Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

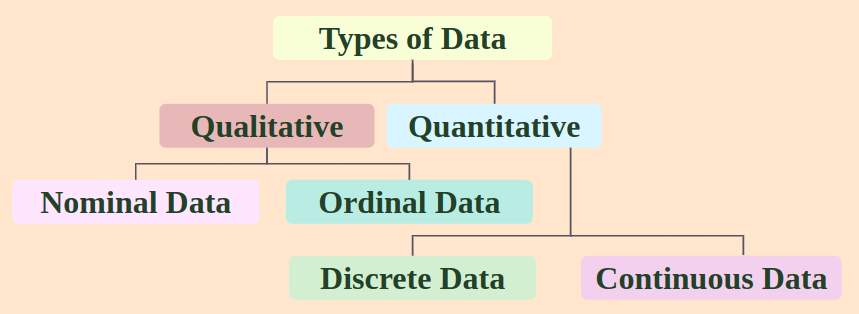

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

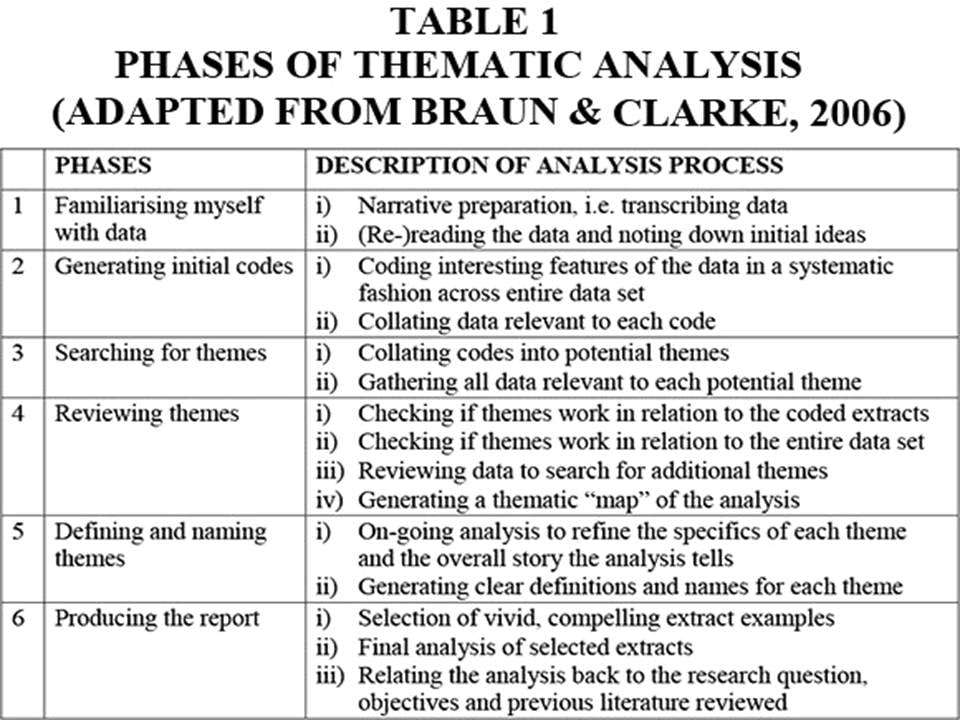

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorize common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 30, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a type of research methodology that focuses on exploring and understanding people’s beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and experiences through the collection and analysis of non-numerical data. It seeks to answer research questions through the examination of subjective data, such as interviews, focus groups, observations, and textual analysis.

Qualitative research aims to uncover the meaning and significance of social phenomena, and it typically involves a more flexible and iterative approach to data collection and analysis compared to quantitative research. Qualitative research is often used in fields such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative Research Methods are as follows:

One-to-One Interview

This method involves conducting an interview with a single participant to gain a detailed understanding of their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. One-to-one interviews can be conducted in-person, over the phone, or through video conferencing. The interviewer typically uses open-ended questions to encourage the participant to share their thoughts and feelings. One-to-one interviews are useful for gaining detailed insights into individual experiences.

Focus Groups

This method involves bringing together a group of people to discuss a specific topic in a structured setting. The focus group is led by a moderator who guides the discussion and encourages participants to share their thoughts and opinions. Focus groups are useful for generating ideas and insights, exploring social norms and attitudes, and understanding group dynamics.

Ethnographic Studies

This method involves immersing oneself in a culture or community to gain a deep understanding of its norms, beliefs, and practices. Ethnographic studies typically involve long-term fieldwork and observation, as well as interviews and document analysis. Ethnographic studies are useful for understanding the cultural context of social phenomena and for gaining a holistic understanding of complex social processes.

Text Analysis

This method involves analyzing written or spoken language to identify patterns and themes. Text analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative text analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Text analysis is useful for understanding media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

This method involves an in-depth examination of a single person, group, or event to gain an understanding of complex phenomena. Case studies typically involve a combination of data collection methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case. Case studies are useful for exploring unique or rare cases, and for generating hypotheses for further research.

Process of Observation

This method involves systematically observing and recording behaviors and interactions in natural settings. The observer may take notes, use audio or video recordings, or use other methods to document what they see. Process of observation is useful for understanding social interactions, cultural practices, and the context in which behaviors occur.

Record Keeping

This method involves keeping detailed records of observations, interviews, and other data collected during the research process. Record keeping is essential for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the data, and for providing a basis for analysis and interpretation.

This method involves collecting data from a large sample of participants through a structured questionnaire. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, through mail, or online. Surveys are useful for collecting data on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, and for identifying patterns and trends in a population.

Qualitative data analysis is a process of turning unstructured data into meaningful insights. It involves extracting and organizing information from sources like interviews, focus groups, and surveys. The goal is to understand people’s attitudes, behaviors, and motivations

Qualitative Research Analysis Methods

Qualitative Research analysis methods involve a systematic approach to interpreting and making sense of the data collected in qualitative research. Here are some common qualitative data analysis methods:

Thematic Analysis

This method involves identifying patterns or themes in the data that are relevant to the research question. The researcher reviews the data, identifies keywords or phrases, and groups them into categories or themes. Thematic analysis is useful for identifying patterns across multiple data sources and for generating new insights into the research topic.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing the content of written or spoken language to identify key themes or concepts. Content analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative content analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Content analysis is useful for identifying patterns in media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

Discourse Analysis

This method involves analyzing language to understand how it constructs meaning and shapes social interactions. Discourse analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as conversation analysis, critical discourse analysis, and narrative analysis. Discourse analysis is useful for understanding how language shapes social interactions, cultural norms, and power relationships.

