Losing the inflation anchor

- Final paper by Reis

- Comment by Blinder

- Comment by Gorodnichenko

- General Discussion

- Data & Programs

Subscribe to the Economic Studies Bulletin

Ricardo reis ricardo reis a. w. phillips professor of economics - london school of economics and political science discussants: yuriy gorodnichenko yuriy gorodnichenko quantedge presidential professor at the department of economics - university of california - berkeley.

September 8, 2021

The paper summarized here is part of the Fall 2021 edition of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (BPEA) , the leading conference series and journal in economics for timely, cutting-edge research about real-world policy issues. The conference draft of the paper was presented on September 9, 2021 at the Fall 2021 BPEA conference . The final version was published in the Fall 2021 edition by Brookings Institution Press on June 7, 2022. Read all papers published in this edition here» Submit a proposal to present at a future BPEA conference here»

Monetary policymakers trying to judge whether elevated inflation this year will persist should—heeding past lessons from the United States and abroad—carefully track inflation expectations, suggests a paper discussed at the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (BPEA) conference on September 9.

The author—Ricardo Reis of the London School of Economics—examined the expectations of consumers, professional forecasters, and markets for inflation in the United States during the late 1960s and early 1970s (when inflation started climbing), during the early 1980s (when inflation stabilized), and during the COVID-19 pandemic. He also looked at episodes in Brazil and South Africa between 2010 and 2016, and in Turkey after 2017.

“If expectations of inflation rise, households will buy more goods today, savers will shift away from nominal assets [such as bonds], workers will demand higher wages, and firms will post higher prices, all of which lead inflation to rise,” he writes in Losing the inflation anchor . And he warns, “if expected inflation rises, then only a deep recession can keep inflation down.”

He compared trying to anticipate future inflation to sitting on a beach trying to figure out, before it is too late, if a boat is drifting away from shore, and likened inflation expectations gauges to “a grainy picture of the boat’s anchor.”

After examining expectations data for last year and this year, he concludes “the jury is out on whether inflation is going to drift away.” He finds reasons for some concern from household surveys but says monetary policymakers still have time to respond.

The paper begins by focusing on the U.S. experience between 1965 and 1974. Current widely used gauges of expectations, such as the monthly University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers and inflation-indexed Treasury securities, did not exist then.

However, Reis looked at rarely used data, including a short-lived quarterly precursor to the Michigan surveys and the gold futures market in Zurich, Switzerland. He concludes that expectations for U.S. inflation began rising as early as 1967. Had the rise in expectations, and their importance, been recognized earlier, Fed policymakers might have considered acting more forcefully to damp inflation. The Fed did not bring inflation, and expectations, under control until, under Chair Paul Volcker, it undertook highly restrictive monetary policy between 1979 and 1983.

In more-recent episodes, policymakers in Brazil, observing that inflation in 2010 was on target, sharply cut interest rates in 2011. But inflation was restrained only temporarily because of government controls on gasoline and diesel prices, and expectations became unanchored between 2011 and 2016. In Turkey, political pressure on the central bank by President Recep Erdogan in the run-up to elections had, by the end of 2017, unmoored inflation expectations. Actual inflation surged in 2018 and 2019.

South Africa between 2010 and 2016 offers a counter example. Actual inflation pushed to the upper bound of the central bank’s target, but—citing temporary shocks to food and electricity prices—it did not sharply tighten monetary policy. Data shows that expectations remained anchored, and inflation subsided.

Reis writes that it is too soon to tell whether inflation expectations in the United States are drifting away now, as they did in the late 1960s, or whether they will remain anchored despite temporary shocks to key prices, as they did in South Africa. Professional forecasters have only slightly raised their inflation expectations for the United States. Market expectations have moved significantly higher this year but only after falling in 2019 and 2020. Household expectations, however, have jumped up faster in just six months than almost any time since the 1980s.

“Inflation is going to be quite high in 2021. Whether it is a short blip or whether inflation will get out of hand depends on expectations, and there are some worrying signs in the data right now,” he said in an interview with The Brookings Institution. “Ultimately expectations depend on what policy will do in the next few months: Will the FOMC let the anchor drift or not?”

Acknowledgments

David Skidmore authored the summary language for this paper. Becca Portman assisted with data visualization.

Reis, Ricardo. 2021. “Losing the Inflation Anchor.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall, 307-361.

Blinder, Alan S. 2021. “Comment on ‘Losing the Inflation Anchor’.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall, 362-369.

Gorodnichenko, Yuriy. 2021. “Comment on ‘Losing the Inflation Anchor’.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall, 369-377.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

Ricardo Reis’ research is supported by a 5-year grant from the European Research Council. Other than the aforementioned, the author did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. They are currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article.

History of BPEA

Discussants

Economic Indicators Federal Reserve

Economic Studies

Brookings Papers on Economic Activity

Robin Brooks, Peter R. Orszag, William E. Murdock III

August 1, 2024

July 18, 2024

Tom Wheeler

June 7, 2024

- Facebook social media link

- Twitter social media link

- YouTube social media link

- LinkedIn social media link

Mobile Menu Overlay

The causes of and responses to today’s inflation.

December 6, 2022

By Joseph E. Stiglitz, Ira Regmi

- Share this page on Facebook

- Share this page on Twitter

- Share this page via Email Mail Icon Rectangle in the shape of an envelope

The evidence is overwhelming: were there no supply problems, aggregate demand would not be excessive. The inflation we’ve experienced is best understood as resulting from industry-specific problems that many Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries are facing. A strong labor market is part of the solution, not the problem.

Over the last couple years, the world has experienced the highest levels of inflation in more than four decades. There are multiple sources of economic disruption that have likely contributed to this inflation, most notably pandemic shutdowns and reopenings and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The inflation, in turn, has sparked a debate about its causes, with some claiming it is demand-induced, largely the result of high spending in response to the pandemic. Others focus on pandemic-induced supply shortages and demand shifts, possibly exacerbated by market power and market manipulation. While there may be elements of all of these, the policy response needs to address the dominant cause. If it’s a result of excessive aggregate demand , then monetary policy—reducing aggregate demand through monetary tightening—is appropriate. If it’s largely supply-driven, a more tailored response is required, including fiscal policy that alleviates the supply constraints.

Our analysis concludes that today’s inflation is largely driven by supply shocks and sectoral demand shifts, not by excess aggregate demand.

Monetary policy, then, is too blunt an instrument because it will greatly reduce inflation only at the cost of unnecessarily high unemployment, with severe adverse distributive consequences. This paper presents a variety of fiscal and other policy measures that hold out the prospect of having a more significant effect on inflation. In particular, these measures would reduce inflation’s impact on the most vulnerable and provide long-term benefits to the economy without the likely high costs of excessively rapid and large increases in interest rates.

