Search form

- Table of Contents

- Troubleshooting Guide

- A Model for Getting Started

- Justice Action Toolkit

- Best Change Processes

- Databases of Best Practices

- Online Courses

- Ask an Advisor

- Subscribe to eNewsletter

- Community Stories

- YouTube Channel

- About the Tool Box

- How to Use the Tool Box

- Privacy Statement

- Workstation/Check Box Sign-In

- Online Training Courses

- Capacity Building Training

- Training Curriculum - Order Now

- Community Check Box Evaluation System

- Build Your Toolbox

- Facilitation of Community Processes

- Community Health Assessment and Planning

- Section 10. Understanding Culture, Social Organization, and Leadership to Enhance Engagement

Chapter 27 Sections

- Section 1. Understanding Culture and Diversity in Building Communities

- Section 2. Building Relationships with People from Different Cultures

- Section 3. Healing from the Effects of Internalized Oppression

- Section 4. Strategies and Activities for Reducing Racial Prejudice and Racism

- Section 5. Learning to be an Ally for People from Diverse Groups and Backgrounds

- Section 6. Creating Opportunities for Members of Groups to Identify Their Similarities, Differences, and Assets

- Section 7. Building Culturally Competent Organizations

- Section 8. Multicultural Collaboration

- Section 9. Transforming Conflicts in Diverse Communities

- Section 11. Building Inclusive Communities

|

The Tool Box needs your help Your contribution can help change lives.

|

- Main Section

| Learn how to understand people's culture, community and leadership to enhance engagement. |

In order to work effectively in a culturally and ethnically diverse community, a community builder needs to first understand how each racial and ethnic group in that community is organized in order to support its members. It is not uncommon to hear a community leader, a funder, a political representative, or a service provider say, "We were not able to engage that group over there because they are not organized. They have no leaders. We need to organize them first." This statement is not always accurate; most groups have their own network of relationships and hierarchy of leaders that they tap into for mutual support. These networks or leaders may not be housed in a physical location or building that is obvious to people outside of the group. They may not even have a label or a title. There is an unspoken understanding in some groups about when and whom they should turn to among their members for advice, guidance, and blessing. Once a community builder understands the social organization of the group, it will become easier to identify the most appropriate leaders, help build bridges, and work across multiple groups in a diverse community.

What do we mean by "social organization?" Social organization refers to the network of relationships in a group and how they interconnect. This network of relationships helps members of a group stay connected to one another in order to maintain a sense of community within a group. The social organization of a group is influenced by culture and other factors.

Within the social organization of a group of people, there are leaders. Who are leaders? Leaders are individuals who have followers, a constituency, or simply a group of people whom they can influence. A community builder needs to know who the leaders are in a group in order to get support for his community building work.

In this section, you will learn more about the social organization and leadership of different cultural and ethnic groups. The material covered in this section focuses primarily on African Americans and immigrants for two reasons:

- Tensions tend to occur among groups that are competing for resources that are already limited and not always accessible to them; and

- Most of the struggles facing community builders and other individuals have been with recent immigrants whose culture, institutions, and traditions are still unfamiliar to mainstream groups.

As recent immigrant groups integrate into their new society, their social organization and leadership structures transform to become more similar to those of mainstream groups. This process could take decades and generations; all the more reason why it is important for community builders to understand the social organization and leadership structure of the new arrivals and to build on their values and strengths. While some traditional social structures may prevail, others may adapt to those of the mainstream culture.

Take a moment and think about the most recent group of newcomers to your community. Who are their leaders? Where do their members go to for help?

Think about the group you belong to. Who are the leaders? Whom do you go to for help? How is your group organized to communicate among its members?

Obviously there are too many groups in this world to include in this section. We will try to share information about as many groups as we can. While the section may not inform you about the social organization and leadership of groups other than the ones described here, we hope it will help you understand enough about the influence of culture on social organization and leadership to ask the right questions of any group.

How do culture and other factors affect the social organization of a community?

There are many definitions of culture. Culture typically refers to a set of symbols, rituals, values, and beliefs that make one group different from another. Culture is learned and shared with people who live or lived in the same social environment for a long time. Culture is captured in many, many ways -- in the way members of a group greet and interact with one another, in legends and children's stories, in the way food is prepared and used, in the way people pray, and so on. Since it is difficult and not always appropriate to change someone's culture, how do you then use culture as a positive force to aid community building?

In the Chinese community:

The Chinese community is the largest and the fastest growing group among Asian and Pacific Islander populations.

Keep in mind: The Chinese community forms a very heterogeneous group that includes people from mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and other parts of South East Asia. There are many dialects spoken among Chinese people and not all Chinese persons can understand one another's dialects. Therefore, make sure you know which Chinese dialect requires translation if you have to provide translation services.

The Chinese culture places heavy emphasis on taking care of one's family. Chinese people believe that taking care of their families is a contribution to civic welfare, because healthy families lead to a healthy society. This belief is based on Confucian values, which emphasize filial piety, or a respect for family. The concept of filial piety is instilled in Chinese children from a very young age. In other words, familial relationships form the basis for Chinese social organization and behavior.

Chinese parents place a heavy emphasis on their children and their ability to become successful. Confucian values include reaching for perfection, and perfection can be achieved through education. This is why Chinese parents invest a lot of resources in making sure that their children excel academically.

How does this value affect the way Chinese communities are organized and participate in their communities?

In Chinese communities in America and other countries, it is common to find local associations or huiguan formed by members from the same province or village in China and Taiwan. These local associations provide capital to help their members start businesses. They also perform charitable and social functions and provide protection for their members. These associations play a key role in community building efforts, particularly in Chinatowns. They are formed because of the Chinese emphasis on the importance of family; in China, you consider the people from the same province or village as your extended family. Therefore, in order to engage any Chinese community in a community building effort, it will be useful to identify and involve the leaders of these associations. How do you find out about huiguans? Look in the Chinese newspapers (if you don't read Mandarin, ask someone who does); attend Chinese events and find out who sponsored them; walk around Chinatown (if there is one in your community or city) and look at the advertisements posted in grocery stores, restaurants, and shops.

Education also becomes an issue that can be used to mobilize the Chinese community. With the heavy emphasis on academic excellence, it is more likely that you can convince Chinese parents to show up for a meeting about the quality of their children's education than for a meeting about a recreational center for the community. This means that you should look for ways to link education to the issue that you are trying to address in your community building effort.

Recent Chinese immigrants fear very much that their children or the next generation will lose touch with their culture. Hence, they do whatever they can to teach their children how to speak and write Mandarin or other Chinese dialects. This desire has led to the creation of many Chinese schools in areas that have large populations of Chinese immigrants. Sometimes, these schools have their own buildings; at other times, they are conducted on the weekends in a public school. These schools can play a critical role in reaching out to the Chinese community.