Grounded Theory Analysis

This method involves developing a theory or explanation based on the data collected. Grounded theory analysis starts with the data and uses an iterative process of coding and analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data. The theory or explanation that emerges is grounded in the data, rather than preconceived hypotheses. Grounded theory analysis is useful for understanding complex social phenomena and for generating new theoretical insights.

Narrative Analysis

This method involves analyzing the stories or narratives that participants share to gain insights into their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. Narrative analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as structural analysis, thematic analysis, and discourse analysis. Narrative analysis is useful for understanding how individuals construct their identities, make sense of their experiences, and communicate their values and beliefs.

Phenomenological Analysis

This method involves analyzing how individuals make sense of their experiences and the meanings they attach to them. Phenomenological analysis typically involves in-depth interviews with participants to explore their experiences in detail. Phenomenological analysis is useful for understanding subjective experiences and for developing a rich understanding of human consciousness.

Comparative Analysis

This method involves comparing and contrasting data across different cases or groups to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can be used to identify patterns or themes that are common across multiple cases, as well as to identify unique or distinctive features of individual cases. Comparative analysis is useful for understanding how social phenomena vary across different contexts and groups.

Applications of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research has many applications across different fields and industries. Here are some examples of how qualitative research is used:

- Market Research: Qualitative research is often used in market research to understand consumer attitudes, behaviors, and preferences. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with consumers to gather insights into their experiences and perceptions of products and services.

- Health Care: Qualitative research is used in health care to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education: Qualitative research is used in education to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. Researchers conduct classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work : Qualitative research is used in social work to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : Qualitative research is used in anthropology to understand different cultures and societies. Researchers conduct ethnographic studies and observe and interview members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : Qualitative research is used in psychology to understand human behavior and mental processes. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy : Qualitative research is used in public policy to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

How to Conduct Qualitative Research

Here are some general steps for conducting qualitative research:

- Identify your research question: Qualitative research starts with a research question or set of questions that you want to explore. This question should be focused and specific, but also broad enough to allow for exploration and discovery.

- Select your research design: There are different types of qualitative research designs, including ethnography, case study, grounded theory, and phenomenology. You should select a design that aligns with your research question and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Recruit participants: Once you have your research question and design, you need to recruit participants. The number of participants you need will depend on your research design and the scope of your research. You can recruit participants through advertisements, social media, or through personal networks.

- Collect data: There are different methods for collecting qualitative data, including interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. You should select the method or methods that align with your research design and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Analyze data: Once you have collected your data, you need to analyze it. This involves reviewing your data, identifying patterns and themes, and developing codes to organize your data. You can use different software programs to help you analyze your data, or you can do it manually.

- Interpret data: Once you have analyzed your data, you need to interpret it. This involves making sense of the patterns and themes you have identified, and developing insights and conclusions that answer your research question. You should be guided by your research question and use your data to support your conclusions.

- Communicate results: Once you have interpreted your data, you need to communicate your results. This can be done through academic papers, presentations, or reports. You should be clear and concise in your communication, and use examples and quotes from your data to support your findings.

Examples of Qualitative Research

Here are some real-time examples of qualitative research:

- Customer Feedback: A company may conduct qualitative research to understand the feedback and experiences of its customers. This may involve conducting focus groups or one-on-one interviews with customers to gather insights into their attitudes, behaviors, and preferences.

- Healthcare : A healthcare provider may conduct qualitative research to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education : An educational institution may conduct qualitative research to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. This may involve conducting classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work: A social worker may conduct qualitative research to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : An anthropologist may conduct qualitative research to understand different cultures and societies. This may involve conducting ethnographic studies and observing and interviewing members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : A psychologist may conduct qualitative research to understand human behavior and mental processes. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy: A government agency or non-profit organization may conduct qualitative research to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. This may involve conducting focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

Purpose of Qualitative Research

The purpose of qualitative research is to explore and understand the subjective experiences, behaviors, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on numerical data and statistical analysis, qualitative research aims to provide in-depth, descriptive information that can help researchers develop insights and theories about complex social phenomena.

Qualitative research can serve multiple purposes, including:

- Exploring new or emerging phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring new or emerging phenomena, such as new technologies or social trends. This type of research can help researchers develop a deeper understanding of these phenomena and identify potential areas for further study.

- Understanding complex social phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring complex social phenomena, such as cultural beliefs, social norms, or political processes. This type of research can help researchers develop a more nuanced understanding of these phenomena and identify factors that may influence them.

- Generating new theories or hypotheses: Qualitative research can be useful for generating new theories or hypotheses about social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data about individuals’ experiences and perspectives, researchers can develop insights that may challenge existing theories or lead to new lines of inquiry.

- Providing context for quantitative data: Qualitative research can be useful for providing context for quantitative data. By gathering qualitative data alongside quantitative data, researchers can develop a more complete understanding of complex social phenomena and identify potential explanations for quantitative findings.

When to use Qualitative Research

Here are some situations where qualitative research may be appropriate:

- Exploring a new area: If little is known about a particular topic, qualitative research can help to identify key issues, generate hypotheses, and develop new theories.

- Understanding complex phenomena: Qualitative research can be used to investigate complex social, cultural, or organizational phenomena that are difficult to measure quantitatively.

- Investigating subjective experiences: Qualitative research is particularly useful for investigating the subjective experiences of individuals or groups, such as their attitudes, beliefs, values, or emotions.

- Conducting formative research: Qualitative research can be used in the early stages of a research project to develop research questions, identify potential research participants, and refine research methods.

- Evaluating interventions or programs: Qualitative research can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions or programs by collecting data on participants’ experiences, attitudes, and behaviors.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is characterized by several key features, including:

- Focus on subjective experience: Qualitative research is concerned with understanding the subjective experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Researchers aim to explore the meanings that people attach to their experiences and to understand the social and cultural factors that shape these meanings.

