Digitalization in Accounting and Financial Reporting Quality: Literature Review

- First Online: 29 October 2023

Cite this chapter

- Latifa Jabor 3 &

- Allam Hamdan 3 , 4

Part of the book series: Contributions to Management Science ((MANAGEMENT SC.))

966 Accesses

1 Citations

Accounting activities are shown in the financial reports of banks, while the relevant literature has found that creative accounting highly impacts the quality of financial reporting. However, previous studies indicated the limited impacts of creative accounting determinants on the quality of financial reporting, whereas the phenomenon of financial reporting quality is still on the track of generating renewed research interest. A deductive research approach driven by a survey questionnaire was used as the research methodology to attain the objectives. Accordingly, purposive sampling was used to collect responses from 63 employees of Arab Bank—Bahrain. The data were analyzed statistically using the SPSS. The results show significant impacts of new technologies on financial reporting quality. Which includes the results of developing financial reports in the high quality of the data presented in the financial reports, as it reduced the time and effort spent in preparing these reports.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of Digitalization on the Accounting Profession

XBRL as a Tool for Integrating Financial and Non-financial Reporting

The Effect of Digital Accounting Systems Within Digital Transformation on Financial Information’s Quality

ACCA (2020) The digital accountant: digital skills in a transformed world. ACCA Global, London, UK

Google Scholar

Akter S, Michael K, Uddin MR, McCarthy G, Rahman M (2020) Transforming business using digital innovations: the application of AI, blockchain, cloud and data analytics. Ann Oper Res 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-020-03620-w

Al-Htaybat K, von Alberti-Alhtaybat L (2017) Big data and corporate reporting: impacts and paradoxes. Account Audit Accountability J 30(4):8

Andreassen RI (2020) Digital technology and changing roles: a management accountant’s dream or nightmare? J Manag Control 31(3):209–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-020-00303-2

Article Google Scholar

Arnaboldi M, Busco C, Cuganesan S (2017) Accounting, accountability, social media and big data: revolution or hype? Account Audit Accountability J 30(4):762–776. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-03-2017-2880

Arntz M, Gregory T, Zierahn U (2017) Revisiting the risk of automation. Econ Lett 159:157–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2017.07.001

Baethge-Kinsky V (2020) Digitized industrial work: requirements, opportunities, and problems of competence development. Front Sociol 5(33):1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2020.00033

Correani A, De Massis A, Frattini F, Petruzzelli AM, Natalicchio A (2020) Implementing a digital strategy: learning from the experience of three digital transformation projects. Calif Manage Rev 62(4):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125620934864

Demiröz S, Heupel T (2017) Digital transformation and its radical changes for external management accounting: a consideration of small and medium-sized enterprises. In: FDIBA conference proceedings. https://n9.cl/gt82x

Fettry S, Anindita T, Wikansari R, Sunaryo K (2019) The future of accountancy profession in the digital era. In: Global competitiveness: business transformation in the digital era, pp 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429202629-2

Frey L, Botan C, Kreps G (1999) Investigating communication: an introduction to research methods, 2nd edn. Allyn & Bacon, Boston, MA, USA

Githaiga PN (2023) Sustainability reporting, board gender diversity and earnings management: evidence from East Africa community. J Bus Socio-economic Dev. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBSED-09-2022-0099

Gulin D, Hladika M, Valenta I (2019a) Digitalization and the challenges for the accounting profession. Entren Enterp Res Innov 5:428–437

Gulin D, Hladika M, Valenta I (2019b) Digitalization and the challenges for the accounting profession. IRENET—Society for Advancing Innovation and Research in Economy, Zagreb, pp 502–511

Hunton JE (2015) The impact of digital technology on accounting behavioral research. Adv Acc Behav Res 5:3–17

Kim YJ, Kim K, Lee S (2017) The rise of technological unemployment and its implications on the future macroeconomic landscape. Futures 87:1–9

KPMG (2017) Digitalisation in accounting. Available at: https://hub.kpmg.de/digitalisierung-imrechnungswesen2017?utm_campaign=Digitalisierung%20im%20Rechnungswesen&utm_source=AEM&__hstc=214917896.3a0d5dcb67dcc1c3314090953e2c528d.1556354963109.1556354963109.1556467129734.2&__hssc=214917896.1.1556467129734&__hsfp=1828149151 . 18 April 2019

Möller K, Schäffer U, Verbeeten F (2020) Digitalization in management accounting and control: an editorial. J Manag Control 31(1–2):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-020-00300-5

Moudud-Ul-Huq S (2014) The role of artificial intelligence in the development of accounting systems: a review. UIP J Account Audit Pract 12(2):7–19

Oncioiu I, Bîlcan FR, Stoica DA, Stanciu A (2019) Digital transformation of managerial accounting-trends in the new economic environment. EIRP Proc 14(1):266–274

Oschinski M, Wyonch R (2017) Future stock? The impact of automation on Canada’s labour market. Institute C.D. Howe Institute, Commentary No. 472, available at: https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/attachments/research_papers/mixed/Update_Commentary%20472%20web.pdf . 4 June 2019

Patra G, Roy RK (2023) Business sustainability and growth in journey of industry 4.0-A case study. In: Nayyar A. Naved M, Rameshwar R (eds) New horizons for industry 4.0 in modern business. Contributions to environmental sciences & innovative business technology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20443-2_2

Phornlaphatrachakorn K, NaKalasindhu K (2021) Digital accounting, financial reporting quality and digital transformation: evidence from Thai listed firms. J Asian Financ Econ Bus 8(8):409–419

PWC (2018) Digitalisation in finance and accounting and what it means for financial statement audit. Available at: https://www.pwc.de/de/im-fokus/digitaleabschlusspruefung/pwc-digitalisation-in-finance-2018.pdf . 13 April 2019

Rom A, Rohde C (2007) Management accounting and integrated information systems: a literature review. Int J Account Inf Syst 8(1):40–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accinf.2006.12.003

Saarikko T, Westergren UH, Blomquist T (2020) Digital transformation: five recommendations for the digitally conscious firm. Bus Horiz 63(6):825–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.07.005

Sharida A, Hamdan A, Al-Hashimi M (2020) Smart cities: The next urban evolution in delivering a better quality of life. In: Hassanien A, Bhatnagar R, Khalifa N, Taha M (eds) Toward Social Internet of Things (SIoT): Enabling Technologies, Architectures and Applications. Stud Comput Intell vol 846. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24513-9_16

Shareeda A, Al-Hashimi M, Hamdan A (2021) Smart cities and electric vehicles adoption in Bahrain. J Decis Syst 30(2–3):321–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/12460125.2021.1911024

Stanciu V, Gheorghe M (2017) An exploration of the accounting profession—the stream of mobile devices. Account Manage Inf Syst 16(3):369–385

Tekbas I (2018) The profession of the digital age: accounting engineering. Available at: https://www.ifac.org/global-knowledgegateway/technology/discussion/profession-digital-age-accounting-engineering . 19 April 2019

Tekbas I, Nonwoven K (2018) The profession of the digital age: accounting engineering. In: IFAC Proceedings volumes; project: the theory of accounting, engineering; international federation of accountants. New York, NY, USA. Available online: https://www.ifac.org/knowledge-gateway/preparing-future-ready-professionals/discussion/profession-digital-ageaccounting-engineering . Accessed on 14 March 2022

Vial G (2019) Understanding digital transformation: a review and a research agenda. J Strategic Inf 28(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2019.01.003

Yao Q, Gao Y (2020) Analysis of environment accounting in the context of big data. J Phys Conf Ser 1650(3):032081. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1650/3/032081

Zhang Y, Xiong F, Xie Y, Fan X, Gu H (2020) The impact of artificial intelligence and blockchain on the accounting profession. IEEE Access 8:110461–110477

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Business and Finance, Ahlia University, Postgraduate Council (PGC), MBA Program, Manama, Kingdom of Bahrain