In the African American community:

A group's history of oppression and survival also affects the way it is organized. The networks and organizations that form to protect the rights of their members influence the way in which members of the group organize for self-help. Enslaved Africans, who were "Christianized" by their European enslavers, used spiritual symbolism to preach freedom and to give their people hope and strength. As a result, in the African American culture, religious institutions, primarily Christian (e.g., the African Methodist Episcopal church), have functioned as mutual-aid societies, political forces, and education centers. While Christian churches are predominant among African Americans, the existence and leadership of the Nation of Islam and Muslim leaders in organizing the African American community should also be considered. Today, African American spiritual leaders are among the most influential leaders in African American communities. Therefore, in order to engage any African American community in a community building effort, it will be important to identify and involve that community's spiritual leaders.

How does this value affect the way African American communities are organized and participate in their communities?

In most African American and Black communities, it is common to find one or more churches that are the focal point for social, economic, and political activities. Spirituality, especially Christianity, provides an effective bridge among African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans.The Allied Communities of Tarrant (ACT) in Fort Worth, Texas, is an example of using spirituality to organize a coalition among leaders from these three communities. African American Baptist ministers, European American Lutheran and Disciples of Christ ministers, as well as Latino and European American Catholic priests who were connected to one another through their spiritual interests decided to work across racial lines in order to improve the quality of life for their members. With the help of the Industrial Areas Foundations (IAF), they struggled to identify their commonalties, differences -- especially related to race -- power, and assets. Eventually, they established ACT and took on the issue of school reform, starting with the African American community. African American church leaders came together to develop initiatives within their own churches to empower and support parents to participate in the effort.

In the Central American community:

Many Central Americans fled the poverty and oppression in their countries to seek a more secure and better life in a new place. As one person settled in the new location and saved enough money, he or she would help family members to migrate. Because of the informal and extended family networks that are part of the Central American culture, natural support systems develop to assist new arrivals.

Aside from culture, what other factors affect the social organization of Central Americans?

The close proximity of Central America to the United States (compared to other continents) plays a role in the social organization of Central Americans. Regional associations that are typically named after a town, a city, or a region in Central America emerge in the immigrants' new geographic setting to provide support in cultural identification, security, and maintenance of connection with their families and friends who remained behind in Central America. These associations are usually affiliated with religious groups, soccer clubs, political parties, revolutionary movements, or social service organizations in Central America. Because of this form of social organization, the Salvadoran community in the United States has been able to raise a large amount of funds to assist earthquake and hurricane victims in their homeland.

How can you build on these forms of social organization to engage the Central American community?

Soccer ("football") is a favorite activity among Central Americans. It is not unusual to see adults and children from Central American countries playing soccer in public parks and school compounds. Central American countries are very proud of their national soccer teams. It's similar to the way American football or baseball is valued in the United States, but it is more than just a game for immigrants. Soccer becomes an avenue for meeting other people from the same country or region and forming a social support network. If you are a community builder who is trying to bring various Central American groups together, try using soccer as the common ground!

The Catholic Church is also a key institution that holds members of the Central American communities together. Even in Central America, the church has played a leading role in political advocacy and organizing. In the immigrants' new country, the church continues to play this role, in addition to providing services and social support, and maintaining a line of communication between the immigrants and their families and friends in Central America. Build on the strength and influence of the church to bring credibility to your community building effort and to reach out to Central American communities.

In the Caribbean community:

Migration patterns can provide important information about a group of people. Typically, most immigrants come because they already have a relative or a friend that lives in the United States. They move in with the relatives or friends who also help them find their first job. In the Caribbean culture, there is a tradition of helping the new arrivals through rotating credit associations or saving clubs, otherwise known as susus. According to this tradition, a group of people pools their money and then loans it to someone who needs it. The borrower pays back the loan over a period of time and commits to stay in the susu until the payment is complete.

How can you build on these forms of social organization to engage the Caribbean community?

If your community building effort focuses on economic development, then it is important for you to identify the person who manages the susu. You could ask a Caribbean business or a mutual aid society for Caribbean immigrants for the contact person.

What do all these organizations and institutions have in common?

They support the social organization of a community. Depending on the community's culture and the context that the community has to survive in and adapt to, they all serve different functions.

How do culture and other factors affect the leadership of a community?

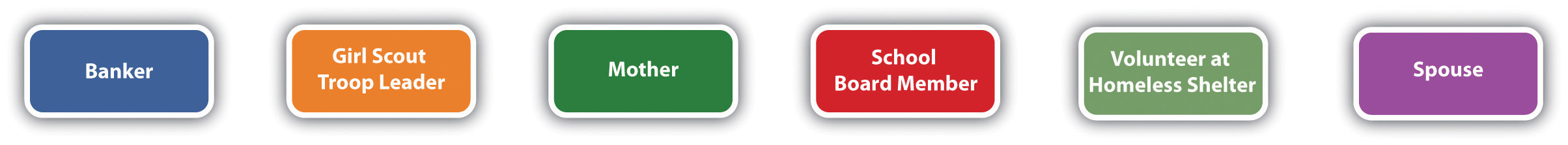

The information above showed that culture and other factors (social, economic, historical, and political) have an effect on the way a community organizes itself for self-help and support. The same can be said about leadership. There are different levels and types of leaders that support the social organization of a community. Sometimes, we make the mistake of assuming that there is only one leader in a community or that a leader has to look a certain way. Just as we respect and value the cultural diversity of communities, we have to respect and value the diversity of leadership.

What qualities do you think a leader should have?

In every ethnic or cultural group there are different individuals who are regarded as leaders by members of the group. Every leader has a place and a role in his or her community. Leaders can be categorized by type (e.g., political, religious, social), by issue (e.g., health, education, economic development), by rank (e.g., president, vice president), by place (e.g., neighborhood block, county, city, state, country), by age (e.g., elderly, youth), and so on.

Let's use the same communities described before. In Chinese communities, the leader is typically the head of the family. If family refers to a grandfather, father, mother, sons and daughters, and grandchildren, then the leader is the grandfather. If family refers to the congregation of a church, the leader is the pastor. If family refers to a clan, the leader is the President of the clan's association (or hui guan ).

In African American communities, the leader is typically a spiritual leader. A leader can also be someone who is successful in overcoming the barriers of institutionalized racism and provide opportunities for other African Americans to be treated equally by others in the mainstream society (e.g., a business person, an educator, or an elected official).

In Central American communities, the leader is also typically a spiritual leader. It can also be the coach of a soccer team or the president of an association that links a city in Central America with one in another country.

What do all these leaders have in common?

They provide guidance, they have influence over others, others respect them, they respond to the needs of others, and they put the welfare of others above their own. Every leader serves a specific function within the social organization of a community; however, the same type of leader in one community does not necessarily have the same role in another community. For example, a spiritual leader in a Chinese community is not regarded as a political leader, as he might be in the African American community.

What did you learn from the above information and examples?

How can you, the community builder, learn about the social organization of other ethnic and cultural groups?

- Go into the process with an open mind.

- Don't assume that the same leader, organization, or institution serves the same function across groups.

- Keep in mind that the social organization and leadership of a group is influenced by its culture, history, reasons for migration, geographic proximity to its homeland, economic success, intra-group tensions, and the way it fits into the political and social context of its new and surrounding society.

- Look for the formal and informal networks.

- Interview members of a group and ask where and whom they go to for help or when they have a problem.