- Use of open-ended questions: Qualitative research relies on open-ended questions that allow participants to provide detailed, in-depth responses. Researchers seek to elicit rich, descriptive data that can provide insights into participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Sampling-based on purpose and diversity: Qualitative research often involves purposive sampling, in which participants are selected based on specific criteria related to the research question. Researchers may also seek to include participants with diverse experiences and perspectives to capture a range of viewpoints.

- Data collection through multiple methods: Qualitative research typically involves the use of multiple data collection methods, such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation. This allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data from multiple sources, which can provide a more complete picture of participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Inductive data analysis: Qualitative research relies on inductive data analysis, in which researchers develop theories and insights based on the data rather than testing pre-existing hypotheses. Researchers use coding and thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data and to develop theories and explanations based on these patterns.

- Emphasis on researcher reflexivity: Qualitative research recognizes the importance of the researcher’s role in shaping the research process and outcomes. Researchers are encouraged to reflect on their own biases and assumptions and to be transparent about their role in the research process.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research offers several advantages over other research methods, including:

- Depth and detail: Qualitative research allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data that provides a deeper understanding of complex social phenomena. Through in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation, researchers can gather detailed information about participants’ experiences and perspectives that may be missed by other research methods.

- Flexibility : Qualitative research is a flexible approach that allows researchers to adapt their methods to the research question and context. Researchers can adjust their research methods in real-time to gather more information or explore unexpected findings.

- Contextual understanding: Qualitative research is well-suited to exploring the social and cultural context in which individuals or groups are situated. Researchers can gather information about cultural norms, social structures, and historical events that may influence participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Participant perspective : Qualitative research prioritizes the perspective of participants, allowing researchers to explore subjective experiences and understand the meanings that participants attach to their experiences.

- Theory development: Qualitative research can contribute to the development of new theories and insights about complex social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data and using inductive data analysis, researchers can develop new theories and explanations that may challenge existing understandings.

- Validity : Qualitative research can offer high validity by using multiple data collection methods, purposive and diverse sampling, and researcher reflexivity. This can help ensure that findings are credible and trustworthy.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research also has some limitations, including:

- Subjectivity : Qualitative research relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers, which can introduce bias into the research process. The researcher’s perspective, beliefs, and experiences can influence the way data is collected, analyzed, and interpreted.

- Limited generalizability: Qualitative research typically involves small, purposive samples that may not be representative of larger populations. This limits the generalizability of findings to other contexts or populations.

- Time-consuming: Qualitative research can be a time-consuming process, requiring significant resources for data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

- Resource-intensive: Qualitative research may require more resources than other research methods, including specialized training for researchers, specialized software for data analysis, and transcription services.

- Limited reliability: Qualitative research may be less reliable than quantitative research, as it relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers. This can make it difficult to replicate findings or compare results across different studies.

- Ethics and confidentiality: Qualitative research involves collecting sensitive information from participants, which raises ethical concerns about confidentiality and informed consent. Researchers must take care to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants and obtain informed consent.

Also see Research Methods

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and...

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Qualitative Research : Definition

Qualitative research is the naturalistic study of social meanings and processes, using interviews, observations, and the analysis of texts and images. In contrast to quantitative researchers, whose statistical methods enable broad generalizations about populations (for example, comparisons of the percentages of U.S. demographic groups who vote in particular ways), qualitative researchers use in-depth studies of the social world to analyze how and why groups think and act in particular ways (for instance, case studies of the experiences that shape political views).

Events and Workshops

- Introduction to NVivo Have you just collected your data and wondered what to do next? Come join us for an introductory session on utilizing NVivo to support your analytical process. This session will only cover features of the software and how to import your records. Please feel free to attend any of the following sessions below: April 25th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125 May 9th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125

- Next: Choose an approach >>

- Choose an approach

- Find studies

- Learn methods

- Getting Started

- Get software

- Get data for secondary analysis

- Network with researchers

- Last Updated: Aug 9, 2024 2:09 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.stanford.edu/qualitative_research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

What is Qualitative in Qualitative Research

Patrik aspers.

1 Department of Sociology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

2 Seminar for Sociology, Universität St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland

3 Department of Media and Social Sciences, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway

What is qualitative research? If we look for a precise definition of qualitative research, and specifically for one that addresses its distinctive feature of being “qualitative,” the literature is meager. In this article we systematically search, identify and analyze a sample of 89 sources using or attempting to define the term “qualitative.” Then, drawing on ideas we find scattered across existing work, and based on Becker’s classic study of marijuana consumption, we formulate and illustrate a definition that tries to capture its core elements. We define qualitative research as an iterative process in which improved understanding to the scientific community is achieved by making new significant distinctions resulting from getting closer to the phenomenon studied. This formulation is developed as a tool to help improve research designs while stressing that a qualitative dimension is present in quantitative work as well. Additionally, it can facilitate teaching, communication between researchers, diminish the gap between qualitative and quantitative researchers, help to address critiques of qualitative methods, and be used as a standard of evaluation of qualitative research.

If we assume that there is something called qualitative research, what exactly is this qualitative feature? And how could we evaluate qualitative research as good or not? Is it fundamentally different from quantitative research? In practice, most active qualitative researchers working with empirical material intuitively know what is involved in doing qualitative research, yet perhaps surprisingly, a clear definition addressing its key feature is still missing.

To address the question of what is qualitative we turn to the accounts of “qualitative research” in textbooks and also in empirical work. In his classic, explorative, interview study of deviance Howard Becker ( 1963 ) asks ‘How does one become a marijuana user?’ In contrast to pre-dispositional and psychological-individualistic theories of deviant behavior, Becker’s inherently social explanation contends that becoming a user of this substance is the result of a three-phase sequential learning process. First, potential users need to learn how to smoke it properly to produce the “correct” effects. If not, they are likely to stop experimenting with it. Second, they need to discover the effects associated with it; in other words, to get “high,” individuals not only have to experience what the drug does, but also to become aware that those sensations are related to using it. Third, they require learning to savor the feelings related to its consumption – to develop an acquired taste. Becker, who played music himself, gets close to the phenomenon by observing, taking part, and by talking to people consuming the drug: “half of the fifty interviews were conducted with musicians, the other half covered a wide range of people, including laborers, machinists, and people in the professions” (Becker 1963 :56).

