- Thesis Action Plan New

- Academic Project Planner

Literature Navigator

Thesis dialogue blueprint, writing wizard's template, research proposal compass.

- Why students love us

- Rebels Blog

- Why we are different

- All Products

- Coming Soon

Developing a Research Proposal for Qualitative Research: A Step-by-Step Guide

Creating a research proposal for qualitative studies can seem like a huge task. This guide will help you step by step. From understanding the basics to writing the final proposal, we will cover everything you need to know. By the end, you will have a clear plan to follow.

Key Takeaways

- Understanding the basics of qualitative research is important for a strong proposal.

- A clear research question guides your study and ensures it stays on track.

- Choosing the right methods and being ethical are key parts of your research design.

- Recruiting the right participants and using proper sampling methods are crucial.

- Analyzing data carefully and presenting your findings clearly is essential.

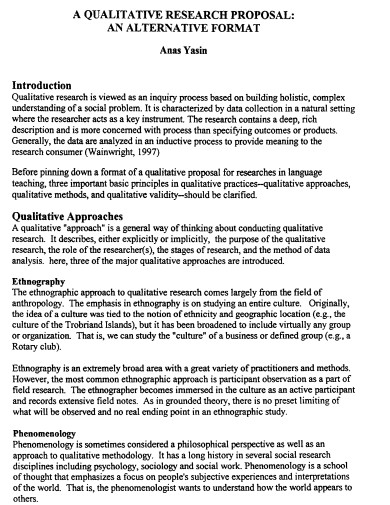

Understanding the Foundations of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is essential for exploring complex social phenomena. It provides an in-depth understanding and rich data analysis, complementing quantitative research. Choosing the right research methodology for your Ph.D. thesis is crucial for obtaining meaningful results.

Formulating a Research Question

Identifying the research problem.

The first step in formulating qualitative research questions is to have a clear understanding of what you aim to discover or understand through your research. How much do we know about the problem? What are the gaps in our knowledge? How would new insights contribute to society or clinical practice? Why is this research worth doing? And who might have an interest in this topic?

Using the SPIDER Tool

The SPIDER tool is a useful framework for defining the research question. SPIDER stands for Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research type. This tool helps in highlighting the gap in knowledge that your research aims to address. It ensures that your research question is focused and researchable, whether through primary or secondary sources.

Ensuring Feasibility and Relevance

After formulating the question(s), you must consider how you will answer it. Answering the question(s) will depend on the question, the design, and the research type. Your research question should be feasible to answer within a given timeframe and specific enough for you to answer thoroughly.

Designing the Research Methodology

After formulating your research question, you must consider how to answer it. Answering the question will depend on the question itself, the design, and the research type.

Selecting Appropriate Methods

Choosing the right methods is crucial. Each design method has pros and cons, and the selection depends on the question, the participants, and the time scale. For example, if you're looking at the experiences of someone who's had severe trauma or exploring a sensitive topic, a one-to-one interview is probably the most appropriate method to respect privacy.

Data Collection Techniques

Data collection is a vital part of your research design . You need to clearly explain your data collection methods so readers understand how you will conduct your study. This section should provide enough detail for readers to evaluate its validity and reliability. Poorly articulated research design can lead to misunderstandings and questions about your study's credibility.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations are paramount in qualitative research. You must ensure that your study respects the rights and dignity of participants. This includes obtaining informed consent, ensuring confidentiality, and being sensitive to the needs and vulnerabilities of your participants. Addressing these ethical issues is not just a formality but a fundamental part of your research design.

Recruiting and Sampling Participants

Defining the target population.

When defining your target population, it's crucial to set clear criteria that align with your research objectives . Quality over quantity is essential; recruiting the right participants ensures the integrity of your study. Sometimes, you might not reach your planned sample size, but it's better to have fewer participants who meet your criteria than to compromise your results.

Sampling Strategies

There is no magic number for how many people you should recruit for qualitative research. The sample sizes are usually smaller than in quantitative research and will depend on many variables. When writing a research proposal, provide justification and rationale for your chosen number of participants. Considerations include the scope of your study and the depth of data you aim to collect.

Recruitment Procedures

Recruitment can be done online via social media or through advertising posters in outpatient clinics. Choose the most convenient method that will link you to the most suitable people. For example, a social media advert might be ideal for a study on e-health, as your cohort should be comfortable using computers. Researchers should avoid directly approaching potential participants to prevent any feeling of obligation to take part. Instead, use a gatekeeper who can act as a go-between to advertise the study to potential participants who meet the criteria.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Coding and thematic analysis.