Latifa Jabor & Allam Hamdan

Ahlia University, College of Business and Finance, Manama, Bahrain

Allam Hamdan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Allam Hamdan .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Finance and Accounting, Lebanese American University, Byblos, Lebanon

Rim El Khoury

LaRGE Research Center, EM Strasbourg Business School, Strasbourg, France

Nohade Nasrallah

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Jabor, L., Hamdan, A. (2023). Digitalization in Accounting and Financial Reporting Quality: Literature Review. In: El Khoury, R., Nasrallah, N. (eds) Emerging Trends and Innovation in Business and Finance. Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-6101-6_59

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-6101-6_59

Published : 29 October 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-99-6100-9

Online ISBN : 978-981-99-6101-6

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- DOI: 10.46959/jeess.959063

- Corpus ID: 253211130

INTERNAL AUDIT AND FINANCIAL REPORTING QUALITY: A LITERATURE REVIEW

- İlknur Eskin

- Published in Journal of Empirical… 25 September 2021

- Business, Economics

58 Citations

The influence of auditor ethics and auditor experience on company financial reports, financial reporting quality and control system: a mixed approach assessment, determinants of the quality of financial reports, internal audit report quality and financial statement accuracy of savings and credit cooperatives societies in kenya, corporate governance factors and financial reporting timeliness: a systematic review and future research, the role of joint auditing to improving the quality of the electronic auditor's report in iraqi banks, factors that affect the quality of financial reports, international financial reporting standards adoption and financial reporting quality of listed consumer goods companies in nigeria., the mediation effect of audit quality on the relationship between auditor-client contracting features and the reliability of financial reports in yemen.

- Highly Influenced

EXECUTIVE COMPENSATION AND FINANCIAL REPORTING QUALITY OF NIGERIAN FINANCIAL SERVICE INDUSTRY

24 references, the impact of audit quality, audit committee and financial reporting quality: evidence from malaysia, audit committees and financial reporting quality in singapore, the relationship between corporate governance, internal audit and audit committee: empirical evidence from greece, audit committee effectiveness, audit quality and earnings management: an empirical study of the listed companies in egypt, rotational internal audit programs and financial reporting quality: do compensating controls help, the link between audit committees, corporate governance quality and firm performance, the association between accruals quality and the characteristics of accounting experts and mix of expertise on audit committees, the impact of audit committees personal characteristics on earnings management: evidence from china, internal audit effectiveness: multiple case study research involving chief audit executives and senior management, audit committee financial expertise, gender, and earnings management: does gender of the financial expert matter, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Creative accounting determinants and financial reporting quality: systematic literature review.

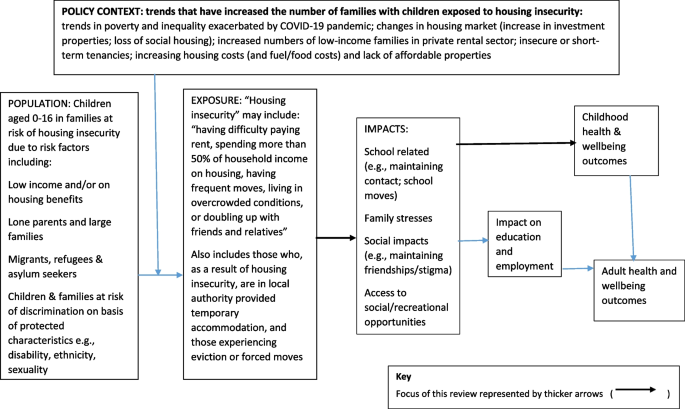

1. Introduction

- What are the main determinants of creative accounting that impact the principles and characteristics of financial reporting?

- How do those determinants impact financial reporting quality?

2. Methodology

3. creative accounting, 3.1. motivations behind creative accounting, 3.1.1. agency problems, 3.1.2. executive reward, 3.1.3. share ownership scheme, 3.1.4. income smoothing, 3.2. creative accounting techniques, 3.2.1. tangible assets, 3.2.2. goodwill, 3.2.3. depreciation, 3.2.4. inventories, 3.2.5. provisions for liabilities, 3.2.6. construction contracts, 3.3. effects of creative accounting, 3.4. determinants of creative accounting, 3.4.1. ethical issues, 3.4.2. disclosure quality, 3.4.3. internal control, 3.4.4. ownership structure, 4. financial reporting, 4.1. financial reporting quality, 4.1.1. relevance, 4.1.2. faithful representation, 4.1.3. understandability, 4.1.4. comparability, 5. discussion, 6. conclusions, author contributions, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

- Abed, Ibtihal A., Nazimah Hussin, and Mostafa A. Ali. 2020a. Piloting the Role of Corporate Governance and Creative Accounting in Financial Reporting Quality. Technology Reports of Kansai University 62: 2–7. [ Google Scholar ]

- Abed, Ibtihal A., Nazimah Hussin, Mostafa A. Ali, Nada Salman Nikkeh, and Mohammed A. Mohammed. 2020b. Creative Accounting Phenomenon in the Financial Reporting: A Systematic Review Classification, Challenges. Technology Reports of Kansai University 62: 1–10. [ Google Scholar ]

- Abed, Ibtihal A., Nazimah Hussin, Mostafa A. Ali, Rafidah Othman, and Mohammed A. Mohammed. 2020c. A Systematic Critical Review of Creative Accounting and Financial Reporting. Technology Reports of Kansai University 62: 5113–30. [ Google Scholar ]

- Abed, Ibtihal A., Nazimah Hussin, Hossam Haddad, Nidal M. Al-Ramahi, and Mostafa A. Ali. 2022a. The Moderating Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on the Relationship between Creative Accounting Determinants and Financial Reporting Quality. Sustainability 14: 1195. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Abed, Ibtihal A., Nazimah Hussin, Hossam Haddad, Tareq H. Almubaydeen, and Mostafa A. Ali. 2022b. Creative Accounting Determination and Financial Reporting Quality: The Integration of Transparency and Disclosure. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 8: 38. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Akenbor, Cletus O., and E. A. L. Ibanichuka. 2012. Creative Accounting Practices in Nigerian Banks. African Research Review 6: 23–41. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Akpanuko, Essien Ekerette, and Ntiedo John Umoren. 2018. The Influence of Creative Accounting on the Credibility of Accounting Reports. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 16: 292–310. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ali, Mostafa A., Nazimah Hussin, Hossam Haddad, Reem Al-Araj, and Ibtihal A. Abed. 2021. Intellectual Capital and Innovation Performance: Systematic Literature Review. Risks 9: 170. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Alit, Ni Nyoman. 2017. Creative Accounting Sebagai Informasi Yang Baik Atau Menyesatkan? AKRUAL: Jurnal Akuntansi 8: 103–11. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Al Momamani, Mohammed Abdullah, and MMohammed Ibrahim Obeidat. 2013. The Effect of Auditors’ Ethics on Their Detection of Creative Accounting Practices: A Field Study. International Journal of Business and Management 13: 8. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Al-Natsheh, Nancy, and Saleh Al-Okdeh. 2020. The Impact of Creative Accounting Methods on Earnings per Share. Management Science Letters 10: 831–40. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Alzeban, Abdulaziz. 2020. Influence of Internal Audit Reporting Line and Implementing Internal Audit Recommendations on Financial Reporting Quality. Meditari Accountancy Research 28: 26–50. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Alzoubi, Ebraheem Saleem Salem. 2016. Ownership Structure and Earnings Management: Evidence from Portugal. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal 24: 135–61. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Amat, Oriol, John Blake, and Jack Dowds. 1999. The Ethics of Creative Accounting. Economics Working Paper 349: 715–36. [ Google Scholar ]