Another central aspect derived through the common-to-all-research interplay between induction and deduction (Becker 2017 ), is that during the course of his research Becker adds scientifically meaningful new distinctions in the form of three phases—distinctions, or findings if you will, that strongly affect the course of his research: its focus, the material that he collects, and which eventually impact his findings. Each phase typically unfolds through social interaction, and often with input from experienced users in “a sequence of social experiences during which the person acquires a conception of the meaning of the behavior, and perceptions and judgments of objects and situations, all of which make the activity possible and desirable” (Becker 1963 :235). In this study the increased understanding of smoking dope is a result of a combination of the meaning of the actors, and the conceptual distinctions that Becker introduces based on the views expressed by his respondents. Understanding is the result of research and is due to an iterative process in which data, concepts and evidence are connected with one another (Becker 2017 ).

Indeed, there are many definitions of qualitative research, but if we look for a definition that addresses its distinctive feature of being “qualitative,” the literature across the broad field of social science is meager. The main reason behind this article lies in the paradox, which, to put it bluntly, is that researchers act as if they know what it is, but they cannot formulate a coherent definition. Sociologists and others will of course continue to conduct good studies that show the relevance and value of qualitative research addressing scientific and practical problems in society. However, our paper is grounded in the idea that providing a clear definition will help us improve the work that we do. Among researchers who practice qualitative research there is clearly much knowledge. We suggest that a definition makes this knowledge more explicit. If the first rationale for writing this paper refers to the “internal” aim of improving qualitative research, the second refers to the increased “external” pressure that especially many qualitative researchers feel; pressure that comes both from society as well as from other scientific approaches. There is a strong core in qualitative research, and leading researchers tend to agree on what it is and how it is done. Our critique is not directed at the practice of qualitative research, but we do claim that the type of systematic work we do has not yet been done, and that it is useful to improve the field and its status in relation to quantitative research.

The literature on the “internal” aim of improving, or at least clarifying qualitative research is large, and we do not claim to be the first to notice the vagueness of the term “qualitative” (Strauss and Corbin 1998 ). Also, others have noted that there is no single definition of it (Long and Godfrey 2004 :182), that there are many different views on qualitative research (Denzin and Lincoln 2003 :11; Jovanović 2011 :3), and that more generally, we need to define its meaning (Best 2004 :54). Strauss and Corbin ( 1998 ), for example, as well as Nelson et al. (1992:2 cited in Denzin and Lincoln 2003 :11), and Flick ( 2007 :ix–x), have recognized that the term is problematic: “Actually, the term ‘qualitative research’ is confusing because it can mean different things to different people” (Strauss and Corbin 1998 :10–11). Hammersley has discussed the possibility of addressing the problem, but states that “the task of providing an account of the distinctive features of qualitative research is far from straightforward” ( 2013 :2). This confusion, as he has recently further argued (Hammersley 2018 ), is also salient in relation to ethnography where different philosophical and methodological approaches lead to a lack of agreement about what it means.

Others (e.g. Hammersley 2018 ; Fine and Hancock 2017 ) have also identified the treat to qualitative research that comes from external forces, seen from the point of view of “qualitative research.” This threat can be further divided into that which comes from inside academia, such as the critique voiced by “quantitative research” and outside of academia, including, for example, New Public Management. Hammersley ( 2018 ), zooming in on one type of qualitative research, ethnography, has argued that it is under treat. Similarly to Fine ( 2003 ), and before him Gans ( 1999 ), he writes that ethnography’ has acquired a range of meanings, and comes in many different versions, these often reflecting sharply divergent epistemological orientations. And already more than twenty years ago while reviewing Denzin and Lincoln’ s Handbook of Qualitative Methods Fine argued:

While this increasing centrality [of qualitative research] might lead one to believe that consensual standards have developed, this belief would be misleading. As the methodology becomes more widely accepted, querulous challengers have raised fundamental questions that collectively have undercut the traditional models of how qualitative research is to be fashioned and presented (1995:417).

According to Hammersley, there are today “serious treats to the practice of ethnographic work, on almost any definition” ( 2018 :1). He lists five external treats: (1) that social research must be accountable and able to show its impact on society; (2) the current emphasis on “big data” and the emphasis on quantitative data and evidence; (3) the labor market pressure in academia that leaves less time for fieldwork (see also Fine and Hancock 2017 ); (4) problems of access to fields; and (5) the increased ethical scrutiny of projects, to which ethnography is particularly exposed. Hammersley discusses some more or less insufficient existing definitions of ethnography.

The current situation, as Hammersley and others note—and in relation not only to ethnography but also qualitative research in general, and as our empirical study shows—is not just unsatisfactory, it may even be harmful for the entire field of qualitative research, and does not help social science at large. We suggest that the lack of clarity of qualitative research is a real problem that must be addressed.

Towards a Definition of Qualitative Research

Seen in an historical light, what is today called qualitative, or sometimes ethnographic, interpretative research – or a number of other terms – has more or less always existed. At the time the founders of sociology – Simmel, Weber, Durkheim and, before them, Marx – were writing, and during the era of the Methodenstreit (“dispute about methods”) in which the German historical school emphasized scientific methods (cf. Swedberg 1990 ), we can at least speak of qualitative forerunners.

Perhaps the most extended discussion of what later became known as qualitative methods in a classic work is Bronisław Malinowski’s ( 1922 ) Argonauts in the Western Pacific , although even this study does not explicitly address the meaning of “qualitative.” In Weber’s ([1921–-22] 1978) work we find a tension between scientific explanations that are based on observation and quantification and interpretative research (see also Lazarsfeld and Barton 1982 ).