Keep in mind : Among different groups, the church has different functions. For example, Korean and Chinese churches do not have strong political functions compared to Latino or African American churches. Korean churches serve their members socially by providing a structure and process for fellowship and sense of belonging, maintenance of ethnic identity and native traditions, social services, and social status. Korean pastors consider their churches as sanctuaries for their members and do not wish to burden them with messages related to political or economic issues. Instead, they focus on providing counseling and educational services to Korean families as well as clerical and lay positions for church members. Korean immigrants hold these positions in high regard.

What are examples of social networks and ethnic organizations that a community builder can use to learn about the social organization of a group, to identify and engage its leaders?

The section before emphasized the importance of learning about the social organization and leadership of various groups in a community so that you can tap into the appropriate resources and assets of each group. You understand that different organizations, institutions, and leaders play different roles in each group. Where do you start? How do you go about getting that knowledge?

Identify natural gathering points and traditions related to social gatherings . Tapping into natural gathering points and traditions related to social gatherings are excellent ways to identify and engage the local leaders and build community relationships. For example, in the Filipino community, tea time is a common practice due to historical European influence. Therefore, "tea meetings" in restaurants are useful for attracting community members to discuss issues and to ask how to involve them in community building efforts. Ethnic grocery stores also play a major role in distributing information to large numbers of people. These stores frequently have bulletin boards where notices are posted about all kinds of activities in that community. In addition, cultural celebrations draw large crowds and provide an effective avenue for outreach. Attend these gatherings. Find out who sponsored and organized them. Talk to the people who attend them. Ask them how they found out about the gatherings. Ask them who you should contact if you wanted more information about the gatherings.

Build on the informal networks of women . One way to engage a racial, ethnic, or cultural group is to tap into the informal networks of women. Go to places where women tend to go, such as the grocery store, the school their children attend, and the hair salon. Ask the parent coordinator at the school if you could speak to some of the mothers. It is likely that you will be able to identify one or more women who are respected by their peers and to whom everyone tells their problems.

Mujeres Unidas y Activas, a women's organization was born when a project that brought together women from various cultures showed that the women experienced similar concerns (e.g., public health issues related to their housing conditions, domestic abuse, concern for their children's education). After the project was completed, the women felt the need to continue to meet informally for mutual support. The network eventually became an organization that is involved in addressing issues that concern women.

Gain entry and credibility through traditional leadership structures . The approach is applicable to any group with a traditional leadership structure serving as a gatekeeper to its members. If you already understand the traditional leadership structure, use it to get support for what you are doing.

Keep in mind: Engaging the traditional leadership structures in some communities may perpetuate class, gender, or other differences. For example, the traditional leadership structure in Middle Eastern communities tends to be patriarchal. By choosing to engage the male leaders as a way to involve the larger community, you may be reinforcing that culture's treatment of women. Community builders must always be aware of the extent to which they might encounter and be required to address cultural traditions that reinforce inequities. At the same time, you have to be aware that by bypassing or trying to expand the traditional power structure, you may be sacrificing credibility with the community or, at the very least, losing some of the most powerful community leaders. If you think there's a need to change some aspects of the culture in a community that is not your own, it makes much more sense to work through members of that community, rather than challenging the leaders directly. Over time, you may be able to convince them, but you have to approach them in a way that doesn't rob them of dignity or belittle customs that have been taken for granted for generations.

Identify and work with the "bridge generation." Young people are the ideal bridge in most communities, especially in immigrant communities, because they are raised in traditional ways but schooled in the ways of the dominant culture. Young people typically accompany their parents to the clinic, school, faith institution, and many other places. Sometimes, they translate for their non-English speaking parents. Therefore, they are likely to know where their parents go for help and who organizes the events in their community.

Ask national organizations that serve and advocate on behalf of different racial, ethnic, and cultural groups for assistance.

National organizations with special concerns have become powerful forces in linking immigrants to mainstream American institutions. Examples include the American Physicians of Indian Origin, Japanese American Citizens League, National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials Education Fund, Mexican-American Legal Defense Fund, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the National Asian Pacific Center on Aging. These organizations play a more extensive role than faith-based institutions, community centers, or cultural programs do in bridging immigrant traditions with mainstream American institutions and values. As a community builder, you might want to engage these organizations if your community building effort is focused on advocacy for a specific issue.

Take advantage of programs that serve large numbers of immigrants . English as a Second or Other Language classes (ESOL) and citizenship workshops often attract large numbers of immigrants, particularly recent newcomers, and provide another way to reach them. Many of these programs are conducted on weekends and evenings.Even though their primary intent is to teach new immigrants how to function biculturally, they can also become social support systems. If you want to talk to or engage large numbers of people, try the ESOL classes and citizenship workshops.

Take advantage of ethnic neighborhoods . In places like Chinatown, Koreatown, and Little India, there are many businesses and organizations that serve the needs of the residents. Go to these neighborhoods, walk through them, and look for community centers, mutual aid organizations, and other businesses that advertise programs or attract larger numbers of people.

How else can you find out more about a community?

- Find an informant from that community and utilize his or her contacts to guide you toward other community members and leaders.

- Spend time at places that are frequented by members of the target group and talk to people there.

- Scan the neighborhood and/or ethnic newspaper for articles about major events and activities in a community and the organizations that sponsor them.

- Contact the editor of the newspaper to ask his/her opinion about who the leaders are in a community.

- Go to the ethnic grocery or convenience stores to review the announcements about events and other activities and the organizations that sponsor them.

- Look in the phone directory or search the Internet for a list of organizations that support a communinty.

Keep in mind: Relationship building and trust building are fundamental parts of the work, especially in cultures that may be less familiar to you and/or those that have experienced racism and other forms of oppression. Getting to know people and gaining their trust takes time, patience, and flexibility.

What are the challenges that you should be aware of and how can the challenges be overcome?

You must remember NOT to make any promises to the leader about anything until you have had the opportunity to speak to as many individuals as possible and determined the most appropriate leader to involve in the effort. Also, don't get drawn into the discussions about the merits or weaknesses of other leaders. Don't share information about what other leaders might or might not have said already. Just listen.

You have to consider several factors before you begin to engage any of the leaders in the community. How were previous community building efforts, if any, initiated in the past? Who initiated them? Was the effort effective? If not, what happened? This knowledge would help you understand the attitudes toward you and the community building you are involved in. You might also want to consider establishing an advisory group made up of leaders from different groups to help announce and plan the effort

Don't be afraid to acknowledge your ignorance. Display humility, respect the influence of each leader, and ask to be educated. You might consider starting off the conversation with a statement such as, "I know very little about your culture, but I understand that it is important to learn about it so that the community building effort I'm involved in can build on your cultural strengths and will not make assumptions about your group's needs. I really appreciate the time you are taking to talk to me and I look forward to learning from you."

- When working in a diverse community that is made up of two or more racial, ethnic, or cultural groups, it is unlikely that any one community builder will have all the linguistic skills and cultural knowledge needed to relate to all the groups. At the same time, you, the community builder may be a member of one of the groups. You must be aware of the advantages and disadvantages of working with a group of people that share your culture (e.g., a Chinese community builder working in a Chinese community). You have the advantage of already knowing the culture and the language. A disadvantage is that the informant may expect you to play favoritism because you "owe" your community.