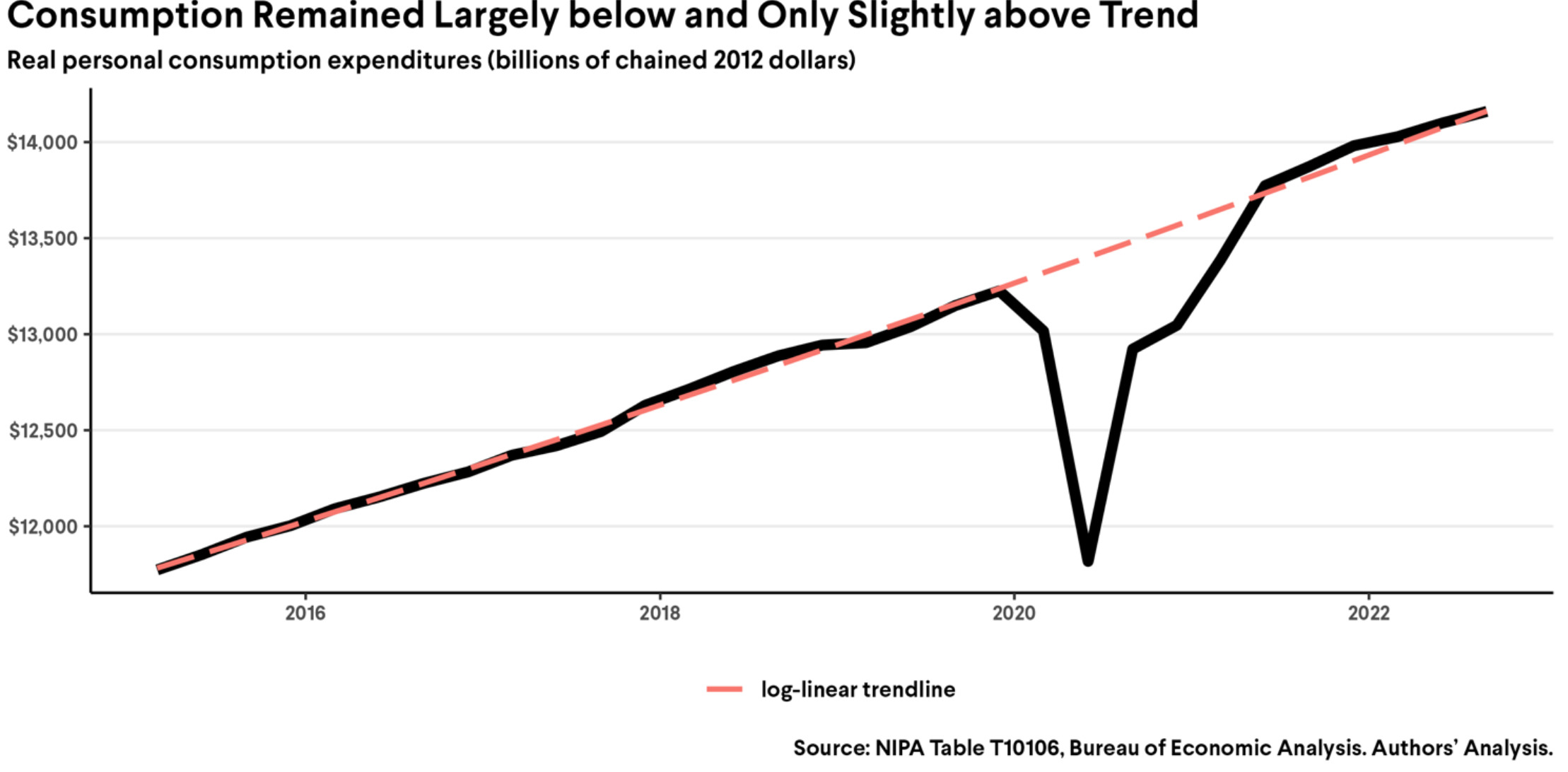

We look at both the aggregate and sectoral-level data, and show, notably, that real personal consumption has largely been below trend, particularly in the periods when inflation heated up, and total real aggregate demand has been consistently below trend, which reinforces the conclusion that the “problem” arises from the supply side.

As seen in the Figure above, real personal consumption has largely been below trend, particularly in the periods when inflation heated up. In addition, with three fiscal quarters of anemic growth, from the fourth quarter of 2021 to the second quarter of 2022, it is hard to see how excess demand by itself could be at the root of the problem.

Is today’s inflation the result of excessive aggregate demand, or is it the result of overlapping sectoral supply side shifts and shocks? We just released a new paper by @JosephEStiglitz and @Regmi_Ira making a wide-ranging case for the latter. 🧵(1/8) https://t.co/TTVBUoOXwo — Roosevelt Institute (@rooseveltinst) December 6, 2022

With three fiscal quarters of anemic growth, from the fourth quarter of 2021 to the second quarter of 2022, it is hard to see how excess demand by itself could be at the root of the problem. Moreover, inflation in the United States is no worse than in other countries even as Americans saw a more robust recovery, largely because we had more fiscal support. A sectoral breakdown of inflation, as well as a closer look at the patterns in the timing of inflation, further support the conclusion that excessive spending during the pandemic is not the principal cause of today’s inflation.

Breaking down inflation by sector reveals that it is tied to the obvious shocks and supply chain interruptions the economy has experienced, from high food and energy prices to the shortage of microchips for automobiles.

We also explain how the large pandemic-induced shifts in demand, such as those associated with housing, have contributed to today’s inflation.

Another important factor is the increase in market concentration, which has generated greater market power; the current circumstances have provided a prime opportunity for a greater exercise of that market power.

A Wage-Price Spiral?

The paper also addresses the concern that inflation will seep through the economy, regardless of its original source, as a wage-price spiral is set in motion. We conclude that with nominal wages already tempered, this does not seem likely. Moreover, declining real wages are typically not a sign of a tight labor market. Weak unions, globalization, and changes in the structure of the economy provide part of the explanation for why wage-price dynamics today may be markedly different from 50 years ago.

Conventional economics worries that inflationary expectations might perpetuate inflation; but so far, inflationary expectations appear mild, perhaps because many market participants agree with our analysis that the underlying sources of today’s inflation are supply side interruptions, less temporary than people had hoped for at the onset of the inflation, but temporary nonetheless. Recent data are consistent with this perspective: While inflation does vary considerably month to month, it is heartening that it has slowed over the last four months to 2.8 percent (BLS CPI; authors’ calculations)—a slowing consistent with the supply side interpretation, but inconsistent with the standard macroeconomic demand-side analysis. (Because there was higher month-over-month inflation at the end of 2021 and the beginning of 2022, the year-over-year rate remains high at 7.7 percent.) The New York Federal Reserve’s “Underlying Inflation Gauge” peaked in July 2022 at 4.9 percent, and by October 2022 was at 4.2 percent.

The Right Policy Response

This analysis provides a different perspective from conventional economics on the appropriate policy responses to current inflation. Conventional wisdom, partly based on a wealth of experience in which demand shocks have given rise to inflation, holds that interest rates should be increased when there is inflation, whatever the cause . Interest rates worldwide have been abnormally low, partly because of the excessive reliance on monetary policy in response to the 2008 financial crisis. But the cost of capital should not be zero (or worse, negative).

Restoring interest rates to more normal levels has distinct advantages. Going beyond that—raising them too far and too quickly—is problematic, especially given the buildup of debt in the era of near-zero interest rates.

Most importantly, such increases in interest rates will not substantially lower inflation unless they induce a major contraction in the economy, which is a cure worse than the disease. An economic downturn like that is likely to have long-lasting adverse effects, and the most marginalized in society will bear the brunt. Volatile energy and food prices are largely internationally driven and not under the control of the Federal Reserve. The recent aggressive hikes have not remedied these price increases and are unlikely to do so in the future. Inflation induced by these price fluctuations may come down (as it has recently in some months in the United States), but not because of Fed action. To the contrary, the paper explains several reasons why large and rapid increases in interest rates, beyond normalizing them, may be counterproductive. For instance, they could impede investments that might alleviate some of the supply shortages.

By contrast, well-designed fiscal and other policies can help to ameliorate the supply shortages, tame inflation, and protect the vulnerable, providing long-term benefits even if it should turn out that inflationary pressures are transient.