If we look through major sociology journals like the American Sociological Review , American Journal of Sociology , or Social Forces we will not find the term qualitative sociology before the 1970s. And certainly before then much of what we consider qualitative classics in sociology, like Becker’ study ( 1963 ), had already been produced. Indeed, the Chicago School often combined qualitative and quantitative data within the same study (Fine 1995 ). Our point being that before a disciplinary self-awareness the term quantitative preceded qualitative, and the articulation of the former was a political move to claim scientific status (Denzin and Lincoln 2005 ). In the US the World War II seem to have sparked a critique of sociological work, including “qualitative work,” that did not follow the scientific canon (Rawls 2018 ), which was underpinned by a scientifically oriented and value free philosophy of science. As a result the attempts and practice of integrating qualitative and quantitative sociology at Chicago lost ground to sociology that was more oriented to surveys and quantitative work at Columbia under Merton-Lazarsfeld. The quantitative tradition was also able to present textbooks (Lundberg 1951 ) that facilitated the use this approach and its “methods.” The practices of the qualitative tradition, by and large, remained tacit or was part of the mentoring transferred from the renowned masters to their students.

This glimpse into history leads us back to the lack of a coherent account condensed in a definition of qualitative research. Many of the attempts to define the term do not meet the requirements of a proper definition: A definition should be clear, avoid tautology, demarcate its domain in relation to the environment, and ideally only use words in its definiens that themselves are not in need of definition (Hempel 1966 ). A definition can enhance precision and thus clarity by identifying the core of the phenomenon. Preferably, a definition should be short. The typical definition we have found, however, is an ostensive definition, which indicates what qualitative research is about without informing us about what it actually is :

Qualitative research is multimethod in focus, involving an interpretative, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Qualitative research involves the studied use and collection of a variety of empirical materials – case study, personal experience, introspective, life story, interview, observational, historical, interactional, and visual texts – that describe routine and problematic moments and meanings in individuals’ lives. (Denzin and Lincoln 2005 :2)

Flick claims that the label “qualitative research” is indeed used as an umbrella for a number of approaches ( 2007 :2–4; 2002 :6), and it is not difficult to identify research fitting this designation. Moreover, whatever it is, it has grown dramatically over the past five decades. In addition, courses have been developed, methods have flourished, arguments about its future have been advanced (for example, Denzin and Lincoln 1994) and criticized (for example, Snow and Morrill 1995 ), and dedicated journals and books have mushroomed. Most social scientists have a clear idea of research and how it differs from journalism, politics and other activities. But the question of what is qualitative in qualitative research is either eluded or eschewed.

We maintain that this lacuna hinders systematic knowledge production based on qualitative research. Paul Lazarsfeld noted the lack of “codification” as early as 1955 when he reviewed 100 qualitative studies in order to offer a codification of the practices (Lazarsfeld and Barton 1982 :239). Since then many texts on “qualitative research” and its methods have been published, including recent attempts (Goertz and Mahoney 2012 ) similar to Lazarsfeld’s. These studies have tried to extract what is qualitative by looking at the large number of empirical “qualitative” studies. Our novel strategy complements these endeavors by taking another approach and looking at the attempts to codify these practices in the form of a definition, as well as to a minor extent take Becker’s study as an exemplar of what qualitative researchers actually do, and what the characteristic of being ‘qualitative’ denotes and implies. We claim that qualitative researchers, if there is such a thing as “qualitative research,” should be able to codify their practices in a condensed, yet general way expressed in language.

Lingering problems of “generalizability” and “how many cases do I need” (Small 2009 ) are blocking advancement – in this line of work qualitative approaches are said to differ considerably from quantitative ones, while some of the former unsuccessfully mimic principles related to the latter (Small 2009 ). Additionally, quantitative researchers sometimes unfairly criticize the first based on their own quality criteria. Scholars like Goertz and Mahoney ( 2012 ) have successfully focused on the different norms and practices beyond what they argue are essentially two different cultures: those working with either qualitative or quantitative methods. Instead, similarly to Becker ( 2017 ) who has recently questioned the usefulness of the distinction between qualitative and quantitative research, we focus on similarities.

The current situation also impedes both students and researchers in focusing their studies and understanding each other’s work (Lazarsfeld and Barton 1982 :239). A third consequence is providing an opening for critiques by scholars operating within different traditions (Valsiner 2000 :101). A fourth issue is that the “implicit use of methods in qualitative research makes the field far less standardized than the quantitative paradigm” (Goertz and Mahoney 2012 :9). Relatedly, the National Science Foundation in the US organized two workshops in 2004 and 2005 to address the scientific foundations of qualitative research involving strategies to improve it and to develop standards of evaluation in qualitative research. However, a specific focus on its distinguishing feature of being “qualitative” while being implicitly acknowledged, was discussed only briefly (for example, Best 2004 ).

In 2014 a theme issue was published in this journal on “Methods, Materials, and Meanings: Designing Cultural Analysis,” discussing central issues in (cultural) qualitative research (Berezin 2014 ; Biernacki 2014 ; Glaeser 2014 ; Lamont and Swidler 2014 ; Spillman 2014). We agree with many of the arguments put forward, such as the risk of methodological tribalism, and that we should not waste energy on debating methods separated from research questions. Nonetheless, a clarification of the relation to what is called “quantitative research” is of outmost importance to avoid misunderstandings and misguided debates between “qualitative” and “quantitative” researchers. Our strategy means that researchers, “qualitative” or “quantitative” they may be, in their actual practice may combine qualitative work and quantitative work.

In this article we accomplish three tasks. First, we systematically survey the literature for meanings of qualitative research by looking at how researchers have defined it. Drawing upon existing knowledge we find that the different meanings and ideas of qualitative research are not yet coherently integrated into one satisfactory definition. Next, we advance our contribution by offering a definition of qualitative research and illustrate its meaning and use partially by expanding on the brief example introduced earlier related to Becker’s work ( 1963 ). We offer a systematic analysis of central themes of what researchers consider to be the core of “qualitative,” regardless of style of work. These themes – which we summarize in terms of four keywords: distinction, process, closeness, improved understanding – constitute part of our literature review, in which each one appears, sometimes with others, but never all in the same definition. They serve as the foundation of our contribution. Our categories are overlapping. Their use is primarily to organize the large amount of definitions we have identified and analyzed, and not necessarily to draw a clear distinction between them. Finally, we continue the elaboration discussed above on the advantages of a clear definition of qualitative research.