A team made up of community builders from different racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds would allow for the ability to relate to a wide range of experiences, to speak multiple languages, and to empathize with the variety of challenges that community leaders face. It would also help to avoid some of the expectations and misperceptions about whom you represent and who would benefit from your effort. Furthermore, working in diverse community building teams set an example for the leaders of a group and across groups.

Maintain a neutral perspective and don't get drawn into discussions about other leaders. Reach out to as many types of leaders as possible. Explain that you are just in the information gathering stage; however, make note of the tensions so that you can be prepared to facilitate any potential conflicts in the future if those leaders happen to participate more extensively in the community building effort.

You could identify outside resources and expertise to help them or you could serve as a coach to the local group. This process itself can be a useful community building strategy.

Online Resources

Brown University Training Materials : Cultural Competence and Community Studies: Concepts and Practices for Cultural Competence . The Northeast Education Partnership provides online access to PowerPoint training slides on topics in research ethics and cultural competence in environmental research. These have been created for professionals/students in environmental sciences, health, and policy; and community-based research.

Chapter 8: Respect for Diversity in the "Introduction to Community Psychology" explains cultural humility as an approach to diversity, the dimensions of diversity, the complexity of identity, and important cultural considerations.

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in Nonprofit Organizations by Sean Thomas-Breitfeld and Frances Kunreuther, from the International Encyclopedia of Civil Society.

Study, Discussion and Action on Issues of Race, Racism and Inclusion - a partial list of resources utilized and prepared by Yusef Mgeni.

Print Resources

Casinitz, P. (1992). Caribbean New York. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Cordoba, C. (1995). Organizing with Central-American immigrants in the United States . In F.Rivera & J.Erlich (Eds.), Community organizing in a diverse society (pp. 177-196). Needham Heights, MA: Simon & Schuster.

Feagin, J. & Feagin, C. (1999). Racial and ethnic relations . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Simon & Schuster.

Hamilton, N. & Chinchilla, N.S. (2001). Seeking Community In A Global City . Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Hofstede, G. (1997). Culture and organizations . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Karpathakis, A. (1999). Home society politics and immigrant political incorporations: The case of Greek immigrants in New York City . International Migration Review, 31 (4), pp. 55-78.

Lee, K. (2002). Lessons learned about civic participation among immigrants (draft). Report to the Community Foundation for the National Capital Region, Washington, DC.

Lee, P. (1995). Organizing in the Chinese-American community: Issues, strategies, and alternatives . In F.Rivera & J.Erlich (Eds.), Community organizing in a diverse society (pp. 113-142). Needham Heights, MA: Simon & Schuster.

Leonard, K. (1997). The South Asian Americans. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Min, P.G. (2000). The structure and social functions of Korean immigrant churches in the United States. In Zhou, M., & Gatewood, J. (eds.). Contemporary Asian American: A Multidisplinary Reader. New York: New York University Press.

Perkins, J. (Ed.). (1995). Restoring at-risk communities . Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books.

Warren, M. (2001). Dry bones ratting. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 6. Groups and Organizations

Learning objectives.

6.1. Types of Groups

- Understand primary and secondary groups as two key sociological groups

- Recognize in-groups and out-groups as subtypes of primary and secondary groups

- Define reference groups

6.2. Groups and Networks

- Determine the distinction between groups, social networks, and formal organizations

- Analyze the dynamics of dyads, triads, and larger social networks

- Distinguish between different styles of leadership

- Explain how conformity is impacted by groups

- Understand why groups and networks are more than the sum of their parts

6.3. Formal Organizations

- Understand the different types of formal organizations

- Categorize the characteristics of bureaucracies

- Analyze the opposing tendencies of bureaucracy toward efficiency and inefficiency

- Identify the concepts of the McDonaldization of society and the McJob as aspects of the process of rationalization

Introduction to Groups and Organizations

The punk band NOFX is playing outside in Los Angeles. The music is loud, the crowd pumped up and excited. But neither the lyrics nor the people in the audience are quite what you might expect. Mixed in with the punks and young rebel students are members of local unions, from well-dressed teachers to more grizzled labour leaders. The lyrics are not published anywhere but are available on YouTube: “We’re here to represent/The 99 percent/Occupy, occupy, occupy.” The song: “Wouldn’t It Be Nice If Every Movement Had a Theme Song” (Cabrel 2011).

At an Occupy camp in New York, roughly three dozen members of the Facilitation Working Group, a part of the General Assembly, take a steady stream of visitors with requests at their unofficial headquarters. One person wants a grant for $1,500 to make herbal medications available to those staying at the park. Another wants to present Native American peace principles derived from the Iroquois Confederacy. Yet another has a spreadsheet that he wants used as an evaluation tool for the facilitators. A group of women press for more inclusive language to be used in the “Declaration of the Occupation” document so that racial and women’s concerns are recognized as central to the movement.

In Victoria, B.C., a tent community springs up in Centennial Square outside city hall, just like tent cities in other parts of the country. Through the “horizontal decision-making process” of daily general assemblies, the community decides to change its name from Occupy Victoria to the People’s Assembly of Victoria because of the negative colonial connotations of the word “occupy” for aboriginal members of the group. As the tent cities of the Occupy movement begin to be dismantled, forcibly in some cases, a separate movement, Idle No More, emerges to advocate for aboriginal justice.

Numerous groups make up the Occupy movement, yet there is no central movement leader. What makes a group something more than just a collection of people? How are leadership functions and styles established in a group dynamic?

Most people have a sense of what it means to be part of some kind of a group, whether it is a social movement, sports team, school club, or family. Groups connect us to others through commonalities of geography, interests, race, religion, and activities. But for the groups of people protesting from New York City to Victoria, B.C., and in the hundreds of cities in between, their connection within the Occupy Wall Street movement is harder to define. What unites these people? Are homeless people truly aligned with law school students? Do aboriginal people genuinely feel for the environmental protests against pipelines and fish farming?

Groups are prevalent in our social lives and provide a significant way to understand and define ourselves—both through groups we feel a connection to and those we do not. Groups also play an important role in society. As enduring social units, they help foster shared value systems and are key to the structure of society as we know it. There are four pri mary sociological perspectives for studying groups: functionalist, critical, feminist, and symbolic interactionist. We can look at the Occupy movement through the lenses of these methods to better understand the roles and challenges that groups offer.

The functionalist perspective is a big-picture, macro-level view that looks at how different aspects of society are intertwined. This perspective is based on the idea that society is a well-balanced system with all parts necessary to the whole. It studies the functions these parts play in the reproduction of the whole. In the case of the Occupy movement, a functionalist might look at what macro-level needs the movement serves. Structural functionalism recognizes that there are tensions or conflicts between different structural elements of the system. The huge inequalities generated by the economic system might function positively as part of the incentive needed for people to commit themselves to risky economic ventures, but they conflict with the normative structure of the political decision-making system based on equality and democratic principles. The Occupy movement forces both haves and have-nots to pay attention to the imbalances between the economic and political systems. Occupy emerges as an expression of the disjunction between these two systems and functions as a means of initiating a resolution of the issues.