Key Takeaways

Today’s inflation comes mostly from sectoral supply side disruptions, largely the result of the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequent disturbances to supply chains; and disruptions to energy and food markets originating from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Demand patterns too have undergone significant changes, again largely induced by the pandemic. In some sectors, these effects have been amplified as a result of the exercise of market power. But today’s inflation, for the most part, is not the result of significant excesses of aggregate demand such as might have arisen from excessive US pandemic spending.

While we welcome the return of interest rates to more normal levels, which reduces a number of distortions associated with persistent, abnormally low interest rates, increasing interest rates too far and too quickly risks a painful slowdown to the economy with minimal benefits to inflation short of a significant downturn. This would have particular adverse distributional consequences, especially for marginalized groups in the country.

There are fiscal and other measures that can and should be taken to alleviate particular sectoral inflationary pressures, and that are likely to be more effective than broad-based interest rate increases.

Recent data shows significant moderation of inflationary pressures, with nominal wage increases in particular being only a little over pre-pandemic levels. This, together with other indicators such as tempered inflationary expectations, goes a long way in alleviating worries about an incipient wage-price spiral.

Explore more of our work on inflation

Inflation in 2023: causes, progress, and solutions.

March 9, 2023

By Mike Konczal

A New Framework for Targeting Inflation: Aiming for a Range of 2 to 3.5 Percent

November 17, 2022

By Justin Bloesch

Why Market Power Matters for Inflation

September 22, 2022

As Inflation Slows, Don’t Credit the Fed

February 17, 2023

By Ira Regmi

How Not to Fight Inflation

January 30, 2023

By Joseph Stiglitz

Is it Time for the Fed to Pause

The Roosevelt Institute hosted a webinar to discuss this report, The Causes of and Responses to Today’s Inflation, by Joseph Stiglitz and Ira Regmi, who find that today’s inflation is largely driven by supply shocks and sectoral demand shifts.

Tags: Democratic Governance , Monetary Policy

Joseph Stiglitz

As chief economist and senior fellow at the Roosevelt Institute, Joseph Stiglitz focuses on income distribution, risk, corporate governance, public policy, macroeconomics, and globalization.

Ira Regmi is the program manager for the macroeconomic analysis program at Roosevelt, where they support the team’s work on fiscal and monetary policy, unemployment, and growth to ensure an economy that works for all.

The Long-term Effects of Inflation on Inflation Expectations

We study the long-term effects of inflation surges on inflation expectations. German households living in areas with higher local inflation during the hyperinflation of the 1920s expect higher inflation today, after partialling out determinants of historical inflation and current inflation expectations . Our evidence points towards transmission of inflation experiences from parents to children and through collective memory. Differential historical inflation also modulates the updating of expectations to current inflation, the response to economic policies affecting inflation, and financial decisions. We obtain similar results for Polish households residing in formerly German areas. Overall, our findings are consistent with inflationary shocks having a long-lasting impact on attitudes towards inflation.

Financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 207668) and the sponsors association of the Swiss Institute of Banking and Finance of the University of St. Gallen is gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

Working Groups

Mentioned in the news, more from nber.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

Essay on Inflation: Types, Causes and Effects

Essay on Inflation!

Essay on the Meaning of Inflation:

Inflation and unemployment are the two most talked-about words in the contemporary society. These two are the big problems that plague all the economies. Almost everyone is sure that he knows what inflation exactly is, but it remains a source of great deal of confusion because it is difficult to define it unambiguously.

Inflation is often defined in terms of its supposed causes. Inflation exists when money supply exceeds available goods and services. Or inflation is attributed to budget deficit financing. A deficit budget may be financed by additional money creation. But the situation of monetary expansion or budget deficit may not cause price level to rise. Hence the difficulty of defining ‘inflation’ .

Inflation may be defined as ‘a sustained upward trend in the general level of prices’ and not the price of only one or two goods. G. Ackley defined inflation as ‘a persistent and appreciable rise in the general level or average of prices’ . In other words, inflation is a state of rising price level, but not rise in the price level. It is not high prices but rising prices that constitute inflation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is an increase in the overall price level. A small rise in prices or a sudden rise in prices is not inflation since these may reflect the short term workings of the market. It is to be pointed out here that inflation is a state of disequilibrium when there occurs a sustained rise in price level.

It is inflation if the prices of most goods go up. However, it is difficult to detect whether there is an upward trend in prices and whether this trend is sustained. That is why inflation is difficult to define in an unambiguous sense.

Let’s measure inflation rate. Suppose, in December 2007, the consumer price index was 193.6 and, in December 2008 it was 223.8. Thus the inflation rate during the last one year was 223.8 – 193.6/193.6 × 100 = 15.6%.

As inflation is a state of rising prices, deflation may be defined as a state of falling prices but not fall in prices. Deflation is, thus, the opposite of inflation, i.e., rise in the value or purchasing power of money. Disinflation is a slowing down of the rate of inflation.

Essay on the Types of Inflation :

As the nature of inflation is not uniform in an economy for all the time, it is wise to distinguish between different types of inflation. Such analysis is useful to study the distributional and other effects of inflation as well as to recommend anti-inflationary policies.

Inflation may be caused by a variety of factors. Its intensity or pace may be different at different times. It may also be classified in accordance with the reactions of the government toward inflation.

Thus, one may observe different types of inflation in the contemporary society:

(a) According to Causes:

i. Currency Inflation:

This type of inflation is caused by the printing of currency notes.

ii. Credit Inflation:

Being profit-making institutions, commercial banks sanction more loans and advances to the public than what the economy needs. Such credit expansion leads to a rise in price level.

iii. Deficit-Induced Inflation:

The budget of the government reflects a deficit when expenditure exceeds revenue. To meet this gap, the government may ask the central bank to print additional money. Since pumping of additional money is required to meet the budget deficit, any price rise may be called deficit-induced inflation.

iv. Demand-Pull Inflation:

An increase in aggregate demand over the available output leads to a rise in the price level. Such inflation is called demand-pull inflation (henceforth DPI). But why does aggregate demand rise? Classical economists attribute this rise in aggregate demand to money supply.

If the supply of money in an economy exceeds the available goods and services, DPI appears. It has been described by Coulborn as a situation of “too much money chasing too few goods” .

Note that, in this region, price level begins to rise. Ultimately, the economy reaches full employment situation, i.e., Range 3, where output does not rise but price level is pulled upward. This is demand-pull inflation. The essence of this type of inflation is “too much spending chasing too few goods.”

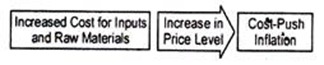

v. Cost-Push Inflation:

Inflation in an economy may arise from the overall increase in the cost of production. This type of inflation is known as cost-push inflation (henceforth CPI). Cost of production may rise due to increase in the price of raw materials, wages, etc. Often trade unions are blamed for wage rise since wage rate is not market-determined. Higher wage means higher cost of production.

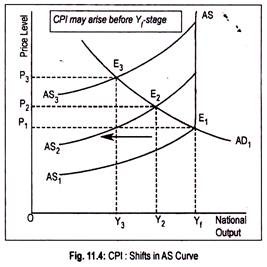

Prices of commodities are thereby increased. A wage-price spiral comes into operation. But, at the same time, firms are to be blamed also for the price rise since they simply raise prices to expand their profit margins. Thus we have two important variants of CPI: wage-push inflation and profit-push inflation. Anyway, CPI stems from the leftward shift of the aggregate supply curve.

The price level thus determined is OP 1 . As aggregate demand curve shifts to AD 2 , price level rises to OP 2 . Thus, an increase in aggregate demand at the full employment stage leads to an increase in price level only, rather than the level of output. However, how much price level will rise following an increase in aggregate demand depends on the slope of the AS curve.

