus, the theory of product pricing and the theory of factor pricing are the two important branches of microeconomic theory.

Prices of the products depend upon the forces of demand and supply. The demand for goods depends upon the consumers’ behaviour pattern, and the supply of goods depends upon the conditions of production and cost and the behaviour pattern of the firms or entrepreneurs. Thus the demand and supply sides have to be analysed in order to explain the determination of prices of goods and factors. Thus the theory of demand and the theory of production are two subdivisions of the theory of pricing.

Microeconomics as a Study of Economic Efficiency:

Besides analysing the pricing of products and factors, and the allocation of resources based upon the price mechanism, microeconomics also seeks to explain whether the allocation of resources determined is efficient. Efficiency in the allocation of resources is attained when the resources are so allocated that maximises the satisfaction of the people.

Economic efficiency involves three efficiencies; efficiency in production, efficiency in distribution of goods among the people (This is also called efficiency in consumption) and allocative economic efficiency, that is, efficiency in the direction of production. Microeconomic theory shows under what conditions these efficiencies are achieved. Microeconomics also shows what factors cause departure from these efficiencies and result in the decline of social welfare from the maximum possible level.

Economic efficiency in production involves minimisation of cost for producing a given level of output or producing a maximum possible output of various goods from the given amount of outlay or cost incurred on productive resources. When such productive efficiency is attained, then it is no longer possible by any reallocation of the productive resources or factors among the production of various goods and services to increase the output of any good without a reduction in the output of some other good.

Efficiency in consumption consists of distributing the given amount of produced goods and services among millions of the people for consumption in such a way as to maximize the total satisfaction of the society. When such efficiency is achieved it is no longer possible by any redistribution of goods among the people to make some people better off without making some other ones worse off. Allocative economic efficiency or optimum direction of production consists of producing those goods which are most desired by the people, that is, when the direction of production is such that maximizes social welfare.

In other words, allocative economic efficiency implies that pattern of production (i.e., amounts of various goods and services produced) should correspond to the desired pattern of consumption of the people. Even if efficiencies in consumption and production of goods are present, it may be that the goods which are produced and distributed for consumption may not be those preferred by the people.

There may be some goods which are more preferred by the people but which have not been produced and vice versa. To sum up, allocative efficiency (optimum direction of production) is achieved when the resources are so allocated to the production of various goods that the maximum possible satisfaction of the people is obtained.

Once this is achieved, then by producing some goods more and others less by any rearrangement of the resources will mean loss of satisfaction or efficiency. The question of economic efficiency is the subject-matter of theoretical welfare economics which is an important branch of microeconomic theory.

That microeconomic theory is intimately concerned with the question of efficiency and welfare is better understood from the following remarks of A. P. Lerner, a noted American economist. “In microeconomics we are more concerned with the avoidance or elimination of waste, or with inefficiency arising from the fact that production is not organised in the most efficient possible manner.

Such inefficiency means that it is possible, by rearranging the different ways in which products are being produced and consumed, to get more of something that is scarce without giving up any part of any other scarce item, or to replace something by something else that is preferred. Microeconomic theory spells out the conditions of efficiency (i.e., for the elimination of all kinds of inefficiency) and suggests how they might be achieved. These conditions (called Pareto-optimal conditions) can be of the greatest help in raising the standard of living of the population.”

The four basic economic questions with which economists are concerned, namely:

(1) What goods shall be produced and in what quantities,

(2) How they shall be produced,

(3) How the goods and services produced shall be distributed, and

(4) Whether the production of goods and their distribution for consumption is efficient fall within the domain of microeconomics.

The whole content of microeconomic theory is presented in the following chart:

Microeconomics and the Economy as a whole:

It is generally understood that microeconomics does not concern itself with the economy as a whole and an impression is created that microeconomics differs from macroeconomics in that whereas the latter examines the economy as a whole; the former is not concerned with it. But this is not fully correct. That microeconomics is concerned with the economy as a whole is quite evident from its discussion of the problem of allocation of resources in the society and judging the efficiency of the same.

Both microeconomics and macroeconomics analyse the economy but with two different ways or approaches. Microeconomics examines the economy, so to say, microscopically, that is, it analyses the behaviour of individual economic units of the economy, their inter-relationships and equilibrium adjustment to each other which determine the allocation of resources in the society. This is known as general equilibrium analysis.

No doubt, microeconomic theory mainly makes particular or partial equilibrium analysis, that is, the analysis of the equilibrium of the individual economic units, taking other things remaining the same. But microeconomic theory, as stated above, also concerns itself with general equilibrium analysis of the economy wherein it is explained how all the economic units, various product markets, various factor markets, money and capital markets are interrelated and interdependent to each other and how through various adjustments and readjustments to the changes in them, they reach a general equilibrium, that is, equilibrium of each of them individually as well as collectively to each other.

Professor A. P. Lerner rightly points out, “Actually microeconomics is much more intimately concerned with the economy as a whole than is macroeconomics, and can even be said to examine the whole economy microscopically. We have seen how economic efficiency is obtained when the “cells” of the economic organism, the households and firms, have adjusted their behaviour to the prices of what they buy and sell. Each cell is then said to be in equilibrium.’ But these adjustments in turn affect the quantities supplied and demanded and therefore also their prices. This means that the adjusted cells then have to readjust themselves. This in turn upsets the adjustment of others again and so on. An important part of microeconomics is examining whether and how all the different cells get adjusted at the same time. This is called general equilibrium analysis in contrast with particular equilibrium or partial equilibrium analysis. General equilibrium analysis is the microscopic examination of the inter-relationships of parts within the economy as a whole. Overall economic efficiency is only a special aspect of this analysis.”

Importance and Uses of Microeconomics:

Microeconomics occupies a vital place in economics and it has both theoretical and practical importance. It is highly helpful in the formulation of economic policies that will promote the welfare of the masses. Until recently, especially before Keynesian Revolution, the body of economics consisted mainly of microeconomics. In spite of the popularity of macroeconomics these days, microeconomics retains its importance, theoretical as well as practical.

It is microeconomics that tells us how a free-market economy with its millions of consumers and producers works to decide about the allocation of productive resources among the thousands of goods and services. As Professor Watson says, “microeconomic theory explains the composition or allocation of total production, why more of some things are produced than of others.”

He further remarks that microeconomic theory “has many uses. The greatest of these is depth in understanding of how a free private enterprise economy operates.” Further, it tells us how the goods and services produced are distributed among the various people for consumption through price or market mechanism. It shows how the relative prices of various products and factors are determined, that is, why the price of cloth is what it is and why the wages of an engineer are what they are and so on.

Moreover, as described above, microeconomic theory explains the conditions of efficiency in consumption and production and highlights the factors which are responsible for the departure from the efficiency or economic optimum. On this basis, microeconomic theory suggests suitable policies to promote economic efficiency and welfare of the people.

Thus, not only does microeconomic theory describe the actual operation of the economy, it has also a normative role in that it suggests policies to eradicate “inefficiency” from the economic system so as to maximize the satisfaction or welfare of the society. The usefulness and importance of microeconomics has been nicely stated by Professor Lerner.