The critical perspective is another macroanalytical view, one that focuses on the genesis and growth of inequality. A critical theorist studying the Occupy movement might look at how business interests have manipulated the system to reduce financial regulations and corporate taxes over the last 30 years. In particular, they would be interested in how these led to the financial crisis of 2008 and the increasing inequality we see today. The slogan, “We are the 99%,” emblematic of the Occupy movement, refers to the massive redistribution of wealth from the middle class to the upper class. Even when the mismanagement of the corporate elite (i.e., the “1%”) had threatened the stability of people’s livelihoods and the entire global economy in the financial meltdown of 2008, and even when their corporations and financial institutions were receiving bailouts from the American and Canadian governments, their personal income, bonuses, and overall share of social wealth increased.

Feminist analysis of the Occupy movement would be interested in the connection between contemporary capitalism and patriarchy. Why are women the poorest of the poor? They would also be interested in the type of organizational models used by the Occupy movement to understand and address the resulting issues of power structure and economic injustice. The consciousness-raising techniques and non-hierarchical decision-making processes developed by feminists in the 1960s and 1970s were, in fact, incorporated into the daily political activities of the Occupy movement in order to extend the critique of corporate greed and financial institutions to largely invisible issues of privilege and daily, personal struggle. Occupy Montreal adopted the concept of stepping back or “progressive stack” in their meetings. Men and other dominant movement figures were encouraged to step back from monopolizing the conversation so that a diversity of opinions and experiences could be heard. “We are not here to reproduce the same monopolization of voice and power as the ‘1%,’ we are here to diversify spaces for radical inclusion” (Boler 2012).

A fourth perspective is the symbolic interactionist perspective. This method of analyzing groups takes a micro-level view. Instead of studying the big picture, these researchers look at the day-to-day interactions of groups. Studying these details, the interactionist looks at issues like leadership style, communicative interactions, and group dynamics. In the case of the Occupy movement, interactionists might ask, “How does a non-hierarchical organization work?”; “How is the social order of a diverse group maintained when there are no formal regulations in place?”; “What are the implicit or tacit rules such groups rely on?”; “How do members come to share a common set of meanings concerning what the movement is about?”

At one point during the occupation of Wall Street, speakers like Slovenian social critic and philosopher Slavoj Zizek were obliged to abandon the use of microphones and amplification to comply with noise bylaws. They gave their speeches one line at a time and the people within earshot repeated the lines so that those further away could hear. The symbolic interactionist would be interested in examining how this communicational format, despite its cumbersome nature, could come to be an expression of group solidarity.

6.1. Types of Groups

Most of us feel comfortable using the word “group” without giving it much thought. But what does it mean to be part of a group? The concept of a group is central to much of how we think about society and human interaction. As Georg Simmel (1858–1915) put it, “[s]ociety exists where a number of individuals enter into interaction” (1908). Society exists in groups. For Simmel, society did not exist otherwise. What fascinated him was the way in which people mutually attune to one another to create relatively enduring forms. In a group, individuals behave differently than they would if they were alone. They conform, they resist, they forge alliances, they cooperate, they betray, they organize, they defer gratification, they show respect, they expect obedience, they share, they manipulate, etc. Being in a group changes their behaviour and their abilities. This is one of the founding insights of sociology: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. The group has properties over and above the properties of its individual members. It has a reality sui generis , of its own kind. But how exactly does the whole come to be greater?

Defining a Group

How can we hone the meaning of the term group more precisely for sociological purposes? The term is an amorphous one and can refer to a wide variety of gatherings, from just two people (think about a “group project” in school when you partner with another student), a club, a regular gathering of friends, or people who work together or share a hobby. In short, the term refers to any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share a sense that their identity is somehow aligned with the group. Of course, every time people gather, they do not necessarily form a group. An audience assembled to watch a street performer is a one-time random gathering. Conservative-minded people who come together to vote in an election are not a group because the members do not necessarily interact with one another with some frequency. People who exist in the same place at the same time, but who do not interact or share a sense of identity—such as a bunch of people standing in line at Starbucks—are considered an aggregate , or a crowd. People who share similar characteristics but are not otherwise tied to one another in any way are considered a category .

An example of a category would be Millennials, the term given to all children born from approximately 1980 to 2000. Why are Millennials a category and not a group? Because while some of them may share a sense of identity, they do not, as a whole, interact frequently with each other.

Interestingly, people within an aggregate or category can become a group. During disasters, people in a neighbourhood (an aggregate) who did not know each other might become friendly and depend on each other at the local shelter. After the disaster ends and the people go back to simply living near each other, the feeling of cohesiveness may last since they have all shared an experience. They might remain a group, practising emergency readiness, coordinating supplies for next time, or taking turns caring for neighbours who need extra help. Similarly, there may be many groups within a single category. Consider teachers, for example. Within this category, groups may exist like teachers’ unions, teachers who coach, or staff members who are involved with the school board.

Types of Groups

Sociologist Charles Horton Cooley (1864–1929) suggested that groups can broadly be divided into two categories: primary groups and secondary groups (Cooley 1909). According to Cooley, primary groups play the most critical role in our lives. The primary group is usually fairly small and is made up of individuals who generally engage face-to-face in long-term, emotional ways. This group serves emotional needs: expressive functions rather than pragmatic ones. The primary group is usually made up of significant others—those individuals who have the most impact on our socialization. The best example of a primary group is the family.

Secondary groups are often larger and impersonal. They may also be task focused and time limited. These groups serve an instrumental function rather than an expressive one, meaning that their role is more goal or task oriented than emotional. A classroom or office can be an example of a secondary group. Neither primary nor secondary groups are bound by strict definitions or set limits. In fact, people can move from one group to another. A graduate seminar, for example, can start as a secondary group focused on the class at hand, but as the students work together throughout their program, they may find common interests and strong ties that transform them into a primary group.

Peter Marsden (1987) refers to one’s group of close social contacts as a core discussion group . These are individuals with whom you can discuss important personal matters or with whom you choose to spend your free time. Christakis and Fowler (2009) found that the average North American had four close personal contacts. However, 12 percent of their sample had no close personal contacts of this sort, while 5 percent had more than eight close personal contacts. Half of the people listed in the core discussion group were characterized as friends, as might be expected, but the other half included family members, spouses, children, colleagues, and professional consultants of various sorts. Marsden’s original research from the 1980s showed that the size of the core discussion group decreases as one ages, there was no difference in size between men and women, and those with a post-secondary degree had core discussion groups almost twice the size of those who had not completed high school.

Making Connections: Careers in Sociology

Best friends she’s never met.

Writer Allison Levy worked alone. While she liked the freedom and flexibility of working from home, she sometimes missed having a community of coworkers, both for the practical purpose of brainstorming and the more social “water cooler” aspect. Levy did what many do in the internet age: she found a group of other writers online through a web forum. Over time, a group of approximately 20 writers, who all wrote for a similar audience, broke off from the larger forum and started a private invitation-only forum. While writers in general represent all genders, ages, and interests, it ended up being a collection of 20- and 30-something women who comprised the new forum—they all wrote fiction for children and young adults.