- Amin, Hala M. G., and Ehab K. A. Mohamed. 2016. Auditors’ Perceptions of the Impact of Continuous Auditing on the Quality of Internet Reported Financial Information in Egypt. Managerial Auditing Journal 31: 111–32. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Anderson, Neil, Kristina Potočnik, and Jing Zhou. 2014. Innovation and Creativity in Organizations: A State-of-the-Science Review, Prospective Commentary, and Guiding Framework. Journal of Management 40: 1297–333. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Arnold, Beth, and Paul De Lange. 2004. Enron: An Examination of Agency Problems. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 15: 751–65. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Arthur, Neal, Huifa Chen, and Qingliang Tang. 2019. Corporate Ownership Concentration and Financial Reporting Quality: International Evidence. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 17: 104–32. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Atabay, Esra, and Dinç Engin. 2020. Financial Information Manipulation and Its Effects on Investor Demands: The Case of BIST Bank. In Contemporary Issues in Audit Management and Forensic Accounting . Edited by Simon Grima, Engin Boztepe and Peter J. Baldacchino. Contemporary Studies in Economic and Financial Analysis. Bradford: Emerald Publishing Limited, vol. 102, pp. 41–56. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Aureli, Selena, Daniele Giampaoli, Massimo Ciambotti, and Nick Bontis. 2019. Key Factors That Improve Knowledge-Intensive Business Processes Which Lead to Competitive Advantage. Business Process Management Journal 25: 126–43. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Baik, Bok, Sunhwa Choi, and David B. Farber. 2020. Managerial Ability and Income Smoothing. The Accounting Review 95: 1–22. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Barandak, Sajad, and Fooroozan Mohammadi. 2020. The Effect of Internal Control Weakness on the Asymmetrical Behavior of Selling, General, and Administrative Costs. Journal of Accounting and Management Vision 2: 38–53. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bean, Anne, and Helen Irvine. 2015. Derivatives Disclosure in Corporate Annual Reports: Bank Analysts’ Perceptions of Usefulness. Accounting and Business Research 45: 602–19. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Bhasin, Madan Lal. 2015. Creative Accounting Practices in the Indian Corporate Sector: An Empirical Study. International Journal of Management Sciences and Business Research 4: 35–52. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bimo, Irenius Dwinanto, Sylvia Veronica Siregar, Ancella Anitawati Hermawan, and Ratna Wardhani. 2019. Internal Control over Financial Reporting, Organizational Complexity, and Financial Reporting Quality. International Journal of Economics and Management 13: 331–42. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bini, Laura, Francesco Dainelli, and Francesco Giunta. 2015. Business Model Disclosure in the Strategic Report. Journal of Intellectual Capital 17: 83–102. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Brass Island. 2011. Ethical Compliance by the Accountant on the Quality of Financial Reporting and Performance of Quoted Companies in Nigeria. Asian Journal of Business Management 3: 152–60. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brauweiler, Hans-Christian, Aida Yerimpasheva, Zerma Bagalbayeva, Mahmoud Lari Dashtbayaz, Mahdi Salehi, Toktam Safdel, and Ben Kwame Agyei-Mensah. 2019. Avoiding Creative Accounting: Corporate Governance and Leadership Skills. Zeszyty Teoretyczne Rachunkowości 12: 9–19. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Briloff, Abraham J. 1972. Unaccountable Accounting . New York: Harpercollins. [ Google Scholar ]

- Buallay, Amina. 2018. Audit Committee Characteristics: An Empirical Investigation of the Contribution to Intellectual Capital Efficiency. Measuring Business Excellence 22: 183–200. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Butala, Amy, and Zafar U. Khan. 2011. Accounting Fraud at Xerox Corporation. SSRN Electronic Journal 16: 81–89. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Campello, Murillo, Erasmo Giambona, John R. Graham, and Campbell R. Harvey. 2011. Liquidity Management and Corporate Investment during a Financial Crisis. The Review of Financial Studies 24: 1944–79. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Cardoso, Ricardo Lopes, and Bernardo Guelber Fajardo. 2018. Public Sector Creative Accounting: A Literature Review. SSRN Electronic Journal 3: 1–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Carlin, Tyrone M., and Nigel Finch. 2011. Goodwill Impairment Testing under IFRS: A False Impossible Shore? Pacific Accounting Review 23: 368–92. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cavero Rubio, José Antonio, Araceli Amorós Martínez, and Antonio Collazo Mazón. 2020. Economic Effects of Goodwill Accounting Practices: Systematic Amortisation versus Impairment Test. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting/Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad 12: 224–45. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cernusca, Lucian, Delia David, Cristina Nicolaescu, and Bogdan Cosmin Gomoi. 2016. Empirical Study on the Creative Accounting Phenomenon. Studia Universitatis Vasile Goldis Arad Economics Series 26: 63–87. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Chang, Weng Foong, Azlan Amran, Mohammad Iranmanesh, and Behzad Foroughi. 2019. Drivers of Sustainability Reporting Quality: Financial Institution Perspective. International Journal of Ethics and Systems 35: 632–50. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cheung, Esther, Elaine Evans, and Sue Wright. 2010. An Historical Review of Quality in Financial Reporting in Australia. Pacific Accounting Review 22: 147–69. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cohen, Sandra, and Sotirios Karatzimas. 2017. Accounting Information Quality and Decision-Usefulness of Governmental Financial Reporting: Moving from Cash to Modified Cash. Meditari Accountancy Research 25: 95–113. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cuozzo, Benedetta, John Dumay, Matteo Palmaccio, and Rosa Lombardi. 2017. Intellectual Capital Disclosure: A Structured Literature Review. Journal of Intellectual Capital 18: 9–28. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dabbicco, Giovanna. 2015. The Impact of Accrual-Based Public Accounting Harmonization on EU Macroeconomic Surveillance and Governments’ Policy Decision-Making. International Journal of Public Administration 38: 253–67. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- De Jesus, Tania Alves, Pedro Pinheiro, Catarina Kaizeler, and Manuela Sarmento. 2020. Creative Accounting or Fraud? Ethical Perceptions Among Accountants. International Review of Management and Business Research 9: 58–78. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- De Luca, Francesco, Andrea Cardoni, Ho-Tan-Phat Phan, and Evgeniia Kiseleva. 2020. Does Structural Capital Affect SDGs Risk-Related Disclosure Quality? An Empirical Investigation of Italian Large Listed Companies. Sustainability 12: 1776. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Demerens, Frédéric, Jean-Louis Paré, and Jean Redis. 2013. Investor Skepticism and Creative Accounting: The Case of a French Sme Listed on Alternext. International Journal of Business 18: 59. [ Google Scholar ]

- Diana, Balaciu, and Vladu Alina Beattrice. 2010. Creative Accounting–Players and Their Gains and Loses. Annals of Faculty of Economics 1: 813–19. [ Google Scholar ]

- Doan, Anh-Tuan, Kun-Li Lin, and Shuh-Chyi Doong. 2020. State-Controlled Banks and Income Smoothing. Do Politics Matter? The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 51: 101057. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Eiler, Lisa A., Jose Miranda-Lopez, and Isho Tama-Sweet. 2015. The Impact of Accounting Disclosures and the Regulatory Environment on the Information Content of Earnings Announcements. International Journal of Accounting 50: 142–69. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Elmashharawi, Zaher Hosni, and Khaled Sabour. 2020. The Impact of Programmed Accounting Analysis (PAA) for the Financial Statements on Qualitative Characteristics of Useful Financial Information. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3610846 (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Elsiddig Ahmed, Ibrahim. 2020. The Qualitative Characteristics of Accounting Information, Earnings Quality, and Islamic Banking Performance: Evidence from the Gulf Banking Sector. International Journal of Financial Studies 8: 30. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Engelseth, Per, and Duangpun Kritchanchai. 2018. Innovation in Healthcare Services—Creating a Combined Contingency Theory and Ecosystems Approach. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 337: 012022. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Feiler, Paul, and David Teece. 2014. Case Study, Dynamic Capabilities and Upstream Strategy: Supermajor EXP. Energy Strategy Reviews 3: 14–20. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Foster, Benjamin P., Guy Mcclain, and Trimbak Shastri. 2013. The Auditor’s Report on Internal Control & Fraud Detection Responsibility: A Comparison of French and U.S. Users’ Perceptions. Journal of Accounting, Ethics, & Public Policy 14: 221–57. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fraij, Jihad, Hossam Haddad, and Nemer Abu Romman. 2021. The Quality of Accounting Information System, Firm Size, Sector Type as a Case Study from Jordan. International Business Management 15: 30–38. Available online: https://medwelljournals.com/abstract/?doi=ibm.2021.30.38 (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- Ghorbani, Behrooz, Mehrdad Ghanbari, Babak Jamshidi Navid, and Ali Reza Moradi. 2020. Big Bath and Insolvency. Empirical Research in Accounting 10: 159–78. [ Google Scholar ]