When we analyze qualitative data , we need systematic, rigorous, and transparent ways of manipulating our data in order to begin developing answers to our research questions. Coding is a crucial first step in this process. It involves labeling segments of data with codes that represent themes or patterns. Using software tools can make this task more efficient and help maintain consistency.

Ensuring Rigor and Trustworthiness

To ensure the rigor and trustworthiness of your analysis, you should employ strategies such as member checking, triangulation, and maintaining an audit trail. Member checking involves sharing your findings with participants to verify accuracy. Triangulation uses multiple data sources or methods to confirm findings. An audit trail documents the research process in detail, providing transparency.

Presenting Findings

Presenting your findings in a clear and organized manner is essential. Use direct quotes from participants to illustrate key themes and provide evidence for your interpretations. Tables can be helpful for summarizing data and highlighting important points. Remember to discuss the implications of your findings and how they contribute to the existing body of knowledge.

Writing the Research Proposal

When preparing a research proposal, it is essential to follow the specific guidelines provided by your institution or program. Some institutions may have additional requirements, such as excluding references, figures, or timelines from the page limit.

Structuring the Proposal

A research proposal is a document that describes the idea, importance, and method of the research. The format can vary widely among different higher education settings, different funders, and different organizations. When thinking of the research proposal, it's your tool to sell the research to probably an ethics committee or a research funder, so you want to show them why your research is important to be done. Here are some prompting questions to help with writing the background:

- What is the main problem or question your research aims to address?

- Why is this research important?

- What are the key objectives of your study?

Writing the Literature Review

The title of your research proposal can be different from the publishing title. It can be considered a working title that you can revisit after finishing the research proposal and amend if needed. "The title" should contain keywords of what your research encompasses, such as:

- The main topic of your research

- The specific aspect you are focusing on

- Any key terms or concepts

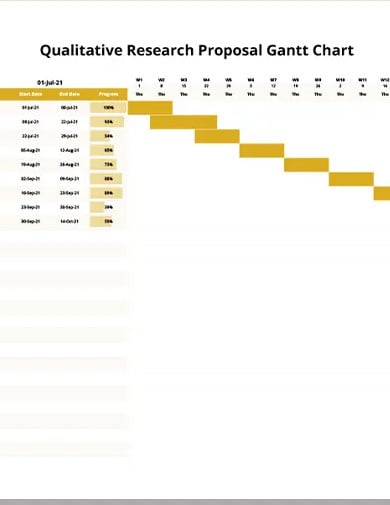

Developing a Timeline

When thinking about how to start thesis , setting clear goals, utilizing online databases, conducting interviews, and collecting relevant data are key steps. The length of your research proposal can vary. Make sure to include a timeline that outlines the major milestones of your research project. This can help you stay on track and ensure that you meet all deadlines.

| Milestone | Expected Completion Date |

|---|---|

| Literature Review | Month 1 |

| Data Collection | Months 2-4 |

| Data Analysis | Months 5-6 |

| Final Write-Up | Month 7 |

By following these tips for researching and organizing your thesis , you can create a strong and compelling research proposal.

Addressing Ethical and Practical Issues

Informed consent.

When conducting qualitative research, obtaining informed consent is crucial. Participants must be fully aware of the study's purpose, procedures, and any potential risks. Mastering the interview process includes ensuring that participants understand their rights and can withdraw at any time without penalty.

Confidentiality and Anonymity

Protecting the privacy of participants is a key aspect of ethical research. Researchers must take steps to ensure that data is stored securely and that identifying information is kept confidential. This includes using pseudonyms and removing any details that could reveal a participant's identity.

Dealing with Practical Challenges

Qualitative research often involves addressing sensitive topics, which can present practical challenges. Researchers need to be prepared to handle emotional responses and provide support if needed. Additionally, defining the research scope clearly can help in managing time and resources effectively.

When tackling ethical and practical issues, it's important to have the right tools and guidance. Our step-by-step Thesis Action Plan is designed to help you navigate these challenges with ease. Whether you're struggling with sleepless nights or feeling overwhelmed, our resources are here to support you. Don't let stress hold you back any longer. Visit our website to learn more and take the first step towards a smoother thesis journey.

In conclusion, developing a qualitative research proposal is a detailed and thoughtful process that requires careful planning and consideration. By following the steps outlined in this guide, researchers can ensure that their proposals are comprehensive and well-structured. This not only helps in gaining approval from review boards but also sets a strong foundation for conducting meaningful and impactful research. Remember, the key to a successful research proposal lies in clarity, coherence, and a thorough understanding of the research topic. With dedication and attention to detail, anyone can master the art of crafting a qualitative research proposal.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a qualitative research proposal.