At first, the writers’ forum was clearly a secondary group united by the members’ professions and work situations. As Levy explained, “On the internet, you can be present or absent as often as you want. No one is expecting you to show up.” It was a useful place to research information about different publishers and who had recently sold what, and to track industry trends. But as time passed, Levy found it served a different purpose. Since the group shared other characteristics beyond their writing (such as age and gender), the online conversation naturally turned to matters such as childrearing, aging parents, health, and exercise. Levy found it was a sympathetic place to talk about any number of subjects, not just writing. Further, when people didn’t post for several days, others expressed concern, asking whether anyone had heard from the missing writers. It reached a point where most members would tell the group if they were travelling or needed to be offline for a while.

The group continued to share. One member on the site who was going through a difficult family illness wrote, “I don’t know where I’d be without you women. It is so great to have a place to vent that I know isn’t hurting anyone.” Others shared similar sentiments.

So is this a primary group? Most of these people have never met each other. They live in Hawaii, Australia, Minnesota, and across the world. They may never meet. Levy wrote recently to the group, saying, “Most of my ‘real-life’ friends and even my husband don’t really get the writing thing. I don’t know what I’d do without you.” Despite the distance and the lack of physical contact, the group clearly fills an expressive need.

In-Groups and Out-Groups

One of the ways that groups can be powerful is through inclusion, and its inverse, exclusion. In-groups and out-groups are subcategories of primary and secondary groups that help identify this dynamic. Primary groups consist of both in-groups and out-groups, as do secondary groups. The feeling that one belongs in an elite or select group is a heady one, while the feeling of not being allowed in, or of being in competition with a group, can be motivating in a different way. Sociologist William Sumner (1840–1910) developed the concepts of in-group and out-group to explain this phenomenon (Sumner 1906). In short, an in-group is the group that an individual feels he or she belongs to, and believes it to be an integral part of who he or she is. An out-group, conversely, is a group someone doesn’t belong to; often there may be a feeling of disdain or competition in relation to an out-group. Sports teams, unions, and secret societies are examples of in-groups and out-groups; people may belong to, or be an outsider to, any of these.

While these affiliations can be neutral or even positive, such as the case of a team-sport competition, the concept of in-groups and out-groups can also explain some negative human behaviour, such as white supremacist movements like the Ku Klux Klan, or the bullying of gay or lesbian students. By defining others as “not like us” and inferior, in-groups can end up practicing ethnocentrism, racism, sexism, ageism, and heterosexism—manners of judging others negatively based on their culture, race, sex, age, or sexuality. Often, in-groups can form within a secondary group. For instance, a workplace can have cliques of people, from senior executives who play golf together, to engineers who write code together, to young singles who socialize after hours. While these in-groups might show favouritism and affinity for other in-group members, the overall organization may be unable or unwilling to acknowledge it. Therefore, it pays to be wary of the politics of in-groups, since members may exclude others as a form of gaining status within the group.

Making Connections: the Big Pictures

Bullying and cyberbullying: how technology has changed the game.

Most of us know that the old rhyme “sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me” is inaccurate. Words can hurt, and never is that more apparent than in instances of bullying. Bullying has always existed, often reaching extreme levels of cruelty in children and young adults. People at these stages of life are especially vulnerable to others’ opinions of them, and they’re deeply invested in their peer groups. Today, technology has ushered in a new era of this dynamic. Cyberbullying is the use of interactive media by one person to torment another, and it is on the rise. Cyberbullying can mean sending threatening texts, harassing someone in a public forum (such as Facebook), hacking someone’s account and pretending to be him or her, posting embarrassing images online, and so on. A study by the Cyberbullying Research Center found that 20 percent of middle-school students admitted to “seriously thinking about committing suicide” as a result of online bullying (Hinduja and Patchin 2010). Whereas bullying face-to-face requires willingness to interact with your victim, cyberbullying allows bullies to harass others from the privacy of their homes without witnessing the damage firsthand. This form of bullying is particularly dangerous because it’s widely accessible and therefore easier to accomplish.

Cyberbullying, and bullying in general, made international headlines in 2012 when a 15-year-old girl, Amanda Todd, in Port Coquitlam, B.C., committed suicide after years of bullying by her peers and internet sexual exploitation. A month before her suicide, she posted a YouTube video in which she recounted her story. It began in grade 7 when she had been lured to reveal her breasts in a webcam photo. A year later, when she refused to give an anonymous male “a show,” the picture was circulated to her friends, family, and contacts on Facebook. Statistics Canada report that 7 percent of internet users aged 18 and over have been cyberbullied, most commonly (73 percent) by receiving threatening or aggressive emails or text messages. Nine percent of adults who had a child at home aged 8 to 17 reported that at least one of their children had been cyberbullied. Two percent reported that their child had been lured or sexually solicited online (Perreault, 2011).

In the aftermath of Amanda Todd’s death, most provinces enacted strict guidelines and codes of conduct obliging schools to respond to cyberbullying and encouraging students to come forward to report victimization. In 2013, the federal government proposed Bill C-13—the Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act–which would make it illegal to share an intimate image of a person without that person’s consent. (Critics however note that the anti-cyberbullying provision in the bill is only a minor measure among many others that expand police powers to surveil all internet activity.) Will these measures change the behaviour of would-be cyberbullies? That remains to be seen. But hopefully communities can work to protect victims before they feel they must resort to extreme measures.

Reference Groups

A reference group is a group that people compare themselves to—it provides a standard of measurement. In Canadian society, peer groups are common reference groups. Children, teens, and adults pay attention to what their peers wear, what music they like, what they do with their free time—and they compare themselves to what they see. Most people have more than one reference group, so a middle-school boy might look not only at his classmates but also at his older brother’s friends and see a different set of norms. And he might observe the antics of his favourite athletes for yet another set of behaviours.

Some other examples of reference groups can be one’s church, synagogue, or mosque; one’s cultural centre, workplace, or family gathering; and even one’s parents. Often, reference groups convey competing messages. For instance, on television and in movies, young adults often have wonderful apartments, cars, and lively social lives despite not holding a job. In music videos, young women might dance and sing in a sexually aggressive way that suggests experience beyond their years. At all ages, we use reference groups to help guide our behaviour and show us social norms. So how important is it to surround yourself with positive reference groups? You may never meet or know a reference group, but it still impacts and influences how you act. Identifying reference groups can help you understand the source of the social identities you aspire to or want to distance yourself from.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

University: a world of in-groups, out-groups, and reference groups.

For a student entering university, the sociological study of groups takes on an immediate and practical meaning. After all, when we arrive someplace new, most of us look around to see how well we fit in or stand out in the ways we want. This is a natural response to a reference group, and on a large campus, there can be many competing groups. Say you are a strong athlete who wants to play intramural sports, but your favourite musicians are a local punk band. You may find yourself engaged with two very different reference groups.