He writes, “Microeconomic theory facilitates the understanding of what would be a hopelessly complicated confusion of billions of facts by constructing simplified models of behaviour which are sufficiently similar to the actual phenomena to be of help in understanding them. These models at the same time enable the economists to explain the degree to which the actual phenomena depart from certain ideal constructions that would most completely achieve individual and social objectives.

They thus help not only to describe the actual economic situation but to suggest policies that would most successfully and most efficiently bring about desired results and to predict the outcomes of such policies and other events. Economics thus has descriptive, normative and predictive aspects.”

We have noted above that microeconomics reveals how a decentralised system of a free private enterprise economy functions without any central control. It also brings to light the fact that the functioning of a complete centrally directed economy with efficiency is impossible. Modern economy is so complex that a central planning authority will find it too difficult to get all the information required for the optimum allocation of resources and to give directions to thousands of production units with various peculiar problems of their own so as to ensure efficiency in the use of resources.

To quote Professor Lerner again, “Microeconomics teaches us that completely ‘direct’ running of the economy is impossible—that a modern economy is so complex that no central planning body can obtain all the information and give out all the directives necessary for its efficient operation.

These would have to include directives for adjusting to continual changes in the availabilities of millions of productive resources and intermediate products, in the known methods of producing everything everywhere, and in the quantities and qualities of the many items to be consumed or to be added to society’s productive equipment.

The vast task can be achieved, and in the past has been achieved, only by the development of a decentralised system whereby the millions of producers and consumers are induced to act in the general interest without the intervention of anybody at the centre with instructions as to what one should make and how and what one should consume.

Microeconomic theory shows that welfare optimum of economic efficiency is achieved when there prevails perfect competition in the product and factor markets. Perfect competition is said to exist when there are so many sellers and buyers in the market so that no individual seller or buyer is in a position to influence the price of a product or factor.

Departure from perfect competition leads to a lower level of welfare, that is, involves loss of economic efficiency. It is in this context that a large part of microeconomic theory is concerned with showing the nature of departures from perfect competition and therefore from welfare optimum (economic efficiency). The power of giant firms or a combination of firms over the output and price of a product constitutes the problem of monopoly.

Microeconomics shows how monopoly leads to misallocation of resources and therefore involves loss of economic efficiency or welfare. It also makes important and useful policy recommendations to regulate monopoly so as to attain economic efficiency or maximum welfare. Like monopoly, monopsony (that is, when a single large buyer or a combination of buyers exercises control over the price) also leads to the loss of welfare and therefore needs to be controlled.

Similarly, microeconomics brings out the welfare implications of oligopoly (or oligopsony) whose main characteristic is that individual sellers (or buyers) have to take into account, while deciding upon their course of action, how their rivals react to their moves regarding changes in price, product and advertising policy.

Another class of departure from welfare optimum is the problem of externalities. Externalities are said to exist when the production or consumption of a commodity affects other people than those who produce, sell or buy it. These externalities may be in the form of either external economies or external diseconomies. External economies prevail when the production or consumption of a commodity by an individual benefits other individuals and external diseconomies prevail when the production or consumption of a commodity by him harms other individuals.

Microeconomic theory reveals that when the externalities exist free working of the price mechanism fails to achieve economic efficiency, since it does not take into account the benefits or harms made to those external to the individual producers and the consumers. The existence of these externalities requires government intervention for correcting imperfections in the price mechanism in order to achieve maximum social welfare.

Several Practical Applications of Microeconomics for Formulating Economic Policies :

Microeconomic analysis is also usefully applied to the various applied branches of economics such as Public Finance, International Economics. It is the microeconomic analysis which is used to explain the factors which determine the distribution of the incidence or burden of a commodity tax between producers or sellers on the one hand and the consumers on the other.

Further, microeconomic analysis is applied to show the damage done to the social welfare or economic efficiency by the imposition of a tax. If it is assumed that resources are optimally allocated or maximum social welfare prevails before the imposition of a tax, it can be demonstrated by microeconomic analysis that what amount of the damage will be caused to the social welfare.

The imposition of a tax on a commodity (i.e., indirect tax) will lead to the loss of social welfare by causing deviation from the optimum allocation of resources the imposition of a direct tax (for example, income tax) will not disturb the optimum resource allocation and therefore will not result in loss of social welfare. Further, microeconomic analysis is applied to show the gain from international trade and to explain the factors which determine the distribution of this gain among the participant countries.

Besides, microeconomics finds application in the various problems of international economics. Whether devaluation will succeed in correcting the disequilibrium in the balance of payments depends upon the elasticity’s of demand and supply of exports and imports. Furthermore, the determination of the foreign exchange rate of a currency, if it is free to vary, depends upon the demand for and supply of that currency. We thus see that microeconomic analysis is a very useful and important branch of modern economic theory.

Related Articles:

- Microeconomics: Notes on Meaning of Microeconomics – Discussed!

- Difference between Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

- Difference between Macroeconomics and Microeconomics

- Essay on Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 Welcome to Economics

1.1 introduction, the complexity of the economy.

The economy is complex.

A simple sentence to start the semester, but something that is important to remember as we move through this semester. Even if you take both introductory microeconomics and macroeconomics, you will only scratch the surface of how complex the economy is. Consider this scenario below.

Pretend that you intend to construct a regular yellow pencil. What do you need? You will need some wood (cedar wood to be specific), graphite (which comprises the “lead” in the pencil), rubber for the eraser, and metal for the ferrule (the band on the top that connects the eraser to the rest of the pencil.) But, where will you find the wood? Will you need to cut down a tree? If so, where will you find the resources needed to do that like a saw, goggles, gasoline for the saw, etc. Already you are seeing the sheer number of connections before we even have a felled tree. To create something as simple as a pencil, we require the assistance of thousands, or more likely tens of thousands, of others. Now, consider an iPhone or a Galaxy tablet and the sheer increase in complexity with these goods.

The scenario above is not something I came up with. Instead, it is a scenario that countless students have been exposed to over the past half-century. In 1958, Leonard Read published I, Pencil which is the story of the life of a pencil. If you would like to read the short story, you can visit the Foundation for Economic Education or you can also watch a short movie adapted from the book by the Competitive Enterprise Institute .

The Central Problem of Economics

Many students come into economics not really knowing what they will learn. Some students think issues like taxes and the stock market will be discussed. Others believe this is a course about money. None of those things are true. Instead, economics is the study of decision-making due to scarcity of resources.

As humans, our wants are unlimited. While we all have basic needs like food, water, and shelter, it is our desire for wants that puts a strain on the economy. Therefore, we need to decide how to best use our scarce resources. This is the crux of the study of economics.

Over the next several sections we will discuss the ways that individuals make decisions and the way those decisions impacts groups of people. These pillars of economic thought will guide us through the rest of the semester.

1.2 The Individual and the Decisions they Make

In this section, we will discuss the ways that individuals make decisions. This will be our first set of the pillars of economic thought.