A qualitative research proposal is a document that outlines the idea, importance, and methods of your research. It helps to plan out how you will collect and analyze non-numerical data.

Why is it important to have a research question?

Having a research question is important because it guides your study. It helps you focus on what you want to find out and keeps your research on track.

What is the SPIDER tool?

The SPIDER tool is a method used to define a research question in qualitative research. It stands for Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research type.

How do you ensure the ethical considerations in qualitative research?

To ensure ethical considerations, you need to get informed consent from participants, protect their confidentiality, and make sure your study does no harm.

What are some common data collection techniques in qualitative research?

Common data collection techniques include interviews, focus groups, and observations. These methods help gather detailed and in-depth information.

How do you present your findings in a qualitative research proposal?

You present your findings by coding the data and identifying themes. Then, you explain these themes and what they mean in relation to your research question.

The Feedback Loop: Navigating Peer Reviews and Supervisor Input

How to conduct a systematic review and write-up in 7 steps (using prisma, pico and ai).

Mastering the Art: How to Write the Thesis Statement of a Research Paper

Cómo escribir una propuesta de investigación para un doctorado

Cómo redactar una revisión de literatura para tu tesis

How to Determine the Perfect Research Proposal Length

How Do I Start Writing My Thesis: A Step-by-Step Guide

From Idea to Proposal: 6 Steps to Efficiently Plan Your Research Project in 2024

Three Months to a Perfect Bachelor Thesis: A Detailed Plan for Students

Conquering Bibliography Fears: Mastering Citations in Thesis Writing

Thesis Action Plan

- Blog Articles

- Affiliate Program

- Terms and Conditions

- Payment and Shipping Terms

- Privacy Policy

- Return Policy

© 2024 Research Rebels, All rights reserved.

Your cart is currently empty.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

| Show your reader why your project is interesting, original, and important. | |

| Demonstrate your comfort and familiarity with your field. Show that you understand the current state of research on your topic. | |

| Make a case for your . Demonstrate that you have carefully thought about the data, tools, and procedures necessary to conduct your research. | |

| Confirm that your project is feasible within the timeline of your program or funding deadline. |

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

| ? or ? , , or research design? | |

| , )? ? | |

| , , , )? | |

| ? |

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

| Research phase | Objectives | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Background research and literature review | 20th January | |

| 2. Research design planning | and data analysis methods | 13th February |

| 3. Data collection and preparation | with selected participants and code interviews | 24th March |

| 4. Data analysis | of interview transcripts | 22nd April |

| 5. Writing | 17th June | |

| 6. Revision | final work | 28th July |

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

7 Writing a proposal

- Published: May 2018

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

When researchers plan to undertake qualitative research with a pilot or full RCT they write a proposal to apply for funding, seek ethical approval, or as part of their PhD studies. These proposals can be published in journals. Guidance for writing a proposal for the qualitative research undertaken with RCTs has been published, and there is existing guidance for writing proposals in related areas such as mixed methods research. In this chapter, existing guidance is introduced and built upon to offer comprehensive and detailed guidance for writing a proposal for the qualitative research undertaken with an RCT. There are challenges to writing these proposals and these are discussed and potential solutions proposed.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 1 |

| November 2022 | 3 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 3 |

| June 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 4 |

| December 2023 | 7 |

| January 2024 | 3 |

| March 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 4 |

| May 2024 | 5 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

| August 2024 | 2 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

How to Write a Research Proposal: (with Examples & Templates)

Table of Contents

Before conducting a study, a research proposal should be created that outlines researchers’ plans and methodology and is submitted to the concerned evaluating organization or person. Creating a research proposal is an important step to ensure that researchers are on track and are moving forward as intended. A research proposal can be defined as a detailed plan or blueprint for the proposed research that you intend to undertake. It provides readers with a snapshot of your project by describing what you will investigate, why it is needed, and how you will conduct the research.

Your research proposal should aim to explain to the readers why your research is relevant and original, that you understand the context and current scenario in the field, have the appropriate resources to conduct the research, and that the research is feasible given the usual constraints.

This article will describe in detail the purpose and typical structure of a research proposal , along with examples and templates to help you ace this step in your research journey.

What is a Research Proposal ?

A research proposal¹ ,² can be defined as a formal report that describes your proposed research, its objectives, methodology, implications, and other important details. Research proposals are the framework of your research and are used to obtain approvals or grants to conduct the study from various committees or organizations. Consequently, research proposals should convince readers of your study’s credibility, accuracy, achievability, practicality, and reproducibility.