These reference groups can also become your in-groups or out-groups. For instance, different groups on campus might solicit you to join. Are there student-union-sponsored clubs at your school? Is there a club day when the student clubs set up tables and displays? The spelunking club, the Aikido club, the square dance club, the Conservative Party club, the Green Party club, the chess club, the jazz club, the kayak club, the tightrope walkers club, the peace and disarmament club, the French club, the young women in business club—enumerable clubs will try to convince students to join them. While most clubs are pretty casual, along with a shared interest comes many subtle cues about what sorts of people will fit in and what sorts will not. While most campus groups refrain from insulting competing groups, there is a definite sense of an in-group versus an out-group. “Them?” a member might say, “They’re all right, but they are pretty geeky.” Or, “Only really straight people join that group.” This immediate categorization into in-groups and out-groups means that students must choose carefully, since whatever group they associate with will not just define their friends—it may also define types of people with whom they will not associate.

6.2. Groups and Networks

Dyads, triads, and social networks.

A small group is typically one where the collection of people is small enough that all members of the group know each other and share simultaneous interaction, such as a nuclear family, a dyad, or a triad. Georg Simmel wrote extensively about the difference between a dyad , or two-member group, and a triad , a three-member group (Simmel 1902 (1950)). No matter what the content of the groups is—business, friendship, family, teamwork, etc.—the dynamic or formal qualities of the groups differ simply by virtue of the number of individuals involved. In a dyad, if one person withdraws, the group can no longer exist. Examples include a divorce, which effectively ends the “group” of the married couple, or two best friends never speaking again. Neither of the two members can hide what he or she has done behind the group, nor hold the group responsible for what he or she has failed to do.

In a triad, however, the dynamic is quite different. If one person withdraws, the group lives on. A triad has a different set of relationships. If there are three in the group, two-against-one dynamics can develop and the potential exists for a majority opinion on any issue. At the same time, the relationships in a triad cannot be as close as in a dyad because a third person always intrudes. Where a group of two is both closer and more unstable than a group of three, because it rests on the immediate, ongoing reciprocity of the two members, a group of three is able to attain a sense of super-personal life, independent of the members.

The difference between a dyad and a triad is an example of network analysis. A social network is a collection of people tied together by a specific configuration of connections. They can be characterized by the number of people involved, as in the dyad and triad, but also in terms of their structures (who is connected to whom) and functions (what flows across ties). The particular configurations of the connections determine how networks are able to do more things and different things than individuals acting on their own could. Networks have this effect, regardless of the content of the connections or persons involved.

For example, if one person phones 50 people one after the other to see who could come out to play ball hockey on Wednesday night, it would take a long time to work through the phone list. The structure of the network would be one in which the telephone caller has an individual connection with each of the 50 players, but the players themselves do not necessarily have any connections with each other. There is only one node in the network. On the other hand, if the telephone caller phones five key (or nodal) individuals, who would then call five individuals, and so on, then the telephone calling would be accomplished much more quickly. A telephone tree like this has a different network structure than the single telephone caller model does and can therefore accomplish the task much more efficiently and quickly. Of course the responsibility is also shared so there are more opportunities for the communication network to break down.

Network analysis is interesting because much of social life can be understood as operating outside of either formal organizations or traditional group structures. Social media like Twitter or Facebook connect people through networks. One’s posts are seen by friends, but also by friends of friends. The revolution in Tunisia in 2010–2011 was aided by social media networks, which were able to disseminate an accurate, or alternate, account of the events as they unfolded, even while the official media characterized the unrest as vandalism and terrorism (Zuckerman 2011). On the other hand, military counterinsurgency strategies trace cell phone connections to model the networks of insurgents in asymmetrical or guerilla warfare. Increased network densities indicate the ability of insurgents to mount coordinated attacks (Department of the Army 2006). The amorphous nature of global capital and the formation of a global capitalist class consciousness can also be analyzed by mapping interlocking directorates; namely, the way institutionalized social networks are established between banks and corporations in different parts of the world through shared board members (Carroll 2010).

Christakis and Fowler (2009) argue that social networks are influential in a wide range of social aspects of life including political opinions, weight gain, and happiness. They develop Stanley Milgram’s claim that there is only six degrees of separation between any two individuals on Earth by adding that in a network, it can be demonstrated that there are also three degrees of influence. That is, one is not only influenced by one’s immediate friends and social contacts, but by their friends, and their friends’ friends. For example, an individual’s chance of becoming obese increases 57 percent if a friend becomes obese; it increases by 20 percent if it is a friend’s friend who becomes obese; and it increases 10 percent if it is a friend’s friend’s friend who becomes obese. Beyond the third degree of separation, there is no measurable influence.

Large Groups

It is difficult to define exactly when a small group becomes a large group. One step might be when there are too many people to join in a simultaneous discussion. Another might be when a group joins with other groups as part of a movement that unites them. These larger groups may share a geographic space, such as Occupy Montreal or the People’s Assembly of Victoria, or they might be spread out around the globe. The larger the group, the more attention it can garner, and the more pressure members can put toward whatever goal they wish to achieve. At the same time, the larger the group becomes, the more the risk grows for division and lack of cohesion.

Group Leadership

Often, larger groups require some kind of leadership. In small, primary groups, leadership tends to be informal. After all, most families don’t take a vote on who will rule the group, nor do most groups of friends. This is not to say that de facto leaders don’t emerge, but formal leadership is rare. In secondary groups, leadership is usually more overt. There are often clearly outlined roles and responsibilities, with a chain of command to follow. Some secondary groups, like the army, have highly structured and clearly understood chains of command, and many lives depend on those. After all, how well could soldiers function in a battle if they had no idea whom to listen to or if different people were calling out orders? Other secondary groups, like a workplace or a classroom, also have formal leaders, but the styles and functions of leadership can vary significantly.

Leadership function refers to the main focus or goal of the leader. An instrumental leader is one who is goal oriented and largely concerned with accomplishing set tasks. An army general or a Fortune 500 CEO would be an instrumental leader. In contrast, expressive leaders are more concerned with promoting emotional strength and health, and ensuring that people feel supported. Social and religious leaders—rabbis, priests, imams, and directors of youth homes and social service programs—are often perceived as expressive leaders. There is a longstanding stereotype that men are more instrumental leaders and women are more expressive leaders. Although gender roles have changed, even today many women and men who exhibit the opposite-gender manner can be seen as deviants and can encounter resistance. Former U.S. Secretary of State and presidential candidate Hillary Clinton provides an example of how society reacts to a high-profile woman who is an instrumental leader. Despite the stereotype, Boatwright and Forrest (2000) have found that both men and women prefer leaders who use a combination of expressive and instrumental leadership.

In addition to these leadership functions, there are three different leadership styles . Democratic leaders encourage group participation in all decision making. These leaders work hard to build consensus before choosing a course of action and moving forward. This type of leader is particularly common, for example, in a club where the members vote on which activities or projects to pursue. These leaders can be well liked, but there is often a challenge that the work will proceed slowly since consensus building is time-consuming. A further risk is that group members might pick sides and entrench themselves into opposing factions rather than reaching a solution. In contrast, a laissez-faire leader (French for “leave it alone”) is hands-off, allowing group members to self-manage and make their own decisions. An example of this kind of leader might be an art teacher who opens the art cupboard, leaves materials on the shelves, and tells students to help themselves and make some art. While this style can work well with highly motivated and mature participants who have clear goals and guidelines, it risks group dissolution and a lack of progress. As the name suggests, authoritarian leaders issue orders and assigns tasks. These leaders are clear instrumental leaders with a strong focus on meeting goals. Often, entrepreneurs fall into this mould, like Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. Not surprisingly, this type of leader risks alienating the workers. There are times, however, when this style of leadership can be required. In different circumstances, each of these leadership styles can be effective and successful. Consider what leadership style you prefer. Why? Do you like the same style in different areas of your life, such as a classroom, a workplace, and a sports team?