- Giacosa, Elisa, Alberto Ferraris, and Stefano Bresciani. 2017. Exploring Voluntary External Disclosure of Intellectual Capital in Listed Companies: An Integrated Intellectual Capital Disclosure Conceptual Model. Journal of Intellectual Capital 18: 149–69. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Goel, Sandeep. 2014. The Quality of Reported Numbers by the Management: A Case Testing of Earnings Management of Corporate India. Journal of Financial Crime 21: 355–76. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gupta, Chander Mohan, and Divesh Kumar. 2020. Creative Accounting a Tool for Financial Crime: A Review of the Techniques and Its Effects. Journal of Financial Crime 27: 397–411. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Habib, Ahsan, Md Borhan Uddin Bhuiyan, and Mostafa Monzur Hasan. 2019. IFRS Adoption, Financial Reporting Quality and Cost of Capital: A Life Cycle Perspective. Pacific Accounting Review 31: 497–522. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Haddad, Hossam. 2016. Internal Controls in Jordanian Banks and Compliance Risk. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting 7: 17–31. [ Google Scholar ]

- Haddad, Hossam, Dina Alkhodari, Reem Al-Araj, Nemer Aburumman, and Jihad Fraij. 2017. Review of the Corporate Governance and Its Effects on the Disruptive Technology Environment. WSEAS Transactions on Environment and Development 17: 1004–20. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hadiyanto, Andrain, Evita Puspitasari, and Erlane K. Ghani. 2018. The Effect of Accounting Methods on Financial Reporting Quality. International Journal of Law and Management 60: 1401–11. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hammarbäck, Matilda, and Linda Karlsson. 2020. Big Bath: Goodwillnedskrivning Och Samband Med VD-Byte: En Kvantitativ Jämförande Studie Av Noterade Och Onoterade Företag Som Tillämpar IFRS. June 8. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1437133/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Hentati-Klila, Ikhlas, Saida Dammak-Barkallah, and Habib Affes. 2017. Do Auditors’ Perceptions Actually Help Fight against Fraudulent Practices? Evidence from Tunisia. Journal of Management and Governance 21: 715–35. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Holderness, Mike. 2015. A Creative Accounting. New Scientist 225: 46–47. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Iatridis, George, and Panayotis Alexakis. 2012. Evidence of Voluntary Accounting Disclosures in the Athens Stock Market. Review of Accounting and Finance 11: 73–92. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Idris, Adekunle Abiodun, James Sunday Kehinde, Sunday Stephen A. Ajemunigbohun, and Justin M. O. Gabriel. 2012. The Nature, Techniques and Prevention of Creative Accounting: Empirical Evidence from Nigeria. Canadian Journal of Accounting and Finance 1: 26–31. [ Google Scholar ]

- Iqbal, Muhammad, Faisal Javed, Rahmawati Edy Suprianto, Suwarno Suwarno, Henny Murtini, Dyah Sawitri Rahmawati, Hope Osayantin Aifuwa, Keme Embele, and Saidu Musa. 2015. Audit Committee Accounting Expert and Earnings Management with ‘Status’ Audit Committee as Moderating Variable. Indonesian Journal of Sustainability Accounting and Management 4: 89–105. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Jedi, Farhan Firas, and Sabri Nayan. 2018. The Effect of Oil Price Volatility, Board of Directors Characteristics on Firm Performance of Iraq Listed Companies: A Conceptual Framework. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 8: 342–50. [ Google Scholar ]

- Julian, Higgins, and Thomas James. 2009. CCHB Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- Kalbers, Lawrence P. 2009. Fraudulent Financial Reporting, Corporate Governance and Ethics: 1987–2007. Review of Accounting and Finance 8: 187–209. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kamau, Charles Guandaru, Agnes Ndinda Mutiso, and Dorothy Mbithe Ngui. 2012. Tax Avoidance and Evasion as a Factor Influencing ’Creative Accounting Practice’ among Companies in Kenya. Journal of Business Studies Quarterly 4: 77. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kardan, Behzad, Mahdi Salehi, and Rahimeh Abdollahi. 2016. The Relationship between the Outside Financing and the Quality of Financial Reporting: Evidence from Iran. Journal of Asia Business Studies 10: 20–40. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Keune, Marsha B., and Timothy M. Keune. 2018. Do Managers Make Voluntary Accounting Changes in Response to a Material Weakness in Internal Control? Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 37: 107–37. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kewo, Cecilia Lelly. 2017. The Influence of Internal Control Implementation and Managerial Performance on Financial Accountability Local Government in Indonesiaf. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 7. [ Google Scholar ]

- Korutaro Nkundabanyanga, Stephen, Venancio Tauringana, Waswa Balunywa, and Stephen Naigo Emitu. 2013. The Association between Accounting Standards, Legal Framework and the Quality of Financial Reporting by a Government Ministry in Uganda. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 3: 65–81. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kotlarz, Aaron R. 2018. Productivity in Navy Construction Contracts. Available online: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/mcrp/340 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Kovalová, Erika, and Katarína Frajtová Michalíková. 2020. The Creative Accounting in Determining the Bankruptcy of Business Corporation. SHS Web of Conferences 74: 1017. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Krishnan, Jagan, Jayanthi Krishnan, and Sophie Liang. 2020. Internal Control and Financial Reporting Quality of Small Firms: A Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Regimes. Review of Accounting and Finance 19: 221–46. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kruglyak, Zinaida Ivanovna, and Olga Ivanovna Shvyreva. 2018. Improving the Russian Regulatory Basis for International Financial Reporting Standards-Based Qualitative Characteristics of Financial Information. Journal of Applied Economic Sciences 12: 2325–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lari Dashtbayaz, Mahmoud, Mahdi Salehi, and Toktam Safdel. 2019. The Effect of Internal Controls on Financial Reporting Quality in Iranian Family Firms. Journal of Family Business Management 9: 254–70. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lazo, Bernardo, and Mark Billings. 2012. Accounting Regulation and Management Discretion-A Case Note. Abacus 48: 414–37. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Li, Yan, Xuepeng Qian, Liguo Zhang, and Liang Dong. 2017. Exploring Spatial Explicit Greenhouse Gas Inventories: Location-Based Accounting Approach and Implications in Japan. Journal of Cleaner Production 167: 702–12. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lim, Si Jie, Gregory White, Alina Lee, and Yuni Yuningsih. 2017. A Longitudinal Study of Voluntary Disclosure Quality in the Annual Reports of Innovative Firms. Accounting Research Journal 30: 89–106. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Linsmeier, Thomas J., and Erika Wheeler. 2021. The Debate over Subsequent Accounting for Goodwill Subsequent Accounting for Goodwill. Accounting Horizons 35: 107–28. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lucchese, Manuela, and Ferdinando Di Carlo. 2020. Inventories Accounting under US-GAAP and IFRS Standards: The Differences That Hinder the Full Convergence. International Journal of Business and Management 15: 7. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Maama, H., J. O. Akande, and M. Doorasamy. 2020. NGOs’ Engagements and Ghana’s Environmental Accounting Disclosure Quality. In Environmentalism and NGO Accountability . Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, vol. 9, pp. 83–106. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Makhaiel, Nargis Kaisar Boles, and Michael Leslie Joseph Sherer. 2018. The Effect of Political-Economic Reform on the Quality of Financial Reporting in Egypt. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 16: 245–70. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Malik, Ali, Jonathan Liu, and Orthodoxia Kyriacou. 2011. Creative Accounting Practice and Business Performance: Evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Business Performance Management 12: 228. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mamo, Jonada. 2014. Accounting Errors and the Risk of Intentional Errors That Hide Accounting Information. The Importance and the Implementation of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in Albania. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5: 494–99. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Manes-Rossi, Francesca, Giuseppe Nicolò, and Daniela Argento. 2020. Non-Financial Reporting Formats in Public Sector Organizations: A Structured Literature Review. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management 32: 639–69. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martin, Rafael, Winwin Yadiati, Arie Pratama, María Rubio-Misas, Ibrahem Alshbili, Ahmed A. Elamer, and Eshani Beddewela. 2019. Doing Good with Creative Accounting? Linking Corporate Social Responsibility to Earnings Management in Market Economy, Country and Business Sector Contexts. Sustainability 8: 4568. [ Google Scholar ]