With research proposals , researchers usually aim to persuade the readers, funding agencies, educational institutions, and supervisors to approve the proposal. To achieve this, the report should be well structured with the objectives written in clear, understandable language devoid of jargon. A well-organized research proposal conveys to the readers or evaluators that the writer has thought out the research plan meticulously and has the resources to ensure timely completion.

Purpose of Research Proposals

A research proposal is a sales pitch and therefore should be detailed enough to convince your readers, who could be supervisors, ethics committees, universities, etc., that what you’re proposing has merit and is feasible . Research proposals can help students discuss their dissertation with their faculty or fulfill course requirements and also help researchers obtain funding. A well-structured proposal instills confidence among readers about your ability to conduct and complete the study as proposed.

Research proposals can be written for several reasons:³

- To describe the importance of research in the specific topic

- Address any potential challenges you may encounter

- Showcase knowledge in the field and your ability to conduct a study

- Apply for a role at a research institute

- Convince a research supervisor or university that your research can satisfy the requirements of a degree program

- Highlight the importance of your research to organizations that may sponsor your project

- Identify implications of your project and how it can benefit the audience

What Goes in a Research Proposal?

Research proposals should aim to answer the three basic questions—what, why, and how.

The What question should be answered by describing the specific subject being researched. It should typically include the objectives, the cohort details, and the location or setting.

The Why question should be answered by describing the existing scenario of the subject, listing unanswered questions, identifying gaps in the existing research, and describing how your study can address these gaps, along with the implications and significance.

The How question should be answered by describing the proposed research methodology, data analysis tools expected to be used, and other details to describe your proposed methodology.