Causes of Demand-Pull Inflation :

DPI originates in the monetary sector. Monetarists’ argument that “only money matters” is based on the assumption that at or near full employment, excessive money supply will increase aggregate demand and will thus cause inflation.

An increase in nominal money supply shifts aggregate demand curve rightward. This enables people to hold excess cash balances. Spending of excess cash balances by them causes price level to rise. Price level will continue to rise until aggregate demand equals aggregate supply.

Keynesians argue that inflation originates in the non-monetary sector or the real sector. Aggregate demand may rise if there is an increase in consumption expenditure following a tax cut. There may be an autonomous increase in business investment or government expenditure. Governmental expenditure is inflationary if the needed money is procured by the government by printing additional money.

In brief, an increase in aggregate demand i.e., increase in (C + I + G + X – M) causes price level to rise. However, aggregate demand may rise following an increase in money supply generated by the printing of additional money (classical argument) which drives prices upward. Thus, money plays a vital role. That is why Milton Friedman believes that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.

There are other reasons that may push aggregate demand and, hence, price level upwards. For instance, growth of population stimulates aggregate demand. Higher export earnings increase the purchasing power of the exporting countries.

Additional purchasing power means additional aggregate demand. Purchasing power and, hence, aggregate demand, may also go up if government repays public debt. Again, there is a tendency on the part of the holders of black money to spend on conspicuous consumption goods. Such tendency fuels inflationary fire. Thus, DPI is caused by a variety of factors.

Cost-Push Inflation Theory :

In addition to aggregate demand, aggregate supply also generates inflationary process. As inflation is caused by a leftward shift of the aggregate supply, we call it CPI. CPI is usually associated with the non-monetary factors. CPI arises due to the increase in cost of production. Cost of production may rise due to a rise in the cost of raw materials or increase in wages.

Such increases in costs are passed on to consumers by firms by raising the prices of the products. Rising wages lead to rising costs. Rising costs lead to rising prices. And rising prices, again, prompt trade unions to demand higher wages. Thus, an inflationary wage-price spiral starts.

This causes aggregate supply curve to shift leftward. This can be demonstrated graphically (Fig. 11.4) where AS 1 is the initial aggregate supply curve. Below the full employment stage this AS curve is positive sloping and at full employment stage it becomes perfectly inelastic. Intersection point (E 1 ) of AD 1 and AS 1 curves determines the price level.

Now, there is a leftward shift of aggregate supply curve to AS 2 . With no change in aggregate demand, this causes price level to rise to OP 2 and output to fall to OY 2 .

With the reduction in output, employment in the economy declines or unemployment rises. Further shift in the AS curve to AS 2 results in higher price level (OP 3 ) and a lower volume of aggregate output (OY 3 ). Thus, CPI may arise even below the full employment (Y f ) stage.

Causes of CPI :

It is the cost factors that pull the prices upward. One of the important causes of price rise is the rise in price of raw materials. For instance, by an administrative order the government may hike the price of petrol or diesel or freight rate. Firms buy these inputs now at a higher price. This leads to an upward pressure on cost of production.

Not only this, CPI is often imported from outside the economy. Increase in the price of petrol by OPEC compels the government to increase the price of petrol and diesel. These two important raw materials are needed by every sector, especially the transport sector. As a result, transport costs go up resulting in higher general price level.

Again, CPI may be induced by wage-push inflation or profit-push inflation. Trade unions demand higher money wages as a compensation against inflationary price rise. If increase in money wages exceeds labour productivity, aggregate supply will shift upward and leftward. Firms often exercise power by pushing up prices independently of consumer demand to expand their profit margins.

Fiscal policy changes, such as an increase in tax rates leads to an upward pressure in cost of production. For instance, an overall increase in excise tax of mass consumption goods is definitely inflationary. That is why government is then accused of causing inflation.

Finally, production setbacks may result in decreases in output. Natural disaster, exhaustion of natural resources, work stoppages, electric power cuts, etc., may cause aggregate output to decline.

In the midst of this output reduction, artificial scarcity of any goods by traders and hoarders just simply ignite the situation.

Inefficiency, corruption, mismanagement of the economy may also be the other reasons. Thus, inflation is caused by the interplay of various factors. A particular factor cannot be held responsible for inflationary price rise.

Essay on the Effects of Inflation :

People’s desires are inconsistent. When they act as buyers they want prices of goods and services to remain stable but as sellers they expect the prices of goods and services should go up. Such a happy outcome may arise for some individuals; “but, when this happens, others will be getting the worst of both worlds.” Since inflation reduces purchasing power it is bad.

The old people are in the habit of recalling the days when the price of say, meat per kilogram cost just 10 rupees. Today it is Rs. 250 per kilogram. This is true for all other commodities. When they enjoyed a better living standard. Imagine today, how worse we are! But meanwhile, wages and salaries of people have risen to a great height, compared to the ‘good old days’. This goes unusually untold.

When price level goes up, there is both a gainer and a loser. To evaluate the consequence of inflation, one must identify the nature of inflation which may be anticipated and unanticipated. If inflation is anticipated, people can adjust with the new situation and costs of inflation to the society will be smaller.

In reality, people cannot predict accurately future events or people often make mistakes in predicting the course of inflation. In other words, inflation may be unanticipated when people fail to adjust completely. This creates various problems.

One can study the effects of unanticipated inflation under two broad headings:

(i) Effect on distribution of income and wealth

(ii) Effect on economic growth.

(a) Effects of Inflation on Income and Wealth Distribution :

During inflation, usually people experience rise in incomes. But some people gain during inflation at the expense of others. Some individuals gain because their money incomes rise more rapidly than the prices and some lose because prices rise more rapidly than their incomes during inflation. Thus, it redistributes income and wealth.

Though no conclusive evidence can be cited, it can be asserted that following categories of people are affected by inflation differently:

i. Creditors and Debtors:

Borrowers gain and lenders lose during inflation because debts are fixed in rupee terms. When debts are repaid their real value declines by the price level increase and, hence, creditors lose. An individual may be interested in buying a house by taking a loan of Rs. 7 lakh from an institution for 7 years.

The borrower now welcomes inflation since he will have to pay less in real terms than when it was borrowed. Lender, in the process, loses since the rate of interest payable remains unaltered as per agreement. Because of inflation, the borrower is given ‘dear’ rupees, but pays back ‘cheap’ rupees.

However, if in an inflation-ridden economy creditors chronically loose, it is wise not to advance loans or to shut down business. Never does it happen. Rather, the loan- giving institution makes adequate safeguard against the erosion of real value.

ii. Bond and Debenture-Holders:

In an economy, there are some people who live on interest income—they suffer most.

Bondholders earn fixed interest income:

These people suffer a reduction in real income when prices rise. In other words, the value of one’s savings decline if the interest rate falls short of inflation rate. Similarly, beneficiaries from life insurance programmes are also hit badly by inflation since real value of savings deteriorate.

iii. Investors:

People who put their money in shares during inflation are expected to gain since the possibility of earning business profit brightens. Higher profit induces owners of firms to distribute profit among investors or shareholders.

iv. Salaried People and Wage-Earners:

Anyone earning a fixed income is damaged by inflation. Sometimes, unionized worker succeeds in raising wage rates of white-collar workers as a compensation against price rise. But wage rate changes with a long time lag. In other words, wage rate increases always lag behind price increases.