- Massaro, Maurizio, John Dumay, and James Guthrie. 2016. On the Shoulders of Giants: Undertaking a Structured Literature Review in Accounting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 29: 767–801. [ Google Scholar ]

- Matica (Balaciu), Diana, Victoria Bogdan, Liliana Feleaga, and Adela-Laura Popa. 2014. ‘Colorful’ Approach Regarding Creative Accounting. An Introspective Study Based On the Association Technique. Journal of Accounting and Management Information Systems 13: 643–64. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mousavi Shiri, Mahmoud, Mahdi Salehi, Fatemeh Abbasi, and Shayan Farhangdoust. 2018. Family Ownership and Financial Reporting Quality: Iranian Evidence. Journal of Family Business Management 8: 339–56. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mudel, Sonia. 2015. Creative Accounting and Corporate Governance: A Literature Review. SSRN Electronic Journal 3: 12–34. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mulford, Charles W., and Eugene E. Comiskey. 2012. Creative Accounting and Accounting Scandals in the USA. Creative Accounting, Fraud and International Accounting Scandals , 407–24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Muraina, Saheed Adekunle, and Kabiru Isa Dandago. 2020. Effects of Implementation of International Public Sector Accounting Standards on Nigeria’s Financial Reporting Quality. International Journal of Public Sector Management 33: 323–38. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Nagata, Kyoko, and Pascal Nguyen. 2017. Ownership Structure and Disclosure Quality: Evidence from Management Forecasts Revisions in Japan. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 36: 451–67. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Nobanee, Haitham, and Nejla Ellili. 2017. Does Operational Risk Disclosure Quality Increase Operating Cash Flows? BAR-Brazilian Administration Review 4: 14–24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Palazzi, Federica, Francesca Sgrò, Massimo Ciambotti, and Nick Bontis. 2020. Technological Intensity as a Moderating Variable for the Intellectual Capital–Performance Relationship. Knowledge and Process Management 27: 3–14. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Paolone, Francesco, and Cosimo Magazzino. 2014. Earnings Manipulation among the Main Industrial Sectors. Evidence from Italy. Evidence from Italy 5: 253–61. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pedro, Eugénia, João Leitão, and Helena Alves. 2018. Back to the Future of Intellectual Capital Research: A Systematic Literature Review. Management Decision 56: 2502–83. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Qian, Wei, Jacob Hörisch, Stefan Schaltegger, Fatma Baalouch, Salma Damak Ayadi, Khaled Hussainey, and Ben Kwame Agyei-Mensah. 2015. A Study of the Determinants of Environmental Disclosure Quality: Evidence from French Listed Companies. Journal of Cleaner Production 22: 1608–19. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ramadan, Ismail Zeyad. 2017. Creative Accounting: Theoretical Framework for Dealing with Its Determinants and Institutional Investors’ Involvement . Wales: Cardiff Metropolitan University. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rashid, Md Mamunur. 2020a. Financial Reporting Quality and Share Price Movement-Evidence from Listed Companies in Bangladesh. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 18: 425–58. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rashid, Md Mamunur. 2020b. Presence of Professional Accountant in the Top Management Team and Financial Reporting Quality: Evidence from Bangladesh. Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change 16: 237–57. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Remenarić, Branka, Ivana Kenfelja, and Ivo Mijoč. 2018. Creative Accounting-Motives, Techniques and Possibilities of Prevention. Ekonomski Vjesnik 31: 193–99. [ Google Scholar ]

- Repousis, Spyridon. 2016. Using Beneish Model to Detect Corporate Financial Statement Fraud in Greece. Journal of Financial Crime 23: 1063–73. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Richman, Vincent, and Alex Richman. 2012. A Tale of Two Perspectives: Regulation Versus Self-Regulation. A Financial Reporting Approach (from Sarbanes-Oxley) for Research Ethics. Science and Engineering Ethics 18: 241–46. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Rose, Jacob M., Cheri R. Mazza, Carolyn S. Norman, Anna M. Rose, Abdelmohsen M. Desoky, Gehan A. Mousa, and Sasho Arsov. 2017. Transparency and Disclosure, Neutrality and Balance: Shared Values or Just Shared Words? Problems and Perspectives in Management 8: 63–87. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Roszkowska-Menkes, Maria Teresa. 2018. Integrating Strategic CSR and Open Innovation. Towards a Conceptual Framework. Social Responsibility Journal 14: 950–66. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rozidi, Muhammad Syafiq Razelin Anis, Nor Aime Mohd Nor, Nuraini Abdul Aziz, Nur Amalina Rosli, and Norlaila Mazura Hj Mohaiyadin. 2015. Relationship between Auditors’ Ethical Judgments, Quality of Financial Reporting and Auditors’ Attitude towards Creative Accounting: Malaysia Empirical Evidence. International Journal of Business, Humanities and Technology 5: 81–87. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sahasranamam, Sreevas, Bindu Arya, and Mukesh Sud. 2020. Ownership Structure and Corporate Social Responsibility in an Emerging Market. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 37: 1165–92. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Saleem, Khalil Suleiman Abu. 2019. The Impact of Audit Committee Characteristics on the Creative Accounting Practices Reduction in Jordanian Commercial Banks. Modern Applied Science 13: 113–23. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Saleem, Khalil Suleiman Abu, Mahdi Salehi, Mohammadamin Shirazi, Habiba Al-Shaer, Aly Salama, Steven Toms, and Najib Sahyoun. 2020. Audit Committees and Financial Reporting Quality: Evidence from UK Environmental Accounting Disclosures. Managerial Auditing Journal 35: 1639–62. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Salehi, Mahdi, Nasrin Ziba, and Ali Daemi Gah. 2018. The Relationship between Cost Stickiness and Financial Reporting Quality in Tehran Stock Exchange. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 67: 1550–65. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sanusi, Beshiru, and Prince Famous Izedonmi. 2014. Nigerian Commercial Banks and Creative Accounting Practices. Journal of Mathematical Finance 4: 43031. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Shah, Syed Zulfiqar Ali, Safdar Butt, and Yasir Bin Tariq. 2011. Use or Abuse of Creative Accounting Techniques. International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance 2: 531–36. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Shahzad, Faisal, Ijaz Ur Rehman, Sisira Colombage, and Faisal Nawaz. 2019. Financial Reporting Quality, Family Ownership, and Investment Efficiency: An Empirical Investigation. Managerial Finance 45: 513–35. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Shehadeh, Maha, Esraa Esam Alharasis, Hossam Haddad, and Elina F. Hasan. 2022. The Impact of Ownership Structure and Corporate Governance on Capital Structure of Jordanian Industrial Companies. Wseas Transactions on Business and Economics 19: 361–75. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Škoda, Miroslav, Tomáš Lengyelfalusy, and Gabriela Gabrhelová. 2017. Creative Accounting Practicies in Slovakia after Passing Financial Crisis. Copernican Journal of Finance & Accounting 6: 71–86. [ Google Scholar ]