Research Proposal Example

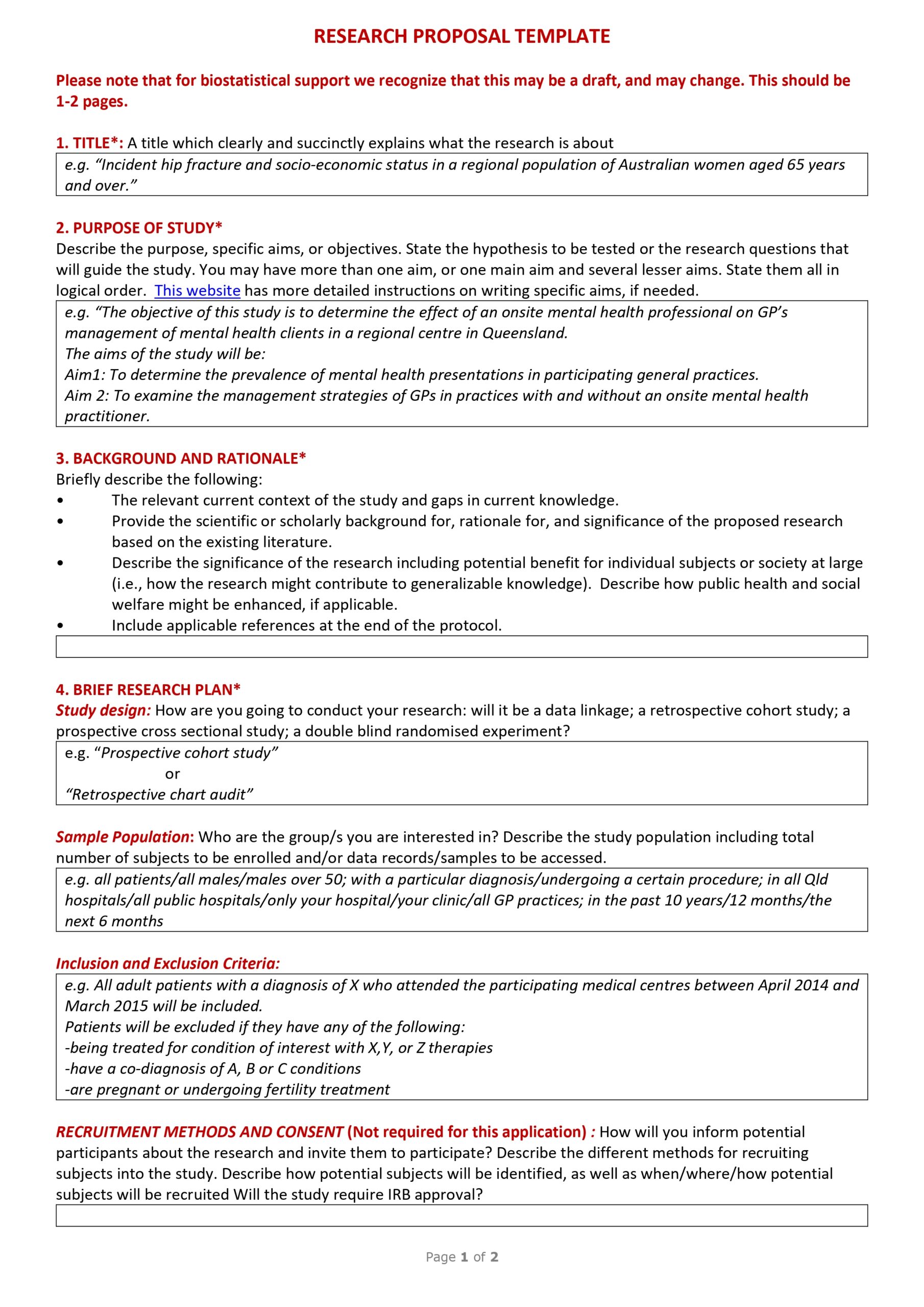

Here is a research proposal sample template (with examples) from the University of Rochester Medical Center. 4 The sections in all research proposals are essentially the same although different terminology and other specific sections may be used depending on the subject.

Structure of a Research Proposal

If you want to know how to make a research proposal impactful, include the following components:¹

1. Introduction

This section provides a background of the study, including the research topic, what is already known about it and the gaps, and the significance of the proposed research.

2. Literature review

This section contains descriptions of all the previous relevant studies pertaining to the research topic. Every study cited should be described in a few sentences, starting with the general studies to the more specific ones. This section builds on the understanding gained by readers in the Introduction section and supports it by citing relevant prior literature, indicating to readers that you have thoroughly researched your subject.

3. Objectives

Once the background and gaps in the research topic have been established, authors must now state the aims of the research clearly. Hypotheses should be mentioned here. This section further helps readers understand what your study’s specific goals are.

4. Research design and methodology

Here, authors should clearly describe the methods they intend to use to achieve their proposed objectives. Important components of this section include the population and sample size, data collection and analysis methods and duration, statistical analysis software, measures to avoid bias (randomization, blinding), etc.

5. Ethical considerations

This refers to the protection of participants’ rights, such as the right to privacy, right to confidentiality, etc. Researchers need to obtain informed consent and institutional review approval by the required authorities and mention this clearly for transparency.

6. Budget/funding

Researchers should prepare their budget and include all expected expenditures. An additional allowance for contingencies such as delays should also be factored in.

7. Appendices

This section typically includes information that supports the research proposal and may include informed consent forms, questionnaires, participant information, measurement tools, etc.

8. Citations

Important Tips for Writing a Research Proposal

Writing a research proposal begins much before the actual task of writing. Planning the research proposal structure and content is an important stage, which if done efficiently, can help you seamlessly transition into the writing stage. 3,5

The Planning Stage

- Manage your time efficiently. Plan to have the draft version ready at least two weeks before your deadline and the final version at least two to three days before the deadline.

- What is the primary objective of your research?

- Will your research address any existing gap?

- What is the impact of your proposed research?

- Do people outside your field find your research applicable in other areas?

- If your research is unsuccessful, would there still be other useful research outcomes?

The Writing Stage

- Create an outline with main section headings that are typically used.

- Focus only on writing and getting your points across without worrying about the format of the research proposal , grammar, punctuation, etc. These can be fixed during the subsequent passes. Add details to each section heading you created in the beginning.

- Ensure your sentences are concise and use plain language. A research proposal usually contains about 2,000 to 4,000 words or four to seven pages.

- Don’t use too many technical terms and abbreviations assuming that the readers would know them. Define the abbreviations and technical terms.

- Ensure that the entire content is readable. Avoid using long paragraphs because they affect the continuity in reading. Break them into shorter paragraphs and introduce some white space for readability.

- Focus on only the major research issues and cite sources accordingly. Don’t include generic information or their sources in the literature review.

- Proofread your final document to ensure there are no grammatical errors so readers can enjoy a seamless, uninterrupted read.

- Use academic, scholarly language because it brings formality into a document.

- Ensure that your title is created using the keywords in the document and is neither too long and specific nor too short and general.

- Cite all sources appropriately to avoid plagiarism.

- Make sure that you follow guidelines, if provided. This includes rules as simple as using a specific font or a hyphen or en dash between numerical ranges.