Trade-offs and their Costs

Pillar 1: we all face trade-offs..

From Wikipedia: Trade-off

A trade-off (or trade-off ) is a situational decision that involves diminishing or losing one quality, quantity or property of a set or design in return for gains in other aspects. In simple terms, a trade-off is where one thing increases and another must decrease. Trade-offs stem from limitations of many origins, including simple physics – for instance, only a certain volume of objects can fit into a given space, so a full container must remove some items in order to accept any more, and vessels can carry a few large items or multiple small items. Trade-offs also commonly refer to different configurations of a single item, such as the tuning of strings on a guitar to enable different notes to be played, as well as allocation of time and attention towards different tasks.

The concept of a trade-off suggests a tactical or strategic choice made with full comprehension of the advantages and disadvantages of each setup. An economic example is the decision to invest in stocks, which are risky but carry great potential return, versus bonds, which are generally safer but with lower potential returns.

Every decision we make comes with lost opportunity. If you choose to attend Penn State, that means that you cannot attend West Virginia University. If you choose to have a hamburger for lunch, you are also choosing to not have pizza or chicken tenders for lunch (unless you are really hungry, of course!) If you spend $1 on one item, you are also losing the ability to spend that dollar on another item.

The same thing goes for businesses and the government. If a company has a scare number of resources, they have to decide how to best use them. Suppose that a restaurant has a surplus of $2,000 to spend to introduce new items. They can either buy a new ice cream machine or a new salad bar. If they choose to buy the ice cream machine, that means they have also decided not to get a salad bar.

Similarly, when the government decides to spend an additional $100 million on highways, it also means that said money is no longer available for education, veteran’s affairs, or environmental protection.

Pillar 2: A cost is more than just money.

From Wikipedia: Trade Off and Wikipedia: Opportunity Cost

In economics , a trade-off is expressed in terms of the opportunity cost of a particular choice, which is the loss of the most preferred alternative given up. A trade-off, then, involves a sacrifice that must be made to obtain a certain product, service or experience, rather than others that could be made or obtained using the same required resources. For example, for a person going to a basketball game, their opportunity cost is the loss of the alternative of watching a particular television program at home. If the basketball game occurs during her or his working hours, then the opportunity cost would be several hours of lost work, as she/he would need to take time off work.

The New Oxford American Dictionary defines it as “the loss of potential gain from other alternatives when one alternative is chosen.” Opportunity cost is a key concept in economics , and has been described as expressing “the basic relationship between scarcity and choice .” [2] The notion of opportunity cost plays a crucial part in attempts to ensure that scarce resources are used efficiently. [3] Opportunity costs are not restricted to monetary or financial costs: the real cost of output forgone , lost time, pleasure or any other benefit that provides utility should also be considered an opportunity cost.

Costs can take two forms: explicit costs and implicit costs.

Explicit costs are opportunity costs that involve direct monetary payment by producers. The explicit opportunity cost of the factors of production not already owned by a producer is the price that the producer has to pay for them. For instance, if a firm spends $100 on electrical power consumed, its explicit opportunity cost is $100. [5] This cash expenditure represents a lost opportunity to purchase something else with the $100.

Implicit costs (also called implied, imputed or notional costs) are the opportunity costs that are not reflected in cash outflow but implied by the failure of the firm to allocate its existing (owned) resources, or factors of production to the best alternative use. For example: a manufacturer has previously purchased 1000 tons of steel and the machinery to produce a widget. The implicit part of the opportunity cost of producing the widget is the revenue lost by not selling the steel and not renting out the machinery instead of using it for production.

Example: Suppose you bought two tickets for a total of $100 for a sold out sporting event. You will also spend $70 on gas/parking/food/etc. By going to the sporting event, you must call off of 8 hours of work where you make $10/hour. What is/are the explicit costs? What is/are the implicit costs?

Answer: The explicit cost is the total amount of money you actually paid. This is the $100 on the tickets and the $70 on the other goods. Thus, the explicit costs total $170. The implicit cost is what you gave up or sacrificed. This is going to work. By going to the sporting event, you did not go to work. Therefore, you missed 8 hours of work where you could have earned $80. Thus, the total implicit cost is $80. Note that you did not have to pay $80; instead, it was simply money you did not make (that you could have.)

Example: You have to decide whether to work tomorrow or go to a party with your friend. If you work, you will earn $200. What is the opportunity cost of going to work?

Answer: If you go to work, you will miss out on going to the party (since that is your next best option.) Therefore, the implicit cost here is non-monetary. The implicit cost is the enjoyment you would have received by going to the party.

The Value of a Good or Service

Pillar 3: the value of a good or service is subjective.

From Wikipedia: Value (Economics) E conomic value is a measure of the benefit provided by a good or service to an economic agent . It is generally measured relative to units of currency , and the interpretation is therefore “what is the maximum amount of money a specific actor is willing and able to pay for the good or service”?

Among the competing schools of economic theory, there are differing theories of value .

Economic value is not the same as market price, nor is economic value the same thing as market value . If a consumer is willing to buy a good, it implies that the customer places a higher value on the good than the market price. The difference between the value to the consumer and the market price is called “consumer surplus” [1] . It is easy to see situations where the actual value is considerably larger than the market price: purchase of drinking water is one example. We will discuss consumer surplus later this semester.

Personal Decision-Making

Pillar 4: we assume that people are rational.

From Wikipedia: Rationality

Rationality plays a key role and there are several strands to this. [14] Firstly, there is the concept of instrumentality—basically the idea that people and organizations are instrumentally rational—that is, adopt the best actions to achieve their goals. Secondly, there is an axiomatic concept that rationality is a matter of being logically consistent within your preferences and beliefs. Thirdly, people have focused on the accuracy of beliefs and full use of information—in this view, a person who is not rational has beliefs that don’t fully use the information they have.

We will discuss the idea of information later this semester.

Pillar 5: We assume that rational people think marginally

One term that you will hear about a lot this semester is ‘marginal.’ Whether it is marginal benefit, marginal cost, marginal revenue, or marginal utility, this term is not going away. When we make decisions, we think incrementally. For instance, when looking to buy a new car, you typically set a price range. Let us say that you have found two cars: one costs $10,000 and the other costs $11,000. You will compare what additional features you get for the additional $1,000. At the same time, you are probably not going to decide between a $5,000 used Toyota Camry and a brand-new $325,000 Bentley Mulsanne. Again, we make decisions in increments.

Some examples of marginal variables are:

Marginal Utility Wikipedia: Marginal utility :

In economics , the utility is the satisfaction or benefit derived by consuming a product; thus the marginal utility of a good or service is the change in the utility from an increase in the consumption of that good or service.