- Suer, Ayca Zeynep. 2014. The Recognition of Provisions: Evidence from BIST100 Non-Financial Companies. Procedia Economics and Finance 9: 391–401. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Susmus, Türker, and Dilek Demirhan. 2013. Creative Accounting: A Brief History and Conceptual Framework. Paper presented at the 3rd Balkans and Middle East Countries Conference on Accounting and Accounting History, Istanbul, Turkey, June 19–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- Szymański, Paweł. 2017. Risk Management in Construction Projects. Procedia Engineering 208: 174–82. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tassadaq, Fizza, and Qaisar Ali Malik. 2015. Creative Accounting and Financial Reporting: Model Development and Empirical Testing. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 5: 544–51. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tri Wahyuni, Ersa, Gina Puspitasari, and Evita Puspitasari. 2020. Has IFRS Improved Accounting Quality in Indonesia? A Systematic Literature Review of 2010–2016. Journal of Accounting and Investment 21: 19–44. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Trisanti, Theresia. 2016. Did the Corporate Governance Reform Have Effect on Creative Accounting Practices in Emerging Economies? The Case of Indonesian Listed Companies. Journal Global Business Advancement 9: 52. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tunji, Siyanbola Trimisiu, Rebecca Deborah Benjamin, Amuda Motunronke Bintu, and Lloyd Janet Flomo. 2020. Creative Accounting and Investment Decision in Listed Manufacturing Firms in Nigeria. Journal of Accounting and Taxation 12: 39–47. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vladu, Alina Beattrice, Oriol Amat, and Dan Dacian Cuzdriorean. 2017. Truthfulness in Accounting: How to Discriminate Accounting Manipulators from Non-Manipulators. Journal of Business Ethics 140: 633–48. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Wood, Anthony, and Keisha Small. 2019. An Assessment of Corporate Governance in Financial Institutions in Barbados. Journal of Governance and Regulation 8: 47–58. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yao, Shouyu, Zhuoqun Wang, Mengyue Sun, Jing Liao, and Feiyang Cheng. 2020. Top Executives’ Early-life Experience and Financial Disclosure Quality: Impact from the Great Chinese Famine. Accounting & Finance 60: 4757–93. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yaseen, Ali. Taha, Ahmed Kadhim Idam, and Mohammed Jabbar Fashakh. 2018. Creative Accounting Standards and Its Techniques. Opcion 34: 1611–42. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yasser, Qaiser Rafique, Abdullah Al Mamun, and Irfan Ahmed. 2016. Quality of Financial Reporting in the Asia-Pacific Region: The Influence of Ownership Composition. Review of International Business and Strategy 26: 543–60. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yasser, Qaiser Rafique, Abdullah Al Mamun, and Margurite Hook. 2017. The Impact of Ownership Structure on Financial Reporting Quality in the East. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 25: 178–97. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yekini, Kemi, and Kumba Jallow. 2012. Corporate Community Involvement Disclosures in Annual Report: A Measure of Corporate Community Development or a Signal of CSR Observance? Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 3: 7–32. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zheng, Xiaosong, and Jiao Chen. 2017. Financial Reporting Quality in China: A Perspective of Qualitative Characteristics. Transformations in Business & Economics 16: 148–63. [ Google Scholar ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| No. | Criteria | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Title | Identification as a new research, meta-analysis, or both. |

| 2 | Topic | Literature directly related to the present study concepts. |

| 3 | Period | Peer-reviewed articles published during 2015–2020. |

| 4 | Research | Only empirical studies (quantitative and qualitative analyses) were included. |

| 5 | Transparency | Research methods from past studies must be explicit in terms of sample sizes, instruments, and analyses. |

| 6 | Reliability and Validity | Literature must have valid and reliable outcomes consistent with the study types and publication indexes. |

| 7 | Databases | Studies must focus on Scopus, Science Direct, Emerald, and Web of Science databases. |

| MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

Share and Cite

Abed, I.A.; Hussin, N.; Ali, M.A.; Haddad, H.; Shehadeh, M.; Hasan, E.F. Creative Accounting Determinants and Financial Reporting Quality: Systematic Literature Review. Risks 2022 , 10 , 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks10040076

Abed IA, Hussin N, Ali MA, Haddad H, Shehadeh M, Hasan EF. Creative Accounting Determinants and Financial Reporting Quality: Systematic Literature Review. Risks . 2022; 10(4):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks10040076

Abed, Ibtihal A., Nazimah Hussin, Mostafa A. Ali, Hossam Haddad, Maha Shehadeh, and Elina F. Hasan. 2022. "Creative Accounting Determinants and Financial Reporting Quality: Systematic Literature Review" Risks 10, no. 4: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks10040076

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Financial Reporting Practices and Investment Decisions: A Review of the Literature

Industrial Engineering & Management

Related Papers

SSRN Electronic Journal

Wm. Dennis Huber

The purpose of this paper is to present an analysis and critique of Roychowdhury, Shroff, and Verdi’s The effects of financial reporting and disclosure on corporate investment: A review (Journal of Accounting & Economics, 68 (2019)). Roychowdhury, Shroff, and Verdi survey the empirical literature over the previous two decades on “whether and to what extent financial reporting facilitates the allocation of capital to the right investment projects,” “provide a framework to organize this literature,” and “highlight opportunities for future research.” The framework they provide for organizing the literature “articulate[s] two broad scenarios in which financial reporting ‘matters’ for investment choices: (i) the presence of information asymmetry that gives rise to agency frictions such as adverse selection and moral hazard costs, and (ii) the presence of uncertainty about growth opportunities.” The analysis and critique presented herein addresses the framework and the first scenario. In particular, it focuses on what they refer to as agency frictions and the opportunities they suggest for future research. While the question of whether and to what extent financial reporting facilitates the allocation of capital to the right investment projects is important and worthy of future research, the framework and first scenario present several problems that cannot easily be ignored if the opportunities for future research are to be pursued.

Kania Nurcholisah

Financial reporting is the primary means of communicating financial information to external parties, which are used as a basis for decision making. Financial statement information will have a utility value if obtained from quality financial reporting. Understanding the quality of financial reporting can be viewed in two perspectives. The first view states that the quality of financial reporting related to the company's overall performance is illustrated in corporate profits. Associated with the quality of which measures are focused on attributes that are believed to affect FRQ such as earnings management, financial restatements, and timeliness. The second view states that the quality of financial reporting related to the performance of the company's shares in the capital market. Which is getting stronger relationship between income in exchange markets shows that financial reporting information is getting higher. With the quality of financial reporting it can protect investor...

International Transaction Journal of Engineering, Management, & Applied Sciences & Technologies

Mahfod Aldoseri

The purpose of this study is to verify the impact of international financial reporting standards (IFRS) adoption on the quality of accounting performance and efficiency of investment decisions in the Saudi business environment as an emerging economy. In this study, content analysis approach is adopted for examining the annual reports of Saudi companies listed in Saudi stock exchange market during two periods: the pre-adoption of IFRS period during the year of 2016 and the post-adoption of IFRS period during the period 2017-2018. The study uses accounting information, accounting conservatism, earning management as alternative variables of accounting performance quality. In addition to accounting profit quality, liquidity and cost of capital are also used as alternative variables for the efficiency of investment decisions. The study finds that there was a positive impact of IFRS adoption on the quality of accounting performance, since it was positively related to both the qualitative ...

Journal of Accounting and Economics

Tatiana Minniyakhmetova

International Journal of Nonlinear Analysis and Applications

Alim Al Ayub Ahmed

Objective –This study intends to examine the relationship between investment efficiency and financial information excellence. The study is also examining the moderating impact of sustainability on the relation between excellence in financial information and investment productivity. Methodology –The cumulative measurements are 668 firm-years and are made up of 257 subsamples of underinvestment and 411 sub-samples of overinvestment. This study may find no proof on the moderating effect of diversification on the relation between excellence in financial information and efficiency in investment. In the years 2016 to 2019, our samples are companies listed on the Dhaka Stock Exchange. Findings – The results indicate that financial information reporting quality (both for overinvestment and underinvestment sub-samples) has a positive association with investment performance. Although the evidence is not consistent across sub-samples, the test findings on the relationship between diversificati...