Naturally, inflation results in a reduction in real purchasing power of fixed income earners. On the other hand, people earning flexible incomes may gain during inflation. The nominal incomes of such people outstrip the general price rise. As a result, real incomes of this income group increase.

v. Profit-Earners, Speculators and Black Marketeers:

It is argued that profit-earners gain from inflation. Profit tends to rise during inflation. Seeing inflation, businessmen raise the prices of their products. This results in a bigger profit. Profit margin, however, may not be high when the rate of inflation climbs to a high level.

However, speculators dealing in business in essential commodities usually stand to gain by inflation. Black marketeers are also benefited by inflation.

Thus, there occurs a redistribution of income and wealth. It is said that rich becomes richer and poor becomes poorer during inflation. However, no such hard and fast generalizations can be made. It is clear that someone wins and someone loses from inflation.

These effects of inflation may persist if inflation is unanticipated. However, the redistributive burdens of inflation on income and wealth are most likely to be minimal if inflation is anticipated by the people.

With anticipated inflation, people can build up their strategies to cope with inflation. If the annual rate of inflation in an economy is anticipated correctly people will try to protect them against losses resulting from inflation.

Workers will demand 10 p.c. wage increase if inflation is expected to rise by 10 p.c. Similarly, a percentage of inflation premium will be demanded by creditors from debtors. Business firms will also fix prices of their products in accordance with the anticipated price rise. Now if the entire society “learns to live with inflation” , the redistributive effect of inflation will be minimal.

However, it is difficult to anticipate properly every episode of inflation. Further, even if it is anticipated it cannot be perfect. In addition, adjustment with the new expected inflationary conditions may not be possible for all categories of people. Thus, adverse redistributive effects are likely to occur.

Finally, anticipated inflation may also be costly to the society. If people’s expectation regarding future price rise become stronger they will hold less liquid money. Mere holding of cash balances during inflation is unwise since its real value declines. That is why people use their money balances in buying real estate, gold, jewellery, etc.

Such investment is referred to as unproductive investment. Thus, during inflation of anticipated variety, there occurs a diversion of resources from priority to non-priority or unproductive sectors.

b. Effect on Production and Economic Growth :

Inflation may or may not result in higher output. Below the full employment stage, inflation has a favourable effect on production. In general, profit is a rising function of the price level. An inflationary situation gives an incentive to businessmen to raise prices of their products so as to earn higher doses of profit.

Rising price and rising profit encourage firms to make larger investments. As a result, the multiplier effect of investment will come into operation resulting in higher national output. However, such a favourable effect of inflation will be temporary if wages and production costs rise very rapidly.

Further, inflationary situation may be associated with the fall in output, particularly if inflation is of the cost-push variety. Thus, there is no strict relationship between prices and output. An increase in aggregate demand will increase both prices and output, but a supply shock will raise prices and lower output.

Inflation may also lower down further production levels. It is commonly assumed that if inflationary tendencies nurtured by experienced inflation persist in future, people will now save less and consume more. Rising saving propensities will result in lower further outputs.

One may also argue that inflation creates an air of uncertainty in the minds of business community, particularly when the rate of inflation fluctuates. In the midst of rising inflationary trend, firms cannot accurately estimate their costs and revenues. Under the circumstance, business firms may be deterred in investing. This will adversely affect the growth performance of the economy.

However, slight dose of inflation is necessary for economic growth. Mild inflation has an encouraging effect on national output. But it is difficult to make the price rise of a creeping variety. High rate of inflation acts as a disincentive to long run economic growth. The way the hyperinflation affects economic growth is summed up here.

We know that hyperinflation discourages savings. A fall in savings means a lower rate of capital formation. A low rate of capital formation hinders economic growth. Further, during excessive price rise, there occurs an increase in unproductive investment in real estate, gold, jewellery, etc.

Above all, speculative businesses flourish during inflation resulting in artificial scarcities and, hence, further rise in prices. Again, following hyperinflation, export earnings decline resulting in a wide imbalance in the balance of payments account.

Often, galloping inflation results in a ‘flight’ of capital to foreign countries since people lose confidence and faith over the monetary arrangements of the country, thereby resulting in a scarcity of resources. Finally, real value of tax revenue also declines under the impact of hyperinflation. Government then experiences a shortfall in investible resources.

Thus, economists and policy makers are unanimous regarding the dangers of high price rise. But the consequence of hyperinflation is disastrous. In the past, some of the world economies (e.g., Germany after the First World War (1914-1918), Latin American countries in the 1980s) had been greatly ravaged by hyperinflation.

The German Inflation of 1920s was also Catastrophic:

During 1922, the German price level went up 5,470 per cent, in 1923, the situation worsened; the German price level rose 1,300,000,000 times. By October of 1923, the postage of the lightest letter sent from Germany to the United States was 200,000 marks.

Butter cost 1.5 million marks per pound, meat 2 million marks, a loaf of bread 200,000 marks, and an egg 60,000 marks Prices increased so rapidly that waiters changed the prices on the menu several times during the course of a lunch!! Sometimes, customers had to pay double the price listed on the menu when they observed it first!!!

During October 2008, Zimbabwe, under the President-ship of Robert G. Mugabe, experienced 231,000,000 p.c. (2.31 million p.c.) as against 1.2 million p.c. price rise in September 2008—a record after 1923. It is an unbelievable rate. In May 2008, the cost of price of a toilet paper itself and not the costs of the roll of the toilet paper came to 417 Zimbabwean dollars.

Anyway, people are harassed ultimately by the high rate of inflation. That is why it is said that ‘inflation is our public enemy number one’. Rising inflation rate is a sign of failure on the part of the government.

Related Articles:

- Essay on the Causes of Inflation (473 Words)

- Cost-Push Inflation and Demand-Pull or Mixed Inflation

- Demand Pull Inflation and Cost Push Inflation | Money

- Essay on Inflation: Meaning, Measurement and Causes

- Cadmus Home

- Department of Economics (ECO)

Essays on the dynamics of inflation expectations

Retrieved from Cadmus, EUI Research Repository

Show full item record

Files associated with this item

Collections

- About the New York Fed

- Bank Leadership

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Communities We Serve

- Board of Directors

- Disclosures

- Ethics and Conflicts of Interest

- Annual Financial Statements

- News & Events

- Advisory Groups

- Vendor Information

- Holiday Schedule

At the New York Fed, our mission is to make the U.S. economy stronger and the financial system more stable for all segments of society. We do this by executing monetary policy, providing financial services, supervising banks and conducting research and providing expertise on issues that impact the nation and communities we serve.

The New York Innovation Center bridges the worlds of finance, technology, and innovation and generates insights into high-value central bank-related opportunities.

Do you have a request for information and records? Learn how to submit it.

Learn about the history of the New York Fed and central banking in the United States through articles, speeches, photos and video.