Women Leaders and the Glass Ceiling

Elizabeth May, leader of the Green Party, was voted best parliamentarian of the year in 2012 and hardest working parliamentarian in 2013. She stands out among the party leaders as both the only female and the only leader focused on changing leadership style. Among her proposals for changing leadership are reducing centralization and hierarchical control of party leaders, allowing MPs to vote freely, decreasing narrow political partisanship, engaging in cross-partisan collaboration, and restoring respect and decorum to House of Commons debates. The focus on a collaborative, non-conflictual approach to politics is a component of her expressive leadership style, typically associated with female leadership qualities.

However, as a female leader Elizabeth May is obliged to walk a tight line that does not generally apply to male politicians. According to some political analysts, women candidates face a paradox: they must be as tough as their male opponents on issues such as foreign or economic policy or risk appearing weak (Weeks 2011). However, the stereotypical expectation of women as expressive leaders is still prevalent. Consider that Hillary Clinton’s popularity surged in her 2008 campaign for the U.S. Democratic presidential nomination after she cried on the campaign trail. It was enough for the New York Times to publish an editorial, “Can Hillary Cry Her Way Back to the White House?” (Dowd 2008). Harsh, but her approval ratings soared afterwards. In fact, many compared it to how politically likable she was in the aftermath of President Clinton’s Monica Lewinsky scandal.

In the case of Elizabeth May, many pundits believed that she won the 2008 election leaders debate by being firm in her criticism of government policy and being both intelligent and clear in her statements. (Notably, she was prevented from participating in the 2011 election leaders’ debate, perhaps for the same reasons.) She was able to articulate the rationale behind a national carbon tax to reduce greenhouse gases, whereas then Liberal leader Stéphane Dion seemed to struggle to explain his “Green Shift” policy. “We tax the pollution, and we take the taxes off families,” she said (Foot 2008). The idea of winning debates and defeating opponents in a hostile environment is regarded as a masculine virtue. At the same time, May is subject to criticisms that have to do with her femininity, in a way that male politicians are not subject to similar criticisms about their masculinity. Media tycoon Conrad Black called her “a frumpy, noisy, ill-favoured, half-deranged windbag” to which, May quipped, “He’s right on one point: I certainly am frumpy. I don’t have anything like Barbara Amiel’s [Black’s well-known journalist wife] sense of style. But on the whole, I figure being attacked by Conrad Black is in its own way an accolade in this country” (Allemang 2009).

Despite the cleverness of May’s retort, the pitfalls of her situation as a female leader reflect broader issues women confront in assuming leadership roles. Whereas women have been closing the gap with men in terms of workforce participation and educational attainment over the last decades, their average income has remained at approximately 70 percent of men’s and their representation in leadership roles (legislators, senior officials, and managers) has remained at 50 percent of men’s (i.e., men are twice as likely as women to attain leadership roles in these professions than women). In terms of the representation of women in Parliament, cabinet, and political leadership, the figures are much lower at 15 percent (despite the fact that several provinces have had women as premiers) (McInturff 2013).

One concept for describing the situation facing women’s access to leadership positions is the glass ceiling . Whereas most of the explicit barriers to women’s achievement have been removed through legislative action, norms of gender equality, and affirmative action policies, women often get stuck at the level of middle management. There is a glass ceiling or invisible barrier that prevents them from achieving positions of leadership (Tannen 1994). This is also reflected in gender inequality in income over time. Early in their careers men’s and women’s incomes are more or less equal but at mid-career, the gap increases significantly (McInturff 2013).

Tannen argues that this barrier exists in part because of the different work styles of men and women, in particular conversational-style differences. Whereas men are very aggressive in their conversational style and their self-promotion, women are typically consensus builders who seek to avoid appearing bossy and arrogant. As a linguistic strategy of office politics, it is common for men to say “I” and claim personal credit in situations where women would be more likely to use “we” and emphasize teamwork. As it is men who are often in the positions to make promotion decisions, they interpret women’s style of communication “as showing indecisiveness, inability to assume authority, and even incompetence” (Tannen 1994).

Because of qualities of women’s expressive leadership, which in many cases is more effective, their skills, merits, and achievements go unrecognized. In terms of political leadership, as one political analyst said bluntly, “women don’t succeed in politics—or other professions—unless they act like men. The standard for running for national office remains distinctly male” (Weeks 2011).

We all like to fit in to some degree. Likewise, when we want to stand out, we want to choose how we stand out and for what reasons. For example, a woman who loves cutting-edge fashion and wants to dress in thought-provoking new styles likely wants to be noticed within a framework of high fashion. She would not want people to think she was too poor to find proper clothes. Conformity is the extent to which an individual complies with group norms or expectations. As you might recall, we use reference groups to assess and understand how we should act, dress, and behave. Not surprisingly, young people are particularly aware of who conforms and who does not. A high school boy whose mother makes him wear ironed button-down shirts might protest that he will look stupid—that everyone else wears T-shirts. Another high school boy might like wearing those shirts as a way of standing out. Recall Georg Simmel’s analysis of the contradictory dynamics of fashion: it represents both the need to conform and the need to stand out. How much do you enjoy being noticed? Do you consciously prefer to conform to group norms so as not to be singled out? Are there people in your class or peer group who immediately come to mind when you think about those who do, and do not, want to conform?

A number of famous experiments in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s tested the propensity of individuals to conform to authority. We have already examined the Stanford Prison experiment in Chapter 2. Within days of beginning the simulated prison experiment the random sample of university students proved themselves capable of conforming to the roles of prison guards and prisoners to an extreme degree, even though the conditions were highly artificial (Haney, Banks, and Zimbardo 1973).

Stanley Milgram conducted experiments in the 1960s on how structures of authority rendered individuals obedient (Milgram 1963). This was shortly after the Adolf Eichmann war crime trial in which Eichmann claimed that he was just a bureaucrat following orders when he helped to organize the Holocaust. Milgram had experimental subjects administer what they were led to believe were electric shocks to a subject when the subject gave a wrong answer to a question. Each time a wrong answer was given, the experimental subject was told to increase the intensity of the shock. The experiment was supposed to be testing the relationship between punishment and learning, but the subject receiving the shocks was an actor. As the experimental subjects increased the amount of voltage, the actor began to show distress, eventually begging to be released. When the subjects became reluctant to administer more shocks, Milgram (wearing a white lab coat to underline his authority as a scientist) assured them that the actor would be fine and that the results of the experiment would be compromised if the subject did not continue. Seventy-one percent of the experimental subjects were willing to continue administering shocks even beyond 285 volts even though the actor was clearly in pain and the voltage dial was labelled with warnings like “Danger: Severe shock.”

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Conforming to expectations.