Marginal Cost Wikipedia: Marginal cost :

In economics, marginal cost is the change in the total cost that arises when the quantity produced is incremented by one unit, that is, it is the cost of producing one more unit of a good. [1] Intuitively, the marginal cost at each level of production includes the cost of any additional inputs required to produce the next unit. At each level of production and time period being considered, marginal costs include all costs that vary with the level of production, whereas other costs that do not vary with production are considered fixed . For example, the marginal cost of producing an automobile will generally include the costs of labor and parts needed for the additional automobile and not the fixed costs of the factory that have already been incurred. In practice, marginal analysis is segregated into short and long-run cases, so that, over the long run, all costs (including fixed costs) become marginal.

Marginal Revenue Wikipedia: Marginal revenue :

In microeconomics , marginal revenue is the additional revenue that will be generated by increasing product sales by one unit. [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] It can also be described as the unit revenue the last item sold has generated for the firm. [3] [5]

Pillar 6: Incentives matter

From Wikipedia: Incentive

An incentive is a contingent motivator. [1] Traditional incentives are extrinsic motivators which reward actions to yield a desired outcome. The effectiveness of traditional incentives has changed as the needs of Western society have evolved. While the traditional incentive model is effective when there is a defined procedure and goal for a task, Western society started to require a higher volume of critical thinkers, so the traditional model became less effective. [1] Institutions are now following a trend in implementing strategies that rely on intrinsic motivations rather than the extrinsic motivations that the traditional incentives foster.

Some examples of traditional incentives are letter grades in the formal school system and monetary bonuses for increased productivity in the workplace. Some examples of the promotion of intrinsic motivation are Google allowing their engineers to spend 20% of their work time exploring their own interests, [1] and the competency-based education system .

| Type of Incentive | Definition |

|---|---|

| Remunerative/Financial | are said to exist where an agent can expect some form of material reward – especially money – in exchange for acting in a particular way. |

| Moral | are said to exist where a particular choice is widely regarded as the , or as particularly admirable, or where the failure to act in a certain way is condemned as indecent. A person acting on a moral incentive can expect a sense of self-esteem, and approval or even admiration from his community; a person acting against a moral incentive can expect a sense of guilt, and condemnation or even from the community. |

| Coercive | are said to exist where a person can expect that the failure to act in a particular way will result in being used against them (or their loved ones) by others in the community – for example, by inflicting pain in punishment, or by imprisonment, or by confiscating or destroying their possessions. |

Incentive structures, however, are notoriously more tricky than they might appear to people who set them up. Incentives do not only increase motivation, but they also contribute to the self-selection of individuals, as different people are attracted by different incentive schemes depending on their attitudes towards risk, uncertainty, competitiveness. [9] Human beings are both finite and creative; that means that the people offering incentives are often unable to predict all of the ways that people will respond to them. While the promotion of intrinsic motivation is sometimes is employed to avoid this uncertainty, using short term incentives can yield similar results.

For example, decision-makers in for-profit firms often must decide what incentives they will offer to employees and managers to encourage them to act in ways beneficial to the firm. But many corporate policies – especially of the “extreme incentive” variant popular during the 1990s – that aimed to encourage productivity have, in some cases, led to failures as a result of unintended consequences. For example, stock options were intended to boost CEO productivity by offering a remunerative incentive (profits from rising stock prices) for CEOs to improve company performance. But CEOs could get profits from rising stock prices either (1) by making sound decisions and reaping the rewards of a long-term price increase, or (2) by fudging or fabricating accounting information to give the illusion of economic success, and reaping profits from the short-term price increase by selling before the truth came out and prices tanked. The perverse incentives created by the availability of option (2) have been blamed for many of the falsified earnings reports and public statements in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Also there is the trade-off of short term gains at the expense of long term gains or even long term company survival. It is easy to plunder the assets of a previously successful company and show spectacular short term gains only to have the enterprise collapse after those responsible have gotten their incentives and left the organization or industry. Although long term incentives could be part of the incentive system, they have been abandoned in the past 20 years. An example of an organization that used long term incentive programs was Hughes Aircraft and was highly successful until the government forced its divestiture from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute . Recently there has been movement on adopting the benefit corporation or B-Corporation as a way to change the trend away from short term financial incentives to long term financial and non-financial incentives. [10]

Not all for-profit companies used short term financial incentives at levels below the president or very top executive levels. The trend to move financial incentives down the organization hierarchy started in the 1980s as a way to boost what was considered low productivity. Prior to that time the incentives were associated more with customer satisfaction and producing high-quality products. Moving financial incentives down the corporate chain had the unintended consequences of subverting internal processes to save short term costs, forcing obsolescence at the lower levels as investment was deferred or abandoned, and lowering quality. Some of these issues are explored in the British documentary The Trap . This idea of financial incentives and pushing them to the lowest level common denominator has led to a new company structure or organizational ecology where essentially everything is a standalone profit center with the only incentive being short term financial incentives.

1.3 How Our Decisions Affect Others

Society can produce only so much.

From Wikipedia: Rationing

Pillar 7: Rationing is necessary

Because society can only produce so much with our scarce resources, we must ration.

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources, goods, or services, or an artificial restriction of demand. Rationing controls the size of the ration , which is one’s allowed portion of the resources being distributed on a particular day or at a particular time. There are many forms of rationing, and in western civilization, people experience some of them in daily life without realizing it. [1]

Rationing is often done to keep the price below the equilibrium ( market-clearing ) price determined by the process of supply and demand in an unfettered market . Thus, rationing can be complementary to price controls . An example of rationing in the face of rising prices took place in the various countries where there was rationing of gasoline during the 1973 energy crisis .

A reason for setting the price lower than would clear the market may be that there is a shortage, which would drive the market price very high. High prices, especially in the case of necessities, are undesirable with regard to those who cannot afford them. Traditionalist economists argue, however, that high prices act to reduce waste of the scarce resource while also providing an incentive to produce more.

Rationing using ration stamps is only one kind of non-price rationing. For example, scarce products can be rationed using queues. This is seen, for example, at amusement parks , where one pays a price to get in and then need not pay any price to go on the rides. Similarly, in the absence of road pricing , access to roads is rationed in a first-come, first-served queueing process, leading to congestion .

Authorities which introduce rationing often have to deal with the rationed goods being sold illegally on the black market .

Rationing has been instituted during wartime for civilians. For example, each person may be given “ration coupons” allowing him or her to purchase a certain amount of a product each month. Rationing often includes food and other necessities for which there is a shortage, including materials needed for the war effort such as rubber tires, leather shoes , clothing , and fuel .

Rationing of food and water may also become necessary during an emergency, such as a natural disaster or terror attack . In the U.S., the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has established guidelines for civilians on rationing food and water supplies when replacements are not available. According to FEMA standards, every person should have a minimum of 1 US quart (0.95 L) per day of water, and more for children, nursing mothers and the ill. [2]

Trade and Markets

From Wikipedia: Trade

Pillar 8: Trade Can Improve Everyone’s Circumstances

Trade involves the transfer of goods or services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money . A system or network that allows trade is called a market .

Trade is meaningful because it is a mutual agreement. We do not voluntarily enter into a trade if we believe it will make us worse off. You will not always be made better off, as we take risks anytime we enter into a trade, but we believe that, on average, we will make ourselves better off.