- Ensure that you’ve answered all questions requested by the evaluating authority.

Key Takeaways

Here’s a summary of the main points about research proposals discussed in the previous sections:

- A research proposal is a document that outlines the details of a proposed study and is created by researchers to submit to evaluators who could be research institutions, universities, faculty, etc.

- Research proposals are usually about 2,000-4,000 words long, but this depends on the evaluating authority’s guidelines.

- A good research proposal ensures that you’ve done your background research and assessed the feasibility of the research.

- Research proposals have the following main sections—introduction, literature review, objectives, methodology, ethical considerations, and budget.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. How is a research proposal evaluated?

A1. In general, most evaluators, including universities, broadly use the following criteria to evaluate research proposals . 6

- Significance —Does the research address any important subject or issue, which may or may not be specific to the evaluator or university?

- Content and design —Is the proposed methodology appropriate to answer the research question? Are the objectives clear and well aligned with the proposed methodology?

- Sample size and selection —Is the target population or cohort size clearly mentioned? Is the sampling process used to select participants randomized, appropriate, and free of bias?

- Timing —Are the proposed data collection dates mentioned clearly? Is the project feasible given the specified resources and timeline?

- Data management and dissemination —Who will have access to the data? What is the plan for data analysis?

Q2. What is the difference between the Introduction and Literature Review sections in a research proposal ?

A2. The Introduction or Background section in a research proposal sets the context of the study by describing the current scenario of the subject and identifying the gaps and need for the research. A Literature Review, on the other hand, provides references to all prior relevant literature to help corroborate the gaps identified and the research need.

Q3. How long should a research proposal be?

A3. Research proposal lengths vary with the evaluating authority like universities or committees and also the subject. Here’s a table that lists the typical research proposal lengths for a few universities.

| Arts programs | 1,000-1,500 | |

| University of Birmingham | Law School programs | 2,500 |

| PhD | 2,500 | |

| 2,000 | ||

| Research degrees | 2,000-3,500 |

Q4. What are the common mistakes to avoid in a research proposal ?

A4. Here are a few common mistakes that you must avoid while writing a research proposal . 7

- No clear objectives: Objectives should be clear, specific, and measurable for the easy understanding among readers.

- Incomplete or unconvincing background research: Background research usually includes a review of the current scenario of the particular industry and also a review of the previous literature on the subject. This helps readers understand your reasons for undertaking this research because you identified gaps in the existing research.

- Overlooking project feasibility: The project scope and estimates should be realistic considering the resources and time available.

- Neglecting the impact and significance of the study: In a research proposal , readers and evaluators look for the implications or significance of your research and how it contributes to the existing research. This information should always be included.

- Unstructured format of a research proposal : A well-structured document gives confidence to evaluators that you have read the guidelines carefully and are well organized in your approach, consequently affirming that you will be able to undertake the research as mentioned in your proposal.

- Ineffective writing style: The language used should be formal and grammatically correct. If required, editors could be consulted, including AI-based tools such as Paperpal , to refine the research proposal structure and language.

Thus, a research proposal is an essential document that can help you promote your research and secure funds and grants for conducting your research. Consequently, it should be well written in clear language and include all essential details to convince the evaluators of your ability to conduct the research as proposed.

This article has described all the important components of a research proposal and has also provided tips to improve your writing style. We hope all these tips will help you write a well-structured research proposal to ensure receipt of grants or any other purpose.

References

- Sudheesh K, Duggappa DR, Nethra SS. How to write a research proposal? Indian J Anaesth. 2016;60(9):631-634. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5037942/

- Writing research proposals. Harvard College Office of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships. Harvard University. Accessed July 14, 2024. https://uraf.harvard.edu/apply-opportunities/app-components/essays/research-proposals

- What is a research proposal? Plus how to write one. Indeed website. Accessed July 17, 2024. https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/research-proposal

- Research proposal template. University of Rochester Medical Center. Accessed July 16, 2024. https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/MediaLibraries/URMCMedia/pediatrics/research/documents/Research-proposal-Template.pdf

- Tips for successful proposal writing. Johns Hopkins University. Accessed July 17, 2024. https://research.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Tips-for-Successful-Proposal-Writing.pdf

- Formal review of research proposals. Cornell University. Accessed July 18, 2024. https://irp.dpb.cornell.edu/surveys/survey-assessment-review-group/research-proposals

- 7 Mistakes you must avoid in your research proposal. Aveksana (via LinkedIn). Accessed July 17, 2024. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/7-mistakes-you-must-avoid-your-research-proposal-aveksana-cmtwf/

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

How to write a phd research proposal.