In a hermeneutic fashion we propose that there is something meaningful that deserves to be labelled “qualitative research” (Gadamer 1990 ). To approach the question “What is qualitative in qualitative research?” we have surveyed the literature. In conducting our survey we first traced the word’s etymology in dictionaries, encyclopedias, handbooks of the social sciences and of methods and textbooks, mainly in English, which is common to methodology courses. It should be noted that we have zoomed in on sociology and its literature. This discipline has been the site of the largest debate and development of methods that can be called “qualitative,” which suggests that this field should be examined in great detail.

In an ideal situation we should expect that one good definition, or at least some common ideas, would have emerged over the years. This common core of qualitative research should be so accepted that it would appear in at least some textbooks. Since this is not what we found, we decided to pursue an inductive approach to capture maximal variation in the field of qualitative research; we searched in a selection of handbooks, textbooks, book chapters, and books, to which we added the analysis of journal articles. Our sample comprises a total of 89 references.

In practice we focused on the discipline that has had a clear discussion of methods, namely sociology. We also conducted a broad search in the JSTOR database to identify scholarly sociology articles published between 1998 and 2017 in English with a focus on defining or explaining qualitative research. We specifically zoom in on this time frame because we would have expect that this more mature period would have produced clear discussions on the meaning of qualitative research. To find these articles we combined a number of keywords to search the content and/or the title: qualitative (which was always included), definition, empirical, research, methodology, studies, fieldwork, interview and observation .

As a second phase of our research we searched within nine major sociological journals ( American Journal of Sociology , Sociological Theory , American Sociological Review , Contemporary Sociology , Sociological Forum , Sociological Theory , Qualitative Research , Qualitative Sociology and Qualitative Sociology Review ) for articles also published during the past 19 years (1998–2017) that had the term “qualitative” in the title and attempted to define qualitative research.

Lastly we picked two additional journals, Qualitative Research and Qualitative Sociology , in which we could expect to find texts addressing the notion of “qualitative.” From Qualitative Research we chose Volume 14, Issue 6, December 2014, and from Qualitative Sociology we chose Volume 36, Issue 2, June 2017. Within each of these we selected the first article; then we picked the second article of three prior issues. Again we went back another three issues and investigated article number three. Finally we went back another three issues and perused article number four. This selection criteria was used to get a manageable sample for the analysis.

The coding process of the 89 references we gathered in our selected review began soon after the first round of material was gathered, and we reduced the complexity created by our maximum variation sampling (Snow and Anderson 1993 :22) to four different categories within which questions on the nature and properties of qualitative research were discussed. We call them: Qualitative and Quantitative Research, Qualitative Research, Fieldwork, and Grounded Theory. This – which may appear as an illogical grouping – merely reflects the “context” in which the matter of “qualitative” is discussed. If the selection process of the material – books and articles – was informed by pre-knowledge, we used an inductive strategy to code the material. When studying our material, we identified four central notions related to “qualitative” that appear in various combinations in the literature which indicate what is the core of qualitative research. We have labeled them: “distinctions”, “process,” “closeness,” and “improved understanding.” During the research process the categories and notions were improved, refined, changed, and reordered. The coding ended when a sense of saturation in the material arose. In the presentation below all quotations and references come from our empirical material of texts on qualitative research.

Analysis – What is Qualitative Research?

In this section we describe the four categories we identified in the coding, how they differently discuss qualitative research, as well as their overall content. Some salient quotations are selected to represent the type of text sorted under each of the four categories. What we present are examples from the literature.

Qualitative and Quantitative

This analytic category comprises quotations comparing qualitative and quantitative research, a distinction that is frequently used (Brown 2010 :231); in effect this is a conceptual pair that structures the discussion and that may be associated with opposing interests. While the general goal of quantitative and qualitative research is the same – to understand the world better – their methodologies and focus in certain respects differ substantially (Becker 1966 :55). Quantity refers to that property of something that can be determined by measurement. In a dictionary of Statistics and Methodology we find that “(a) When referring to *variables, ‘qualitative’ is another term for *categorical or *nominal. (b) When speaking of kinds of research, ‘qualitative’ refers to studies of subjects that are hard to quantify, such as art history. Qualitative research tends to be a residual category for almost any kind of non-quantitative research” (Stiles 1998:183). But it should be obvious that one could employ a quantitative approach when studying, for example, art history.

The same dictionary states that quantitative is “said of variables or research that can be handled numerically, usually (too sharply) contrasted with *qualitative variables and research” (Stiles 1998:184). From a qualitative perspective “quantitative research” is about numbers and counting, and from a quantitative perspective qualitative research is everything that is not about numbers. But this does not say much about what is “qualitative.” If we turn to encyclopedias we find that in the 1932 edition of the Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences there is no mention of “qualitative.” In the Encyclopedia from 1968 we can read:

Qualitative Analysis. For methods of obtaining, analyzing, and describing data, see [the various entries:] CONTENT ANALYSIS; COUNTED DATA; EVALUATION RESEARCH, FIELD WORK; GRAPHIC PRESENTATION; HISTORIOGRAPHY, especially the article on THE RHETORIC OF HISTORY; INTERVIEWING; OBSERVATION; PERSONALITY MEASUREMENT; PROJECTIVE METHODS; PSYCHOANALYSIS, article on EXPERIMENTAL METHODS; SURVEY ANALYSIS, TABULAR PRESENTATION; TYPOLOGIES. (Vol. 13:225)

Some, like Alford, divide researchers into methodologists or, in his words, “quantitative and qualitative specialists” (Alford 1998 :12). Qualitative research uses a variety of methods, such as intensive interviews or in-depth analysis of historical materials, and it is concerned with a comprehensive account of some event or unit (King et al. 1994 :4). Like quantitative research it can be utilized to study a variety of issues, but it tends to focus on meanings and motivations that underlie cultural symbols, personal experiences, phenomena and detailed understanding of processes in the social world. In short, qualitative research centers on understanding processes, experiences, and the meanings people assign to things (Kalof et al. 2008 :79).

Others simply say that qualitative methods are inherently unscientific (Jovanović 2011 :19). Hood, for instance, argues that words are intrinsically less precise than numbers, and that they are therefore more prone to subjective analysis, leading to biased results (Hood 2006 :219). Qualitative methodologies have raised concerns over the limitations of quantitative templates (Brady et al. 2004 :4). Scholars such as King et al. ( 1994 ), for instance, argue that non-statistical research can produce more reliable results if researchers pay attention to the rules of scientific inference commonly stated in quantitative research. Also, researchers such as Becker ( 1966 :59; 1970 :42–43) have asserted that, if conducted properly, qualitative research and in particular ethnographic field methods, can lead to more accurate results than quantitative studies, in particular, survey research and laboratory experiments.