WAFFEN-UND KOSTUMKUNDE JOURNAL

D. Muhammad T U R K I Alshurideh

Various literature review were carry out in order to assess the relation between Financial Reporting Quality and Investment. Nevertheless the relation between them requires more investigation from different perspective in order to extend our knowledge theoretically on what's been done and where the researches reached. this study present a systematic review on the relation between financial reporting quality and investment aiming to provide a comprehensive review of all articles addressed this topic till 2019. the main finding resulted of 28 articles and a model was built from the relation of different types of variables followed from the studies in order to extend our models. the main problem was with the frequency resulted from analyzing targeted relation. Moreover. Most of the studies was collected based on secondary data from the stock market and analyzed mainly by using the regression models, in additional to few surveys and qusi-experiments questionnaire and one interview. further , most of the articles were undertaken in Indonesia and Iran , followed by China then USA respectively among different countries. alongside by most of the studies which was analyzed were conducted in the context of corporation which is publicity listed in the stock market. Followed by private firms .our finding of this systematic review will enlighten the research targeting the relation between financial reporting quality and investment and would be helpful to spotlight future research guide and open opportunities for cross-disciplinary research .

Mehdi Zeynali

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

The Winners

Bernadeta Susilo Martanti

Uluslararası Avrasya Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi

selim cengiz

Journal of Accounting Auditing and Business

Fury Khristianty Fitriyah

International Journal of Accounting & Information Management

Mushahid Hussain Baig

Investment Strategies in Emerging New Trends in Finance

Nouha Khoufi

Conference series-Federal Reserve Bank of Boston

Azizah Hassan

International Journal of ADVANCED AND APPLIED SCIENCES

khaled oweis

Indonesian Journal of Sustainability Accounting and Management

Jalila Johari

Universal Journal of Accounting and Finance

Jerry D kwarbai

The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business

Yuyun Yuningsih

Journal of Risk and Financial Management

Lamija Rizvić

ASIAN JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND ACCOUNTING (AJBA)

Nigerian Chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review

mehrdad goudarzvand chegini

Ana-Maria Zaiceanu

Talieh Shaikhzadeh Vahdat Ferreira

Review of Business Management

Aquiles Kalatzis

wafaa salah

Financial Management

James Conover

Contemporary Accounting Research

Anne Beatty

Economic Policy Review

Ghith Jibrail

Organizacija

Mahdi Salehi

Wael Alrashed

Journal of Applied Accounting Research

Khaled Hussainey

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Valuation of financial reporting quality: is it an issue in the firm’s valuation?

Asian Journal of Accounting Research

ISSN : 2459-9700

Article publication date: 30 June 2023

Issue publication date: 7 November 2023

- Supplementary Material

The purpose of this study is to test the determinant of financial report quality and its consequences to the company values.

Design/methodology/approach

This research is using a quantitative approach and testing a theory by formulating some hypotheses. The sample of this study is 85 go public companies listed in the Indonesia Stock Exchange, for a 5-year observation period from 2016 to 2020. Hence, it has a total of 425 observations. Data were analyzed using path analysis.

The results found that innate factors from financial reporting quality (FRQ) consists of dynamic factors (operation cycle and sales volatility) as well as static factors (firm’s size, FS). These factors help to achieve FRQ and are able to provide a positive response to the market. On the other hand, static factors (firm’s age, FA) and institution risk factors (leverage) are not able to produce FRQ. Thus, it cannot be considered as an economic decision maker for an investor.

Practical implications

Research implications include theoretical and practical implications. Theoretical implications prove that the valuation of clean surplus theory, which shows the market value of the company, is reflected in the components of the financial statements. This study also uses more than one quality of financial reporting. The practical implication of the research is that the research results are expected to provide information for the company’s management, to fulfill quality financial reporting and so that the market or investors will respond positively to these conditions. In addition, quality financial reporting information provides benefits for investors and capital market analysts (consisting of investors, brokers and market securities analysts) in determining investment decisions. The Financial Services Authority is also able to improve the implementation of corporate governance practices in Indonesia, through reform of the framework supervision of the financial services sector.

Originality/value

This research examines the determinants of FRQ and its consequences on firm’s value (FV). Innate factors proxies from FRQ include dynamic factors (operation cycle and sales volatility), static factors (FS and FA) and institution risk factors (leverage). A follow-up study on the value of the company because it shows the magnitude of the market response (financial statement users) on the quality of financial reporting, which is reflected in FV, the originality of this research is that the object of research is carried out in developing countries, specifically in Indonesia, because most of the previous research was carried out in developed countries.

- Dynamic factors

- Static factor

- Institution risk factor

- Financial reporting quality

Asyik, N.F. , Agustia, D. and Muchlis, M. (2023), "Valuation of financial reporting quality: is it an issue in the firm’s valuation?", Asian Journal of Accounting Research , Vol. 8 No. 4, pp. 387-399. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJAR-08-2022-0251

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2023, Nur Fadjrih Asyik, Dian Agustia and Muchlis Muchlis

Published in Asian Journal of Accounting Research . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

The general overview on the financial report quality had been studied by many researchers. Therefore, an agreement had been created to support the convergence of accounting standard harmonization that will be impacted within the financial reporting. Some phenomena occurred in an accounting scandal in the early 21st century, which showed us the weakness in the financial reporting quality (FRQ). The financial report quality depends on the value on the accounting report; hence, it is important for a company to provide a high-quality financial report. Research shows that a quality financial report will be both impactful and useful in making an investment decision. The concept of a quality financial report is not only for containing financial information but also non-financial, which will be useful in making an economic decision ( Herath et al ., 2017 ; Asyik et al ., 2022 ).

The quality of financial reports will be studied from two distinct aspects. First, the quality of a financial report shows the company’s performance, which reflected on the profit information. It can be said that financial report information has a high quality if the profit obtained in the current year can be used as an indicator to generate profit in the future ( Dang et al ., 2020 ) or as cash revenue in the future ( Noury et al ., 2020 ). Second, the quality of financial reporting is related to the company’s market performance, which is listed in the stock exchange. The strong relationship between profit and a stock’s market price proved that financial reporting information will be responded to positively by either the market or investors ( Dang et al ., 2020 ).

The purpose of financial reporting is to provide financial statement users with financial information that is useful for making economic decisions ( Kaawaase et al ., 2021 ). A valid decision can be made if the information in the financial statements meets the quality of financial information, including being presented in an appropriate, relevant, comparable, understandable, timely and verifiable manner. In addition, the quality of financial reporting is also useful in making decisions regarding the allocation of resources owned by the company. Fulfillment of the quality of financial reporting will be able to inform the company’s ability to manage both internal and external sources of funds, and meet the right elements of accountability ( Lin et al ., 2016 ).

Studies related to the quality of the financial reporting can be done by using two different approaches. The first approach is to evaluate the causes of the financial report quality. This approach is to examine the company’s internal causes or characteristics. Those are dynamic innate (operational cycle and sales volatility), static (company’s size and its age) and institution risk factor (leverage). The second approach is the external market’s response to determine the majority of which is using the financial reporting. This response will be determined by the value of the company ( Al-Dmour and Al-Dmour, 2018 ). Lonkani (2018) stated that the company’s value is not merely related to the external stakeholders’ relationship or the users of financial reporting such as investors and creditors, however, it is also considering an implicit relationship to be evaluated in the valuation process. Besides that, the meaning of the company’s valuation is not solely for one group of people (in this case investors), who will obtain the maximum level of gain from company’s operational activities.