- What are the Benefits of Generative AI for Academic Writing?

- How to Avoid Plagiarism When Using Generative AI Tools

- What is Hedging in Academic Writing?

How to Write Your Research Paper in APA Format

The future of academia: how ai tools are changing the way we do research, you may also like, dissertation printing and binding | types & comparison , what is a dissertation preface definition and examples , how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), maintaining academic integrity with paperpal’s generative ai writing..., research funding basics: what should a grant proposal..., how to write an abstract in research papers..., how to write dissertation acknowledgements.

Qualitative Research Proposal

Proposal maker.

Writing a qualitative research proposal is just like writing any other research proposals. The only thing is that you are writing specifically designed to provide non-numerical data, concepts and the like. You are more likely to follow a specific format since it is a type of academic writing.

6+ Qualitative Research Proposal Examples

1. qualitative research proposal gantt chart template.

2. Sample Qualitative Research Proposal

Size: 90 KB

3. Proposal in Qualitative Research Template

Size: 15 KB

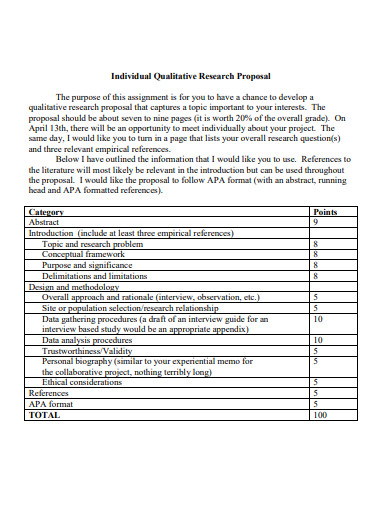

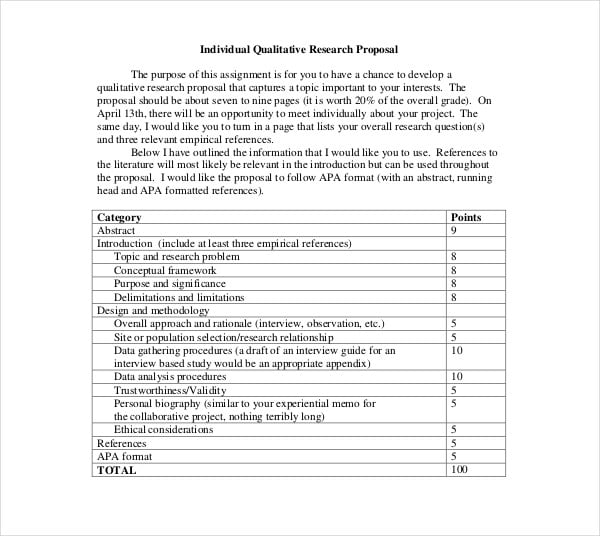

4. Individual Qualitative Research Proposal

5. Qualitative Research Proposal Format

Size: 517 KB

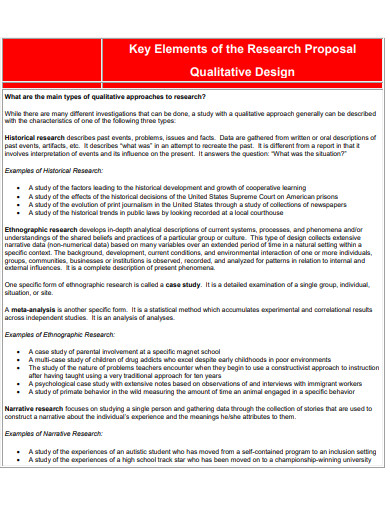

6. Elements of Research Proposal Qualitative Design

Size: 23 KB

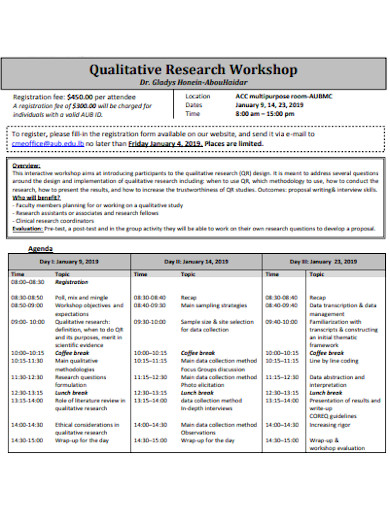

7. Qualitative Research Workshop Proposal

Size: 559 KB

What is a Qualitative Research Proposal?