Some researchers, such as Kalof, Dan, and Dietz ( 2008 :79) claim that the boundaries between the two approaches are becoming blurred, and Small ( 2009 ) argues that currently much qualitative research (especially in North America) tries unsuccessfully and unnecessarily to emulate quantitative standards. For others, qualitative research tends to be more humanistic and discursive (King et al. 1994 :4). Ragin ( 1994 ), and similarly also Becker, ( 1996 :53), Marchel and Owens ( 2007 :303) think that the main distinction between the two styles is overstated and does not rest on the simple dichotomy of “numbers versus words” (Ragin 1994 :xii). Some claim that quantitative data can be utilized to discover associations, but in order to unveil cause and effect a complex research design involving the use of qualitative approaches needs to be devised (Gilbert 2009 :35). Consequently, qualitative data are useful for understanding the nuances lying beyond those processes as they unfold (Gilbert 2009 :35). Others contend that qualitative research is particularly well suited both to identify causality and to uncover fine descriptive distinctions (Fine and Hallett 2014 ; Lichterman and Isaac Reed 2014 ; Katz 2015 ).

There are other ways to separate these two traditions, including normative statements about what qualitative research should be (that is, better or worse than quantitative approaches, concerned with scientific approaches to societal change or vice versa; Snow and Morrill 1995 ; Denzin and Lincoln 2005 ), or whether it should develop falsifiable statements; Best 2004 ).

We propose that quantitative research is largely concerned with pre-determined variables (Small 2008 ); the analysis concerns the relations between variables. These categories are primarily not questioned in the study, only their frequency or degree, or the correlations between them (cf. Franzosi 2016 ). If a researcher studies wage differences between women and men, he or she works with given categories: x number of men are compared with y number of women, with a certain wage attributed to each person. The idea is not to move beyond the given categories of wage, men and women; they are the starting point as well as the end point, and undergo no “qualitative change.” Qualitative research, in contrast, investigates relations between categories that are themselves subject to change in the research process. Returning to Becker’s study ( 1963 ), we see that he questioned pre-dispositional theories of deviant behavior working with pre-determined variables such as an individual’s combination of personal qualities or emotional problems. His take, in contrast, was to understand marijuana consumption by developing “variables” as part of the investigation. Thereby he presented new variables, or as we would say today, theoretical concepts, but which are grounded in the empirical material.

Qualitative Research

This category contains quotations that refer to descriptions of qualitative research without making comparisons with quantitative research. Researchers such as Denzin and Lincoln, who have written a series of influential handbooks on qualitative methods (1994; Denzin and Lincoln 2003 ; 2005 ), citing Nelson et al. (1992:4), argue that because qualitative research is “interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, and sometimes counterdisciplinary” it is difficult to derive one single definition of it (Jovanović 2011 :3). According to them, in fact, “the field” is “many things at the same time,” involving contradictions, tensions over its focus, methods, and how to derive interpretations and findings ( 2003 : 11). Similarly, others, such as Flick ( 2007 :ix–x) contend that agreeing on an accepted definition has increasingly become problematic, and that qualitative research has possibly matured different identities. However, Best holds that “the proliferation of many sorts of activities under the label of qualitative sociology threatens to confuse our discussions” ( 2004 :54). Atkinson’s position is more definite: “the current state of qualitative research and research methods is confused” ( 2005 :3–4).

Qualitative research is about interpretation (Blumer 1969 ; Strauss and Corbin 1998 ; Denzin and Lincoln 2003 ), or Verstehen [understanding] (Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias 1996 ). It is “multi-method,” involving the collection and use of a variety of empirical materials (Denzin and Lincoln 1998; Silverman 2013 ) and approaches (Silverman 2005 ; Flick 2007 ). It focuses not only on the objective nature of behavior but also on its subjective meanings: individuals’ own accounts of their attitudes, motivations, behavior (McIntyre 2005 :127; Creswell 2009 ), events and situations (Bryman 1989) – what people say and do in specific places and institutions (Goodwin and Horowitz 2002 :35–36) in social and temporal contexts (Morrill and Fine 1997). For this reason, following Weber ([1921-22] 1978), it can be described as an interpretative science (McIntyre 2005 :127). But could quantitative research also be concerned with these questions? Also, as pointed out below, does all qualitative research focus on subjective meaning, as some scholars suggest?

Others also distinguish qualitative research by claiming that it collects data using a naturalistic approach (Denzin and Lincoln 2005 :2; Creswell 2009 ), focusing on the meaning actors ascribe to their actions. But again, does all qualitative research need to be collected in situ? And does qualitative research have to be inherently concerned with meaning? Flick ( 2007 ), referring to Denzin and Lincoln ( 2005 ), mentions conversation analysis as an example of qualitative research that is not concerned with the meanings people bring to a situation, but rather with the formal organization of talk. Still others, such as Ragin ( 1994 :85), note that qualitative research is often (especially early on in the project, we would add) less structured than other kinds of social research – a characteristic connected to its flexibility and that can lead both to potentially better, but also worse results. But is this not a feature of this type of research, rather than a defining description of its essence? Wouldn’t this comment also apply, albeit to varying degrees, to quantitative research?

In addition, Strauss ( 2003 ), along with others, such as Alvesson and Kärreman ( 2011 :10–76), argue that qualitative researchers struggle to capture and represent complex phenomena partially because they tend to collect a large amount of data. While his analysis is correct at some points – “It is necessary to do detailed, intensive, microscopic examination of the data in order to bring out the amazing complexity of what lies in, behind, and beyond those data” (Strauss 2003 :10) – much of his analysis concerns the supposed focus of qualitative research and its challenges, rather than exactly what it is about. But even in this instance we would make a weak case arguing that these are strictly the defining features of qualitative research. Some researchers seem to focus on the approach or the methods used, or even on the way material is analyzed. Several researchers stress the naturalistic assumption of investigating the world, suggesting that meaning and interpretation appear to be a core matter of qualitative research.