Trade exists due to specialization and the division of labor , a predominant form of economic activity in which individuals and groups concentrate on a small aspect of production, but use their output in trades for other products and needs. [2] Trade exists between regions because different regions may have a comparative advantage (perceived or real) in the production of some trade-able commodity —including the production of natural resources scarce or limited elsewhere, or because different regions’ sizes may encourage mass production . [3] In such circumstances, trade at market prices between locations can benefit both locations.

We will discuss trade-in more depth in chapter 2.

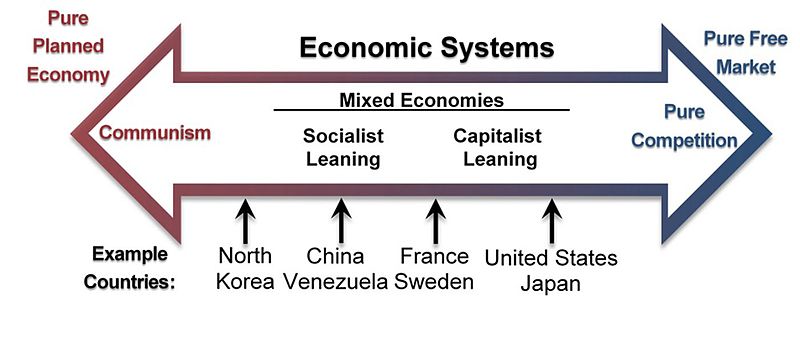

Pillar 9: There are many different ways to organize markets…some better than others

Planned economies.

From Wikipedia: Planned Economy

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment and the allocation of capital goods take place according to economy-wide economic and production plans .

Planned economies are usually associated with Soviet-type central planning , which involves centralized state planning and administrative decision-making. [5] In command economies, important allocation-decisions are made by government authorities and are imposed by law. [6] Planned economies contrast with unplanned economies , specifically market economies , where autonomous firms operating in markets make decisions about production, distribution, pricing, and investment. Market economies that use indicative planning are sometimes referred to [ by whom? ] as “planned market economies”.

The traditional conception of socialism involves the integration of socially-owned economic enterprises via some form of planning with direct calculation substituting factor markets . As such, the concept of a planned economy is often associated [ by whom? ] with socialism and with socialist planning . [7] [8] [9] More recent approaches to socialist planning and allocation have come from some economists and computer scientists proposing planning mechanisms based on advances in computer science and information technology. [10]

Market economies

From Wikipedia: Market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment , production , and distribution are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand . The major characteristic of a market economy is the existence of factor markets that play a dominant role in the allocation of capital and the factors of production . [1] [2]

Market economies range from minimally regulated “ free market ” and laissez-faire systems—where state activity is restricted to providing public goods and services and safeguarding private ownership [3] —to interventionist forms where the government plays an active role in correcting market failures and promoting social welfare . State-directed or dirigist economies are those where the state plays a directive role in guiding the overall development of the market through industrial policies or indicative planning —which guides but does not substitute the market for economic planning —a form sometimes referred to as a mixed economy . [4] [5] [6]

Market economies are contrasted with planned economies where investment and production decisions are embodied in an integrated economy-wide economic plan by a single organizational body that owns and operates the economy’s means of production .

Pillar 10: Market Economies are Driven by the Invisible Hand

From Wikipedia: Invisible hand and Wikipedia: Spontaneous order

The invisible hand is a term used by Adam Smith to describe the unintended social benefits of an individual’s self-interested actions. The phrase was employed by Smith with respect to income distribution (1759) and production (1776). The exact phrase is used just three times in Smith’s writings but has come to capture his notion that individuals’ efforts to pursue their own interest may frequently benefit society more than if their actions were directly intending to benefit society.

The idea of trade and market exchange automatically channeling self-interest toward socially desirable ends is a central justification for the laissez-faire economic philosophy, which lies behind neoclassical economics . [3] In this sense, the central disagreement between economic ideologies can be viewed as a disagreement about how powerful the “invisible hand” is. In alternative models, forces which were nascent during Smith’s lifetime, such as large-scale industry, finance , and advertising, reduce its effectiveness. [4]

Spontaneous order , also named self-organization in the hard sciences , is the spontaneous emergence of order out of seeming chaos. It is a process in social networks including economics , though the term “self-organization” is more often used for physical changes and biological processes , while “spontaneous order” is typically used to describe the emergence of various kinds of social orders from a combination of self-interested individuals who are not intentionally trying to create order through planning . The evolution of life on Earth , language , crystal structure , the Internet and a free market economy have all been proposed as examples of systems which evolved through spontaneous order. [1]

Spontaneous orders are to be distinguished from organizations. Spontaneous orders are distinguished by being scale-free networks , while organizations are hierarchical networks. Further, organizations can be and often are a part of spontaneous social orders, but the reverse is not true. Further, while organizations are created and controlled by humans, spontaneous orders are created, controlled, and controllable by no one. In economics and the social sciences, spontaneous order is defined as “the result of human actions, not of human design”. [2]

Spontaneous order is an equilibrium behavior between self-interested individuals, which is most likely to evolve and survive, obeying the natural selection process “survival of the likeliest”. [3]

Many economic classical liberals, such as Hayek, have argued that market economies are a spontaneous order, “a more efficient allocation of societal resources than any design could achieve.” [7] They claim this spontaneous order (referred to as the extended order in Hayek’s The Fatal Conceit ) is superior to any order a human mind can design due to the specifics of the information required. [8] Centralized statistical data cannot convey this information because the statistics are created by abstracting away from the particulars of the situation. [9]

In a market economy, price is the aggregation of information acquired when the people who own resources are free to use their individual knowledge . Price then allows everyone dealing in a commodity or its substitutes to make decisions based on more information than he or she could personally acquire, information not statistically conveyable to a centralized authority. Interference from a central authority which affects price will have consequences they could not foresee because they do not know all of the particulars involved.

According to Barry, this is illustrated in the concept of the invisible hand proposed by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations . [1] Thus in this view by acting on information with greater detail and accuracy than possible for any centralized authority, a more efficient economy is created to the benefit of a whole society.

Lawrence Reed , president of the Foundation for Economic Education , describes spontaneous order as follows:

Spontaneous order is what happens when you leave people alone—when entrepreneurs… see the desires of people… and then provide for them. They respond to market signals, to prices. Prices tell them what’s needed and how urgently and where. And it’s infinitely better and more productive than relying on a handful of elites in some distant bureaucracy. [10]

The Role of Government

Pillar 11: government can fix economic problems.

The government can, in the broadest of terms, improve market outcomes in the following three ways:

- The government can create and enforce rules to protect institutions.

- The government can promote efficiency in order to minimize market failures.

- The government can promote equity by creating policies to reduce gaps in economic well-being.

Property rights will be discussed in the next pillar, but let us look at efficiency and equity first.