- Markets & Policy Implementation

- Reference Rates

- Effective Federal Funds Rate

- Overnight Bank Funding Rate

- Secured Overnight Financing Rate

- SOFR Averages & Index

- Broad General Collateral Rate

- Tri-Party General Collateral Rate

- Desk Operations

- Treasury Securities

- Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities

- Reverse Repos

- Securities Lending

- Central Bank Liquidity Swaps

- System Open Market Account Holdings

- Primary Dealer Statistics

- Historical Transaction Data

- Monetary Policy Implementation

- Agency Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities

- Agency Debt Securities

- Repos & Reverse Repos

- Discount Window

- Treasury Debt Auctions & Buybacks as Fiscal Agent

- INTERNATIONAL MARKET OPERATIONS

- Foreign Exchange

- Foreign Reserves Management

- Central Bank Swap Arrangements

- Statements & Operating Policies

- Survey of Primary Dealers

- Survey of Market Participants

- Annual Reports

- Primary Dealers

- Standing Repo Facility Counterparties

- Reverse Repo Counterparties

- Foreign Exchange Counterparties

- Foreign Reserves Management Counterparties

- Operational Readiness

- Central Bank & International Account Services

- Programs Archive

- Economic Research

- Consumer Expectations & Behavior

- Survey of Consumer Expectations

- Household Debt & Credit Report

- Home Price Changes

- Growth & Inflation

- Equitable Growth Indicators

- Multivariate Core Trend Inflation

- New York Fed DSGE Model

- New York Fed Staff Nowcast

- R-star: Natural Rate of Interest

- Labor Market

- Labor Market for Recent College Graduates

- Financial Stability

- Corporate Bond Market Distress Index

- Outlook-at-Risk

- Treasury Term Premia

- Yield Curve as a Leading Indicator

- Banking Research Data Sets

- Quarterly Trends for Consolidated U.S. Banking Organizations

- Empire State Manufacturing Survey

- Business Leaders Survey

- Supplemental Survey Report

- Regional Employment Trends

- Early Benchmarked Employment Data

- INTERNATIONAL ECONOMY

- Global Supply Chain Pressure Index

- Staff Economists

- Visiting Scholars

- Resident Scholars

- PUBLICATIONS

- Liberty Street Economics

- Staff Reports

- Economic Policy Review

- RESEARCH CENTERS

- Applied Macroeconomics & Econometrics Center (AMEC)

- Center for Microeconomic Data (CMD)

- Economic Indicators Calendar

- Financial Institution Supervision

- Regulations

- Reporting Forms

- Correspondence

- Bank Applications

- Community Reinvestment Act Exams

- Frauds and Scams

As part of our core mission, we supervise and regulate financial institutions in the Second District. Our primary objective is to maintain a safe and competitive U.S. and global banking system.

The Governance & Culture Reform hub is designed to foster discussion about corporate governance and the reform of culture and behavior in the financial services industry.

Need to file a report with the New York Fed? Here are all of the forms, instructions and other information related to regulatory and statistical reporting in one spot.

The New York Fed works to protect consumers as well as provides information and resources on how to avoid and report specific scams.

- Financial Services & Infrastructure

- Services For Financial Institutions

- Payment Services

- Payment System Oversight

- International Services, Seminars & Training

- Tri-Party Repo Infrastructure Reform

- Managing Foreign Exchange

- Money Market Funds

- Over-The-Counter Derivatives

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York works to promote sound and well-functioning financial systems and markets through its provision of industry and payment services, advancement of infrastructure reform in key markets and training and educational support to international institutions.

The New York Fed offers the Central Banking Seminar and several specialized courses for central bankers and financial supervisors.

The New York Fed has been working with tri-party repo market participants to make changes to improve the resiliency of the market to financial stress.

- Community Development & Education

- Household Financial Well-being

- Fed Communities

- Fed Listens

- Fed Small Business

- Workforce Development

- Other Community Development Work

- High School Fed Challenge

- College Fed Challenge

- Teacher Professional Development

- Classroom Visits

- Museum & Learning Center Visits

- Educational Comic Books

- Economist Spotlight Series

- Lesson Plans and Resources

- Economic Education Calendar

We are connecting emerging solutions with funding in three areas—health, household financial stability, and climate—to improve life for underserved communities. Learn more by reading our strategy.

The Economic Inequality & Equitable Growth hub is a collection of research, analysis and convenings to help better understand economic inequality.

Short-Term Inflation Expectations Decline Slightly; Consumer Optimism about Stock Market Reaches Three-Year High

NEW YORK—The Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Center for Microeconomic Data today released the May 2024 Survey of Consumer Expectations , which shows inflation expectations declined at the short-term horizon, remained unchanged at the medium-term horizon, and increased at the longer-term horizon. Labor market expectations were mixed. Households’ expectations for the stock market improved, reaching a three-year high. Households were also more optimistic about their financial situation a year from now.

The main findings from the May 2024 Survey are:

- Median inflation expectations at the one-year horizon declined to 3.2% in May from 3.3% in April, were unchanged at the three-year horizon at 2.8%, and increased at the five-year horizon to 3.0% from 2.8%. The survey’s measure of disagreement across respondents (the difference between the 75th and 25th percentile of inflation expectations) decreased at the one-year horizon, increased at the three-year horizon, and remained unchanged at the five-year horizon.

- Median inflation uncertainty—or the uncertainty expressed regarding future inflation outcomes—increased at the one- and three-year horizons and declined at the five-year horizon.

- Median home price growth expectations were unchanged at 3.3%.

- Median year-ahead expected price changes were unchanged for gas (at 4.8%), food (5.3%), and rent (9.1%). They increased by 0.4 percentage point for medical care, to 9.1%, and declined by 0.6 percentage point for the cost of a college education, to 8.4%.

Labor M arket

- Median one-year-ahead expected earnings growth was unchanged at 2.7%, just below its 12-month trailing average of 2.8%.

- Mean unemployment expectations—or the mean probability that the U.S. unemployment rate will be higher one year from now—increased to 38.6% from 37.2%, and is now above the 12-month trailing average of 37.8%.

- The mean perceived probability of losing one’s job in the next 12 months decreased by 2.7 percentage points to 12.4%, falling below the 12-month trailing average of 13.2%. The mean probability of leaving one’s job voluntarily in the next 12 months increased slightly, to 19.6% from 19.4%, remaining slightly above the 12-month trailing average of 18.9%.

- The mean perceived probability of finding a job if one’s current job was lost increased by 1.3 percentage points to 52.2%, after reaching the lowest level since April 2021 last month.

Household Finance

- Median expected growth in household income increased by 0.1 percentage point to 3.1%, remaining within the narrow range of 2.9% to 3.2% the series has maintained for the past year.

- Median household spending growth expectations declined by 0.2 percentage point to 5.0%. The series has moved within a narrow range of 5.0% to 5.2% since November 2023, remaining well above its February 2020 level of 3.1%.

- Perceptions of credit access compared to a year ago were largely unchanged, while expectations about future credit access deteriorated, with a larger share of respondents expecting tighter credit conditions a year from now, and a smaller share expecting easier conditions.

- The average perceived probability of missing a minimum debt payment over the next three months decreased by 0.9 percentage point to 12.0%, a level comparable to those prevailing just before the pandemic.

- The median expected year-ahead change in taxes at current income level declined by 0.4 percentage point to 3.9%.

- Median year-ahead expected growth in government debt decreased to 9.3% from 9.6%.

- The mean perceived probability that the average interest rate on saving accounts will be higher in 12 months increased by 1.5 percentage points to 27.0%, the highest reading since November 2023.

- Perceptions about households’ current financial situations improved, with more respondents reporting being better off than a year ago and fewer respondents reporting being worse off. Year-ahead expectations also improved, with a smaller share of respondents expecting to be worse off and a larger share of respondents expecting to be better off a year from now. The share of respondents expecting to be financially the same or better off 12 months from now is 78.1%, the highest level since June 2021.

- The mean perceived probability that U.S. stock prices will be higher 12 months from now increased by 1.8 percentage points to 40.5%, the highest level since May 2021.

About the Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE) The SCE contains information about how consumers expect overall inflation and prices for food, gas, housing, and education to behave. It also provides insight into Americans’ views about job prospects and earnings growth and their expectations about future spending and access to credit. The SCE also provides measures of uncertainty regarding consumers’ outlooks. Expectations are also available by age, geography, income, education, and numeracy.