We can also see that in this category there is no consensus about specific qualitative methods nor about qualitative data. Many emphasize interpretation, but quantitative research, too, involves interpretation; the results of a regression analysis, for example, certainly have to be interpreted, and the form of meta-analysis that factor analysis provides indeed requires interpretation However, there is no interpretation of quantitative raw data, i.e., numbers in tables. One common thread is that qualitative researchers have to get to grips with their data in order to understand what is being studied in great detail, irrespective of the type of empirical material that is being analyzed. This observation is connected to the fact that qualitative researchers routinely make several adjustments of focus and research design as their studies progress, in many cases until the very end of the project (Kalof et al. 2008 ). If you, like Becker, do not start out with a detailed theory, adjustments such as the emergence and refinement of research questions will occur during the research process. We have thus found a number of useful reflections about qualitative research scattered across different sources, but none of them effectively describe the defining characteristics of this approach.

Although qualitative research does not appear to be defined in terms of a specific method, it is certainly common that fieldwork, i.e., research that entails that the researcher spends considerable time in the field that is studied and use the knowledge gained as data, is seen as emblematic of or even identical to qualitative research. But because we understand that fieldwork tends to focus primarily on the collection and analysis of qualitative data, we expected to find within it discussions on the meaning of “qualitative.” But, again, this was not the case.

Instead, we found material on the history of this approach (for example, Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias 1996 ; Atkinson et al. 2001), including how it has changed; for example, by adopting a more self-reflexive practice (Heyl 2001), as well as the different nomenclature that has been adopted, such as fieldwork, ethnography, qualitative research, naturalistic research, participant observation and so on (for example, Lofland et al. 2006 ; Gans 1999 ).

We retrieved definitions of ethnography, such as “the study of people acting in the natural courses of their daily lives,” involving a “resocialization of the researcher” (Emerson 1988 :1) through intense immersion in others’ social worlds (see also examples in Hammersley 2018 ). This may be accomplished by direct observation and also participation (Neuman 2007 :276), although others, such as Denzin ( 1970 :185), have long recognized other types of observation, including non-participant (“fly on the wall”). In this category we have also isolated claims and opposing views, arguing that this type of research is distinguished primarily by where it is conducted (natural settings) (Hughes 1971:496), and how it is carried out (a variety of methods are applied) or, for some most importantly, by involving an active, empathetic immersion in those being studied (Emerson 1988 :2). We also retrieved descriptions of the goals it attends in relation to how it is taught (understanding subjective meanings of the people studied, primarily develop theory, or contribute to social change) (see for example, Corte and Irwin 2017 ; Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias 1996 :281; Trier-Bieniek 2012 :639) by collecting the richest possible data (Lofland et al. 2006 ) to derive “thick descriptions” (Geertz 1973 ), and/or to aim at theoretical statements of general scope and applicability (for example, Emerson 1988 ; Fine 2003 ). We have identified guidelines on how to evaluate it (for example Becker 1996 ; Lamont 2004 ) and have retrieved instructions on how it should be conducted (for example, Lofland et al. 2006 ). For instance, analysis should take place while the data gathering unfolds (Emerson 1988 ; Hammersley and Atkinson 2007 ; Lofland et al. 2006 ), observations should be of long duration (Becker 1970 :54; Goffman 1989 ), and data should be of high quantity (Becker 1970 :52–53), as well as other questionable distinctions between fieldwork and other methods:

Field studies differ from other methods of research in that the researcher performs the task of selecting topics, decides what questions to ask, and forges interest in the course of the research itself . This is in sharp contrast to many ‘theory-driven’ and ‘hypothesis-testing’ methods. (Lofland and Lofland 1995 :5)

But could not, for example, a strictly interview-based study be carried out with the same amount of flexibility, such as sequential interviewing (for example, Small 2009 )? Once again, are quantitative approaches really as inflexible as some qualitative researchers think? Moreover, this category stresses the role of the actors’ meaning, which requires knowledge and close interaction with people, their practices and their lifeworld.

It is clear that field studies – which are seen by some as the “gold standard” of qualitative research – are nonetheless only one way of doing qualitative research. There are other methods, but it is not clear why some are more qualitative than others, or why they are better or worse. Fieldwork is characterized by interaction with the field (the material) and understanding of the phenomenon that is being studied. In Becker’s case, he had general experience from fields in which marihuana was used, based on which he did interviews with actual users in several fields.

Grounded Theory

Another major category we identified in our sample is Grounded Theory. We found descriptions of it most clearly in Glaser and Strauss’ ([1967] 2010 ) original articulation, Strauss and Corbin ( 1998 ) and Charmaz ( 2006 ), as well as many other accounts of what it is for: generating and testing theory (Strauss 2003 :xi). We identified explanations of how this task can be accomplished – such as through two main procedures: constant comparison and theoretical sampling (Emerson 1998:96), and how using it has helped researchers to “think differently” (for example, Strauss and Corbin 1998 :1). We also read descriptions of its main traits, what it entails and fosters – for instance, an exceptional flexibility, an inductive approach (Strauss and Corbin 1998 :31–33; 1990; Esterberg 2002 :7), an ability to step back and critically analyze situations, recognize tendencies towards bias, think abstractly and be open to criticism, enhance sensitivity towards the words and actions of respondents, and develop a sense of absorption and devotion to the research process (Strauss and Corbin 1998 :5–6). Accordingly, we identified discussions of the value of triangulating different methods (both using and not using grounded theory), including quantitative ones, and theories to achieve theoretical development (most comprehensively in Denzin 1970 ; Strauss and Corbin 1998 ; Timmermans and Tavory 2012 ). We have also located arguments about how its practice helps to systematize data collection, analysis and presentation of results (Glaser and Strauss [1967] 2010 :16).

Grounded theory offers a systematic approach which requires researchers to get close to the field; closeness is a requirement of identifying questions and developing new concepts or making further distinctions with regard to old concepts. In contrast to other qualitative approaches, grounded theory emphasizes the detailed coding process, and the numerous fine-tuned distinctions that the researcher makes during the process. Within this category, too, we could not find a satisfying discussion of the meaning of qualitative research.

Defining Qualitative Research