This study is to examine the determinant of the quality of financial reporting and its consequences to the company’s valuation. The proxy of innate factors involves dynamic factors (operational cycle and sales volatility), static factors (firm’s size, FS and its age) and, lastly, institutional risk factors (leverage). This study contributes both theoretically and practically. Theoretically, this research shows that valuation of clean surplus theory which determines the firm’s market value reflected in the financial report component ( Asyik et al ., 2023 ). This study has employed more than one FRQ. Practically, the findings of this study will provide information to management in order to produce a quality financial report, which will then be responded to positively by the market and investors. Furthermore, a quality financial report will benefit investors and stock market’s analysts (investors, brokers and market security analyst) in making an investment decision.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1 theoretical foundation, 2.1.1 quality of financial report.

According to ( IASB, 2018 ), the information quality revealed in the firm’s financial report can help users evaluate the benefit of the financial report. Therefore, financial reports must be presented accurately, comparably, be verifiable, on time and understandable. Hence, it must be transparent and error-free. It is important that the financial report must be on time and predictable as an indicator to produce high-quality financial report ( Mbawuni, 2019 ).

The IASC, which was established in 1973, published the first IAS in 1975. Since then, the process for establishing IAS has undergone significant change, culminating in the reorganization of the IASC into the IASB in 2001. The IASC changed to the IASB to answer the challenge of how financial reporting should be carried out and further develop high-quality and global accounting standards, namely IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standard). The world's great demand today is to be oriented towards one reporting standard that applies globally so as to increase the credibility and usefulness of financial reports as well as financial transparency. In 2000, the International Organization of Securities Commissions recommended that global securities regulators permit foreign issuers to use IAS for cross-border offerings ( IOSCO, 2000 ). IOSCO facilitates the offering of these securities with high quality, internationally accepted accounting standards used by multinational issuers through collaboration with the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC) to develop a set of accounting standards. Since 2005, nearly all publicly traded companies in Europe and numerous other nations have been required to produce financial statements in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). In addition, the Financial Accounting Standards Board has begun an extensive initiative to converge IFRS and US accounting standards ( Barth et al ., 2008 ).

2.1.2 Information usefulness of accounting

An organization which organized the accounting standards fully support that financial reports have the purpose of presenting financial information which will benefit users. The purpose is to have a better understanding of the firm’s financial position ( IASB, 2018 ; Rusdiyanto et al ., 2021 ). Thus, users can make economic decisions. Accounting information is used to evaluate the business performance, and it is also useful for owners to do some analysis in evaluating business operation. Financial ratios can be used as an indicator to compare its performance against other firms within the same business or industry standard ( Vitez and Seidel, 2019 ). This can help owners to understand how good its company is, compared to others.

2.1.3 Clean surplus theory

Clean surplus theory is a foundation theory that is relevant to the accounting information value. This theory mentions that the firm’s value (FV) is reflected in the accounting data, which is shown on the financial report ( Ohlson, 1995 ). Clean surplus theory has an impact on the development of financial accounting theory, especially as it can demonstrate that the FV has an equal value with dividend financial accounting variable or cash flow. This was then followed by more research in predicting profit ( Scott, 2015 , p. 233; Schroeder et al. , 2020 ). According to ( Djaballah, 2019 ), financial information has the function of forecasting and analysis which describe the firm’s condition. It shows that financial reports are not only used as an information perspective for users but also have the benefits to evaluate the usage of the financial report.

2.2 Conceptual framework

Figure 1 is available in supplementary material to article.

2.3 Hypothesis development

2.3.1 testing of the dynamic factors of financial reporting quality and its impact on the firm’s value.

To achieve this objective, the IASC and IASB have issued principle-based accounting standards and taken measures to eliminate allowable accounting alternatives and mandate accounting measurements that more accurately reflect a company’s economic position and performance. Accounting amounts that more accurately reflect a company’s underlying economics, whether because of principle-based accounting standards or required accounting measurements, can improve accounting quality because they provide investors with information to assist them in making investment decisions. The relationship between these two sources of higher accounting quality is that limiting managers’ opportunistic discretion increases the extent to which accounting quantities reflect a company’s underlying economics. According to Ewert and Wagenhofer (2005 ), developing a rational expectations model that demonstrates that accounting standards that limit opportunistic discretion results in accounting earnings that are more reflective of a firm’s underlying economics and, therefore, are of higher quality ( Barth et al ., 2008 ).

Innate factors of the quality financial reporting consist of an operation cycle, sales volatility, firms’ size and firms’ age. In this case, a firms’ operation cycle is the most important variable to operate a company. Hence, it needs a firm’s operation cycle, which can be understood by all employees ( Arachchi et al. , 2017 ). High sales volatility shows that sales information has the wrong estimation, which can cause un-persistent results ( Nezami et al ., 2018 ; Prasetyo et al ., 2023 ). The unstable sales proxied by high sales volatility will make lower firms’ valuation and vice versa. The quality of financial reporting is especially important in maintaining the efficiency of financial markets because market participants, such as investors, lenders and regulators, rely on financial reporting information to make decisions. A series of studies have discussed the impact of the 2008 financial crisis on the quality of financial reporting ( Prasetyo et al ., 2023 ). Like those of the 2008 financial crisis, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused significant disruption to financial markets and the global economy, but the impact of COVID-19 on the quality of financial reporting is unclear. To date, only a few studies have successfully investigated this issue, but none have focused on settings with strong country-level governance ( Prabowo et al ., 2020 ). Our study uses data from the UK where country-level governance is strong and will add to the current literature. Furthermore, corporate governance has always been a major concern in studies of financial crises ( Hsu and Yang, 2022 ; Agustia et al. , 2020 ).

The results of the study show that there is a positive relationship between managerial ownership, institutional ownership and financial reporting transparency. These results indicate that corporate governance has a significant relationship with financial reporting transparency. This is because the transparency of the financial reporting of companies whose shares are attractive to investors who are active in financial markets, is one of the main elements of the contemporary economy. Enhancing the transparency and accountability of the activities of economic organizations requires the principle of organizational social responsibility and thereby monitoring its implementation. The findings of this study indicate a positive relationship between corporate governance and transparency. This study is unique in that it emphasizes the importance of financial reporting transparency, and the impact of Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) on corporate governance attributes ( Salehi et al ., 2022 ).

A firm’s operational cycle will determine the quality of the financial report, either good or bad. A firm with a longer operational cycle shows unexpected things, as inaccurate estimation will occur. Some errors of estimation will produce low accrual value as a result it will have low quality of financial reporting ( Dechow and Dichev, 2002 ). Sales volatility shows the ability to forecast the cash flow in the future. High sales volatility will produce low financial report performance, and it is due to some noises in the firm’s profit ( Cohen, 2008 ).

The longer of a firm’s operational cycle is resulted in low quality of financial report, hence, low firm’s valuation.

The higher sales volatility of a firm is resulted in low quality of financial report, hence, low firm’s valuation.

2.3.2 Testing of the static factors of financial reporting quality and its impact on the firm’s value

Most of the research found that the size and age of a firm influence the value of a company. Big firms have stable financial condition ( Rouf, 2018 ). It is, therefore, increasing the company’s value; hence, it attracts investors. As a result, increasing the stock market price will affect and increase the value of one firm. According to accounting theory, the primary goal of reporting is to offer useful information to those who are most interested in financial reports. Data derived from the accounting information system represent one of the most reliable resources at the disposal of users to make decisions about business entities. The ultimate outcome of accounting information systems is financial reporting. All users rely on these financial reports to assess business entities. If financial reporting is of standard quality, it will allow users to make accurate decisions. Major users of such information include investors, creditors, employees, customers, commercial creditors and government. These sound decisions will lead to systematic allocation of resources, which will have a significant impact on the optimum allocation of resources in the economy of a country. In this respect, one of the determining factors that enhance the quality of information and reduce the information risk of corporate reports is provision of higher quality audit services ( Shiri et al ., 2018 ).