The SCE is a nationally representative, internet-based survey of a rotating panel of approximately 1,300 household heads. Respondents participate in the panel for up to 12 months, with a roughly equal number rotating in and out of the panel each month. Unlike comparable surveys based on repeated cross-sections with a different set of respondents in each wave, this panel allows us to observe the changes in expectations and behavior of the same individuals over time. For further information on the SCE, please refer to an overview of the survey methodology , the interactive chart guide , and the survey questionnaire .

- Request a Speaker

- International Seminars & Training

- Governance & Culture Reform

- Data Visualization

- Economic Research Tracker

- Markets Data APIs

- Terms of Use

Digitala Vetenskapliga Arkivet

| Please wait ... |

- Essays on Inflation Expectations, Monetary Policy and Tax Reform

- CSV all metadata

- CSV all metadata version 2

- modern-language-association-8th-edition

- Other style

- Other locale

Westergren, Kerstin

Description, abstract [en].

This thesis consists of three self-contained essays.

Essay I: Why do consumers’ expenditure patterns matter for their inflation expectations? I propose a model of rational inattention where a consumer trades off paying attention between goods bought more or less frequently. For each good purchased, the consumer observes the rate of price change with an error that depends on the frequency at which the good is purchased. Goods bought less frequently are observed with a greater level of error. I apply a simple version of the model where the inflation index is decomposed into two sub-index components; one sub-index contains goods bought often, and the other contains goods that are not bought often. My results show that the consumer pays more attention to goods bought often. The model is able to match about 60% of the variation in the inflation expectations of the average Swedish household over the time period 2002-2017. A decomposition of the model shows that the consumer’s attention allocation trade-off between these two sub-index components is an important factor in the model’s ability to explain the variation in inflation expectations expressed by Swedish households.

Essay II: What is the effect of monetary policy announcements on inflation expectations? Using survey data of Swedish households’ inflation expectations over the time period 2003-2015, I examine this question using a two-stage least squares regression model. The announced changes are instrumented by a monetary policy surprise variable, obtained from high-frequency swap trade data. I find that the immediate effect of an announced increase in the policy rate on inflation expectations is significant and positive. This result may be interpreted as the policy announcement signaling the central bank’s private information on the direction of future inflation. Specifically, a division of the monetary policy surprise associated with each announcement as either a pure monetary policy surprise or an information surprise shows that the effect of an announced increase in the policy rate on inflation expectations is significant and positive only for the latter type of surprise.

Essay III (with Charlotte Paulie and Markus Ridder): For the past several decades, wealth inequality has increased in many countries. Do changes in the tax system contribute to these trends? Using a quantitative model, we examine the effect on wealth inequality of changing from a comprehensive to a dual tax system. We start with a standard open-economy incomplete-markets model, to which we add an entrepreneurial sector. The entrepreneurs in the model exploit the duality of the tax system after the reform by declaring income as capital (taxed at a flat rate) rather than labor income (taxed progressively). The model is parameterized to match the characteristics of the Swedish economy under dual taxation. In contrast to previous studies, we estimate the parameters of the stochastic process for entrepreneurial income using micro-data observations. We find that the introduction of a dual tax system increases wealth inequality and that the possibility of the entrepreneurs to declare income as capital plays an important role for this result. We also find that the level of aggregate capital and the share of entrepreneurs is higher in an economy with a dual tax system.

Place, publisher, year, edition, pages

Keywords [en], national category, research subject, identifiers, public defence, wiederholt, mirko, professor, supervisors, gottfries, nils, professor, finocchiaro, daria, phd, pitschner, stefan, assistant professor, open access in diva, file information, search in diva, by author/editor, by organisation, on the subject, search outside of diva, altmetric score.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

How to Avoid Another Recession

By Gabriel Chodorow-Reich

Dr. Chodorow-Reich is a professor of economics at Harvard and a visiting scholar at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Financial markets have suddenly begun to price in the risk of a U.S. recession. The S&P 500 closed on Wednesday down almost 7 percent from one month ago, with nearly all of the decline concentrated in the past few days.

Where should the Federal Reserve go from here? Given the surprise increase in the unemployment rate and the reaction of financial markets, it seems safe to assume that policymakers wish they had reduced rates at last week’s meeting. But the failure to do so need not be costly, and correcting it does not require an emergency meeting and a rate cut.

The proximate cause of the market reaction is last week’s Employment Situation report showing the jobless rate at a 33-month high, having risen 0.6 percent since January. The deeper concern is that the Fed remains behind the curve, keeping its policy rate too high as it is still overly focused on fighting the last war of inflation reduction. The new reality is becoming clearer: inflation almost back to the target rate of 2 percent and weakening in the real economy.

The facts dictate concern but not panic. Start with the latest labor market data. The July unemployment rate of 4.3 percent is not historically high. In fact, Fed policymakers have long predicted that their tightening cycle would result in an unemployment rate at the end of 2024 around 4.5 percent. If the unemployment rate peaks around its current level, the Fed will justifiably celebrate having achieved a soft landing.

The concern is the upward trend. The post-World War II historical record contains seven previous episodes when the unemployment rate stood below 5 percent, having risen 0.5 percent or more over the previous six months; on average, over the subsequent six months, the unemployment rate rose a further 1.7 percentage points. Such an increase would indeed bring the U.S. economy into a recession. Yet, past need not be prologue.

To understand the Fed’s quandary, consider why it raised interest rates and has kept them high. Inflation in the Fed’s preferred price index surpassed 7 percent in the 12 months ending in June 2022, a result of a mix of commodity price shocks and sectoral bottlenecks brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic, changing preferences in housing markets and expansionary fiscal policy , including the American Rescue Plan.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

- Main navigation

- Main content

Center for Inflation Research

The Cleveland Fed is home to the Center for Inflation Research, a leading resource for “all things inflation.” Explore commentary, research, and analysis on inflationary trends from the Center, and find out about upcoming inflation-related events.

Our inflation resources

Inflation indicators and data, our center's latest news, our inflation research.

Economic Commentaries About Inflation

Economic Commentaries provide analysis of relevant economic issues and are written for an informed but nonspecialist audience. Browse the Economic Commentaries about inflation written by our economists.

Working Papers About Inflation

Working Papers are preliminary versions of technical papers containing results and discussions of current research. Written for eventual publication in professional economics journals. Browse the Working Papers about inflation written by our economists.

Our Inflation Resources

About the Center for Inflation Research

The Center for Inflation Research is guided by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland and an advisory council consisting of leading experts from the United States and abroad who provide external perspectives and input into the Center's projects and conferences.

Inflation 101

Here is your guide to understanding inflation. The Cleveland Fed's Center for Inflation Research provides inflation basics and explanations of inflation essentials for you to explore.

Conferences: Center for Inflation Research

Find information about our dedicated inflation conferences, papers presented at our past conferences, and our sponsorship of conference sessions.

Measures of Expected Inflation

We explain why expected inflation is important to consumers and the Federal Reserve and how it affects actual inflation. We explain the two basic approaches to measuring them, model-based and survey-based measures.

Consumer Price Data

We explain how measures of consumer prices are computed and what the differences are between the consumer price index (CPI) and the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. We explain various measures used to gauge underlying inflation, or the long-term trend in prices, such as medians and other trimmed-mean measures and core measures of inflation.

Inflation Indicators and Data

The median CPI is a measure of inflation computed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. It ranks the components of CPI inflation and picks the one in the middle. Its construction makes it less sensitive to short-lived price fluctuations, thereby better capturing the trend in prices. Released monthly.

Median PCE Inflation

Median PCE inflation is a measure of inflation computed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. It ranks the components of PCE inflation and picks the one in the middle. Its construction makes it less sensitive to short-lived price fluctuations, thereby better capturing the trend in prices. Released monthly.