From Wikipedia: Equity (economics)

Equity or economic equality is the concept or idea of fairness in economics , particularly in regard to taxation or welfare economics. More specifically, it may refer to equal life chances regardless of identity, to provide all citizens with a basic and equal minimum of income, goods, and services or to increase funds and commitment for redistribution. [1]

Inequality and inequities have significantly increased in recent decades, possibly driven by the worldwide economic processes of globalization, economic liberalization, and integration. [2] This has led to states ‘lagging behind’ on headline goals such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and different levels of inequity between states have been argued to have played a role in the impact of the global economic crisis of 2008–2009 . [2]

Equity is based on the idea of moral equality . [2] Equity looks at the distribution of capital, goods, and access to services throughout an economy and is often measured using tools such as the Gini index . Equity may be distinguished from economic efficiency in the overall evaluation of social welfare. Although ‘equity’ has broader uses, it may be posed as a counterpart to economic inequality in yielding a “good” distribution of wealth. It has been studied in experimental economics as inequity aversion . Low levels of equity are associated with life chances based on inherited wealth, social exclusion and the resulting poor access to basic services and intergenerational poverty resulting in a negative effect on growth, financial instability, crime, and increasing political instability. [2]

The state often plays a central role in the necessary redistribution required for equity between all citizens, but applying this in practice is highly complex and involves contentious choices.

From Wikipedia: Productive efficiency

Productive efficiency is a situation in which the economy could not produce any more of one good without sacrificing the production of another good. In other words, productive efficiency occurs when a good or service is produced at the lowest possible cost. The concept is illustrated on a production possibility frontier (PPF), where all points on the curve are points of productive efficiency. [1] An equilibrium may be productively efficient without being allocatively efficient — i.e. it may result in a distribution of goods where social welfare is not maximized. It is one type of economic efficiency .

Productive efficiency requires that all firms operate using best-practice technological and managerial processes. By improving these processes, an economy or business can extend its production possibility frontier outward, so that efficient production yields more output than previously.

Productive inefficiency, with the economy operating below its production possibilities frontier, can occur because the productive inputs physical capital and labor are underutilized—that is, some capital or labor is left sitting idle—or because these inputs are allocated in inappropriate combinations to the different industries that use them.

Due to the nature and culture of monopolistic companies, they may not be productively efficient because of X-inefficiency , whereby companies operating in a monopoly have less of an incentive to maximize output due to lack of competition. However, due to economies of scale, it can be possible for the profit-maximizing level of output of monopolistic companies to occur with a lower price to the consumer than perfectly competitive companies.

The Trade-off Between Efficiency and Equity

One issue that the modern economy faces is that of uneven economic growth. As the world continues to grow, some people, countries, and groups grow slower than others. When that growth is compounding over many years, the difference becomes staggering. Therefore, the following trade-off persist. If we promote policies focused on equity, we need to remove resources from the most successful and redistribute them to the least successful. But this is removing resources from those that are able to do the most with them. On the other hand, policies that are only concerned with efficiency allow for increasing inequality which also poses its own threat to the economy.

As an analogy, we can think of economics as the size of a pie and equity as the distribution of the pie.

Pillar 12: Property rights have the ability to increase economic activity

From Wikipedia: Property rights (economics)

Property rights are theoretical socially-enforced constructs in economics for determining how a resource or economic good is used and owned . [1] Resources can be owned by (and hence be the property of) individuals, associations or governments. [2] Property rights can be viewed as an attribute of an economic good. This attribute has four broad components [3] and is often referred to as a bundle of rights : [4]

- the right to use the good

- the right to earn income from the good

- the right to transfer the good to others

- the right to enforce property rights

In economics, the property is usually considered to be ownership ( rights to the proceeds generated by the property ) and control over a resource or good. Many economists effectively argue that property rights need to be fixed and need to portray the relationships among other parties in order to be more effective. [5]

1.4 Pitfalls to Avoid in Economic Thinking

Good intentions do not guarantee desirable outcomes.

From Wikipedia: Unintended consequences

In the social sciences , unintended consequences (sometimes unanticipated consequences or unforeseen consequences ) are outcomes that are not the ones foreseen and intended by a purposeful action. The term was popularised in the twentieth century by American sociologist Robert K. Merton . [1]

Unintended consequences can be grouped into three types:

- Unexpected benefit : A positive unexpected benefit (also referred to as luck , serendipity or a windfall ).

- Unexpected drawback : An unexpected detriment occurring in addition to the desired effect of the policy (e.g., while irrigation schemes provide people with water for agriculture, they can increase waterborne diseases that have devastating health effects, such as schistosomiasis ).

- Perverse result : A perverse effect contrary to what was originally intended (when an intended solution makes a problem worse). This is sometimes referred to as ‘backfire’.

Examples of Unexpected Drawbacks

The implementation of a profanity filter by AOL in 1996 had the unintended consequence of blocking residents of Scunthorpe , North Lincolnshire , England from creating accounts due to a false positive . [24] The accidental censorship of innocent language, known as the Scunthorpe problem , has been repeated and widely documented. [25] [26] [27]

The objective of microfinance initiatives is to foster micro-entrepreneurs but an unintended consequence can be informal intermediation: That is, some entrepreneurial borrowers become informal intermediaries between microfinance initiatives and poorer micro-entrepreneurs. Those who more easily qualify for microfinance split loans into smaller credit to poorer borrowers. Informal intermediation ranges from casual intermediaries at the good or benign end of the spectrum to ‘loan sharks’ at the professional and sometimes criminal end of the spectrum. [28] [ clarification needed ]

In 1990, the Australian state of Victoria made safety helmets mandatory for all bicycle riders. While there was a reduction in the number of head injuries, there was also an unintended reduction in the number of juvenile cyclists—fewer cyclists obviously leads to fewer injuries, assuming all else being equal . The risk of death and serious injury per cyclist seems to have increased, possibly due to risk compensation . [29] Research by Vulcan, et al. found that the reduction in juvenile cyclists was because the youths considered wearing a bicycle helmet unfashionable. [30] A health-benefit model developed at Macquarie University in Sydney suggests that, while helmet use reduces “the risk of head or brain injury by approximately two-thirds or more”, the decrease in exercise caused by reduced cycling as a result of helmet laws is counterproductive in terms of net health. [31]

Prohibition in the 1920s United States , originally enacted to suppress the alcohol trade, drove many small-time alcohol suppliers out of business and consolidated the hold of large-scale organized crime over the illegal alcohol industry. Since alcohol was still popular, criminal organizations producing alcohol were well-funded and hence also increased their other activities. Similarly, the War on Drugs , intended to suppress the illegal drug trade , instead of increased the power and profitability of drug cartels who became the primary source of the products. [32] [33] [34] [35]

In CIA jargon , “ blowback ” describes the unintended, undesirable consequences of covert operations, such as the funding of the Afghan Mujahideen and the destabilization of Afghanistan contributing to the rise of the Taliban and Al-Qaeda . [36] [37] [38]

The introduction of exotic animals and plants for food, for decorative purposes, or to control unwanted species often leads to more harm than good done by the introduced species.