A qualitative research proposal gives the detailed summary of your research study. It is a type of research proposal that only involves qualitative methods of gathering a certain data such as an interview, observation, questionnaire, or case studies . Qualitative research can be applied in the field of psychology, social sciences and the like.

How to Write a Qualitative Research Proposal?

Think of a unique topic for you to provide a good research title.

Example: A Qualitative Study on Coping up with the Different Levels of Anxiety among Students

Develop Research Questions

Your research questions will be your guide in your research study. It contains the research design, research methodology and the technique you used in collecting data.

Example: What do the architecture and engineering students with anxiety do to cope up with their studies in the university?

For qualitative research, we can use the SPIDER method which stands for Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation and Research type.

Sample refers to your target population that is included in your study.

Example: The population consisted of a community of architecture and engineering students of the oldest university in the city of Manila, Philippines.

Phenomenon of Interest refers to an event or an object. What could be their experience in the university?

Design refers to the methods you used in conducting the study.

- Interview – refers to the one on one interaction with the participant.

- Observation – refers to observing the participants whether or not they are fully aware of the thought that you are observing them.

- Questionnaire – refers to the process of distributing survey questionnaires to gather answers from your participants. It ends with tallying the answers to see what the participants choose the most.

- Case study – refers to an intensive study about a specific person or group of people.

Ensure That Some Ethical Standards are Met

This refers to protecting the privacy or confidentiality of the data you have gathered and the rights of the participants.

“There were more ethical considerations in almost all aspects for drug trials and clinical studies compared with proposals for epidemiological studies. Clinical research studies usually directly involve human subjects, either with preventive, therapeutic, or non-therapeutic procedures. In general, the study procedures in such study designs put human subjects at higher risks, thus there are more ethical concerns. The primary ethical considerations of clinical studies are competent medical treatment and care, alongside an acceptable risk–benefit balance. However, many laboratory research studies use stored specimens, with less invasive procedures, and epidemiology studies usually employ data collection through medical records, CRFs or questionnaires. Ethical issues for the latter, therefore, mainly concern confidentiality and privacy of the study participants. However, it was found that studies that collect new specimens received more comments on ethical issues. There remains debate among RECs about solutions for issues around sample export, storage, and reuse. However, it is recommended that in order to ensure adequate protection of human research subjects participating in scientific research, RECs bear the responsibility of guaranteeing that participants are provided with sufficient detail to be able to provide informed consent as well as to understand the reality of genetic research as it is practiced.”

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Consider writing a plan to be used for the whole duration of your research. this includes the timeline and budget..

Timeline – refers to the target length of time to complete your research.

Budget – refers to the estimation of how much your research would cost. All items that you think might be included in the budgeting must be included.

Don’t Forget to Include Your Reference

This contains the list of the sources that you should cite on the last page of your research. It usually follows the APA format.

How long should a qualitative research proposal be?

Every research proposal should be at least 4 to 7 pages long or depending on the requirement of your professor.

Do we still have to write for the definition of terms in the research proposal?

Yes. You have the option to do so to introduce and define words that are difficult for the readers to understand.

What can be considered as a good topic in writing qualitative research?

Your topic will either be given by your professor or you may look into unique topics into the internet.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Generate a proposal for a new school recycling program

Compose a proposal for a school field trip to a science museum.

All Formats

8+ Qualitative Research Proposal Templates – PDF | Word | Excel

Qualitative research is a way of exploring ideas for developing new products, it is also used to evaluate ideas without the use of statistical and numerical measurements and analyzes in the form of Research Plan Templates. Writing a qualitative research proposal samples follows the same guidelines as every Research Proposal .

Proposal Template Bundle

- Google Docs

Qualitative Research Proposal Gantt Chart Template

Free Sample Qualitative Dissertation Proposal

Free Intellectual Disability Research Proposal Template

How to write Qualitative Research Proposals and Research studies in qualitative

- Choose a subject that will keep your interest from start to finish of the research.

- Keep detailed notes of the literature review to help you write your proposal and make sure you create a sturdy research outline .

- Make sure your terminology is correct in order to show that you have good knowledge of the subject.

- State in your proposal how you will ensure that your research will be of high quality.

- Use a formal writing style for a professional look.

Process of the qualitative proposal

- Choosing a research problem. The problem has to be interesting for the researcher since they are going to spend a lot of time working on it.

- Reviewing the existing literature regarding the research problem.

- Selection of a sample that will be used for the research.

- Selection of the method of data collection.

- Selection of data analysis medium.

- Creation of the outline research.

- Writing and review of the proposal.