Inflation Nowcasting

The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland provides daily “nowcasts” of inflation for two popular price indexes, the price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE) and the Consumer Price Index (CPI). These nowcasts give a sense of where inflation is today. Released each business day.

Inflation Expectations

We report average expected inflation rates over the next one through 30 years. Our estimates of expected inflation rates are calculated using a Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland model that combines financial data and survey-based measures. Released monthly.

Survey of Firms' Inflation Expectations

The Survey of Firms’ Inflation Expectations (SoFIE) is a large quarterly representative panel of firms in the manufacturing and services sectors that was created to measure inflation expectations of chief executive officers (CEOs) in the United States. Released quarterly.

Inflation Charting

Examine and compare the behavior of various measures of total inflation and underlying inflation.

Center updates, direct to your inbox

Register to receive the Center for Inflation Research newsletter and other notifications by email. (Rest assured, we won’t share your information, and you can unsubscribe at any time.)

Read the most recent issue.

Learn more about our center

Lowering inflation: the who, what, and how.

CfIR leaders and experts from other Banks discuss how the Federal Reserve works to control inflation

https://youtu.be/qVgW2ozAKz8

Watch our leaders discuss what motivated the launch of our Center and the data and indicators available on this website.

COMMENTS

Inflation expectations are simply the rate at which people—consumers, businesses, investors—expect prices to rise in the future. They matter because actual inflation depends, in part, on what ...

The main essay of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis' 2023 annual report focuses on various aspects of inflation. This overview defines inflation and examines different views about its causes. ... Throughout the episode, short-term inflation expectations trailed actual inflation, while medium- and long-term expectations remained anchored ...

Abstract. Economists and economic policymakers believe that households' and firms' expectations of future inflation are a key determinant of actual inflation. A review of the relevant theoretical and empirical literature suggests that this belief rests on extremely shaky foundations, and a case is made that adhering to it uncritically could ...

Inflation. 05.28.2019. Inflation expectations are what people expect future inflation to be, and they matter because these expectations actually affect people's behavior. It's easy to understand how things in the past impact what I do today. Expectations about the future can also impact what I do today. For example, I may not buy a house, I ...

The stabilization, or anchoring, of inflation expectations at a target can help a central bank meet its goals. This paper develops a measure of expectations' anchoring that combines the deviation of a consensus forecast from an inflation target with forecaster disagreement. We apply the measure to survey-based forecasts of PCE price inflation at medium- and longer-run horizons. Following the ...

This paper studies how and why inflation expectations have changed since the emergence of Covid-19. Using micro-level data from the University of Michigan Survey of Consumers, we show that the distribution of consumer expectations at one-year and five-ten year horizons has widened since the surge of inflation during 2021, along with the mean. Persistently high and heterogeneous expectations of ...

Under optimistic assumptions for both the V/U ratio and long-term inflation expectations (and assuming the Fed's 4.1 percent unemployment projection proves correct), the paper projects the Fed ...

The author—Ricardo Reis of the London School of Economics—examined the expectations of consumers, professional forecasters, and markets for inflation in the United States during the late 1960s ...

Working Paper 29825. DOI 10.3386/w29825. Issue Date March 2022. Inflation expectations are central to economics because they affect the effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policy as well as realized inflation. We survey the recent literature with a focus on the inflation expectations of households. We first review standard data sources and ...

The Federal Reserve's monetary policy framework emphasizes the role of well-anchored inflation expectations in helping to achieve and maintain price stability. In 2012, the FOMC first established its explicit 2 percent longer-run inflation goal. The FOMC's statement on longer-run goals and monetary policy strategy, revised in 2020 and ...

Westergren, K. 2021. Essays on Inflation Expectations, Monetary Policy and Tax Reform. Economic studies 200. 124 pp. Uppsala: Department of Economics, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-2885-2. This thesis consists of three self-contained essays. Essay I: Why do consumers' expenditure patterns matter for their inflation expectations? I

(Because there was higher month-over-month inflation at the end of 2021 and the beginning of 2022, the year-over-year rate remains high at 7.7 percent.) The New York Federal Reserve's "Underlying Inflation Gauge" peaked in July 2022 at 4.9 percent, and by October 2022 was at 4.2 percent. The Right Policy Response

Inflation expectations play an important role in estimated Phillips-curve equa-tions. Recent papers on the Phillips curve include Mavioeidis et al. (2014), Haxell et al. (2022), Beaudry et al. (2024), Furianetto et al. (2024), and Jorgensen et al. (2024). In a typical Phillips-curve specification the left hand side (LHS) variable

changes in inflation expectations for economic choices. The first chapter examines to what extent monetary policy moves household inflation expectations. More specifically, I study the effect of different types of monetary policy announcements on household inflation expectations based on micro data from a survey of German households. As unique ...

tion, core inflation and inflation expectations. The literature review throughout this dissertation highlights the role of inflation expectations on actual inflation dynamics and policymaking. Inflation expectations are an important input in intertemporal consumption or investment decisions. The Euler equation model for consumption (or Euler's

Working Paper 32160. DOI 10.3386/w32160. Issue Date February 2024. We study the long-term effects of inflation surges on inflation expectations. German households living in areas with higher local inflation during the hyperinflation of the 1920s expect higher inflation today, after partialling out determinants of historical inflation and ...

Essay on Inflation! Essay on the Meaning of Inflation: Inflation and unemployment are the two most talked-about words in the contemporary society. These two are the big problems that plague all the economies. Almost everyone is sure that he knows what inflation exactly is, but it remains a source of great deal of confusion because it is difficult to define it unambiguously. Inflation is often ...

Historical Data. Excel: This spreadsheet contains inflation expectations model's output from 1982 to the present. Output includes expected inflation for horizons from 1 year to 30 years, the real risk premium, the inflation risk premium, and the real interest rate. Revisions: See this PDF for a list and description of revisions and corrections.

The improved anchoring comes in two dimensions. First, the overall volatility of expectations has declined - for example, survey measures of long-term inflation are essentially flat since 1995. Second, shocks to variables such as inflation have a smaller impact on inflation today than 25 years ago.

Cite. This thesis investigates the dynamics of inflation expectations with a particular focus on survey data. It aims to further the understanding of what drives inflation expectations and what are the implications of changes in inflation expectations for economic choices. The first chapter examines to what extent monetary policy moves ...

Inflation. Median inflation expectations at the one-year horizon declined to 3.2% in May from 3.3% in April, were unchanged at the three-year horizon at 2.8%, and increased at the five-year horizon to 3.0% from 2.8%. The survey's measure of disagreement across respondents (the difference between the 75th and 25th percentile of inflation ...

e papers carry the names of the authors and should be cited accordingly. e ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those ... The book documents that inflation expectations are more weakly anchored in EMDEs than in advanced economies and, in EMDEs that do not operate inflation targeting ...

A decomposition of the model shows that the consumer's attention allocation trade-off between these two sub-index components is an important factor in the model's ability to explain the variation in inflation expectations expressed by Swedish households. Essay II: What is the effect of monetary policy announcements on inflation expectations ...

Inflation in the Fed's preferred price index surpassed 7 percent in the 12 months ending in June 2022, a result of a mix of commodity price shocks and sectoral bottlenecks brought on by the ...

Browse the Working Papers about inflation written by our economists. ... The Survey of Firms' Inflation Expectations (SoFIE) is a large quarterly representative panel of firms in the manufacturing and services sectors that was created to measure inflation expectations of chief executive officers (CEOs) in the United States. ...

The Conference Board said on Tuesday that its consumer confidence index increased to 100.3 this month from a downwardly revised 97.8 in June. Economists polled by Reuters had forecast the index ...