- The introduction of rabbits in Australia and New Zealand for food was followed by explosive growth in the rabbit population; rabbits have become a major feral pest in these countries. [39] [40]

- Cane toads , introduced into Australia to control canefield pests, were unsuccessful and have become a major pest in their own right.

- Kudzu , introduced to the US as an ornamental plant in 1876 [41] and later used to prevent erosion in earthworks, has become a major problem in the Southeastern United States. Kudzu has displaced native plants and has effectively taken over significant portions of land. [42] [43]

The protection of the steel industry in the United States reduced the

production of steel in the United States, increased costs to users, and increased unemployment in associated industries. [44] [45]

Examples of Perverse Results

In 2003, Barbra Streisand unsuccessfully sued Kenneth Adelman and Pictopia.com for posting a photograph of her home online. [46] Before the lawsuit had been filed, only 6 people had downloaded the file, two of them Streisand’s attorneys. [47] The lawsuit drew attention to the image, resulting in 420,000 people visiting the site. [48] The Streisand effect was named after this incident, describing when an attempt to censor or remove a certain piece of information instead draws attention to the material being suppressed, resulting in the material instead becoming widely known, reported on, and distributed. [49]

Passenger-side airbags in motorcars were intended as a safety feature, but led to an increase in child fatalities in the mid-1990s as small children were being hit by deploying airbags during collisions. The supposed solution to this problem, moving the child seat to the back of the vehicle, led to an increase in the number of children forgotten in unattended vehicles, some of whom died under extreme temperature conditions. [50]

Risk compensation, or the Peltzman effect , occurs after implementation of safety measures intended to reduce injury or death (e.g. bike helmets, seatbelts, etc.). People may feel safer than they really are and take additional risks which they would not have taken without the safety measures in place. This may result in no change, or even an increase, in morbidity or mortality, rather than a decrease as intended.

The British government, concerned about the number of venomous cobra snakes in Delhi, offered a bounty for every dead cobra . This was a successful strategy as large numbers of snakes were killed for the reward. Eventually, enterprising people began breeding cobras for the income. When the government became aware of this, they scrapped the reward program, causing the cobra breeders to set the now-worthless snakes free. As a result, the wild cobra population further increased. The apparent solution for the problem made the situation even worse, becoming known as the Cobra effect .

Theobald Mathew ‘s temperance campaign in 19th-century Ireland resulted in thousands of people vowing never to drink alcohol again. This led to the consumption of diethyl ether , a much more dangerous intoxicant — due to its high flammability — by those seeking to become intoxicated without breaking the letter of their pledge. [51] [52]

It was thought that adding south-facing conservatories to British houses would reduce energy consumption by providing extra insulation and warmth from the sun. However, people tended to use the conservatories as living areas, installing heating and ultimately increasing overall energy consumption. [53]

A reward for lost nets found along the Normandy coast was offered by the French government between 1980 and 1981. This resulted in people vandalizing nets to collect the reward. [54]

Beginning in the 1940s and continuing into the 1960s, the Canadian federal government gave the Catholic Church in Quebec $2.25 per day per psychiatric patient for their cost of care, but only $0.75 a day per orphan. The perverse result is that the orphan children were diagnosed as mentally ill so the church could receive a larger amount of money. This psychiatric misdiagnosis affected up to 20,000 people, and the children are known as the Duplessis Orphans . [55] [56] [57]

There have been attempts to curb the consumption of sugary beverages by imposing a tax on them. However, a study found that reduced consumption was only temporary. Also, there was an increase in the consumption of beer among households. [58]

The New Jersey Childproof Handgun Law , which was intended to protect children from accidental discharge of firearms by forcing all future firearms sold in New Jersey to contain “smart” safety features , has delayed, if not stopped entirely, the introduction of such firearms to New Jersey markets. The wording of the law caused significant public backlash, [59] fuelled by gun rights lobbyists , [60] [61] and several shop owners offering such guns received death threats and stopped stocking them [62] [63] In 2014, 12 years after the law was passed, it was suggested the law be repealed if gun rights lobbyists agree not to resist the introduction of “smart” firearms. [64]

Drug prohibition can lead drug traffickers to prefer stronger, more dangerous substances, that can be more easily smuggled and distributed than other, less concentrated substances. [65]

Televised drug prevention advertisements may lead to increased drug use. [66]

Abstinence-only sex education has been shown to increase teenage pregnancy rates, rather than reduce them, when compared to either comprehensive sex education or no sex education at all. [67]

Increasing usage of search engines , also including recent image search features, has contributed to the ease of which media is consumed. Some abnormalities in usage may have shifted preferences for pornographic film actors, as the producers began using common search queries or tags to label the actors in new roles. [68]

The passage of the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act has led to a reported increase in risky behaviors by sex workers as a result of quashing their ability to seek and screen clients online, forcing them back onto the streets or into the dark web . The ads posted were previously an avenue for advocates to reach out to those wanting to escape the trade. [69]

Association is not Causation

From Wikipedia: Correlation does not imply causation

In statistics , many statistical tests calculate correlations between variables and when two variables are found to be correlated , it is tempting to assume that this shows that one variable causes the other. [1] [2] That “correlation proves causation” is considered a questionable cause logical fallacy when two events occurring together are taken to have established a cause-and-effect relationship. This fallacy is also known as cum hoc ergo propter hoc , Latin for “with this, therefore because of this”, and “false cause”. A similar fallacy, that an event that followed another was necessarily a consequence of the first event, is the post hoc ergo propter hoc ( Latin for “after this, therefore because of this.”) fallacy.

For example, in a widely studied case, numerous epidemiological studies showed that women taking combined hormone replacement therapy (HRT) also had a lower-than-average incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD), leading doctors to propose that HRT was protective against CHD. But randomized controlled trials showed that HRT caused a small but statistically significant increase in risk of CHD. Re-analysis of the data from the epidemiological studies showed that women undertaking HRT were more likely to be from higher socio-economic groups ( ABC1 ), with better-than-average diet and exercise regimens. The use of HRT and decreased incidence of coronary heart disease were coincident effects of a common cause (i.e. the benefits associated with a higher socioeconomic status), rather than a direct cause and effect, as had been supposed. [3]

As with any logical fallacy, identifying that the reasoning behind an argument is flawed does not imply that the resulting conclusion is false. In the instance above, if the trials had found that hormone replacement therapy does in fact have a negative incidence on the likelihood of coronary heart disease the assumption of causality would have been correct, although the logic behind the assumption would still have been flawed. Indeed, a few go further, using correlation as a basis for testing a hypothesis to try to establish a true causal relationship; examples are the Granger causality test, convergent cross-mapping , and Liang-Kleeman information flow [4] . [ clarification needed ]

Fallacy of Composition

From Wikipedia: Fallacy of composition

The fallacy of composition arises when one infers that something is true of the whole from the fact that it is true of some part of the whole (or even of every proper part ). For example: “This tire is made of rubber, therefore the vehicle to which it is a part is also made of rubber.” This is fallacious because vehicles are made with a variety of parts, many of which may not be made of rubber.

This fallacy is often confused with the fallacy of hasty generalization , in which an unwarranted inference is made from a statement about a sample to a statement about the population from which it is drawn.

The fallacy of composition is the converse of the fallacy of division ; it may be contrasted with the case of emergence , where the whole possesses properties not present in the parts.

Slippery Slope

From Wikipedia: Slippery slope

A slippery slope argument ( SSA ), in logic , critical thinking , political rhetoric , and caselaw , is a consequentialist logical device [1] in which a party asserts that a relatively small first step leads to a chain of related events culminating in some significant (usually negative) effect. [2] The core of the slippery slope argument is that a specific decision under debate is likely to result in unintended consequences . The strength of such an argument depends on the warrant , i.e. whether or not one can demonstrate a process that leads to the significant effect. This type of argument is sometimes used as a form of fear mongering , in which the probable consequences of a given action are exaggerated in an attempt to scare the audience. The fallacious sense of “slippery slope” is often used synonymously with continuum fallacy , in that it ignores the possibility of middle ground and assumes a discrete transition from category A to category B. In a non-fallacious sense, including use as a legal principle, a middle-ground possibility is acknowledged, and reasoning is provided for the likelihood of the predicted outcome.

There is no such thing as a free lunch

From Wikipedia: There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch

“ There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch ” (alternatively, “ There is no such thing as a free lunch ” or other variants) is a popular adage communicating the idea that it is impossible to get something for nothing. The acronyms TANSTAAFL , TINSTAAFL , and TNSTAAFL are also used. The phrase was in use by the 1930s, but its first appearance is unknown. [1] The “free lunch” in the saying refers to the nineteenth-century practice in American bars of offering a “ free lunch ” in order to entice drinking customers.

The phrase and the acronym are central to Robert Heinlein’s 1966 science-fiction novel The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress , which helped popularize it. [2] [3] The free-market economist Milton Friedman also increased its exposure and use [1] by paraphrasing it as the title of a 1975 book, [4] and it is used in economics literature to describe opportunity cost . [5] Campbell McConnell writes that the idea is “at the core of economics”. [6]

In economics, TANSTAAFL demonstrates opportunity cost . Greg Mankiw described the concept as follows: “To get one thing that we like, we usually have to give up another thing that we like. Making decisions requires trading off one goal against another.” [17] The idea that there is no free lunch at the societal level applies only when all resources are being used completely and appropriately – i.e., when economic efficiency prevails. If not, a ‘free lunch’ can be had through a more efficient utilization of resources. Or, as Fred Brooks put it, “You can only get something for nothing if you have previously gotten nothing for something.” If one individual or group gets something at no cost, somebody else ends up paying for it. If there appears to be no direct cost to any single individual, there is a social cost . Similarly, someone can benefit for “free” from an externality or from a public good , but someone has to pay the cost of producing these benefits. (See Free rider problem and Tragedy of the commons ).

1.5 Introductory Wrap-up

Economics as a social science.

From Wikipedia: Scientific method

The Scientific Method

The scientific method is an empirical method of knowledge acquisition which has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century. It involves careful observation, which includes rigorous skepticism about what is observed, given that cognitive assumptions about how the world works influence how one interprets a percept . It involves formulating hypotheses , via induction , based on such observations; experimental and measurement-based testing of deductions drawn from the hypotheses; and refinement (or elimination) of the hypotheses based on the experimental findings. These are principles of the scientific method, as opposed to a definitive series of steps applicable to all scientific enterprises. [1] [2] [3]

How Economists (Try to) Use the Scientific Method

From: Openstax: Principles of Microeconomics

John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), one of the greatest economists of the twentieth century, pointed out that economics is not just a subject area but also a way of thinking. Keynes famously wrote in the introduction to a fellow economist’s book: “[Economics] is a method rather than a doctrine, an apparatus of the mind, a technique of thinking, which helps its possessor to draw correct conclusions.” In other words, economics teaches you how to think, not what to think.

Economists see the world through a different lens than anthropologists, biologists, classicists, or practitioners of any other discipline. They analyze issues and problems using economic theories that are based on particular assumptions about human behavior. These assumptions tend to be different than the assumptions an anthropologist or psychologist might use. A theory is a simplified representation of how two or more variables interact with each other. The purpose of a theory is to take a complex, real-world issue and simplify it down to its essentials. If done well, this enables the analyst to understand the issue and any problems around it. A good theory is simple enough to understand, while complex enough to capture the key features of the object or situation you are studying.

Sometimes economists use the term model instead of theory. Strictly speaking, a theory is a more abstract representation, while a model is a more applied or empirical representation. We use models to test theories, but for this course we will use the terms interchangeably.

For example, an architect who is planning a major office building will often build a physical model that sits on a tabletop to show how the entire city block will look after the new building is constructed. Companies often build models of their new products, which are more rough and unfinished than the final product, but can still demonstrate how the new product will work.

Economists carry a set of theories in their heads like a carpenter carries around a toolkit. When they see an economic issue or problem, they go through the theories they know to see if they can find one that fits. Then they use the theory to derive insights about the issue or problem. Economists express theories as diagrams, graphs, or even as mathematical equations. (Do not worry. In this course, we will mostly use graphs.) Economists do not figure out the answer to the problem first and then draw the graph to illustrate. Rather, they use the graph of the theory to help them figure out the answer. Although at the introductory level, you can sometimes figure out the right answer without applying a model, if you keep studying economics, before too long you will run into issues and problems that you will need to graph to solve. We explain both micro and macroeconomics in terms of theories and models. The most well-known theories are probably those of supply and demand, but you will learn a number of others.

Realism versus Understanding

As with many concepts, what you are taught in this class is incomplete. That does not mean it is incorrect; rather, it simply means that we will be excluding pieces of the story. This is done because economists face a trade-off between realism and understanding. What this means is that the more realistic a model is, the more complex it is. On the other hand, if we try to make a model easier to understand, we accomplish this by simplifying certain components therefore making it less realistic (but again, not incorrect.)

For example, say we want to investigate the role of a price increase in the quantity of gasoline purchased. For our purposes, we are interested in the fact that the law of demand would say that an increase in the price of gas will reduce the consumption of gasoline. But in reality, there are other factors at play. For instance, how will an increase in the price of gas impact the availability of alternative fuels (and how will their availability impact the price and consumption of gasoline)? In reality, a change in the price of one good will have impacts on many, many other goods and those impacts have the ability to influence the original good. But, we need not worry about it. Instead, our goal is to study the main relationships, so we simply ignore the other components. If you progress further through the economics courses, you will start to move from understanding to realism.

Ceteris Paribus

From Wikipedia: Ceteris paribus

Ceteris paribus or caeteris paribus is a Latin phrase meaning “other things equal”. English translations of the phrase include “ all other things being equal ” or “ other things held constant ” or “ all else unchanged “. A prediction or a statement about a causal , empirical , or logical relation between two states of affairs is ceteris paribus if it is acknowledged that the prediction, although usually accurate in expected conditions, can fail or the relation can be abolished by intervening factors. [1]